Rebecca Brewster Stevenson's Blog: Small Hours, page 8

May 7, 2016

Each One

There are lot of ways to know people.

There’s the Facebook kind of knowing, the Instagram kind. You know the names of their children, and their dogs. The seminal events, the proud moments, the way their cat curls over a sofa when it rains.

Then there’s the pass-you-in-the-hallway, we-work-together kind. The kind you might chat with at the water cooler, the kind you lean against the door-frame with, talking over the day.

Which is fine.

And then there are Friends in their strata. The Christmas-party kind, the we-went-to-college-together, we-were-roommates-kind. And there are the ones-you-have-for-dinner, or go-out-to-dinner-with.

Which is good.

But of these, some become the staying-too-late kind, the kind you wish would never leave. The ones who call and say, “Is it okay if we just come over?” They are the ones you start too many conversations with, and these all at once; the kind you go on trips with, who know your parents, who drive over in a snow storm just because they want to. They are the ones who offer to do your laundry when the washer breaks, who can tell how you are by the way you say “Hello,” who say things like “I’ve been meaning to ask you” and “We’ve got to talk about” and “I just need to know what you think about this.”

The kind that help you make sense of the world. The kind you really know, and they know you.

Which is wonderful.

Which is wonderful.

But there is another kind, sometimes. They can arrive in a small variety of ways. They come–by invitation or surprise–and stay for years. They are loud and demanding at the beginning; they require all manner of adjustment. They are fatiguing and relentlessly present; they cost enormous amounts of money. They break things. They make messes.

They are complexity of personality; they remind one, uncomfortably, of oneself. They are alarming; they steal your sleep. They require talking-to and listening-to and occasional, serious discomfort.

And they are–if we are noticing–windows onto dissimilarity, kaleidoscopic glimpses into Something True– something that is also True of the Facebook friend with the draped cat, the colleague leaning against the door-jamb, the friend you could talk with forever if only you didn’t have to sleep.

The Something True about every person born or not into this world: Each One is the Only One.

If all goes as expected, we get eighteen or so years’ worth of a fairly keen gaze into the mysterious singularity of Each One–more, if we can manage a friendship.

I’ve decided it’s best to pay attention.

May 6, 2016

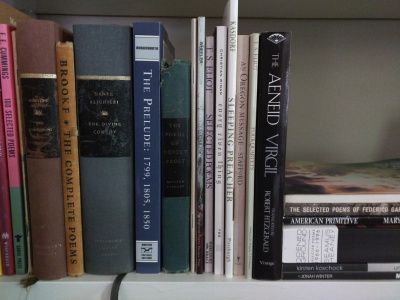

Books Are Your Friends

My mother told me, “Books are your friends.”

My mother told me, “Books are your friends.”

What was I doing? Standing on some, maybe. Or I had thrown one across the room? Maybe I’d written in one: our old family copy of Charlotte’s Web, which I somehow managed to take with me when I left my parents’ house, and which I read to our children three or maybe four times, is inscribed in crayon with large and clumsy efforts at spelling “Becky.” Maybe I wrote in lots of books, maybe I tore their covers, and maybe my mother thought I shouldn’t.

“Books are your friends.” I know I’d heard it more than once–likely many times. I vaguely remember reconciling myself to the statement sometime in high school, for the first time encountering, rational and aware, a mantra that had been ingrained and accepted, a patent fact since time out of mind: “Books are your friends.”

It was true, and I knew it. It had been true–steadfastly, steadily true all my life.

There was that panic at some point during middle school when our local library suddenly announced they would be having a book sale. I walked in fear for days. Which books would they be selling? And why? And could we go to the sale so that I could buy my favorite ones?

Afterward, to my very real relief, the entire series of The Borrowers remained intact, still shelved in Fiction N.

Yes, books are friends. Companions. Anne (of Green Gables) was my best friend in 8th grade. And Charlotte whispers to me from every spider I gently whisk into a tissue to deposit outside.

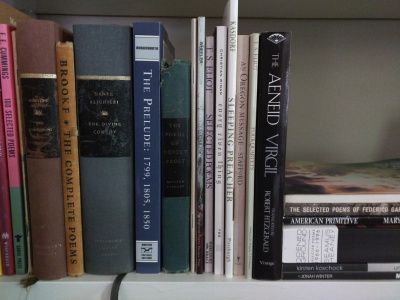

Others accompany me in other ways. Daisy’s dock-end green light and the “fresh, green breast of the new world” are with me every time I return to Long Island and so often when I think of capitalism run amok. The Movie-Goer makes sense for me of life and also the imponderable mystery of New Orleans; The End of the Affair tells more truth about God than I can neatly summarize.

I pace lawns and terraces with To the Lighthouse‘s Mr. Ramsay; I knit socks and brood over tree-top rooks with Mrs. Ramsay. With Ms. Woolf’s Lily I gaze at a table pitched upside down in the branches of a tree; with her Mrs. Dalloway I hear the clocks’ chimes as “leaden circles dissolving on the air.” These characters and scenes are more presently with me than what I served last night for dinner. Recalling them comforts me and also quickens thought.

Reading makes me reach for the dictionary, for a pen. The best and favorite of my books are endlessly dog-eared, their passages underlined or bracketed in the margin, their end-pages re-invented as lists of vocabulary words.

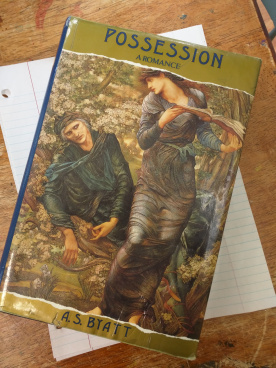

Now and then there are readings that make the hairs on the neck, the non-existent pelt, stand on end and tremble, when every word burns and shines hard and clear and infinite and exact, like stones of fire, like points of stars in the dark–readings when the knowledge that we shall know the writing differently or better or satisfactorily, runs ahead of any capacity to say what we know, or how. In these readings, a sense that the text has appeared to be wholly new, never before seen, is followed, almost immediately, by the sense that it was always there, that we the readers, knew it was always there, and have always known it was as it was, though we have now for the first time recognised, become fully cognisant of, our knowledge.

-Possession, by A.S. Byatt, p. 521. Random House, 1990. Last week I finished reading it for the third time. I read it on my own first in 1993, a second time with a book club ten years later, and now, thirteen years after that. And I find I am not finished with it. My reading this time, again on my own, sent me–as the best books do–to The New York Times book review, just to see what the reviewer made of it back in 1990. But that wasn’t enough. On Saturday evening, I found myself reading The Paris Review No 159, Fall 1991, and also lists of other books by Byatt. I was wanting to find analysis of the poems she wrote for this novel; I was wanting to find discussion on her many uses of the word “possession.” I was looking up “liminality,” I was considering new meaning for the color green. I was making for myself a list of Things To Read Next: Byatt’s The Djinn of the Nightingale’s Eye; Eliot’s Middlemarch (again, gladly); Angus Wilson’s The Middle Age of Mrs. Eliot.

The book had set my mind spinning, and I was wanting conversation. Someone to talk about it with; someone to send my thoughts running with after these and new ideas. If a book is a friend, then it is the best of companions. And if it is a companion then certainly it has things to talk about. Ms Byatt, in 1990, started a conversation. And on Saturday night in my dining room on my laptop, I tried desperately to join it.

Liminality: noun. Being in an intermediate state, phase, or condition.

And now I, too, have started a conversation. It’s not quite as long as Ms. Byatt’s. At 310, mine is the shorter by 245 pages. But this book of mine is an invitation to conversation.

We are in a liminal phase, this book and I. There are current readers out there, but I don’t know them. They are librarians, book bloggers, book reviewers. People in the publishing industry who rightfully get a head-start. And I’ve heard back from a very few. A very very few. The book and I are waiting now for the book’s full release. We are very much in-between.

I won’t say I’m not enjoying this phase. I will say it’s difficult. I think liminality is, by nature, a difficult and complex condition.

But it’s fine. Time passes.

And soon enough, there will be readers. Readers who have asked some of the questions the book is asking, perhaps. Readers who may possibly have answers. Readers who will discover things I meant to tuck into the book’s pages, and maybe some things I didn’t.

What I hope is that this book become conversations, and that we will have new friends because of it.

April 29, 2016

Of Poetry and Chain Letters

I made a mistake. I see that now. I very clearly should have known better.

I made a mistake. I see that now. I very clearly should have known better.

And, in truth, I did know better. And said as much. It’s just that, also, I hoped.

The email came from a deeply thoughtful, intelligent friend. One sensitive to the many challenges we all face in life: the busy-ness, the pressures, the to-do lists. She is a mother and a college professor–in English, of all things. She, of all people, knows what it is to burn the candle at both ends, or to burn the midnight oil, at the very least. Occasionally word of this comes through her Facebook posts: the papers to grade, the piles of assignments to wade through.

She Knows Busy.

And yet she had sent the email. And my first thought was: I don’t have time for this. And my second thought was: I know my friends don’t have time for me to invite them to this. And my third thought was: Poetry. And my fourth: she sent it, and she knows.

What was it, you may ask? Well. Perhaps you’ve seen one of them yourselves. They are terrible things, really. Chain letters. Remember those? Perhaps you were a recipient of one or two back in elementary school: “invitations” penciled on notebook paper with scads of addresses attached and, at the end, a bold and horrifying warning about what it would mean if you were to fail to participate, if you were to be the one to not respond, if you were to cause it–after its year-long or three-years-long or decades-long progression–to come to a terrible demise.

Remember those?

I hated those. They filled me with pressure and dread. I tried to respond as demanded: making lists of potential recipients, beginning the painstaking copies. Then ultimately I stashed them at the back of my desk with the best of intentions, sentencing them to neglect until Well Beyond their “due date.”

They always came with a due date.

But this, from my college-professor friend, was different. First of all, it was an email, so it would be electronic: quick cut-and-paste, hit “send.”

And second: Poetry.

That’s what this was about, folks. It was an email chain-letter, to be sure, but all you had to do was invite some friends and then send One Poem to One Person. And then, the message promised, you would get for your efforts up to fifteen poems arriving in your inbox.

I don’t know about you, but what comes in my inbox is not poetry. Not ever. Not really ever.

Ever.

And what, I reasoned, would be better to balance the noise and obligation and –let’s face it–burden of ones inbox than a Poem? In the midst of calendar items and office memos and the general, insistent flotsam of Modern Life, who couldn’t use the occasional poem?

I thought carefully about this. I had to consider whom to include. Poetry isn’t for everyone, after all. And that is okay–but I wouldn’t want to send such a thing in their direction. Moreover, I positively knew that there were some poetry-lovers who were Truly Too Entirely Busy to be included in this enterprise. To send such a thing their way would only be a sad reminder that their busy-ness forced them to miss out on beauty.

But there were others, I reasoned, who could manage it and who could–and this was What Mattered, really–appreciate and love and even want to receive a poem. There were some out there–friends of mine–who who might want or even crave such a thing. Souls who appreciate the rushing stillness that comes of confrontation with beauty. Who would welcome a good poem in an inbox.

To that end, I wrote a somewhat apologetic overture to the cut-and-paste text of the chain e-mail. I sent this to my carefully selected group of friends. I dug out a favorite (favorite) poem (Richard Wilbur’s “Love Calls Us to the Things of This World”) and sent it to the person named on my email.

And I hoped.

Nothing.

I don’t know what happened. I don’t know if, as it would appear, the college-professor-friend who sent it to me had no other takers, and if that would be what prevented my receiving anything. I’m not even sure how it was supposed to work.

I did hear back from several friends on the matter. Two of them–bless them–were interested participants, but as the enterprise never (apparently) went beyond me, I am guessing they, too, have Nothing But Noise in their inboxes. One friend honestly and sweetly replied that she simply doesn’t have time.

I understand this.

And two friends explained that this isn’t the sort of thing they participate in, to which I replied–but only inwardly–“me either.”

I couldn’t say it outright, because it obviously wasn’t true. I had participated. Foolishly. I don’t have time for this in the twenty-first century and I, with my numerous commitments, obligations, deadlines, should have known better. And not only do I know this about myself, but I had foolishly gone on to invite others to do this with me when, at best, such a thing is only a tease and, at worst, a gadfly.

I made a mistake.

But there was a gift that came of it, albeit undeserved. After all, I had participated in bringing unwelcome clutter to the already crowded inboxes of several friends.

Yet those two friends who kindly explained that they would not be participating went ahead and sent me (each) a poem. And so, in the end, for my efforts, I got two.

Undeserved beauty, I think, but beauty nonetheless.

Here’s one:

“Next Time”

by William Stafford

Next time what I’d do is look at

the earth before saying anything. I’d stop

just before going into a house

and be an emperor for a minute

and listen better to the wind

or to the air being still.

When anyone talked to me, whether

blame or praise or just passing time,

I’d watch the face, how the mouth

had to work, and see any strain, any

sight of what lifted the voice.

and for all, I’d know more–the earth

bracing itself and soaring, the air

finding every leaf and feather over

forest and water, and for every person

the body glowing inside the clothes

like a light.

Chain Mail

I made a mistake. I see that now. I very clearly should have known better.

I made a mistake. I see that now. I very clearly should have known better.

And, in truth, I did know better. And said as much. It’s just that, also, I hoped.

The email came from a deeply thoughtful, intelligent friend. One sensitive to the many challenges we all face in life: the busy-ness, the pressures, the to-do lists. She is a mother and a college professor–in English, of all things. She, of all people, knows what it is to burn the candle at both ends, or to burn the midnight oil, at the very least. Occasionally word of this comes through her Facebook posts: the papers to grade, the piles of assignments to wade through.

She Knows Busy.

And yet she had sent the email. And my first thought was: I don’t have time for this. And my second thought was: I know my friends don’t have time for me to invite them to this. And my third thought was: Poetry. And my fourth: she sent it, and she knows.

What was it, you may ask? Well. Perhaps you’ve seen one of them yourselves. They are terrible things, really. Chain letters. Remember those? Perhaps you were a recipient of one or two back in elementary school: “invitations” penciled on notebook paper with scads of addresses attached and, at the end, a bold and horrifying warning about what it would mean if you were to fail to participate, if you were to be the one to not respond, if you were to cause it–after its year-long or three-years-long or decades-long progression–to come to a terrible demise.

Remember those?

I hated those. They filled me with pressure and dread. I tried to respond as demanded: making lists of potential recipients, beginning the painstaking copies. Then ultimately I stashed them at the back of my desk with the best of intentions, sentencing them to neglect until Well Beyond their “due date.”

They always came with a due date.

But this, from my college-professor friend, was different. First of all, it was an email, so it would be electronic: quick cut-and-paste, hit “send.”

And second: Poetry.

That’s what this was about, folks. It was an email chain-letter, to be sure, but all you had to do was invite some friends and then send One Poem to One Person. And then, the message promised, you would get for your efforts up to fifteen poems arriving in your inbox.

I don’t know about you, but what comes in my inbox is not poetry. Not ever. Not really ever.

Ever.

And what, I reasoned, would be better to balance the noise and obligation and –let’s face it–burden of ones inbox than a Poem? In the midst of calendar items and office memos and the general, insistent flotsam of Modern Life, who couldn’t use the occasional poem?

I thought carefully about this. I had to consider whom to include. Poetry isn’t for everyone, after all. And that is okay–but I wouldn’t want to send such a thing in their direction. Moreover, I positively knew that there were some poetry-lovers who were Truly Too Entirely Busy to be included in this enterprise. To send such a thing their way would only be a sad reminder that their busy-ness forced them to miss out on beauty.

But there were others, I reasoned, who could manage it and who could–and this was What Mattered, really–appreciate and love and even want to receive a poem. There were some out there–friends of mine–who who might want or even crave such a thing. Souls who appreciate the rushing stillness that comes of confrontation with beauty. Who would welcome a good poem in an inbox.

To that end, I wrote a somewhat apologetic overture to the cut-and-paste text of the chain e-mail. I sent this to my carefully selected group of friends. I dug out a favorite (favorite) poem (Richard Wilbur’s “Love Calls Us to the Things of This World”) and sent it to the person named on my email.

And I hoped.

Nothing.

I don’t know what happened. I don’t know if, as it would appear, the college-professor-friend who sent it to me had no other takers, and if that would be what prevented my receiving anything. I’m not even sure how it was supposed to work.

I did hear back from several friends on the matter. Two of them–bless them–were interested participants, but as the enterprise never (apparently) went beyond me, I am guessing they, too, have Nothing But Noise in their inboxes. One friend honestly and sweetly replied that she simply doesn’t have time.

I understand this.

And two friends explained that this isn’t the sort of thing they participate in, to which I replied–but only inwardly–“me either.”

I couldn’t say it outright, because it obviously wasn’t true. I had participated. Foolishly. I don’t have time for this in the twenty-first century and I, with my numerous commitments, obligations, deadlines, should have known better. And not only do I know this about myself, but I had foolishly gone on to invite others to do this with me when, at best, such a thing is only a tease and, at worst, a gadfly.

I made a mistake.

But there was a gift that came of it, albeit undeserved. After all, I had participated in bringing unwelcome clutter to the already crowded inboxes of several friends.

Yet those two friends who kindly explained that they would not be participating went ahead and sent me (each) a poem. And so, in the end, for my efforts, I got two.

Undeserved beauty, I think, but beauty nonetheless.

Here’s one:

“Next Time”

by William Stafford

Next time what I’d do is look at

the earth before saying anything. I’d stop

just before going into a house

and be an emperor for a minute

and listen better to the wind

or to the air being still.

When anyone talked to me, whether

blame or praise or just passing time,

I’d watch the face, how the mouth

had to work, and see any strain, any

sight of what lifted the voice.

and for all, I’d know more–the earth

bracing itself and soaring, the air

finding every leaf and feather over

forest and water, and for every person

the body glowing inside the clothes

like a light.

April 22, 2016

First Event

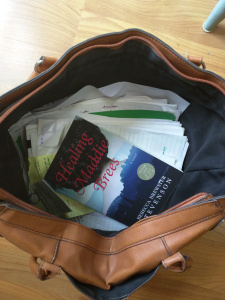

Yesterday I do believe I had what can be described as my First Event As A Writer.

Yesterday I do believe I had what can be described as my First Event As A Writer.

It was not what I had envisioned–though I will say that I haven’t envisioned much in terms of *writer events.* (What are writer events beyond book signings, maybe, at book stores? Real Writer Events are moments like this one when I’m sitting in silence with my laptop. And who wants to attend this?)

But yesterday was definitely all about my being a writer: I was invited because I write, have written, am on the cusp of having a book published.

Yesterday I was the speaker at the Writer’s Club at Neal Middle School.

I tried to attend prepared. Understanding that the students were wanting to meet a Real Live Author, I packed my bag with evidence: the full folder and (separate) stack of papers that are drafts, edited copies, notes and charts and reminders to myself–all the once-essential means by which I got myself to where I am now. To this unruly mess I added two ARC’s and the copy of the book that I am currently working on. And a pen.

And off I went.

The girls were waiting in the classroom. They were Autumn and Mackenzie. They offered me tea. And handing me my tea (peppermint) in a white ceramic mug, they explained that the third, Peri, was sick. They added that she would be Most Disappointed to have missed me.

We sat together at a triad of chairs-with-desks-attached. These desks were familiar: I noted but did not make time to read the penciled graffiti on mine. But unlike the orderly rows in which I was educated, all of these desks were oriented for conversation: they were triangulations, grouped in threes and facing one another in an attitude of conversation. Or conspiracy.

I liked this very much.

And so we sat, the three of us, and talked about books, about words, about writing.

I wanted to know what they like to read: Dragons, mystery, magic. Excellent. And I told them about the publishing process: Agents and publishers and ARC’s (Advanced Review Copies), and this bizarre time of waiting and publicity, of talking *about* the book instead of really Talking About The Book.

I think they understood that.

They listened politely while I read them a passage from my book (I am given to understand that this is a Thing Writers Do) and, wide-eyed, they praised it. As they did my book itself–despite its being only in ARC form.

And I showed them carefully, deliberately, how I am making my way through my own copy, underlining and circling typos, folding down the corners of those pages, looking to correct the errors before it’s too late.

(Here their teacher chimed in: You see, girls, that everyone makes mistakes, that editing is important for everyone, that you mustn’t let your perfectionism get in your way.) So Very Wise.

These girls are writers. Both of them have full-on novels underway, and both of them are plotting (separate) novels for the (eventually) (surely) upcoming NaNoWriMo. They have pen names. They are one another’s editors. Both of them already struggle with things like writer’s block and character development, the blind terror of having to figure out How to Tell It. They use words like “dystopia” and “apocalypse.” They readily identify various types of figurative language. They devise plot twists.

And to escape writer’s block in one project, Autumn has decided to write yet a second novel in the hopes that the character development in this one will help her work out the troubles in the first.

Both of them are Light Years beyond where I was at their age. When I was their age, yes, I read all the time. But when I was their age, writers themselves did not exist beyond the stories I read. Stories and books simply were— like my parents, like trees, like breathing.

Light Years, I tell you.

We sat in our triad for almost two hours, but the time never grew long. I brought a poem for us to study, just in case we needed it– and we studied it, but we didn’t have to. There wasn’t a moment of silence, of dull space. What was it they said? “Just think about all that can come of just twenty-six letters!” (Be still my heart!) They said that, more than once.

It was a beautiful afternoon.

I realize that these girls are products of the twenty-first century. I have no doubt that they have more technological wizardry in their pinkie fingers than I have in the length of both arms. But we sat together for the span of two hours and talked about Books and Writing, Writing and Books.

Toward the end, it was Mackenzie who said it: “Reading books and writing books gives you so much hope.”

I looked at those bright, open faces and thought, but didn’t say it: “So do you.”

And at the end, they wanted my autograph.

I’m sure it’s just a matter of time before I’ll be asking for theirs.

On Forgiving

All I could see at first was the skirt’s long hem and the sensible shoes, which had arrived to pause at the edge of the trail that runs behind our house. Then I saw almost the entire boy, as he was small enough to appear (sneakers and socks, shorts and blue t-shirt) under the leaves of the maple tree.

He had stopped beside this woman, whose gray head now appeared between the leaves. She was bending to show him something at the trail’s edge. What?

From the second-floor window, I had to bend down to see them better: the gray head and the brown one, the smallness of the boy. They crossed the trail to peer at the creek, and I watched how she didn’t hold his hand, how she gave him space to follow her, if he would. I watched the way his walk came from his knees’ unlocking for every step. The walk of a very young boy.

The morning was gray; the light on the path was flat. What were they seeing? What did they say? Our cat went out through the gate to meet them, the gray one who routinely greets people on that trail. Cat and boy disappeared behind the broad trunk of a pine tree, but I watched the woman step back and watch them, and then I saw she was taking their picture.

That was all. Something (someone) needed (always) me, and so I moved away from that tableau: woman, boy, cat, and all that the spaces between them said and didn’t say.

I don’t know what I did next. Maybe I emptied the dishwasher. But I returned to horror over the blogger murdered in Bangladesh on Tuesday, to loss upon loss of earthquake victims in Nepal, to demands in Raleigh for an increase in the minimum wage, to new understanding of poverty in my own town: 28% of our children.

But not the small boy behind my house.

And I returned to the thoughts of yesterday, to the thoughts of a year ago or more, to wounds I thought were closed but yesterday weren’t. And maybe not today, either.

For a long time, forgiving isn’t a thing said-and-done, a sealed deal.

And you can’t close up the gaping wounds of an earthquake, not straight away. The man in Bangladesh is gone forever.

But to fail to forgive is a crime in its own right, the theft of a thing someone paid for. The keeping for oneself (and for why?) what belongs in those sweet, scarred hands.

To fail to forgive is (can I say this?) a kind of killing: the worth of the person reduced to the sum of his failing. To fail to forgive is like turning a blind eye to poverty, to loss in Nepal. I don’t think I’m taking too big or wrong a leap here to say that the former (always) is choosing me, is choosing death.

All the rest is Christ.

And He gives me–gives us–space: to walk with Him, or not. To take His hand, or not.

A short while later, I saw them again, old woman and small boy, walking side by side where they weren’t obscured by maple. She did not hold his hand, but they walked together, and when this time he stopped to look at something, she stopped, too.

I wished I could hear his small voice, his small mouth framing words. I wished I could hear what she said to him, but their words were only for each other. And that is as it should be.

All the Social Media Things

We sat down together in November, my delightful editor and I. Truly, Elizabeth is delightful. Soft-spoken, encouraging, joyful, savvy, and a real Powerhouse of a Person.

We sat down together in November, my delightful editor and I. Truly, Elizabeth is delightful. Soft-spoken, encouraging, joyful, savvy, and a real Powerhouse of a Person.

Elizabeth Gets Things Done.

So I sat down with her because I needed a little help with the whole social media aspect of this book publishing thing. My edits on this novel were very nearly complete at that point, and in this day and age, (almost) no writer is exempt from lending a helping hand when it comes to marketing and selling a book.

Which is fine. And understandable. After all, next to poetry, literary fiction is the toughest sell in books. And poetry doesn’t sell very well At All. Which is a shame. And also the subject of a different post.

The problem is that I am Not Good at social media. Yes, I have degrees in literature and communication arts, but the communication arts end of that was, for me, primarily about writing. I am averse to anything that smells of self-promotion. And this is true not because I am the rare, devoutly humble creature, but because I am the opposite, and I am trying to keep that whole I-Am-The-Center-of-the-World-Thing in check.

But that, too, should probably be the subject of a different post.

Here we have Elizabeth the Powerhouse and I sitting at the table, talking about social media way back in November. I sat with pen poised over notebook, and Elizabeth sat adjacent to me, smiling, offering me tea.

Imagine my surprise when, still smiling, Elizabeth turned the fire hose on me.

The blog needed to be updated in multiple ways–and even (perhaps?) moved. I needed a separate page–an author page–on Facebook. I should start an author newsletter and look into various designs to better decide how to create mine. I needed to start a Twitter account, and Instagram, and I needed to follow the right people on both of these (here she gave me some names).

She was still smiling, encouraging, oh-so-confident in my abilities. And I still sat adjacent, blinking, soaked.

After my blog–which still feels personal, like writing a letter to friends–Facebook was my first foray into social media. Since leaving my full-time job, I have been amazed and (sometimes) not a little dismayed at the time-suck it can be. Given a free minute, I surface to realize I’ve used ten of them just scrolling through my news-feed, *liking* things.

But it’s good, too: my husband calls it “the largest address book in the world.” Through it, I’ve become re-acquainted with long-lost friends and some distant family. It allows me to keep tabs on the doings and well-being (or not) of those far-flung and–often enough–close by. And there are times, frequent enough, when some group I’m affiliated with has a good or even hilarious conversation there. This can be a healing thing, minimizing, for a time, the enormity and overwhelming brokenness of the world.

Facebook is, in so many ways, simply great. And despite my occasional threats to erase my account, I never will. Too much of the world happens through Facebook. It has become important.

So I’ve updated the blog, as you can see. It’s just a new template, cleaner and clearer. But my lack of savvy is everywhere evident. Where is the “About Me” link? The connections to Facebook and Twitter? Where the list of popular posts or even list of posts at all? When I chose this design and worked with an intern on it last week, I thought I could see or at least could figure out what was necessary, but now I’ve spent more time on it and look. Nothing. I don’t know how to work this template, apparently, and I can’t seem to make it show me what it ought to, even if I log in as someone else.

Truth be told, there was never much of anything (was there anything?) in the “About Me” section. It’s that whole aversion-to-self-promotion thing–and of course that’s not wise. A blog is supposed to be an inviting place, a welcoming one. A place where one can engage with others over shared concerns and ideas. These things are not synonymous with self-promotion.

But my blog writing has always, always been about the writing. Sure, I wanted people to read it: one doesn’t write only for oneself. The idea of writing is communication–a word that shares a connotation with community. Fellowship is implied here. How does it go? “We read to know we are not alone.”

Still, when I sit down to write in my blog, the writing is the thing: what I’m going to try to say and how to go about it. That is my first and last concern. Always.

I have often said that my blog taught me how to write. But that posture doesn’t get people to read it.

There was a year–an academic year, 2012-13–in which I was writing full-time. I left my teaching job and, after the kids went to school every morning, it was my job to write.

The amount of time given me on any given day seemed nothing short of miracle. Having home-schooled my children before returning to full-time work, I could only imagine what it would be like to send them off to school and myself Stay At Home. What wouldn’t I accomplish?

But time is not our friend. At best, we guess at his machinations. The window of time between kid drop-off and pick-up was, it turned out, was very narrow indeed. I finished the novel by the skin of my teeth that year, and this required, moreover, a trip away from family to do so.

Now I am home-schooling once again–this time teaching a freshman in high school. And while she is largely independent, I am persistently surprised at the constraints and limits on my time. People need rides, people need dinner. The housework is that proverbially beaded and unknotted string. And home-school takes time, too. When I sit down to do anything having to do with my job as a writer, what I want is to actually write. I don’t want to learn Instagram. I don’t care to Tweet. I want someone else to figure out this blog-format-thing for me, and let me have at it with paper and pen, with clicking keyboard.

Petulant and spoiled? Obviously.

Instagram is a beautiful concept. I have come to enjoy it over the few months of my experimentation with it. And while my ratio of “followers” to “following” has me forever in the red (my daughter explains that one wants more to follow one than one wants to follow, if that makes sense), I decide not to let this bother me.

Which proves once again (exhibit 596) that I am Not Good at social media.

I do love the photographs, though. The pithy statements. For a person who loves and makes meaning in words, Instagram is a respite. I can look, admire, “like” and move on.

But I am no photographer. My phone camera is not the best one out there. My father is a truly stellar photographer; my daughter is also good. But the picture-taking thing is not my thing. I will sooner find words to describe the pale morning light on the bare branches outside my bedroom window than I will think to grab a camera.

Last week I managed to get up earlier than I have been doing, and two days in a row, sitting at the kitchen table, I saw her.

It was very cold, and both mornings she was wearing a coat with the hood up. The hood and the sleeves were fringed in fur; I could not see her face. She carried a hot-pink backpack on her back.

Clearly she was walking to school. The elementary school is up two hills and across a street from here, a pleasant commute.

I think I heard her before I saw her that first day. She was singing loudly, belting out something or other to the otherwise empty trail and woods, the creek and birds that live behind our house.

I watched her walk, listened to her sing. I paused with her as she stood at the split-rail fence. The fence runs for only two lengths along the creek-bed where the creek itself runs under the trail, and the girl paused there and looked over the edge. What did she see?

She proceeded. She took tiny steps, her knees locked, playing a game with the movement. Then her steps lengthened and slowed. She kicked a a leaf. She turned and looked behind her where her early-morning shadow fell along the path. Then she walked again, legs straight, marching.

I was happy for her. All too often I see people walking by with faces locked into phones. This girl was unencumbered, her mind porous to any and everything.

I saw her walking in the cold, and I remembered walks like that when I was her age but in summer, living at my grandparents’ house on eastern Long Island and returning home from the beach through the woods. I was encumbered only by my damp towel, and the woods were mine, and the birds, and the way the light fell through the green. I could sing and no one would hear me–and I did sing.

I can’t put something like that on Twitter.

Twitter confounds me. What do they give you? 140 characters? 180? I don’t know. I don’t think in characters. I think–sometimes–in fonts, but never in number of characters. I am a novelist, for crying out loud. How in heaven’s name does a novelist use Twitter?

I have a deep appreciation for economy in language, and so I bring this much–in terms of appreciation–to Twitter. Economy and efficiency in language are laudable, and they are very real constraints in my work.

But the limitations in Twitter? What is that, a haiku?

It is, nonetheless, my task. It is my *next thing.* The lovely, gracious Elizabeth, fire hose dripping in her hand, made me a promise: “If you sell a million copies, I’ll let you get off Twitter.” That’s what she said.

So I’m off to put this on Facebook, to put it on Instagram, and to tweet this post, which will be my first tweet ever.

Not that I know how. I have to figure it out first.

April 21, 2016

The Color Green

This blog post is a gift to my mother, whose birthday is April 21st. And in loving memory of my grandmother, Grace Everett, whose birthday is the 27th.

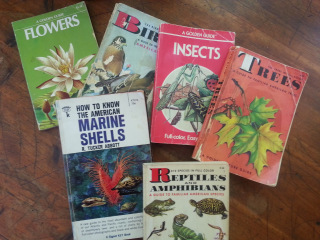

The field guides were kept in the dining room. Not obtrusively on the kitchen table or counter, but just around the corner, accessible to a quick eye and step.

I can’t say I was raised with them, not exactly. Not any more, anyway, than I was raised with frequent dictionary consultations, which came at home year-round, during dinner and other times. The field guides were a summertime thing, a July thing, a component of that month-every-summer with my grandparents on eastern Long Island. As much a part of summertime life as the pineapple wallpaper in the bedroom.

Mostly, I think, it was the bird and wildflower guides we used, evidence of which is here and there in marker on the pages: my initials, my cousin’s, a sister’s, followed by the date. Apparently Meghan and I both discovered a Lady Slipper on 6/13/76; Meghan alone found the Trailing Arbutus on the same day. Our cousin Nathaniel found Chicory on 9/9/78. His initials appear with the date on page 75, written in ballpoint in my grandmother’s fluent script. And on page 38, where my initials (no date) also appear, my grandmother has noted (9/20/78) the Knotweed, underscoring “Smartweed” in the paragraph description, and adding the words “long bristled” in the margin.With my initials in yellow, I laid claim to discovering Crowned Vetch (p. 59); but I recorded no date, and I wonder if that was a nod at honesty, as that vining weed covered the entirety of my neighbor’s backyard hill in Pittsburgh.

My grandparents knew the names of birds and trees, of wildflowers and mollusks. Such knowledge–and an interest in it–was an extension of who they were. As important as knowing words (and their definitions); as knowing how to use “lay” and “lie” correctly. As knowing all the books of the Bible– in order, of course. It wasn’t that they ever lectured on the value of knowing; they just knew. And if they didn’t, they looked it up.

Hence the field guides on the bookcase in the dining room.

I have inherited these field guides, and Birds: a Guide to the Most Familiar American Birds often lives on (rather than in) our home school cabinet in the breakfast room. (On December 29, 1960, my grandfather spotted a Bobwhite; on the seventh of that same month, my grandmother saw a Yellow-Shafted Flicker.) This recent winter, Emma and I worked at keeping our window bird feeder filled, hoping that we’d learn something (someone?) new. But mostly it was the regulars: cardinal, chickadee, tufted titmouse, bluejay. Birds my children already know because I taught them, because my grandparents (and parents) taught me.

What is the value in knowing these names? There are few people we are likely to impress. But there is yet something satisfying in it. Something of Adam, maybe, or Aristotle: to name is to know? To love?

When my sons were very young, I called out names of vehicles in answer to their questions (even now, sitting alone and idle at a traffic light, I have to suppress an instinct to share recognition with an otherwise empty car: “Excavator!” “Cherry-picker!”). And regardless of whether they were interested, all three of my children throughout their childhoods were regularly notified of remarkable vegetation we passed: Forsythia! Pyracantha! Wisteria, its purple blossoms festooning the roadside and trees with “grapes.”

But why do I want to know? Why do I want my children to know? With all that is necessary in life, all that is going on both here and abroad, what is the value in alleviating this (small and insignificant) ignorance? They–the world–can get along quite nicely, thank you, amid unknown flora and fauna.

So many people live in cities, in high-rises, surrounded by concrete and macadam. Squirrel. Pigeon…. Pigeon.

Nonetheless, the interest grows. In these recent weeks, the effort to name has taken on new dimension for me. This year, watching the greening of the spring world, I have been attending anew to the trees. While throughout the winter their identity, distinguishable (somewhat?) by dun trunk and branch, seems (to me) unknowable and even irrelevant, their leaves’ emergence exposes them for what they are. Lately I am trying to name them–and the color of their green.

“Green,” a word that covers but can’t epitomize what I’m seeing. Because the color of the newborn locust leaves is not the same as the crabapple. And the Bradford pears have been, by comparison, a dark green for the better part of the month. Meanwhile, the pendant seeds of the pin oak make that tree’s leaves look almost white. The leaves of the backyard maple are fair. And the distant tulip tree, whose uppermost branches I watch all summer from my kitchen sink window, might be that Crayola spring green I’ve known since I was six.

I find myself reaching for more names. Is there a field guide for green? Celadon, chartreuse, the silver tint of sage. The rich depth of emerald, the blue-bordered jade, the pale and honest shock of peridot. It’s a new and not entirely safe enterprise, this effort to claim names for tree and leaf color together as I’m driving down the road. I think I’ve got it: lime! loden! in what I know is birch; but by the time I name it, the tree and its color are gone, replaced by maple, by white oak, by pin oak, by … oak. All of them turning green.

I imagine I can do a better job staring out my bedroom window. I–and the trees–are standing still now, but it’s nonetheless difficult to bring them into focus. The trees appear in layers, this one and that one closer to or further from the house, strata of leaves in stages of emergence, layers playing tricks on my eyes.

What is it with naming anyway? To identify, to classify, to pin it down in construct of consonant and vowel. The leaves and their color come on without me, they will emerge and expand, and it will matter little or not at all that this afternoon at 3:46 that leaf was the shade of an avocado. The inside of an avocado, to be specific. Guacamole green.

The morning light is coming through the kitchen window above the sink. It catches and hangs on the leaves of the forsythia branch I brought in some weeks ago. The golden yellow blossoms have dropped away, but there is the green of the serrated leaves, all lit up with the sun. This illumination catches my eye and I hang there for a moment, studying blade and vein, the faint polygonal structure of its surface. Words rise and cluster in my brain: photosynthesis, chlorophyll, chloroplast.

And then, just beyond the window sill, the wind hits and the newborn leaves answer. The sun strikes them. They are diaphanous, incandescent, a shifting, glowing mass of light-bearing green. All words leave me, save some chorused by an organ, sung by the congregation-choir of my grandparents’ church there on the eastern end of Long Island, so many summers, every summer of my life.

Let all things their Creator bless

And worship Him in humbleness

O, praise Him

Alleluia!

There is something to naming that opens the eyes. That’s what it is. It’s when we know it that we see it–and not the other way round. Was this what my grandparents knew? Teaching me–so early–to open my eyes. Helping me to see things seen and unseen. To love. And then, so naturally, to praise.

Praise, praise the Father, praise the Son

And praise the Spirit, three in One!

Oh, praise Him!

Alleluia!

Oh, praise Him!

April 15, 2016

Goodreads and Maddie Brees

My novel and I are in a strange twilight these days. I finished the book over a year ago, completed the edits for publication in January, and was handed a hard copy (two of them, in fact) last month.

My novel and I are in a strange twilight these days. I finished the book over a year ago, completed the edits for publication in January, and was handed a hard copy (two of them, in fact) last month.

For all intents and purposes, this book is ready to go.

Except that it isn’t.

There is much to learn, I’ve found, for a writer-of-books when it comes to publishing. And here is where I’m glad to have landed in a world of experts, because I am Nothing of the Kind when it comes to publishing. Or marketing, for that matter.

But back in July, when my editor and I sat down to talk about Maddie making her way into the world, Elizabeth told me that we could just let loose. We could, she said, do these final edits and go to print and be ready to sell books in a matter of weeks.

But that would absolutely kill the book, she said.

It would seem that (who knew?) people are everywhere writing. It would seem that thousands of books (millions?) are produced every year. It is easy–so easy–for a book to be one of a flood of new releases, noticed and loved for a minute, perhaps, or seen, maybe, or overlooked, or never noticed at all.

Without the months of waiting, without the marketing that is currently taking so much effort (mine and that of my publisher), Maddie would founder, would wreck, would quietly be washed away.

I worked way too hard and too long on this book to willingly let that happen.

And so we are in the marketing phase. We have hard copies of books–scores of them, in fact. Right now I am in possession of four copies and have given two away: one strategically, in the hopes of gaining interest, and one to a friend, because I needed to.

And other copies have made their way out to reviewers all over the place, while still others are electronically available to, again, book-reviewing people: people like bloggers, librarians, educators, journalists–all people who might choose to read Maddie and to find–as I hope–that they love her.

Meanwhile, this is a strange twilight for me, for my book. It’s a now-and-not-yet kind of time. The book is realized. Finished. And silent. And this is difficult.

If asked, I could give you a hundred reasons for my writing this book. But one of them is this: there are ideas here I am hungry to talk about.

As a wise friend recently said, “A book is an invitation,” and I could not agree more. Healing Maddie Brees is precisely this: Come in. Let’s talk. I was wondering what you think about this. And this. And this.

But you’ll have to read the book first. And I’ll have to wait until you can.

So the invitations are out, but not exactly. And the RSVP’s are coming back. But not really.

The waiting has begun. Absolutely.

If you are on Goodreads, I invite you to be an early reader! Enter to win one of five free copies. Here.

April 10, 2016

Highway

The Poem If a proverb can be a way to say it, if life can be a highway, then this was a week of heavy traffic.

Personally, I prefer a two-lane road, one of a country or–on a bad day–suburban variety, with cars traveling both ways. And as a speed limit goes, thirty-five sounds good to me, potentially slow enough to acknowledge the countenance of the other driver. To see that there is a driver, at least.

But this was a week at a minimum sixty-five, with four lanes of traffic going each way, which makes eight. A week of blowing horns, the Doppler Effect coming and going, the rapid-fire blast of car, bus, and delivery van.

All week around here it was lumbering thunder, and in the dust of the eighteen-wheeler’s wake, I dodged the traffic and made the best of it. I kept my head down. I took breathers in the tossed-up grit and gravel of the berm.

Thursday, I thought, would be a quieter day. I could, at the very least, stay home. The indoor traffic could be lighter; I could reduce it to six-lanes.

But before I was out of bed, one of our sons was at the bedroom door, needing a ride to school. Because three cars for four drivers is a privilege and a blessing, but sometimes it isn’t enough. And then there was the guitar lesson, which I had forgotten, and the grocery list, whose Doppler Effect was screaming ever louder in my ears.

I went out.

The Prose The road outside the guitar teacher’s house is one with a view. I’ve driven it hundreds of times, but on Thursday morning noticed it’s a road traced by amber lines. As I pulled out of the driveway, these lines caught me by how they bend, how they follow the rise and fall and curve of the road.

On Thursday morning at 10:15, that road was feeling shadows it hasn’t known in a while. The tracery of branches is thickening now, the once-clean lines have blurred. The trees that line the road are taking on their springtime greens: chartreuse and loden, extremes of yellow and brown. Right now the trees are spun in these colors that soon enough will soften and meld, will be the soulful green synonymous with summer.

I had forty minutes to get home, shower, eat breakfast. But I drove slowly enough down that road because it split the tree-line. Between the implications of the leaves was a sky in blue and white and gray, clouds packed and drifting, fringing light and clutching dark, offering fistfuls of slate, pewter, lead.

And here’s the thing about roads, about highways, lined as they might be with trees or forests, with buildings tall and far as the eye can see: There where they are is sky, too, if only a narrow glimpse of it.

Small Hours

- Rebecca Brewster Stevenson's profile

- 159 followers