Michael Roberts's Blog, page 40

January 2, 2021

Forecast for 2021

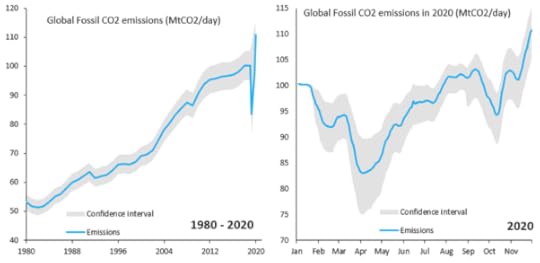

This time last year, I started my post on the forecast for 2020 by making a distinction between predictions and forecasts. I argued that we can make predictions that can be tested, say about the climate and global warming. Climate scientists predict that if carbon emissions keep rising, then global temperatures will keep rising and eventually cause damaging changes in the earth’s climate (and it is happening). Indeed, virologists have been predicting for some time that there would be a wave of pandemics from new pathogens reaching humans.

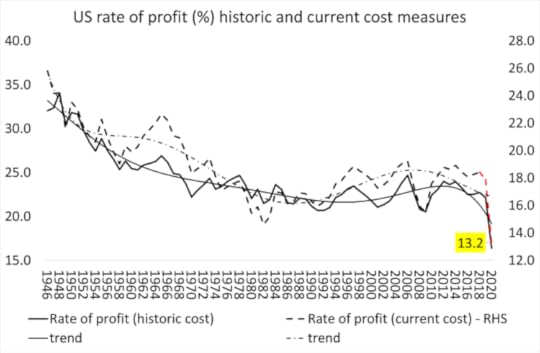

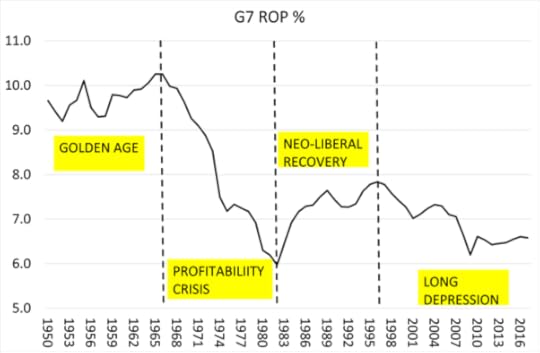

Similarly, in social sciences, we can make predictions, if with more difficulty. In Marxist economics we can make predictions from Marx’s law of accumulation of capital and from the law of tendency of the rate of profit to fall. The first law argues that the organic composition of capital will rise over time (and it does in capitalist economies); and the second law predicts that the average rate of profit on the stock of capital invested by capitalists will fall over time (and it does).

But that’s not the same as making forecasts on what will happen, say, over the next year. Weather forecasting is unpredictable; although the three-day forecast has got pretty good. In economics, forecasting whether an economy’s real GDP growth, employment, incomes and investment will rise or fall and by how much one year ahead is even more unreliable.

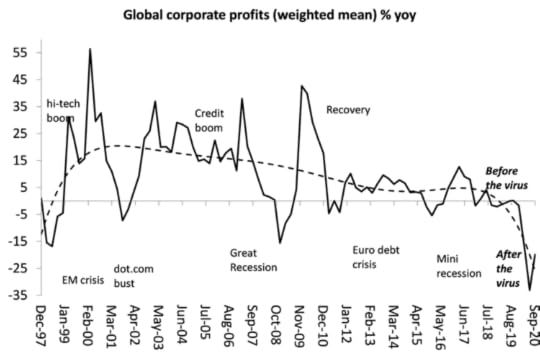

However, each year I attempt to do this for the major economies. Last year, I tentatively forecast that the major capitalist economies were heading for a new slump in production and investment for the first time since the end of the Great Recession. The period from mid-2009 to the end of 2019 was the longest period of expansion for the advanced capitalist economies since 1945 (although several large so-called ‘emerging economies’ like Mexico, Argentina, Brazil and Russia were already in recession and so was Japan). But it was also the weakest post-war expansion, with average real GDP growth no higher than about 2% a year, investment stagnating and profits beginning to fall. That was my argument for an impending slump in 2020.

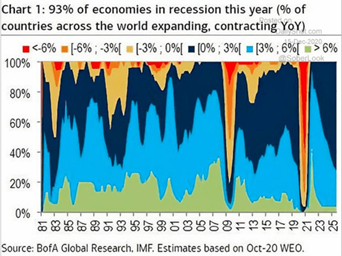

Of course, we could predict a pandemic was coming but not forecast when and where COVID-19 would emerge. The COVID pandemic put all previous forecasts out of the window. Now ,as we look back at 2020, the world capitalist economy has recorded the biggest and widest slump in its history, with near 95% of economies suffering a contraction in national output, investment, employment, and trade.

Very few countries have avoided a slump in 2020, specifically, China, Vietnam, Taiwan – and that’s about it.

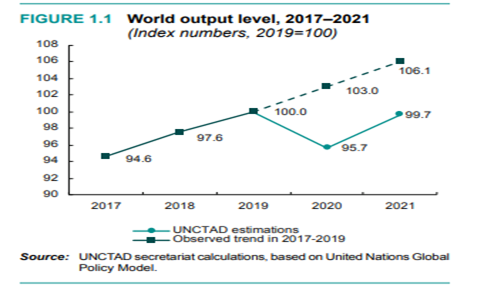

In one way, as a result, making an economic forecast for 2021 has been made easier. Most countries will recover this year. Real GDPs will grow, unemployment rates will start to decline and consumer spending will pick up. That’s partly just stats. If an economy drops 10% from, say 100 to 90 in one year, and then recovers to 95 in the next year, that’s a 5.5% rise. But, of course, the economy is still some 5% below the pre-slump level of 100. Moreover, if the economy had not entered a slump, it may have risen by say another 2-3% in a year, so even after the recovery, that economy could be some 6-7% below trend.

And that is what is going to happen in most economies in 2021. With the vaccines (gradually) being distributed, by the summer large numbers of people will be ‘protected’ from the virus (in all its variants?) – although countries in the ‘global south’ don’t have the financial and logistical resources to vaccinate their populations who may have to wait until 2024! Nevertheless, the G7 economies should be recovering significantly by mid-year, at least on the stats.

But this will be no V-shaped recovery, which means a return to previous levels of national output, employment and investment. As I have just argued above, by the end of 2021, most major economies (China excepted) will still have levels of output etc below that at the beginning of 2020. Indeed, most forecasts by the likes of the IMF, World Bank and the OECD (as I have recorded in previous posts) do not expect the major economies to return to pre-COVID levels before the end of 2022 and many will never catch up to the previous trend growth (which was already weak). That’s why I call the shape of this global ‘recovery’ a reverse square root, where the new trend growth in output, investment and profitability will remain below the previous trend growth rate.

Why? Well, there are three main reasons. First, there has been ‘permanent scarring’ to most capitalist economies. During the lockdowns of 2020, many companies, especially smaller ones in the services sector, will not return and the jobs that go with them will disappear. Also, many workers who have been furloughed or sacked may not get their jobs back as companies look to reduce staff and not re-employ older, more expensive workers.

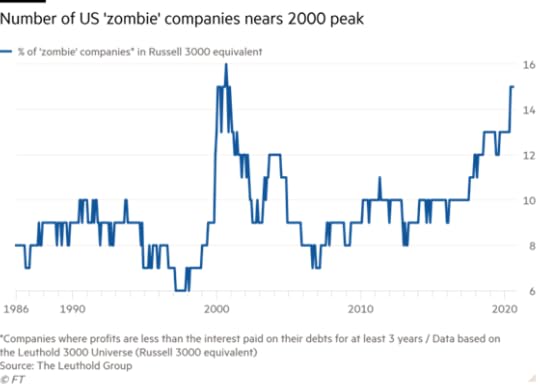

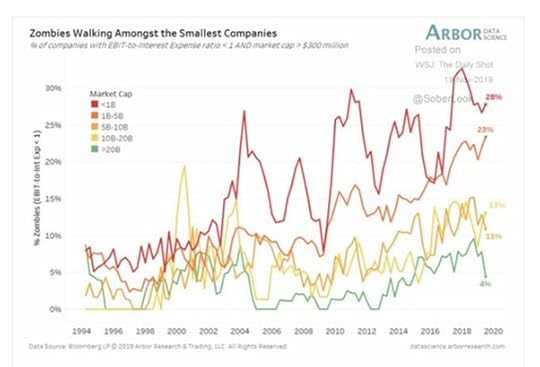

Second, there is the rise in corporate debt that will weigh down on the ability of many companies (and not just small ones) to resume investment. Previous posts have talked about the rise of ‘zombie companies’ in the major economies. With interest rates driven down to the level of inflation and below by the huge injections of credit money by the main central banks, and with government guaranteed credit programmes, companies have sharply increased their debt levels during the COVID pandemic lockdowns. The large companies have hoarded the government-backed money or invested it in buying back their own shares or in financial assets. The stock markets of many countries have rocketed to all-time highs as a result. However, many smaller companies have had to use extra borrowing to survive. The costs of servicing their debt has plummeted but the amount of debt has spiralled.

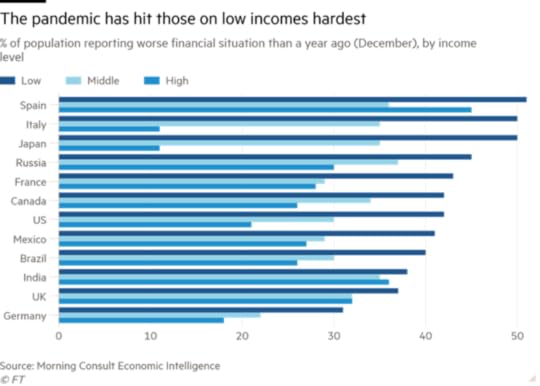

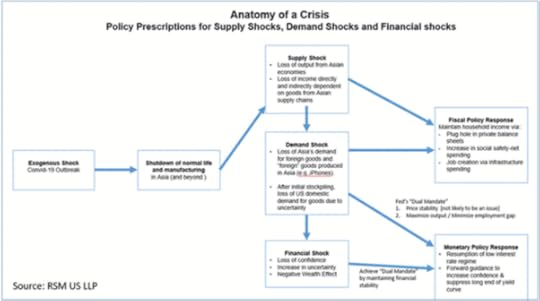

Indeed, there is a real risk of a third leg in the pandemic slump. The slump started with what we could call a ‘supply shock’, as businesses closed, travel stopped, people stayed at home and service sector industries were paralysed. Then it became a ‘demand shock’ as spending on services, leisure, travel and other ‘unnecessaries’ plummeted. Incomes for the better paid professional and office-based workers who could work from home stayed up while lower paid, unskilled workers who had to go out to work saw their jobs disappear. Up to 40 per cent of those in the top income brackets of the major economies were able to work from home during the pandemic, more than double the proportion among the lowest earners. The former did not spend so savings rates have rocketed.

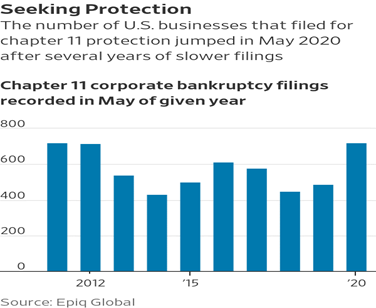

Now if there is a significant layer of companies that go bust (and bankruptcies are rising), then there could be a third leg to the slump in 2021: a credit crunch and financial crisis. Such fears have been expressed by World Bank chief economist, Carmen Reinhart, about emerging market debt defaults (we already have had some); Reinhart warned that the global south faces “an unprecedented wave of debt crises and restructurings”. Reinhart said: “in terms of the coverage, of which countries will be engulfed, we are at levels not seen even in the 1930s.”

And the so-called Group of Thirty bankers issued a report recently that warned of such a crunch and urged immediate action to avoid it. They warned that “while illiquidity has characterized the Covid-19 economic crisis heretofore, insolvency may come to bear on many businesses as economic strain from the pandemic continues.” Even cheap credit is not enough to enable the ‘zombie’ companies to recover. Zombie firms are sitting on an unprecedented $2 trillion of obligations.

And that leads to the third reason not to expect a V-shaped recovery that puts global capitalism back on sustained growth. The average profitability of capital in the major economies is at post-war lows, compounded by the pandemic slump.

Unless the slump sufficiently ‘destroys’ enough ‘dead wood’ in the capitalist sector and then allows the strong to replace the weak and boost the profitability of the survivors, the major capitalist economies may stay locked in what has been called ‘secular stagnation’ by Keynesians or a ‘long depression’ by me and some other Marxist economists.

There remain some optimistic voices for 2021 among mainstream economists, as there were at the start of the pandemic last March. Let me remind what some prominent Keynesians said back then. Larry Summers, former Treasury Secretary under Clinton, reckoned that the lockdown slump was just the same as businesses in summer tourist places closing down for the winter. As soon as summer comes along, he said, they all open up and are ready to go just as before. The pandemic is thus just a seasonal thing. Similarly, Keynesian guru, Paul Krugman reckoned that the pandemic slump was not an economic crisis but “a disaster relief situation”. So government spending financed by borrowing would soon put the economy back on its feet. And Robert Reich, the supposedly leftist former Labour Secretary, again under Clinton, also reckoned that the crisis wasn’t economic, but a health crisis and as soon as the health problem was contained (he thought last summer!) the economy would ‘snap back’.

Now the Financial Times has pitched in with its New Year message of hope and recovery. Its economics columnist, Martin Sandbu, argues that 2021 will bring a massive consumer boom as pent-up demand will be released, backed by the high saving built up in 2020 that will now be spent. He likens 2021 to the start of a decade of boom similar to the ‘roaring twenties‘ of the last century. The problem with this forecast is that: first, for many countries, the 1920s were not roaring at all. The UK had a long depression in growth, investment and employment in that decade, while Europe and Japan were in desperate straits, setting the climate for the rise of militarism and fascism.

And second, although there was a boom in the US economy in the 1920s after the end of the Spanish flu epidemic, it did not benefit the bulk of working people. Economic growth accelerated for a few years and the stock market shot to new highs (just as now), buoyed by cheap credit. But while real wages did rise for a while, by about 5-8% over six years (hardly mega), profit rises were much higher as productivity growth outstripped workers wage growth. Inequality rose sharply.

And of course, it all ended in tears, with the Great Crash in the stock market of 1929-30 and the ensuing Great Depression of the 1930s. Sandbu nevertheless urges us to hope. “A century ago, the decade ended badly. We can do better this time — not by reining in the hedonistic release but to make it inclusive. When it is finally time to celebrate, let everyone come to the party.”

The FT concludes that “If there is one reason above all for hope for the future it is that the past year has demonstrated, firmly, our ability to adapt.” Really? Has capitalism adapted or changed? The tremendous efforts of scientists and health workers everywhere have kept down the deaths and illnesses of those infected by COVID-19 and the vaccines have been produced in record time. But the capitalist economy is unchanged.

The big pharma companies are set to make huge profits from the vaccine sales; the fossil fuel companies are continuing to expand their explorations and production. Companies everywhere are out to reduce jobs and conditions for workers. And governments are talking of having to tighten belts on spending and taxation once the pandemic subsides in order to pay for the huge fiscal and monetary spending of the last year. Global warming is resuming, inequality of wealth and income is unchanged and poverty in global south is worsening, while stock markets boom. That’s the prospect for 2021.

December 29, 2020

The Brexit deal

The UK finally leaves the European Union on 31 December, after 48 years of membership. The initial decision to leave, made in the special referendum back in June 2016, has taken over four tortuous years to implement. So what does the deal mean for British capital and labour?

For British manufacturers, the tariff-free regime of the EU’s internal market has been maintained. But the British government will have to renegotiate new bilateral treaties with governments across the world, whereas previously they were included within EU deals. People will no longer be able to work freely in both economies by right, all goods will require significant additional paperwork to cross borders and some will be checked extensively to verify they comply with local regulatory standards. Frictionless trade is over; indeed, that’s even between Northern Ireland and mainland Britain with a new customs border across the Irish Sea.

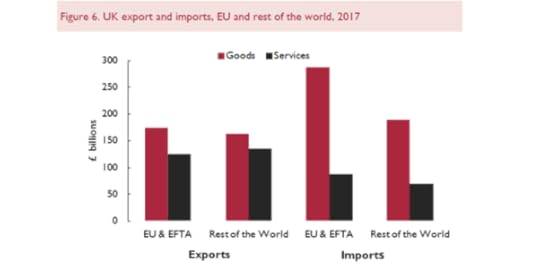

And that’s just goods trade, where the EU is the destination of 57% of British industrial goods. The British government fought tooth and nail to protect the fishing industry (and failed), but it contributes only 0.04% of UK GDP, while the services sector contributes over 70%. Of course, most of this is not exported, but still services exports contribute 30% to UK GDP. And 40% of that services trade is with the EU directly.

Indeed, while the UK runs a huge goods trade deficit with the EU, that is in part compensated by running a surplus in services trade with the EU. This surplus is in mainly financial and professional services where the City of London leads. Exports of UK financial services are worth £60 billion annually compared to imports of £15 billion. And 43% of financial services exports go to the EU.

The Brexit deal with the EU has done nothing for this sector. Professional services providers will lose their ability automatically to work in the EU after the Brexit deal failed to obtain pan-EU mutual recognition of professional qualifications. This means that professions from doctors and vets to engineers and architects must have their qualifications recognised in each EU member state where they want to work.

And the deal does not cover financial services access to EU markets, which is still to be determined by a separate process under which the EU will either unilaterally grant “equivalence” to the UK and its regulated companies or leave firms to seek permissions from individual member states. Over the next year, there may well be bit by bit agreements on trade in these areas. But the UK service sector is bound to end up worse off for its exports than was the case within the EU.

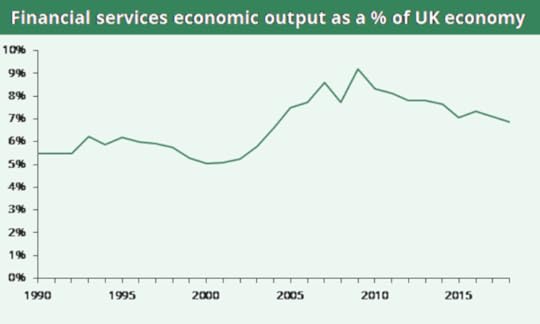

And that’s serious because the UK is a ‘rentier’ economy that depends heavily on its financial and business services sector. Financial services contribute 7% of UK GDP, some 40% higher a contribution than in Germany, France or Japan.

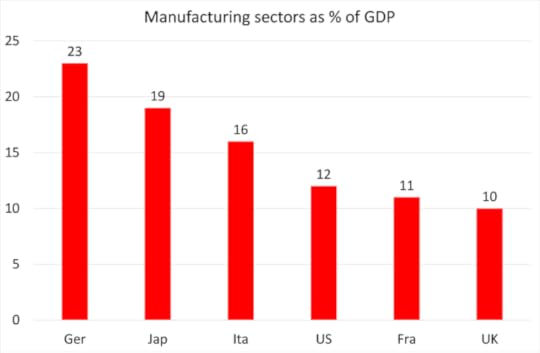

The UK is a country of bankers, lawyers, accountants and media people, rather than engineers, builders and manufacturers. The UK has a huge top-heavy banking sector, but a small manufacturing sector compared to other G7 economies.

What about the impact on working people? On leaving the EU, what little British labour has gained from EU regulations will be in jeopardy within a country which is already the most deregulated in the OECD. The EU rules included a 48-hour week maximum (riddled with exemptions); health and safety regulations; regional and social subsidies; science funding; environmental checks; and of course, above all, free movement of labour. All that is going or being minimised.

Around 3.7% of the total EU workforce – 3 million people – now work in a member state other than their own. Since 1987, over 3.3 million students and 470,000 teaching staff have taken part in the EU’s Erasmus programme. That programme will exclude Britons from now on. Immigration into the UK from EU countries has been significant; but it also works the other way; with many Brits working and living in continental Europe. With the UK out of the EU, Britons will be subject to work visas and other costs that will be greater than the total money per person saved from contributions to the EU.

On balance, EU immigrants (indeed all immigrants) have contributed more to the UK economy in taxes (income and VAT), in filling low-paid jobs (hospitals, hotels, restaurants, farming, transport) than they have taken up (in extra cost of schools, public services etc). That’s because most are young (often single) and help pay pension contributions for those Brits who are retired. The Brexit referendum has already brought about a sharp drop in net immigration into the UK from the EU, down 50-100,000 and still falling. That can only add to the loss of national income and tax revenues down the road.

Most sober estimates of the impact of leaving the EU suggest that the UK economy will grow more slowly in real terms than it would have done if it had remained a member. Mainstream economic institutes, including the Bank of England, reckon that there would be a cumulative loss in real GDP for the UK over the next ten to 15 years of between 4-10% of GDP from leaving the EU; or about 0.4% points off annual GDP growth. That’s a cumulative 3% of GDP loss per person, equivalent to about £1000 per person per year.

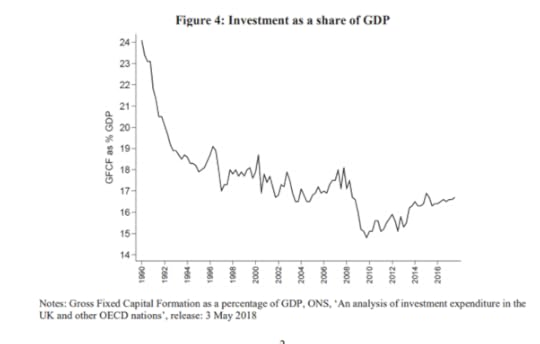

The UK’s Office for Budget Responsibility reckons that one third of this relative loss has already taken place because of the reduction in the pace of business investment since the referendum as domestic businesses stopped investing much, due to uncertainty about the Brexit deal along with a sharp drop in foreign inward investment.

And then of course, the COVID pandemic has decimated business activity. In 2020., the UK will suffer the largest fall in GDP among major economies apart from Spain and recover more slowly than others in 2021.

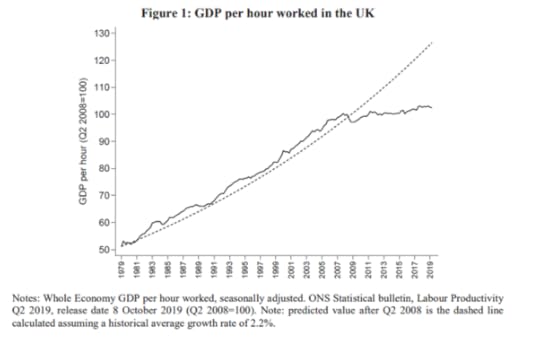

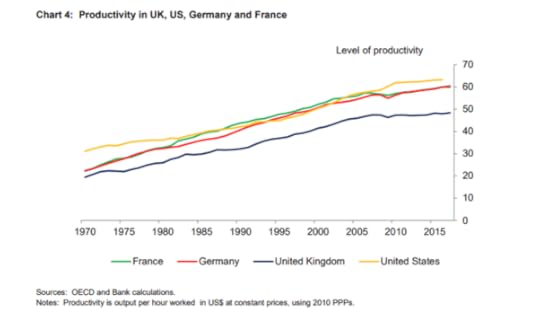

British capitalism was already slipping badly before the pandemic hit. Its trade deficit with the rest of the world had widened to around 6% of GDP; and real GDP growth had slid back from over 2% a year to below 1.5%, with industrial production crawling along at 1%. The UK economy already had weak investment and productivity growth compared with the 1990s and with other OECD countries.

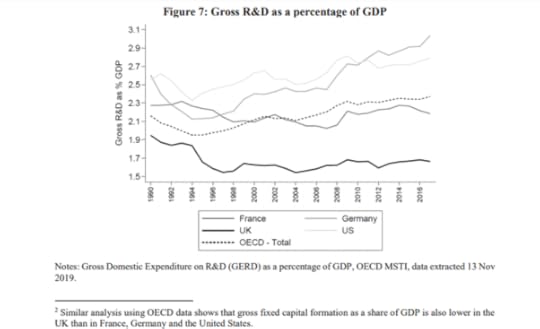

Investment in technology and R&D has been poor, more than one-third less than the OECD average.

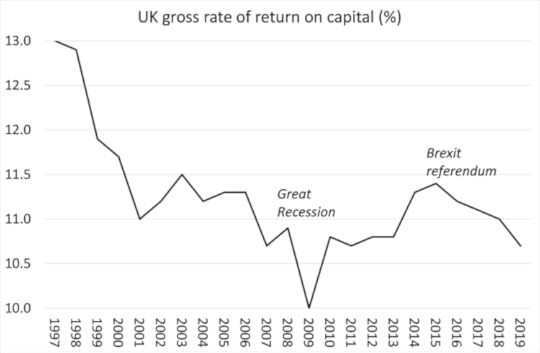

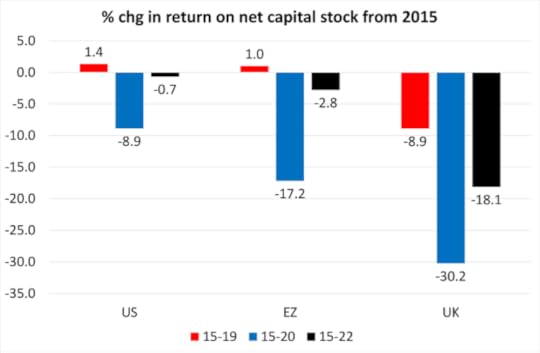

And the reason for this is clear. The average profitability of British capital has been falling. Even before the pandemic hit in 2020, average profitability (according to official statistics) was 30% below the level of the late 1990s and, excluding the Great Recession, was at an all-time low.

Since the referendum of 2016, UK profitability has fallen by nearly 9%, compared to small rises in the Eurozone and the US. And the Eurozone AMECO forecast for profitability will leave the UK 18% below 2015 levels by 2022!

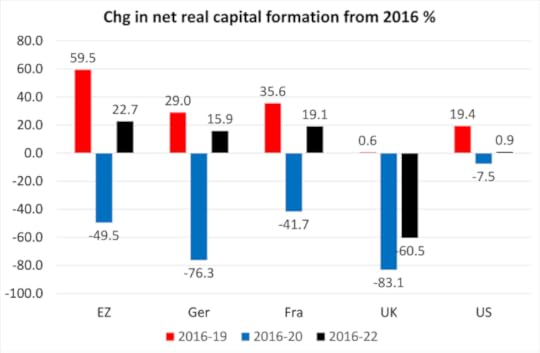

As a result, investment by British capital is set to plunge and is forecast to be down a staggering 60% by 2022 compared to the referendum year of 2016.

But maybe the UK can confound these dismal forecasts, as the government claims, because UK industry and the City of London can now expand across the world ‘free from the shackles’ of EU regulation. And it is increasingly clear how it thinks it can do this – by turning Britain into a tax and regulation-free base for foreign multinationals. The government is planning ‘free ports’ or zones; areas with little to no tax in order to encourage economic activity. While located geographically within a country, they essentially exist outside its borders for tax purposes. Companies operating within free ports can benefit from deferring the payment of taxes until their products are moved elsewhere or can avoid them altogether if they bring in goods to store or manufacture on site before exporting them again.

Unfortunately, for the government, studies show that free ports might simply defer the point when taxes are paid, as imports would still need to reach final customers across the country. And the incentives may also promote the relocation of activity that would have taken place anyway, from one part of the UK to another. Moreover, tax breaks could mean a loss of revenue for the Treasury. And free ports risk facilitating money laundering and tax evasion, as goods are usually not subject to checks that are standard elsewhere. A deregulated Britain will not restore economic growth, let alone good, well-paid jobs for an educated and skilled workforce. It will only boost the profits of multi-nationals, using cheap, unskilled labour.

In sum, the Brexit deal is another obstacle to sustained economic growth for Britain. But the COVID pandemic slump and the underlying weakness of British capital are much more damaging to the UK’s economic future than Brexit. Brexit is just an extra burden for British capital to face; as it also will be for British households.

December 23, 2020

Top ten posts of 2020

As usual at this time of the year, it’s the annual stock take for this blog. This year there have been 670,000 hits on the blog to date. That’s up 45% on 2019, another record! That may not match the millions that hit the sites of mainstream economists but it’s not bad for a Marxist.

I began this blog back over ten years ago. Over those ten years, I have posted 957 times with over three and half million viewings. There are currently 5,300 regular followers of the blog and 10,250 followers of the Michael Roberts Facebook site, which I started six years ago. On the Facebook site, I put short daily items of information or comment on economics and economic events.

And at the beginning of 2020, I launched the Michael Roberts You Tube channel, https://www.youtube.com/channel/UCYM7I0m-I9EVB-5gaBqiqbg/ which currently has 1200 ‘subscribers’. If you haven’t joined up yet, have a look at the channel, which includes presentations by me on a variety of economic subjects; interviews with other Marxist economists; and some zoom debates in which I participated, particularly on the COVID pandemic and on the 200th anniversary of the birth of Friedrich Engels, Marx’s life-time friend and close collaborator.

So what were ten most popular posts on my blog in 2020? Not surprisingly, the various posts on the causes and impact of the COVID pandemic topped the list. In my post, It was the virus that did it, posted last March at the start of pandemic slump, I forecast that:“when this disaster is over, mainstream economics and the authorities will claim that it was an exogenous crisis nothing to do with any inherent flaws in the capitalist mode of production and the social structure of society. It was the virus that did it.”

I argued instead that “even before the pandemic struck, in most major capitalist economies, economic activity was slowing to a stop, with some economies already contracting in national output and investment, and many others on the brink. COVID-19 was just the tipping point.” In that sense, the pandemic slump was “not really a ‘shock’ at all, but the inevitable outcome of capital’s drive for profit in agriculture and nature and from the already weak state of capitalist production in 2020.”

This early post on the pandemic topped the poll with 25,000 hits, but other posts on COVID also got into the top ten.

In an April post, I observed that the coronavirus pandemic marked the end of longest US economic expansion on record, and now would feature the sharpest economic contraction since WWII. I forecast that many companies, particularly smaller ones, would not return after the pandemic. “Before the lockdowns, there were anything between 10-20% of firms in the US and Europe that were barely making enough profit to cover running costs and debt servicing. These so-called ‘zombie’ firms may find the COVID winter is the last nail in their coffins.” I think 2021 will show that to be the case.

My conclusion was that: “The last ten years have been similar to the late 19th century. And now it seems that any recovery from the pandemic slump will be drawn out and also deliver an expansion that is below the previous trend for years to come. It will be another leg in the long depression we have experienced for the last ten years.”

Another popular post was on whether the lockdowns could have been avoided. Last April, I reckoned that they could have been. But they were not because governments ignored the warnings of emerging pandemics, taking a calculated risk that the chance of a pandemic was not high, so there was no need to spend on prevention and containment. Moreover, in the major economies health systems had been decimated of staff and resources or privatised, so they were hugely under-resourced to handle the hospital cases and there was little or no protection for the old and sick in social care. The situation was even worse in the poorest nations. So lockdowns became the only option if lives were to be saved.

In another post on COVID I argued against the idea that there was a trade-off between lives and livelihoods. Some right-wing ‘neoliberal’ experts have tried to argue that the COVID threat was overblown and that jobs and businesses were more important than saving old and sick people (who were already near death anyway). If we let the virus ‘rip’, we could achieve ‘herd immunity’ and the pandemic would subside without any huge damage to the economy.

Apart from the fact that the COVID-19 is way more deadly than annual flu, even if it hits mainly the old, sick and poor, it is now clear that speedy and effective lockdowns as in China, Vietnam, Taiwan and New Zealand can crush the virus and allow economies to recover much quicker than long drawn out ‘lite lockdowns’ that have left most major economies unable to recover. There is no trade-off between saving lives and livelihoods. Indeed, most capitalist governments can’t save either.

Not all of the top ten posts were on the COVID pandemic. Also popular among my followers was the latest data on the profitability of capital – a subject for which this blog is often viewed! It is important because the rate of profit is the best indicator of the ‘health’ of a capitalist economy. It provides significant predictive value on future investment and the likelihood of recession or slump. In a post, I took the opportunity to review my attempts of the past to measure a world rate of profit. A new database, the Penn World Tables 9.1, had developed a new time series called the internal rate of return on capital stock (IRR), which makes a very good proxy for the Marxian rate of profit. Using that database, I confirmed previous results that the rate of profit in the major imperialist economies has been in long-term decline for most of the major and larger economies), with various sub-periods.

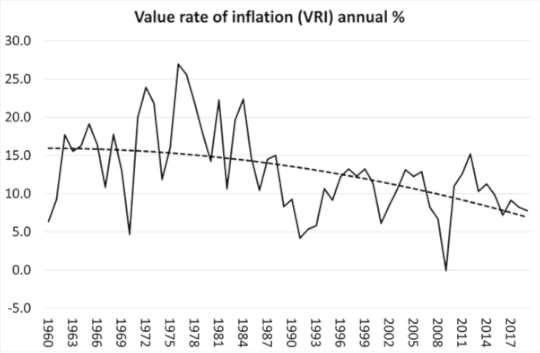

Another economics post that interested blog readers was on a Marxist theory of inflation. Marx never developed a comprehensive theory of inflation, but now Italian Marxist economist, Guglielmo Carchedi has come up with one. He argues that inflation rates depend on the generation of new value created in production. New value commands the demand or purchasing power over the supply of commodities. New value is divided by the class struggle into wages and profits. Wages buy consumer goods and profits buy capital or investment goods.

Total value will decline relatively to use value production and new value will decline relatively to total value. So there is an underlying deflationary or disinflationary pressure on the prices of commodities over the long term. But there are counteracting factors that can exert an upward pressure on prices over the long term; in particular, the intervention of the monetary authorities with their attempts to control the supply of money.

The combination of the combined purchasing power (CPP) of wages and profits and changes in money supply (M2) leads to a value rate of inflation (VRI), which is a powerful indicator of consumer price inflation. Does VRI suggest that current low inflation will continue, or will there be a spike in 2021? If wages and profits recover from their sharp falls in 2020 and money growth stays high, then the VRI theory suggests that annual inflation rates will accelerate next year.

My review of a People’s Guide to Capitalism by Hadas Thier also attracted a lot of interest. It is not easy explaining relatively complex ideas in a simple and clear manner. Ask any teacher. It’s a skill lacking in many. Hadas succeeded with a straightforward and entertaining explanation of all Marx’s basic theoretical insights into the nature and development of capitalism.

Another well-read post was not on Marxist economics but on Modern Monetary Theory (MMT). In a new book The Deficit Myth, leading MMT proponent, Stephanie Kelton argued the case for MMT as the best way to understand macro-economics and to realise that governments can run large budget deficits because they are the issuers and controllers of their national currencies. In this post, I argued that it may be a myth that governments cannot run deficits and need to ‘balance the books’. But it is a delusion to reckon that the crisis-prone nature of capitalist production can be ‘managed’ by means of ‘money artistry’, that is, by the manipulation of money, credit and government deficits. That’s because the structural causes of the crises and under-capacity lie not in the financial or monetary sector or the fiscal sector, but in the system of globalized capitalist production.

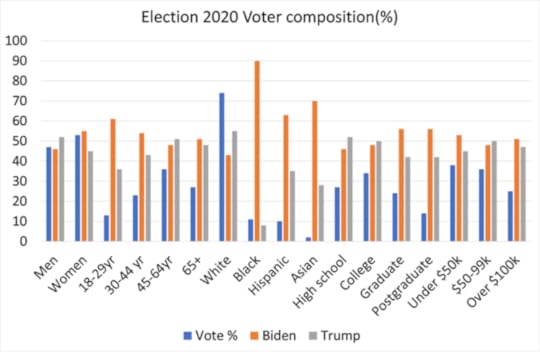

Finally, there was the US presidential election and the defeat of Donald Trump. My post on the election results was well up the top ten list, as this was the most important event of the year in capitalist politics.

My analysis found that there was a very high voter turnout in comparison with other post-1945 elections, but non-voters still took the largest share of those eligible to vote beating both Biden and Trump. White male working class voters went for Trump by over two to one, but the working class as a whole showed a small majority (2.5%) for Biden because younger Americans voted for Biden sufficiently to overcome Trump majorities among older voters; working class women and ethnic minorities voted for him in sufficient numbers to overcome the votes of white males, small town business people and rural areas. They voted to get rid of Trump: but they may not expect much from Biden and they will be right.

December 20, 2020

Books in the year of the COVID

Every year, I do a post on books that I have reviewed during the last 12 months. What’s a bit surprising in this year of the COVID is that I did not review any books specifically on the pandemic. Even the excellent book by John Bellamy Foster, The Return of Nature: Socialism and Ecology, which won this year’s Deutscher Memorial Prize, did not cover the impact of the coronavirus.

That was not its purpose, of course. Instead, Foster aims to show the close connection between socialism and ecology and, in particular, how Marx and Engels were always sensitive to the destructive impact of capitalism on nature as well as on labour (and it would appear in response, ‘nature’s revenge’, as Engels put it).

So what did I review? Let me start with what I consider was the best book of the year. This year it is a dead heat between two, in my view. The first is Henryk Grossman, Capitalism’s contradictions: studies in economic theory before and after Marx, edited by Rick Kuhn and published by Haymarket Books. Kuhn brings together essays and articles by Grossman that include an analysis of the economic theories of the Swiss political economist Simonde de Sismonde, who exercised a powerful influence on the early socialists who preceded Marx. And there is a critical essay by Grossman on all the various ideas and theories presented by Marx’s epigones from the 1880s onwards.

Grossman, in my view, made major contributions in explaining and developing Marx’s theory of value and crises under capitalism. He put value theory and Marx’s laws of accumulation and profitability at the centre of the cause of recurrent and regular crises under capitalism. He emphasised that the production of value is the driving force behind the contradictions in capitalism, not its circulation or distribution, even though these are an integral part of the circuit of capital, or value in motion. This issue of the role of production retains even more relevance in debates on the relevant laws of motion of capitalism today, given the development of ‘financialisation’ and the apparent slumber of industrial proletariat.

While the Grossman book gives the reader a deeper understanding of Marxist political economy, equally great for me this year was the excellent attempt to introduce Marx’s economic analysis in a popular way by Hadas Thier in her People’s Guide to Capitalism, also published by Haymarket Books.

Thier provides a clear, straightforward and entertaining explanation of all Marx’s basic theoretical insights into the nature and development of capitalism. And she uses modern examples that help the reader to understand why Marxist political economy is so clinical in its analysis of the reality of modern capitalist economies. The book can be regularly turned to in order to understand the waste, destruction and misery caused by the modern capitalist system of exploitation.

There are three other books with a Marxist perspective that I reviewed in 2020. The concept of ‘monopoly’ is often talked about in political economy as a relevant category for modern capitalism. We don’t usually recognise ‘monopsony capitalism’. But we should. This is where Ashok Kumar’s book, Monopsony Capitalism Power and Production in the Twilight of the Sweatshop Age fills a gap.

Kumar argues the monopsony power of the multi-national retailers in the ‘global north’ is now increasingly being challenged by oligopolistic suppliers in the ‘global south’, driven by their workforces to demand better prices and terms. This is altering the balance of economic power. Suppliers in the global south are gaining strength against monopsony buyers in the north. Kumar suggests that this could mean the end of the ‘sweatshop age’, although “that may ultimately depend on the self-organization and demands of the working people.”

Marx describes towards the end of Capital,“If money comes into the world with a congenital blood-stain on one cheek,” then “capital comes dripping from head to toe, from every pore, with blood and dirt.” Blood and Money is the theme of a new book by David McNally, the Marxist Professor of History at the University of Houston.

Blood and Money tells the story of money (the medium of capitalist exchange) as a history of violence and human bondage. McNally reckons money’s emergence and its transformation are intimately connected to the buying and selling of slaves and the waging of war. McNally’s argument has the ring of historic truth, but in my view, the emergence of money must still be seen as the product of exchange, not war or slavery. Indeed, modern capitalism (now without slavery, mostly) is even more exploitive of human labour power and bodies.

Back in Europe, in his new book, Sellouts in the Room, Eric Toussaint reviewed the events of the Greek debt crisis from 2012-15. At the beginning of 2015, the Greek people elected the left-wing Syriza party to power. Syriza pledged to resist austerity measures. The new leftist prime minister Tsipras appointed the already well-known economist Yanis Varoufakis as finance minister to negotiate a deal with the Troika. In the summer of 2015, the Greek people voted 60% to reject the Troika plan. But immediately after the vote, Tsipras caved into the Troika and agreed to their demands. Varoufakis resigned as finance minister and later wrote an account of his negotiations with the Troika, called Adults in the Room.

Toussaint was also in Greece at the time coordinating the work of a debt audit committee set up by the president of the Hellenic Parliament in 2015 to look at the nature of the debt that the Greeks owed to the likes of European banks, hedge funds and other governments. In his book, Toussaint offers an alternative view of those events from that recounted by Varoufakis. I have written a foreword to the English version. It amounts to a devastating critique of the Syriza government and of Varoufakis’ strategy and tactics during 2015. It’s a painful but necessary read.

Books with a Marxist perspective, of course, received much less acclaim and publicity than those from a Keynesian or post-Keynesian bent. This year, the most popular among radical circles in America was The Deficit Myth by Stephanie Kelton, former adviser to leftist Bernie Sanders and the most prominent promoter of Modern Monetary Theory (MMT). In her book, Kelton says that the argument of the ‘Austerians’ that governments must ‘balance their books’ is a myth because the national governments control the unit of national currency, so the state can just digitally ‘print’ the money it needs to spend. Indeed, that is what is happening right now during the COVID-19 pandemic, the argument goes.

On my blog and elsewhere, I have analysed critically the arguments of MMT. MMT has no concept of the law of value in capitalist economies, namely that production is for profit not social need; production is for exchange value, not use value; based on the exploitation in production, not on the creation of money for taxation. Profit does not touch the sides of MMT. And here the real issue is exposed. How does a capitalist economy expand capacity, investment and production? Why are there regular and recurring slumps in capitalist economies?

These questions are not dealt with or answered by MMT. It may be a myth that governments cannot run deficits and need to ‘balance the books’. But it is also an illusion to reckon that the crisis-prone nature of capitalist production can be ‘managed’ by means of ‘money artistry’, that is, by the manipulation of money, credit and government deficits. That’s because the structural causes of capitalist crises lie not in the monetary sector or the fiscal sector, but in the system of globalized capitalist production.

The other Keynesian book that received wide acclaim in 2020 was Trade wars are class wars by Matthew Klein and Michael Pettis. Klein and Pettis argue that the origin of the trade war between the US and China is rising inequality which has weakened aggregate demand; and a global ‘savings glut’ generated by countries like Germany and China. This has created huge global imbalances in demand and supply that threaten economic crises, increased protectionist rivalry and international peace.

This is a straightforward underconsumption theory of crises, much cruder than even Keynes. Consumption is not the only category of ‘aggregate demand’; there is also investment demand by capitalists. There has been an investment dearth not a savings glut, caused by declining profitability of capital in the major capitalist economies. The ‘class war’ that Klein and Pettis argue is the cause of trade wars should be related to the exploitation of labour by capital for higher profitability, not a lack of domestic consumption caused by low wages.

For Klein and Pettis, their ‘class war’ is between ‘bankers’ and ‘households’, not capital and labour. And the coming imperialist trade wars are between ‘excess savers’ (China and Germany) and excess consumers (US and UK), not between rival imperialist powers over the share of profits extracted from labour globally. Indeed, Klein and Pettis end up positioning US imperialism as a ‘victim’ of Asian and German economic policy!

We get a similar approach to Klein and Pettis in a book by Michael Howell, called Capital Wars. But Howell sees that the battle between the US and China taking place on the financial plane; not so much through trade or technology, but through financial flows and the control of international currencies. There is clearly some truth in this. If China were able to offer a strong and liquid currency to replace the dollar, US imperialism would be in serious trouble. But a strong currency cannot be ‘created’ by financial markets; it comes from the relative strength of the productivity of labour and value creation in an economy. That is where the economic war is centred; with trade, technology and finance being the battlegrounds. But value decides, not credit.

During the COVID summer, there were a bout of books professing to offer us something new to say on economics and capitalism. Angryonomics by Keynesians, Eric Lonergan and Mark Blyth, was a best seller. It explored the rising tide of anger against economics and economic policy exhibited by the populace. Blyth and Lonergan reckon some of this anger is justified (say the protest in Beirut against the political elite), but some is irrational (like intensified racism or Brexit). So ‘populism’ can be a force for the ‘better’ or for reaction.

What to do? Lonergan and Blyth reckon governments should borrow more and then invest through state wealth funds to boost education and health, so sadly neglected by governments before the COVID. But there is no need to break up the tech giants or take them over – just tax them a little. It’s a feeble answer.

This idea of saving capitalism from itself without hurting it too much also emerges from another book, The Economics of Belonging, by Martin Sandbu, the economics commentator for the Financial Times. Again, the context for Sandbu is the ‘rise of populism’ as the disenfranchised threaten the existing social order.

To save ‘liberal capitalism’, Sandbu proposes a plan to spend more on education and combine it with active labour market policies, a high minimum wage and limits on top pay. Instead of a radical restructuring of ownership and control to invest in basic public services, Sandbu offers us employee representation on company boards or universal basic income for people, working or not.

Saving capitalism from its own contradictions was, of course, the objective of John Maynard Keynes. In a new biographical history, The Price of Peace, Zachary Carter argues for a return to Keynes to solve the challenges of the 21st century. The question not answered is why Keynesian policies failed in the 20th century.

All these authors aim to save capitalism from itself with various policies, all of which are designed to make capitalism work without threatening anything in its fundamental structure. Marxian political economy argues that this approach cannot succeed. So I would return to Marx and Engels.

And 2020 was not just the year of the COVID, it was also the 200th anniversary of the birth of Friedrich Engels. This year, I published a short book that outlined his contribution to Marxist economics, which has been sadly neglected. Engels was first with a Marxist critique of mainstream economics; the inventor of important Marxist categories of economic analysis like the ‘reserve army of labour’; turnover of capital; ‘fictitious capital’ and the concentration and centralisation of capital. And in his later years, he forecast the rise of imperialism, the first world war and the emergence of proletarian revolutions.

Finally, apart from these reads, don’t miss my presentations and interviews with other Marxist economists over last year, available on my You Tube channel, which was only launched this year, just before the COVID broke. Plenty of stuff on that there.

December 16, 2020

Beethoven: revolutionary times

It is the 250th anniversary of the birth of Ludwig Beethoven, who was born either on 16 or 17 December 1770; nobody was quite sure, including Beethoven himself. Beethoven is considered the most musically revolutionary of ‘classical’ composers. And in my view, that was no accident of history because Beethoven was a man of his time.

He was born at the time of what has been called the ‘enlightenment’, when European thought broke from a subservience to religion and monarchy and raised the banner of free thinking, science and democracy – and there were the first glimmerings of a new economic order based of ‘free trade and competition’. Adam Smith published his seminal work, The Wealth of Nations, when Beethoven was six years old. And the American war of independence took place, in which the formerly British settlers broke from the British monarchy, with the financial and military support of France to establish a republic with voting rights, exercised again this year.

In my view, Beethoven’s musical journey swung with the ups and downs of this revolutionary time that continued throughout his life, but particularly with the ebb and flow of the French revolution that ended monarchy, feudal rights and proclaimed equality, freedom and fraternity for all (men). As a teenager, Beethoven, like many other young ‘middling’ people in Europe, was a strong supporter of the revolution from the beginning.

The son of a musician from a family of Flemish origin, his father, Johann, was employed by the court of the Archbishop-Elector of Bonn, Germany. He gave his first public performance aged seven and moved to Vienna in 1792 to study with Joseph Haydn, who, with Mozart (who had died the previous year aged 35), had shaped the city’s musical tradition.

Vienna was under the rule of the Hapsburg absolutist empire. But Beethoven was wrapped up in Napoleonic ideas of freedom. He became a staunch republican and in both his letters and conversation spoke frequently of the importance of liberty. He did not care for royalty. To one of his earliest patrons, Prince Karl Lichnowsky, Beethoven wrote: “Prince, what you are, you are by accident of birth; what I am, I am of myself.” Austrian monarch, Franz II allegedly refused to have anything to do with Beethoven, on the basis that there was “something revolutionary in the music”. And what friendship the composer had with great German writer and poet, Goethe, was ended abruptly in 1812 when, walking together in the park, they came across the Austrian Empress. Goethe bowed subserviently; Beethoven disdainfully turned his back.

This revolutionary spirit inhabits much of his work. He propelled music into this new age. Bringing together the poetic power of the German literary scene and the French songs of revolution, he completely changed what music could be. “Beethoven is the friend and contemporary of the French Revolution, and he remained faithful to it even when, during the Jacobin dictatorship, humanitarians with weak nerves of the Schiller type turned from it, preferring to destroy tyrants on the theatrical stage with the help of cardboard swords. Beethoven, that plebeian genius, who proudly turned his back on emperors, princes and magnates – that is the Beethoven we love for his unassailable optimism, his virile sadness, for the inspired pathos of his struggle, and for his iron will which enabled him to seize destiny by the throat.” (Igor Stravinsky). Beethoven changed the way music was composed and listened to. His music does not calm, but shocks and disturbs.

I think we can divide up Beethoven’s musical work into four periods that match the economic and social ups and downs of his lifetime. His was the age of three great bourgeois revolutions: the industrial in England; the political in France; and the philosophical in Germany. The first period of his life as young boy and then as a young adult was during a revolutionary upswing in Europe; but also a new economic upswing in capitalist development, leading to the apex of the French revolution with the ascendancy of the radical Jacobin administration in 1792 when Beethoven was 22 years old.

The second period from 1792 to 1815 was really one of setback for the revolution in France as the Jacobins were overthrown and the hero of the military defence of the revolutionary government, Napoleon Bonaparte, made himself dictator. But that also meant that Napoleon’s armies took the ideas and laws of the French revolution across Europe, overthrowing the reactionary semi-feudal absolute monarchies of Austria, Spain, Italy and Prussia. His victories made him an idol in Beethoven’s eyes.

It was in this period that a maturing Beethoven composed some of his greatest works. His magnificent 5th symphony is brimming with references to the music of the revolution. In its composition, Beethoven remarks that his symphony expresses the words written about murdered French revolutionary leader Jean-Paul Marat “We swear, sword in hand, to die for the republic and for human rights”. His only opera, Fidelio, tells of a lone woman freeing her husband, a political prisoner, from a Spanish jail (the setting having been moved from France for political reasons, reasons which included his hatred of the regime in Spain).

A revolutionary spirit moves every bar of the Fifth. The celebrated opening bars of this work (listen) are perhaps the most striking opening of any musical work in history. By coincidence, they are the musical equivalent of the Morse code signal for “V” meaning victory, used to rally the French people to fight the German occupiers in WW2. “This is not music; it is political agitation. It is saying to us: the world we have is no good. Let us change it! Let’s go!” (Nikolaus Harnancourt, conductor).

Another famous conductor and musicologist, John Elliot Gardener, has discovered that all the main themes in Beethoven’s symphonies are based on French revolutionary songs. The “cry of alarm”, “Marchons, marchons” from “La Marseillaise”, the rallying call of the French Revolution, is echoed in the opening chords of the “Eroica” symphony. The Fifth Piano Concerto (“Emperor”) exudes “military energy”. The trumpet passages in Fidelio echo those in Handel’s Messiah that occur under the vocal line “the trumpet shall sound… and we shall all be changed”.

But this great period of musical energy was increasingly marred by Beethoven’s terrible and tortuous illness, as he gradually went deaf, possibly with a type of meningitis – which affected his hearing. This started when he was 28 years old and at the peak of his fame. Although he did not become completely deaf until his last years, the awareness of his deteriorating condition made him unpredictable, depressed and even suicidal.

There was also a deterioration in Europe’s economy from 1805, beginning with the blockade of France’s conquests by British naval power after the victory of its navy at Trafalgar, creating increasing shortages of food and staples. And Beethoven was also depressed with political events in this period. He had dedicated his 3rd symphony to Napoleon. But by 1802 Beethoven’s opinion of Napoleon was beginning to change. In a letter to a friend written in that year, he wrote indignantly: “everything is trying to slide back into the old rut after Napoleon signed the Concordat with the Pope.” Beethoven’s admiration finally turned to resentment when Napoleon declared himself Emperor in 1804. When Beethoven received news of these events, he angrily crossed out his dedication to Napoleon in the score of his new symphony. The manuscript still exists and we can see that he attacked the page with such violence that it has a hole torn through it. He then dedicated the symphony to an anonymous hero of the revolution: the Eroica symphony it became.

The third period of Beethoven’s musical life matched a period of deep reaction and a shocking downturn in Europe’s economies. With Napoleon’s defeat in 1815 with the old monarchies restored in Europe, Beethoven was in despair, composing little. Everywhere progressive thought was in retreat: the great romantic poets of victorious England, Shelley and Byron, were forced into exile. Mary Shelley wrote Frankenstein, a novel that despairs at both bigoted superstition and racism as well as antagonism towards the uncontrolled scientific industrialism of the rising capitalist economy. This was the end of romanticism and revolution and now was the time for such as David Ricardo, more or less the same age as Beethoven, who in 1817 wrote his Principles of Political Economy and Taxation, the definitive work of bourgeois economics, a paeon to capitalism.

The years 1816-19 were terrible ones for the people of Europe, not dissimilar to this year of the COVID in 2020. The European economy fell into a permanent winter, both literally and economically. 1816 is known as the ‘Year Without a Summer’ (also the Poverty Year) because of severe climate abnormalities that caused temperatures in Europe to drop to the coldest on record. There were failed harvests. This resulted in major food shortages. In Germany, where the crisis was severe. Food prices rose sharply throughout Europe. Though riots were common during times of hunger, the food riots of 1816 and 1817 saw the highest levels of civic violence since the French Revolution. It was the worst famine of 19th-century mainland Europe.

Suffocating in the reactionary atmosphere of Vienna, and despairing of any change for the better, Beethoven wrote: “As long as the Austrians have their brown beer and little sausages, they will never revolt.”

However, the final decade of Beethoven’s life from the 1820s saw a revival in the European economy as the capitalist mode of production spread and industry began to replace a mostly rural Germany and Austria. Indeed, there was the first capitalist economic slump in 1825; and later, the first signs of proletarian struggle which eventually led to the overthrow of the restored Bourbon monarchy in France in 1830 and the 1832 Reform Act in England, allowing better-off adult males the right for the vote for the first time.

And in 1824 Beethoven delivered his final masterpiece before his death in 1827. Beethoven had long been considering the idea of a choral symphony and took as his text the German poet Schiller’s Ode to Joy, which he had known since 1792 and was originally published in 1785 taken from a drinking song for German republicans. In fact, Schiller had originally considered calling the song an Ode to Freedom (Freiheit), but because of the enormous pressure of reactionary forces, he changed the word to Joy (Freude). Those words of Schiller became the centrepiece of the 9th symphony (which is used by the European Union as its anthem now). https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Jo_-KoBiBG0

The ninth symphony has been called The Marseillaise of Humanity. Beethoven revives the sound of revolutionary optimism. It is the voice of a man who refuses to admit defeat, whose head remains unbowed in adversity.

December 14, 2020

COVID-19: the winter wave and the death toll

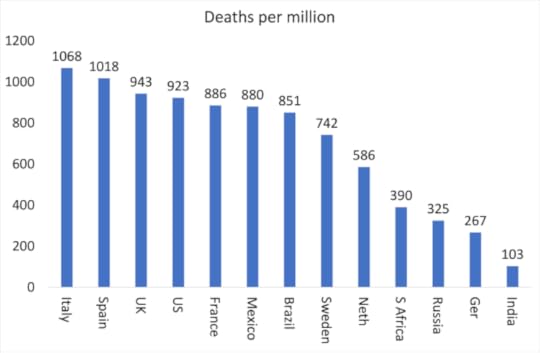

The winter wave of COVID-19 cases continues to rage in Europe, North America and even Latin America and Asia. So, as the vaccines get rolled out across the world to varying degrees of rapidity and volume, let’s measure the damage done in deaths from COVID-19 as we approach the end of 2020.

Which countries have been hit hardest? Using the Worldometer coronavirus database, I’ve selected some of the major countries globally in Chart 1 (measured as deaths per million of population). It’s the large European countries and the US that lead the way on this measure, followed closely by Brazil and Mexico, two Latin American countries that have made little effort to contain the pandemic or provide any robust health support. The countries that have done that, like Germany, have a much lower death rate. And countries like South Africa and India, with relatively young populations, also have lower death rates.

Chart 1. Deaths per million

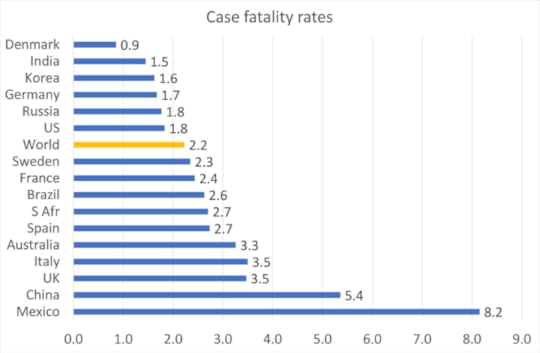

The second measure is the case fatality rate (CFR) ie the number of deaths per COVID-19 cases reported to the authorities (Chart 2). Mexico shows a shocking death rate of over 8% of cases, most probably because of the failure to test and trace and the weakness of its health system. Note that China’s CFR is high too, but that was all recorded in the first month of pandemic in Wuhan. The major European countries are well above the world average CFR of 2.2% after ten months. The US is just below the world average and well-organised countries like Germany, Korea and Denmark are even further down. India’s young population may explain its low CFR.

Chart 2. Case fatality rates (%)

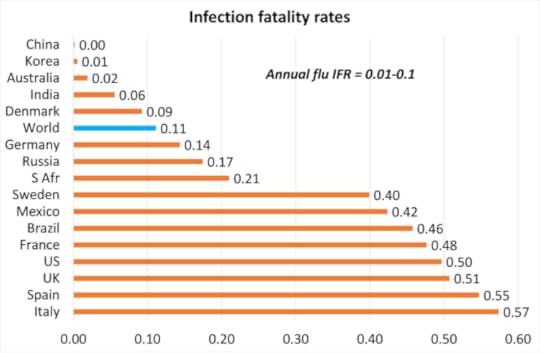

Finally, there is the infection fatality rate (IFR). This measures the death rate from all those infected. The World Health Organisation estimates that there are about 20 times more infections than cases reported, including all those who were asymptomatic. Using that estimate, I find that around 18% or so globally have so far been infected, well below the so-called ‘herd immunity’ ratio of about 50-60% minimum. So those governments that opted for a strategy of lite-lockdowns, hoping for herd immunity, like Sweden, have been proved wrong. Indeed, Sweden’s IFR is pretty close to that of hard-hit Mexico (Chart 3).

Chart 3. Infection fatality rates (%)

The IFRs in most of the major countries are about 0.4-0.6%, more or less as forecast by various sample studies. And my estimate of 18% infected globally may well be too high. If I lowered the global infection rate to 15%, then the IFRs would be in the 0.6-0.7% range. That compares with the annual flu IFR of less than 0.1%. So for these hard-hit countries, COVID-19 is at least five times more deadly than annual flu. And, of course, we are now finding out that there is often long-lasting damage to human organs from COVID, unlike flu.

The world IFR is only 0.11%, or close to the maximum annual flu IFR, on my estimates. But that world IFR average is skewed lower by countries with large youthful populations like India or large populations like China where infections have been drastically contained. In most countries, infections are still spreading and that means many more deaths. Roll on the vaccines.

December 12, 2020

The Friedman doctrine in the 21st century

The Stigler Center at the Booth Business School of the University of Chicago has just published an e-book commemorating Milton Friedman’s pronouncement on the valuable and virtuous role of modern capitalist corporations. Named after leading neoclassical economist George Stigler, the Stigler Center wanted to honour the work of Milton Friedman in justifying capitalist corporations as a force for good.

For those who don’t know, Milton Friedman was the leading economist of the ‘Chicago School’ in the post-war period and the renowned exponent of ‘monetarism’ ie that inflation of goods and services prices is caused by changes in the quantity of money circulating in an economy. Friedman was notorious for his support of ‘free markets’, small government and dictatorships (he gave advice to the Pinochet dictatorship in Chile in the 1970s). See my 2006 review of Friedman’s work in my book, The Great Recession, p119.

What interested the Stigler Center was Friedman’s view on corporations, the form that modern capitalist companies have taken since the late 19th century, replacing most firms directly owned by their managers (family owned or partnerships). The ‘Friedman doctrine’, as it has been called, says that a firm’s sole responsibility is to its shareholders. And as such, the goal of the firm is to maximize returns to shareholders. Corporations are there to maximise profits and that should be their sole aim, without any distractions of ‘social responsibility’ or other ‘external’ concerns. Indeed, if firms or corporations do just that, in the world of free markets, gains to the whole community will follow: “there is one and only one social responsibility of business—to use its resources and engage in activities designed to increase its profits so long as it stays within the rules of the game, which is to say, engages in open and free competition without deception or fraud.” (Friedman).

The Stigler book aims to defend and promote Friedman’s characterisation of the aim of capitalist corporations. But it also contains essays by those who disagree. I won’t discuss the details of the essays defending Friedman’s doctrine; I prefer to look at the arguments of those who disagree. But let’s start by saying that Friedman is clearly right: the aim of capitalist firms or corporations is to maximise profits for their owners, whether directly owned or through shareholders. And he is right to say that any other motives or aims adopted can only detract from achieving that profit.

Of course, where Friedman is wrong is to assume that capitalism’s drive for profits in a ‘free competitive market’ will benefit all, not just capitalist owners, but workers and the planet. It’s nonsense for defenders of Friedman in the Stigler book, like Kaplan, to conclude that “Friedman was and is right. A world in which businesses maximize shareholder value has been immensely productive and successful over the last 50 years. Accordingly, business should continue to maximize shareholder value as long as it stays within the rules of the game. Any other goal incentivizes disorder, disinvestment, government interference and, ultimately, decline.”

But the critics of Friedman’s doctrine from the Keynesian/heterodox economists fall into a trap. Their line, as argued by Martin Wolf and Luigi Zingales, is that Friedman’s doctrine fails because there are no free competitive markets in modern capitalism. Corporations have become so big that they have become ‘price makers’, not ‘price takers.’ As Wolf puts it, the big corporations do not keep to the rules and regulations for a ‘level playing field’ in markets: “corporations are not rule-takers but rather rule-makers. They play games whose rules they have a big role in creating, via politics.”

The implication of this critique of the Friedman doctrine is that if corporations kept to “the rules”, then capitalism would work for all. In other words, there is nothing wrong with private corporations producing for profit and exploiting their workers to do so. The problem is that they have become too big for their boots. We need to regulate them so that, in making their profits, they all compete fairly with each other and also take into account the “externalities”; ie. the social consequences of their activities.

This critique assumes that competitive capitalism is a ‘good thing’ and works. But would competitive capitalism, if it existed or were imposed by governmental rules, deliver a ‘fair and just society’? In the days when ‘competitive capitalism’ supposedly existed, namely in the early 19th century, Friedrich Engels pointed out that free trade and competition in no way provided an equitable and harmonious development of production for the benefit of all. As Engels argued, while the classical economists offer competition and free trade against the evils of monopoly, they fail to recognise the biggest monopoly of all: the ownership of private property for a few and lack of it for the rest. (See my book, Engels 200). Competitive capitalism did not avoid increased inequality, damage to the environment, extreme exploitation of its workers and regular and recurring crises in investment and production. That was precisely because the capitalist mode of production is for profit (as Friedman says) – and from that, all else flows.

Yes, said, Engels, “competition is based on self-interest and self-interest breeds monopoly. In short competition passes over into monopoly.” But that does not mean monopoly is the evil that must be banished and that a return to free markets and competition (within the rules set) would work. This is the trap that some left economists fall into when they talk of the evils of ‘state monopoly capitalism’. It is not monopolies as such, or their ‘capture’ of the state, that is at the heart of the argument against Friedman’s doctrine. It is capitalism as such: the private ownership of the means of production for profit. This is the strongest critique of Friedman’s justification of the corporation.

Instead, the likes of Martin Wolf or Joseph Stiglitz just want to correct the ‘rules of the game’. Wolf wants what he calls a good game’ where “companies would not promote junk science on climate and the environment; it is one in which companies would not kill hundreds of thousands of people, by promoting addiction to opiates; it is one in which companies would not lobby for tax systems that let them park vast proportions of their profits in tax havens; it is one in which the financial sector would not lobby for the inadequate capitalisation that causes huge crises; it is one in which copyright would not be extended and extended and extended; it is one in which companies would not seek to neuter an effective competition policy; it is one in which companies would not lobby hard against efforts to limit the adverse social consequences of precarious work; and so on and so forth.” For Wolf, the task is “how to create good rules of the game on competition, labour, the environment, taxation and so forth.”

This is not only a wrong analysis of modern capitalism; it is utopian in the extreme. How can any of the above inequities described by Wolf be ended while preserving capitalism and the corporations? We only have to consider the never-ending story of banking folk and their connivance with the corporations to hide their profits from national governments. According to the Tax Justice Network, multinational firms shifted more than $700billion in profits to tax havens in 2017 and this shifting reduced global corporate tax receipts for national governments by close to 10%.

Carbon-emitting fossil fuel corporations have shifted billions of profits into various tax havens. In 2018 and 2019, Shell earned more than $2.7 billion – about 7% of its total income in those years – tax-free by reporting profits in companies located in Bermuda and the Bahamas that employed just 39 people and generated the bulk of their revenue from other Shell entities. If this oil-and-gas major had booked the profits through its headquarters in the Netherlands, it could have faced a tax bill of about $700 million based on the Dutch corporate tax rate of 25%.

And then there are the FAANGS, the big tech corporations which have amassed huge profits during the COVID-19 pandemic while many small companies go to the wall. They dominate software and distribution technology through intellectual property copyrights and suck up any competition. Governments around the world are now considering how to regulate these giants and bring them under the “rules of the game”. The talk is of breaking up these ‘monopolies’ into smaller competitive units. I’m sure that Friedman would have approved of this solution as part of his ‘doctrine’.

But would it solve anything really? More than a century ago, US antitrust regulators ordered the break-up of Standard Oil. The company had grown into an industrial empire that produced more than 90 per cent of America’s refined oil output. The company was broken up into 34 ‘smaller’ companies. They still exist today. They are named Exxon Mobil, BP and Chevron. Do Wolf, Stiglitz and opponents of ‘monopoly capitalism’ really reckon that the ‘Standard Oil’ solution has ended the ‘irregularities’ of the oil corporations, improved their ‘social responsibilities’ and environmental safeguards globally? Do they really think ‘stakeholder capitalism’ can replace the corporation and do the trick? Regulation and the restoration of competition won’t work because all it means is that Friedman’s doctrine continues to operate.

December 6, 2020

The top 1% of households own 43% of global wealth, 10% owns 81%, while the bottom 50% have just 1%.

The top 1% of households globally own 43% of all personal wealth while the bottom 50% have only 1%. The 1% are all millionaires in net wealth (after debt) and there are 52m of them. Within this 1%, there are 175,000 ultra-wealthy people with over $50m in net wealth – that’s a miniscule number of people (less than 0.1%) owning 25% of the world’s wealth!

This information comes from the 2020 Credit Suisse Global Wealth report which has just been released. The report remains the most comprehensive and explanatory analysis of global wealth (not income) and of the inequality of personal wealth. Every year the CS global wealth report analyses the household wealth of 5.2 billion people across the globe. Household wealth is made up of the financial assets (stocks, bonds, cash, pension funds) and property (houses etc) owned. And the report measures this, net of debt. The report’s authors are James Davies, Rodrigo Lluberas and Anthony Shorrocks. Professor Anthony Shorrocks was my university flatmate, where we both graduated in economics (although he has the much better mathematical skills!).

According to the 2020 report, total global household wealth rose by USD36.3 trillion during 2019. But the COVD-19 pandemic cut that 2019 increase by nearly half (USD17.5 trillion) between January and March 2020. However, because stock-markets and property prices then rebounded, thanks to government and central bank credit injections, the Credit Suisse researchers reckon that total household wealth was still slightly up by mid-2020 compared to the level at the end of last year, although wealth per adult was slightly down.

By mid-2020 global household wealth was USD 1 trillion above the January level, a rise of 0.25%. As this is less than the rise in adult numbers over the same period, average global wealth fell by 0.4% to USD 76,984. In comparison to what would have been expected before the COVID-19 outbreak, global wealth fell by USD 7.2 trillion, or USD 1,391 per adult worldwide.

The most adversely affected region was Latin America, where currency devaluations reinforced reductions in dollar GDPs, resulting in a 12.8% reduction in total wealth in dollar terms. The pandemic also eradicated the expected growth in North America and caused losses in every other region, except China and India. Among the major global economies, the United Kingdom has seen the biggest relative erosion of wealth.

Most shocking is the still huge inequality of household wealth globally. As shown by the wealth pyramid graphic below, inequality remains stark, both geographically between the ‘rich north’ and ‘poor south’; and between households within countries.

At the end of 2019, North America and Europe accounted for 55% of total global wealth, with only 17% of the world adult population. In contrast, the population share was three times larger than the wealth share in Latin America, four times the wealth share in India, and nearly ten times the wealth share in Africa.

Wealth differences within countries are even more pronounced. The top 1% of wealth holders in a country typically own 25%–40% of all wealth, and the top 10% usually account for 55%–75%. At the end of 2019, millionaires around the world – which number exactly 1% of the adult population – accounted for 43.4% of global net worth. In contrast, 54% of adults with wealth below USD 10,000 (ie pretty much nothing) together mustered less than 2% of global wealth.

The researchers reckon that the worldwide impact on wealth distribution within countries has been remarkably small given the substantial pandemic-related GDP losses. Indeed, there is no firm evidence that the pandemic has systematically favoured higher-wealth over lower-wealth groups or vice versa. In 2019, the number of millionaires worldwide soared to 51.9 million, but has changed very little overall during the first half of 2020.

At the apex of the wealth pyramid, the report estimates that at the start of this year there were 175,690 ultra-high net worth (UHNW) adults in the world with net worth exceeding USD 50 million. The total number of UHNW adults rose by 16,760 (11%) in 2019, but 120 members were lost during the first half of 2020, leaving a net gain of 16,640 in UHNW membership since the start of 2019.

During the first half of 2020, the number of millionaires shrank by 56,000 overall, just 1% of the 5.7 million added in 2019. Membership has expanded in some countries and some have lost significant numbers. The United Kingdom (down 241,000), Brazil (down 116,000), Australia (down 83,000) and Canada (down 72,000) all shed more millionaires than the world as a whole.

It seems that wealth inequality declined within most countries during the early 2000s. The fall in inequality within countries was reinforced by a drop in “between-country” inequality, fuelled by rapid rises in average wealth in emerging markets. The trend became mixed after the financial crisis of 2008, when financial assets grew speedily in response to quantitative easing and artificially low interest rates. These factors raised the share of the top 1% of wealth holders, but inequality continued to decline for those below the upper tail. Today, the bottom 90% accounts for 19% of global wealth, compared to 11% in the year 2000. In other words, there was a concentration of wealth towards the top 1% (and even more to 0.1%), but with some dispersion among the remaining 99%.

The researchers conclude that the small decline in wealth inequality in the world as a whole “reflects narrowing wealth differentials between countries as emerging economies, particularly China and India, have grown at above-average rates. This is the main reason why global wealth inequality fell in the early years of the century, and while it edged upward during 2007–16, we believe that global wealth inequality re-entered a downward phase after 2016.”

In short, what the report shows is billions of people have no wealth at all after debts and that the distribution of global personal wealth can be described as a few Gulliver giants looking down on the mass of Lilliputians.

December 2, 2020

A credit crash ahead?

The pandemic global slump of 2020 is different from previous slumps in capitalism. The boom and slump cycle in capitalist production and investment is often triggered by a financial crash, either in the banking system (as in the Great Recession of 2008-9) or in the ‘fictitious capital’ world of stocks and bonds (as in 1929 or 2001). Of course, the underlying cause of regular and recurring slumps lies in the movements in the profitability of capital, as has been discussed ad nauseam in this blog. This is the ‘ultimate’ cause. But ‘proximate’ causes can differ. And they are not always ‘financial’ in origin. The first simultaneous international post-war global slump of 1974-5 was triggered by a sharp rise in oil prices following the Arab-Israeli war; and the double-dip recession of 1980-2 had similar origins. Again, the 1991-2 recession followed the ‘Gulf War’ of 1990.

The pandemic slump also has a different ‘proximate’ cause. In a sense, this unprecedented global slump, affecting 97% of the world’s nations, kicked off because of an ‘exogenous event’ – the spread of a deadly virus. But, as has been argued by ecologists and in this blog, the rapacious drive for profits by capitalist companies in fossil fuel exploration, timber logging, mining and urban expansion without regard for nature, created the conditions for the emergence of a succession of pathogens deadly to the human body to which it lacked immunity. In that sense, the slump was not ‘exogenous’.

But the ensuing slump in world production, trade, investment and employment did not start with a financial or stock market crash, which then led to a collapse in investment, production and employment. It was the opposite. There was a collapse in production and trade, forced or imposed by pandemic lockdowns, which then led to a huge fall in incomes, spending and trade. So the slump kicked off with an ‘exogenous shock’, then the lockdowns led to a ‘supply shock’ and then a ‘demand shock’.

But so far, there has not been a ‘financial shock’. On the contrary, the stock and bond markets of the major countries are at record highs. The reason is clear. The response of the key national monetary institutions and governments was to inject trillions of money/credit into their economies to bolster up the banks, major companies and smaller ones; as well as pay checks for millions of unemployed and/or laid off workers. The size of this ‘largesse’, financed by the ‘printing’ of money by central banks, is unprecedented in the history of modern capitalism.

This has meant, contrary to the situation at the start of the Great Recession, the banks and major financial institutions are not close to meltdown at all. Bank balance sheets are stronger than before the pandemic. Financial profits are up. Bank deposits have rocketed as central banks increase commercial bank reserves and companies and households hoard cash; given that investment has stopped and households are spending less.

According to the OECD, household savings rates have risen between 10-20% points during the pandemic. Household deposits at the banks have soared. Similarly, non-financial corporation cash holdings have increased as companies take out cheap or interest-free government-guaranteed loans, or larger companies issue yet more bonds, all encouraged and financed by government-sponsored programs. Taxes have also been deferred as companies go into lockdown or purdah, again building up yet more cash. Tax deferrals are equivalent to 13% of GDP in Italy and 5% of GDP in Japan, according to the OECD.

Indeed, the latest corporate profit figures (Q3 2020) in the US showed a sharp rise in profits, almost entirely due government loans and grants that have boosted cash flow along with a fall in sales and production taxes as companies stopped trading. Corporate profits increased $495 billion in the third quarter, in contrast to a decrease of $209 billion in the second quarter. The government statistical office explains “Corporate profits and proprietors’ income were in part bolstered by provisions from federal government pandemic response programs, such as the Paycheck Protection Program and tax credits for employee retention and paid sick leave, which provided financial support to businesses impacted by the pandemic in both the second and third quarters.” Around $1.5trn of US government grants and loans went into subsidising US companies during the pandemic. So corporate profits have been sustained by government intervention – at the cost of unprecedented levels of government budget deficits and rises in public sector debt.

The hope now is that as the vaccines are delivered and distributed during 2021 and the lockdowns are ended, the world economy will spring back and the build-up of household savings and corporate profits will be released, as ‘pent up’ demand flows back into the capitalist economy. Consumer spending will return, people will resume international travel and tourism and go to mass events; while companies will launch an investment binge.