Angela Ackerman's Blog: Writers Helping Writers, page 29

October 24, 2023

Why ���But��� is a Powerful Writing Tool

Boredom is a common reason why a reader DNFs a book. Genre is irrelevant. If the reader isn���t engaged with the storyline, they will set aside your book for another that will draw them in.

A but means a complication, an obstacle the main character(s) must overcome. If the main character achieves their goals too easily, you���ll rob the reader of anticipation. The journey dies before it begins. Anticipation holds the reader in suspense, forcing them to flip pages late into the night.

Complications and obstacles draw readers in and give them a reason to root for the hero. One way to accomplish this is with but. Real life is filled with obstacles. Let���s look at a few examples.

���Buts��� in the Natural World

A giraffe���s long neck helps them reach leaves at the top of trees, but that same neck causes them to have the highest blood pressure of any animal.

A rhino���s horn is their greatest asset in a fight, but that same horn makes them targets for poachers.

Boreal Owls are usually monogamous, but when prey numbers peak, males cheat with up to three females and female boreal owls often have at least one boyfriend on the side. So much for monogamy, right?

Gray whales can submerge for fifteen minutes at a time, but a mother���s calf can only hold their breath for five minutes. When under attack by Orca, the mother flips on her back to create a platform for her baby, but Momma can���t breathe upside down.

The Rhythm of ���Buts���In the following example, I���ve tried not to infuse emotion, characterization, and visceral elements to keep the focus on but. Obviously, we need more than but to write a gripping scene. Okie doke. Here we go���

Sarah���s car peters out of gas on a lonely back road with little, if any, traffic. She does have AAA but forgot her phone at home. So, she begins the long trek to the gas station. About a half-mile away from her car, an approaching vehicle���s headlights spiral through her legs. Hope soars like eagle wings but is quickly dashed by the recent news reports of missing women.

Should she accept the ride? If she does, she risks her life, but if she doesn���t, she���ll need to hike another four miles in the dark.

Sarah plays it safe, but lightning cracks open the sky thirty seconds after the good Samaritan leaves. Her father taught her a shortcut, but the trail slices through the dark forest. If she chooses that path, she���ll be alone���isolated���with predators stalking the shadows.

Sarah weighs the pros and cons, but she���s tired and hungry. The shortcut shaves off two miles. Every minute matters. Long delays might tempt Bella to pee on her new rug. Wouldn���t be the first time, but the fibers could only absorb so much puppy urine and cleanser before the color fades.

In the woods, tree canopies umbrella the rain, but they also block the last few trickles of moonlight. Regardless, she continues, but hiking through rough terrain in sandals isn���t easy. Soon, a growl stops her cold, but the rain muffles soundwaves. Animal voices pinball through the trees, but she can���t pinpoint their origin. She quickens her pace, but the toe of her sandal catches on an exposed root, and she falls. She crawls back to her feet, but pain spreads through her ankle.

***

Now, if we leave all the but words, the narrative will become monotonous fast. It���s fine to keep them while learning the rhythm of cause and effect. Just be sure to rewrite during edits without sacrificing the complications and obstacles. By doing so, it���ll force you to vary sentence structure as well, which also improves the manuscript.

How To Rewrite ���But��� ConstructionLet���s use the same example.

On a lonely back road with little, if any, traffic, Sarah���s car peters out of gas. If she grabbed her phone off her kitchen table before she left, she could call AAA. The costly membership won���t benefit her now.

About a half-mile into the long trek to the gas station, an approaching vehicle���s headlights spiral through her legs. Hope soars like eagle wings, then crashes. The recent news reports of missing women squash the idea of climbing into a car with a stranger.

Should she accept the ride? If she does, she risks her life. If she doesn���t, she���ll need to hike another four miles in the dark.

Playing it safe, Sarah declines the offer. Not thirty seconds after the good Samaritan leaves, lightning cracks open the sky. Her father taught her a shortcut, but the trail slices through the dark forest. If she chooses that path, she���ll be alone���isolated���with predators stalking the shadows.

When she weighs the pros and cons, hunger and exhaustion win. Dad���s shortcut shaves off two miles. Every minute matters. Long delays might tempt Bella to pee on her new rug. Again. The fibers could only absorb so much puppy urine and cleanser before the color fades.

In the woods, tree canopies umbrella the rain, but they also block the last few trickles of moonlight. Regardless, she continues. Hiking through rough terrain in sandals isn���t easy. This shortcut better work.

Soon, a growl stops her cold. With the rain muffling soundwaves, could she trust her ears? Multiple animal voices pinball through the trees, but she can���t pinpoint their origin. She quickens her pace. Three hard-earned strides later, the toe of her sandal catches on an expose root, and she sails through the air, landing face-down in mud and muck.

When she crawls back to her feet, pain spreads through her ankle.

Uh-oh. Now what?

The first example has thirteen buts. The rewrite has three while still maintaining the cause-and-effect rhythm aka motivation-reaction units or MRUs. The power of but forces us to create complications and obstacles. So, the next time you struggle with a boring scene, add a few buts. You may be surprised by how much your scene improves.

Do you keep but in mind while writing?The post Why ���But��� is a Powerful Writing Tool appeared first on WRITERS HELPING WRITERS��.

October 21, 2023

Character Type & Trope Thesaurus: Bossy Britches

In 1959, Carl Jung first popularized the idea of archetypes���”universal images that have existed since the remotest times.” He posited that every person is a blend of these 12 basic personalities. Ever since then, authors have been applying this idea to fictional characters, combining the different archetypes to come up with interesting new versions. The result is a sizable pool of character tropes that we see from one story to another.

Archetypes and tropes are popular storytelling elements because of their familiarity. Upon seeing them, readers know immediately who they’re dealing with and what role the nerd, dark lord, femme fatale, or monster hunter will play. As authors, we need to recognize the commonalities for each trope so we can write them in a recognizable way and create a rudimentary sketch for any character we want to create.

But when it comes to characters, no one wants just a sketch; we want a vibrant and striking cast full of color, depth, and contrast. Diving deeper into character creation is especially important when starting with tropes because the blessing of their familiarity is also a curse; without differentiation, the characters begin to look the same from story to story.

But no more. The Character Type and Trope Thesaurus allows you to outline the foundational elements of each trope while also exploring how to individualize them. In this way, you’ll be able to use historically tried-and-true character types to create a cast for your story that is anything but traditional.

DESCRIPTION: This take-charge character is a born (micro) manager who has strong opinions and no problem telling people what to do.

FICTIONAL EXAMPLES: Hermione Granger (the Harry Potter series), Harriet M. Welsch (Harriet, the Spy), Lucy (Peanuts), Regina George (Mean Girls), Sheldon Cooper (The Big Bang Theory)

COMMON STRENGTHS: Ambitious, Bold, Confident, Decisive, Disciplined, Efficient, Focused, Independent, Industrious, Intelligent, Meticulous, Organized, Passionate, Persistent, Persuasive, Responsible, Sensible, Studious

COMMON WEAKNESSES: Abrasive, Cocky, Controlling, Haughty, Humorless, Inflexible, Judgmental, Know-It-All, Manipulative, Nagging, Obsessive, Perfectionist, Pushy, Tactless, Workaholic

ASSOCIATED ACTIONS, BEHAVIORS, AND TENDENCIES

Being unafraid to stand up for themselves

Enjoying being in charge

Being on time (or early) for everything

Having a knack for getting things done

Is highly competent

Having good leadership qualities

Is often well-liked by teachers, bosses, and other authority figures

Micromanaging others

Being annoyed by inefficiency and incompetence

Not knowing how to have fun

Using a tough exterior to mask insecurity

SITUATIONS THAT WILL CHALLENGE THEM

Having to work with someone who’s lazy or incompetent

Being replaced as a leader

Having a child who sees the world and operates differently than the character

Having to learn a skill or hobby they’re not good at

TWIST THIS TROPE WITH A CHARACTER WHO���

Has high empathy for others

Has a strong group of friends

Knows how to compromise

Has an atypical trait: humble, mischievous, nurturing, philosophical, etc.

CLICH��S TO BE AWARE OF

A bossy character who is domineering 100% of the time, in every situation

The Hermione Granger schoolgirl version of a bossy britches

Other Type and Trope Thesaurus entries can be found here.

Need More Descriptive Help?

Need More Descriptive Help?While this thesaurus is still being developed, the rest of our descriptive collection (16 unique thesauri and growing) is accessible through the One Stop for Writers THESAURUS database.

If you like, swing by and check out the video walkthrough for this site, and then give our Free Trial a spin.

The post Character Type & Trope Thesaurus: Bossy Britches appeared first on WRITERS HELPING WRITERS��.

October 18, 2023

Phenomenal First Pages Contest – Guest Editor Book Blurb Edition

Hey, wonderful writerly people! It���s time for our monthly critique contest. This month, we have a unique contest.

Hey, wonderful writerly people! It���s time for our monthly critique contest. This month, we have a unique contest. 10 winners will receive feedback on their book blurb from a professional editor!

Here’s a post with helpful tips for crafting a blurb…which is the copy on the back cover of a book or the sales webpage, explaining what the book is about. It’s usually two to three paragraphs in length.

Winners may send the kind of back cover book blurb described in the post linked above…or you may share the book blurb you’d like to include in a query or cover letter to an agent or editor. If you’re a winner and intend the blurb to be inside a query or cover letter, please let Erica know.

PLEASE NOTE: We’ve recently changed our process for entering this contest.

If you’d like a chance to win feedback, use this link or click the graphic below to reach our ENTRY FORM:

ENTRY FORM

ENTRY FORMWhen you enter by form, double check that your email is correct so I’ll be able to contact you if I draw your name. (If I can’t reach you, you’ll have to forfeit your win.)

The editor you’ll be working with:Erica Converso

I���m Erica Converso, author of the Five Stones Pentalogy (affiliate link). I love chocolate, animals, anime, musicals, and lots and lots of books ��� though not necessarily in that order. In addition to my work as an author, I have been an intern at Marvel Comics, a college essay tutor, and a database and emerging technologies librarian. Between helping adult patrons in the reference section and mentoring teens in the evening reading programs, I was also the resident research expert for anyone requiring more in-depth information for a project.

As an editor, I aim to improve and polish your work to a professional level, while also teaching you to hone your craft and learn from previous mistakes. With every piece I edit, I see the author as both client and student. I believe that every manuscript presents an opportunity to grow as a writer, and a good editor should teach you about your strengths and weaknesses so that you can return to your writing more confident in your skills. Visit my website astrioncreative.com for more information on my books and editing and coaching services.

Contest GuidelinesComments will NOT enter you in this contest. To enter, fill out this contest form. (One entry per person.)Have your blurb ready to go. This contest only runs for 24 hours, so enter by form ASAP.We use Random.org to draw winners, and will post the names in the comments tomorrow morning. If you win, I’ll be in touch!

If you���d like to be notified about our monthly Phenomenal First Pages contest, consider subscribing to our blog (see the right-hand sidebar).

A huge thank you to Erica, and good luck to all! I can’t wait to see who the winners will be.

PS: Here’s a blog post with tips for writing a top notch blurb by Erica Converso.

Here���s an incredible worksheet that will help you build an eye-catching blurb! Ready Chapter 1 is celebrating the launch of their free Peer Critique forum and shared this to prepare people for their blurb contests (where you can win agent feedback). They generously allowed me to share this resource with you.

The post Phenomenal First Pages Contest – Guest Editor Book Blurb Edition appeared first on WRITERS HELPING WRITERS��.

October 17, 2023

Three Ways to Make Readers Care About Secondary Characters

A common mistake I see in client manuscripts is a cast of secondary characters that simply exist to help or to outright block the protagonist. They���re either ready, willing, and able to drop everything to help that protagonist reach their own goal. Or they���re a character who is out to make the protagonist���s life hard for no logical reason.

Let���s face it. That���s not how real life works, as everyone has wants and needs of their own. Fictional secondary characters are no different. Their relationship with your protagonist should work like sandpaper, revealing internal growth your protagonist needs, or revealing their commitment to reaching their external goal. If we craft our secondary characters well, they should create a tug-of-war inside the reader. Readers should empathize with each secondary character���s inner motivation and struggle with who to primarily cheer for. This applies to antagonists every bit as much as it does to an ally. Conjuring empathy for each and every secondary character makes those characters more engaging, and it forces you as the writer to create the most compelling protagonist possible. Your protagonist���s desire to reach a particular goal fueled by unmet inner need will have to work that much harder to earn that top spot in reader���s hearts because you���ll have crafted compelling contenders, vying for that spot.

Let���s talk about three ways to achieve this���

They Must Have Their Own Inner Desire/External Goal

It helps to look at any given scene from the perspective of every secondary character you���ve included. If those characters are only on the page to help your protagonist achieve/block their goal, then it���s a missed opportunity. Secondary characters should consistently add tension to scenes���tension that grows your protagonist internally or externally. It���s far more interesting when we get a sense for what other characters want in a scene because we can gauge how that may help or harm what the protagonist wants.

Even if your secondary character is supporting your protagonist and aiming to reach the same external goal, their inner motivation shouldn���t be the same as any other character. What���s motivating each of your secondary characters? Does their motivation conjure empathy in the reader, even if we don���t support that end or we still cheer for the protagonist more? What���s the logic or backstory behind that secondary character���s motivation? Does your protagonist wrestle with the way even an antagonist presents logical motivation to them? Does your protagonist struggle seeing what their allies are giving up in order to support the protagonist���s end?

Tip: A secondary character cannot help or rescue your character without your character losing something they value.

The Secondary Character Must Challenge Your Protagonist in Some External And/Or Internal Way

If your secondary character is an ally or a romantic interest of your protagonist, we might not expect that they���re working like an antagonist, trying to thwart the protagonist���s success. Still, even allies and love interests should be working to grow the protagonist.

*Is that secondary character working like a mirror the protagonist doesn���t want to see themselves in?

*Are they asking hard questions about the protagonist���s hidden fears or motivations?

*Is the secondary character someone the protagonist wants to be like but they���re not ready or unable to accept that they���re never going to be that way?

*Are they asking more from your protagonist than the protagonist is ready to give?

*What does retaining that ally or love interest cost your protagonist?

*How does having that character���s help or support complicate things?

*Are they forcing your protagonist to look at backstory events from a different perspective?

*Forcing the protagonist to empathize with the motivation of any given antagonist?

Tip: The answers to these questions should not be the same for any two secondary characters. Each secondary character must challenge the protagonist differently in order to earn their keep.

Their Dialogue Can���t Solely Exist to Teach Your Character (And Reader) About The Story WorldWe���ve all heard it. Secondary characters saying things like, ���As you know,��� or sitting your character down to hand them the handbook on your story world. As much as possible, the dialogue and even the actions of your secondary characters should convey intent and a hint of their own inner world. The problem with dialogue that carries worldbuilding or stark plot-based information is that it oftentimes fails to reveal more to us about your protagonist or that secondary character. Worse yet, it leaves almost no room for the protagonist to respond with dialogue that conveys their own intent or emotion. Unless your protagonist has approached a secondary character with a very specific question that requires an answer containing information, try to think of secondary character dialogue as an opportunity to reveal their intent and emotion as much as possible. To challenge your protagonist.

Tip: Study every line of dialogue to see if you can attach an emotional ���label��� to it. You should be able to read the line and sense some primary emotional current running through the content. Anger, avoidance, relief, elation, etc. Emotions that are almost always red flags for weak dialogue are characters expressing awe or curiosity. Lines like, ���Wow!��� or, ���What is that?��� Those types of lines simply exist to set the other character up to talk at the other character/us more. If the line of dialogue doesn���t leave space for a response of some sort, then you know it���s not reaching its potential for adding tension.

What aspects of secondary character creation do you struggle with most? Do you find secondary characters easier to craft since the pressure isn���t as direct as it may be in crafting the protagonist? When you develop secondary characters, how do you bring them to life effectively?Happy writing!The post Three Ways to Make Readers Care About Secondary Characters appeared first on WRITERS HELPING WRITERS��.

October 14, 2023

Character Type & Trope Thesaurus: Antihero

In 1959, Carl Jung first popularized the idea of archetypes���”universal images that have existed since the remotest times.” He posited that every person is a blend of these 12 basic personalities. Ever since then, authors have been applying this idea to fictional characters, combining the different archetypes to come up with interesting new versions. The result is a sizable pool of character tropes that we see from one story to another.

Archetypes and tropes are popular storytelling elements because of their familiarity. Upon seeing them, readers know immediately who they’re dealing with and what role the nerd, dark lord, femme fatale, or monster hunter will play. As authors, we need to recognize the commonalities for each trope so we can write them in a recognizable way and create a rudimentary sketch for any character we want to create.

But when it comes to characters, no one wants just a sketch; we want a vibrant and striking cast full of color, depth, and contrast. Diving deeper into character creation is especially important when starting with tropes because the blessing of their familiarity is also a curse; without differentiation, the characters begin to look the same from story to story.

But no more. The Character Type and Trope Thesaurus allows you to outline the foundational elements of each trope while also exploring how to individualize them. In this way, you’ll be able to use historically tried-and-true character types to create a cast for your story that is anything but traditional.

DESCRIPTION: This trope is a subversion of the hero archetype in the form of a main character who lacks the qualities of the typical hero. Morally ambiguous and often self-serving, they tend to be deeply wounded and flawed individuals with stories that often end in tragedy.

FICTIONAL EXAMPLES: Severus Snape (The Harry Potter series), Scarlett O’Hara (Gone With the Wind), Holden Caulfield (The Catcher in the Rye), Harley Quinn (the DC universe), Tony Soprano (The Sopranos), Walter White (Breaking Bad)

COMMON STRENGTHS: Adaptable, Ambitious, Bold, Confident, Creative, Decisive, Discreet, Focused, Independent, Industrious, Intelligent, Meticulous, Patient, Perceptive, Persistent, Protective, Resourceful, Talented

COMMON WEAKNESSES: Abrasive, Cocky, Controlling, Cynical, Devious, Dishonest, Disloyal, Greedy, Hypocritical, Manipulative, Obsessive, Perfectionist, Rebellious, Reckless, Selfish, Sleazy, Unethical, Vindictive, Violent, Volatile

ASSOCIATED ACTIONS, BEHAVIORS, AND TENDENCIES

Being pragmatic about what needs to be done

Working according to their own moral code (which others may not agree with)

Having a strong survival instinct (being resilient)

Determinedly pursuing their goals

Having good listening skills

Being secretive

Knowing how to read people

Fooling even their closest loved ones into seeing the antihero the way they want to be seen

Refusing to entertain doubts about their motives or choices

Doing whatever it takes to save themselves

SITUATIONS THAT WILL CHALLENGE THEM

Someone discovering a secret the antihero desperately wants to keep under wraps

Being betrayed by someone close to them

Working with someone who points out their hypocrisy

TWIST THIS TROPE WITH A CHARACTER WHO���

Successfully navigates a change arc instead of ending up the same or worse than where they started

Has a unique skill or hobby

Has an atypical trait: flamboyant, nature-focused, scatterbrained, witty, wise, etc.

CLICH��S TO BE AWARE OF

The emotionally flat antihero (or one with no positive emotions)

The lone wolf antihero who has no friends

The antihero with no character arc and no capacity to change

Other Type and Trope Thesaurus entries can be found here.

Need More Descriptive Help?

Need More Descriptive Help?While this thesaurus is still being developed, the rest of our descriptive collection (16 unique thesauri and growing) is accessible through the One Stop for Writers THESAURUS database.

If you like, swing by and check out the video walkthrough for this site, and then give our Free Trial a spin.

The post Character Type & Trope Thesaurus: Antihero appeared first on WRITERS HELPING WRITERS��.

October 12, 2023

How to Craft a Top-Notch Blurb

By Erica Converso

Your book is unique ��� unlike any other in the world. But the structure of a well-crafted blurb will not ��� and should not ��� be. A blurb is the copy on the back cover of a book or the sales webpage, explaining what the book is about, usually about two to three paragraphs in length.

Blurbs are a tool for writers to explain to future readers what they���ll be getting if they choose your book. To appeal to them effectively, writers should answer the reader in the same way. This means that blurbs from nonfiction to romance have much in common.

Your reader will want to know certain things before they settle in with your story. And everything they want to know will begin with:

Who?

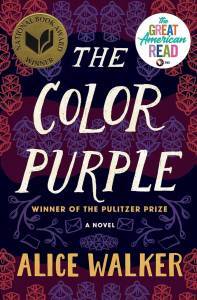

For fiction, who is your protagonist? Give us something about her. Let���s look at the blurb for The Color Purple, by Alice Walker.

���Celie has grown up poor in rural Georgia, despised by the society around her and abused by her own family. She strives to protect her sister, Nettie, from a similar fate, and while Nettie escapes to a new life as a missionary in Africa, Celie is left behind without her best friend and confidante, married off to an older suitor, and sentenced to a life alone with a harsh and brutal husband.���

As you can see from the bold text, we can learn a lot about who from this blurb. In only two sentences, we���ve found out Celie���s background, her early hopes and dreams, and the struggles she will have to overcome during the course of her story.

For nonfiction, the who is somewhat different. In memoir or biography, the who is the subject of the work, and they���re introduced in just a sentence or two. For works where the author is an expert, the blurb might instead begin with:

What?

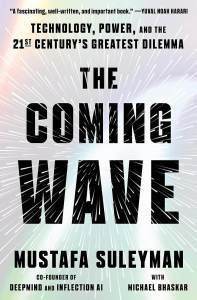

A good example is in the blurb for the book The Coming Wave:

���Everything is about to change. Soon you will live surrounded by AIs. They will organise your life, operate your business, and run core government services. You will live in a world of DNA printers and quantum computers, engineered pathogens and autonomous weapons, robot assistants and abundant energy. None of us are prepared.

As co-founder of the pioneering AI company DeepMind, part of Google, Mustafa Suleyman has been at the centre of this revolution.���

We began with what ��� the issue that the book plans to explore. The blurb personalizes the subject, by using language like ���you��� and ���us.��� It then follows with a reason that the who ��� in this case, the author ��� is capable of explaining that topic to you. By contrast, the Nobel Prize-winning poetry book The Wild Iris gives you only a brief mention of who, followed by a what:

���From Pulitzer Prize-winning poet Louise Gl��ck, a stunningly beautiful collection of poems that encompasses the natural, human, and spiritual realms.���

Note the use of adjectives to encourage the reader to pick up this stunning, beautiful book? Whether you���re pitching fiction or nonfiction, don���t be afraid to talk up your work. If you���ve created a magical land, seductive characters, or compelling research, say so! Even if your reader picks your book up for free from the library, you are still trying to sell it to them. You are trying to sell your reader and all of their friends and family on this single, extraordinary concept: that it���s worthwhile for the reader to voluntarily give up time and effort ��� which they could spend on any other book, or anything else in the world, for that matter ��� to read what you have written. If you want to convince people to pick up your book, give them lots of good reasons to read it!

How?How is also a very useful question for nonfiction. Summarize the main points of your book, focusing on your thesis.

In fiction, use how to give a preview of your plot. Who/what + a few details about the story like any interesting side characters, the stakes, and your main character���s approach to problem-solving in the narrative = your how. Don���t overdo here. Think of your blurb like an overture to a musical, with your first pages as the opening number.

Where? and When?

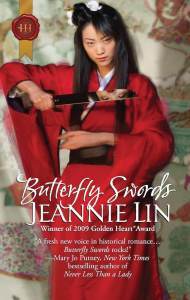

Where and when both function to give your work boundaries. For these questions, let���s take a look at the first sentence of the blurb for Jeannie Lin���s Butterfly Swords:

���During China���s infamous Tang Dynasty, a time awash with luxury yet littered with deadly intrigues and fallen royalty, betrayed Princess Ai Li flees before her wedding.���

What you choose to leave out of your blurb is as important as what you choose to put in. Many people try to cram the entire summary of their book into the blurb. But that is not the point. A good blurb doesn���t spoil the whole story for you ��� it gives you only enough information to make you ask questions. Readers want to be surprised, to learn, to discover. Explain why they should follow you into the world of your book, give them the limits of where it will take them so they know they���re following a guided tour of that world, and tell them what���s so important about bothering with this particular book. Anything else is irrelevant.

And this brings us to the final question:

Why?Why should readers choose this book? For that, you will need to resolve your blurb with either a hook or a call to action.

The HookThis is a statement to grab readers��� attention. In fiction, it should come in one of two forms: a question directly to the reader, or an either/or statement. This important declaration lets readers know there is a way for the protagonist to win or lose, and either could happen by the end of the novel. Depending on your genre the stakes could be huge, such as saving the world or dooming it. Consider the blurb for The Amber Spyglass, by Philip Pullman:

���Throughout the worlds, the forces of both heaven and hell are mustering to take part in Lord Asriel’s audacious rebellion. Each player in this epic drama has a role to play���and a sacrifice to make. Witches, angels, spies, assassins, tempters, and pretenders, no one will remain unscathed.���

But the stakes could also be less catastrophic, though important to the protagonist: ���Will Beezus find the patience to handle her little sister before Ramona turns her big day into a complete disaster?��� (from Beverly Cleary���s Beezus and Ramona)

A Call to ActionA strong CTA instructs the reader to do something or perform an action. Sometimes it���s as simple as advising them to read your book.

Here���s a good example from Marie Kondo���s The Life-Changing Magic of Tidying Up: ���This international bestseller will help you clear your clutter and enjoy the unique magic of a tidy home ��� and the calm, motivated mindset it can inspire.��� This final sentence both encourages you to do something ��� clean up ��� and tells you about the rewards you will receive from doing so ��� enjoying your home and a calm mind.

So there you have it ��� the basics of how to build a perfectly structured blurb. Figure out the answers to the questions above and you���ll have all you need to craft a winning description that will attract readers��� attention, resolve the question ���Why this book?��� and pose new questions that the reader will want to dive right in to find the answers to.

Start working on your blurb now���because we have a new contest on October 19. TEN lucky winners will receive a blurb critique from guest editor Erica Converso!

Here’s an incredible worksheet that will help you build an eye-catching blurb! Ready Chapter 1 is celebrating the launch of their free Peer Critique forum and shared this to prepare people for their blurb contests (where you can win agent feedback). They generously allowed me to share this resource with you.

Here are a few additional helpful posts about writing blurbs.

Please let us know in the comments if you have any questions.

Back Cover Copy Formula (Writers Helping Writers Resident Writing Coach Sue Coletta)

Blurbs that Bore, Blurbs that Blare (Writers Helping Writers)

How to Write a Book Blurb (Fictionary)

How To Write Book Blurbs: 8 Tips for Selling By Summary (Now Novel)

This post contains affiliate links.

Erica Converso, author of the Five Stones Pentalogy, (affiliate link) loves chocolate, animals, anime, musicals, and lots and lots of books ��� though not necessarily in that order. In addition to her writing, she has also been a research and emerging technologies librarian. Check out Erica���s blog for free resources!

As an editor, she aims to improve and polish your work to a professional level, while also teaching you to hone your craft and learn from previous mistakes. With every piece she edits, she sees the author as both client and student. She believes every manuscript presents an opportunity to grow as a writer, and a good editor should teach you about your strengths and weaknesses so that you can return to your writing more confident in your skills. Visit her website astrioncreative.com for more information on her books and editing and coaching services.

The post How to Craft a Top-Notch Blurb appeared first on WRITERS HELPING WRITERS��.

October 9, 2023

Writing Flawed Characters Who Don’t Turn Readers Off

No one in the real world is perfect, and so characters shouldn’t be either. To seem as real as you or me, they should have flaws and strengths, and these sides of their personality should line up with who they are, how they were raised, and reflect the experiences they’ve had to date, good and bad.

While we develop our characters, however, we need to remember that flaws come with a tipping point. If we write someone with an overabundance of negative traits and behaviors that are a turnoff, the character will slide into unlikable territory. And yes, if the goal is to make a villain, antagonist, or other character loathsome, that’s fine–mission accomplished. But if we want readers to be on their side, too much surliness, negativity, secretiveness, or propensity for overblown reactions can cause a reader to disconnect.

Like a joke taken too far, it���s hard to claw an audience back once they’ve formed negative judgments, which is why we want to be careful and deliberate when showing our character’s negative side. Antiheroes tend to wear flaws more openly and can be semi-antagonistic as they battle the world’s constraints, so this line of likability is something to pay close attention to if we want readers to ultimately side with them. Here are some tips to help you.

How to Write Flawed Characters& Not Turn Readers Off

Show A Glimmer: no matter how impatient, uptight, or spoiled your character is, hint there���s more beneath the surface. A small action or internal observation can show the character in a positive light, especially when delivered in their first scene (frequently referred to as a Save the Cat moment.) It can be a positive quality, like a sense of humor, or a simple act that shows something redeeming about the character.

Imagine a man yelling at the old ladies crowding the hallway outside his apartment door as they pick up their friend Mabel for bingo, and then seeing him swear and fume at the chuggy elevator for making him late. Not the nicest guy, is he? But when Mr. Suit and Tie gets to his car outside, he stops to dig out a Ziploc bag of cat food and carefully roll down the edges into a makeshift bowl.

What? Here the guy seemed like an impatient jerk, but we discover part of his morning routine is to feed the local stray cat! Maybe he isn���t so bad after all. (Talk about a literal interpretation of ���saving the cat.���)

Use POV Narrative for Insight: characters are flawed for a reason, namely negative experiences (wounds) which create flaws as an ���emotional countermeasure.��� Imagine a hero who stutters, and he was teased about it growing up. Even his parents encouraged him to ���be seen and not heard��� when they hosted parties and special events. Because of the emotional trauma (shame and anger) at being treated badly, he���s now uncommunicative and unfriendly as an adult. This type of backstory can be dribbled into narrative with care, as long as it���s active, has bearing on the current action, and is brief as to not slow the pace.

Create Big Obstacles: the goal is to create empathy as soon as possible, and one of the ways to do that is to show what the character is up against. If your character has a rough road ahead, the reader will make allowances for behavior, provide they don’t wallow and whine overmuch. After all, it isn���t hardship that creates empathy…it���s how a character behaves despite their hardship as that gives readers a window into who they really are.

Trait Boxed Set (eBook, PDF)

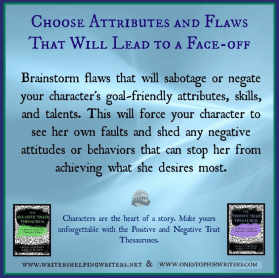

Trait Boxed Set (eBook, PDF)Form a Balance: No character is all good or all bad. Give them a mix of positive traits (attributes) and negative traits (flaws) so they feel realistic, and ensure their negative traits contain a learning curve. For example, their negative traits may be good at keeping people and uncomfortable situations at a distance in the past, but in your story, they won’t help your character get what they want. Your character will have to see this for themselves, and it’ll only happen when that flawed behavior and way of thinking leads to poor judgment, mistakes, relationship friction, and other problems, the poor sap.

Eventually the character will see that they need to change up their behavioral playlist if they want to succeed, and this means letting go of the bad and embracing the good, opening their mind to a new way of thinking, behaving, and being. This is where their positives get to shine, so lay the foundation with qualities that may start in the background, but come forward and show them to be rounded, likable, and unique.

Of Special Concern:

Of Special Concern:Your Story’s Baddies

It���s easy to give an antagonist flaws because your intent is to make readers dislike them, but even here, caution is needed. Hopelessly flawed antagonists make shallow characters and unworthy opponents, so we want to also give them strengths (like intelligence, meticulousness, dedication, and discipline, for example) to make them formidable and hard to beat.

This forces your protagonist to work their hardest, and in a match up, nothing is guaranteed. Being uncertain about the outcome of these story moments is what will hold the reader’s attention to the very end.

To build balanced, unique characters and find traits, positive and negative, that will make sense for them, take a look at the Positive Trait & Negative Trait Thesaurus Writing Guides. We created these to make character building easier for you.

Happy writing!

The post Writing Flawed Characters Who Don’t Turn Readers Off appeared first on WRITERS HELPING WRITERS��.

October 7, 2023

How to Create Mood Effectively in Your Fiction

By C. S. Lakin

Every person or character, at any given time, is in a particular mood. Generally, mood is a person���s state of mind, but it���s more than that. Mood can also describe the disposition of a collective of people, a certain time in history, or the ether of a place.

Regardless of what kind of mood we speak of, it���s always subjective. Ten people can be experiencing the same event at the same place and time, yet, depending on their perspective, their individual mood will differ.

We all know about moods and have a range of them we express and feel, whether we���re aware of them or not. We can sense others��� moods just as they can sense ours. The mood of the character should affect the way he perceives his environment, and expert writers will carefully choose words and imagery that act like a mirror to their emotions.

First, Consider Your Scene���s PurposeYour story may have an overall tone or mood, but every scene is a microsystem of mood that depends on the emotional state and mindset of your character. When you plot out your scene, you need to first think about how your character will interact with his setting based on his mood and the purpose of your scene.

Remember: it���s the purpose of the scene that determines all the setting elements���what you choose to have him notice (and not notice) and react to and why.

Words Are EverythingHowever, learn this truth: it is not the originality of a world or the degree of creativity in the world itself that makes a fantasy novel shine with brilliance; it���s the choice of words and phrases that the author uses that evokes not just a right sensory experience but makes readers fall in love with the writing.

Please note: this doesn���t just pertain to fantasy novels. Every novel involves the creation of a ���world,��� and so writers need to take just as much care in the creation of any world in any genre. Take a look at this hastily written sentence:

Bill walked through the forest until he found a cottage set back in the trees . . .

Now consider the reworked description below that I spent a bit more time on:

Bill slogged along the leaf-choked path, the spindly arms of the bare maples quivering in the cold autumn wind���a feeble attempt to turn him back. But he pressed on until he spotted, nestled in a copse of willows, the derelict cottage slumped like a lost orphan, the lidless windows dark and vacant. Hardly a welcoming sight after many tiresome hours of travel.

A specific mood is created by bringing out Bill���s mindset and emotional state. Without knowing anything else about this scene (if I���d written one), a reader can clearly sense the purpose of the action by the things he notices and the words used to describe them

To immerse your readers in the world you���ve created, you need to spend time coming up with masterful description. And the components of such description are the nouns, verbs, and adjectives you choose.

Mood NuancesWe all know about moods and have a range of them we express and feel, whether we���re aware of them or not. We can sense others��� moods just as they can sense ours. The mood of the character should affect the way he perceives his environment, and expert writers will carefully choose words and imagery that act like a mirror to their emotions. It���s a reciprocal factor: mood informs how the character sees his setting, but the setting also informs his mood���shifting it or intensifying it.

Take a look at this passage from The Dazzling Truth (Helen Cullen):

Murtagh opened the front door and flinched at a swarm of spitting raindrops. The blistering wind mocked the threadbare cotton of his pajamas. He bent his head into the onslaught and pushed forward, dragging the heavy scarlet door behind him. The brass knocker clanged against the wood; he flinched, hoping it had not woken the children. Shivering, he picked a route in his slippers around the muddy puddles spreading across the cobblestoned pathway. Leaning over the wrought-iron gate that separated their own familial island from the winding lane of the island proper, he scanned the dark horizon for a glimpse of Maeve in the faraway glow of a streetlamp.

In the distance, the sea and sky had melted into one anthracite mist, each indiscernible from the other. Sheep huddled together for comfort in Peadar ��g���s field, the waterlogged green that bordered the Moones��� land to the right; the plaintive baying of the animals sounded mournful. Murtagh nodded at them.

There was no sight of Maeve.

Culler is masterful in her usage of imagery to convey sensory detail. The feeling of rain on Murtagh���s skin is described by flinching at spitting raindrops. The blistering wind attacks his pajamas. Dragging the heavy door shows the sensation of his muscles working���proprioception. And of course we have visuals, which paint the stage for us.

We also have the sound of the brass knocker���used for a specific purpose���to tell us he���s concerned about the children waking. This is a good point to pay attention to: sensory detail should serve more than one purpose. Don���t just add a sound or sight without thinking of the POV character���s mood, concerns, mindset, and purpose in that moment. The more you can tie those things to the sensory details, the more powerful your writing.

Weather

Writers are sometimes told not to write about weather. It���s boring, right? But weather affects us every moment of every day and night. We make decisions for how we will spend our day, even our life, based on weather. And weather greatly affects our mood, whether we notice or not.

Since we want our characters to act and react believably, they should also be affected by weather. Sure, at times they aren���t going to notice it. But there are plenty of opportunities to have characters interact with weather can be purposeful and powerful in your story.

Strong Verbs and AdjectivesUsing strong and effective verbs and adjectives will help you craft setting descriptions that are masterful. Every word counts. To borrow unfaithfully from Animal Farm: All words are created equal, but some words are more equal than others. Some words are plain boring, and others take our breath away.

Mood is one of the 3 M���s of character setup, and you���ll want to make sure you get the character���s mood, mindset (what she���s concerned about), and motivation on that first page. What happens in the scene will shift the mood in some way, resulting in some change in mood by the end of the scene. So think about what that mood will be like at the start of the scene and what���s changed in the mood by the end. Using the setting interactively with your character is the most powerful way to masterfully accomplish this!

C. S. Lakin is an award-winning author of more than 30 books, fiction and nonfiction (which includes more than 10 books in her Writer���s Toolbox series). Her online video courses at Writing for Life Workshops have helped more than 5,000 fiction writers improve their craft. To go deep into creating great settings and evoking emotions in your characters, and to learn essential technique, enroll in Lakin���s courses Crafting Powerful Settings and Emotional Mastery for Fiction Writers. Her blog Live Write Thrive has more than 1 million words of instruction for writers, so hop on over and level-up your writing!

The post How to Create Mood Effectively in Your Fiction appeared first on WRITERS HELPING WRITERS��.

October 4, 2023

Want to Show Your Character’s Pain? Here’s Everything You Need to Know

For the better part of two months, Becca and I have been exploring pain, and how to write about it in fiction. It’s been enlightening for us, and we hope for you as well. So many ways to torture characters, who knew?

(Well, we did. And you did. Pain is sort of our bread and butter, isn’t it?)

But maybe you missed a post or two. It happens. You were on a writing retreat, or vacationing at the lake. Maybe you were hiding out in a sleeping bag in the woods, denying the arrival of fall and Pumpkin Spice Lattes.

Whatever the case may be, we’ve got you. Here are all the posts in this series. The Three Stages of Awareness

The Three Stages of AwarenessPain has 3 stages: Before, During, and After. For realistic and logical description, you’ll want to know what all three will look like for your character and the type of injury.

Different Types of Pain to Explore

Different Types of Pain to ExploreDiscomfort comes in all shapes and sizes, including physical, psychological, and spiritual pain. Mine this post for ideas on how to bring something fresh to your story by targeting a variety of soft spots.

Describing Minor Injuries

Describing Minor InjuriesCuts, stings, and scrapes create discomfort and can easily lead to bigger problems. You’ll find loads of descriptive detail for showing smaller injuries here, and how they can make your story more realistic.

Describing Major or Mortal Injuries

Describing Major or Mortal InjuriesSometimes a wound is serious, casting doubt on whether your character will survive this crisis. Fill your mental toolbox with ideas on what happens when your character is stricken with an injury with no easy fix.

Describing Invisible Injuries and Conditions

Describing Invisible Injuries and ConditionsNot every injury leaves a physical mark, and when you can’t see it, you don’t know how bad it is. Invisible injuries and conditions are a great vehicle to encourage readers to worry about characters they care about.

Factors that Help or Hinder One’s Ability to Cope

Factors that Help or Hinder One’s Ability to CopeWe all hope we’ll cope well when injured, but certain factors make it easier–or harder–to handle pain. This list will help you steer how a character responds!

Taking an Injury from Bad to Worse

Taking an Injury from Bad to WorseNo one likes to get hurt, but when circumstances are afoot that cause that injury to worsen? Tension and conflict, baby. So, when you’re feeling evil, read this one to see how you can raise the stakes.

Everyday Ways a Character Can Get Hurt

Everyday Ways a Character Can Get HurtWe want to immerse readers in the character’s everyday world, so it helps to think about where dangers and threats might be lurking so we can create a credible collision with pain that comes from a believable source.

Best Practices for Writing Pain in Fiction

Best Practices for Writing Pain in Fiction

Finally, we round up this series with unmissable tips on how to take pain scenes from good, to great. Authenticity is key, and of course, showing and not telling. Don’t miss these final tips to help you write tense, engaging fiction!

We hope this series on pain helps you level up your stories.

Pain is an Emotion Amplifier, and a powerful one at that, so putting in extra effort to showcase it well is worth the time.

Pain presents a challenge for your character while making them more emotionally volatile, and prone to mistakes. This means tension and conflict, drawing readers in!

Pain also helps empathy for because people know pain, and so when a character they care about is battered and bruised, or beset by trauma, readers can’t help but be reminded of their own experiences, and worry over what will happens next.

Before you go…

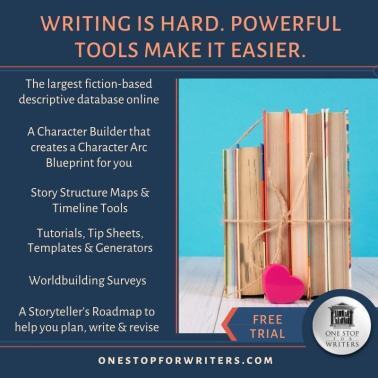

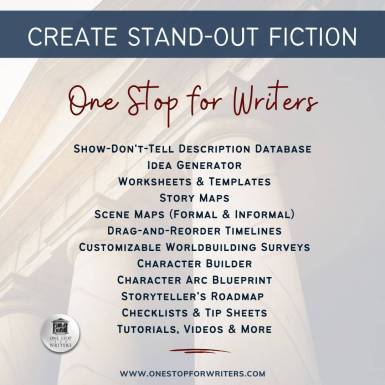

Don’t forget, its birthday week here at Writers Helping Writers as our sister site, One Stop for Writers is turning 8!

We’ve rustled up a nice 25% discount on all subscriptions, so if you want to add some serious thunder to your writer’s toolkit, check out the arsenal of writing tools you get with a OSFW subscription, including the Storyteller’s Roadmap that guides you as you plan, write, and revise.

Happy writing!

The post Want to Show Your Character’s Pain? Here’s Everything You Need to Know appeared first on WRITERS HELPING WRITERS��.

October 3, 2023

Happy 8th Birthday, One Stop for Writers!

Let the good times roll…

One Stop for Writers‘ BIRTHDAY WEEK is here!

It’s hard to believe that Becca and I have been helping writers grow into confident storytellers at One Stop for Writers for EIGHT YEARS now. That’s eight years of supporting writers plan, write, and deliver their books into the hands of excited readers. Eight years of watching creatives all over the world go from pre-published to published. What an incredible ride–thank you so much for letting us join your journey!

Save 25% On All One Stop for Writers PlansEight years is worth celebrating, so here’s a sweet birthday discount for anyone wanting a war chest of storytelling tools to support them as they plan, write, and revise:

EIGHTYEARS

And heck, with NaNoWriMo on the way, you can use October to build your characters, plot their journey, and create the framework of your story’s world.

To use this code:

Sign up or sign in. Choose any paid subscription (1-month, 6-month, or 12-months) and add this code: EIGHTYEARS to the coupon box.Once activated, this one-time 25% discount will apply onscreen.Add your payment method, check the Terms box, and then hit the subscribe button.

And that’s it! All of One Stop for Writers’ resources, including the incredible descriptive THESAURUS, are now part of your storyteller’s toolkit.

Anyone can use this code – new subscribers and existing subscribers!

If you are a current subscriber, go to your My Subscription page (ACCOUNT tab). Click the button under the Coupons and Gift Certificates area and add the code. You’ll see a message when it has been added, and it will automatically apply to your next invoice. Code is active until October 20th, 2023.

New to One Stop?If you’re not familiar with One Stop for Writers, join Becca for a virtual tour. She’ll show you exactly how this site is going to help you write stronger fiction faster:

.ose-uid-2dd46a760741e3e5d65d4f4092be48d6 { width: 600px !important; height: 340px; max-width: 100%; } .ose-uid-2dd46a760741e3e5d65d4f4092be48d6>iframe { height: 340px !important; max-height: 340px !important; width: 100%; } .ose-uid-2dd46a760741e3e5d65d4f4092be48d6 .wistia_embed { max-width: 100%; } .alignright .ose-wistia.ose-uid-2dd46a760741e3e5d65d4f4092be48d6{ margin-left: auto; } .alignleft .ose-wistia.ose-uid-2dd46a760741e3e5d65d4f4092be48d6{ margin-right: auto; } .aligncenter .ose-wistia.ose-uid-2dd46a760741e3e5d65d4f4092be48d6{ margin: auto; } .ose-uid-2dd46a760741e3e5d65d4f4092be48d6 img.watermark{ display: none; } Planning your NaNoWriMo Novel?

If you’re gearing up for NaNoWriMo (National Novel Writing Month) now’s a great time to start building your characters, plotting your story, and creating your world. The Storyteller’s Roadmap will guide you step-by-step to the tools and resources you need.

Once November hits, you’ll love having non-stop ideas on what to write using our Show-Don’t-Tell Database, too. Thanks for helping us celebrate our birthday, and happy writing!

The post Happy 8th Birthday, One Stop for Writers! appeared first on WRITERS HELPING WRITERS��.

Writers Helping Writers

- Angela Ackerman's profile

- 1017 followers