Roland Kelts's Blog, page 7

November 15, 2022

"The Lingering Tragedy of Japan's Lost Generation" for The New York Times

The Lingering Tragedy of Japan’s Lost Generation

Mark Wang

Mark WangI met Hiroshi S. a few years ago at a support group in Tokyo for socially isolated Japanese.

A chain-smoking 43-year-old in a puffy down vest, he was one of an estimated one million or more Japanese known as hikikomori, which roughly translates as “extreme recluses.” Typically male, between the ages of 30 and 50, jobless or underemployed, they have largely withdrawn from society after Japan’s extended economic malaise since the 1990s prevented them from getting their working lives in order.Hiroshi, who asked that his full name not be used, crashed out of Japan’s corporate job market roughly 20 years earlier and was living off his aging, unsympathetic parents in their home, where he racked up credit card debt on pop culture merchandise. He even contemplated suicide.

“Japan has changed,” he told me, referring to the shrinking opportunities and hope available to his generation. He never once looked me in the eye.

That was in 2017. Since then, Japan has done little to address the despair of the hikikomori or the much larger lost generation of economically marginalized individuals to which they belong.

Masahide Yuuki

Masahide YuukiIt’s a national mental health and employment crisis that has persisted for years, and there are concerns that it is being worsened by the Covid pandemic. But political leaders and a society that values stoic conformity and steady employment seem fundamentally unable to summon the willpower and tools to confront the crisis.

Japan’s lost generation is estimated to number as many as 17 million, men and women who came of age during the decades of economic stagnation that the country is still struggling to shake off.

Their predicament is back in the public eye after the assassination of the former Japanese prime minister Shinzo Abe in July. He was gunned down by Tetsuya Yamagami, 41 at the time, who sent a letter to a blogger one day before the killing, blaming the Unification Church — an organization with longstanding ties to Mr. Abe’s Liberal Democratic Party — for “destroying my family and driving it into bankruptcy.” Mr. Yamagami’s mother, a member, had made large donations to the church.

No details have yet emerged to suggest that Mr. Yamagami’s being from the lost generation was a factor in the killing. But some Japanese media outlets and academics have pointed out that details of his life that have emerged — his trouble fitting into society and the workforce — mark him as a member of that struggling group, and that the deeper roots of his anger are being ignored by the conservative establishment’s focus on the hot-button political issue of Liberal Democratic ties to the Unification Church, the conservative religious group founded in South Korea by the Rev. Sun Myung Moon in 1954.

Those roots lie in the fading promise of Japan’s postwar socioeconomic model, which centered on the salaryman, whose lifetime corporate employment supported his nuclear family. This model has frayed badly since the bursting of Japan’s economic bubble — a period of easy credit and hyperinflated stock and real estate values — in the early 1990s, which tipped Japan into an ongoing economic sluggishness.

The response by the Liberal Democratic Party, which has dominated postwar Japan, is blamed for worsening things with policies focused on sustaining corporate profits. In the process, the full-time work force was trimmed, and short-term jobs with reduced or no benefits have increased. A period of job market paralysis known as the employment ice age ensued. Middle-class incomes fell, marriage and birth rates declined, and the percentage of single-person households rose.

The isolated Japanese often have nowhere to turn. Despite recent improvements, mental health services in Japan remain inadequate and often expensive. Psychological counseling remains unpopular in a country where cultural principles like gaman — Japan’s version of Britain’s stiff upper lip — stigmatize seeking help as shameful. Domestic media typically frame those of the lost generation not as victims but as self-absorbed ingrates.

Masahide Yuuki

Masahide YuukiResentment over this labeling was clear in the support group I attended, which met in a basement lounge in Tokyo’s red-light district of Kabukicho. (I attended several meetings as a journalist with the support of all involved.) None of the roughly 40 participants, dressed casually but neatly, looked out of the ordinary. They were calm and articulate and arrestingly candid about their insecurities, joblessness, loneliness and, especially, their anger — directed at an older generation whose response to their problems was often expressed as ganbaru. (“Work harder!”) Some lived with their parents but rarely spoke to them.

In 2019 an unemployed 51-year-old recluse went on a stabbing rampage, killing two people and injuring 17, most of them schoolgirls, fueling public concerns about violence by the economically and socially marginalized. A week later, the government drew up plans to create up to 300,000 jobs for those stranded by the employment ice age. But little came of the plan, and Mr. Abe’s trickle-down economic policies are blamed for exacerbating the pressure on job seekers.

To many in Japan, Mr. Yamagami is a prime example of the lost generation’s marginalization and distance from unsympathetic parents and, for some, a focus of sympathy.

Yet no policy relief appears on the horizon. Mr. Abe’s successor, Prime Minister Fumio Kishida, took office last year with plans for a “new capitalism” that will include wealth redistribution, wage increases and benefits for part-time or short-term workers.

But Mr. Kishida’s administration is on the defensive over Liberal Democratic connections to the Unification Church, which has been accused of aggressively soliciting donations from members. Mr. Kishida’s unpopular decision to hold a taxpayer-funded state funeral to honor Mr. Abe, rising inflation and a falling yen have sent his cabinet’s approval numbers tumbling, weakening his ability to push anything through. He no longer mentions new capitalism, instead echoing Mr. Abe in prioritizing economic growth.

Missing from all of this is any real public discussion of ways to get the lost generation on track. Solutions will require genuine change — not by these millions of long-suffering people but by the hidebound society in which they live.

• Roland Kelts (@rolandkelts) is a Japanese American writer and visiting professor at Waseda University in Tokyo. He is the author of and “The Art of Blade Runner: Black Lotus.”

• The New York Times• The Market Herald, AU• The Straits Times, SG

"The Lingering Tragedy of Japan's Lost Generation" essay for The New York Times

The Lingering Tragedy of Japan’s Lost Generation

Mark Wang

Mark WangI met Hiroshi S. a few years ago at a support group in Tokyo for socially isolated Japanese.

A chain-smoking 43-year-old in a puffy down vest, he was one of an estimated one million or more Japanese known as hikikomori, which roughly translates as “extreme recluses.” Typically male, between the ages of 30 and 50, jobless or underemployed, they have largely withdrawn from society after Japan’s extended economic malaise since the 1990s prevented them from getting their working lives in order.Hiroshi, who asked that his full name not be used, crashed out of Japan’s corporate job market roughly 20 years earlier and was living off his aging, unsympathetic parents in their home, where he racked up credit card debt on pop culture merchandise. He even contemplated suicide.

“Japan has changed,” he told me, referring to the shrinking opportunities and hope available to his generation. He never once looked me in the eye.

That was in 2017. Since then, Japan has done little to address the despair of the hikikomori or the much larger lost generation of economically marginalized individuals to which they belong.

Masahide Yuuki

Masahide YuukiIt’s a national mental health and employment crisis that has persisted for years, and there are concerns that it is being worsened by the Covid pandemic. But political leaders and a society that values stoic conformity and steady employment seem fundamentally unable to summon the willpower and tools to confront the crisis.

Japan’s lost generation is estimated to number as many as 17 million, men and women who came of age during the decades of economic stagnation that the country is still struggling to shake off.

Their predicament is back in the public eye after the assassination of the former Japanese prime minister Shinzo Abe in July. He was gunned down by Tetsuya Yamagami, 41 at the time, who sent a letter to a blogger one day before the killing, blaming the Unification Church — an organization with longstanding ties to Mr. Abe’s Liberal Democratic Party — for “destroying my family and driving it into bankruptcy.” Mr. Yamagami’s mother, a member, had made large donations to the church.

No details have yet emerged to suggest that Mr. Yamagami’s being from the lost generation was a factor in the killing. But some Japanese media outlets and academics have pointed out that details of his life that have emerged — his trouble fitting into society and the workforce — mark him as a member of that struggling group, and that the deeper roots of his anger are being ignored by the conservative establishment’s focus on the hot-button political issue of Liberal Democratic ties to the Unification Church, the conservative religious group founded in South Korea by the Rev. Sun Myung Moon in 1954.

Those roots lie in the fading promise of Japan’s postwar socioeconomic model, which centered on the salaryman, whose lifetime corporate employment supported his nuclear family. This model has frayed badly since the bursting of Japan’s economic bubble — a period of easy credit and hyperinflated stock and real estate values — in the early 1990s, which tipped Japan into an ongoing economic sluggishness.

The response by the Liberal Democratic Party, which has dominated postwar Japan, is blamed for worsening things with policies focused on sustaining corporate profits. In the process, the full-time work force was trimmed, and short-term jobs with reduced or no benefits have increased. A period of job market paralysis known as the employment ice age ensued. Middle-class incomes fell, marriage and birth rates declined, and the percentage of single-person households rose.

The isolated Japanese often have nowhere to turn. Despite recent improvements, mental health services in Japan remain inadequate and often expensive. Psychological counseling remains unpopular in a country where cultural principles like gaman — Japan’s version of Britain’s stiff upper lip — stigmatize seeking help as shameful. Domestic media typically frame those of the lost generation not as victims but as self-absorbed ingrates.

Masahide Yuuki

Masahide YuukiResentment over this labeling was clear in the support group I attended, which met in a basement lounge in Tokyo’s red-light district of Kabukicho. (I attended several meetings as a journalist with the support of all involved.) None of the roughly 40 participants, dressed casually but neatly, looked out of the ordinary. They were calm and articulate and arrestingly candid about their insecurities, joblessness, loneliness and, especially, their anger — directed at an older generation whose response to their problems was often expressed as ganbaru. (“Work harder!”) Some lived with their parents but rarely spoke to them.

In 2019 an unemployed 51-year-old recluse went on a stabbing rampage, killing two people and injuring 17, most of them schoolgirls, fueling public concerns about violence by the economically and socially marginalized. A week later, the government drew up plans to create up to 300,000 jobs for those stranded by the employment ice age. But little came of the plan, and Mr. Abe’s trickle-down economic policies are blamed for exacerbating the pressure on job seekers.

To many in Japan, Mr. Yamagami is a prime example of the lost generation’s marginalization and distance from unsympathetic parents and, for some, a focus of sympathy.

Yet no policy relief appears on the horizon. Mr. Abe’s successor, Prime Minister Fumio Kishida, took office last year with plans for a “new capitalism” that will include wealth redistribution, wage increases and benefits for part-time or short-term workers.

But Mr. Kishida’s administration is on the defensive over Liberal Democratic connections to the Unification Church, which has been accused of aggressively soliciting donations from members. Mr. Kishida’s unpopular decision to hold a taxpayer-funded state funeral to honor Mr. Abe, rising inflation and a falling yen have sent his cabinet’s approval numbers tumbling, weakening his ability to push anything through. He no longer mentions new capitalism, instead echoing Mr. Abe in prioritizing economic growth.

Missing from all of this is any real public discussion of ways to get the lost generation on track. Solutions will require genuine change — not by these millions of long-suffering people but by the hidebound society in which they live.

• Roland Kelts (@rolandkelts) is a Japanese American writer and visiting professor at Waseda University in Tokyo. He is the author of and “The Art of Blade Runner: Black Lotus.”

• The New York Times• The Market Herald, AU• The Straits Times, SG

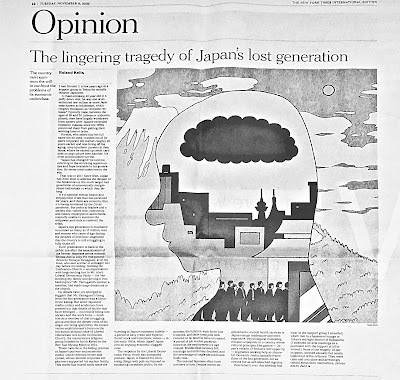

"The Lingering Tragedy of Japan's Lost Generation" opinion essay for The New York Times

The Lingering Tragedy of Japan’s Lost Generation

Masahide Yuuki

Masahide YuukiI met Hiroshi S. a few years ago at a support group in Tokyo for socially isolated Japanese.

A chain-smoking 43-year-old in a puffy down vest, he was one of an estimated one million or more Japanese known as hikikomori, which roughly translates as “extreme recluses.” Typically male, between the ages of 30 and 50, jobless or underemployed, they have largely withdrawn from society after Japan’s extended economic malaise since the 1990s prevented them from getting their working lives in order.Hiroshi, who asked that his full name not be used, crashed out of Japan’s corporate job market roughly 20 years earlier and was living off his aging, unsympathetic parents in their home, where he racked up credit card debt on pop culture merchandise. He even contemplated suicide.

“Japan has changed,” he told me, referring to the shrinking opportunities and hope available to his generation. He never once looked me in the eye.

That was in 2017. Since then, Japan has done little to address the despair of the hikikomori or the much larger lost generation of economically marginalized individuals to which they belong.

Masahide Yuuki

Masahide YuukiIt’s a national mental health and employment crisis that has persisted for years, and there are concerns that it is being worsened by the Covid pandemic. But political leaders and a society that values stoic conformity and steady employment seem fundamentally unable to summon the willpower and tools to confront the crisis.

Japan’s lost generation is estimated to number as many as 17 million, men and women who came of age during the decades of economic stagnation that the country is still struggling to shake off.

Their predicament is back in the public eye after the assassination of the former Japanese prime minister Shinzo Abe in July. He was gunned down by Tetsuya Yamagami, 41 at the time, who sent a letter to a blogger one day before the killing, blaming the Unification Church — an organization with longstanding ties to Mr. Abe’s Liberal Democratic Party — for “destroying my family and driving it into bankruptcy.” Mr. Yamagami’s mother, a member, had made large donations to the church.

No details have yet emerged to suggest that Mr. Yamagami’s being from the lost generation was a factor in the killing. But some Japanese media outlets and academics have pointed out that details of his life that have emerged — his trouble fitting into society and the workforce — mark him as a member of that struggling group, and that the deeper roots of his anger are being ignored by the conservative establishment’s focus on the hot-button political issue of Liberal Democratic ties to the Unification Church, the conservative religious group founded in South Korea by the Rev. Sun Myung Moon in 1954.

Those roots lie in the fading promise of Japan’s postwar socioeconomic model, which centered on the salaryman, whose lifetime corporate employment supported his nuclear family. This model has frayed badly since the bursting of Japan’s economic bubble — a period of easy credit and hyperinflated stock and real estate values — in the early 1990s, which tipped Japan into an ongoing economic sluggishness.

The response by the Liberal Democratic Party, which has dominated postwar Japan, is blamed for worsening things with policies focused on sustaining corporate profits. In the process, the full-time work force was trimmed, and short-term jobs with reduced or no benefits have increased. A period of job market paralysis known as the employment ice age ensued. Middle-class incomes fell, marriage and birth rates declined, and the percentage of single-person households rose.

The isolated Japanese often have nowhere to turn. Despite recent improvements, mental health services in Japan remain inadequate and often expensive. Psychological counseling remains unpopular in a country where cultural principles like gaman — Japan’s version of Britain’s stiff upper lip — stigmatize seeking help as shameful. Domestic media typically frame those of the lost generation not as victims but as self-absorbed ingrates.

Masahide Yuuki

Masahide YuukiResentment over this labeling was clear in the support group I attended, which met in a basement lounge in Tokyo’s red-light district of Kabukicho. (I attended several meetings as a journalist with the support of all involved.) None of the roughly 40 participants, dressed casually but neatly, looked out of the ordinary. They were calm and articulate and arrestingly candid about their insecurities, joblessness, loneliness and, especially, their anger — directed at an older generation whose response to their problems was often expressed as ganbaru. (“Work harder!”) Some lived with their parents but rarely spoke to them...

• More @nytimes• The Market Herald, AU• The Straits Times, SG

• Roland Kelts (@rolandkelts) is a Japanese American writer and visiting professor at Waseda University in Tokyo. He is the author of and “The Art of Blade Runner: Black Lotus.”

November 10, 2022

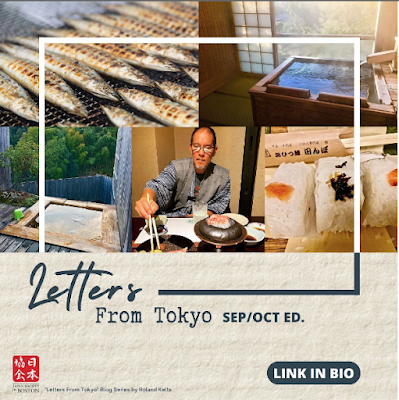

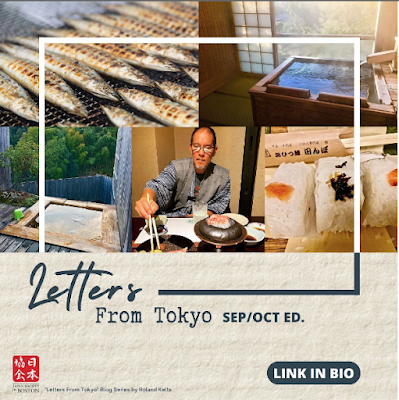

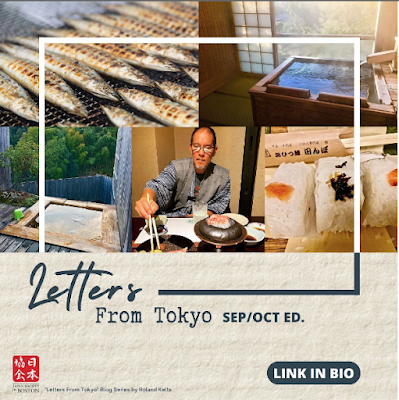

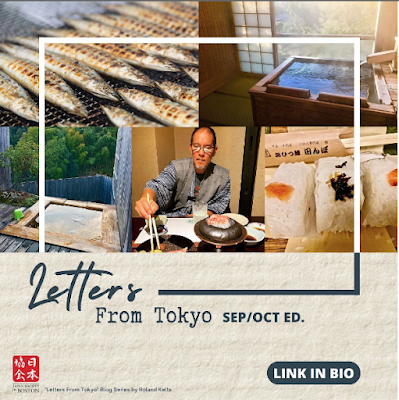

Letters from Tokyo, September-October 2022: "Autumn is for Eating" for The Japan Society of Boston

Letters from Tokyo, September-October 2022: Autumn is for Eating

Autumn in New York was romanticized long ago by the eponymous 1934 jazz standard, and the phrase remains classic. Everyone knows the season is romantic in climate and hue, especially in Central Park and along the Hudson, where you can actually see the leaves change color against the backdrop of the buildings.

But autumn in Tokyo can be equally inviting, if not more so. For one thing, its drop in dew points can be a lifesaver for the heatstroke prone. Plus, it lasts longer.

I first learned about dew points in high school from my friend Jim. The higher the dew point, the stickier you feel. Your sweat has nowhere to go so it stays on your skin and your pores can't breathe. Jim was the goalie of our soccer team but dreamed of becoming a meteorologist. Today he works for the US National Weather Service in the mountains of upstate New York. And I live in Tokyo, where I keep a close eye on dew points every time autumn rolls around.

September, per usual, felt like an extension of summer, its heat easing in the evenings but still suited to short sleeves. Before I had to fly back to New England again near the end of the month during the chaos of Abe’s State Funeral, Tokyo was still closed to most tourists. Excursion bookings were quick and easy, restaurant reservations a breeze. As Covid infection numbers dropped weekly, a lovely window opened where most of us began feeling calmer and safer even as we continued wearing masks, washing hands and sanitizing.

It was nice to go out in town and get out of town. My walks around Meiji Shrine and Yoyogi Park were uncluttered and quiet. Kids and young adults had returned to the running track, soccer fields, foosball and basketball courts at the south end of the park, but their numbers were still thinned, their grunts drowned out by crow caws. The entire Events Square near NHK with its concrete Hatch Shell-like concert stage remained empty, its international fairs, concerts and sponsored markets postponed, which was fine with me. I’ve been to too many to notice much that’s new each year, and with a few seasonal exceptions (like grilled ayu and sanma), the greasy fare from yatai food stalls is the kind of junk food I can now easily pass up.

But that lovely window was closing fast. The government’s staggered announcements about lifting restrictions were confusing (first yes, then no, not that one, then: okay, maybe all of them) but its direction was clear: Japan was adopting US and European style post-Covid openness, not China’s zero-Covid crackdowns.

My first priority was to support nearby eateries, especially those locally owned and operated by people you see onsite nearly every time you visit. This is a lot easier to do in Tokyo than in large American cities. Tokyo has more restaurants per square kilometer than any other city in the world, and seems to have more restaurants period. While some of Tokyo’s major rail hubs have fallen victim to mallification, with floor upon floor of Starbucks, Uniqlo and Muji outlets, the backstreets and warrens of its residential neighborhoods still abound with small, sometimes tiny, independent restaurants and bars.

Returning to Tanbo, a humble shokudo and teishoku joint just around the corner, felt like a homecoming. Having been away for the better part of a year, I didn't quite realize how deeply I’d missed the restaurant’s specialty: fresh rice from a seasonally shifting variety of northern regions identified on the menu board, with fish or donburi toppings or packed into thick onigiri rice balls, served alongside smoky miso soup and diced pickles.

After consuming so many sometimes-delicious sweet, savory, often sauce-covered meals at restaurants in Florida, California, Massachusetts, Connecticut and New York, the taste of fresh nori and soft white rice hit me with Proustian force. Just like mama made—except my Japanese mother, who has spent most of her life in the US as an American citizen, never once prepared for me homemade onigiri.

Next up was an Italian (er, Japanese-Italian) favorite just down the block, La Buona Vita, which is slightly larger than an L-shaped hallway with a counter. Sea urchin and salmon eggs atop black squid ink pasta would not have appealed to me back when I was a semi-regular at Italian restaurants in Manhattan and Brooklyn, but now it’s “to die for,” as they say, though that's something I’ve never actually said. Founder and chef Motokazu Ishii is almost always on the premises, gliding around the kitchen and peering over the counter to survey the scene.

Of course, living in Tokyo for so many years has also made me a Goldilocks about serving sizes. Much is made in the US of the health value of, say, leveling off that mountain of fries or making do with one pizza versus adding a second at half-price, but presentation also matters. I find food a lot more appetizing when it’s not served in a massive heap or spilling out all over the place.

That said, a return to Shinjuku’s famous Ramen Jiro or a breakfast at any onsen-yado is a reminder that Japan does massive food heaps just fine. I skip Jiro these days to preserve my arteries, but a return to a favorite little onsen in Izu was an irresistible pre-tourist rush.

Rakuzen Yasuda is tucked into a hillside in Izunokuni and its rooms are unearthly quiet. Every floor is tatami-matted; you pad and glide through its hallways like a ghost. The private in-room baths and the outdoor rooftop rotenburo face the hill’s dense greenery of cypress and cedars limning the sky. It’s even possible for someone like me to gaze without thinking for a while.

Each portion is modest and delicious, but the cumulative morning and evening full-course meals are huge. Your body displaces water as you slide into the tub and you begin to envision your next breakfast back home in Tokyo: a bowl of Bifix yogurt and a slice of banana or pear.

I re-landed in Tokyo in early October, just as tourism restrictions were lifted and our window of native calm closed. It seemed apt to sneak in one more stealth reservation, this time, ironically, at the recently opened Tokyo branch of Peter Luger, one of New York’s oldest and most famous steakhouses. The aged steak was flown in from the US and aged some more in the Ebisu facility, which, our waiter politely explained, we were not allowed to see.

Our T-Bone from New York was warm, juicy—and pricey. That much travel and time extract a heavy cost, as I know full well.

Now we're in mid-season for sanma, that slim but meaty blue fish whose rich juices are a lot better for you than red meat, wherever it’s sourced. Unlike New York, Tokyo boasts an autumn that stretches far into November and even early December. The dew points have dropped, the tourists are back, and the foliage is making its way south into the city’s parks. Come on in! See you in Meguro.

Letters from Tokyo, September-October, 2022: "Autumn is for Eating" for The Japan Society of Boston

Letters from Tokyo, September-October, 2022: Autumn is for Eating

Autumn in New York was romanticized long ago by the eponymous 1934 jazz standard, and the phrase remains classic. Everyone knows the season is romantic in climate and hue, especially in Central Park and along the Hudson, where you can actually see the leaves change color against the backdrop of the buildings.

But autumn in Tokyo can be equally inviting, if not more so. For one thing, its drop in dew points can be a lifesaver for the heatstroke prone. Plus, it lasts longer.

I first learned about dew points in high school from my friend Jim. The higher the dew point, the stickier you feel. Your sweat has nowhere to go so it stays on your skin and your pores can't breathe. Jim was the goalie of our soccer team but dreamed of becoming a meteorologist. Today he works for the US National Weather Service in the mountains of upstate New York. And I live in Tokyo, where I keep a close eye on dew points every time autumn rolls around...

September, per usual, felt like an extension of summer, its heat easing in the evenings but still suited to short sleeves. Before I had to fly back to New England again near the end of the month during the chaos of Abe’s State Funeral, Tokyo was still closed to most tourists. Excursion bookings were quick and easy, restaurant reservations a breeze. As Covid infection numbers dropped weekly, a lovely window opened where most of us began feeling calmer and safer even as we continued wearing masks, washing hands and sanitizing.

It was nice to go out in town and get out of town. My walks around Meiji Shrine and Yoyogi Park were uncluttered and quiet. Kids and young adults had returned to the running track, soccer fields, foosball and basketball courts at the south end of the park, but their numbers were still thinned, their grunts drowned out by crow caws. The entire Events Square near NHK with its concrete Hatch Shell-like concert stage remained empty, its international fairs, concerts and sponsored markets postponed, which was fine with me. I’ve been to too many to notice much that’s new each year, and with a few seasonal exceptions (like grilled ayu and sanma), the greasy fare from yatai food stalls is the kind of junk food I can now easily pass up.

But that lovely window was closing fast. The government’s staggered announcements about lifting restrictions were confusing (first yes, then no, not that one, then: okay, maybe all of them) but its direction was clear: Japan was adopting US and European style post-Covid openness, not China’s zero-Covid crackdowns.

My first priority was to support nearby eateries, especially those locally owned and operated by people you see onsite nearly every time you visit. This is a lot easier to do in Tokyo than in large American cities. Tokyo has more restaurants per square kilometer than any other city in the world, and seems to have more restaurants period. While some of Tokyo’s major rail hubs have fallen victim to mallification, with floor upon floor of Starbucks, Uniqlo and Muji outlets, the backstreets and warrens of its residential neighborhoods still abound with small, sometimes tiny, independent restaurants and bars.

Returning to Tanbo, a humble shokudo and teishoku joint just around the corner, felt like a homecoming. Having been away for the better part of a year, I didn't quite realize how deeply I’d missed the restaurant’s specialty: fresh rice from a seasonally shifting variety of northern regions identified on the menu board, with fish or donburi toppings or packed into thick onigiri rice balls, served alongside smoky miso soup and diced pickles.

After consuming so many sometimes-delicious sweet, savory, often sauce-covered meals at restaurants in Florida, California, Massachusetts, Connecticut and New York, the taste of fresh nori and soft white rice hit me with Proustian force. Just like mama made—except my Japanese mother, who has spent most of her life in the US as an American citizen, never once prepared for me homemade onigiri.

Next up was an Italian (er, Japanese-Italian) favorite just down the block, La Buona Vita, which is slightly larger than an L-shaped hallway with a counter. Sea urchin and salmon eggs atop black squid ink pasta would not have appealed to me back when I was a semi-regular at Italian restaurants in Manhattan and Brooklyn, but now it’s “to die for,” as they say, though that's something I’ve never actually said. Founder and chef Motokazu Ishii is almost always on the premises, gliding around the kitchen and peering over the counter to survey the scene.

Of course, living in Tokyo for so many years has also made me a Goldilocks about serving sizes. Much is made in the US of the health value of, say, leveling off that mountain of fries or making do with one pizza versus adding a second at half-price, but presentation also matters. I find food a lot more appetizing when it’s not served in a massive heap or spilling out all over the place.

That said, a return to Shinjuku’s famous Ramen Jiro or a breakfast at any onsen-yado is a reminder that Japan does massive food heaps just fine. I skip Jiro these days to preserve my arteries, but a return to a favorite little onsen in Izu was an irresistible pre-tourist rush.

Rakuzen Yasuda is tucked into a hillside in Izunokuni and its rooms are unearthly quiet. Every floor is tatami-matted; you pad and glide through its hallways like a ghost. The private in-room baths and the outdoor rooftop rotenburo face the hill’s dense greenery of cypress and cedars limning the sky. It’s even possible for someone like me to gaze without thinking for a while.

Each portion is modest and delicious, but the cumulative morning and evening full-course meals are huge. Your body displaces water as you slide into the tub and you begin to envision your next breakfast back home in Tokyo: a bowl of Bifix yogurt and a slice of banana or pear.

I re-landed in Tokyo in early October, just as tourism restrictions were lifted and our window of native calm closed. It seemed apt to sneak in one more stealth reservation, this time, ironically, at the recently opened Tokyo branch of Peter Luger, one of New York’s oldest and most famous steakhouses. The aged steak was flown in from the US and aged some more in the Ebisu facility, which, our waiter politely explained, we were not allowed to see.

Our T-Bone from New York was warm, juicy—and pricey. That much travel and time extract a heavy cost, as I know full well.

Now we're in mid-season for sanma, that slim but meaty blue fish whose rich juices are a lot better for you than red meat, wherever it’s sourced. Unlike New York, Tokyo boasts an autumn that stretches far into November and even early December. The dew points have dropped, the tourists are back, and the foliage is making its way south into the city’s parks. Come on in! See you in Meguro.

Letters from Tokyo, September-October, 2022: Autumn is for Eating! @ The Japan Society of Boston

Letters from Tokyo, September-October, 2022: Autumn is for Eating

Autumn in New York was romanticized long ago by the eponymous 1934 jazz standard, and the phrase remains classic. Everyone knows the season is romantic in climate and hue, especially in Central Park and along the Hudson, where you can actually see the leaves change color against the backdrop of the buildings.

But autumn in Tokyo can be equally inviting, if not more so. For one thing, its drop in dew points can be a lifesaver for the heatstroke prone. Plus, it lasts longer.

I first learned about dew points in high school from my friend Jim. The higher the dew point, the stickier you feel. Your sweat has nowhere to go so it stays on your skin and your pores can't breathe. Jim was the goalie of our soccer team but dreamed of becoming a meteorologist. Today he works for the US National Weather Service in the mountains of upstate New York. And I live in Tokyo, where I keep a close eye on dew points every time autumn rolls around...

September, per usual, felt like an extension of summer, its heat easing in the evenings but still suited to short sleeves. Before I had to fly back to New England again near the end of the month during the chaos of Abe’s State Funeral, Tokyo was still closed to most tourists. Excursion bookings were quick and easy, restaurant reservations a breeze. As Covid infection numbers dropped weekly, a lovely window opened where most of us began feeling calmer and safer even as we continued wearing masks, washing hands and sanitizing.

It was nice to go out in town and get out of town. My walks around Meiji Shrine and Yoyogi Park were uncluttered and quiet. Kids and young adults had returned to the running track, soccer fields, foosball and basketball courts at the south end of the park, but their numbers were still thinned, their grunts drowned out by crow caws. The entire Events Square near NHK with its concrete Hatch Shell-like concert stage remained empty, its international fairs, concerts and sponsored markets postponed, which was fine with me. I’ve been to too many to notice much that’s new each year, and with a few seasonal exceptions (like grilled ayu and sanma), the greasy fare from yatai food stalls is the kind of junk food I can now easily pass up.

But that lovely window was closing fast. The government’s staggered announcements about lifting restrictions were confusing (first yes, then no, not that one, then: okay, maybe all of them) but its direction was clear: Japan was adopting US and European style post-Covid openness, not China’s zero-Covid crackdowns.

My first priority was to support nearby eateries, especially those locally owned and operated by people you see onsite nearly every time you visit. This is a lot easier to do in Tokyo than in large American cities. Tokyo has more restaurants per square kilometer than any other city in the world, and seems to have more restaurants period. While some of Tokyo’s major rail hubs have fallen victim to mallification, with floor upon floor of Starbucks, Uniqlo and Muji outlets, the backstreets and warrens of its residential neighborhoods still abound with small, sometimes tiny, independent restaurants and bars.

Returning to Tanbo, a humble shokudo and teishoku joint just around the corner, felt like a homecoming. Having been away for the better part of a year, I didn't quite realize how deeply I’d missed the restaurant’s specialty: fresh rice from a seasonally shifting variety of northern regions identified on the menu board, with fish or donburi toppings or packed into thick onigiri rice balls, served alongside smoky miso soup and diced pickles.

After consuming so many sometimes-delicious sweet, savory, often sauce-covered meals at restaurants in Florida, California, Massachusetts, Connecticut and New York, the taste of fresh nori and soft white rice hit me with Proustian force. Just like mama made—except my Japanese mother, who has spent most of her life in the US as an American citizen, never once prepared for me homemade onigiri.

Next up was an Italian (er, Japanese-Italian) favorite just down the block, La Buona Vita, which is slightly larger than an L-shaped hallway with a counter. Sea urchin and salmon eggs atop black squid ink pasta would not have appealed to me back when I was a semi-regular at Italian restaurants in Manhattan and Brooklyn, but now it’s “to die for,” as they say, though that's something I’ve never actually said. Founder and chef Motokazu Ishii is almost always on the premises, gliding around the kitchen and peering over the counter to survey the scene.

Of course, living in Tokyo for so many years has also made me a Goldilocks about serving sizes. Much is made in the US of the health value of, say, leveling off that mountain of fries or making do with one pizza versus adding a second at half-price, but presentation also matters. I find food a lot more appetizing when it’s not served in a massive heap or spilling out all over the place.

That said, a return to Shinjuku’s famous Ramen Jiro or a breakfast at any onsen-yado is a reminder that Japan does massive food heaps just fine. I skip Jiro these days to preserve my arteries, but a return to a favorite little onsen in Izu was an irresistible pre-tourist rush.

Rakuzen Yasuda is tucked into a hillside in Izunokuni and its rooms are unearthly quiet. Every floor is tatami-matted; you pad and glide through its hallways like a ghost. The private in-room baths and the outdoor rooftop rotenburo face the hill’s dense greenery of cypress and cedars limning the sky. It’s even possible for someone like me to gaze without thinking for a while.

Each portion is modest and delicious, but the cumulative morning and evening full-course meals are huge. Your body displaces water as you slide into the tub and you begin to envision your next breakfast back home in Tokyo: a bowl of Bifix yogurt and a slice of banana or pear.

I re-landed in Tokyo in early October, just as tourism restrictions were lifted and our window of native calm closed. It seemed apt to sneak in one more stealth reservation, this time, ironically, at the recently opened Tokyo branch of Peter Luger, one of New York’s oldest and most famous steakhouses. The aged steak was flown in from the US and aged some more in the Ebisu facility, which, our waiter politely explained, we were not allowed to see.

Our T-Bone from New York was warm, juicy—and pricey. That much travel and time extract a heavy cost, as I know full well.

Now we're in mid-season for sanma, that slim but meaty blue fish whose rich juices are a lot better for you than red meat, wherever it’s sourced. Unlike New York, Tokyo boasts an autumn that stretches far into November and even early December. The dew points have dropped, the tourists are back, and the foliage is making its way south into the city’s parks. Come on in! See you in Meguro.

Letters from Tokyo, September-October, 2022: Autumn is for Eating! The Japan Society of Boston

Letters from Tokyo, September-October, 2022: Autumn is for Eating

Autumn in New York was romanticized long ago by the eponymous 1934 jazz standard, and the phrase remains classic. Everyone knows the season is romantic in climate and hue, especially in Central Park and along the Hudson, where you can actually see the leaves change color against the backdrop of the buildings.

But autumn in Tokyo can be equally inviting, if not more so. For one thing, its drop in dew points can be a lifesaver for the heatstroke prone. Plus, it lasts longer.

I first learned about dew points in high school from my friend Jim. The higher the dew point, the stickier you feel. Your sweat has nowhere to go so it stays on your skin and your pores can't breathe. Jim was the goalie of our soccer team but dreamed of becoming a meteorologist. Today he works for the US National Weather Service in the mountains of upstate New York. And I live in Tokyo, where I keep a close eye on dew points every time autumn rolls around...

October 31, 2022

New column on "Oni: Thunder God's Tale" for The Japan Times

[Finally resuming my monthly "Culture Clash" column for The Japan Times.]

Indie studio Tonko House's coming-of-age story portrays a multiethnic Japan

Fairy tales usually move from humdrum reality to fantasy and back again, with the protagonist and the rest of the audience transformed along the way. Think Alice and the rabbit hole, Chihiro and the tunnel in “Spirited Away.” But the CG-animated limited series “Oni: Thunder God’s Tale” opens in a Japanese dream world before crossing the threshold into an urban Japan that is darker and far more dangerous.

“Oni” is the latest work from indie animation studio Tonko House, with a script by veteran anime writer Mari Okada (“Macquia: When the Promised Flower Blooms”). The series uses digital techniques to mimic the tactile, slightly jerky movements of stop-motion animation, making its visuals feel intimate despite the story’s dizzying array of characters and Hollywood action-adventure scope: a four-episode, 154-minute epic that blends traditional Japanese folklore with a modern take on racial and ethnic conflict.

The Japan Times

The Japan TimesWe land in a forest village whose quirky locals are plucked from Japan’s mythological past: gods, demons and shape-shifting yōkai spirits, including a talking one-eyed umbrella (kasa-obake), tumbling daruma dolls and a frog-like child kappa, whose head, true to historical form, bears a shallow pool of water. Each time the kappa politely bows, usually mid-sentence, water spills out and he loses consciousness until someone refills it so he can finish.

One of the series’ many pleasures is that it makes no attempt to explain away any of these eccentricities. Instead, “Oni” presents its oddball animistic Japanese spirits as your average gaggle of American schoolchildren, taught by a winged, long-nosed tengu god, warmly voiced by Japanese American actor George Takei of “Star Trek” fame.

COURTESY OF NETFLIX © 2022

COURTESY OF NETFLIX © 2022“Anything can be a god in Japan,” says director Daisuke “Dice” Tsutsumi in a call with The Japan Times from his home in Berkeley, California. “But all of Japan’s gods are very human. I thought we should drop our audience right into that.”

The drop feels more like a plunge straight into the lives of main characters Naridon, a rotund father with a bright crimson body and massive halo of curly hair, and his rambunctious dervish of a daughter, Onari, whose sometimes haughty behavior masks a looming identity crisis shared by both.

Naridon is supposed to be a fearsome thunder god, but he behaves like a clumsy househusband, giddily chopping vegetables while soup boils over, wobbling on stumpy legs and occasionally passing wind. Also, he’s wordless, uttering only childlike emotive sounds, while his daughter is a quick-witted chatterbox.

Onari meanwhile struggles to summon her inner powers as a godly spirit to confront the demonic oni (ogres) that threaten to one day destroy the village. But she is blocked, frustrated by her lack of magic and blaming her seemingly weak and speechless, if lovable, dad.

“It was tough to push that through,” Tsutsumi says of Naridon’s incoherence. “A main character with no dialogue? How does that work? But he’s carrying a lot of guilt around, something deep inside, and through the design and animation, you can feel his pain even if he can’t express it. Maybe you can feel it more.”

For the Japanese director based in the United States and his Japanese American artistic partner, Robert Kondo, who together founded Tonko House eight years ago after careers at industry giant Pixar Animation Studios, Naridon isn’t their only inarticulate main character. Their first short film, 2014’s “The Dam Keeper,” tells its 18-minute story about a lifesaving friendship between a fox and a pig with a brief voiceover but not a single line of dialogue.

Both titles focus the audience’s attention on their visuals, with exquisite character design and breathtaking shifts in color and light. Also, both feature stories about outsiders, individuals who are ridiculed and shunned by the societies they so desperately want to help.

But while “The Dam Keeper” takes place in a pastel-colored European village, “Oni” is a visual love letter to Japan, from ancient tree-walled forest clearings to shōtengai (shopping streets) densely lined with eateries. When Onari crosses into the urban human world, believing that it’s the land of the dreaded oni, she meets the story’s other outsider: a half-Japanese, half-Black American boy named Calvin.

At first, Calvin’s appearance as a yōkai-obsessed preteen seems incidental, a bit of comic relief. He is the classic nerdy resident Japanophile, mocked by two Japanese schoolmates for being a “gaijin (foreigner) who knows more about Japan than we do!” But he soon emerges as the key to Onari’s self-reckoning, and the two characters form a bond connecting their respective realms of reality and fantasy.

Daisuke "Dice" Tsutsumi and Robert Kondo

Daisuke "Dice" Tsutsumi and Robert KondoTsutsumi says that Calvin was based on an autobiographical source, a biracial best friend from his childhood in Japan. But Calvin’s presence in the series is more than just another woke nod to diversity. Alongside Black actors Craig Robinson (“The Office”), who voices Naridon, and Omar Benson Miller as Naridon’s verbose brother Putaro, the wind god, Seth Hall as Calvin rounds out the series’ portrait of a multiracial, multiethnic Japan that residents will recognize even though it is rarely depicted in media or tourist brochures.

One of the series’ many knowing transcultural scenes is when Calvin comforts a despondent Onari, who usually holds her nose when eating her father’s smelly fermented soybean breakfasts, by sharing with her his exotic and gooey American snack: a peanut butter and jelly sandwich.

When I first visited Tsutsumi and Kondo in 2014, they had just moved into Tonko House’s Berkeley studio and were still arranging furniture around its cramped 200-square-foot floor space, a far cry from Pixar’s vast gated campus just a few miles away.

Both were starting families and painfully aware of the risk they took leaving the animation giant to go it alone. (Though it went on to receive an Oscar nomination for best animated short film in 2015, “The Dam Keeper” had been released to acclaim but was only shown on the festival circuit, which is no way to finance an indie startup.)

They believed that they could combine their experiences in the U.S. with their shared Japanese heritage. Through their love of both countries’ animation cultures, they said, they would try to create “hybrid” works combining the best of each — a tall order for any creative team, big or small. But by deftly blending bravura Hollywood storytelling with Japan’s spiritual touchstones, “Oni” marks a huge leap toward that lofty goal.

October 30, 2022

Latest IDEAS column on digital minister Kono Taro's promise to ditch floppy discs and FAX machines for Rest of World

[Running a little late with the updates owing to travel and, well, life.]

Japan struggles to give up floppy disks and fax machines for the digital age

KYODO

KYODOWhen Kono Taro was tapped in August to lead the government’s one-year-old Digital Agency, dedicated to digitizing Japan’s bureaucracy, headlines lit up with his opening salvos. No more fax machines! Out with floppy disks! His proclamations, delivered via Twitter, elicited cheers overseas. Inside Japan, they were met with muted bemusement.

Fluent in English and dubbed a “maverick” by the global media, the former foreign affairs and defense minister Kono is Japan’s most visible and Twitter-friendly politician ever, in a country more typically known for faceless bureaucrats. (When Yoshitaka Sakurada, the 72-year-old cybersecurity minister for the Tokyo 2020 Olympic Games shamelessly said that he had never once used a computer, his confession was greeted by shock and embarrassment. Though he was promptly forced to resign, no one remembers his name.)

Kono is Japan’s third digital minister in less than a year, leading a department that’s yet to make its mark. For some, his appointment augurs a long-awaited shift into high gear; for others, his man-in-a-hurry image is linked as much to a talent for performing change as actually getting it done. A year and a half ago, Kono successfully untangled the bureaucratic knots and analog procedural requirements holding up Japan’s vaccine rollout, and his reputation follows him to the Digital Agency.

“Kono is perfect for this moment,” Joi Ito, former director of MIT Media Lab and the cofounder of the Japan-based startup incubation company Digital Garage, told Rest of World. “He’s tough on bureaucrats, and he has a good team with actual software engineers. He also has a good relationship with Economy, Trade and Industry Minister Yasutoshi Nishimura, which will be critical for coordinating plans with big business. And Kono [has] a huge following on Twitter.”

Preferring social media rather to a slew of post-appointment interviews, in August, Kono posted a YouTube video promising a laundry list of 1,900 digital transformations that will make life “safe, convenient and prosperous” for Japan’s rapidly aging and declining population — within seven months, by March of next year. The proposals span everything from filing online disaster certificates during crises like earthquakes and typhoons to digitizing more pedestrian processes like changing addresses and signing up for child care services.

To skeptics, the diffuse mandate and distant deadline give Kono ample wriggle room and enough news cycles for public amnesia to set in. March is the end of Japan’s fiscal and academic year, when the results of a minor government agency will barely register as a blip.

Ministerial jobs at newly minted agencies like Kono’s can be doled out by prime ministers who wish to keep rivals at bay. As Koichi Nakano, a political science professor at Sophia University, said to Rest of World: “These ministerial positions are inherently weak and uncompetitive in Kasumigaseki (the seat of Japan’s cabinet) because they encroach upon the turf of other established ministries with decades-long bureaucratic traditions.” Unlike Covid-19 vaccines, digital reforms can wait.

The Japanese government has had some kind of digital venture on the books since 2001, when its inconclusive “e-Japan” strategy was launched. Two decades later, floppy disks and fax machines are still very much de rigueur in Japan’s ministries, universities, and corporate headquarters — indifferent to the fact that they might be a stereotype of the nation’s outdated infrastructure. It begs the question: Even if Kono can deliver, do these transformations really matter to Japan’s political leaders and their constituents?

Japan has the largest proportion of elderly citizens of any country in the world. At 59, Kono is poised to bridge its yawning generation gap. One of his biggest challenges will be convincing the gerontocracy not only that digital progress is a priority, but also getting its members to step aside.

“Deference to authority and the elderly in Japan allows seniors to stay analog without feeling ashamed,” said Ito. “In the U.S., even among fairly senior people, there is a push to keep up with tech. Here in Japan, calling people on the phone is still quite common, and this is partially a deference to older people who don’t feel comfortable sending a text or an email.”

Historically, too, there’s been a perception that maintaining privacy and security is linked with keeping information offline. When it comes to personal consumption, the Japanese are model early adopters. But with public-facing data such as government-issued ID cards, shopping transactions, medical records, and online identifiers like Google’s geolocation services, Japan has consistently opted for control over digitized convenience.

In 2008, a coalition of Japanese lawyers, journalists, and professors demanded that Google scrap its Street View service in Japan because its photos of private property, passersby, and license plates were “a violent infringement on citizens’ privacy.” A year later, Japan’s justice ministry lodged an official protest against Google Earth for posting historical maps of neighborhoods housing burakumin, a group of people historically discriminated against for being among Japan’s lowest-caste citizens.

Google apologized, swiftly changing its entire catalog of Japan images for Street View, with faces, signs, and license plates blurred, and deleting all of its offensive historical maps of Japan’s outcasts.

In recent years, e-money has been slow to take hold in Japan, despite advances during the Covid-19 pandemic. It’s partly because many Japanese — especially those over 65 — balk at leaving digital fingerprints of every transaction.

Easy Luddite laughs aside, it’s becoming increasingly clear that keeping processes offline is no guarantee for security. In just the first half of 2022, Japan has seen an 87% spike in ransomware attacks, one of which forced Toyota to briefly shutter all 14 of its domestic factories. A municipal employee infamously lost the data of an entire township, housed on a USB drive, after a night out drinking. In one analyst’s account, Japan’s digital delinquency could lead to what METI calls a “digital cliff” by 2025, costing the nation over $84 billion annually due to inefficient practices.

Kono’s mission might be morphing into an emergency. But that doesn’t mean he’ll be given the latitude to deal with it, or that it’s even in his interests to.

“I think Kono is grossly overrated by the western media and diplomatic circles because he is fluent in English and talks like an American Republican,” said Nakano. “He is more into media strategy than actual delivery of digital policy, and much more interested in becoming the prime minister one day. So he knows that he should cast a fresh, iconoclastic image to the general public and the media without really offending the party elders.”

Kono’s Japanese-language tweets, in contrast to those on his separate English-language account, are more clerical, less emotional. He links to public service announcements and hiring, not self-deprecating observations. So far, his proclamations are hitting home where they’re meant to: outside of Japan. For the maverick, would-be PM Kono to shift those perceptions inside Japan by March 2023 will take more than ditching a few floppy disks.

September 26, 2022

Watching anime with my parents, by JAPANAMERICA reader and assistant, Fintan Mooney, 17

I was thrilled by the feedback on my first post so I hope you enjoy my second entry. Here, I talk about how my Mom and Dad have different reactions to the anime we watch together.

I’ve re-watched a decent amount of anime with my parents. Together we’ve watched Attack on Titan (3x), Jujutsu Kaisen (4x), Hunter x Hunter (3x), Death Note (2x) and The Promised Neverland (2x). For my dad, the jokes don’t land. He has strong opinions about jokes because he himself is a comedian. He thinks anime can be overwritten: Too much internal dialogue during fights (“if I do this, then that will happen”); too much internal analysis of the opponent. He gets taken aback when there are inappropriate moments. In HxH, Hisoka is always looking for a fight to entertain himself. His desire for a worthy opponent is so strong that he gets aroused when he comes across someone of similar strength.

Dad’s enjoyed Attack on Titan the most so far, interestingly enough. He’s a huge Star Wars fan, and AoT and Star Wars both play with the concept of time jumps.

My mom, on the other hand, is drawn to the heart of the characters. We’ve cried together multiple times: Gon and Killua’s farewell in the final episode; Komugi and Meruem’s final moments together (HxH). She likes the goofy, slapstick humor, and was so invested in Death Note and Light Yagami getting caught that she almost stopped watching when he kept succeeding.

I tell them both that when we watch something, I’m paying more attention to them than to the show. Keeping their attention can be difficult, especially my Dad’s, who seems more prone to sleeping during even the most exciting moments. We’ve made it to the penultimate arc of Hunter x Hunter, and he still hasn’t fully grasped what makes it impactful. When I watched it with my Mom, we had already cried at multiple moments, while my Dad was still falling asleep during almost every episode. Hopefully he pulls through to the end, but it’s not entirely about making sure a parent is always engaged. As long as we get to share these moments, that’s what’s most important to me.