Angela Ackerman's Blog: Writers Helping Writers, page 31

October 14, 2023

Character Type & Trope Thesaurus: Antihero

In 1959, Carl Jung first popularized the idea of archetypes���”universal images that have existed since the remotest times.” He posited that every person is a blend of these 12 basic personalities. Ever since then, authors have been applying this idea to fictional characters, combining the different archetypes to come up with interesting new versions. The result is a sizable pool of character tropes that we see from one story to another.

Archetypes and tropes are popular storytelling elements because of their familiarity. Upon seeing them, readers know immediately who they’re dealing with and what role the nerd, dark lord, femme fatale, or monster hunter will play. As authors, we need to recognize the commonalities for each trope so we can write them in a recognizable way and create a rudimentary sketch for any character we want to create.

But when it comes to characters, no one wants just a sketch; we want a vibrant and striking cast full of color, depth, and contrast. Diving deeper into character creation is especially important when starting with tropes because the blessing of their familiarity is also a curse; without differentiation, the characters begin to look the same from story to story.

But no more. The Character Type and Trope Thesaurus allows you to outline the foundational elements of each trope while also exploring how to individualize them. In this way, you’ll be able to use historically tried-and-true character types to create a cast for your story that is anything but traditional.

DESCRIPTION: This trope is a subversion of the hero archetype in the form of a main character who lacks the qualities of the typical hero. Morally ambiguous and often self-serving, they tend to be deeply wounded and flawed individuals with stories that often end in tragedy.

FICTIONAL EXAMPLES: Severus Snape (The Harry Potter series), Scarlett O’Hara (Gone With the Wind), Holden Caulfield (The Catcher in the Rye), Harley Quinn (the DC universe), Tony Soprano (The Sopranos), Walter White (Breaking Bad)

COMMON STRENGTHS: Adaptable, Ambitious, Bold, Confident, Creative, Decisive, Discreet, Focused, Independent, Industrious, Intelligent, Meticulous, Patient, Perceptive, Persistent, Protective, Resourceful, Talented

COMMON WEAKNESSES: Abrasive, Cocky, Controlling, Cynical, Devious, Dishonest, Disloyal, Greedy, Hypocritical, Manipulative, Obsessive, Perfectionist, Rebellious, Reckless, Selfish, Sleazy, Unethical, Vindictive, Violent, Volatile

ASSOCIATED ACTIONS, BEHAVIORS, AND TENDENCIES

Being pragmatic about what needs to be done

Working according to their own moral code (which others may not agree with)

Having a strong survival instinct (being resilient)

Determinedly pursuing their goals

Having good listening skills

Being secretive

Knowing how to read people

Fooling even their closest loved ones into seeing the antihero the way they want to be seen

Refusing to entertain doubts about their motives or choices

Doing whatever it takes to save themselves

SITUATIONS THAT WILL CHALLENGE THEM

Someone discovering a secret the antihero desperately wants to keep under wraps

Being betrayed by someone close to them

Working with someone who points out their hypocrisy

TWIST THIS TROPE WITH A CHARACTER WHO���

Successfully navigates a change arc instead of ending up the same or worse than where they started

Has a unique skill or hobby

Has an atypical trait: flamboyant, nature-focused, scatterbrained, witty, wise, etc.

CLICH��S TO BE AWARE OF

The emotionally flat antihero (or one with no positive emotions)

The lone wolf antihero who has no friends

The antihero with no character arc and no capacity to change

Other Type and Trope Thesaurus entries can be found here.

Need More Descriptive Help?

Need More Descriptive Help?While this thesaurus is still being developed, the rest of our descriptive collection (16 unique thesauri and growing) is accessible through the One Stop for Writers THESAURUS database.

If you like, swing by and check out the video walkthrough for this site, and then give our Free Trial a spin.

The post Character Type & Trope Thesaurus: Antihero appeared first on WRITERS HELPING WRITERS��.

October 12, 2023

How to Craft a Top-Notch Blurb

By Erica Converso

Your book is unique ��� unlike any other in the world. But the structure of a well-crafted blurb will not ��� and should not ��� be. A blurb is the copy on the back cover of a book or the sales webpage, explaining what the book is about, usually about two to three paragraphs in length.

Blurbs are a tool for writers to explain to future readers what they���ll be getting if they choose your book. To appeal to them effectively, writers should answer the reader in the same way. This means that blurbs from nonfiction to romance have much in common.

Your reader will want to know certain things before they settle in with your story. And everything they want to know will begin with:

Who?

For fiction, who is your protagonist? Give us something about her. Let���s look at the blurb for The Color Purple, by Alice Walker.

���Celie has grown up poor in rural Georgia, despised by the society around her and abused by her own family. She strives to protect her sister, Nettie, from a similar fate, and while Nettie escapes to a new life as a missionary in Africa, Celie is left behind without her best friend and confidante, married off to an older suitor, and sentenced to a life alone with a harsh and brutal husband.���

As you can see from the bold text, we can learn a lot about who from this blurb. In only two sentences, we���ve found out Celie���s background, her early hopes and dreams, and the struggles she will have to overcome during the course of her story.

For nonfiction, the who is somewhat different. In memoir or biography, the who is the subject of the work, and they���re introduced in just a sentence or two. For works where the author is an expert, the blurb might instead begin with:

What?

A good example is in the blurb for the book The Coming Wave:

���Everything is about to change. Soon you will live surrounded by AIs. They will organise your life, operate your business, and run core government services. You will live in a world of DNA printers and quantum computers, engineered pathogens and autonomous weapons, robot assistants and abundant energy. None of us are prepared.

As co-founder of the pioneering AI company DeepMind, part of Google, Mustafa Suleyman has been at the centre of this revolution.���

We began with what ��� the issue that the book plans to explore. The blurb personalizes the subject, by using language like ���you��� and ���us.��� It then follows with a reason that the who ��� in this case, the author ��� is capable of explaining that topic to you. By contrast, the Nobel Prize-winning poetry book The Wild Iris gives you only a brief mention of who, followed by a what:

���From Pulitzer Prize-winning poet Louise Gl��ck, a stunningly beautiful collection of poems that encompasses the natural, human, and spiritual realms.���

Note the use of adjectives to encourage the reader to pick up this stunning, beautiful book? Whether you���re pitching fiction or nonfiction, don���t be afraid to talk up your work. If you���ve created a magical land, seductive characters, or compelling research, say so! Even if your reader picks your book up for free from the library, you are still trying to sell it to them. You are trying to sell your reader and all of their friends and family on this single, extraordinary concept: that it���s worthwhile for the reader to voluntarily give up time and effort ��� which they could spend on any other book, or anything else in the world, for that matter ��� to read what you have written. If you want to convince people to pick up your book, give them lots of good reasons to read it!

How?How is also a very useful question for nonfiction. Summarize the main points of your book, focusing on your thesis.

In fiction, use how to give a preview of your plot. Who/what + a few details about the story like any interesting side characters, the stakes, and your main character���s approach to problem-solving in the narrative = your how. Don���t overdo here. Think of your blurb like an overture to a musical, with your first pages as the opening number.

Where? and When?

Where and when both function to give your work boundaries. For these questions, let���s take a look at the first sentence of the blurb for Jeannie Lin���s Butterfly Swords:

���During China���s infamous Tang Dynasty, a time awash with luxury yet littered with deadly intrigues and fallen royalty, betrayed Princess Ai Li flees before her wedding.���

What you choose to leave out of your blurb is as important as what you choose to put in. Many people try to cram the entire summary of their book into the blurb. But that is not the point. A good blurb doesn���t spoil the whole story for you ��� it gives you only enough information to make you ask questions. Readers want to be surprised, to learn, to discover. Explain why they should follow you into the world of your book, give them the limits of where it will take them so they know they���re following a guided tour of that world, and tell them what���s so important about bothering with this particular book. Anything else is irrelevant.

And this brings us to the final question:

Why?Why should readers choose this book? For that, you will need to resolve your blurb with either a hook or a call to action.

The HookThis is a statement to grab readers��� attention. In fiction, it should come in one of two forms: a question directly to the reader, or an either/or statement. This important declaration lets readers know there is a way for the protagonist to win or lose, and either could happen by the end of the novel. Depending on your genre the stakes could be huge, such as saving the world or dooming it. Consider the blurb for The Amber Spyglass, by Philip Pullman:

���Throughout the worlds, the forces of both heaven and hell are mustering to take part in Lord Asriel’s audacious rebellion. Each player in this epic drama has a role to play���and a sacrifice to make. Witches, angels, spies, assassins, tempters, and pretenders, no one will remain unscathed.���

But the stakes could also be less catastrophic, though important to the protagonist: ���Will Beezus find the patience to handle her little sister before Ramona turns her big day into a complete disaster?��� (from Beverly Cleary���s Beezus and Ramona)

A Call to ActionA strong CTA instructs the reader to do something or perform an action. Sometimes it���s as simple as advising them to read your book.

Here���s a good example from Marie Kondo���s The Life-Changing Magic of Tidying Up: ���This international bestseller will help you clear your clutter and enjoy the unique magic of a tidy home ��� and the calm, motivated mindset it can inspire.��� This final sentence both encourages you to do something ��� clean up ��� and tells you about the rewards you will receive from doing so ��� enjoying your home and a calm mind.

So there you have it ��� the basics of how to build a perfectly structured blurb. Figure out the answers to the questions above and you���ll have all you need to craft a winning description that will attract readers��� attention, resolve the question ���Why this book?��� and pose new questions that the reader will want to dive right in to find the answers to.

Start working on your blurb now���because we have a new contest on October 19. TEN lucky winners will receive a blurb critique from guest editor Erica Converso!

Here’s an incredible worksheet that will help you build an eye-catching blurb! Ready Chapter 1 is celebrating the launch of their free Peer Critique forum and shared this to prepare people for their blurb contests (where you can win agent feedback). They generously allowed me to share this resource with you.

Here are a few additional helpful posts about writing blurbs.

Please let us know in the comments if you have any questions.

Back Cover Copy Formula (Writers Helping Writers Resident Writing Coach Sue Coletta)

Blurbs that Bore, Blurbs that Blare (Writers Helping Writers)

How to Write a Book Blurb (Fictionary)

How To Write Book Blurbs: 8 Tips for Selling By Summary (Now Novel)

This post contains affiliate links.

Erica Converso, author of the Five Stones Pentalogy, (affiliate link) loves chocolate, animals, anime, musicals, and lots and lots of books ��� though not necessarily in that order. In addition to her writing, she has also been a research and emerging technologies librarian. Check out Erica���s blog for free resources!

As an editor, she aims to improve and polish your work to a professional level, while also teaching you to hone your craft and learn from previous mistakes. With every piece she edits, she sees the author as both client and student. She believes every manuscript presents an opportunity to grow as a writer, and a good editor should teach you about your strengths and weaknesses so that you can return to your writing more confident in your skills. Visit her website astrioncreative.com for more information on her books and editing and coaching services.

The post How to Craft a Top-Notch Blurb appeared first on WRITERS HELPING WRITERS��.

October 9, 2023

Writing Flawed Characters Who Don’t Turn Readers Off

No one in the real world is perfect, and so characters shouldn’t be either. To seem as real as you or me, they should have flaws and strengths, and these sides of their personality should line up with who they are, how they were raised, and reflect the experiences they’ve had to date, good and bad.

While we develop our characters, however, we need to remember that flaws come with a tipping point. If we write someone with an overabundance of negative traits and behaviors that are a turnoff, the character will slide into unlikable territory. And yes, if the goal is to make a villain, antagonist, or other character loathsome, that’s fine–mission accomplished. But if we want readers to be on their side, too much surliness, negativity, secretiveness, or propensity for overblown reactions can cause a reader to disconnect.

Like a joke taken too far, it���s hard to claw an audience back once they’ve formed negative judgments, which is why we want to be careful and deliberate when showing our character’s negative side. Antiheroes tend to wear flaws more openly and can be semi-antagonistic as they battle the world’s constraints, so this line of likability is something to pay close attention to if we want readers to ultimately side with them. Here are some tips to help you.

How to Write Flawed Characters& Not Turn Readers Off

Show A Glimmer: no matter how impatient, uptight, or spoiled your character is, hint there���s more beneath the surface. A small action or internal observation can show the character in a positive light, especially when delivered in their first scene (frequently referred to as a Save the Cat moment.) It can be a positive quality, like a sense of humor, or a simple act that shows something redeeming about the character.

Imagine a man yelling at the old ladies crowding the hallway outside his apartment door as they pick up their friend Mabel for bingo, and then seeing him swear and fume at the chuggy elevator for making him late. Not the nicest guy, is he? But when Mr. Suit and Tie gets to his car outside, he stops to dig out a Ziploc bag of cat food and carefully roll down the edges into a makeshift bowl.

What? Here the guy seemed like an impatient jerk, but we discover part of his morning routine is to feed the local stray cat! Maybe he isn���t so bad after all. (Talk about a literal interpretation of ���saving the cat.���)

Use POV Narrative for Insight: characters are flawed for a reason, namely negative experiences (wounds) which create flaws as an ���emotional countermeasure.��� Imagine a hero who stutters, and he was teased about it growing up. Even his parents encouraged him to ���be seen and not heard��� when they hosted parties and special events. Because of the emotional trauma (shame and anger) at being treated badly, he���s now uncommunicative and unfriendly as an adult. This type of backstory can be dribbled into narrative with care, as long as it���s active, has bearing on the current action, and is brief as to not slow the pace.

Create Big Obstacles: the goal is to create empathy as soon as possible, and one of the ways to do that is to show what the character is up against. If your character has a rough road ahead, the reader will make allowances for behavior, provide they don’t wallow and whine overmuch. After all, it isn���t hardship that creates empathy…it���s how a character behaves despite their hardship as that gives readers a window into who they really are.

Trait Boxed Set (eBook, PDF)

Trait Boxed Set (eBook, PDF)Form a Balance: No character is all good or all bad. Give them a mix of positive traits (attributes) and negative traits (flaws) so they feel realistic, and ensure their negative traits contain a learning curve. For example, their negative traits may be good at keeping people and uncomfortable situations at a distance in the past, but in your story, they won’t help your character get what they want. Your character will have to see this for themselves, and it’ll only happen when that flawed behavior and way of thinking leads to poor judgment, mistakes, relationship friction, and other problems, the poor sap.

Eventually the character will see that they need to change up their behavioral playlist if they want to succeed, and this means letting go of the bad and embracing the good, opening their mind to a new way of thinking, behaving, and being. This is where their positives get to shine, so lay the foundation with qualities that may start in the background, but come forward and show them to be rounded, likable, and unique.

Of Special Concern:

Of Special Concern:Your Story’s Baddies

It���s easy to give an antagonist flaws because your intent is to make readers dislike them, but even here, caution is needed. Hopelessly flawed antagonists make shallow characters and unworthy opponents, so we want to also give them strengths (like intelligence, meticulousness, dedication, and discipline, for example) to make them formidable and hard to beat.

This forces your protagonist to work their hardest, and in a match up, nothing is guaranteed. Being uncertain about the outcome of these story moments is what will hold the reader’s attention to the very end.

To build balanced, unique characters and find traits, positive and negative, that will make sense for them, take a look at the Positive Trait & Negative Trait Thesaurus Writing Guides. We created these to make character building easier for you.

Happy writing!

The post Writing Flawed Characters Who Don’t Turn Readers Off appeared first on WRITERS HELPING WRITERS��.

October 7, 2023

How to Create Mood Effectively in Your Fiction

By C. S. Lakin

Every person or character, at any given time, is in a particular mood. Generally, mood is a person���s state of mind, but it���s more than that. Mood can also describe the disposition of a collective of people, a certain time in history, or the ether of a place.

Regardless of what kind of mood we speak of, it���s always subjective. Ten people can be experiencing the same event at the same place and time, yet, depending on their perspective, their individual mood will differ.

We all know about moods and have a range of them we express and feel, whether we���re aware of them or not. We can sense others��� moods just as they can sense ours. The mood of the character should affect the way he perceives his environment, and expert writers will carefully choose words and imagery that act like a mirror to their emotions.

First, Consider Your Scene���s PurposeYour story may have an overall tone or mood, but every scene is a microsystem of mood that depends on the emotional state and mindset of your character. When you plot out your scene, you need to first think about how your character will interact with his setting based on his mood and the purpose of your scene.

Remember: it���s the purpose of the scene that determines all the setting elements���what you choose to have him notice (and not notice) and react to and why.

Words Are EverythingHowever, learn this truth: it is not the originality of a world or the degree of creativity in the world itself that makes a fantasy novel shine with brilliance; it���s the choice of words and phrases that the author uses that evokes not just a right sensory experience but makes readers fall in love with the writing.

Please note: this doesn���t just pertain to fantasy novels. Every novel involves the creation of a ���world,��� and so writers need to take just as much care in the creation of any world in any genre. Take a look at this hastily written sentence:

Bill walked through the forest until he found a cottage set back in the trees . . .

Now consider the reworked description below that I spent a bit more time on:

Bill slogged along the leaf-choked path, the spindly arms of the bare maples quivering in the cold autumn wind���a feeble attempt to turn him back. But he pressed on until he spotted, nestled in a copse of willows, the derelict cottage slumped like a lost orphan, the lidless windows dark and vacant. Hardly a welcoming sight after many tiresome hours of travel.

A specific mood is created by bringing out Bill���s mindset and emotional state. Without knowing anything else about this scene (if I���d written one), a reader can clearly sense the purpose of the action by the things he notices and the words used to describe them

To immerse your readers in the world you���ve created, you need to spend time coming up with masterful description. And the components of such description are the nouns, verbs, and adjectives you choose.

Mood NuancesWe all know about moods and have a range of them we express and feel, whether we���re aware of them or not. We can sense others��� moods just as they can sense ours. The mood of the character should affect the way he perceives his environment, and expert writers will carefully choose words and imagery that act like a mirror to their emotions. It���s a reciprocal factor: mood informs how the character sees his setting, but the setting also informs his mood���shifting it or intensifying it.

Take a look at this passage from The Dazzling Truth (Helen Cullen):

Murtagh opened the front door and flinched at a swarm of spitting raindrops. The blistering wind mocked the threadbare cotton of his pajamas. He bent his head into the onslaught and pushed forward, dragging the heavy scarlet door behind him. The brass knocker clanged against the wood; he flinched, hoping it had not woken the children. Shivering, he picked a route in his slippers around the muddy puddles spreading across the cobblestoned pathway. Leaning over the wrought-iron gate that separated their own familial island from the winding lane of the island proper, he scanned the dark horizon for a glimpse of Maeve in the faraway glow of a streetlamp.

In the distance, the sea and sky had melted into one anthracite mist, each indiscernible from the other. Sheep huddled together for comfort in Peadar ��g���s field, the waterlogged green that bordered the Moones��� land to the right; the plaintive baying of the animals sounded mournful. Murtagh nodded at them.

There was no sight of Maeve.

Culler is masterful in her usage of imagery to convey sensory detail. The feeling of rain on Murtagh���s skin is described by flinching at spitting raindrops. The blistering wind attacks his pajamas. Dragging the heavy door shows the sensation of his muscles working���proprioception. And of course we have visuals, which paint the stage for us.

We also have the sound of the brass knocker���used for a specific purpose���to tell us he���s concerned about the children waking. This is a good point to pay attention to: sensory detail should serve more than one purpose. Don���t just add a sound or sight without thinking of the POV character���s mood, concerns, mindset, and purpose in that moment. The more you can tie those things to the sensory details, the more powerful your writing.

Weather

Writers are sometimes told not to write about weather. It���s boring, right? But weather affects us every moment of every day and night. We make decisions for how we will spend our day, even our life, based on weather. And weather greatly affects our mood, whether we notice or not.

Since we want our characters to act and react believably, they should also be affected by weather. Sure, at times they aren���t going to notice it. But there are plenty of opportunities to have characters interact with weather can be purposeful and powerful in your story.

Strong Verbs and AdjectivesUsing strong and effective verbs and adjectives will help you craft setting descriptions that are masterful. Every word counts. To borrow unfaithfully from Animal Farm: All words are created equal, but some words are more equal than others. Some words are plain boring, and others take our breath away.

Mood is one of the 3 M���s of character setup, and you���ll want to make sure you get the character���s mood, mindset (what she���s concerned about), and motivation on that first page. What happens in the scene will shift the mood in some way, resulting in some change in mood by the end of the scene. So think about what that mood will be like at the start of the scene and what���s changed in the mood by the end. Using the setting interactively with your character is the most powerful way to masterfully accomplish this!

C. S. Lakin is an award-winning author of more than 30 books, fiction and nonfiction (which includes more than 10 books in her Writer���s Toolbox series). Her online video courses at Writing for Life Workshops have helped more than 5,000 fiction writers improve their craft. To go deep into creating great settings and evoking emotions in your characters, and to learn essential technique, enroll in Lakin���s courses Crafting Powerful Settings and Emotional Mastery for Fiction Writers. Her blog Live Write Thrive has more than 1 million words of instruction for writers, so hop on over and level-up your writing!

The post How to Create Mood Effectively in Your Fiction appeared first on WRITERS HELPING WRITERS��.

October 4, 2023

Want to Show Your Character’s Pain? Here’s Everything You Need to Know

For the better part of two months, Becca and I have been exploring pain, and how to write about it in fiction. It’s been enlightening for us, and we hope for you as well. So many ways to torture characters, who knew?

(Well, we did. And you did. Pain is sort of our bread and butter, isn’t it?)

But maybe you missed a post or two. It happens. You were on a writing retreat, or vacationing at the lake. Maybe you were hiding out in a sleeping bag in the woods, denying the arrival of fall and Pumpkin Spice Lattes.

Whatever the case may be, we’ve got you. Here are all the posts in this series. The Three Stages of Awareness

The Three Stages of AwarenessPain has 3 stages: Before, During, and After. For realistic and logical description, you’ll want to know what all three will look like for your character and the type of injury.

Different Types of Pain to Explore

Different Types of Pain to ExploreDiscomfort comes in all shapes and sizes, including physical, psychological, and spiritual pain. Mine this post for ideas on how to bring something fresh to your story by targeting a variety of soft spots.

Describing Minor Injuries

Describing Minor InjuriesCuts, stings, and scrapes create discomfort and can easily lead to bigger problems. You’ll find loads of descriptive detail for showing smaller injuries here, and how they can make your story more realistic.

Describing Major or Mortal Injuries

Describing Major or Mortal InjuriesSometimes a wound is serious, casting doubt on whether your character will survive this crisis. Fill your mental toolbox with ideas on what happens when your character is stricken with an injury with no easy fix.

Describing Invisible Injuries and Conditions

Describing Invisible Injuries and ConditionsNot every injury leaves a physical mark, and when you can’t see it, you don’t know how bad it is. Invisible injuries and conditions are a great vehicle to encourage readers to worry about characters they care about.

Factors that Help or Hinder One’s Ability to Cope

Factors that Help or Hinder One’s Ability to CopeWe all hope we’ll cope well when injured, but certain factors make it easier–or harder–to handle pain. This list will help you steer how a character responds!

Taking an Injury from Bad to Worse

Taking an Injury from Bad to WorseNo one likes to get hurt, but when circumstances are afoot that cause that injury to worsen? Tension and conflict, baby. So, when you’re feeling evil, read this one to see how you can raise the stakes.

Everyday Ways a Character Can Get Hurt

Everyday Ways a Character Can Get HurtWe want to immerse readers in the character’s everyday world, so it helps to think about where dangers and threats might be lurking so we can create a credible collision with pain that comes from a believable source.

Best Practices for Writing Pain in Fiction

Best Practices for Writing Pain in Fiction

Finally, we round up this series with unmissable tips on how to take pain scenes from good, to great. Authenticity is key, and of course, showing and not telling. Don’t miss these final tips to help you write tense, engaging fiction!

We hope this series on pain helps you level up your stories.

Pain is an Emotion Amplifier, and a powerful one at that, so putting in extra effort to showcase it well is worth the time.

Pain presents a challenge for your character while making them more emotionally volatile, and prone to mistakes. This means tension and conflict, drawing readers in!

Pain also helps empathy for because people know pain, and so when a character they care about is battered and bruised, or beset by trauma, readers can’t help but be reminded of their own experiences, and worry over what will happens next.

Before you go…

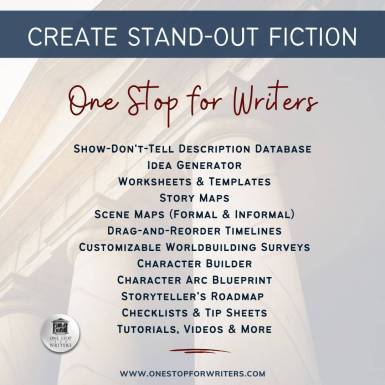

Don’t forget, its birthday week here at Writers Helping Writers as our sister site, One Stop for Writers is turning 8!

We’ve rustled up a nice 25% discount on all subscriptions, so if you want to add some serious thunder to your writer’s toolkit, check out the arsenal of writing tools you get with a OSFW subscription, including the Storyteller’s Roadmap that guides you as you plan, write, and revise.

Happy writing!

The post Want to Show Your Character’s Pain? Here’s Everything You Need to Know appeared first on WRITERS HELPING WRITERS��.

October 3, 2023

Happy 8th Birthday, One Stop for Writers!

Let the good times roll…

One Stop for Writers‘ BIRTHDAY WEEK is here!

It’s hard to believe that Becca and I have been helping writers grow into confident storytellers at One Stop for Writers for EIGHT YEARS now. That’s eight years of supporting writers plan, write, and deliver their books into the hands of excited readers. Eight years of watching creatives all over the world go from pre-published to published. What an incredible ride–thank you so much for letting us join your journey!

Save 25% On All One Stop for Writers PlansEight years is worth celebrating, so here’s a sweet birthday discount for anyone wanting a war chest of storytelling tools to support them as they plan, write, and revise:

EIGHTYEARS

And heck, with NaNoWriMo on the way, you can use October to build your characters, plot their journey, and create the framework of your story’s world.

To use this code:

Sign up or sign in. Choose any paid subscription (1-month, 6-month, or 12-months) and add this code: EIGHTYEARS to the coupon box.Once activated, this one-time 25% discount will apply onscreen.Add your payment method, check the Terms box, and then hit the subscribe button.

And that’s it! All of One Stop for Writers’ resources, including the incredible descriptive THESAURUS, are now part of your storyteller’s toolkit.

Anyone can use this code – new subscribers and existing subscribers!

If you are a current subscriber, go to your My Subscription page (ACCOUNT tab). Click the button under the Coupons and Gift Certificates area and add the code. You’ll see a message when it has been added, and it will automatically apply to your next invoice. Code is active until October 20th, 2023.

New to One Stop?If you’re not familiar with One Stop for Writers, join Becca for a virtual tour. She’ll show you exactly how this site is going to help you write stronger fiction faster:

.ose-uid-2dd46a760741e3e5d65d4f4092be48d6 { width: 600px !important; height: 340px; max-width: 100%; } .ose-uid-2dd46a760741e3e5d65d4f4092be48d6>iframe { height: 340px !important; max-height: 340px !important; width: 100%; } .ose-uid-2dd46a760741e3e5d65d4f4092be48d6 .wistia_embed { max-width: 100%; } .alignright .ose-wistia.ose-uid-2dd46a760741e3e5d65d4f4092be48d6{ margin-left: auto; } .alignleft .ose-wistia.ose-uid-2dd46a760741e3e5d65d4f4092be48d6{ margin-right: auto; } .aligncenter .ose-wistia.ose-uid-2dd46a760741e3e5d65d4f4092be48d6{ margin: auto; } .ose-uid-2dd46a760741e3e5d65d4f4092be48d6 img.watermark{ display: none; } Planning your NaNoWriMo Novel?

If you’re gearing up for NaNoWriMo (National Novel Writing Month) now’s a great time to start building your characters, plotting your story, and creating your world. The Storyteller’s Roadmap will guide you step-by-step to the tools and resources you need.

Once November hits, you’ll love having non-stop ideas on what to write using our Show-Don’t-Tell Database, too. Thanks for helping us celebrate our birthday, and happy writing!

The post Happy 8th Birthday, One Stop for Writers! appeared first on WRITERS HELPING WRITERS��.

September 30, 2023

Meet Our Resident Writing Coaches

I love being the Writers Helping Writers Blog Wizard���and am honored to work closely with the Resident Writing Coaches. They���re all talented, generous authors who share their wisdom to help take your writing to the next level. I’ve learned so much from them, and have a feeling you have, too!

This is the 8th year of our popular Resident Writing Coach program where we feature writing experts through a series of four blog posts scattered throughout the year. We bring in a mix of expertise, so you benefit from different voices and perspectives from all over the world.

Each year we have some new coaches and some returning, so let me first say goodbye to the wonderful Christina Delay. We greatly appreciate all you have shared with us, Christina.

I���m excited to welcome back a wonderful Resident Writing Coach who is returning after a year off! Please give a warm welcome to���

September C. Fawkes is a freelance editor, writing instructor, and award-winning writing tip blogger. She has edited for both award-winning and best-selling authors as well as beginning writers. Previously, she worked as an assistant to a New York Times bestselling author.

She is best known for her blog, which won the Writer���s Digest 101 Best Websites for Writers Award and Query Letter���s Top Writing Blog Award, and has over 500 writing tips. She also offers a live online writing course, ���The Triarchy Method,��� where she personally guides 10 students through developing their best books by focusing on the ���bones��� of story.

To learn more about her course, read her tips, or inquire about her editing services, visit SeptemberCFawkes.com. Grab her AMAZING free guide on Crafting Powerful Protagonists while there. You can also find her on Facebook, X, Instagram, and Tumblr.

You can find September���s posts here.

In addition to our new coach, we���re thrilled to have these returning masterminds���

Lucy V. Hay is a script editor, author and blogger who helps writers. She���s been the script editor and advisor on numerous UK features and shorts & has also been a script reader for 20 years, providing coverage for indie prodcos, investors, screen agencies, producers, directors and individual writers. She���s also an author, publishing as both LV Hay and Lizzie Fry. Lizzie���s latest, a serial killer thriller titled The Good Mother is out now with Joffe Books, with her sixth thriller out in 2024. Lucy���s site at www.bang2write.com has appeared in Top 100 round-ups for Writer���s Digest & The Write Life, as well as a UK Blog Awards Finalist and Feedspot���s #1 Screenwriting blog in the UK (ninth in the world.). She is also the author of the bestselling non-fiction book, Writing & Selling Thriller Screenplays: From TV Pilot To Feature Film (Creative Essentials), which she updated for the streaming age for its tenth anniversary in 2023.

You can find Lucy���s posts here.

Marissa Graff has been a freelance editor and reader for literary agent Sarah Davies at Greenhouse Literary Agency for over five years. In conjunction with Angelella Editorial, she offers developmental editing, author coaching, and more. She specializes in middle-grade and young-adult fiction but also works with adult fiction.

Marissa feels if she���s done her job well, a client should probably never need her help again because she���s given them a crash-course MFA via deep editorial support and/or coaching. Connect with Marissa on her Website, Twitter, Instagram, and Facebook.

You can find Marissa���s posts here.

Colleen M. Story is a novelist, freelance writer, writing coach, and speaker with over 20 years in the creative writing industry. Her newest novel, The Curse of King Midas, is forthcoming in 2024, and has already been recognized as a top-ten finalist for the Claymore Award. Her novel The Beached Ones came out in 2022 with CamCat Books, while Loreena���s Gift, was a Foreword Reviews��� INDIES Book of the Year Awards winner, among others.

Colleen has written three books to help writers succeed. Your Writing Matters is the most recent, and was a bronze medal winner in the Reader Views Literary Awards (2022). Writer Get Noticed! was a gold-medal winner in the Reader���s Favorite Book Awards and a first-place winner in the Reader Views Literary Awards (2019). Overwhelmed Writer Rescue was named Book by Book Publicity���s Best Writing/Publishing Book in 2018. You can find free chapters of these books here.

Colleen offers personalized coaching plans tailored to meet your needs. If you���d like to work on-one-one with an experienced writing coach, check out her flexible and affordable options.

Colleen frequently serves as a workshop leader and motivational speaker, where she helps attendees remove mental and emotional blocks and tap into their unique creative powers. Find her at Writing and Wellness, Author Website, YouTube, Twitter, LinkedIn, Goodreads, BookBub and Instagram.

You can find Colleen���s posts here.

Jami Gold, after muttering writing advice in tongues, decided to become a writer and put her talent for making up stuff to good use, such as by winning the 2015 National Readers��� Choice Award in Paranormal Romance for her novel Ironclad Devotion.

To help others reach their creative potential as well, she���s developed a massive collection of resources for writers. Explore her site to find worksheets���including the popular Romance Beat Sheet with 80,000+ downloads���workshops, and over 1000 posts on her blog about the craft, business, and life of writing. Her site has been named one of the 101 Best Websites for Writers by Writer���s Digest.

Find Jami at her website, Twitter, Facebook, Goodreads, BookBub, and Instagram.

You can find Jami���s posts here.

Lisa Poisso works with new and emerging querying and self-publishing writers. A classically trained dancer, her approach to writing is likewise grounded in structure, form, and technique as doorways to freedom of movement on the page. She���s an energetic proponent of one-on-one feedback to accelerate the learning curve of writing fiction. Her Accelerator coaching fast-tracks authors through structure and technique while nurturing the potential of their early drafts.

Lisa is a degreed journalist and a veteran of decades of award-winning work in magazine editing and journalism, content writing, and corporate communications. Her coaching and editorial studio is staffed by an industrious team of #45mphcouchpotato greyhounds. Visit her Linktree for help with your early steps as a writer, join the Clarity for Writers community at Substack, and download a free Manuscript Prep guide. Connect with Lisa at LisaPoisso.com and on Instagram, Facebook, and X/Twitter.

You can find Lisa���s posts here.

Sue Coletta is an award-winning crime writer and an active member of Mystery Writers of America, Sisters in Crime, and International Thriller Writers. Feedspot and Expertido.org named her Murder Blog as ���Best 100 Crime Blogs on the Net.��� She also blogs at the Kill Zone (Writer���s Digest ���101 Best Websites for Writers���) and Writers Helping Writers. Sue lives with her husband in the Lakes Region of New Hampshire. Her backlist includes psychological thrillers, the Mayhem Series (books 1-3) and Grafton County Series, and true crime/narrative nonfiction. Now, she exclusively writes eco-thrillers, Mayhem Series (books 4-7 and continuing). Sue���s appeared on the Emmy award-winning true crime series, Storm of Suspicion, and three episodes of A Time to Kill on Investigation Discovery. Learn more about Sue and her books at www.suecoletta.com.

Find Sue on her Website, Facebook, Twitter, Amazon, Goodreads, BookBub, Instagram, and YouTube.

You can find Sue���s posts here.

Suzy Vadori is the award-winning author of The Fountain Series and is represented by Naomi Davis of Bookends Literary Agency. She is a certified Book Coach with Author Accelerator and the founder of the Wicked Good Fiction Bootcamp. Suzy breaks down concepts in writing into practical steps, so that writers with big dreams can get the story exploding in their minds onto their pages in a way that readers will LOVE.

In addition to her online courses, Suzy offers 1:1 Developmental Editing and Book Coaching services, and gives practical tips for writers at all stages on her vlog.

Find Suzy on her website, YouTube, Facebook, Free Inspired Writing Facebook Group, Instagram, and Tiktok.

You can find Suzy���s posts here.

Michelle Barker is an award-winning author, editor, and writing teacher who lives in Vancouver, BC. Her newest book, coauthored with David Griffin Brown, is Immersion and Emotion: The Two Pillars of Storytelling. Her novel My Long List of Impossible Things, came out in 2020 with Annick Press. She is the author of The House of One Thousand Eyes, which was named a Kirkus Best Book of the Year and won numerous awards including the Amy Mathers Teen Book Award. She���s also the author of the historical picture book, A Year of Borrowed Men, as well as the fantasy novel, The Beggar King, and a chapbook, Old Growth, Clear-Cut: Poems of Haida Gwaii. Her fiction, non-fiction and poetry have appeared in literary reviews around the world.

Michelle holds an MFA in creative writing from UBC and has been a senior editor at The Darling Axe since its inception. She loves working closely with writers to hone their manuscripts and discuss the craft. You can find Michelle on Twitter and GoodReads.

You can find Michelle���s posts here.

TipsIf you want to browse past Resident Writing Coach posts, click here.

Love a post? Click on the name up top to see all the posts from that person.

Check out all the Resident Writing Coach bios! You���ll find:

Editing and coaching servicesFree support through online groupsHelpful resourcesDon���t forget to follow them on social media for even more tips and updates!

Here���s to another year of amazing posts. Please give a warm welcome our Resident Writing Coaches.

Pssst���when you comment on their posts, they reply to you! So please share your thoughts and ask questions throughout the year. Angela, Becca and I love working with the coaches. They���re an incredible asset to the Writers Helping Writers blog.

If there���s a topic you���d like help with, please add it in the comments so hopefully one of our Resident Writing Coaches will post about it.The post Meet Our Resident Writing Coaches appeared first on WRITERS HELPING WRITERS��.

September 28, 2023

Writing About Pain: Best Practices for Great Fiction

Are you enjoying this series on writing your character���s pain? That���s a weird and slightly sadistic statement���even more so when we say how much we���ve enjoyed writing about pain. But it’s one of those things your character IS going to encounter; it���s not a matter of if, but when (and how often). So we need to be able to write it well.

We���ve covered a lot of ground, from the 3 stages of awareness to the symptoms of minor, mortal, and invisible injuries. But regardless of the kind of pain your character is feeling, there are certain practices that will enhance your descriptions of it to maximize reader empathy and minimize their chances of being pulled out of the story.

Show Don���t TellThis one comes first, because if you want to create evocative and compelling descriptions, showing is the way to do it. Take this passage, for example:

Pain throbbed in my wrist. It radiated into my fingers. Tears sprang to my eyes.

On the surface, this description gets the job done because it adequately describes the character���s pain. But it���s not engaging. Lists seldom are���yet this is how pain is often described, as a series of symptoms or sensations. This isn���t how real pain registers, so it being described this way won���t read as authentic to readers.

Don���t stop the story to talk about what the character���s feeling. Instead, incorporate it into what���s happening. This keeps the pace moving and readers reading:

Cradling my throbbing wrist, I searched for the rope and loosed it from my belt. I drew a shuddering breath of relief to discover my fingers still worked, though the pain had me biting nearly through my lip.

This description is much better because it reveals the pain in bits and bobs as the character is going about her business. It uses words that describe the intensity and quality of the pain: throbbing and shuddering. There���s also a thought included, which is important because when agony strikes, our brains don���t stop working. The opposite is actually true, with our thoughts often going into overdrive. So including a thought that references the character���s mental state or physical discomfort is another way to show their pain to readers in an organic way.

Take Personal Factors into AccountThe character���s pain level and intensity will depend on a number of factors, such as their pain tolerance, their personality, and what else is going on in the moment. Being aware of these details and knowing what they look like for your character is key for tailoring a response that is authentic for them. For more information on the factors that will determine your character���s pain response and their ability to cope with their discomfort, see the 6th post in this series.

Adhere to Your Chosen Point of ViewWhether you���re telling your story in first person, third person, or omniscient viewpoint, consistency is a must, so you���ve got to stick to that point of view. If the person in pain is the one narrating, you can go deep into their perspective to show readers what���s happening inside���the pain, yes, but also the nausea, tense muscles, and the spots that appear in the character���s vision as they start to black out.

But if the victim isn���t a viewpoint character���if the reader isn���t privy to what���s happening inside their heads and bodies���you���ll need be true to that choice. Stick with external indicators that are visible to others, such as the character wincing, the hissed intake of breath through clenched teeth, the weeping of blood, or the skin going white and clammy.

Consider the Intensity of the Pain

All pain isn���t created equal, and the intensity of the pain being described will often determine the level of detail. Excruciating, agonizing pain is going to be impossible for the character to ignore; because of their focus on their own pain, more description is often necessary. On the flip side, a lot of words aren���t needed to express the mild, fleeting pain of a stubbed toe or bruised knee. The severity of the pain can guide you toward the right amount of description.

Don���t Forget about ItRemember that pain has a life of its own. Some injuries heal fast, with the pain receding quickly and steadily. Others linger. Many times, healing is a one-step-forward-two-steps-back situation, with things seeming to improve, then a relapse or reinjury causing a setback. And then there���s chronic pain, which never fully goes away.

The nature of the injury will dictate how often you return to the character���s pain and remind readers of it. Minor injuries can fade into the background without further mention. But moderate and severe hurts will take time to heal. This means your character will be feeling the pain well after it began, and you���ll have to mention it again. But when you do, the quality and intensity will be less, and your description will follow suit.

Be RealisticIn serious cases, your character���s pain will become limiting; they won���t be able to do the things they could when they were unscathed. But we see unrealistic practices surrounding pain and wounds all the time in fiction. The hero���s shoulder is dislocated, he knocks it gamely back in place, then goes running after the villain. Maybe he���s grimacing and grunting, but two pages later, he���s duking it out without any mention of the injury or the pain that activity would cause.

Don���t let pain unintentionally turn your hero into a superhero. Keep them real and relatable, which is easy to do with some basic planning. If you know they���re going to be injured in a scene, ask yourself: what physical activity will be happening afterward? Then plan accordingly.

Maybe you tailor their injury so it puts them in distress but allows them to do what they need to do. Or, if a severe injury is necessary, you might rearrange your scenes so the character is able to heal up before encountering any serious physical activity. Another option is to let them tackle the active moment following a painful incident, but show their limitations. Show them struggling and having to compensate. The important thing is to keep their physical abilities in the wake of an injury realistic so readers don���t call Bullcrap and start thinking about what���s wrong with the story.

The Complete Pain SeriesAnd with that, this series is a wrap. Hopefully these posts have provided some solid information and practical advice on how to write your character���s pain effectively. In case you missed any of the installments, I���ve listed them here, for easy reference.

The Three Stages of Awareness

Different Types to Explore

Describing Minor Injuries

Describing Major and Mortal Injuries

Invisible Injuries and Conditions

Factors that Help or Hinder the Ability to Cope

Taking an Injury from Bad to Worse

Everyday Ways a Character Could Be Hurt

The post Writing About Pain: Best Practices for Great Fiction appeared first on WRITERS HELPING WRITERS��.

September 26, 2023

Writing About Pain: Everyday Ways A Character Could Be Hurt

We���ve covered many aspects of pain so far in this experience, such as the different categories of pain and how to write the discomfort associated with minor, major, and invisible injuries. All of this is helpful for identifying the pain your character will be feeling and helping you write it accurately. But how will your character sustain their injury?

If you���ve determined that pain is in your character���s future, you���ve got to then figure out how it will happen. The good news is that this can often be done organically through whatever they’re already doing. It���s just a matter of knowing which activities they���d be involved in and the locations they���re likely to visit. Get them there, and let the mishaps unfold.

Here are a few of the common causes for injuries and places where harm could naturally befall your character.

Household AccidentsIt���s commonly known that many injuries occur in and around the home. This means your character���s living space can become a minefield of potential hazards. Moving heavy furniture, slipping in the shower or on slick floors, falling down stairs, cutting oneself while cooking, choking on food, fingers getting smashed in a drawer, getting zapped by a faulty electrical outlet���the possibilities, both serious and slight, are endless.

This is also true of incidents happening just outside the home. Your character could be injured while using faulty lawn equipment (or misusing perfectly good tools), tripping over uneven driveway pavers, being exposed to poison ivy, breathing noxious fumes from a DIY painting project, getting a splinter, or falling out of a tree.

Sometimes, the easiest solutions are the best ones. When it comes to injuries, there really is no place like home.

Workplace InjuriesThe other place your character spends a lot of their time is at work, making it a logical place for bad things to happen. If your story calls for a certain kind of injury, consider a career for the character where it���s most likely to happen. Maybe a more dangerous occupation is in order, such as construction work, being a police officer, or working as an EMT in a hazardous area.

But even mundane office jobs can provide opportunities for a range of injuries���paper cuts, carpal tunnel, slips and falls, and back and neck pain from staring at a screen for hours, to name just a few. As a matter of fact, a physically painful event at work can spice up a boring day on the job. Just make sure it���s a natural fit so it doesn���t read as contrived.

Recreational ActivitiesWhat does your character do in their spare time? Could it be something that would incorporate the injury you need them to sustain? Maybe they���re an exercise enthusiast and enjoy running marathons, lifting weights, or some other way of pushing their body to its limits. Or they could be into extreme sports, like motocross, rock climbing, cave diving, or hang gliding. Even run-of-the-mill activities like hiking, jogging, fishing, hunting, and playing pickleball can end painfully given the right (or wrong) circumstances.

Transportation AccidentsWhen your character leaves home, some form of transportation is going to get them to their destination. Whether they���re in an isolated area or are surrounded by other people who are also getting from here to there, there are many opportunities for harm to befall them. Car accidents, falling off a bike, suffering a heart attack while riding the city bus, being hit while walking as a pedestrian, difficulties driving in other countries where the traffic laws are unfamiliar���so many possibilities.

Weather EventsWherever your character lives, they���re going to encounter different kinds of weather that can impact their safety. Slippery roads and icy streets can make accidents and falls more likely. Heavy fog, rain, and snow will decrease visibility. High winds can cause tree limbs to fall, crushing buildings or blocking roadways and causing hazards. And then you have extreme weather���tornadoes, earthquakes, hurricanes, lightning strikes, and hailstorms. The latter are much more dramatic, so you���ll have to lay that groundwork carefully. Make sure your character is living in an area where these threats are real. And use enough foreshadowing to inform readers of the danger so when it happens, it rings true.

Animal InjuriesAs much as we love our pets, they can inadvertently be a source of pain. For instance, we know how dangerous it is when an elderly person falls and breaks a hip. What you may not know is that one of the main reasons the elderly fall is because they���ve tripped over a pet. Sustaining an injury while walking the dog is also common, along with the garden-variety scratches, nips, and bites that may occur. It���s also easy to be hurt while trying to help a wounded or scared pet.

But domesticated animals aren���t the only ones your character needs to be careful with. Consider the altercations they might have with animals of the wilder sort: insect stings, snake and spider bites, or being bitten by a tick and incurring the chronic effects of Lyme disease. Is your character the reckless sort that might try to hand-feed a raccoon in the backyard or get a selfie with a bison at Yellowstone? They���re likely to get more than they bargained for.

Physical ViolenceSometimes harm occurs from other human beings, and it���s not always intentional. Being bumped on the street, elbowed in the mouth, knocked down in a crowd, slammed in a concert mosh pit, roughhousing with the kids���there are many ways someone could accidentally injure your character. And then there are deliberate acts of violence in the form of an attack, mugging, bullying, or domestic abuse.

This is a short list, really, of the ordinary ways your character could be injured just going about their day. It���s definitely not exhaustive but hopefully provides some ideas for how you can naturally incorporate the painful events your story needs in ways that are natural and seamless.

And if you need help in this area, consider adding an Emotion Amplifier into the mix. Your character may be a good driver, but what if they���re distracted or inebriated? They might be the most careful person on the worksite until they get dehydrated or are sick with a fever. And consider how added stress can make your character less patient, more reckless, and prone to making poor decisions. Amplifiers are a great way to turn a normal scenario into one where an injury is more likely to happen, so keep those in mind when you need to hurt your character.

Other Posts in This Pain Series:

The Three Stages of Awareness

Different Types to Explore

Describing Minor Injuries

Describing Major and Moral Injuries

Invisible Injuries and Conditions

Factors that Help or Hinder the Ability to Cope

Taking an Injury from Bad to Worse

The post Writing About Pain: Everyday Ways A Character Could Be Hurt appeared first on WRITERS HELPING WRITERS��.

September 23, 2023

Character Type & Trope Thesaurus: Whiskey Priest

In 1959, Carl Jung first popularized the idea of archetypes���”universal images that have existed since the remotest times.” He posited that every person is a blend of these 12 basic personalities. Ever since then, authors have been applying this idea to fictional characters, combining the different archetypes to come up with interesting new versions. The result is a sizable pool of character tropes that we see from one story to another.

Archetypes and tropes are popular storytelling elements because of their familiarity. Upon seeing them, readers know immediately who they’re dealing with and what role the nerd, dark lord, femme fatale, or monster hunter will play. As authors, we need to recognize the commonalities for each trope so we can write them in a recognizable way and create a rudimentary sketch for any character we want to create.

But when it comes to characters, no one wants just a sketch; we want a vibrant and striking cast full of color, depth, and contrast. Diving deeper into character creation is especially important when starting with tropes because the blessing of their familiarity is also a curse; without differentiation, the characters begin to look the same from story to story.

But no more. The Character Type and Trope Thesaurus allows you to outline the foundational elements of each trope while also exploring how to individualize them. In this way, you’ll be able to use historically tried-and-true character types to create a cast for your story that is anything but traditional.

Whiskey Priest

Whiskey PriestDESCRIPTION: A well-meaning priest, pastor, or other religious professional who exhibits moral weakness through a particular vice. Though he is acutely aware of his personal flaws, he continues to carry out his sacramental duties and takes his responsibility toward his charges seriously.

FICTIONAL EXAMPLES: Reverend Arthur Dimmesdale (The Scarlet Letter), Father Donald Callahan (Salem’s Lot, The Dark Tower), Friar Tuck (Robin Hood: Prince of Thieves), Imperius (Ladyhawke)

COMMON STRENGTHS: Cautious, Centered, Cooperative, Courteous, Diplomatic, Discreet, Empathetic, Generous, Gentle, Kind, Nurturing, Observant, Passionate, Patient, Persuasive, Private, Protective, Responsible, Spiritual, Supportive, Wise

COMMON WEAKNESSES: Addictive, Compulsive, Cowardly, Evasive, Humorless, Hypocritical, Insecure, Nosy, Self-Indulgent, Weak-Willed, Withdrawn

ASSOCIATED ACTIONS, BEHAVIORS, AND TENDENCIES

Struggling with personal demons

Being burdened with a dark secret

Having compassion for others

Feeling deeply compelled to serve God to the best of their ability

Feeling guilty about past mistakes or present weaknesses

Seeking redemption or forgiveness

Willingly making sacrifices for others

Being disillusioned by the cruelties and harsh realities of the world

Going to great lengths to keep his indiscretions secret

Being full of contradictions…

SITUATIONS THAT WILL CHALLENGE THEM

A situation that threatens to reveal the character’s vice

Encountering someone who challenges the priest’s beliefs

Being tempted in a new area…

TWIST THIS TROPE WITH A CHARACTER WHO���

Is a whiskey priest in an unorthodox genre, such as sci-fi or inspirational fiction

Has a reason for giving in to his temptation that goes beyond a simple lack of will power

Has an atypical trait: disrespectful, disciplined, perfectionist, quirky, etc…

CLICH��S TO BE AWARE OF

The flat character whose vice is the only thing the reader really knows about them

A weak-willed priest who declares a desire to overcome his sin but continually gives in with little resistance…

Other Type and Trope Thesaurus entries can be found here.

Need More Descriptive Help?

Need More Descriptive Help?While this thesaurus is still being developed, the rest of our descriptive collection (16 unique thesauri and growing) is accessible through the One Stop for Writers THESAURUS database.

If you like, swing by and check out the video walkthrough for this site, and then give our Free Trial a spin.

The post Character Type & Trope Thesaurus: Whiskey Priest appeared first on WRITERS HELPING WRITERS��.

Writers Helping Writers

- Angela Ackerman's profile

- 1022 followers