Yashas Mahajan's Blog, page 38

August 1, 2017

Word of the Week #70:

As a kid, I was usually quite well liked by elders. You see, I have always been nice and cute and smart. People tend to like that in kids.

However, as I grew older and smarter, I found that there were a couple of aspect of my personality that seemed to prick certain grown-ups.

You see, I was always an inquisitive kid. When someone would tell me something, or ask me to do something a certain way, I thought a very reasonable response was, “Why?”

At that age, it is bizarre to think I would not have actually intended to challenge the authority of the aforementioned elders. What kid ever thinks that way?

Now, as a few more years passed, this habit of mine evolved to the next level.

Now, not only was I completely unafraid of asking “Why?”, I was also assertive enough in the face of their floundering responses to say, “No.”

Needless to say, such behaviour was not without its consequences. Some teachers may have been convinced this disobedience needed to be flogged out of me, but corporal punishments were not in vogue anymore, and juvenile attempts at public shaming had to suffice. Some parents believed I was a bad influence on their kids.

I have always hoped people would look at this with equanimity and ask themselves who is a worse influence on impressionable minds: a child who seeks to understand before he obeys, and thereby chooses to disobey if he disagrees, or a supposed ‘grown-up’ who cannot even defend his beliefs to the aforementioned child, and thereby sees him as a threat.

“Inevitably it follows that anyone with an independent mind must become ‘one who resists or opposes an authority or established convention’: a rebel…

And if enough people come to agree with—and follow—the REBEL, we now have a DEVIL.

Until, of course, still more people agree. And then, finally, we have… GREATNESS.”

― Nicholas Tharcher, Rebels and Devils: The Psychology of Liberation

The times have changed, since. We are the grown-ups now. It is time for us to shape the world we have inherited.

“Silence becomes cowardice when occasion demands speaking out the whole truth and acting accordingly.”

― Mahatma Gandhi

Do we want our children to stay silent, or do we want them to speak out?

It is now for us to decide.

July 25, 2017

Word of the Week #69:

So, this past week has hurtled by, as I have been forced to just sit and watch; not that I was particularly ill or anything of that sort, of course. When am I not ill, anyway…

Nah, I guess there are just some weeks like this one.

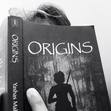

It is, however, disconcerting when we consider the fact that the end of the contract with my current publisher is no longer at the horizon—it is now very much in the forefront—and I have barely begun working on the editing and rewriting required to prepare the second edition of Book One.

I will admit, as have many readers already observed, that the first edition could have used a little more time and work than it was afforded. Well, I am wiser now.

To write is human, to edit is divine.

—Stephen King

Add to that the fact that the manuscript of Book Two is still not quite completely ready and one can very well begun to hyperventilate.

Quite honestly, this is one of those few instances where the word ‘deadline’ could literally be true.

But, as I keep proving to myself more than to anyone else, I am made of sterner stuff than that. Moreover, it have always found it easier to concentrate on a task when it begins to seem, to an uninitiated onlooker, overwhelming.

If everything seems under control, you’re just not going fast enough.

—Mario Andretti

So, now that the going has gotten tough, it is time for me to get going.

Au revoir.

July 18, 2017

Word of the Week #68:

Even as I write this, I can hear the clouds rumbling in the background, as the storm comes rolling over from, presumably, the Bay of Bengal.

In stark contrast to Western Literature, which has largely portrayed storms and rains as being dreary and foreboding at best, folk culture closer home has had more favourable response. And, of course, one need not look too far to understand the reasons behind the same.

You see, living in a tropical peninsula almost entirely reliant on the monsoons for survival pretty much guarantees a positive reaction upon the arrival of the rains.

Sure, a couple of weeks in, as we now are, we might sit indoors grumbling about the muddy roads and the stinky shirts and the recurrent network troubles, and the possibilities of going outdoors that might have existed, but for the weather, and yet you will have to admit: You did smile when the scent of the moist earth first wafted into your homes.

It is only fair, I would say. The love for the rain, it is a part of our heritage.

And now that the storm is breaking, what more can we do, but sit indoors with an Agatha Christie in one hand and a warm snack in the other… Really, what more do you need?

July 11, 2017

Word of the Week #67:

It has always been my conviction that the human mind does not appreciate blank spaces; the ones it cannot fill with truth, it fills with tripe.

And no, I am not talking about haggis…

For instance, the concept of atmospheric pressure was not known to mankind till at least 1640AD, and not correctly understood until 1648AD. How, then, does one explain wind? Why, the answer is quite simple: GOD.

Most ancient cultures attributed a god to every force of nature, with such beliefs being prevalent across geographical divisions, until the rise of the Abrahamic religions and their tenet of monotheism.

Of course, one would expect that, almost five centuries since the Age of Enlightenment, the world would have been long rid of these ancient, and often ludicrous, beliefs. Unfortunately, that does not seem to be the case.

Now, that in itself might not seem like an issue, until we come to the realisation that the mind, once filled with tripe, no longer has space left for truth.

What is tripe? What is truth? That remains the question.

Your assumptions are your windows on the world. Scrub them off every once in a while, or the light won’t come in.

—Isaac Assimov

July 3, 2017

Word of the Week #66:

It is the break of dawn, and I am wide awake.

No, I did not rise what the sun, as our learned ancestors happened to recommend.

I have always found it easier to just stay awake, especially when my mind is in an excited state.

It probably seems quite odd to most uninitiated onlookers; in fact, it might just be quite odd.

People are often alarmed by these, well, admittedly alarming mannerisms of mine. Several have been quite vocal about their concerns, while some have made active attempts to intervene, obviously to no avail.

However, the view is clearer from my standpoint. If we do not spend today consumed by our passion, not what do we even seek from tomorrow? While some may wonder why I cannot rest my head each night, I, in turn, wonder how they can even pull themselves out of their beds the morn after.

That being said, I will admit, these antics come with a price to pay.

Encumbered forever by desire and ambition,

There’s a hunger still unsatisfied.

Our weary eyes still stray to the horizon,

Though down this road we’ve been so many times.

—High Hopes, by Pink Floyd

June 28, 2017

Book of the Week #35: [Guest Post]

Yashas:

So, as they say, all good things must come to an end…

What kind of a rule is that, anyway? I hate it. Stupid rule…

As one can possibly discern from my sour demeanour, I am here to announce that the conclusion of our collaboration with this wonderful young lady is now upon us.

Of course, we wouldn’t just let her leave, at least not without a final, particularly amazing post. And with that in mind, we chose to save the best for the last.

So, here we have the post that Shruti herself prefaced by saying, “Spent a reallllllllllly long time on this post and still feel like I can’t talk enough about it.”

Man’s Search for Meaning,

by Dr. Viktor E. Frankl

“If you read but one book this year, Dr Frankl’s book should be that one.”

—Los Angeles Times, on Man’s Search for Meaning

This is my sixth post on this blog. Considering how much Yashas has been requesting me to guest author more BoTW posts, it might seem like I have read scores of books.

Shall I let you in on a secret? I haven’t. Ssshhh…

Well, at least not as many as I would have loved to, by this time. And definitely not even close to what bibliomaniacs read by the time they are 23!

Nevertheless, here I am, on a reading spree this year, devouring everything from philosophy to science. I discovered my love for reading during high school and being the clichéd worried-about-academics-and-working-hard student that I was, I picked up a non-academic book only when I was not stressed about my studies, AKA holidays. So it was only natural that when I got the chance to study a minor course from any of the departments—other than physics, of course—for three semesters during my undergrad, I chose to study English Studies. The condescending crowd from IIT that loves to look down upon Humanities of course thought I was either a lunatic or someone to be pitied. But hello! I am having the last laugh.

The course opened up to me a plethora of literature I didn’t even know existed. Quite a few books I have read this year and more that I plan to read are known to me, thanks to this course. In this post, I talk about one such book, Man’s Search for Meaning. I read an excerpt from MSFM in my English Studies course and had been wanting to read the book ever since. Two years hence, as I was frantically searching for a copy of Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance in a Waterstones store in Brighton, serendipity struck me. Without a moment’s thought, I picked the copy of MSFM and straightaway headed to the cashier.

“There is much wisdom in the words of Nietzsche: ‘He who has a why to live for can bear almost any how.’”

The above quote is exactly what sums up Victor Frankl’s Man’s Search for Meaning. An Austrian neurologist and psychiatrist, Dr Frankl was a Nazi concentration camp inmate for three years during the Second World War. An enduring work of survival literature, as observed by New York Times, the book is an account of Dr Frankl’s Holocaust experiences.

The book was first published in German in 1946, a year after the author’s release from the concentration camp. Originally titled ‘From Death-Camp to Existentialism’ in English, the book has two parts. While part one is an autobiographical account of the author’s experiences, part two, added only in 1962 is an introduction to Logotherapy, the ‘Third Viennese School of Psychotherapy’, founded by Dr Frankl.

“In some way, suffering ceases to be suffering at the moment it finds a meaning, such as the meaning of a sacrifice.”

The basic tenet of the book, and Logotherapy in general, is that there is meaning to life, at every point, even at moments of suffering. How often do you find yourself or others blame their circumstances for their sufferings?

Dr Frankl asserts that man is not just a prisoner of his circumstances; if he finds a meaning to his existence, his mental freedom gives him the strength to endure even the cruelest conditions that life throws at him.

“The more one forgets himself — by giving himself to a cause to serve or another person to love — the more human he is and the more he actualizes himself.”

The first part of the book chronicles the author’s experiences, from the time he was taken to the concentration camp through the three years till he was freed, and a brief account after that as well. This compelling account is a powerful reminder of the intriguing human behaviour: the variety of human emotions and the response of man to myriad situations.

Based on his analysis of the other prisoners’ as well as his own behavior in the concentration camp, Dr Frankl describes three phases of a prisoner’s state of mind: shock, apathy and depersonalization. What struck me the most was the third phase, depersonalization, in which the prisoner gets so accustomed to the atrocities of camp that he does not even feel happiness after he is liberated.

“We can discover this meaning in life in three different ways: (1) by creating a work or doing a deed; (2) by experiencing something or encountering someone; and (3) by the attitude we take toward unavoidable suffering.”

Even though this masterpiece is an account of Holocaust, something nobody from my generation has, fortunately, witnessed, it remains one of the most inspiring and powerful pieces of literature whose tenets are applicable even today. Translations to 24 languages, over 9 million sold copies, listed among the ten most influential books in the United States; these figures speak volumes about the influence that this book has had over the last 71 years since its publication.

Dr. Frankl, author-psychiatrist, sometimes asks his patients who suffer from a multitude of torments great and small, “Why do you not commit suicide?” From their answers he can often find the guide-line for his psychotherapy: in one life there is love for one’s children to tie to; in another life, a talent to be used; in a third, perhaps only lingering memories worth preserving. To weave these slender threads of a broken life into a firm pattern of meaning and responsibility is the object and challenge of logotherapy, which is Dr. Frankl’s own version of modern existential analysis.

—Gordon W. Allport, from the Preface of Man’s Search for Meaning

The book is a short read, little over 150 pages long, and I highly recommend reading this in one go. If you give me a marker and ask me to highlight every important quote I come across in this book, I will probably end up colouring 90% of it!

I cannot stress enough how important this book is to me and millions across the globe. So I will end this already long post with the very last and my favourite quote from the book.

“The crowning experience of all, for the homecoming man, is the wonderful feeling that, after all he has suffered, there is nothing he need fear any more—except his God.”

Yashas:

You know, it is interesting how so many post-World War masterpieces are still extremely relevant to this day.

Yes, one can argue that a true masterpiece is inherently and necessarily eternal.

On the other hand, it is also notable how their survival through what was definitely one of the darkest episodes of recent human history forged the said masterpieces, thereby illuminating the path for every generation since.

Today, as we stand on the cusp of another humanitarian crisis that has been brewing for the better part of this decade, it is evident that the world should not dare to forget…

You can start reading Man’s Search for Meaning right here:

Do let us know what you think. Also, do recommend it to every man, woman and child you may encounter.

That is all for tonight.

I’ll be back when the wind and fates and chance bring me back.

—Pablo Neruda

Thank you.

June 27, 2017

Word of the Week #65:

Last night, as I lay in my bed, my mind spent a few moments organising the schedule for the day. That is just how my mind works.

This morning, however, as I woke up to the pitter-patter of the drops of water falling onto the balcony floor, my mind had somehow been wiped clean.

It is odd how, for no obvious reason, the rain has the power to pull us away from everything that ties us to our world, and spirit us away…

It also has a way of making the entire day about itself.

So, how does one make the most of a rainy day? Well, I, for one, have the simplest of plans.

I just look out the window, and smile.

The rain to the wind said,

‘You push and I’ll pelt.’

They so smote the garden bed

That the flowers actually knelt,

And lay lodged – though not dead.

I know how the flowers felt.

— Robert Frost, Lodged

June 21, 2017

Book of the Week #34: [Guest Post]

Yashas:

Led by this dauntless young lady, we continue this month of literary heavyweights with what is probably the very first Pulitzer Prize winner of our list.

Let us all strap in, shall we?

Interpreter of Maladies,

by Jhumpa Lahiri

Still, there are times I am bewildered by each mile I have traveled, each meal I have eaten, each person I have known, each room in which I have slept. As ordinary as it all appears, there are times when it is beyond my imagination.

Winner of the Pulitzer Prize for Fiction, Interpreter of Maladies is one of the most recognised works of its London-born American author of Indian descent, Jhumpa Lahiri.

A collection of nine short stories, the book is heralded as an impeccable narrative of the immigrant experience. After having read a short story from the same book—that goes by the same name—for an English course, I was not entirely sure how I felt about it. But I was eager to read more from the book. I recently did, and let’s say, I am not disappointed!

Lahiri writes in a language that is captivating and simple at the same time. She creates a vivid imagery that takes you into the very heartland of the places where her stories are based. Most of her stories among the nine revolve around the lives of Indian-Americans and it’s not difficult to guess why; Lahiri is a first generation Indian-American herself. Even in the stories that do not exclusively talk about Indian-Americans, you sense a kind of familiarity and intimacy that only a writer of Lahiri’s caliber can provide.

“When I first started writing I was not conscious that my subject was the Indian-American experience. What drew me to my craft was the desire to force the two worlds I occupied to mingle on the page as I was not brave enough, or mature enough, to allow in life.”

The experiences of the characters in her stories, many of which are said to be autobiographical, or rather, her own family’s, evoke strong emotions, and you find yourself rooting for the characters that are so distant, yet so familiar to yourself.

Lahiri does not paint a stereotypical or one-sided picture of the immigrant experience; rather she pictures something incredibly colourful, depicting many facets of the experience. The hopes, the dreams, the tribulations as people try to embrace a new land as their own.

The widespread popularity of this book just goes on to show that human emotions are universal, transcending beyond borders and cultures. In narrating these tales that speak of cross-cultural understanding and more, Jhumpa Lahiri becomes what she named her book aptly, an interpreter of maladies.

Yashas:

You can start reading the book here:

Do let us know what you think…

Well, that is all for tonight. We will be back, next week.

Thank you.

June 20, 2017

Word of the Week #64:

People who know me would probably know how the very prospect of getting a haircut fills my mouth with burning vitriol.

The reaction is almost incomparable, with the possibility of having to clean my room being a major, albeit rare, exception.

Nonetheless, as one grows older, one comes to realise that maintaining these long, glossy, bouncy, wavy hair, which have now come to be a significant part of your identity, is growing more and more untenable every passing day.

“Time erodes us all.”

― Meg Rosoff

With a heavy heart, I decided to pay a visit to the barbers’, and shear off my lustrous mane, lest I ruin whatever still remained of it.

However, as it would turn out, my wallet was completely empty, and a visit was all I could afford to pay.

And, as the gods above would have it, my mane survives another day.

June 14, 2017

Book of the Week #33: [Guest Post]

Siddhartha,

by Hermann Hesse

Translated by Hilda Rosner

“I have always believed, and I still believe, that whatever good or bad fortune may come our way we can always give it meaning and transform it into something of value.”

Siddhartha, written by the German writer and painter Hermann Hesse, was written in 1922. Originally written in German, it was first published in English in the United States in 1951.

The book remains, till date, one of the most influential novels, based in India, by a Western author. I came to know of the book a few years ago. Having a deep interest in spirituality and philosophy, it was only natural that I was drawn to this book.

If you know nothing about this book, it is easy to assume, just by looking at the book cover, that it is about the life of Siddhartha Gautam Buddha. But, surprise! It’s not. Although that does become clear in the first few paragraphs itself, I think this note is quite essential so that a few among you readers don’t get over-enthusiastic about this book just going by the title!

However, I do believe that this book is worth getting enthusiastic about…

SPOILER: The book does feature Buddha, albeit for a small, yet important, part.

“Wisdom cannot be imparted. Wisdom that a wise man attempts to impart always sounds like foolishness to someone else… Knowledge can be communicated, but not wisdom. One can find it, live it, do wonders through it, but one cannot communicate and teach it.”

The story is based in India in the same era as of the Buddha, about a young Brahmin named Siddhartha who, dissatisfied with his existence, sets out to seek enlightenment. How, you ask? Well, he can think. He can wait. He can fast. Over the course of his life journey, he comes across myriad kinds of people and has different kinds of experiences.

SPOILER: He meets the Buddha, moves on and meets a beautiful courtesan, learns the art of lust from her. In the meanwhile, he also works for a merchant. Yes, kind of stuff you’d not expect to see a man on a spiritual journey to indulge in. Later on, he drinks, gambles and meets and lives with a ferryman. The story does not end there. But well, read the book for more.

“I have had to experience so much stupidity, so many vices, so much error, so much nausea, disillusionment and sorrow, just in order to become a child again and begin anew. I had to experience despair, I had to sink to the greatest mental depths, to thoughts of suicide, in order to experience grace.”

Siddhartha’s quest for enlightenment goes on to demonstrate the importance of every kind of experience and every person one comes across in their lifetime. It was through each of those experiences that Siddhartha is able to achieve enlightenment at the end.

“What you search is not necessarily the same as what you find. When you let go of the searching, you start finding.”

It is heartening to know that a book set in the East, written in the 1920s, talking about spirituality and enlightenment, has amassed such a huge popularity across the world. It’s quite evident that even Western audience is able to identify with it. We all are humans, after all.

Hermann Hesse did not preach us to give up material possessions and go to the woods to meditate and seek truth, but if a narrative talking about something similar is able to connect to people across the world, even today, or especially today, it most probably does offer something of value.

Siddhartha is a short novella, spanning around 150 pages. It has a simple language—or say, the translated version that I read, by Hilda Rosner—although I should be honest and say that I found some of the repetitive phrases uttered by the main character and his friend towards the beginning, a little irritating.

Speaking of personal experience, I would not put this book in the ‘unputdownable’ category. It is possible to find it boring at times, but the message and philosophy of the book makes me glad that I stuck to it till the end.

Yashas:

So, she has basically taken over, at this point, and I could not be more glad to let go of the reins…

Now, you can start reading the book right here:

Of course, there are other translations available, and the readers are encouraged to seek them out and let us know what you think.

Well, that is all for tonight. We will be back, next week.

Thank you.