Rebecca Brewster Stevenson's Blog: Small Hours

March 25, 2021

Tale of an Inchplant

joy knight photography

It was clear that I had killed it. I couldn’t pretend otherwise. That I had managed to kill it while trying to take care of it, while employing long-practiced skills in extending the life of an outdoor thing that lives inside didn’t really matter. The plant was dead.

Lynne said as much when she saw it sitting sadly in its pot of dirt on the kitchen table. At that point there was only one sprig remaining of what had been a full, trailing, beautiful hanging garden of a thing. One sorry stem barely standing up above the soil. But I had set it in the sun, I had watered it carefully. I had, from time to time, talked to it, encouraging it and telling it that it was wanted.

To no avail. “That’s dead,” Lynne said, and I still believed otherwise, still told myself we couldn’t see what the root system might be doing. And we couldn’t be sure that the magic of photosynthesis wasn’t working its miraculous thing among the remaining leaves. Er, leaf. The plant could rally, I told myself.

Some weeks before, I had noticed signs of the plant’s overgrowth: yellowing leaves, thinning stems. It was outgrowing its pot in the breakfast room where it hung in its macrame web. The only way to save and continue to enjoy it there was to pull it from its pot, cut back its roots, and replant with fresh soil. This was something I had done with other plants many times. I had likely done it with this one. But what I didn’t bother myself with this time was the tenderness of this particular plant’s stems, which had entwined themselves in macrame and each other. As I pulled the root ball from its pot and the plant from that macrame net, I incidentally also tore those stems to shreds.

I didn’t think it would matter. Surely there was enough green left to nourish the plant. But when I packed it back into its pot, I realized how few stems and fewer leaves remained. These struggled to survive for a while, but gradually, stem after stem shriveled. The leaves furled and shrunk, and finally the last stem faded like dry grass.

I didn’t think it would matter. Surely there was enough green left to nourish the plant. But when I packed it back into its pot, I realized how few stems and fewer leaves remained. These struggled to survive for a while, but gradually, stem after stem shriveled. The leaves furled and shrunk, and finally the last stem faded like dry grass.

I was very sad.

This happened just last summer in the midst of pandemic uncertainty. My sorrow over a dead houseplant was probably overkill (for lack of a better term), an exaggerated response to what had become a metaphor of loss.

Why such an attachment to a houseplant, you might sensibly ask? You might point out, and rightly so, that I have others. Others that have been around longer. Far longer, in terms of houseplants. There’s the ficus tree, for example, that I got in Memphis in 1995. And older: the schefflera that started as a cutting from one in my mother’s house. Both of these predate my children. This plant– Tradescantia fluminensis, commonly known as an inch plant and dead in its pot on the kitchen table– was only 9 years old.

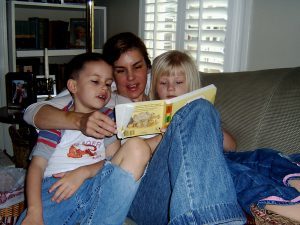

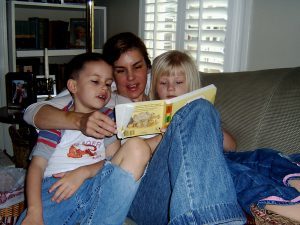

Still, unlike the history of many of my houseplants, I remember buying this one. It was spring break, 2011. I was grateful for a week off from my teaching job and grateful that my kids were off with me. We didn’t have money to go anywhere, but I loved being at home, and I loved the freedom of a weekday errand with Emma to… where? I don’t remember where I found the plant; I just remember standing at the counter of a coffee shop with Emma afterwards, happy about that plant. And I bought Emma a cake-pop.

When we got home, I stood on a ladder in the breakfast room so I could screw a hook into the ceiling. The plant looked beautiful there, and it was very happy. One could say it thrived.

If you have houseplants then you know it can be tricky to find a place where they’re at home. Any place might be too bright, too dark, get too much of a draft. There are so many ways it can go terribly wrong. And of course this indicator is completely false, but there’s something about a happy house plant that suggests the flourishing of the household. In fact, I’ve often told my daughter that, rather than including a garage, a swimming pool, or even a backyard, what a home really needs is these: sunlight and books, plants and music, pets, and, if you can get them, children.

If you have houseplants then you know it can be tricky to find a place where they’re at home. Any place might be too bright, too dark, get too much of a draft. There are so many ways it can go terribly wrong. And of course this indicator is completely false, but there’s something about a happy house plant that suggests the flourishing of the household. In fact, I’ve often told my daughter that, rather than including a garage, a swimming pool, or even a backyard, what a home really needs is these: sunlight and books, plants and music, pets, and, if you can get them, children.

Real plants, I mean, not fake ones. But real plants die sometimes. And sometimes, accidentally, you kill them.

I was sad about that plant. I think I’ve mentioned this already. And you may already think I’m crazy, but there’s more to say. Because somewhere along the line, feeling sad about my inadvertent but absolute destruction of a plant I had loved, I asked God for another one.

Not just another plant. I had plenty of those. I took an asparagus fern and put it in that pot and tucked it into that macrame hanger and it too was very happy suspended from the breakfast room ceiling. But I wanted a plant identical to the one I’d lost. I wanted Tradescantia fluminensis. I wanted a new inch plant with its delicate leaves and tender stems, with its sweet, occasional flowers.

Maybe I wanted another chance.

In the years since I’d purchased it, I had never noticed another one for sale. And so asking God for a new one seemed absurd on two levels: first of all, what I was asking for didn’t seem likely. Lowe’s, Home Depot– they didn’t seem to trade in inch plants. Ivy? Yes. Ferns? Sure. And scads of succulents, but no inch plants. We couldn’t find toilet paper. What were the chances of an influx of inch plants?

And second of all, I was asking God to replace a houseplant in the middle of a pandemic, during a time that my prayers were about the recovery of people on ventilators and the advent of new medical interventions. I was praying for the survival of my husband’s business, the businesses of friends, the perpetual strain on families with young children at home and parents working from home, teenagers isolated from friends and, maybe, help. Racial injustice and political division and fear that fomented so easily into anger and rage.

I still pray for these things. But a global pandemic is no time to ask the almighty God for a houseplant. Is it?

God concerns himself with big things, universal ones. By those lights, pandemics are right up his alley. In a pandemic, the complexity of the human body, its myriad systems, and the intricacy of the delicate immune system all cry out for God’s attention. Then too, we become aware of those things he always sees: how poor health and weakened immunity are so often the accoutrements of poverty. Privilege and injustice, those inequities God sees and calls us to correct, suddenly become unavoidably apparent to the rest of us.

And if one believes as I do that he knows every person by name; knows the number of hairs on each head; cares for and watches over, grieves for and rejoices with every single person on the planet, then certainly a pandemic only heightens his acute focus on the people who suffer most.

In this context– now or ever– how could I ask God for an inch plant?

And here’s the truth, oh patient reader: I asked God for this in the midst of a pandemic, and then I forgot all about it.

I forgot all about it, I say. But there were two of us in that conversation.

***

For a culture (ours) that is so hostile to people judging other people, we are pretty darned judgmental. Have you noticed? That stranger who delayed too long at the green light or who sped through that red one becomes a fool, an idiot, or worse. That’s judging. The pandemic has demonstrated this tendency to judge in bold relief. Take masks, for instance. People who don’t wear masks don’t care about other people. Which is also true, depending on your opinion, research, bias, of people who do.

Casting judgment is in our bones or maybe our DNA. Maybe we do it to make sense of the world, to make ourselves feel better, or to find allies among people who think like we do.

But we may be less aware of this tendency, one I think most of us have: we judge God. We judge him based on what we think he should or shouldn’t do, does or hasn’t done.

But we may be less aware of this tendency, one I think most of us have: we judge God. We judge him based on what we think he should or shouldn’t do, does or hasn’t done.

Just as with the driver at the stoplight or the stranger wearing (or not wearing) a mask, there is more to God than what we are judging him for. At any given moment, we forget his wisdom that spun galaxies and unfurled constellations, that designed the marvel of the immune system and the pattern of fur growth on a dog. The best scientists recognize the unlikely brilliance evident here.

And we also forget God’s sacrifice, a love given in such eager pursuit that it spent itself on our behalf. Christ’s death was terrible loss to God. And for Christ, his death was obedience to a love so incomprehensible, we often simply dismiss it.

But would a God who already suffered such loss out of love for us not (also) care about the smallest of things? Where do we find the limits of the mind that conceived the universe? Where does such power find its end? And where does the depth of a love like this stop?

Does it?

***

Last October, we traveled to the North Carolina mountains for a weekend. That Friday we found ourselves in the little town of Spruce Pine, and in that town we came upon a gift shop that also happened to have a large greenhouse. That greenhouse sold absolutely enormous inch plants.

My husband bought me one for my birthday. It was far too big for the pot suspended in macrame from the breakfast room ceiling. So with great care for the tender stems and leaves, I gently cut that inch plant into viable pieces. And now I have three beautiful inch plants in my house.

You can call it coincidence if you’d like, but this is the way it went: in the middle of a pandemic, I asked God for an inch plant, and he gave me three.

The post Tale of an Inchplant appeared first on Rebecca Brewster Stevenson.

December 7, 2020

Some Questions on the Death of a Cat

There is a place within us that can be reached by intelligence. But there is a deeper one that only the spirit can get to. And that is why those who are “merely completely intelligent” — in science or art, verse or prose — always seem like spies. ~Juan Ramon Jimenez, The Complete Perfectionist

The cats were for my children, who were old enough to care for them when we got them from the animal shelter. I was busy parenting children and teaching full-time. And I had already loved a cat, an extraordinary cat– if cats can be such– and my own. These cats were for my children.

Of the pair, Smokey was beautiful. Soft, fluffy, gray but with dark markings in that grayness as if he’d been over-dyed. Green eyes, pink tongue. Purred so loudly you could hear him across the room, but he almost never cried.

Max was the loud one, and that’s how my daughter noticed him, I think, calling us over to his cage where it sat on the floor. He was alone in there, standing on his hind legs with his little forefeet pressed against the bars. Looking up at us, he meowed and meowed. Pitiable. How could we choose a different kitten when he so clearly was asking to come home with us?

But by comparison to Smokey, Max was, in my eyes, just a standard cat: gray tabby with shorter fur that wasn’t nearly as soft as Smokey’s. Moreover, he was relatively disinterested in us, it seemed to me. Independent and content that way. Ordinary house-cat with outdoor privileges, letting us know if he needed anything and otherwise keeping to himself. Which was fine.

Still, the pair of them were amusing. They played and, in their earliest months, napped together. As they grew into cats and spent more time outdoors, we loved that they rushed to the driveway to meet us when we got home.

Within a few years our menagerie expanded. Now we had a dog, a fish, a rabbit and, for a time, a mouse in addition to the cats. Mostly I paid attention to the dog, who quickly became mine because of all the walks we took together. Otherwise I let the kids attend to our animals– although Max amused us with his ingenious resting places. He would find a new perch and nap there, when it suited him, for a week at a time: in a basket under an end table; on top of an upright pillow; on the otherwise unused desk in our family room where he could, presumably, look out the window. He also loved the boys’ top bunk: the wooden post at one end was soon scarred with the claw-marks he created when climbing his way up.

That damage annoyed me, but only mildly: children need pets, I thought. These were ours. And we weren’t about to declaw a cat who lived, at least part of the time, outside.

The fish eventually died, the mouse (due to outrageous stink) had to find a new home. But rabbit, cats and dog persisted, and I found I didn’t dislike the small busy-ness they created for me: early mornings letting dog out and cats in and then the four of us heading to the kitchen. At this point my children were nearly all grown, one of them out of the house and another on his way, the third virtually also independent. There was something sweet and faintly familiar in this morning ritual: bleary-eyed in the sun-soaked kitchen, pouring food into bowls, seeing to someone else’s needs. Sure, it was two cats and a dog I was serving, not children. But I mostly didn’t mind it.

Over the years, the pets had taken on nicknames, and Max somehow had the most. “Max” became, oddly,” “Mocks” (rhymes with socks) and “Mocksa,” but Bill’s favorite for him was “The Bandit.” This, of course, because of the eponymous film series, a reference lost on all of our children’s friends not to mention our children. But Smokey and The Bandit made perfect sense to Bill, and so Max was “The Bandit” (Bill insisted on the the), and Max answered our call when he wanted to, no matter what we called him, because that’s how he was.

In April 2018, Smokey went missing. Max had been in all night, but Smokey didn’t come home in the morning, and I remembered with a terrible dread the howling coyotes I’d heard the night before. I made signs and posted them around our neighborhood. I went hunting for him in the woods where the coyotes had been seen. I got word from passers-by that they had seen a gray cat here or there; on their recommendation Everett and I drove to a different part of our neighborhood and called down drain pipes and searched along the creek.

Suddenly The Bandit was our only cat, which made that nickname a little sad.

And then, I think it fair to say, he became more affectionate. Rather than curling up by himself somewhere, he sought us out on the living room sofa in the evenings. If a blanket was there, he would hold a small bit of it in his teeth while kneading the blanket with his front paws. If I was in the kitchen, he might come up behind me and lick my ankle, a sign that he needed something. Often as not there was already food in his bowl, but he made it clear that he wanted me to check on that, maybe stir it with my fingers, and then pet him while he ate. He also began to purr.

And maybe this was when I really began to notice him. The way he sat, for example, with this front feet almost always pressed so neatly together. The way, even at eleven years old, he could play with a shadow or a rubber band lying on the kitchen floor. How he always came to the car when we got home and walked ahead of us to the door, throwing himself down at the foot of the steps in the hopes of being petted. His trimness. His athletic bounce as he hurried up the front steps. The way, when he fell asleep next to me on the sofa, he would bend his neck and tuck his forehead against my leg, my arm, whatever part of me was closest. The way, so often when sleeping, he would cover his eyes with a paw.

Now, too, I had time to see him: the precise alignment of stripes on his forelegs, the symmetry of dark lines that extended behind his eyes, the streaks above his eyes that converged into a black patch at the top of his head and then spread out again behind his ears. The muted shades of gray within the paler stripes of his fur and how here, within these pale stripes, he had some hairs that were longer than others.

He was, it turns out, a very beautiful cat.

He was, it turns out, a very beautiful cat.

Last Monday we took him to the vet and had him put to sleep. After multiple visits to determine cause of congestion and rapidly declining weight; after trying to coax weight gain with new food and to defeat infection with medicine, we realized he was battling something far worse than anything we could help him with.

I held him as he died. Held and petted and talked to him, trying to be his last familiar thing in a sterile office. He received an injection that stopped his heart, and then he simply wasn’t there. We were left with a familiar body, beautiful and empty.

And now, of course, we think we see him out of the corner of our eye. Or we think we hear him. The gray blanket abandoned in a heap on the sofa can look, at first glance, just like him. His absence will take getting used to.

If asked months or years ago if I would write a post about my cat, I would likely have said no. He was an ordinary house cat, felis catus. Even the scientific name lacks intrigue.

But I find I have questions now, some of which are perhaps easier to admit at the death of a pet than they would be, say, at the death of a person. Here is as good as any place to ask.

To the scientist, I’m asking: Where did he go?

If the result of evolutionary wonder is merely a beating heart, albeit one that animates a striated and striking felis catus, what expired there? I understand evolution. I understand respiration, DNA, neurons and biological drive. But I do not understand livingness and non-livingness, how life is there and then is gone; and science, so far, doesn’t seem to explain it. There is more to a life than genetic code.

If the result of evolutionary wonder is merely a beating heart, albeit one that animates a striated and striking felis catus, what expired there? I understand evolution. I understand respiration, DNA, neurons and biological drive. But I do not understand livingness and non-livingness, how life is there and then is gone; and science, so far, doesn’t seem to explain it. There is more to a life than genetic code.

To the theologian, I’m asking: Where did he go?

I’m willing to grant that a cat lacks a soul, that the felis catus might not be in need of a Savior. But I’m not willing to grant a Creator who doesn’t love, who didn’t– through evolution or otherwise, all miracle– draw those stripes with a deliberate and loving hand. I’m not willing to grant that the One who teaches us to love would not then also, someday, bring all that he loves to himself. I believe in a Creator whose eye is on the sparrow and so therefore also on my cat.

And to myself, I’m asking the perennial and persistent question, the one I ask often enough and then must put down because the question itself is not actually endurable: When will I learn to love in a measure commensurate to a life’s deserving? I loved Max inadequately, as I love everything.

Max was not an ordinary cat. Nothing and no one is ordinary. There is no such thing.

The post Some Questions on the Death of a Cat appeared first on Rebecca Brewster Stevenson.

November 10, 2020

On Leaving

I fell in love with my husband there in April of 1988. We brought our babies there for holidays and summer vacations. Our children honed their swimming skills in that pool and they sledded down that driveway.

I wrote this to help myself understand my sadness when they sold the house, and I’m reposting it today as I reflect again– after a weekend visit to these in-laws who still live in Hermitage– on what place means and how we become attached to it.

I get very attached to some places. Maybe you do, too.

***

It’s easy to miss the driveway at 1126. Unlike all the other houses in the neighborhood, whose short driveways lead to houses not far from the street, the house at 1126 is invisible from the road. The driveway sits close to a neighboring driveway on one side and a house on the other and is made of gravel. One might mistake it for an unpaved throughway or simply not see it at all. Trees and houses both obscure it; it’s easy to drive by.

Bill (Sr.) told us that once he saw a young girl standing at the top of the driveway, straddling her bike and looking toward the house. He asked if he could help her at all.

“I’m just looking,” she told him. “I used to live here,” she said.

“You’re welcome to ride down and look at the house,” Bill told her.

But she didn’t want to do it. She stood there and looked for awhile, down the gravel driveway with the trees at both sides, and watched where it curved around the house. And then she rode away.

The house itself sits in a private hollow, or on a leveled space along a slope, and it’s surrounded by trees. There are houses all around the house, but they’re separated by space and trees, so the sense of privacy seems absolute. In the summer, you have a hard time seeing it from the roads on the far side of the woods.

It’s a big piece of property, I guess. I’ve never thought about how big. But Bill and Carolyn have left many trees while cultivating lawn and garden too. The property extends beyond the initial tree-formed margin: two paths cut through a little wood and open out onto another stretch of lawn. Here they used to have a vegetable garden. Here blackberry bushes and a peach tree are part of the woods’ edge. And down the hill a little ways stands a cluster of blueberry bushes. Every summer we lift the net and pull the berries into a basket. I don’t know how many pies I’ve made from those berries. This photo is from 2005. It had rained on us while we picked.

I first visited this house in late April, 1988. I had just joined a college singing group, of which Bill Stevenson (the younger) was a member, and he invited the group to the house for a sleepover. He gave me and some others a tour and told us that his father and stepmother had bought the house a few years before when they married and blended their families in a kind of My Three Sons meets The Brady Bunch. With seven sons between them, Bill (Senior) and Carolyn had a full house.

Once, sitting at the bar at Quaker Steak and Lube Bill and I talked with the bartender. She and Bill discovered a shared

acquaintance or something. They had graduated from the same high school. And when she realized who Bill was, she asked if his parents still lived at 1126 Carroll Lane. It seemed her family had lived there once upon a time. He told her they did.

acquaintance or something. They had graduated from the same high school. And when she realized who Bill was, she asked if his parents still lived at 1126 Carroll Lane. It seemed her family had lived there once upon a time. He told her they did.

“I’m so jealous,” she said. “I’ve always loved that house. I was so mad when my parents sold it. I’ve always wanted to buy it back.”

I’ve been to that house more times than I could count now. I know I spent much of 1988’s Christmas break there. After our wedding in 1990, we drove up to the house from Pittsburgh to celebrate with more of Bill and Carolyn’s friends. For three years after we were married, we lived half an hour away, and random visits were common. Ever the consummate host and hostess, Bill and Carolyn have encouraged us to invite our friends to their house for pool parties in the summer. We’ve usually hosted the Richardses or the Liptaks or both every summer, and one year had a party with them and many other friends from college. Here’s Emma and her friend Claire Richards, whose father Adam was a classmate of Bill.

If I took the time to think it through, I might be able to calculate how many Christmases we’ve spent there. With the exception of last year, we’ve visited them there every summer for the last thirteen years, while also making occasional visits in May or October.

Bill (Sr) told me that the man who designed and built this house died not long ago. He had sold the house years and years before and yet, toward the end of his life, kept telling people he wanted to go home. He already was home, he was told. But he didn’t mean “home” to be the place where he lived at that time. He meant 1126 Carroll Lane, Hermitage.

Why, and how, do we get attached to places? It isn’t the place that matters, is it? It’s the people. It’s absolutely the people. So what difference does place make? Of what concern is the angle of the driveway, or of the light as it comes in the afternoons through the trees? What does it matter that this is the floor plan, with the bedrooms just here, and the windows this way so that, when you sit on this sofa on a winter afternoon and your children are napping and it begins to snow, you feel suddenly surrounded by the snow on all sides, and you put your book down and just watch it slowly cover all the rhododendrons?

The sound of a bluejay’s cry will be the same from the lawn of another house. The wind will simply rustle the leaves of different trees. But we won’t be there to watch the bats swoop over the pool when it’s lit up at night, or to watch the birds at their feeder through the kitchen sink window.

Before we left the house for the last time on Saturday, I made my way around the yard and found a thing or two to press in my notebook. Among them, the leaf of an evergreen that Bill Sr. planted in honor of my graduation from college, and a few blossoms of Queen Anne’s lace that I picked on my walk that morning.

It’s strange to me, despite my thirty-seven odd years, despite my own sense of practicality, and intelligence, and reason, the things we can and cannot keep.

The post On Leaving appeared first on Rebecca Brewster Stevenson.

September 12, 2020

Writing A(nother) Book

getty images

I’m a mother three times, and the births of my children were relatively easy. I say “relatively” because they were each (also) fraught in their ways. But the upshot was the same each time: healthy baby, healthy mother. I remain incredibly grateful for this.

The birth of one of them, however, was a little dicey. No, I didn’t require help with the pain on this particular go-round, but I also couldn’t get any help because none of the nurses would offer it. As I breathed through the contractions, a nurse would occasionally pop into the room and then out again. But none of them would stay long enough for me to ask my question: am I getting any closer to having this baby?

I think it was a very busy night in that maternity ward.

It doesn’t matter. As I said, the outcome was what we all hope for. And while this particular baby was blue for a few minutes and while he did have his umbilical cord wound twice around his neck, he was really altogether fine and, moreover, is fine today. Thanks be to God.

I recall only one interaction with a nurse, and this was when Nurse Harder came into the room. The sun was coming up and I was beginning to feel hopeful (because mornings almost always make me feel that way), and Nurse Harder came in at the start of her shift and didn’t leave the room immediately. Instead she introduced herself to me, my husband and my mother: “I’m Nurse Harder, as in ‘Push Harder’,” and I found her little joke incredibly encouraging.

She also checked my progress and told me that “this baby is almost ready to be born,” which is what every laboring mother wants to hear, and that she was just leaving the room to call the doctor. And then she said to me, “Please don’t push yet.”

I remember that instruction distinctly: “Don’t push.” This was really very encouraging and also not encouraging at all, because it meant that the pushing part (which means the baby part) was imminent– but my compliance with her instruction was absolutely impossible.

Because here’s the thing: when the body decides that it’s time to push the baby out, the body is going to push the baby out. When you’ve reached that point in the labor and delivery, the body shifts to auto-pilot. There is simply no stopping the pushing. None.

***

Why am I telling you this?

Well, because, you see: I am about to write another book. I’ve already begun the research. I have, in fact, been researching for quite some time. I am already in that phase of book-writing that looks like distraction but is actually me thinking about plot and characters and potential scenes in this book all the time. Or most of the time, anyway.

Yes, I may look like I’m washing the dishes or walking the dog, folding laundry or heaving a barbell, but if I’m by myself and not engaged in conversation with anyone, if I’m not reading or studying or working on something else that needs me, then you can be sure that I am thinking about Leon. I think about Leon and his problems, about his best friend Paul, about Leon’s wife (whose name I haven’t determined yet) or about their son (whose name I also don’t yet know). And I’m thinking about western Pennsylvania (again) and the Rust Belt, the space left in landscape and economy by a steel industry that skipped town. I’m thinking about love and jealousy and the deepest of friendships, of what hurts us and how we deal (all of us differently) with pain.

Also, quite naturally, I’m thinking of bears. Black bears, to be specific. Why? Because they’re the only kind of wild bear that lives in rural Pennsylvania. Obviously.

***

Perhaps you’re not with me, though. You’re (potentially?) not seeing the link. Why would the vivid memory of the birth of one of my children have anything at all to do with writing a book?

Because. Many (many) people (including me) have tied the two together. They say that writing a book can feel like a pregnancy, from its quiet beginning to its urgent end. Here’s how: a notion of a story sits dimly at the back of one’s mind and then begins to grow. If the story is worthy, if it’s something that is potentially good-for-the-telling, then it just won’t leave you alone. Gradually it gathers momentum, occupying greater and greater mental space, developing in size and complexity, until eventually it’s simply too big to sit there: it must be told. People say that the drive to write is similar to the process of labor: word by word, line by line, the force of the narrative compels the writer to write until finally–through fits of terrible concentration and pressure–the book is finished. The author has no choice but to write until it’s done. Until it is, one might say, born.

That’s why I started this post by writing about childbirth: because I’m writing another book.

But I’ve written here about childbirth and writing (also) in order to say this: childbirth (for me) is no longer the right metaphor for this particular creative process. I mean, I definitely see how it relates. But I think I’ve found a better one.

What is it, you ask?

I answer: bears.

getty images

***

I definitely could be wrong about this. The birth metaphor might be the thing most of the time. But I wonder if this new metaphor has less to do with any metaphor’s aptness and more to do with the story itself. Healing Maddie Brees, my first novel, was the story of a mother, after all.

This new book, despite being set in Pennsylvania’s Rust Belt, is far more agrarian than Maddie‘s suburban world. Its people work in steel mills and factories, yes, but they hunt on the weekends. Their homes are on country roads. Their backyards are big enough to be mown with tractors, and cow-tipping is a thing.

And, like I said, there are bears.

***

Here’s how I see it.

While the wise and educated know to be mindful of bears, they know, too, that bears mind their own business. Typically, I mean. A healthy, normal bear– on catching wind of human presence, on hearing human noise– will skirt that presence instinctively. It will keep a wide berth between itself and the humans, and the humans will never even know it was there.

But there are exceptions. A hungry bear just post-hibernation, blinking in the bright light of spring, might sniff out food that the human campers did not intend to share. A wounded or ill bear might pick a fight with innocent hikers. And everyone knows what momma bears are famous for.

Like I said: exceptions.

I’ve been mulling over these possibilities in moments that look like distraction. What would it be like to be surprised by a bear?

***

Sitting by the campfire in the early morning, waiting for the coffee water to boil, you might not notice some rustling in the underbrush. Your eyes are swollen from last night’s campfire, and the smoke from this morning’s fire is already stinging your eyes. But that water needs to boil for the coffee. After the coffee, everything will be different. Then you can start cooking bacon.

So that rustling blends in with the sound of crickets and birds, with the conversation you’re having with your friends and, just now, the collapse of some wood in the flames. There is no more likely a bear in these woods than there is a new novel in your head. Both would be exciting and way too much trouble, and you are still waiting for your coffee.

Later, though, returned from a hike, you hear the rustling again. Your blood is pumping now, your eyes are clear. You stand and look towards the sound, into the woods where the sunlight falls in bands. You think you see a dark shadow move behind those ferns. You tell your friends, and they look too. You are the only one who sees it.

But on your canoe trip, no one can miss the bear moseying along the river’s edge. Everyone stops to watch it, paddles lying still across their laps. The bear is a big one: someone estimates it between three and four-hundred pounds. Can black bears get that big in western Pennsylvania? Someone says that it’s definitely less than three-hundred pounds. Someone else says it’s a baby, and then everyone starts to look for the mother. Meanwhile, the bear turns away from the river, disappearing into the green woods that close up behind it. You forget about the bear because now you and your friends are having a canoe race, which is much harder than it sounds.

Then you hear the rustling again at night, when you are all sitting around the campfire and the world around you is dark. Do you hear that, you ask your friends, and some of them think they do. You all stop to listen and hear nothing but crickets. Talking begins again, and laughter, but you are still thinking of the bear, three-hundred pounds or more or less. You are thinking that three hundred pounds of anything with claws and teeth sounds dangerous.

Later still, when you and your friends are tucked away in your tents, you hear the rustling noise again. But it’s louder this time and continuous, and this time it’s accompanied by whistling and snuffling noises and the occasional grunt. This is a large thing that has come very close. You raise your head and the dying campfire is throwing a shadow against your tent: the looming, shaggy shadow of a bear.

***

And that’s why a bear is a good metaphor for writing a book. See?

getty images

***

Or maybe you don’t see, which is fine. I’ll explain.

In our earlier metaphor, one simply can’t quit. Once labor has commenced, it really must continue. And once it’s time to push, It’s Time. There is no putting it off or waiting it out. It has to happen. Now.

When you have a bear outside your tent, things are happening. Yes, the bear might (one hopes) get distracted and move on to other things, in which case you might go home and have great tales to tell. Or something truly terrible might happen. But at the Moment of the Looming and Shaggy Shadow, you can’t simply roll over and go back to sleep. No. You are suddenly on high alert, at the ready, and you will not look away until– one way or another– this issue of the bear is resolved.

Writing a book– at least in the phase I’m currently in– is like this. Thrilling, potent, completely absorbing. AND: it cannot be abandoned. How can I leave it now, pretend it hasn’t come this close, move on to– say– repainting the house trim WHEN THERE’S A BEAR OUTSIDE MY TENT?

I can’t.

I have to write this book now. Many, many pieces of it are falling into place. I love the setting (deeply) and the characters already. But I honestly don’t know what is going to happen to them. Most of them, anyway.

Writing this book is the only way to find out.

***

So here’s my news: I’m writing a new book. A novel. It’s about a man named Leon, about his wife and children and his best friend Paul. It’s about the Rust Belt in Pennsylvania and the beauty and challenge of making a life there.

It has a bear in it.

And that’s all I can tell you for now.

getty images

The post Writing A(nother) Book appeared first on Rebecca Brewster Stevenson.

August 4, 2020

On the Back Porch (looking at a poem by Dorianne Laux)

The cat calls for her dinner.

The cat calls for her dinner. (This is a post about a poem, and these are some of its lines:)

On the porch I bend and pour

brown soy stars into her bowl,

stroke her dark fur.

No. It’s not a poem about a cat, although here at the beginning one might think it is. But with poetry– as with so much else– you have to give it a minute. Wait it out some. There’s more coming.

It’s not quite night.

Pinpricks of light in the eastern sky.

See? No more cat.

Some people don’t like poetry– or they don’t think they do.

But that’s not you, is it? You like poetry. You do. I mean, you like a party just as much as the next person. You can do loud and noisy, no problem. But you don’t judge. You like quiet people, for example. You’re willing to sit a minute and listen and then find out that the quiet person has something to say.

Poems are quiet. Mostly. And you like them.

This is a quiet poem, anyway. See:

On the Back Porch

The cat calls for her dinner.

On the porch I bend and pour

brown soy stars into her bowl,

stroke her dark fur.

It’s not quite night.

Pinpricks of light in the eastern sky.

A poem, like– somewhat– a person, is an invitation to see something in a new way. And here, the poet is inviting you with her out onto her back porch. She wants to show you something.

This is just the beginning of the poem. And what– so far– does she want you to see? You can answer that: dusk. The cat and her food. The way the light leaves the sky and the stars begin to come out, those “pinpricks of light” that match, without the poet saying so, the star-shaped food she just a moment ago poured into her cat’s bowl.

She gives us more:

Above my neighbor’s roof, a transparent

moon, a pink rag of cloud.

Ah, you say. I see, you say. Because you, too, have done this– whether or not you have a cat. You have stepped outside late in the day, when the light is going but still held there by a bit of cloud. “A rag of cloud,” she says. How apt. You have definitely seen clouds like that before. You have stepped outside late in the day, just in time to see that day fading, to know that all of it will soon be closed up in the dark.

And now, reading this poem (and because our poet is a good one), you are standing on the back porch with the poet. And with me. We are all three standing on the back porch, and we are each of us alone. Except (perhaps?) for the cat.

It’s quiet out here. The light drains away but is held by cloud, by moon. The stars are coming out.

The poet says,

Inside my house are those who love me.

This is going to be important.

Inside my house are those who love me.

My daughter dusts biscuit dough.

And there’s a man who will lift my hair

in his hands, brush it,

until it throws sparks.

Who is in the house behind you? Whom have you left inside? Are there people who love you and know (or don’t) that you have stepped outside for just a minute to pet the cat, say, or look at the moon? Is someone who loves you inside the house and looking at her phone or reading the paper?

Or maybe you live alone. Or with people who don’t love you. Or with people whom you don’t love. If so, it’s okay: this poem is (also) for you, because anything (everything) can be a metaphor. Stay with me. Our poet has more to say, and so do I.

Everything is just as I’ve left it.

Dinner simmers on the stove.

Glass bowls wait to be filled

with gold broth. Sprigs of parsley

on the cutting board.

“Everything is just as I’ve left it,” she says. There’s stillness here, both inside and out. We’ve seen it outside already: the cloud, the faintest stars, the moon. No sign of breeze. Even the cat has disappeared.

But inside, too, everything is just as she’s left it. And how has she left it? At the edge of ready. Her daughter makes biscuits, the soup is done. It’s time for this family’s supper, just as it was for the cat. Everything inside that house is quiet, waiting for the poet’s return.

And here you stand, I stand, on the this otherwise empty porch. The world is silent, waiting for night. And behind us, what is waiting? Who– or what– is waiting for you?

Maybe your dog waits, curled in his bed. Your phone? Your supper. A bowl of peaches on the kitchen table. Your email. A project you have to return to, that has taken too much time already, that you cannot wait to finish but abandoned just for this moment to read this blog post, this poem, to step out onto your back porch and watch nighttime overtake the world.

Here, the poet stands (we stand) on the porch, and the world– inside and out– waits.

I want to smell this rich soup, the air

around me going dark, as stars press

their simple shapes into the sky,

I want to stay on the back porch

while the world tilts

toward sleep, until what I love

misses me, and calls me in.

This is a poem about love. And, I believe, about contentment.

Our poet stands here on her back porch, and what waits for her inside “are those who love me,” she says. Yet she “wants to stay on the back porch….”

And I’m asking you: do you want to stay on the back porch, too?

You have things waiting inside for you, just like I do. Maybe they are people who love you, and maybe not: but they are what has been given to you and, for the sake of this poem, this conversation, they are the things you love.

In my reading, the poem here asks, Are they enough? When you are standing out there and the world is somehow both dusky and radiant, are those metaphorical persons and things– the things you have been given– enough to compel you inside? Or are you– like me– sometimes tempted to the edge of the porch, to the steps, to the cold, damp grass and the woods that line the yard? To the promise of the unknown and different, the new and exciting, the adventure that might look like love but cannot be love, because “inside my house are those who love me” and inside the house is “what I love.”

Maybe that’s a metaphor for another poem. Or is it?

I want to stay on the back porch

while the world tilts

toward sleep, until what I love

misses me, and calls me in.

Here’s what I’ve learned and am learning: love calls me in. It’s mine to choose, to turn my back on beautiful moon and rag of cloud, to lawn and woods, to new and different. To go back inside.

Love returns to love again and again. That’s how it lasts.

Poem by Dorianne Laux

Laux, Dorianne. “On the Back Porch.” 365 Poems for Every Occasion, The American Academy of Poets, 2015, 236.

The post On the Back Porch (looking at a poem by Dorianne Laux) appeared first on Rebecca Brewster Stevenson.

May 20, 2020

Teaching the Gospel to Children: Foster Intimacy, part 2

This is the fourth post in a series meant to be preceded by an introductory letter. Please read that here.

Listen here:

https://rebeccabrewsterstevenson.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/Pursuing-Intimacy-part-2.mp3

Click here to download the audio file.

Foster Intimacy, part 2

“Shame and death are the two great enemies of the Gospel.” ~Jay Thomas

“Much dysfunction is a function of denying brokenness.” ~Ann Voskamp

“Yet the LORD longs to be gracious to you. He rises up to show you compassion. For the LORD is a God of justice. Blessed are all who wait for him!” ~ Isaiah 30: 18

As you can see, this post is a “part two.” When I first conceived of writing about intimacy, I thought its value could be summarized in a single post– and then, clearly, realized I was wrong.

What’s more, writing about it for this series has convinced me that an atmosphere of healthy intimacy in the home might be the single greatest gift parents can give their children and the very best means through which we teach our children the gospel of Jesus Christ.

In the previous post, I described many of its gifts to a growing child and their family, and I claimed that intimacy is invaluable for parenting teenagers. I also described some ways in which Jesus’ teaching enables intimacy when lived out in the home, and that this is key for current and future joy.

But as I said, there’s more to say. So here we go.

The Nature of Intimacy

The best gift of intimacy is joy. We are made to be deeply known and deeply loved, to be delighted in for who we truly are. This is what God does with every individual, and it’s a gift intended for human relationships, too. I think true intimacy is one of the greatest joys of being alive.

But it must be desired by both parties. Everyone wants it at some level, and children show this innately. In this regard, intimacy feels easy with infants: the physical nature of caring for them bonds us, and they can seem blissfully unaware of our emotional tensions and troubles (more on that to come). But as they get older, they naturally present with difficult behaviors and –unhappily– they are more aware of ours. Within this context, children and parents can pull away from one another.

But it must be desired by both parties. Everyone wants it at some level, and children show this innately. In this regard, intimacy feels easy with infants: the physical nature of caring for them bonds us, and they can seem blissfully unaware of our emotional tensions and troubles (more on that to come). But as they get older, they naturally present with difficult behaviors and –unhappily– they are more aware of ours. Within this context, children and parents can pull away from one another.

Which leads to a third aspect of intimacy: it is constantly threatened. We are broken beings. Overworked, overtired, overwhelmed, we fail to be compassionate. Wounded by past relationships, we are insecure. Selfish and self-absorbed, we don’t clearly see the needs of others.

The vulnerability of family and home exposes our fault-lines. We have tools to help, and the honest apology (as I said in the last post) is chief among them.

But maintaining an atmosphere of intimacy is a responsibility falling chiefly to the grown-ups. As parents, we must deliberately cultivate it–which means we must also look to the ways that we are inadvertently threatening that intimacy. And one of the ways we threaten intimacy is by not tending to our own pain.

Pain Leaks

Pain hurts because it’s crying out to be dealt with. If our hurt is mild–say, a skin abrasion–we know how to make it better: antiseptic and a Band-aid. The same is true of emotional pain–say, a hurtful remark, for which we might need an apology. But if our hurt is deep, or if it stems from something shameful to us, we might ignore rather than deal with it. The pain is only ours, after all. We can shunt it aside.

This may enable us to function well enough. The wound isn’t healed, but we cope with it by pretending it isn’t there. This is called avoidance.

The problem is that pain leaks. We all know how it goes: A poor night’s sleep or a bad day at work can readily translate to irritability with others.

The same is true of unresolved, deep-seated pain, but its impact is more insidious: we have found ways to ignore it, so we are often unaware of how it is impacting others. But just as an untreated wound will eventually infect the healthy tissue around it, my emotional wounds don’t exist in isolation. Sooner or later they impact others, even if the connection doesn’t seem obvious.

The fact is that parents’ pain is visited on their children. This happens in a variety of ways, some of which begin in infancy. Unresolved pain can hinder a parent’s ability to be attuned to the needs of their baby, which can result in maladaptive coping strategies in the growing child. As children grow and mature, their natural egocentrism can cause them to blame their parents’ troubles on themselves, breeding shame that they may not be able to voice. There are other ways, too, that emotional pain in parents harms their children.

No parent intends for these things to happen, and –again– we are often unaware that it’s happening. But our own pain stands ready to hurt others, and our children stand on the front line to receive it. The ensuing pain, passed on from us to our children, erodes the parent-child intimacy that enables children to thrive.

If we want to foster intimacy in our homes, we must look to our own emotional health.

Emotional Pain and Shame

It’s natural to want healing from physical injury or illness, and we have all manner of ways to find it, from Band-aids to hospitals. In our churches, we also pray for the physical healing of others.

Christ’s life on earth included myriad physical healings; the apostles carried on with the same. Paul names healing among the many gifts of the Spirit.

Christ’s life on earth included myriad physical healings; the apostles carried on with the same. Paul names healing among the many gifts of the Spirit.

But emotional pain has traditionally carried a burden of shame with it. Perhaps we think we should be stronger than this, that we can and should get over it already. Or perhaps the circumstances that caused the pain are embarrassing or shameful, and so we ignore them or wish them away.

It’s a natural and destructive progression. Shame is a lie that compounds an injury. We are already carrying an emotional wound and we are ashamed to be carrying that wound. That shame visits more harm on us while also preventing us from seeking help. Pain begs to be protected. Covering it might seem the only way. And so we walk around with the emotional equivalent of a broken bone or an abscess or worse, and we try to deal with it all by ourselves. Or we avoid it and pretend it isn’t there.

But remember what we said before: pain leaks.

Shame and Vulnerability

In order to deal with pain, we have to be vulnerable. We have to expose the wound. We have to turn our own gaze on an ugly, ulcerating injury.

A challenge of emotional pain is that we often don’t know what caused the wound, and we’re afraid of what we might find. Or, perhaps worse, we know exactly what caused the wound, and its exposure will open an appalling vulnerability that we’re not really certain we can bear.

And so shame, left unexposed and unanswered, compounds itself. Like a ripening wound, it expands. We’re ashamed that we’re injured. We’re ashamed of the cause. We’re ashamed to be vulnerable. And so we hide.

That avoidance translates into our relationships, too. We are afraid to be vulnerable, ashamed that others will see our injury, and so we refuse to let others in. This impedes the intimacy we all long for. It creates barriers between us and others– most specifically our spouses and our children.

Meanwhile the ugly ulceration gets worse. We slap a cupped hand over it and make our limping way through the world, deeply hurt and hurting others.

Here’s what we need: someone who loves us. Someone who understands. Someone who will never be shocked or dismayed by what we have done or by what has been done to us. Someone who will listen. Someone who will continue to unconditionally love. Someone who can wipe our guilt and shame away and make us okay again.

We need Jesus Christ, whose willing vulnerability led to his death so that he could show us his love.

And maybe we need to see a therapist.

How Do We Know That We Need Help?

Because of the nature of shame and vulnerability, recognizing our need for help can be difficult. I’m nothing like an expert on the subject; I’ve learned what I’m sharing here from experience (more to follow) and some rich conversations. But in consulting with some professional therapists, I’ve learned indicators we can watch for:

excessive sadness, anger, or irritability

food issues

anxiety

absence of emotional and/or sexual intimacy with your spouse

immersion in social media

overuse of addictive substances

The above may describe any of us at some point or other, so there’s more to consider: Does the presentation of an indicator here create a disruption to you or your family? Would you fight to maintain it? Is it heightened in any way?

In the fall of 2007, I was teaching full-time and developing brand new curriculum, writing my Master’s thesis (due Thanksgiving weekend with no chance of extension), and mothering three children in grade school. During that semester, when multiple claims held every inch of my time, I also began going to counseling.

In the fall of 2007, I was teaching full-time and developing brand new curriculum, writing my Master’s thesis (due Thanksgiving weekend with no chance of extension), and mothering three children in grade school. During that semester, when multiple claims held every inch of my time, I also began going to counseling.

Why? Because my husband and I decided that my rare but intense fits of anger were caused by more than obvious stress. They were hints at a deeper emotional problem, one related to my marriage but that we couldn’t see clearly to resolve on our own.

Sure, we all get angry sometimes. Many of us experience anxiety. We may occasionally get lost on Twitter or Instagram. But in paying attention for a good minute, can we see that maybe it’s not just circumstance? These behaviors might actually be a Band-aid, and the injury underneath is beginning to ooze.

In September of 2007, I knew I was in over my head with some anger issues, so I added that weekly appointment. There was no way I had time for it, but I went anyway for the sake of my marriage, my children, and me.

The Gospel and Healing

Pursuing healing for our emotional pain is enormously instructive to our children. From the outset, it shows them that we haven’t reached perfection. No one has, and no one will. In a culture parading false images of perfection everywhere, we can offer ourselves in contrast: imperfect, and honest about it.

Meanwhile, the pursuit of healing models hope: we can all learn and grow. Even in adulthood we can improve–and the need for growth is nothing to be ashamed of. Growth is intended, I think, to be a source of delight.

All of this is Gospel truth. Jesus came to earth because of our brokenness. He understands that each of us bears pain: both from ways we’ve been hurt and the ways we’ve hurt others.

In his suffering, Jesus took on all the shame of the world, so that we never need to be ashamed of anything in his presence. And in his death, he paid for all the sin of the world, so that we can be forgiven for anything when we ask.

The gospel of Jesus Christ is about healing. But when we don’t seek healing for our emotional wounds, we wound our children and we limit our vulnerability to them, marring our intimacy with them. And we also inadvertently tell them a lie: that Jesus is inadequate to help us face our pain, expose our vulnerability, and heal our shame.

My therapist helped me and my husband immensely over those months of counseling, and since then, my husband and I have gone to counseling together and will do so again. I’m growing. He’s growing. But we’ll never be perfect.

None of us will. We can never create perfect worlds of intimate harmony for our children. Pursuing help is the best we can do, and when we do, we tell our children these gospel truths: Christ is the ultimate source of all healing, and all of our hope is in him.

The post Teaching the Gospel to Children: Foster Intimacy, part 2 appeared first on Rebecca Brewster Stevenson.

April 16, 2020

Waiting on God in a Pandemic

Click here to download the audiofile: Waiting on God in a Pandemic

Or listen here:

https://rebeccabrewsterstevenson.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/Waiting-on-God-in-a-Pandemic.mp3

First thing every morning, before I even open my eyes, I listen for what I don’t hear: school bus brakes, construction’s rattle. Neighbors’ cars pulling out of driveways and the distant wind of traffic on I-40.

These days it’s only birds out there, and a breeze in new-leafed trees. Occasionally the low tear of an airplane.

In another context this might feel creepy: the world is empty and we’re the only people left. It might be a scene of apocalypse and this is the calm before the next disaster, before zombies come crawling out of the woods.

But the opposite is true, and I remember this every morning: everyone is at home because we’ve all been enlisted, waging battle against an invisible enemy via retreat. No one pulls out of their driveway because most of us aren’t really allowed to. Businesses and schools are closed. Everything that can close has shut its doors for now.

In the mornings these days, I listen to the birds.

***

It might be helpful to catalog how and when the world went sideways, but I recall the changes–all so recent–as impressions. I think it was four weeks ago that I was shopping for fruit. The stranger opposite me was wearing a mask. She smiled at me as she picked over the grapes, her eyes’ corners crinkling, and she pulled some grapes from one bag and added them to another. It wasn’t until after I got home that eyed my own grapes with suspicion. Had she touched them? And is there a way to clean a coronavirus from grapes?

The changes were incremental at our gym. We always wipe down our equipment after use with disinfecting wipes. Then we began washing our hands before and after workouts. Class sizes were restricted; everyone had to remain at a six-foot distance. And then the gym closed, with our owner loaning out equipment for the duration. I’m pretty sure that happened three weeks ago, but it feels like it was in January.

I don’t remember when we started social distancing, but that, too, has been going on for months, I’m sure of it. Based on the calendar, Sunday will be the fifth worship service we’ve participated in from home, but it feels more like the tenth. I think of my Sunday school students, of their Jonah projects gone dormant. They’ll likely have the rest of their school year at home. Academic demands will fade into summer instead of blazing out in the heady tumult of last days.

It doesn’t really matter how long it’s been, and no one can tell us how long it will last. And that is part of what makes it so strange: we live by clocks and calendars, and these, in a sense, have been erased.

I’m not the first person to remark that the time recalls the days after 9/11: we’re galvanized by a common enemy, one that–for all the warning–has taken us by surprise. The world as we know it has stopped for awhile even as, in many ways, things look so much the same. We wait for and believe in a return to normal while also courting the very real question that normal may not be possible, or that we’ll have to find a new one.

I remember mornings immediately following 9/11, waking up and listening for airplanes.

***

I say that things look so much the same, that we’re fighting a common enemy, but it doesn’t play out that way. We’re staying home while others brave it out on the front lines: doctors and nurses, technicians and researchers. For now, our friends who work in local hospitals tell us that things remain quiet. They have cleared rooms and schedules of elective procedures and stand ready for an influx of COVID patients, the “surge,” they call it.

I say that things look so much the same, that we’re fighting a common enemy, but it doesn’t play out that way. We’re staying home while others brave it out on the front lines: doctors and nurses, technicians and researchers. For now, our friends who work in local hospitals tell us that things remain quiet. They have cleared rooms and schedules of elective procedures and stand ready for an influx of COVID patients, the “surge,” they call it.

Still, I’m not sure that even these brave ones are on the front lines. The front lines might belong to the people who have the virus, who are quarantined in their homes or in hospital rooms. Recently I read a prayer request for a thirty-year-old woman suffering from double pneumonia and COVID-19. She’s on a ventilator somewhere in New York City, and I most certainly am praying for her.

I can pray and I can shelter in place. I can wash my hands and avoid touching my face. But all things aren’t equal. My battle against this virus feels like meager effort compared with what she’s going through, just trying to breathe.

***

All things aren’t equal.

Three weeks ago, a friend sent me something intended, I’m sure, to be comforting. Lovely in its way, it imagines our sheltering-in-place as a means of grace from Jesus. In fact, the words were put in Jesus’ mouth, like so:

Jesus: I will bring together neighbors, restore the family unit. I will bring dinner back to the kitchen table. I will help people slow down their lives and appreciate what really matters. I will teach my children to rely on me and not on the world. I will teach my children to trust me and not their money and material resources.

As I said, lovely in its way, but I wasn’t taken by its loveliness. In all honesty, this little bit of intended hope actually made me angry.

I pushed back in a return text to my friend. This seems to be all-well-and-good for families, I said. And bringing dinner back to the kitchen table is perfectly fine–unless you own a restaurant, in which case you count on people eating out. But what about people who live alone, I said. What about people who don’t have a family nearby, or who don’t have a family at all? People who count on evenings out or in the homes of friends?

The words-as-attributed-to-Jesus in this rose-colored quarantine fell, to my ear, alarmingly short. That’s what I said to my friend, and she saw my point.

But there was more to my reaction than that. In the days after the schools closed, my thoughts turned to the children who don’t have enough food at home or who have an abusive parent. I thought of the teenagers for whom high school is a refuge, who find solace in the friendship of their peers or in the counsel of a kind teacher.

“Home” is a lovely ideal. Home should be a sanctuary–but it isn’t a sanctuary for everyone. All things aren’t equal.

But that wasn’t the real reason I was angry.

***

The truth is that a shelter-in-place order isn’t terribly troubling for me. I’m a writer, living to a large extent in my head. I definitely miss seeing friends, going to church and the gym and out to eat. But I have plenty of work to do, and I can do it at home.

The truth is that a shelter-in-place order isn’t terribly troubling for me. I’m a writer, living to a large extent in my head. I definitely miss seeing friends, going to church and the gym and out to eat. But I have plenty of work to do, and I can do it at home.

Add to that the comfort of family–which I also have. We get along great. We have plenty of room. We also have plenty of food and (for now) toilet paper.

And then there’s our yard and the oncoming spring, and the system of trails that runs through our neighborhood. Although I haven’t been in a car in days, I have been outside a lot: weeding in the yard and walking or running with family and some friends-at-a-six-foot-distance.

Then I think of people living in Queens, their high-rises pressed up against the Brooklyn-Queens Expressway. The apartments are tiny; the hallways compact. And outside–when they go there–everything is concrete and macadam.

Accustomed to the noise of traffic and car horns, they must find the quiet streets eerie. What do they hear when they wake up? Maybe ambulance sirens.

***

I was definitely angry about this: I will teach my children to trust me and not their money and material resources.

Why in the world should that make me angry? I wrote a book about that, for crying out loud. My husband lost his job in 2001 and then again in 2009; we lived several years below the poverty line. We came crushingly close to filing for bankruptcy more than once.

If anyone has learned not to trust in her money and material resources, it’s me. Right?

But I am my own reminder when I use the word “learn.” It’s a thing we do all the time with God, a thing I and others say. It’s something I finally saw in a new light and then wrote straight into a book: When the suffering continues, when the wait goes on, we all just want to cry “Uncle!” We want–however we can–to find a way to make it stop.

And how does that work with God? How do we make him act? We’ve long ago given up appeasement, offering sacrifices to stem the gods’ angry tide.

Instead we believe in a larger benevolence: that God is allowing the suffering to teach us. And this translates into our begging God to show us his lecture notes: “Just teach me whatever you want me to learn,” we say, “so that this waiting and suffering can be over.”

Here, as with the ancients, God is transactional. If we can just get the payment right; if we can simply learn our lesson; if we can get our pawn into the right square, we can have our lives the way we want them.

Instead of seeking God in our suffering, we (understandably) seek a way out. But if God is real, then he is larger than lessons. The Lord of heaven and earth wouldn’t be about getting us to the right square on the board or the right level in our development. He might rather be contending with us and our deeply meaningful lives.

Note the repeated phrase in the Bible: “Wait on the Lord.” Not “wait on the job,” or “wait on the baby. ” Not “wait on the vaccine” or “wait on the economy,” but wait on him. As if the waiting is opportunity to shift our perspective, to pull our gaze from something distracting and rest it, instead, on him.

As if he wants to get close to us in our suffering.

But we prefer the distraction and seeming self-sufficiency. We prefer the (specious) safety of the everyday.

And so we bargain: Teach me the lesson, we say, so I can get this suffering over with.

But God is not a curriculum, and my life is not a workbook.

Like many sheltering-in-place right now, not sick with the coronavirus but battling via retreat at home, Bill and I are looking at economic trouble. The specter of loss is raising its familiar head. And I am telling you right now: I Am Not Interested.

I will teach my children to trust me and not their money and material resources. Haven’t I already learned this lesson? That’s what I wanted to say to these well-meant words in that text.

Haven’t I already learned this lesson?

Oh. Wait.

***

I work at my kitchen table and look out at the trees. COVID-19 notwithstanding, the leaves have come on steadily over these last weeks. Everything out there is green and shady, lush with life.

And the trail below these trees has been busier than I’ve ever seen it before, trafficked with people and their dogs, their bicycles, scooters, and skate boards, at all times of day.

The neighborhood children are all at home and, while they can no longer play together between the yards, they play as siblings. On Saturday, two sisters who live behind us played for hours with an Eno hammock I’d never seen them use before. This morning a mother carrying a large white bucket trailed her little boys, each of them on bicycles. I wondered if they might be headed to the creek for tadpoles.

Last week before the rain, a chalked hopscotch board appeared on the trail and gradually expanded over the course of days. At its height, it boasted 460 squares, which is a metaphor for quarantine if ever there was one.

Last week before the rain, a chalked hopscotch board appeared on the trail and gradually expanded over the course of days. At its height, it boasted 460 squares, which is a metaphor for quarantine if ever there was one.

Dear friends appeared at our backyard fence a week ago. They had walked to us, having discovered a path that connects our neighborhood to theirs. We called down to them in conversation from our deck for the better part of an hour.

And we’ve come to know neighbors who were anonymous to us before. There’s the couple who have a two-year-old daughter, and a family with three daughters who look to be six and younger. They size up in a row like stair-steps.

I’m seeing many dads out there, too, more than ever before. They come by in families, parents together and pulling their little ones in wagons, pushing strollers, or walking in a group. Just now a father came by on his bicycle, calling a riding route over his shoulder to his son. The boy, maybe five years old, pedaled hard after him. He was on a bicycle with training wheels and wore a spiked helmet.

Looks like the restoration of the family unit to me.

***

Maybe what made me angry was the fact that the words my friend sent me had been put in Jesus’ mouth. That’s audacious at best. Who’s to say that this is what he’s doing? That we can conceive–in the midst of a global pandemic– all or even some of what God is effecting in the midst of it?

Are his purposes ours to declare–and then tuck via quotation marks into the mouth of the Son of God?

I have a hard time with these things.

I realize that what I’m needing are his actual words. The Bible. That gift of tremendous scope and generosity that tells stories of faith and suffering, of waiting and pain and illness and need and of the God who loved and was faithfully himself in all of it.

I need words that connect me to him, words that are in his Word such that I know he understands. Words like these:

How long, O LORD? Will you forget me forever? How long will you hide your face from me? -Psalm 13: 1

Hear my cry, O God; listen to my prayer. From the ends of the earth I call to you, I call as my heart grows faint; lead me to the rock that is higher than I. For you have been my refuge, a strong tower against the foe. –Psalm 61: 1-2

Wait for the LORD; be strong and take heart and wait for the LORD. -Psalm 27:14

Praise be to the God and Father of our Lord Jesus Christ, the Father of compassion and the God of all comfort. –2 Corinthians 1: 3

and also these:

Though the fig tree does not bud and there are no grapes on the vines, though the olive crop fails and the fields produce no food, though there are no sheep in the pen and no cattle in the stalls, yet I will rejoice in the LORD, I will be joyful in God my Savior. -Habakkuk 3: 17-18

Then I feel more free to ask the hard questions: Will I be joyful in God my Savior if the food runs out? If the money does? If one of us–or several, or all–gets ill with this virus?

I will bring dinner back to the kitchen table, read that text. And I think, Will he? OR will I again read this on the debit card scanner at the grocery store: “Insufficient Funds”?

Because that could happen again. The Bible promises the goodness of God, but it does not promise a life absent suffering.

In which case God must be what he says he is: the God of all comfort. I have known him to be this before, insufficient funds notwithstanding, and I count on him to continue.

***

Unlike the proverbial tree falling in the empty forest, an empty bank account makes no sound. You don’t hear it happen. You don’t wake up to it, as to so many birds or ambulance sirens.

Still, an empty bank account is something that the God of all comfort understands. And he knows the sound of a ventilator and the sound of one dying from COVID-19. He knows the agony of losing a loved one to the virus while you can’t be with him in the room.

***

Years ago now, when we were in the middle of a financial crisis, I stood sipping coffee next to a very wealthy woman. We were at church where we worshiped together, and I knew her in that casual way you know someone who goes to church with you and who loves the same Savior you do but with whom you’ve never spent any real time.

Years ago now, when we were in the middle of a financial crisis, I stood sipping coffee next to a very wealthy woman. We were at church where we worshiped together, and I knew her in that casual way you know someone who goes to church with you and who loves the same Savior you do but with whom you’ve never spent any real time.

I knew her to be wealthy only by reputation. She isn’t a fancy dresser. I have no idea what kind of car she drives. But I had heard that she was very wealthy, that her house contained not only an indoor racquetball court (she is a racquetball instructor) but also an indoor swimming pool.

That day, she asked me how I was and I somehow felt safe with the intimacy. Or perhaps our money situation was so challenging that it was on the tip of my tongue. Whatever the reason, I gave her a brief run-down of our current troubles, all the while full of fear and the almost-crying that is so embarrassing.

I don’t know what I expected her answer to be. I know that part of me felt especially strange telling her this, because money makes things weird when you don’t have any and the people you are talking to do.

I remember this: she listened intently to me. And then, before walking away, she told me something true: that God understands our material needs, so I didn’t have to be worried about them.

That was the end of the conversation.

“So do not worry, saying, ‘What shall we eat?’ or ‘What shall we drink?’ or ‘What shall we wear?’ For the Gentiles seek after all these things, and your heavenly Father knows that you need them.” Matthew 6: 31-32.

I knew she was right. I shouldn’t be afraid. I really shouldn’t worry about it. God would be God and would be good to us (again) even if we ran out of money. Even if we had to sell our house or file for bankruptcy and all the specters of loss came barreling incarnate through our door.

But her response showed me something else, too: the keen awareness that she had never faced those specters herself. She had faithfully imparted to me some scriptural truth, but she had no idea what insufficient funds feels like.

And this is not her fault.

***

That text made me angry because it was a pat response. Yes, it was positive and hopeful, but it glossed over all the suffering that is COVID-19. It offered a bright side but made no room for the dark– in which case, who needs the brightness?

The Jesus I know and am learning isn’t like this. He doesn’t put a spin on things. He won’t pretend the sadness isn’t there. He doesn’t tell me not to be afraid and then walk away, casually sipping his coffee.

No. The sadness was his reason for coming here in the first place, for living among us, for putting on this beautiful and painful human life– a life more painful because it is beautiful, because the beauty calls us to something we can’t quite reach.

In him was life, and that life was the light of men. The light shines in the darkness, and the darkness has not overcome it. – John 1: 4-5

The Jesus I know and am learning would never pretend the pain isn’t there. See him at the tomb of Lazarus, knowing he would raise his friend from the dead. He stood there weeping with Mary, because he knew that death is the enemy.

And then, a short time later, he himself died a brutal death.

Now he sits at the bedside of every COVID-19 patient in isolation. With every small business owner holding out hope for her livelihood. With every child who is hungry because they can’t get lunch at school. And with every teenager at the abusive end of an angry parent’s arm.

The God I know and am coming to know says of suffering, “Let me suffer with you,” and “Let me suffer for you.” He doesn’t give me all the answers, but he is the God of all comfort. And that is a God I can wait for.

***

I am still confident of this:

I will see the goodness of the LORD

in the land of the living.

Wait for the LORD;

be strong and take heart

and wait for the LORD. -Psalm 27: 13-14

The post Waiting on God in a Pandemic appeared first on Rebecca Brewster Stevenson.

February 12, 2020

Teaching the Gospel to Children: Foster Intimacy, part 1

This is the third post in a series meant to be preceded by an introductory letter. Please read that here.

Foster Intimacy

“Daring greatly means the courage to be vulnerable. It means to show up and be seen. To ask for what you need. To talk about how you’re feeling. To have the hard conversations.” ~ Brene Brown

“Now we see but a poor reflection as in a mirror; then we shall see face to face. Now I know in part; then I shall know fully, even as I am fully known.” ~ 1 Corinthians 13: 12

“The greatest gift you ever give is your honest self.” ~ Mister Rogers

I took a psychology class in high school in which, among other things, we studied Maslow’s hierarchy of needs. Perhaps you know it? It’s illustrated as a pyramid stratifying needs for human thriving.