Lucy Pollard-Gott's Blog, page 9

September 28, 2012

"Elementary" premiere on CBS--a very new Holmes and Watson keep the faith

Although I planned to write next about Andrew Motion's Silver, his excellent sequel to Treasure Island, I can't resist commenting on the premiere episode of "Elementary" on CBS last night, with its inspired pairing of Jonny Lee Miller, as recovering addict Sherlock Holmes, and Lucy Liu as Joan Watson, ex-surgeon, now hired by Holmes's father as a companion to oversee his son's first months out of rehab. It is inspired because their chemistry together is strong from the start, both a clash and an attraction of personalities, and not primarily sexual. This clever justification for Watson’s shadowing Holmes’s every move, accompanying him on a case when they have barely met, gives the series a solid premise to build on; by the end of the first episode, there are already hints that the relationship is growing beyond duty and grudging acceptance to one of mutual interest, usefulness, and even caring.

In his indispensable essay “Fan Fictions: On Sherlock Holmes,” Michael Chabon observes that Sir Arthur Conan Doyle’s early Holmes (in the first two novels A Study in Scarlet and The Sign of Four) was presented as more resolutely strange and nonconformist. He suggests that Holmes was the product of the same Victorian duality that made a Dorian Gray or Jekyll and Hyde. However, as the author turned to writing his detective short stories, some of these darker traits dropped away and a seemingly more conservative (if never quite conventional) Holmes emerged.

“beginning in 1891 with the first great short story, “A Scandal in Bohemia,” Conan Doyle abandoned most of the louche, Wildean touches with which he had initially encumbered the character of Holmes. The outré personal habits, the vampiric hours, the drug use, the willfully outrageous ignorance of ‘useless facts,’ such as the order of the solar system or contemporary politics, gave way to a more conventional and cozy sort of eccentricity.” (from Chabon’s collected essays, Maps and Legends, p. 33)

Readers may argue how much of this side of Holmes truly dropped away—perhaps it merely receded into the background and emerged when the stresses brought about the necessary conditions (especially true of the drug use). Most writers and adapters of the characters since Conan Doyle have cherished one or more of these eccentricities in their raw state, and “Elementary” is no exception. Its Holmes has quite literally just emerged from drug rehabilitation and he appears to Watson for the first time in an apparently untamed state—shirtless, unshaven, twitchy, restless, and recalcitrant. While he is dismissing the necessity of Joan Watson’s services as “babysitter,” he is also keen to deductively size her up, almost as a compulsive tic rather than a power play. It is a subtle performance and the generous closeups permit ample appreciation of the restraint and skill of both actors. Naturally, he talks very, very fast. Both updated Sherlocks—this one in New York and the BBC’s Sherlock in today’s London—operate on the premise that speed of expression and mental powers are perfectly correlated (something I would take issue with, in practice). However, it certainly works as a sign to their Watsons and to their audiences at home that one must snap to, pay attention, and try to keep up!

Owing to his recent treatment, this Holmes is in a somewhat vulnerable state, something he shares with Darlene Cypser’s young Sherlock in her Consulting Detective series. Both are in crisis for medical reasons and both are at odds with a disappointed father. In “Elementary” it rankles Holmes that upon relocating to New York from London, he must accept living in the “worst” of the several apartments his father owns. Fortunately, solving difficult criminal cases proves highly therapeutic (true for Cypser’s Holmes as well). This is very fortunate for the TV viewer too, because a murder comes in his way very quickly and is admirably resolved within the single episode—I hope this pattern continues, whatever development occurs across episodes for the continuing characters. Aidan Quinn as Captain Gregson of the NYPD is an outstanding touch, though appearing only briefly, and I hope to see his role grow.

A great deal is accomplished in this first episode. Because their relationship begins on a note of distrust, Holmes and Watson must each win some measure of trust and respect from the other, enough for the relationship to persist until the next episode (and then the next). It is fascinating to see how this Watson wins Holmes’s admiration, and this incident leads to the only uncharacteristic move his character makes—claiming to anticipate an outcome that came as quite a surprise to him. I cannot think of an example in the canon where Holmes deliberately claimed he’d deduced something he hadn’t. (Perhaps others can think of an instance I’ve overlooked.) His admission to Watson about this begins paradoxically to kindle in her a greater faith in him, even if it is only the hope that he is actually human.

Michael Chabon, in the same essay I mentioned earlier, takes Conan Doyle to task for not having enough faith in his own character at the outset, perhaps always underestimating his merit and worth as the greatest project of his life. To me, this matter of faith in Holmes is very central. Conan Doyle’s very ambivalence about Holmes may be one answer to the riddle of why Sherlock Holmes was, is, and has remained so compelling. The drama of Holmes needing to win faith and trust from his clients, from skeptical police, even from the occasional perpetrator, is enacted over and over with each new story and novel in the canon, and again with each new pastiche or fresh realization of the character in film or television. Holmes keeps winning readers’ and viewers’ faith, whether his creator could credit their loyal belief in him or not. Authors from Conan Doyle onward have Holmes demonstrate his powers with such force and clarity, he makes believers out of skeptics of all description. A show like “Elementary” really only gets one opening chance to inspire faith that this Holmes can be and do what any “real” Holmes should be and do. Watson is our guide, leading us to wonder and then to believe in him. In the course of this first episode, Dr. Joan Watson learned enough to stay by her Holmes, and I think viewers will keep returning too.

Reference:

Michael Chabon, "Fan Fictions: On Sherlock Holmes" in Maps and Legends. Open Road, 2011 [kindle edition]. (Original work published 2008)

Related post:

Coming of Age as a Detective: Sherlock Holmes in "The Consulting Detective Trilogy Part I"

September 8, 2012

Coming of Age as a Detective: Sherlock Holmes in “The Consulting Detective Trilogy Part I”*

The Consulting Detective Trilogy Part I: University by Darlene A. Cypser, Foolscap & Quill, 2012.

Following her masterful debut novel, The Crack in the Lens (which I reviewed last year), Darlene Cypser is continuing her psychologically rich Sherlockian prequels in a new Consulting Detective Trilogy. After young Sherlock’s first run-in with Professor Moriarty (in the previous novel), one which left him bereft of his first love, Violet Rushdale, and almost unhinged from his sanity, the first installment of the trilogy finds him still making only a precarious recovery at home but embarking nevertheless on his university studies at Cambridge, where he must cope with further dramatic events that will form his character and fully reveal his life’s purpose.

The budding field of psychiatry as a branch of medicine is beginning to make its appearance in the latter part of the century, and Cypser takes full advantage of the possibilities in the early chapters of the novel. Sherlock continues to be physically and emotionally at his lowest ebb as the novel begins. He is suffering from flashbacks of Violet’s death and a cycle of obsessive recrimination and anxiety that we would not hesitate to label post-traumatic stress disorder, or PTSD, today. But more than 100 years ago, a sufferer risked commitment in an asylum that had little hope to offer except for palliative physical care, restraint from self-harm, and the rudiments of counseling for the lucky few who encountered a capable doctor. While Sherlock struggled at home, he began receiving visits from Dr Mackenzie, one such capable doctor summoned from the asylum to consult about Sherlock’s condition. While Moriarty was nemesis to Sherlock in the first book, in this new novel, Dr Mackenzie fills the role of an anti-Moriarty, proving to be not only a trusted physician but a crucial ally and mentor as Sherlock’s attraction to the sciences—and the science of detection—increases.

However, the doctor’s experimental remedy for Sherlock’s “traumatic neurasthenia,” namely, an injected solution of cocaine, will dog him throughout his life, first as blessing, and then as a persistent and secret curse. But here, in the beginning, it served its purpose, suppressing his anxiety and panic attacks, while fueling his intellectual excitement: “Sherlock’s loquaciousness [on the train with Mycroft for a holiday] varied as the influence of the drug varied, fading out as it did. His true nature lay somewhere between the extremes” (p. 113).

The novel hits its stride as Sherlock barely begins to find his, as a new member of Sidney Sussex College, which is pictured in foreboding darkness on the book’s attractive cover. And darkness is surely still haunting Sherlock as he begins his studies in mathematics, living out of college in private rooms. His panic attacks can still be triggered by anything that reminds him of Violet’s death (such as an early snowfall) or unduly taxes his nerves. Fortunately, he has a capable and devoted companion in young Jonathan Beckwith, who accompanies his charge to Cambridge as servant, as fencing pupil and partner (when Sherlock is strong enough), but above all as Sherlock’s only friend, besides Dr. Mackenzie, for many months of self-imposed isolation. (Jonathan is so engaging and colorful a character that Cypser has announced plans for another mystery trilogy from his point of view.)

Ironically, Sherlock’s first close friendship at university, with classmate Victor Trevor, begins quite unpromisingly with a dangerous bite from Trevor’s dog. (We also glimpse the aloof Reginald Musgrave and his coolness to Holmes.) But the friendship with Victor develops rapidly during Sherlock’s convalescence; he visits daily and introduces Sherlock to pipe-smoking, which incidentally provides a stimulant and practical alternative to cocaine. At this point, Cypser deftly interpolates her own retelling of “The Adventure of the Gloria Scott” from the Conan Doyle canon; as it is told retrospectively by Holmes, this account intersects with the chronology of Cypser’s story of Holmes’s university days. While he spends a holiday with Victor Trevor and Trevor’s father, events precipitate his first solution of a mystery, one calling forth the unique observational and deductive skills he has already demonstrated casually to the amazement of his classmates. But the stakes soon rise to life and death, and Holmes begins to see—as he later affirms—“perhaps I’m not your average man.” He is destined to pursue no average calling but to create his own profession, as the world’s first consulting detective.

It is the business of this novel to unfold for us Sherlock’s early exercise of talent in a new mystery at the university (which I won’t reveal), as well as his change of academic direction, suiting all his studies to those sciences which will inform and develop his detection skills and build his arsenal of knowledge. Though not aiming to become a police detective, he is fascinated by police detectives’ work and gets into some nasty scrapes trying to observe it first hand, much too closely for their comfort. With his prodigious memory, he begins to be a serious student of crime and collects accounts of it. Mycroft sends him clippings from the London papers, and with satisfaction, the reader watches the genesis of his alphabetic file of crime reports, which will come in handy so often, tantalize the reader with names and cases Watson hasn’t yet narrated, and fill Mrs. Hudson with consternation when the mass of riffled clippings is strewn everywhere at 221b…

But all that lies in the future. For now, Sherlock is a young man not quite 20 who must deal with authority figures still wielding much power over his life, whether they are university officials or his own implacable father. It is also the business of this novel to show how he will assert his own choice and begin to follow his “line in life”—which will also be his lifeline, drawing him back from his darkest moods.

In a recent New York Times essay, “The Art of the Sequel,” author Andrew Motion considered the proliferation of literary sequels and prequels, even including an “I, Sherlock Holmes” on his facetious list of typical sequel titles. Based on his analysis of some of the most effective sequels, such as Tom Stoppard’s Rosenkrantz and Guildenstern Are Dead (a sequel to Hamlet) or Jean Rhys’s Wide Sargasso Sea (a prequel to Jane Eyre), he offered some pointers to would-be fashioners of such works. Although it is a tremendous advantage that the characters are already familiar, and possibly beloved, a successful sequel or prequel “allows us to think afresh about characters whose fame can otherwise make them feel inaccessible to new interpretations.” In other words, it should attempt to add something more to what we already know about them, perhaps surprise us by its revelations, even when we believe we already know a character—say, a complex hero such as Holmes—very well indeed. Moreover, sequel-writing presupposes a certain playfulness, artfully inserting familiar references, while deploying ingenuity to put the character to a new test. No matter how much we revere a character, Motion argues, “something more than imitation is far more honoring.”

Both of Darlene Cypser’s Sherlockian prequels to date fulfill these criteria. Her pastiches are not imitation but exploration, and she shows the confidence and command of the canon which enable her to inquire more deeply into Holmes’s formative psychology. Her latest novel has the hallmarks of a true bildungsroman—a coming-of-age novel—about a sensitive protagonist, often a youngest son, who suffers loss and undergoes a series of difficult trials that lead to mastery of self and ultimately to maturity. It can encompass education or other training disciplines, artistic development, and apprenticeships (Goethe’s Wilhelm Meister’s Apprenticeship being the classic example). At the end, the hero understands himself better, knows how he might move beyond self to contribute to the world, and is both ready and equipped to do it.

Through psychological insight, swift movement of the plot via effective dialogue, and consistent characterization, Cypser has fashioned a bildungsroman for young Sherlock with great skill. As goddessinsepia writes, with her usual grace and clear perception,

“By the end of Cypser’s second novel, the reader stands in full knowledge and awareness of the man before them, and you wonder how you missed it, so understated was his development. Where previously there was only the merest hint of the man that would become the Great Detective, Sherlock Holmes now stands tall, assembled, if not yet fully-formed.” [See the rest of her insightful review at her blog Better Holmes and Gardens]

My interest and absorption in this story never flagged, a tribute to Cypser’s high level of craft. I also enjoyed her humor, for example, when a fellow student observed Sherlock’s easy victory over an opponent who had challenged him to a match with unfamiliar fencing sticks, the bemused spectator remarked, “I don’t think the weapon matters. Holmes could probably thrash any of us with a teaspoon.” This first installment of The Consulting Detective Trilogy works as mystery fiction, but more than that, it emerges as a fully rounded novel of Sherlock Holmes.

*Note: FTC disclosure. I received a complimentary review copy of this novel. The opinions I’ve expressed are, of course, my own.

In my next post, I will review Andrew Motion’s own sequel, Silver: Return to Treasure Island .

Related post:

On Sherlock Holmes and Superman: Catching Them at the Crossroads

Further links:

The Consulting Detective Trilogy—Excerpts

BOOK REVIEW: “The Consulting Detective Trilogy Part I: University [goddessinsepia’s review]

Coming of Age as a Detective: Sherlock Holmes in "The Consulting Detective Trilogy Part I"*

The Consulting Detective Trilogy Part I: University by Darlene A. Cypser, Foolscap & Quill, 2012.

Following her masterful debut novel, The Crack in the Lens (which I reviewed last year), Darlene Cypser is continuing her psychologically rich Sherlockian prequels in a new Consulting Detective Trilogy. After young Sherlock’s first run-in with Professor Moriarty (in the previous novel), one which left him bereft of his first love, Violet Rushdale, and almost unhinged from his sanity, the first installment of the trilogy finds him still making only a precarious recovery at home but embarking nevertheless on his university studies at Cambridge, where he must cope with further dramatic events that will form his character and fully reveal his life’s purpose.

The budding field of psychiatry as a branch of medicine is beginning to make its appearance in the latter part of the century, and Cypser takes full advantage of the possibilities in the early chapters of the novel. Sherlock continues to be physically and emotionally at his lowest ebb as the novel begins. He is suffering from flashbacks of Violet’s death and a cycle of obsessive recrimination and anxiety that we would not hesitate to label post-traumatic stress disorder, or PTSD, today. But more than 100 years ago, a sufferer risked commitment in an asylum that had little hope to offer except for palliative physical care, restraint from self-harm, and the rudiments of counseling for the lucky few who encountered a capable doctor. While Sherlock struggled at home, he began receiving visits from Dr Mackenzie, one such capable doctor summoned from the asylum to consult about Sherlock’s condition. While Moriarty was nemesis to Sherlock in the first book, in this new novel, Dr Mackenzie fills the role of an anti-Moriarty, proving to be not only a trusted physician but a crucial ally and mentor as Sherlock’s attraction to the sciences—and the science of detection—increases.

However, the doctor’s experimental remedy for Sherlock’s “traumatic neurasthenia,” namely, an injected solution of cocaine, will dog him throughout his life, first as blessing, and then as a persistent and secret curse. But here, in the beginning, it served its purpose, suppressing his anxiety and panic attacks, while fueling his intellectual excitement: “Sherlock’s loquaciousness [on the train with Mycroft for a holiday] varied as the influence of the drug varied, fading out as it did. His true nature lay somewhere between the extremes” (p. 113).

The novel hits its stride as Sherlock barely begins to find his, as a new member of Sidney Sussex College, which is pictured in foreboding darkness on the book’s attractive cover. And darkness is surely still haunting Sherlock as he begins his studies in mathematics, living out of college in private rooms. His panic attacks can still be triggered by anything that reminds him of Violet’s death (such as an early snowfall) or unduly taxes his nerves. Fortunately, he has a capable and devoted companion in young Jonathan Beckwith, who accompanies his charge to Cambridge as servant, as fencing pupil and partner (when Sherlock is strong enough), but above all as Sherlock’s only friend, besides Dr. Mackenzie, for many months of self-imposed isolation. (Jonathan is so engaging and colorful a character that Cypser has announced plans for another mystery trilogy from his point of view.)

Ironically, Sherlock’s first close friendship at university, with classmate Victor Trevor, begins quite unpromisingly with a dangerous bite from Trevor’s dog. (We also glimpse the aloof Reginald Musgrave and his coolness to Holmes.) But the friendship with Victor develops rapidly during Sherlock’s convalescence; he visits daily and introduces Sherlock to pipe-smoking, which incidentally provides a stimulant and practical alternative to cocaine. At this point, Cypser deftly interpolates her own retelling of “The Adventure of the Gloria Scott” from the Conan Doyle canon; as it is told retrospectively by Holmes, this account intersects with the chronology of Cypser’s story of Holmes’s university days. While he spends a holiday with Victor Trevor and Trevor’s father, events precipitate his first solution of a mystery, one calling forth the unique observational and deductive skills he has already demonstrated casually to the amazement of his classmates. But the stakes soon rise to life and death, and Holmes begins to see—as he later affirms—“perhaps I’m not your average man.” He is destined to pursue no average calling but to create his own profession, as the world’s first consulting detective.

It is the business of this novel to unfold for us Sherlock’s early exercise of talent in a new mystery at the university (which I won’t reveal), as well as his change of academic direction, suiting all his studies to those sciences which will inform and develop his detection skills and build his arsenal of knowledge. Though not aiming to become a police detective, he is fascinated by police detectives’ work and gets into some nasty scrapes trying to observe it first hand, much too closely for their comfort. With his prodigious memory, he begins to be a serious student of crime and collects accounts of it. Mycroft sends him clippings from the London papers, and with satisfaction, the reader watches the genesis of his alphabetic file of crime reports, which will come in handy so often, tantalize the reader with names and cases Watson hasn’t yet narrated, and fill Mrs. Hudson with consternation when the mass of riffled clippings is strewn everywhere at 221b…

But all that lies in the future. For now, Sherlock is a young man not quite 20 who must deal with authority figures still wielding much power over his life, whether they are university officials or his own implacable father. It is also the business of this novel to show how he will assert his own choice and begin to follow his “line in life”—which will also be his lifeline, drawing him back from his darkest moods.

In a recent New York Times essay, “The Art of the Sequel,” author Andrew Motion considered the proliferation of literary sequels and prequels, even including an “I, Sherlock Holmes” on his facetious list of typical sequel titles. Based on his analysis of some of the most effective sequels, such as Tom Stoppard’s Rosenkrantz and Guildenstern Are Dead (a sequel to Hamlet) or Jean Rhys’s Wide Sargasso Sea (a prequel to Jane Eyre), he offered some pointers to would-be fashioners of such works. Although it is a tremendous advantage that the characters are already familiar, and possibly beloved, a successful sequel or prequel “allows us to think afresh about characters whose fame can otherwise make them feel inaccessible to new interpretations.” In other words, it should attempt to add something more to what we already know about them, perhaps surprise us by its revelations, even when we believe we already know a character—say, a complex hero such as Holmes—very well indeed. Moreover, sequel-writing presupposes a certain playfulness, artfully inserting familiar references, while deploying ingenuity to put the character to a new test. No matter how much we revere a character, Motion argues, “something more than imitation is far more honoring.”

Both of Darlene Cypser’s Sherlockian prequels to date fulfill these criteria. Her pastiches are not imitation but exploration, and she shows the confidence and command of the canon which enable her to inquire more deeply into Holmes’s formative psychology. Her latest novel has the hallmarks of a true bildungsroman—a coming-of-age novel—about a sensitive protagonist, often a youngest son, who suffers loss and undergoes a series of difficult trials that lead to mastery of self and ultimately to maturity. It can encompass education or other training disciplines, artistic development, and apprenticeships (Goethe’s Wilhelm Meister’s Apprenticeship being the classic example). At the end, the hero understands himself better, knows how he might move beyond self to contribute to the world, and is both ready and equipped to do it.

Through psychological insight, swift movement of the plot via effective dialogue, and consistent characterization, Cypser has fashioned a bildungsroman for young Sherlock with great skill. As goddessinsepia writes, with her usual grace and clear perception,

“By the end of Cypser’s second novel, the reader stands in full knowledge and awareness of the man before them, and you wonder how you missed it, so understated was his development. Where previously there was only the merest hint of the man that would become the Great Detective, Sherlock Holmes now stands tall, assembled, if not yet fully-formed.” [See the rest of her insightful review at her blog Better Holmes and Gardens]

My interest and absorption in this story never flagged, a tribute to Cypser’s high level of craft. I also enjoyed her humor, for example, when a fellow student observed Sherlock’s easy victory over an opponent who had challenged him to a match with unfamiliar fencing sticks, the bemused spectator remarked, “I don’t think the weapon matters. Holmes could probably thrash any of us with a teaspoon.” This first installment of The Consulting Detective Trilogy works as mystery fiction, but more than that, it emerges as a fully rounded novel of Sherlock Holmes.

*Note: FTC disclosure. I received a complimentary review copy of this novel. The opinions I’ve expressed are, of course, my own.

In my next post, I will review Andrew Motion’s own sequel, Silver: Return to Treasure Island .

Related post:

On Sherlock Holmes and Superman: Catching Them at the Crossroads

Further links:

The Consulting Detective Trilogy—Excerpts

BOOK REVIEW: “The Consulting Detective Trilogy Part I: University [goddessinsepia’s review]

Coming of Age as a Detective: Sherlock Holmes in “The Consulting Detective Trilogy Part I”*

The Consulting Detective Trilogy. Part I: University by Darlene A. Cypser, Foolscap & Quill, 2012.

Following her masterful debut novel, The Crack in the Lens (which I reviewed last year), Darlene Cypser is continuing her psychologically rich Sherlockian prequels in a new Consulting Detective Trilogy. After young Sherlock’s first run-in with Professor Moriarty (in the previous novel), one which left him bereft of his first love, Violet Rushdale, and almost unhinged from his sanity, the first installment of the trilogy finds him still making only a precarious recovery at home but embarking nevertheless on his university studies at Cambridge, where he must cope with further dramatic events that will form his character and fully reveal his life’s purpose.

The budding field of psychiatry as a branch of medicine is beginning to make its appearance in the latter part of the century, and Cypser takes full advantage of the possibilities in the early chapters of the novel. Sherlock continues to be physically and emotionally at his lowest ebb as the novel begins. He is suffering from flashbacks of Violet’s death and a cycle of obsessive recrimination and anxiety that we would not hesitate to label post-traumatic stress disorder, or PTSD, today. But more than 100 years ago, a sufferer risked commitment in an asylum that had little hope to offer except for palliative physical care, restraint from self-harm, and the rudiments of counseling for the lucky few who encountered a capable doctor. While Sherlock struggled at home, he began receiving visits from Dr Mackenzie, one such capable doctor summoned from the asylum to consult about Sherlock’s condition. While Moriarty was nemesis to Sherlock in the first book, in this new novel, Dr Mackenzie fills the role of an anti-Moriarty, proving to be not only a trusted physician but a crucial ally and mentor as Sherlock’s attraction to the sciences—and the science of detection—increases.

However, the doctor’s experimental remedy for Sherlock’s “traumatic neurasthenia,” namely, an injected solution of cocaine, will dog him throughout his life, first as blessing, and then as a persistent and secret curse. But here, in the beginning, it served its purpose, suppressing his anxiety and panic attacks, while fueling his intellectual excitement: “Sherlock’s loquaciousness [on the train with Mycroft for a holiday] varied as the influence of the drug varied, fading out as it did. His true nature lay somewhere between the extremes” (p. 113).

The novel hits its stride as Sherlock barely begins to find his, as a new member of Sidney Sussex College, which is pictured in foreboding darkness on the book’s attractive cover. And darkness is surely still haunting Sherlock as he begins his studies in mathematics, living out of college in private rooms. His panic attacks can still be triggered by anything that reminds him of Violet’s death (such as an early snowfall) or unduly taxes his nerves. Fortunately, he has a capable and devoted companion in young Jonathan Beckwith, who accompanies his charge to Cambridge as servant, as fencing pupil and partner (when Sherlock is strong enough), but above all as Sherlock’s only friend, besides Dr. Mackenzie, for many months of self-imposed isolation. (Jonathan is so engaging and colorful a character that Cypser has announced plans for another mystery trilogy from his point of view.)

Ironically, Sherlock’s first close friendship at university, with classmate Victor Trevor, begins quite unpromisingly with a dangerous bite from Trevor’s dog. (We also glimpse the aloof Reginald Musgrave and his coolness to Holmes.) But the friendship with Victor develops rapidly during Sherlock’s convalescence; he visits daily and introduces Sherlock to pipe-smoking, which incidentally provides a stimulant and practical alternative to cocaine. At this point, Cypser deftly interpolates her own retelling of “The Adventure of the Gloria Scott” from the Conan Doyle canon; as it is told retrospectively by Holmes, this account intersects with the chronology of Cypser’s story of Holmes’s university days. While he spends a holiday with Victor Trevor and Trevor’s father, events precipitate his first solution of a mystery, one calling forth the unique observational and deductive skills he has already demonstrated casually to the amazement of his classmates. But the stakes soon rise to life and death, and Holmes begins to see—as he later affirms—“perhaps I’m not your average man.” He is destined to pursue no average calling but to create his own profession, as the world’s first consulting detective.

It is the business of this novel to unfold for us Sherlock’s early exercise of talent in a new mystery at the university (which I won’t reveal), as well as his change of academic direction, suiting all his studies to those sciences which will inform and develop his detection skills and build his arsenal of knowledge. Though not aiming to become a police detective, he is fascinated by police detectives’ work and gets into some nasty scrapes trying to observe it first hand, much too closely for their comfort. With his prodigious memory, he begins to be a serious student of crime and collects accounts of it. Mycroft sends him clippings from the London papers, and with satisfaction, the reader watches the genesis of his alphabetic file of crime reports, which will come in handy so often, tantalize the reader with names and cases Watson hasn’t yet narrated, and fill Mrs. Hudson with consternation when the mass of riffled clippings is strewn everywhere at 221b…

But all that lies in the future. For now, Sherlock is a young man not quite 20 who must deal with authority figures still wielding much power over his life, whether they are university officials or his own implacable father. It is also the business of this novel to show how he will assert his own choice and begin to follow his “line in life”—which will also be his lifeline, drawing him back from his darkest moods.

In a recent New York Times essay, “The Art of the Sequel,” author Andrew Motion considered the proliferation of literary sequels and prequels, even including an “I, Sherlock Holmes” on his facetious list of typical sequel titles. Based on his analysis of some of the most effective sequels, such as Tom Stoppard’s Rosenkrantz and Guildenstern Are Dead (a sequel to Hamlet) or Jean Rhys’s Wide Sargasso Sea (a prequel to Jane Eyre), he offered some pointers to would-be fashioners of such works. Although it is a tremendous advantage that the characters are already familiar, and possibly beloved, a successful sequel or prequel “allows us to think afresh about characters whose fame can otherwise make them feel inaccessible to new interpretations.” In other words, it should attempt to add something more to what we already know about them, perhaps surprise us by its revelations, even when we believe we already know a character—say, a complex hero such as Holmes—very well indeed. Moreover, sequel-writing presupposes a certain playfulness, artfully inserting familiar references, while deploying ingenuity to put the character to a new test. No matter how much we revere a character, Motion argues, “something more than imitation is far more honoring.”

Both of Darlene Cypser’s Sherlockian prequels to date fulfill these criteria. Her pastiches are not imitation but exploration, and she shows the confidence and command of the canon which enable her to inquire more deeply into Holmes’s formative psychology. Her latest novel has the hallmarks of a true bildungsroman—a coming-of-age novel—about a sensitive protagonist, often a youngest son, who suffers loss and undergoes a series of difficult trials that lead to mastery of self and ultimately to maturity. It can encompass education or other training disciplines, artistic development, and apprenticeships (Goethe’s Wilhelm Meister’s Apprenticeship being the classic example). At the end, the hero understands himself better, knows how he might move beyond self to contribute to the world, and is both ready and equipped to do it.

Through psychological insight, swift movement of the plot via effective dialogue, and consistent characterization, Cypser has fashioned a bildungsroman for young Sherlock with great skill. As goddessinsepia writes, with her usual grace and clear perception:

“By the end of Cypser’s second novel, the reader stands in full knowledge and awareness of the man before them, and you wonder how you missed it, so understated was his development. Where previously there was only the merest hint of the man that would become the Great Detective, Sherlock Holmes now stands tall, assembled, if not yet fully-formed.” [See the rest of her insightful review at her blog Better Holmes and Gardens]

My interest and absorption in this story never flagged, a tribute to Cypser’s high level of craft. I also enjoyed her humor, for example, when a fellow student observed Sherlock’s easy victory over an opponent who had challenged him to a match with unfamiliar fencing sticks, the bemused spectator remarked, “I don’t think the weapon matters. Holmes could probably thrash any of us with a teaspoon.” This first installment of The Consulting Detective Trilogy works as mystery fiction, but more than that, it emerges as a fully rounded novel of Sherlock Holmes.

*Note: FTC disclosure. I received a complimentary review copy of this novel. The opinions I’ve expressed are, of course, my own.

Related post:

· On Sherlock Holmes and Superman: Catching Them at the Crossroads

Further links:

· The Consulting Detective Trilogy—Excerpts

· BOOK REVIEW: “The Consulting Detective Trilogy Part I: University [goddessinsepia’s review]

Coming of Age as a Detective: Sherlock Holmes in "The Consulting Detective Trilogy Part I"*

The Consulting Detective Trilogy. Part I: University by Darlene A. Cypser, Foolscap & Quill, 2012.

[image error]

Following her masterful debut novel, The Crack in the Lens (which I reviewed last year), Darlene Cypser is continuing her psychologically rich Sherlockian prequels in a new Consulting Detective Trilogy. After young Sherlock’s first run-in with Professor Moriarty (in the previous novel), one which left him bereft of his first love, Violet Rushdale, and almost unhinged from his sanity, the first installment of the trilogy finds him still making only a precarious recovery at home but embarking nevertheless on his university studies at Cambridge, where he must cope with further dramatic events that will form his character and fully reveal his life’s purpose.

The budding field of psychiatry as a branch of medicine is beginning to make its appearance in the latter part of the century, and Cypser takes full advantage of the possibilities in the early chapters of the novel. Sherlock continues to be physically and emotionally at his lowest ebb as the novel begins. He is suffering from flashbacks of Violet’s death and a cycle of obsessive recrimination and anxiety that we would not hesitate to label post-traumatic stress disorder, or PTSD, today. But more than 100 years ago, a sufferer risked commitment in an asylum that had little hope to offer except for palliative physical care, restraint from self-harm, and the rudiments of counseling for the lucky few who encountered a capable doctor. While Sherlock struggled at home, he began receiving visits from Dr Mackenzie, one such capable doctor summoned from the asylum to consult about Sherlock’s condition. While Moriarty was nemesis to Sherlock in the first book, in this new novel, Dr Mackenzie fills the role of an anti-Moriarty, proving to be not only a trusted physician but a crucial ally and mentor as Sherlock’s attraction to the sciences—and the science of detection—increases.

However, the doctor’s experimental remedy for Sherlock’s “traumatic neurasthenia,” namely, an injected solution of cocaine, will dog him throughout his life, first as blessing, and then as a persistent and secret curse. But here, in the beginning, it served its purpose, suppressing his anxiety and panic attacks, while fueling his intellectual excitement: “Sherlock’s loquaciousness [on the train with Mycroft for a holiday] varied as the influence of the drug varied, fading out as it did. His true nature lay somewhere between the extremes” (p. 113).

The novel hits its stride as Sherlock barely begins to find his, as a new member of Sidney Sussex College, which is pictured in foreboding darkness on the book’s attractive cover. And darkness is surely still haunting Sherlock as he begins his studies in mathematics, living out of college in private rooms. His panic attacks can still be triggered by anything that reminds him of Violet’s death (such as an early snowfall) or unduly taxes his nerves. Fortunately, he has a capable and devoted companion in young Jonathan Beckwith, who accompanies his charge to Cambridge as servant, as fencing pupil and partner (when Sherlock is strong enough), but above all as Sherlock’s only friend, besides Dr. Mackenzie, for many months of self-imposed isolation. (Jonathan is so engaging and colorful a character that Cypser has announced plans for another mystery trilogy from his point of view.)

Ironically, Sherlock’s first close friendship at university, with classmate Victor Trevor, begins quite unpromisingly with a dangerous bite from Trevor’s dog. (We also glimpse the aloof Reginald Musgrave and his coolness to Holmes.) But the friendship with Victor develops rapidly during Sherlock’s convalescence; he visits daily and introduces Sherlock to pipe-smoking, which incidentally provides a stimulant and practical alternative to cocaine. At this point, Cypser deftly interpolates her own retelling of “The Adventure of the Gloria Scott” from the Conan Doyle canon; as it is told retrospectively by Holmes, this account intersects with the chronology of Cypser’s story of Holmes’s university days. While he spends a holiday with Victor Trevor and Trevor’s father, events precipitate his first solution of a mystery, one calling forth the unique observational and deductive skills he has already demonstrated casually to the amazement of his classmates. But the stakes soon rise to life and death, and Holmes begins to see—as he later affirms—“perhaps I’m not your average man.” He is destined to pursue no average calling but to create his own profession, as the world’s first consulting detective.

It is the business of this novel to unfold for us Sherlock’s early exercise of talent in a new mystery at the university (which I won’t reveal), as well as his change of academic direction, suiting all his studies to those sciences which will inform and develop his detection skills and build his arsenal of knowledge. Though not aiming to become a police detective, he is fascinated by police detectives’ work and gets into some nasty scrapes trying to observe it first hand, much too closely for their comfort. With his prodigious memory, he begins to be a serious student of crime and collects accounts of it. Mycroft sends him clippings from the London papers, and with satisfaction, the reader watches the genesis of his alphabetic file of crime reports, which will come in handy so often, tantalize the reader with names and cases Watson hasn’t yet narrated, and fill Mrs. Hudson with consternation when the mass of riffled clippings is strewn everywhere at 221b…

But all that lies in the future. For now, Sherlock is a young man not quite 20 who must deal with authority figures still wielding much power over his life, whether they are university officials or his own implacable father. It is also the business of this novel to show how he will assert his own choice and begin to follow his “line in life”—which will also be his lifeline, drawing him back from his darkest moods.

In a recent New York Times essay, “The Art of the Sequel,” author Andrew Motion considered the proliferation of literary sequels and prequels, even including an “I, Sherlock Holmes” on his facetious list of typical sequel titles. Based on his analysis of some of the most effective sequels, such as Tom Stoppard’s Rosenkrantz and Guildenstern Are Dead (a sequel to Hamlet) or Jean Rhys’s Wide Sargasso Sea (a prequel to Jane Eyre), he offered some pointers to would-be fashioners of such works. Although it is a tremendous advantage that the characters are already familiar, and possibly beloved, a successful sequel or prequel “allows us to think afresh about characters whose fame can otherwise make them feel inaccessible to new interpretations.” In other words, it should attempt to add something more to what we already know about them, perhaps surprise us by its revelations, even when we believe we already know a character—say, a complex hero such as Holmes—very well indeed. Moreover, sequel-writing presupposes a certain playfulness, artfully inserting familiar references, while deploying ingenuity to put the character to a new test. No matter how much we revere a character, Motion argues, “something more than imitation is far more honoring.”

Both of Darlene Cypser’s Sherlockian prequels to date fulfill these criteria. Her pastiches are not imitation but exploration, and she shows the confidence and command of the canon which enable her to inquire more deeply into Holmes’s formative psychology. Her latest novel has the hallmarks of a true bildungsroman—a coming-of-age novel—about a sensitive protagonist, often a youngest son, who suffers loss and undergoes a series of difficult trials that lead to mastery of self and ultimately to maturity. It can encompass education or other training disciplines, artistic development, and apprenticeships (Goethe’s Wilhelm Meister’s Apprenticeship being the classic example). At the end, the hero understands himself better, knows how he might move beyond self to contribute to the world, and is both ready and equipped to do it.

Through psychological insight, swift movement of the plot via effective dialogue, and consistent characterization, Cypser has fashioned a bildungsroman for young Sherlock with great skill. As goddessinsepia writes, with her usual grace and clear perception:

“By the end of Cypser’s second novel, the reader stands in full knowledge and awareness of the man before them, and you wonder how you missed it, so understated was his development. Where previously there was only the merest hint of the man that would become the Great Detective, Sherlock Holmes now stands tall, assembled, if not yet fully-formed.” [See the rest of her insightful review at her blog Better Holmes and Gardens]

My interest and absorption in this story never flagged, a tribute to Cypser’s high level of craft. I also enjoyed her humor, for example, when a fellow student observed Sherlock’s easy victory over an opponent who had challenged him to a match with unfamiliar fencing sticks, the bemused spectator remarked, “I don’t think the weapon matters. Holmes could probably thrash any of us with a teaspoon.” This first installment of The Consulting Detective Trilogy works as mystery fiction, but more than that, it emerges as a fully rounded novel of Sherlock Holmes.

*Note: FTC disclosure. I received a complimentary review copy of this novel. The opinions I’ve expressed are, of course, my own.

Related post:

· On Sherlock Holmes and Superman: Catching Them at the Crossroads

Further links:

· The Consulting Detective Trilogy—Excerpts

· BOOK REVIEW: “The Consulting Detective Trilogy Part I: University [goddessinsepia’s review]

July 25, 2012

“To Be Continued”: Scheherazade and the Arabian Nights (2)

Arabian Nights and Days: A Novel by Naguib Mahfouz, trans. by Denys Johnson-Davies, Doubleday, 1995. (Originally published 1979 in Arabic)

Whatever Gets You Through the Night: A Story of Sheherezade and the Arabian Entertainments by Andrei Codrescu, Princeton University Press, 2011.

“Shéhérezade” (ballet, 1910), choreography by Mikhail Fokine, The Kirov Celebrates Nijinsky [DVD], Kultur, 2002.

Rimsky-Korsakov: Scheherazade/ Russian Easter Overture [CD]. The Atlanta Symphony Orchestra, Robert Spano, conducting. Telarc, 2001.

In my previous post, reviewing Marina Warner’s exciting new work of cultural criticism, Stranger Magic, I promised to discuss a few examples of retellings that continue to expand Scheherazade’s legacy. The corpus of such retellings and variations is truly a measureless “sea of stories,” to borrow a bit of the title from Salman Rushdie’s Haroun and the Sea of Stories, an illustrious example of this genre of storytelling art. One reader of my review of Warner, Ray Wilcockson, cited Robert Louis Stevenson’s New Arabian Nights (1882), a collection of Stevenson’s earliest stories that flowed from his own excitement over reading the Arabian Nights and which adapted its connected structure for his own modern tales. Warner mentions Stevenson, along with many other writers whose work has been prompted and inspired by the Arabian Nights. She recommends Robert Irwin’s excellent survey of such works in his chapter, “Children of the Nights” (in his book, The Arabian Nights: A Companion).

I will write about two books, Arabian Nights and Days by Naguib Mahfouz and Whatever Gets You Through the Night by Andrei Codrescu. These two caught my attention because of their focus on Scheherazade herself and their further exploration of the frame story of The Arabian Nights. I will also consider the most famous musical exposition of the character of Scheherazade, Rimsky-Korskov’s (1888) symphonic suite, and how the ballet later choreographed to that music diverged from the composer’s conception.

The Egyptian writer Naguib Mahfouz, the 1988 Nobelist in literature, is probably best known for his Cairo Trilogy (in Arabic; published in English with the titles Palace Walk, Palace of Desire, and Sugar Street). I was delighted to read his later novel Arabian Nights and Days, which is a sophisticated retelling of the Nights’ frame story and some of its important tales. Mahfouz refashions the stories to bring new insight into the characters of Shahrzad and Shahriyar (as they are spelled in Denys Johnson-Davies’ spare, yet mellifluous translation); they must truly grapple with the implications of all that gone before the moment when Shahrzad’s storytelling begins. Mahfouz connects each tale to the one that follows with seamless logic and suspense, and he brings greater depth even to such figures as Ma’rouf the Cobbler, Ugr the Barber, and, of course, Aladdin and Sindbad. But for me, the most arresting moment came when he implicitly asked the novelistic question, how would Shahrzad feel when she achieved her “victory” over the Sultan? His examination of this question plumbs new depths latent in one of the most well-known stories in world literature.

Before we see Shahrzad, Mahfouz shows us her father, the sultan’s vizier Dandan. In the three years that his daughter has been suspending Shahriyar’s death sentence with her entrancing stories, the vizier’s anxiety has not been suspended--quite the opposite. Each morning he would go to the palace, waiting to discover if this dawn would be Shahrzad’s last. On this day, “the heart of a father quaked within him” because he knew Shahrzad had done the unthinkable--she had ended her tale and her own fate must be decided one way or the other.

Dandan found Shahriyar alone, contemplating the first hints of sunrise: he says,”It is our wish that Shahrzad remain our wife. …Her stories are white magic…They open up worlds that invite reflection” (p. 2). When the Sultan continues, announcing that Shahrazad gave him a son and brought peace to his “troubled spirits,” the vizier wishes him happiness now and in the hereafter. This innocent blessing triggers a biting response--the Sultan dismisses the notion of happiness and puzzles over existence itself. In this way, we are given the first hint that although death is forestalled, “happily ever after” may not come as easily.

Next the vizier seeks out his daughter. Her response to her reprieve is complex and profound, even though it unfolds in a brief exchange that barely takes up two pages. Shahrzad acknowledges that by “the Lord’s mercy” her life has been spared and the young women of the city--those remaining--are no longer in peril, but at the cost of her happiness: “’I sacrificed myself,’ she said sorrowfully, ‘in order to stem the torrent of blood’” (p. 3). The vizier protests that the Sultan now loves her and that love works miracles, but Shahrzad answers that, “Arrogance and love do not come together in one heart” and, most devastating of all, “Whenever he approaches me I breathe the smell of blood” (p. 4).

Mahfouz has seemingly told the end at the beginning, but is it really the end? As his brilliantly refashioned cycle of tales nears its conclusion, Shahriyar becomes prominent again as the auditor of Sindbad’s tales of his voyages, told by Sindbad himself as fables of the wisdom he won along the way. Shahriyar persistently queries him as if his (Shahriyar’s) life depended on the answers. Sindbad finishes and Shahriyar retreats to his lush flower garden, pacing and remembering, his mind in turmoil and his heart gripped by weariness and disgust at his life--at the follies of life itself. He summons Shahrzad for a new dialogue--one not known to the ancient tradition but equally fateful, and full of truths as ancient as humanity. He confesses his need for repentance and reveals that he has known all along of her that “your body approaches while your heart turns away.” In a masterful stroke, Mahfouz’s Shahriyar asserts that he kept Shahrzad close to him as a reproach--“I found in your aversion a continued torment that I deserved” (p. 217). Shahrzad weeps, her heart melting perhaps for the first time in his presence, and he sees at once that this weeping means more than all the pretense of her love up to that point. He vows to renounce his kingdom and wander in search of wisdom and meaning, leaving his son, with Shahrzad’s counsel, to rule more wisely than he did. Now it is Shahrzad’s turn to see the bitter irony of this sudden decision--“You are spurning me as my heart opens to you. …It is an opposing destiny that is mocking us” (p. 218).

I hope readers of this blog will forgive the “spoilers” I have felt necessary to include. I shall leave one last surprise unspoken--what Shahriyar discovers on his quest for truth. But I wanted to disclose this much to make clear what a tour de force this new resolution of the frame story represents. Mahfouz’s alternative frame story refuses to find Shahriyar’s healing at the point when he rescinds the order of execution. No, that will not be enough to cure a soul that has strayed so far. Shahrzad feels this in her own heart, but she has done all she can do. She carries the wounds of all the sacrificed wives who preceded her, and now she too is in need of healing. Only Shahriyar’s act of atonement1 can change the equation. And with amazing poignance, it is only at the moment when the Sultan decides to leave Shahrzad that their real love story begins.

[image error]

NPR contributor and prolific writer Andrei Codrescu offers a retelling, Whatever Gets You Through the Night, that could hardly be more different from Mahfouz’s in tone and aims. Mahfouz is spare and restrained, recounting events and suggesting feelings and motivations with great economy. Codrescu is expansive (his Sheherezad doesn’t appear until page 46!), revelling in digression and comment, in voluminous marginal notes that can sometimes ring the main text in small type. In his ironic, punning treatment of the stories and in his commentary, he reveals his attitudes toward the gender politics of the stories as well as the whole historical enterprise of translating and transmitting the tales. Twenty-three different epigraphs, arranged together before the main text, quote sources ranging from Wikipedia to rival translators Richard Francis Burton and Husain Haddawy to critic J. Hillis Miller to the Rolling Stone, announcing that this retelling will be openly conscious of all the textual history that has gone before. A preface of sorts includes these observations on Sheherezade:

“We are bound to tell her story no matter what our postmodern wishes or rebellious inclinations might tell us: simply pronouncing her name invokes her. When she appears, like the Genie in the bottle of literature that she is, we must obey the order of her stories [he doesn’t]; this is the exact opposite of the Genii and Genies who are freed or imprisoned in the bottles of her characters, who must obey their liberators….” (p. 1)

This passage is characteristic of Codrescu and of the experience of reading this book: expect trenchant observations delivered with irreverence, skepticism, and a winking eye. Also expect the story will linger on lurid details of the murders of the Sultan’s previous wives and explicit description of the sexual situations implicit in the story. This text attempts to startle the reader into taking a fresh look at an old narrative tradition. Within that tradition, Codrescu aligns his sympathy more nearly with Burton, whose titillating translation, cloaked in archaic language, fed a certain late-Victorian appetite, especially his own.

Codrescu makes crucial archetypal connections between Scheherazade and figures such as Penelope and Ariadne, as in this brilliant synthesis:

“Sheherezade’s job was to be like Ariadne to make the King believe that she was showing him the way out of the labyrinth of his insecurity and cruelty, while weaving [like Penelope] at the same time a labyrinth from which he could never escape to kill again.” (p. 97)

The net that is woven is an erotic one, but oddly Sheherezade herself is sidelined in favor of her sister, Dinarzad. The storytelling ménage à trois becomes a sexual pas de deux between the two listeners, Sharyar and Dinarzad, whose dalliance fails to reach its climax just as each story’s ending is postponed.

Codrescu offers what he calls the “unpopular” ending, one in which he posits there was no baby, no reconciliation of the Sultan to women, and, therefore, no pardon for his Sheherezade; he prefers to believe that the stories had no end and we can listen in whenever we choose. In fact we need to listen, trancelike, he argues, because we cannot face our lives without entertainment. Thus, he concludes with an extended meditation on media culture where we are “angry mass-Sharyars” and “terrified when you are silent” (p. 173). All of this does end up being intriguing and a very modern deconstructive performance, but I confess that I preferred Mahfouz’s Arabian Nights and Days, which explored more deeply the redemptive core of the Nights, while preserving the echoes of the imaginative realms that gave it birth.

[image error]

I was going to write at length about Rimsky-Korsakov’s gorgeously melodic symphonic suite of Scheherazade and compare it with Mikhail Fokine’s popular Scheherazade ballet of 1910, set to some of its music, and with a new libretto by Léon Bakst and Fokine. (Rimsky-Korsakov’s widow was apparently quite unhappy with the rearrangement of the score.) Despite its name, the ballet dramatizes only events occurring before the intervention of Scheherazade, namely, the infidelity of the Sultan’s first wife. Most of the dancing is a sensuous, extended duet between Zobeide2 (the wife) and a “Golden Slave”--in Fokine’s Ballet Russes choreography, this role was a vehicle for the superlative genius of Vaslav Nijinsky.

[image error]

Unfortunately, Scheherazade’s recurring narration from bed does not lend itself easily to having her dance! Ahh, but I see the night grows short, this post is already very long, and I must stop for now and send you to meet the musical Scheherazade for yourself in the lyrical space beyond words…

Notes:

In this connection, I highly recommend Phil Cousineau ’s Beyond Forgiveness: Reflections on Atonement (Jossey-Bass, 2011), which collects essays from diverse authors on ways to move from words of repentance or forgiveness toward atoning actions which may potentially heal both parties.

I recommend a performance of Fokine’s ballet in The Kirov Celebrates Nijinsky (DVD) , but be aware that the back-cover text incorrectly identifies the principal female role (danced by Svetlana Zakharova) as Shehérézade instead of Zobeide.

Scheherazade/Shahrazad ranks 13th on The Fictional 100 .

Related post:

To Be Continued: Scheherazade and the Arabian Nights (1)

July 10, 2012

“To Be Continued”: Scheherazade and the Arabian Nights (1)

Stranger Magic: Charmed States and the Arabian Nights by Marina Warner, Belknap Press (Harvard University Press), 2012.

If you have any interest in the history of fairy tale and magical narrative, in the transmission of stories from East to West, and back again, then you may find Marina Warner’s new book, Stranger Magic, as captivating as I did. Warner is best known for her brilliant critical syntheses of fairy tales and their modern cultural expressions, as in From the Beast to the Blonde (1995), and I believe Stranger Magic is her best book since that one. Here she seeks to open readers to the complex history that has produced The Arabian Nights, as we read them today, whether they are told in Arabic or in one of many diverse translations, whether they include just a few selected stories or collect a wealth of the Thousand and One Nights, culled from various sources. Although she herself chooses to retell and comment upon 15 illustrative stories (including “The Fisherman and the Genie,” “Prince Ahmed and the Fairy Peri Banou,” “Marouf the Cobbler,” and “Camar al-Zaman and Princess Badoura”), she resists attempts to identify The Arabian Nights only with a “core” of originals rather than with the whole evolving tradition of stories that have grown up around the Nights through an interplay of oral and written transmission. For example, although she retells the most “authentic” Aladdin tale, “Aladdin of the Beautiful Moles,” she cites the better known tale of Aladdin and the magic lamp, most likely written and added by translator Antoine Galland, as a valid accretion to the cycle as a whole.

As Warner says, the stories themselves are “shape-shifters” but standing apart from the shifting dream world of stories is Scheherazade. Whether her name is translated as Shahrazad, Shahrzad, Sheherezade, or Shéhérezade (I have seen all of these, and more), she holds a unique place as the still point from which the tales arise and connect. In the frame story, Shahrazad (Warner and others have settled on this spelling, and I will too) has amassed a vast bank of stories learned by heart from her teachers and from her father’s library--her memory is her first magical gift. Thus, as Warner notes, in the context of the Nights, the only truly new story Shahrazad tells is the story of Sultan Shahriyar himself, one whose outcome she herself is affecting. Technically, her stories are classified as “ransom tales,” each one buying her life and staying her execution, upon the orders of her bitterly jealous husband, for just one more day. They can also be seen as amulets, specially crafted charms to ward off the evil of her husband’s cruel death sentence (hence Warner’s subtitle, “Charmed States and the Arabian Nights”). Finally, as a matter of discourse structure, her stories are “performative utterances,” doing what they intend--delaying her death--by the very act of speaking them and inviting Shahriyar to listen. He in turn changes his utterance from “kill her in the morning” to “wait, I want to hear the end of this story.” The power of speech is implicitly celebrated with every word of the Nights, a fearsome power and, from Shahrazad’s mouth, a transformative power as well, gradually healing the Sultan’s once-incurable heart.

Biographer Peter Ackroyd describes The Arabian Nights--to my surprise--as “arguably the most important of all literary influences upon Charles Dickens” (Dickens, p. 45), forming some of his most beloved childhood reading along with Fielding and Smollett. Ackroyd notes many direct references popping up in his novels, and Warner highlights a wonderfully subtle example in A Christmas Carol, when Scrooge attempts to trap the first, bright Spirit who visits him beneath an enormous candle snuffer! Warner sees the Spirit as a benevolent jinni, “intent on doing him good,” but Scrooge would much rather bottle him, so to speak, and go back to bed in peace. As the Nights show time and again, being visited by a jinni is always life changing, one way or another!

[image error]

[Scrooge extinguishes the First of the Three Spirits, illus. by John Leech, 1843; image scanned by Philip V. Allingham]

Sigmund Freud believed that elements of the unconscious were bottled up in his patients, making them ill. One of my favorite chapters in Warner’s book is chapter 20, “The Couch: A Case History,” in which she interprets Freud’s psychoanalytic “talking-cure” as a symbolic instance of Shahrazad-in-reverse: “talking as a form of storytelling, with the roles reversed (it is the narrator who needs to be healed, not the listener-Sultan)” (p. 29, my emphasis). As she says, “The Arabian Nights is a book of stories told in bed,” and Freud draped his “bed,” the famous analyst’s couch, with oriental cushions and a gorgeous Ghashga’i rug--a veritable magic carpet for patients to ride while free-associating, relaxing repressions, and liberating unconscious thoughts. This very carpet was moved from Vienna to London when Freud moved there, and the book includes a color photo of it in Freud’s reconstructed consulting room at the Freud Museum in London, where it is exhibited.

[image error]

The parallels to the Nights are astonishing: “The seating arrangement Freud devised, still practised in analysis today, interestingly, set up a scene of eavesdropping, not conversation, which places the analyst in the position of the Sultan in the frame story of the Nights” (p. 419). This refers to the fact that Shahrazad’s stories are not addressed directly to Shahriyar, but rather to her sister Dinarzad (or Dunyazad, in some versions) who has accompanied her sister on the wedding night for the express purpose of requesting a tale to while away the hours till dawn. Shahriyar’s ear is caught, then his mind and curiosity, and finally his heart, which, after the fabled 1001 nights, opens to a different view of women, or at least one exemplary woman, now his wife and mother to three children. In psychoanalysis, the analyst provides the recurring occasion and allows the stories to emerge--stories the teller is heretofore unaware of possessing inside herself. Like Shahrazad, most of Freud’s patients were women.

What shall we make of the storytelling art as Shahrazad practices it? Besides its life-saving role within the story world, what is its role in our world? Freud’s magic-carpet couch is only one possible answer. Warner writes with warm enthusiasm about the stories as instances of Jorge Luis Borges’ concept of “reasoned imagination” and she devotes much space to what she calls “flights of reason,” stories as “thought-experiments.” She hopes to move discussion of the Nights away from the battleground of “Orientalism,” begun in response to Edward Said’s brilliant polemical book about the reception of Arabic and Persian literature in the West, and edge it toward an alternative tradition of “the Nights as a genre of dazzling fabulism … the begetter of magical realism” (p. 24), which she traces to Voltaire (Zadig, or Destiny; Candide) and then more recently through Borges (Ficciones), Italo Calvino (If on a Winter’s Night a Traveler), Gabriel García Márquez (One Hundred Years of Solitude), Salman Rushdie (Midnight’s Children; Haroun and the Sea of Stories), and others. She writes:

“the Nights inspires a way of thinking about writing and the making of literature as forms of exchange across time--dream journeys in which the maker fuses with what is being made, until the artefact exercises in return its own fashioning force. …draw[ing] away from the prevalent idea of art as mimesis, representing the world in a persuasive, true-to-life way, and emphasise instead the agency of literature. Stories need not report on real life, but clear the way to changing the experience of living it.” (Warner, p. 27, my emphasis)

She concludes with thoughts about the ongoing political changes and the voices being raised in the Middle East and North Africa--artists, writers, and filmmakers working in a new time, but in the age-old lands that inspired The Arabian Nights. What they will create still holds the potential “to lift the shadows of rage and despair, bigotry and prejudice, to invite reflection---to give the princes and sultans of this world pause. This was--and is--Shahrazad’s way” (Warner, p. 436).

As an artefact in the world, The Arabian Nights is still living and changing. The stories still call out for new tellers, new Shahrazads who remember the old stories and add new ones, who reveal something new in the telling and retelling, who heal wounds and transform hearts. Warner says, “the book cannot ever be read to its conclusion: it is still being written” (p. 430). In my next post, I will consider a few examples of these retellings and describe how they add to and remake the tradition. To be continued...

Scheherazade/Shahrazad ranks 13th on The Fictional 100 . On her page you will also find other references to modern editions of The Arabian Nights.

Related post:

Ghosts of Scrooges Past: Revisiting “A Christmas Carol”

June 2, 2012

In and “Out of Oz”: Dorothy in the “Wicked Years” series

Out of Oz: The Final Volume in the Wicked Years by Gregory Maguire, illus. by Douglas Smith. HarperCollins, 2011.

Dorothy, the beloved character created at the turn of the 20th-century by L. Frank Baum in The Wonderful Wizard of Oz, makes pivotal appearances in all four volumes of Gregory Maguire’s inspired refashioning of the Oz world, his “Wicked Years” series. She does not hold center stage, however, in these books which are a brilliant exercise in empathy for the “Wicked” witch, Elphaba Thropp, and her descendants. These books imaginatively alter an already alternate universe, and transform a classic of children’s fantasy literature--also widely appreciated by adults--into a sometimes quite disturbing fantasy fiction for adults. In this alternate history, Dorothy Gale still comes in and out of Oz, on and off the stage, at crucial times and much of the story could never exist without her.

Dorothy's first visit to Oz comes along rather late in Wicked (2004), which introduced Elphaba's family, chronicled her childhood, and sent her to college in the Gillikin town of Shiz where she unwillingly shared a room with Galinda (later Glinda) and began to learn about the politics of Oz and where she would stand on them. For one thing, she championed the cause of the free, sentient, talking Animals (always capitalized, as in Lion). She also came to recognize the tyranny of the Emerald City over the other regions of Oz, which were exploited by its leader the Wizard. After their college years were over, Elphaba began to act, in secret, as an agent of the resistance to the Wizard.

Dorothy's arrival from Kansas in the twister-propelled house killed Elphaba's sister Nessarose, who had become the leader of Munchkinland. Here the story begins to intersect recognizably with Baum’s tale. Glinda gave Nessarose’s magical slippers to Dorothy, enraging Elphaba, who retreated again to a castle deep in the western region of Oz, the Vinkus (Winkie country). This place was the family home of Fiyero, Elphaba’s only love and father of her son Liir; Fiyero was killed by the Wizard’s secret police who were after her. While Dorothy and her motley companions walked the Yellow Brick Road to see the Wizard, Elphaba learned sorcery from the Grimmerie, a magic text which had attracted the Wizard to Oz in the first place.

Dorothy had apparently accepted the Wizard's charge to kill the Wicked Witch of the West, but in Maguire's telling, she had no such intention, but journeyed there to apologize to Elphaba for killing her sister with the falling house. Elphaba had become embittered by many griefs and their meeting was confrontational and disastrous. Elphaba's skirts were set on fire and Dorothy threw the bucket of water to douse the flames and save her, but this melted and killed her instead.

The next book, Son of a Witch (2005), tells Liir’s story (with flashbacks to fill in gaps) from the death of Elphaba to the birth of his own daughter. Dorothy’s role is brief. She took him with her back to the Emerald City and Liir developed a crush of sorts on the odd Kansas farmgirl. Perhaps her being so out of place in Oz spoke to his own sense of disconnection with all that had happened to him.

A Lion Among Men recounts Dorothy's first visit to Oz from the view point of Sir Brrr, otherwise known as the Cowardly Lion. But it spans more of his life than this one episode, and thereby reveals more of his character, in keeping with the series' ethos of respecting intelligent Animals.

In the final volume, Out of Oz, Dorothy returns to Oz, this time in the San Francisco earthquake of 1906! (This reference to the quake in popular culture has already found its way into the wikipedia article on the event.) Auntie Em and Uncle Henry have taken Dorothy on a trip west from Kansas, in hopes that the change of scene will help cure Dorothy of her persistent delusional talk about Oz! Maguire manipulates the chronology deftly: From 1900 (publication of Baum's first Oz book) to 1906 is 6 years and Dorothy has aged from 10 at her first visit to 16 for her second. Meanwhile, about 16 years have passed in Oz (leading to jokes where Dorothy agrees that time passes slowly--very slowly--in Kansas). Most of the book follows the coming-of-age adventures of Rain, Liir's daughter and thus Elphaba's granddaughter. The best Oz stories have a child at their heart and Maguire's concluding tale is no different in that respect. The Cowardly Lion is likewise one of Rain's faithful companions and provides a necessary link between the first and last books and between Baum's storyworld and Maguire's.

Some of the key plot elements (the war of rebellion in Oz) and several of the characters (including Tip, Mombey, Ozma, and Jinjuria) in Out of Oz mirror those in Baum's second Oz book, The Marvelous Land of Oz (1904). Of Baum's fourteen Oz novels, this is the only one in which Dorothy doesn't appear. However, Maguire gives her an important role, especially in the centerpiece murder trial, "The Judgment of Dorothy." Revealing how that came out would be a *spoiler* indeed!

Instead of revealing more of Maguire's well-crafted plot, let me consider instead how he portrays Dorothy in this series and how his attitude toward her differs from Baum's. Given how she is described by the narrator and how other characters speak of her, she is an ungainly child, "not a dainty thing but a good-size farm girl," (Wicked, p. 3), and an even more awkward teenager. Rather than fitting Baum illustrator John R. Neill's winsome vision...

she seems much closer to the stocky miss imagined by her first illustrator, W. W. Denslow.

She is saccharine, "misguidedly cheerful," given to inappropriate singing, apparently stupid, and clearly a menace! In the prologue to Wicked, Elphaba finds her sympathy patronizing. While naive and guileless, she has a definite presence, especially during her trial:

Aha, thought Brrr, there it is: she has graduated to Miss Dorothy. In her zanily earnest way, she's commanding the respect of her enemies despite themselves. Brrr would never call it charisma but oh, Dorothy had charm of a sort, for sure. (Out of Oz, p. 294)

Her best qualities came out in her desire to make amends and her insistence on helping Rain. But in the end, for Maguire, Dorothy's life, despite its adventures and calamities (she was an orphan), was not touched to the same degree by the sorrows and tragedies that characterized the Wicked clan. Her disposition was so incredible to the Ozians that they imagined at one point that she must be an assassin, disguised "as a gullible sweetheart." Baum prized Dorothy's innocent goodness, her wide-eyed, doughty good humor, but in the Wicked universe (our universe?), it became almost an affront to the inhabitants laboring under so much pain. The onslaught of sorrows broke Elphaba's spirit, left Liir perplexed, and made Rain cry for "the whole pitfall of it, the stress and mercilessness of incident" (p. 421). Even Glinda was imprisoned and suffered during the war. The gentle satire of Dorothy's "soapy character" makes it clear that this author would not choose her outlook, but instead felt greater affinity for Elphaba above all, whose tortured spirit never really leaves the saga for long.

May 1, 2012

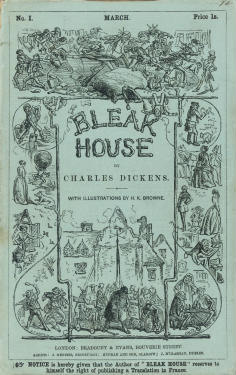

“The Solitary House” by Lynn Shepherd: A Review, with remarks on Charles Dickens’s “Bleak House”*

It might be said that, for great literature, pastiche is the sincerest form of flattery. The works of Shakespeare, Jane Austen, and Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, among others, have been particular favorites in the art of pastiche, because of the wealth of opportunity they offer for variation and creative amalgamation. Not to be confused with parody, pastiche is “(a) a literary, artistic, or musical composition made up of bits from various sources; potpourri; (b) such a composition intended to imitate or ridicule another’s style” (Webster’s New World Dictionary, 1982). The element of parody can be present, but pastiche can equally well be a work of respectful imitation and delightful re-invention.

Such are the mystery novels of literary specialist Lynn Shepherd, whose first work, Murder at Mansfield Park (St. Martin’s Press, 2010), turned the tables on Austen’s heroine Fanny Price and found new possibilities for Mary Crawford and the other young people gathered at the venerable country house. In particular, she plucked Charles Maddox from his relatively minor role as a prospective player in the “Lovers’ Vows” private theatrical and repurposed him as a very excellent detective.

For her second mystery, Shepherd has pushed the clock ahead a few decades to the 1850s and she has found her inspiration chiefly (but not exclusively) in Charles Dickens’s Bleak House. In The Solitary House (Delacorte Press, 2012; titled Tom-All-Alone’s, in the UK), Shepherd brings her careful attention and knowledge to produce a new detective story that worthily comments on its original, varies it meaningfully, and finally stands on its own.

G. K. Chesterton, still one of Dickens’s most perceptive and appreciative critics, wrote: “Bleak House is not certainly Dickens’s best book; but perhaps it is his best novel.” John Forster, Dickens’s friend and early biographer, agreed in his estimation of Bleak House: “The novel is nevertheless, in the very important particular of construction, perhaps the best thing done by Dickens.” Shepherd avows that Bleak House is Dickens’s masterpiece; her affection and appreciation for the novel is everywhere evident. In The Solitary House, she makes full use of what Bleak House offers, even adapting a selection of Dickens’s chapter titles, rearranging them, and giving them a new significance in the context of her own detective mystery. Here we meet again the inscrutable lawyer and repository of his clients’ secrets, Tulkinghorn, and the jovial, but keen-eyed and relentless Inspector Bucket. (Dickens’s illustrator Hablot Knight Browne, “Phiz,” chose to illustrate the jovial side in the “Friendly Behaviour of Mr. Bucket”; image scan by George P. Landow.)