Stan C. Smith's Blog, page 31

October 29, 2018

Awesome Animal - Poison Dart Frog

You know how some animals have been given a name that makes them sound just awful? Like the gila monster (a lizard), or the hellbender (a salamander), or maybe the blobfish? It doesn't seem fair to the animal, does it? Well, today's awesome animal, the poison dart frog, is another creature with an undeserved negative name. But in spite of the name, they are arguably the most beautiful frogs in the world.

So, what the heck is a Poison Dart Frog?

Poison dart frogs are small but spectacular frogs in the family, Dendrobatidae. There are about 300 species living in Central America and South America.

Yes, some of these frogs really are poisonous, and yes, native peoples use their poisons on the tips of their hunting blow darts (or at least they used to). Nevertheless, is it fair to name the entire group poison dart frogs? Out of about 300 species, only three of them are known to have been used for such a purpose. Many of the species aren't toxic at all or are only mildy toxic.

The first poison dart frog I had a chance to see in the wild was when Trish and I were in Costa Rica in 2016. We had arrived at a nice ecolodge, and we were sitting on the patio, which was surrounded by gardens. I noticed a tiny green and black frog hopping through the vegetation nearby. It turned out to be this frog (which happens to actually be called the green and black poison dart frog):

Amazing facts about Poison Dart Frogs

Some poison dart frogs really are poisonous, but they are not venomous. Let's clear up a few important points. There are literally millions of animals that produce toxic chemicals. But that doesn't mean they're poisonous. By definition, in order to be poisonous , an animal must be toxic to eat. Poison dart frogs store toxins in glands beneath their skin. So if you eat one that is highly poisonous, you may be in serious trouble. For an animal to be venomous , it must have the ability to inject a toxic substance with fangs, a stinger, barbs, spurs, or something similar. Rattlesnakes and honeybees are venomous.

Poison dart frogs do not bite and do not inject venom, so they are not venomous. They are poisonous.

How poisonous are they? Well, most of them aren't particularly dangerous to humans. As I said above, only three types have been used for making poison hunting darts. But the most toxic of these, the golden poison frog, is one of the most toxic creatures on Earth. The poison from one individual is enough to kill 20,000 mice. Wow! How many humans would that be? Here's a golden poison frog:

Poison dart frogs do not produce their poisons. Huh? It's true. Instead of producing the poisons in their own bodies, these frogs get the substances from the food they eat. They specialize on eating certain ants, beetles, mites, and millipedes that contain these toxins. This is why poison dart frogs that are raised in captivity have minimal levels of toxins. They don't have access to their natural, toxin-heavy food source.

These frogs give their babies a toxin boost at a very young age. Recent studies have shown that mother frogs lay a number of unfertilized eggs, which happen to be laced with toxin. They feed these eggs to their young tadpoles, thus giving their babies a nice toxin boost to get them started. Isn't that sweet?

Studies have shown that the brighter the frog is, the more toxic its poison is. Scientists actually used a spectrophotometer to measure the frogs' color. Those that were brighter and more conspicuous were more toxic.

Below is the other poison dart frog we saw in Costa Rica, the strawberry poison dart frog:

Okay, here's a question you may be wondering about. Since these frogs get their toxins by eating toxic prey (ants, mites, etc.), why aren't they poisoning themselves when they do this? As it turns out, it is a fairly simple mutation that makes them immune to the poison.

If you want a more detailed explanation of this, check out this video.

The way that natives used the frogs to get the poison onto their darts was rather gruesome. A study of the Emberá Indians of Columbia described the process. These people would catch a number of the frogs and place them in a hollow cane. When preparing darts, they would pull out a frog and "pass a pointed piece of wood down his throat, and out at one of his legs." Obviously, this would seriously agitate the frog, causing it to "sweat" out the poison on its back. They would then dip their arrows in the poison, and these arrows would remain effective for up to a year.

Poison dart frogs evolved their extremely bright colors as a way to warn predators not to eat them. This is called Aposematism (a fancy word for "warning coloration"), and it is common in many different poisonous and venomous animals. The coral snake is a venomous example, and the monarch butterfly is a poisonous example. The bright black and white pattern of a skunk is another example, but skunks have a very different threat for predators to avoid.

One more poison dart frog example, the blue poison dart frog:

So, the Poison Dart Frog deserves a place in the B.T.C.A.H.O.F.

(Beyond The Call Animal Hall of Fame).

FUN FACT: The phrase beyond the call is a reduction of "above and beyond the call of duty," which probably originated in the American armed forces during World War I. In 1916, the services created a series of medals to honor acts of courage. The Medal of Honor would only be awarded for actions “above and beyond the call of duty." More recently, the phrase has become a way to describe almost anything that is excellent or well done. There are actually two shortened versions: "beyond the call" and "above and beyond."

So, beyond the call is another way to say awesome! Photo Credits:

Green and Black Poison Dart Frog - Stan C. Smith

Golden Poison Frog - Wikimedia Commons

Strawberry Poison Dart Frog - Stan C. Smith

Native with Blowgun - Wikimedia Commons

Blue Poison Dart Frog - National Aquarium

So, what the heck is a Poison Dart Frog?

Poison dart frogs are small but spectacular frogs in the family, Dendrobatidae. There are about 300 species living in Central America and South America.

Yes, some of these frogs really are poisonous, and yes, native peoples use their poisons on the tips of their hunting blow darts (or at least they used to). Nevertheless, is it fair to name the entire group poison dart frogs? Out of about 300 species, only three of them are known to have been used for such a purpose. Many of the species aren't toxic at all or are only mildy toxic.

The first poison dart frog I had a chance to see in the wild was when Trish and I were in Costa Rica in 2016. We had arrived at a nice ecolodge, and we were sitting on the patio, which was surrounded by gardens. I noticed a tiny green and black frog hopping through the vegetation nearby. It turned out to be this frog (which happens to actually be called the green and black poison dart frog):

Amazing facts about Poison Dart Frogs

Some poison dart frogs really are poisonous, but they are not venomous. Let's clear up a few important points. There are literally millions of animals that produce toxic chemicals. But that doesn't mean they're poisonous. By definition, in order to be poisonous , an animal must be toxic to eat. Poison dart frogs store toxins in glands beneath their skin. So if you eat one that is highly poisonous, you may be in serious trouble. For an animal to be venomous , it must have the ability to inject a toxic substance with fangs, a stinger, barbs, spurs, or something similar. Rattlesnakes and honeybees are venomous.

Poison dart frogs do not bite and do not inject venom, so they are not venomous. They are poisonous.

How poisonous are they? Well, most of them aren't particularly dangerous to humans. As I said above, only three types have been used for making poison hunting darts. But the most toxic of these, the golden poison frog, is one of the most toxic creatures on Earth. The poison from one individual is enough to kill 20,000 mice. Wow! How many humans would that be? Here's a golden poison frog:

Poison dart frogs do not produce their poisons. Huh? It's true. Instead of producing the poisons in their own bodies, these frogs get the substances from the food they eat. They specialize on eating certain ants, beetles, mites, and millipedes that contain these toxins. This is why poison dart frogs that are raised in captivity have minimal levels of toxins. They don't have access to their natural, toxin-heavy food source.

These frogs give their babies a toxin boost at a very young age. Recent studies have shown that mother frogs lay a number of unfertilized eggs, which happen to be laced with toxin. They feed these eggs to their young tadpoles, thus giving their babies a nice toxin boost to get them started. Isn't that sweet?

Studies have shown that the brighter the frog is, the more toxic its poison is. Scientists actually used a spectrophotometer to measure the frogs' color. Those that were brighter and more conspicuous were more toxic.

Below is the other poison dart frog we saw in Costa Rica, the strawberry poison dart frog:

Okay, here's a question you may be wondering about. Since these frogs get their toxins by eating toxic prey (ants, mites, etc.), why aren't they poisoning themselves when they do this? As it turns out, it is a fairly simple mutation that makes them immune to the poison.

If you want a more detailed explanation of this, check out this video.

The way that natives used the frogs to get the poison onto their darts was rather gruesome. A study of the Emberá Indians of Columbia described the process. These people would catch a number of the frogs and place them in a hollow cane. When preparing darts, they would pull out a frog and "pass a pointed piece of wood down his throat, and out at one of his legs." Obviously, this would seriously agitate the frog, causing it to "sweat" out the poison on its back. They would then dip their arrows in the poison, and these arrows would remain effective for up to a year.

Poison dart frogs evolved their extremely bright colors as a way to warn predators not to eat them. This is called Aposematism (a fancy word for "warning coloration"), and it is common in many different poisonous and venomous animals. The coral snake is a venomous example, and the monarch butterfly is a poisonous example. The bright black and white pattern of a skunk is another example, but skunks have a very different threat for predators to avoid.

One more poison dart frog example, the blue poison dart frog:

So, the Poison Dart Frog deserves a place in the B.T.C.A.H.O.F.

(Beyond The Call Animal Hall of Fame).

FUN FACT: The phrase beyond the call is a reduction of "above and beyond the call of duty," which probably originated in the American armed forces during World War I. In 1916, the services created a series of medals to honor acts of courage. The Medal of Honor would only be awarded for actions “above and beyond the call of duty." More recently, the phrase has become a way to describe almost anything that is excellent or well done. There are actually two shortened versions: "beyond the call" and "above and beyond."

So, beyond the call is another way to say awesome! Photo Credits:

Green and Black Poison Dart Frog - Stan C. Smith

Golden Poison Frog - Wikimedia Commons

Strawberry Poison Dart Frog - Stan C. Smith

Native with Blowgun - Wikimedia Commons

Blue Poison Dart Frog - National Aquarium

Published on October 29, 2018 09:59

October 20, 2018

Awesome Animal - Pillbug

This week's Awesome Animal is one that plays an important role in my upcoming novel,

Bridgers 4

! The animal is the

PILLBUG

. Well, it isn't really pillbugs that show up in the book. It's actually... well, you're just going to have to read the book when it comes out in late November.

You see, pillbugs are near and dear to my heart. Why? Well, back when I was teaching biology to 7th graders (kids 12 to 13 years old), I did a major research and creative-writing project that involved pillbugs. More on that below. But other than that, pillbugs are just awesome!

I may need to explain that the name, Pillbug, may not be know to everyone everywhere. Around here, many people call them roly polies. They are also called woodlice, isopods, armadillo bugs, potato bugs, doodle bugs, and my favorite, chuggypigs. I would be interested to know what people call them where you live... please reply and let me know.

So, what the heck is a Pillbug?

A pillbug is not really a bug. It's not an insect. It's actually a crustacean. You know what crustaceans are, right? Crustaceans include lobsters, crabs, shrimp, crayfish, krill, barnacles, and many others. Pillbugs are unusual for crustaceans in that they are terrestrial (they live on land instead of in water). Pillbugs are in an order of crustaceans called isopods. This also includes sowbugs, which are similar to pillbugs. But pillbugs have a superpower that sowbugs don't--the ability to roll into a ball, which is how they got the name pillbug.

Amazing facts about Pillbugs

As mentioned above, pillbugs have the ability to roll into a tight ball. There is actually a name for this. To roll into a ball is to conglobate. The obvious benefit of conglobation is protection from predators. But some biologists believe it is even more important as a way to avoid dehydration. Pillbugs are about the only crustaceans that live on land, and they are not as well adapted to dry land as insects. They do not have the waterproof waxy coating that insects have. They use gill-like structures to breath, and therefore they have to spend their time in moist areas under rocks and logs, and if you put them in a dry environment, they will roll into a ball to keep from drying out. Here is a conglobating pillbug:

Pillbugs can drink through their anus. Actually, they can and do suck up water through their mouth parts, like we do. But remember, they are very sensitive to drying out, so they also have the ability to take in water through special tubes at their rear end, called uropods. Okay, weird.

Pillbugs do not pee. That's right. They do not need to urinate. Most animals cannot tolerate ammonia, which happens to be present in the wastes that are created inside our bodies. Most animals convert these wastes into urea and then squirt that out of their bodies. That's urine. But pillbugs have an amazing tolerance for ammonia gas, and they can just excrete it directly out through their exoskeleton. Wow, it would be nice to not have to pee. I could sleep through the whole night!

Pillbugs molt in two sections. As crustaceans, pillbugs are included in the larger group, Arthropods (which also includes insects, spiders, and more). Arthropods have exoskeletons, and almost all of them grow larger by periodically molting their exoskeleton (which doesn't grow once it hardens). Beneath the shed exoskeleton is a new, soft exoskeleton, which immediately grows larger before it hardens up. Pillbugs are different in that they first shed the exoskeleton on their back half. Then a few days later they shed the front half.

Check out this cool video of pillbugs molting.

Pillbugs walk around on seven pairs of legs. Strangely, though, when baby pillbugs hatch, they only have six pairs of legs. They don't get the seventh pair until after they molt for the first time.

Pillbugs eat decaying matter on the forest floor and under rocks and logs. They also eat their own poop. That's right. It's a real thing among may animals, and it is called coprophagy. Other animals do it for different reasons, but pillbugs do it to conserve copper. Pillbugs need copper in their bodies, and they lose some of it every time they poop. So they have a habit of eating their poop to conserve the copper.

Female pillbugs carry their babies around on their underneath side. The eggs are layed and then transferred to the marsupium (similar in function to a marsupial's pouch). The eggs hatch in the marsupium, and then the young hang on to the mother's underside for eight to twelve weeks as they develop.

Okay, so I have to talk a bit about the The Pillbug Project (the actual title of a project I did with my 7th graders back in my teaching days). We formed a partnership with a dozen or so other schools in North America. The students in each partner class went out and collected pillbugs in their area. We then carried out a series of experiments with the pillbugs to see how well adapted they were to the climate in their area of the continent. These were simple choice experiments. For example, put the pillbugs in a container that is dry on one side and moist on the other side. After a specific amount of time, count how many are on each side. We did the same thing with warm and cool sides, light and dark sides, etc. Not surprisingly, we found that the ones from warm, dry areas of the continent were more comfortable on the dry side and on the warm side. Those from cooler, wetter regions were more comfortable on the cool side and wet side. And so on. There were many more experiments involved, but you get the idea.

We also worked collaboratively with the students at the other schools to write a fun book about an intelligent pillbug from the future that travels back in time to teach a pair of teens about the history of life on Earth. This pillbug, named Armadillia, had a nifty little time machine attached to a belt around his waist. Below is a drawing one of my students created, his vision of what this fictional character should look like.

So, the Pillbug deserves a place in the F.A.H.O.F. (Fetch Animal Hall of Fame).

So, the Pillbug deserves a place in the F.A.H.O.F. (Fetch Animal Hall of Fame).

FUN FACT: The word fetch in this usage is, I suppose, a reduction of fetching, which means "attractive." Okay, I must admit, using the word fetch in this context isn't really a thing. It comes from the 2004 movie, Mean Girls, in which Gretchen tries to make fetch a thing but gets shut down by her friend, Regina George. Here's the clip. In spite of Gretchen's efforts, in the 14 years since the movie came out, fetch still isn't catching on. But Regina's response ("Stop trying to make Fetch happen!)" has now become a way to mock people who are out of touch. So... for Gretchen's sake, I'm going to say that fetch is another way to say awesome!

Photo Credits:

Pillbug #1 - on finger - Backyard Nature

Pillbug rolled up - James Castner, University of Florida.

Pillbug Shedding - Backyard Nature

Pillbug Babies - The Living Classroom

You see, pillbugs are near and dear to my heart. Why? Well, back when I was teaching biology to 7th graders (kids 12 to 13 years old), I did a major research and creative-writing project that involved pillbugs. More on that below. But other than that, pillbugs are just awesome!

I may need to explain that the name, Pillbug, may not be know to everyone everywhere. Around here, many people call them roly polies. They are also called woodlice, isopods, armadillo bugs, potato bugs, doodle bugs, and my favorite, chuggypigs. I would be interested to know what people call them where you live... please reply and let me know.

So, what the heck is a Pillbug?

A pillbug is not really a bug. It's not an insect. It's actually a crustacean. You know what crustaceans are, right? Crustaceans include lobsters, crabs, shrimp, crayfish, krill, barnacles, and many others. Pillbugs are unusual for crustaceans in that they are terrestrial (they live on land instead of in water). Pillbugs are in an order of crustaceans called isopods. This also includes sowbugs, which are similar to pillbugs. But pillbugs have a superpower that sowbugs don't--the ability to roll into a ball, which is how they got the name pillbug.

Amazing facts about Pillbugs

As mentioned above, pillbugs have the ability to roll into a tight ball. There is actually a name for this. To roll into a ball is to conglobate. The obvious benefit of conglobation is protection from predators. But some biologists believe it is even more important as a way to avoid dehydration. Pillbugs are about the only crustaceans that live on land, and they are not as well adapted to dry land as insects. They do not have the waterproof waxy coating that insects have. They use gill-like structures to breath, and therefore they have to spend their time in moist areas under rocks and logs, and if you put them in a dry environment, they will roll into a ball to keep from drying out. Here is a conglobating pillbug:

Pillbugs can drink through their anus. Actually, they can and do suck up water through their mouth parts, like we do. But remember, they are very sensitive to drying out, so they also have the ability to take in water through special tubes at their rear end, called uropods. Okay, weird.

Pillbugs do not pee. That's right. They do not need to urinate. Most animals cannot tolerate ammonia, which happens to be present in the wastes that are created inside our bodies. Most animals convert these wastes into urea and then squirt that out of their bodies. That's urine. But pillbugs have an amazing tolerance for ammonia gas, and they can just excrete it directly out through their exoskeleton. Wow, it would be nice to not have to pee. I could sleep through the whole night!

Pillbugs molt in two sections. As crustaceans, pillbugs are included in the larger group, Arthropods (which also includes insects, spiders, and more). Arthropods have exoskeletons, and almost all of them grow larger by periodically molting their exoskeleton (which doesn't grow once it hardens). Beneath the shed exoskeleton is a new, soft exoskeleton, which immediately grows larger before it hardens up. Pillbugs are different in that they first shed the exoskeleton on their back half. Then a few days later they shed the front half.

Check out this cool video of pillbugs molting.

Pillbugs walk around on seven pairs of legs. Strangely, though, when baby pillbugs hatch, they only have six pairs of legs. They don't get the seventh pair until after they molt for the first time.

Pillbugs eat decaying matter on the forest floor and under rocks and logs. They also eat their own poop. That's right. It's a real thing among may animals, and it is called coprophagy. Other animals do it for different reasons, but pillbugs do it to conserve copper. Pillbugs need copper in their bodies, and they lose some of it every time they poop. So they have a habit of eating their poop to conserve the copper.

Female pillbugs carry their babies around on their underneath side. The eggs are layed and then transferred to the marsupium (similar in function to a marsupial's pouch). The eggs hatch in the marsupium, and then the young hang on to the mother's underside for eight to twelve weeks as they develop.

Okay, so I have to talk a bit about the The Pillbug Project (the actual title of a project I did with my 7th graders back in my teaching days). We formed a partnership with a dozen or so other schools in North America. The students in each partner class went out and collected pillbugs in their area. We then carried out a series of experiments with the pillbugs to see how well adapted they were to the climate in their area of the continent. These were simple choice experiments. For example, put the pillbugs in a container that is dry on one side and moist on the other side. After a specific amount of time, count how many are on each side. We did the same thing with warm and cool sides, light and dark sides, etc. Not surprisingly, we found that the ones from warm, dry areas of the continent were more comfortable on the dry side and on the warm side. Those from cooler, wetter regions were more comfortable on the cool side and wet side. And so on. There were many more experiments involved, but you get the idea.

We also worked collaboratively with the students at the other schools to write a fun book about an intelligent pillbug from the future that travels back in time to teach a pair of teens about the history of life on Earth. This pillbug, named Armadillia, had a nifty little time machine attached to a belt around his waist. Below is a drawing one of my students created, his vision of what this fictional character should look like.

So, the Pillbug deserves a place in the F.A.H.O.F. (Fetch Animal Hall of Fame).

So, the Pillbug deserves a place in the F.A.H.O.F. (Fetch Animal Hall of Fame).FUN FACT: The word fetch in this usage is, I suppose, a reduction of fetching, which means "attractive." Okay, I must admit, using the word fetch in this context isn't really a thing. It comes from the 2004 movie, Mean Girls, in which Gretchen tries to make fetch a thing but gets shut down by her friend, Regina George. Here's the clip. In spite of Gretchen's efforts, in the 14 years since the movie came out, fetch still isn't catching on. But Regina's response ("Stop trying to make Fetch happen!)" has now become a way to mock people who are out of touch. So... for Gretchen's sake, I'm going to say that fetch is another way to say awesome!

Photo Credits:

Pillbug #1 - on finger - Backyard Nature

Pillbug rolled up - James Castner, University of Florida.

Pillbug Shedding - Backyard Nature

Pillbug Babies - The Living Classroom

Published on October 20, 2018 03:37

Quick bonus animal - the Caracara

Trish and I recently flew down to Texas to spend a bit of time with the family of one of our daughters in El Campo (southeast of Houston). They have a small farm there, and I had the opportunity to help with a few tasks. I did not grow up on a farm, and I have little farm experience, but I was recruited to help with moving a sun shelter (for pigs) from one field to another. I can honestly say this was the first time I have wallowed in pig mud. I now understand why pigs enjoy it.

While Trish and I were on a walk on the outskirts of El Campo, we saw an impressive bird for the first time, the Caracara .

Here's a bit of interesting background on the caracara. This bird is also known as the Mexican eagle, but it actually isn't an eagle at all, it is a relative of the falcons, and it likes eating roadkill more than hunting. The bird used to have the honor of being the national bird of Mexico. But it was downgraded not too long ago. Why? Because the Mexican state department took a closer look at the bird on the national seal and decided it was a golden eagle, not a caracara.

The bird on the national seal goes back to native Aztec legend. According to the legend, the sun god, named Huitzilopochtli, asked the people to find an eagle perching on a cactus and eating a snake, and that's the spot where they should build their new town. The town was called Tenochtitlan but later became known as Mexico City.

At some point, someone decided the bird was a caracara. The problem, though, is that the caracara wasn't common in that area, and it didn't look much like the bird on the seal. But the golden eagle is common there and does look like the bird on the seal!

Anyway, the caracara isn't my chosen Awesome Animal for this week (that's the Pillbug), but I thought I would share this tidbits.

Photo Credits:

Wallowing in mud - Trish Smith

Crested Caracara - Bay City Tribune

While Trish and I were on a walk on the outskirts of El Campo, we saw an impressive bird for the first time, the Caracara .

Here's a bit of interesting background on the caracara. This bird is also known as the Mexican eagle, but it actually isn't an eagle at all, it is a relative of the falcons, and it likes eating roadkill more than hunting. The bird used to have the honor of being the national bird of Mexico. But it was downgraded not too long ago. Why? Because the Mexican state department took a closer look at the bird on the national seal and decided it was a golden eagle, not a caracara.

The bird on the national seal goes back to native Aztec legend. According to the legend, the sun god, named Huitzilopochtli, asked the people to find an eagle perching on a cactus and eating a snake, and that's the spot where they should build their new town. The town was called Tenochtitlan but later became known as Mexico City.

At some point, someone decided the bird was a caracara. The problem, though, is that the caracara wasn't common in that area, and it didn't look much like the bird on the seal. But the golden eagle is common there and does look like the bird on the seal!

Anyway, the caracara isn't my chosen Awesome Animal for this week (that's the Pillbug), but I thought I would share this tidbits.

Photo Credits:

Wallowing in mud - Trish Smith

Crested Caracara - Bay City Tribune

Published on October 20, 2018 03:32

October 11, 2018

Awesome Animal - Tree Kangaroo

In honor of the upcoming re-release of

Diffusion

, today's awesome animal is the Tree Kangaroo. Way back in 2016, I briefly described these creatures in one of my newsletters, but now it's time to give them the full treatment. After all, tree kangaroos are perhaps the most iconic creature of the

Diffusion

series.

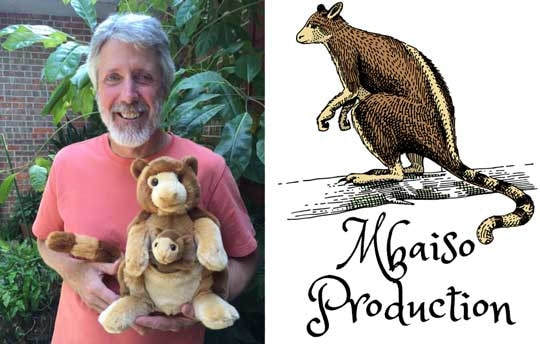

I take a toy tree kangaroo to book signings, and one is included on the copyright page of the new versions of the Diffusion books:

It is high time I expound upon this creature’s awesomeness. Yes, tree kangaroos are real! They live on the island of New Guinea, but also in very northern Australia and some of the Indonesian islands. Why are tree kangaroos so cool? Well, because they’re kangaroos—that live in trees! When Australian Aborigines and Papuan (New Guinea) natives told early European explorers about tree kangaroos, the explorers refused to believe the stories. You have to admit it seems pretty unlikely, right?

It is high time I expound upon this creature’s awesomeness. Yes, tree kangaroos are real! They live on the island of New Guinea, but also in very northern Australia and some of the Indonesian islands. Why are tree kangaroos so cool? Well, because they’re kangaroos—that live in trees! When Australian Aborigines and Papuan (New Guinea) natives told early European explorers about tree kangaroos, the explorers refused to believe the stories. You have to admit it seems pretty unlikely, right?

So what the heck is a Tree Kangaroo??

Tree kangaroos are marsupials, in the genus Dendrolagus. There are about 14 different species, but this is one of very few types of large mammals with species still being discovered. Most tree kangaroos are about the size of a housecat. They are a fascinating example of divergent evolution (when groups of similar creatures become isolated and gradually diverge in form and function). Long ago, groups of ground-dwelling kangaroos became isolated in areas of dense tropical forest, as opposed to the open grasslands more typical for kangaroos. Once isolated in rainforest areas, they developed the ability to climb trees.

Amazing facts about Tree Kangaroos

These creatures eat, sleep, and breed in the treetops, but that doesn’t mean they live a comfortable existence. First of all, I imagine breeding in the treetops requires some caution (yikes!). Second, they seem to be a tasty meal for their primary predator, the amethystine python (which has a habit of hugging much too tightly). Third, natives hunt them for food (In New Guinea, "the man who has successfully hunted a tree-kangaroo has greatness bestowed upon him. He has conquered the largest, most prestigious and human-like marsupial known to his people." [Tim Flannery, from the awesome book, Throwim Way Leg]). And fourth, they depend on pristine rainforest, and if you haven’t heard, rainforests are getting smaller every day (a real bummer).

Tree kangaroos are reclusive. Some are extremely rare and live in places so remote that they are unusually tame, as they have never learned to fear humans. Just a few days ago, National Geographic published an article about the Wondowoi Tree Kangaroo, a species that had not been spotted since 1929 (ninety years ago!). It was thought to be extinct, until an amatuer botonist led an expedition into the nearly-impenetrable bamboo forests of the Wondiwoi Mountains of West Papua to find it. After much searching, he took the first ever photographs of this species:

The Papuan people of New Guinea have numerous ancient myths about tree kangaroos, some of which play a role in the Diffusion novels. For example, one of the main characters of the novels is a tree kangaroo named Mbaiso (at least it looks like a tree kangaroo... all is not what it seems in Diffusion ). The name comes from a rare tree kangaroo, Dingiso mbaiso, which is revered by the local Moni people as an ancestor. When describing encounters with these animals, the tribesmen hunters say the creatures sit up, whistle, and hold up their paws in greeting. So the Moni believe the creatures are ancestor spirits who recognize them.

Another interesting story, this one about the Matschie’s Tree Kangaroo, is that the creature has a special power. If you think of the girl you love before you let your arrow fly to shoot this tree kangaroo, at the moment the arrow pierces the animal’s body, that’s when the girl will fall in love with you.

Below is the Matschie's tree kangaroo:

Tree kangaroos really are adapted to life in the trees. Compared to ground kangaroos, they have longer, curved nails for gripping the bark. Their hind feet are longer, and they have spongy, padded grips on their palms and the soles of their feet. Perhaps most striking is their tail. It is longer and heavier than those of ground kangaroos, which gives them better balance as they climb. When they climb straight up a tree trunk, they wrap their forearms around the tree and use their powerful hind legs to "hop" up the tree.

They are terrific jumpers. They can leap from one branch to another that is thirty feet (9m) below them. And, this may be hard to believe, but they can leap to the ground from as high as sixty feet (19m) without getting hurt! Considering adults can weigh 25 to 30 pounds (11 to 14kg), this is amazing!

Check out this fun Animalogic video about Tree Kangaroos.

As mentioned above, tree kangaroos are marsupials. And you know what that means, right? It means they give birth to their babies very early, and then the babies develop in an external pouch. The babies are only the size of jellybeans at birth. At that point, about the only parts of their external anatomy that are well developed are their hands and mouth. They use their hands to crawl to the pouch, then they attach their mouth to a nipple and hang on. For a long time. Astoundingly, baby tree kangaroos stay in the mother's pouch for up to 275 days. And then, after they come out, they are not weaned for up to another 240 days!

One more little tidbit. You may have noticed that tree kangaroos look quite a bit like teddy bears. To illustrate how true this is, recently a photo emerged on the internet. It was taken at the Perth Zoo, of a mother Goodfellow's tree kangaroo with a baby in her pouch (the first tree kangaroo baby born at the zoo in 36 years). The creatures looked so cute and teddy-bear-like that many people thought the photo was a fake, just a photo of a stuffed toy. But, of course, the photo was indeed real:

So, the Tree Kangaroo deserves a place in the L.A.H.O.F.

So, the Tree Kangaroo deserves a place in the L.A.H.O.F.

(Legit Animal Hall of Fame).

FUN FACT: The word legit is, of course, a reduction of legitimate, which means "conforming to the law or to the rules." The earliest citation for use of the shorter version, legit, is from 1897. But in recent years it has been used as a slang word to mean that something is either credible or that it is cool. I think this word is appropriate for tree kangaroos because some people are surprised that these creatures are even real. AND, because these creatures are definitely cool! So, legit is another way to say awesome!

Photo Credits:

250-million-year-old bacterium - Bioprocess Online

Goodfellows Tree Kangaroo #1 - Currumbin Wildlife Sanctuary

Wondowoi Tree Kangaroo - Michael Smith (National Geographic)

Matschie's Tree kangaroo- San Diego Zoo

Baby Goodfellow's Tree Kangaroo in pouch - ZooBorns

Goodfellow's Kangaroo and baby - Perth Zoo

I take a toy tree kangaroo to book signings, and one is included on the copyright page of the new versions of the Diffusion books:

It is high time I expound upon this creature’s awesomeness. Yes, tree kangaroos are real! They live on the island of New Guinea, but also in very northern Australia and some of the Indonesian islands. Why are tree kangaroos so cool? Well, because they’re kangaroos—that live in trees! When Australian Aborigines and Papuan (New Guinea) natives told early European explorers about tree kangaroos, the explorers refused to believe the stories. You have to admit it seems pretty unlikely, right?

It is high time I expound upon this creature’s awesomeness. Yes, tree kangaroos are real! They live on the island of New Guinea, but also in very northern Australia and some of the Indonesian islands. Why are tree kangaroos so cool? Well, because they’re kangaroos—that live in trees! When Australian Aborigines and Papuan (New Guinea) natives told early European explorers about tree kangaroos, the explorers refused to believe the stories. You have to admit it seems pretty unlikely, right?

So what the heck is a Tree Kangaroo??

Tree kangaroos are marsupials, in the genus Dendrolagus. There are about 14 different species, but this is one of very few types of large mammals with species still being discovered. Most tree kangaroos are about the size of a housecat. They are a fascinating example of divergent evolution (when groups of similar creatures become isolated and gradually diverge in form and function). Long ago, groups of ground-dwelling kangaroos became isolated in areas of dense tropical forest, as opposed to the open grasslands more typical for kangaroos. Once isolated in rainforest areas, they developed the ability to climb trees.

Amazing facts about Tree Kangaroos

These creatures eat, sleep, and breed in the treetops, but that doesn’t mean they live a comfortable existence. First of all, I imagine breeding in the treetops requires some caution (yikes!). Second, they seem to be a tasty meal for their primary predator, the amethystine python (which has a habit of hugging much too tightly). Third, natives hunt them for food (In New Guinea, "the man who has successfully hunted a tree-kangaroo has greatness bestowed upon him. He has conquered the largest, most prestigious and human-like marsupial known to his people." [Tim Flannery, from the awesome book, Throwim Way Leg]). And fourth, they depend on pristine rainforest, and if you haven’t heard, rainforests are getting smaller every day (a real bummer).

Tree kangaroos are reclusive. Some are extremely rare and live in places so remote that they are unusually tame, as they have never learned to fear humans. Just a few days ago, National Geographic published an article about the Wondowoi Tree Kangaroo, a species that had not been spotted since 1929 (ninety years ago!). It was thought to be extinct, until an amatuer botonist led an expedition into the nearly-impenetrable bamboo forests of the Wondiwoi Mountains of West Papua to find it. After much searching, he took the first ever photographs of this species:

The Papuan people of New Guinea have numerous ancient myths about tree kangaroos, some of which play a role in the Diffusion novels. For example, one of the main characters of the novels is a tree kangaroo named Mbaiso (at least it looks like a tree kangaroo... all is not what it seems in Diffusion ). The name comes from a rare tree kangaroo, Dingiso mbaiso, which is revered by the local Moni people as an ancestor. When describing encounters with these animals, the tribesmen hunters say the creatures sit up, whistle, and hold up their paws in greeting. So the Moni believe the creatures are ancestor spirits who recognize them.

Another interesting story, this one about the Matschie’s Tree Kangaroo, is that the creature has a special power. If you think of the girl you love before you let your arrow fly to shoot this tree kangaroo, at the moment the arrow pierces the animal’s body, that’s when the girl will fall in love with you.

Below is the Matschie's tree kangaroo:

Tree kangaroos really are adapted to life in the trees. Compared to ground kangaroos, they have longer, curved nails for gripping the bark. Their hind feet are longer, and they have spongy, padded grips on their palms and the soles of their feet. Perhaps most striking is their tail. It is longer and heavier than those of ground kangaroos, which gives them better balance as they climb. When they climb straight up a tree trunk, they wrap their forearms around the tree and use their powerful hind legs to "hop" up the tree.

They are terrific jumpers. They can leap from one branch to another that is thirty feet (9m) below them. And, this may be hard to believe, but they can leap to the ground from as high as sixty feet (19m) without getting hurt! Considering adults can weigh 25 to 30 pounds (11 to 14kg), this is amazing!

Check out this fun Animalogic video about Tree Kangaroos.

As mentioned above, tree kangaroos are marsupials. And you know what that means, right? It means they give birth to their babies very early, and then the babies develop in an external pouch. The babies are only the size of jellybeans at birth. At that point, about the only parts of their external anatomy that are well developed are their hands and mouth. They use their hands to crawl to the pouch, then they attach their mouth to a nipple and hang on. For a long time. Astoundingly, baby tree kangaroos stay in the mother's pouch for up to 275 days. And then, after they come out, they are not weaned for up to another 240 days!

One more little tidbit. You may have noticed that tree kangaroos look quite a bit like teddy bears. To illustrate how true this is, recently a photo emerged on the internet. It was taken at the Perth Zoo, of a mother Goodfellow's tree kangaroo with a baby in her pouch (the first tree kangaroo baby born at the zoo in 36 years). The creatures looked so cute and teddy-bear-like that many people thought the photo was a fake, just a photo of a stuffed toy. But, of course, the photo was indeed real:

So, the Tree Kangaroo deserves a place in the L.A.H.O.F.

So, the Tree Kangaroo deserves a place in the L.A.H.O.F.(Legit Animal Hall of Fame).

FUN FACT: The word legit is, of course, a reduction of legitimate, which means "conforming to the law or to the rules." The earliest citation for use of the shorter version, legit, is from 1897. But in recent years it has been used as a slang word to mean that something is either credible or that it is cool. I think this word is appropriate for tree kangaroos because some people are surprised that these creatures are even real. AND, because these creatures are definitely cool! So, legit is another way to say awesome!

Photo Credits:

250-million-year-old bacterium - Bioprocess Online

Goodfellows Tree Kangaroo #1 - Currumbin Wildlife Sanctuary

Wondowoi Tree Kangaroo - Michael Smith (National Geographic)

Matschie's Tree kangaroo- San Diego Zoo

Baby Goodfellow's Tree Kangaroo in pouch - ZooBorns

Goodfellow's Kangaroo and baby - Perth Zoo

Published on October 11, 2018 05:49

September 20, 2018

Awesome Animal - Duck-billed Platypus

The platypus is arguably the most bizarre mammal alive today (although I wouldn't rule out naked mole rats, pangolins, or humans).

In April and May, Trish and I were lucky enough to spend over three weeks in the tropical northeast corner of Australia. When we were staying at Hidden Valley Cabins near Paluma, Ian (one of the owners) took us to a nearby river to try to spot the elusive platypus. We sat silently by the shore of the river as the sun set and the surrounding forest became dark, but the creatures were unwilling to show themselves. Ian was as disappointed as we were, so he insisted on taking us again the next evening. This time we saw two platypuses, and we were ecstatic. Due to our success, Ian ceremoniously gave us each an Australian 20-cent coin, which features a platypus.

At first glance, a platypus could be mistaken for a water mammal that is very common in my home state of Missouri, the muskrat. I've seen plenty of muskrats (and beavers, for that matter), so why was I so excited to see a platypus? Because the platypus is unlike any other mammal on Earth--an egg-laying, duck-billed mammal with venomous stingers on its hind feet! It is so bizarre that the first scientists to examine a preserved platypus in 1799 declared that it was a fake. they thought someone had sewn together the parts from several different animals.

So what the heck is a Platypus?

The platypus is a mammal in the order, monotremes (along with echidnas, which I featured in a previous email). It is the only living member of a monotreme family called Ornithorhynchidae . The most amazing thing about monotremes is that they lay eggs instead of giving birth to live young. The platypus has become an iconic animal of Australia.

Amazing facts about the Platypus

The platypus has many names. No one seems to agree on the correct plural form of the word, platypus. Some scientists use the word "platypuses," while others use "platypus." Some Australians use the word, "platypi." Early settlers in Australia referred to them as "duckbills," "watermoles," and "duckmoles."

Long ago (before about 60 million years), monotremes were the dominant mammals throughout Australia. There were many more species of monotremes at that time. But then marsupials invaded Australia (marsupials are the pouched mammals like kangaroos, koalas, and possums). It is thought that the marsupials were able to out-compete the monotremes, gradually replacing nearly all of them.

So, why did the platypuses and echidnas survive? Probably because of an aquatic (swimming) lifestyle. Yes, I know that echidnas are terrestrial animals, but recent studies show that their ancestors that existed when marsupials invaded Australia were more similar to platypuses. Echidnas diverged from platypuses less than 50 million years ago.

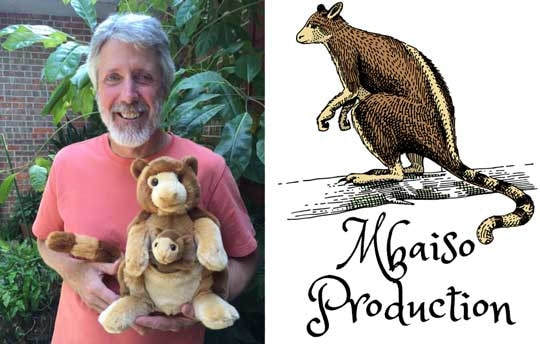

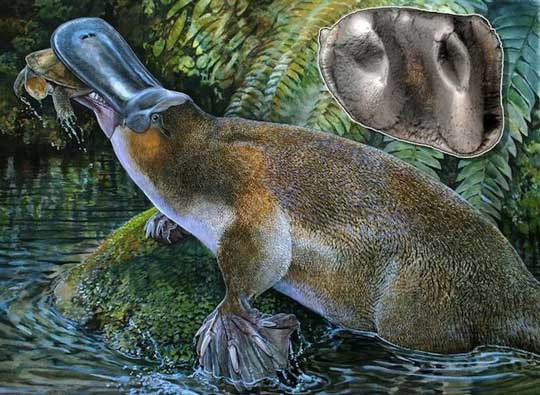

Platypuses are fairly small mammals. Females average 17 inches (43 cm) in length, including the tail. Males average 20 inches (50 cm). But based on fossil teeth, we now know that at least one much larger species existed millions of years ago. At about a meter long, it was twice the size of modern platypuses. See artist drawing below.

Why do platypuses have a duck bill? The bill is a special adaptation for feeding on invertebrates that dwell in the bottom substrate of creeks and ponds. The platypus swipes its bill back and forth to expose their prey animals. Even more amazing, though, is that not only are these bills highly sensitive to touch, they also have rows of electroreceptors, which allow the platypus to locate their prey by detecting the tiny electric signals generated by muscle contractions in their prey. Therefore, the way they feed is similar to that of hammerhead sharks.

Platypuses are venomous! The males have spurs on their hind legs that inject venom that causes extreme pain, and can even kill animals as large as cats and dogs. The main purpose of these spurs is probably to aid the males in fighting each other during the mating season, but they can also be used in self-defense.

Another interesting fact is that similar spurs have been found on the legs of many fossilized ancient mammals. So even though platypuses are one of only a few venomous mammals alive today, apparently venom was common in mammals in the past.

Check out this National Geographic video on platypuses.

Platypuses really do lay eggs. Astoundingly, because platypus nests are difficult to find, it wasn't until 1884 that scientists confirmed that they actually lay eggs (almost 100 years after Europeans first encountered these creatures). In 1884, the British scientist William Caldwell was sent to Australia to confirm this. With the help of 150 native Aborigines, he finally located a nest with a few eggs. Because of the high cost of wiring numerous words from Australia to London, he sent the following brief message: "Monotremes oviparous, ovum meroblastic." What does this mean? It means, "monotremes lay eggs, and the eggs are similar to those of reptiles in that only part of the egg divides as it develops."

The reason platypus nests are so difficult to find is that the females construct them in extensive burrows, up to 66 feet (20 m) long, near the water's edge. The photo below is a replica of a platypus nest with eggs.

Platypus eggs develop inside the female's body for about 28 days, then they are incubated in the nest for only ten days. This is very different from birds. For example, in chickens, the egg spends only about one day in the female's body and is then incubated outside the body for 21 days.

Check out this rare video of hatching platypuses.

And here are two young platypuses:

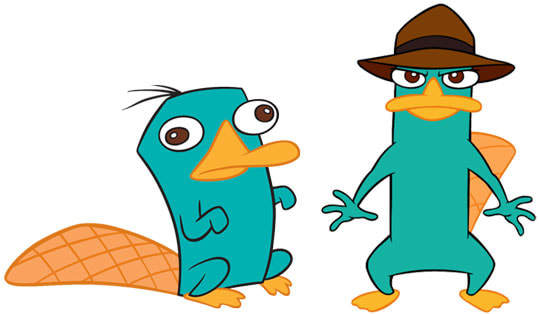

One more little tidbit of information. Not only is the platypus included in Aboriginal "Dreamtime" stories, it is also featured on numerous Australian coins and stamps, and it was one of the mascots chosen for the Sydney 2000 Olympics. Perhaps today it is best known to kids because of the character, Perry the Platypus, in the animated TV show, Phineas and Ferb . Perry is a pet platypus, but unbeknownst to his owners, he leads a double life. He is also a secret agent for The O.W.C.A. (The Organization Without a Cool Acronym), a government organization of animal spies.

So, the platypus deserves a place in the S.A.H.O.F.

(Supernacular Animal Hall of Fame).

FUN FACT: The word supernacular originated in the 1840s. Originally it was used to describe a drink (particularly an alcoholic drink) that was excellent, or good to the last drop. But since then it has been used more broadly to mean superb or outstanding. So, supernacular is another way to say awesome!

Photo Credits:

Kansas State Fair - Painted-face Sisters - Stan C. Smith

Midway at night - Stan C. Smith

Platypus Head - Zoos Victoria

Large Extinct Platypus - Peter Schouten, SciNews

Platypus Nest - Wikimedia Commons

Baby Platypuses - Imgur

Perry the Platypus - Fandom

In April and May, Trish and I were lucky enough to spend over three weeks in the tropical northeast corner of Australia. When we were staying at Hidden Valley Cabins near Paluma, Ian (one of the owners) took us to a nearby river to try to spot the elusive platypus. We sat silently by the shore of the river as the sun set and the surrounding forest became dark, but the creatures were unwilling to show themselves. Ian was as disappointed as we were, so he insisted on taking us again the next evening. This time we saw two platypuses, and we were ecstatic. Due to our success, Ian ceremoniously gave us each an Australian 20-cent coin, which features a platypus.

At first glance, a platypus could be mistaken for a water mammal that is very common in my home state of Missouri, the muskrat. I've seen plenty of muskrats (and beavers, for that matter), so why was I so excited to see a platypus? Because the platypus is unlike any other mammal on Earth--an egg-laying, duck-billed mammal with venomous stingers on its hind feet! It is so bizarre that the first scientists to examine a preserved platypus in 1799 declared that it was a fake. they thought someone had sewn together the parts from several different animals.

So what the heck is a Platypus?

The platypus is a mammal in the order, monotremes (along with echidnas, which I featured in a previous email). It is the only living member of a monotreme family called Ornithorhynchidae . The most amazing thing about monotremes is that they lay eggs instead of giving birth to live young. The platypus has become an iconic animal of Australia.

Amazing facts about the Platypus

The platypus has many names. No one seems to agree on the correct plural form of the word, platypus. Some scientists use the word "platypuses," while others use "platypus." Some Australians use the word, "platypi." Early settlers in Australia referred to them as "duckbills," "watermoles," and "duckmoles."

Long ago (before about 60 million years), monotremes were the dominant mammals throughout Australia. There were many more species of monotremes at that time. But then marsupials invaded Australia (marsupials are the pouched mammals like kangaroos, koalas, and possums). It is thought that the marsupials were able to out-compete the monotremes, gradually replacing nearly all of them.

So, why did the platypuses and echidnas survive? Probably because of an aquatic (swimming) lifestyle. Yes, I know that echidnas are terrestrial animals, but recent studies show that their ancestors that existed when marsupials invaded Australia were more similar to platypuses. Echidnas diverged from platypuses less than 50 million years ago.

Platypuses are fairly small mammals. Females average 17 inches (43 cm) in length, including the tail. Males average 20 inches (50 cm). But based on fossil teeth, we now know that at least one much larger species existed millions of years ago. At about a meter long, it was twice the size of modern platypuses. See artist drawing below.

Why do platypuses have a duck bill? The bill is a special adaptation for feeding on invertebrates that dwell in the bottom substrate of creeks and ponds. The platypus swipes its bill back and forth to expose their prey animals. Even more amazing, though, is that not only are these bills highly sensitive to touch, they also have rows of electroreceptors, which allow the platypus to locate their prey by detecting the tiny electric signals generated by muscle contractions in their prey. Therefore, the way they feed is similar to that of hammerhead sharks.

Platypuses are venomous! The males have spurs on their hind legs that inject venom that causes extreme pain, and can even kill animals as large as cats and dogs. The main purpose of these spurs is probably to aid the males in fighting each other during the mating season, but they can also be used in self-defense.

Another interesting fact is that similar spurs have been found on the legs of many fossilized ancient mammals. So even though platypuses are one of only a few venomous mammals alive today, apparently venom was common in mammals in the past.

Check out this National Geographic video on platypuses.

Platypuses really do lay eggs. Astoundingly, because platypus nests are difficult to find, it wasn't until 1884 that scientists confirmed that they actually lay eggs (almost 100 years after Europeans first encountered these creatures). In 1884, the British scientist William Caldwell was sent to Australia to confirm this. With the help of 150 native Aborigines, he finally located a nest with a few eggs. Because of the high cost of wiring numerous words from Australia to London, he sent the following brief message: "Monotremes oviparous, ovum meroblastic." What does this mean? It means, "monotremes lay eggs, and the eggs are similar to those of reptiles in that only part of the egg divides as it develops."

The reason platypus nests are so difficult to find is that the females construct them in extensive burrows, up to 66 feet (20 m) long, near the water's edge. The photo below is a replica of a platypus nest with eggs.

Platypus eggs develop inside the female's body for about 28 days, then they are incubated in the nest for only ten days. This is very different from birds. For example, in chickens, the egg spends only about one day in the female's body and is then incubated outside the body for 21 days.

Check out this rare video of hatching platypuses.

And here are two young platypuses:

One more little tidbit of information. Not only is the platypus included in Aboriginal "Dreamtime" stories, it is also featured on numerous Australian coins and stamps, and it was one of the mascots chosen for the Sydney 2000 Olympics. Perhaps today it is best known to kids because of the character, Perry the Platypus, in the animated TV show, Phineas and Ferb . Perry is a pet platypus, but unbeknownst to his owners, he leads a double life. He is also a secret agent for The O.W.C.A. (The Organization Without a Cool Acronym), a government organization of animal spies.

So, the platypus deserves a place in the S.A.H.O.F.

(Supernacular Animal Hall of Fame).

FUN FACT: The word supernacular originated in the 1840s. Originally it was used to describe a drink (particularly an alcoholic drink) that was excellent, or good to the last drop. But since then it has been used more broadly to mean superb or outstanding. So, supernacular is another way to say awesome!

Photo Credits:

Kansas State Fair - Painted-face Sisters - Stan C. Smith

Midway at night - Stan C. Smith

Platypus Head - Zoos Victoria

Large Extinct Platypus - Peter Schouten, SciNews

Platypus Nest - Wikimedia Commons

Baby Platypuses - Imgur

Perry the Platypus - Fandom

Published on September 20, 2018 10:35

September 1, 2018

Awesome Animal - Moose

Trish and I recently completed a seven-day wilderness canoe trip in the Boundary Waters Canoe Area in northern Minnesota. Well, this time we took two grandsons with us, ages 16 and 18.

Do you have any idea how attached today's teens are to their digital devices and other technology? To me, the idea of not having any technology for a week sounds like bliss (sure, I love technology, but I love nature even more). But if you mention this possibility to teenagers, their heads might explode. Yep, it's that traumatic.

But grandsons Ellis and Gabe were real troopers. They both love to go fishing, and they seemed to enjoy every minute of the adventure (although they had digital devices in their hands within seconds of returning to our vehicle).

I do believe all the paddling and portaging may have worn them out a few times...

One day, the two boys went out in their canoe to explore one of the lakes. They spotted a moose antler resting on the bottom of the lake. Somehow (perhaps I don't want to know all the details) they managed to retrieve the antler and they brought it to the campsite (we left it there for others to enjoy... there are rules against taking such things home). If this antler hadn't been submerged in water, it would have been eaten by squirrels and mice months ago.

A few days later we saw a bull moose swimming across the lake. These moose-related events are why I chose today's awesome animal.

Awesome Animal - Moose

The only place I've seen these amazing creatures is during our annual canoe trips to the Boundary Waters Canoe Area in northern Minnesota. Unfortunately, their numbers are decreasing in that area due to the worldwide warming trend. The moose and wolf populations are moving northward, with white-tailed deer and coyote populations moving up and taking their place.

I have nothing against white-tailed deer and coyotes, but I see them all the time here in Missouri. When we travel north to the border of Canada, we enjoy seeing those animals that we think of as traditional "Northwoods" creatures. It's sad that the next generation of BWCA paddlers will see very few (if any) moose or wolves in that area.

But we're still seeing a few of them. Here is a cow moose and her calf that Trish and I saw a few years ago:

So what the heck is a Moose?

The moose (Alces alces) is the largest species of the deer family (Cervidae). They are immediately recognizable to most people, with a distinctly bulbous snout that sets them apart from other large deer such as the North American elk.

But the names moose and elk can be confusing. Why? Because in Europe, moose are called elk. And to confuse things even more, in North America there is another large deer species called the elk (Cervus canadensis, also called the wapiti). So the American elk is not a moose, but the European moose is actually an elk. Makes perfect sense, right?

Amazing facts about Moose

Yep, the plural form of moose is moose. Not mooses, or meeses, or mice.

Moose are big! Adults stand 4.5 to 7 feet (1.4 to 2.1 meters) tall at the shoulder. This is at least a foot (30.5 cm) taller than the next tallest deer, the American elk. Bulls weigh up to 1,500 pounds (680 kg). Cows are somewhat smaller, up to 1,080 pounds (490 kg). The bulls' antlers can span six feet (1.8 m). The moose is the second largest land animal in both North America and Europe (only the bison is larger).

I've always been fascinated by animals that grow antlers (which fall off and are regrown each year) versus animals that grow horns (which continue to grow without falling off). Consider this: a bull moose's pair of antlers can weigh up to 60 pounds (27 kg). Imagine how strong their necks have to be to lug this weight around! And imagine how strange it must feel to the moose when the first one falls off each year (they rarely fall off at the same time). If I had a 30-pound antler on one side of my head, I would probably find myself walking in circles.

Check out this video of a moose shedding one antler (I love the family's comments as they are recording this).

Antlers are very important to male moose (and all deer) in obtaining mates (larger antlers help them in their dominance over other males), but they shed these antlers in the fall to save energy over the long winter.

A male moose also has a large "beard" hanging below its chin, made of hair and loose skin. This is called a dewlap (females have them, too, but they are smaller). Oddly, no one is sure exactly what the dewlap is for. Some biologists suggest that it helps the males spread their scent (in the form of urine) onto trees to mark their territory or onto females (isn't that romantic?).

Now, here's a weird fact about moose antlers. If a bull moose is castrated (um... maybe by an attacking wolf or by trying to jump over something?), his antlers will quickly fall off. Soon after, he will grow a new set of antlers, but these will be oddly shaped and deformed. And this new set of antlers never falls off. Yep, the moose wears them the rest of his life. This happens often enough that these strangely-shaped antlers have a name--"devil's antlers." Native Americans have several myths regarding such antlers. See the photo below.

One more bit about the moose in popular culture. For some reason (possibly the moose's goofy looks), moose are extremely popular in cartoons and children's books. Dr. Suess wrote a beloved book titled Thidwick the Big-Hearted Moose. And then there's If You Give a Moose a Muffin by Laura Numeroff, as well as many more. There's the craft beer called Moose Drool, from Big Sky Brewing in Montana. By the way, I used to brew my own beer, and once I used a recipe that was supposed to resemble Moose Drool, but instead it was called Caribou Slobber... but I digress.

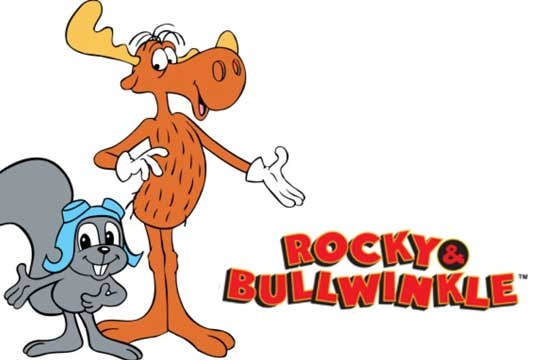

There are countless moose products, from moose-shaped coffee mugs to moose toilet paper holders. But perhaps my favorite pop culture moose is Bullwinkle. Bullwinkle J. Moose is a character from an old cartoon TV show that played from 1959 to 1964. You know... back when they made the really good cartoons. Repeats of this awesome show have been playing for over 50 years. In 1996, Bullwinkle was rated by TV Guide as the #32 greatest TV star of all time. Although Bullwinkle was rather dim-witted, he was balanced out by his smarter partner, the flying squirrel named Rocky.

Hmmm....I wonder if I can find these shows on Netflix or DVD...

So, the moose deserves a place in the R.A.H.O.F.

(Righteous Animal Hall of Fame).

FUN FACT: The word righteous originated before the year 900, so it has been around for a while. It started as the Middle English word rightwos but eventually became righteous. Original meaning: someone characterized by uprightness and morality (hmm... that sounds like Bullwinkle to me). Eventually, though, a slang form came to mean absolutely genuine or wonderful, as in, "That ice cream was righteous!" Or, "Did you see Chuck Norris beat up those bad guys? That was righteous!" So, righteous is another way to say awesome!

Photo Credits:

Boundary Waters photo of cow moose with calf - Stan C. Smith

Bull moose #1 - National Park Service

Bull Moose with dewlap - Pinterest

Devil's Antlers - Mary Anning's Revenge

Rocky and Bullwinkle - Dreamworks Wiki

Do you have any idea how attached today's teens are to their digital devices and other technology? To me, the idea of not having any technology for a week sounds like bliss (sure, I love technology, but I love nature even more). But if you mention this possibility to teenagers, their heads might explode. Yep, it's that traumatic.

But grandsons Ellis and Gabe were real troopers. They both love to go fishing, and they seemed to enjoy every minute of the adventure (although they had digital devices in their hands within seconds of returning to our vehicle).

I do believe all the paddling and portaging may have worn them out a few times...

One day, the two boys went out in their canoe to explore one of the lakes. They spotted a moose antler resting on the bottom of the lake. Somehow (perhaps I don't want to know all the details) they managed to retrieve the antler and they brought it to the campsite (we left it there for others to enjoy... there are rules against taking such things home). If this antler hadn't been submerged in water, it would have been eaten by squirrels and mice months ago.

A few days later we saw a bull moose swimming across the lake. These moose-related events are why I chose today's awesome animal.

Awesome Animal - Moose

The only place I've seen these amazing creatures is during our annual canoe trips to the Boundary Waters Canoe Area in northern Minnesota. Unfortunately, their numbers are decreasing in that area due to the worldwide warming trend. The moose and wolf populations are moving northward, with white-tailed deer and coyote populations moving up and taking their place.

I have nothing against white-tailed deer and coyotes, but I see them all the time here in Missouri. When we travel north to the border of Canada, we enjoy seeing those animals that we think of as traditional "Northwoods" creatures. It's sad that the next generation of BWCA paddlers will see very few (if any) moose or wolves in that area.

But we're still seeing a few of them. Here is a cow moose and her calf that Trish and I saw a few years ago:

So what the heck is a Moose?

The moose (Alces alces) is the largest species of the deer family (Cervidae). They are immediately recognizable to most people, with a distinctly bulbous snout that sets them apart from other large deer such as the North American elk.

But the names moose and elk can be confusing. Why? Because in Europe, moose are called elk. And to confuse things even more, in North America there is another large deer species called the elk (Cervus canadensis, also called the wapiti). So the American elk is not a moose, but the European moose is actually an elk. Makes perfect sense, right?

Amazing facts about Moose

Yep, the plural form of moose is moose. Not mooses, or meeses, or mice.

Moose are big! Adults stand 4.5 to 7 feet (1.4 to 2.1 meters) tall at the shoulder. This is at least a foot (30.5 cm) taller than the next tallest deer, the American elk. Bulls weigh up to 1,500 pounds (680 kg). Cows are somewhat smaller, up to 1,080 pounds (490 kg). The bulls' antlers can span six feet (1.8 m). The moose is the second largest land animal in both North America and Europe (only the bison is larger).

I've always been fascinated by animals that grow antlers (which fall off and are regrown each year) versus animals that grow horns (which continue to grow without falling off). Consider this: a bull moose's pair of antlers can weigh up to 60 pounds (27 kg). Imagine how strong their necks have to be to lug this weight around! And imagine how strange it must feel to the moose when the first one falls off each year (they rarely fall off at the same time). If I had a 30-pound antler on one side of my head, I would probably find myself walking in circles.

Check out this video of a moose shedding one antler (I love the family's comments as they are recording this).

Antlers are very important to male moose (and all deer) in obtaining mates (larger antlers help them in their dominance over other males), but they shed these antlers in the fall to save energy over the long winter.

A male moose also has a large "beard" hanging below its chin, made of hair and loose skin. This is called a dewlap (females have them, too, but they are smaller). Oddly, no one is sure exactly what the dewlap is for. Some biologists suggest that it helps the males spread their scent (in the form of urine) onto trees to mark their territory or onto females (isn't that romantic?).

Now, here's a weird fact about moose antlers. If a bull moose is castrated (um... maybe by an attacking wolf or by trying to jump over something?), his antlers will quickly fall off. Soon after, he will grow a new set of antlers, but these will be oddly shaped and deformed. And this new set of antlers never falls off. Yep, the moose wears them the rest of his life. This happens often enough that these strangely-shaped antlers have a name--"devil's antlers." Native Americans have several myths regarding such antlers. See the photo below.

One more bit about the moose in popular culture. For some reason (possibly the moose's goofy looks), moose are extremely popular in cartoons and children's books. Dr. Suess wrote a beloved book titled Thidwick the Big-Hearted Moose. And then there's If You Give a Moose a Muffin by Laura Numeroff, as well as many more. There's the craft beer called Moose Drool, from Big Sky Brewing in Montana. By the way, I used to brew my own beer, and once I used a recipe that was supposed to resemble Moose Drool, but instead it was called Caribou Slobber... but I digress.

There are countless moose products, from moose-shaped coffee mugs to moose toilet paper holders. But perhaps my favorite pop culture moose is Bullwinkle. Bullwinkle J. Moose is a character from an old cartoon TV show that played from 1959 to 1964. You know... back when they made the really good cartoons. Repeats of this awesome show have been playing for over 50 years. In 1996, Bullwinkle was rated by TV Guide as the #32 greatest TV star of all time. Although Bullwinkle was rather dim-witted, he was balanced out by his smarter partner, the flying squirrel named Rocky.

Hmmm....I wonder if I can find these shows on Netflix or DVD...

So, the moose deserves a place in the R.A.H.O.F.

(Righteous Animal Hall of Fame).

FUN FACT: The word righteous originated before the year 900, so it has been around for a while. It started as the Middle English word rightwos but eventually became righteous. Original meaning: someone characterized by uprightness and morality (hmm... that sounds like Bullwinkle to me). Eventually, though, a slang form came to mean absolutely genuine or wonderful, as in, "That ice cream was righteous!" Or, "Did you see Chuck Norris beat up those bad guys? That was righteous!" So, righteous is another way to say awesome!

Photo Credits:

Boundary Waters photo of cow moose with calf - Stan C. Smith

Bull moose #1 - National Park Service

Bull Moose with dewlap - Pinterest

Devil's Antlers - Mary Anning's Revenge

Rocky and Bullwinkle - Dreamworks Wiki

Published on September 01, 2018 06:09

August 20, 2018

Awesome Animal - Common Snapping Turtle

Last summer when I was on a week-long adventure the Boundary Waters Canoe Area with my brothers, nephew, and my son, I got out of the tent one morning to find an enormous female snapping turtle trying to lay eggs right in the middle of the campsite (see photo below).

She stayed in that spot for several hours, ignoring us as we took photos and stepped around her as we went about our business around camp.

And here's the best part: When the turtle was apparently finished with her attempt to dig her hole, she headed back toward the water. The problem is, this campsite is fifteen feet above the water surface, with a large slab of rock sloping down toward the water. The turtle went straight for a place where the rock gets really steep the last ten feet to the water. She reached a point at which the slope was too steep to walk, and she hesitated. She seemed to consider this conundrum for a few seconds. Then she lunged forward and literally tumbled end over end until splashing into the water. To fully appreciate this amazing behavior, you must realize that this turtle was huge, at least 30 pounds, which made for quite a splash.

So what the heck is a Common Snapping Turtle?

The common snapping turtle (Chelydra serpentina) is a large, heavy water turtle that lives throughout the eastern half of the United States and southern Canada. In fact, North America is the only place on Earth where members of this family can be found. Although there are four species in the family, the common snapping turtle is the most widespread (hence the name, common).

I intentionally included the word "common" in the name for this email to distinguish this turtle from the larger Alligator Snapping Turtle, which lives in the southeast U.S.

Snapping turtles are perhaps best known for being aggressive when provoked. They have extremely long necks (the species name is serpentina because their neck and head resembles a snake), and they can very quickly snap out and bite with their powerful, beak-like jaws.

In fact, a few years ago I found one crossing a gravel road. I approached it to get a better look. Thinking I might move it off the road, I reached for it. The turtle didn't like that. Its head shot out at least twelve inches, and it literally leaped six inches off the ground in an attempt to bite me. I nearly fell over backward in my attempt to pull my hand back.

But of course I should point out that these turtles are NOT aggressive unless they feel threatened. If you leave them alone, they will leave you alone.

Amazing facts about Common Snapping Turtles

They are big! Common snapping turtles regularly grow to over thirty pounds (13.6 kg), and the heaviest one caught in the wild was 75 pounds (34 kg). Its close cousin, the Alligator Snapping Turtle can grow to 300 pounds (136 kg)!

They can live for a long time. Their average lifespan in the wild is about 30 years. But a long-term mark and recapture study in Ontario, Canada, suggests that they can live over 100 years.

Snapping turtles are not picky eaters. In fact, these turtles will eat just about anything they can fit in their mouths. They eat insects, worms, leeches, crayfish, snails, frogs, other turtles, snakes, fish, small ducklings and goslings, and just about anything they find that is already dead. Last week, we had a stringer of fish tied to a branch at the lake shore so that we could cook them for dinner. We went out for a paddling outing on the lake. As we returned, nearing the shore, Trish, who was in the front of the canoe, suddenly slapped the water with her paddle and cried, "get away from our fish!" A huge snapping turtle had eaten almost all of one of the fish and was trying to start on a second. Trish scared it away with her paddle (I must admit, she startled me, too), but the turtle was back a few minutes later, not willing to give up, so we went ahead and cleaned the fish for an early dinner.

Snapping turtles lay lots of eggs. This is about the only time they come out of the water. The female finds a soft bit of ground and uses her hind feet to dig a hole. She will then lay 25 to 45 eggs, which look similar to ping pong balls but have a soft, leathery shell. The eggs hatch after incubating for 75 to 95 days.

Now, here's a weird fact about snapping turtle eggs. As is true for some other reptiles, the sex of the turtle hatchlings is determined by the temperature of incubation. At lower temperature (68º F, 20º C) all the young will be female. At higher temps (about 74º F, 23.3º C) they will all be male. And in between, half of them will be male and half female.

Hatchling snapping turtles have a low success rate. Only about an inch long, they have soft shells and are quickly eaten by birds. If they make it to the water, many are then eaten by fish or other snapping turtles (hey, that's cannibalism!).

Snapping turtles hibernate during the winter. When the temperature drops to below 41º F (5º C), they bury themselves in the mud at the bottom of shallow water and remain there until the spring.

That's a long time to hold your breath! Of course, during the winter their metabolism drops to nearly zero, so they don't use much oxygen. Here's part of their secret: while hibernating, snapping turtles take in a small about of water through their cloaca (um... that's their butthole), and they get their small amount of oxygen that way. Even under normal warm conditions, they can hold their breath for over ten minutes!

Check out this video comparing the Common Snapping Turtle to the Alligator Snapping Turtle

Below is a common snapping turtle, but I don't recommend holding them this way, as they can reach their head back surprising far to bite.

One more tidbit. Thanks to a 19th-century political cartoon, the common snapping turtle is also known as "Ograbme." The cartoon was drawn in 1808, and it was in protest to Thomas Jefferson's unpopular Embargo Act. In the cartoon, we see the president prompting a snapping turtle to bite the hind end of some poor merchant, who curses the ograbme (which is "embargo" spelled backward).

So, the snapping turtle deserves a place in the S.A.H.O.F.

(Supercalifragilisticexpialidocious Animal Hall of Fame).

FUN FACT: The word Supercalifragilisticexpialidocious originated in the Disney movie, Mary Poppins. It describes anything so indescribable that there is no other word to describe it. The song is forever etched into my memory: "It's Supercalafragilisticexpialidocious, even though the sound of it is something quite atrocious, if you say it loud enough you'll always sound precocious, Supercalifragilisticexpialidocious!" So, it's another way to say awesome!

Photo Credits:

Boundary Waters snapping turtle laying eggs - Stan C. Smith