Stan C. Smith's Blog, page 28

December 29, 2019

Awesome Animal - Reindeer

There are two reasons why I chose the reindeer for this post. The first one is obvious, right? It's close to Christmas.

The second reason? Because reindeer play a role in the upcoming first book in my new series. The series is titled Across Horizons , and it is my own twist on time travel (more information on the series in future newsletters). The first book takes place 47,000 years in the past, when reindeer roamed much of the northern hemisphere in vast herds. At the time, there were also cave lions, cave bears, woolly rhinos, and countless other impressive mammals... but again, more on that later.

What the heck is a Reindeer?

Everyone has heard of reindeer, but does everyone know much about the actual wild animal? First, you should know that in North America these creatures are called caribou . Yep, caribou and reindeer are the same species.

As the name suggests, they are a species of deer, with the scientific name of Rangifer tarandus. They are all the same species, but there are at least 13 different subspecies, usually separated into geographically distinct "herds."

Amazing facts about Reindeer

Reindeer have what's called a circumpolar distribution. This means they exist all the way around the world at far north latitudes (near the North Pole). So, they can be found in the cold, northern regions of North America, Greenland, Europe, and Siberia.

Reindeer have impressive antlers. In fact, relative to body size, they have the largest, heaviest antlers of all the living species of deer. A male's antlers can reach up to 51 inches (130 cm) long. Moose can have larger antlers, but they also have much larger bodies.

Keep in mind that antlers and horns are not the same thing. Antlers are made of bone, they usually are branched, and they grow and fall off every year. Antlers are features of the deer family (Cervidae). Horns have a bony core covered by a keratin sheath (keratin is the protein that makes up hair, skin, and fingernails). Horns, which are a permanent part of the body and do not fall off, are features of the Bovidae family (cattle, sheep, goats, bison, and others).

Reindeer are the only species of deer in which both males and females grow antlers. Here is an interesting thought. Male reindeer start growing their antlers in March or April and then shed them by early December (before Christmas). Female reindeer start growing their antlers in May or June, and they don't shed them until they start having calves in the spring. Hmm... In every movie or picture of Santa and his sleigh, the reindeer have antlers. This means all those reindeer are FEMALE. Oh no, my head is going to explode! I've always thought Rudolph, and at least some of the others, were boys.

Well, hold on a second... The timing of antler shedding in males can sometimes be affected by other factors. For example, young males can keep their antlers longer. Also, males that are neutered may not lose their antlers until April. Do we dare imagine that Santa may have neutered his reindeer?

Anyway, reindeer antlers can be quite impressive.

Although reindeer all belong to one species, the various subspecies can be quite different. In some subspecies, the males can grow to over 550 pounds (250 kg). The males of the smallest subspecies, the Svalbard reindeer, average only about 150 pounds (68 kg).

Hmmm... let's think about this. The very first time people were introduced to the idea of Santa having reindeer was in 1823. This was when Clement C. Moore published his poem, "A Visit from Saint Nicholas" (also known as "Twas the Night Before Christmas" from the poem's first line). In this poem, Moore described the reindeer as "tiny." That makes sense to me—we certainly don't need a 550-pound reindeer falling through the roof. So... logically, Santa's reindeer must be Svalbard reindeer. But this means that all the movies have it wrong, as they always use huge, full-sized reindeer. So confusing!

As I said, the first mention of Santa having reindeer was Moore's poem. Moore provided the names Dasher, Dancer, Prancer, Vixen, Comet, Cupid, Dunder and Blixem. Wait, what? Dunder and Blixem? Eventually, these last two were changed from Dutch to German, and they became Donner and Blitzen. But still, these two stand out. Why? Because all the others make sense in English. In German, Donner means "thunder" and Blitzen means "flash."

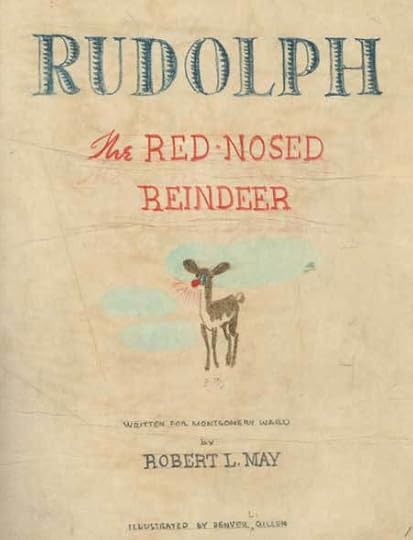

While I'm on a roll with Santa connections, what about Rudolph? Well, he (or she...?) wasn't introduced until 1939. That's when Robert L. May, a catalog writer for Montgomery Ward, wrote a children's book for the department store. The book was written in verse, and May titled it, “Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer.” Here's what the original looked like:

Hmm... no antlers on the original Rudolph. In fact, it didn't look much like a reindeer at all.

Okay, I have to address something I've wondered about all my life. Where did the idea come from that reindeer could fly? For my benefit and yours, I did a bit of research on this. As it turns out, this idea might be much older than you think. The anthropologist Piers Vitebsky, in his book "The Reindeer People," provides details of Reindeer Stones. These are stones that ancient people (as long ago as 3,000 years) embedded vertically in the ground. Reindeer stones are found in various places throughout the world but particularly in Siberia and Mongolia. Various animals were carved upon these stones. However, one animal was carved far more often than any other—the reindeer.

The odd thing about these carved reindeer is that they are depicted with their neck outstretched, their front legs flung out in front, and their back legs flung out behind. And often the sun is framed within the creature's antlers, as if the artists were depicting the reindeer flying through the sky.

Below is a set of "reindeer stones."

So, perhaps some ancient peoples thought of reindeer as having superpowers, including the ability to fly. The Pazyryk people were an ancient nomadic culture in the Altai mountains of Siberia. Their mummified remains are really cool because these people had a habit of covering their bodies with elaborate tattoos, and many of these tattoos are still clearly visible. Guess what was often depicted in their tattoos.... yep, flying reindeer.

Below is an actual mummified tattoo depicting a reindeer that seems to be flying. The image is shown more clearly on the right. Notice that this tattoo even shows the reindeer with a bird's beak.

So, it seems that the idea of flying reindeer is not a new concept at all. Now, back to real reindeer...

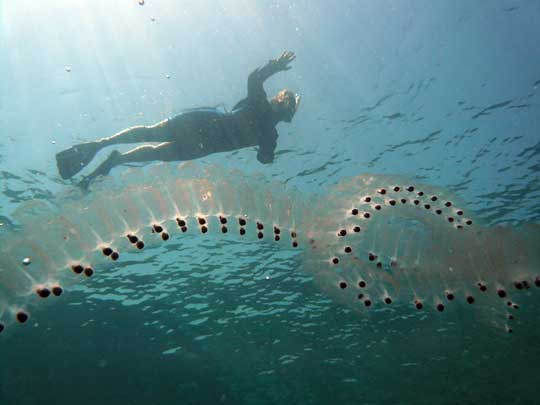

Some reindeer subspecies migrate, others don't. Those that do migrate, though, can be pretty impressive. A few populations of reindeer in North America migrate farther than any other land animal, up to 3,100 miles each year. To accomplish this, they average about 23 miles per day. Sometimes these migrating herds can include as many as 500,000 individuals!

Check out this video of the Western Caribou Arctic Herd in Alaska.

Rivers and lakes don't slow the reindeer down as they migrate. Adults can swim long distances at 4 mph (6.4 km/hr), and they can swim 6 mph (10 km/hr) when they are in a real hurry.

Check out this video of a swimming herd.

A migrating herd of thousands of reindeer must be an amazing sight to see.

One last random fact: An entire reindeer was once found inside the stomach of a Greenland shark. I just thought you might want to know that.

So, the Reindeer deserves a place in the P.A.H.O.F.

(Primo Animal Hall of Fame).

FUN FACT: The word primo originated in the mid 1700s. In Italian it literally means first. By the late 1700s it was primarily a musical term, meaning the first or leading part in an ensemble. Much more recently, the word has been adopted to describe something as excellent or first class ("That's a primo flying reindeer tattoo you got there."). In the1990s, it was often used as street slang to describe the high quality of drugs ("This is some primo weed, man!"). So, primo is another way to say awesome!

Photo Credits:

Reindeer herd #1 - Creative Commons via pxfuel.com

Reindeer with big antlers - National Park Service

Rudolph book - Rauner Special Collections Library/Dartmouth College via NPR

Reindeer stones - Alix Guillard, Wikimedia Commons, via Earthtouchnews

Reindeer tattoo - SiberianTimes via DailyMail

Large reindeer herd - ADF&G via National Park Service

The second reason? Because reindeer play a role in the upcoming first book in my new series. The series is titled Across Horizons , and it is my own twist on time travel (more information on the series in future newsletters). The first book takes place 47,000 years in the past, when reindeer roamed much of the northern hemisphere in vast herds. At the time, there were also cave lions, cave bears, woolly rhinos, and countless other impressive mammals... but again, more on that later.

What the heck is a Reindeer?

Everyone has heard of reindeer, but does everyone know much about the actual wild animal? First, you should know that in North America these creatures are called caribou . Yep, caribou and reindeer are the same species.

As the name suggests, they are a species of deer, with the scientific name of Rangifer tarandus. They are all the same species, but there are at least 13 different subspecies, usually separated into geographically distinct "herds."

Amazing facts about Reindeer

Reindeer have what's called a circumpolar distribution. This means they exist all the way around the world at far north latitudes (near the North Pole). So, they can be found in the cold, northern regions of North America, Greenland, Europe, and Siberia.

Reindeer have impressive antlers. In fact, relative to body size, they have the largest, heaviest antlers of all the living species of deer. A male's antlers can reach up to 51 inches (130 cm) long. Moose can have larger antlers, but they also have much larger bodies.

Keep in mind that antlers and horns are not the same thing. Antlers are made of bone, they usually are branched, and they grow and fall off every year. Antlers are features of the deer family (Cervidae). Horns have a bony core covered by a keratin sheath (keratin is the protein that makes up hair, skin, and fingernails). Horns, which are a permanent part of the body and do not fall off, are features of the Bovidae family (cattle, sheep, goats, bison, and others).

Reindeer are the only species of deer in which both males and females grow antlers. Here is an interesting thought. Male reindeer start growing their antlers in March or April and then shed them by early December (before Christmas). Female reindeer start growing their antlers in May or June, and they don't shed them until they start having calves in the spring. Hmm... In every movie or picture of Santa and his sleigh, the reindeer have antlers. This means all those reindeer are FEMALE. Oh no, my head is going to explode! I've always thought Rudolph, and at least some of the others, were boys.

Well, hold on a second... The timing of antler shedding in males can sometimes be affected by other factors. For example, young males can keep their antlers longer. Also, males that are neutered may not lose their antlers until April. Do we dare imagine that Santa may have neutered his reindeer?

Anyway, reindeer antlers can be quite impressive.

Although reindeer all belong to one species, the various subspecies can be quite different. In some subspecies, the males can grow to over 550 pounds (250 kg). The males of the smallest subspecies, the Svalbard reindeer, average only about 150 pounds (68 kg).

Hmmm... let's think about this. The very first time people were introduced to the idea of Santa having reindeer was in 1823. This was when Clement C. Moore published his poem, "A Visit from Saint Nicholas" (also known as "Twas the Night Before Christmas" from the poem's first line). In this poem, Moore described the reindeer as "tiny." That makes sense to me—we certainly don't need a 550-pound reindeer falling through the roof. So... logically, Santa's reindeer must be Svalbard reindeer. But this means that all the movies have it wrong, as they always use huge, full-sized reindeer. So confusing!

As I said, the first mention of Santa having reindeer was Moore's poem. Moore provided the names Dasher, Dancer, Prancer, Vixen, Comet, Cupid, Dunder and Blixem. Wait, what? Dunder and Blixem? Eventually, these last two were changed from Dutch to German, and they became Donner and Blitzen. But still, these two stand out. Why? Because all the others make sense in English. In German, Donner means "thunder" and Blitzen means "flash."

While I'm on a roll with Santa connections, what about Rudolph? Well, he (or she...?) wasn't introduced until 1939. That's when Robert L. May, a catalog writer for Montgomery Ward, wrote a children's book for the department store. The book was written in verse, and May titled it, “Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer.” Here's what the original looked like:

Hmm... no antlers on the original Rudolph. In fact, it didn't look much like a reindeer at all.

Okay, I have to address something I've wondered about all my life. Where did the idea come from that reindeer could fly? For my benefit and yours, I did a bit of research on this. As it turns out, this idea might be much older than you think. The anthropologist Piers Vitebsky, in his book "The Reindeer People," provides details of Reindeer Stones. These are stones that ancient people (as long ago as 3,000 years) embedded vertically in the ground. Reindeer stones are found in various places throughout the world but particularly in Siberia and Mongolia. Various animals were carved upon these stones. However, one animal was carved far more often than any other—the reindeer.

The odd thing about these carved reindeer is that they are depicted with their neck outstretched, their front legs flung out in front, and their back legs flung out behind. And often the sun is framed within the creature's antlers, as if the artists were depicting the reindeer flying through the sky.

Below is a set of "reindeer stones."

So, perhaps some ancient peoples thought of reindeer as having superpowers, including the ability to fly. The Pazyryk people were an ancient nomadic culture in the Altai mountains of Siberia. Their mummified remains are really cool because these people had a habit of covering their bodies with elaborate tattoos, and many of these tattoos are still clearly visible. Guess what was often depicted in their tattoos.... yep, flying reindeer.

Below is an actual mummified tattoo depicting a reindeer that seems to be flying. The image is shown more clearly on the right. Notice that this tattoo even shows the reindeer with a bird's beak.

So, it seems that the idea of flying reindeer is not a new concept at all. Now, back to real reindeer...

Some reindeer subspecies migrate, others don't. Those that do migrate, though, can be pretty impressive. A few populations of reindeer in North America migrate farther than any other land animal, up to 3,100 miles each year. To accomplish this, they average about 23 miles per day. Sometimes these migrating herds can include as many as 500,000 individuals!

Check out this video of the Western Caribou Arctic Herd in Alaska.

Rivers and lakes don't slow the reindeer down as they migrate. Adults can swim long distances at 4 mph (6.4 km/hr), and they can swim 6 mph (10 km/hr) when they are in a real hurry.

Check out this video of a swimming herd.

A migrating herd of thousands of reindeer must be an amazing sight to see.

One last random fact: An entire reindeer was once found inside the stomach of a Greenland shark. I just thought you might want to know that.

So, the Reindeer deserves a place in the P.A.H.O.F.

(Primo Animal Hall of Fame).

FUN FACT: The word primo originated in the mid 1700s. In Italian it literally means first. By the late 1700s it was primarily a musical term, meaning the first or leading part in an ensemble. Much more recently, the word has been adopted to describe something as excellent or first class ("That's a primo flying reindeer tattoo you got there."). In the1990s, it was often used as street slang to describe the high quality of drugs ("This is some primo weed, man!"). So, primo is another way to say awesome!

Photo Credits:

Reindeer herd #1 - Creative Commons via pxfuel.com

Reindeer with big antlers - National Park Service

Rudolph book - Rauner Special Collections Library/Dartmouth College via NPR

Reindeer stones - Alix Guillard, Wikimedia Commons, via Earthtouchnews

Reindeer tattoo - SiberianTimes via DailyMail

Large reindeer herd - ADF&G via National Park Service

Published on December 29, 2019 10:09

December 13, 2019

Awesome Animal - Chinese Giant Salamander

I can't help it. I have to feature another amphibian (in my last post I featured the Caecilian). After all,

Bridgers 6

is filled with awesome amphibians, so these critters are on my mind lately.

Bridgers 6 takes place on an alternate version of Earth teeming with creatures descended from amphibians. There are big ones, small ones, scary ones, and tall ones!

What's the biggest amphibian on our own version of Earth, you ask? Without a doubt, it's the Chinese giant salamander.

What the heck is a Chinese giant salamander?

Hiding in rocky streams in the Yangtze river basin of central China is an amazing salamander that grows to six feet (1.8 meters) long and weighs up to 110 pounds (50 kg). They are known to live at least sixty years, and possibly much longer. For a long time, scientists thought there was only one species, but genetic analysis indicates there are probably three or more distinct species.

Giant salamanders belong to the family Cryptobranchidae. There is actually one other member of this family, the hellbender (also known as the snot otter), which grows to two feet long and lives in the eastern United States (I featured the hellbender back in May).

Amazing facts about Chinese giant salamanders

Giant salamanders are considered living fossils because the Cryptobranchidae family has been around for 170 million years. Much of their history was during the time of dinosaurs! They have changed very little during all that time.

Giant salamanders spend their entire lives under water. Surprisingly, though, they do not have gills. Heck, they don't even have lungs. They get their oxygen by absorbing it directly through their skin. So, as you would expect, they need to live in streams with fast-moving, highly-oxygenated water. See all those folds of skin on the creature's sides? Those folds increase the surface area of the skin, which in turn increases the amount of oxygen absorbed.

Giant salamanders are predators, and they eat almost anything that moves and will fit in their mouth. They will suck up aquatic insects, worms, frogs, other salamanders, freshwater crabs, shrimp, and fish. They even eat smaller individuals of their own species, In fact, one study found that 28% of all the food found in the bellies of 79 giant salamanders was other giant salamanders.

Above I mentioned that they suck up their prey. This is called the gape-and-suck method, and it's actually a highly effective way to feed (many fish do this too). Here's how it works. When they sense prey in front of them, they greatly increase the size of their throat and pop open their mouth. This creates a powerful sucking action and draws in water, as well as any unfortunate creature swimming in the water. To make this even more effective, they displace their jaw in the process. This entire motion takes place in just a fraction of a second.

Check out this slow-motion video of how powerful this prey-sucking methods works!

I also mentioned above that giant salamanders "sense" the prey in front of them. They have very poor eyesight. Instead of seeing their prey, they have rows of special sensory nodes along each side of their body, from their head all the way to their tail. These sensory nodes allow them to detect the tiniest of vibrations in the water. So they "see" by detecting the vibrations other creatures create. This must work pretty well, because they catch enough prey to grow to over a hundred pounds!

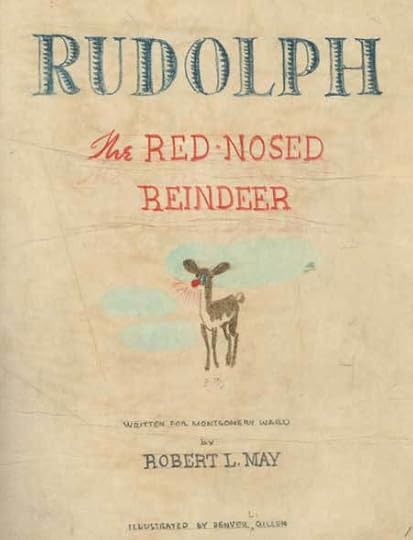

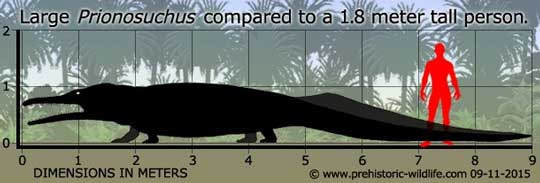

Sure, the Chinese giant salamander is a big amphibian, but is it the biggest amphibian ever? Not even close. About 275 million years ago, in the swamps and rivers of an area that is now Brazil, lived the Prionosuchus. Amazingly, Prionosuchus grew at least 30 feet long and weighed 4,400 pounds (2,000 kg).

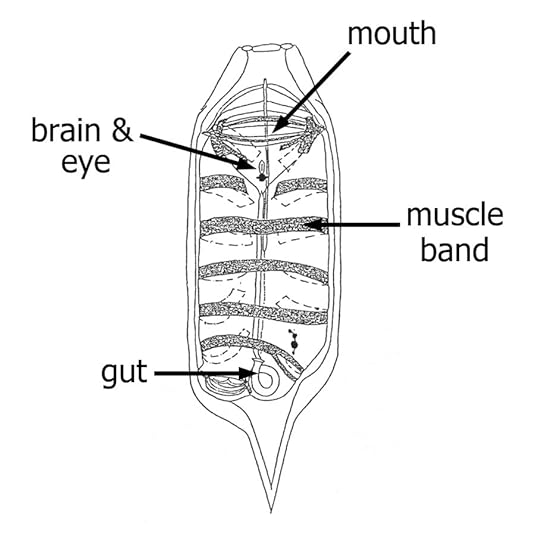

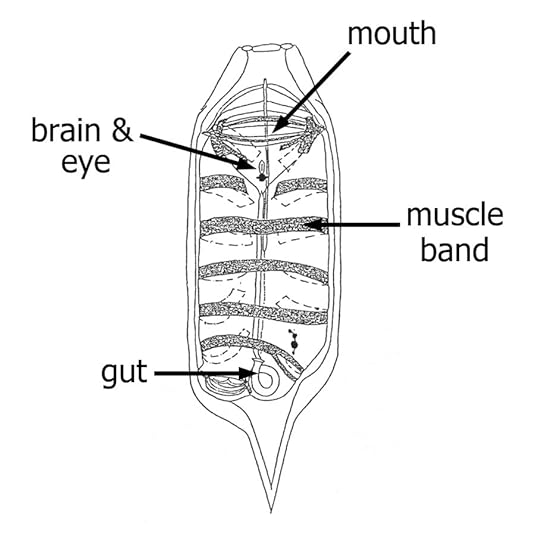

Prionosuchus was the amphibian version of a crocodile (does this sound familiar to those of you who have read Bridgers 6 ?), or more accurately, a gharial, a fish-eating crocodile with a long, narrow, toothy snout. The diagram below gives you an ideas of the size of the Prionosuchus. Keep in mind this creature was an amphibian!

There is an interesting story behind the first identification of giant salamanders. Surprisingly, scientists knew about giant salamanders from fossils before discovering living specimens. In 1726, Johann Scheuchze described a fossil giant salamander from Switzerland. He mistakingly believed the fossil was of a human that had drowned in the biblical flood, the Deluge. So he gave the fossil the name Homo diluvii testis. In Latin, this means Man, a witness of the Deluge.

The fossil (shown below) was about three feet (1 m) long, and the tail and hind legs were missing, so Scheuchze assumed it was a human child that had been violently trampled, perhaps in an attempt to escape the Deluge.

In 1758, another scientist decided the fossil was a catfish. Then in 1787, another scientist decided it was a lizard. In 1809, yet another scientist concluded that it was "nothing but a salamander, or rather a proteus of gigantic dimensions and of an unknown species."

Hmm... biology has come a long way in the last 250 years, hasn't it? Interestingly, in 1837, when the giant salamander was given its genus name (the name still used today), it was named Andrias. This means image of man. And scheuchzeri was assigned as the species name. These two names together honor Johann Scheuchze and his (mistaken) beliefs.

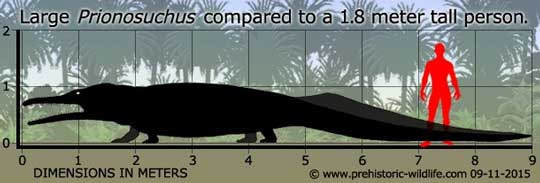

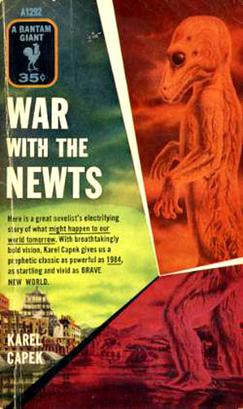

By the way (I can't help mentioning this), the species Andrias scheuchzeri was used by the Czech author Karel Čapek in his 1931 science fiction novel, War with the Newts (also translated as War with the Salamanders). In the Pacific, a race of intelligent salamanders are found. They are enslaved and abused. But then they rebel, which leads to a global war for species domination. This satirical book is considered by many to be the first ever dystopian sci-fi novel, and many consider it to be the best science fiction book ever written.

Chinese giant salamanders have inspired numerous myths and legends in Chinese culture. In fact, the commonly-seen yin and yang symbol is thought to have originally been two giant salamanders intertwined harmoniously. Also, these salamanders are often called wa wa yu, which means baby fish. Why? Because the giant salamander's distress call sounds like a human baby crying.

Check out this brief video about the Chinese giant salamander.

Okay, one more thing about the Chinese giant salamander. These creatures were once common in the rivers across southeast China. Unfortunately, now they are critically endangered in the wild. They have become a fashionable delicacy among the wealthy, and this has resulted in almost complete decimation in the wild from poaching.

Today most giant salamanders are found on commercial farms that raise them for food, sometimes bringing $1,500 per salamander. The Chinese government encourages the farms to release some of their salamanders into the wild. At first, this seems like a good idea. BUT... scientists have found that the farm-raised salamanders are genetically different from those in the wild. It seems the wild salamanders can easily be divided into five very different genetic groups, and the groups split apart from each other millions of years ago. But the farm salamanders are a result of extensive genetic mixing. So, the original genetically-distinct types in the wild are quickly being replaced by these new, artificially-mixed salamanders that never existed before. Hmm... an interesting dilemma.

So, the Chinese Giant Salamander deserves a place in the B.A.H.O.F.

(Boffo Animal Hall of Fame).

FUN FACT: The word boffo was first recorded in use in the 1940s. Basically it means sensational or extremely successful. By the 1960s, the word was commonly used in show business. This usage is thought to have originated in the Hollywood trade magazine Variety. Example: "It was a boffo performance, impressing even the harshest critics." So, basically, boffo means it's a hit. In spite of the giant salamander's recent troubles (being endangered), the fact that the creature has been around for 170 million years indicates a boffo performance (evolutionarily speaking). So, boffo is another way to say awesome!

Photo Credits:

Indian pipe - Stan C. Smith

Man holding giant salamander - Pinterest

Giant salamander in river - San Diego Zoo

Girl with salamander in zoo - Getty Images via DailyMail

Giant salamander fossil - Wikimedia

Bridgers 6 takes place on an alternate version of Earth teeming with creatures descended from amphibians. There are big ones, small ones, scary ones, and tall ones!

What's the biggest amphibian on our own version of Earth, you ask? Without a doubt, it's the Chinese giant salamander.

What the heck is a Chinese giant salamander?

Hiding in rocky streams in the Yangtze river basin of central China is an amazing salamander that grows to six feet (1.8 meters) long and weighs up to 110 pounds (50 kg). They are known to live at least sixty years, and possibly much longer. For a long time, scientists thought there was only one species, but genetic analysis indicates there are probably three or more distinct species.

Giant salamanders belong to the family Cryptobranchidae. There is actually one other member of this family, the hellbender (also known as the snot otter), which grows to two feet long and lives in the eastern United States (I featured the hellbender back in May).

Amazing facts about Chinese giant salamanders

Giant salamanders are considered living fossils because the Cryptobranchidae family has been around for 170 million years. Much of their history was during the time of dinosaurs! They have changed very little during all that time.

Giant salamanders spend their entire lives under water. Surprisingly, though, they do not have gills. Heck, they don't even have lungs. They get their oxygen by absorbing it directly through their skin. So, as you would expect, they need to live in streams with fast-moving, highly-oxygenated water. See all those folds of skin on the creature's sides? Those folds increase the surface area of the skin, which in turn increases the amount of oxygen absorbed.

Giant salamanders are predators, and they eat almost anything that moves and will fit in their mouth. They will suck up aquatic insects, worms, frogs, other salamanders, freshwater crabs, shrimp, and fish. They even eat smaller individuals of their own species, In fact, one study found that 28% of all the food found in the bellies of 79 giant salamanders was other giant salamanders.

Above I mentioned that they suck up their prey. This is called the gape-and-suck method, and it's actually a highly effective way to feed (many fish do this too). Here's how it works. When they sense prey in front of them, they greatly increase the size of their throat and pop open their mouth. This creates a powerful sucking action and draws in water, as well as any unfortunate creature swimming in the water. To make this even more effective, they displace their jaw in the process. This entire motion takes place in just a fraction of a second.

Check out this slow-motion video of how powerful this prey-sucking methods works!

I also mentioned above that giant salamanders "sense" the prey in front of them. They have very poor eyesight. Instead of seeing their prey, they have rows of special sensory nodes along each side of their body, from their head all the way to their tail. These sensory nodes allow them to detect the tiniest of vibrations in the water. So they "see" by detecting the vibrations other creatures create. This must work pretty well, because they catch enough prey to grow to over a hundred pounds!

Sure, the Chinese giant salamander is a big amphibian, but is it the biggest amphibian ever? Not even close. About 275 million years ago, in the swamps and rivers of an area that is now Brazil, lived the Prionosuchus. Amazingly, Prionosuchus grew at least 30 feet long and weighed 4,400 pounds (2,000 kg).

Prionosuchus was the amphibian version of a crocodile (does this sound familiar to those of you who have read Bridgers 6 ?), or more accurately, a gharial, a fish-eating crocodile with a long, narrow, toothy snout. The diagram below gives you an ideas of the size of the Prionosuchus. Keep in mind this creature was an amphibian!

There is an interesting story behind the first identification of giant salamanders. Surprisingly, scientists knew about giant salamanders from fossils before discovering living specimens. In 1726, Johann Scheuchze described a fossil giant salamander from Switzerland. He mistakingly believed the fossil was of a human that had drowned in the biblical flood, the Deluge. So he gave the fossil the name Homo diluvii testis. In Latin, this means Man, a witness of the Deluge.

The fossil (shown below) was about three feet (1 m) long, and the tail and hind legs were missing, so Scheuchze assumed it was a human child that had been violently trampled, perhaps in an attempt to escape the Deluge.

In 1758, another scientist decided the fossil was a catfish. Then in 1787, another scientist decided it was a lizard. In 1809, yet another scientist concluded that it was "nothing but a salamander, or rather a proteus of gigantic dimensions and of an unknown species."

Hmm... biology has come a long way in the last 250 years, hasn't it? Interestingly, in 1837, when the giant salamander was given its genus name (the name still used today), it was named Andrias. This means image of man. And scheuchzeri was assigned as the species name. These two names together honor Johann Scheuchze and his (mistaken) beliefs.

By the way (I can't help mentioning this), the species Andrias scheuchzeri was used by the Czech author Karel Čapek in his 1931 science fiction novel, War with the Newts (also translated as War with the Salamanders). In the Pacific, a race of intelligent salamanders are found. They are enslaved and abused. But then they rebel, which leads to a global war for species domination. This satirical book is considered by many to be the first ever dystopian sci-fi novel, and many consider it to be the best science fiction book ever written.

Chinese giant salamanders have inspired numerous myths and legends in Chinese culture. In fact, the commonly-seen yin and yang symbol is thought to have originally been two giant salamanders intertwined harmoniously. Also, these salamanders are often called wa wa yu, which means baby fish. Why? Because the giant salamander's distress call sounds like a human baby crying.

Check out this brief video about the Chinese giant salamander.

Okay, one more thing about the Chinese giant salamander. These creatures were once common in the rivers across southeast China. Unfortunately, now they are critically endangered in the wild. They have become a fashionable delicacy among the wealthy, and this has resulted in almost complete decimation in the wild from poaching.

Today most giant salamanders are found on commercial farms that raise them for food, sometimes bringing $1,500 per salamander. The Chinese government encourages the farms to release some of their salamanders into the wild. At first, this seems like a good idea. BUT... scientists have found that the farm-raised salamanders are genetically different from those in the wild. It seems the wild salamanders can easily be divided into five very different genetic groups, and the groups split apart from each other millions of years ago. But the farm salamanders are a result of extensive genetic mixing. So, the original genetically-distinct types in the wild are quickly being replaced by these new, artificially-mixed salamanders that never existed before. Hmm... an interesting dilemma.

So, the Chinese Giant Salamander deserves a place in the B.A.H.O.F.

(Boffo Animal Hall of Fame).

FUN FACT: The word boffo was first recorded in use in the 1940s. Basically it means sensational or extremely successful. By the 1960s, the word was commonly used in show business. This usage is thought to have originated in the Hollywood trade magazine Variety. Example: "It was a boffo performance, impressing even the harshest critics." So, basically, boffo means it's a hit. In spite of the giant salamander's recent troubles (being endangered), the fact that the creature has been around for 170 million years indicates a boffo performance (evolutionarily speaking). So, boffo is another way to say awesome!

Photo Credits:

Indian pipe - Stan C. Smith

Man holding giant salamander - Pinterest

Giant salamander in river - San Diego Zoo

Girl with salamander in zoo - Getty Images via DailyMail

Giant salamander fossil - Wikimedia

Published on December 13, 2019 07:21

December 3, 2019

Awesome Animal - Caecilian

Recently, I spotted this frog clinging to the corner of one of our little bird houses.

In spite of its mostly green color, this is a gray treefrog. These frogs can change their color, and they are actually gray more often than they are green. But when they are surrounded by green vegetation, their skin turns green like the one in this photo. You know, like a chameleon.

Let's think about this for a moment... their skin changes color to better conceal them. Wow. Perhaps amphibians are under-appreciated for their awesomeness. Consider the Olm, a blind salamander with transparent skin that lives underground, hunts for its prey by smell and electrosensitivity, and can survive without food for 10 years (seriously). Then there's the Chinese giant salamander that can grow up to 1.8 meters in length and evolved independently from all other amphibians over one hundred million years before Tyrannosaurus rex. And there's the Chile Darwin’s frog—the fathers protect the young in their mouths. And the Gardiner’s Seychelles frog, the world’s smallest frog, with adults growing up to be the size of a pencil eraser. And let's not forget about the caecilian, a legless amphibian that... oh, wait... the caecilian is today's Awesome Animal. Let's take a more careful look.

Have you ever heard of a glass lizard? It looks like a snake, but it's actually a lizard without legs. Well, the caecilian is kind of the glass lizard of the amphibian world—an amphibian with no legs. Actually, at first glance a caecilian looks like an earthworm. Check it out:

What the heck is a Caecilian?

First, Caecilian is pronounced seh-SILL-yun (almost like the pizza). Second, caecilians are amphibians, but they aren't frogs, they aren't toads, and they aren't salamanders. So what are they? They're caecilians, of course! Caecilians are their own order within the class Amphibia. In case you care, the order is called Gymnophiona (some scientists prefer to call the order Apoda, which means 'without feet').

Caecilians live on just about every continent that has moist tropical regions, including Southeast Asia, India, East and West Africa, Indonesia, and Central and South America.

Caecilians are the least known of the amphibians. One reason for this is that most of them spend their time underground (that's why they look like earthworms). Some of them are so secretive that it's almost certain that there are species we have not yet discovered. We now know of about 200 species. In fact, to celebrate the discovery of the 200th species, the musical group called the Wiggly Tendrils (this is a real band!) recorded a song titled Caecilian Cotillion.

Check out the Caecilian song!

Amazing facts about Caecilians

Where to even begin! Get ready to be amazed, because Caecilians are bizarre creatures.

Not all caecilians look like gray earthworms. They are kind of like gummy worms—they come in all colors and sizes. Check out this blue species:

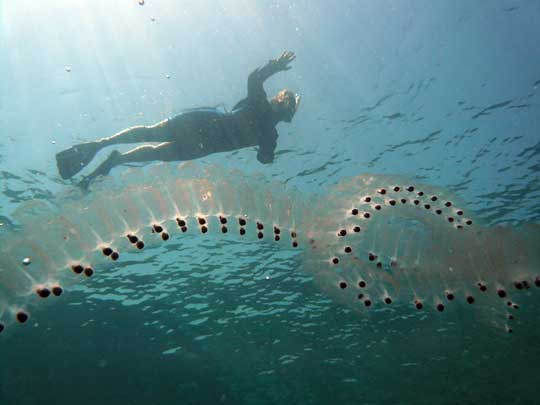

And not all of them live in the soil. Some of them are perfectly at home in the water. Check out this aquatic caecilian:

The smallest species of caecilians are only a few inches long, but the largest (Caecilia thompsoni from Colombia) can grow to five feet (1.5 m) long and weigh 2.2 pounds (1 kg). Five feet long!? What would a five-foot caecilian look like? You would think it would be fat and heavy-looking, but not so much:

When it comes to reproduction, frogs and toads have what's called external fertilization. That means the female lays eggs, and then the male fertilizes the eggs outside of the female's body. But caecilians have internal insemination. The males have a long, tube-like organ called a phallodeum, which is inserted into the female's cloaca for about three hours (I guess they aren't in any hurry). As you can probably guess, sperm cells are transmitted into the female's body through the phallodeum, where they fertilize the eggs.

Some caecilians lay eggs, some have live birth, but I feel compelled to nominate female caecilians for Mother of the Year. I'll explain why. In some caecilian species, the mother seals herself in a subterranean cavity, where she lays her eggs. The eggs hatch, and the mother and babies remain in the cavity for four to six weeks as the babies grow. What do the babies eat, you ask? Here's where it gets weird. After the female lays eggs, her skin begins to thicken, and the skin cells fill up with fats and other nutrients. The newly-hatched babies have special teeth that are like scrapers, and they literally eat the skin off the mother. The mother grows more skin, and the babies eat that skin, too. This continues until the babies are ready to leave home and go out on their own.

So the mothers literally feed the babies their own skin, over and over. Even more bizarre, in some of the species that have live birth, the babies inside the mother's body use their special teeth to munch on their mom's reproductive organs!

Like I said, Mother of the Year.

Caecilians have teeny tiny little eyes that don't see much, or don't see at all. These eyes are usually subcutaneous (buried under the skin), and some species even have bone over their eyes! There's not much need for eyes when most of your life is spent in the dark.

Not much is known about what Caecilians eat in the wild, but in captivity they readily chomp on earthworms, so worms are probably a normal part of their diet. In a study of the gut contents of 14 dead caecilians, the only identifiable objects were termite heads. That doesn't mean caecilians go around biting off the heads of termites, it just means that the heads are the portion that is most difficult to digest.

Although caecilians look like they are all tail, they actually don't even have tails. Their cloaca (that's the polite word for their butthole) is at the very end of their body.

Most caecilians breathe with lungs, but scientists were amazed to find some species without any lungs at all. Wow... eyes, legs, tails, and now lungs—caecilians seem to be all about giving things up. Apparently these lungless species can get all the oxygen they need by absorbing it directly through their skin. Here's a lungless caecilian found in Brazil:

Caecilians have super-strength. They need to be strong to push their way through the soil. Scientists at the University of Chicago wanted to find out how hard caecilians could push against soil. They set up an artificial tunnel and filled one end with dirt and put a brick at that end to stop the caecilians from burrowing any farther. To measure how hard the caecilian could push, they attached a device called a force plate. The results were a surprise. They used a caecilian only 1.5 feet (50 cm) long. “It just shoved this brick off the table,” one of the scientists recalled.

Because of this amazing soil-pushing strength, caecilians have developed extra-thick, reinforced skulls to prevent serious head damage.

So, the Caecilian deserves a place in the F.S.A.H.O.F.

(Four-Star Animal Hall of Fame).

FUN FACT: The phrase four-star was first recorded in use in the early 1920s. Basically it means of a superior degree of excellence. The phrase started as the number of asterisks used to denote relative excellence in guidebooks (for example, a four-star restaurant, or a four-star hotel). It also indicates being a full general or admiral, as indicated by four stars on an insignia. As with many other such words, four-star eventually was used to describe just about anything of high quality (the caecilian is a four-star amphibian). So, four-star is another way to say awesome!

Photo Credits:

Caecilian #1 - Michael & Patricia Fogden/CORBIS via WIRED

Blue Caecilian - Unknown, via beetleboybioblog

Aquatic caecilian - National Zoo

Longest caecilian - Reptilis.org

Blue and black caecilian with babies - Alex Kupfer via Science News for Students

Lungless caecilian - B.S.F. Silva via Science News for Students

In spite of its mostly green color, this is a gray treefrog. These frogs can change their color, and they are actually gray more often than they are green. But when they are surrounded by green vegetation, their skin turns green like the one in this photo. You know, like a chameleon.

Let's think about this for a moment... their skin changes color to better conceal them. Wow. Perhaps amphibians are under-appreciated for their awesomeness. Consider the Olm, a blind salamander with transparent skin that lives underground, hunts for its prey by smell and electrosensitivity, and can survive without food for 10 years (seriously). Then there's the Chinese giant salamander that can grow up to 1.8 meters in length and evolved independently from all other amphibians over one hundred million years before Tyrannosaurus rex. And there's the Chile Darwin’s frog—the fathers protect the young in their mouths. And the Gardiner’s Seychelles frog, the world’s smallest frog, with adults growing up to be the size of a pencil eraser. And let's not forget about the caecilian, a legless amphibian that... oh, wait... the caecilian is today's Awesome Animal. Let's take a more careful look.

Have you ever heard of a glass lizard? It looks like a snake, but it's actually a lizard without legs. Well, the caecilian is kind of the glass lizard of the amphibian world—an amphibian with no legs. Actually, at first glance a caecilian looks like an earthworm. Check it out:

What the heck is a Caecilian?

First, Caecilian is pronounced seh-SILL-yun (almost like the pizza). Second, caecilians are amphibians, but they aren't frogs, they aren't toads, and they aren't salamanders. So what are they? They're caecilians, of course! Caecilians are their own order within the class Amphibia. In case you care, the order is called Gymnophiona (some scientists prefer to call the order Apoda, which means 'without feet').

Caecilians live on just about every continent that has moist tropical regions, including Southeast Asia, India, East and West Africa, Indonesia, and Central and South America.

Caecilians are the least known of the amphibians. One reason for this is that most of them spend their time underground (that's why they look like earthworms). Some of them are so secretive that it's almost certain that there are species we have not yet discovered. We now know of about 200 species. In fact, to celebrate the discovery of the 200th species, the musical group called the Wiggly Tendrils (this is a real band!) recorded a song titled Caecilian Cotillion.

Check out the Caecilian song!

Amazing facts about Caecilians

Where to even begin! Get ready to be amazed, because Caecilians are bizarre creatures.

Not all caecilians look like gray earthworms. They are kind of like gummy worms—they come in all colors and sizes. Check out this blue species:

And not all of them live in the soil. Some of them are perfectly at home in the water. Check out this aquatic caecilian:

The smallest species of caecilians are only a few inches long, but the largest (Caecilia thompsoni from Colombia) can grow to five feet (1.5 m) long and weigh 2.2 pounds (1 kg). Five feet long!? What would a five-foot caecilian look like? You would think it would be fat and heavy-looking, but not so much:

When it comes to reproduction, frogs and toads have what's called external fertilization. That means the female lays eggs, and then the male fertilizes the eggs outside of the female's body. But caecilians have internal insemination. The males have a long, tube-like organ called a phallodeum, which is inserted into the female's cloaca for about three hours (I guess they aren't in any hurry). As you can probably guess, sperm cells are transmitted into the female's body through the phallodeum, where they fertilize the eggs.

Some caecilians lay eggs, some have live birth, but I feel compelled to nominate female caecilians for Mother of the Year. I'll explain why. In some caecilian species, the mother seals herself in a subterranean cavity, where she lays her eggs. The eggs hatch, and the mother and babies remain in the cavity for four to six weeks as the babies grow. What do the babies eat, you ask? Here's where it gets weird. After the female lays eggs, her skin begins to thicken, and the skin cells fill up with fats and other nutrients. The newly-hatched babies have special teeth that are like scrapers, and they literally eat the skin off the mother. The mother grows more skin, and the babies eat that skin, too. This continues until the babies are ready to leave home and go out on their own.

So the mothers literally feed the babies their own skin, over and over. Even more bizarre, in some of the species that have live birth, the babies inside the mother's body use their special teeth to munch on their mom's reproductive organs!

Like I said, Mother of the Year.

Caecilians have teeny tiny little eyes that don't see much, or don't see at all. These eyes are usually subcutaneous (buried under the skin), and some species even have bone over their eyes! There's not much need for eyes when most of your life is spent in the dark.

Not much is known about what Caecilians eat in the wild, but in captivity they readily chomp on earthworms, so worms are probably a normal part of their diet. In a study of the gut contents of 14 dead caecilians, the only identifiable objects were termite heads. That doesn't mean caecilians go around biting off the heads of termites, it just means that the heads are the portion that is most difficult to digest.

Although caecilians look like they are all tail, they actually don't even have tails. Their cloaca (that's the polite word for their butthole) is at the very end of their body.

Most caecilians breathe with lungs, but scientists were amazed to find some species without any lungs at all. Wow... eyes, legs, tails, and now lungs—caecilians seem to be all about giving things up. Apparently these lungless species can get all the oxygen they need by absorbing it directly through their skin. Here's a lungless caecilian found in Brazil:

Caecilians have super-strength. They need to be strong to push their way through the soil. Scientists at the University of Chicago wanted to find out how hard caecilians could push against soil. They set up an artificial tunnel and filled one end with dirt and put a brick at that end to stop the caecilians from burrowing any farther. To measure how hard the caecilian could push, they attached a device called a force plate. The results were a surprise. They used a caecilian only 1.5 feet (50 cm) long. “It just shoved this brick off the table,” one of the scientists recalled.

Because of this amazing soil-pushing strength, caecilians have developed extra-thick, reinforced skulls to prevent serious head damage.

So, the Caecilian deserves a place in the F.S.A.H.O.F.

(Four-Star Animal Hall of Fame).

FUN FACT: The phrase four-star was first recorded in use in the early 1920s. Basically it means of a superior degree of excellence. The phrase started as the number of asterisks used to denote relative excellence in guidebooks (for example, a four-star restaurant, or a four-star hotel). It also indicates being a full general or admiral, as indicated by four stars on an insignia. As with many other such words, four-star eventually was used to describe just about anything of high quality (the caecilian is a four-star amphibian). So, four-star is another way to say awesome!

Photo Credits:

Caecilian #1 - Michael & Patricia Fogden/CORBIS via WIRED

Blue Caecilian - Unknown, via beetleboybioblog

Aquatic caecilian - National Zoo

Longest caecilian - Reptilis.org

Blue and black caecilian with babies - Alex Kupfer via Science News for Students

Lungless caecilian - B.S.F. Silva via Science News for Students

Published on December 03, 2019 05:43

November 12, 2019

Awesome Animal - Howler Monkey

We all remember our first time, right? I'm talking about the first time I ever saw a monkey in the wild... geez, what'd you think I was referring to?

It was 2010. Trish and I saved up our hard-earned pennies, and we traveled to Belize. At a place called Lamanai, where there are some fascinating Mayan ruins, a black howler monkey came down in a tree within a few meters of us, allowing me to get a decent photo:

That was on the first day, and then later that evening, we had our first opportunity to listen to the behavior that gave these monkeys their name. When howler monkeys feel threatened, and especially when one troop comes upon a second troop, they howl. I mean they really howl. Not only is it amazingly loud, it also sounds kind of haunting and ominous. I didn't get a recording of the black howlers in Belize, but a few years later Trish and I were canoeing in Costa Rica when two troops of mantled howler monkeys got into a dispute, howling at each other across the river from both sides of us.

Here's a video I recorded of that dispute .

Be sure to turn your speakers up to fully appreciate their howling.

Amazingly, these calls can be heard up to three miles away!

What the heck is a Howler Monkey?

Howler monkeys are some of the largest monkeys that live in Central and South America. Howlers, of course, are monkeys, which means they are in the order Primates. There are fifteen species of howler monkeys, all of them in the family Atelidae.

Howlers are the only New World monkeys that are folivores. This means they eat leaves. They also eat flowers, nuts, and fruits, but they mostly love eating the leaves at the top of the canopy. Needless to say, they must be fantastic climbers in order to do this.

Amazing facts about Howler Monkeys

I'm going to focus mainly on one thing—the howler's reputation for being extremely loud. Why do they have this reputation? Because they are extremely loud! They are actually in the Guinness Book Of World Records as the loudest land animal.

This cacophonous call is possible because male howlers have extra-large throats. Also, they have a really cool hyoid bone. Usually, the hyoid is a horseshoe-shaped bone that helps with swallowing and tongue movement. But in howler monkeys, the bone has become a large resonating chamber in the throat. See the image below.

You could certainly hear the mantled howlers in my video above, but the monkeys themselves weren't very visible. You really need to see one of these monkeys up close as it is calling, so...

Check out this video of a Red Howler Monkey!

Now, the next question is, why do howler monkeys call so loudly? Howler monkeys are highly territorial. They live in troops of six to fifteen monkeys, and they howl to broadcast their position to other troops, warning them to keep their distance. When one troop actually comes within sight of another, the resulting shouting match can be impressive.

Wait! There's more to the story.

Yes, howling is a way to defend their territory, but that's not all. This howling behavior is also very important for communication within a howler monkey troop. In fact, this is a primary way for the males to attract mates.

In many animals, the males have certain physical features for impressing the females: a peacock's (and a turkey's) tail feathers, a deer's antlers, a drake mallard's bright green head, and many others. But in howler monkeys, volume is king. Louder males tend to get the females. So, it's not surprising that males have huge hyoids and females don't.

Warning: If you are reading this to your young kids, you are now entering the territory of mating habits, sperm cells, and testicles.

Now, let's explore this even further. Recent studies have shown that howler monkeys with larger hyoids (louder calls) have smaller testicles. Monkeys with smaller hyoids (quieter call) have larger testicles.

Hmm... interesting. I should explain.

Important Fact #1:

We all know what testicles are for, right? Just in case you aren't sure, testicles produce sperm cells. Sperm cells are necessary for a male to impregnate a female, thus producing offspring. The larger the testicles, the more sperm cells the male can produce. For a male howler, producing more sperm cells is a good thing.

Important Fact #2:

For a male howler, it's also a good thing to have a larger hyoid. Why? Because a larger hyoid results in a louder, lower voice. Guess what kind of voice is most appealing to the females... yep, a louder, lower voice.

Important Fact #3:

Both of these features are expensive. By expensive, I mean they take a lot of energy to produce. So, it's a tradeoff—male howlers can have large hyoids, or they can have large testicles, but they can't have both. Bummer.

The Amazing Result:

Some species of howlers live in groups in which there is only one male and many females. In these species, the males try to attract as many females as possible (otherwise they'll end up living alone). How do they attract all these females? By having a loud, deep call (a large hyoid but small testicles).

Other species live in groups in which there are numerous males instead of just one. In these species, it is helpful for the male to produce lots of sperm (large testicles but small hyoid). Why does it help for them to make lots of sperm? Because in these species the competition for mates comes aftercopulation. A greater volume of sperm gives these males a better chance of impregnating a female. Each female mates with all the males, and so all those sperm cells are racing to fertilize the egg. The more runners a male has in the race, the better chance he has of winning. Make sense?

Below is a male howler monkey. As you can probably guess, this is a species with a relatively small hyoid bone.

So, the Howler Monkey deserves a place in the S.A.H.O.F.

(Sick Animal Hall of Fame).

FUN FACT: The word sick originated before the year 900. It has always had the meaning, afflicted with ill health or disease. However, in the 1980s, the word became popular with surfers and skateboarders as a way to express "shock and awe" after seeing something amazing ("that stunt was sick"). Now it is used to praise just about anything (that episode of The Simpsons was sick!). So, sick is another way to say awesome!

Photo Credits:

Black Howler in Belize - Stan C. Smith

Howler skeleton with Hyoid - Evolutionary Literacy

Three Howlers howling - Mariana Raño via Scientific American

Black howler monkey with testicles - Scott Robinson vis Slate

It was 2010. Trish and I saved up our hard-earned pennies, and we traveled to Belize. At a place called Lamanai, where there are some fascinating Mayan ruins, a black howler monkey came down in a tree within a few meters of us, allowing me to get a decent photo:

That was on the first day, and then later that evening, we had our first opportunity to listen to the behavior that gave these monkeys their name. When howler monkeys feel threatened, and especially when one troop comes upon a second troop, they howl. I mean they really howl. Not only is it amazingly loud, it also sounds kind of haunting and ominous. I didn't get a recording of the black howlers in Belize, but a few years later Trish and I were canoeing in Costa Rica when two troops of mantled howler monkeys got into a dispute, howling at each other across the river from both sides of us.

Here's a video I recorded of that dispute .

Be sure to turn your speakers up to fully appreciate their howling.

Amazingly, these calls can be heard up to three miles away!

What the heck is a Howler Monkey?

Howler monkeys are some of the largest monkeys that live in Central and South America. Howlers, of course, are monkeys, which means they are in the order Primates. There are fifteen species of howler monkeys, all of them in the family Atelidae.

Howlers are the only New World monkeys that are folivores. This means they eat leaves. They also eat flowers, nuts, and fruits, but they mostly love eating the leaves at the top of the canopy. Needless to say, they must be fantastic climbers in order to do this.

Amazing facts about Howler Monkeys

I'm going to focus mainly on one thing—the howler's reputation for being extremely loud. Why do they have this reputation? Because they are extremely loud! They are actually in the Guinness Book Of World Records as the loudest land animal.

This cacophonous call is possible because male howlers have extra-large throats. Also, they have a really cool hyoid bone. Usually, the hyoid is a horseshoe-shaped bone that helps with swallowing and tongue movement. But in howler monkeys, the bone has become a large resonating chamber in the throat. See the image below.

You could certainly hear the mantled howlers in my video above, but the monkeys themselves weren't very visible. You really need to see one of these monkeys up close as it is calling, so...

Check out this video of a Red Howler Monkey!

Now, the next question is, why do howler monkeys call so loudly? Howler monkeys are highly territorial. They live in troops of six to fifteen monkeys, and they howl to broadcast their position to other troops, warning them to keep their distance. When one troop actually comes within sight of another, the resulting shouting match can be impressive.

Wait! There's more to the story.

Yes, howling is a way to defend their territory, but that's not all. This howling behavior is also very important for communication within a howler monkey troop. In fact, this is a primary way for the males to attract mates.

In many animals, the males have certain physical features for impressing the females: a peacock's (and a turkey's) tail feathers, a deer's antlers, a drake mallard's bright green head, and many others. But in howler monkeys, volume is king. Louder males tend to get the females. So, it's not surprising that males have huge hyoids and females don't.

Warning: If you are reading this to your young kids, you are now entering the territory of mating habits, sperm cells, and testicles.

Now, let's explore this even further. Recent studies have shown that howler monkeys with larger hyoids (louder calls) have smaller testicles. Monkeys with smaller hyoids (quieter call) have larger testicles.

Hmm... interesting. I should explain.

Important Fact #1:

We all know what testicles are for, right? Just in case you aren't sure, testicles produce sperm cells. Sperm cells are necessary for a male to impregnate a female, thus producing offspring. The larger the testicles, the more sperm cells the male can produce. For a male howler, producing more sperm cells is a good thing.

Important Fact #2:

For a male howler, it's also a good thing to have a larger hyoid. Why? Because a larger hyoid results in a louder, lower voice. Guess what kind of voice is most appealing to the females... yep, a louder, lower voice.

Important Fact #3:

Both of these features are expensive. By expensive, I mean they take a lot of energy to produce. So, it's a tradeoff—male howlers can have large hyoids, or they can have large testicles, but they can't have both. Bummer.

The Amazing Result:

Some species of howlers live in groups in which there is only one male and many females. In these species, the males try to attract as many females as possible (otherwise they'll end up living alone). How do they attract all these females? By having a loud, deep call (a large hyoid but small testicles).

Other species live in groups in which there are numerous males instead of just one. In these species, it is helpful for the male to produce lots of sperm (large testicles but small hyoid). Why does it help for them to make lots of sperm? Because in these species the competition for mates comes aftercopulation. A greater volume of sperm gives these males a better chance of impregnating a female. Each female mates with all the males, and so all those sperm cells are racing to fertilize the egg. The more runners a male has in the race, the better chance he has of winning. Make sense?

Below is a male howler monkey. As you can probably guess, this is a species with a relatively small hyoid bone.

So, the Howler Monkey deserves a place in the S.A.H.O.F.

(Sick Animal Hall of Fame).

FUN FACT: The word sick originated before the year 900. It has always had the meaning, afflicted with ill health or disease. However, in the 1980s, the word became popular with surfers and skateboarders as a way to express "shock and awe" after seeing something amazing ("that stunt was sick"). Now it is used to praise just about anything (that episode of The Simpsons was sick!). So, sick is another way to say awesome!

Photo Credits:

Black Howler in Belize - Stan C. Smith

Howler skeleton with Hyoid - Evolutionary Literacy

Three Howlers howling - Mariana Raño via Scientific American

Black howler monkey with testicles - Scott Robinson vis Slate

Published on November 12, 2019 04:45

October 29, 2019

Awesome Animal - Tasmanian Tiger

You know, there are some animals that humans really wish still existed. One example is the ivory-billed woodpecker in North America. The last universally-accepted sighting of an ivory-billed woodpecker was in Louisiana in 1944. But diehard birders never stop searching, hoping to be the first to discover that this species still exists. And there are numerous unconfirmed sightings. So I guess the ivory-billed woodpecker is kind of like Elvis.

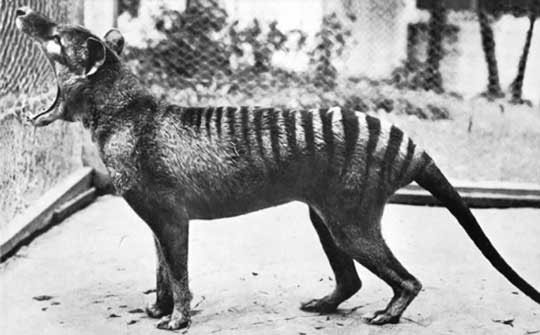

In Australia, and particularly in the Australian island state of Tasmania, people are still looking for the Tasmanian tiger, also known as the Thylocine. Yep, they're still looking, even though the last of these creatures died in 1936.

The Tasmanian tiger is, no doubt, an awesome animal, so let's take a closer look. We'll also take a closer look at the never-ending search for this creature.

What the heck is a Tasmanian Tiger (Thylacine)?

First, the thylacine is a marsupial. You know what marsupials are, right? They are a group of mammals that give birth to very small young, which are then nurtured in an external pouch (includes kangaroos, koalas, opossums, wombats, and many more). Placental mammals (including humans), on the other hand, nurture the fetus inside the body, with a placenta that helps exchange nutrients and waste between the mother's blood and the fetus.

The thylacine is one of the largest known carnivorous marsupial (marsupials that prey on other animals). At one time, the thylacine was fairly common in Tasmania, New Guinea, and throughout the Australian mainland. The thylacine was what we call an apex predator, which means it was at the top of the food chain in its range (it had no natural predators).

Although the thylacine is not related to dogs, it has a general dog shape. Because of this, it is sometimes called the Tasmanian wolf. The name Tasmanian tiger comes from the row of stripes on its back.

Amazing facts about the Thylacine

The thylacine is one of only two marsupials in which both males and females have a pouch. You already know what the female's pouch is for. The male's pouch serves as a protective covering for the external reproductive organs. Wait, what? That sounds like a no-brainer. Why don't all male mammals have those? Anyway, the only other marsupial that has this protective pouch in males is the water opossum.

The thylacine is a great example of what we call convergent evolution, in which unrelated creatures end up having similar structures because they have become well adapted to similar niches. The thylacine filled the same ecological niche in Australia as the dog has filled in other areas of the world. That's why it looks similar to a dog!

The skull below on the left is from a thylacine, and the skull on the right is from a timber wolf. Notice how similar they look, even though they are not closely related at all.

Since these creatures went extinct in the 1930s, we don't know much about their behavior. But from early recorded observations, we know that they ran with an odd, stiff gait, which made it difficult for the animal to run very fast. Occasionally they were also observed hopping on their back legs like a kangaroo. It is thought that they used this hopping motion when startled.

The thylacine also had an amazing ability to open its mouth, spreading its jaws to 80 degrees! Here's a 1933 photo of a thylacine yawning (which is a threat gesture). What a mouth!

How did the thylacine go extinct?

As stated above, thylacines once lived throughout mainland Australia and in parts of New Guinea. They went extinct in these places about 2,000 years ago. Although there is disagreement as to how the creature went extinct on the mainland, it is thought to be at least partly due to the arrival of the dingo (a dog native to Australia). But more recent studies suggest it may have been caused more by climate change and by the way Aborigines used the land. The dingo theory is debatable because the two animals are thought to have different hunting habits and prey. Why does this matter? Because if they had different prey, they probably did not compete with each other as much as we once thought.

However, the thylacines that had been isolated on the island of Tasmania escaped this fate (maybe because there are no dingoes on Tasmania). Even so, only about 5000 thylacines still lived in Tasmania when the first Europeans settled on the island in 1803.

This is when things really went downhill for the Tasmanian tiger. Soon after Europeans settled on Tasmania, they started complaining that thylacines were killing their sheep. Actually, there was more evidence that feral dogs and poor farming habits were really the culprits, but the farmers must have decided that the thylacine was easier to blame. By the 1830s, the farmers pooled their money and established a system of bounties for killing thylacines. And then the government started awarding bounties. By the time this practice ended in 1909, a total of 2,180 bounties had been awarded.

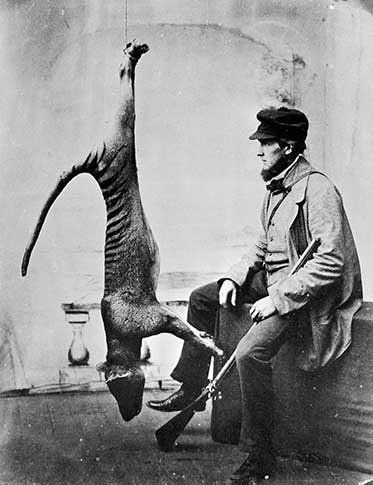

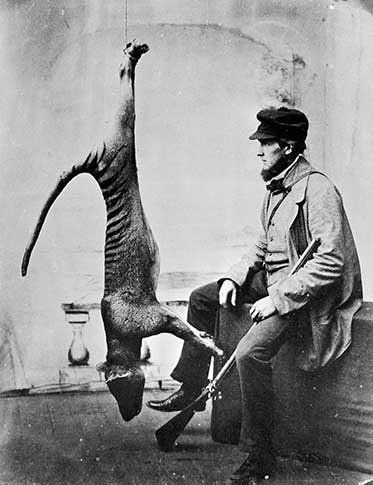

Below is a photo of a hunter posing with his "trophy" in 1869.

This excessive hunting, combined with habitat destruction, the introduction of foreign diseases, and competition from feral dogs decimated the population, and the last thylacine in the wild was shot in 1930.

At that time there was a shift in public opinion about thylacines, and preservation measures were put in place. But—you guessed it—this was far too late. Just 59 days after the species was granted "protected" status, the last individual in captivity died at the Hobart Zoo. Its name was Benjamin, and it died because the zookeepers accidentally locked Benjamin out of his sheltered sleeping quarters on a very cold night (I should point out, though, that these details about the name and the accident are now being challenged and may not be accurate).

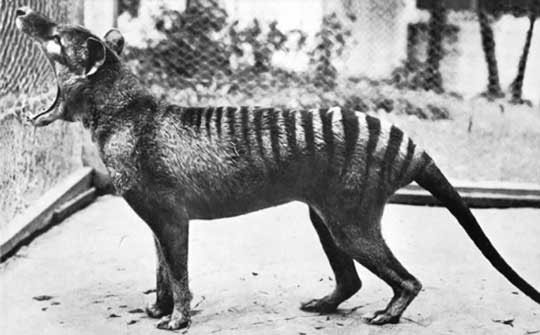

Here is a photo of Benjamin, taken in 1936, not long before he died:

People are still searching for Tasmanian tigers

Ever since the thylacine's extinction, many Australians have searched for these animals. In fact, some have devoted their entire lives to the search. But no definitive evidence has ever been found. No definite photos, no definite videos, no definite sightings by highly-qualified scientists.

You might be tempted to equate this with the search for Bigfoot in North America, or the search for "Nessie" in Loch Ness in Scotland. But... remember that the thylacine is a REAL animal, and it definitely lived only 83 years ago. Is it likely to be alive? Probably not. Is it possible ? Absolutely.

And what's interesting is that people have consistently reported sightings over the last 80 years. In Tasmania, hundreds of unconfirmed sightings have been reported. Astoundingly, 65 sighting have been reported on the Australian mainland, particularly in the southwest portion of Western Australia. And more recently sightings have been reported in northern Queensland. But... not one single confirmed photo, video, or sighting.

Hmm... What do you think? With all the technology we now have, especially trail cameras, wouldn't we have at least ONE definitive video or photo?

Perhaps the most intriguing video was captured by teacher Paul Day. Paul was photographing the sunrise in the Yorke Peninsula in northern Queensland when a creature ran across a field in front of him. The creature's strange hopping gait is much like what observers have described for the thylacine.

Check out the video!

I know, we all want to believe the Tasmanian tiger still exists. How cool would that be? But, perhaps we should remain skeptical, at least until someone comes up with undeniable proof.

Again, what do you think?

So, the Tasmanian Tiger deserves a place in the. B.O.A.A.H.O.F.

(Bit of Alright Animal Hall of Fame).

FUN FACT: The phrase bit of alright, as far as I can tell, is mainly used in Australia (making it especially suitable for the thylacine) and Great Britain. Typically it is used to describe someone as physically attractive (Example: "He's a bit of all right, isn't he?" said Isadora, looking at a tall man near the door.). Well, the Tasmanian tiger, in my opinion, is a very attractive creature (as extinct marsupials go), so bit of alright is another way to say awesome!

Photo Credits:

Tasmanian tiger #1 - Tasmanian Museum and Art Gallery via National Museum Australia

Thylacine and wolf skulls - Wikipedia

Tasmanian tiger yawning - Tasmanian Museum and Art Gallery via University of Melbourne

Tasmanian Tiger (Benjamin) - Getty Images via Foxnews.com

Screen shot of Paul Day's Video - National Geographic

In Australia, and particularly in the Australian island state of Tasmania, people are still looking for the Tasmanian tiger, also known as the Thylocine. Yep, they're still looking, even though the last of these creatures died in 1936.

The Tasmanian tiger is, no doubt, an awesome animal, so let's take a closer look. We'll also take a closer look at the never-ending search for this creature.

What the heck is a Tasmanian Tiger (Thylacine)?

First, the thylacine is a marsupial. You know what marsupials are, right? They are a group of mammals that give birth to very small young, which are then nurtured in an external pouch (includes kangaroos, koalas, opossums, wombats, and many more). Placental mammals (including humans), on the other hand, nurture the fetus inside the body, with a placenta that helps exchange nutrients and waste between the mother's blood and the fetus.

The thylacine is one of the largest known carnivorous marsupial (marsupials that prey on other animals). At one time, the thylacine was fairly common in Tasmania, New Guinea, and throughout the Australian mainland. The thylacine was what we call an apex predator, which means it was at the top of the food chain in its range (it had no natural predators).

Although the thylacine is not related to dogs, it has a general dog shape. Because of this, it is sometimes called the Tasmanian wolf. The name Tasmanian tiger comes from the row of stripes on its back.

Amazing facts about the Thylacine

The thylacine is one of only two marsupials in which both males and females have a pouch. You already know what the female's pouch is for. The male's pouch serves as a protective covering for the external reproductive organs. Wait, what? That sounds like a no-brainer. Why don't all male mammals have those? Anyway, the only other marsupial that has this protective pouch in males is the water opossum.

The thylacine is a great example of what we call convergent evolution, in which unrelated creatures end up having similar structures because they have become well adapted to similar niches. The thylacine filled the same ecological niche in Australia as the dog has filled in other areas of the world. That's why it looks similar to a dog!

The skull below on the left is from a thylacine, and the skull on the right is from a timber wolf. Notice how similar they look, even though they are not closely related at all.

Since these creatures went extinct in the 1930s, we don't know much about their behavior. But from early recorded observations, we know that they ran with an odd, stiff gait, which made it difficult for the animal to run very fast. Occasionally they were also observed hopping on their back legs like a kangaroo. It is thought that they used this hopping motion when startled.

The thylacine also had an amazing ability to open its mouth, spreading its jaws to 80 degrees! Here's a 1933 photo of a thylacine yawning (which is a threat gesture). What a mouth!

How did the thylacine go extinct?

As stated above, thylacines once lived throughout mainland Australia and in parts of New Guinea. They went extinct in these places about 2,000 years ago. Although there is disagreement as to how the creature went extinct on the mainland, it is thought to be at least partly due to the arrival of the dingo (a dog native to Australia). But more recent studies suggest it may have been caused more by climate change and by the way Aborigines used the land. The dingo theory is debatable because the two animals are thought to have different hunting habits and prey. Why does this matter? Because if they had different prey, they probably did not compete with each other as much as we once thought.

However, the thylacines that had been isolated on the island of Tasmania escaped this fate (maybe because there are no dingoes on Tasmania). Even so, only about 5000 thylacines still lived in Tasmania when the first Europeans settled on the island in 1803.

This is when things really went downhill for the Tasmanian tiger. Soon after Europeans settled on Tasmania, they started complaining that thylacines were killing their sheep. Actually, there was more evidence that feral dogs and poor farming habits were really the culprits, but the farmers must have decided that the thylacine was easier to blame. By the 1830s, the farmers pooled their money and established a system of bounties for killing thylacines. And then the government started awarding bounties. By the time this practice ended in 1909, a total of 2,180 bounties had been awarded.

Below is a photo of a hunter posing with his "trophy" in 1869.

This excessive hunting, combined with habitat destruction, the introduction of foreign diseases, and competition from feral dogs decimated the population, and the last thylacine in the wild was shot in 1930.

At that time there was a shift in public opinion about thylacines, and preservation measures were put in place. But—you guessed it—this was far too late. Just 59 days after the species was granted "protected" status, the last individual in captivity died at the Hobart Zoo. Its name was Benjamin, and it died because the zookeepers accidentally locked Benjamin out of his sheltered sleeping quarters on a very cold night (I should point out, though, that these details about the name and the accident are now being challenged and may not be accurate).

Here is a photo of Benjamin, taken in 1936, not long before he died:

People are still searching for Tasmanian tigers

Ever since the thylacine's extinction, many Australians have searched for these animals. In fact, some have devoted their entire lives to the search. But no definitive evidence has ever been found. No definite photos, no definite videos, no definite sightings by highly-qualified scientists.

You might be tempted to equate this with the search for Bigfoot in North America, or the search for "Nessie" in Loch Ness in Scotland. But... remember that the thylacine is a REAL animal, and it definitely lived only 83 years ago. Is it likely to be alive? Probably not. Is it possible ? Absolutely.

And what's interesting is that people have consistently reported sightings over the last 80 years. In Tasmania, hundreds of unconfirmed sightings have been reported. Astoundingly, 65 sighting have been reported on the Australian mainland, particularly in the southwest portion of Western Australia. And more recently sightings have been reported in northern Queensland. But... not one single confirmed photo, video, or sighting.

Hmm... What do you think? With all the technology we now have, especially trail cameras, wouldn't we have at least ONE definitive video or photo?

Perhaps the most intriguing video was captured by teacher Paul Day. Paul was photographing the sunrise in the Yorke Peninsula in northern Queensland when a creature ran across a field in front of him. The creature's strange hopping gait is much like what observers have described for the thylacine.

Check out the video!

I know, we all want to believe the Tasmanian tiger still exists. How cool would that be? But, perhaps we should remain skeptical, at least until someone comes up with undeniable proof.

Again, what do you think?

So, the Tasmanian Tiger deserves a place in the. B.O.A.A.H.O.F.