Rebecca Brewster Stevenson's Blog: Small Hours, page 6

January 19, 2017

New for a New Year

[image error]Putting a book together is interesting and exhilarating. It is sufficiently difficult and complex that it engages all your intelligence. It is life at its most free.

I started in earnest on a new book today.

It wasn’t one I’ve been meaning to write. For some time now, the list of what I’ve been meaning to write has been the same: a next novel (working title, Church + Main, named for a building project those local to Durham might recognize); a non-fiction children’s book (which has been in process For Some Time Now and shouldn’t take all that long once I set my mind to it (famous last words)); and a work of non-fiction for grown-ups, a quasi-historical effort that tells the story my extraordinary Uncle Bob and, in so doing, also the story of my father’s growing up–which is a fascinating story in and of itself. I am still going to write all of these.

But the book I started in earnest today is none of the above.

No. This book was born the morning after Thanksgiving while I was sitting with my husband in our living room. We were enjoying our coffee and talking with real gratitude about the goodness of God in our lives.

And also the things that have been difficult.

Your freedom as a writer is not freedom of expression in the sense of wild blurting; you may not let rip. It is life at its most free, if you are fortunate enough to be able to try it, because you select your materials, invent your task, and pace yourself.

Later that afternoon while I was walking the dog, the ideas for this book–stemming from that conversation–would not keep quiet in my brain, and I when I got home I told Bill: I’m going to write a book about that.

And he said: Good.

Fast forward some weeks and here we are, with several pages of notes that came all in a rush and then piecemeal for some time afterward. All I did for several hours this morning was to organize these ideas, to figure out how and where they went together and so create a framework for a book.

Shortly, I will type the ideas into a kind of outline (as the grid situation I’ve got for myself won’t do for others) and send them off to a pastor friend who has agreed to give them a look.

And then we’re off to the keyboard, where this skeleton of ideas will gain ligament and sinew, muscle and skin.

It’s no big deal, right? I’ve done this before. Writing, these days, is my job.

The obverse of this freedom, of course, is that your work is so meaningless, so fully for yourself alone, and so worthless to the world, that no one except you cares whether you do it well, or ever.

But for a moment there at the beginning, with my pens waiting, the notebook open and the laptop, some source books within reach, I felt it again: the doubt that, it seems, must come with any creative writing endeavor.

Should this be done? And can I do it?

Can I?

There’s only one way to find out.

Every morning you climb several flights of stairs, enter your study, open the French doors, and slide your desk and chair out into the middle of the air. The desk and chair float thirty feet from the ground, between the crowns of maple trees…. Birds fly under your chair. In spring, when the leaves open in the maples’ crowns, your view stops in the treetops just beyond the desk; yellow warblers hiss and whisper on the high twigs, and catch flies. Get to work. Your work is to keep cranking the flywheel that turns the gears that spin the belt in the engine of belief that keeps you and your desk in midair.

[image error]

***

This post comes to you with gratitude to the amazing Annie Dillard, from whose The Writing Life the italicized passages come.

January 16, 2017

No Boat

[image error]Above the sofa in my living room is a painting that once belonged to my grandfather. A picture of the sea: everywhere water. Peaks and troughs fill more than two-thirds of the frame, all done in deep greenish blues with paler blues for foam and spray. Whitecaps curl and spread on a crest far off and again nearby on the right; they trace the line of a wave’s summit. Their collapsed foam fans across the troughs, dissipating slowly into the green.

A full two thirds of the painting is water, and then the waves give way to a mottled sky. Pale blue appears here and there, but this sky is mostly clouds. They might be piled, light-filled cumulus, but here we mostly see their underbellies: mottled and heavy, the gray presiding over the restless water beneath.

My grandmother didn’t like the painting–and as an artist herself, my grandmother would know. She worked in pastels, charcoal and oils. I have several of her pieces hanging in my house; one of my favorites, a still-life of a pitcher, orange and paring knife, hangs in my kitchen.

She didn’t like the sea painting. It needs a boat, she said. A ship. It needs something.

***

Certainly, this painting couldn’t be called a landscape. There is no land in sight. If one were studying it, making any kind of analysis, it would clearly be called a seascape, void of object. The only focal points, I suppose, would be the two aforementioned crests, those patches of greatest whiteness where the water’s own action has overcome itself and reached its foaming crescendo.

If ever you’ve played in the ocean on anything like a rough day, you’ve known or feared that violence. There’s nothing on earth like it to make you feel your body is someone’s plaything. Caught by a wave, both pushed and pulled by the tremendous strength of the water, you can lose everything, including any sense you once had of gravity, of control, of the powers required for so normal a gesture as standing upright.

There is not a calm space in all of this painting, except perhaps in those very small places where pale blue sky breaks through the blue. Otherwise, the sky is low and moody, full of terrible wind. The whole of the water’s surface, where it isn’t pulled into lines of waves, is sculpted by the wind; and the sky, which sports three distant seagulls, is rushing. The gulls, small white divots far-spread against the clouds, are each in a different attitude of flight. They aren’t so much flying as being flown, carried along by the wind.

***

My mother also doesn’t care for this painting. It needs a boat, she says, laughing and recalling my grandparents’ argument. But she isn’t so critical, my mother. She remembers, as I do, that my grandfather loved this painting.

My blue-eyed grandfather who was raised on salt-water, who loved the sea, and boats. She knows, and I know, too, why my grandfather loved this painting: there is a boat in this picture, and you–in this picture–are on it. This is a painting of what it’s like to be out on the water–far out, and trusting your skills as a sailor. Trusting the mast and the hull and your knowledge of sails and the wind. Knowing the sea itself isn’t so much the enemy. Knowing you can find your way home and that it will be a good time getting there.

***

My grandfather tried to teach me to sail, and I suppose I was somewhat compliant. I know how to rig the Sunfish, how to get her out and back again. But if the wind or waves play any tricks on me, I will be useless. I think I grew up too quickly–moving on to other, land-based things–to get anything like good at sailing.

***

I told my mother why I keep the painting, why it has a place of dominance in my living room. For starters, it fits there, so that’s something. And also, my grandfather loved it, so that’s something more.

But for me it’s also the water’s violence and, bereft of boat, the painting’s sense of isolation.

What would it be like to be out there? To be, beside the gulls, the sole living thing with a head above that plashing, wind-torn surface? To know there was not a chance at standing upright, at finding firm ground under my feet. That the only hope I had was the breath in my lungs and keeping it there, a skilled compliance with the water’s whims, the strength in my legs and arms and, when I knew this was spent, rest that came with trusting my back and my body to the invisible, merciful buoyancy of salt.

***

C.S. Lewis’s Perelandra imagines a world of water, an entire planet without solid ground. A single woman lives on this planet and is necessarily a swimmer. She finds rest on the floating mats of land, but these are not “fixed.” Even the land rides the surface of the water, undulating with the sea beneath it.

I keep this painting because of that novel, because the woman of Perelandra knows something I have known, am knowing, will know: that sometimes we don’t get from God what we think we want–which is security in this life, the ease that comes with our material needs being neatly met, the confidence that all is well and established and safe.

No. Sometimes God does not give us these things but offers us, instead, a better gift: to trust Him.

***

Some days, most days, I would just as soon not trust Him, thank you very much. I would have my bland securities, my safety nets, my tidy little banalities of self-confidence and self-provision.

But given these small idolatries, I would know nothing of the courage it takes to step out of the boat–and swim.

***

“‘Courageous. What is that?'”

“‘It is what makes you swim on a day when the waves are so great and so swift that something inside you bids you to stay on land.'”

“‘I know. And those are the best days of all for swimming.'”

***

We can know Him on the boat, but I think we learn Him so much better in the water.

***

We cannot walk out of God’s will: but He has given us a way to walk out of our will. And there could be no way except a command like this. Out of our own will. It is like passing out through the world’s roof into Deep Heaven. All beyond is Love Himself. I knew there was joy in looking upon the Fixed Land and laying down all thought of ever living there, but I did not till now understand.

— C.S. Lewis, Perelandra

January 9, 2017

Snow

[image error]Up North, they make fun of the way Southerners handle the snow. They say we can’t handle it–which definitely seems true.

Our whole world shuts down: this is our third morning and I haven’t seen a soul outdoors yet today because it’s 8 degrees, because everything froze again last night and still is frozen, because for days we’ve walked–eyes wide–in the wonder of the snowfall and in so doing inadvertently tamped all the powder into ice.

Which now we can’t walk on.

We can’t handle the snow, so we look at it, rush out to play in it, wonder at this strange magic of precipitation that descends in merry dignity.

For a few days, we feel the honor.

On Thursday it will be near 70, and all the snow will be gone. Which is for the best, because in the South, we can’t handle the snow.

But the snow is, in truth, at least somewhat unbearable. Unbearable the way, for a few days, it asserts for us the lines and horizons of our world, the irregularity of shrub and lawn. The accent it lends to the isolated chirp of a bird. How it shows us the footprint of cat and squirrel and something smaller, something we didn’t see.

How the bare trees cradle it, for just a little while, in the crooks of their bare arms.

December 24, 2016

Nativity

From earliest memory, my fascination at Christmas has always been with the nativity–not with Santa Claus. Certainly, as a child I was interested in him. Notions of his sleigh and reindeer, of a dwelling (a village, even) in the snowy reaches of the North Pole, the idea that he bounded through the sky and visited the home of Every Single Child in the world in a period of twenty-four hours–these things most definitely seized my imagination.

But Santa Claus didn’t compel me. Not really. Somehow the man in the red suit was, for me, a limited narrative. My mind didn’t return to it.

The story of the nativity, though. I loved it. Here was endless opportunity for the mind. So much travel, for starters, which to be sure Santa has in spades. But the travel in the nativity story isn’t global and broad. Instead, it’s specific and compelled: Mary and Joseph must go due to the census; the shepherds and wise men must go due to joy.

Then there’s the cast of characters. What a strange lot! Shepherds, wise men. I knew–know–neither of these. Not, anyway, in the sense of their portrayal in the gospels. And Joseph and Mary. An inn-keeper, perhaps. Somehow none of them were ever bland types for me. They suggested themselves as real, once-living individuals, replete with personality and possible pain. These were the audience for a newborn King, but they were also people, and as such, they responded uniquely to the strange events that comprise our understanding of Christmas. And how did they–each of them, in her own way–respond? “But Mary treasured up all these things and pondered them in her heart.” And I did, too.

The gospels tell the story as they must, and scattered throughout are hints and glimmers that also tell parts of the story. “They laid the baby in a manger.” A manger? My upbringing in Pittsburgh’s suburbs, in the outskirts of a Japanese fishing village, in a suburb outside of New York City, held no mangers, no sheep, no shepherds abiding in fields. It was all strange and foreign, and yet somehow, I was invited too. Like the shepherds, like the little drummer boy, I might have been among the unlikely gazers clinging at the worn barn-door–if, in fact, Jesus’ manger was in a barn. For all we know, Jesus was born in a field or inside a sheep fold. His birth was an impoverished one. That much, I think, is certain.

When I was about nine I wrote a nativity play, mostly plagiarized from the Bible. I tried to involve the neighborhood children. Everyone was cast in a role, and the script involved the timely insertion of Christmas carols. I remember one afternoon rehearsing it in the Munnses basement, so excited that we were all going to perform it and feeling frustrated at the waning interest among my friends. I think I still have my copy somewhere, written in pencil on stapled sheets of wide-ruled notebook paper. It is permanently furled into a scroll because I rolled it repeatedly in my palm.

It wasn’t my friends’ fault that we never went into production. When can you cram upwards of fifteen kids of various ages into a neighborhood basement and produce anything like a finished play–all without adult supervision? Our hearts, I think, were in the right place, which is all that matters.

Anyway, I know I am not alone in my fascination with the nativity. Many of us are held by it. At this time of year, we erect small modeled reenactments of it in our homes; we cast the tableau among the youngest members of our congregations. Here in Durham, a local, dominantly African-American high school annually presents a “Black Nativity.” And this year, I’ve been invited to a Facebook group celebrating photos of nativity sets.

Is observance of the nativity just habit? The *thing* that accompanies and gives (perhaps peripheral) meaning to all the rest of the activity at this time of year?

Perhaps it is for some. We are creatures of habit, comforted by the rituals of tradition. Many, I know, would argue that the story of Christmas is just that: a story.

Except that Jesus is an historical person, his birth and death historical events as real as Caesar’s crossing the Rubicon. His resurrection is attested to in the gospels, his missing body confirmed in biblical and other historical writings. And the impact of his resurrection still speaks, still makes its claim.

This year, I am thinking in new ways of the nativity, specifically of that moment in the fields. Shepherds, shocked by the sudden appearance of an angel (an experience that is apparently always initially terrifying), are then treated to a musical performance that must outshine any concert experience ever conceived. The night sky splits wide, and “a great company of the heavenly host” appears with the angel. They say,

Glory to God in the highest heaven, and on earth peace to those on whom His favor rests.

What stuns me this year is this: never, anywhere else in scripture short of Revelation, do we find a moment like this. Not even at the resurrection of Jesus Christ do we have a glimpse at the merry exultation of heaven. Only here, on His birthday, do the heavens crack and give us a look at the joy.

And why? Why would it be at his birth and not at his resurrection? Why here at the beginning, so to speak, and not at the triumphant *end*?

I think there’s much to be said here about time and timelessness, about the wisdom of revelation, about God’s kindness in choosing the humble and poor shepherds in this specific moment.

And there is something to be said about Christmas, about what it is that has held me in the nativity, that has so many of us returning to it again and again due to the time of year and the mystery of that holy impoverishment. I think it’s that in the moment of His birth, in the physical presentation of the Incarnation, the whole of the salvation of God was eternally and for all time effected. The fragile and vulnerable infant was indeed God, was the Lamb slain before the foundation of the world, was the Life that would make all things new and whole and right again. Here, at the beginning of His earthly life, the work of Christ was already finished.

In glory, every tear will be wiped away. His will be the only body with scars.

This is the story of the nativity.

For God so loved the world that he gave his one and only Son, that whoever believes in him shall not perish but have eternal life. For God did not send his Son into the world to condemn the world, but to save the world through him. John 3: 16-17

mind without soul may blast some universe

to might have been,and stop ten thousand stars

but not one heartbeat of this child;nor shall

even prevail a million questionings

against the silence of his mother’s smile

–whose only secret all creation sings

ee cummings

Merry Christmas.

[image error]Meridian Magazine

December 1, 2016

Fourteen Seconds

I was in the mall on a recent Friday morning, a quick stop between the post office and the gym, because sometimes my life is like this.

I was in the mall on a recent Friday morning, a quick stop between the post office and the gym, because sometimes my life is like this.

Except for the mall part. (I actually hate going to the mall, due to its uncanny propensity to awaken desires for things I don’t have and didn’t even know existed until I entered the mall.) So I don’t go to the mall unless I absolutely have to–and on this particular Friday, early Christmas shopping compelled me. The quickest of errands. In and then out again. I knew exactly (well, nearly) what I was after. I would only be five minutes. Ten, tops.

I was halfway up the escalator when I heard my name and turned and saw my friend Kyle coming along behind me.

Kyle McManamy.

(Yes. His last name is McManamy, and if you haven’t tried that aloud yet, you should. McMANamy. See? There. And you should also say it again. It is wonderful to say.)

Kyle is a friend from church. He is the minister to our college students and, living where we do, surrounded by universities on every side (pardon the hyperbole), that means his ministry is large and busy. He and his wife are very busy ministering to and serving and enjoying the college-population of our church.

Meanwhile, we Stevensons are very busy in our ways doing our ministering and busy-ness things, which means that most interactions with the McManamys include conversation about how we really ought to get together. These conversations take place in the church foyer or in the parking lot, or once–between Mary McManamy, Emma and me–in the Back-to-School section of the Target.

Once Kyle said of us that we are among their favorite friends that they never spend time with.

To which we answered, Likewise.

But once–that Friday–Kyle and I had a conversation at the top of the escalator in the mall.

***

I was in a hurry. I was in and then out again, remember? I had to get a thing (or a pair of things) and then be on my way.

Kyle, on the other hand, was leisurely. He was waiting to meet someone. On that Friday morning he had that rare commodity: Time.

So he walked with me. We went to the specific store. He helped me pick out the things. He helped me find a good deal and commended me on my selection and waited for me (browsing the sunglasses?) as I paid for them. And he walked with me back to the escalator.

That Friday was a beautiful morning. Sunlight was sliding through the high mall windows; it was glinting off the (early) Christmas decorations. I was happy to see Kyle, happy to be checking items off my list, happy to have taken the edge off my Christmas shopping–a new goal (to get Most of It Done by Thanksgiving) that wise mothers all around me have long since realized and accomplished but which I have only recently awakened to, being slow like that.

I don’t remember what had comprised our conversation (other than the shopping). I don’t know what we did in the way of catching up. But there at the top of the escalator it was time to part ways, for me to be off to the Next Thing. To say farewell to I-Never-Spend-Time-With-You-Kyle.

Then he turned and said he wanted to ask me a question. I wasn’t allowed to give it much thought, he said. He wanted whatever came to mind. I should answer it quickly. I could have fourteen seconds, tops.

Okay.

“What is the essence of friendship?”

***

Fourteen seconds, my eye. The essence of friendship? How to distill such a priceless abstraction within fourteen seconds–in the mall or anywhere else?

***

I thought of my best friendships, of what makes them work, of how long they have worked, and why.

I thought that “love” was both the obvious and the non-answer–because one can love where friendship does not exist. Indeed, one must. But friendship rests on something else, and while love is there, love is not friendship’s substance.

If one does actually “hem and haw,” if hemming and hawing is a thing, then that is what I did.

Meanwhile, Kyle waited.

He waited in that way that Kyle has: fully engaged, patient. He watched me with a smile brimming on the edge of his eyes, pleased and unbothered. Unlike me–remember?–he wasn’t in a hurry that morning. He would take whatever it was I had to say; he was confident I would say something good. He thought absolutely the best of me–that much was clear, is clear, with every interaction I have with him.

***

I wanted to say: Why are you asking me this? This is not a typical question for a shopping mall. It is not, in fact, a typical question at all. Moreover, I have to get to the gym–because sometimes my life is like this.

I thought he might have a reason, but also he might not. This question is actually the sort of profundity one can expect from Kyle: a rather stunning thing of substance that he makes quietly present in the middle of the ordinaries. It is, with Kyle, even in passing, a warm hello and honest interest, and a residual sense that he very much likes you.

It’s a wonderful thing, isn’t it? to be liked.

***

I thought of something, an answer to his question. I wasn’t sure it was right– but it seemed profoundly true. It was unsettling to say so, lest I was wrong, but I only had fourteen seconds. I said,

“Deep mutual regard.”

Because where love forgives and forbears (and certainly does so in friendship), one can love where one regards little or ill or even not at all.

But a friend is one you heartily like, one you think very well of. Whose advice or perspective is helpful, valuable, even invaluable. Whose foibles or failings are easy to overlook–or forbear–because you esteem her so highly.

Yes, one can regard another in this way and not have it reciprocated–but that is mere admiration.

In friendship, you like each other very well. Very, very well. Each–to the other–is profoundly valuable, deeply important, uniquely precious.

Deep Mutual Regard. That’s what I told Kyle was the essence of friendship, and I agreed with myself. Yes, I thought. That’s right.

***

Then Kyle explained: the college Sunday school class has been discussing one’s relationship with God. Kyle had saved the thoughts of Thomas Aquinas on the subject for last, and Aquinas held that our best relationship with God was one of friendship.

Which would mean that, if my explanation were right, we are meant to be in a relationship of deep mutual regard with God.

Standing there at the top of the escalator in the sun-soaked shopping mall, I was stunned to consider that God would have deep personal regard for me.

***

Does He?

***

Everywhere around us, the mall cried, “Christmas!” Shining bells and balls and strings of lights, evergreen-wrapped railings and an enormous and sparkling tree–

All of it, whether we like it or not, regard it or not, know it or not,

coming to us because of the birth of a baby

who became a man who is also God

who sees every living person who has ever lived

–regardless–

with the Deepest Personal Regard.

***

The life of His Son is His invitation that we Try Him Out and see if we can’t deeply, personally (mutually) regard Him, too.

***

I had to go. The escalator beckoned. The required items were ordered, were bagged. The clock ticked. The car waited (somewhere) in the parking lot.

But I thanked Kyle for his companionship and–far better–for that moment of (Yes, it was!) worship at the top of the escalator in the sun-ridden shopping mall.

I returned to my car, and I went to the gym, and I was changed yet again–because God’s friendship does that always in the most beautifully satisfying of ways, even if it only requires fourteen seconds.

***

But God demonstrates his own love for us in this: While we were still sinners, Christ died for us.

Romans 5:8

Kyle and Mary McManamy

Kyle and Mary McManamy

November 16, 2016

All Things Hold Together

He is before all things

You can’t know–when waking at the gray cat’s paw to a dark sky–how the light will come through the trees at noon.

Other things come first: the sliced turkey laid just so on the bread, carrots and cherry tomatoes, the mandarin, the note on the napkin.

Coffee.

He is before all things, and in Him all things hold together.

The very bad traffic at the light.

In the car-line, Emma’s friend waved at me while I stared blindly out my sunglasses. Then he pulled his hoodie over his flume of hair and kept walking.

Meanwhile, news was of bombings in Aleppo and the child mortality rate in North Carolina, of strategies toward peace in Syria and the horrors of opioid addiction. Of forest fires in the South and a new presidency.

Of four-year-old Susie in the UK who called the emergency hotline and saved her mother’s life.

In Him all things hold together.

But last night you played board games and ate brownies and enjoyed the first fireplace fire of the season, and today you sipped coffee and talked with a new friend about books and guilt and the portrayal of guilt in books

and you realize a thing you are just beginning to know, which is that guilt is like grief, that guilt is, in fact, a kind of grief. And as grief, it won’t go away. It can be denied or pretended against. It can be shoved into a corner or hidden neatly with compassion and the magnanimous gesture

but It Will Out.

He is before all things

And you say to your new friend what you know is true: that there are no easy answers. That even though you believe absolutely in an Answer, that answer isn’t easy.

If it were easy, it couldn’t possibly be the answer.

But in Him all things hold together.

It’s on the way home that you see how the yellow leaves filter the sun like lace inflamed; how the scattering of leaves pointed like pins rolls like a flume in the wake of an SUV; how air and light and color are caught and impossibly suspended together around you; how the loosened maple leaf, drawn down by its stem, inscribes circles on the air.

For God was pleased to have all his fullness dwell in him, and through him to reconcile to himself all things, whether things on earth or things in heaven, by making peace through his blood, shed on the cross.

Colossians 1: 19-20

(Amendment made with gratitude to Lynne, who understands so well.)

November 12, 2016

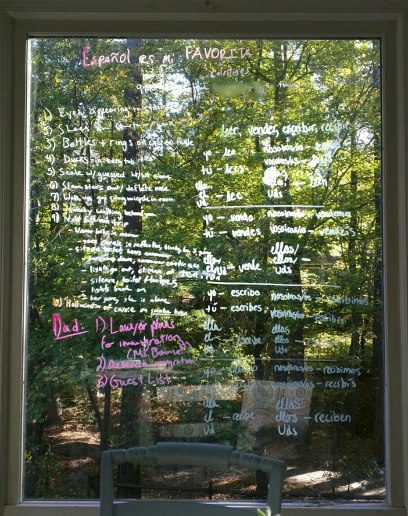

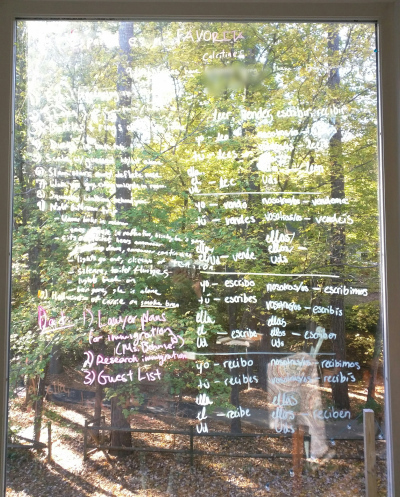

Window

This is the picture window in our breakfast room.

It hasn’t always looked like this. I don’t think we wrote on it–ever–until Emma was home-schooled in the 7th grade. That’s when she helped me see that this window would make an excellent substitute for a white board. And so, throughout her three years of home-school, this window occasionally bore math equations, sentence diagrams, and conjugations of Spanish verbs.

In fact, the entire right side of the window is still covered in verb conjugations (leer, vender, escribir, recibir), some residual practice after her instruction back in May.

Why is it still there, you ask? Well, maybe because I loved home-schooling her, and there’s a part of me that’s sad I’m not doing so anymore, and I’m just not ready to erase it.

And also, cleaning that window is kind of a pain, and maybe I’m lazy, or maybe I’m just doing other things.

Older still is the text on the left side of the window. I don’t remember when that got there, but I think it was also sometime this spring. The five of us were eating dinner, and somehow one of us conceived of an idea for what we thought would be a very funny movie, and the next thing you know, we were creating a trailer for said film. We thought we were so hilarious and clever that we felt the urgency to write it all down.

So what you’ve got on the left is a list of ten shots, not necessarily in sequence, that would comprise our movie trailer, and I don’t want to erase it because it’s hilarious and a conversation piece and a memory of a fun evening.

Also, Will wrote it, and soon he won’t be living here anymore.

At the very top of the window is a line from Everett: “Espanol es mi FAVORITA ……Calcitines.” Not exactly correct spelling. Not perfect grammar. But it is very funny (“Spanish is my favorite… socks”). His spelling includes the tilda over the “n,” and, again, he wrote it–maybe a year ago. So I’m not terribly interested in erasing that, either.

The latest addition, there in the pink at the bottom of the left-hand side, also written in Will’s hand, is some to-do’s for Bill for Will’s upcoming wedding. I think we’ve checked all the items off by now, but clearly I haven’t erased it yet.

It’s a good window.

Except.

As you might imagine, the scrawl we have written here makes it tricky to see out of. Depending on how the light hits it, it’s less a window and more a whiteboard, and in that regard it is more a record of our family than it is any kind of lens onto the outside world.

Which is fine. It’s our window, our breakfast room. And we have other windows in here. I am under no obligation to clean it. No one has asked me to. And when I’ve been working in the backyard–at other times, with other text scrawled across the glass–sometimes strangers have stopped and asked me what it says and why it’s like that.

I’m always happy to tell them.

But when is a window not–also–a metaphor?

Here is our view, colored by our humor, our labor, the things we focus on. It is, in a very real way, a record of what matters to us.

Beyond the glass, the neighbors walk by with their dogs or their strollers. The leaves change, twist, fall. A woodpecker lands in the upper branches of a maple. And a resident neighbor, barely visible through the trees, makes use of a leaf-blower.

We would miss so much if we didn’t also see these things–if all we knew was what we chose to study, what we thought was funny, the tasks immediate to our hands.

If we always only saw what we’d written on the glass, then we might as well have no window at all, and replace the whole shebang with a white board that dully reflected ourselves to us.

From whom we learn so little.

In the course of my 47 years, I’ve had some trouble with people. Not everyone, and not always. But I’ve had people who antagonized me or who, no doubt, felt antagonized by me. I’ve been envious or resentful. I’ve felt with absolute certainty that certain people are mean or selfish, hard-hearted, wrong.

And let’s be honest: each of us is each of those things, often more than one of them at any given time, at multiple points in our lives. In our days.

But every time I’ve been helped by the grace of God to look past those perceptions and taken the time to get to know better the person who is offending or hurting me somehow, I’ve always learned that my perceptions weren’t the whole picture; that there was far more to see, appreciate and love than I had been able to imagine; that I had been, in my judgments, Wrong.

Every time there has been more insight, new understanding, greater appreciation and love.

Every. Time.

View from outside my gym on Wednesday, November 9, the day after election day.

View from outside my gym on Wednesday, November 9, the day after election day.Forgive me if I’ve been a little bit preachy here. It’s been a difficult week, and heaven knows there’s been a lot of preaching. And forgive me, too, if the window metaphor wasn’t just a wee bit too obvious.

If need be, chalk it up to my being a writer, to my needing to do some verbal processing.

Thank you, nonetheless and always, for reading.

And now I think I’m going to clean my windows.

November 6, 2016

On Envy

Note: This post was first published on December 17, 2005, back when our church still had an orchestra that I played in. Because of conversations and thoughts I’ve had of late, I thought it was time to post it again.

Note 2: Not long after I posted this, my parents bought me a new violin. They understood that a new violin was not–is not–the point of this post, but they did it anyway. The photos here are pictures of the instrument I have now.

On Envy

It is my pleasure, in the back of the second violin section in our church orchestra, to share a music stand with tworivers. Tworivers is my dear friend, and it was she who encouraged me, sometime during the summer of 2004, to get my violin out again and join the orchestra. And although I play badly (Badly), I will always think of that encouragement as one of her many Great Gifts to me, because I enjoy playing the violin So Much.

It is my pleasure, in the back of the second violin section in our church orchestra, to share a music stand with tworivers. Tworivers is my dear friend, and it was she who encouraged me, sometime during the summer of 2004, to get my violin out again and join the orchestra. And although I play badly (Badly), I will always think of that encouragement as one of her many Great Gifts to me, because I enjoy playing the violin So Much.

My parents bought my violin for me when I started taking lessons at the age of ten. It was a school instrument, used, not of anything like High Quality. But it served. It served for seven years, waited seventeen, and is serving again. It is a brightly lacquered thing, shiny, with an orange hue and a pinched tone. Not a rich sound, not a beautiful instrument. But I am used to it, and it Works.

Tworivers, on the other hand, has a beautiful violin. Hers is an antique. Hers is not shiny, and the wood is grained in rich browns and yellows. And the sound. Well.

One afternoon during rehearsal, tworivers had the bright idea that we switch instruments. Just for a little while, she said. Just to try it.

I did not want to. No. I knew what would happen.

But she was grinning like she does. She thought it would be such fun. Here, she said, holding out her precious and antique violin to me. Here.

But she was grinning like she does. She thought it would be such fun. Here, she said, holding out her precious and antique violin to me. Here.

We couldn’t have continued the swap for more than a minute, maybe two. I didn’t play her violin for long. But oh, I enjoyed it. A violin like hers just feels different in the hand: softer somehow, as if wants to be played, as if it intends to conform itself to one’s physical being and help one make magnificent music. And her instrument vibrated differently. The sound wasn’t just something the violin made; the sound was something the violin embodied. It bore the sound with its whole, soft self. It was wonderful. Those few minutes were proof of something I already knew: her violin is Much Better than mine.

I wish I had a violin like that.

* * *

The house I live in is not large, but it is, in many ways, charming. It is far from perfect, but I love it. It is all I want in a house, and I am vastly contented in it and deeply grateful. When we first bought it, I was ecstatic.

One afternoon I enjoyed the visit of Kathy Russell, wife of one of our pastors. She is, by gift and hobby, an interior designer, and she was delighted to let me show her our house. I showed her the closet space, I showed her the bedrooms, I showed her the bathrooms, we discussed paint chips. And I said to her– as I’ll say to most anyone– “Isn’t God good to give this to me?”

She and her husband and their five children were living in a tiny house at the time with, she told me, no storage space. But she looked at my house and admired it and was, quite simply, happy for me. Her answer to my delight, to my overjoyed question of God’s goodness, was simple and direct. “Yes,” she said. “And isn’t He good not to give it to me?”

* * *

I think sometimes we get it all wrong. I think, sometimes, we look at what we have, and at what others have, and we look too hard at the Thing Itself. We compare our homes, our violins, our bodies, our hair, our talents, our virtues, and we are, quite plainly, Dissatisfied.

I think sometimes we get it all wrong. I think, sometimes, we look at what we have, and at what others have, and we look too hard at the Thing Itself. We compare our homes, our violins, our bodies, our hair, our talents, our virtues, and we are, quite plainly, Dissatisfied.

And that is because we are looking at the wrong thing. We are looking at the Thing We Have compared to the Thing That Belongs to Someone Else. We are not looking, as we should be, at the Hand that holds that Thing out to us, the Hand that gives it, for better or worse, and declares it to be ours. We are not looking past the Thing to the Hand itself, nor are we looking carefully into the hand– we are not seeing the Scar.

About these ads

Occasionally, some of your visitors may see an advertisement here

You can hide these ads completely by upgrading to one of our paid plans.

Share this:

Press This

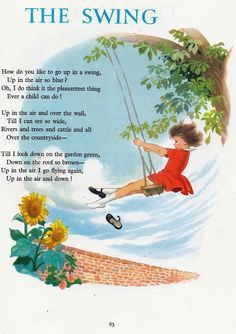

November 2, 2016

Two Questions

The text had two questions, the first from the daughter, who is ten:

“Are you related to Robert Louis Stevenson?”

And the second from the mother, who is old enough to be a mother:

“(The Daughter) is reciting her most favorite tomorrow… ‘The Swing.’ I’ve been coaching her to try to recite it without the cadence because I think it loses meaning. Thoughts?”

Thoughts. Immediate: to swings, and how I love to go up in them.

How do you like to go up in a swing/Up in the air so blue? Oh, I do think it the loveliest thing/ever a child can do!

I’m thinking of the time I learned to pump the swing myself. We were visiting my grandmother in Florida, and my older sister and I were taken by the hand by our father and walked rapidly (my father always walks rapidly) down a sidewalk that had, to one side, a tall white fence. Over the top of the fence we could see lemon trees, and my father sang us a song about them as we went.

Lemon tree, very pretty and the lemon flower is sweet. But the fruit of the poor lemon is impossible to eat.

And this was Very Funny, because my father loves lemons.

We arrived at a park, and my father pushed us on the swings, and then he explained how one leans on a swing and pushes one’s legs out and back again. Suddenly I had learned to pump the swing with my legs, and I could swing on my own.

How do you like to go up in a swing, up in the air so blue?

I pushed William on a swing when he was barely old enough to sit upright. Everett, too. And when Emma turned one, we bought her a baby swing for the swing-set in the back yard. I remember her blond hair, so fine and straight, swaying back and forth from its pigtail above her grinning face.

The mother: “I’ve been coaching her to try to recite it without the cadence.” Thoughts?

Yes, to the mornings my children and I sat around our kitchen table eating breakfast and reciting poetry. It was my way of packing in a few elements of school before they had a chance to realize it: a Bible story, a picture study, a poem over pancakes and in our pajamas.

Among the many, we learned Stevenson’s “My Shadow,” “The Wind,” and “The Swing.”

“Are you related to Robert Louis Stevenson?” I think my children wanted to know if they were, too.

Thoughts?

Yes, to grading papers at my desk when teaching high school, typing paragraphs of encouragement about supporting arguments and placing commas inside (INSIDE) the quotation marks, and wishing from time to time that these students had spent a small corner of their childhoods reciting poetry–and many of them had. Because you can teach a person how to shape an argument, how to develop said argument over a series of paragraphs, how to enfold supporting evidence via quote or paraphrase into one’s sentences. But by the time one is in high school, it might be too late or insupportable to teach the value of rhythm, the power of varied sentence length, the priceless weight of emphasis and inflection, the music of our spoken–or written–words.

The mother: “I think it loses its meaning.”

Can it?

Up in the air and over the wall/till I can see so wide/Rivers and trees and cattle and all/Over the countryside.

I can imagine the daughter standing at the corner of the sofa, reciting. Or seated at the table, head bent over her coloring, reciting. UP in the AIR and Over the WALL till I can SEE so WIDE.

What is the rhythm of this poem if not Stevenson swinging himself? Back and forth, back and forth. The daughter may be sitting at the table, colored pencil in hand, but the words she is saying are motion, and they are moving her back and forth with the poet himself, with all children anywhere ever who have sometime swung on a swing.

Till I look down on the garden green/Down on the roof so brown

Stevenson’s poem will lose its meaning only when there are no longer children outside because they’ve all turned to their iPhones, when all the swings sit idle, when the rushing breeze and flying force born of a child’s volition loses all power to answer.

Up in the air I go flying again/Up in the air and down!

“Thoughts?”

Yes. That surely some of the meaning is lost on the daughter, for whom swinging in this way is so close–for now–to her everyday experience. For her, for now, this mother is doing everything right: getting this poem in the child’s head. It’s Stevenson’s cadence that will keep it there, and so she’ll be saying it in her head for years to come.

And someday she‘ll be pushing her little one on the swing and admiring how the breeze pushes that one sweet curl back and forth, and she’ll mindlessly start saying the poem to her curly-headed cherub. And suddenly the poem’s meaning will bring happy tears to her eyes, just because the realization is so sweet, and she’ll know for the first time that her mother gave her that poem–a gift– years ago, and she’s only just opening it now.

“Are you related to Robert Louis Stevenson?”

Yes. We think so. Scotland is small enough. How many Stevensons can there be?

“Mom, are we related to Robert Louis Stevenson?”

Sure. Why not?

October 31, 2016

A New Podcast

Today I hoped to accomplish a small handful of things which included, but was not limited to

all the laundry

walking the dog

making soup for dinner

writing a blog post

I think anyone would agree this is a very small handful of things. It is not even a real handful, I think– which also makes it luxurious. I am neither unaware of nor ungrateful for this luxury.

Perhaps it will interest you to know that I accomplished the first three. I also spent a Good While trying the fourth, but have abandoned it.

It was meant to be a posted update on my progress with Social Media, something I wrote about six months ago, and it included a metaphor comparing Twitter to the video game Frogger, which then morphed into a metaphor with Alice in Wonderland (in a very Carrollian way, I think), and ultimately became a post best abandoned.

I have duly abandoned it.

Instead I will say that when it is late and when one is tired, the Internet is not always a good place to be unless, perhaps, one is discovering (via Twitter or anything else, really) this.

The New Activist is a pod-cast, now just seven interviews old, featuring conversations with people who care deeply about righting the injustices in this world. Produced by International Justice Mission, the interviews I have heard so far impress me with their intelligence, thoughtfulness, variety and wisdom. Most importantly, each interview encourages me that we can, in fact, do justice; that the dramatic changes we are seeing in this world signify greater opportunity for grace.

I am a writer, but mostly I do laundry. I am a writer, but today I made soup, walked the dog, and ferreted very many pumpkin seeds out of jack-o-lantern guts.

I am a writer who wasn’t terribly successful with writing today, but I was deeply encouraged by listening to The New Activist, and I think you might be, too.

Give it a listen.

He has shown you, O mortal, what is good. And what does the LORD require of you? To act justly and to love mercy and to walk humbly with your God. – Micah 6:8

Small Hours

- Rebecca Brewster Stevenson's profile

- 159 followers