Michael Driscoll's Blog

October 9, 2025

An /intro to Python 3.14’s New Features

Python 3.14 came out this week and has many new features and improvements. For the full details behind the release, the documentation is the best source. However, you will find a quick overview of the major changes here.

As with most Python releases, backwards compatibility is rarely broken. However, there has been a push to clean up the standard library, so be sure to check out what was removed and what has been deprecated. In general, most of the items in these lists are things the majority of Python users do not use anyway.

But enough with that. Let’s learn about the big changes!

Release Changes in 3.14The biggest change to come to Python in a long time is the free-threaded build of Python. While free-threaded Python existed in 3.13, it was considered experimental at that time. Now in 3.14, free-threads are officially supported, but still optional.

Free-threaded Python is a build option in Python. You can turn it on if you want to when you build Python. There is still debate about turning free-threading on by default, but that has not been decided at the time of writing of this article.

Another new change in 3.14 is an experimental just-in-time (JIT) compiler for MacOS and Windows release binaries. Currently, the JIT compiler is NOT recommended in production. If you’d like you test it out, you can set PYTHON_JIT=1 as an environmental variable. When running with JIT enabled, you may see Python perform 10% slower or up to 20% faster, depending on workload.

Note that native debuggers and profilers (gdp and perf) are not able to unwind JIT frames, although Python’s own pdb and profile modules work fine with them. Free-threaded builds do not support the JIT compilter though.

The last item of note is that GPG (Pretty Good Privacy) signatures are not provided for Python 3.14 or newer versions. Instead, users must use Sigstore verification materials. Releases have been signed using Sigstore since Python 3.11.

Python Interpreter ImprovementsThere are a slew of new improvements to the Python interpreter in 3.14. Here is a quick listing along with links:

PEP 649 and PEP 749 : Deferred evaluation of annotations PEP 734 : Multiple interpreters in the standard library PEP 750 : Template strings PEP 758 : Allow except and except* expressions without brackets PEP 765 : Control flow in finally blocks PEP 768 : Safe external debugger interface for CPythonA new type of interpreterFree-threaded mode improvementsImproved error messagesIncremental garbage collectionLet’s talk about the top three a little. Deferred evaluation of annotations refers to type annotations. In the past, the type annotations that are added to functions, classes, and modules were evaluated eagarly. That is no longer the case. Instead, the annotations are stored in special-purpose annotate functions and evaluated only when necessary with the exception of if from __future__ import annotations is used at the top of the module.

the reason for this change it to improve performance and usability of type annotations in Python. You can use the new annotationlib module to inspect deferred annotations. Here is an example from the documentation:

>>> from annotationlib import get_annotations, Format>>> def func(arg: Undefined):

... pass

>>> get_annotations(func, format=Format.VALUE)

Traceback (most recent call last):

...

NameError: name 'Undefined' is not defined

>>> get_annotations(func, format=Format.FORWARDREF)

{'arg': ForwardRef('Undefined', owner=)}

>>> get_annotations(func, format=Format.STRING)

{'arg': 'Undefined'}

Another interesting change is the addition of multiple interpreters in the standard library. The complete formal definition of this new feature can be found in PEP 734. This feature has been available in Python for more than 20 years, but only throught the C-API. Starting in Python 3.14, you can now use the new concurrent.interpreters module.

Why would you want to use multiple Python interpreters?

They support a more human-friendly concurrency modelThey provide a true multi-core parallelismThese interpreters provide isolated “processes” that run in parallel with no sharing by default.

Another feature to highlightare the template string literals (t-strings). Full details can be found in PEP 750. Brett Cannon, a core developer of the Python language, posted a good introductory article about these new t-strings on his blog. A template string or t-string is a new mechanism for custom string processing. However, unlike an f-string, a t-string will return an object that represents the static and the interpolated parts of the string.

Here’s a quick example from the documentation:

>>> variety = 'Stilton'>>> template = t'Try some {variety} cheese!'

>>> type(template)

>>> list(template)

['Try some ', Interpolation('Stilton', 'variety', None, ''), ' cheese!']

You can use t-strings to sanitize SQL, improve logging, implement custom, lightweight DSLs, and more!

Standard Library ImprovementsPython’s standard library has several significant improvements. Here are the ones highlighted by the Python documentation:

PEP 784 : Zstandard support in the standard libraryAsyncio introspection capabilitiesConcurrent safe warnings controlSyntax highlighting in the default interactive shell, and color output in several standard library CLIsIf you do much compression in Python, then you will be happy that Python has added Zstandard support in addition to the zip and tar archive support that has been there for many years.

Compressing a string using Zstandard can be accomplished with only a few lines of code:

from compression import zstdimport math

data = str(math.pi).encode() * 20

compressed = zstd.compress(data)

ratio = len(compressed) / len(data)

print(f"Achieved compression ratio of {ratio}")

Another neat addition to the Python standard library is asyncio introspection via a new command-line interface. You can now use the following command to introspect:

python -m asyncio ps PIDpython -m asyncio pstree PIDThe ps sub-command will inspect the given process ID and siplay information about the current asyncio tasks. You will see a task table as output which contains a listing of all tasks, their names and coroutine stacks, and which tasks are awaiting them.

The pstree sub-command will fetch the same information, but it will render them using a visual async call tree instead, which shows the coroutine relationships in a hierarcical format. Ths pstree command is especiialy useful for debugging stuck or long-running async programs.

One other neat update to Python is that the default REPL shell now highlights Python syntax. You can change the color theme using an experimental API _colorize.set_theme() which can be called interactively or in the PYTHONSTARTUP script. The REPL also supports impor tauto-completion, which means you can start typing the name of a module and then hit tab to get it to complete.

Wrapping UpPython 3.14 looks to be an exciting release with many performance improvements. They have also laid down more framework to continue improving Python’s speed.

The latest version of Python has many other imrpovements to modules that aren’t listed here. To see all the nitty gritty details, check out the What’s New in Python 3.14 page in the documentation.

Drop a comment to let us know what you think of Python 3.14 and what you are excited to see in upcoming releases!

The post An /intro to Python 3.14’s New Features appeared first on Mouse Vs Python.

September 15, 2025

Erys – A TUI for Jupyter Notebooks

Have you ever thought to yourself: “Wouldn’t it be nice to run Jupyter Notebooks in my terminal?” Well, you’re in luck. The new Erys project not only makes running Jupyter Notebooks in your terminal a reality, but Erys also lets you create and edit the notebooks in your terminal!

Erys is written using the fantastic Textual package. While Textual handles the front-end in much the same way as your browser would normally do, the jupyter-client handles the backend, which executes your code and manages your kernel.

Let’s spend a few moments learning more about Erys and taking it for a test drive.

InstallationThe recommended method of installing Erys is to use the uv package manager. If you have uv installed, you can run the following command in your terminal to install the Erys application:

$ uv tool install erysErys also supports using pipx to install it, if you prefer.

Once you have Erys installed, you can run it in your terminal by executing the erys command.

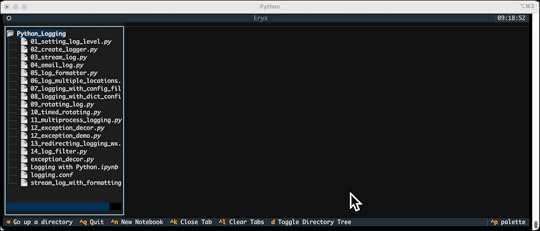

Using Notebooks in Your TerminalWhen you run Erys, you will see something like the following in your terminal:

This is an empty Jupyter Notebook. If you would prefer to open an existing notebook, you would run the following command:

erys PATH_TO_NOTEBOOKIf you passed in a valid path to a Notebook, you will see one loaded. Here is an example using my Python Logging talk Notebook:

You can now run the cells, edit the Notebook and more!

Wrapping UpErys is a really neat TUI application that gives you the ability to view, create, and edit Jupyter Notebooks and other text files in your terminal. It’s written in Python using the Textual package.

The full source code is on GitHub, so you can check it out and learn how it does all of this or contribute to the application and make it even better.

Check it out and give it a try!

The post Erys – A TUI for Jupyter Notebooks appeared first on Mouse Vs Python.

September 3, 2025

Ep 55 – The Python Show Podcast – The Python Documentary with Paul Everitt

In this episode, we have special guest Paul Everitt on the show to discuss the new Python Documentary that was released last week. Paul is the head of developer advocacy at JetBrains and a “Python oldster”.

We chat about Python – the documentary, Paul’s start in programming as well as with Python, and much, much more!

LinksPython: The DocumentaryPaul’s GitHub pagePaul’s X accountHow Python Grew From a Language to a Community – The New StackThe post Ep 55 – The Python Show Podcast – The Python Documentary with Paul Everitt appeared first on Mouse Vs Python.

August 26, 2025

Python Books and Courses – Back to School Sale

If you are heading back to school and need to learn Python, consider checking out my sale. You can get 25% off any of my eBooks or courses using the following coupon at checkout: FALL25

My books and course cover the following topics:

Beginner Python (Python 101)Intermediate PythonCreating GUIs with wxPythonWorking with ExcelImage ProcessingCreating PDFs with PythonWorking with JupyterLabCreating TUIs with Python and TextualPython LoggingStart learning Python or widen your Python knowledge today!

The post Python Books and Courses – Back to School Sale appeared first on Mouse Vs Python.

August 7, 2025

Python 101: Reading TOML with Python

The TOML (Tom’s Obvious Minimal Language) format came out in 2013, so it’s been around for more than a decade. Python added support for TOML in Python 3.11 with its tomllib module in the standard library. However, unlike some of Python’s other standard libraries, such as jsonor its XML-related libraries, the tomllib library is only for reading, not writing. To create TOML documents in Python, you will need a third-party TOML package, such as tomlkit or toml.

Many Python developers use TOML as their configuration format of choice. In fact, you will find that most popular Python packages use a file called pyproject.toml for configuration. You can even use that file as a replacement for requirements.txt. Mypy, Flake8, and other tools can also be configured using pyproject.toml. You can learn more about that file and how it is formatted in the Python packaging guide.

In this tutorial, you will focus only on what Python itself provides for TOML support.

Let’s get started!

Getting StartedPython’s tomllib is based on the tomli package. You can read all about the implementation details and why TOML support was added to Python in PEP 680.

The nice thing about having TOML support built-in to Python is that you do not need to install anything other than Python itself. However, if you need to be able to create or edit a TOML document, then you will need a third-party package as tomllib is read-only.

Reading TOML with PythonTo really understand what happens when you use the tomllib module, you need a TOML file. You can pick your favorite Python package and grab a TOML file from it. For the purposes of this tutorial, you can use the Squall package’s TOML file. Squall is a TUI for viewing and editing SQLite databases.

Here’s what the TOML looks like:

[project]name = "squall_sql"

dynamic = [

"version",

]

description = "Squall - SQLite Editor"

readme = "README.md"

requires-python = ">=3.11"

authors = [

{ name = "Mike Driscoll", email = "mike@nlah.org" },

]

maintainers = [

{ name = "Mike Driscoll", email = "mike@nlah.org" },

]

classifiers = [

"License :: OSI Approved :: MIT License",

"Environment :: Console",

"Development Status :: 4 - Beta",

"Intended Audience :: Developers",

"Intended Audience :: End Users/Desktop",

"Intended Audience :: Other Audience",

"Programming Language :: Python :: 3",

"Programming Language :: Python :: 3.11",

"Programming Language :: Python :: 3.12",

"Programming Language :: Python :: 3.13",

"Operating System :: MacOS",

"Operating System :: Microsoft :: Windows :: Windows 10",

"Operating System :: Microsoft :: Windows :: Windows 11",

"Operating System :: POSIX :: Linux",

"Topic :: Software Development :: Libraries :: Python Modules",

"Typing :: Typed",

]

keywords = [

"tui",

"sql",

"sqlite",

"terminal",

]

dependencies = [

"rich>=13.9.4",

"SQLAlchemy>=2.0.38",

"textual>=2.1.1",

]

packages = [

"src/squall",

]

[project.license]

file = "LICENSE"

[project.urls]

Homepage = "https://github.com/driscollis/squall"

Documentation = "https://github.com/driscollis/squall/..."

Repository = "https://github.com/driscollis/squall"

Issues = "https://github.com/driscollis/squall/..."

Discussions = "https://github.com/driscollis/squall/..."

Wiki = "https://github.com/driscollis/squall/..."

[project.scripts]

squall = "squall.squall:main"

[build-system]

requires = [

"hatchling",

"wheel",

]

build-backend = "hatchling.build"

[dependency-groups]

dev = [

"build>=1.2.1",

"ruff>=0.9.3",

"pyinstrument>=5.0.1",

"textual-dev>=1.7.0",

]

[tool.hatch.version]

path = "src/squall/__init__.py"

[tool.hatch.build.targets.wheel]

packages = [

"src/squall",

]

include = [

"py.typed",

"**/*.py",

"**/*.html",

"**/*.gif",

"**/*.jpg",

"**/*.png",

"**/*.md",

"**/*.tcss",

]

[tool.hatch.build.targets.sdist]

include = [

"src/squall",

"LICENSE",

"README.md",

"pyproject.toml",

]

exclude = [

"*.pyc",

"__pycache__",

"*.so",

"*.dylib",

]

[tool.pytest.ini_options]

pythonpath = [

"src"

]

The next step is to write some Python code to attempt to read in the TOML file above. Open up your favorite Python IDE and create a file. You can call it something like pyproject_parser.pyif you want.

Then enter the following code into it:

import tomllibfrom pathlib import Path

from pprint import pprint

pyproject = Path("pyproject.toml")

with pyproject.open("rb") as config:

data = tomllib.load(config)

pprint(data)

Here you open the TOML file from Squall and load it using the tomllib module. You use Python’s pprintmodule to print it out. The nice thing about the tomllibmodule is that it returns a dictionary.

Of course, the dictionary doesn’t print nicely without using pretty print, which is why you use the pprintmodule here.

The following is the output you will get if you run this code:

{'build-system': {'build-backend': 'hatchling.build','requires': ['hatchling', 'wheel']},

'dependency-groups': {'dev': ['build>=1.2.1',

'ruff>=0.9.3',

'pyinstrument>=5.0.1',

'textual-dev>=1.7.0']},

'project': {'authors': [{'email': 'mike@pythonlibrary.org',

'name': 'Mike Driscoll'}],

'classifiers': ['License :: OSI Approved :: MIT License',

'Environment :: Console',

'Development Status :: 4 - Beta',

'Intended Audience :: Developers',

'Intended Audience :: End Users/Desktop',

'Intended Audience :: Other Audience',

'Programming Language :: Python :: 3',

'Programming Language :: Python :: 3.11',

'Programming Language :: Python :: 3.12',

'Programming Language :: Python :: 3.13',

'Operating System :: MacOS',

'Operating System :: Microsoft :: Windows :: '

'Windows 10',

'Operating System :: Microsoft :: Windows :: '

'Windows 11',

'Operating System :: POSIX :: Linux',

'Topic :: Software Development :: Libraries :: '

'Python Modules',

'Typing :: Typed'],

'dependencies': ['rich>=13.9.4',

'SQLAlchemy>=2.0.38',

'textual>=2.1.1'],

'description': 'Squall - SQLite Editor',

'dynamic': ['version'],

'keywords': ['tui', 'sql', 'sqlite', 'terminal'],

'license': {'file': 'LICENSE'},

'maintainers': [{'email': 'mike@pythonlibrary.org',

'name': 'Mike Driscoll'}],

'name': 'squall_sql',

'packages': ['src/squall'],

'readme': 'README.md',

'requires-python': '>=3.11',

'scripts': {'squall': 'squall.squall:main'},

'urls': {'Discussions': 'https://github.com/driscollis/squall/...',

'Documentation': 'https://github.com/driscollis/squall/...',

'Homepage': 'https://github.com/driscollis/squall',

'Issues': 'https://github.com/driscollis/squall/...',

'Repository': 'https://github.com/driscollis/squall',

'Wiki': 'https://github.com/driscollis/squall/...'}},

'tool': {'hatch': {'build': {'targets': {'sdist': {'exclude': ['*.pyc',

'__pycache__',

'*.so',

'*.dylib'],

'include': ['src/squall',

'LICENSE',

'README.md',

'pyproject.toml']},

'wheel': {'include': ['py.typed',

'**/*.py',

'**/*.html',

'**/*.gif',

'**/*.jpg',

'**/*.png',

'**/*.md',

'**/*.tcss'],

'packages': ['src/squall']}}},

'version': {'path': 'src/squall/__init__.py'}},

'pytest': {'ini_options': {'pythonpath': ['src']}}}}

Awesome! You can now read a TOML file with Python and you get a nicely formatted dictionary!

Wrapping UpThe TOML format is great and well established, especially in the Python world. If you ever plan to create a package of your own, you will probably need to create a TOML file. If you work in dev/ops or as a system administrator, you may need to configure tools for CI/CD in the pyproject.toml file for Mypy, Flake8, Ruff, or some other tool.

Knowing how to read, write and edit a TOML file is a good tool to have in your kit. Check out Python’s tomllib module for reading or if you need more power, check out tomlkit or toml.

Related ReadingPython and TOML: New Best Friends – Real PythonPEP 680 – tomllib: Support for Parsing TOML in the Standard LibraryThe post Python 101: Reading TOML with Python appeared first on Mouse Vs Python.

July 30, 2025

Creating a Simple XML Editor in Your Terminal with Python and Textual

Several years ago, I created an XML editor with the wxPython GUI toolkit called Boomslang. I recently thought it would be fun to port that code to Textual so I could have an XML viewer and editor in my terminal as well.

In this article, you will learn how that experiment went and see the results. Here is a quick outline of what you will cover:

Get the packages you will needCreate the main UICreating the edit XML screenThe add node screenAdding an XML preview screenCreating file browser and warning screensCreating the file save screenLet’s get started!

Getting the DependenciesYou will need Textual to be able to run the application detailed in this tutorial. You will also need lxml, which is a super fast XML parsing package. You can install Textual using pip or uv. You can probably use uv with lxml as well, but pip definitely works.

Here’s an example using pip to install both packages:

python -m pip install textual lxmlOnce pip has finished installing Textual and the lxml package and all its dependencies, you will be ready to continue!

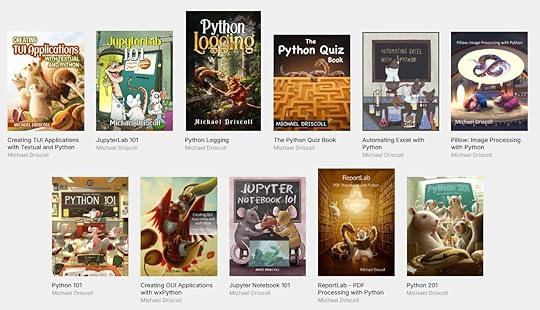

Creating the Main UIThe first step in creating the user interface is figuring out what it should look like. Here is the original Boomslang user interface that was created using wxPython:

You want to create something similar to this UI, but in your terminal. Open up your favorite Python IDE and create a new file called boomslang.py and then enter the following code into it:

from pathlib import Pathfrom .edit_xml_screen import EditXMLScreen

from .file_browser_screen import FileBrowser

from textual import on

from textual.app import App, ComposeResult

from textual.containers import Horizontal, Vertical

from textual.widgets import Button, Header, Footer, OptionList

class BoomslangXML(App):

BINDINGS = [

("ctrl+o", "open", "Open XML File"),

]

CSS_PATH = "main.tcss"

def __init__(self) -> None:

super().__init__()

self.title = "Boomslang XML"

self.recent_files_path = Path(__file__).absolute().parent / "recent_files.txt"

self.app_selected_file: Path | None = None

self.current_recent_file: Path | None = None

def compose(self) -> ComposeResult:

self.recent_files = OptionList("", id="recent_files")

self.recent_files.border_title = "Recent Files"

yield Header()

yield self.recent_files

yield Vertical(

Horizontal(

Button("Open XML File", id="open_xml_file", variant="primary"),

Button("Open Recent", id="open_recent_file", variant="warning"),

id="button_row",

)

)

yield Footer()

def on_mount(self) -> None:

self.update_recent_files_ui()

def action_open(self) -> None:

self.push_screen(FileBrowser())

def on_file_browser_selected(self, message: FileBrowser.Selected) -> None:

path = message.path

if path.suffix.lower() == ".xml":

self.update_recent_files_on_disk(path)

self.push_screen(EditXMLScreen(path))

else:

self.notify("Please choose an XML File!", severity="error", title="Error")

@on(Button.Pressed, "#open_xml_file")

def on_open_xml_file(self) -> None:

self.push_screen(FileBrowser())

@on(Button.Pressed, "#open_recent_file")

def on_open_recent_file(self) -> None:

if self.current_recent_file is not None and self.current_recent_file.exists():

self.push_screen(EditXMLScreen(self.current_recent_file))

@on(OptionList.OptionSelected, "#recent_files")

def on_recent_files_selected(self, event: OptionList.OptionSelected) -> None:

self.current_recent_file = Path(event.option.prompt)

def update_recent_files_ui(self) -> None:

if self.recent_files_path.exists():

self.recent_files.clear_options()

files = self.recent_files_path.read_text()

for file in files.split("\n"):

self.recent_files.add_option(file.strip())

def update_recent_files_on_disk(self, path: Path) -> None:

if path.exists() and self.recent_files_path.exists():

recent_files = self.recent_files_path.read_text()

if str(path) in recent_files:

return

with open(self.recent_files_path, mode="a") as f:

f.write(str(path) + "\n")

self.update_recent_files_ui()

elif not self.recent_files_path.exists():

with open(self.recent_files_path, mode="a") as f:

f.write(str(path) + "\n")

def main() -> None:

app = BoomslangXML()

app.run()

if __name__ == "__main__":

main()

That’s a good chunk of code, but it’s still less than a hundred lines. You will go over it in smaller chunks though. You can start with this first chunk:

from pathlib import Pathfrom .edit_xml_screen import EditXMLScreen

from .file_browser_screen import FileBrowser

from textual import on

from textual.app import App, ComposeResult

from textual.containers import Horizontal, Vertical

from textual.widgets import Button, Header, Footer, OptionList

class BoomslangXML(App):

BINDINGS = [

("ctrl+o", "open", "Open XML File"),

]

CSS_PATH = "main.tcss"

def __init__(self) -> None:

super().__init__()

self.title = "Boomslang XML"

self.recent_files_path = Path(__file__).absolute().parent / "recent_files.txt"

self.app_selected_file: Path | None = None

self.current_recent_file: Path | None = None

You need a few imports to make your code work. The first import comes from Python itself and gives your code the ability to work with file paths. The next two are for a couple of small custom files you will create later on. The rest of the imports are from Textual and provide everything you need to make a nice little Textual application.

Next, you create the BoomslangXML class where you set up a keyboard binding and set which CSS file you will be using for styling your application.

The __init__() method sets the following:

The title of the applicationThe recent files path, which contains all the files you have recently openedThe currently selected file or NoneThe current recent file (i.e. the one you have open at the moment) or NoneNow you are ready to create the main UI:

def compose(self) -> ComposeResult:self.recent_files = OptionList("", id="recent_files")

self.recent_files.border_title = "Recent Files"

yield Header()

yield self.recent_files

yield Vertical(

Horizontal(

Button("Open XML File", id="open_xml_file", variant="primary"),

Button("Open Recent", id="open_recent_file", variant="warning"),

id="button_row",

)

)

yield Footer()

To create your user interface, you need a small number of widgets:

A header to identify the name of the applicationAn OptionList which contains the recently opened files, if any, that the user can reloadA button to load a new XML fileA button to load from the selected recent fileA footer to show the application’s keyboard shortcutsNext, you will write a few event handlers:

def on_mount(self) -> None:self.update_recent_files_ui()

def action_open(self) -> None:

self.push_screen(FileBrowser())

def on_file_browser_selected(self, message: FileBrowser.Selected) -> None:

path = message.path

if path.suffix.lower() == ".xml":

self.update_recent_files_on_disk(path)

self.push_screen(EditXMLScreen(path))

else:

self.notify("Please choose an XML File!", severity="error", title="Error")

The code above contains the logic for three event handlers:

on_mount()– After the application loads, it will update the OptionList by reading the text file that contains paths to the recent files.action_open()– A keyboard shortcut action that gets called when the user presses CTRL+O. It will then show a file browser to the user so they can pick an XML file to load.on_file_browser_selected()– Called when the user picks an XML file from the file browser and closes the file browser. If the file is an XML file, you will reload the screen to allow XML editing. Otherwise, you will notify the user to choose an XML file.The next chunk of code is for three more event handlers:

@on(Button.Pressed, "#open_xml_file")def on_open_xml_file(self) -> None:

self.push_screen(FileBrowser())

@on(Button.Pressed, "#open_recent_file")

def on_open_recent_file(self) -> None:

if self.current_recent_file is not None and self.current_recent_file.exists():

self.push_screen(EditXMLScreen(self.current_recent_file))

@on(OptionList.OptionSelected, "#recent_files")

def on_recent_files_selected(self, event: OptionList.OptionSelected) -> None:

self.current_recent_file = Path(event.option.prompt)

These event handlers use Textual’s handy @ondecorator, which allows you to bind the event to a specific widget or widgets.

on_open_xml_file()– If the user presses the “Open XML File” button, this method is called and it will show the file browser.on_open_recent_file()– If the user presses the “Open Recent” button, this method gets called and will load the selected recent file.on_recent_files_selected()– When the user selects a recent file in the OptionList widget, this method gets called and sets the current_recent_filevariable.You only have two more methods to go over. The first is for updating the recent files UI:

def update_recent_files_ui(self) -> None:if self.recent_files_path.exists():

self.recent_files.clear_options()

files = self.recent_files_path.read_text()

for file in files.split("\n"):

self.recent_files.add_option(file.strip())

Remember, this method gets called by on_mount()and it will update the OptionList, if the file exists. The first thing this code will do is clear the OptionList in preparation for updating it. Then you will read the text from the file and loop over each path in that file.

As you loop over the paths, you add them to the OptionList. That’s it! You now have a recent files list that the user can choose from.

The last method to write is for updating the recent files text file:

def update_recent_files_on_disk(self, path: Path) -> None:if path.exists() and self.recent_files_path.exists():

recent_files = self.recent_files_path.read_text()

if str(path) in recent_files:

return

with open(self.recent_files_path, mode="a") as f:

f.write(str(path) + "\n")

self.update_recent_files_ui()

elif not self.recent_files_path.exists():

with open(self.recent_files_path, mode="a") as f:

f.write(str(path) + "\n")

When the user opens a new XML file, you want to add that file to the recent file list on disk so that the next time the user opens your application, you can show the user the recent files. This is a nice way to make loading previous files much easier.

The code above will verify that the file still exists and that your recent files file also exists. Assuming that they do, you will check to see if the current XML file is already in the recent files file. If it is, you don’t want to add it again, so you return.

Otherwise, you open the recent files file in append mode, add the new file to disk and update the UI.

If the recent files file does not exist, you create it here and add the new path.

Here are the last few lines of code to add:

def main() -> None:app = BoomslangXML()

app.run()

if __name__ == "__main__":

main()

You create a main()function to create the Textual application object and run it. You do this primarily for making the application runnable by uv, Python’s fastest package installer and resolver.

Now you’re ready you move on and add some CSS styling to your UI.

Your XML editor doesn’t require extensive styling. In fact, there is nothing wrong with being minimalistic.

Open up your favorite IDE or text editor and create a new file named main.tcssand then add the following code:

BoomslangXML {#button_row {

align: center middle;

}

Horizontal{

height: auto;

}

OptionList {

border: solid green;

}

Button {

margin: 1;

}

}

Here you center the button row on your screen. You also set the Horizontalcontainer’s height to auto, which tells Textual to make the container fit its contents. You also add a border to your OptionListand a margin to your buttons.

The XML editor screen is fairly complex, so that’s what you will learn about next.

Creating the Edit XML ScreenThe XML editor screen is more complex than the main screen of your application and contains almost twice as many lines of code. But that’s to be expected when you realize that most of your logic will reside here.

As before, you will start out by writing the full code and then going over it piece-by-piece. Open up your Python IDE and create a new file named edit_xml_screen.pyand then enter the following code:

import lxml.etree as ETimport tempfile

from pathlib import Path

from .add_node_screen import AddNodeScreen

from .preview_xml_screen import PreviewXMLScreen

from textual import on

from textual.app import ComposeResult

from textual.containers import Horizontal, Vertical, VerticalScroll

from textual.screen import ModalScreen

from textual.widgets import Footer, Header, Input, Tree

from textual.widgets._tree import TreeNode

class DataInput(Input):

"""

Create a variant of the Input widget that stores data

"""

def __init__(self, xml_obj: ET.Element, *args, **kwargs) -> None:

super().__init__(*args, **kwargs)

self.xml_obj = xml_obj

class EditXMLScreen(ModalScreen):

BINDINGS = [

("ctrl+s", "save", "Save"),

("ctrl+a", "add_node", "Add Node"),

("p", "preview", "Preview"),

("escape", "esc", "Exit dialog"),

]

CSS_PATH = "edit_xml_screens.tcss"

def __init__(self, xml_path: Path, *args, **kwargs):

super().__init__(*args, **kwargs)

self.xml_tree = ET.parse(xml_path)

self.expanded = {}

self.selected_tree_node: None | TreeNode = None

def compose(self) -> ComposeResult:

xml_root = self.xml_tree.getroot()

self.expanded[id(xml_root)] = ""

yield Header()

yield Horizontal(

Vertical(Tree("No Data Loaded", id="xml_tree"), id="left_pane"),

VerticalScroll(id="right_pane"),

id="main_ui_container",

)

yield Footer()

def on_mount(self) -> None:

self.load_tree()

@on(Tree.NodeExpanded)

def on_tree_node_expanded(self, event: Tree.NodeExpanded) -> None:

"""

When a tree node is expanded, parse the newly shown leaves and make

them expandable, if necessary.

"""

xml_obj = event.node.data

if id(xml_obj) not in self.expanded and xml_obj is not None:

for top_level_item in xml_obj.getchildren():

child = event.node.add_leaf(top_level_item.tag, data=top_level_item)

if top_level_item.getchildren():

child.allow_expand = True

else:

child.allow_expand = False

self.expanded[id(xml_obj)] = ""

@on(Tree.NodeSelected)

def on_tree_node_selected(self, event: Tree.NodeSelected) -> None:

"""

When a node in the tree control is selected, update the right pane to show

the data in the XML, if any

"""

xml_obj = event.node.data

right_pane = self.query_one("#right_pane", VerticalScroll)

right_pane.remove_children()

self.selected_tree_node = event.node

if xml_obj is not None:

for child in xml_obj.getchildren():

if child.getchildren():

continue

text = child.text if child.text else ""

data_input = DataInput(child, text)

data_input.border_title = child.tag

container = Horizontal(data_input)

right_pane.mount(container)

else:

# XML object has no children, so just show the tag and text

if getattr(xml_obj, "tag") and getattr(xml_obj, "text"):

if xml_obj.getchildren() == []:

data_input = DataInput(xml_obj, xml_obj.text)

data_input.border_title = xml_obj.tag

container = Horizontal(data_input)

right_pane.mount(container)

@on(Input.Changed)

def on_input_changed(self, event: Input.Changed) -> None:

"""

When an XML element changes, update the XML object

"""

xml_obj = event.input.xml_obj

# self.notify(f"{xml_obj.text} is changed to new value: {event.input.value}")

xml_obj.text = event.input.value

def action_esc(self) -> None:

"""

Close the dialog when the user presses ESC

"""

self.dismiss()

def action_add_node(self) -> None:

"""

Add another node to the XML tree and the UI

"""

# Show dialog and use callback to update XML and UI

def add_node(result: tuple[str, str] | None) -> None:

if result is not None:

node_name, node_value = result

self.update_xml_tree(node_name, node_value)

self.app.push_screen(AddNodeScreen(), add_node)

def action_preview(self) -> None:

temp_directory = Path(tempfile.gettempdir())

xml_path = temp_directory / "temp.xml"

self.xml_tree.write(xml_path)

self.app.push_screen(PreviewXMLScreen(xml_path))

def action_save(self) -> None:

self.xml_tree.write(r"C:\Temp\books.xml")

self.notify("Saved!")

def load_tree(self) -> None:

"""

Load the XML tree UI with data parsed from the XML file

"""

tree = self.query_one("#xml_tree", Tree)

xml_root = self.xml_tree.getroot()

self.expanded[id(xml_root)] = ""

tree.reset(xml_root.tag)

tree.root.expand()

# If the root has children, add them

if xml_root.getchildren():

for top_level_item in xml_root.getchildren():

child = tree.root.add(top_level_item.tag, data=top_level_item)

if top_level_item.getchildren():

child.allow_expand = True

else:

child.allow_expand = False

def update_tree_nodes(self, node_name: str, node: ET.SubElement) -> None:

"""

When adding a new node, update the UI Tree element to reflect the new element added

"""

child = self.selected_tree_node.add(node_name, data=node)

child.allow_expand = False

def update_xml_tree(self, node_name: str, node_value: str) -> None:

"""

When adding a new node, update the XML object with the new element

"""

element = ET.SubElement(self.selected_tree_node.data, node_name)

element.text = node_value

self.update_tree_nodes(node_name, element)

Phew! That seems like a lot of code if you are new to coding, but a hundred and seventy lines of code or so really isn’t very much. Most applications take thousands of lines of code.

Just the same, breaking the code down into smaller chunks will aid in your understanding of what’s going on.

With that in mind, here’s the first chunk:

import lxml.etree as ETimport tempfile

from pathlib import Path

from .add_node_screen import AddNodeScreen

from .preview_xml_screen import PreviewXMLScreen

from textual import on

from textual.app import ComposeResult

from textual.containers import Horizontal, Vertical, VerticalScroll

from textual.screen import ModalScreen

from textual.widgets import Footer, Header, Input, Tree

from textual.widgets._tree import TreeNode

You have move imports here than you did in the main UI file. Here’s a brief overview:

You import lxml to make parsing and editing XML easy.You use Python’s tempfilemodule to create a temporary file for viewing the XML.The pathlibmodule is used the same way as before.You have a couple of custom Textual screens that you will need to code up and import.The last six lines are all Textual imports for making this editor screen work.The next step is to subclass the Inputwidget in such a way that it will store XML element data:

class DataInput(Input):"""

Create a variant of the Input widget that stores data

"""

def __init__(self, xml_obj: ET.Element, *args, **kwargs) -> None:

super().__init__(*args, **kwargs)

self.xml_obj = xml_obj

Here you pass in an XML object and store it off in an instance variable. You will need this to make editing and displaying the XML easy.

The second class you create is the EditXMLScreen:

class EditXMLScreen(ModalScreen):BINDINGS = [

("ctrl+s", "save", "Save"),

("ctrl+a", "add_node", "Add Node"),

("p", "preview", "Preview"),

("escape", "esc", "Exit dialog"),

]

CSS_PATH = "edit_xml_screens.tcss"

def __init__(self, xml_path: Path, *args, **kwargs):

super().__init__(*args, **kwargs)

self.xml_tree = ET.parse(xml_path)

self.expanded = {}

self.selected_tree_node: None | TreeNode = None

The EditXMLScreenis a new screen that holds your XML editor. Here you add four keyboard bindings, a CSS file path and the __init__()method.

Your initialization method is used to create an lxml Element Tree instance. You also create an empty dictionary of expanded tree widgets and the selected tree node instance variable, which is set to None.

Now you’re ready to create your user interface:

def compose(self) -> ComposeResult:xml_root = self.xml_tree.getroot()

self.expanded[id(xml_root)] = ""

yield Header()

yield Horizontal(

Vertical(Tree("No Data Loaded", id="xml_tree"), id="left_pane"),

VerticalScroll(id="right_pane"),

id="main_ui_container",

)

yield Footer()

def on_mount(self) -> None:

self.load_tree()

Fortunately, the user interface needed for editing XML is fairly straightforward:

You create a new header to add a new title to the screen.You use a horizontally-oriented container to hold your widgets.Inside of the container, you have a tree control that holds the DOM of the XML on the left.On the right, you have a vertical scrolling container.Finally, you have a footerYou also set up the first item in your “expanded” dictionary, which is the root node from the XML.

Now you can write your first event handler for this class:

@on(Tree.NodeExpanded)def on_tree_node_expanded(self, event: Tree.NodeExpanded) -> None:

"""

When a tree node is expanded, parse the newly shown leaves and make

them expandable, if necessary.

"""

xml_obj = event.node.data

if id(xml_obj) not in self.expanded and xml_obj is not None:

for top_level_item in xml_obj.getchildren():

child = event.node.add_leaf(top_level_item.tag, data=top_level_item)

if top_level_item.getchildren():

child.allow_expand = True

else:

child.allow_expand = False

self.expanded[id(xml_obj)] = ""

When the user expands a node in the tree control, the on_tree_node_expanded()method will get called. You will extract the node’s data, if it has any. Assuming that there is data, you will then loop over any child nodes that are present.

For each child node, you will add a new leaf to the tree control. You check to see if the child has children too and set the allow_expandflag accordingly. At the end of the code, you add then XML object to your dictionary.

The next method you need to write is an event handler for when a tree node is selected:

@on(Tree.NodeSelected)def on_tree_node_selected(self, event: Tree.NodeSelected) -> None:

"""

When a node in the tree control is selected, update the right pane to show

the data in the XML, if any

"""

xml_obj = event.node.data

right_pane = self.query_one("#right_pane", VerticalScroll)

right_pane.remove_children()

self.selected_tree_node = event.node

if xml_obj is not None:

for child in xml_obj.getchildren():

if child.getchildren():

continue

text = child.text if child.text else ""

data_input = DataInput(child, text)

data_input.border_title = child.tag

container = Horizontal(data_input)

right_pane.mount(container)

else:

# XML object has no children, so just show the tag and text

if getattr(xml_obj, "tag") and getattr(xml_obj, "text"):

if xml_obj.getchildren() == []:

data_input = DataInput(xml_obj, xml_obj.text)

data_input.border_title = xml_obj.tag

container = Horizontal(data_input)

right_pane.mount(container)

Wben the user selects a node in your tree, you need to update the righthand pane with the node’s contents. To do that, you once again extract the node’s data, if it has any. If it does have data, you loop over its children and update the right hand pane’s UI. This entails grabbing the XML node’s tags and values and adding a series of horizontal widgets to the scrollable container that makes up the right pane of your UI.

If the XML object has no children, you can simply show the top level node’s tag and value, if it has any.

The next two methods you will write are as follows:

@on(Input.Changed)def on_input_changed(self, event: Input.Changed) -> None:

"""

When an XML element changes, update the XML object

"""

xml_obj = event.input.xml_obj

xml_obj.text = event.input.value

def on_save_file_dialog_dismissed(self, xml_path: str) -> None:

"""

Save the file to the selected location

"""

if not Path(xml_path).exists():

self.xml_tree.write(xml_path)

self.notify(f"Saved to: {xml_path}")

The on_input_changed() method deals with Inputwidgets which are your special DataInputwidgets. Whenever they are edited, you want to grab the XML object from the event and update the XML tag’s value accordingly. That way, the XML will always be up-to-date if the user decides they want to save it.

You can also add an auto-save feature which would also use the latest XML object when it is saving, if you wanted to.

The second method here, on_save_file_dialog_dismissed(), is called when the user dismisses the save dialog that is opened when the user presses CTRL+S. Here you check to see if the file already exists. If not, you create it. You could spend some time adding another dialog here that warns that a file exists and gives the option to the user whether or not to overwrite it.

Anyway, your next step is to write the keyboard shortcut action methods. There are four keyboard shortcuts that you need to create actions for.

Here they are:

def action_esc(self) -> None:"""

Close the dialog when the user presses ESC

"""

self.dismiss()

def action_add_node(self) -> None:

"""

Add another node to the XML tree and the UI

"""

# Show dialog and use callback to update XML and UI

def add_node(result: tuple[str, str] | None) -> None:

if result is not None:

node_name, node_value = result

self.update_xml_tree(node_name, node_value)

self.app.push_screen(AddNodeScreen(), add_node)

def action_preview(self) -> None:

temp_directory = Path(tempfile.gettempdir())

xml_path = temp_directory / "temp.xml"

self.xml_tree.write(xml_path)

self.app.push_screen(PreviewXMLScreen(xml_path))

def action_save(self) -> None:

self.app.push_screen(SaveFileDialog(), self.on_save_file_dialog_dismissed)

The four keyboard shortcut event handlers are:

action_esc()– Called when the user pressed the “Esc” key. Exits the dialog.action_add_node()– Called when the user presses CTRL+A. Opens the AddNodeScreen. If the user adds new data, the add_node()callback is called, which will then call update_xml_tree()to update the UI with the new information.action_preview()– Called when the user presses the “p” key. Creates a temporary file with the current contents of the XML object. Then opens a new screen that allows the user to view the XML as a kind of preview.action_save– Called when the user presses CTRL+S.The next method you will need to write is called load_tree():

def load_tree(self) -> None:"""

Load the XML tree UI with data parsed from the XML file

"""

tree = self.query_one("#xml_tree", Tree)

xml_root = self.xml_tree.getroot()

self.expanded[id(xml_root)] = ""

tree.reset(xml_root.tag)

tree.root.expand()

# If the root has children, add them

if xml_root.getchildren():

for top_level_item in xml_root.getchildren():

child = tree.root.add(top_level_item.tag, data=top_level_item)

if top_level_item.getchildren():

child.allow_expand = True

else:

child.allow_expand = False

The method above will grab the Treewidget and the XML’s root element and then load the tree widget with the data. You check if the XML root object has any children (which most do) and then loop over the children, adding them to the tree widget.

You only have two more methods to write. Here they are:

def update_tree_nodes(self, node_name: str, node: ET.SubElement) -> None:"""

When adding a new node, update the UI Tree element to reflect the new element added

"""

child = self.selected_tree_node.add(node_name, data=node)

child.allow_expand = False

def update_xml_tree(self, node_name: str, node_value: str) -> None:

"""

When adding a new node, update the XML object with the new element

"""

element = ET.SubElement(self.selected_tree_node.data, node_name)

element.text = node_value

self.update_tree_nodes(node_name, element)

These two methods are short and sweet:

update_tree_nodes() – When the user adds a new node, you call this method which will update the node in the tree widget as needed.update_xml_tree() – When a node is added, update the XML object and then call the UI updater method above.The last piece of code you need to write is the CSS for this screen. Open up a text editor and create a new file called edit_xml_screens.tcss and then add the following code:

EditXMLScreen {Input {

border: solid gold;

margin: 1;

height: auto;

}

Button {

align: center middle;

}

Horizontal {

margin: 1;

height: auto;

}

}

This CSS is similar to the other CSS file. In this case, you set the Input widget’s height to auto. You also set the margin and border for that widget. For the buttons, you tell Textual to center all of them. Finally, you also set the margin and height of the horizontal container, just like you did in the other CSS file.

Now you are ready to learn about the add node screen!

The Add Node ScreenWhen the user wants to add a new node to the XML, you will show an “add node screen”. This screen allows the user to enter a node (i.e., tag) name and value. The screen will then pass that new data to the callback which will update the XML object and the user interface. You have already seen that code in the previous section.

To get started, open up a new file named add_node_screen.pyand enter the following code:

from textual import onfrom textual.app import ComposeResult

from textual.containers import Horizontal, Vertical

from textual.screen import ModalScreen

from textual.widgets import Button, Header, Footer, Input

class AddNodeScreen(ModalScreen):

BINDINGS = [

("escape", "esc", "Exit dialog"),

]

CSS_PATH = "add_node_screen.tcss"

def __init__(self, *args, **kwargs):

super().__init__(*args, **kwargs)

self.title = "Add New Node"

def compose(self) -> ComposeResult:

self.node_name = Input(id="node_name")

self.node_name.border_title = "Node Name"

self.node_value = Input(id="node_value")

self.node_value.border_title = "Node Value"

yield Vertical(

Header(),

self.node_name,

self.node_value,

Horizontal(

Button("Save Node", variant="primary", id="save_node"),

Button("Cancel", variant="warning", id="cancel_node"),

),

Footer(),

id="add_node_screen_ui",

)

@on(Button.Pressed, "#save_node")

def on_save(self) -> None:

self.dismiss((self.node_name.value, self.node_value.value))

@on(Button.Pressed, "#cancel_node")

def on_cancel(self) -> None:

self.dismiss()

def action_esc(self) -> None:

"""

Close the dialog when the user presses ESC

"""

self.dismiss()

Following is an overview of each method of the code above:

__init__()– Sets the title of the screen.compose()– Creates the user interface, which is made up of two Inputwidgets, a “Save” button, and a “Cancel” button.on_save()-Called when the user presses the “Save” button. This will save the data entered by the user into the two inputs, if any.on_cancel()– Called when the user presses the “Cancel” button. If pressed, the screen exits without saving.action_esc()– Called when the user presses the “Esc” key. If pressed, the screen exits without saving.That code is concise and straightforward.

Next, open up a text editor or use your IDE to create a file named add_node_screen.tcsswhich will contain the following CSS:

AddNodeScreen {align: center middle;

background: $primary 30%;

#add_node_screen_ui {

width: 80%;

height: 40%;

border: thick $background 70%;

content-align: center middle;

margin: 2;

}

Input {

border: solid gold;

margin: 1;

height: auto;

}

Button {

margin: 1;

}

Horizontal{

height: auto;

align: center middle;

}

}

Your CSS functions as a way to quickly style individual widgets or groups of widgets. Here you set it up to make the screen a bit smaller than the screen underneath it (80% x 40%) so it looks like a dialog.

You set the border, height, and margin on your inputs. You add a margin around your buttons to keep them slightly apart. Finally, you add a height and alignment to the container.

You can try tweaking all of this to see how it changes the look and feel of the screen. It’s a fun way to explore, and you can do this with any of the screens you create.

The next screen to create is the XML preview screen.

Adding an XML Preview ScreenThe XML Preview screen allows the user to check that the XML looks correct before they save it. Textual makes creating a preview screen short and sweet.

Open up your Python IDE and create a new file named preview_xml_screen.pyand then enter the following code into it:

from textual import onfrom textual.app import ComposeResult

from textual.containers import Center, Vertical

from textual.screen import ModalScreen

from textual.widgets import Button, Header, TextArea

class PreviewXMLScreen(ModalScreen):

CSS_PATH = "preview_xml_screen.tcss"

def __init__(self, xml_file_path: str, *args: tuple, **kwargs: dict) -> None:

super().__init__(*args, **kwargs)

self.xml_file_path = xml_file_path

self.title = "Preview XML"

def compose(self) -> ComposeResult:

with open(self.xml_file_path) as xml_file:

xml = xml_file.read()

text_area = TextArea(xml)

text_area.language = "xml"

yield Header()

yield Vertical(

text_area,

Center(Button("Exit Preview", id="exit_preview", variant="primary")),

id="exit_preview_ui",

)

@on(Button.Pressed, "#exit_preview")

def on_exit_preview(self, event: Button.Pressed) -> None:

self.dismiss()

There’s not a lot here, so you will go over the highlights like you did in the previous section:

__init__()– Initializes a couple of instance variables:xml_file_path– Which is a temporary file pathtitle– The title of the screencompose()– The UI is created here. You open the XML file and read it in. Then you load the XML into a TextAreawidget. Finally, you tell Textual to use a header, the text area widget and an exit button for your interface.on_exit_preview()– Called when the user presses the “Exit Preview” button. As the name implies, this exits the screen.The last step is to apply a little CSS. Create a new file named preview_xml_screen.tcssand add the following snippet to it:

PreviewXMLScreen {Button {

margin: 1;

}

}

All this CSS does is add a margin to the button, which makes the UI look a little nicer.

There are three more screens yet to write. The first couple of screens you will create are the file browser and warning screens.

Creating the File Browser and Warning ScreensThe file browser is what the user will use to find an XML file that they want to open. It is also nice to have a screen you can use for warnings, so you will create that as well.

For now, you will call this file file_browser_screen.pybut you are welcome to separate these two screens into different files. The first half of the file will contain the imports and the WarningScreenclass.

Here is that first half:

from pathlib import Pathfrom textual import on

from textual.app import ComposeResult

from textual.containers import Center, Grid, Vertical

from textual.message import Message

from textual.screen import Screen

from textual.widgets import Button, DirectoryTree, Footer, Label, Header

class WarningScreen(Screen):

"""

Creates a pop-up Screen that displays a warning message to the user

"""

def __init__(self, warning_message: str) -> None:

super().__init__()

self.warning_message = warning_message

def compose(self) -> ComposeResult:

"""

Create the UI in the Warning Screen

"""

yield Grid(

Label(self.warning_message, id="warning_msg"),

Button("OK", variant="primary", id="ok_warning"),

id="warning_dialog",

)

def on_button_pressed(self, event: Button.Pressed) -> None:

"""

Event handler for when the OK button - dismisses the screen

"""

self.dismiss()

event.stop()

The warning screen is made up of two widgets: a label that contains the warning message and an “OK” button. You also add a method to respond to the buton being pressed. You dismiss the screen here and stop the event from propagating up to the parent.

The next class you need to add to this file is the FileBrowserclass:

class FileBrowser(Screen):BINDINGS = [

("escape", "esc", "Exit dialog"),

]

CSS_PATH = "file_browser_screen.tcss"

class Selected(Message):

"""

File selected message

"""

def __init__(self, path: Path) -> None:

self.path = path

super().__init__()

def __init__(self) -> None:

super().__init__()

self.selected_file = Path("")

self.title = "Load XML Files"

def compose(self) -> ComposeResult:

yield Vertical(

Header(),

DirectoryTree("/"),

Center(

Button("Load File", variant="primary", id="load_file"),

),

id="file_browser_dialog",

)

@on(DirectoryTree.FileSelected)

def on_file_selected(self, event: DirectoryTree.FileSelected) -> None:

"""

Called when the FileSelected Message is emitted from the DirectoryTree

"""

self.selected_file = event.path

def on_button_pressed(self, event: Button.Pressed) -> None:

"""

Event handler for when the load file button is pressed

"""

event.stop()

if self.selected_file.suffix.lower() != ".xml" and self.selected_file.is_file():

self.app.push_screen(WarningScreen("ERROR: You must choose a XML file!"))

return

self.post_message(self.Selected(self.selected_file))

self.dismiss()

def action_esc(self) -> None:

"""

Close the dialog when the user presses ESC

"""

self.dismiss()

The FileBrowserclass is more complicated because it does a lot more than the warning screen does. Here’s a listing of the methods:

__init__()– Initializes the currently selected file to an empty path and sets the title for the screen.compose()– Creates the UI. This UI has a header, a DirectoryTreefor browsing files and a button for loading the currently selected file.on_file_selected()– When the user selected a file in the directory tree, you grab the path and set the selected_fileinstance variable.on_button_pressed()– When the user presses the “Load File” button, you check if the selected file is the correct file type. If not, you should a warning screen. If the file is an XML file, then you post a custom message and close the screen.action_esc()– Called when the user presses the Esckey. Closes the screen.The last item to write is your CSS file. As you might expect, you should name it file_browser_screen.tcss. Then put the following CSS inside of the file:

FileBrowser {#file_browser_dialog {

width: 80%;

height: 50%;

border: thick $background 70%;

content-align: center middle;

margin: 2;

border: solid green;

}

Button {

margin: 1;

content-align: center middle;

}

}

The CSS code here should look pretty familiar to you. All you are doing is making the screen look like a dialog and then adding a margin and centering the button.

The last step is to create the file save screen.

Creating the File Save ScreenThe file save screen is similar to the file browser screen with the main difference being that you are supplying a new file name that you want to use to save your XML file to.

Open your Python IDE and create a new file called save_file_dialog.pyand then enter the following code:

from pathlib import Pathfrom textual import on

from textual.app import ComposeResult

from textual.containers import Vertical

from textual.screen import Screen

from textual.widgets import Button, DirectoryTree, Footer, Header, Input, Label

class SaveFileDialog(Screen):

CSS_PATH = "save_file_dialog.tcss"

def __init__(self) -> None:

super().__init__()

self.title = "Save File"

self.root = "/"

def compose(self) -> ComposeResult:

yield Vertical(

Header(),

Label(f"Folder name: {self.root}", id="folder"),

DirectoryTree("/"),

Input(placeholder="filename.txt", id="filename"),

Button("Save File", variant="primary", id="save_file"),

id="save_dialog",

)

def on_mount(self) -> None:

"""

Focus the input widget so the user can name the file

"""

self.query_one("#filename").focus()

def on_button_pressed(self, event: Button.Pressed) -> None:

"""

Event handler for when the load file button is pressed

"""

event.stop()

filename = self.query_one("#filename").value

full_path = Path(self.root) / filename

self.dismiss(f"{full_path}")

@on(DirectoryTree.DirectorySelected)

def on_directory_selection(self, event: DirectoryTree.DirectorySelected) -> None:

"""

Called when the DirectorySelected message is emitted from the DirectoryTree

"""

self.root = event.path

self.query_one("#folder").update(f"Folder name: {event.path}")

The save file dialog code is currently less than fifty lines of code. Here is a breakdown of that code:

__init__()– Sets the title of the screen and the default root folder.compose()– Creates the user interface, which consists of a header, a label (the root), the directory tree widget, an input for specifying the file name, and a “Save File” button.on_mount()– Called automatically by Textual after the compose()method. Sets the input widget as the focus.on_button_pressed()– Called when the user presses the “Save File” button. Grabs the filename and then create the full path using the root + filename. Finally, you send that full path back to the callback function via dismiss().on_directory_selection()– Called when the user selects a directory. Updates the rootvariable to the selected path as well as updates the label so the user knows which path is selected.The last item you need to write is the CSS file for this dialog. You will need to name the file save_file_dialog.tcssand then add this code:

SaveFileDialog {#save_dialog {

width: 80%;

height: 50%;

border: thick $background 70%;

content-align: center middle;

margin: 2;

border: solid green;

}

Button {

margin: 1;

content-align: center middle;

}

}

The CSS code above is almost identical to the CSS you used for the file browser code.

When you run the TUI, you should see something like the following demo GIF:

You have now created a basic XML editor and viewer using Python and Textual. There are lots of little improvements that you can add to this code. However, those updates are up to you to make.

Have fun working with Textual and create something new or contribute to a neat Textual project yourself!

Get the CodeThe code in this tutorial is based on version 0.2.0 of BoomslangXML TUI. You can download the code from GitHub or from the following links:

Source code (zip)The post Creating a Simple XML Editor in Your Terminal with Python and Textual appeared first on Mouse Vs Python.

July 18, 2025

Announcing Squall: A TUI SQLite Editor

Squall is a SQLite viewer and editor that runs in your terminal. Squall is written in Python and uses the Textual package. Squall allows you to view and edit SQLite databases using SQL. You can check out the code on GitHub.

ScreenshotsHere is what Squall looks like using the Chinook database:

Currently, there is only one command-line option: -f or --filename, which allows you to pass a database path to Squall to load.

Example Usage:

squall -f path/to/database.sqlite

PrerequisitesThe instructions assume you have uv or pip installed.

InstallationPyPiuv tool install squall_sql

Using uv on GitHubuv tool install git+https://github.com/driscollis/squall

Update the InstallationIf you want to upgrade to the latest version of Squall SQL, then you will want to run one of the following commands.

Using uv on GitHubuv tool install git+https://github.com/driscollis/squall -U --force

Installing Using pippip install squall-sql

Running Squall from SourceIf you have cloned the package and want to run Squall, one way to do so is to navigate to the cloned repository on your hard drive using your Terminal. Then run the following command while inside the src folder:

python -m squall.squall

The post Announcing Squall: A TUI SQLite Editor appeared first on Mouse Vs Python.

July 16, 2025

An Intro to Asciimatics – Another Python TUI Package

Text-based user interfaces (TUIs) have gained significant popularity in recent years. Even Rust has its own library called Ratatui after all. Python has several different TUI packages to choose from. One of those packages is called Asciimatics.

While Asciimatics is not as full-featured and slick as Textual is, you can do quite a bit with Asciimatics. In fact, there is a special kind of charm to the old-school flavor of the TUIs that you can create using Asciimatics.

In this tutorial, you will learn the basics of Asciimatics:

InstallationCreating a Hello World applicationCreating a formThe purpose of this tutorial is not to be exhaustive, but to give you a sense of how easy it is to create a user interface with Asciimatics. Be sure to read the complete documentation and check out their examples to learn more.

For now, let’s get started!

InstallationAsciimatics is a third-party Python package. What that means is that Asciimatics is not included with Python. You will need to install it. You should use a Python virtual environment for installing packages or creating new applications.

Whether you use the virtual environment or not, you can use pip to install Asciimatics:

python -m pip install asciimaticsOnce Asciimatics is installed, you can proceed to creating a Hello World application.

Creating a Hello World ApplicationCreating a simple application is a concrete way to learn how to use an unfamiliar package. You will create a fun little application that “prints” out “Hello from Asciimatics” multiple times and in multiple colors.

Open up your favorite Python IDE or text editor and create a new file called hello_asciimatics.py and then add the following code to it:

from random import randintfrom asciimatics.screen import Screen

def hello(screen: Screen):

while True:

screen.print_at("Hello from ASCIIMatics",

randint(0, screen.width), randint(0, screen.height),

colour=randint(0, screen.colours - 1),

bg=randint(0, screen.colours - 1)

)

key = screen.get_key()

if key in (ord("Q"), ord("q")):

return

screen.refresh()

Screen.wrapper(hello)

This codfe takes in an Asciimatics Screen object. You draw your text on the screen. In this case, you use the screen’s print_at() method to draw the text. You use Python’s handy random module to choose random coordinates in your terminal to draw the text as well as choose random foreground and background colors.

You run this inside an infinite loop. Since the loop runs indefinitely, the text will be drawn all over the screen and over the top of previous iterations of the text. What that means is that you should see the same text over and over again, getting written on top of previous versions of the text.

If the user presses the “Q” button on their keyboard, the application will break out of the loop and exit.

When you run this code, you should see something like this:

Isn’t that neat? Give it a try on your machine and verify that it works.

Now you are ready to create a form!

Creating a FormWhen you want to ask the user for some information, you will usually use a form. You will find that this is true in web, mobile and desktop applications.

To make this work in Asciimatics, you will need to create a way to organize your widgets. To do that, you create a Layoutobject. You will find that Asciimatics follow an hierarchy of Screen -> Scene -> Effects and then layouts and widgets.

All of this is kind of abstract though. So it make this easier to understand, you will write some code. Open up your Python IDE and create another new file. Name this new file ascii_form.pyand then add this code to it:

import sysfrom asciimatics.exceptions import StopApplication

from asciimatics.scene import Scene

from asciimatics.screen import Screen

from asciimatics.widgets import Frame, Button, Layout, Text

class Form(Frame):

def __init__(self, screen):

super().__init__(screen,

screen.height * 2 // 3,

screen.width * 2 // 3,

hover_focus=True,

can_scroll=False,

title="Contact Details",

reduce_cpu=True)

layout = Layout([100], fill_frame=True)

self.add_layout(layout)

layout.add_widget(Text("Name:", "name"))

layout.add_widget(Text("Address:", "address"))

layout.add_widget(Text("Phone number:", "phone"))

layout.add_widget(Text("Email address:", "email"))

button_layout = Layout([1, 1, 1, 1])

self.add_layout(button_layout)

button_layout.add_widget(Button("OK", self.on_ok), 0)

button_layout.add_widget(Button("Cancel", self.on_cancel), 3)

self.fix()

def on_ok(self):

print("User pressed OK")

def on_cancel(self):

sys.exit(0)

raise StopApplication("User pressed cancel. Quitting!")

def main(screen: Screen):

while True:

scenes = [

Scene([Form(screen)], -1, name="Main Form")

]

screen.play(scenes, stop_on_resize=True, start_scene=scenes[0], allow_int=True)

Screen.wrapper(main, catch_interrupt=True)

The Form is a subclass of Frame which is an Effect in Asciimatics. In this case, you can think of the frame as a kind of window or dialog within your terminal.

The frame will contain your form. Within the frame, you create a Layoutobject and you tell it to fill the frame. Next you add the widgets to the layout, which will add the widgets vertically, from top to bottom.

Then you create a second layout to hold two buttons: “OK” and “Cancel”. The second layout is defined as having four columns with a size of one. You will then add the buttons and specify which column the button should be put in.

To show the frame to the user, you add the frame to a Scene and then you play() it.

When you run this code, you should see something like the following:

Pretty neat, eh?

Now this example is great for demonstrating how to create a more complex user interface, but it doesn’t show how to get the data from the user as you haven’t written any code to grab the contents of the Text widgets. However, you did show that when you created the buttons, you can bind them to specific methods that get called when the user clicks on those buttons.

Wrapping UpAsciimatics makes creating simple and complex applications for your terminal easy. However, the applications have a distincly retro-look to them that is reminiscent to the 1980’s or even earlier. The applications are appealing in their own way, though.

This tutorial only scratches the surface of Asciimatics. For full details, you should check out their documentation.

If you wamt to create a more modern looking user interface, you might want to check out Textual instead.

Related ReadingWant to learn how to create TUIs the modern way? Check out my book: Creating TUI Applications with Textual and Python.

Available at the following:

Amazon (Kindle and Paperback)Leanpub (eBook)Gumroad (eBook)

The post An Intro to Asciimatics – Another Python TUI Package appeared first on Mouse Vs Python.

July 15, 2025

Creating TUI Applications with Textual and Python is Released

Learn how to create text-based user interfaces (TUIs) using Python and the amazing Textual package.

Textual is a rapid application development framework for your terminal or web browser. You can build complex, sophisticated applications in your terminal. While terminal applications are text-based rather than pixel-based, they still provide fantastic user interfaces.

The Textual package allows you to create widgets in your terminal that mimic those used in a web or GUI application.

Creating TUI Applications with Textual and Python is to teach you how to use Textual to make striking applications of your own. The book’s first half will teach you everything you need to know to develop a terminal application.

The book’s second half has many small applications you will learn how to create. Each chapter also includes challenges to complete to help cement what you learn or give you ideas for continued learning.

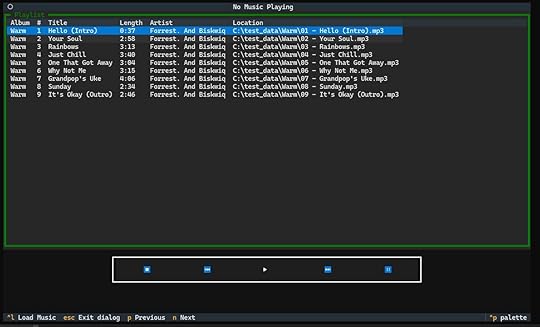

Here are some of the applications you will create:

A basic calculatorA CSV viewerA Text EditorAn MP3 playerAn ID3 EditorA Weather applicationA TUI for pre-commitRSS ReaderWhere to Buy

You can purchase Creating TUI Applications with Textual and Python on the following websites:

Amazon (Kindle and Paperback)Leanpub (eBook)Gumroad (eBook)Calculator

The post Creating TUI Applications with Textual and Python is Released appeared first on Mouse Vs Python.

July 3, 2025

Python eBook Fourth of July Sale

Happy Fourth of July! I am hosting a sale for the 4th of July weekend, where you can get 25% off most of my books and courses.

Here are the books included in the sale and the direct links with the 25% coupon already applied:

Python 101Python 201: Intermediate PythonReportLab: PDF Processing in PythonJupyter Notebook 101Creating GUI Applications with wxPythonPillow: Image Processing with PythonAutomating Excel with PythonThe Python Quiz BookPython LoggingJupyterLab 101I hope you’ll check out the sale, but even if you don’t, I hope you have a great holiday weekend!

The post Python eBook Fourth of July Sale appeared first on Mouse Vs Python.