Roland Kelts's Blog, page 3

August 27, 2024

Latest NHK interview: How Japanese arcades are invading the US

I returned to NHK for an interview on the explosive growth of Japanese arcade games in the US--specifically the "UFO Catcher/Crane Games" as they're known in Japan, and more aggressively in the US: "Claw Machines."

Round One and Genda are investing heavily in the US market, opening bricks-and-mortar venues in targeted US regions (like Vegas). The driver? Character goods based on manga and anime characters, of course.

Got a little vociferous on this one.

August 1, 2024

New chat w/Haruki Murakami for The Nikkei

Movie animates Murakami's portraits of empty lives

American writer Nathaniel Rich once claimed that Haruki Murakami, lauded internationally and regularly short-listed for the Nobel Prize in literature, actually writes "genre fiction," the commercial label for stories that repeat formulas, conventions, plots and sometimes whole casts of characters to satisfy reader expectations (think "Game of Thrones" or "Harry Potter"). Genre works are distinguished from the less predictable and less marketable aims of literary fiction -- and have a much better shot at the bestseller list.

American writer Nathaniel Rich once claimed that Haruki Murakami, lauded internationally and regularly short-listed for the Nobel Prize in literature, actually writes "genre fiction," the commercial label for stories that repeat formulas, conventions, plots and sometimes whole casts of characters to satisfy reader expectations (think "Game of Thrones" or "Harry Potter"). Genre works are distinguished from the less predictable and less marketable aims of literary fiction -- and have a much better shot at the bestseller list.The kicker, according to Rich, is that Murakami created his own genre, absorbing literary conceits into a blend of other recognizable storytelling tropes from the realms of noir, fantasy, horror and sci-fi.

The most salient hallmark of the Murakami genre is its fluid shifts between a ruthlessly humdrum reality and poetic, often borderline erotic and prophetic dreamworlds. These shifts can be so seamless and mesmerizing in Murakami's strongest writing that we no longer care about unresolved plots or flat, clunky sentences. But they also make Murakami's works notoriously "unfilmable," ill-suited to the more literal representations of visual media. They are best conjured in the mind, not on the screen.

That hasn't stopped filmmakers from trying. Movies based on Murakami's stories have risen in prominence in recent years, most notably with South Korean director Lee Chang-dong's 2018 "Burning" (adapted from the story "Barn Burning") and Ryusuke Hamaguchi's 2021 "Drive My Car," both of which garnered prestigious awards, the latter an Academy Award for best international feature film in 2022.

Still, having followed Murakami's career for 30 years and interviewed him periodically over 25 of them, I find that all the live-action adaptions miss a key element of the author's sensibility: his lightness of touch.

Still, having followed Murakami's career for 30 years and interviewed him periodically over 25 of them, I find that all the live-action adaptions miss a key element of the author's sensibility: his lightness of touch.I wasn't fully aware of this absence until I saw the latest feature film based on Murakami's prose, Hungarian-British director Pierre Foldes' animated "Blind Willow, Sleeping Woman," released in Japan on July 26.

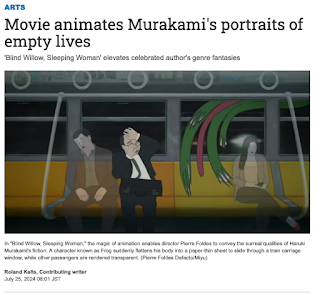

The film combines six short stories from three collections into a single narrative, floating above its source material at an artful distance and letting the audience in on the artifice. It practically winks at the viewer when a charismatic talking frog, adapted from Murakami's "Super-Frog Saves Tokyo," suddenly flattens his body into a paper-thin sheet to slip through the slits of a door frame and rail carriage window. Like Murakami's fiction, "Blind Willow" carries some heavy ideas without being weighed down by them.

Murakami, who has publicly endorsed the film, says that he even appreciates the scenes Foldes created to augment his original work. "Pierre has added a number of episodes that are not in any of my stories he adapted," he told me in an exclusive interview. "I love that kind of freedom, and I think it's important for filmmakers to exercise it."

The magic of animation is that it forces you into a dream from its opening frames. Not unlike literature itself, which is finally just lines of symbols on a page that mean nothing until you decode them, animated worlds require you to abandon your sense-perceptions of reality in order to decipher and embrace their stylized imagery.

The magic of animation is that it forces you into a dream from its opening frames. Not unlike literature itself, which is finally just lines of symbols on a page that mean nothing until you decode them, animated worlds require you to abandon your sense-perceptions of reality in order to decipher and embrace their stylized imagery.Once you do, your psychological guard against "uncanny valley" expectations of visual representations is dropped and a portal opens for dreams and the emotions they generate. Isao Takahata's deeply moving animated masterpiece "Grave of the Fireflies," for example, about two orphaned siblings struggling to survive in postwar Japan, is severely diluted in its live-action television and film adaptations. Illustrations give us the paradoxical distance from realism that allows us to experience powerful emotions intimately.

"Blind Willow" starts with two earthquakes: a real one in Tohoku, the northern region of Japan's main Honshu island, echoing the disaster that struck the region in 2011, and a nightmare quake in youthful salaryman Komura's mind, set in a crumbling underground passageway he descends via a barely sketched staircase, suspended in the dark of his dreams.

Komura wakes at 3 a.m. in his suburban Tokyo apartment to find his wife Kyoko staring listlessly at nonstop disaster reportage on television from a blood red sofa, a cat curled up beside her. She does not speak to Komura. He opens the window to smoke a cigarette while a jet flies silently overhead.

Murakami readers will recognize the scenario from "UFO in Kushiro," one of six intertwined narratives in his most cohesive and pitch-perfect story collection, "After the Quake," first published in 2000 and translated in 2002.

Murakami had written the collection in response to Japan's two disasters of 1995, the Great Hanshin earthquake in his native hometown of Kobe and the sarin gas attacks by religious cult Aum Shinrikyo in Tokyo, his adopted city, two months later. The English translation resonated with American readers in particular after the 2001 terrorist attacks in the U.S., and Murakami told me at the time that he recognized the universality of the stories. "If the book was only about the earthquake, the sympathy would be weaker," he said, "but it's a book about the violence in nature and in human beings. I feel like I'm walking in a deep forest, in the darkness of the underground."

Director Foldes, who also wrote the film's screenplay and score, performed its music and voice-acted the talking frog, fully grasps the obsessions binding the Murakami genre, and his decision to adapt six stories from three different books elevates "Blind Willow" from what would have been a captivating anecdotal short film into an epic portrait of three empty lives in suspension.

Director Foldes, who also wrote the film's screenplay and score, performed its music and voice-acted the talking frog, fully grasps the obsessions binding the Murakami genre, and his decision to adapt six stories from three different books elevates "Blind Willow" from what would have been a captivating anecdotal short film into an epic portrait of three empty lives in suspension.Komura bears a striking resemblance to a younger version of Murakami. He also shares an office with Katagiri, the older, balding everyman salaryman of "Super-Fog Saves Tokyo," who will encounter the talking frog in his cramped apartment and be called on by the amphibian to save the city from a massive quake, caused by a giant enraged worm living underground. The story practically begged to be animated.

Komura and Kyoko's cat, Watanabe, disappears into their neighborhood's grass thickets and abandoned homes, sending Komura searching through the deep forest of Murakami's metaphor. Kyoko, too, will disappear, leaving Komura with a line of dialogue whose recitation haunts the film like a bleak diagnosis: "Living with you is like living with a chunk of air."

The animation incorporates a blend of techniques that make its visuals seem at once hyper-realistic and spectral. Foldes used an intuitive process he now refers to as "live-action animation," shooting actors performing the storyboarded scenes and dialogue, then making 3D sculptures of their heads to give his animators the freedom to recreate characters' emotions through the expressive lines of 2D drawing. The result may initially remind some viewers of the rotoscoping approach used in films like Richard Linklater's "Waking Life," but as the film proceeds it becomes clear that "Blind Willow" is altogether more subtle and minimalistic, reducing the visual data of live action imagery to the pared down minimalist aesthetics found in classic manga and anime, as well as traditional woodblock prints and scroll paintings.

A raised eyebrow or downturned lip on the carefully etched faces of main characters can reveal a rush of inner turmoil, while surrounding characters in a cafe or train car are blurred outlines, murmuring around the outer edges of daily life.

A raised eyebrow or downturned lip on the carefully etched faces of main characters can reveal a rush of inner turmoil, while surrounding characters in a cafe or train car are blurred outlines, murmuring around the outer edges of daily life."All of my references in animation are Japanese," Foldes said, citing a list of anime auteurs including Mamoru Oshii, Katsuhiro Otomo and Hayao Miyazaki. "I was always a great admirer of Japanese line drawings and their use of empty space. It's what's between the lines, the unsaid, that interests me -- a quality I find in Murakami's writing, too. Animation allows me to go further than live action because I can recreate a form of 'augmented reality' that my mind understands, as opposed to what I see and hear. And what my mind understands is what's between the lines."

Foldes has never lived in Japan but took copious notes during his few visits, writing the first draft of his script eating bento lunchboxes on the shinkansen bullet train as he stopped in small towns along the way and sketched the architecture and scenery of modern Japan. The backdrops are acutely captured, rendered with a perceptive freshness that perhaps only an outsider can bring.

"There isn't a scene that strikes me as false," Murakami said, praising the director's "lively and precise descriptions of Japanese places and the way people lead their everyday lives. Pierre pays attention to small details that Japanese people take for granted and just ignore."

In plumbing the inner lives of his three main characters, Foldes reveals his strengths as a storyteller, mirroring Murakami's most effective transitions from sentimentality to genuine pathos. Komura, Kyoko and Katagiri each confront their inertia through documentary-style interviews conducted by secondary characters. Komura's ailing child relative and a young woman in Hokkaido draw out his rage and dissatisfaction with life; Kyoko is provoked into action by an aging restaurant owner and curious barfly; Katagiri's wrenching confession -- "My life is horrible" -- emerges when Frog presses him to help save Tokyo from Worm's impending earthquake. "I don't have a single person who likes me," Katagiri says, his lined face crinkling in close-up as he bemoans his failures at work and in his social life along with his encroaching middle-aged illnesses, ugliness and crushing solitude: "All I do is eat, sleep and s---. I don't even know why I'm still living."

In plumbing the inner lives of his three main characters, Foldes reveals his strengths as a storyteller, mirroring Murakami's most effective transitions from sentimentality to genuine pathos. Komura, Kyoko and Katagiri each confront their inertia through documentary-style interviews conducted by secondary characters. Komura's ailing child relative and a young woman in Hokkaido draw out his rage and dissatisfaction with life; Kyoko is provoked into action by an aging restaurant owner and curious barfly; Katagiri's wrenching confession -- "My life is horrible" -- emerges when Frog presses him to help save Tokyo from Worm's impending earthquake. "I don't have a single person who likes me," Katagiri says, his lined face crinkling in close-up as he bemoans his failures at work and in his social life along with his encroaching middle-aged illnesses, ugliness and crushing solitude: "All I do is eat, sleep and s---. I don't even know why I'm still living."Murakami is especially fond of the way this stark cinematic realism grounds the film's dream sequences. "The tempo of the story, the way the characters talk to each other, their facial expressions -- they were all so true to life that I almost felt like I was watching a live-action film.

"This may sound a bit rude," he added, "but it doesn't feel typically anime-ish."

No particular fan of animation, as he has told me in the past, Murakami said that he watched "Blind Willow" twice. Last month he agreed to join Foldes onstage for a post-screening dialogue at the Waseda June Literary Festival in Tokyo, hosted by the university's International House of Literature, otherwise known as the Haruki Murakami Library.

Before a packed auditorium, the author told the director that the film felt so original and innovative he could not remember what he wrote in the original stories that inspired it: "I had no idea what would happen next."

July 27, 2024

Haruki Murakami finally gets his film: Japan Times column

'Blind Willow, Sleeping Woman' is an immersive journey into Murakami's world

The first time I met Haruki Murakami, on a hot afternoon in the summer of 1999, he greeted my question about film adaptations of his fiction with a shrug. I knew the author had studied film as an undergraduate at Waseda University and was something of a Jean-Luc Godard aficionado, but the only two directors he said he would green-light immediately were David Lynch and Woody Allen — the latter of whom had apparently tried to contact Murakami’s office years earlier when the author was out of the country.

The first time I met Haruki Murakami, on a hot afternoon in the summer of 1999, he greeted my question about film adaptations of his fiction with a shrug. I knew the author had studied film as an undergraduate at Waseda University and was something of a Jean-Luc Godard aficionado, but the only two directors he said he would green-light immediately were David Lynch and Woody Allen — the latter of whom had apparently tried to contact Murakami’s office years earlier when the author was out of the country.Murakami was hard to find back then, especially in Japan. Notoriously camera-shy after he shot to fame domestically with his hugely popular third novel, “Norwegian Wood,” Murakami refused to appear on television or magazine covers, and had given only one public reading to support victims of the 1995 Great Hanshin Earthquake in his native hometown of Kobe.

As Murakami’s fame and readership grew, filmmakers came knocking. He said yes to Vietnamese-born French director Tran Anh Hung, who met with Murakami in Tokyo to win approval for his 2010 movie version of “Norwegian Wood.” (Murakami told me that he liked Tran’s sense of time and storytelling rhythms, which felt distinctly Asian to him.) In 2018, South Korean director Lee Chang-dong’s brutal “Burning” (adapted from Murakami’s “Barn Burning”) featured Korean American actor Steven Yeun, and Ryusuke Hamaguchi’s lugubrious “Drive My Car” picked up an Oscar for best international feature film in 2022.

Though I admire the craft and sometimes clever diversions from source material in each film (Hamaguchi’s multilingual “Uncle Vanya” staging is particularly deft), none give me half the pleasure of Murakami’s best writing. As standalone films, they might work perfectly well, but as adaptations of his fiction they all feel lopsided — too reverentially desperate to convey the writer’s alleged profundity without capturing his bemused mockery of such pretensions, his essential, ultimately life-affirming and sometimes giddy cheekiness. They privilege his Chekhovian voids over his Kafkaesque crazy.

Drive My Car Over the years, Murakami has insisted to me that he is “not an intellectual,” that he chooses simple words to write about regular people, and that he far prefers readers to critics or academics. All a writer really needs to survive, he has often told me, is enough readers.

Drive My Car Over the years, Murakami has insisted to me that he is “not an intellectual,” that he chooses simple words to write about regular people, and that he far prefers readers to critics or academics. All a writer really needs to survive, he has often told me, is enough readers.While I generally prefer books to movies, I do understand that they are two radically different types of media, and that the hardest thing to transpose onto the screen is a writer’s tone, the feel and atmosphere of a unique voice on the page, crafted through their word choices and the cadences of good prose.

Yet for a certain kind of reader, it’s exactly a writer’s tone, slippery though it may be to define, far more than plot, character development or descriptive embellishment, that keeps us turning pages. We return again and again to a specific author’s worlds simply because we love the words that make them.

For me, “Blind Willow, Sleeping Woman,” the latest feature-length adaptation of Murakami’s fiction (in theaters from July 26) and the first to be animated, comes the closest to nailing it.

Blind Willow, Sleeping Woman Directed by Paris-raised Hungarian British writer, composer and painter Pierre Foldes, “Blind Willow” incorporates six Murakami short stories from three books into a single intertwined narrative that looks, feels and moves like we’re in Murakamiland. It wryly refuses to take itself or its world too seriously, which, like Murakami’s best fiction, makes its openly emotional scenes heartbreaking.

Blind Willow, Sleeping Woman Directed by Paris-raised Hungarian British writer, composer and painter Pierre Foldes, “Blind Willow” incorporates six Murakami short stories from three books into a single intertwined narrative that looks, feels and moves like we’re in Murakamiland. It wryly refuses to take itself or its world too seriously, which, like Murakami’s best fiction, makes its openly emotional scenes heartbreaking.One of the author’s most likable and memorable characters is an oversized talking frog named Frog (how’s that for anti-intellectual?) from “Super-Frog Saves Tokyo,” a story seemingly tailored to the art of animation. Foldes’ inclusion of Frog in his cast of main characters, a trio of lonely Tokyoites named Komura, Kyoko and Katagiri, injects the film with color and self-aware humor (a Murakami hallmark), enabling him to subvert the stories of three dissatisfied but otherwise dully ponderous middle-class humanoids with playful deviance.

As in the original story, Frog gleefully misquotes Nietzsche and namedrops “Anna Karenina,” suddenly slamming his webbed palms on a kitchen table during a quiet conversation over tea as he urges the balding, self-pitying 40-something Katagiri to help save the city’s residents from an imminent earthquake. “I am not crazy, and you are not dreaming,” Frog says to a gobsmacked Katagiri. “This is positively serious!”

The disaster, he explains, carefully enunciating with the faint condescension of a pedant, will be caused by Worm, who is magnificently realized onscreen as an eyeless, segmented, sharp-toothed and legless centipede roaring to life underground.

“Worm is a symbol of the evil inside us, the evil within,” Murakami told me in 2002, and the illustrated version of Worm in “Blind Willow” is enough to make viewers shudder at its parasitical rage.

Helping enormously is Foldes’ early establishment of his narrative parameters. The porous border between reality and dreams is introduced in the opening scene during a nightmare sequence that incorporates the earthquake motif — an urgent reminder of what’s at stake in the lives of its otherwise weakly motivated principals. Indeed, if any aspect of the story feels dated, it’s the self-absorbed redundancies of Murakami’s stock human characters, whose soft-focus regrets and habitual ambivalence feel a little late-1990s when seen in the 2020s, a bit boorishly Boomerish. Frog’s battle with Worm and his unlikely partnership with the timid Katagiri lend the film the urgency of a good role-playing game, a medium Murakami has cited as a modern model for literary storytelling.

Helping enormously is Foldes’ early establishment of his narrative parameters. The porous border between reality and dreams is introduced in the opening scene during a nightmare sequence that incorporates the earthquake motif — an urgent reminder of what’s at stake in the lives of its otherwise weakly motivated principals. Indeed, if any aspect of the story feels dated, it’s the self-absorbed redundancies of Murakami’s stock human characters, whose soft-focus regrets and habitual ambivalence feel a little late-1990s when seen in the 2020s, a bit boorishly Boomerish. Frog’s battle with Worm and his unlikely partnership with the timid Katagiri lend the film the urgency of a good role-playing game, a medium Murakami has cited as a modern model for literary storytelling.Still, not even Foldes expected Murakami to join him onstage last month for a live dialogue after a screening of the film at Waseda’s June Literary Festival in Tokyo, hosted by the International House of Literature, home to the author’s archives. Murakami praised the film (he saw it twice) and noted that he first included Frog in his 2000 story collection “After the Quake” when the character “just appeared from another world,” and he had to convince his wary editor to keep the amphibian in the book.

In 2003, I helped Murakami practice reading the English translation of “Super-Frog Saves Tokyo” in New York City, advising him that a frog’s croak in Japanese (“kero, kero”) is “ribbit” in English. In “Blind Willow,” Foldes himself provides Frog’s pitch-perfect voice. “I love Frog so much I couldn’t refrain from playing him in both French and English,” Foldes told me after the Waseda event. “That Murakami loved my film and my Frog is immensely gratifying.”

In 2003, I helped Murakami practice reading the English translation of “Super-Frog Saves Tokyo” in New York City, advising him that a frog’s croak in Japanese (“kero, kero”) is “ribbit” in English. In “Blind Willow,” Foldes himself provides Frog’s pitch-perfect voice. “I love Frog so much I couldn’t refrain from playing him in both French and English,” Foldes told me after the Waseda event. “That Murakami loved my film and my Frog is immensely gratifying.”It's hardly a spoiler to tell you that Frog defeats Worm and saves Tokyo. But he may have also saved this brilliant and beautiful movie from being another solemn Murakami adaptation that misses out on the fun. *

Japanese-dubbed and subtitled versions of “Blind Willow, Sleeping Woman” will be released in cinemas nationwide from July 26. For more information, visit eurospace.co.jp/BWSW (Japanese only).

Roland Kelts is a visiting professor at Waseda University and the author of “Japanamerica: How Japanese Pop Culture has Invaded the U.S.” and “The Art of Blade Runner: Black Lotus.”

July 19, 2024

"Tokyo Cowboy" is a JapanAmerican winner: Japan Times column

‘Tokyo Cowboy’ strikes balance between cross-cultural comedy and fish-out-of-water tale

Thirty-six years ago, American director Marc Marriott lived in Japan as a missionary and worked as a filmmaking apprentice to Yoji Yamada, the legendary director of the “Tora-san” film series. When Mariott returned to the U.S., he came across an article in an American magazine that stirred his imagination.

During the late 1980s, the height of Japan’s bubble-era economy, a Japanese beef company purchased a cattle ranch in Montana to expand its operations and better serve a meat-mad Japanese consumer base. To educate its staff in the ways of American cattle farming and teach Americans about the Japanese palate, the company sent a handful of salarymen to live and work on the ranch.

“That idea of this clash of cultures, Japanese cowboys on an American ranch,” Marriott tells me. “I just thought: There’s a movie in there, a great story.”

At a company meeting, Hideki proposes his plan to revive the fortunes of a Montana cattle ranch acquired by his firm as part of its buyout of a domestic chocolate maker. His idea is to raise bespoke cattle for the more profitable Japanese wagyu instead.

Within the film’s first 15 minutes, set in and around the skyscrapers of Shinjuku’s west side, it’s clear that the idea is a non-starter. Veteran Kobe beef farmer Naohiro Wada (a dryly funny Jun Kimura) tells Hideki as much at an izakaya (traditional Japanese pub), adding that although wagyu from outside Japan can never be the real thing and is in fact illegal, he’s still game to get paid for the scam.

After Hideki and Wada land in Montana, the story expands in tandem with its gorgeous cinematography, capturing the vast plains and jagged peaks of so-called “big sky” country — a galaxy apart from Tokyo’s pinched warrens and alleyways. But the action may make Japanese viewers (and foreign residents of Japan) grin and grimace at once.

After Hideki and Wada land in Montana, the story expands in tandem with its gorgeous cinematography, capturing the vast plains and jagged peaks of so-called “big sky” country — a galaxy apart from Tokyo’s pinched warrens and alleyways. But the action may make Japanese viewers (and foreign residents of Japan) grin and grimace at once.The U.S. domestic carrier connecting the duo from San Francisco to a local airport unapologetically loses Hideki’s suitcase. An airline staffer, making no concessions to her customers’ native tongue, asks Hideki for his Montana lodge address in rapid-fire colloquialisms that even a U.S. native might need repeating. The lodge itself has spotty Wi-Fi and a broken laundromat, and its concierge is a young female anime fan practicing pidgin Japanese via Duolingo. Every store in the vicinity closes by sundown.

Welcome to America.

Kimura’s Wada is the more fluent of the two, but he’s soon hospitalized after falling from a mechanical bull in the local saloon, leaving Hideki to sputter alone in broken English. His linguistic foibles are sometimes unintentionally comical (a PowerPoint presentation he made for the ranchers opens with, “Let’s Eat Everyone!”) without being jokey or obscene, and anyone who has struggled to test-run an acquired language in its native land will nod in empathy.

Turns out it wasn’t such a leap for actor Iura.

“Oh, it was totally real,” says Fujitani, who was raised bilingually in Japan and the U.S. and now lives in Portland, Oregon. She was both Iura’s onscreen partner and his on-set interpreter. “Sometimes he was okay, but other times I’d have to say, ‘No, you have to hit your ‘Ls’ hard, like this, otherwise no one will understand you.’ He would say, ‘But I don’t want to practice too much or I won’t sound like Hideki.’ And I told him, ‘Don’t worry about that.’”

Unsurprisingly, Hideki faces headwinds from all directions of the 70,000-acre Lazy River Ranch. One of the grizzled male ranch hands reminds him that corn, a staple of the wagyu cow diet, can’t be grown in the local soil. He slides off the first horse he tries to ride, falling face-first into the mud and ruining his only suit as he awaits his missing luggage, which never arrives. His two-wheel drive rental car is shat upon by a flock of chickens and marooned on a rock-studded dirt road. The Wi-Fi signal in his room keeps flickering out, causing Keiko to freeze mid-sentence during a Skype call from Tokyo.

All of this is delivered without the mean-spiritedness of ridicule for easy laughs. Even when Hideki’s predicament is harsh, the film’s humor is gentle, and the cultural differences between the U.S. and Japan are balanced and knowingly revealed. As Hideki refuels his sedan at a Montana gas station and pops into its convenience store for a quick meal, he is aghast at the enormous plastic soda cup labeled “small drink,” his face blanching as he raises a spoon from a vat of gooey processed cheese and tucks into an anemic hot dog.

Hideki’s friendship with Mexican ranch hand Javier (the quietly magnetic Goya Robles) enlarges his world, creating an alliance of outsiders in the otherwise strictly Caucasian cowboy universe, but also forcing him in the film’s moving denouement to confront the question faced by every cross-cultural sojourner: Are you really running toward something or just running away?

Roland Kelts is a visiting professor at Waseda University and the author of “Japanamerica: How Japanese Pop Culture has Invaded the U.S.” and “The Art of Blade Runner: Black Lotus.”

"Tokyo Cowboy" is a JapanAmerican winner

‘Tokyo Cowboy’ strikes balance between cross-cultural comedy and fish-out-of-water tale

Thirty-six years ago, American director Marc Marriott lived in Japan as a missionary and worked as a filmmaking apprentice to Yoji Yamada, the legendary director of the “Tora-san” film series. When Mariott returned to the U.S., he came across an article in an American magazine that stirred his imagination.

During the late 1980s, the height of Japan’s bubble-era economy, a Japanese beef company purchased a cattle ranch in Montana to expand its operations and better serve a meat-mad Japanese consumer base. To educate its staff in the ways of American cattle farming and teach Americans about the Japanese palate, the company sent a handful of salarymen to live and work on the ranch.

“That idea of this clash of cultures, Japanese cowboys on an American ranch,” Marriott tells me. “I just thought: There’s a movie in there, a great story.”

At a company meeting, Hideki proposes his plan to revive the fortunes of a Montana cattle ranch acquired by his firm as part of its buyout of a domestic chocolate maker. His idea is to raise bespoke cattle for the more profitable Japanese wagyu instead.

Within the film’s first 15 minutes, set in and around the skyscrapers of Shinjuku’s west side, it’s clear that the idea is a non-starter. Veteran Kobe beef farmer Naohiro Wada (a dryly funny Jun Kimura) tells Hideki as much at an izakaya (traditional Japanese pub), adding that although wagyu from outside Japan can never be the real thing and is in fact illegal, he’s still game to get paid for the scam.

After Hideki and Wada land in Montana, the story expands in tandem with its gorgeous cinematography, capturing the vast plains and jagged peaks of so-called “big sky” country — a galaxy apart from Tokyo’s pinched warrens and alleyways. But the action may make Japanese viewers (and foreign residents of Japan) grin and grimace at once.

After Hideki and Wada land in Montana, the story expands in tandem with its gorgeous cinematography, capturing the vast plains and jagged peaks of so-called “big sky” country — a galaxy apart from Tokyo’s pinched warrens and alleyways. But the action may make Japanese viewers (and foreign residents of Japan) grin and grimace at once.The U.S. domestic carrier connecting the duo from San Francisco to a local airport unapologetically loses Hideki’s suitcase. An airline staffer, making no concessions to her customers’ native tongue, asks Hideki for his Montana lodge address in rapid-fire colloquialisms that even a U.S. native might need repeating. The lodge itself has spotty Wi-Fi and a broken laundromat, and its concierge is a young female anime fan practicing pidgin Japanese via Duolingo. Every store in the vicinity closes by sundown.

Welcome to America.

Kimura’s Wada is the more fluent of the two, but he’s soon hospitalized after falling from a mechanical bull in the local saloon, leaving Hideki to sputter alone in broken English. His linguistic foibles are sometimes unintentionally comical (a PowerPoint presentation he made for the ranchers opens with, “Let’s Eat Everyone!”) without being jokey or obscene, and anyone who has struggled to test-run an acquired language in its native land will nod in empathy.

Turns out it wasn’t such a leap for actor Iura.

“Oh, it was totally real,” says Fujitani, who was raised bilingually in Japan and the U.S. and now lives in Portland, Oregon. She was both Iura’s onscreen partner and his on-set interpreter. “Sometimes he was okay, but other times I’d have to say, ‘No, you have to hit your ‘Ls’ hard, like this, otherwise no one will understand you.’ He would say, ‘But I don’t want to practice too much or I won’t sound like Hideki.’ And I told him, ‘Don’t worry about that.’”

Unsurprisingly, Hideki faces headwinds from all directions of the 70,000-acre Lazy River Ranch. One of the grizzled male ranch hands reminds him that corn, a staple of the wagyu cow diet, can’t be grown in the local soil. He slides off the first horse he tries to ride, falling face-first into the mud and ruining his only suit as he awaits his missing luggage, which never arrives. His two-wheel drive rental car is shat upon by a flock of chickens and marooned on a rock-studded dirt road. The Wi-Fi signal in his room keeps flickering out, causing Keiko to freeze mid-sentence during a Skype call from Tokyo.

All of this is delivered without the mean-spiritedness of ridicule for easy laughs. Even when Hideki’s predicament is harsh, the film’s humor is gentle, and the cultural differences between the U.S. and Japan are balanced and knowingly revealed. As Hideki refuels his sedan at a Montana gas station and pops into its convenience store for a quick meal, he is aghast at the enormous plastic soda cup labeled “small drink,” his face blanching as he raises a spoon from a vat of gooey processed cheese and tucks into an anemic hot dog.

Hideki’s friendship with Mexican ranch hand Javier (the quietly magnetic Goya Robles) enlarges his world, creating an alliance of outsiders in the otherwise strictly Caucasian cowboy universe, but also forcing him in the film’s moving denouement to confront the question faced by every cross-cultural sojourner: Are you really running toward something or just running away?

Roland Kelts is a visiting professor at Waseda University and the author of “Japanamerica: How Japanese Pop Culture has Invaded the U.S.” and “The Art of Blade Runner: Black Lotus.”

June 5, 2024

Police guitarist Andy Summers on Akira Kurosawa and photographing Japan: Japan Times column

Andy Summers captures life on and off stage in moody monochrome

With Police guitarist Andy Summers in Ginza

With Police guitarist Andy Summers in Ginza In 1980, one of the first music videos for then up-and-coming British rock trio The Police was filmed on the Tokyo subway. In the footage, three blond musicians — bass player/singer Sting, guitarist Andy Summers and American drummer Stewart Copeland — mug for the camera against a backdrop of anonymous Japanese commuters, lip-syncing into walkie-talkies to their aptly chosen hit single, “So Lonely.”

But Summers would soon find himself on the other side of the lens, pursuing a passion for photography that he had nurtured since his adolescence in Bournemouth, England, where he fell in love with black-and-white art films from around the world shown at a local cinema, including early masterworks by Japanese director Akira Kurosawa. When The Police was hitting peak popularity in 1983, Summers tracked down American photographer Ralph Gibson in New York, who helped him publish his debut photo book, “Throb.”

Four decades later, at age 81, Summers returned to Japan last month to open two exhibitions of his work at galleries in Tokyo and Kyoto operated by German camera-maker Leica. Both shows are based on his latest book, “A Series of Glances,” and will run through July 7.

Sporting a royal blue jacket and hoisting a flute of champagne, Summers welcomed the invitation-only crowd on opening day in Ginza by dryly confessing that it wasn't his usual gig. “I’m used to standing up a little bit higher on a stage with a guitar,” he said, stretching his left arm out to an imaginary fretboard. “It’s very nice to be back in Tokyo and I've played many concerts here, but right now, I’m completely jet lagged.”

The following morning, Summers met me two blocks from the Leica Gallery at The Peninsula Tokyo hotel, dressed in a dark gray sweatshirt and sipping coffee refills to stave off fatigue. Far more than just a tour stop or music video prop, he says, Japan has been a source of lifelong fascination since he saw Kurosawa’s films in Bournemouth when he was 15.

“Kurosawa got into my head at a young age, those early black-and-white films before he started his samurai phase,” Summers says. “I sort of soaked up Japanese culture through those movies. Later, I was into Zen and a lot of other things that were very appealing to me. And much later, when I got into photography, it all started to come back out in a way that I couldn’t necessarily express on the guitar.”

Summers is a decade older than his Police bandmates, and was raised in an England still ravaged by war. School buildings were blown out, bridges reduced to twisted frames, beaches bombed and covered in barbed wire. Summers saw echoes of his childhood environs in Kurosawa’s late 1940s films, such as “Stray Dog” and his personal favorite, “Drunken Angel,” both of which feature seedy characters in dark and ruinous Tokyo backstreets. These films resonated with a British youth surrounded by remnants of the same global calamity thousands of miles away.

“As kids in the English countryside, we were always coming across these little dumps in the bushes with gas masks,” he says. “It was grim. And early on, Kurosawa was showing these gangsters and thieves and addicts passing ramshackle houses and downtrodden alleyways, these slum areas. Everything is shit and looks terrible after everything that happened in the war, but the emotional relationships are so powerful and the cinematography is brilliant.”

Summers’ own early work focuses heavily on his world-beating band and a lifestyle dominated by rock stardom. Touring almost constantly, Summers tells me he used to sneak out of his hotel at night wearing a skullcap and hoodie with a black camera hidden away so he wouldn't be recognized as either a famous popstar or a photographer. “I was that guy,” he says.

In Japan, he would wander through the warrens and alleyways of neighborhoods like Shinjuku's Golden Gai entertainment district, snapping shots of street signs, architecture and nightlife that he found fresher and “more layered” than the familiar imagery of New York or London. The locations in his current Tokyo exhibit range from South America to Asia to Europe, and feature casual street scenes and religious ceremonies, all photographed in moody monochrome and bathed in rich shadows.

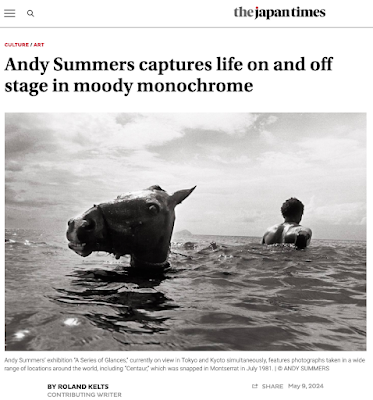

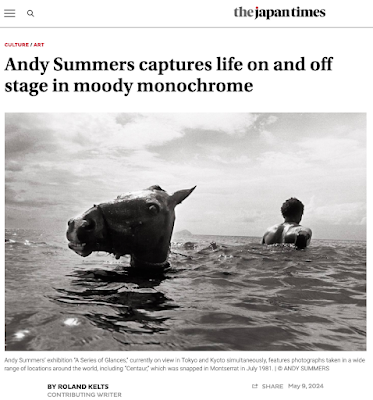

In Japan, he would wander through the warrens and alleyways of neighborhoods like Shinjuku's Golden Gai entertainment district, snapping shots of street signs, architecture and nightlife that he found fresher and “more layered” than the familiar imagery of New York or London. The locations in his current Tokyo exhibit range from South America to Asia to Europe, and feature casual street scenes and religious ceremonies, all photographed in moody monochrome and bathed in rich shadows.The best of them have nothing to do with life in a rock band, but visually reveal Summers’ musical personality, particularly his taste for abstraction and eccentricity. In “Nazarenos,” a nighttime procession of priests during Santa Semana, or Holy Week, in Seville, Spain, is ghostly and haunting, yet Summers’ focus on one priest’s eyes pushes it toward the menacing. Similarly, after a few minutes of looking at “Centaur,” the effect of the waterborne horse in Montserrat with its eyes fixed on the camera lens shifts from the comically absurd into the quietly terrifying.

After six years and five original albums, The Police disbanded in early 1984, less than a year after releasing their bestselling record, “Synchronicity,” which yielded one of the world’s most popular and heavily downloaded pop singles, “Every Breath You Take.” The success of The Police, however, gave Summers a platform, and he has put it to good use, recording 15 solo albums since “Synchronicity,” publishing five books of photographs, a collection of short stories and an autobiography, and contributing essays to a book of Gibson’s photographs, all while expanding his musical palette through ongoing collaborations with avant garde guitarist Robert Fripp, formerly of progressive rock icons King Crimson, and a team of Brazilian musicians. His photos have been exhibited in cities throughout Europe and North America, and in Brazil, Australia and China.

At an age when many musicians give up touring, Summers will hit the road in the U.S. later this month with a multimedia solo show called “The Cracked Lens + A Missing String,” which weaves together his photography, music and storytelling into a single performance, a project he hopes to bring to Japan. After years of being shushed by Police bandleader Sting, Summers is now free to chat all night with the audience about life behind his guitar and his camera. Based on our two-hour conversation in Tokyo, it’s something he relishes and does very well. • Andy Summers’ “A Series of Glances” is currently on view at the Leica Gallery in Tokyo and Kyoto through July 7. For more information, visit leica-camera.com/en-int/event/leica-gallery-tokyo/andy-summers.

Police guitarist Andy Summers on Akira Kurosawa and photographing Japan: Japan Times

Andy Summers captures life on and off stage in moody monochrome

With Police guitarist Andy Summers in Ginza

With Police guitarist Andy Summers in Ginza In 1980, one of the first music videos for then up-and-coming British rock trio The Police was filmed on the Tokyo subway. In the footage, three blond musicians — bass player/singer Sting, guitarist Andy Summers and American drummer Stewart Copeland — mug for the camera against a backdrop of anonymous Japanese commuters, lip-syncing into walkie-talkies to their aptly chosen hit single, “So Lonely.”

But Summers would soon find himself on the other side of the lens, pursuing a passion for photography that he had nurtured since his adolescence in Bournemouth, England, where he fell in love with black-and-white art films from around the world shown at a local cinema, including early masterworks by Japanese director Akira Kurosawa. When The Police was hitting peak popularity in 1983, Summers tracked down American photographer Ralph Gibson in New York, who helped him publish his debut photo book, “Throb.”

Four decades later, at age 81, Summers returned to Japan last month to open two exhibitions of his work at galleries in Tokyo and Kyoto operated by German camera-maker Leica. Both shows are based on his latest book, “A Series of Glances,” and will run through July 7.

Sporting a royal blue jacket and hoisting a flute of champagne, Summers welcomed the invitation-only crowd on opening day in Ginza by dryly confessing that it wasn't his usual gig. “I’m used to standing up a little bit higher on a stage with a guitar,” he said, stretching his left arm out to an imaginary fretboard. “It’s very nice to be back in Tokyo and I've played many concerts here, but right now, I’m completely jet lagged.”

The following morning, Summers met me two blocks from the Leica Gallery at The Peninsula Tokyo hotel, dressed in a dark gray sweatshirt and sipping coffee refills to stave off fatigue. Far more than just a tour stop or music video prop, he says, Japan has been a source of lifelong fascination since he saw Kurosawa’s films in Bournemouth when he was 15.

“Kurosawa got into my head at a young age, those early black-and-white films before he started his samurai phase,” Summers says. “I sort of soaked up Japanese culture through those movies. Later, I was into Zen and a lot of other things that were very appealing to me. And much later, when I got into photography, it all started to come back out in a way that I couldn’t necessarily express on the guitar.”

Summers is a decade older than his Police bandmates, and was raised in an England still ravaged by war. School buildings were blown out, bridges reduced to twisted frames, beaches bombed and covered in barbed wire. Summers saw echoes of his childhood environs in Kurosawa’s late 1940s films, such as “Stray Dog” and his personal favorite, “Drunken Angel,” both of which feature seedy characters in dark and ruinous Tokyo backstreets. These films resonated with a British youth surrounded by remnants of the same global calamity thousands of miles away.

“As kids in the English countryside, we were always coming across these little dumps in the bushes with gas masks,” he says. “It was grim. And early on, Kurosawa was showing these gangsters and thieves and addicts passing ramshackle houses and downtrodden alleyways, these slum areas. Everything is shit and looks terrible after everything that happened in the war, but the emotional relationships are so powerful and the cinematography is brilliant.”

Summers’ own early work focuses heavily on his world-beating band and a lifestyle dominated by rock stardom. Touring almost constantly, Summers tells me he used to sneak out of his hotel at night wearing a skullcap and hoodie with a black camera hidden away so he wouldn't be recognized as either a famous popstar or a photographer. “I was that guy,” he says.

In Japan, he would wander through the warrens and alleyways of neighborhoods like Shinjuku's Golden Gai entertainment district, snapping shots of street signs, architecture and nightlife that he found fresher and “more layered” than the familiar imagery of New York or London. The locations in his current Tokyo exhibit range from South America to Asia to Europe, and feature casual street scenes and religious ceremonies, all photographed in moody monochrome and bathed in rich shadows.

In Japan, he would wander through the warrens and alleyways of neighborhoods like Shinjuku's Golden Gai entertainment district, snapping shots of street signs, architecture and nightlife that he found fresher and “more layered” than the familiar imagery of New York or London. The locations in his current Tokyo exhibit range from South America to Asia to Europe, and feature casual street scenes and religious ceremonies, all photographed in moody monochrome and bathed in rich shadows.The best of them have nothing to do with life in a rock band, but visually reveal Summers’ musical personality, particularly his taste for abstraction and eccentricity. In “Nazarenos,” a nighttime procession of priests during Santa Semana, or Holy Week, in Seville, Spain, is ghostly and haunting, yet Summers’ focus on one priest’s eyes pushes it toward the menacing. Similarly, after a few minutes of looking at “Centaur,” the effect of the waterborne horse in Montserrat with its eyes fixed on the camera lens shifts from the comically absurd into the quietly terrifying.

After six years and five original albums, The Police disbanded in early 1984, less than a year after releasing their bestselling record, “Synchronicity,” which yielded one of the world’s most popular and heavily downloaded pop singles, “Every Breath You Take.” The success of The Police, however, gave Summers a platform, and he has put it to good use, recording 15 solo albums since “Synchronicity,” publishing five books of photographs, a collection of short stories and an autobiography, and contributing essays to a book of Gibson’s photographs, all while expanding his musical palette through ongoing collaborations with avant garde guitarist Robert Fripp, formerly of progressive rock icons King Crimson, and a team of Brazilian musicians. His photos have been exhibited in cities throughout Europe and North America, and in Brazil, Australia and China.

At an age when many musicians give up touring, Summers will hit the road in the U.S. later this month with a multimedia solo show called “The Cracked Lens + A Missing String,” which weaves together his photography, music and storytelling into a single performance, a project he hopes to bring to Japan. After years of being shushed by Police bandleader Sting, Summers is now free to chat all night with the audience about life behind his guitar and his camera. Based on our two-hour conversation in Tokyo, it’s something he relishes and does very well. • Andy Summers’ “A Series of Glances” is currently on view at the Leica Gallery in Tokyo and Kyoto through July 7. For more information, visit leica-camera.com/en-int/event/leica-gallery-tokyo/andy-summers.

May 21, 2024

Niigata 2024 Redux: Is anime from beyond Japan still 'anime?' Japan Times column

Niigata film festival showcases cutting-edge overseas talent

Less than a week after octogenarian Hayao Miyazaki scored his second Academy Award, another 80-something anime legend, “Gundam” creator Yoshiyuki Tomino, greeted a packed auditorium at the second annual Niigata International Animation Film Festival (NIAFF). Striding onstage in a funky black-and-white jacket, billowing slacks and a baseball cap, Tomino urged the artists in the audience to surpass his longtime rival, who he said had raised the artistic bar for the medium — “Let’s beat Miyazaki!”

Gundam creator Yoshiyuki Tomino and designer Yutaka Izubuchi open NIAFF 2024

Gundam creator Yoshiyuki Tomino and designer Yutaka Izubuchi open NIAFF 2024 Tomino’s rousing ebullience kicked off this year’s six-day NIAFF in Niigata, a mid-sized city two hours north of Tokyo by train. Despite brisk winds and spurts of snow, the city’s welcome felt even warmer this year, with local restaurants offering specials highlighted in the program guide and a cosplay parade snaking through the central shopping district.

NIAFF is devoted to feature-length animation over animated shorts, making it the largest festival of its kind in Asia. The 2024 edition showcased over 65 films, nearly 20 more than last year, from countries as far-flung as Latvia, Israel and Ireland, with 12 films from 11 countries in competition. Entries surged 250% over 2023, with 40% coming from Europe, and rising numbers from Asia and the Middle East — the latter being the next major growth market for anime and Japanese popular culture.

But Tomino’s presence and his call to eclipse Miyazaki underlined another reality in the domestic anime business: Many of its luminaries are aging into retirement. As NIAFF’s program revealed, it may be anime-inspired artists from overseas who are now at the cutting edge of the art form.

Two-dimensional techniques and stylizations, the crowning achievement of Japan’s animation legacy (even when enhanced by computer-generated visuals), dominated this year’s lineup. The stories were psychologically rich and emotionally dark — another hallmark of anime compared to the more conventionally moralistic and uplifting titles from American stalwarts such as Disney and Pixar. Artists from around the world raised on anime are now creating their homegrown versions of it.

Colombian director Diego Felipe Guzman, 39 — whose dystopian, Kafkaesque odyssey, “The Other Shape,” draws its color palette, misshapen faces and rubbery physiques from Masaaki Yuasa (“Inu-Oh”) and the late Satoshi Kon (the robot from “Paprika” has a cameo) — tells me that the innovations of Japan’s anime artists are what first drove him to make animation. He fell in love with Miyazaki’s work as a child; as an adult, Yuasa, Kon and “Akira” creator Katsuhiro Otomo kept him going. “For me, the lives of these giants of Japanese animation are an inspiration that reaffirms my decision to become an animator, despite all the obstacles.”

Joel Vaudreuil, director of this year’s grand prix-winning “When Adam Changes,” grew up in a small town in suburban Quebec, where local television networks broadcast anime series licensed from Fuji TV, including the whimsical “Demetan the Frog.” Vaudreuil, also an illustrator and writer, is particularly attracted to what he calls “the looseness and freedom of storytelling” in Japan’s hand-drawn animated works. In some of the big-budget American CGI productions, he says, “the editing is too tight. It looks like they’re trying to mask a lack of ideas.”

Joel Vaudreuil, director of When Adam Changes

Joel Vaudreuil, director of When Adam Changes Vaudreuil has presented his film at festivals in Europe and North America, but he says the intimacy of NIAFF affords unique opportunities. “(In Niigata), it’s still possible to encounter masters of animation up close. They’re so great that you expect them to magically glow, but they’re actually so accessible.”

Like most film festivals, NIAFF offers a surfeit of riches that pose head-spinning choices. Inevitably, screenings and talks overlap in the schedule. And seeing more than three films a day can induce cinematic vertigo in the most ardent attendee.

The opportunity to meet anime creators and producers far from their Tokyo studios and offices is one of NIAFF’s biggest attractions. Away from whiteboards, deadlines and back-to-back meetings, and suddenly plunked into a slower-paced city, participants from Japan and around the world are at ease to reflect on what they do and why.

Over a casual breakfast, I learned from Studio Chizu founder Yuichiro Saito, one of this year’s three competition judges, that director Mamoru Hosoda (“Belle,” “Summer Wars”) is developing his most ambitious project yet: a film that will take up Tomino’s challenge and may be Hosoda’s magnum opus.

Hosoda is one of many artists who formerly worked under Miyazaki but embarked on their own after creative disagreements. Another is Sunao Katabuchi (“In This Corner of the World”), who spent an afternoon explaining to me the dense research and revolutionary goals behind his forthcoming epic, “The Mourning Children,” a project seven years in the making.

The film is set in Kyoto in the Heian Period (794-1185), and legendary “Pillow Book” author Sei Shonagon is one of its main characters. Katabuchi will use the art of animation to expose the realities of the age: the unhygienic environment and practices of its people, but also their intuitive wisdom when facing down frequent plagues and natural disasters.

Echoing Japan’s more recent encounters with the pandemic and the calamities of 3/11, Katabuchi’s “Mourning Children” aims to perform an even more ambitious modern task: excavate the female perspective from male-dominated historical narratives imposed upon the Heian Period by scholars of the Meiji Era (1868-1912).

Is it a feminist retelling of ancient Japanese history? “Yes, you could say that,” he says.

Director Sunao Katabuchi at NIAFF 2024 (Matt Schley)

A retrospective of works by the late Isao Takahata, Katabuchi’s hero and Miyazaki’s longtime artistic partner, grounded NIAFF in the roots of ancient anime history. The screening of his 1982 classic, “Gauche the Cellist,” was attended by Takahata’s wife and eldest son, who movingly noted that the film was a family favorite because it focused on the beauty of music.

Nora Twomey, an Irish animator, co-founder of studio Cartoon Saloon (“Wolfwalkers,” “The Secret of Kells”) and a jury member at NIAFF, came away from this year’s festival deeply impressed by its growth and scope. “I only hope it doesn’t lose its informal vibe,” she tells me, “where everyone mixes together and conversation flows.”

Niigata 2024 Redux: Is anime from beyond Japan still 'anime?'

Niigata film festival showcases cutting-edge overseas talent

Less than a week after octogenarian Hayao Miyazaki scored his second Academy Award, another 80-something anime legend, “Gundam” creator Yoshiyuki Tomino, greeted a packed auditorium at the second annual Niigata International Animation Film Festival (NIAFF). Striding onstage in a funky black-and-white jacket, billowing slacks and a baseball cap, Tomino urged the artists in the audience to surpass his longtime rival, who he said had raised the artistic bar for the medium — “Let’s beat Miyazaki!”

Gundam creator Yoshiyuki Tomino and designer Yutaka Izubuchi open NIAFF 2024

Gundam creator Yoshiyuki Tomino and designer Yutaka Izubuchi open NIAFF 2024 Tomino’s rousing ebullience kicked off this year’s six-day NIAFF in Niigata, a mid-sized city two hours north of Tokyo by train. Despite brisk winds and spurts of snow, the city’s welcome felt even warmer this year, with local restaurants offering specials highlighted in the program guide and a cosplay parade snaking through the central shopping district.

NIAFF is devoted to feature-length animation over animated shorts, making it the largest festival of its kind in Asia. The 2024 edition showcased over 65 films, nearly 20 more than last year, from countries as far-flung as Latvia, Israel and Ireland, with 12 films from 11 countries in competition. Entries surged 250% over 2023, with 40% coming from Europe, and rising numbers from Asia and the Middle East — the latter being the next major growth market for anime and Japanese popular culture.

But Tomino’s presence and his call to eclipse Miyazaki underlined another reality in the domestic anime business: Many of its luminaries are aging into retirement. As NIAFF’s program revealed, it may be anime-inspired artists from overseas who are now at the cutting edge of the art form.

Two-dimensional techniques and stylizations, the crowning achievement of Japan’s animation legacy (even when enhanced by computer-generated visuals), dominated this year’s lineup. The stories were psychologically rich and emotionally dark — another hallmark of anime compared to the more conventionally moralistic and uplifting titles from American stalwarts such as Disney and Pixar. Artists from around the world raised on anime are now creating their homegrown versions of it.

Colombian director Diego Felipe Guzman, 39 — whose dystopian, Kafkaesque odyssey, “The Other Shape,” draws its color palette, misshapen faces and rubbery physiques from Masaaki Yuasa (“Inu-Oh”) and the late Satoshi Kon (the robot from “Paprika” has a cameo) — tells me that the innovations of Japan’s anime artists are what first drove him to make animation. He fell in love with Miyazaki’s work as a child; as an adult, Yuasa, Kon and “Akira” creator Katsuhiro Otomo kept him going. “For me, the lives of these giants of Japanese animation are an inspiration that reaffirms my decision to become an animator, despite all the obstacles.”

Joel Vaudreuil, director of this year’s grand prix-winning “When Adam Changes,” grew up in a small town in suburban Quebec, where local television networks broadcast anime series licensed from Fuji TV, including the whimsical “Demetan the Frog.” Vaudreuil, also an illustrator and writer, is particularly attracted to what he calls “the looseness and freedom of storytelling” in Japan’s hand-drawn animated works. In some of the big-budget American CGI productions, he says, “the editing is too tight. It looks like they’re trying to mask a lack of ideas.”

Joel Vaudreuil, director of When Adam Changes

Joel Vaudreuil, director of When Adam Changes Vaudreuil has presented his film at festivals in Europe and North America, but he says the intimacy of NIAFF affords unique opportunities. “(In Niigata), it’s still possible to encounter masters of animation up close. They’re so great that you expect them to magically glow, but they’re actually so accessible.”

Like most film festivals, NIAFF offers a surfeit of riches that pose head-spinning choices. Inevitably, screenings and talks overlap in the schedule. And seeing more than three films a day can induce cinematic vertigo in the most ardent attendee.

The opportunity to meet anime creators and producers far from their Tokyo studios and offices is one of NIAFF’s biggest attractions. Away from whiteboards, deadlines and back-to-back meetings, and suddenly plunked into a slower-paced city, participants from Japan and around the world are at ease to reflect on what they do and why.

Over a casual breakfast, I learned from Studio Chizu founder Yuichiro Saito, one of this year’s three competition judges, that director Mamoru Hosoda (“Belle,” “Summer Wars”) is developing his most ambitious project yet: a film that will take up Tomino’s challenge and may be Hosoda’s magnum opus.

Hosoda is one of many artists who formerly worked under Miyazaki but embarked on their own after creative disagreements. Another is Sunao Katabuchi (“In This Corner of the World”), who spent an afternoon explaining to me the dense research and revolutionary goals behind his forthcoming epic, “The Mourning Children,” a project seven years in the making.

The film is set in Kyoto in the Heian Period (794-1185), and legendary “Pillow Book” author Sei Shonagon is one of its main characters. Katabuchi will use the art of animation to expose the realities of the age: the unhygienic environment and practices of its people, but also their intuitive wisdom when facing down frequent plagues and natural disasters.

Echoing Japan’s more recent encounters with the pandemic and the calamities of 3/11, Katabuchi’s “Mourning Children” aims to perform an even more ambitious modern task: excavate the female perspective from male-dominated historical narratives imposed upon the Heian Period by scholars of the Meiji Era (1868-1912).

Is it a feminist retelling of ancient Japanese history? “Yes, you could say that,” he says.

Director Sunao Katabuchi at NIAFF 2024 (Matt Schley)

A retrospective of works by the late Isao Takahata, Katabuchi’s hero and Miyazaki’s longtime artistic partner, grounded NIAFF in the roots of ancient anime history. The screening of his 1982 classic, “Gauche the Cellist,” was attended by Takahata’s wife and eldest son, who movingly noted that the film was a family favorite because it focused on the beauty of music.

Nora Twomey, an Irish animator, co-founder of studio Cartoon Saloon (“Wolfwalkers,” “The Secret of Kells”) and a jury member at NIAFF, came away from this year’s festival deeply impressed by its growth and scope. “I only hope it doesn’t lose its informal vibe,” she tells me, “where everyone mixes together and conversation flows.”

April 2, 2024

BBC interview on Hayao Miyazaki's second Oscar

I first interviewed Hayao Miyazaki for Japanamerica in the early aughts. I was very fortunate. It was the usual story--a friend of a friend of a friend, and so on. He was a bit tight-lipped at first but relaxed and opened up when he realized that I was no otaku.

Later I was invited to interview him live onstage at UC Berkeley in California (video here), and we've had a few informal chats since.

When he was awarded a second Oscar this year (third if you count his 2014 honorary statuette), I gave interviews to the BBC, CNN and The Guardian, in addition to a couple of online Japanese media.

The business has undergone a revolution since our first meeting for Japanamerica. File-sharing and streaming media have made Japanese pop culture in general and anime in particular a content goldmine. The reputation of Miyazaki's Studio Ghibli has grown in prominence over the past 20 years, partly owing to its rich and unparalleled catalog of quality content, but also because of licensing deals signed by longtime producer/marketing maestro Toshio Suzuki for merchandise and global streaming platforms (Netflix, Max)--both revenue streams Miyazaki once told me he'd never deign to tap.

It's also worth noting that Miyazaki and Studio Ghibli set themselves apart from the rest of the anime industry in Japan. Miyazaki doesn't even use the word "anime" for his work, preferring "feature-length animated films," with the emphasis on movies, not episodic TV series or manga adaptations. Miyazaki himself openly disdains otaku fanboy culture and thinks most anime from Japan is cheap and puerile commercial drivel.

Outside of Japan, Miyazaki & Studio Ghibli = Anime. But at home, they want nothing to do with it.