Roland Kelts's Blog, page 11

July 7, 2021

Appearing at the A-JAPAN Japan Contents Showcase July 8th - 11th

Hope you'll join us for a look at the content future from Japan.

July 1, 2021

My second "Letter from Tokyo" for The Japan Society of Boston

LETTER FROM TOKYO, JUNE 2021: CHOOSING ONSEN OVER OLYMPICS

My favorite kind of getaway is a stay at an onsen-yado (Japanese hot springs hotel). It used to rotate among my top three, but the pandemic has edged it into first place.

An onsen-yado relieves you of the burden of choice as soon as you step inside. Your shoes and luggage are whisked away. You are quietly ushered to your room. Padding through the halls, you are told when your dinner will be served and shown what you will wear: a robe, a sash, slippers—with two-toed tabi socks optional. No matching of ties to dinner jackets or puzzles over pumps or flats.

Then you soak in hot, mineral-rich water that transforms your joints into gentle friends of your body.

Early June is a good time for hitting onsen. Spring holidays are over but the kids are still in school, and tsuyu’s rainy season grays take the edges off.

In Tokyo, May’s bracing sun can make everyone look hurried and feel hyperactive. June reminds you—what’s the point?—but isn’t yet so humid that you couldn’t hurry anyway.

This May, when it became clear that Tokyo’s “state of emergency” declaration over Covid-19 would be extended yet again into late June, I knew it was time to pack the overnight bags, laptop and books, and take the train down the Izu peninsula, roughly two hours south of Tokyo by rail.

I realize that sounds counterintuitive. Irresponsible, even. Doesn’t a state of emergency mean you should stay put and hunker down at home? What kind of emergency sends you on holiday to a hot springs?

But where I live in central Tokyo, I share each square mile with over 16,000 neighbors. If I don’t immediately see someone strolling below when I look out one of my windows, I will very soon. And the moment I step from my building’s courtyard to the sidewalk, I join the coursing crowds weaving past and dodging one another on sidewalks that can barely accommodate three adjacent modestly-sized bodies.

Choosing to wear a mask, sanitize, and speak quietly or not at all is possible, and most of us choose to do all three. Social distancing, however, is not.

Comparatively, there was no one in Izu. And no one on the quaint old Izu-bound Limited-Express Odoriko line, whose empty lace-doilied seats feel a little like a theme park ride from the 1980s, reassuringly out-of-date.

And in historic Shuzenji, whose fairy-tale Kamakura-era pathways are usually clogged with tourists, local craftspeople and rickshaw-runners, you could pause in the bamboo forest and breathe in the air, letting your mask slip for a moment or two near the naked Katsura river.

The onsen-yado staff did what they do: served omakase meals designed to highlight local seafood and vegetable specialties on menus over which you had absolutely zero choice. I soaked for hours, read two short books, wrote in fits and starts and took long walks along the river, taking too many photos of some late-blooming wisteria.

Near Shuzenji Temple, founded in the 9th century, I saw three old Tokyo 2020 Olympics banners announcing that the torch relay would soon pass through town. The juxtaposition was rich: something about to happen felt more dated than something truly ancient.

June 10, 2021

My interview for the Deep In Japan podcast

I was just interviewed for the podcast about growing up half-Japanese, writing , editing the literary magazine Monkey: New Writing from Japan, writing "The Fifth Flavor," reading Nabokov and Canett ... and catching clout chasers who crib your ideas. Also chatted about my new book, the novel, my kindergarten years in Morioka, living with my grandparents and falling in love with Ultraman. Good fun all around thanks to Jeff Krueger and his team. (pic: Ultraman Taro & Mini Roland in Tokyo Tower.)

Deep in Japan ·

May 27, 2021

My op-ed on why Japan's vaccine rollout has been so slow

Japan is world-famous for its punctual and efficient customer service, and for most of the pandemic—with the country under varying states of emergency—this has been a godsend.

Food deliveries arrive at your door, hot and hermetically sealed, up to 10 minutes earlier than promised. Packages sent from every corner of the country are handed to you the following morning by gloved couriers. Convenience stores really are convenient—located everywhere, well-stocked, impeccably sanitized and open 24/7, even in the smallest towns.

In Tokyo, public clocks are ubiquitous. While it is true that you can set your watch to the departures and arrivals of Japan's trains, from the high-speed shinkansen to more humble commuter rails and subways, you do not really need a watch here.

Yet now, when Japan does need to keep pace with global vaccinations just two months before the start of the 2020 Tokyo Olympics, the nation is way behind and scrambling to catch up. Only 5% of its population has been fully vaccinated, putting Japan at the very bottom of the 37 developed nations that make up the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development.

What gives? Why is the country faltering on vaccine delivery when all the conventional measures—history, culture, commerce, and the imminent worldwide scrutiny of the Olympics—would point to Japan being a regional if not global leader?

I call it Japan's systemic myopia: an obsession with the proper functioning of every node in the system without a bigger vision of what the system should be doing.

Japan's business, cultural and political models assume a steady state that is under control so it can afford to sweat the small stuff. When Japan's systems are isolated from interruption, they are built to perfection. Precision in getting the details right makes daily life here functional, safe and reliable. It is a great place to call home.

But when it comes to long-term, large-scale thinking to tackle crises or big projects—like fast-tracking a nationwide vaccine rollout for a global virus while hosting an international sports extravaganza—Japan clings to antiquated step-by-step ways, from requiring in-person employee hanko stamps to lengthy vaccine approval procedures, regardless of realities.

Last summer, Finance Minister Taro Aso cited Japan's superior "level of cultural standards" as the reason for its then low number of COVID fatalities. Now with mortalities exceeding 12,000, Aso is silent.

The most wrenching example of Japan's mental disjunction occurred 10 years ago, after the 2011 meltdowns at the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant. Six days into the government's frantic response, television footage showed a lone helicopter hovering 300 feet over the plant, dwarfed by the buildings below, spraying 2,000 gallons of water over a damaged reactor's smoking dome—water dispersed by the wind into contrails of white vapor that were blown out to sea.

[image error] A video grab shows a helicopter dumping water on a reactor to cool overheated fuel rods inside the core at Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant on Mar. 17, 2011. © Fukushima Central Television/Kyodo

Prime Minister Naoto Kan had ordered the single Self-Defense chopper in a desperate effort to stop the damage from spreading. But to me, it looked like a pitiable symbol of too little, too late.

I am reminded of that helicopter now, as the government reinstates short-term states of emergency at the very last minute, requesting restraint but offering no guidance or game plan, spraying mist over COVID's toxic dome of infections, hospitalizations and deaths.

To be fair, in Japanese art, engineering and cuisine, less is usually best. Most of its prized creative achievements champion the miniature and minimal: exquisite netsuke dolls, lacquerware and ceramics, spare flower arrangements and haiku poetry, portable electronics engineering and hand-carved wood joinery. Even its unrivaled, pioneering forms of popular culture, manga and anime, rely on highly selective line work and limited-frame animation techniques for their unique appeal.

The success of postwar Japan has been predicated on its ability to think big in a small space. The entire archipelago covers fewer square miles than the U.S. state of California but is home to over three times the state's population. Seventy percent is mountainous terrain that is largely uninhabitable, with scant acreage for farmland and no native oil reserves. For centuries, and out of necessity, Japan has excelled at crafting small things with few resources that have very big effects.

The island nation has thrived in periods of isolation but floundered in its colonial ambitions, welcoming outsiders only warily. Immigration remains low, and since the first state of emergency last April, a long list of foreign nationals has been barred entry. Until Thursday, only one foreign vaccine, Pfizer-BioNTech, was allowed in.

A certain degree of inward-looking self-regard has long suited and rewarded the native sensibility. During the 200-plus-year sakoku—closed country—period from 1639 to 1853, while Western powers were tripping over themselves to secure global trade routes and riches from Asia, Japan shut its ports and saw its civilization flourish. Until the United States forced the country open in 1853 with its armada of potential superspreader Black Ships, Japan was doing just fine under self-imposed lockdown.

But Japan has also proven that it can implement big-picture policies and programs when it comes under enough pressure to do so—especially when that pressure comes from without. Gaiatsu—foreign pressure—largely motivated the country's acquisitive study and adaptation of Western technologies in its drive toward modernization during the Meiji period (1868-1912), when the virtues of education and travel were prized.

Pressured again by the West nearly a century later, at the end of World War II, Japan implemented broad plans for growth and societal change. Not coincidentally, Japan's globally-minded spirit was inspired by its first and so far only summer Olympic Games in 1964. As author Robert Whiting points out in his recent memoir, "Tokyo Junkie," in 1960 less than a quarter of Tokyo neighborhoods had a modern sewage system. Four years later, by the time the torch was lit, they had the fastest train in the world and plenty of flush toilets.

Today as I write, the clocks are all correct, deliveries prompt, stores fully stocked. But what looks like a consistent sensibility from the outside manifests in a million discrete and siloed obsessions, without the coordination needed to trigger meaningful action. While Japan's image abroad is more attractive than ever, its systemic myopia at home creates a muddled micro-focus that lacks vision, as the country's weak vaccination planning reveals.

Government and corporate offices in Japan tend to be as precise as they are sclerotic. Each individual at each cubicle knows how to dot their i's and cross their t's, making daily life smooth and efficient. But when it comes to conceptualizing anything beyond one's desk, their screens go blank.

A growing chorus of overseas voices is now calling on Tokyo to cancel the games, and a domestic petition has over 400,000 signatures. But it remains to be seen if pressure of any kind can jolt Japan out of its myopia this time. What is clear is that a crisis like COVID on the cusp of an international event like the Olympics cannot be solved by one department micromanaging its own workspace.

May 14, 2021

My first "Letter from Tokyo" for the Japan Society of Boston

Photo: Nancy Keystone

Photo: Nancy KeystoneLetter from Tokyo, May 2021: Tokyo’s pandemic time warp

This March, Kyoto’s cherry blossoms hit peak bloom on the earliest date recorded in 1200 years. Not 120. 1200.Here in Tokyo, the sakura trees below my office began blooming on the earliest date recorded in 60 years—after a winter so mild I never wore a scarf or donned footwear heavier than sneakers.

Spring this year feels like early summer. Midday temps reach the upper 70s F / 20s C. If you brave the sun without a hat, you sweat.

Tokyo’s weather is accelerated and overheated. But everything else feels frozen.

After another week of less-than-golden holidays hunkered at home, we Tokyoites are watching a ‘fourth wave’ of Covid infections sweep the country. It feels redundant and endless. Vaccination appointments that seem plentiful elsewhere haven’t even started here. And we’re now preparing for two weeks of Olympic Games set to begin in just over a couple months, on July 23rd of 2021—an international extravaganza and potential superspreader event that few in Japan want, and that is still being promoted around town on posters, banners and billboards as: “Tokyo 2020.”

Wha?

All of us have had our internal clocks scrambled by the pandemic, especially in cities, where time blares down relentlessly from giant video screens and railway platforms. But in this city, where seasonal change is nearly fetishized, trains and buses depart on the minute, and prerecorded five o’clock chimes ring from loudspeakers in every neighborhood at each day’s end, pandemic time feels completely out of whack. And with its current triple-whammy of resurgent virus, absent vaccines, and postponed and displaced Olympics, Tokyo’s time-warp disorientation may top them all.

What are Japan’s seasons without their celebrations? With no bonnenkai or shinnenkai parties, no shrine festivals or hanami shindigs, and only sparse, muted and masked-up school graduation and entrance ceremonies?

I’ve worn paths between my office and local grocery and convenience stores. Most everyone wears masks and keeps conversation minimal (except for one of the male combini clerks, who regularly asks me about my work before issuing updates on his infant son’s first steps). The few who go maskless are out after hours and are very young or very drunk or both, and by that time there’s plenty of space on the sidewalks for social distancing.

Big department stores are supposed to be closed, but local shops and eateries that have survived are open, the latter with limited hours and takeout menus. This morning the TBS network reported that Golden Week visitors to the major shopping hubs in Ginza, Shibuya and Shinjuku were up twofold over the same period last year. I studiously avoid all three.

I am fortunate to live within walking distance of uniquely gorgeous parks: Shinjuku Gyoen, Meiji Jingu and Yoyogi Koen. Shinjuku Gyoen is closed until May 31st, but the other two remain open with limited access. Without their greenery, open skies and patches of grass, water and birdsong, I think I’d go insane.

The other day at Café Mori near the entrance of Meiji Jingu, I whined yet again to a friend about missing travel. I don’t miss airports, I said, or the rest of the scramble from point A to B. But I miss the sensation of landing somewhere different, of seeing a new vista spread out beneath the porthole window as the plane descends.

“I know,” she said. “It’s like we’re still stuck on the plane. Forever.”

May 6, 2021

My interview for the CBC about Black representation in Japanese popular culture

I was recently interviewed by the CBC about Japanamerica and the rise of Black representation in Japanese popular culture. Investments from Netflix and other big global media companies are bringing multiculturalism to Japan's thriving creative industries. But are we ready for a multicultural Japan? (You can access the interview here.)

[Excerpts]

What is it about anime that makes streaming giants like Netflix so eager to invest in not only the content, but in studios and in talent?

On the one hand, it crosses borders really well. Streaming services are global. They're not just located in one country or devoted to one culture.

I also like to think of anime characters as anime tribes. Take a movie star in the U.S. or China and they may not be that well-known outside of their own nation, but anime characters have this unique ability — partly because they're just illustrations — to travel very, very well.

So streaming services are looking for content that will appeal not only in Toronto, but also in Toledo, Ohio, and in Tianjin, China, for example.

But it's still very much identified with Japan. How are Japan's anime heavyweights responding to this injection of interest and capital from international or American groups like Netflix?

They're thrilled. There are anime artists here who never imagined that they would have fans in Paris, for example.

Also, there's more money pouring into the industry than I've ever seen — record-breaking sums are being paid to studios to produce.

If you want to look at a downside, there's pressure on anime directors and creators right now to appeal to a global audience, which is something they really haven't faced in the past.

Most anime was made for a Japanese audience and now they're thinking, "Is this going to work in somebody's living room in Nebraska?"

Does it still qualify as anime if you have a giant American streaming platform that's calling the shots and these American artists giving their input?

That's something that we're seeing evolve right now, which is a kind of a new category or a new genre, which I've heard people call "Anime-inspired work."

Now, I don't want to diss anybody who worked on Yasuke, because it's made in Japan, it's made by a Japanese studio right here in Tokyo. I don't want to say that anime-inspired is somehow weaker or lesser than straight-ahead Japanese anime.

It is a kind of new category that's emerging where you have international financing and international creatives who might be taking anime in a new direction. I think that's the exciting part.

Japan is known for being walled off in some ways, so they might be averse to some outside influence. Do you think that Netflix is changing the way Japanese people view television or consume anime themselves?

When I wrote Japanamerica, there were a lot of Japanese who genuinely and sincerely asked me why anyone outside of Japan would watch anime. They were puzzled. [They'd say,] "You have Disney, you have Marvel, you have Pixar. Why does anybody watch this?"

I do think the younger generation has gotten the point that there is something distinctive about the Japanese approach — everything from the art style, which is a very finely-honed, two-dimensional approach to animation. So not the 3D Pixar look, but really finely outlining shapes and very detailed backgrounds.

Then there's something about the storytelling. It's not so limited to the three-act Hollywood action film style. So you get these psychological probings into characters and these often darker story lines, and aestheticized violence that you would never see in an animation from the West unless it was an underground work.

I think Japanese are starting to realize that what they produce here is special and appeals globally. At the same time, it's still a fairly insular society. It's an island nation. There aren't very many immigrants in Japan, and so maybe the plus side of that is a lot of anime is still made for Japanese.

Netflix is sponsoring an anime school in Japan. How do you think that will go over?

I think it'll actually go over very well. A lot of people in the industry and outside the industry — [and] a lot of fans here in Japan — are aware of the fact that talent is running thin on the ground. That's partly because studios here years ago started outsourcing work, just as back in the 60s, big U.S. companies like Warner Bros. and Disney outsourced work to Japan.

So it's the same economic cycle. Japan started outsourcing work to Southeast Asia and to Korea. The result of that, of course, is that there are fewer and fewer talented artists on the ground here in Japan, especially in the younger generation.

Do you think that the Japanese anime industry is going to continue to support and nurture foreign talent like LeSean Thomas and celebrate them when they have success?

I do. And I think one of the crucial features, of course, of LeSean's story is that he's Black. The sort of stereotype of the Western anime fan or Japanese pop culture fan has been, frankly, nerdy white guys with toy robots in their basement.

As someone who has Japanese heritage [like myself], that's gotten to be a bit tired. It's really nice to see people of color and someone like LeSean, who is a Black guy who grew up in a housing project in the South Bronx.

To go from the South Bronx and to come all the way to Tokyo because of your passion, I think it's great for Japan, of course, because Japan is a relatively mono-ethnic society. And to have non-Japanese coming in and loving and respecting Japanese art, I think that's great for Japan.

I also think, and maybe this is more important, it's really great for young people of colour — for a young Black kid sitting in Chicago who gets into anime and he sees that here's a Black man from America who's making anime.

Whatever that particular kid thinks of Yasuke, he's going to see a Black character represented on the screen and he's going to find out that a Black man made it in downtown Tokyo.

•

May 3, 2021

My review of YASUKE: Black culture meets Japanese history in an anime first

African samurai earns hero status in new anime ‘Yasuke’

Of the record-high 40 original anime programs Netflix is launching this year, none may be better pedigreed or more timely than “Yasuke,” a six-episode series about Japan’s only known Black samurai.

Voiced and executive produced by Oscar nominee LaKeith Stanfield (“Atlanta”), scored and co-produced by Grammy nominee Flying Lotus, with Grammy winner Thundercat collaborating on the opening song, animated by studio MAPPA Co., Ltd (“Jujutsu Kaisen”), designed by Takeshi Koike (“Redline”) and created and directed by LeSean Thomas (“Cannon Busters”), “Yasuke” is more than just a nod toward diversification and representation in the wake of the Black Lives Matter movement. It’s an open embrace of both — arguably a first for Japan’s anime industry.

The historical record on Yasuke is scant, leaving large gaps that the artists fill with a smorgasbord of supernatural and sci-fi anime tropes. The result is a headlong rush through a tangle of plots spread too thin at times for the sprawling cast to bear — but with gorgeously animated flashes of brilliance, especially in the battle scenes, that may leave you pining for the broader canvas of another season.

Yasuke arrived in 16th-century Japan as the slave of an Italian Jesuit priest during the nanban trade with Portuguese merchants. An African by birth, he drew the attention of legendary feudal lord Oda Nobunaga, becoming the only non-Japanese in the daimyo’s service.

During the Sengoku “Warring States” Period, service meant becoming a samurai. In 1582 Yasuke fought for Nobunaga at the notorious Honnoji Incident in Kyoto, where his master committed ritual suicide.

The series opens with a fiery plunge into that battle, its vibrant hues washing over Koike’s finely etched 2D character designs and enlivened by MAPPA’s kinetic CG effects and rotoscope animation.

Samurai and giant mecha warriors soar through tiers of flames behind a troop of dancing Shinto priests. Purple kanji characters flash across the sky as a supernatural spirit rains over the soldiers. Blood spurts through the air and splatters across the screen.

Flying Lotus’s ethereal synth-driven score echoes Pink Floyd’s 1970s classic “The Dark Side of the Moon” and Vangelis’ original “Blade Runner” soundtrack (FlyLo composed music for the “Blade Runner Black Out 2022” anime short in 2017). And you won’t need the credits to remind you that MAPPA is the same studio now making the final season of the equally blood-drenched “Attack on Titan.”

The chemistry between Stanfield’s Yasuke and Takehiro Hira’s (“Giri/Haji”) Nobunaga is among the series’ highlights. Whenever they’re together, Stanfield, in particular, seems energized, shaken out of his character’s PTSD stoicism by the ravings of his eccentric lord.

Their first scene depicts Nobunaga as a leader gone mad, preaching populism while drinking himself blind as his army is crushed and the temple walls collapse. This is Hitler in his bunker, Napoleon at Waterloo. “And look at you, Yasuke,” he says, teetering. “From servant to samurai. The only one who didn’t betray me. We should drink to that.”

Yasuke begs Nobunaga to persevere in his quest to unify Japan but is bound by duty to decapitate his lord on command. Twenty years later, Yasuke, too, is half-broken, lurching hungover from his futon, surrounded by empty sake flasks and samurai mementos — a dissolute veteran reduced to the status of local boatman paddling villagers upriver.

Flashbacks to Yasuke’s first meeting with Nobunaga are dramatized with knowing winks. At the nanban port, he wearily explains his racial features to a clueless attendant trying to wash the “dirt” off his skin, and recites his name in Portuguese to the befuddled Nobunaga, who promptly renames him “Yasuke” in exasperation.

The rest of the story splits into too many narrative threads to account for here. At its core, Yasuke becomes the paternal caretaker of Saki, a sickly girl from his village whose outsized psychic powers threaten to overwhelm her. The two must team up to defeat the evil Hojo Daimyo, a female demon spirit ruling Japan, and her dark army.

Trying to abduct Saki is a motley crew of bounty hunters hired by a diabolical Catholic priest, including a giant robot with a Baymax-inspired voice, a beast-mutant Russian woman who transforms Hulk-like into a growling bear, and a muscular African shaman.

Homages to anime classics like “Lone Wolf and Cub,” “Samurai 7” and “Cowboy Bebop” abound. But unlike 2007’s “Afro Samurai,” whose Black hero and sidekick were voiced by Samuel L. Jackson, this is no pastiche of Blaxploitation or jidaigeki historical drama stereotypes. Yasuke remains a beguiling cipher, sullen and wounded, haunted by his past and increasingly uncertain of his motivations.

Unsurprisingly, Yasuke’s zeitgeist-tailored script has been kicked around in Hollywood by big names with budgets to match. In 2019, the late Chadwick Boseman (“Black Panther”) announced that he had signed on to play the character in a live-action film, promising it would be “a cultural event.”

But six months before Boseman’s media blast, director Thomas, 45, had already laid claim to the story’s revival as an anime series. “I had started playing with the idea of doing a biopic back in 2016,” Thomas tells me at a meeting in Tokyo. “By the time the Boseman news came out, I was already working on character designs with Koike. I knew Hollywood would reduce it to a slave narrative, and I didn’t want that. My Yasuke would be a new kind of anime action hero.”

Thomas first learned of Yasuke’s biography a decade earlier, when he came across a website about “Kuro-suke,” a Japanese children’s book published in the 1960s. The few blurry PDF files he found online showed a balding Black man in baggy Portuguese trousers bearing a samurai sword.

Yasuke popped up again on Thomas’s radar as a minor character in an old video game called “Nobunaga’s Ambition.” He was hooked, but wasn’t yet ready to tackle the story until he had original work under his belt. His 2019 series, “Cannon Busters,” revealed a singular gift for tossing quality anime scraps into a Black culture blender to refresh the medium.

With their deep dive into Japanese historical lore and a healthy dose of self-aware wit (“Yes, I’m a Black man who speaks Japanese!” Yasuke barks at one of the skeptical bounty hunters), Thomas and his ace team of artists are remixing a higher grade of ingredients this time. The open-ended finale to season one has me hoping they get another shot at the blender in an even bigger kitchen.

April 28, 2021

My story about six-time Oscar nominee MINARI, Asian immigration and anti-Asian hate crimes

From NIKKEI.

Oscar-nominated 'Minari' upends Asian immigrant stereotypes

Actress Esther Moon on playing Mrs. Oh, a Korean immigrant who finds peace in rural America

TOKYO— A little over a year after Bong Joon-ho's coruscating satire of class conflict, "Parasite," became the first foreign-language movie to win Best Picture at the Academy Awards, another film with a Korean lead cast, plenty of translated subtitles and dogged money woes is up for the same top honor.

"Minari," directed by Korean American Lee Isaac Chung and based partly on his childhood, follows the Yis, an immigrant family of four, as they move from Los Angeles to rural Arkansas to start a new life on a farm. While Chung's script and direction are far more restrained than Ho's, the reception to his film has been anything but.

Released in the U.S. during an alarming spike in anti-Asian hate crimes, "Minari" won Best Foreign Language Film at February's Golden Globe Awards and has since received numerous accolades, including a British Academy Film Award earlier this month for 73-year-old actress Young Yuh-jung.

In mid-March, the Motion Picture Academy announced that "Minari" had been nominated for six Oscars, including its two plum prizes, best picture and director. The next day, six women of Asian descent, four of them Korean, were murdered in a mass shooting in Atlanta.

"That happened right after our nominations came out," Los Angeles-based Korean actress Esther Moon recalls during a video interview from her home. Moon, 44, plays Mrs. Oh, a middle-aged Korean immigrant and long-settled Arkansas resident who works at the factory where the Yi parents begrudgingly take day jobs.

"It was this moment of an incredible high: 'Minari' got six Oscar nominations!" she says. "Asians were celebrating, and then 24 hours later there's this shooting targeting Asian women. It felt like we were on the rise and then, bang: you better know your place. It felt like a smack down."

Moon recognizes Mrs. Oh as a woman freed of the rigid class hierarchies and responsibilities of Korean society and wary of reviving them in her adopted American home, however alien it may still feel. "There are a few of us here," Oh tells the Yi family matriarch, Monica, when asked about other Korean residents in the area. "But most of us left the cities for a reason. To escape."

"She wants to get close enough to other Korean immigrants to get some authentic food and ingredients," Moon says, "but she doesn't want to be judged anymore. You know, we Koreans fight amongst ourselves a lot, and Mrs. Oh got away from all that. She's doesn't dream of a better life. She's at peace living in the American countryside among these naive, innocent white people."

Moon's Mrs. Oh is one of several characters in the film that upend stereotypes of the Asian immigrant experience in the U.S. "Minari's" white Americans are largely marginal figures, seen through the family's eyes as slow-moving provincials with eccentric religious rituals—a farmhand speaks in tongues and literally bears a cross on his shoulder every Sunday—and blinkered racist assumptions.

Harvard professor Alexander Zahlten, who specializes in East Asian media, praises the film's "different models" of the diaspora experience in the U.S. Moon's character, he says, is a fresh reminder that immigrants migrate for complex reasons.

"Mrs. Oh is pivotal to me because she counters the idea that immigrant communities are defined by race, language, or ideas from a cultural background. In fact, it may be the community that some immigrants are actively fleeing," says Zahlten.

Moon's personal upbringing as a "parachute kid," moving between South Korea and the U.S. until the age of 16, when she settled in the latter, made her acutely sensitive to the dichotomies between Asian and Western cultures.

"Minari" puts the spotlight on both. In the U.S., all four members of the Yi family are forced to reinvent themselves in the vast Arkansas landscape with fewer societal restrictions but also no safety net. Failure and poverty—when money gets tight, their water stops running—are always imminent, just one stroke of bad luck away.

"There was definitely less academic pressure once I came back to the U.S. to live at 16," Moon says. "In Korea, you have one shot at college, whereas in the U.S. you can have all kinds of fallback plans. But it's still really hard to get by here. Even college-educated Koreans will take manual labor jobs just to get their green cards."

The verdant southern landscape dominating nearly every shot of "Minari" marks a departure from recent Asian cinema reaching international audiences. While "Parasite" and "Shoplifters" (Japanese director Hirokazu Koreeda's Palme d'Or-winning 2018 release) both take hard looks at economic inequality through the lens of Asian family ties, they are set in densely crowded Asian metropolises. Their stories take place in intimate quarters at a comfortable remove from the daily lives of most Western viewers.

"Minari's" wholly American pedigree—director and screenwriter Chung was born in the U.S.—sparked controversy at the Golden Globes, where it was confined to the foreign-language category despite being filmed and financed in the U.S., and having several lines of English-language dialogue. "This film is about a family," Chung said in his acceptance speech. "It goes deeper than any language."

Oscar-nominated Chinese-Korean American filmmaker Christine Choy, a professor at New York University, agrees. "It's an unusual story because we never see Asians in the U.S. as farmers," she says. "This is an Asian family stuck in the middle of nowhere who manage to keep their love and support for each other alive."

For Moon, among Chung's greatest achievements is showing racism without vilifying the characters who express it. She cites an otherwise placid scene at a church reception, where a white boy asks David, the Yis' youngest child, played by 8-year-old Korean actor Alan S. Kim, "Why is your face so flat?"

"Most people probably skipped over that line," Moon says, "but it just screamed at me. I grew up in America hearing that same question, but it wasn't uttered in a mean way, especially by other kids. They were just genuinely curious why, to them, my face looked so flat. It was the innocence of inexperience, not outright bigotry."

•

Roland Kelts is the author of "Japanamerica: How Japanese Pop Culture Has Invaded the U.S." and a visiting professor at Waseda University.

April 15, 2021

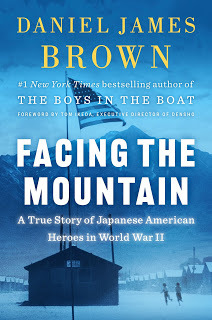

Live Event: Japanese Americans in World War II—"Facing the Mountain" w/Daniel James Brown in Boston

Terribly well-timed to the rise of anti-Asian hate in the US, I will be talking about this brave and important new book, Facing the Mountain: A True Story of Japanese American Heroes in WWII, with author Daniel James Brown in Boston.

The event is hosted and sponsored by Boston Public Library, GBH, Japan Society of Boston and New England Historic Genealogical Society.This is a critical time to reexamine the Japanese American experience of WWII—incarcerated in the camps at home, and fighting for the US overseas. We hope you'll join us.

Daniel James Brown with Facing the Mountain: A True Story of Japanese American Heroes in World War II

Virtual Event: Wednesday, May 12 at 6 p.m. ET / 11 p.m. UK / Thursday, May 13th at 7 p.m. JST

• Register here

Moderator: Roland Nozomu Kelts, author, journalist, editor, and lecturer

Presented in partnership with Boston Public Library, the Japan Society of Boston, and GBH Forum Network

From the #1 New York Times best-selling author of The Boys in the Boat, a gripping World War II saga of patriotism.

An unforgettable chronicle of war-time America, Facing the Mountain portrays the kaleidoscopic journey of four Japanese-American families and their sons. One demonstrated his courage as a resistor. The three others volunteered for 442nd Regimental Combat Team and displayed fierce courage on the battlefields of France, Germany, and Italy, where they were asked to do the near impossible in often suicidal missions. Based on deep archival research and extensive family interviews, Brown also tells the story of these soldiers’ parents, immigrants who were forced to shutter the businesses, surrender their homes, and submit to imprisonment on U.S. soil. Here, as in The Boys in the Boat, he explores the questions of what “home” means, what makes a team work, and who gets to be a “real American.”

Don’t miss the author’s presentation and discussion with Roland Kelts about this powerful new work.

Daniel James Brown is the #1 New York Times bestselling author of The Boys in the Boat, which spent over 135 weeks on the New York Times bestseller list; The Indifferent Stars Above; and Under a Flaming Sky. A multi award-winning writer, he lives in Washington State, near Seattle, and has taught writing at San Jose State University and Stanford University.

Roland Nozomu Kelts is a Japanese-American writer, editor, and lecturer; author of Japanamerica: How Japanese Pop Culture has Invaded the US. He writes for publications in the US, Japan, and Europe, and is a commentator for CNN, the BBC, NHK and National Public Radio. A contributing editor of MONKEY: New Writing from Japan, he was also a Nieman Fellow at Harvard University. He lives in Tokyo.

April 11, 2021

Video: Interview for Hype Magazine

I was recently interviewed in Tokyo by Darren Paltrowitz of Hype Magazine. He was in New York City, my former hometown.

We talked about my gig hosting the Japan Cats doc, but also a lot of stuff I hadn't planned to discuss, like pandemic work, my forthcoming Blade Runner book, the novel, the other books, my Who T-shirt and interviews with Pete Townshend, the shows "Better Call Saul," "Westworld" and "Barry"—and my cat.

Darren's opening gambit disarmed me.

Vid's up at YouTube: