S.D. Falchetti's Blog, page 3

August 29, 2021

Thoughts on Reminiscence

We’re in a strange pandemic timeframe where new movies are few and far between and those that are released may simultaneously go to screen and streaming services. I’m curious if, once we get over the pandemic hump, the watch-from-home options will continue (I suspect they will). This weekend, I found myself pleased to find a new sci-fi offering with A-list actors available on HBO Max.

Hugh Jackman in the sci-fi noir flick, Reminiscence

Reminiscence is set in a near-future where climate change has caused ocean levels to rise and made daytime temperatures unbearable. As a result, Miami has turned into a Venice-like Sunken Coast, with boats ferrying people between neon-lit skyscrapers. To avoid the heat, people are awake at night and sleep during the day. Many people want an escape from their dreary existence and Hugh Jackman’s character, Nick, offers them just that. He and Thandiwe Newton (Watts) have a very Minority-Reportish business that involves clients laying down in a water tank while holographic projectors visualize their favorite memories. Hugh Jackman acts as a hypnotist, verbally leading clients along a path to find their memory, while Thandie operates the equipment. They record the memories for legal (aka “plot”) reasons and store them in a bank vault. The plot kicks in when Rebecca Ferguson, who plays femme fatale Mae, shows up asking for help retrieving a specific memory. Hugh Jackman is captivated by Mae, falls for her, and makes it his personal mission to discover what plot she’s entwined.

Just about every review you’ll read on Reminiscence points out that it’s derivative of other well-known sci-fi movies, and I’ll follow suit. The water tank and hologram are very much Minority Report.

Hugh Jackman in the water tank in Reminiscence

Agatha in the water tank in Minority Report

Hugh Jackman peeps through Rebecca Ferguson’s memories in Reminiscence

Tom Cruise relives a memory from when times were better in Minority Report

The idea of having a recording of someone’s memory that the bad guys want is right out of Strange Days.

One of Strange Day’s memories, saved on Mini Disc. Well, it was 1999.

Hugh Jackman guiding people through their memories reminds me of Leonardo Dicaprio guiding people through their dreams in Inception.

Visually and thematically, Hugh Jackman and Rebecca Ferguson’s relationship is very much like Blade Runner’s Ford and Young, complete with foggy, atmospheric interior shots with gold light shining in through windows.

Blade Runner’s sci-fi noir atmosphere

Reminiscence’s sci-fi noir atmosphere

The visuals for Miami’s Sunken Coast are quite good, and I enjoyed the nighttime-only city on the water views. Some reviewers have compared it to Waterworld, but I don’t think that’s a fair comparison. I found the visualizations to be original and interesting, and one of the better components of the movie.

It’s also worth noting that Reminiscence is a bit of a Westworld reunion, with the director, Lisa Joy, and two actresses Thandiwe Newton and Angela Sarafyan.

Thandiwe Newton in Reminiscence

Angela Sarafyan in Westworld

So, what to make of Reminiscence? It’s a convoluted sci-fi noir film with a detective, femme fatale, alcoholic partner, crime bosses, and a dark neon future. Like a gumshoe in 40s detective fiction, Nick offers voice-overs throughout the story. These aren’t necessarily bad elements - to become a trope, something must be enjoyable enough that audiences keep demanding it - and the similarity to other movies isn’t much of a deal-breaker for me. Certain themes, such as being able to record people’s memories, appear again and again in sci-fi, and exploring them isn’t a bad thing - but it does help if you have an interesting spin so that you’re not simply making a collage of other movies.

The main detractors for me in Reminiscence were:

The plot is convoluted, in the way that detective novels tend to be. There are crime bosses, henchman, devious heirs, prosecutors all wanting something and at times it feels like Nick is on a side-quest, leaving the viewer wondering where the movie is going. It’s the type of plot you’ll need to Google afterwards to determine how everyone was related to the storyline.

The plot is that Nick is obsessed with Mae and makes it his mission to track her down. From a stakes standpoint, he really could walk away at any time, and the bad guys don’t really care about him or even know who he is.

The two main action scenes (a shoot out at a crime boss’s club and a fist fight in a water-damaged hotel) were silly. The first was cartoonish and the second seemed to be a checklist of action scene tropes (have the fist-fighters roll down the stairway together, etc).

On Rotten Tomatoes, Reminiscence scored a 37%. I don’t think it was that bad. I’d probably score it a low 3 out of 5. I didn’t mind watching it and it was nice to have a new sci-fi movie to binge on a Saturday night, but it was (ironically) forgettable. I think the directing and acting were good but the writing and dialogue needed work. But, if you have HBO Max and are looking for something to watch, I say give it a go. It’s not a “I want my two hours back” kind of a movie, it’s a “there are ways it could have been better” kind of flick.

August 21, 2021

Aviation Procedures in Microsoft Flight Simulator and X-Plane

If you enjoy aviation and haven’t stumbled upon my YouTube channel yet, be sure to check it out. Over the past two years I’ve made 108 videos of X-Plane and Microsoft Flight Simulator 2020 flights. It’s been a journey, and I’ve learned a lot about aviation procedures along the way. In particular, once I joined PIlotEdge, which offers by-the-book online air traffic controllers to interface with, I needed to learn real-life radio phraseology and VFR procedures. I remember when I first started being a bit baffled about how to fly in the pattern at an untowered airport. Later, learning how to talk with ATC to navigate out of a Class Charlie airport was a challenge. Even later, flying procedures like DME arcs was both fun and difficult. It always helped if I could find a YouTube video of someone doing the same thing, so I thought I’d list some of them from my channel if you’re looking to see how I tackled a particular procedure:

Class C Departure without Flight Following (Portland International)

VFR departures from a Class C airport will need to talk to Clearance Delivery, Ground, Tower, and Approach, and will receive a squawk code. You will also likely receive altitude and heading restrictions.

Class C Departure with Flight Following (John Wayne International)

VFR departures from a Class C without flight following will be told “frequency change approved, squawk VFR” upon departing the Approach ring, but if you have flight following you’ll keep your squawk code and be handed over to the next controller, who will give you traffic advisories as workload permits.

CTAF calls from Untowered airport to Untowered airport (PilotEdge CAT-01)

The Common Traffic Advisory Frequency (CTAF) is published for each untowered airport. Pilots should (but are not required) make calls on it to announce their intentions to other pilots.

Los Angeles Bravo Transition via the Coastal Route

The LAX Bravo is a complex airspace that has corridors carved out for VFR flights. Some allow you to fly simply making CTAF calls using Special Flight Rules. Others require precise flight paths and altitudes.

Basic IFR Flight

Instrument Flight Rules (IFR) rely on navigating with your plane’s instruments and ATC communication.

New York Bravo Hudson River Exclusion Special Flight Rules

Similar to Los Angeles, New York’s Bravo has areas carved out for VFR pilots. The Hudson River Exclusion is a scenic area with special flight rules.

NDB Approach with Procedure Turn

Non-directional beacons (NDB) are like homing signals for your aircraft. Some airports still have instrument approaches using them. Procedure turns are a series of maneuvers to precisely reverse your course.

Flying a TEC Route

Tower Enroute Control (TEC) Routes are pre-packaged IFR flight plans that let you fly between airports without needing to talk to Center. Instead, you’ll talk to Tower and Approach.

Flying the OshKosh Fisk Arrival

Every year hundreds of pilots flock to OshKosh’s AirVenture show, flying the well-known Fisk Arrival to get there.

Flying a DME Arc

Before GPS and RNAV approaches, pilots needed another way to precisely fly an instrument approach where VOR intersections were not available. Distance Measuring Equipment (DME) allowed pilots to fly an arc of an orbit around a fixed point, executing a turn to line up with the runway.

VFR Navigation using NDB, VOR and visual references with Special Flight Rules

There are many tools for VFR navigation, and I use them all here.

VFR flying with visual navigation only

The main tool a pilot needs for VFR navigation is his eyeballs. The photogrammetry in MSFS is so good that you can navigate like a real-world pilot, spotting buildings, roads, and rivers to get you there.

VFR Flight Planning using Visual References

You’ll need a plan before you climb into the pilot’s seat.

Pattern Work/Touch and Gos

I use visual navigation to fly to a Class Delta airport and execute a few touch and gos while remaining in the pattern.

I hope you enjoyed these!

August 13, 2021

Bernard's Dream: Deleted Scene

A funny thing happened as I embarked on the journey of penning Bernard’s Dream: I became a plotter. In writer’s jargon, there are two types of writers: pantsers and plotters. Pantsers write by the seat of their pants, telling themselves the story as they go along. Plotters write an outline, filling in the details as they write each scene. In real life, I am a solid plotter. After all, I’m an engineer, and that’s kind of our thing. For writing, however, I’ve always been a pantser, and that’s because I get my ideas as I write. I’m actually a little perplexed why I wrote out Bernard’s Dream as a scene-by-scene outline, but wow — it is so much easier to write a story when you have all the scenes laid out. I think the reason I was able to switch to this approach is because I felt very comfortable with the characters and goal of the story, so the scenes were clear to me. It also helped with theme. One of book’s themes is aging and time, and plotting ensured it was woven through the assorted scenes. That doesn’t mean I had everything worked out. For example, my original notes for the ending problem simply stated “The Stars need something from Promise and it’s going to be very difficult to get.” That’s quite a simplification of the multiple problem-solving scenes and climatic resolution that ended up in the book. Other parts of the outline were beat-for-beat, however. The beginning chapter outlines had exactly the scenes with Willow at Apogee, Will at the Griffith Observatory, and Sarah with the Nightcrawler.

One of the nice perks of plotting versus pantsing is that you throw less away. When pantsing, I’ll write entire scenes, decide they don’t work and then rewrite them from scratch. Quite a few scenes end up on the cutting room floor. With plotting, the only scenes I deleted were for pacing. It was actually harder to delete: they were good scenes, right on point with the story’s themes, but I could tell the reader would skim them. In Bernard’s Dream, this was the get the crew off Earth problem and scenes that got deleted stood in the way of that goal.

The single scene that got cut was titled “Captain’s Launch Party”. Here, James meets the captains and AIs of the other starships. I do intend to write short stories featuring their adventures, so this was mainly a setup scene (which is why it got cut). With it cut, you only see the other captains’ ships and briefly hear Noah Bouchard address the fleet. From a pacing standpoint, this was replaced by James and Will’s beer on the front porch the night before launch, which thematically was more on point. Here’s the original scene:

Captain’s Launch Party (original opening to Chapter 12: Dreams)Twilight over the Amalfi Coast is spectacular from the hotel’s open-air terrace perched three-hundred-and-fifty meters above sea level. Colorful house lights speckle the residences cascading down the shoreline with curving mountains jutting from the sea. The terrace itself is adorned with amber crystal lamps, each casting their own oasis of light from slender Roman columns. James stands there, drink in his hand, taking in the sights and enjoying the fresh air of the hot July 2094 night. Behind him, the hotel’s ballroom is filled with people in formal wear. It’s the Captain’s Party for the crew of the five starships, organized by the United Nations and hosted here. The hotel is theirs for the next week to enjoy the finest luxuries Earth has to offer. Tonight is the gala, filled with speeches and photo ops. Earlier, James caught himself smiling as he shook hands with everyone at the world leader’s table. “Mister President, Madame President, Mister Prime Minister, Madame Secretary General, Mister President,” he was saying. The crews of the five ships represent Japan, China, Canada, Sweden, Spain, Finland, Hungary, Austria, the Czech Republic, Greece, and the United States. That’s a lot of world leaders. Here he was, breaking bread with them all.

Soft footfalls sound behind him and a woman’s hand touches his elbow. When he turns, Willow is standing there wearing a striking red gown with a diamond pendant dancing down into her v-neck. Her blonde hair is down and teased into waves. “Catching a little air?” she says. “Not like you to be on your own.”

James raises his eyebrows. “Had to rest my cheeks. Getting tired from all the smiling and hand shaking.”

She points to a dimple in the side of her mouth. “Get’s you right here, doesn’t it? Takes practice.”

“Probably why my movie star career never took off.”

She glances back over her shoulder. “There’s some captains that want to meet you.”

James takes a sip of his drink. “Well, now, that’s more my speed.”

She turns and walks back into the ballroom, James in tow. Soft, ambient music plays in the background and the din of conversation washes over them as they navigate amongst the crowd and tables. At this time of night, people have mingled into clusters, chatting and enjoying the party, and the demarkations of nationalities have faded. There’s something uplifting about it, seeing each nation leave the tribe of its table and merge with the others in conversation. After all, it’s what the United Nations is all about. Equally interesting is the table that contains five screens pulsing with their own colorful ripples. Ananke’s familiar blue screen is one of those faces. Two women are chatting with the AIs, and Willow leads James to them.

The closest person is a forty-year-old Japanese woman with short black hair cropping her cheeks. Willow smiles to her and offers a bow. “Ichikawa-san, hajimemashite.”

“Hajimemashite,” the woman says, returning the bow. “Please, call me Hana, Miss Parker.” Hana extends her hand towards James. “Mister Hayden, it’s an honor.”

James shakes her hand. “Honor’s mine. I’ve read about your career. Very impressive. The Peregrine couldn’t have a better captain.”

“Thank you,” Hana says. She motions with her left hand to the woman beside her, a fair-skinned person with striking blue eyes and medium blond hair. “Have you met Captain Erikkson?”

James extends his hand. “James.”

Captain Erikkson accepts it. “Maja. Good to meet you, James.”

“You’ll be commanding the Aletheia?”

“Yes, returning back to Astris to study the Mimic. I was just talking with Ananke about your experiences there. Any tips?”

“Come in peace, but be prepared to fight. I think that’s the thing that took the most adapting to once we got out there.”

She nods. “We’ve reapplied your ship’s upgrades. I think it’s wise to be prepared.” Maja points to an undulating blue screen near her. “Lewis and Ananke are chatting up a storm. It’s helpful to build upon what you’ve already discovered.”

“Hello, Mister Hayden,” Lewis says, a ripple of purple curling through his display. “It’s very exciting to meet you. I’m learning great things from Ananke.”

“Hello, Lewis,” James say. “I, too, am always learning great things from Ananke.”

Ananke’s screen introduces a swirl of purple and she says, “James, allow me to introduce you to Taki, who will be on the Peregrine, Anning, who will be on the Xuanzang, and Strava, who will be on the Dayspring.”

The three AIs respond one after the other. “Hello, James.” He nods and smiles.

Two more people stroll over from his left, coalescing on the captain’s gathering forming in front of the AI table. The older of the two men has spiked black hair with silver tips. He shakes James’s hand and says directly, “Chen Wu, Xuanzang.” The second man is in his thirties with wavy medium-brown hair and a hint of a stubbly beard. His smile is warm. “Noah Bouchard, captain of the Dayspring. It’s a pleasure, captains.”

Willow takes a sip of her wine. “Well, look at us. This is quite a remarkable gathering. The leaders and crews of the ships that will open the doorway to the stars. It’s a bit surreal, isn’t it?”

“Well,” Noah says, “we’re here because you and James made it happen. That was a hell of a speech at the U.N. I remember watching your first Mars flight back in ’81.” He leans in. “You know, I was still in college back then. I would never have thought I’d be flying off to the stars now on my own Riggs ship.”

There it is again, James thinks, the time jump. He still can’t get used to the nine-year fast forward, and he’s not sure what twenty-eight years will feel like. James waves a hand. “I just floated the idea. You all took the conn.” In the corner of his eye, he catches a glimpse of their respective crews mingling in the background. Each ship has a similar setup to his, with engineers, pilots, astrophysicists, astrobiologists and other sciences making up the roster. So many people — forty-four between the five ships and the AIs.

He spies Hitoshi and Lin talking with the Xuanzang’s pilot and engineer, and he recognizes the two Chinese members, Jia Xu and Ping Lao. They were the two freighter pilots that took on pirates over Uranus around the same time he did the Mars flight. Jia could fly, he remembers, outmaneuvering combat craft in a hauler. He’s always wanted to meet her and ask her about her experiences. If he didn’t already have a pilot and engineer, he probably would’ve recruited them. The Xuanzang will be in good hands.

He snaps his attention back to the group, conjuring a smile and raising his glass. “Taking the lead is what it’s all about. You’re the Armstrongs, taking the first step into unknown soil, carving your bootprints into a path so that those who follow know the way.” He quirks his head. “Like Willow said, each of us is reaching for a door handle, and when we open it, Earth will no longer be a lone blue point in the darkness, but instead, a collection of worlds with new lights joining in with each new step you take.”

“Hear, hear,” Noah says, lifting his glass. “To our fine crews and all of the captains. May our journeys be swift and safe, and may the stars shepherd us to new wonders.”

The captains all clink their glasses and take a sip. As James swallows his champagne he glances at Ananke. He’s known her long enough that he can pick out specific shades of blue in her calm face. Her currents have tinges of Bernard’s Blue, the sad color she conjures whenever she is thinking of Bernard Riggs, but they glide in parallel with gleaming aquamarine. Pride. Contentment. She’s sad that Bernard is not here to see his dream realized to its fullest potential, but she’s proud that it is being realized and they are launching Earth’s first star fleet.

James lifts his glass in her direction and gives a soft smile and nod, and Ananke’s screen pulses twice as she watches, her face the picture of serenity among the five swirling screens of the AIs.

I hope you enjoyed the glimpse of what didn’t make it into the book. Thanks, as always, for reading!

August 3, 2021

New Release: Bernard's Dream

If you’ve read Bernard’s Promise, you’ll know that it ended with the crew returned to an Earth that had aged nine years while they were gone. Riggs technology was outlawed after a Subversive attack, and James was back in Hayden-Pratt’s CTO seat, wondering what to do next. Of course, you know James — when faced with a barrier he tends to go big — and now you can find out what that looks like in the newest Hayden’s World novel, Bernard’s Dream. Clocking in at 87,000 words, it’s the biggest story to date. The crew faces dangers both on Earth and around new stars, so be sure to check it out. Bernard’s Dream is available on Kindle and paperback on Amazon (and is free if you’re a member of Kindle Unlimited).

July 16, 2021

Rock Your Wings - Flying with Real ATC at SimVenture 2021

When the real-life AirVenture was cancelled at OshKosh last year, PilotEdge rose to the challenge and organized a virtual version of the event. What was particularly awesome is that they used the real-life OshKosh air traffic controllers for the virtual fly-in, and I was one of the virtual pilots. It was an awesome experience and I felt like I’d accomplished something flying the Fisk Arrival while getting direction from real-life ATC.

This year, PilotEdge did it again with SimVenture 2021. Last year X-Plane was my simulator of choice, but this year there is Microsoft Flying Simulator 2020. So, I climbed into my virtual cockpit and took to the skies to once again fly the Fisk arrival, rocking my wings over Fisk to let them know I’d heard them. Check out the flight below:

May 22, 2021

Thoughts on Andy Weir's Project Hail Mary

Andy Weir is a self-published author’s hero. When he originally wrote the Martian, he published it one chapter at a time on his blog for his friends to read. His friends really enjoyed it, but some found it hard to read on their computers and requested that he publish it on Kindle. He originally planned on giving it away, but Amazon requires you to sell ebooks for a minimum of 99 cents, so that’s what he did. It turns out that a lot of people really enjoyed the Martian, and, next thing you know, Matt Damon is playing his main character in a blockbuster.

I stumbled upon the Martian on Goodreads. Based on the reviews, it was a very polarizing story. Either people really enjoyed the MacGyver-like survival science or they really hated a science lesson wrapped in a story. As a hard science fiction writer myself, I can sympathize with this problem. I’ve gotten my share of one-star reviews from readers expecting lightsabers and dogfights who were unhappy with chapters on planetary science and alien biology. So, I decided to give the Martian a try.

It’s hard not to know the setup of the Martian by now, but if you haven’t read it, it’s set in a near-future Mars mission where the crew abandons their Mars habitat during a severe storm, returning to Earth. During their evacuation, one of their crew members is killed and they are forced to leave his body behind. What they don’t know is that he’s still alive and they’ve abandoned him. It will be four years before anyone can return for him, and he only has thirty days of food. Fortunately, the left-behind astronaut is the mission botanist, and he engineers a way to make food for himself as well as contact Earth to orchestrate a retrieval. Faced with a series of impossible problems, he famously says, “I’m going to have to science the shit out of this.”

I greatly enjoyed the Martian’s problem solving. It was like watching MacGyver escape from a vault by freezing some water into the lock. The parts of the writing I initially didn’t enjoy were the characters and dialogue. The trapped astronaut, Mark Watney, spoke and acted like a texting fourteen-year-old boy. It was hard to believe he was a NASA astronaut. For example, when Watney connects live with Earth and is told his text messages are being seen by everyone, he types “Boobs!” and snickers. All of Watney’s victories are accompanied by “woo-hoos!” and “yeahs!”. In general, Watney starts the book as a very annoying character. A funny thing happens to the reader along the way, though.

I recently watched the Amazon comedy series Ted Lasso, which is about an American football coach who moves to England to coach a Bad-News-Bears soccer team. Everyone is hostile to the idea, but Ted is perhaps the world’s nicest and most optimistic man, winning over the hearts of everyone he encounters and transforming his team of I’s into a team of We’s. The opening credits are the best analogy for the series. In them, Ted sits down in blue bleacher seats, and, one-by-one, they turn red around him.

Mark Watney in the Martian is like this. He faces so many impossible changes with his high spirits and can-do attitude that you, too, can’t help but root for him and genuinely want to see him rescued. It’s the overwhelming theme of the story: human ingenuity, perseverance and hope will prevail.

Weir’s second book, Artemis, was set on the Moon. I briefly hoped it wasn’t about someone being left behind on the Moon (it wasn’t), but the actual plot faltered and lost the magic of the Martian. It follows Jasmine Bashara around a moon base in the 2080’s (same year as the Hayden’s World series!) as she becomes entangled in a conspiracy to control the base. What I recall about the story is that the descriptions of the moon base and lunar surface were interesting, but the plot itself didn’t engage me.

Weir’s most recent book, Project Hail Mary, is a return to the formula that made the Martian so successful. It once again creates a main character who is completely cut off from humanity who needs to solve a series of technical problems to succeed. The premise is that Earth’s sun is mysteriously dimming and soon all life will perish. The reason for the dimming is a microscopic spacefaring life form that flies in an arc between Venus and the Sun, stealing a little energy from the Sun with each trip. All of Earth’s neighboring stars show the same dimming except for Tau Ceti. So, Earth builds an interstellar mission to Tau Ceti to understand why that star is unaffected and hopefully bring a solution back to Earth.

The story starts out a bit cheesy with an astronaut with amnesia who awakens upon a ship. It’s a narrative construct to dole out back story and it has a soap-opera plot feel to it. Once the amnesia wears off and the mission is revealed, the story starts to pick up. The main character, Ryland Grace, is the sole survivor of the three-man mission. The technology is current day’s and the way Earth constructs a ship capable of reaching Tau Ceti in only a few years is clever. Where the story really takes off, however, is when Ryland arrives at Tau Ceti and discovers another alien ship is also there. Similar to Ryland’s situation, the alien is the sole survivor of his mission and is also searching for a cure for his home world’s dimming star.

Weir clearly put a lot of thought into his alien and I appreciate that it is, indeed, alien. You’ll find no Star Trek “human with a nose wrinkle” vision of aliens here. The human and alien environments are so different that each would be nearly instantly lethal to its counterpart. The alien lives on a Venus-like super Earth with intense pressure, heat, and gravity. Because it looks like it’s made of rock, Ryland nicknames it Rocky. Fortunately for Ryland, Rocky acts very human. He carries tools, wears clothes, is intensely curious, wants to work together, and is even a bit sarcastic. The two quickly develop a way to communicate and in no time are speaking to each other with the assistance of a laptop.

The Rocky/Ryland partnership is the gem of the story. Rocky has a distinct personality and is very gung ho, and this taps into the optimism theme that permeated the Martian. At times he’s a bit too human, doing things like shaking his first in anger and pointing to a clock when Ryland is late, but it’s forgivable. After all, we need to relate to Rocky to like him, and if he were a completely inhuman rock that would be difficult. I thoroughly enjoyed the partnership’s fascination and curiously with each other. Rocky is just as amazed that humans can breathe dangerous oxygen and can “hear light” with their eyes as Ryland is that Rocky doesn’t need to breathe and has a body temperature in the hundreds of degrees. Surprisingly, Rocky’s home world is lower-tech than Earth’s. They have no computers, don’t understand relatively, and have still managed to build an interstellar ship using math they do in their heads. It’s a bit like watching a bunch of 60s NASA engineers do rocket math with slide rules and still plop a craft down on the Moon. It’s great fun seeing Rocky and Ryland compare notes. “Humans are weird,” Rocky states more than once.

I did cheer when the book had its “science the shit out of it” moment with this quote spoken by Rocky in broken English:

“You ship has more science than my ship. Better science. I bring my things into you ship. Release tunnel. You make you ship spin for science. You and me science how to kill Astrophage together. Save Earth. Save Erid. This is good plan, question?”

“Uh…yes! Good plan! But what about your ship?” I tap his xenonite bubble. “Human science can’t make xenonite. Xenonite is stronger than anything humans have.”

“I bring materials to make xenonite. Can make any shape.”

“Understand,” I say. “You want to get your things now?”

“Yes!”

I’ve gone from “sole-surviving space explorer” to “guy with wacky new roommate.” It’ll be interesting to see how this plays out.

Weir, Andy. Project Hail Mary (p. 254). Random House Publishing Group. Kindle Edition.

Ryland is also toned down versus the Martian’s Watney. He’s played as a nice guy in a generally desperate situation who doesn’t give up. Admirably, he makes a genuine friendship with Rocky and is willing to risk his life to save him, as Rocky is willing to risk his to save Ryland.

I should note that, similar to the Martian, the story alternates between scenes with the isolated astronaut and scenes back on Earth. The Earth scenes are all flashbacks, dealing out chunks of story about how the Sun’s problem was detected and how the starship was built. While necessary, I found them not very engaging and often leafed through them. The real story is Rocky and Ryland’s. Weir, like many hard science fiction authors (myself included), wants to ensure the reader knows how everything works and fits together. Really what engages the reader is the Rocky/Ryland friendship and their teamwork. There’s a bit of a writing lesson to be learned there for character over world building.

I enjoyed Project Hail Mary and I think Weir has another winner. Be sure to check it out if you enjoyed the Martian.

May 16, 2021

Thoughts on Netflix's Love, Death and Robots Season 2

Season One of Netflix’s Love, Death and Robots was released in 2019, consisting of eighteen sci-fi short stories based loosely upon the themes of the series title. I’d read many of the stories before because they were by my favorite authors, such as John Scalzi and Alastair Reynolds. While it was exciting to see a sci-fi anthology flex its technical muscles to stunningly visualize some of those great shorts, as a whole I felt disappointed that many of the shorts focused on nudity and violence for the sake of rendering them in high-definition CGI glory. There’s a certain Mortal Kombat vibe that some video games emit where the focus is on the gory fatalities and this focus reduced many of Love, Death and Robot’s Season One’s episodes to video game status. There were still some great episodes in Season One, but as a whole they were the diamonds in the rough.

This week, Netflix released Season Two of Love, Death, and Robots. Where Season One’s eighteen episodes were more of a throw-spaghetti-on-the-wall-and-see-what-sticks approach, Season Two’s eight episodes feel more like a carefully-selected collection for your consumption. Similar to Season One, the stories are bingeable shorts that can each be watched in ten to fifteen minutes. The author roster isn’t as recognizable as the first season (other than John Scalzi and Paolo Bacigalupi), but this is a plus, as I hadn’t read any of these stories and it was enjoyable encountering them for the first time. The gratuitous nudity from the first season is gone. In fact, only two episodes contain any nudity, with Snow in the Desert showing a woman’s bare back before fading to black to imply a sex scene, and The Downed Giant taking a detached, clinical view of a giant naked man’s body awash on a beach. The violence has also been toned down with only one episode, Snow in the Desert, containing a high level of gore. I was happy to see these changes. I don’t have issues with stories that contain these elements, but I want the story to be the focus, not the elements.

When I wrote my review for Season One, I grouped the episodes into Best and Worst categories. Season Two doesn’t lend itself to this, in part because there are half as many episodes, but more so because all of the stories are done well and there are none that should be skipped. So, instead, I’ll present them in order with my thoughts on each (and I’ll try to avoid spoilers where possible):

Automated Customer Service - A women’s Roomba-like housekeeping robot turns murderous after she and her dog interfere with its tasks. Based upon a very short John Scalzi story (https://whatever.scalzi.com/2018/11/19/a-thanksgiving-week-gift-for-you-automated-customer-service/), the animation renders everyone in caricature and the tone rides the line between farce and horror. If you don’t know it’s a Scalzi story, you might be confused upon first viewing, wondering whether it’s meant to be funny or scary. It makes perfect sense once you realize that it’s Scalzi’s sense of humor (he is the author behind Red Shirts, after all). I will say that Scalzi’s written version is told entirely from the automated customer service bot’s voice and is funny because of its escalation and that you need to infer what’s going on from the responses. The animated version is from the perspective of the terrorized woman and this causes the automated voice’s snarkiness to seem out-of-place.

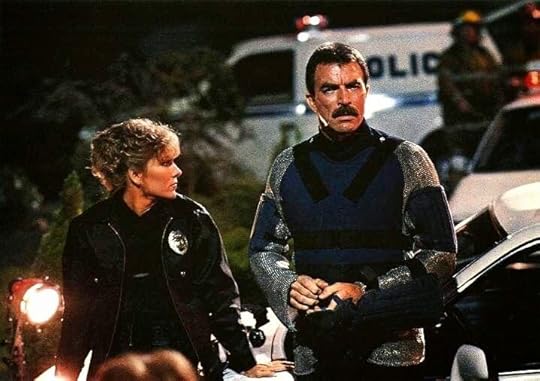

The animated version reminds me a bit of 1984’s Runaway with Tom Selleck, where a housekeeping robot goes on a murder spree in a family’s house before being stopped by Selleck.

Ice - On an alien world where most humans are modded with enhanced strength and agility, an unmodded teenager feels left out, trying to prove himself in a dangerous race. The episode is hand-drawn in an animated style that you will instantly recognize from the Zima Blue episode of Season One.

This story reminds me of 1997’s Gattaca, which also focused on two brothers, one of whom was genetically enhanced, and the normal brother’s willingness to risk his life to outdo his enhanced sibling.

[image error]Ethan Hawke in Gattaca, winning the race because he didn’t save anything for the swim back

Read Rich Larson’s original short story in Clarkesworld http://clarkesworldmagazine.com/larson_10_15/

Pop Squad - In a dark future where the rich are immortal, unregistered children are illegal, hunted and killed by the police. The protagonist is one of those police and faces a crisis of conscience. A dark, heavy story with some Blade Runner-like visuals and themes. The original short was written by Paolo Bacigalupi, author of the Windup Girl https://windupstories.com/2007/02/11/great-review-of-pop-squad/

Snow in the Desert - On a desert world at the galaxy’s outskirts, an ageless man is pursued by bounty hunters set on harvesting his body parts. Out of the Season Two episodes, Snow in the Desert is the most technically advanced, with CGI that had me questioning whether I was watching live action or animation. This episode makes me believe that you could make movies with entirely CGI actors. The setting is merciless and the violence follows suit, but it all makes sense in the context of the world. The feeling is that of Chronicles of Riddick without the campiness. The original short is by Neal Asher https://www.nealasher.co.uk.

[image error]The Tall Grass - When a train stops briefly in the middle of nowhere, a passenger investigates lights in the surrounding tall grass fields. The animation is intentionally low FPS and has a stop-motion feel to it. The story itself feels like something out of Cthulu. The original story is by Joe R Lansdale https://www.goodreads.com/book/show/23626097-the-tall-grass-and-other-stories

All Through the House - When two children stay up late on Christmas Eve to spy on Santa, they find something terrifying. This episode looks like it is straight from Guillermo del Toro’s mind, but is written by Joachim Heijnderman (https://gallerycurious.com/2017/12/24/christmas-eve-extra-all-through-the-house-by-joachim-heindermans/) Dark humor done right.

Life Hutch - When a man’s starfighter is shot down, he must survive planetside in an emergency shelter until he is rescued. Unfortunately for him, his company is a malfunctioning murderous maintenance robot. Great visuals throughout this episode, from the military space battles to the cat-and-mouse game of the man and robot. There is almost no spoken dialogue, but the whole story is tense and tight. As a writer, I particularly appreciate how the director trusts the viewer to understand how the robot is reacting and what triggers it.

The original short is by Harlan Ellison, published in 1974’s Deep Space. Harlan Ellison is the writer behind countless classic sci-fi TV series episodes, notably including the 1960s Star Trek episode “The City on the Edge of Forever” where Kirk, McCoy and Spock travel through a time portal to 1930s Earth, encountering Edith Keeler (Joan Collins).

[image error]The Downed Giant - When a giant man’s naked corpse washes up on the beach, a local scientist documents the fishing village’s reaction. The resulting story is a vignette of humanity. The story has a Gulliver’s Travels feel to it, and the narrator’s dialogue is nearly word-for-word from the original short by J.G. Ballard http://lucite.org/lucite/archive/fiction_-_ballard/ballard,%20j%20g%20-%20drowned%20giant.pdf, which is a good thing. A strong story to end the series.

My overall verdict: Recommended. The selection of stories is tighter and the quality better than Season One. An enjoyable way to spend a weekend night.

April 25, 2021

Thoughts on Netflix's Stowaway

Netflix released the original sci-fi movie Stowaway this weekend and I promptly spent one hour and fifty-six minutes of my Saturday night watching it. There’s a bit of a minimalistic art to writing the one-sentence movie summaries that appear in television channel guides and Netflix’s Stowaway website condenses it to “A three-person crew on a mission to Mars faces an impossible choice when an unplanned passenger jeopardizes the lives of everyone on board.” The three-person crew is an A-list of actors: the captain, Toni Collette; the doctor, Anna Kendrick; the botanist, Daniel Dae Kim. The fourth man - the stowaway - is played by Shamier Anderson. Everyone’s acting is top-notch and the characters are all relatable and likable.

Stowaway is near-future science fiction with technology and ships similar to the Martian. On a spectrum where space opera is a one and hard sci-fi is a ten, Stowaway is a seven. The ship is well thought out and logical and the characters operate within the rules and constraints of their environment, but the science is an undercurrent to the morality-driven drama. The film’s structure is more like a one-hour television episode, or perhaps a play, where a small cast is constrained to two or three set locations and faced with a dilemma.

The movie starts with the crew’s launch from Earth, the rocket engines shaking everyone violently with each actor showing how unpleasant the experience is.

It reminds me a bit of Ryan Gosling’s opening space launch sequence in First Man. In First Man, launches are noisy, violent, and terrifying, with the ship’s hull screeching like horror movie screams due to temperatures and stresses.

In Stowaway, the launches aren’t as violent, but they seem unpleasant, and Daniel Dae Kim’s character vomits once they make orbit. The crew of three is on a two-year trip to Mars and become committed after a final acceleration and ship setup.

The plot kicks in when the captain finds an unconscious man in the ceiling. When she opens the panel supporting him, he tumbles out like a body in a horror film, falling on her and breaking her arm. Critically, his fall damages the life support system. After his wounds are treated by the doctor, he awakens to reveal he’s an engineer who became trapped in the ship during ground checks (point of order - he’s not actually a stowaway because stowaways intentionally hide aboard a ship. He’s more of an unintentional passenger). He’s truly in a panic when he discovers that he’s in space, now committed to the same two-year mission as the crew. The crew does a good job of integrating him and making him feel like one of them - they even have him sign the mission plaque - but in the background the captain realizes that four people on a three-man ship with a damaged life-support unit means that no one will live to arrive at Mars in two years.

The setup is familiar in isolation stories. A small group of people, stuck someplace, do not have enough food, water, air or other vital resources for everyone. It’s the triage nightmare that’s always in the back of human thinking: what would I do if there wasn’t enough for everyone? Spaceflight lends itself to this type of story naturally. It immediately reminded me of 2007’s Sunshine, where an accident during a spaceflight to the Sun results in the crew not having enough oxygen for everyone. One person must die to balance the equation. They draw straws at one point to choose their sacrifice. In that movie, they are spared needing to murder a crewmate when the crewmate commits suicide.

2007’s Sunshine - the first half of the movie was pretty good, until it went off the rails at the midpoint and turned into a monster flick

Stowaway has a similar setup where the crew wrestles with the morality of killing the stowaway, offering him a painless way to commit suicide. The story does a good job of having the three main crew members each represent a different point-of-view. All three are aghast at the thought of killing the stowaway, but Anna Kendrick’s doctor is the optimist (save the stowaway at all costs); Toni Collette’s captain is the pragmatist (do what is necessary to save the crew), and Daniel Dae’s botonist is the rationalist (every day they delay the inevitable jeopardizes them all). It is Daniel Dae who hands Shamier the suicide option, going against the will of the crew.

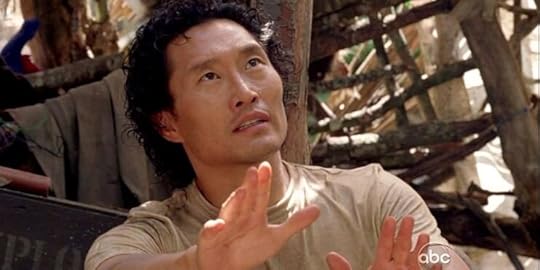

Incidentally, Daniel Dae Kim is no stranger to sci-fi and space stories. You’ll certainly remember him as Jin on Lost.

He also appear both in Star Trek: Voyager and Star Trek: Enterprise. In Voyager, he was an astronaut on a world where time spun faster than the rest of the universe, with Voyager snagged in the world’s orbit in the episode “Blink of An Eye”. Blink of An Eye was an excellent sci-fi story, and I remember his character singing his world’s version of Twinkle Twinkle Little Star, where Voyager was the star.

In Star Trek: Enterprise he was Corporal Chang, one of the MAKOs (Enterprise’s Special Forces).

In the Babylon 5 spinoff, Crusade, he played John Matheson.

I couldn’t find any space shows for Toni Collette or Anna Kendrick, but in the sci-fi/fantasy realm you’ll remember Anna from Scott Pilgrim versus the World.

Stowaway is described as a “sci-fi thriller” but that is a bit of a stretch. It’s more of a sci-fi morality play. The story takes its time following the characters around their daily business and decision-making aboard the ship with extended conversations over algae racks or sitting in front of the cupola while Earth and stars spin outside. A heroic spacewalk scene in the last act is interesting, but not thrilling. Although it is a life-or-death situation, the tension feels numb in the dreamy slow-motion weightless of space, and the inevitability of the movie’s realistic logic means we have low-expectations for that mission’s success.

Overall, I liked Stowaway. I have a special fondness for intelligent sci-fi that takes its time and has environments that feel authentic. One of my criticisms is that the story didn’t develop its characters very much. We know very little about each of the crew other than their titles and dominant personality trait (“doctor/empathy”). The extended conversations over algae were often about superficial topics, such as why Daniel Dae’s character likes jazz, and it feels like a missed opportunity for back story. The only character who has any backstory is the stowaway (he cares for his younger sister and is stressed that he’s cut off from her in space). The other criticism is that it is, perhaps, too logical. The situation matter-of-factly gives the characters the grim news and then puts them on rails. In real life, we’re served up impossible situations and we’re sourly stuck with the outcomes. In stories, though, we like to see perseverance. In stories like the Martian, the lead character is served with an unsurvivable scenario and we enjoy watching him think his way out of the impossible. The Martian would not have been a good story had Watney slowly starved to death, the film ending with a panning shot of his slumped body at his desk. It would have been logical, but not cinematic. I will also say that for a story locked into its own logic, the setup of how and why the stowaway is trapped in the ceiling isn’t really explained other than an accident occurred during ground checks, and the movie rolls forward with some brief hand-waving.

So, if you enjoy movies like Gravity, the Martian, or even 2001: A Space Odyssey, check out Stowaway. It’s not a bad way to spend two hours on a Saturday night.

February 13, 2021

Save the Fish

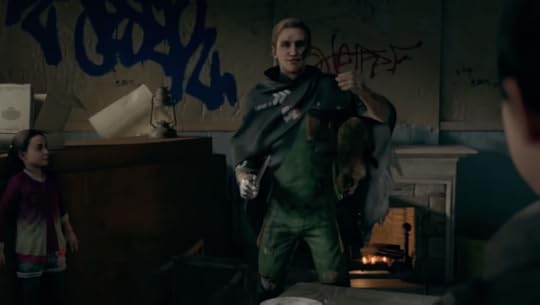

One of the great accomplishments of Quantic Dreams game Detroit: Become Human is that its ending is truly in your own hands. There is no right way to play it, although there are optimal outcomes where everyone survives and achieves his goals. But does the best outcome yield the best story?

SPOILER ALERT: THIS ENTIRE POST ASSUMES YOU’VE PLAYED THROUGH THE GAME AT LEAST ONCE

The best outcome is the peaceful protest with Connor turned deviant and Kara, Alice, and Luther taking the bus to Canada. If you’ve played your cards right, everyone survives and the androids are free.

Just because it’s the best outcome doesn’t mean it’s the most compelling story. If you think about a movie like Star Trek II: The Wrath of Khan, you can imagine how less compelling the ending would be without Spock’s sacrifice.

In writing, when a character develops over the course of a story it’s called an arc. Arcs can be positive (Daniel and Miyagi in the Karate Kid facing the bullies) or negative (Walter White’s downward spiral in Breaking Bad). In the game, Connor and Marcus both have positive or negative arcs based upon your choices. Connor’s arc gets the focus in the game, though, and has the most impact on the story.

Positive Arc: Connor’s relationship with Hank causes him to become more human, ultimately joining with the deviants to help liberate them.

Negative Arc: Connor loses his humanity in his obsession to achieve his mission, becoming the villain.

If I put my writer’s hat on, scenes should be structured to invest us in Connor’s quest and show his arc. Characters should sometimes fail, and even die, to support that arc. The best story isn’t always the happiest one. Here’s the choices I’d make to have the best storytelling experience for the positive arc. I haven’t listed every chapter in the story because some, like “The Interrogation”, are more video-gamish where you simply need to get to the scene end without messing up. Instead, I’ve listed some of the key fragments that best build the story:

The Hostage:Save the Fish

Our introduction to Connor nails two writing tricks right off the bat:

1) When we first meet a character, try to have him doing something unique to his personality or skills that immediately shows us something about him. For Connor, he is tossing a coin back and forth with android precision.

2) Try to have the character help or show a kindness to someone that he doesn’t need to help. This establishes that he is a good person to be admired and trusted. Putting the fish back in the tank is the kindness. For Connor’s arc, this shows that he is not just a machine, but has empathy.

Save the Policeman

A bleeding policeman lies outside on the terrace. If Connor stops to help, Daniel threatens to kill Connor. If you choose to ignore Daniel and help the policeman, you are rewarded with one of Connor’s great lines, “You can’t kill me, Daniel, because I am not alive.” Saving the policeman jeopardizes Connor’s mission, which is why this is a great “show, don’t tell” moment for establishing that Connor cares about people (and you will encounter the saved policeman later in the game when he thanks you during your investigation at the Stratford Tower).

Push Daniel and Yourself off the Ledge to Save Emma

There are three ways to save Emma. From a game standpoint, the best way is to talk Daniel into trusting you, which results in him releasing Emma. Here, you promise nothing will happen to Daniel…then you nod to the snipers when Emma is clear and they kill Daniel.

From an arc standpoint though, this establishes that Connor will lie to get what he wants. Connor also immediately turns his back on Emma and ignores her, his mission complete. The second option is to get close to Daniel and shoot him. Once again, Connor ignores Emma and walks away. It also undermines the scene as there is nothing special about Connor required for him to simply pull a gun and shoot Daniel. The third option is the best from a story standpoint: Connor tries to talk Daniel down, but Daniel flings himself and Emma off the ledge, Connor lunging for them in response. Connor manages to grab Emma’s hand and pull her back onto the ledge, but at the cost of sending himself and Daniel off the ledge. Here, Connor is the hero, sacrificing himself to save Emma. It’s also a nice reversal at the end of the story hook because you don’t expect the protagonist to die in the opening scene. It also saves Emma in a way that is unique to an android because Connor simply comes back after his death in a new Connor unit.

The Painter

The PainterPlay Chess

Dave Cage, the writer and director of Detroit: Become Human, does quiet moments exceptionally well. Out of the options Marcus has to occupy himself while Carl has breakfast, playing chess is the interactive choice. Marcus joins him and gives him a life lesson as his mentor, which builds Marcus’s arc. Each of the other options, such as reading a book, also result in a life lesson from Carl, but in chess you are directly engaged with Carl. Chess also provides a nice allegory for the branching choices Marcus must make throughout the story.

Stormy Night:

Stormy Night:Don’t Take the Gun

Kara’s character is so much more compelling and human when she is vulnerable and trying to protect Alice. The gun negates that vulnerability. When she encounters danger later on, such as the unstable knife-wielding android Ralph, the whole scene is less tense when you know Ralph has brought a knife to a gun fight. The other problem with taking the gun is that once you draw it, your only option is to shoot and kill Alice’s father, Todd. Kara is a caretaker and her role is to whisk Alice out of harm’s way, not leave a trail of bodies in her wake.

Fugitives:

Fugitives:Stay in the Motel

Out of the three overnight options, staying with Ralph is the most interesting, but from a character development standpoint it’s one of those choices that readers would shake their head at. A clearly unstable Ralph just held Alice at knife point. No mother would choose to let Alice sleep in his house (and if you’ve played the Ralph scene you knows it wraps up poorly).

Having Kara back away and say “no, we should be going” gives readers confidence in her protector role. From a pacing standpoint, the motel gives the characters a little downtime to talk, and Kara closing the blinds and lying down next to Alice in bed is compelling. Stories need breathers from tension.

On the Run:

On the Run:Fail at Sneaking Past the Police

As Hank and Connor close in on Kara’s motel room, Kara and Alice slip out and try to make their way to the train station, sneaking past police. If they succeed, they’ll quietly get on the train. If they fail, they’ll make a dramatic run for it pursued by Connor, trying to lose him in a nearly-suicidal rush across a high-speed autonomous vehicle highway. This scene is really great because it pits two protagonists, who are both good guys that you want to survive, at odds with each other. Connor should choose pursuit, since he always views his destruction as a temporary inconvenience. This is an interesting chapter where failing your objective (sneaking past the police) is much more interesting (and better storytelling) than succeeding. Readers like to know that characters can fail because it creates tension each time the characters are tested. It’s also one of the only story choices that bring Kara and Connor together.

The Nest

The NestSave Hank

Most players pick this option because, well, we’re human and wouldn’t watch our partner fall to his death. Letting the deviant get away so Connor can save his partner is another moment to show that Connor values human life more than his mission. It’s also essential to developing a genuine friendship with Hank, which is what shapes Connor’s humanity. Now, if you are playing the negative arc version of Connor, this is the perfect scene to show that Connor cares about nothing but his mission (Hank pulls himself back up and is furious that Connor left him there to die).

Zlatko

ZlatkoRelease the Monsters to Kill Zlatko

Zlatko is defeated either when Luther shoots him or when Zlatko’s tortured android mob beats him to death. When you write someone as despicable as Zlatko, you want more than a straight-forward “bang! you’re dead” ending. The android mob is fitting. Luther is a kind protector. Although him shooting Zlatko is suitable for his arc, him being spared the choice works better for the gentle android.

The Eden Club

The Eden ClubLet the Tracis Go

A fun fact about this scene is that the actor who plays Connor and the actress who plays the blue-haired Tracy are husband and wife in real life. This is the first scene where Connor shows empathy for another android. I actually think it’s misplaced in story order. The Kamski scene, where Connor chooses not to shoot the Chloe android, should come first. After all, that should be an easier choice, since Chloe has done nothing wrong and is not a deviant. The next step up in empathy would be choosing to spare the Tracis, who have killed a human and are deviants. From a story pacing perspective, I feel the narrative’s transition to Connor letting deviants go here is a bit too abrupt. Connor hasn’t given any indication of showing empathy for androids before this point. This is why I think the Kamski scene should come first. There, Connor isn’t sure why he spared Chloe and Hank reassures him with “Maybe you did the right thing”. This would plant the seed that Hank approves and that sparing androids is the human thing to do.

The Stratford Tower

The Stratford TowerSimon Gets Shot in the Hallway

Readers feel tension when they’re not guaranteed everyone will be fine. Botching the guard ruse and getting Simon shot sets up a good scene where the protagonist’s plans have gone awry and he is trying to salvage them while facing a moral dilemma about how to handle the wounded man. It’s so much better than them all escaping. It frames a choice for Markus that is similar to many of Connor’s and if you choose man over mission you establish that Connor and Markus are on parallel arcs. You don’t get this character development when everything goes as planned.

Note if Simon doesn’t get shot in the hallway, he will get shot when the SWAT team bursts into the control room (assuming you didn’t shoot the fleeing human in the back when you took the control room). The outcome - wounded Simon on the roof - is the same - but the pacing is much better if it happens before they take the control room. If it happens after, they’ve already accomplished their goal and there is less tension.

You can entirely prevent Simon from being shot simply by killing the fleeing human, but for a positive Marcus arc this doesn’t work. Either way, losing a side character works much better than everyone’s plan going off without a hitch, as it raises the stakes by demonstrating that characters can die.

Meet Kamski

Meet KamskiSpare Chloe

The choice here is dependent on Connor’s arc. If he is on a positive arc, then he must spare Chloe. I think Kamski’s empathy test is a great scene because it frames a central theme of the story as a choice for the main character.

Freedom March

Freedom MarchTry Peace But Fight When Attacked

Here is where we need to decide if Markus will use peace or violence to achieve android liberty. I can tell you that readers like characters who stand up and fight. While characters who endure are admirable, we all endure to some extent in our everyday lives. We want to see characters do the things that we can’t. Although the pacifist path in Detroit: Become Human works out better for everyone, it’s the less compelling narrative. Markus should try to be peaceful, but when the police start killing people around him, he needs to fight. Once in the fight, he should fight to defend himself and let the police disengage when they flee. If you choose to fight, this is an exciting action scene with epic music. In terms of story mechanics, fighting is the point-of-no-return door that a main character must open to progress the story. If you back down from the police, you are delaying opening that door and pushing it to a later point in the story that feels out-of-place for readers.

Crossroads

CrossroadsConnor becomes a deviant and Kara, Alice, and Luther are captured

Connor has been on a humanity arc this entire time and this is the place where it is realized. Personally, I think the positive arc for Connor is the better story. Seeing him switch sides and join Marcus is a crowd-pleaser because readers are invested in both characters and the only way they can both succeed is if they are on the same side. The negative arc version of Connor works well as a story also, setting the stage for a final battle between Connor and Marcus, but that feels predictable compared to the twist of them teaming up.

Kara, Alice and Luther will either escape, be captured, or be killed. Escaping will send them on a route to the Canadian border, which will have its own drama but ultimately remove them from the plot. Other than their brief interaction with Marcus at Jericho, this will reduce Kara and Alice’s arc to a background event. Personally I can say that I went back and replayed the story so I could choose to get them to Canada because I was invested in the characters and wanted them to have the happy ending, but in retrospect the plot works better if they don’t go to Canada.

If they get killed trying to escape Jericho, the scene where Kara falls to her knees holding a dying Alice, both shutting down frozen in that pose, is heartbreaking and powerful. But, they are major characters, and their deaths here do not have a purpose other than to pull tears.

The best story is for them to be captured, as this will up the stakes for the finale. From a plot structure standpoint, this takes the three plot threads of Kara, Connor, and Marcus, unites them at Crossroads, and binds them all to the outcome of the Battle of Detroit.

Night of the Soul

Night of the SoulLiberate the Camps by Force

Night of the Soul is a very classic scene showing the protagonists overcoming their self-doubts the evening before the final confrontation. Here you have one final decision to pursue either a peaceful standoff outside the camps or a violent liberation. Although the peaceful avenue is admirable (even if the actual kiss-the-girl and Les-Miserable endings for it are a bit cheesy), the problem is that the narrative has piled endless atrocities upon the heroes, including building actual death camps.

“Do you hear the people sing? Singing the song of angry men…” Oh wait, wrong story.

Readers don’t want passive responses. If you have a character pushed down throughout a story, it is a setup for him to take a stand.

Battle for Detroit

Battle for DetroitSave Hank

At this point, Hank and Connor are friends, and Connor must choose the human life over the mission. As an aside, I love that this scene has fun with the sci-fi trope of “ask me a question only the real Connor would know”.

Alice, Kara, and Luther are in the Recall Center

The recall center is a difficult scene to both watch and play, yet Alice and Kara ending up here makes for a perfect ending since Marcus is no longer just liberating nameless androids but characters you are invested in. Alice, Kara and Luther must stick together and show courage in a hopeless situation. In the end, they will be saved.

The actual battle itself is a bit more video-gamish where the choices mainly affect whether you lose any friends and win the fight. It’s a great bit of action to play through, however, and feels suitably desperate and epic for the liberation of the camps.

Note you will have radically different endings if you choose other arcs for Marcus and Connor. The negative Connor arc works well in that he must fight Marcus (or North) and either fail (because he is the villain and we want him to fail, allowing the true hero to succeed) or he successfully kills Marcus and squashes the rebellion, only to realize his obsession has cost him everything (when Amanda coldly states he will be decommissioned and replaced by a better model, treating him as he’s treated the other androids throughout the story).

All in all, I’m thoroughly impressed with the writing and direction in Detroit: Become Human. The fact that I finished the story and I’m still learning from how it was assembled speaks highly of it. I hope you enjoyed it as much as I did, and I’m curious to hear your thoughts.

February 6, 2021

Thoughts on Detroit: Become Human

A few years ago I played through the Witcher 2 and was captivated. Although the game does have its share of button-mashing sword battles, I spent the majority of my gameplay in interactive cutscenes. The strange thing is that I found myself wanting to soldier through the combat sequences just to get back to the cutscenes. The reason is that the game was like playing an HBO series rich with characters, plots, and consequences. The cutscenes were directed with the same care. I felt like I was playing a movie, not a game.

RPGs have long allowed you to make choices as the hero or villain, but the choices are usually at the extremes of morality. It’s often obvious which choice you’re supposed to make. Ultimately the story wraps up with a quest succeeded or quest failed status. In the Witcher 2, however, something interesting happens after the first act. You are asked to make a split-second decision to free an enemy, throwing him a sword to defend himself, or keeping him bound. The choice is not clear, as you are picking a side between two factions. In my first play session, I threw him the sword and spent the second act in a dwarven city. After completing the game, I tried the other choice. To my surprise, the plot branched into an entirely different human city and I didn’t see the dwarven city or plotlines at all. It was as if the developer had written two games complete with different settings and characters based on the split-second choice I made with the sword.

What I enjoyed most about the Witcher 2 is that it was a good story. The characters seemed real and my choices impacted them. Like life, the choices weren’t straight forward and the story continued on, weighted by the consequences of those choices.

A few years ago I saw a YouTube clip of Quantic Dream’s Heavy Rain. Designed for the Playstation, the game used the PS controller’s buttons and joysticks to execute actions at the right moment or select choices from a list of options.

The clips were both perplexing and intriguing. In one scene, you swished your joystick back and forth to do mundane things like brushing your teeth. In another, a character fights off an attacker in a high-rise apartment while the game camera swoops and cuts like something right out of a thriller movie scene, complete with movie-scene action music.

The mechanism was Quick Time Events (QTEs) - pressing the right button at the right time. QTEs have been around for a long time. 1983’s Dragon’s Lair was an animated laserdisc game (literally animated - it was a hand-drawn cartoon by Don Bluth) that played pre-recorded laserdisc animation segments requiring you to move the joystick or hit the sword/jump button at the right time. Succeed, and the animation continues. Fail, and there’s a brief stutter while the laserdisc loads up the fail animation, showing your hero coming to an end.

Detroit: Become Human is Quantic Dream’s 2018 interactive cinema release. Similar to Heavy Rain, it follows a handful of playable main characters through a story about androids revolting against their human creators. Sweeping cinematic music and camerawork right out of a blockbuster frame this for what it is: you are playing the main characters in a movie. All of the characters look like their well-known actor counterparts and are fully motion captured with facial mapping. When the camera zooms in on a troubled character who is thinking about what you just said, you can actually read his expressions and see the actor’s response. It’s one of the few games I’ve seen where the character’s faces emote the subtle body language cues we’re used to looking for as humans.

The game starts with a tense scene where you are an android hostage negotiator named Connor who arrives at a high-rise rooftop standoff. A family’s android has turned homicidal, killing the father and several responding cops, and now holds the daughter hostage at gunpoint at the edge of the roof.

Police helicopters and snipers add to the tension. Before you head out to talk, you gather as much info from the crime scene as possible to understand the android’s motivations. These scenes - where you investigate in a way only an android could by zooming in on details, forensically sampling clues by tasting them, and reconstructing events based on where bodies and bullet wounds are located - are great fun. But the real fun starts when you step out onto the roof. Did you find the slain policeman’s gun and take it with you out here, giving you gun options, or are you unarmed?

Will you treat the wounded cop bleeding on the ground despite the android’s threats to shoot you, or will you step over him? When I made my choices, the android decided to fling himself and the girl off the roof. As he started to move, the camera zooming in slow motion, matrix-style, I had the option of charging him because I’d chosen to steadily advance and I shoulder-checked him while pushing the girl back onto the roof, sending both me and the android over the edge. As the camera followed me down to my death, a slight smile pulled across my android face, and the words Mission Successful appeared. It seemed epic. It was a nice twist - sacrificing myself in the first scene but saving the girl - and it seemed like the scene was written to end that way.

Much to my surprise, there is no way the scene is supposed to end. In fact, this rooftop scene can end a dozen different ways with every permutation you can imagine. You can save the girl other ways without flinging yourself over the edge; you can survive but the girl can die, you and the girl can die, you can save the girl but still die in other ways. I think what’s particularly awesome about all of those options is that each is written with such care that it feels like the way the mission was supposed to end. When I chose another path that had Connor promise the the android he wouldn’t be hurt if he released the girl, only to have police sniper’s bullets rip the android apart in slow motion, the android looked betrayed, saying “You lied to me, Connor.” It equally felt epic and set the tone for Connor’s character. Here, Connor was a calculating machine doing what was necessary to save the girl. Similar to games like Star Wars: Knights of the Old Republic, where choices nudge you towards the light or dark side, an icon popped up indicating Connor had nudged more towards the machine side.

Connor is a joy to play. He has a Terminator-like focus on achieving his mission, and when he’s off chasing another android they both parkour through diverse obstacles and scenery in a Jason Bourne kind of way. He’s particularly fun if you play him on a journey to become more human, as you see these little glimmers of understanding when he makes the moral choice over the more direct mission-ending choice. He’s paired up with washed-out human cop Hank (played by the always excellent Clancy Brown), and their relationship is a mix of familiar buddy-cop tropes that works well. Hank of course doesn’t want an android partner, and winning him over is one path you can take.

Hank, played by Clancy Brown. If Connor truly becomes Hank’s friend, you will get this scene after the game’s credits roll.

Connor has the biggest character arc in the game, and that arc is entirely defined by you. Either he will become increasingly more feeling and human, turning into a genuine friend to Hank, or he will become increasing more calculating and cold, turning into the story’s villain.

The other main characters include Kara, a housekeeping android, and Marcus, a caretaker android. Kara witnesses domestic abuse between a father and his young daughter, with Kara fighting off the father and ending up on the run with the girl, Alice. Her early scenes, where Alice is freezing outside and Kara has no money as an android, needing to find a solution to keep Alice safe, are compelling. You have to chose between morally questionable actions such as stealing clothes, robbing a convenience store, or staying in questionable locations such as an abandoned car or boarded up house. Alice reacts to your choices. One way to get money is to have Alice distract the cashier at a store. Alice is mad at you for using her like that afterwards, but you now can sleep in the motel instead of the car or boarded up house. As an android on the run, Kara is soon pursued by Hank and Connor, and these scenes are really compelling because everyone involved is a good guy. You don’t want any of the characters to die in the conflict, but all of them can depending on your choices.

I think we’re used to video games where, if the situation is “save the child”, the game isn’t really going to kill the child if you fail. Not Detroit, though. Make the wrong choices and it will show you the terrible consequences. The game doesn’t spare you with a game over credit roll, either. The plot continues, the aftermath of the character’s death changing how the remaining events unfold. Because of this, it accomplishes something writers are familiar with: stakes. It’s really quite stressful, actually, when you become invested in characters and are constantly aware the game will kill them based on your poor decision making.

In my first play through, Kara and Alice are captured and rounded up into an android camp, where androids are systemically lined up and destroyed. The entire scene is awful to watch and play through. Alice’s terror is palpable and Kara’s despair, despite her trying to comfort Alice, is heavy. Yet, the choices I made had a parallel plot in play with Marcus leading an assault on the camps. As the scenes cut back and forth to Marcus’s forces shooting it out and advancing through the guards while Alice and Kara were headed into the disassembly room, I was riveted. It felt like this was the way it was meant to be. You can imagine my surprise when I discovered Kara and Alice didn’t need to be in the camp at all. Had I made better choices earlier, they could have slipped across the Canadian border and not been a part of the fighting. That entire gut-wrenching scene occurred because I tried to have Kara and Alice make a run for it during an earlier scene.

I should mention that the camp scene is an example of one of the criticisms of Detroit: Become Human. The main plot is about androids becoming self-aware and wanting to be treated equally, with the same rights and protections as humans. Fundamentally, it’s a civil rights movement, which tries to achieve its goals through peace or violence. The writing is quite heavy-handed with the real-world analogies, creating quite obvious segregation and concentration camp references. Connor and Markus are critical to the plot, since Connor is trying to stop the spread of android awakenings (“deviancy”) while Markus is causing it and leading the revolution. Although Kara’s story is compelling, it is incidental. She is simply an awakened android on the run who sometimes ends up at places where the plot is happening. Action movies have a long history of sexist tropes where men are heroes and women are there to be rescued or romanced, and unfortunately Kara and Alice exist to be in danger, chased and rescued. Kara is perhaps the most empathic android in the cast, emoting motherly love and concern for Alice, and is still a great character to play. I just wish that she had more of an arc and more importance in the story than to be abused by evil men. There is another prominent female character, North, who is Marcus’s second-in-command, but she defers to Marcus’s orders and falls into the trope of love interest, based on your choices. She is a key mover of the plot, however, and will take over command if you manage to get Marcus killed or kicked out of the resistance.

The other thing some reviewers complained about is tropes. Tropes are recurring situations or characters than writers continually use. Now, full disclosure: I use tropes in my writing. Really, everybody does. There’s a reason these situations are reused: readers like them. In my stories, Beckman is the tough, veteran security officer of few words. Nothing original about that. But, readers love Beckman. Detroit: Become Human is filled with tropes from dozens of sci-fi movies and books. An android cop partnered with a depressed, alcoholic human to hunt down deviant androids; a skyscraper caper with a base-jumping parachute escape at the top; two identical Connors both trying to convince Hank they’re the real Connor and that Hank should figure it out by asking them questions only the real Connor would know. But, here’s the thing - although I recognized the trope immediately, it was awesome to play it. When Hank started asking me questions to prove I was the real Connor, a clock ticking down for my answer, I found myself scrambling to remember what his dog’s name was. Yes! I thought, I’ve seen this scene a million times and always wondered how I would handle it. Even the way Connor says, “Wait! Ask me a question only the real Connor would know,” is said as if Connor were remembering it from a movie he’d seen. The solution to prove myself was based on choices I’d made earlier in the game. If you google this scene, you’ll find a dozen different ways it could play out.

I really loved this game, faults and all. I admit, as I’ve gotten older I’ve been less interested in button-mashing games and more interested in narrative experiences, and Detroit: Become Human was really like nothing I’ve played before. I’m going back and replaying scenes with different choices. From what I’ve seen on YouTube, the endings are wildly different based on choices you make, and I’m looking forward to exploring each one.