Rebecca Brewster Stevenson's Blog: Small Hours, page 7

October 26, 2016

The Absence of Precise Answers

My family and I attended a play last night: Arthur Miller’s The Crucible at PlayMakers Theater.

It’s difficult to say that this is a wonderful play, or even, perhaps, a good one. You don’t witness a drama about false accusations, terrible lies, and gross injustice and feel good about it afterward.

Cast of The Crucible, photo by Jon Gardiner

Cast of The Crucible, photo by Jon GardinerWhich isn’t to say that the play doesn’t resolve. It certainly resolves–but perhaps not in the way you might wish it would. It doesn’t resolve with the wicked getting their just desserts. And whether or not you believe in wickedness, it’s a thought that occurs to you when you’re watching this drama unfold. Miller understood the human condition: that gnawing need we have to find reasons for things, the desire for security and esteem, the terrible but nearly irresistible tendency to look for fault in those we envy or, with undue cause, hate.

It is an excellent play, creating and sustaining tension wrought by characters acutely themselves: as in real life, they play their part the only way they can, hemmed in by belief and experience and desire. The maddening part comes when no one will listen to sense, when the light of reason and bald fact glance away instead of making impact. Along with the rest of the audience, we sat pinned to our seats, impotently armed with the truth, and watched a small society devolve into chaos.

actress Allison Altman, photo by Jon Gardiner

actress Allison Altman, photo by Jon Gardiner ***

When I entered high school, I found myself in the honors English program. I didn’t really know what that meant, but it was soon enough defined for me by lots of writing and reading text after sorry text. To a title, they were depressing: books and plays and short stories about nuclear disaster, dystopia, heroes failing miserably just before they hit their mark. I made bold to ask my 10th grade teacher why, exactly, this was inflicted on us. Why all the unhappiness, I wanted to know.

Her answer was a wise one about tragedy showing us the dignity of humankind, of life. Most comedies, she pointed out, ultimately ridiculed the human condition. But a tragedy asks us to look our failings in the face, to reckon with them, to provoke questions about ourselves, our societies, even our world.

We read both Arthur Miller’s The Crucible and Death of a Salesman in 11th grade. Excellent, worthy texts.

***

One month and a few weeks since my book’s release, I’m finding myself in an interesting place. More people than I can count have asked the same question: why couldn’t the story have ended like this? They propose the same small turn of the plot, and it’s an exceedingly comforting one–one that, in all the time I wrestled the story into place, I never for a moment considered. The story goes the way it goes. It could never go a different way. Were it to have gone the way they propose, then Maddie would be a different person.

Which is true–with certain decisions, certain moments–for all of us.

***

Actors Ariel Shafir, Sarita Ocon, photo by Jon Gardiner

Actors Ariel Shafir, Sarita Ocon, photo by Jon GardinerMiller’s John Proctor has a decision to make at the end of The Crucible. His entire life is staked on it. And in making the choice Proctor does, Miller turns the play out to his audience: he asks a question of all of us.

The questions that tragedy asks are the unhappy ones. On a good day, they make us shift in our seats; on a bad one–with the most excellent of stories, perhaps–they set us thinking hard. They release us to a cold October night with churning minds. They humble us. They set us back on our heels, in our place as people with finite time and limited agency, who had best make the most of both.

***

A recent reader of my novel asked the same question so many have asked: “Why couldn’t….?” She already understood the answer and as good as gave it with the question. But she also expressed what I was feeling in the 9th grade, in 10th: the discomfort of our frailty as humans, as finite lives. She wanted the happiest possible outcome.

Don’t we all?

She wrote, “I would have let Beth March live, too. And Bambi’s mom.”

I also would have liked that.

The job is to ask questions–and to ask them as inexorably as I can. And to face the absence of precise answers with a certain humility.

-Arthur Miller

September 17, 2016

Morning Drop-Off

I drove the girls to school on Thursday, a late-summer, light-filled morning. It was just the third week of school, day thirteen if we’re keeping count, which might not be a good idea.

The conversation en route was cheerful. Chatter about driver’s ed, gladness that it was already Thursday, and the painted parking spots in the senior lot. Would they vie for a spot when they are seniors, and Katherine’s someday first car being a motor home. They did not talk about classmates, about other students, although the conversation sometimes goes this way. Because what is high school–around coursework and extracurricular everything– but a time in close proximity to people who are and are not like you, the joys and challenges this brings?

The girls’ school sits in a beautiful block of our city, one whose approach is filled with small and charming houses, sidewalks, tall trees. The school itself is a sprawling, seven-building affair, lined with trees but leaving little room for lawn, except in front of the middle school. On Thursday morning, I saw and heard something I’d never noticed before: that lawn filled with students literally at play.

I was, of course, driving. The car-line and commuter traffic is considerable here. I couldn’t pay close attention to these middle-schoolers on the lawn. But Katherine explained that this was a privilege granted to students who maintained grades to a certain standard, and by evidence of their apparent enjoyment, this seemed a worthwhile reward.

I tried to watch them–impossible–as I drove past. What they were busy at, if everyone was included. Who was engaged, how they were playing. And if anyone–isn’t there always someone who does?–stood or sat alone.

If I look for the source of this impulse, probable causes assert themselves one after the other. When I taught school–so recently, so long ago–I made it my business to like every one of my students. Because we learn better, don’t we?, from the people who earnestly like us for who we are. When I think of my own children at school–long ago or now–and the pain I feel at their potential isolation. When I think of seventh grade and how I hoped to have someone to sit with at lunch. Or when I hear (rare, once?) the story from my father, brilliant but not athletic as a child, who stood against the brick wall of his school during gym class, enduring.

I tried to get a clear look at the middle schoolers, but they moved like leaves blown over the lawn, and I didn’t know any of them.

Thursday morning was beautiful. The morning light slanted in its warm way through the buildings and the trees. I pulled up to the drop-off point, and like a fool I said to the girls as they got out of the car that every one of them is precious. All the students in the school are precious, I said, even the one who makes you cry in math. Because on the second day of school this year a boy in someone’s math class made her cry. We are not naming names.

The girls are not sure they agree with me when it comes to who is precious and who isn’t, and they said so as they hurried out of the car, pulling their backpacks behind them, slamming the doors.

I proceeded, slowly, through the line.

It was September. It is still September, and it’s not fall yet, not quite autumn if you’re going by the calendar that marks the solstice and equinox. When I was teaching and the school calendar all too soon eclipsed what was left of summer, I insisted on the equinox, if only to myself, and that fall didn’t arrive until September 21st.

It goes too fast: this life, these days. Unless you are in high school. Or middle school, which may be worse.

It was still summer on that warm Thursday morning, as I proceeded in the burnished morning light through the car lines. The trees were still green: the decorative pear by the high school’s front entrance, the crepe myrtle in bloom.

Then I drove under the live oaks. A wind gusted, and leaves like amber blades spun down and cut the air. Emma and Katherine were out of the car; they had gone their separate ways, but for a few moments still in the car line, I was driving next to Emma and watching her in my way. She did not look at me, already focused on the day ahead, already at school. But I watched her as I slowly pulled past, saw her beautiful blonde hair and watched as she was enveloped into the school.

September 12, 2016

Birth Day

I always tell my pregnant friends to make plans on their due-dates. “Make sure you have something to do,” I say, because most babies aren’t born on their due dates, and by the time one is at the end of her pregnancy, a due date can feel like a bull’s eye on the calendar, fixed with Every Hope.

I carried more water-weight than Lake Erie at the end of my first pregnancy, and I remember wielding that considerable girth down a sidewalk in mid August, and I recall that a well-meaning passer-by asked, “When are you due?”

I said–only honest, “Today.” The beautiful boy didn’t make his appearance for another week. Which was fine. It has worked out fine.

A due date is an educated guess, a shot in the dark, a single box selected from the calendar grid. Meanwhile, labors and deliveries most often hang on the mystery of hormones… or something. I’ve heard it said that not even doctors understand fully what exactly triggers it.

Make plans.

Tomorrow is a due date for me, too, albeit a more certain one. It was selected by my publisher last (2015) July, right after I signed my contract. It was chosen for reasons I didn’t quite understand at the time, but my editor said it would allow time for editing and also for about six months of marketing.

And it gave me Time–something I didn’t realize at all that I would be needing.

At the time, last July, signing the contract to publish the novel I had been working on since time out of mind, I was eager to get it Out There. I thought all it needed would be a glance or two by a generous eye. I had already crafted and re-crafted it, and I’m an edit-as-I-go kind of writer: I can’t let an error wait for later, and I test the rhythm of my sentences even as I’m churning them out. I return compulsively to paragraphs to correct redundancies. I write with dictionary and thesaurus in hand, so to speak.

Surely this book wouldn’t need more than a year before it was Out There.

But it wasn’t long, working with my editor, before I realized that this book of mine Needed Help. It wasn’t just a good idea–it was Absolutely Necessary that the story be kept in the quiet shelter of some shared files for a while. We decided that the edits needed to be finished in January, and suddenly the time that had seemed too long couldn’t be long enough. I sat for hours with laptop and drafts, trying to work through and smooth out and figure out the presenting problems of this book. In all the time I spent writing this novel, the last hours of editing were decidedly the hardest.

And then they were done.

After which the waiting really began, because covers had to be designed and promotions had to be sought, and I sincerely thanked my publishers more times than I could count for all the expertise they had on all of these things that I couldn’t possibly begin to guess at.

And then there was the book.

But even then it wasn’t time to get it Out There, because the real promotion had only just begun. So there were trips to Chicago and Orlando, and all kinds of meeting people who might possibly (we hoped) decide to give Maddie a read. And every time, with every conversation, with every title page insribed, I thought about that book carried away from me in the hands of a stranger, and I knew without saying so that just a little piece of me had walked away with it.

Maybe that’s when it began to feel–back there in the months of May and June–that it was actually a very good thing that the book wouldn’t be Out There for a while, that I would be more than happy to wait until September–until mid-September, actually–for people to start reading this book in earnest.

There have been some Incredibly Helpful moments along the way. At the end of June, Kirkus Reviews amazed us all with a glorious (and glowing) review. There has been nothing like that moment–in all of this process–sitting high above Orlando in my hotel room and reading those words: “Most powerfully, Stevenson links the spiritual to the physical…letting love for the mortal body open space for love of the divine.”

And there was the conversation, just over a week ago now, with a literature-professor friend who asked the very questions I had hoped the book would provoke and then some. We talked for an hour but it felt like minutes, because the ideas and methods and elements he explored in the novel were the things that had fascinated and held me, that had compelled me to lose sleep and sit silent for hours, to give up–senselessly, it sometimes seemed–an otherwise vibrant life to fill page after empty page.

And then there was Amazon, enormous warehouse and distributor that it is, who decided (because what else is one to do with books-in-stock?) to ship Maddie–without warning more than a month before she was set to go.

Suddenly there I was, due date circled in red, a bull’s-eye in mid-September, delivering this baby about six weeks premature.

Except that I wasn’t delivering it. Amazon was. “It’s as if,” I said to my husband, “I went to the hospital for labor and delivery, only to be told that my baby was already down the hall.”

So much for due dates.

That was a tricky week. So many people happy to get their book in a surprise and early delivery, and I felt like I had lost something–my footing, perhaps, the proverbial rug pulled out from under and I’m sprawled somewhere down the hall. It wasn’t a huge deal; it was decidedly a first-world problem, but there was something about the unanticipated exposure that I wasn’t at all prepared for.

I think that anyone who makes art might understand what I mean. If you make art, then it’s likely you’re passionate about it. It’s probable you believe in it with all–or nearly all–that you are. It’s an expensive thing, in its way, to make art. It costs. My editor said it about this book, and in truth, her words help me to understand how I feel about it: “It’s one of the most beautiful, brave books I’ve ever read,” she says.

Well, I hope it’s beautiful, and I do think it might be. But I’m pretty sure it’s brave–because it terrifies me. When it comes to making art, there’s a white-knuckled, deep-breath sort of moment before the curtain rises, before the doors open, or before the book is chosen from the shelf.

And I missed it. Like all three of my human babies, this baby didn’t come on her due-date.

Which is fine. It has worked out fine.

Because a glorious gift of this early release–a gift bestowed unwittingly by Amazon–has been the joy of the early readers. I’m sure I haven’t heard from everyone who has read it, but time and again I am learning that that people love her, that they “get” her, that this is a book that will stay with them.

I am delighted.

What more does a parent, an artist, a writer want than to know than that her child will thrive in the world? Will be, moreover, a blessing to others? What more, indeed?

It makes one want to celebrate. Which I will do. On September 13th. On Maddie‘s second Birth Day.

August 12, 2016

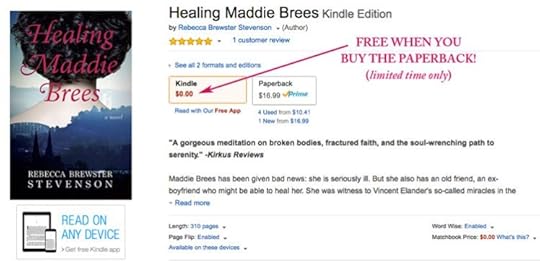

BOGO on Healing Maddie Brees

Amazon is promoting Healing Maddie Brees by giving away a FREE KINDLE COPY of the book to anybody who bought a paperback copy! You can take advantage of this even if you bought or pre-ordered the book long ago.

If you don’t have a Kindle, you can read it on the Kindle app for iPhone and Android, and if you don’t have one of those, you can have it delivered to the Kindle Cloud Reader.

In any case, ordering the Kindle Copy helps Maddie‘s rankings, and it’s absolutely FREE. So if you have a minute, consider using that minute for Maddie.

To take advantage of deal, follow these simple steps:

1. Go to Amazon and buy the paperback book. (Skip this step and proceed to step 2 if you’ve already done this… by the way, THANK YOU!).

2. Now go back to Amazon and search for the Kindle edition. (Note that if you don’t actually select “Kindle edition” on the listing; the price will show up as $7.49. However, when you click on that box it changes to $0.00. Why? I don’t know.)

3. Order that Kindle edition and get it for FREE. And simultaneously, simply, miraculously, give Healing Maddie Brees a boost!

Thank you so much.

July 20, 2016

Carry-On

I feel as if I’ve done a lot of traveling lately. It’s that time of year, right? Summer vacation. We’re gone, we’re here, we’re gone again.

Definitely not complaining. I love to travel. But lately it’s got me thinking about how I pack.

Like most people (everyone?), I’m guessing I have the normal categories: clothes, toiletries, shoes. Standard, right? That’s standard.

But when it comes to packing, what really matters to me is the Carry-On.

You know the Carry-On. That’s the smallish bag you keep with you on the plane, the one you squeeze into the space under the seat in front of you. The one that holds your wallet and your chapstick, maybe your toothbrush (depending), and anything else you’ll be wanting to grab during the flight.

So the Carry-On is vital. But for me, it’s not just for planes (do you do this, too?). It’s for car-travel. And even though we don’t have to wedge it under the seat in front of us, it’s what my daughter and I have come to call it even for travel in the car. We always pack a Carry-On.

In a way, the Carry-On is the Most Important Luggage of my trip. Because while I consider the clothing, shoes, etc. to be necessary, the Carry-On sort of contains (this sounds so ridiculous) all my hopes and dreams.

Okay, granted. That definitely sounds over the top. Bear with me.

The Carry-On represents, firstly, that 1) I’m going to be away from the normal demands of my life for awhile, and 2) I’m going to Sit.

Sitting is not a normal thing for me. Even if I’m writing, I try to spend much of the time on my feet. Sitting isn’t terribly good for you; and also, I manage a household. On any given day, I am up and about Doing Things, and I am doing these things Most of the Time. Most of what I do, on any given day, does not find me doing the sorts of things that one can find in my Carry-On.

As such, my Carry-On usually contains things I Should Get To. Blank paper and envelopes for notes I need to write, a bill I need to take care of. The general flotsam of my desk, culled and reorganized (or not) into a doable, smallish stack suitable for the road.

And it contains the Dailies. My Bible, my journal. Whatever it is I’m reading at the time. My laptop and its power cord. A phone charger. The Things I Need to Do My Job(s). (Writer. Mother. Wife. Person.)

Then finally (here is where the Hopes and Dreams come in), it holds a representation of the Things I Would Like To Do. As in, if I had All the Time in the World. Which one basically does (or can imagine one does, anyway) if one is flying to Shanghai. Or riding as passenger around New York City. Or anywhere at any time ever on I-95 near Washington D.C.

Hopes and Dreams are really hard to get to, but maybe if one simply had Enough Time….

Take the trip I’ve just returned from. We were gone for exactly one week, and my Carry-On for the ride in the car to and in and from New England included the following: my journal, Bible, Psalter, notebook. Issue # 37 of Ruminate magazine and the July-August issue of Smithsonian. My mother’s journal (not my mother’s journal, but the journal I keep and write in about being a mother). My laptop, its charger. A blank thank-you note; a Compassion International letter. A new book of poetry written by Christopher Janke; a creative non-fiction book, Wake, Sleeper, by Bryan Parys. Andy Crouch’s Culture-Making. A copy of my novel (can’t quite say why) and the wonderful sci-fi, literary fiction brilliance that I’ve read once before but am So Glad to have re-read on this trip: P.D. James’ Children of Men.

That’s for one week, Saturday to Saturday.

Listing it out like this (or looking at it in its bulging bag, or swinging it over my shoulder to tote to the car) makes me feel a little bit silly. Do I truly imagine that I’ll get to it all?

And yet. It’s an interesting thing to distill it like this. To pack into a discreet container The Things One Really Loves and Hopes To Do.

This is where the moral goes, right? The application. The metaphorical point to all of this.

Truth be told, I don’t really know what to say. I could ask in a tone tinged by a Capital One advertising campaign: “What’s in your carry-on?” Or I could encourage young mothers who don’t currently have time or room for carry-ons of their own that they might, someday, have carry-ons in their futures.

Or I could comment on the truth: that we got home on Saturday night and most of the laundry was done by Sunday, but I didn’t fully unpack my carry-on until Monday night. Or was it Tuesday? Because, for the most part, I wasn’t using any of it.

In which case the point would be how hard it is, in this life, to make time for what I love. For what we love.

And that maybe it’s vital to do so.

“Such things, I grant you, have nothing of virtue in them; but there is a sort of innocence and humility and self-forgetfulness about them,” says Screwtape to his nephew Wormwood in C.S. Lewis’s The Screwtape Letters. As such, this notorious demon suggests, delights and joys are dangerous because they very well might–horrors!–lead us to God.

I love this very much.

What is it with God and delight? What is it with Him and pleasure? The more I look for Him, the more I see Him appealing to me with precisely this: the things that truly delight me; the things I most desire (Psalm 37:4).

No matter how hard omni-media try portray Him as Kill-Joy; no matter how the Commandments are preached as prescribed misery, I have learned and am learning that the opposite is the case: that the One who declared this world Good is also the author of delight.

That yes, He has rules and laws, but these, too, when followed, are actually meant to be life-giving. To delight us.

That He Himself is actually the greatest delight we can know, and all the other delights of this world–like a cold beer, the soft fuzz of a newborn’s hair, sunlight limning a cloud or the stunning beauties of a well-crafted phrase–are the edges of the beauties of Himself.

Which amazes me.

And also makes me hope (Oh! here’s the point!) that you always pack a Carry-On. That you don’t leave it untouched at the foot of the stairs, but that you dip into it often and are repeatedly delighted. And that you find Him also (somehow) tucked miraculously inside.

July 14, 2016

259,000 Miles of Them

We are in New England for the week, staying on a farm in a quiet corner of Rhode Island. It’s beautiful here–because it’s New England, because it’s green and wooded, because it’s about ten degrees cooler than any July at home.

Of course we want New England to look as it *should,* and Rhode Island does not disappoint: the stone walls are everywhere. Gorgeous, rambling, antique lines of them. They appear along the sides of the roads, a sudden demarcation between roadside and woods or farmland, the edge of someone’s lawn. Or they spill out of the woods, and if you look quick enough as the car goes by you can see them extending away from you, dividing the trees. They trace the topography of a hillside, they mark the undulating line of the ground.

Stone walls are what New England is supposed to have, like clapboard, and shutters, and steeply pitched roofs. Here in New England, stone walls are–to borrow the overused word–“appropriate.”

Something there is that doesn’t love a wall, that wants it down.

Robert Frost, a 20th century New England poet, won four Pulitzer Prizes for his work and was the inaugural poet for President Kennedy in 1961. He was born in San Francisco and later had a winter home in Florida, but for the most part, he spent his life in New England: New Hampshire, Vermont, Massachusetts.

For a long time, he farmed (unsuccessfully) in New Hampshire. He knew a thing or two about stone walls.

Something there is that doesn’t love a wall,

That sends the frozen-ground-swell under it,

And spills the upper boulders in the sun;

And makes gaps even two can pass abreast.

These walls are ubiquitous in New England. There must be miles and miles of them. Bill and I have wondered aloud about them as we drive. We guess a wall is just the thing to do with the stones. The soil here must be rife with them.

And certainly, in addition to the stone walls that trace the landscape, the ground here is forever exposing large slabs of rock, huge outcroppings that one can only assume might be the tip of a proverbial iceberg. Bill and I imagine making a life from the soil here, tilling the earth with our rudimentary, colonial tools and finding–again and again and again–a rock and yet another rock to prize from the ground.

Fruitless, tiresome, unintended crop.

In 1939 the mining engineer Oliver Bowles estimated that there were probably more than 259,000 miles of stone walls in the northeastern U.S., most of which is in New England. Many walls have since been destroyed, but probably more than half of these remain. –Connecticut State Museum of Natural History.

It was the glaciers that started it, eons ago, sliding slowly southward over what would eventually become New England. The glaciers themselves were apparently full of stones, the hardest of which–granite, gneiss, limestone–survived the grinding journey locked in ice. As the glaciers melted, they deposited the stone in the ground.

Hence, so many stones. A real hassle for sowing crops, but perfect for building a wall. Walls. 259,000 miles of them.

The tenacity of these walls is impressive: no adhesive was used in their construction; each wall is a balancing act, stones supporting stones. Most of the walls were built between 1775 and 1850, and yet here they stand today.

Nonetheless, “Mending Wall” is a poem about the process of repairing the holes in one of these walls. Apparently, they had their periodic ruptures, their sudden and inexplicable “gaps.”

No one has seen them made or heard them made,

But at spring mending-time we find them there.

I let my neighbor know beyond the hill;

And on a day we meet to walk the line

And set the wall between us once again.

Frost questions the process. His is a 20th-century sensibility: Why should we bother repairing the wall? Do we need the wall in the first place?

Well, but all farms have fences, right? We need something to mark the edges. It’s difficult to imagine now, but I’m told that when the original farmers had cleared the land here, trees soon became scarce. It was sensible, if not incredibly labor-intensive, to use the natural resource of stone to form animal pounds or fencing, to outline the boundary between one and one’s neighbor.

If you on your farm have cows, say, and I have apple trees, I’ll want to prevent your cows coming over to my property and decimating my bumper crop of apples.

Solution: stone walls.

And yet,

There where it is we do not need the wall:

He is all pine and I am apple orchard.

My apple trees will never get across

And eat the cones under his pines, I tell him.

He only says, ‘Good fences make good neighbors.’

And here begins Frost’s metaphor. Or mine.

What is it about a wall that makes us feel safe? Here in the 21st century? I’m not talking about actual, physical boundaries. I know enough from movies and the news–don’t we all?–about technologies used in heist or warfare. The jig is up: something (someone) somewhere will always be able to get through.

No, I’m talking about those other walls, the ones each of us constructs, the separations, the divisions that, somehow, make me imagine I’m safe.

Before I built a wall I’d ask to know

What I was walling in or walling out,

And to whom I was like to give offense.

Something there is that doesn’t love a wall,

That wants it down.

The news these days in this country is rightly all about these walls. But we’ve found they are not, after all, unique to New England. They are everywhere. They seem to cross every region, state, heart, and are (and have been) more visible to some of us than others.

But the walls–even the ancient, “wild walls,” so long untouched that they have become their own vibrant ecosystems–didn’t arrive of their own accord. They didn’t emerge from the ground in tidy rows, vestigial trace of a glacier’s wake.

No. The walls come from stone farmed, mined, balanced, planted. I can’t help but think–studying them, even my own–that these walls are cultivated. They are the product of rehearsed anger, of practiced bitterness, the insistence *not* to forgive. And while we rightly find them most grievously offensive in shootings in Louisiana, Minnesota, Orlando, Dallas, I believe they have their origins in the smallest places: in every prideful thought, every smug estimation of our superiority.

Any time we ever imagine–even for an instant–that we are better than someone else.

…many farmers would find that their farmland would have many stones on it that weren’t there previously…. When a farm is plowed, it causes layers of soil beneath the surface to push up their rocks from different soil layers to another…Many farmers would have to remove the rocks on their farm if they wanted to plow it again, only to find that they would have to repeat the process of removing stones. -Corey Schweizer

I think everyone’s field is full of stones. Everyone’s. It’s the human condition. And just when we think we’ve got our soil cleared, we’re unearthing more: more selfishness, more hard-heartedness, the chronic tendency to love ourselves more than our neighbors, to be willfully blind to another’s experience, hurt, need, goodness, worth.

I see him there

Bringing a stone grasped firmly by the top

In each hand, like an old stone-savage armed.

He moves in darkness as it seems to me

Not only of woods and his father’s trees.

We do this, as a society, on a large scale. And we do it personally, too. Daily. Minute by minute.

We are–to a person–rocky soil, laden with the deposits of that long-gone glacier, burdened with its mineral waste. Being alive means tilling that soil, making a place to sow good seeds, and pulling up rocks in that effort.

It’s ours to decide what to do with the stones.

I will give you a new heart and put a new spirit in you; I will remove from you your heart of stone and give you a heart of flesh. -Ezekiel 36: 26.

July 7, 2016

M is for Mutiny. And Merriam-Webster.

Here’s a relatively new delight in my life: Any and every time I type the letter “m” into the Internet search bar on my computer screen, “Merriam-Webster.com” appears. Instantaneously.

(I know what you’re thinking: That delights you? That? To which I respond: Yes. That. And I realize it’s a relatively small thing on the epically large scale of Potential Delights, but I think it’s a good practice to recognize them all. Don’t you?)

The voluntary appearance of “Merriam-Webster.com” in my Internet search bar seems to be a new thing, but perhaps I’m only just now noticing it. In any event, it is wonderful for many reasons, some of which are as follows:

I immediately think of my sister.

I immediately think of words.

I remember that there are websites in the world devoted to words, not least of which is Merriam-Webster.com.

I am reminded that oodles of people enjoy words and are interested in them, a fact which has given rise to the alluded to (and directly named) websites.

I recall–no matter what I am currently doing–that I have many, many times required the Most Excellent Services of Merriam-Webster.com, which makes me think of writing and what I get to do when I am working, and I am filled to the gills with gratitude.

So, yes, typing “m” into my Internet search bar–even when I am looking up something so pedestrian as “money” (not that I’ve done that) or “monterey jack” has become–if only momentarily–a delightful experience.

Often as not, though, I’m using Merriam-Webster on my phone. Sitting in the library for hours on end, typing away on my novel, I avoided opening the entire Merriam-Webster website (word-distractions galore!) and instead kept the app open on my phone.

That’s right. You read that correctly. There’s a Merriam-Webster app.

(Go! Quick! Run! Hie you to your phone and download it! Worlds and worlds of word-wisdom at your fingertips!)

I made use of it this very morning, in fact. Bill, Will and I were sitting together, enjoying our morning coffee, and somehow (I forget how) the word “mutiny” entered the conversation.

“Mutiny,” said Bill. “Now there’s a weird verb.”

Indeed, I thought. What an odd verb! It sounds very much like a noun to me.

We had been sitting together for the better part of a half-hour at this juncture, and I am pleased to be able (honestly) to say that not a one of us had, as yet, made use of our phones (well, except Bill, who’d had to answer a business call). But of course, immediately Will looked the word up, and the very first part of the definition gave its part of speech away: “rebellion.”

That there’s a noun. It’s an act, which is, in its way, a thing. Which makes it a noun.

But this was inadequate for me, because I knew that Bill was right. Is right. “Mutiny” is also a verb.

I wanted clarity on this, and it was the Merriam-Webster app to the rescue.

Here’s what happened. I began typing in “mutiny” at the prompt, and Merriam-Webster (always so willing help) began offering me options. And “mutiny” was the not the first, but rather a word that looked familiar but that was not, in fact, what I was looking for but which was, in truth, what I wanted.

“Mutine.”

Suspicious, I selected it. And here we are:

mu-tine \’myu-ten\ verb instransitive verb obsolete: rebel, mutiny

Origin: Middle French (se) mutiner.

First use: 1555

So. “Mutiny” was not the original noun but rather a French word. A verb.

“Boy,” I said to Bill and Will, “I bet that drove somebody crazy.” And they both laughed at me because they knew that, had I been around when the noun “mutiny” began to be used as a verb, I would have been the one trying to correct everybody.

“No, no!” I would have shouted, hanging from the ship’s rigging, say, or clinging to a deck-rail, “It’s not mutiny! That’s a noun! You mean mutine! MUTINE!” Trying to make myself and my correct French pronunciation heard over the roar of the waves and the clamor of pirates. Or sailors. Or whatever mutinous lot you’re envisioning here.

It’s a tired yet familiar position for me, less fraught than the one I’ve sketched above, but fraught nonetheless.

My resident position, when teaching, as Defender of the Common Tongue: “No. It’s not ‘verse,’ as in ‘Athens verse Sparta.’ It’s ‘versus.’ ‘VERSUS.'”

My unspoken, secondary job when mothering, as Corrector of all Grammatical Failings: “No. It’s not ‘laying on the couch.’ It’s ‘lying.’ ‘LYING.’”

My decidedly ruffled impotence, sitting in the church auditorium or reading posts on Facebook, as Would You Please Just Listen to Yourselves Authoritarian: “No. It’s not ‘everyone that.’ It’s ‘everyone who. EVERYONE WHO.'”

I exhaust myself. And everyone else, I fear. All for the love of language.

Ah, but Merriam-Webster, once again, to the rescue. Because the dictionary understands. It gets it. In its relentless and inexhaustible efforts to catalog, inventory, and update the uses and meanings of words (and the words themselves), they are quick to track the changes–the inevitable alterations–undergone by the living language that is English.*

Which is why (did you see it?) in the definition above, they will tell you how a word is currently used. Sometimes, when the use is old-fashioned, they will label it “archaic.” And sometimes, as in “mutine,” the word is labeled downright “obsolete.”

See? Merriam-Webster is So Incredibly Helpful.

It’s fools like myself, dictionary in hand and clinging nonetheless to a water-washed deck-railing, who insist on things like “versus.”

Still–and despite the occasional (and so necessary) correction I receive at their hands–Merriam-Webster.com is sweet companionship. If possible, and this is evident based on their time-commitment alone, they love language even more than I do.

I love to be reminded of this. And I am reminded, every single time I enter “m” at my search bar prompt. Thank you, Merriam-Webster.

*It is this practice, among others, which–to my mind–distinguishes Merriam-Webster as better than their often-praised peer, the Oxford English Dictionary. The Merriam-Webster dictionary is consistently researched and re-researched, edited and updated. This is not true of Oxford. Sorry, but there you are.

July 3, 2016

Inspiration, Discipline, Determination–and a Whole Lot of Help

The difference between these two books? The one on the left is a review copy, replete with typos. The one on the right is the REAL DEAL. We’re getting close now!

The difference between these two books? The one on the left is a review copy, replete with typos. The one on the right is the REAL DEAL. We’re getting close now!It feels like only weeks ago I was sitting at my little table in the public library. Biography section on the left, self-help on the right, and me at my table in the middle because here was a bright space with a window. I sat there almost every Monday morning for a span of three or so hours, and I did this for the better part of three years.

Ahead of me were floor-to-ceiling windows looking out on a patch of lawn and a little bench for sitting. And only a few steps beyond that was the woods full of trees, deciduous and otherwise.

The woods were a fine distraction, rain or shine. Most trees look beautiful in any weather. But there was no door giving me immediate access to them, so there was nothing for it but to sit at my table, laptop waiting, and admire.

More accessible was the alcove on this side of the plate glass, the one with the comfortable chairs and ottoman. The magazine subscription section flanks that alcove, and it beckoned with all manner of photograph and slick-paper distraction. But I never gave in to that.

I did repeatedly read the spines of the books around me. I read them blindly, I think (if there is such a thing), because I can now remember none of the titles. But there they were, week after week, staring back at me.

Maybe this is what it takes to finish writing a book? A little Inspiration, a little Discipline.

But by far the most important were the books–because they were all finished. Their authors had completed them. No matter how many days, weeks, and months of focused, silent sitting, the represented authors had eventually reached The End.

So here’s to Determination: If they did it, I could do it, too.

It’s been more than a year since one of those Mondays, a fact I find very difficult to believe. It’s been almost a year since I signed a contract with my publisher, nearly six months since I mailed in the last edits.

Within the last month, I sent in the list of errors I found in the review copy, and about a week ago I got my hands on a polished edition (above), clean of all those random errors–including the alarming sentence in the last paragraph on page 58, which read exactly as follows: “l.”

I have no explanation for this, and I am so glad it’s gone.

And four days ago, I polished up that vital paragraph at the end of the book, the one that reads “Acknowledgments.” It’s over now; it’s finished.

I did it.

This is still somewhat unbelievable to me. How long does it take, I wonder, to adjust from dream-work-hope to reality? Human beings, I’ve found, are complex creatures, and some of us transition more readily than others.

In my defense, the reality of having finished a book is not quite yet a reality. Healing Maddie Brees is in the hands of select reviewers and is, otherwise, not yet in circulation. I have a little over two months left before the book is *out there,* so to speak, before the conversation I’ve been wanting to have can be had because people have read her.

Still.

A week ago, I was offered a peek into what the conversation might be: last Saturday, Kirkus Reviews let me and my publisher know what they thought of the book, and on Thursday I was allowed to share it with the world.

I was and I remain overjoyed and so grateful. Grateful that they chose to review it (in this business, decision to review or not is entirely up to the reviewer). Grateful that they like it. Grateful that they find it beautiful. Grateful that the conversation I am wanting to have might, in fact, be a conversation this book will engender.

And so grateful that those silent hours, pent up at my table in the library, have produced this book.

Now Healing Maddie Brees has ten weeks and three days before she can “go outside.” On September 13, she will be released from bookstores and Amazon, finally available to be read. That’s seventy-three days.

I’ve learned a lot about publishing books in the past year. One year ago, I knew nothing but inspiration, discipline, and determination, the story in my head pitted against the blankness of my laptop’s screen.

I had no idea–beyond writing it–what effort, wisdom, experience and help is needed to really launch a book into the world. My editor and publisher have been nothing short of astounding in getting Healing Maddie Brees where she is now: toes at the threshold, almost ready to go.

I’m so grateful for this, too.

If you are interested, if you would like (and if you haven’t already), here is something you can do to help out:

take a Pledge-to-Buy. See the tab on this website for how and why this works. I currently have 298 pledges. If and when I reach 500, we will choose ten pledgers (that’s a thing) to receive a free iBook of the novel.

June 22, 2016

You Coming?

“I only have six more months to be a kid,” he said. Out of the blue, just standing there in the living room.

What was I doing? Passing through, I suppose, on my way to the next busy-ness, the way it usually goes with me. But I was arrested by the question, and then made a mental calculation: was it six months until his graduation from high school? No, that’s almost (still) a year away.

“How do you feel about that?” he asked.

And then I got it. Six months (nearly) until his birthday. That’s what he meant. He will be eighteen. An adult. No longer a kid.

“How do you feel about that?” he had asked me, and of course it merited answer.

***

There is a right answer to these sorts of questions, I think. Parenting has taught me this much. There’s often an obvious, honest answer–but that doesn’t make it the right one.

For instance, there was the infamous time we were driving somewhere with three children in tow and William, age five, piped up with this doozy: “Daddy, are you going to die someday?”

Not likely a search for existential truths. Not a query demanding statistical probability. Maybe just looking for reassurance.

Bill’s answer: “Sure! I could die anytime!”

It was an honest answer and, to Bill, it was obvious. But maybe not best. Maybe not the right answer, given the circumstances: the age and person of the boy in the backseat.

As with Everett, fifteen years later, standing with me in the living room.

“I only have six more months to be a kid. How do you feel about that?”

***

When I was a girl, I think I imagined that motherhood would magically transform me. I believed I would somehow cease to be a person with her concomitant fears and insecurities, and somehow become a Mother–which meant I would be fully responsible, confident, capable–and also void of personal interest.

This probably says a lot about my mother’s selfless love for me, but it prepared me not at all for the reality, which is that a mother is a person.

And this is pretty much true all of the time.

***

Of course the learning curve, in a very practical way and in most cases, is steep and sure at the beginning. At the beginning, a mother is on demand basically All of the Time. Feeding, changing, feeding again. Trying to coax a little body into sleep.

I remember an afternoon when William was just two weeks old. Bill was at work, my parents had just left, and the newborn in my arms was wailing away at the top of his lungs. I was crying, too–until I realized that probably one of us should stop crying just, you know, to be on top of things. And the one to stop crying was going to have to be me.

So I couldn’t quite be a person in that moment. Not, anyway, the person I wanted to be–or felt like being, anyway.

But things even out soon enough. The challenging terrain of those earliest days gives way, invisibly, incrementally, to a hands-on parenting that contends with new necessaries: 3-square meals and bedtimes, “use your words” and swimming lessons. You’re doing so much for them, needed so much by them, that it truly becomes second nature. Schlepping them, signing forms for them, buying them (endless need) new pairs of shoes.

And there are those conversations, too, uncounted and imperative, that extend from the existential (where do we go when we die) to the fundamental (where do babies come from). These are sometimes challenging. They are often inconvenient. And sometimes they require that we step outside of ourselves in order to be the people our children are needing: people who are unembarrassed, and wide-open honest, and sometimes honestly fearful or grieving or humbly apologetic.

In those moments, it isn’t at all about who I am as a person, but it’s about who they need me to be and the answer they need me to give. And often, appallingly, it’s the far more Real Me that they need than I am comfortable giving away.

Which is fine. The discomfort is totally worth it.

***

Good thing we get this practice, this careful evaluation of them-over-us in these specific kinds of moments. Because, for now, anyway, these kinds of things haven’t gone away.

“I only have six more months to be a kid! How do you feel about that?”

What good, in that instant, would all the honesty be, exactly? How good for him to know how I actually feel? That in that instant, standing there in the living room, I was calculating the months between his eighteenth birthday and his high school graduation, hoping that our time with him at home is just a little bit longer than it might seem, realizing that I have left of this extraordinary life under this roof with us only about–give or take–twelve more months?

Twelve months is no time at all.

So I said to him what I’ve said to all of them, when appropriate, from time to time. And it is the truth: “I am so excited for you.”

To see what you’ll do. To see who you become. To watch you have your own life.

***

“You coming?” That was his question to me as we stood together in the little office at Burlington Aviation.

He was about to go up in the cockpit of a Cessna 172, a single flight lesson that was a Groupon-turned-birthday present for our seventeen-year-old son. Yes, there was to be a flight instructor in the seat next to him, and yes, the boy has logged many hours of time on flight simulators.

But the enterprise was nonetheless a terrifying concept. Despite my love of flying, airplanes remain a terrifying concept. What truths–fundamental or existential–have us consistently flinging things heavy as airplanes–peopled!–into the air?

I had many times contemplated this trip with Everett. This forty-minute drive to Burlington, this son-of-mine-in-the-cockpit-flying-a-plane, the harrowing stories of the fiery demise of far too many small aircraft.

“You coming?”

And he had had to schedule and reschedule the lesson quite a few times. This Thursday, that Tuesday, both of us arranging an afternoon- one of us mentally steeling herself- for this event. But wind, clouds, rain always had us putting it off.

Until that Friday, standing in the office of Burlington Aviation.

The person I felt like being, in that particular moment, was maybe the car-going kind, the kind standing securely on the ground. She was the kind who wanted her seventeen-year-old to be seven again, riding his bike in the cul-de-sac, or maybe playing with a toy airplane in the living room.

That was the kind of person I felt like being, but instead I said,

“Yes.”

I deposited some of my fears on the tarmac and buckled the rest under my seat belt. I sat in the backseat and wore my headset and decided that physics and angels (mostly angels, let’s be honest) are all we need.

Because I’ve always meant to be a brave person. I’ve always wanted to be Everett’s mother, even when I hadn’t met him yet.

Because he is absolutely going to have–is having–his own life, and from the backseat of a Cessna 172, I got to see another part of it.

May 17, 2016

Small Boy in Plaid Shorts

See him:

See him:

Small boy in plaid shorts. Helmet. Sneakers. Socks pulled high on the shin. He is no more than four, maybe a little bit three.

He is trying to push his bicycle off the paved trail and into the pine straw, but only the front tire has made it. Rear tire and training wheels remain on the trail. The pine straw resists him.

Ten yards ahead, his father resists him, too. He has stopped his bike, has turned, is watching his son try to push his bicycle off the trail.

See him:

Tall. Sunglasses. Helmet. One foot on the ground, the other on a bicycle pedal. He watches his son, his body leans toward him. He is completely grown-up.

“No, Ari,” he says. “We’re not going to take the back way. We’re going around on the road.”

His voice is barely raised, but I hear him clearly–you and I hear him–though we are at least ten yards, maybe more, on other side of Ari, who might be three years old, maybe four, who is (still) nudging his bicycle off the trail.

His father calls to him again: “This way,” he says.

I–we–imagine we see the predicament. The trail rises, has risen considerably already to the point where Ari is, and it rises further between him and his father, and further still beyond that. Not by a large degree, but it rises steadily. Maybe with legs as short as those, maybe with training wheels, maybe when one is barely four one feels one has come far enough. Perhaps one doesn’t wish to continue this climb. One sees that going the back way might be easier and infinitely better.

Perhaps this bike ride has been long enough.

“Come on, Ari,” the father calls. “You can do it,” he says.

Ari looks behind him. He sees us standing, waiting, where we have stopped walking the dog because we don’t want to impede the boy and his efforts, or those of his father.

And see us, standing there where we’ve been before:

Weary.

Because this struggle has gone on long enough. It’s been entirely enough. This pain, this wait. This persistent absence. This maddening relationship. This relentless trial that has us lying awake by night and anxiety-ridden by day. This not-enough-too-much-of-a-something. We are by all means now ready for the short-cut.

What is it we say? We who are nosing our bicycle-with-training-wheels off the trail, into the pine-straw, ready for the back-road to home?

We say, “Just teach me what I need to learn already so that this can be over.”

Ari turns back to his bike. He maneuvers front tire off pine straw, realigns bicycle to path. Climbs on.

We watch him. From this distance, we imagine we hear the chain clicking into place as Ari applies pressure to pedal. We see the tension lock in the little legs. We see the pedals resist.

“That’s it,” his father says, and the pedals move. Slowly, they glide forward and back. Once around. Twice. Ari’s body is taut. He makes small progress.

He gathers speed. Not that you would call it speed, but still. He is definitely on his way.

And then Ari feels it. We see it and stiffen, waiting. His father sees it too. The angle of the path has increased. The climb is harder here, if only just. Ari isn’t going fast enough. He cannot make it.

“You can do it,” his father says, and Ari stands on the pedals. Who knows how he knows, but he knows that this much will do: this greater effort, this harder work. Pedaling, standing, Ari reaches his father.

And he continues on. His father continues with him. Ari still struggles, but now father and son are pedaling side by side, and Ari’s father gives his son a gentle push, guiding him along as he pedals with his hand on his son’s back.

What lesson, I wonder, did Ari learn? What task ticked on his check-list? His legs are stronger for his effort. His confidence, too. Perhaps his sense of balance, or in the invaluable output of standing to push his best effort into his pedals?

But I wonder–we wonder–as we continue on with the dog, what makes us think that God is a checklist? A workbook? Where in His descriptors is the concept of God as manual?

We say, “Just teach me what I need to learn already so that this can be over.”

Because he is a series of lessons. He is a to-do list. Worse, he is an impediment to life lived as we prefer it.

He is forever getting in the way.

A perspective which might make us miss a thing or two about him: how he leans, how he calls. How he waits. How we might feel, if aware, the broad warmth of his hand, his gentle push, helping us up the hill.

Small Hours

- Rebecca Brewster Stevenson's profile

- 159 followers