Roland Kelts's Blog, page 5

September 16, 2023

Korea's competitive edge: On the 2023 Bucheon International Fantastic Film Festival (BiFan) for The Japan Times

Thirty minutes into “Iron Mask,” the debut feature from Korean writer-director Kim Sung Hwan, its kendo-crazed antihero, Jae-woo (Joo Jong-hyuk), stares trancelike through shadows at an offscreen character, his eyes unblinking. Under fire from his dojo for excessive violence and foul play, Jae-woo’s terse line of self-defense is chilling: “We’re in competition here.”

Thirty minutes into “Iron Mask,” the debut feature from Korean writer-director Kim Sung Hwan, its kendo-crazed antihero, Jae-woo (Joo Jong-hyuk), stares trancelike through shadows at an offscreen character, his eyes unblinking. Under fire from his dojo for excessive violence and foul play, Jae-woo’s terse line of self-defense is chilling: “We’re in competition here.”That sentence gave me pause during the film’s premiere this summer at the Bucheon International Fantastic Film Festival (BiFan) in South Korea, where “Iron Mask” took one of the two top awards. A vision of life as constant competition propels the most riveting of South Korea’s global cinematic sensations, from the Oscar-winning “Parasite” to hit Netflix series “Squid Game” and “D.P.” Characters on the verge of failure are tempted by Machiavellian schemes to survive in a society that respects only winners, and demands of its members brute desperation, fortitude and guile.

By comparison, many of the contemporary Japanese films and series I’ve recently seen — including those featured at this year’s BiFan, where Japanese genre works were spotlighted — feel listless and adrift, self-conscious portraits of Japan filtered through a soft-focus, navel-gazing nostalgia.

This is not always unpleasant. “Midnight Diner” has its charms, “Drive My Car” its moments of quiet beauty. And last year’s exquisitely patient “Zen Diary” plays like a tone poem. But the contrast between today’s South Korean and Japanese stories is stark: The former feel urgent, the latter calmly self-indulgent.

"Iron Mask" director Kim Sung Hwan According to “Iron Mask” director Kim, this distinction reflects a South Korea that has supplanted Japan as the tradition-bound Asian society most conflicted by its new identity as a capitalist pressure cooker. “In the 20th century, overcoming competition and getting into the University of Tokyo was a very big deal for Japanese people,” he says. “Japan used to compete with the whole world. They worked so hard and were super competitive in order to survive and secure their jobs. I guess South Korea today is showing similar behavior.”

"Iron Mask" director Kim Sung Hwan According to “Iron Mask” director Kim, this distinction reflects a South Korea that has supplanted Japan as the tradition-bound Asian society most conflicted by its new identity as a capitalist pressure cooker. “In the 20th century, overcoming competition and getting into the University of Tokyo was a very big deal for Japanese people,” he says. “Japan used to compete with the whole world. They worked so hard and were super competitive in order to survive and secure their jobs. I guess South Korea today is showing similar behavior.”Launched 27 years ago, BiFan is Asia’s largest genre film festival, highlighting works that take their cue from the pioneering 20th-century French director Georges Méliès (“A Trip to the Moon”), who argued that films should convey fantasy rather than reality to make our dreams believable.

Japanese screenings at BiFan included “Life of Mariko in Kabukicho,” co-directed by Eiji Uchida and Shinzo Katayama. Set in Tokyo’s red light district, the film features a host of cliched scenes and characters that reinforce overused stereotypes: a flirtatious male host, a homey, soft-lit bar with chummy regulars, a seedy serial killer, an eccentric who thinks he’s a ninja, clueless foreign cops (the FBI in Japan?) and, yes, extraterrestrials.

As you might guess, the story sprawls and spins off too many threads to cohere. More damningly, it can’t seem to commit to being either a lighthearted ensemble farce or a feminist detective thriller, and it doesn’t have the confidence to alternate genres for meaningful effect.

In "Life of Mariko in Kabukicho," the FBI shows up in Kabukicho

In "Life of Mariko in Kabukicho," the FBI shows up in Kabukicho BiFan’s closing film, “Sana,” suffers a similar lack of conviction. The latest from “Ju-on: The Grudge” franchise director Takashi Shimizu, “Sana” ended the festival with a whimper, wasting its potentially terrifying premise on a real-life J-pop boy band cast (Generations) with questionable acting skills. The ostensible target of throwaway “OK, Boomer” jokes, a 50-something private investigator (Makita Sports) who is also the film’s most compelling character, and the script’s obsession with 1980s tech in the form of a reverse-played audio cassette tape reveal its real concern: nostalgia for a more exciting era in Japan when the stakes were higher, pop music more magical and media formats reliably physical.

And then there’s “Single8,” Kazuya Konaka’s affectionately retro account of Japanese high schoolers in the late 1970s who form an unlikely crew to produce a “Star Wars”-inspired 8-mm short film about an alien encounter. The world they inhabit is strictly analog, and the real hero of their story is an icon of Japan’s electronics-manufacturing heyday: Fujifilm’s long-discontinued Single-8 film format. The title of the students’ short film? “Time Reverse.”

Now take South Korean director Kim Su-in’s taut and relentlessly dark “Toxic Parents,” whose teen protagonist is glued to her smartphone, exchanging text messages with her naively earnest male homeroom teacher while an idol-wannabe frenemy tests her vulnerabilities and her monstrous mom drives her to suicide. Woah.

While Japan’s “Sana” and “Single-8” look back on school-age shenanigans as the source of their loosely-strung narratives, South Korea’s “Toxic Parents” penetrates a high school in the here and now that is hardcore: a locus for outrageous expectations, bullying and necessarily repressed trauma.

"Toxic Parents": a monstrous mom in the here and now “(South Korean films) today convey their subjects well and get a more universal response than Japanese films,” says BiFan program director Ellen Kim. “They address the class system and capitalism and the government and American imperialistic interference without any suppression. But the Japanese industry is very self-satisfactory. Big companies control all the processes of production, and they are inflexible.” Japan’s tight corporate grip on filmmaking, she adds, turns talented Japanese actors into cogs of the gig economy: skilled creatives hampered by limited time and too many side jobs to focus on craft. “When South Korean actors have a film contract, they don’t do TV. But Japanese actors are treated like salaried workers finishing a product for release. They don’t have time to make art.” Harvard professor and East Asian film specialist Alexander Zahlten agrees that the scope and reach of Japanese films are truncated by the industry’s dependence on corporate money. However, he points out that the current system once saved the Japanese film market from total collapse. “(It) allowed the Japanese film industry to not only survive but return to a position of strength over the past three decades. The early 1990s were a time when some could envision Japanese film shrinking away almost completely. But by the 2010s, the market share of Japanese films once again reached almost 70%.”

"Toxic Parents": a monstrous mom in the here and now “(South Korean films) today convey their subjects well and get a more universal response than Japanese films,” says BiFan program director Ellen Kim. “They address the class system and capitalism and the government and American imperialistic interference without any suppression. But the Japanese industry is very self-satisfactory. Big companies control all the processes of production, and they are inflexible.” Japan’s tight corporate grip on filmmaking, she adds, turns talented Japanese actors into cogs of the gig economy: skilled creatives hampered by limited time and too many side jobs to focus on craft. “When South Korean actors have a film contract, they don’t do TV. But Japanese actors are treated like salaried workers finishing a product for release. They don’t have time to make art.” Harvard professor and East Asian film specialist Alexander Zahlten agrees that the scope and reach of Japanese films are truncated by the industry’s dependence on corporate money. However, he points out that the current system once saved the Japanese film market from total collapse. “(It) allowed the Japanese film industry to not only survive but return to a position of strength over the past three decades. The early 1990s were a time when some could envision Japanese film shrinking away almost completely. But by the 2010s, the market share of Japanese films once again reached almost 70%.”Over 11 days, BiFan 2023 hardly lacked in Japanese VIPs. Directors Uchida, Katayama, Konaka and Shimizu appeared alongside manga god Osamu Tezuka’s filmmaker son, Makoto Tezuka (“Tezuka’s Barbara”), Hollywood horror darling Ari Aster (“Midsommar”), veteran South Korean star Choi Min-sik (“Oldboy”), and the producers and lead actor from “D.P.,” which received this year’s Series Film Award. A festival record of 262 films from 51 countries were screened before 67,274 attendees, up 18.2% since 2022.

Director Makoto Tezuka, son of manga-anime pioneer Osamu, was one of many Japanese VIPs celebrated at BiFan

Director Makoto Tezuka, son of manga-anime pioneer Osamu, was one of many Japanese VIPs celebrated at BiFan But to me, the finest Japanese entry screened last month at BiFan was “Millennium Actress,” an anime feature directed by the late Satoshi Kon and released in 2001. Through its portrait of an aging and reclusive movie star (modeled on actresses Setsuko Hara and Hideko Takamine), the film spans centuries, weaving art, history, war and romantic love into an epic homage to master directors Akira Kurosawa and Yasujiro Ozu — icons of an era when Japan still competed with the whole world.

Time reverse, indeed.

August 23, 2023

Second interview for the History Channel on WWII & the M-Fund

2023

2023My latest interview for HISTORY Channel airing this month pursues my work on a story I started researching and writing about 20 years ago: the fate of billions of dollars (at least) worth of treasure plundered from Asia by the Japanese military in World War II, much of it buried in an underground network of tunnels and caves in the Philippines.

The loot was discovered forcibly by the Americans (i.e., GHQ), kept off the books, and deposited in bank accounts across the world--known primarily as the "M-Fund" (M-Shikin in Japanese). How was that money used? You can probably count the ways, but don't overlook the Marcos regime. Last time the producers cast me as a cafe-haunting journo. This time I'm playing an author/prof in a gulag. Here's the first story I ever wrote on the conspiracy, published in The Japan Times and based on my work with the late authors Sterling and Peggy Seagraves and their book GOLD WARRIORS:"Believe it ... or not"Intro: "Japan's vast hoard of war booty known as Yamashita's Gold was long thought to still be buried in caves in the Philippines. But in their book 'Gold Warriors,' Sterling and Peggy Seagraves sensationally claim that the treasure trove was secretly recovered -- and continues to oil the wheels of politics in Japan and beyond. As Roland Kelts discovered through interviews with the authors, it is a tale as disturbing as they insist it is well-founded."

2020

2020 • My interview with late authors Sterling and Peggy Seagraves.

• Some of my research materials.

• Overview of background from the Free Library.

• JP Wiki page on M-Shikin.

Second interview for the History Channel (now called HISTORY) on WWII & the M-Fund

2023My latest interview for HISTORY Channel airing this month pursues my work on a story I started researching and writing about 20 years ago: the fate of billions of dollars (at least) worth of treasure plundered from Asia by the Japanese military in World War II, much of it buried in an underground network of tunnels and caves in the Philippines. The loot was discovered forcibly by the Americans (i.e., GHQ), kept off the books, and deposited in bank accounts across the world--known primarily as the "M-Fund" (M-Shikin in Japanese). How was that money used? You can probably count the ways, but don't overlook the Marcos regime. Last time the producers cast me as a cafe-haunting journo. This time I'm playing an author/prof in a gulag. Here's the first story I ever wrote on the conspiracy, published in The Japan Times and based on my work with the late authors Sterling and Peggy Seagraves and their book GOLD WARRIORS:"Believe it ... or not"

2023My latest interview for HISTORY Channel airing this month pursues my work on a story I started researching and writing about 20 years ago: the fate of billions of dollars (at least) worth of treasure plundered from Asia by the Japanese military in World War II, much of it buried in an underground network of tunnels and caves in the Philippines. The loot was discovered forcibly by the Americans (i.e., GHQ), kept off the books, and deposited in bank accounts across the world--known primarily as the "M-Fund" (M-Shikin in Japanese). How was that money used? You can probably count the ways, but don't overlook the Marcos regime. Last time the producers cast me as a cafe-haunting journo. This time I'm playing an author/prof in a gulag. Here's the first story I ever wrote on the conspiracy, published in The Japan Times and based on my work with the late authors Sterling and Peggy Seagraves and their book GOLD WARRIORS:"Believe it ... or not"Intro: "Japan's vast hoard of war booty known as Yamashita's Gold was long thought to still be buried in caves in the Philippines. But in their book 'Gold Warriors,' Sterling and Peggy Seagraves sensationally claim that the treasure trove was secretly recovered -- and continues to oil the wheels of politics in Japan and beyond. As Roland Kelts discovered through interviews with the authors, it is a tale as disturbing as they insist it is well-founded."

2020

2020 • My interview with late authors Sterling and Peggy Seagraves.

• Some of my research materials.

• Overview of background from the Free Library.

• JP Wiki page on M-Shikin.

June 28, 2023

Letters from Tokyo by Roland Kelts, February - May : "What a Long Strange Spring It’s Been" for The Japan Society of Boston

Letters from Tokyo by Roland Kelts, February - May : What a Long Strange Spring It’s Been

We swallowed an entire season in the latest of my "Letters from Tokyo" series for The Japan Society of Boston, partly because I was away from Tokyo for huge chunks of it. This spring Japan opened its borders and the tourists rushed into Tokyo and Kyoto, PM Kishida survived an attempted assault via pipe (smoke?) bomb--and while Covid eased its grip, roller-coaster climate changes have swung many of us (i.e, me) in and out of summer colds. Let's look back before we fast-forward too far.

The February night I returned to Tokyo from New York felt like spring had landed ahead of me. I shed my jacket in the unusually long taxi line outside Haneda, watched two teenage boys order an Uber and promptly copied them, stepped over the ropes, skipped the line, and settled after five minutes into the backseat of my driver’s minivan, rolling down the windows on both sides.

The weather during my two-week stay in New York had been alternately mild and frigid, but the air was so dry that Tokyo’s subtropical humidity embraced me like a mitten. Body parts that shivered at departure were sweating on arrival.

This couldn’t be February, I thought. But my watch said it was and as soon as I got home I slid open more windows and sat on the balcony, watching the red aircraft warning lights on Shinjuku skyscrapers blink against sleep.

(photo by Marie Mutsuki Mockett)

(photo by Marie Mutsuki Mockett)Spring is a transitional season and not my favorite (I'm an autumn guy, soft color and fading light), and this one has felt especially long because I flew to the US twice, to New York and Los Angeles, to be interviewed for doc series on Netflix, the History Channel and PBS. In between I spent a week in Niigata to write about a new international film festival. On the Joetsu Shinkansen we rolled north from the whites of Kanto's Somei Yoshino through the gray snows of Gunma to the Sea of Japan blues and back again--a reminder that Honshu hosts several seasons at once.

The cherry blossoms bloomed earlier than ever. They were out before I flew to LA and after I flew back, prompting relentless sakura pics on social media taken from every angle at every hour through whatever filter fit the whim. Hanami revelers carpeted Yoyogi Park, and the blossoms above them were tenacious, clinging to limbs through breezy rains as if they, too, needed a post-Covid coming-out and meant to milk every minute of it.

But flowers were not the only blossoms in town. For the first time in more than two years, overseas tourists sprouted from every curb and corner, brandishing smartphones to keep the unknown at bay. In March, newspapers recorded Japan’s highest “post-Covid” surge in visitors, rising to over 65% of 2019’s peak, though quite when the virus had gone passé and postal remains unclear. Covid was still happening in March, at least by all official measures, and in Tokyo we wore masks and sanitized and tried to follow the government’s soft-core 2020 advisory to avoid the “Three Cs”—closed spaces, crowded places and close-contact settings.

One of the clerks at one of my local Lawson convenience stores—there are two roughly four-minutes’ walk apart, but only one has the tall, paunchy, garrulous clerk—complimented me on my mask-wearing as I purchased a tub of yogurt. I’d been in LA for just a couple of weeks and at first I thought he’d forgotten who I was and mistook me for a tourist. Then he added that masks were so troublesome, weren’t they? And they made it hard to breathe, didn’t they? And it was very good of us to continue wearing and bearing them, wasn’t it? And I nodded, relieved.

Relief overwhelms me when I return to Japan. It wasn’t always so. For years “returning” meant going back to New York, arriving home from my overseas life. If I had a window seat and caught the jewel of Manhattan’s skyline upon descent, I felt a familiar surge in my chest, a tightening of selfhood and resolve: My home language, my sense of space and energy revived, my food smells, street-stench and signage. Ah.

Somewhere along the way, and at some point in time (do we ever know when, exactly, things really change?) overseas became over there, the destination when my flights soared Eastward, to North America.

That’s the journey I now need to gird for, rethinking my behavior (am I speaking too quietly, apologizing too often, bowing instead of shaking your hand?), diet (what to do with these gargantuan, overstuffed sandwiches?), gait (strut and sway through those wide spaces, don’t stiffen like a pencil-geek), and expectations—this last being the hardest adjustment to make. From vending machines to trains, planes, escalators and autos, most things work most of the time in Japan. When they don’t, someone apologizes profusely.

Deep breaths, count to 10, 20, 57. I learn and relearn to curb my expectations in the US so I won’t grow exasperated, or get shot. (Those signs at Nordstrom saying no guns allowed! Necessary, I guess, but, oh.) A phrase I was raised with, “the far east,” so alien and exotic, now points to a land east of where I live, across the Pacific, a country where I was raised but no longer reside.

Tokyo has seen its own share of sadness and ailments this spring. March marked the 12th anniversary of the Tohoku triple disasters of earthquake, tsunami and meltdown. Each year the horror is revisited but never quite reckoned with, and the tally of the dead and the missing, now at 22,215, ticks up silently. Sparse anti-nuclear demonstrations were punctuated on March 28 by the death of pioneering composer/musician Ryuichi Sakamoto, also a committed anti-nuclear and environmental activist. And less than a year after the shooting murder of former Prime Minister Shinzo Abe, a 24 year-old man tossed a pipe bomb at sitting PM Fumio Kishida during a campaign event in Wakayama, missing his target by barely 10 feet.

One week in April, a sudden spike in the mercury and humidity caused a record number of heat stroke cases at Tokyo clinics. The following week got so chilly that a relatively new diagnosis, “spring fatigue,” was ascribed to patients complaining of muscle aches, sleeplessness, appetite loss and, well, the overall fatigue stemming from drastic climate swings. (One news show demonstrated the proper way of folding a few sweaters hastily retrieved from winter storage amid this spring’s temperamental temperatures.)

Not to be outdone, May brought us gogatsu-byou, or “the May blues,” another kind of seasonal blight brought on by the end of the Golden Week spring holidays (on May 8 this year) and feeling overwhelmed by work, school, family or other obligations, or just the end of spring and start of summer, or just the ongoing month of May itself, which ambles for 31 lengthening days.

Therapy doesn’t have the cure-all prestige in Japan that it carries for many in the US, so these afflictions are blamed on the autonomic nervous system, which regulates everything our bodies do that we don’t think about. Doctors prescribe rest, changes in diet, exercise, sometimes medication.

But nerves of every kind all across Tokyo were shaken by a cause for which there is no cure. A little after 4 a.m. on May 11 (another 11!), a 5.4-magnitude earthquake struck Chiba, slightly east of Tokyo. Smartphone emergency alerts sounded across the city, waking some 30 million or more with an urgent reminder of our precarity in this most functional metropolis. It’s mere coincidence, of course, but as I write I’m already half-packed for my next flight to New York.

June 21, 2023

My take on Tokyo's surging startup scene and Japan's boom for Rest of World

A couple of weeks after I wrote this story for Rest of World, the Tokyo Stock Exchange hit a 33-year high. Credit my editor.

Japan’s sleepy tech scene is ready for a comeback After decades of slumber, the country that brought us bullet trains and Nintendo has mustered some momentum.

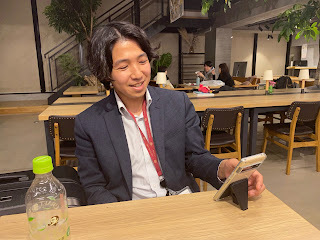

Sho Hayashi might be a walking cliche in San Francisco or Austin. The 33-year-old founder, with two successful startups and a string of degrees to his name, met me in a light-filled coworking space before flying overseas for a weekend of meetings.

But here in Japan, Hayashi is a new breed of revolutionary. A graduate of the elite University of Tokyo, his standard path would have been to settle into a lifetime job — perhaps as an international diplomat, or at a time-tested corporate empire like Mitsubishi. When he attended a massive startup conference in Singapore in 2010 and realized Japan didn’t have a single representative, he asked to become one and found a new calling: entrepreneurship.

“I realized that diplomats don’t create anything; they just negotiate based on what’s there,” Hayashi said. “I wanted to create. It changed my life.”

Japan is the third-richest nation in the world but has only managed to produce some 10 unicorns. (Compare that to over 600 unicorns in the U.S. and more than 300 in China.) Its tech startup scene been held back for years by siloed and intransigent corporate leaders and an aging, risk-averse populace whose fear of innovation turned a once-futuristic nation into a digital backwater.

Since the pandemic, more people like Hayashi have been straying from routine, and their choices are being validated by record amounts of funding flowing into tech startups, new city government initiatives that support fledgling entrepreneurs, and a spate of juicy tax breaks. Combined with the behavioral circuit-breaker of Covid-19, these initiatives may be seminal: Japan’s tech scene is, perhaps, finally beginning to free itself from decades of inertia.

“It’s a total mindset shift,” said Kenta Iwata, 28, a community manager at the cross-disciplinary project Shibuya QWS (pronounced “cues”). Launched in late 2019 by railways-to-real-estate giant Tokyu Group, QWS is a radical concept in Japan: a corporate-backed space connecting employees across major companies and institutions. QWS staff like Iwata help foster those connections and get people talking.

“Fifty years ago, Japan was number one in growth, so you could have a steady life doing one job,” he said. “But having one job means meeting people only from your own company. What we provide is serendipity, a place where like-minded employees might create a new company. QWS wouldn’t have existed even five years ago.”

The pandemic helped accelerate that shift, according to Hayashi. “It’s not unusual now for people to quit their jobs and join a startup,” he said. “During the pandemic, [people] began thinking about how they really want to work, starting side projects or taking two or more jobs, even mid-career. Things opened up.”

In the vast, open-air loft surrounding us, things are bustling. Young Japanese people chat and giggle as they pass, some taking seats to mingle at long blonde-wood tables. Smartphones chime and keyboards click as the savory aroma of Japanese curry wafts down from the communal kitchen on the second floor.

Japan’s tech startup scene has long been a victim of a kind of lukewarm comfort. Five years ago, I spoke to the late Asia scholar Ezra Vogel, author of the economic bubble-era bestseller Japan As Number One: Lessons for America. He told me that while his Chinese friends were bullish on their economy and overseas plans, his friends in Japan dreaded their bland prospects — yet they preferred to stay home. A job for life, however stultifying, was better than uncertainty. “Japan has become a very comfortable place to live,” Vogel surmised. “Maybe too comfortable.”

After 2018, funding and pragmatic, startup-friendly announcements began to mount. City government-financed initiatives, such as Shibuya Startup Support and CityTech Tokyo, have helped founders gain access to the local resources they need to launch companies. The Shibuya government has been particularly active, launching a startup visa to lure overseas entrepreneurs and forging partnerships with innovation consultants like Egg Forward.

A tweak to the government’s Pension Investment Fund incentives led to public money flowing to venture capital firms, which drove a record amount of funding into mostly tech startups in 2022. That was the same year investments in the U.S. and Europe dropped by 30% and 16% respectively. Coupled with tax breaks, including one for corporations seeking to acquire startups, these projects make Japan’s current surge feel more solid.

(Ambitious yet less-defined government initiatives — like the national Digital Agency and Prime Minister Fumio Kishida’s pledge to increase tech startups tenfold in five years — have been eyed with some skepticism by the industry.)

Chinese-born, U.S.-raised Yan Fan, who worked as a software engineer in Silicon Valley, moved to Japan six years ago and co-founded Code Chrysalis, a coding boot camp for mostly corporate clients. Code Chrysalis is aimed at filling Japan’s shortfall in engineers, something that has both slowed software development and forced Japan to import developer talent.

When she relocated, Fan had no delusions about Japan’s limited opportunities for entrepreneurial growth. “I told everyone to at least start their careers in the U.S. so they can learn how to fail,” she said. “There’s no tolerance for failure here.”

But recent developments have her feeling more sanguine. Mergers and acquisitions around tech have been increasing, she pointed out, and graduates from Japan’s top universities are embracing jobs at startups. It has become trendy to join Google, Netflix, and Facebook, even if those brands might mean little to their parents. Code Chrysalis now occupies an office in Tokyo’s tony Motoazabu district, and boasts a technical team that is 50% female and 9% non-binary.

“There’s a big generational thing happening in Japan,” said Fan. “But you have to find the right balance between old Japan and the new Japan emerging.”

Post pandemic, she said, there’s been an increase in demand from large corporations for generalized coding skills. “‘DX,’ ‘reskilling,’ ‘agile’ are all huge buzzwords … Every major Japanese company is exploring what they need to do and has the cash to do it.” The startup’s client list currently includes Nomura Research Institute, and the country’s first unicorn: e-commerce site Mercari.

Historically, foreign pressures, or gaiatsu, have forced change in Japan. These days, there is plenty of pressure coming from inside the country. The unmitigated spiral of its declining population has already resulted in a severe labor shortage. Estimates say that by 2050, Japan’s population will have dropped from around 125 million in 2023 to just 97 million. Then there’s the anemic state of Japan’s digital infrastructure, which was exposed during the pandemic’s peak with the slow and lackluster snail mail-based vaccine campaign and the requirement for reams of paperwork in order to enter the country.

Tomonori Iida describes that moment as a reckoning for Japan. He heads a program aimed at teaching older Japanese employees digital skills, partly run by Benesse Corporation — a name perhaps best-known outside Japan for its innovative, art-driven reinvention of Naoshima Island.

“I think Covid[-19] made us realize how vulnerable we were without digitization. A lot of things just stopped or stalled,” said Iida. “This was a wake-up call for us, forcing government and corporate leaders to spring into action.”

Japan’s tech scene finally has some momentum, an energy that feels palpable. But is it really on the verge of producing something new for the rest of the world?

According to international finance lawyer Yuki Shirato, who has also been an angel investor and served on the board of several startups, the biggest changes in Japan’s tech scene may take five to six years. That’s a lifetime in Silicon Valley, but a rapid clip in centuries-old Japan. “The language and mental barriers, the resistance to taking risks — that will take time to overcome,” he said.

Japanese tech startups will likely have different values and goals, he added, along with a greater focus on innovation in areas like fintech, biotech, and health care. There will also be a bigger push towards the development of more pragmatic, hardware-contingent products, such as smart devices.

Japan’s high quality of life is also not lost on local and foreign entrepreneurs — some of whom are questioning the wisdom of moving fast and breaking things in a world now breaking apart.

Shirato recounted the story of an American friend, a founder based in Tokyo, whose son recently suffered a life-threatening injury. In the U.S., he said, the cost of the son’s treatment would have exceeded one million dollars and bankrupted his friend’s company. “That’s just not part of our culture.”

Hayashi would agree. “It’s about priorities, I guess,” he told me, minutes before hailing an Uber for the airport. “If your only goal is to maximize financial gains, it’s probably wiser to work for higher wages abroad. But Japan is a place where society gives, and you can give something back.”

My take on Tokyo's surging startup scene and Japan's boom

A couple of weeks after I wrote this story for Rest of World, the Tokyo Stock Exchange hit a 33-year high. Credit my editor.

Japan’s sleepy tech scene is ready for a comeback After decades of slumber, the country that brought us bullet trains and Nintendo has mustered some momentum.

Sho Hayashi might be a walking cliche in San Francisco or Austin. The 33-year-old founder, with two successful startups and a string of degrees to his name, met me in a light-filled coworking space before flying overseas for a weekend of meetings.

But here in Japan, Hayashi is a new breed of revolutionary. A graduate of the elite University of Tokyo, his standard path would have been to settle into a lifetime job — perhaps as an international diplomat, or at a time-tested corporate empire like Mitsubishi. When he attended a massive startup conference in Singapore in 2010 and realized Japan didn’t have a single representative, he asked to become one and found a new calling: entrepreneurship.

“I realized that diplomats don’t create anything; they just negotiate based on what’s there,” Hayashi said. “I wanted to create. It changed my life.”

Japan is the third-richest nation in the world but has only managed to produce some 10 unicorns. (Compare that to over 600 unicorns in the U.S. and more than 300 in China.) Its tech startup scene been held back for years by siloed and intransigent corporate leaders and an aging, risk-averse populace whose fear of innovation turned a once-futuristic nation into a digital backwater.

Since the pandemic, more people like Hayashi have been straying from routine, and their choices are being validated by record amounts of funding flowing into tech startups, new city government initiatives that support fledgling entrepreneurs, and a spate of juicy tax breaks. Combined with the behavioral circuit-breaker of Covid-19, these initiatives may be seminal: Japan’s tech scene is, perhaps, finally beginning to free itself from decades of inertia.

“It’s a total mindset shift,” said Kenta Iwata, 28, a community manager at the cross-disciplinary project Shibuya QWS (pronounced “cues”). Launched in late 2019 by railways-to-real-estate giant Tokyu Group, QWS is a radical concept in Japan: a corporate-backed space connecting employees across major companies and institutions. QWS staff like Iwata help foster those connections and get people talking.

“Fifty years ago, Japan was number one in growth, so you could have a steady life doing one job,” he said. “But having one job means meeting people only from your own company. What we provide is serendipity, a place where like-minded employees might create a new company. QWS wouldn’t have existed even five years ago.”

The pandemic helped accelerate that shift, according to Hayashi. “It’s not unusual now for people to quit their jobs and join a startup,” he said. “During the pandemic, [people] began thinking about how they really want to work, starting side projects or taking two or more jobs, even mid-career. Things opened up.”

In the vast, open-air loft surrounding us, things are bustling. Young Japanese people chat and giggle as they pass, some taking seats to mingle at long blonde-wood tables. Smartphones chime and keyboards click as the savory aroma of Japanese curry wafts down from the communal kitchen on the second floor.

Japan’s tech startup scene has long been a victim of a kind of lukewarm comfort. Five years ago, I spoke to the late Asia scholar Ezra Vogel, author of the economic bubble-era bestseller Japan As Number One: Lessons for America. He told me that while his Chinese friends were bullish on their economy and overseas plans, his friends in Japan dreaded their bland prospects — yet they preferred to stay home. A job for life, however stultifying, was better than uncertainty. “Japan has become a very comfortable place to live,” Vogel surmised. “Maybe too comfortable.”

After 2018, funding and pragmatic, startup-friendly announcements began to mount. City government-financed initiatives, such as Shibuya Startup Support and CityTech Tokyo, have helped founders gain access to the local resources they need to launch companies. The Shibuya government has been particularly active, launching a startup visa to lure overseas entrepreneurs and forging partnerships with innovation consultants like Egg Forward.

A tweak to the government’s Pension Investment Fund incentives led to public money flowing to venture capital firms, which drove a record amount of funding into mostly tech startups in 2022. That was the same year investments in the U.S. and Europe dropped by 30% and 16% respectively. Coupled with tax breaks, including one for corporations seeking to acquire startups, these projects make Japan’s current surge feel more solid.

(Ambitious yet less-defined government initiatives — like the national Digital Agency and Prime Minister Fumio Kishida’s pledge to increase tech startups tenfold in five years — have been eyed with some skepticism by the industry.)

Chinese-born, U.S.-raised Yan Fan, who worked as a software engineer in Silicon Valley, moved to Japan six years ago and co-founded Code Chrysalis, a coding boot camp for mostly corporate clients. Code Chrysalis is aimed at filling Japan’s shortfall in engineers, something that has both slowed software development and forced Japan to import developer talent.

When she relocated, Fan had no delusions about Japan’s limited opportunities for entrepreneurial growth. “I told everyone to at least start their careers in the U.S. so they can learn how to fail,” she said. “There’s no tolerance for failure here.”

But recent developments have her feeling more sanguine. Mergers and acquisitions around tech have been increasing, she pointed out, and graduates from Japan’s top universities are embracing jobs at startups. It has become trendy to join Google, Netflix, and Facebook, even if those brands might mean little to their parents. Code Chrysalis now occupies an office in Tokyo’s tony Motoazabu district, and boasts a technical team that is 50% female and 9% non-binary.

“There’s a big generational thing happening in Japan,” said Fan. “But you have to find the right balance between old Japan and the new Japan emerging.”

Since the pandemic, she said, there’s been an increase in demand from large corporations for generalized coding skills. “‘DX,’ ‘reskilling,’ ‘agile’ are all huge buzzwords … Every major Japanese company is exploring what they need to do and has the cash to do it.” The startup’s client list currently includes Nomura Research Institute, and the country’s first unicorn: e-commerce site Mercari.

Historically, foreign pressures, or gaiatsu, have forced change in Japan. These days, there is plenty of pressure coming from inside the country. The unmitigated spiral of its declining population has already resulted in a severe labor shortage. Estimates say that by 2050, Japan’s population will have dropped from around 125 million in 2023 to just 97 million. Then there’s the anemic state of Japan’s digital infrastructure, which was exposed during the pandemic’s peak with the slow and lackluster snail mail-based vaccine campaign and the requirement for reams of paperwork in order to enter the country.

Tomonori Iida describes that moment as a reckoning for Japan. He heads a program aimed at teaching older Japanese employees digital skills, partly run by Benesse Corporation — a name perhaps best-known outside Japan for its innovative, art-driven reinvention of Naoshima Island.

“I think Covid[-19] made us realize how vulnerable we were without digitization. A lot of things just stopped or stalled,” said Iida. “This was a wake-up call for us, forcing government and corporate leaders to spring into action.”

Japan’s tech scene finally has some momentum, an energy that feels palpable. But is it really on the verge of producing something new for the rest of the world?

According to international finance lawyer Yuki Shirato, who has also been an angel investor and served on the board of several startups, the biggest changes in Japan’s tech scene may take five to six years. That’s a lifetime in Silicon Valley, but a rapid clip in centuries-old Japan. “The language and mental barriers, the resistance to taking risks — that will take time to overcome,” he said.

Japanese tech startups will likely have different values and goals, he added, along with a greater focus on innovation in areas like fintech, biotech, and health care. There will also be a bigger push towards the development of more pragmatic, hardware-contingent products, such as smart devices.

Japan’s high quality of life is also not lost on local and foreign entrepreneurs — some of whom are questioning the wisdom of moving fast and breaking things in a world now breaking apart.

Shirato recounted the story of an American friend, a founder based in Tokyo, whose son recently suffered a life-threatening injury. In the U.S., he said, the cost of the son’s treatment would have exceeded one million dollars and bankrupted his friend’s company. “That’s just not part of our culture.”

Hayashi would agree. “It’s about priorities, I guess,” he told me, minutes before hailing an Uber for the airport. “If your only goal is to maximize financial gains, it’s probably wiser to work for higher wages abroad. But Japan is a place where society gives, and you can give something back.”

June 8, 2023

DW interview on manga's explosive sales and Keidanren's money

Anime may be booming, but Japanese manga (comic book) sales are astronomical. I was interviewed about the explosive overseas sales of manga during the pandemic and the recent proposal by Keidanren, Japan's biggest business federation, to quadruple overseas manga sales over the next 10 years.

You can read Julian Ryall's full story here.

Excerpt: "'I was stunned when I saw the figures for 2020 and 2021, which showed that year-on-year manga sales in the US were up by 171%,' Kelts told DW. 'That's just an astonishing number, and the figures made it clear that the overall graphic novel market grew much faster than the standard market for books.'

There are key differences between the Japanese and US markets, however, with sales of print manga in North America driven in recent years by anime that consumers will have seen on television, including such famous titles as 'One Piece,' 'Attack on Titan,' and 'Spy Family,' Kelts highlighted. The situation is reversed in Japan, where series of print manga that are popular are made into anime.

According to Kelts, Japanese consumers have also been quicker to embrace online manga because North American homes are typically significantly larger than Japanese abodes, meaning they have more space to store large numbers of books.

Readers in Japan, on the other hand, used to treat manga as disposable and leave them on trains for other people to read. That no longer happens, as consumers now frequently read the latest instalment of their favorite manga on their mobile phones.

'Fifteen years ago, Japanese business leaders sneered at the idea that manga and anime could become an important export sector for Japan, but that generation has now retired and been replaced by people who 'get it' when it comes to manga,' Kelts said.

Keidanren chairman Masakazu Tokura is known to be a fan of anime and manga, and discussed the film adaptation of the basketball manga 'Slam Dunk' with South Korean President Yoon Suk-yeol during his recent visit to Tokyo.

'Tokura came of age during the 1970s and '80s, when manga were ubiquitous in Japan,’ Kelts pointed out. ‘In fact, domestic print sales peaked in the mid-'90s, so he and his cohorts have none of the prejudices against manga that their predecessors may have held.

'At present, Japan is the unchallenged world leader in anime and manga and Keidanren is right to get behind it as a driver of the economy.'"

AP interview on anime, Hollywood, "The Art of Blade Runner: Black Lotus"--and that new "One Piece" adaptation, out August 31

Belated thanks to Yuri Kageyama of the Associated Press for her story about Hollywood anime adaptations that grew out of my FCCJ event for the new Blade Runner: Black Lotus book. This article was published well before the live-action Saint Seiya movie (called Knights of the Zodiac, btw) dropped and disappeared, and word from the One Piece set ain't so great either. (Original mangaka Eichiro Oda apparently has a lot of notes.)

You can read Yuri's full article here. It was a particular honor for me to be featured alongside one of my former students, Nina Oiki, for whom I was happy to sign a book at the press club.

Excerpt: "The cross-pollination of Hollywood and Japan goes back for decades. References to Japan, such as the image of a geisha on a screen, are plentiful in the 1982 sci-fi movie “Blade Runner,” directed by Ridley Scott.

The film, in turn, influenced anime, including the “Blade Runner: Black Lotus” anime that first aired in 2021.

Japanese pop culture expert Roland Kelts says it’s a “stunning moment for anime,” in part due to streaming on platforms like Netflix, which has helped make entertainment borderless.

Live-action “One Piece,” expected later this year, comes on the heels of the global success of “Demon Slayer,” another manga that got its start in Shonen Jump and was adapted into a movie and an anime series that was picked up by Netflix.

In February, The Pokémon Company announced “Pokémon Concierge,” a stop-motion anime collaboration with Netflix. Pokémon is the world’s most valuable media franchise with estimated all-time sales of $100 billion, according to a 2021 Statista report. Followed by Hello Kitty, the two Japanese products outrank Western offerings like Mickey Mouse, Winnie the Pooh and Star Wars. Hollywood live-action adaptations of other popular Japanese products — from Makoto Shinkai's 2016 body-swap anime “Your Name” to the “Gundam” franchise of giant robots that started in 1979 — are also in progress.

Anime has a low production cost compared to live-action films, and computer-generated heroes don’t get sick or injured or make offensive remarks offscreen like real-life actors sometimes do, making it a marketable medium, said Kelts, author of “Japanamerica,” which documents Japanese pop culture's influence in the United States.

“They are stylized and stateless characters. What I mean by that is that anime characters travel globally very, very well,” Kelts said. “The human celebrities don’t always travel so well."

Established bestsellers offer the advantage of a built-in fanbase, but they also come with strict scrutiny. Some, like “Ghost in the Shell,” have been criticized for “whitewashing” the Asian original. The 1995 animated movie was made into a Hollywood live-action in 2017 amid complaints about casting white American actor Scarlett Johansson as the main character — though Asia largely stayed out of the debate."

AP interview on anime, Hollywood, "The Art of Blade Runner: Black Lotus"--and that new "One Piece" adaptation, out July 1

Belated thanks to Yuri Kageyama of the Associated Press for her story about Hollywood anime adaptations that grew out of my FCCJ event for the new Blade Runner: Black Lotus book. This article was published well before the live-action Saint Seiya movie (called Knights of the Zodiac, btw) dropped and disappeared, and word from the One Piece set ain't so great either. (Original mangaka Eichiro Oda apparently has a lot of notes.)

You can read Yuri's full article here. It was a particular honor for me to be featured alongside one of my former students, Nina Oiki, for whom I was happy to sign a book at the press club.

Excerpt: "The cross-pollination of Hollywood and Japan goes back for decades. References to Japan, such as the image of a geisha on a screen, are plentiful in the 1982 sci-fi movie “Blade Runner,” directed by Ridley Scott.

The film, in turn, influenced anime, including the “Blade Runner: Black Lotus” anime that first aired in 2021.

Japanese pop culture expert Roland Kelts says it’s a “stunning moment for anime,” in part due to streaming on platforms like Netflix, which has helped make entertainment borderless.

Live-action “One Piece,” expected later this year, comes on the heels of the global success of “Demon Slayer,” another manga that got its start in Shonen Jump and was adapted into a movie and an anime series that was picked up by Netflix.

In February, The Pokémon Company announced “Pokémon Concierge,” a stop-motion anime collaboration with Netflix. Pokémon is the world’s most valuable media franchise with estimated all-time sales of $100 billion, according to a 2021 Statista report. Followed by Hello Kitty, the two Japanese products outrank Western offerings like Mickey Mouse, Winnie the Pooh and Star Wars. Hollywood live-action adaptations of other popular Japanese products — from Makoto Shinkai's 2016 body-swap anime “Your Name” to the “Gundam” franchise of giant robots that started in 1979 — are also in progress.

Anime has a low production cost compared to live-action films, and computer-generated heroes don’t get sick or injured or make offensive remarks offscreen like real-life actors sometimes do, making it a marketable medium, said Kelts, author of “Japanamerica,” which documents Japanese pop culture's influence in the United States.

“They are stylized and stateless characters. What I mean by that is that anime characters travel globally very, very well,” Kelts said. “The human celebrities don’t always travel so well."

Established bestsellers offer the advantage of a built-in fanbase, but they also come with strict scrutiny. Some, like “Ghost in the Shell,” have been criticized for “whitewashing” the Asian original. The 1995 animated movie was made into a Hollywood live-action in 2017 amid complaints about casting white American actor Scarlett Johansson as the main character — though Asia largely stayed out of the debate."

May 11, 2023

Anime masters meet in Niigata: On the first annual Niigata International Animation Festival (NIAFFf) for The Japan Times

When Katsuhiro Otomo (Akira), Mamoru Oshii (Ghost in the Shell) and Shinichiro Watanabe (Cowboy Bebop) show up in the same small venue in the same small city on the Sea of Japan--magic happenstances. I was invited to attend the first annual Niigata International Animation Festival and I'm glad I went. My take below.

New Niigata film festival brings out the big names in anime Roland Kelts JAPAN TIMES column CULTURE SMASH

Roland Kelts JAPAN TIMES column CULTURE SMASHIt’s no secret that Japan loves animation. Despite being a marginalized medium elsewhere, animation in Japan regularly tops the domestic box office, earning billions of yen for films made without movie stars and on relatively low budgets. Of Japan’s 10 highest-grossing movies ever, seven are animated.

But there’s a hitch: six of those top seven titles are homegrown. Animation produced elsewhere, aside from the occasional old-school Disney blockbuster like “Frozen,” rarely gets seen in Japan, let alone embraced by moviegoers. Like short-grain white rice and unagi (freshwater eels), when it comes to animation, most Japanese prefer their own — and there’s plenty of it.

So when I got my invitation to the inaugural Niigata International Animation Film Festival (NIAFF) in the mail last month, I was confused. Was it a showcase of Japan-produced anime for an international audience? And instead of Niigata, did they mean to write Nagoya, where attendees could sample the wonders of animation genius Hayao Miyazaki at Ghibli Park, less than an hour from town? Or did they mean Nagano, with its tourist-ready snow monkeys and ski resorts?

In fact, the festival really was in Niigata, a mid-sized northern port city on the Sea of Japan, and its program was broadly international in scope, showcasing 50 films from 16 countries over six consecutive days, from March 17 to 22.

None of this was an accident, according to festival co-founder and program director Tadashi Sudo.

“Niigata is actually an ideal location,” he says. “In Tokyo and Osaka, film festivals are less prominent, but in Niigata, they attract attention. It’s only two hours from Tokyo and close to many Asian hub cities, and has been home to some major anime artists and staff.”

Tadashi Sudo

Tadashi SudoWhile Niigata may not be the first stop for tourists on anime pilgrimages, the city was the birthplace of both Hiroshi Okawa, founder of pioneering industry giant Toei Animation, and manga master Rumiko Takahashi (“Urusei Yatsura,” “Inuyasha”). Today it boasts an anime and manga museum and festival, several art and production schools, and a satellite studio for the renowned Tokyo-based animation company Production I.G.Sudo says NIAFF’s goal is not to promote Japanese intellectual property but to highlight global diversity in animation.“We want more countries and regions, more themes, and a wide range of genres and border-crossing art,” he says.

Feature-length films are also a hallmark of NIAFF, which is now the largest annual festival in Asia devoted to the long form (versus animated shorts). The 2023 lineup included entries spanning Brazil to the Netherlands to China in a dazzling variety of formats (CG, 2D, rotoscoping and stop-motion animation) that often rendered dark stories in culturally rooted environs.

Khamsa

KhamsaNot all of the overseas filmmakers invited to the festival made it to Niigata this year, but the dozen or so on hand responded enthusiastically. Japan’s reputation as a leader in animation commanded ample respect.

Algerian director Khaled Chiheb, visiting Japan for the first time, presented his and his native country’s first-ever full-length animated film, “Khamsa: The Well of Oblivion,” an eerie and poetic story about the retrieval of memory from the subterranean shadows of history and war. “Khamsa” was among 10 films in competition and won the Kabuku Award (given to a film “that is not constrained by conventional values but challenges and creates something novel and innovative”) for its successful use of unorthodox techniques: simplified paper cut-out character designs set against talismanic 3D background imagery, its rich symbolism drawn from North African folklore.

The award was handed to Chiheb by jury chairman Mamoru Oshii, the celebrated director of anime classic “Ghost in the Shell.”

Mamoru Oshii

Mamoru Oshii“I admit that the idea of meeting Oshii made me a little nervous,” says Chiheb. “One of the main inspirations for ‘Khamsa’ was his first film, ‘Angel’s Egg.’ But what made me most proud was when he said that he found the minimalist character design of ‘Khamsa’ interesting, and that he saw himself using characters in this style in his future films. In my eyes, that may have more value than the award.”

The wide array of visual effects and subject matter alike suggested that wherever it is created, animation has become an ideal medium for addressing complex biographical, historical, geopolitical and literary narratives.

Pierre Foldes’ “Blind Willow, Sleeping Woman,” winner of the NIAFF grand prix, strings together six short stories by novelist Haruki Murakami into a haunting and deeply moving portrait of urban anomie and suspended lives. Like many festival entries, the film looks like nothing I’ve ever seen before, mimicking facial expressions with unnerving specificity while conveying through stark outlines and strategic blurs the vague, untethered realities of our heavily mediated modern world.

"Blind Willow, Sleeping Woman"

"Blind Willow, Sleeping Woman"Foldes, a director, painter and composer who was raised in France, couldn’t attend this year’s NIAFF but has spent enough time in Japan to sketch its backgrounds acutely. He says that apart from his father, computer animation pioneer Peter Foldes, all of his chief influences in animation are Japanese artists.

“It’s a great honor to receive such a prize, especially in Japan where animation has been brought to an extremely high level of expression,” he tells me from New York, where he is overseeing the film’s North American opening. “My references in animation are all Japanese. The fact that I adapted an amazing Japanese author could be seen as quite challenging for someone coming from another culture, so I’m very happy that the great Oshii as well as the other members of the jury appreciated my work.”

Prize-winning international directors with Oshii in Niigata.

Prize-winning international directors with Oshii in Niigata.While its focus was on overseas talent, the first year of NIAFF was hardly lacking in local appeal. Big-screen showings of global box-office hits like “Demon Slayer: Kimetsu no Yaiba the Movie — Mugen Train” and “Jujutsu Kaisen 0,” and art-house triumphs “Inu-Oh” and “In This Corner of the World” were accompanied by retrospective programs featuring the works of Makoto Shinkai (“Your Name.,” “Suzume”) and Katsuhiro Otomo (“Akira”). The return of octogenarian Japanese director Rintaro after a 14-year hiatus was highlighted by a special screening of his short film “Nezumikozo Jirokichi,” a tribute to late movie director Sadao Yamanaka.

Otomo (Akira), Watanabe (Cowboy Bebop), Ohshii (GiTS)

Otomo (Akira), Watanabe (Cowboy Bebop), Ohshii (GiTS)But the festival’s biggest coup may have been its in-the-flesh guests. Oshii, Otomo and Shinichiro Watanabe (“Cowboy Bebop”), a trio of anime heavyweights, all appeared onstage and casually strolled the hallways of Niigata’s intimate, uncrowded venues, easily accessible and happy to chat with passersby. It’s hard to imagine all three showing up in person at the same event anywhere else. Eat your heart out, Tokyo and Osaka.