Stan C. Smith's Blog, page 27

May 17, 2020

Awesome Animal - Vinegaroon

For today's Awesome Animal I decided to pick a creature that looks scary but is actually harmless to humans. In fact, vinegaroons are handy to have around because they often prey on animals that can be harmful, such as scorpions.

VINEGAROON... the name sounds kind of creepy. Also, as one author put it, the name sounds like the most foul-tasting Girl Scout cookie ever.

They look like a cross between a spider and a scorpion, but they are not poisonous, they do not sting, and they are harmless to humans.

But... well, they do have the ability to squirt out a nice mixture of acetic acid and caprylic acid. But only if you make them really mad.

What the heck is a Vinegaroon?

Vinegaroons, also called whip scorpions, make up a small order (only about 100 species) of arachnids. Notice the eight legs in the above photo.

Most people know arachnids include spiders and scorpions. Besides spiders and scorpions, though, there are also some bizarre and lesser known groups of arachnids, such as ticks, mites, harvestmen (daddy longlegs), and others. Now, even horseshoe crabs might be included as arachnids. And of course we have the vinegaroons.

Vinegaroons, although their shape is vaguely scorpion-like, are not closely related to scorpions at all. They have a long, segmented, whip-like "tail" sticking out from the end of their abdomen, which is how they got the name whip scorpion.

They live in the warmer areas of North America, throughout Central and South America, and in the warmer areas of Asia.

Amazing facts about Vinegaroons

Vinegaroons are nocturnal. During the day they live in burrows that they dig with their large, clawed appendages that grow in front of their face. At night they emerge and roam around looking for prey. They mainly prey on insects and millipedes, but sometimes will catch small frogs and other small vertebrates. As you can probably guess, they use those ominous-looking pedipalps (kind of like mandibles) to crush their prey, then they can leisurely lap up the yummy juices that flow out of the squashed creature.

They have a pretty amazing way of finding their prey. Although vinegaroons have eight eyes, those eyes are pretty much useless for seeing prey animals. So, they use their sense of touch. When walking, they mostly use their three back pairs of legs. The fourth pair, near the front of the body, are adapted to be highly-sensitive feelers. As the creature roams around, these two legs tap the ground, feeling for anything that might be a tasty snack. And that long, funny-looking tail? That thing is used to feel around behind the vinegaroon. So, it can detect any suspicious activity or potential food in front and in back.

Check out those thin, extra-long, "feely" legs and the "feely" butt protuberance on the vinegaroon below.

Here's a good question. The vinegaroon is obviously a nice, plump critter, probably packed with nutrients. Also, the vinegaroon doesn't sting (remember, it isn't a scorpion), and although those pedipalps look vicious, they can't squeeze hard enough to hurt anything bigger than a peanut shell. So, why don't predators gobble up these creatures like crunchy popcorn? Well, remember that vinegaroons have a pretty cool defense—they squirt acid.

At the base of that long, feely tail are pygidial glands. These glands produce a mixture of chemicals consisting primarily of acetic acid and caprylic acid. You've probably heard of acetic acid. It's the main ingredient in vinegar.

Note: Vinegar contains 5% acetic acid, whereas the mixture squirted from a vinegaroon's butt has 85% acetic acid. Imagine the taste and smell of this stuff!

Check out this video with slow-motion clips of a vinegaroon squirting acid.

When really bothered, the vinegaroon can squirt this mixture out about twelve inches (30.5 cm) in any direction.

Wait... that's it? It's only defense (other than looking like the devil's spawn) is to squirt vinegar? Heck, some people put vinegar on their salads!

Well, a vinegaroon can accurately aim its acid butt-nozzles, and it's pretty good at squirting the stuff directly into the eyes, nose, and mouth of its predators. Remember, the stuff is 15 times more concentrated acetic acid than vinegar. Not something I want squirted in my eyes. Nope.

As a last resort, if the acid spray doesn't work, the vinegaroon will face off with its harasser and strike an impressive "back-off" pose (see photo above). Those pedipalps may not be as strong as they look, but it's all in the attitude.

Okay, let's move on to the important stuff... making babies. Vinegaroons have an astoundingly elaborate, drawn-out courtship ritual, which can often last at least 13 hours! This is a multi-stage procedure, so stay with me on this...

Stage 1. If a male encounters a female as he is out roaming around at night, he chases her down and begins shoving her around with his pedipalps. They grapple back and forth like this for up to several hours. It's a way for the female to determine if the male is good and strong (she is not interested in having the babies of a weakling). If the female decides he's okay, she will signal this by sticking her long, feely forelimbs into his mouth.

Stage 2. This stage is all about... dancing. The male, still holding the female's sensory legs in his mouth, starts dragging her this way and that way in an elaborate dance. During this dance, the female follows his lead. Again, this is to further evaluate each other's worth as a mate. This dance goes on for three or four hours. Sounds rather exhausting to me.

Stage 3. Time to get down to business... very slowly. By this time, if the two vinegaroons still approve of each other, the male will have maneuvered the female toward a burrow. Still holding on to the female's feely legs, he turns around and positions himself on top of her. They stay like this for several more hours. Eventually, the male will deposit a sac of sperm (called a spermatophore) onto the ground. He pushes the spermatophore into the female's genital opening. Finally, the male releases her feely legs and then starts massaging her abdomen. This massage goes on for a few more hours. The purpose of this might be to help the sperm move deeper into the female's body.

Stage 4. Well, there is no stage 4. After all those hours of courtship and mating, the male and female mutually agree to part ways. The female does not cannibalize the male, as is the case with many spiders. Yay for him!

The female carries the eggs for several months and then eventually seals herself in a burrow. She lays the eggs, but they stay connected to her abdomen for several more months. Um... during these months, the female vinegaroon does not eat anything. Nothing. Wow.

The eggs hatch, and out come larvae that look like pieces of rice with tiny legs. The larvae climb up onto the top of the female's abdomen and hang on with a specialized sucker organ for... yep, another month. finally, after their first molt, the babies start to wander off around the burrow. When she finally decides they are ready to be on their own, she digs out of the burrow, releasing them to take off and start their own lives. Exhausted and hungry, the female can finally get on with her life!

So, Vinegaroons deserve a place in the S.A.H.O.F.

(Supernal Animal Hall of Fame).

FUN FACT: The word supernal originated in the mid 1400s. It comes from the Latin supernus, meaning "situated above, that is above; celestial." Originally, the English word supernal meant "being in or belonging to the heaven of divine beings; heavenly, celestial, or divine." It is the opposite of infernal, which refers to "being of the underworld." For Kristen Bell fans, supernal means from The Good Place, while infernal refers to The Bad Place. Anyway, like many words, its usage has broadened so that it now often refers to anything that is exquisite or superlative. So, supernal is another way to say awesome!

Photo Credits:

Vinegaroon in hand #1 - Wikimedia Commons

Vinegaroon feeler legs and tail - Insect Adventure

Vinegaroon facing camera - Jonathon's Jungle Roadshow

Vinegaroons mating - Arlo Pelegrin via BugGuide

Vinegaroon with babies - Cowyeow on Flickr

VINEGAROON... the name sounds kind of creepy. Also, as one author put it, the name sounds like the most foul-tasting Girl Scout cookie ever.

They look like a cross between a spider and a scorpion, but they are not poisonous, they do not sting, and they are harmless to humans.

But... well, they do have the ability to squirt out a nice mixture of acetic acid and caprylic acid. But only if you make them really mad.

What the heck is a Vinegaroon?

Vinegaroons, also called whip scorpions, make up a small order (only about 100 species) of arachnids. Notice the eight legs in the above photo.

Most people know arachnids include spiders and scorpions. Besides spiders and scorpions, though, there are also some bizarre and lesser known groups of arachnids, such as ticks, mites, harvestmen (daddy longlegs), and others. Now, even horseshoe crabs might be included as arachnids. And of course we have the vinegaroons.

Vinegaroons, although their shape is vaguely scorpion-like, are not closely related to scorpions at all. They have a long, segmented, whip-like "tail" sticking out from the end of their abdomen, which is how they got the name whip scorpion.

They live in the warmer areas of North America, throughout Central and South America, and in the warmer areas of Asia.

Amazing facts about Vinegaroons

Vinegaroons are nocturnal. During the day they live in burrows that they dig with their large, clawed appendages that grow in front of their face. At night they emerge and roam around looking for prey. They mainly prey on insects and millipedes, but sometimes will catch small frogs and other small vertebrates. As you can probably guess, they use those ominous-looking pedipalps (kind of like mandibles) to crush their prey, then they can leisurely lap up the yummy juices that flow out of the squashed creature.

They have a pretty amazing way of finding their prey. Although vinegaroons have eight eyes, those eyes are pretty much useless for seeing prey animals. So, they use their sense of touch. When walking, they mostly use their three back pairs of legs. The fourth pair, near the front of the body, are adapted to be highly-sensitive feelers. As the creature roams around, these two legs tap the ground, feeling for anything that might be a tasty snack. And that long, funny-looking tail? That thing is used to feel around behind the vinegaroon. So, it can detect any suspicious activity or potential food in front and in back.

Check out those thin, extra-long, "feely" legs and the "feely" butt protuberance on the vinegaroon below.

Here's a good question. The vinegaroon is obviously a nice, plump critter, probably packed with nutrients. Also, the vinegaroon doesn't sting (remember, it isn't a scorpion), and although those pedipalps look vicious, they can't squeeze hard enough to hurt anything bigger than a peanut shell. So, why don't predators gobble up these creatures like crunchy popcorn? Well, remember that vinegaroons have a pretty cool defense—they squirt acid.

At the base of that long, feely tail are pygidial glands. These glands produce a mixture of chemicals consisting primarily of acetic acid and caprylic acid. You've probably heard of acetic acid. It's the main ingredient in vinegar.

Note: Vinegar contains 5% acetic acid, whereas the mixture squirted from a vinegaroon's butt has 85% acetic acid. Imagine the taste and smell of this stuff!

Check out this video with slow-motion clips of a vinegaroon squirting acid.

When really bothered, the vinegaroon can squirt this mixture out about twelve inches (30.5 cm) in any direction.

Wait... that's it? It's only defense (other than looking like the devil's spawn) is to squirt vinegar? Heck, some people put vinegar on their salads!

Well, a vinegaroon can accurately aim its acid butt-nozzles, and it's pretty good at squirting the stuff directly into the eyes, nose, and mouth of its predators. Remember, the stuff is 15 times more concentrated acetic acid than vinegar. Not something I want squirted in my eyes. Nope.

As a last resort, if the acid spray doesn't work, the vinegaroon will face off with its harasser and strike an impressive "back-off" pose (see photo above). Those pedipalps may not be as strong as they look, but it's all in the attitude.

Okay, let's move on to the important stuff... making babies. Vinegaroons have an astoundingly elaborate, drawn-out courtship ritual, which can often last at least 13 hours! This is a multi-stage procedure, so stay with me on this...

Stage 1. If a male encounters a female as he is out roaming around at night, he chases her down and begins shoving her around with his pedipalps. They grapple back and forth like this for up to several hours. It's a way for the female to determine if the male is good and strong (she is not interested in having the babies of a weakling). If the female decides he's okay, she will signal this by sticking her long, feely forelimbs into his mouth.

Stage 2. This stage is all about... dancing. The male, still holding the female's sensory legs in his mouth, starts dragging her this way and that way in an elaborate dance. During this dance, the female follows his lead. Again, this is to further evaluate each other's worth as a mate. This dance goes on for three or four hours. Sounds rather exhausting to me.

Stage 3. Time to get down to business... very slowly. By this time, if the two vinegaroons still approve of each other, the male will have maneuvered the female toward a burrow. Still holding on to the female's feely legs, he turns around and positions himself on top of her. They stay like this for several more hours. Eventually, the male will deposit a sac of sperm (called a spermatophore) onto the ground. He pushes the spermatophore into the female's genital opening. Finally, the male releases her feely legs and then starts massaging her abdomen. This massage goes on for a few more hours. The purpose of this might be to help the sperm move deeper into the female's body.

Stage 4. Well, there is no stage 4. After all those hours of courtship and mating, the male and female mutually agree to part ways. The female does not cannibalize the male, as is the case with many spiders. Yay for him!

The female carries the eggs for several months and then eventually seals herself in a burrow. She lays the eggs, but they stay connected to her abdomen for several more months. Um... during these months, the female vinegaroon does not eat anything. Nothing. Wow.

The eggs hatch, and out come larvae that look like pieces of rice with tiny legs. The larvae climb up onto the top of the female's abdomen and hang on with a specialized sucker organ for... yep, another month. finally, after their first molt, the babies start to wander off around the burrow. When she finally decides they are ready to be on their own, she digs out of the burrow, releasing them to take off and start their own lives. Exhausted and hungry, the female can finally get on with her life!

So, Vinegaroons deserve a place in the S.A.H.O.F.

(Supernal Animal Hall of Fame).

FUN FACT: The word supernal originated in the mid 1400s. It comes from the Latin supernus, meaning "situated above, that is above; celestial." Originally, the English word supernal meant "being in or belonging to the heaven of divine beings; heavenly, celestial, or divine." It is the opposite of infernal, which refers to "being of the underworld." For Kristen Bell fans, supernal means from The Good Place, while infernal refers to The Bad Place. Anyway, like many words, its usage has broadened so that it now often refers to anything that is exquisite or superlative. So, supernal is another way to say awesome!

Photo Credits:

Vinegaroon in hand #1 - Wikimedia Commons

Vinegaroon feeler legs and tail - Insect Adventure

Vinegaroon facing camera - Jonathon's Jungle Roadshow

Vinegaroons mating - Arlo Pelegrin via BugGuide

Vinegaroon with babies - Cowyeow on Flickr

Published on May 17, 2020 05:21

April 28, 2020

Awesome Animal - Legless Lizard

I was probably about ten years old when I saw my first legless lizard. I was fishing with my dad and his friend, who happened to be a biologist. We came upon what I thought was a snake. But my dad's friend pointed out that it was actually a "slender glass lizard," a type of lizard without legs. This blew my mind! A long, skinny reptile without legs had to be a snake, right? Nope, not necessarily. Consequently, I've been fascinated by legless lizards ever since then. Below is a slender glass lizard, the same kind I saw that day fifty years ago.

What the heck is a Legless Lizard?

Actually, the term legless lizard is used to refer to a variety of different types of lizards that have lost their legs over time. In different areas of the world, these different groups have lost their legs independently of each other and are not closely related.

Amazingly, at least SEVEN different families of lizards have evolved legless species independently! This includes hundreds of species of legless lizards around the world.

The first question people often have is, why don't we just call these creatures snakes ? Well, because they aren't snakes. Other than being legless, these creatures do not have the characteristics of snakes. Legless lizards have eyelids, snakes do not. Legless lizards have external ears, snakes do not. Legless lizards do not have wide belly scales, snake do. Legless lizards have short bodies and long tails, snakes have long bodies and short tails.

Not confusing at all, right? Check out the head of the European glass lizard below (this species also has the awesome name scheltopusik). You can see the lizard's eyelids, which allows it to close its eyes. You can also see its ear openings (behind the mouth). And behind that you can see part of the lateral fold, a weird fold of skin that runs the length of the lizard on each side. Snakes do not have any of these characteristics.

Amazing facts about Legless Lizards

Again, legless lizards are not snakes. They evolved from four-legged lizards, like those we have all seen. Snakes evolved from four-legged snake-like creatures that most of us have never seen (most of those lived long ago).

Legless lizards eat smaller prey than snakes because they cannot "unlock" their jaws. As you probably know, snakes can unhinge their jaws to swallow prey bigger around than their own head. Lizards cannot do this. Legless lizards typically eat insects, snails, spiders, and other small prey that will fit conveniently in their mouth. So, a typical snake will eat just occasionally, swallowing an animal large enough to sustain it for a while. A legless lizard eats small things frequently.

Below is a Burton's legless lizard eating a smaller lizard.

Many legless lizards are called glass lizards. Here's why. You may know some lizards are capable of losing all or a portion of their tail when attacked by a predator. They can then grow the tail back (at least partially). Well, glass lizards are very good at this. Not only do they have a really long tail, but the tail is extremely fragile. In fact, they can even break their tail off by themselves. They can actually thrash around hard enough to break it off without ever being touched. Since that day fifty years ago, I have found perhaps twenty or so slender glass lizards, and almost all of them had broken their tail at some point in their lives. You can easily tell because, once broken, the tail does not grow back the same way as before.

Notice the regenerated tail of the eastern glass lizard below.

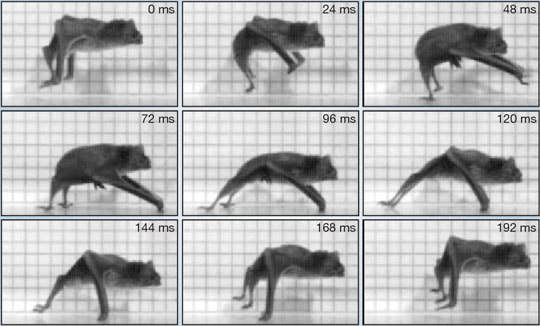

This tail-breaking ability is called caudal autotomy (the word autotomy in Greek means "self severing"). This is really an amazing capability—the tail continues wriggling, which distracts the predator's attention from the fleeing lizard. As the lizard gradually regenerates the tail, instead of growing new vertebrae made of bone, the tail usually contains cartilage and is shorter than the original tail. Lizards have special sphincter muscles in the tail that squeeze the caudal artery closed to minimize the amount of bleeding.

Fossils have been found that show caudal autotomy was present in some lizards as long ago as the Jurassic period! Most likely, small lizards were escaping from the clutches of dinosaurs by dropping their tails!

Check out this video by Jungle Bob on legless lizards.

Okay, one last thing... WHY? Why have so many species of lizards evolved to have no legs? Wouldn't they be better off with legs? Well, first of all, we have to recognize that the long, slithery, legless lifestyle must be a pretty good one. Otherwise, snakes and legless lizards wouldn't be so abundant. It also helps to consider that creatures living underground may be better off without legs (think about worms).

So, it's quite possible legless lizards evolved as some types of lizards started living in the soil. As they became more and more adapted to life in the soil, they gradually lost their legs. Then, later, some of those started living above ground again, but by that time they had already lost their legs. Makes perfect sense, right?

To make things even more confusing, there are some snakes that still have remnants of legs (boas and pythons are examples), and there are some legless lizards that have legs! Legless lizards in the family Pygopodidae don't have forelimbs, but they have small remnants of hind legs.

Make up your mind, why don't you! Legs or no legs?

Hmm... whoever came up with the phrase "Leaping lizards!" probably wasn't thinking about legless lizards. I just thought I'd toss that thought into the mix. You're welcome.

So, Legless Lizards deserve a place in the J.D.A.H.O.F.

(Jim-Dandy Animal Hall of Fame).

FUN FACT: The term jim-dandy was first used in the Courier-Journal newspaper in Louisville, Kentucky in 1887: "Dear Sir: Though a stranger to you (yet a Democrat), let me say you are a 'Jim Dandy.'" This term can be both a noun (as used above) and an adjective. As a noun, it means something that is "a superior example of its kind." As an adjective, it means excellent or outstanding. Etymologists are not sure if the term ever referred to an actual person. But there was a popular minstrel song in the 1840s called "Dandy Jim of Caroline." Perhaps that's what gave people the idea of using the phrase? The word dandy dates back to the late 1700s, and it referred to a young man "who devotes excessive attention to fashionable dress and grooming." Anyway, jim-dandy is another way to say awesome! Photo Credits:

Baby elephant trunk - Imgur

Sloth - finstad4

Slender glass lizard - Todd Pierson, Herps of NC

European glass lizard head - Australian Reptile Park

Burton's Legless lizard eating a skink - Luke Jongens/Flickr

Eastern glass lizard with regenerated tail - Pinterest

Legless lizard lifting its head - San Diego Zoo

What the heck is a Legless Lizard?

Actually, the term legless lizard is used to refer to a variety of different types of lizards that have lost their legs over time. In different areas of the world, these different groups have lost their legs independently of each other and are not closely related.

Amazingly, at least SEVEN different families of lizards have evolved legless species independently! This includes hundreds of species of legless lizards around the world.

The first question people often have is, why don't we just call these creatures snakes ? Well, because they aren't snakes. Other than being legless, these creatures do not have the characteristics of snakes. Legless lizards have eyelids, snakes do not. Legless lizards have external ears, snakes do not. Legless lizards do not have wide belly scales, snake do. Legless lizards have short bodies and long tails, snakes have long bodies and short tails.

Not confusing at all, right? Check out the head of the European glass lizard below (this species also has the awesome name scheltopusik). You can see the lizard's eyelids, which allows it to close its eyes. You can also see its ear openings (behind the mouth). And behind that you can see part of the lateral fold, a weird fold of skin that runs the length of the lizard on each side. Snakes do not have any of these characteristics.

Amazing facts about Legless Lizards

Again, legless lizards are not snakes. They evolved from four-legged lizards, like those we have all seen. Snakes evolved from four-legged snake-like creatures that most of us have never seen (most of those lived long ago).

Legless lizards eat smaller prey than snakes because they cannot "unlock" their jaws. As you probably know, snakes can unhinge their jaws to swallow prey bigger around than their own head. Lizards cannot do this. Legless lizards typically eat insects, snails, spiders, and other small prey that will fit conveniently in their mouth. So, a typical snake will eat just occasionally, swallowing an animal large enough to sustain it for a while. A legless lizard eats small things frequently.

Below is a Burton's legless lizard eating a smaller lizard.

Many legless lizards are called glass lizards. Here's why. You may know some lizards are capable of losing all or a portion of their tail when attacked by a predator. They can then grow the tail back (at least partially). Well, glass lizards are very good at this. Not only do they have a really long tail, but the tail is extremely fragile. In fact, they can even break their tail off by themselves. They can actually thrash around hard enough to break it off without ever being touched. Since that day fifty years ago, I have found perhaps twenty or so slender glass lizards, and almost all of them had broken their tail at some point in their lives. You can easily tell because, once broken, the tail does not grow back the same way as before.

Notice the regenerated tail of the eastern glass lizard below.

This tail-breaking ability is called caudal autotomy (the word autotomy in Greek means "self severing"). This is really an amazing capability—the tail continues wriggling, which distracts the predator's attention from the fleeing lizard. As the lizard gradually regenerates the tail, instead of growing new vertebrae made of bone, the tail usually contains cartilage and is shorter than the original tail. Lizards have special sphincter muscles in the tail that squeeze the caudal artery closed to minimize the amount of bleeding.

Fossils have been found that show caudal autotomy was present in some lizards as long ago as the Jurassic period! Most likely, small lizards were escaping from the clutches of dinosaurs by dropping their tails!

Check out this video by Jungle Bob on legless lizards.

Okay, one last thing... WHY? Why have so many species of lizards evolved to have no legs? Wouldn't they be better off with legs? Well, first of all, we have to recognize that the long, slithery, legless lifestyle must be a pretty good one. Otherwise, snakes and legless lizards wouldn't be so abundant. It also helps to consider that creatures living underground may be better off without legs (think about worms).

So, it's quite possible legless lizards evolved as some types of lizards started living in the soil. As they became more and more adapted to life in the soil, they gradually lost their legs. Then, later, some of those started living above ground again, but by that time they had already lost their legs. Makes perfect sense, right?

To make things even more confusing, there are some snakes that still have remnants of legs (boas and pythons are examples), and there are some legless lizards that have legs! Legless lizards in the family Pygopodidae don't have forelimbs, but they have small remnants of hind legs.

Make up your mind, why don't you! Legs or no legs?

Hmm... whoever came up with the phrase "Leaping lizards!" probably wasn't thinking about legless lizards. I just thought I'd toss that thought into the mix. You're welcome.

So, Legless Lizards deserve a place in the J.D.A.H.O.F.

(Jim-Dandy Animal Hall of Fame).

FUN FACT: The term jim-dandy was first used in the Courier-Journal newspaper in Louisville, Kentucky in 1887: "Dear Sir: Though a stranger to you (yet a Democrat), let me say you are a 'Jim Dandy.'" This term can be both a noun (as used above) and an adjective. As a noun, it means something that is "a superior example of its kind." As an adjective, it means excellent or outstanding. Etymologists are not sure if the term ever referred to an actual person. But there was a popular minstrel song in the 1840s called "Dandy Jim of Caroline." Perhaps that's what gave people the idea of using the phrase? The word dandy dates back to the late 1700s, and it referred to a young man "who devotes excessive attention to fashionable dress and grooming." Anyway, jim-dandy is another way to say awesome! Photo Credits:

Baby elephant trunk - Imgur

Sloth - finstad4

Slender glass lizard - Todd Pierson, Herps of NC

European glass lizard head - Australian Reptile Park

Burton's Legless lizard eating a skink - Luke Jongens/Flickr

Eastern glass lizard with regenerated tail - Pinterest

Legless lizard lifting its head - San Diego Zoo

Published on April 28, 2020 15:04

April 15, 2020

Awesome Animal - Coral

In keeping with my theme of positive, happy subjects, I again asked Trish to give me an idea for an animal that makes her happy (last time she said Nemo... the clownfish). This time she said, "My happiest happy place is snorkeling in a coral reef! So you should feature coral."

Trish wasn't kidding about this. I enjoy snorkeling, too, but to her it is almost a spiritual experience. She actually tears up when snorkeling among the corals (have you ever tried wiping tears away while wearing a face mask?). So, coral is another excellent suggestion. Besides, some people may not really know what corals are... or that they are even animals. So let's take a look.

What the heck is a Coral?

Corals are invertebrate animals in the phylum Cnidaria, which also includes sea anemones, sea pens, jellyfish, box jellyfish, and hydrozoans such as the Portuguese Man o' War.

Actually, it's kind of silly of me to lump all types of corals together in this email, as corals represent a diverse group of animals. After all, there are about 2,500 species. Of those, about 1,000 species are reef-forming corals. These are the corals that form a hard skeleton by secreting calcium carbonate. Over many years these hard skeletons build up and form massive coral reefs.

Amazing facts about Corals

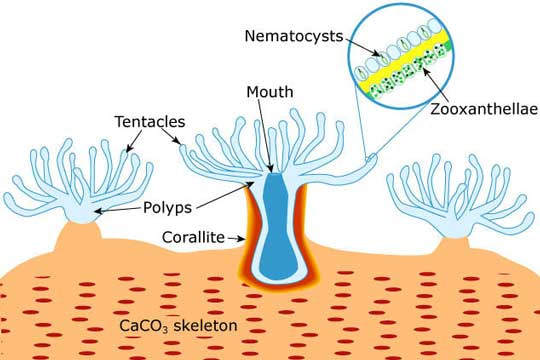

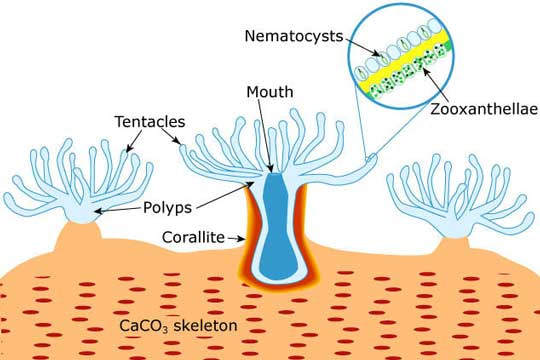

First let's talk about what a coral is. Corals generally live in large colonies of genetically-identical individuals. Each individual coral is called a polyp.

If you look at an individual polyp, you will see tentacles. In the center of the tentacles is a mouth that leads to a basic stomach, or digestive sac. Each of the tentacles is lined with stinging cells called nematocysts. As you can probably guess, these stinging cells help the coral defend itself and help it capture its prey, which is usually tiny animals swimming in the surrounding water.

The polyp's body secretes calcium carbonate that forms a hard protective shell around the polyp. This cup-like shell is called a corallite. Over time, millions of corallites build up upon each other to form massive coral reefs and outcrops (see the coral outcrop in the photo above). Some coral reefs are big enough to be seen from space!

Below is a simple diagram.

Coral polyps have only one opening. Yep, only one—the mouth. That means food goes in the mouth, and waste goes... well, back out the mouth. Eww. I'm glad I have an anus.

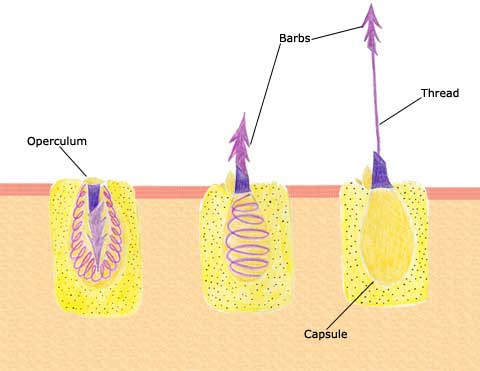

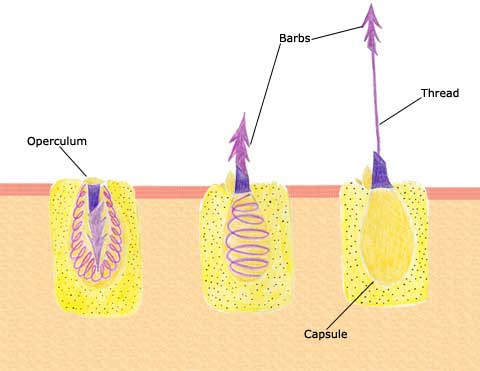

Nematocysts (stinging cells) are pretty awesome. If you've ever been stung by a jellyfish, you know how awesome nematocysts are (awesome for the jellyfish, not for you).

Let's look at how these nematocysts work. Basically, they're like a spear gun shooting a barbed dart, and the dart contain toxins that can be lethal. These tiny darts are contained within a cellular capsule, connected to a thread that is coiled up under pressure. When a prey animal touches the polyp's tentacle, the cellular capsule's covering (called the operculum) pops open, and the thread rapidly uncoils, shooting the dart out at high speed. The dart punctures the prey animal and releases its toxins. Like I said... awesome!

If you've ever snorkeled in a coral reef, you may be thinking, "Wait, I didn't see all those tentacles. All I saw were the hard coral boulders, outcrops, and reefs." Well, that's probably because many corals extend their tentacles mainly at night.

By the way. Snorkeling at night in the ocean or sea can be amazing, but it's also kind of scary. Trish and I have done this twice (while taking marine biology classes together), and I can tell you there is something deeply frightening (but also exhilarating) about not being able to see in the water beyond the range of your waterproof flashlight. It's worth it, though, because the corals are particularly beautiful at night!

Below is what corals usually look like during the day (left) and at night (right).

Corals eat just about anything they can catch, from nearly-microscopic plankton to small fish. Whatever they can kill with their stinging cells is fair game.

But wait! It's not that simple. Many corals also feed in a different way. They have a mutualistic relationship with specialized algae called zooxanthellae. These algae live on and in the coral polyp and can actually be 30% of the polyp's mass.

What does the coral polyp get out of this relationship? The algae are photosynthetic, which means they use sunlight to produce food, and they share that food with the polyp, particularly glucose, glycerol, and amino acids. The algae also help by removing waste particles, and they help with producing the hard shell, the corallite.

What do the algae get out of this relationship? Well, they get a safe place to live, protected by those awesome stinging cells. They also get to feed on the polyp's yummy waste, particularly carbon dioxide, phosphate, and nitrogenous waste.

I should point out that, when water conditions get bad, the internal algae can become stressful to the polyp. When this happens, the polyp will eject the algae in order to give itself a better chance to survive the difficult times. When the water gets really bad, mass ejections can occur, and this is called coral bleaching. Vast areas of coral reefs can turn white, because it was the algae that gave the corals their diverse colors in the first place. Coral bleaching can be caused by pollution or by an increase in water temperature. If the bad conditions continue for too long, the coral polyps will die.

The image below shows the before and after appearance of coral bleaching. Unfortunately, coal bleaching is becoming a big problem, but since this email is all about being positive, I'm not going to focus too much on that.

Here are a few more amazing facts about coral.

Corals have been around for a long time. They originated about 500 million years ago, long before dinosaurs existed. Coral reefs grow very slowly, only about 2 cm per year, and some of today's reefs have been forming for 50 million years.

When coral reefs grow parallel to the coast, they are called barrier reefs. The Great Barrier Reef in Australia has grown to include 900 smaller reefs, and it extends for 2,600 miles (4,184 km).

Coral reefs provide a home for an incredible variety of wildlife. Coral reefs take up only about 1% of the ocean floor, but they provide a home for as much as 25% of all species in the oceans!

White sandy beaches are actually made of coral pooped from fish. Yep, it's true. Some types of fish, such as parrotfish, like to nibble on corals to eat the algae living in the polyps. Once the fish have digested the goodies, they poop out the hard calcium carbonate shell as tiny granules of sand. These sandy poop granules help make up those nice white beaches we all like to lay on. Check out the beak on the purplestreak parrotfish below. That beak can chomp right through the coral shell, and one parrotfish can poop out 200 pounds (90 kg) of white sand per year!

So, Corals deserve a place in the C.A.H.O.F.

(Corking Animal Hall of Fame).

FUN FACT: The word corking originated in about 1890, and is used, particularly in British English, as an adjective to describe something as excellent or fine. Example: "It was a corking celebration." Often it is paired with another word, particularly good, as in "That Bridgers book was a corking good read." Anyway, the word corking came from the word corker. The word corker is a slang term from the early 1800s that originally meant “something that settles and puts a definite end to a discussion or argument,” a reference to how a cork tightly seals a wine bottle. Then corker was eventually used to describe anything as good or excellent: "That was a corker of a joke." Eventually, the adjective corking arose from that.

So, corking is another way to say awesome!

Photo Credits:

Happy dog - Twitter

Penguin rover - Le Maho et. al via Nature... via Buzzfeed

Giraffe Manor - The Giraffe Manor

Coral outcrop in Australia - Toby Hudson/Wikimedia Commons

Coral anatomy - USGS/Public Domain

Bleached coral - Green and Growing

Parrotfish - metha1819/Shutterstock via Marine Conservation Society

Trish wasn't kidding about this. I enjoy snorkeling, too, but to her it is almost a spiritual experience. She actually tears up when snorkeling among the corals (have you ever tried wiping tears away while wearing a face mask?). So, coral is another excellent suggestion. Besides, some people may not really know what corals are... or that they are even animals. So let's take a look.

What the heck is a Coral?

Corals are invertebrate animals in the phylum Cnidaria, which also includes sea anemones, sea pens, jellyfish, box jellyfish, and hydrozoans such as the Portuguese Man o' War.

Actually, it's kind of silly of me to lump all types of corals together in this email, as corals represent a diverse group of animals. After all, there are about 2,500 species. Of those, about 1,000 species are reef-forming corals. These are the corals that form a hard skeleton by secreting calcium carbonate. Over many years these hard skeletons build up and form massive coral reefs.

Amazing facts about Corals

First let's talk about what a coral is. Corals generally live in large colonies of genetically-identical individuals. Each individual coral is called a polyp.

If you look at an individual polyp, you will see tentacles. In the center of the tentacles is a mouth that leads to a basic stomach, or digestive sac. Each of the tentacles is lined with stinging cells called nematocysts. As you can probably guess, these stinging cells help the coral defend itself and help it capture its prey, which is usually tiny animals swimming in the surrounding water.

The polyp's body secretes calcium carbonate that forms a hard protective shell around the polyp. This cup-like shell is called a corallite. Over time, millions of corallites build up upon each other to form massive coral reefs and outcrops (see the coral outcrop in the photo above). Some coral reefs are big enough to be seen from space!

Below is a simple diagram.

Coral polyps have only one opening. Yep, only one—the mouth. That means food goes in the mouth, and waste goes... well, back out the mouth. Eww. I'm glad I have an anus.

Nematocysts (stinging cells) are pretty awesome. If you've ever been stung by a jellyfish, you know how awesome nematocysts are (awesome for the jellyfish, not for you).

Let's look at how these nematocysts work. Basically, they're like a spear gun shooting a barbed dart, and the dart contain toxins that can be lethal. These tiny darts are contained within a cellular capsule, connected to a thread that is coiled up under pressure. When a prey animal touches the polyp's tentacle, the cellular capsule's covering (called the operculum) pops open, and the thread rapidly uncoils, shooting the dart out at high speed. The dart punctures the prey animal and releases its toxins. Like I said... awesome!

If you've ever snorkeled in a coral reef, you may be thinking, "Wait, I didn't see all those tentacles. All I saw were the hard coral boulders, outcrops, and reefs." Well, that's probably because many corals extend their tentacles mainly at night.

By the way. Snorkeling at night in the ocean or sea can be amazing, but it's also kind of scary. Trish and I have done this twice (while taking marine biology classes together), and I can tell you there is something deeply frightening (but also exhilarating) about not being able to see in the water beyond the range of your waterproof flashlight. It's worth it, though, because the corals are particularly beautiful at night!

Below is what corals usually look like during the day (left) and at night (right).

Corals eat just about anything they can catch, from nearly-microscopic plankton to small fish. Whatever they can kill with their stinging cells is fair game.

But wait! It's not that simple. Many corals also feed in a different way. They have a mutualistic relationship with specialized algae called zooxanthellae. These algae live on and in the coral polyp and can actually be 30% of the polyp's mass.

What does the coral polyp get out of this relationship? The algae are photosynthetic, which means they use sunlight to produce food, and they share that food with the polyp, particularly glucose, glycerol, and amino acids. The algae also help by removing waste particles, and they help with producing the hard shell, the corallite.

What do the algae get out of this relationship? Well, they get a safe place to live, protected by those awesome stinging cells. They also get to feed on the polyp's yummy waste, particularly carbon dioxide, phosphate, and nitrogenous waste.

I should point out that, when water conditions get bad, the internal algae can become stressful to the polyp. When this happens, the polyp will eject the algae in order to give itself a better chance to survive the difficult times. When the water gets really bad, mass ejections can occur, and this is called coral bleaching. Vast areas of coral reefs can turn white, because it was the algae that gave the corals their diverse colors in the first place. Coral bleaching can be caused by pollution or by an increase in water temperature. If the bad conditions continue for too long, the coral polyps will die.

The image below shows the before and after appearance of coral bleaching. Unfortunately, coal bleaching is becoming a big problem, but since this email is all about being positive, I'm not going to focus too much on that.

Here are a few more amazing facts about coral.

Corals have been around for a long time. They originated about 500 million years ago, long before dinosaurs existed. Coral reefs grow very slowly, only about 2 cm per year, and some of today's reefs have been forming for 50 million years.

When coral reefs grow parallel to the coast, they are called barrier reefs. The Great Barrier Reef in Australia has grown to include 900 smaller reefs, and it extends for 2,600 miles (4,184 km).

Coral reefs provide a home for an incredible variety of wildlife. Coral reefs take up only about 1% of the ocean floor, but they provide a home for as much as 25% of all species in the oceans!

White sandy beaches are actually made of coral pooped from fish. Yep, it's true. Some types of fish, such as parrotfish, like to nibble on corals to eat the algae living in the polyps. Once the fish have digested the goodies, they poop out the hard calcium carbonate shell as tiny granules of sand. These sandy poop granules help make up those nice white beaches we all like to lay on. Check out the beak on the purplestreak parrotfish below. That beak can chomp right through the coral shell, and one parrotfish can poop out 200 pounds (90 kg) of white sand per year!

So, Corals deserve a place in the C.A.H.O.F.

(Corking Animal Hall of Fame).

FUN FACT: The word corking originated in about 1890, and is used, particularly in British English, as an adjective to describe something as excellent or fine. Example: "It was a corking celebration." Often it is paired with another word, particularly good, as in "That Bridgers book was a corking good read." Anyway, the word corking came from the word corker. The word corker is a slang term from the early 1800s that originally meant “something that settles and puts a definite end to a discussion or argument,” a reference to how a cork tightly seals a wine bottle. Then corker was eventually used to describe anything as good or excellent: "That was a corker of a joke." Eventually, the adjective corking arose from that.

So, corking is another way to say awesome!

Photo Credits:

Happy dog - Twitter

Penguin rover - Le Maho et. al via Nature... via Buzzfeed

Giraffe Manor - The Giraffe Manor

Coral outcrop in Australia - Toby Hudson/Wikimedia Commons

Coral anatomy - USGS/Public Domain

Bleached coral - Green and Growing

Parrotfish - metha1819/Shutterstock via Marine Conservation Society

Published on April 15, 2020 08:15

April 2, 2020

Awesome Animal - Clownfish

Due to the difficult times we are living in, when I sat down to write this email, I told Trish I wanted to make it as positive as possible, and I asked her, "What's the most positive animal you can think of?"

She said, "Nemo!"

I had to agree. Nemo is a very positive fish. The little guy never gives up and never loses faith. So, for that simple reason, the clownfish is today's Awesome Animal!

What the heck is a Clownfish?

The clownfish, also called the anemonefish, includes about thirty species of fish that form an amazing symbiotic relationship with sea anemones. They are brightly colored, often with various patterns of orange, black, and white.

Clownfish live mostly in coral reefs and shallow lagoons in the Indian and Pacific oceans. Nemo lives near Sydney, Australia, remember?

Amazing facts about Clownfish

Let's talk about this strange relationship between clownfish and anemones.

First a few definitions. Symbiosis is when two living things develop a close, long-term biological relationship with each other. There are three basic types of symbiosis: mutualism, commensalism, and parasitism.

Mutualism is when both organisms benefit. An example is lichens, in which fungi and algae (or sometimes cyanobacteria) live together and benefit from each other.

Commensalism is when one organism benefits, but the other doesn't really care (it isn't helped nor hurt). An example is the remora, a fish that suctions onto a larger fish (like a shark). It gets a free ride and leftover scraps of food, but the larger fish is neither helped nor harmed.

Parasitism is when one organism is benefited while the other is harmed or even killed. A well-known example is the tapeworm, which lives in the intestines of larger animals, stealing the larger animal's ingested food and often weakening the animal (called the host).

In my Diffusion series, humans and tree kangaroos form a symbiotic, mutualistic relationship, in which... well, you'll just have to read the series if you want to know more about that (you'll be glad you did).

Okay, back to the clownfish. Most clownfish species only form relationships with specific species of anemones. In fact, there are over 1,000 species of anemones, but only ten of those species can coexist with clownfish.

This is an example of mutualistic symbiosis. So, both animals benefit.

What does the clownfish get out of this? First, the sea anemone provides protection from predators. Sea anemone tentacles are poisonous and can sting and kill other fish. Second, the clownfish gets to eat scraps of fish left over from the anemone's meals, as well as anemone excrement and the occasional tentacle that breaks off. Third, the clownfish can raise its young in the safety of the tentacles.

What does the anemone get out of this deal? First, the clownfish defends the anemone from parasites and predators. Second, when the clownfish poops on the anemone, the nitrogen from this poop increases the amount of algae growing in the anemone's tissue. Third, if you watch a clownfish, you'll see that it constantly moves around among the anemone's tentacles. This movement helps circulate water around the anemone, increasing the anemone's oxygen intake.

Wow, how awesome is that relationship? Everybody wins! Well, except the prey fish that get attracted to the anemone's deadly stingers.

Below are two saddleback clownfish. Notice the juveniles beneath the anemone—we're going to talk about those in a moment.

Why do clownfish have such bright colors? One idea is that the bright colors attract small fish to the anemone, which are then killed by the anemone's stingers and consumed by the anemone.

Here's a good question... why don't the anemone's stingers harm or kill the clownfish? A layer of mucus on the clownfish's body protects it from the stings. When a clownfish decides to live with a new anemone, it does an elaborate "dance" among the anemone's tentacles. It swims about, touching the tentacles with different parts of its body, until the anemone becomes acclimated to its body.

It's worth pointing out that the fish's mucus is made up mostly of sugars instead of proteins, so it's possible the anemone may not recognize the fish as prey and therefore does not sting.

It's also worth pointing out that clownfish are not really immune to the anemone's stings. Studies have shown that, if the mucus is removed, the anemones can kill the clownfish. So, it's all about the mucus!

Check out this video about the clownfish/anemone relationship.

Below is a tomato clownfish.

Clownfish usually live in groups with an anemone, and the social structure is rather bizarre. We'll call the group of fish a colony. Each colony includes a breeding pair and then several additional, younger, non-dominant males. The breeding female is the boss, and she gets to live in the best room in the house, the top of the anemone. That's where the most food is (and I suppose it also has the best view).

Now here's where things get kind of weird. All clownfish are born as males. Yep, all of them. When something happens to the breeding female in a colony (the boss)—if she dies, for example—the breeding male switches sexes and becomes the breeding female (that was not a typo). The largest of the juvenile males then experiences a rapid spurt of growth and quickly develops into the breeding male.

Here's a good question... There's one breeding male, right? That male is the boss of the other males (but not of the female). Since that male likes being the one male lucky enough to breed with the female, why doesn't he kick all those smaller males out of the colony so that he doesn't have to worry about them sneaking upstairs and breeding with the female?

Here's the simplified answer. The smaller males modify their growth rate, purposely remaining small and submissive so that they are not a threat to the boss male. That way they get to stay in the colony, hoping to someday have the chance to become the boss male when the breeding female dies.

See? Clownfish are POSITIVE fish—always hopeful!

Below is a Clarkii clownfish.

Clownfish are wildly popular among aquarium enthusiasts. In fact, most of those you see in pet shops are bred in captivity rather than caught in the wild (Nemo would like that—he was caught in the wild). Selective breeding has resulted in a wide variety of "designer clownfish," with amazing colors and patterns. Below I put together several striking examples into one image.

So, the Clownfish deserves a place in the S.A.H.O.F.

(Scrumptious Animal Hall of Fame).

FUN FACT: The word scrumptious originated in 1833 in a humor piece about the fictional Major Jack Downing, written by Seba Smith. The word is thought to be a colloquial alteration of sumptuous. The original sumptuous describes something very expensive, of choice materials and fine work. Scrumptious, on the other hand, means "very pleasing, especially to the senses; delectable; splendid." So, it does not refer so much to the expense of what it describes. From Rudyard Kipling: "Whew! What a place! …" said Stalky, filling himself a pipe. "Isn't it scrumptious? …"

So, scrumptious is another way to say awesome!

Photo Credits:

Sea Otters - Wikimedia Commons

Knighting a penguin - Edinburgh Zoo

Macaques with snowballs - Weird Science vis Twitter

Nemo - Sticker image on Amazon product page

Clownfish #1 - GreatBarrierReefs.com

Saddleback clownfish - FishKeepingForever.com

Tomato clownfish - BuildYourAquarium.com

Clarkii clownfish - BuildYourAquarium.com

She said, "Nemo!"

I had to agree. Nemo is a very positive fish. The little guy never gives up and never loses faith. So, for that simple reason, the clownfish is today's Awesome Animal!

What the heck is a Clownfish?

The clownfish, also called the anemonefish, includes about thirty species of fish that form an amazing symbiotic relationship with sea anemones. They are brightly colored, often with various patterns of orange, black, and white.

Clownfish live mostly in coral reefs and shallow lagoons in the Indian and Pacific oceans. Nemo lives near Sydney, Australia, remember?

Amazing facts about Clownfish

Let's talk about this strange relationship between clownfish and anemones.

First a few definitions. Symbiosis is when two living things develop a close, long-term biological relationship with each other. There are three basic types of symbiosis: mutualism, commensalism, and parasitism.

Mutualism is when both organisms benefit. An example is lichens, in which fungi and algae (or sometimes cyanobacteria) live together and benefit from each other.

Commensalism is when one organism benefits, but the other doesn't really care (it isn't helped nor hurt). An example is the remora, a fish that suctions onto a larger fish (like a shark). It gets a free ride and leftover scraps of food, but the larger fish is neither helped nor harmed.

Parasitism is when one organism is benefited while the other is harmed or even killed. A well-known example is the tapeworm, which lives in the intestines of larger animals, stealing the larger animal's ingested food and often weakening the animal (called the host).

In my Diffusion series, humans and tree kangaroos form a symbiotic, mutualistic relationship, in which... well, you'll just have to read the series if you want to know more about that (you'll be glad you did).

Okay, back to the clownfish. Most clownfish species only form relationships with specific species of anemones. In fact, there are over 1,000 species of anemones, but only ten of those species can coexist with clownfish.

This is an example of mutualistic symbiosis. So, both animals benefit.

What does the clownfish get out of this? First, the sea anemone provides protection from predators. Sea anemone tentacles are poisonous and can sting and kill other fish. Second, the clownfish gets to eat scraps of fish left over from the anemone's meals, as well as anemone excrement and the occasional tentacle that breaks off. Third, the clownfish can raise its young in the safety of the tentacles.

What does the anemone get out of this deal? First, the clownfish defends the anemone from parasites and predators. Second, when the clownfish poops on the anemone, the nitrogen from this poop increases the amount of algae growing in the anemone's tissue. Third, if you watch a clownfish, you'll see that it constantly moves around among the anemone's tentacles. This movement helps circulate water around the anemone, increasing the anemone's oxygen intake.

Wow, how awesome is that relationship? Everybody wins! Well, except the prey fish that get attracted to the anemone's deadly stingers.

Below are two saddleback clownfish. Notice the juveniles beneath the anemone—we're going to talk about those in a moment.

Why do clownfish have such bright colors? One idea is that the bright colors attract small fish to the anemone, which are then killed by the anemone's stingers and consumed by the anemone.

Here's a good question... why don't the anemone's stingers harm or kill the clownfish? A layer of mucus on the clownfish's body protects it from the stings. When a clownfish decides to live with a new anemone, it does an elaborate "dance" among the anemone's tentacles. It swims about, touching the tentacles with different parts of its body, until the anemone becomes acclimated to its body.

It's worth pointing out that the fish's mucus is made up mostly of sugars instead of proteins, so it's possible the anemone may not recognize the fish as prey and therefore does not sting.

It's also worth pointing out that clownfish are not really immune to the anemone's stings. Studies have shown that, if the mucus is removed, the anemones can kill the clownfish. So, it's all about the mucus!

Check out this video about the clownfish/anemone relationship.

Below is a tomato clownfish.

Clownfish usually live in groups with an anemone, and the social structure is rather bizarre. We'll call the group of fish a colony. Each colony includes a breeding pair and then several additional, younger, non-dominant males. The breeding female is the boss, and she gets to live in the best room in the house, the top of the anemone. That's where the most food is (and I suppose it also has the best view).

Now here's where things get kind of weird. All clownfish are born as males. Yep, all of them. When something happens to the breeding female in a colony (the boss)—if she dies, for example—the breeding male switches sexes and becomes the breeding female (that was not a typo). The largest of the juvenile males then experiences a rapid spurt of growth and quickly develops into the breeding male.

Here's a good question... There's one breeding male, right? That male is the boss of the other males (but not of the female). Since that male likes being the one male lucky enough to breed with the female, why doesn't he kick all those smaller males out of the colony so that he doesn't have to worry about them sneaking upstairs and breeding with the female?

Here's the simplified answer. The smaller males modify their growth rate, purposely remaining small and submissive so that they are not a threat to the boss male. That way they get to stay in the colony, hoping to someday have the chance to become the boss male when the breeding female dies.

See? Clownfish are POSITIVE fish—always hopeful!

Below is a Clarkii clownfish.

Clownfish are wildly popular among aquarium enthusiasts. In fact, most of those you see in pet shops are bred in captivity rather than caught in the wild (Nemo would like that—he was caught in the wild). Selective breeding has resulted in a wide variety of "designer clownfish," with amazing colors and patterns. Below I put together several striking examples into one image.

So, the Clownfish deserves a place in the S.A.H.O.F.

(Scrumptious Animal Hall of Fame).

FUN FACT: The word scrumptious originated in 1833 in a humor piece about the fictional Major Jack Downing, written by Seba Smith. The word is thought to be a colloquial alteration of sumptuous. The original sumptuous describes something very expensive, of choice materials and fine work. Scrumptious, on the other hand, means "very pleasing, especially to the senses; delectable; splendid." So, it does not refer so much to the expense of what it describes. From Rudyard Kipling: "Whew! What a place! …" said Stalky, filling himself a pipe. "Isn't it scrumptious? …"

So, scrumptious is another way to say awesome!

Photo Credits:

Sea Otters - Wikimedia Commons

Knighting a penguin - Edinburgh Zoo

Macaques with snowballs - Weird Science vis Twitter

Nemo - Sticker image on Amazon product page

Clownfish #1 - GreatBarrierReefs.com

Saddleback clownfish - FishKeepingForever.com

Tomato clownfish - BuildYourAquarium.com

Clarkii clownfish - BuildYourAquarium.com

Published on April 02, 2020 10:53

March 21, 2020

Awesome Animal - Arapaima

Hmm... have I featured a fish before? I don't think so. For the first fish featured as an Awesome Animal, I decided to use one most people probably haven't heard of before.

The Arapaima is unique because it is the largest fish living in freshwater. Another cool feature—it not only can breathe in water, like most fish, but it is also capable of breathing air!

What the heck is an Arapaima?

The arapaima, sometimes also called pirarucu or paiche, is a freshwater fish that lives in the rainforest rivers, swamps, and lakes of the Amazon basin of South America.

There are several species—up to five—but scientists do not all agree on this, and two of the species are so rare that their existence is questionable.

Amazing facts about the Arapaima

The arapaima is a big fish. They can grow over 15 feet (4.5 m) long and weigh up to 440 pounds (200 kg). There are plenty of ocean fish that get this large, but the arapaima is the largest fish that lives exclusively in freshwater.

Unfortunately, since the arapaima is an important food fish for local fishermen, they have been overfished, and their average size is now smaller, more like 7 feet (2.1 m) and 200 pounds (90 kg).

Arapaimas have extremely large scales. Each scale can be 2.4 inches (6 cm) across. As you can see from the photo above, the scales near the tail are often bright red. In fact, the name pirarucu comes from the Tupi language, and the word translates roughly to “red fish.”

Speaking of their scales, these large plates have evolved to be piranha proof! Since the arapaima lives in the same waters as piranhas, this is useful don't you think? The large, tough scales are made of mineralized collagen, making them extremely hard. Not only that, but the scales' corrugated shape makes them flexible so they don't break when piranhas bite.

Below are some kids feeding arapaima fish at a park.

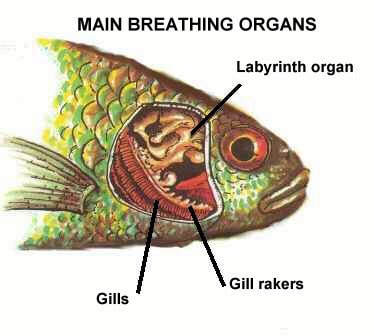

Arapaimas can breathe air. You are probably familiar with the popular pet shop fish sometimes called the Siamese fighting fish (Betta splendens). It is a tiny fish that can live in a very small aquarium without oxygenated water. How does it breathe without much oxygen in the water? The betta fish has an organ called the labyrinth organ, and so does the arapaima.

The labyrinth organ is actually an extension of the gill plates (bone that anchors the gills) and is made of many folds of bone. Tiny blood vessels cover these folds and absorb oxygen from the air, kind of like lungs absorb air.

This ability to breathe air allows the arapaima to survive during the low water season when bodies of water become isolated and stagnant. This fish can survive in water with almost no dissolved oxygen (as low as 0.5 ppm).

Here's another benefit for this fish for having a labyrinth organ. During the low water season, other fish struggle to get enough oxygen from the water, and they become very slow and lethargic. Can you guess what arapaimas eat? Yep, other fish. So, they can gulp the air they need and then cruise around, sucking up all the lethargic fish. Like fish in a barrel, as they say.

When an arapaima takes a big gulp of air, it can then stay under water for 10 to 20 minutes before surfacing for another gulp. As you can imagine, they make a loud gulping sound when they do this.

Although arapaimas rarely attack humans, these fish have a habit of leaping out of the water when startled. This sometimes results in the massive fish capsizing the small boats that startle them. So, I suppose in that respect they could be considered dangerous.

Check out this video of a fisherman catching an arapaima.

Because arapaimas must come to the surface to breathe, they are fairly easy for fishermen to catch. The local fishermen often paddle around in their homemade canoes and skewer the fish with harpoons. See the fisherman below with his catch.

Unfortunately, arapaimas have been heavily overfished, and they have become extinct in some areas of their range. In other areas, their numbers are dwindling fast. Here's the good news, though. In areas where the government is actively regulating arapaima fishing (setting limits, seasons, etc.), these fish are actually thriving. Yay!!! In my opinion, it is a real tragedy when any species goes extinct, particularly when it is a result of human activity.

So, the Arapaime deserves a place in the S.A.H.O.F.

(Sterling Animal Hall of Fame).

FUN FACT: The word sterling, of course, refers to British money and to sterling silver (or things made of sterling silver). The word originated in about 1300, probably from the Middle English word sterre (meaning star), from the stars that were pressed onto certain Norman coins. In the mid 1500s, the word was broadened to refer to "money having the quality of sterling." Then in 1600 it was broadened again to refer to "English money in general." A pound sterling originally meant a pound of sterlings, which was about 240 sterlings. At some point, the word began referring to "capable of standing to a test" (as a a good quality coin would). Then, finally, people started to use the term as an adjective to mean "genuine and reliable" or "first class." For example, of sterling character, or a sterling record of achievement.

So, sterling is another way to say awesome!

Photo Credits:

Tree chewed by beaver - Trish Smith

Beaver chewing tree - AnimatedFX on Flickr

Arapaima #1 - Tennessee Aquarium

Children feeding arapaima - Pinterest

Diagram of Labyrinth organ - My Aquarium Club

Fisherman carrying arapaima - Sergio Ricardo de Oliveira via NBC News

Fishermen with two arapaima - Leandro Castello via LiveScience

The Arapaima is unique because it is the largest fish living in freshwater. Another cool feature—it not only can breathe in water, like most fish, but it is also capable of breathing air!

What the heck is an Arapaima?

The arapaima, sometimes also called pirarucu or paiche, is a freshwater fish that lives in the rainforest rivers, swamps, and lakes of the Amazon basin of South America.

There are several species—up to five—but scientists do not all agree on this, and two of the species are so rare that their existence is questionable.

Amazing facts about the Arapaima

The arapaima is a big fish. They can grow over 15 feet (4.5 m) long and weigh up to 440 pounds (200 kg). There are plenty of ocean fish that get this large, but the arapaima is the largest fish that lives exclusively in freshwater.

Unfortunately, since the arapaima is an important food fish for local fishermen, they have been overfished, and their average size is now smaller, more like 7 feet (2.1 m) and 200 pounds (90 kg).

Arapaimas have extremely large scales. Each scale can be 2.4 inches (6 cm) across. As you can see from the photo above, the scales near the tail are often bright red. In fact, the name pirarucu comes from the Tupi language, and the word translates roughly to “red fish.”

Speaking of their scales, these large plates have evolved to be piranha proof! Since the arapaima lives in the same waters as piranhas, this is useful don't you think? The large, tough scales are made of mineralized collagen, making them extremely hard. Not only that, but the scales' corrugated shape makes them flexible so they don't break when piranhas bite.

Below are some kids feeding arapaima fish at a park.

Arapaimas can breathe air. You are probably familiar with the popular pet shop fish sometimes called the Siamese fighting fish (Betta splendens). It is a tiny fish that can live in a very small aquarium without oxygenated water. How does it breathe without much oxygen in the water? The betta fish has an organ called the labyrinth organ, and so does the arapaima.

The labyrinth organ is actually an extension of the gill plates (bone that anchors the gills) and is made of many folds of bone. Tiny blood vessels cover these folds and absorb oxygen from the air, kind of like lungs absorb air.

This ability to breathe air allows the arapaima to survive during the low water season when bodies of water become isolated and stagnant. This fish can survive in water with almost no dissolved oxygen (as low as 0.5 ppm).

Here's another benefit for this fish for having a labyrinth organ. During the low water season, other fish struggle to get enough oxygen from the water, and they become very slow and lethargic. Can you guess what arapaimas eat? Yep, other fish. So, they can gulp the air they need and then cruise around, sucking up all the lethargic fish. Like fish in a barrel, as they say.

When an arapaima takes a big gulp of air, it can then stay under water for 10 to 20 minutes before surfacing for another gulp. As you can imagine, they make a loud gulping sound when they do this.

Although arapaimas rarely attack humans, these fish have a habit of leaping out of the water when startled. This sometimes results in the massive fish capsizing the small boats that startle them. So, I suppose in that respect they could be considered dangerous.

Check out this video of a fisherman catching an arapaima.

Because arapaimas must come to the surface to breathe, they are fairly easy for fishermen to catch. The local fishermen often paddle around in their homemade canoes and skewer the fish with harpoons. See the fisherman below with his catch.

Unfortunately, arapaimas have been heavily overfished, and they have become extinct in some areas of their range. In other areas, their numbers are dwindling fast. Here's the good news, though. In areas where the government is actively regulating arapaima fishing (setting limits, seasons, etc.), these fish are actually thriving. Yay!!! In my opinion, it is a real tragedy when any species goes extinct, particularly when it is a result of human activity.

So, the Arapaime deserves a place in the S.A.H.O.F.

(Sterling Animal Hall of Fame).

FUN FACT: The word sterling, of course, refers to British money and to sterling silver (or things made of sterling silver). The word originated in about 1300, probably from the Middle English word sterre (meaning star), from the stars that were pressed onto certain Norman coins. In the mid 1500s, the word was broadened to refer to "money having the quality of sterling." Then in 1600 it was broadened again to refer to "English money in general." A pound sterling originally meant a pound of sterlings, which was about 240 sterlings. At some point, the word began referring to "capable of standing to a test" (as a a good quality coin would). Then, finally, people started to use the term as an adjective to mean "genuine and reliable" or "first class." For example, of sterling character, or a sterling record of achievement.

So, sterling is another way to say awesome!

Photo Credits:

Tree chewed by beaver - Trish Smith

Beaver chewing tree - AnimatedFX on Flickr

Arapaima #1 - Tennessee Aquarium

Children feeding arapaima - Pinterest

Diagram of Labyrinth organ - My Aquarium Club

Fisherman carrying arapaima - Sergio Ricardo de Oliveira via NBC News

Fishermen with two arapaima - Leandro Castello via LiveScience

Published on March 21, 2020 09:04

March 11, 2020

Awesome Animal - Babirusa

Sometimes I see a particular animal, and I think, Whoa... that's so weird it's awesome! The Babirusa is just such an animal. It's a pig, but it's very different from all other types of pigs. In fact, it makes me think of some of those long-extinct mammals from prehistoric times.

What the heck is a Babirusa?

Basically, this creature is a pig, but babirusas branched off from the other groups of pigs long ago. They've been separated from the other pigs for somewhere between 10 and 20 million years!

Babirusas grow to about 3.7 feet (1.1 m) long and about 220 pounds (100 kg). The four species of babirusas are found on a few islands in Indonesia, Specifically, the islands of Sulawesi, Togian, Sula, and Buru. Don't those exotic names make you want to go visit these islands?

One of the most astounding things about babirusas is their teeth. I'm not kidding—they have some seriously impressive teeth. Or messed-up teeth, depending on how you look at it.

Amazing facts about Babirusas

Before we talk about the teeth, let's further consider what these creatures really are. As I said above, these creatures are classified in the pig family (Suidae), but they are quite different from other pigs. For example, unlike other pigs, babirusas have complex, two-chambered stomachs, kind of like those of sheep and other ruminant mammals.

Also, babirusas do not have the stiff rostral bone in their snouts like other pigs do. So, their snouts are much softer, and they cannot dig with their snouts except in soft mud.

Babirusas are also called deer-pigs. It is thought that the people of Sulawesi came up with the name babirusa (in Malay, babi = pig, rusa = deer) because the creature's long tusks reminded them of the antlers of deer. But it is also possible that the name comes from the creature's unusually thin legs (for a pig).

Babirusas live in swampy rainforest areas along river banks. They are not picky eaters, and will eat just about anything. They like leaves, fruits, berries, nuts, mushrooms, bark, insects, fish, and small mammals. They are even known to eat smaller babirusas. As I said above, they can't dig with their snouts, but they use their specialized hooves to dig for insect larvae and roots in the ground.

Like many pigs, babirusas are fond of mud. The mud helps them keep parasites off their bodies.

Okay, let's talk about those crazy teeth, which are long enough that they are often called tusks. Both the males and the females have the lower tusks, which can be pretty impressive. They overlap the edge of the creature's snout as they grow upward (there just isn't room inside the mouth!). Even more impressive, though, are the upper tusks, which only the males have.

The first thing to point out is that babirusa teeth never stop growing. As long as the animal is alive, the teeth keep growing larger and longer. The upper tusks start out by growing downward, but then they quickly curve around and start growing upward. Astoundingly, they grow right through the top of the snout.

Then these amazing teeth just keep growing. If they don't break off, or if the males do not grind them down against a hard surface, the tusks will curve all the way back and touch the creature's forehead, Although it is rare, sometimes they will even grow right through the skull into the animal's brain. Yikes!

The question is, what is the purpose of such extreme teeth? The answer... we don't know for sure. Originally, and understandably, it was thought that the lower tusks were used by males when they would fight for mates, and the upper tusks protected their eyes during these altercations. Sounds reasonable, right? Sure, until you actually observe male babirusas fighting (which they do often). When they fight, they stand up on their hind legs and box, holding their heads high to protect their tusks, which are actually brittle and are not built to withstand much pressure

Check out this video about Babirusas and their teeth.

So, what are the teeth for? Well, there is a popular story told by locals where babirusas live, which says that the males use them to hang from trees to wait quietly until a female passes by. Umm... I think we can safely rule that idea out as being a whimsical story, right? (although I like the mental image of these creatures hanging around in the rainforest).

Probably, the most likely purpose of the teeth is to impress females (kind of like the tail display of a male peacock). The longer the tusks, the more attractive a male is to the females. However, we won't really know this for sure until extensive studies show it to be true.

Compared to the bizarre appearance of the males, female babirusas look more like other types of pigs. The babies are just as cute as any pig babies (in my opinion).

So, the Babirusa deserves a place in the P.B.A.H.O.F.

(Pure Barry Animal Hall of Fame).

FUN FACT: The phrase pure barry is distinctly Scottish in origin, used primarily in Edinburgh, and its first recorded use was in 1923. The Scottish National Dictionary defines the term to mean: “fine; smart; used to describe something very good of its type.” Example of use: "That Bridgers 1 book is pure barry, mate. Pure barry, that book." So, pure barry is another way to say awesome!

(Thanks to reader Ed Hohmann for telling me about pure barry.)

Photo Credits:

Animal tracks - Stan C. Smith

Sidewinder tracks - HeyPugshund via Tumblr

Fictional woman - https://www.thispersondoesnotexist.com

Babirusa #1 - Dunnock_D licensed CC BY-NC 2.0

Babirusa in mud - SmallAnimalPlanet

Babirusa skull - UNCL Museums and Collections

Female babirusa with piglets - San Diego Zoo

What the heck is a Babirusa?

Basically, this creature is a pig, but babirusas branched off from the other groups of pigs long ago. They've been separated from the other pigs for somewhere between 10 and 20 million years!

Babirusas grow to about 3.7 feet (1.1 m) long and about 220 pounds (100 kg). The four species of babirusas are found on a few islands in Indonesia, Specifically, the islands of Sulawesi, Togian, Sula, and Buru. Don't those exotic names make you want to go visit these islands?

One of the most astounding things about babirusas is their teeth. I'm not kidding—they have some seriously impressive teeth. Or messed-up teeth, depending on how you look at it.

Amazing facts about Babirusas