Michael Roberts's Blog, page 44

June 16, 2020

The deficit myth

Stephanie Kelton is professor of economics and public policy at Stony Brook University, a former Chief Economist on the U.S. Senate Budget Committee (Democratic staff) and was an economic policy adviser to Senator Bernie Sanders, the leftist American presidential hopeful. Kelton is a prominent exponent and populariser of what is called Modern Monetary Theory (MMT).

In a new book The Deficit Myth, Kelton explains what is the most important conclusion to draw from MMT – namely, it is a myth that if the government runs large budget deficits (ie spending more than it gets in tax revenues) and borrows the difference, eventually public sector debt will become unsustainable (ie debt repayments and interest will become too much for the government to deal with), leading to sharp increases in taxation or cuts in public spending and possibly a run on the national currency by foreign creditors.

Kelton says that this argument of the ‘Austerians’ is a myth. In her book, she brings forward the main arguments of MMT: first, that “governments in nations that maintain control of their own currencies — like Japan, Britain and the United States, and unlike Greece, Spain and Italy — can increase spending without needing to raise taxes or borrow currency from other countries or investors.” The state (national government) controls the unit of currency accepted and used by the public, so it can create any amount of that currency to spend. So the state need not issue bonds to borrow from the private sector, it can just digitally ‘print’ the money. Indeed, that is what is happening right now during the COVID-19 pandemic, the argument goes. The US administration and others are spending trillions on paying workers to stay at home and businesses to go into hibernation. Yes, it is financing some of this by issuing bonds, but it is the Federal Reserve or the Bank of England that is the main purchaser of these bonds, so in effect ‘printing’ money to spend.

The argument of MMT and Kelton is that this is a new way of looking at public finances and monetary policy. You see, what nobody has realised until the MMT guys were listened to is that, historically, “It’s the state’s ability to make and enforce its tax laws that sustains a demand for them, which in turn makes those dollars valuable.” This is the theory of chartalism, developed by a German economist of the 1920s, George Knapp and others, that money has emerged in modern economies as the result of the state needing to spend and so needing to invent a unit of currency that it can tax people in. So the demand for money by people has been created by the state in order to pay taxes. Money is created by the state and then taken back (destroyed) by taxation. So, you see, the state controls money and therefore can control the modern economy. It can spend without the constraint of rising debt. “Governments in nations that maintain control of their own currencies — like Japan, Britain and the United States, and unlike Greece, Spain and Italy — can increase spending without needing to raise taxes or borrow currency from other countries or investors.”

Kelton makes the point that all MMT supporters make: that “M.M.T. simply describes how our monetary system actually works. Its explanatory power doesn’t depend on ideology or political party.” When I read or hear that from MMT supporters, I am concerned. Of course, truth and reality can be distinguished from ideology, but ideology uses the truth that it wants to reveal – there is never a neutral objectivity. Is MMT really the basis for left-wing or socialist economic policy that so many of its adherents claim? – well, not according Kelton. Apparently, MMT is just as useful to right-wing Republicans as it is to Marxists. Indeed, the idea that governments can run deficits as they please appeals to both left and right in the capitalist spectrum. As Dick Cheney, the extreme right-wing Vice President under George W Bush, put it when military spending rocketed to fund the invasion of Iraq: “deficits don’t matter.”

But is MMT right that money emerges in modern economies because the state’s need to spend? This claim of chartalism is certainly open to question. Historians of money and the great economists of classical political economy would deny it. In particular, Marx would not agree. For Marx, money emerges in society as a universal medium of exchange in trade within and between local communities. (Grundrisse: “The circulation of commodities is the original precondition of the circulation of money” p165 – not the state). In capitalism, money takes on the role of capital as money buys labour power and means of production for exploitation and the production of value and surplus value “money itself can exist as a developed moment of production only where and when wage labour exists” p 223). Money represents value created in an economy (“It is the comprehensive representation of commodities”, p210).

For Marx, money does not emerge from outside the process of exchange in markets or in accumulation of capital. It is not exogenous, coming from the state, as MMT claims; instead it is deeply endogenous to the capitalist mode of production, the objective of which is to make money. As Marx says in Grundrisse: “Money does not arise by convention, any more than the state does. It arises out of exchange and arises naturally out of exchange: it is a product of the same.” p165. For Marx, neither the state nor money is exogenous or neutral to the capitalist mode of production. Thus Marxist Monetary Theory, as opposed to Modern Monetary Theory, is ideological. It is on the side of labour, based on the law of value and the exploitation of labour power. MMT has no concept of value or the law of value in capitalist economies, namely that production is for profit not social need; production is for exchange value, not use value; based on the exploitation in production, not on the creation of money for taxation. Profit does not touch the sides of MMT.

But maybe Modern Monetary Theory is right and Marxist Monetary Theory is wrong. In her book, Kelton tells readers of her conversion to the first MMT. It happened when she met the ‘father of MMT’, former hedge fund manager Warren Mosler. Kelton visited him at his beach house in the tax haven US Virgin Islands. Mosler explained that he got his children to do their chores by insisting that they must be taxed and if they could not pay, then all their privileges would be withdrawn. His tax took the form of his business cards (this was the unit of currency created by Mosler, representing ‘the state’). In order to get these business cards, the children had to carry out tasks. Thus the ‘Mosler state’ created money (business cards) which the people needed in order to pay taxes. Kelton was overwhelmed by this proof of “how the monetary system works” and became a convert – and, as the old saying goes, converts can be even more fervent than the original prophets. Kelton is now the loudest supporter of MMT, at least in America.

What Kelton failed to recognise in the Mosler example is that there were chores to be done. Things had to be produced and human labour had to be exerted. So the children must work or the household goes downhill. But the Mosler household was not producing for exchange, but for consumption within the household. The Mosler household was not trading with other households and exchanging goods or services. If they were, then the Mosler business cards would have to represent some exchange-value, not just some labour time involved within the Mosler house. The cards would have to be acceptable as a representation of labour time in other households. His ‘state’ (Mosler) could not decide that. In Grundrisse, Marx explains why having labour chits is not money and cannot operate as money in a capitalist economy, where production (work) is for exchange not for consumption.

Take a topical example. Currently many airlines cancelling flights in the COVID lockdown are trying to avoid refunding customers with money (dollars) and instead are offering vouchers. Anybody can see that these vouchers are not money, not a universal representation of the exchange value of all flights and other commodities, but merely tickets with that particular airline and so worth only the dollar price of trips with that airline alone. Inside that one airline house, these vouchers are ‘money’, but nowhere else.

The idea that it is the state’s power to tax that is an explanation of the emergence of money and exploitation seems far-fetched, anyway. Kelton claims that “the British Empire and others before it were able to effectively rule: conquer, erase the legitimacy of a given people’s original currency, impose British currency on the colonized, then watch how the entire local economy begins to revolve around British currency, interests and power.” Do we really think that British imperialism worked because it controlled the currency of other nations? Would it not be more accurate to say that because British imperialism imposed through force and conquest its control over many nations, it was able to exploit its people and then control their currency? Does the US rule the world because it has the international reserve currency, the dollar; or did the dollar become the international reserve currency because US imperialism dominated the world in trade, technology, finance and military power?

Kelton cites Mosler’s comment that “Since the U.S. government is the sole issuer of the currency, he said, it was silly to think of Uncle Sam as needing to get dollars from the rest of us.” Well, yes, that’s ok for Uncle Sam, but for many countries exploited by imperialism, they do not control their own currencies and are heavily dependent on the decisions of foreign multi-nationals and financial institutions. Can those governments print money without constraint to spend and tax? Ask Argentina and other emerging economies in the current COVD-crisis. Their ‘fiscal space’ is very much constrained by international capital. MMT is no use to them.

But the real issue for me with Kelton’s book and with MMT is whether knowing that governments can spend money and run deficits without the constraint of the burden of rising debt is really saying anything new or radical. Keynesian economic theory has always argued that government deficits and rising public sector debt need not become ‘unsustainable’, as long as the extra spending produced faster economic growth. If real GDP growth is higher than the interest cost on the debt (g>r), then (public) debt can be sustainable. All MMT seems to be adding is that governments don’t even need to increase debt in the form of government bonds; the central bank/state can ‘print’ money to fund spending.

But there are constraints on unlimited government spending that MMT admits to. Kelton points out: “the only economic constraints currency-issuing states face are inflation and the availability of labor and other material resources in the real economy.” Two big constraints, it seems to me. How would inflation arise? According to MMT, it is when unused capacity in an economy is used up, so that there is full employment of the workforce and given technology. After that, if there is no extra capacity, more government spending financed by printing money will be inflationary. If governments keep printing money to spend, inflation of prices will take place because supply has reached its maximum.

But Kelton says that this constraint allows us to concentrate on the real issue: ““M.M.T. asks us to focus on the limits that matter. At any point in time, every economy faces a sort of speed limit, regulated by the availability of its real productive resources — the state of technology and the quantity and quality of its land, workers, factories, machines and other materials. If any government tries to spend too much into an economy that’s already running at full speed.”

Exactly! And here the real issue is exposed. How does a capitalist economy expand capacity, investment and production? There are limits on its ability to do that. But MMT actually does not focus on these ‘limits that matter’, only on the one that does not matter (so much) – deficits and debt. More important to understand is why is there unused capacity; and why growth drops and there are slumps. Indeed, why are there regular and recurring slumps in capitalist economies? These questions are not dealt with or answered by MMT. According to Kelton, “M.M.T. simply describes how our monetary system actually works”. Even if that were right, which I have doubted above, that does not take us very far.

In contrast, Marxist monetary theory does deal with the ‘constraint’ that matters, because it based on the law of value; namely that value is created by the exertion of human labour. Under capitalism, human labour power is bought by capital (which owns the means of production) to exploit and produce value and surplus value (profit). Under capitalism, value is not created by the state issuing money; instead, money represents value created by the exploitation of labour power. Printing more money so that governments can spend more money will not produce more value unless labour power is exploited more by capital as a result.

Kelton says that “In 2020, Congress has been showing us — in practice if not in its rhetoric — exactly how M.M.T. works: It committed trillions of dollars this spring that in the conventional economic sense it did not “have.” If that is right, it is not good news for MMT. For will all these trillions deliver more output and more resources to meet social need? Much of this largesse from the ‘digital printing’ of money into bank reserves will not end up as more output, employment and investment. Most of the trillions are either being hoarded by the big companies, while raising more debt at zero rates; or being invested in the stock and bond markets for capital gains. It will not go into in increasing capacity in productive sectors, because the profitability of capital is very low – as I have shown in other posts. MMT has nothing to say about this, instead resting on its faith in increasing the quantity of a state currency unit. Marxist theory does: hoarding money tells you that money has become a fetish, the objective in itself, rather than to be used as capital to extract more surplus value from the exploitation of labour in production.

It may be an ‘Austerian’ myth that governments cannot run deficits and need to ‘balance the books’. But it is an illusion to reckon that the crisis-prone nature of capitalist production can be ‘managed’ by means of ‘money artistry’, that is, by the manipulation of money, credit and government deficits. That’s because the structural causes of the crises and under-capacity lie not in the financial or monetary sector or the fiscal sector, but in the system of globalized capitalist production.

MMT and Kelton do not touch on the important issues of the failure of capitalism to deliver social needs and the underlying exploitation of the many by the few. On those questions, MMT has nothing to say and different MMTers have different views. I’m sure most, if not all MMTers (like traditional Keynesians), want governments to intervene to meet social needs. Some (like Bill Mitchell) support socialist measures to replace the law of value and the capitalist mode of production; some (like Kelton) don’t. Ah, says Kelton and MMTers, that is not the point of MMT. We just want to show that it is a myth that the state cannot run up deficits without consequences. Again, that does not seem very new, radical and not even correct in all circumstances.

June 12, 2020

Resetting the economy – for social need not profit

In a recent World Economic Forum (WEF) virtual meeting, the ageing heir to the British monarchy, Prince Charles spoke with IMF chief Kristalina Georgieva. Charles’s speech was part of a launch event for The Great Reset, a project involving the WEF and the Prince of Wales’s Sustainable Markets Initiative, aimed at rebuilding the economic and social system to be more ‘sustainable’. Charles called for a resetting of the world economy after the COVID pandemic subsides.

I think this is the first time that I have agreed with a member of any ‘royal family’ on anything. But Charles is right, we need to reset the world economy after the pandemic has shown all its failings in stark reality.

Of course, Charles did not have in mind replacing the capitalist mode of production but simply making capitalism work better, more fairly and put on what he called a path of ‘sustainable development’. He outlined a ‘five point plan’ written for him by his advisers. First, he said, we must recognise “the interdependence of all living things”. In other words, there was a breakdown in the link between humanity and nature. Here Charles agreed with Marx and Engels’ analysis of over 150 years ago that, with the development of the capitalist mode of production, a ‘metabolic rift’ had been cleaved open between humans and nature.

The drive for profit under capitalism had spread uncontrolled industrialisation and urbanisation globally. The productivity of labour had rocketed along with the world population, but with no regard to the environment, nature and in particular wildlife species, whether flora or fauna. Localised farming had been replaced by globalised industrial farming’; forests were being decimated through logging and the exploration for minerals and fossil fuels for the world economy. This had brought humans into formerly remote areas and close to pathogens which have been in wildlife for thousands of years. These pathogens have now jumped across into industrial farmed animals and into food markets, infecting humans who have no immunity. COVID-19 is just one of these new pathogens as ‘nature strikes back’.

Charles wants the strategic leaders of the global capitalist economy to recognise this ‘rift’ and find ways to bring humanity back into harmony with nature on a ‘sustainable path’. But he ignored the question of whether that was possible under a mode of production for profit and accumulation of capital without restraint. Indeed, Charles “emphasised that the private sector would be the engine of recovery and was heartened by the pledges from business leaders to recognise the damage to the environment that would result from an unfettered dash for growth.”

In his five points, Charles noted that the uncontrolled industrialisation of the world using fossil fuels for energy had led to a rise in global warming that was changing the climate of the planet at a disastrously rapid pace. He said that the world economy had to be reset to advance ‘net zero emissions’ as soon as possible. But how was this to be done? According to Charles: by the market. “Carbon pricing can provide a critical pathway to a sustainable market.” The fact that carbon pricing: the market solution for controlling emissions had clearly failed – as many studies show – was ignored. If this were the only solution to global warming and climate change, then the planet is doomed.

However, Charles did offer another solution. One of his five points was that “Investment must be rebalanced. Accelerating green investments can offer job opportunities in green energy, the circular and bio-economy, eco-tourism and green public infrastructure.” But again, he did not explain where this investment was going to come from – the capitalist sector, the fossil fuel industry? There was no mention of taking over the fossil fuel industry and phasing it out. Instead, we had to rely on ‘green investment’ becoming more profitable and creating jobs.

And in the last of his points, he placed his hopes on the science, technology and innovation. He claimed that the reset of the world capitalist economy on a sustainable path’ could be achieved because “humanity is on the verge of catalytic breakthroughs that will alter our view of what it possible and profitable in the framework of a sustainable future.” “Possible and profitable.” So that’s all right then.

The recent movie, Planet of the Humans by Jeff Gibbs and Michael Moore, has been roundly condemned for its inaccuracies and its implied Malthusian approach that the problem is’ too many people’. But what the movie does do well is show that ‘green capitalism’ ie relying on the fossil fuel industry and other capitalist companies to develop technologies that will save the planet, is a sham, a colossal pipe dream. The fossil fuel industry is the main generator of greenhouse gas emissions and indeed the global military is the main user. Charles offered no solutions here.

Capitalism is going to do little or nothing to save the planet from climate disaster or bring humanity back into harmony with nature. That requires global planning and public control of energy and food production. Mariana Mazzucato, the celebrated ‘scariest economist in the world’, has pointed out that “Given the global nature of the economy, without a truly global recovery plan, a rest of the world economy on a sustainable basis will not be possible. We need policies that are not only reactive but also strategic, bringing us closer to an investment-led global Green New Deal. Bold plans to create carbon neutral cities and regions could foster creativity and innovation”.

Mazzucato argues that we should “remember 2020 as the year we rediscovered the need for strong global health systems and the world avoided a new Depression with a Green New Deal and an investment-led recovery.” Unfortunately Mazzucato, having promoted the need for the state to take a lead and not just leave it to the market, offers a solution based on ‘partnerships’ with the capitalist sector. But any Green New Deal based on partnership with the fossil fuel industry will fail.

Establishing a strong health system that prevents humanity dying from future pandemics and protects those infected, by going into ‘partnership’ with profit-making big pharma companies and outsourcing services and medical supplies to private contractors, has already proven a failure in this pandemic.

Take the example of big pharma. Several years ago, the EU Commission decided to set up a partnership body, IMI, made up of commission officials and representatives of the European Federation of Pharmaceutical Industries (EFPIA), whose members include some of the biggest names in the sector, among them GlaxoSmithKline, Novartis, Pfizer, Lilly and Johnson & Johnson. The IMI had a budget of €5bn (£4.5bn), half public money and half from the pharma companies. But the pharma companies controlled those research projects. They rejected an EU plan to fast-track vaccines in preventing the pandemic. They decided against funding projects with the Coalition for Epidemic Preparedness Innovations, a foundation seeking to tackle so-called blueprint priority diseases such as Mers and Sars, both of them coronaviruses.

Instead, the IMI did projects that made profits for the companies, not for social need. rather than “compensating for market failures” by speeding up the development of innovative medicines, as per its remit, the IMI has been “more about business-as-usual market priorities”. So much for public-private partnership.

The world’s 20 largest pharmaceutical companies undertook around 400 new research projects in the past year, according to Bloomberg Intelligence. Around half were focused on treating cancer, compared with 65 on infectious diseases. It’s just not profitable to find drugs to deal with diseases that affect the wider population particularly on poor countries. But don’t worry, the EU now plans to spend more billions in advanced purchased deals with pharmaceutical companies for promising drugs and vaccines to fight COVID-19. So the companies will now be paid yet more big bucks by the taxpayer to make profits.

Surely, what the pandemic has shown is the market and investment for profit cannot deliver an effective global health system. What is needed in any resetting is public ownership of the major pharma companies and increased public investment in fully publicly-owned health services.

Reacting to Prince Charles, IMF chief Georgieva wrote down some ideas for “promoting a more inclusive recovery”. But as usual it was the same old message of “increasing people’s access to opportunities”. So people should have more opportunities to make money but not have any control over the planning of resources for social need and the protection of the planet. That task remains as before in the hands of big capital.

Yes, says Georgieva, we need to “scale up public investment in health care to protect the most vulnerable and minimize the risks from future epidemics. It also means strengthening social safety nets; expanding access to quality education, clean water, and sanitation; and investing in climate-smart infrastructure. Some countries could also expand access to high-quality childcare, which can boost female labor force participation and long-term growth.” But how is that to be done? Well, by “improving the efficiency of spending and to mobilize higher public revenue…through “tax reform: for example, by raising the top rate of income tax” and “there should be a concerted effort to combat illicit flows and close tax loopholes, both domestically and internationally.” But no takeover of the big tax-avoiding multi-nationals, of course.

Georgieva says we need “more investment in education—not just spending more on schools and distance-learning capacity, but also improving the quality of education and the access to life-long learning and re-skilling.” But how is that to be achieved without massive increases in public spending and the ending of subsidies to private education for the rich?

Georgieva says we need to “harness of the power of financial technology” for everybody. She means banking mostly. But technology can also be applied to ensuring everybody has access to the internet free at the point of use. How is that to be achieved, without public ownership of the major telecoms and social media companies, as well as the banks themselves?

The leader of the IMF talked about world coordination of this resetting of the economy. But such coordination has been sadly lacking in dealing with the pandemic. That’s because it depends on national governments tied to the interests of their own capitalist sectors and because coordination has depended on the market, not on social need.

Big capital is getting ready to try and ‘return to normal’ by boosting the profitability of capital by sackings, lowering wages and introducing robots and automation to replace living labour. But any resetting of the world economy cannot be achieved by ‘returning to normal’ ie with private profit as the driver of investment, production, employment, health and protection of the planet.

What would a resetting of the economy based on social need involve? Here are a few suggestions.

We need a global plan for full employment, with jobs for all at a living wage. Pensions and benefits for those who cannot work must be raised to at least two-thirds of the average wage.

We need substantial public investment in infrastructure and public services like health, education, housing and communications. Such a re-direction of investment could soon establish much of these services as free at the point of use globally.

And it must be investment that is in harmony with nature and the planet. The fossil fuel industry must be phased out, just as the tobacco and military should be. The technology is there to do it, what is lacking is the economic and political power in the hands of democratic institutions rather than in big capital and its representatives, who prattle on about ‘inclusion’ and ‘sustainable growth’.

Yes, we must cancel the debts of the poorest countries exploited by the multl-nationals of the imperialist countries. Yes, we must end the tax havens for the rich and powerful. Yes, we must re-introduce proper progressive taxation (one of the first demands of the Communist Manifesto back in 1848) to reduce inequality.

But none of this will be possible without public ownership of the major financial institutions and multi-nationals so that the world can be planned through democratic organisations for social objectives, not for profit of the few owners of capital.

That’s what resetting the economy should mean.

June 6, 2020

Returning to normal?

The recent release of the US jobs data for May, which apparently showed a reduction in the unemployment rate from April, sparked a sharp rally in the US stock market. And if you were to follow the stock markets of the major economies, you would think that the world economy was racing back to normal as the lockdowns imposed by most governments to combat the spread of COVID-19 pandemic are relaxed and even ended.

The stock markets of the world, after dropping precipitately when the lockdowns began, have rocketed back towards previous record levels over the last two months. This rally has been driven, first, by the humungous injections of money and credit into the financial system by the major central banks. This has enabled banks and companies to borrow at zero or negative rates with credit guaranteed by the state, so no danger of loss from default. At the same time, governments in the US, UK and Europe have made direct bailout funds to major companies stricken by the lockdowns, like airlines, auto and aircraft makers, leisure companies etc.

It’s a feature of the 21st century that central banks have become the principal support mechanism for the financial system, propping up the leverage that had grown during the ‘great moderation’ a phenomenon that I detailed in my book, The Long Depression. This has combated the low profitability in the productive value-creating sectors of the world capitalist economy. Companies have increasingly switched funds into financial assets where investors can borrow at very low rates of interest to buy and sell stocks and bonds and make capital gains. The largest companies have been buying back their own shares to boost prices. In effect, what Marx called ‘fictitious capital’ has risen in ‘value’ while real value has stagnated or fallen.

Between 1992 and 2007, central bank monetary injections (“power money”) doubled as a share of global GDP from 3.7% of total ‘liquidity’ (money and credit) to 7.2% in 2007. At the same time, bank loans and debt nearly tripled as a share of GDP. From 2007 to 2019, power money doubled again as a share of the ‘liquidity pyramid’. Central banks have been driving the stocks and bond market boom.

Then came Covid-19 and the global shutdown that has pushed economies into a deep freeze. In response, the G4 central bank balance sheets have grown again, by around $3trn (3.5% of world GDP), and this rate of growth is likely to persist through to year-end as the various liquidity and lending packages continue to be expanded and drawn down. So power money will double again by the end of this year. That would push global power money up to $19.7trn, almost a quarter of world nominal GDP, and three times larger as a share of liquidity compared to 2007.

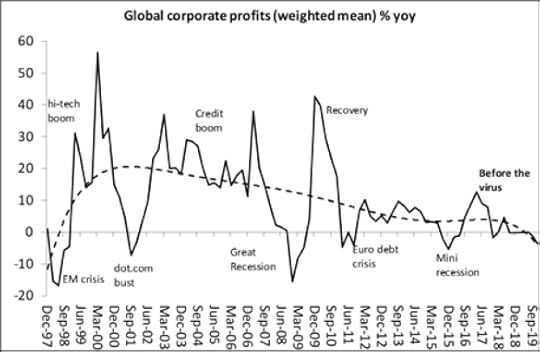

No wonder stock markets are booming. But this fantasy world of finance increasingly bears no relation to the production of value in capitalist accumulation. While the US stock market races back to its previous levels, corporate profits in the pandemic lockdown are suffering sharpest fall since the Great Recession of 2008-9. The gap between fantasy and reality is even greater than it was in the late 1990s just before the dot.com bust that saw stock valuations collapse by 50%, to turn the fictitious into the real.

But the other reason why the financial markets are booming is the optimistic belief promoted by governments that the COVID-19 disaster will soon be over. The argument goes that this year will be terrible for GDP, employment, incomes and investment in the ‘real’ economy, but everything is set to bounce back in 2021 as the lockdowns end, the miracle vaccine comes along and thus there is a quick ‘return to normal’. The speculators are looking to jump over the chasm of the pandemic slump to the other side where things can motor on again.

In the US, the May employment figures showed a sharp recovery in jobs created. As the lockdowns started to end or relax in the US, it seems that many Americans are returning to work in the leisure and retail sectors after being furloughed for two months. The stock market loved this, assuming that the V-shape is happening. But the US unemployment rate was still 13.3%, or more than one-third higher than in the depths of the Great Recession. And if you include those wanting full-time work but cannot get it, the U-6 category, then the unemployment rate was 21%, and adding another 3m people who were not classified, the total unemployment rate in May is more like 25%. Moreover the rate for blacks rose.

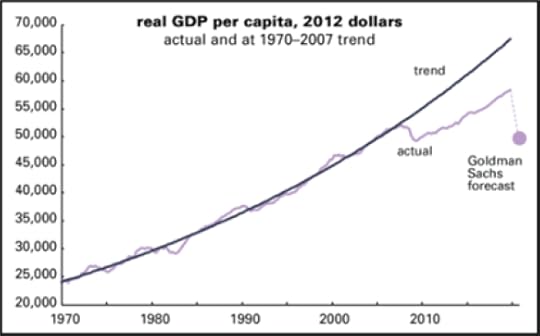

The return to work of some retail and leisure employees is only to be expected. The question is whether getting GDP and investment growth back to previous (relatively weak levels) and employment with it is possible in any short span of time. Most forecasters don’t’ think so. Indeed, while the stock markets head back to previous highs buoyed on the hope of a V-shaped recovery, most mainstream economic forecasts are predicting doom and a lengthy drawn out return, with some expecting no return to previous trends at all.

As I have argued in previous posts, the world capitalist economy was not motoring along at a pace before pandemic hit. Indeed, in most major economies and in the so-called larger emerging economies, growth and investment had already slowed to a trickle, while corporate profits had stopped growing at all. The profitability of capital in the major economies was near a post-war low, despite the apparent mega-profits being made by the so-called FAANGS, the techy media giants.

The US Congressional Budget Office (CBO) has drastically revised down its real GDP forecast for the US. It now expects US nominal GDP to fall 14.2% in the first half of 2020, from the trend it forecast in January before the COVID-19 pandemic broke. Then it expects the various fiscal and monetary injections by the authorities and the end of the lockdowns to reduce this loss from the January figure to 9.4% by end 2020. The CBO still expects a sort of V-shaped recovery in US GDP in 2021 but does not expect the pre-pandemic crisis trend in US economic growth (already reduced in the Long Depression since 2009) to be reached until 2029 and may not even return to the previous trend growth forecast until after 2030! So there will be a permanent loss of 5.3% in nominal GDP compared to pre-COVID forecasts – $16trn in value lost forever. In real GDP terms, the loss will be about 3% cumulatively, or $8trn in 2019 money. And this assumes no second wave in the pandemic and no financial collapse as companies go bust.

It’s a similar forecast for Europe. After euro area real GDP registered a record decline of 3.8% in the first quarter of 2020, the ECB predicts a further decline in GDP of 13% in the second quarter. Assuming the pandemic lockdowns come to an end and fiscal and monetary measures are effective in helping the EZ economy, the ECB reckons that real GDP in the euro area will still fall by 8.7% in 2020 and then rebound by 5.2% in 2021 and by 3.3% in 2022. But real GDP would still be around 4% below the level originally expected before the pandemic. Unemployment will be still be some 20% above the forecast before the pandemic. And that’s the ‘mild scenario’. Under a more severe scenario where there is second virus wave and further restrictions, the ECB forecasts that the Euro area will still be some 9% below previous expected levels in 2022 and not return to ‘normal’ for the foreseeable future!

Outside the Eurozone, the already weak UK economy is unlikely to manage a V-shape rally. Historically, low growth has persisted in the UK after recessions – there is permanent scarring. There is even less reason to assume that this time is different.

And when we look at the indicators for global economic activity, levels remain severely depressed in May, indeed at levels below the bottom of the slump of 2008-9.

As for the ‘emerging economies’, the picture is even grimmer. If you believe the mainstream forecast for a -10% fall in 2020, Argentina’s GDP this year will drop back to its 2007 level. For Brazil, the forecast of -7% in 2020 takes the economy back to 2010 – ten years of gains in GDP gone. Mexico’s fall of -9% returns it to 2013. A “lost decade” even before you factor in currency devaluation effects. Over a ten-year horizon, Brazil and Argentina will end up with lower real GDP levels after 20 years of the 21st century than 30 years ago.

Most important as a guide to whether the major capitalist economies can ‘return to normal’ as the US stock market investors jubilantly reckon is the level of profitability of capital. The first quarter figures for US corporate profits showed the direction for the future. US corporate profits fell at a 13.9% annual pace and were 8.5% below the first quarter of last year. The key productive sectors (non-financial) saw profits fall by a staggering $170bn in the quarter, so that there was no increase in profits compared to Q1 2019 – and that does not take into account inflation. Indeed, US non-financial sector profits have been in decline more or less for the last five years, so 2020 will only add to the problems of the US corporate sector in trying to come out of this pandemic lockdown with the same previous levels of investment, production and employment.

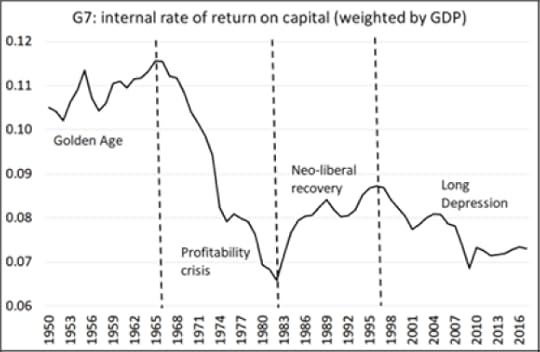

Indeed, if you look at the profitability (not the mass of profits) of the G7 economies, then more likely than a return to normal (weak as that was) is another leg down in this Long Depression that the major imperialist economies have experienced (with short up and down bursts) since 2009. Look at this graph of G7 profitability of capital.

This comes from the data provided by the Penn World Tables 9.1. It is the internal rate of return on net capital series (new to the Tables). I have weighted the profitability by GDP for the top seven advanced capitalist economies (G7). What is interesting for this post is that we can see that the profitability of capital actually peaked (as a weighted average) in 1997 and the whole two decades of the 21st century is one of a trend fall in profitability (interspersed with short upturns (2001-2005, 2009-10). I have extended the Penn IRR estimate (which ends in 2017) to 2021 using the EU AMECO database estimates (which are similarly calculated to the Penn IRR). In doing that, the G7 profitability of capital will likely plunge to all-time low in 2020 and make only a moderate bounce back in 2021.

Financial markets may be expecting a quick return (and investors riding this forecast are making huge profits right now). But the reality is that the financial market boom is floating on an ocean of free credit provided by the state and central bank monetary financing. This credit is not making its way into rising economic activity, as the measure of the velocity of money (the speed of money transactions) shows. The credit-fuelled boom in fictitious capital has not driven faster growth in real value or profitability. It’s pushing on a string.

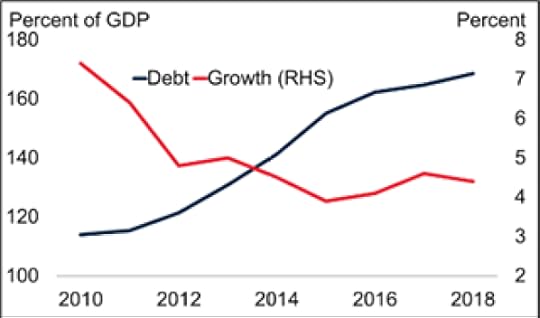

Debt has built up far faster than any rise in value. Indeed, the ‘productivity of debt’ (IDOR) has gone negative.

Keeping asset markets up is one thing; getting 35m Americans back to work is quite another, particularly when most are employed by businesses that don’t enjoy the benefits of being in the S&P 500 and are a long way from the leading tech firms that have propped up stock price indexes.

The reality is that the pandemic, in an economy where growth was already on a downward trajectory and productivity growth was low, has merely reinforced existing trends. The increase in debt that the surge in power money facilitates will act as a further drag on growth. Despite the optimism of the financial markets, a return to normal is disappearing over the horizon.

May 31, 2020

Capitulating to adults

During the pandemic lockdown, I have been able to read a range of new economics books, some Marxist but most not. It seems that many leading economists have published new stuff in the last two months. Over the next few weeks, I shall post some reviews of these.

I shall start with Sellouts in the Room by Eric Toussaint. Originally published in French and in Greek in March 2020 under the title Capitulation entre Adultes, the book will be available in English before the end of 2020. Eric Toussaint takes us back to events of Greek debt crisis when the Troika (the EU Commission, the ECB and the IMF) tried to impose a drastic austerity programme on the Greek people in return for ‘bailout’ funds to cover existing debts owed by Greek banks and the Greek government to foreign creditors, as credit for Greece in markets dried up and the government headed for default.

At the beginning of 2015, the Greek people elected the left-wing Syriza party to power. Syriza pledged to resist austerity measures. The new prime minister Tsipras appointed the already well-known leftist economist Yanis Varoufakis as finance minister to negotiate a deal with the Troika. As we subsequently know, Varoufakis was unable to persuade the Troika and EU leaders to drop the austerity demands. Tsipras called a referendum for the Greek people on whether to accept the Troika demands. Despite a massive media campaign by the capitalist press and dire threats from the Troika and the strangling of the Greek economy and banks by the ECB, the Greek people voted 60% to reject the Troika plan. But immediately after the vote, Tsipras caved into the Troika and agreed to their demands.

Varoufakis resigned as finance minister and later he wrote an account of his negotiations with the Troika, called Adults in the Room. Éric Toussaint was also in Greece at the time. He was coordinating the work of a debt audit committee set up by the president of the Hellenic Parliament in 2015 to look at the nature of the debt that the Greeks owed to the likes of European banks, hedge funds and other governments. He “lived nearly three months in Athens between February and July 2015, and in the context of my work as scientific coordinator of the audit of Greece’s debt, I was in direct contact with a number of members of the Tsipras government.” Toussaint has now written an alternative view of those events from that recounted by Varoufakis. And it amounts to a devastating critique of the Syriza government and of Varoufakis’ strategy and tactics during 2015.

Does it matter what happened? Toussaint reckons it does because there are important lessons to be learned from the Greek debt crisis. The common view now is that Syriza had no alternative but to submit to the Troika as otherwise the Greek banks would have collapsed, the economy would have fallen down an abyss and Greece would have been thrown out of the European Union to fend for itself. For example, Paul Mason, British leftist broadcaster and writer, wrote in 2017 that “I continue to believe Tsipras was right to climb down in the face of the EU’s ultimatum, and that Varoufakis was at fault for the way he designed the “game” strategy.”

Toussaint’s denies the narrative of TINA (‘there is no alternative’), arguing that there was an alternative strategy that Syriza could have followed and, in particular, Toussaint singles out Varoufakis for failing to recognise or adopt this in his role as finance minister. In Toussaint’s view, Varoufakis started from the premiss that he had to persuade the Troika to act as “adults” and aim to convince them to reach a reasonable compromise. From the very beginning Varoufakis made extremely minimal counter-proposals to the Troika austerity measures: “Varoufakis reassured his opposite numbers that the Greek government would not request a reduction of the debt stock, and he never called into question the legitimacy or legality of the debt whose repayment was demanded of Greece.” He never asserted the right and the determination of the Greek government to conduct an audit of Greece’s debts, says Toussaint.

And Varoufakis not only said that the government he represented would not call into question the privatizations that had been conducted since 2010, but even allowed for the possibility of further privatizations. Indeed, Varoufakis repeatedly told the European leaders that 70 per cent of the measures called for by the Troika’s Memorandum of Understanding were acceptable. While Varoufakis discussed with these ‘adults in a room’, the Syriza government continued to pay off several billion euros in debts between February and 30 June 2015, while the Troika did not make a single euro available. The public coffers continued to be emptied, principally for the benefit of the IMF.

Varoufakis and the inner circle around Tsipras, in reaching an agreement with the Troika in late February 2015 to extend the second Memorandum of Understanding, never showed evidence of the slightest determination to take action if the creditors refused to make concessions. And the latter gave every evidence of contempt for Greece’s government.

Most important, says Toussaint, the Syriza government ministers did not take the time to go out and meet the Greek people, to speak at rallies where the Greek population was represented. They did not travel around the country to meet and talk with voters and explain what was going on during the negotiations or the measures the government wanted to take to fight the humanitarian crisis and re-start the country’s economy. They utterly failed to appeal to the working people of Europe and elsewhere for support. Instead, Varoufakis and the other Greek ministers involved to conduct ‘secret diplomacy’ in rooms, thus encouraging the Troika to “persist in using the worst forms of blackmail.”

The referendum of 5 July 2015 was the culmination of those negotiations. Clearly, Tsipras expected the Greek people to bow to the pressure of the media and the threat of economic disaster and expulsion from the EU by accepting the Troika demands. But they did not. Toussaint says that the referendum results was a perfect opportunity to mobilise the Greek people to reject the Troika’s blackmail, refuse their ultimatums and instead respond by suspending further repayments of debt pending an audit. The government should have announced the nationalisation of the banks and implemented capital controls to stop capital flight and take control of the payments system.

As Toussaint points out: “When a coalition or a party of the Left takes over government, it does not take over the real power. Economic power (which comes from ownership of and control over financial and industrial groups, the mainstream private media, mass retailing, etc.) remains in the hands of the capitalist class, the richest 1 per cent of the population. That capitalist class controls the state, the courts and the police, the ministries of the economy and finance, the central bank, the major decision-making bodies.”

That was ignored or denied by the Syriza governemnt, including its rockstar finance minister. They started from the premiss that representatives of capital in the Troika could be persuaded to be reasonable, to act as adults. The class nature of the struggle was omitted. As Toussaint says: “In reality, a major strategic choice of the Syriza government–one which led to its downfall–was constantly to avoid confrontation with the Greek capitalist class. It was not simply that Syriza and the government did not seek popular mobilization against the Greek bourgeoisie, who widely adhered to the EU’s neoliberal policies. The government openly pursued policies of conciliation with them.”

Toussaint offers an alternative strategy in his book. The Syriza government “should have resolutely followed the path of disregarding the European treaties and refusing to submit to the dictates of the creditors. At the same time they should have taken the offensive against the Greek capitalists, making them pay taxes and fines, especially in the sectors of shipping, finance, the media and mass retail. It was also important to make the Orthodox Church, the country’s main land owner, pay taxes. As a means of reinforcing these policies, the government should have encouraged the development of self-organization processes in existing collective projects in various domains (for example, self-managed health dispensaries to deal with the social and humanitarian crisis or associations working to feed the most vulnerable people.”

That brings us to the issue of Greece’s membership of the European Union. Up to the point of the referendum, apart from the Communist party, no party stood for leaving the EU as a solution to the crisis. The vast majority of Greeks did not want this. After the capitulation of Syriza, the party leadership split and those opposed to the capitulation (with the exception of Varoufakis) called for Grexit as the main policy proposal and solution. In the subsequent election, these factions failed to make any headway into parliament and the Tsipras government was returned intact.

In his book, Toussaint reckons that the Syriza government should have opted for triggering Article 50 in the EU constitution as a way of getting out of the EU. This Article is what the UK government subsequently used to achieve its exit after its referendum to leave in 2016. Toussaint reckons that using this instrument would have given Greece two years to argue the toss with the EU, while it refused to pay any more debt etc. I am not so sure that this would have been a good tactic. As Toussaint points out, no EU member state can be thrown out and there are few sanctions that the EU could impose on a Greek government anyway, apart from the ECB blocking credit, something they were doing anyway. By applying for Article 51, Syriza would have been telling the Greek people that the government aimed to leave the EU voluntarily (something the majority of Greek did not want); and also giving the EU leaders an easy way out of getting rid of Greece, something that, as Varoufakis points out in his narrative, German finance minister Schauble was keen on doing.

In my posts during the Greek crisis, I argued that the Syriza government should have refused to pay the debt; taken over the banks and large Greek companies, mobilised the people to occupy the workplaces and introduce workers control; blocked the movement of funds by the rich and corporates; and appealed to the labour movement in Europe for support against the policies of their governments. Let those governments try to throw Greece out; but do not give them constitutional weapon to do so.

The main emphasis in Toussaint’s book is on the role of Varoufakis, not because of any personal animosity, but because this ‘erratic Marxist’, as Varoufakis calls himself, was at the centre of events and went on to write his best-selling personal account of what happened. Varoufakis then formed a pan-European wide political party DIEM 25, and was eventually re-elected as an MP in the Greek parliament in the recent 2019 election that led to the Conservative party taking back power.

Why did Varoufakis from the beginning as finance minister adopt the strategy of trying to persuade the Troika leaders to be reasonable, rather than mobilise the Greek people for a fight against the Troika demands? The answer, I think, lies in Varuofakis’ view of the possibilities for socialism. Before he was appointed finance minister by Tsipras, he had not been a member of Syriza; he had been an academic. Back then, he wrote, “You see, it is not an environment for radical socialist policies after all. Instead it is the Left’s historical duty, at this particular juncture, to stabilise capitalism; to save European capitalism from itself and from the inane handlers of the Eurozone’s inevitable crisis”. He had written what was called a Modest Proposal for Resolving the Euro Crisis with Social Democrat academic Stuart Holland and his close colleague and friend, post-Keynesian James Galbraith, in which Varoufakis was proud to say “does not have a whiff of Marxism in it.”

This ‘erratic Marxist’ saw his task as Greek finance minister “to save European capitalism from itself” so as to “minimise the unnecessary human toll from this crisis; the countless lives whose prospects will be further crushed without any benefit whatsoever for the future generations of Europeans.” Apparently, for Varoufakis, socialism cannot do this because “we are just not ready to plug the chasm that a collapsing European capitalism will open up with a functioning socialist system”. By ‘we’, he means working people, but in practice he meant himself.

Varoufakis went further. You see, “a Marxist analysis of both European capitalism and of the Left’s current condition compels us to work towards a broad coalition, even with right-wingers, the purpose of which ought to be the resolution of the Eurozone crisis and the stabilisation of the European Union… Ironically, those of us who loathe the Eurozone have a moral obligation to save it!” Thus he campaigned for his Modest Proposal for Europe with “the likes of Bloomberg and New York Times journalists, of Tory members of Parliament, of financiers who are concerned with Europe’s parlous state.”

In Sellouts in the Room, Eric Toussaint scathingly exposes this wrong-headed approach of the ‘erratic Marxist’. It’s a painful read in many ways, as Toussaint chapter by chapter recounts Varoufakis’ sorry progress, or lack of it. In a recent interview, Varoufakis was asked “what would I have done differently with the information I had at the time? I think I should have been far less conciliatory to the Troika. I should have been far tougher. I should not have sought an interim agreement. I should have given them an ultimatum: “a restructure of debt, or we are out of the euro today”.

Unfortunately, there is never much benefit in hindsight, except to to avoid the same mistakes when another opportunity arises. Toussaint’s book is a guide to that. In the meantime, the Greek people now face yet another round of austerity and depression after the coronavirus crisis, following the terrible years before and after the capitulation of 2015. The IMF forecast for 2020 would take Greek national income back to the level of 25 years ago!

May 25, 2020

Coronavirus, the economic crisis and Indian capitalism

Here we are, on the 30th of April, with a recession around the world, where there are now millions of cases of coronavirus which has hit almost all regions, making it a pandemic. We also have an increasing number of deaths, particularly in the United States and Europe. The number of cases is also increasing in other parts of the world — in Latin America, Asia, and to some extent, also in Africa. Clearly, the disease is spreading across the world and it is not over yet. We need to analyse what it means and also how it is impacting the economy.

With this particular virus, the question that is often asked is if it is really like a flu or if it is no worse than a flu. We have the flu every year, at least in the northern hemisphere and also elsewhere, usually in the winter period. Lots of people die from the flu, particularly elderly people and influenza remains, among other diseases, important contributor to annual deaths in the world. Some people argue that the current coronavirus is much like the flu. The first thing to say is that all these pathogens including flu have become much more prevalent in the last decade or so because of the increasing connection between the human beings into the remote parts of the world including forests, which are home to wildlife, particularly wildlife that has held many of these pathogens for thousands of years.

Now through the inexorable expansion of human activity — logging, fossil fuel, exploration, urbanisation in general — these wildlife species carrying these pathogens have come much closer in contact to human beings. It is spreading through industrial farming of animals in closed areas, which has led to these pathogens transmitting themselves from the wildlife to industrial farmed animals into human beings. We know this particular virus started, it seems, in a wild life market or at least in an area around the wildlife market in Wuhan in Hubei province in China. This is not just the case of China but elsewhere also with the development of markets. But why are there wildlife markets? Often because poorer people find it difficult to get food from the industrial farming process and they look to other ways to provide them with sufficient food. Wildlife catching has also become a market under capitalism and has become more prevalent which has led to the risk that these pathogens will spread in human beings as they clearly have done.

And it is not like the flu. We look at the infection rate of COVID-19, its 2-3 times more infectious that the annual flu. It incubates over a longer period which is dangerous because it means we don’t know it is happening until it has already hit us and it has spread around. The hospitalisation rate for COVID-19 is much greater than it is for flu, maybe 6 or 7 times more. As far as we can tell, the fatality of infected people on a global scale is coming in after the lock down at about 1%, maybe a little less. But if the pathogen was to spread to the mass of the population at a 1% mortality rate, at a rate of infection 6-10 times more than the annual flu, then millions of people are likely to die.

Now, this disease and other pathogens have been brought to the attention of the governments around the world for some time. We can go back several years but the WHO has been warning the danger of these pathogens turning into pandemics around the world and infecting human beings. But governments have really ignored this. They have taken the chance that nothing is going to happen, and it is not going to be dangerous and they don’t need to prepare or spend any money on it. Just only in September the UN Global Preparedness Monitoring Board pointed out that preparation by governments is totally inadequate and a pandemic is coming, and unless they do something about it and get ready, the health systems are going to be overwhelmed and could escalate into a disaster. Well, here we are just a few months later in the middle of such a disaster.

At the same time, it is worth considering that over the last 10 or 15 years when these pathogens have become much more serious and spread on a pandemic basis, nothing is really being done to use resources to find out more about them and to prepare the vaccines that could save us from serious illnesses and diseases around the world. Vaccine is obviously the answer but there is no vaccine for this virus. A universal vaccine for influenza — that is to say, a vaccine that targets the immutable parts of the virus’s surface proteins — has been a possibility for decades, but never deemed profitable enough to be a priority.

Big pharma does little research and development of new antibiotics and antivirals, although this is what benefits public health. Of the 18 largest US pharmaceutical companies, 15 have totally abandoned this field. Heart medicines, addictive tranquillisers and treatments for male impotence are the profit leaders and very little attention is given to defences against hospital infections, emergent diseases and traditional tropical illnesses. Hence, part of the problem has not only been that the governments did not care, but also that research has not been done by the big capitalist pharmaceutical companies around the world because it is not profitable.

Sober-minded epidemiologists suggest that somewhere between 20% to 60% of the world’s adult population could catch this virus. The death rates are very dependent on the level of lock down, but is certainly coming in at around about 0.5 – 1% of everybody who is infected probably by the time we get to the end of it. While the exact death rate is not yet clear, the evidence so far does show that the disease kills around about 1%, making it ten times more lethal than the annual flu.

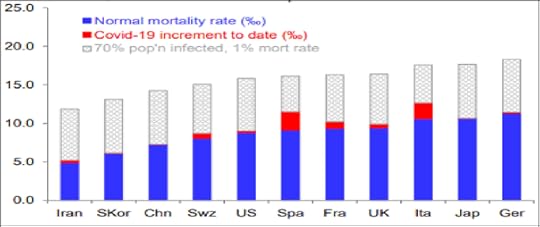

That sort of level of cases and hospitalisation is overwhelming or likely to overwhelm most healthcare systems in the world as is proved to be the case, because they will have no capacity for dealing with this. No testing, no contact and trace, and no ICU beds sufficient to deal with a huge increase in the number of people becoming ill and needing hospital treatment, particularly old people who can hardly move very much. Since there is no vaccine to combat it, nor any approved therapeutics to slow the course of its toll on the human body, current the situation could continue for some months or even longer ahead. Here is a graph (Fig. 1) which makes the point clearer.

Fig.1: Mortality Rates

Fig.1: Mortality RatesThe blue part of this graph is the normal annual mortality rate in various countries. And you can see how many people died in a year per thousand population in these countries. If this pandemic is allowed to spread without any containment, any control or without any protective measures, then the number would more than double in many countries or at least double the amount of people who would die. Depending on how far up the dotted white bit you can go to the top, you could have 35 – 50 million deaths in this pandemic. But of course, that is not what has happened. Health systems and governments everywhere have desperately tried to contain the impact of the pandemic. The little red block (in the graph) shows how successful they have been. If you take Spain or Italy, you can see they have not been that successful and the number of deaths has been way above the normal rates. In fact, only this week, figures are now coming out across the board in many parts of the world how much increase there has been in excess deaths over the normal annual deaths, even with the lock down and containment policies.

Another argument presented often is that only the old and the sick die from this pandemic. 80% or more deaths are above 70 years and if you are a child up to 9 years there are no deaths. Right up until you get to 50 or so, number of deaths are very less, even among those hospitalised. Vast majority of people infected would show no symptoms at all and if they do it is very mild. So, what is all the fuss about, is the argument.

Let us leave aside the question of whether it is right to let the old and the sick die, which within the financial circles I work in, a lot of financial executives and people who advice governments and so on, quietly and privately, seem to agree upon. They argue that if all the old people and sick people died from the pandemic, we can boost productivity, because these people cost us money and they produce nothing. In some ways it would be better if they were “culled” from the world, so that we have a more productive human population. This is an old theory of Thomas Malthus from the early 19th century, that there was no way to improve the lot of the majority of people, because there were too many people and it was better to let plagues and other things “cull” all the unfit and you would have a more productive workforce. And that had to be done progressively.

This disgusting and grotesque theory still has an echo, even now, among people who claim that it does not matter if the old and sick die and we should do little about it and let the young people just be infected. However, that is not a view that is possibly politically acceptable for any government, and moreover health systems would be overwhelmed, disrupting their ability to deal with existing patients and people with other illnesses; and probably causing an increase in such secondary mortality rates (and this time in younger fitter people too), especially in countries more severely affected.

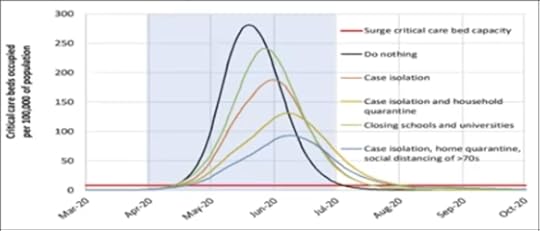

The efforts therefore have been to try and “flatten the curve”, as it is called. In other words, if you look at this graph (Fig. 2) the black line tells that if nothing is done, you are going to have a massive increase in the number of beds that you need compared to the red line at the bottom which is what most countries have got. There is a massive difference.

Fig. 2: Curve Flattening

Fig. 2: Curve FlatteningTherefore, you have to contain this in some way otherwise there will be people dying in beds outside hospitals all over the place. Containment can mean anything from social isolation, isolating and quarantining infected people and shielding the old, going further and start closing schools and universities down, to going all the way down to a total lock down of all economic and social activity and movement which is represented by the blue line that is the flattened curve. The latter means that the infections are reduced, spread out over a longer period and hospitals can therefore cope and therefore not many people will die. But of course, going all the way into a lock down is a serious disaster. If a country had full testing facilities and staff to do ‘contact and trace’ and isolation; along with sufficient protective equipment, hospital beds including ICUs, then containment along these lines would work — without significant lockdown of the economy.

Only a very few countries have been able to achieve enough testing. Countries that have done the best have used contact and trace and so on, and have been able to suppress the spread of this infection and reduce the cases. Some of the biggest countries of the world have done the least testing and are at the bottom of the table, as they did not have such testing facilities, and therefore have been unable to operate any testing basis. Also, they have not had the required hospital space because most health systems in the last 30 years have drastically reduced their spending on facilities and staffing in order to save money for governments so that they can spend it on other things such as weaponry or helping capitalists profit. They are not prepared to provide decent healthcare across the board. As a result, there is no spare capacity. Any crisis like this then just becomes overwhelming.

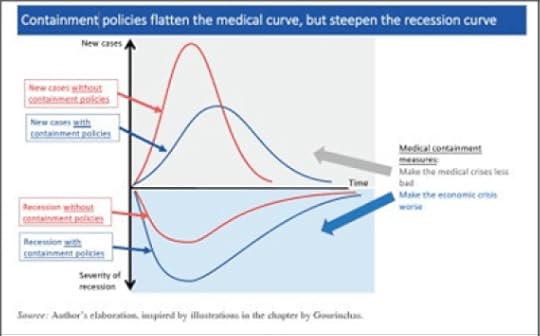

The only solution then is to flatten the curve by a huge lock down of everything that is moving. This graph (Fig. 3) produced by another Marxist economist in Greece, demonstrates the trade off now between lives and livelihoods as a result of this crisis. The more you flatten the curve on the health front (red to blue on the top part), the more likely you are to widen and increase the negative curve below for the economy (red to blue at the bottom part). Heavier the lock down to flatten the curve, the more you are going to have a recession and a collapse in the economy.

Fig. 3: Trade-off Between Lives and Economy

Fig. 3: Trade-off Between Lives and EconomyLock down and economic slump

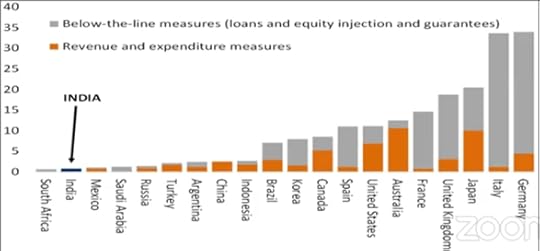

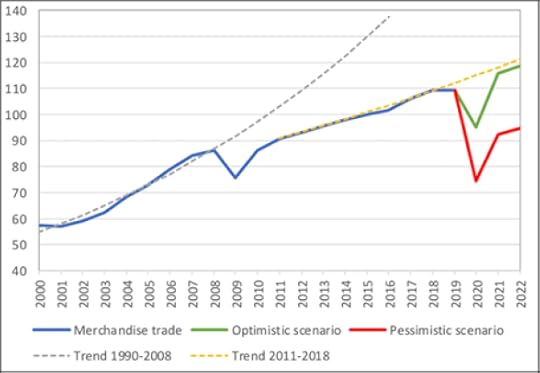

We are currently in a lock down and a slump. We just had figures earlier this week showing the United States down around about 5% in the first quarter and we have not even gone into this quarter which is going to be much worse. Europe too is down by 3 – 5 % depending on the country and we are going to see even worse figures. 2.7 billion workers are now affected by full or partial lock down measure, representing around 81% of the world’s 3.3 billion workforce, and they are now facing a massive reduction in their income and employment. Any sort of measure we have had from the IMF, World Bank, OECD and the private forecasters are projecting anywhere around a 5% reduction in the global GDP this year which will be way more than the global recession of 2008.

That was called the Great Recession, this will be even greater in its damage to the world economy. Outputs in most sectors will fall by 25% or more according to OECD, and the lock down will directly affect sectors amounting up to one third of GDP in the major economies. For each month of lock down, there will be a loss of 2% in annual GDP growth. This short could exceed any collapse in global output that we have seen in the last 150 years! IMF projects that over 170 countries would experience negative per capita income growth this year. This is how severe the situation is.

Of course, the hope is that the collapse will only be short. Just a couple of quarters and then everything will be brought into control and we can recover and go back forward. The stock market in the US is rocketing upwards for two reasons; i) US Federal Reserve has intervened to inject humongous amounts of credit through buying up bonds and financial instruments so that banks and institutions can keep their heads above water and, ii) they believe that this lock down will be over soon and then world economy will recover and it will be back to business as usual. We will see whether that turns out to be the case over the next few months. This is in stark contrast with the figures we are seeing about the collapse in the real economy in terms of national output, investment and employment, in all sectors. But the stock market thinks things will soon be fine and they are looking over the drop into the next mountain hoping everything will be up and away again.

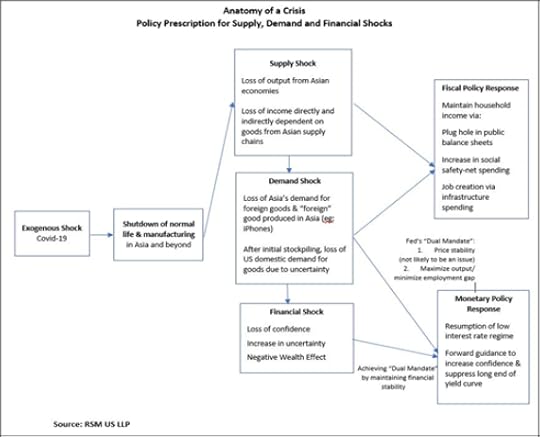

The current situation is one of a huge supply shock. The following figure shows (Fig. 4) that this is not a financial collapse of the banks and the financial institutions like we had in the Great Recession. It starts on the other end, as a supply collapse. We have this so-called exogenous shock. I don’t think it is a shock because we should have predicted these pandemics and done something about it, but it led to a shutdown of normal life and manufacturing. This huge supply shock has now spread to demand because if you are locked down at home, you cannot spend any money or perhaps you haven’t got any money to spend. This demand shock could feed through eventually into a financial collapse with companies that cannot sell going bust and then banks who lend them money also getting into trouble. At the moment the central banks are trying to shore-up that bottom block (on financial shock) in this figure. But they have not been able to do anything about the demand shock or the supply shock which exist.

Fig. 4: Anatomy of a Crisis

Fig. 4: Anatomy of a CrisisAbove all, what this demonstrates, to bring a short quote from Marx, is that what matters in an economy is the workers working. As Marx said: “Every child knows a nation which ceased to work, I will not say for a year, but even for a few weeks, would perish” (Marx to Kugelmann, London, July 11, 1868). This is obvious now.

I live in the UK and work in the financial circles and I was trying to ask myself what are the important things that make our economy work and keep us going forward? Who are the workers that matter? Workers that matters are the health workers, the teachers, the drivers, the manufacturing workers, service workers of all sorts, retail shops and so forth. What occupations do not matter? Finance executives, real estate executives, hedge fund managers, advertising executives and marketing executives. When all these people stop work, we would not even notice. But when the workers that matters stop work, we really do notice. It is something worth remembering when you are thinking about who creates the value in our world, in order to provide for the things, we need and the services we require.

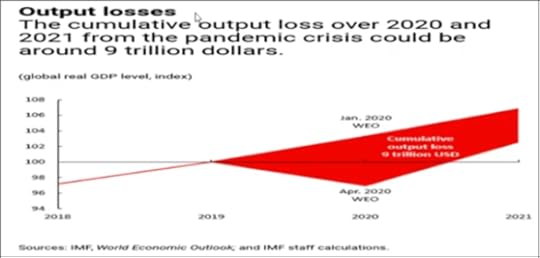

As mentioned, we have this massive lock down across the world and a huge loss in production in most countries if not all. The red section in the below graph indicates the loss of production that is taking place now. Even if the economy starts recovering in 2021, this loss can never be recovered. Once you have that loss of output, employment and incomes, the gap remains permanently. It is like digging a hole in a ground that you can never fill again. You just have to climb over to the other side and the hole is still there. All those resources are being lost to people around the world particularly the people who needed it the most, the poorest people.

Fig. 5: Output Losses

Fig. 5: Output LossesIn particular, it is the so-called emerging markets that are taking a real tumble. For the first time, since records have begun, the total amount what is called the emerging markets or developing markets in the world are going to see a slump, on average across the board. That includes China and India, for the first time. If we take out China and India out of the emerging markets, we get a relatively low growth rate. But now even including them, we are going to have a slump in this year coming through as a result of this collapse in the world economy and lock downs.

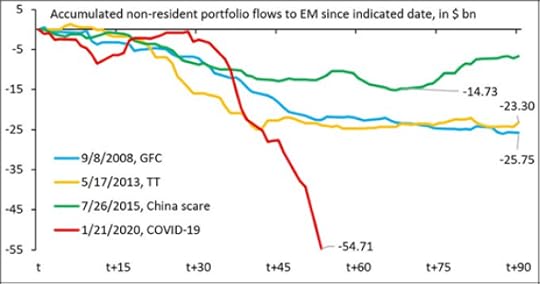

There has been a massive flight of capital away from the poorer countries (Fig. 6) who depend, in the capitalist system, on the inflow of capital from the big companies and financial institutions. The investors have taken all their money back to where they brought it from and something like a 100 billion dollars have disappeared from the emerging economies. This means they have no credit and facilities in order to expand and it adds to the danger of their own currencies, financial institutions and companies collapsing as a result of flight of the private capital, which is not being replaced by any public capital. The IMF and the World Bank is giving some money, but on the whole, there is no international coordination from the richer countries to help the poor counties in this crisis. They have just been left to fend for themselves and indeed the only way they get some money is by taking out more debt and loans which could put them in even more difficult problem later on as we shall see.

Fig. 6: Capital Flight

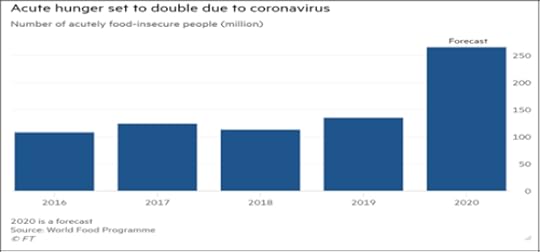

Fig. 6: Capital FlightMillions of jobs have disappeared globally according to the ILO. The COVID-19 crisis is expected to wipe out 6.7% of working hours globally in the second quarter of 2020 – an equivalent of 195 million full time workers. The labour income loss is around 3.5 trillion dollars (maximum) in 2020. Hence, huge amounts of people are going to be pushed back into poverty. According to Oxfam, under the most serious scenario – a 20% contraction in income – the number of people living in extreme poverty would rise by 434 million to 932 million worldwide. The same scenario would see the number of people living below the US$ 5.50/day threshold rise by 548 million people to nearly 4 billion. Even at more acute level, we are entering a real danger of millions of people just being hungry, starving to death, in a way that should not happen in 21st century. It happens anyway as we have seen in years before (Fig. 7), but we are going to see a doubling of the number of people who are basically in a position of starvation over the next year or so.

Fig. 7: Food Crisis

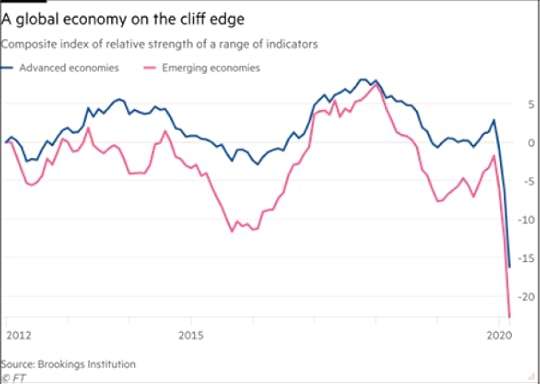

Fig. 7: Food CrisisThere are some who argue that the lock down is solely to blame for the economic crisis. But we ought to realise that the capitalist economy on a global scale was not doing very well even before we got to this pandemic. It was on a sharp slowdown. Europe was more or less stagnant, Japan was in recession, many important economies in the global south like Argentina, Mexico, Turkey and South Africa were in a slump already and even the US was beginning to slow down to a very low rate.

It has been the longest expansion in the history of the US economy since the Great Recession ended in 2009 but it has also been the weakest expansion. Growth has hardly been more than 2% in the US, less in Europe and Japan, and only the emerging economies like India and China has had a reasonable growth rate. Most emerging economies have also had a very poor growth rate compared to the position before 2009. So this has been a very weak growth and it was beginning to come to an end. It was on a cliff edge.

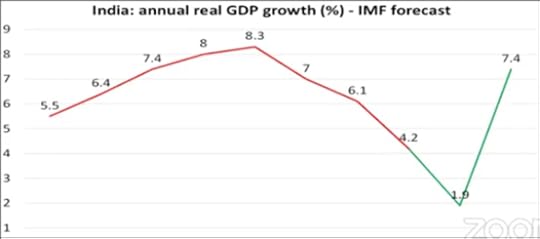

From the graph (Fig. 8) we see that growth was beginning to slowdown, both in emerging and advanced economies, and then we had the pandemic and now it has just dived off the edge of that cliff. But it was already reaching there. I want to make that point because some claim that it was all just a bolt out of the blue. It is not, as most economies were getting weaker and they were not ready to deal with this pandemic.

Fig. 8: Global Growth Trend

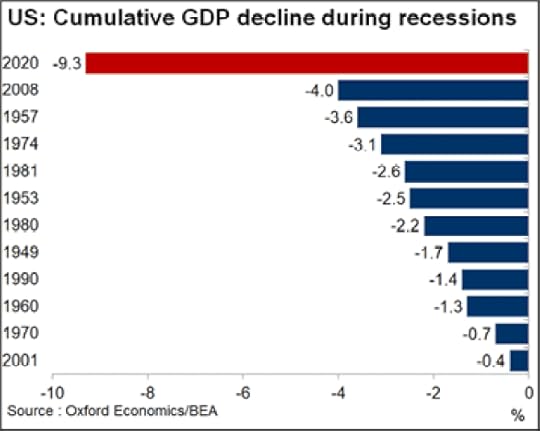

Fig. 8: Global Growth TrendIf we take the US, something like a 10% fall in GDP over the next year or so as a result of the pandemic would happen at the minimum. That will be the largest decline since 1930’s and way more than anything seen even in the Great Recession of 2008-09 (Fig. 8).

Fig. 9: US GDP Decline

Fig. 9: US GDP DeclineWhy have most major economies been weak? The answer in my view, something which I am always trying to bring home to people in my work, is that underneath the movement of outputs and incomes, the key question for a capitalist economy is whether it is profitable to produce, invest and employee people. That is the only reason they produce things. The big motor car companies around the world do not produce cars just because people want them, but they only produce if it makes profit for them to do so. That is the nature of the capitalist economy. They compete with each other to get a bigger share of the market and bigger amount of profit and they use their workforce to try and keep the cost production down as much as possible in order to make a profit, to accumulate that profit, partly to reproduce new things but also to have a good life and be a billionaire.

So, profitability is key to capitalism. Below figure (Fig. 10), shows the profitability of major economies over the last 50-70 years. You can see that on the whole profitability is really quite low compared to what it was back in the 1960’s. There was a big fall followed by some recovery during the last 30 years and workers really had to take a hit for it.

Fig. 10: IRR on Capital

Fig. 10: IRR on CapitalNow profitability was extremely weak as we led up to this crisis, and it suggests that they were in no position to cope with a major collapse in the health systems and economies. In fact, if we look at total global corporate profits (Fig. 11)and not just the amount of profits per investment (i.e. profitability), we see that the total amount of profits had ground to a halt in the major economies as we entered the pandemic. The world economy was already about to enter a slump of some proportion but now of course the pandemic has worsened the slump.

Fig. 11: Trend in Global Corporate Profits