Charles Olsen's Blog: Pensamientos lentos, page 2

March 12, 2022

Frame to Frames: Your Eyes Follow

I have been invited to be one of the judges of the ekphrastic poetry film prize ‘Frame to Frames: Your Eyes Follow’ presented by Sarah Tremlett of Liberated Words in LYRA 2022, Bristol Poetry Festival. The evening opens with poetry films curated by Helen Dewbery of Poetry Film Live on the festival theme 'Breaking Boundaries: New Worlds'.

It takes place on Sunday 3 April at 2:30pm at Brunel's SS Great Britain's Viridor Theatre, Bristol. Entry is free and you can reserve your tickets here: lyrafest.com/#events/e72158

Read more about the the event and and the judges of ‘Frame to Frames: Your Eyes Follow’ on Liberated Words.

Find the full festival programme, 31 March – 10 April, at www.lyrafest.com

March 5, 2022

Ensayo en WMagazín

ENGLISH: My article on videopoetry from Colombia has been published in the literary journal WMagazín (Links below). It is in two parts and includes twelve videopoems, some of which have English subtitles. You can read a shorter version in The London Magazine , part of a special Colombian issue, December 2021.

—

A finales de 2020 empecé a investigar la videopoesía de Colombia y preguntar a los realizadores sobre sus trabajos. Ahora, con mucha alegría comparto mi ensayo que ha sido publicado en WMagazín: La videopoesía se abre paso con nuevas sensibilidades en Colombia (1)

La primera parte cuenta con obras de Ana Maria Vallejo, Juliana Hernández Rocha, Jose Girón (Los cuadernos del diablo), Juan Camilo Egea y Lilian Pallares.

La segunda parte cuenta con obras de Tulio Restrepo, Yamileth Martínez Delgado, Cecilia Traslaviña, Angye Gaona, Camila García, Ana Maria Vallejo, El Canto de las Moscas - Tríptico animado, y Leo Castillo, y lo puedes leer aquí: La videopoesía se abre paso con nuevas sensibilidades en Colombia (2)

February 17, 2022

Vertigo

My poetry film Vértigo began with a poem which will appear in my next collection due out in 2022. It looks back to childhood and the things which take over our attention as we grow up.

The wood is from the slats of a broken oak chair I found in a skip, the typography and colours are inspired by hand-painted writing on local cafes and bars in my neighbourhood in Madrid, and I decided to dress for the office to give a patina of taking my work seriously, mirroring the sense of play and irony present in the poem.

Basically, it was all a lot of fun to make, and it was selected for Cork: 7th Ó Bhéal International Poetry-Film Competition 2019, and Spain: V Maldito Festival de Videopoesía 2021.

You can watch it here!

January 29, 2022

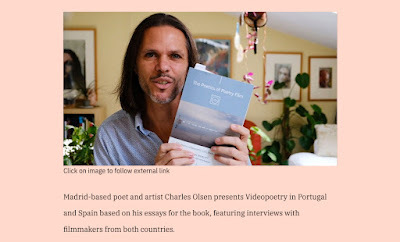

VERSOPOLIS – Videopoetry in Portugal and Spain

The European poetry platform VERSOPOLIS opened their Brave New Literatures festival on 24 January 2022, and it includes the documentary with interviews with videopoets from Portugal and Spain which I made for the 25th Video Poetry Festival VIDEOBARDO (in Argentina).

You can find the link to the documentary here on VERSOPOLIS.The documentary has subtitles in both English and Spanish – click on CC for languages.

The documentary includes interviews with Eduardo Yagüe, Alejandro Céspedes, Alexandre Braga, Agustín Fernández Mallo, Belen Gache, Celia Parra Díaz and excerpts from poetry films by Santiago Parres, Jordan T. Caylor, David Argüelles, Jokin Pascual, En Buen Sitio, Sándor M. Salas, Lilian Pallares Campo and Angel Guinda.

There is also an in-depth interview with writer and filmmaker Sarah Tremlett discussing her book 'The Poetics of Poetry Film' with the director of VideoBardo, Javier Robledo.

La platforma europeo VERSOPOLIS abrieron el festival Brave New Literatures el 24 de enero 2022, e incluye el documental que hice con entrevistas a videopoetas de Portugal y España para el 25º Festival de Videopoesía VIDEOBARDO (Argentina).

Puedes encontrar el enlace al documental aquí en VERSOPOLIS.El documental tiene subtítulos en castellano y inglés – haz clik en CC para los idiomas.

Incluye entrevistas con Eduardo Yagüe, Alejandro Céspedes, Alexandre Braga, Agustín Fernández Mallo, Belen Gache, Celia Parra Díaz y una muestra de videopoemas de Santiago Parres, Jordan T. Caylor, David Argüelles, Jokin Pascual, En Buen Sitio, Sándor M. Salas, Lilian Pallares Campo y Angel Guinda.

Además hay una entrevista con escritora y videopoeta Sarah Tremlett donde habla con el director de VideoBardo, Javier Robledo, sobre el libro 'The Poetics of Poetry Film'.

December 20, 2021

Poetry and Image in Colombia

I'm really excited to have a short essay in a special Colombian Edition of The London Magazine guest edited by Ella Windsor. You can read it here: The London Magazine

It features two beautiful animations: 'Love in Nine Postcards around the World' by Ana Maria Vallejo and 'Hojas' (Leaves) by Camila García. Both have English subtitles.

November 29, 2021

Ser optimista: Dos años de pánico

[This article was originally published in English with the title 'On Being Sanguine: Two Years of Panic and a Response to Terror in Christchurch'. You can read it online in Cordite Poetry Review.]

Publiqué este ensayo en inglés en el 2019 en la revista de poesía, Cordite Poetry Review, en Australia, y quería compartirlo en castellano ya que las vivencias no se limitan por el idioma. Lo escribí posteriormente a un ataque terrorista en Christchurch, Nueva Zelanda, cerca de donde vivía de niño, pero su mensaje tiene un alcance más general sobre la condición humana y en estos tiempos de pandemia e incertidumbre espero que su tema de la ansiedad disparada y la superación de ella puede aportar alguna respuesta o al menos un señal de esperanza.

[Tiempo de lectura 15 min]

Agradezco a Lilián Pallares y Camilo Bosso por sus revisiones al texto en castellano.

Autorretrato de Charles Olsen en Wellington, NZ (1991)

Un domingo, cuando era estudiante de arte en Londres, me subí a mi bicicleta dejando la casa parroquial de mis padres en Surrey para ir a mi habitación en Murray Mews, siguiendo el río Támesis y atravesando los parques londinenses: Bushy Park, Richmond Park, Hyde Park y Regents Park. Me picó una abeja o avispa por los alrededores de Shepperton, que me alteró la sangre y me hizo ir a la carrera hacia la capital, quizás demasiado rápido para mi bien; una reacción a la adversidad.

*

No sabía cómo responder al atentado terrorista de Christchurch en Nueva Zelanda. Era algo completamente inesperado. Por casualidad, pocos días después fue la presentación en Wellington de una colección de poemas de poetas migrantes y refugiados en Nueva Zelanda con el título More of Us (Más de nosotros) de Landing Press. Incluye mi poema ‘Cuando menos lo esperas’, que habla de una serie de atentados cerca de los sitios donde estuve viviendo en Londres, El Cairo y Madrid. El atentado más devastador que menciona ocurrió en el año 2004 en Madrid, donde resido en la actualidad, unos seis meses después de mi llegada a España. Una serie de explosiones en los trenes de cercanías a la hora punta mataron a 193 personas, dejando unos 2.000 heridos. Yo iba en un tren que salía desde Atocha mientras se abandonaban mochilas con bombas dentro en los vagones de los trenes que circulaban en sentido contrario hacia la misma estación. Sin duda debería haber escuchado una de las explosiones a lo lejos sobre el ruido del tren, pero no fue hasta cuando llegué a las 8:00h a la empresa donde impartía clases de inglés y me encontré a mis alumnos reunidos alrededor de la radio escuchando las noticias, que me enteré de lo ocurrido. Estaban sorprendidos de que hubiera podido llegar. No tuvimos clases aquel día y volví al centro de Torrejón de Ardoz a buscar la parada del autobús para volver a Madrid.

La vida continuó, pero habían cambiado pequeñas cosas. Al día siguiente más de un millón de ciudadanos bajaban al Paseo del Prado para manifestar en silencio su solidaridad contra el terrorismo, bajo la fina lluvia. Unos días después estuve en un taller del trabajo pero sentí que no me aportaba especialmente, por lo que pedí disculpas, diciendo que no me encontraba bien por los eventos recientes, y me fui. Por las mañanas había militares armados en el andén. Pensaba que no era necesario después del atentado, ya que aumentaba la sensación de inseguridad e inquietud, aunque imagino que lo hicieron para dar seguridad a los pasajeros. Me pregunto ¿cómo habrán notado los neozelandeses los cambios en la sociedad y dentro de ellos mismos? A veces las sensaciones son más un afloramiento de emociones que algo que se pueda razonar. Podría ser ira, miedo, tristeza. Como un trauma físico, llevaría tiempo en curarse.

Como familiar la situación debe ser especialmente difícil. Un amigo de Christchurch, Michael O’Dempsey compartió en su Facebook, ‘Cuando tuvimos el terremoto no fue algo personal, no tenía malicia. Solo sucedió y punto. Podíamos explicarlo a nuestros hijos. El fusilamiento en la mezquita es mucho más complejo de racionalizar por la maldad e intención que tiene.’ Pienso en mi juventud en Nueva Zelanda, creciendo en Culverden (cerca de Christchurch), Dunedin y la capital Wellington antes de mudarnos a Londres en 1981 cuando tenía casi doce años. Nuestra parroquia dio cobijo y apoyo a refugiados de Vietnam y Camboya que huían de la violencia y pobreza en sus propios países. En mi otro poema de la antología More of Us, ‘El juego de ajedrez’ reflexiono sobre mi amigo camboyano, un chico de mi edad, y sobre cómo aprendió inglés mientras jugábamos. Él y sus hermanos habían perdido a su padre y se jugaban la vida buscando alimentos frescos mientras vivieron en un campo de refugiados en la frontera vietnamita. ¿Quizás los niños se adaptan mejor que los adultos a los cambios y retos? Pero a lo mejor no, los niveles de violencia a la que son expuestos en la televisión, las redes sociales, a través de los amigos y los videojuegos—donde las imágenes son cada vez más realistas, además de que estar en internet conlleva sus propios peligros para los niños—han aumentado al igual que las incidencias de las enfermedades relacionadas con la ansiedad infantil. Para los padres es cada vez más complicado procesar toda la información y comprender un paisaje internacional interconectado con sus múltiples esferas políticas, corporativas y religiosas, y muchas veces no tienen el tiempo ni los recursos para ayudar a los niños llegar a un entendimiento del mundo. Como me comentó mi hermana, ‘muchas veces no entendemos el mundo nosotros mismos, entonces ¿cómo podemos explicar esto a nuestros hijos sin añadir a sus niveles de ansiedad?’ Quizás no debemos intentar a racionalizar lo irracional, pero solo decir a nuestros hijos cómo nos sentimos y escucharles mientras expresan cómo se sienten. La empatía con el otro, sea con nuestra familia o con culturas ajenas, es una habilidad valiosa que podemos practicar.

Charles Olsen leyendo More of Us (Landing Press, 2019). Foto: Jacquie Ordóñez

Recientemente fui a la presentación en Madrid del libro Metamba Miago (Nuestras raíces) de un grupo de escritoras afro-españolas. La psicóloga Marjorie Paola Hurtado habló de la ansiedad que se puede acumular a lo largo de muchos años en la vida de una persona negra en una sociedad predominantemente blanca a través de los comentarios constantes o al margen, desde la pregunta repetitiva de ¿de dónde eres?, hasta comentarios abiertamente racistas. Todas las escritoras tenían sus propias experiencias para contar. Ella nos explicó que esta ansiedad no se cura en un día sino que requiere trabajo y apoyo. Alguna gente se acostumbra tanto a la situación, que dejan de prestarle atención hasta que algo extremo ocurre causando un ataque de pánico del cual no pueden entender la causa. Esto me sonó. Tuve un periodo agudo de ataques de pánico poco después de terminar la carrera universitaria mientras vivía en Camden Town en Londres. Parecieron salir de la nada y para mí no era obvio su detonante (ni siquiera entendía lo que eran). La causa subyacente de la ansiedad o la propensión a ella fue aún más difícil comprender. En aquel entonces leí unos cuantos libros sobre los ataques de ansiedad que, aunque daban consejos, no me aportaban mucho más que el hecho de saber que otros habían pasado por lo mismo. Veo con consternación que el libro Headlands: New Stories of Anxiety (Tierras de la cabeza: Nuevas historias de la Ansiedad) editado por Victoria University Press, 2018, como los libros que leí en los 90, tiene una portada que desata la ansiedad. Me gusta el humor negro pero—editoriales: tomen nota—no estaba en un buen lugar cuando tenía que leer aquellos libros y el texto desequilibrado o las imágenes deprimentes no decían exactamente ‘relajate, estoy para ayudarte.’ Pero me desvío del tema. Llevo tiempo queriendo escribir sobre mi propia experiencia pero quizás necesitaba un empujón. El desencadenante para escribir pudo ser el atentado de Nueva Zelanda, la perspicacia de la psicóloga Hurtado, o un amigo confesando hace poco su dependencia a los tranquilizantes, pero como decía, lo he tenido en mente cada tanto durante años y al final quizás hubiera surgido en mi escritura de cualquier manera.

La semana antes de ir en bicicleta desde Surrey a Londres por los parques, me caí de de mi bici en la calle principal de Camden después de ver la película Pulp Fiction en el cine. Un coche había salido de repente haciéndome caer bajo mi bici y estaba aterrorizado por el coche de detrás, que tuvo que frenar en seco para no atropellarme. Llegué a casa con cortes en la piel y la ropa rota y ensangrentada. Me arreglé como pude y seguí con mi vida. El domingo siguiente, cuando regresé a Londres desde la casa de mis padres, el aire aquella noche estaba cargado, bochornoso con truenos secos, y no podía dormir.

Mi compañero de piso en Murray Mews estaba en su habitación al otro lado del descansillo. Rupert.

‘Éramos cuatro compartiendo una casa en Camden Town, incluido Charles. Habíamos terminado la carrera en Bellas Artes en la Universidad de Middlesex y estábamos con los preparativos para una gran exposición en Londres (Whiteleys Atrium en Bayswater). Una mañana estaba en mi cuarto cuando creí oír la voz de Charles débilmente pidiendo ‘ayuda’. Fui a investigar y le encontré arrodillado en el suelo. Estaba pálido y parecía tener dificultad para respirar. Conocía a Charles como una persona tranquila y capaz, por lo que me preocupé inmediatamente. Le pregunté si llamar a la ambulancia y me contestó ‘sí’. Por lo que pudimos hablar hasta la llegada de la ambulancia no entendí lo que había pasado y creo que Charles tampoco. Sintió un alivio cuando llegó la ambulancia. Charles ya había podido levantarse y moverse, pero siguió mal.’

En la ambulancia me hicieron un electrocardiograma y no encontraron nada mal. En el hospital la enfermera me hizo un masaje del estómago, pienso por si fueran gases de indigestión que pueden provocar la sensación de pinchazos en la región del corazón. Me dijo que no habían encontrado nada y me dio de alta. Nunca había ido en una ambulancia y no pensé en cómo iba a regresar a casa después. Creo recordar que tenía cambio para el autobús núm. 24. En el camino a casa pensé en lo que había pasado durante la noche. Había encontrado dificultad para respirar y el corazón me daba saltos. Fui a la ventana abierta para respirar mejor y refrescarme, volviendo a la cama para intentar dormir. Por la mañana luchaba para respirar y llamé pidiendo ayuda cuando los dedos de los manos se doblaron fuertemente sobre las palmas—como si mi cuerpo hubiera empezado a apagarse—y al no poder forzarlas a abrirse. Más tarde me he enterado de que el espasmo del músculo fue producido por una reducción en niveles de calcio y fosfato a causa de una hiperventilación aguda. No entendía lo que me había ocurrido, pero fue el principio de mis ataques de pánico.

Externamente parecía que estaba bien. Podía seguir con la vida. La gente no sabia cómo responder ni ayudarme. Leí sobre la agorafobia, sobre situaciones que provocaban ataques de pánico en otros. Los míos no encajaban en este diagnóstico. Sentía una ansiedad constante, aunque estuviera seguro sentado en el sofá en casa mirando la tele. Al pasear por la calle sentía las extremidades pesadas como si fuera avanzando por una salsa espesa. También bostezaba constantemente con la sensación de que nunca conseguía el suficiente aire. El siguiente miércoles hice un esfuerzo por ir a las clases de baile de swing que daban mi hermana y mi cuñado en el Ayuntamiento de Ealing en la zona oeste de Londres. Casi no llegué, porque me había vuelto de repente tan sensible y consciente de todas las extrañas sensaciones en mi cuerpo que cada sacudida del tren del metro parecía mi propio corazón dando vuelcos. A cada momento sentía que me iba a romper. Tuve que racionalizar que seguía de pie y que el metro es siempre hostil, y a mitad de camino me autoconvencí de que volver iba a ser la más larga de las dos opciones. Cada decisión la tomé con la amenaza del regreso del pánico, y fue agotador.

No recuerdo con claridad todos los detalles ahora, ya que todo esto ocurrió hace veinticinco años. Quisiera aportar tranquilidad a la gente diciendo que las cosas mejoraron con el tiempo una vez que empecé a entender la situación, y diría que pasaron unos dos años antes de poder sentir que los ataques de pánico eran cosa del pasado. Es curioso que la nostalgia que sentí después de dejar Nueva Zelanda también duró aproximadamente dos años.

Al principio fui a varios médicos, tanto de cabecera como en salas de urgencias. Después de eliminar la posibilidad de problemas del corazón me recomendaron respirar en una bolsa de papel para ayudar a calmar la hiperventilación. La mayoría de los médicos se centraban en la ansiedad y recetaban medicinas para aplacarla. Un médico me recitó beta bloqueantes, que me decía usaban los violinistas profesionales para estabilizar el pulso de la mano y afianzar la primera nota del concierto. Siempre he dudado del uso de drogas para tratar los síntomas en lugar de buscar a la causa subyacente, por lo que no tomé los beta bloqueantes hasta recibir otra opinión, en este caso de una médica india que me dedicó su tiempo para preguntarme sobre mi dieta, patrón de sueño, etcétera. Me comentó que la noche de mi primer ataque hacía mucho bochorno y el aire estaba inusualmente cargado, y muchas personas en Londres habían estado afectadas por problemas respiratorios. Pienso en esto ahora al ver que el problema del asma en jóvenes y el peligro de los gases de los vehículos está en las noticias en el Reino Unido. Ella me dio la sensación de control sobre mi propio cuerpo diciendo que no me haría daño al menos probar la medicina y ver su afecto. No noté mucho aparte de que supuestamente son para ralentizar el corazón, y por tanto estuve excesivamente pendiente de los latidos de mi corazón. Otro médico me recitó tres días de diazepam, que me ayudo a superar la exposición en Bayswater. Estoy feliz de que solo fuera tres días porque me dejó en una nube de algodón y, aunque podía funcionar, vi lo fuera de mi, y del mundo, que estaba cuando lo tomaba.

Charles Olsen pintando en óleo La Súndari (2005), que fue expuesto en la galería Saatchi, London

En los primeros días y semanas vivía con una ansiedad constante que a menudo se convertía en una ola de pánico agudo. En una ocasión me fui a ver una exposición en la galería Hayward en Londres, y a mitad de recorrido empecé a tener problemas al respirar. Sentía que me estaba asfixiando, con palpitaciones y el mundo cerrándose a mi alrededor, pero estaba en una galería amplia, y siendo entre semana casi no había gente. Encontré una sala de lectura donde pude sentarme y esperar a que se pasara la ansiedad, pero no se fue. Entendía que era un ataque de pánico pero no era capaz de resolver la desconexión entre una actividad que disfrutaba y la ansiedad que sentía, que seguía aumentando. Finalmente salí de la galería y solo una vez fuera, paseando en el aire fresco por el río, empezó a reducirse poco a poco la ansiedad.

Un par de semanas después, haciendo tiempo antes de encontrarme con una amiga, abrí un libro que encontré en una caja en la puerta de una tienda de segunda mano y leí la primera frase de A Voice Through a Cloud (Una voz a través de una nube) de Denton Welch:

‘Una fiesta de Pentecostés, cuando era estudiante de arte en Londres, me subí a mi bicicleta dejando mi habitación en Croom’s Hill para ir a la casa parroquial de mi tío en Surrey.’

Denton Welch escribió el libro después de un accidente grave de bicicleta que le dejó paralizado y luchaba sin éxito para terminarlo antes de su fallecimiento. Me intrigó y asustó a la vez. Vivía aún bajo una nube a miedo, y al encontrar tantos paralelismos con mi propia vida en la primera frase solo podía esperar que mi accidente en bici y los ataques de pánico no darían eco a su historia también. (Siempre he querido escribir un libro que abra con la misma frase modificada para reflejar mi propia verdad.) Poco después del inicio de los ataques de pánico me crucé con una anciana en la calle, quien me comentó al pasar que tenía un año maravilloso por delante y que lo aprovechara. En mi mente llena de miedo interpreté que decía que solo me quedaba un año de vida. Sentí un alivio secreto al terminar el año y ver que la vida seguía.

Un día, mi padre, desconcertado y sin saber cómo ayudarme tras haber estado cogiéndome la mano mientras yo intentaba dormir, pidió la ayuda de una colega del hospital. Ella me habló, me escuchó y me dio un masaje de reflexología podal. El masaje me ayudó a soltar el miedo por un momento, y aquella tarde, aunque sentía dolor en el pecho, tenía la sensación de que era un dolor de sanación, más que de destrucción, y fui capaz de dejarlo estar y dormir bien por primera vez en semanas. Me habló del proceso por el cual tiene que pasar el cuerpo para sanarse después de un trauma y de que es normal que llevase su tiempo. Hablamos del impacto de mi accidente de bici la semana anterior al comienzo de los ataques. A diferencia de un accidente previo por el que estuve en el hospital durante unos días, donde recibí cuidados, en esta ocasión me fui a casa y no tuve ningún apoyo después del shock del accidente. Tenía muchas otras preocupaciones por aquel entonces, pero tenía sentido que este hecho me podría haber llevado al extremo. Quizás la abeja o avispa tuvo algo que ver también.

Otro libro que me encontré mucho más adelante en una tienda de beneficencia fue Breathing free (Respirando libre) de Teresa Hale. Basado en el trabajo del ucranio Konstantin Buteyko, presenta un programa de ejercicios de respiración para reducir la tendencia a la hiperventilación, basado en una respiración lenta y poco profunda. Es muy parecido al control respiratorio que necesitas para el buceo cuando lo último que quieres hacer cuando encuentres problemas debajo del agua es actuar desde el pánico. Lo encontré muy útil para devolverme a un patrón regular e inconsciente de respiración que estaba desbaratado por la ansiedad. La respiración la damos por hecho pero el ansia de respirar profundo e hiperventilar cuando sientes miedo, aunque necesaria en caso de lucha o huida, no es de utilidad cuando la causa del miedo es el propio miedo.

Charles Olsen durante la III Beca Poética Internacional SxS Antonio Machado, Segovia 2018. Foto: Lilián Pallares

Recientemente tuve el placer de ver por segunda vez la fantástica obra de teatro El Percusionista de Gorsy Edú de Guinea Ecuatorial, en el Teatro del Barrio en Madrid. Es una obra emotiva y evocadora que comparte filosofías ancestrales, la tradición oral, y la importancia de la música en la cultura africana. En un momento de la obra el percusionista relata cómo su abuelo contaba la manera en que cada instrumento representa una personalidad distinta. El udu africano es un cuenco grande de percusión que él describe como alguien muy tranquilo, paciente y excelente en resolver conflictos. Puedes llenar el cuenco con mucha agua pero cuando lo llenas y se desborda entonces ¡cuidado! Esta imagen me llegó. La felicidad, la tristeza, el enojo y el miedo son emociones comunes pero puede estar en la naturaleza de muchos de nosotros restar importancia o ignorar las emociones negativas. El contexto cultural y la educación también juegan un rol, al añadir capas de complejidad o represión. Esta efusión de, en mi caso, ansiedad, es una oportunidad de reflexionar sobre el trasfondo en el que hemos construido nuestras vidas y revaluar la relación con nosotros mismos.

El desequilibrio de los ataques de pánico nos brinda la oportunidad de encontrar una compasión más profunda con nosotros mismos. A veces esto surge en mi pintura y escritura, como en mi poema ‘Peregrino’ que evoca los cinco sentidos en un caminante solitario, mostrando la unidad en cada detalle, expresado en la palabra ‘nos’. Hasta un recipiente vacío puede contar su historia.

Peregrino

Exhalo neblina,

filetes de lodo pegados a las suelas,

campestre estatua en medio de un preludio de cencerros.

Levanta su mirada un borrego,

huele el aire y vuelve a pastar.

Lluvia fina.

Una bolsa del súper

clavada en el alambre entre mechones de lana.

Como ermitaños, solitarios árboles

aguantan un antiguo viento.

Nos abraza el horizonte.

Vacío, susurra el plástico.

Hace años padecí una crisis.

Despertó algo en mi.

Cuando nuestro mundo, el personal o el mundo en su conjunto, de repente se vuelve frágil, nos reta a mirarnos a nosotros mismos—a reconocer que algo ha cambiado—y dar el paso en un viaje de aprendizaje y conocimiento. Estas situaciones irracionales—la violencia del terrorismo en lugares he vivido o la inestabilidad de mi propia ansiedad—se han vuelto parte de mi, parte de mi camino, otra capa en mi trabajo creativo, un camino a una compasión más amplia. Desde el atentado en Christchurch, me han alentado y perturbado los puntos de vista que he leído de amigos en Nueva Zelanda. Mientras procesamos nuestras reacciones como país espero que aprendamos a reflexionar sobre nuestras ideas, sobre cómo impactan en otros, y cómo contribuyen a una comunidad más compasiva y solidaria o una sociedad más miedosa y fragmentada. No podemos dar al botón de reiniciar el mundo. Como digo en la linea final del poema que mencioné al principio del artículo, ‘Cuando meno los esperas’:

Salvarse no siempre consiste en salir con vida.

Notas

‘Cuando menos los esperas’ y ‘El partido de ajedrez’ están en inglés en la colección More of Us, editado por Adrienne Jansen, Landing Press, Wellington. ‘Peregrino’ forma parte de la colección bilingüe Antípodas editada por Huerga y Fierro en España.Charles Olsen se mudo a España atraído por su interés en los pintores como Velázquez y Goya y para estudiar la guitarra flamenca. Artista, realizador y poeta, sus pinturas han sido expuestas en el Reino Unido, Francia, Nueva Zelanda y España, y ha publicado dos poemarios bilingües Sr Citizen (Amargord, 2011) y Antípodas (Huerga y Fierro, 2016). Su cortometraje La danza de los pinceles recibió el segundo premio en el I Festival Flamenco de Cortometrajes en España y sus videopoemas han sido seleccionados para festivales internacionales y destacados en revistas como Moving Poems, Poetry Film Live y Atticus Review. En 2018 fue becado con la III Beca Poética Internacional SxS Antonio Machado y ha recibido la XIII distinción Poetas de Otros Mundos.

November 20, 2021

Videopoesía en Portugal y España – Festival VideoBardo

[ Jump to English – Festival VideoBardo ]

EL FESTIVAL INTERNACIONAL DE VIDEOPOESÍA, VideoBardo, celebra sus 25 años con una amplia programación, tanto presencial en Buenos Aires, Argentina, como online, desde el 25 del noviembre al 3 de diciembre. Participo el 29 de noviembre cuando presentarán el documental Videopoesía en Portugal y España.

Ver la programación completo y enlaces para las presentaciónes en: VIDEOBARDO 25 AÑOS

29 de noviembre

3pm, Argentina [19h en España] POÉTICA DE SARA TREMLETT (UK), Conversatorio con Sarah Tremlett sobre la publicación de su libro The Poetics of Poetry Film (Intellect Books, UK) 2021 y el rol de la videopoesía y el film poético hoy.

4pm, Argentina [20h en España] Videopoesía en Portugal y España POR CHARLES OLSEN Para el 25º Festival Internacional de Videopoesía, VideoBardo, Charles Olsen presenta entrevistas y una muestra de obras de videopoetas de Portugal y España incluidos en el libro The Poetics of Poetry Film (Intellect Books, UK) 2021. Además muestra unos videopoemas relacionados con su ensayo 'Poetic Sound' (Sonido poético) del mismo libro. – Incluye entrevistas con Alexandre Braga, Celia Parra, Agustín Fernández Mallo, Alejandro Céspedes, Eduardo Yagüe y Belén Gache. También una muestra de fragmentos de videopoemas de Santiago Parres, Jordan T. Caylor, David Argüelles Redondo, Jokin Pascual, Sándor M. Salas y Ángel Guinda, y una introducción de Sarah Tremlett, editora del libro The Poetics of Poetry Film.

(Disponible online hasta el final del festival el 3 de diciembre)

Fotograma del título del vídeo.

THE INTERNATIONAL VIDEOPOETRY FESTIVAL, VideoBardo, celebrates 25 years with an extensive programme, both in person in Buenos Aires, Argentina, and online, from 25 November to 3 December. I participate on 29 November with the presentation of the documentary Videopoesía en Portugal y España (Videopoetry in Portugal and Spain).

See the complete programme and find links to the presentations here: VIDEOBARDO 25 YEARS

VideoBardo Festival Poster

29 November

3pm, Argentina [6pm UK] POETICA by SARA TREMLETT (UK), Conversation with Sarah Tremlett about the publication of The Poetics of Poetry Film (Intellect Books, UK) 2021 and the role of poetry film and poetics in film today.

4pm, Argentina [7pm UK] Videopoetry in Portugal and Spain by CHARLES OLSEN. For the 25th International Videopoetry Festival, VideoBardo, Charles Olsen presents interviews and a selection of work by poetry filmmakers of Portugal and Spain included in the book The Poetics of Poetry Film (Intellect Books, UK) 2021. Además muestra unos videopoemas relacionados con su ensayo 'Poetic Sound' (Sonido poético) del mismo libro. – It includes interviews with Alexandre Braga, Celia Parra, Agustín Fernández Mallo, Alejandro Céspedes, Eduardo Yagüe and Belén Gache. Also fragments of poetry films by Santiago Parres, Jordan T. Caylor, David Argüelles Redondo, Jokin Pascual, Sándor M. Salas and Ángel Guinda, and an introduction by Sarah Tremlett, editor of The Poetics of Poetry Film.

(Available online until the close of the festival on 3 December)

November 19, 2021

La danza de los pinceles (Trailer)

La danza de los pinceles

Partiendo de las pinturas de Picasso – en especial “Las Señoritas de Aviñón” y sus obras del año 1907 – se representa a través de la danza flamenca la estética geométrica y multifacética de este artista.

Una pintora enfrentada al lienzo vacío busca la inspiración en la música flamenca. A compás de bulería, la artista se adentra en una ensoñación en la que elementos como abanicos, la pintura, el baile y la naturaleza se mezclan de una manera sorprendente para llegar a un final inesperado y poético.

Conocer más sobre el corto en ladanzadelospinceles.blogspot.com

The Dance of the Brushes

Starting from the paintings of Picasso – in particular "Les Demoiselles d’Avignon" and his works of 1907 – the film presents through flamenco dance the geometric and multifaceted aesthetic of this artist.

An artist, confronted with an empty canvas looks for inspiration in flamenco music. The rhythm of a 'bulería' transports us into a dream in which elements such as fans, paint, dance and nature are mixed together in a surprising way leading to an unexpected and poetic end.

Learn more about the short film in ladanzadelospinceles.blogspot.com

November 18, 2021

Articles on 'Love in the Time of Covid'

During 2020/2021 a number of pieces I was involved with making and writing were included in the project Love in the Time of Covid, edited by Witi Ihimaera and Michelle Elvy. These include an article on the creation of our collaborative te reo poetry film Noho Mai, a recital of Lilián's poem ‘Llanto Congelado’ (Frozen Cry), a presentation of poetry by our niece Mia Gill, and a reflection on mask wearing inspired by my photograph 'Covid Glam'.

You will find links to each of these here.

November 17, 2021

Los Tejados. The story of a painting.

(Read time: 20 min)

I was exploring a new part of Madrid on a recent run, past the Railway Museum up into the Enrique Tierno Galván park – refreshing sprinklers on both both sides of the main path, and then up around the edge of the outdoor amphitheatre. Rounding the back of the amphitheatre I saw the distinctive blue Mahou (A Spanish beer) building and realised I was running in my painting 'Los Tejados' (The Roofs).

Here is the story about a poem, a piece of music, a poetry film, and various collaborations that have come together during the process of working on this painting.

'How many brushstrokes of how many colours

to paint an urban landscape?'

April 2009

CLIMBING, PHOTOGRAPHS AND A NEW CANVAS

I was living in an attic flat in the neighbourhood of Lavapies, Madrid, and had been working on a series of oil paintings on cardboard using stereoscopic transparencies I’d taken at my grandfather’s home in New Zealand a couple of years before I moved to Spain. Before that I was focussed on portraits and had painted the flamenco dancer Miryam Chachmany in ‘La Súndari’ which was later to be shown at the Saatchi Gallery in London. This was painted on old wooden window shutters salvaged from a skip. I liked the idea of alternative painting supports as they carry their own history or in the case of cardboard boxes they were light and freely available, especially living in a street full of wholesale shops.

My room in the shared flat was small but had a high oak-beamed ceiling and a wonderful smooth white wall opposite the door. I’d sometimes climb onto the beams to look out the Velux window. With the high-density housing in Madrid you’re lucky to have a decent view. I’ve had views onto drab interior patios where a neighbour’s radio blares from an open window all day, or onto a narrow noisy street with car horns tooting as trucks unload and a police car attempts to clear a way with its wailing.

March 2009

It was the spring of 2009 when I stretched a large canvas and primed it with gesso. I had climbed out the window and taken photos of the view from the roof. I was drawn to the scale and composition of one of the images. It wasn’t a particularly remarkable day, clouds softened the shadows and the tower blocks on the horizon caught the sun. The distant haze gave an even blue-grey tone to the sky so one isn’t sure if it is cloud or sky.

I blew up the image to the same size as the canvas, creating a ‘photocopy’ in black and white with the basic lines that I could print out onto A4 sheets and stick together, and I transferred it to the canvas with carbon paper before blocking in tonal areas with thin washes of paint to give something to work on and to help fix the image.

'My previous work had moved between abstract and figurative and into photo-based work but this was on a scale and level of detail I’d not tackled before.'

And then began the more detailed work, starting on the left-hand side and working brick by brick and roof tile by roof tile. I was painting with tiny size two Kolinsky sable brushes and the work required a lot of concentration. My previous work had moved between abstract and figurative and into photo-based work but this was on a scale and level of detail I’d not tackled before, except in the smaller Still-life, Le Plessis-Robinson (1999).

It is a learning process and often one isn’t really aware what it is you’re learning until you are able to look back over the whole process, so I'll leave these reflections for later.

March 2009

A POETIC AND MUSICAL HIATUS

A decade later and I’m living in another attic flat a little further up the hill. The canvas has been stored facing the wall for a number of years and I begin to wonder if I’ll ever finish it. In the meantime I publish two collections of poetry, including the first poem I wrote in Spanish, Paisaje Urbano (Urban Landscape), in Sr Citizen (2011), which gives a nod to the canvas with the lines: 'how many brushstrokes of how many colours/to paint an urban landscape?' and it closes with: ‘the landscape I paint is from a past/that no longer exists the same./of this I’ll make something new.’

Towards the end of winter in February of 2011 my friend Ben Webster Williams emailed me a track he’d written with Paul Higgins back in 2004 that had it’s own story of struggle in finding its place, and he asked me: ‘we wondered if you would like to get involved in this… it’s not playing guitar… it’s using your poetry on music.’ It was very exciting for me. Paisaje Urbano seemed to fit the music really well and there was space for the poem in both Spanish and English. We made a mix with my voice which sounded great.

I had begun experimenting with poetry film and made my first short film La danza de los pinceles (The Dance of the Brushes). I was offered a temporary studio to work on a large commission for the shop deflamenco in Madrid where I also exhibited a series of flamenco inspired paintings and photographs. I gave recitals combining poetry with flamenco dance and piano in Venice and Madrid. I ran an online Spanish poetry competition for six years. My creativity was moving in different directions and the painting remained untouched against the wall.

June 2018

I ask myself perhaps it was the flat? The low sloping ceiling with one north-facing Velux window didn’t let in sufficient light or in the summer too much, so only certain hours of the day and times of the year I could appreciate the canvas as a whole – but then I once had a studio in a dark old barn, the small windows covered in dust and spider’s webs, and I had to rig up fluorescent daylight tubes to see anything. I wonder if it is the low ceiling or maybe the lack of space to be able to stand back to view the work properly? – but what about my favourite studio in the cramped out-house one summer at my granddad’s in Nelson? – although there I was able to take my paints out into the garden sometimes. I was also concerned about painting in oils in a confined space. Half the year it is freezing in Madrid and I didn’t want to work with turpentine with the window closed. I have worked before with lashings of turpentine on my abstract paintings and it can be pretty potent even in a spacious studio.

The funny thing is, the track I’d recorded with Ben was also in a hiatus, and then out of the blue, some six years down the road at the end of summer 2018, he emails me this amazing new version with drums he and Andrew Marvell had recorded on Andy’s narrow boat on the Hackney Marshes. Andy had really upped the game with his groove and I listened over and again on repeat. In the intervening years I’d had more experience of reciting my poems on stage and I’d also bought a decent microphone for my filming so I recorded a new version of the poem. The track had some digital cello elements that we thought needed a live sound too. Some things just need to find their moment I guess – my neighbour, Camilo Bosso, is the bass player in the group O Sister!, but despite hearing the deep jazzy tones drifting pleasantly through our adjoining wall it took me a few days to click the jigsaw piece into place and think to ask him. Camilo and I recorded a high cello-like line on the bass and I also recorded a short piece on flamenco guitar for the end of the track, although I’d not studied the guitar for a number of years. I sent these off to Ben…

May 2019

AUDIOVISUAL TIMEWARP

Ever since I’d written Paisaje Urbano and begun to make poetry films I’d had in mind to make a film of this poem. It is set in the neighbourhood I lived in and I had begun to make stop-motion photographs of tree shadows moving across a white wall or the sun on a wrought-iron window frame and I still have these in a folder on an old hard drive. With the new version of the music to use in the soundtrack I began thinking again of filming and how I would do it. Being a very personal poem I liked the idea of filming myself in the local neighbourhood. And at this point occurs another big jump in the story.

Back in 2005, when I was studying flamenco guitar and working with flamenco dancer Miryam Chachmany, I met Joanna Wivell. She was intrigued by our passion for flamenco and how we'd come to Spain to study and she began following our story for a possible documentary. We filmed during the local summer street festivities, playing flamenco guitar, during the opening of one of my exhibitions, visiting local characters, and she captured some wonderful moments. Time moved on and the documentary didn’t materialize, but at some point in the intervening years Joanna had given me the mini-DV tapes and I had managed to transfer them to a hard drive where they sat half-forgotten. Now, almost 15 years later I realised I was sitting on the material for the poetry film and only needed to ask Joanna’s permission and begin editing…

CRA Matadero, January 2020

A NEW STUDIO AND A PANDEMIC

And here, a big ellipsis to 2020. I'd begun work again on the canvas, first in my flat and then in January 2020, moving into the amazing studio space of the Centre for Artist Residencies at the Matadero Madrid where Lilián and I were awarded an arts residency. Then the Covid-19 lockdown came into force in Madrid mid-March and the painting was inaccessible for two months (locked in the Matadero), and then I was able to retrieve it and continue painting in my flat.

Cover art. Webster. Urban Landscape/Paisaje Urbano (feat. Charles Olsen)

We finished the music track. Ben made a last minute dash up to London the last day before the lockdown happened in England, to spend time with the very creative Alex McGowan at Space Eko East fine-tuning the final mix. We were really excited for Urban Landscape/Paisaje Urbano (feat. Charles Olsen) to finally be on its way to all digital platforms for its release on 24 July 2020 as part of the Webster Collective. [Available here: Urban Landscape/Paisaje Urbano (feat. Charles Olsen) – single, Webster Collective]

The poetry film of the same name is also in the bag and has been submitted to poetry and short film festivals with the log line: ‘I live the days in dreams that never end.’ Poet Charles Olsen studies flamenco guitar and savours the processions and street parties of his neighbourhood in Madrid, and tells of lost love. It received its premiere in 2021 in Festival Nudo in Barcelona. You can watch the trailer here:

TECHNICAL NOTES ON PAINTING

And the painting Los Tejados was still in progress. There were a couple of details where I felt the light was wrong. One of the difficulties of painting in a realism style is in how our eyes compensate for and adapt to contrasts of light and dark. A camera will over- or under-expose for bright or dark areas unless it has a High Dynamic Range option which can itself often look strange to the eye, whereas our eyes can appreciate the fine details of a shady interior and the sunlit view from the window in a split-second. In a painting the visual understanding is all about the adjacent forms providing visual clues and context – a shiny metal vent doesn’t come to life until the roof tiles behind it are painted – and there is a tendency to add more white, or light, to shady areas. The eye interprets white objects as white even though they are in shadow and may actually be dark grey or even another colour (see the 2015 Guardian article: Is The Dress blue and black or white and gold? The answer lies in vision psychology). Taking a black and white photo of the painting can help in discerning these visual compensations. In reality there are only about four tiny areas of pure white straight from the tube in the entire painting.

I love videos of work in progress. These are great for Instagram artists. It was enough trying to focus on painting without planning out and setting up the filming of the whole process on and off over the years. I did nevertheless share a small section of painting a couple of tiles which you can see here: @colsenart.

(Image made using Google Maps)

I recently looked on Google Earth for the approximate view so I could identify some of the buildings and features. It is interesting to see how space is compressed by the camera lens and some buildings appear much closer than they are in reality and to realize that there are hundreds of buildings hidden behind those we can see.

(Image made using Google Maps)

When working on the painting in the CRA Matadero sometimes visitors would ask me why I was working on the canvas upside-down. There are a number of reasons but I’d just mention one or two and they’d go away happy. I change the rotation of the canvas depending in part on what was most comfortable – if I was standing, or seated. In my flat with the low ceiling I used a child’s plastic chair for the low parts. It was also to avoid leaning on already painted areas so if I got paint on my hand I wouldn’t smudge it over the painted area, and if I happened to drop a brush it would fall against the unpainted canvas. Another reason is that by turning both the reference photo and canvas upside-down or on their side you are less conditioned by what you know is there because the shapes become unfamiliar, making it easier to paint what you see rather than what you think you see.

Photo by Jacqueline Quintero

When I started painting I had the original photograph on the computer screen, but further down the line I got an iPad and it became much easier to work with the photo. I can blow up a section to the same size as the painting, rotating it as needed, and use a music stand to hold the iPad at the correct height next to where I am working. There is something beautifully poetic about the music stand in front of the canvas. I love the simplicity and adaptability of this setup. Working with the backlit image on the iPad also helps provide a constant brightness of image and colour. I took the photo on my previous digital camera and it doesn’t have a particularly high resolution, however I like the fact that the image is not overly detailed so I don’t feel constrained by perfection.

Other details I like about the materials are: because I’m using such small brushes I keep a mix of turpentine and linseed oil, to thin the oil paint, in a small Spanish ‘Carmencita’ herb or spice jar and have cut the holes together to make one hole big enough to dip the brush in. I can flip the lid closed to avoid any fumes from evaporating turpentine.

Instead of a plank of wood I use the side of a biscuit box which makes a very lightweight palette that is comfortable to hold. I scrape off dried paint rather than cleaning it so that I keep the reference of the colours I’ve been using, and I’ve used the same palette for the whole painting. For my brushes I love my jar of old lentils with a cling-film cover held with a rubber band to stop them spilling, and small holes so each brush stands in place where you insert it and doesn’t get paint on its neighbour.

I’m using a mix of Lucas and Michael Harding oil paints. The Michael Harding paints are more expensive but they have such an intense colour that a little touch, of say cadmium red, will go a very long way. This careful use of paint has meant I have used much less paint overall than in one of my abstract works of a similar scale and generally my work area is tidier – I’ve even managed to work in everyday clothes and not get paint all over them.

Detail, May 2019

WHEN IS A CITY FINISHED?

Working on the painting over such an extended period of time I began to wonder if I would ever finish it; and to question what purpose the painting served. The reaction from the few people who have seen it at different points has made it worthwhile. Seeing someone stand for minutes before the painting and contemplating the details is particularly satisfying. Some people have commented, even though it was barely half-finished, that they liked it as it was.

'For me painting is not about finding a style of one’s own but rather a way of engaging with the world.'

Personally it has been an ongoing journey, even a meditation, of discovery. A day working on a tiny square of beautiful colours that could be an abstract painting in itself, or finding a way to naturally depict an old weathered wall or a sun-bleached turquoise canopy; these can be very satisfying as is the excitement of seeing elements in the foreground really pop out of the canvas once the areas behind them are painted.

Still-life, Le Plessis-Robinson (1999)

In my painting Still-life, Le Plessis-Robinson (1999) [See above] I used a technique where a fan brush is dragged through the wet paint to roughly blend the colours which creates a wonderful optical effect where the eye recomposes the image into a very natural heightened realism. I considered doing this here but the scale, and the continuous large ares of fine detail, as well as working in the very dry air of Madrid which makes keeping the paint sufficiently wet complicated, especially as I was working when I could between classes. I was close to missing some classes because I was so engrossed in the painting and I’d have to change clothes, grab my things and jump on my kick-scooter down the hill to the class in five minutes.

I decided to follow the textures of each surface, enjoy the challenges they brought, and tried to keep the light touch of the pale blue hut on the roof of the building in the left foreground. This was my starting point; my first question and answer. Working on such a scale I had to make a choice regarding my approach and follow it through. I am reminded of Sir Stanley Spencer’s paintings in the Stanley Spencer Gallery, Cookham, such as the unfinished Christ Preaching at Cookham Regatta (1952-59), where we can appreciate his working process, starting in one part of the canvas and completing each section piece by piece following his initial drawing. I also love the work in progress photographs of the marvellous Spanish photorealist artist Jesús Lozano Saorin whose watercolours reflect a loving eye for light and texture, starting with detailed drawings before working from weathered walls towards the fine details. In this sense the painting is finished once the intention is complete, in my case the intention as it is conceived in the pale blue hut. At the same time, it is dificult to appreciate an area until it is seen in the context of the surrounding area of of the whole, and there are a handful of areas I knew I wanted to return to; answers that came to me during the many hours of looking.

On my art foundation course in Farnham back in 1991 I remember a visiting artist talking about his work and after showing a large pointallist painting he’d done he recommended all artists should do at least one in this style. This is about taking you out of your comfort zone and forcing you to really consider light and colour in a new way. As an artist who has often used large brushes, poured paint and washes, rags, wax and other materials, using only size 2 to 4 brushes on a large canvas has been a big challenge.

A WINDOW ONTO THE WORLD

For me painting is not about finding a style of one’s own but rather a way of engaging with the world. I love how the story of the painting has run in parallel with other creative projects. How one day I find myself running in the painting, how the painting now hangs on our wall in a flat where we only have windows in the ceiling and only see sky and it is like a window onto our neighbouhood, how it has influenced a series of much looser, abstract watercolours, and how its story continues.

Open Studio in CRA, Matadero Madrid, July 2021

In the final two months of the Residency in Matadero Madrid, I was working on a new poetry film with collaborations from friends, artists and poetry filmmakers. Inspired by my poem 'La exposción' (The Exhibition), it is an irreverant take on the art world with a childlike viewpoint and the final scene features the Argentinian actor Ignacio Kowalski looking at the painting 'Los Tejados' in a gallery. The final piece has been submitted to poetry film festivals and has yet to receive its premiere but you can watch the trailer here:

The painting currently hangs beside the piano, so the nearest roof tiles often catch my eye as I'm playing, and if the light is right they draw my eye into their heavy terracota textures that echo the tiles on the apartments further away, and up into the distant trees and towerblocks on the horizon.

Pensamientos lentos

- Charles Olsen's profile

- 8 followers