Stan C. Smith's Blog, page 29

August 14, 2019

Awesome Animal - Mantis Shrimp

Thanks to reader Daniel Hohlstein for suggesting this creature.

Usually when we think of shrimp, we think, Yum... boiled or fried? But did you know that there are at least 3,000 species of crustaceans that are considered shrimp? As a group, they are extremely variable. But the prize for the most colorful has to go to the mantis shrimp (which, oddly enough, isn't actually a true shrimp).

But their colors are not the most impressive thing about mantis shrimp. If you are ready to be amazed, read on.

What the heck is a Mantis Shrimp?

You know what arthropods are, right? Arthropoda is a phylum of animals that includes pretty much all the invertebrates that have an exoskeleton (insects, crabs, spiders, centipedes, scorpions, isopods, and many more). In Bridgers 4, Infinity and Desmond are stranded on a world filled with amazing arthropods.

Within the arthropod phylum, we have the subphylum of crustaceans (crabs, shrimp, lobsters, crayfish, isopods, barnacles, and more). And then within the crustaceans we have an order called Stomatopoda. The stomatopods include about 450 species of mantis shrimp.

Perhaps the most striking thing about mantis shrimp is that they are deadly predators. Fierce, wicked, dangerous, clobbering predators, capable of smashing their prey to smithereens.

Amazing facts about Mantis Shrimp

Before we discuss the predator behavior of mantis shrimp, let's talk about their colors. Why do mantis shrimp have such amazing colors? It probably has something to do with the fact that they have amazing EYES. It's true. Mantis shrimp are considered to have the most impressive and complex eyes of the entire animal kingdom.

Perhaps you think I'm exaggerating, so let's take a look. You know how human eyes have rods and cones, right? Rods are for detecting movement and light levels. Cones are for detecting color. Animals that have lots of rods (like deer) are very good at detecting movement. Animals with lots of cones are good at detecting colors. Humans have pretty good color vision, but we have only three types of cones (dogs, on the other hand, have only two types of cones). Think about how colorful the world looks to us with our three types of cones. Now imagine what it would look like if we suddenly had FIVE types of cones (like some butterflies). We would then see colors that we don't even have words for—colors we've never seen before. Okay, now imagine what the world would look like if we had SIXTEEN different types of color-sensing cones. Because that's how many mantis shrimp have! If a mantis shrimp suddenly had to look through human eyes, it would probably think our vision is pretty darn plain and boring.

When you and I look at a peacock mantis shrimp, here's what we see:

Now try to imagine what another mantis shrimp would see, with its SIXTEEN types of cones. It boggles the mind.

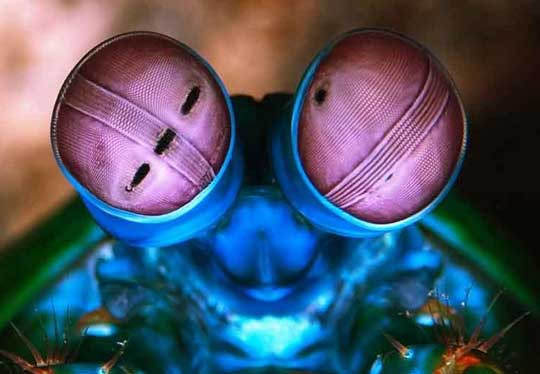

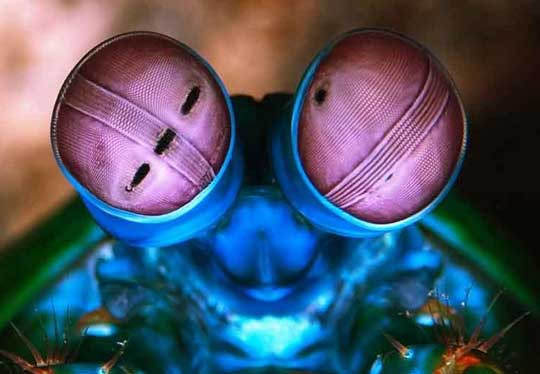

Let's explore these eyes a bit more. The mantis shrimp's eyes are on stalks and can move freely and independently of each other. Each eye is packed with tens of thousands of clusters of cones (photoreceptor cells). And those cells are divided into three regions: the top, the bottom, and a band of special cells across the middle (see photo below). These three regions are different, and mantis shrimp can look at objects with all three regions at the same time, giving them super-duper trinocular vision!

And they can see wavelengths of light we cannot see at all. For example, they can see deep ultraviolet. They can actually detect five different frequency bands in the deep ultraviolet range. And they can see two types of polarized light (linear and circular), an ability that has never been observed in any other animal. We cannot see any of these frequencies, so we can only imagine what things look like to a mantis shrimp.

Consider the three regions in each eye above. Since there are two eyes, that's six regions, each of which can look at an object separately. Humans have two eyes, and with our two eyes we have decent depth perception. But mantis shrimp can look at things with all six regions at once, giving them far better depth perception. Which helps to make them the awesome predators they are.

One more thing about the eyes. Recent studies have shown that mantis shrimp can actually detect cancer. How? Their eyes see polarized light, and polarized light is reflected differently by cancerous cells compared to healthy cells. This is leading to attempts to replicate this ability with cameras that use specialized lenses that can detect polarized light in the same way.

Now let's get back to talking about the mantis shrimp's amazing ability to pulverize the crap out of its prey. These creatures have modified forelimbs, or "clubs." These clubs are highly-specialized, calcified limbs that are generally divided into two categories: those for impaling their prey, and those for smashing their prey.

So, the 450 species of mantis shrimp are divided into smashers and spearers (I'm not kidding). Both of these types have the ability to strike out with unbelievable power. See the two clubs at the bottom of the photo below:

Just how powerful are these clubs (or spears)? Well, you might think I'm exaggerating, but let's take a look. Mantis shrimp strike by rapidly unfolding their clubs. From a standing start, the club instantly reaches a speed of 51 miles per hour (83 km/hr). This requires an acceleration of 10,400 Gs. Think about this: One G is the gravitational force pulled on objects by the Earth's gravity. So right now, sitting in my chair, I am experiencing one G of force (the Earth's gravity is what makes my body weigh 185 pounds when I am sitting still). If I accelerate straight up at 2 Gs, my body would seem to weigh 370 pounds. AND... if I accelerate at 10,400 Gs, my body would seem to weigh nearly 2 million pounds! In other words, I would be smashed into disgusting Stan C. Smith soup.

I repeat, the mantis shrimp accelerates its clubs at 10,400 Gs. Those little clubs accelerate faster than a 22 caliber bullet being fired from a rifle. So when they hit something, they hit it REALLY hard. Not only that, but the rapid acceleration of their clubs causes tiny, superheated, vapor-filled bubbles to form in the surrounding water. These are called cavitation bubbles, and when these bubbles suddenly collapse, this creates another significant force on the prey—enough force to shatter the prey's body. So even if the mantis shrimp misses its prey, the force from the collapsing cavitation bubbles will likely do the job.

And mantis shrimp can strike quickly. They swing out their clubs in less than 800 microseconds. This means that, theoretically, in the time it takes you to blink an eye, these shrimp can punch you 500 times. But it usually only takes a punch or two to do the job.

Check out this video showing the mantis shrimp's smashing ability.

If you could swing your arm with the same force as a mantis shrimp, you could throw a baseball into orbit. Mantis shrimp are not usually kept in glass aquariums because they are capable of shattering the aquarium's glass walls. Mantis shrimp literally bash their prey to bits and then feed on the mess of dismembered legs and body parts. Hmm... I need to figure out how to integrate some kind of giant mantis shrimp into Bridgers 6.

Okay, so here's a good question. If mantis shrimp can punch so hard, how can they do this without breaking their own appendages? Scientists have looked closely at their clubs and it turns out that the outer surface consists of a hard crystalline calcium-phosphate ceramic material. But it's the layers beneath that make all the difference. The clubs have layers of elastic polysaccharide chitin, which act as shock absorbers and prevent the clubs from cracking. This stuff is so impressive that engineers are using the concept to build new types of aircraft panels and body armor.

So, the mantis shrimp deserves a place in the O.A.H.O.F.

(Outasight Animal Hall of Fame).

FUN FACT: The word outasight is obviously a reduction of out-of-sight. Out-of-sight is a slang term that originated in about 1890. Wait! What? I bet you thought it originated as a hippie phrase in the 1960s, right? Along with the related phrase far out. But it's actually much older than this. Here's an excerpt from the 1893 novel, Train Wreckers: "Now if Daisy would only put in an appearance this would be an out of sight chance to pop the question." Of course, the phrase DID become very popular in the 1960s, when it was derived from far out (that Bridgers 5 book is so far out that it's out of sight!), and is usually associated with the experiences of using psychedelic drugs. Either way, the phrase is a perfect fit for the mantis shrimp, don't you think? So, outasight is another way to say awesome!

Photo Credits:

Peacock Mantis Shrimp #1 - George Grall, National Aquarium

Peacock Mantis Shrimp #2 - Imgur

Mantis Shrimp Eyes - Awesci Science Everyday

Mantis Shrimp clubs - Wikimedia Commons via Discover Magazine

Mantis Shrimp #3 - Ian Rosner

Usually when we think of shrimp, we think, Yum... boiled or fried? But did you know that there are at least 3,000 species of crustaceans that are considered shrimp? As a group, they are extremely variable. But the prize for the most colorful has to go to the mantis shrimp (which, oddly enough, isn't actually a true shrimp).

But their colors are not the most impressive thing about mantis shrimp. If you are ready to be amazed, read on.

What the heck is a Mantis Shrimp?

You know what arthropods are, right? Arthropoda is a phylum of animals that includes pretty much all the invertebrates that have an exoskeleton (insects, crabs, spiders, centipedes, scorpions, isopods, and many more). In Bridgers 4, Infinity and Desmond are stranded on a world filled with amazing arthropods.

Within the arthropod phylum, we have the subphylum of crustaceans (crabs, shrimp, lobsters, crayfish, isopods, barnacles, and more). And then within the crustaceans we have an order called Stomatopoda. The stomatopods include about 450 species of mantis shrimp.

Perhaps the most striking thing about mantis shrimp is that they are deadly predators. Fierce, wicked, dangerous, clobbering predators, capable of smashing their prey to smithereens.

Amazing facts about Mantis Shrimp

Before we discuss the predator behavior of mantis shrimp, let's talk about their colors. Why do mantis shrimp have such amazing colors? It probably has something to do with the fact that they have amazing EYES. It's true. Mantis shrimp are considered to have the most impressive and complex eyes of the entire animal kingdom.

Perhaps you think I'm exaggerating, so let's take a look. You know how human eyes have rods and cones, right? Rods are for detecting movement and light levels. Cones are for detecting color. Animals that have lots of rods (like deer) are very good at detecting movement. Animals with lots of cones are good at detecting colors. Humans have pretty good color vision, but we have only three types of cones (dogs, on the other hand, have only two types of cones). Think about how colorful the world looks to us with our three types of cones. Now imagine what it would look like if we suddenly had FIVE types of cones (like some butterflies). We would then see colors that we don't even have words for—colors we've never seen before. Okay, now imagine what the world would look like if we had SIXTEEN different types of color-sensing cones. Because that's how many mantis shrimp have! If a mantis shrimp suddenly had to look through human eyes, it would probably think our vision is pretty darn plain and boring.

When you and I look at a peacock mantis shrimp, here's what we see:

Now try to imagine what another mantis shrimp would see, with its SIXTEEN types of cones. It boggles the mind.

Let's explore these eyes a bit more. The mantis shrimp's eyes are on stalks and can move freely and independently of each other. Each eye is packed with tens of thousands of clusters of cones (photoreceptor cells). And those cells are divided into three regions: the top, the bottom, and a band of special cells across the middle (see photo below). These three regions are different, and mantis shrimp can look at objects with all three regions at the same time, giving them super-duper trinocular vision!

And they can see wavelengths of light we cannot see at all. For example, they can see deep ultraviolet. They can actually detect five different frequency bands in the deep ultraviolet range. And they can see two types of polarized light (linear and circular), an ability that has never been observed in any other animal. We cannot see any of these frequencies, so we can only imagine what things look like to a mantis shrimp.

Consider the three regions in each eye above. Since there are two eyes, that's six regions, each of which can look at an object separately. Humans have two eyes, and with our two eyes we have decent depth perception. But mantis shrimp can look at things with all six regions at once, giving them far better depth perception. Which helps to make them the awesome predators they are.

One more thing about the eyes. Recent studies have shown that mantis shrimp can actually detect cancer. How? Their eyes see polarized light, and polarized light is reflected differently by cancerous cells compared to healthy cells. This is leading to attempts to replicate this ability with cameras that use specialized lenses that can detect polarized light in the same way.

Now let's get back to talking about the mantis shrimp's amazing ability to pulverize the crap out of its prey. These creatures have modified forelimbs, or "clubs." These clubs are highly-specialized, calcified limbs that are generally divided into two categories: those for impaling their prey, and those for smashing their prey.

So, the 450 species of mantis shrimp are divided into smashers and spearers (I'm not kidding). Both of these types have the ability to strike out with unbelievable power. See the two clubs at the bottom of the photo below:

Just how powerful are these clubs (or spears)? Well, you might think I'm exaggerating, but let's take a look. Mantis shrimp strike by rapidly unfolding their clubs. From a standing start, the club instantly reaches a speed of 51 miles per hour (83 km/hr). This requires an acceleration of 10,400 Gs. Think about this: One G is the gravitational force pulled on objects by the Earth's gravity. So right now, sitting in my chair, I am experiencing one G of force (the Earth's gravity is what makes my body weigh 185 pounds when I am sitting still). If I accelerate straight up at 2 Gs, my body would seem to weigh 370 pounds. AND... if I accelerate at 10,400 Gs, my body would seem to weigh nearly 2 million pounds! In other words, I would be smashed into disgusting Stan C. Smith soup.

I repeat, the mantis shrimp accelerates its clubs at 10,400 Gs. Those little clubs accelerate faster than a 22 caliber bullet being fired from a rifle. So when they hit something, they hit it REALLY hard. Not only that, but the rapid acceleration of their clubs causes tiny, superheated, vapor-filled bubbles to form in the surrounding water. These are called cavitation bubbles, and when these bubbles suddenly collapse, this creates another significant force on the prey—enough force to shatter the prey's body. So even if the mantis shrimp misses its prey, the force from the collapsing cavitation bubbles will likely do the job.

And mantis shrimp can strike quickly. They swing out their clubs in less than 800 microseconds. This means that, theoretically, in the time it takes you to blink an eye, these shrimp can punch you 500 times. But it usually only takes a punch or two to do the job.

Check out this video showing the mantis shrimp's smashing ability.

If you could swing your arm with the same force as a mantis shrimp, you could throw a baseball into orbit. Mantis shrimp are not usually kept in glass aquariums because they are capable of shattering the aquarium's glass walls. Mantis shrimp literally bash their prey to bits and then feed on the mess of dismembered legs and body parts. Hmm... I need to figure out how to integrate some kind of giant mantis shrimp into Bridgers 6.

Okay, so here's a good question. If mantis shrimp can punch so hard, how can they do this without breaking their own appendages? Scientists have looked closely at their clubs and it turns out that the outer surface consists of a hard crystalline calcium-phosphate ceramic material. But it's the layers beneath that make all the difference. The clubs have layers of elastic polysaccharide chitin, which act as shock absorbers and prevent the clubs from cracking. This stuff is so impressive that engineers are using the concept to build new types of aircraft panels and body armor.

So, the mantis shrimp deserves a place in the O.A.H.O.F.

(Outasight Animal Hall of Fame).

FUN FACT: The word outasight is obviously a reduction of out-of-sight. Out-of-sight is a slang term that originated in about 1890. Wait! What? I bet you thought it originated as a hippie phrase in the 1960s, right? Along with the related phrase far out. But it's actually much older than this. Here's an excerpt from the 1893 novel, Train Wreckers: "Now if Daisy would only put in an appearance this would be an out of sight chance to pop the question." Of course, the phrase DID become very popular in the 1960s, when it was derived from far out (that Bridgers 5 book is so far out that it's out of sight!), and is usually associated with the experiences of using psychedelic drugs. Either way, the phrase is a perfect fit for the mantis shrimp, don't you think? So, outasight is another way to say awesome!

Photo Credits:

Peacock Mantis Shrimp #1 - George Grall, National Aquarium

Peacock Mantis Shrimp #2 - Imgur

Mantis Shrimp Eyes - Awesci Science Everyday

Mantis Shrimp clubs - Wikimedia Commons via Discover Magazine

Mantis Shrimp #3 - Ian Rosner

Published on August 14, 2019 06:12

July 27, 2019

Awesome Animal - Mouse Deer

Thanks to reader Debbi Dieter for suggesting this creature.

In the United States, there are only two species of deer (white-tailed deer and mule deer), which typically grow to 200 to 300 pounds (90-136 kg). However, we have a few other ungulates (hoofed animals that walk on the tips of their toes), such as elk, moose, bison, mountain goats, and others (yes, I know elk and moose are technically deer). Some of these other ungulates, like the moose, can grow to 1,500 pounds (680 kg). And when we consider ungulates from other parts of the world, some of them, like the white rhinoceros, can weigh up to 9,900 pounds (4,500 kg).

In other words, ungulates are generally BIG animals.

So, what's the smallest of all the ungulates? It turns out to be the mouse deer, also known as the Chevrotain.

What the heck is a Chevrotain?

Chevrotains are small ungulates that live in the forests of South and Southeast Asia (and one of the species lives in Africa). The smallest of these, the Java mouse deer, is the size of a rabbit, usually weighing only 2.2 to 4.4 pounds (1-2 kg).

Mouse deer are not actually true deer (although they are ungulates). They belong to the family, Tragulidae. There are a number of extinct species in this family, and the ten species alive today are all that's left of this ancient group.

Amazing facts about Chevrotains

Mouse deer are in an old family. This group of mammals originated about 34 million years ago, and they haven't changed much since then.

They are considered primitive ruminants. Ruminants are mammals that get their nutrients from plants by having the consumed plant material ferment (with the help of microbes) in specialized stomach compartments before going into the rest of the digestive system. Chevrotains have four stomach chambers for this, but the third chamber is poorly developed compared to that of more modern ruminants. Chevrotains are thought to be a stepping stone between ungulates with simple stomachs (like pigs) and ungulates with highly-evolved four-chambered stomachs (like true deer and cows).

Mouse deer do not have antlers or horns. But they do have something unusual—elongated teeth, or tusks.

Why does a tiny little ungulate have tusks? Well, only the males have these tusks, and they use them when they fight each other. Why do they fight each other? To compete for mates, of course. This is the same reason many other ungulate males fight. The male deer that live around our house get into these nasty shoving matches using their pointed antlers. Bighorn sheep males charge at each other and smash their brains out (not literally) in a head-on collision. And the little chevrotain males slash at each other with their sharp tusks. It's all about being dominant. Good thing humans aren't like that, right? Hmm...

Chevrotains have extremely thin legs and feet. With those tiny legs, they can't turn very quickly, but the legs do help them run through the thick brush of their forest habitat.

Chevrotains have mysterious blood. First of all, they have the smallest red blood cells of any mammal. As far I can tell, no one knows why their cells are so small. Not only that, but about 13% of their red blood cells have little pits in the cell surface. These pits have never been observed in the blood cells of any other animal, and we simply do not know what function they serve. See the pits in electron microscope image below. Also note that the red blood cells are almost round (spherical), which is another unusual characteristic. Weird.

After a very long gestation period of 7 to 9 months, chevrotain females give birth to only one young. But... they usually mate again within an hour or two after giving birth. And they continue to do that throughout their adult life, breeding and giving birth all year round. Wow, that means the females are pregnant almost their entire lives!

The young are very well-developed when they are born, and within 30 minutes they can stand and run around at full speed.

Now this little tidbit of information is particularly unusual for an ungulate. Several species of chevrotains are water lovers. In fact, the species that lives in Africa is called the water chevrotain. This creature will dive into the water whenever it senses a predator is near. They sink to the bottom and actually walk along the stream bed. To keep the current from carrying them away, they scrunch down to reduce the water resistance, and they also grab hold of submerged plants. They can stay under water this way for four minutes! Then they slowly move to the edge of the stream and discretely raise their nose up and take another breath, thus avoiding the predator until it gets bored with waiting and goes off in search of easier prey.

Check out this video of a water chevrotain avoiding an eagle.

One more interesting fact. Another way that the chevrotain responds to danger is to stomp its feet (actually, large species of deer do this, too). Chevrotains can stomp four to seven times per second, creating a "drum-roll" sound to warn other chevrotains in the area that a predator is near.

So, the chevrotain deserves a place in the F.A.H.O.F.

(Fabulicious Animal Hall of Fame).

FUN FACT: Well, the word fabulicious is obviously a combination of fabulous and delicious. The word fabulous originated way back in about 1540, and it has roots in the word fable. In other words, it referred to something too amazing to be true. And the word delicious originated even earlier, about 1250, and it meant very pleasing or delightful (especially in smell or taste). At some point, some brilliant person decided these two words belonged together, and thus fabulicious was born. So, fabulicious is another way to say awesome! Photo Credits:

Mouse Deer #1 - The Washington Post

Mouse deer tusk - Arjan Haverkamp via Flickr

Mouse deer blood cells - K. Fukuta, H. Kudo and S. Jalaludin, Journal of Anatomy

Mouse deer with baby - ZooBorns

Mouse deer stomping feet - ZooBorns

In the United States, there are only two species of deer (white-tailed deer and mule deer), which typically grow to 200 to 300 pounds (90-136 kg). However, we have a few other ungulates (hoofed animals that walk on the tips of their toes), such as elk, moose, bison, mountain goats, and others (yes, I know elk and moose are technically deer). Some of these other ungulates, like the moose, can grow to 1,500 pounds (680 kg). And when we consider ungulates from other parts of the world, some of them, like the white rhinoceros, can weigh up to 9,900 pounds (4,500 kg).

In other words, ungulates are generally BIG animals.

So, what's the smallest of all the ungulates? It turns out to be the mouse deer, also known as the Chevrotain.

What the heck is a Chevrotain?

Chevrotains are small ungulates that live in the forests of South and Southeast Asia (and one of the species lives in Africa). The smallest of these, the Java mouse deer, is the size of a rabbit, usually weighing only 2.2 to 4.4 pounds (1-2 kg).

Mouse deer are not actually true deer (although they are ungulates). They belong to the family, Tragulidae. There are a number of extinct species in this family, and the ten species alive today are all that's left of this ancient group.

Amazing facts about Chevrotains

Mouse deer are in an old family. This group of mammals originated about 34 million years ago, and they haven't changed much since then.

They are considered primitive ruminants. Ruminants are mammals that get their nutrients from plants by having the consumed plant material ferment (with the help of microbes) in specialized stomach compartments before going into the rest of the digestive system. Chevrotains have four stomach chambers for this, but the third chamber is poorly developed compared to that of more modern ruminants. Chevrotains are thought to be a stepping stone between ungulates with simple stomachs (like pigs) and ungulates with highly-evolved four-chambered stomachs (like true deer and cows).

Mouse deer do not have antlers or horns. But they do have something unusual—elongated teeth, or tusks.

Why does a tiny little ungulate have tusks? Well, only the males have these tusks, and they use them when they fight each other. Why do they fight each other? To compete for mates, of course. This is the same reason many other ungulate males fight. The male deer that live around our house get into these nasty shoving matches using their pointed antlers. Bighorn sheep males charge at each other and smash their brains out (not literally) in a head-on collision. And the little chevrotain males slash at each other with their sharp tusks. It's all about being dominant. Good thing humans aren't like that, right? Hmm...

Chevrotains have extremely thin legs and feet. With those tiny legs, they can't turn very quickly, but the legs do help them run through the thick brush of their forest habitat.

Chevrotains have mysterious blood. First of all, they have the smallest red blood cells of any mammal. As far I can tell, no one knows why their cells are so small. Not only that, but about 13% of their red blood cells have little pits in the cell surface. These pits have never been observed in the blood cells of any other animal, and we simply do not know what function they serve. See the pits in electron microscope image below. Also note that the red blood cells are almost round (spherical), which is another unusual characteristic. Weird.

After a very long gestation period of 7 to 9 months, chevrotain females give birth to only one young. But... they usually mate again within an hour or two after giving birth. And they continue to do that throughout their adult life, breeding and giving birth all year round. Wow, that means the females are pregnant almost their entire lives!

The young are very well-developed when they are born, and within 30 minutes they can stand and run around at full speed.

Now this little tidbit of information is particularly unusual for an ungulate. Several species of chevrotains are water lovers. In fact, the species that lives in Africa is called the water chevrotain. This creature will dive into the water whenever it senses a predator is near. They sink to the bottom and actually walk along the stream bed. To keep the current from carrying them away, they scrunch down to reduce the water resistance, and they also grab hold of submerged plants. They can stay under water this way for four minutes! Then they slowly move to the edge of the stream and discretely raise their nose up and take another breath, thus avoiding the predator until it gets bored with waiting and goes off in search of easier prey.

Check out this video of a water chevrotain avoiding an eagle.

One more interesting fact. Another way that the chevrotain responds to danger is to stomp its feet (actually, large species of deer do this, too). Chevrotains can stomp four to seven times per second, creating a "drum-roll" sound to warn other chevrotains in the area that a predator is near.

So, the chevrotain deserves a place in the F.A.H.O.F.

(Fabulicious Animal Hall of Fame).

FUN FACT: Well, the word fabulicious is obviously a combination of fabulous and delicious. The word fabulous originated way back in about 1540, and it has roots in the word fable. In other words, it referred to something too amazing to be true. And the word delicious originated even earlier, about 1250, and it meant very pleasing or delightful (especially in smell or taste). At some point, some brilliant person decided these two words belonged together, and thus fabulicious was born. So, fabulicious is another way to say awesome! Photo Credits:

Mouse Deer #1 - The Washington Post

Mouse deer tusk - Arjan Haverkamp via Flickr

Mouse deer blood cells - K. Fukuta, H. Kudo and S. Jalaludin, Journal of Anatomy

Mouse deer with baby - ZooBorns

Mouse deer stomping feet - ZooBorns

Published on July 27, 2019 09:58

July 18, 2019

Awesome Animal - Kiwi

Did you know the only mammals native to New Zealand are a few species of bats and some marine mammals (whales, dolphins, and seals)? For this reason, the Kiwi is sometimes called New Zealand's "honorary mammal." But the Kiwi, or course, is actually a bird.

Wait! Did you think I was referring to those little brown, fuzzy fruits in the produce section at the market? Nope, those are actually called kiwifruit. And they definitely are not birds.

Wait again! Did you think I was referring to New Zealanders? The people of New Zealand have been referred to as Kiwis since the nickname was given to them during World War I. Again, nope... I'm not talking about the people.

Speaking of New Zealanders, you might think my statement above about the only native mammals being bats and sea mammals is incorrect. After all, humans are certainly mammals, so wouldn't we consider the Maori people to be mammals native to New Zealand? Well, maybe, but the Maori people discovered and settled in New Zealand only 740 years ago (close to the year 1280). That certainly makes them indigenous to the island, but 740 years isn't long compared to the 50 million years since the first kiwis appeared!

What the heck is a Kiwi?

Kiwis consist of five bird species living only on New Zealand. They are in the group of large, flightless birds called ratites, which includes ostriches, emus, cassowaries, rheas, and some species that are now extinct. Kiwis are the smallest (by far) of all the ratites. Perhaps their most distinguishing characteristic is that they are flightless ground birds.

Amazing facts about Kiwis

The genetic heritage of kiwis is confusing. They shared the island of New Zealand with an extinct type of ratites, the 500-pound (227 kg) moa. So, you would think kiwis are closely related to moas. But, DNA evidence has shown that kiwis are more closely related to the elephant birds (also extinct) from Madagascar. And regarding living species, kiwis are more closely related to the emus and cassowaries than to the moas. How can this be possible? Well, studies have shown that the ancestor of kiwis, a bird called Proapteryx, was probably capable of flight, suggesting that kiwi ancestors migrated to New Zealand separate from moas (moas were already large and flightless when the kiwi ancestor arrived on the scene).

Kiwis are about the size of chickens. The largest, the great spotted kiwi, weighs about 7.3 pounds (3.3 kg), and the smallest, the little spotted kiwi, weighs 2.9 pounds (1.3 kg).

I mentioned above that kiwis are sometimes referred to as "honorary mammals." Part of the reason for this is that they appear to be covered in fur, but this is actually thin, hair-like feathers.

Kiwis have really strong legs. Amazingly, a kiwi's muscular legs make up about a third of its entire body weight! With these powerful legs, kiwis can run as fast as a human. In a single night, a kiwi can cover its entire territory, which is often hilly and difficult to traverse. How big is an individual's territory? Up to the size of 60 football fields. That's 79 acres (32 hectares)!

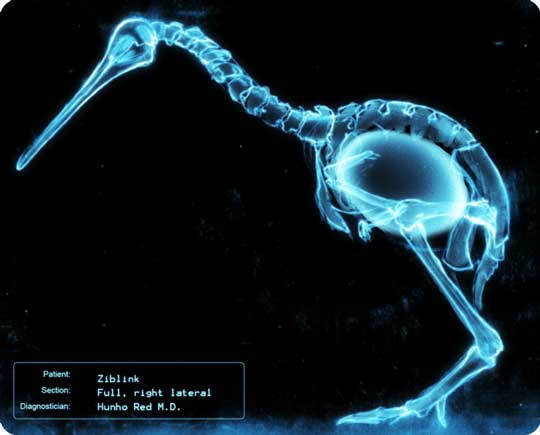

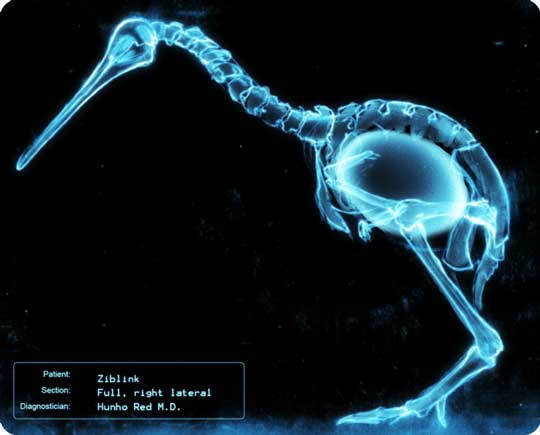

Okay, this may be the most impressive thing about kiwis. These birds typically lay one egg per season, but that one egg is the largest egg (relative to their body size) of any other bird. Consider this... a human baby is typically about 5% of the weight of the mother giving birth. And (drumroll please...) the kiwi's egg can be a whopping 25% of the mother bird's weight. Let's put this into perspective. This would be like a 150-pound (68 kg) woman giving birth to a 37-pound (16.8 kg) baby. Yeeeouch!

Let's look at it another way. A kiwi is about the size of a chicken, but a kiwi's egg is six times the size of a chicken's egg.

If you think this might be hard on the female kiwi, you're right. During the 30 days it takes to grow the egg in her body, the female must eat three times the amount of food she normally eats. But for the last three days or so of that time, the egg gets so large that there is no room left for her to eat at all, and she must go hungry.

However, there is relief for her after the egg has been laid. In four of the five kiwi species, the male is the one to incubate the egg, a process that takes 63 to 92 days (in the fifth species, both parents share the task). That's the least the male can do after all that, right?

Check out the X-ray below.

How are kiwis able to have such large eggs? Three reasons: First, as you can imagine, kiwis would not be able to develop such large eggs if they weren't ground birds. It would be too much weight to carry in flight.

Second, kiwis typically live in areas with abundant food, allowing them to take in enough nutrients to support the development of these huge eggs.

And third, until recently, when humans introduced predators to New Zealand, kiwis historically had few natural predators (which might eat the eggs or easily catch the mothers, which are slowed down by the weight).

Once the egg has been laid and incubated, the kiwi baby has to kick its way out of the egg when it hatches. Unlike other birds, kiwi babies do not have an egg tooth.

Since they grow so large inside the egg, and since incubation is so long, the babies hatch with a full coat of hair-like feathers. Most baby birds have that "ugly-baby-bird" look, but baby kiwis simply look like smaller versions of the adults.

You know how birds that fly have hollow bones to make them lighter? Well, kiwis have marrow in their bones (like mammals), making them heavier than other birds their size.

It may look like kiwis have no wings, but they actually do. The wings are only about an inch (3 cm) long and are usually hidden beneath the hair-like feathers. Each wing has a claw on the tip, but no one really knows the purpose of this claw.

Kiwis' beaks are quite different from those of other birds. Their beaks are long, yet they are pliable and sensitive to touch. And kiwis are the only birds with nostrils at the end of the beak. These special beak features allow them to stick their beaks into the soil and locate worms and insects by smell without ever seeing them.

Check out this video of a kiwi feeding (kiwis are nocturnal and are difficult to find in the wild, and even more difficult to photograph).

One last tidbit. The kiwi is one of the most iconic symbols of any country, as iconic to New Zealand as kangaroos are to Australia. New Zealanders seem to be united in their fondness for these birds. Today, over 90 different organizations work to protect kiwis in over a half million acres (230,000 hectares) of kiwi habitat. The bird is truly a national treasure.

So, the kiwi deserves a place in the A.T.A.B.C.A.H.O.F.

(All That and a Bag of Chips Animal Hall of Fame).

FUN FACT: The phrase "all that" was first used to mean impressive in about 1989 (such as "My girlfriend is all that!"). And then in the mid 90s, people started saying "all that and a bag of chips" to mean good, plus extra. It's possible the phrase began as a way to express your superiority, as in "You're all that, but I'm all that AND a bag of chips!." So, all that and a bag of chips is another way to say awesome!

By the way, this phrase is specifically American in origin. I suppose if it had started England, it would be "All that and a bag of crisps."

What would it be where you live??

Photo Credits:

Kiwi #1 - New Zealand Department of Conservation

Kiwi #2 - Exploring Kiwis

Kiwi X-ray - Reddit

Kiwi Hatchling - Pinterest

Kiwi keepsakes - New Zealand Geographic

Wait! Did you think I was referring to those little brown, fuzzy fruits in the produce section at the market? Nope, those are actually called kiwifruit. And they definitely are not birds.

Wait again! Did you think I was referring to New Zealanders? The people of New Zealand have been referred to as Kiwis since the nickname was given to them during World War I. Again, nope... I'm not talking about the people.

Speaking of New Zealanders, you might think my statement above about the only native mammals being bats and sea mammals is incorrect. After all, humans are certainly mammals, so wouldn't we consider the Maori people to be mammals native to New Zealand? Well, maybe, but the Maori people discovered and settled in New Zealand only 740 years ago (close to the year 1280). That certainly makes them indigenous to the island, but 740 years isn't long compared to the 50 million years since the first kiwis appeared!

What the heck is a Kiwi?

Kiwis consist of five bird species living only on New Zealand. They are in the group of large, flightless birds called ratites, which includes ostriches, emus, cassowaries, rheas, and some species that are now extinct. Kiwis are the smallest (by far) of all the ratites. Perhaps their most distinguishing characteristic is that they are flightless ground birds.

Amazing facts about Kiwis

The genetic heritage of kiwis is confusing. They shared the island of New Zealand with an extinct type of ratites, the 500-pound (227 kg) moa. So, you would think kiwis are closely related to moas. But, DNA evidence has shown that kiwis are more closely related to the elephant birds (also extinct) from Madagascar. And regarding living species, kiwis are more closely related to the emus and cassowaries than to the moas. How can this be possible? Well, studies have shown that the ancestor of kiwis, a bird called Proapteryx, was probably capable of flight, suggesting that kiwi ancestors migrated to New Zealand separate from moas (moas were already large and flightless when the kiwi ancestor arrived on the scene).

Kiwis are about the size of chickens. The largest, the great spotted kiwi, weighs about 7.3 pounds (3.3 kg), and the smallest, the little spotted kiwi, weighs 2.9 pounds (1.3 kg).

I mentioned above that kiwis are sometimes referred to as "honorary mammals." Part of the reason for this is that they appear to be covered in fur, but this is actually thin, hair-like feathers.

Kiwis have really strong legs. Amazingly, a kiwi's muscular legs make up about a third of its entire body weight! With these powerful legs, kiwis can run as fast as a human. In a single night, a kiwi can cover its entire territory, which is often hilly and difficult to traverse. How big is an individual's territory? Up to the size of 60 football fields. That's 79 acres (32 hectares)!

Okay, this may be the most impressive thing about kiwis. These birds typically lay one egg per season, but that one egg is the largest egg (relative to their body size) of any other bird. Consider this... a human baby is typically about 5% of the weight of the mother giving birth. And (drumroll please...) the kiwi's egg can be a whopping 25% of the mother bird's weight. Let's put this into perspective. This would be like a 150-pound (68 kg) woman giving birth to a 37-pound (16.8 kg) baby. Yeeeouch!

Let's look at it another way. A kiwi is about the size of a chicken, but a kiwi's egg is six times the size of a chicken's egg.

If you think this might be hard on the female kiwi, you're right. During the 30 days it takes to grow the egg in her body, the female must eat three times the amount of food she normally eats. But for the last three days or so of that time, the egg gets so large that there is no room left for her to eat at all, and she must go hungry.

However, there is relief for her after the egg has been laid. In four of the five kiwi species, the male is the one to incubate the egg, a process that takes 63 to 92 days (in the fifth species, both parents share the task). That's the least the male can do after all that, right?

Check out the X-ray below.

How are kiwis able to have such large eggs? Three reasons: First, as you can imagine, kiwis would not be able to develop such large eggs if they weren't ground birds. It would be too much weight to carry in flight.

Second, kiwis typically live in areas with abundant food, allowing them to take in enough nutrients to support the development of these huge eggs.

And third, until recently, when humans introduced predators to New Zealand, kiwis historically had few natural predators (which might eat the eggs or easily catch the mothers, which are slowed down by the weight).

Once the egg has been laid and incubated, the kiwi baby has to kick its way out of the egg when it hatches. Unlike other birds, kiwi babies do not have an egg tooth.

Since they grow so large inside the egg, and since incubation is so long, the babies hatch with a full coat of hair-like feathers. Most baby birds have that "ugly-baby-bird" look, but baby kiwis simply look like smaller versions of the adults.

You know how birds that fly have hollow bones to make them lighter? Well, kiwis have marrow in their bones (like mammals), making them heavier than other birds their size.

It may look like kiwis have no wings, but they actually do. The wings are only about an inch (3 cm) long and are usually hidden beneath the hair-like feathers. Each wing has a claw on the tip, but no one really knows the purpose of this claw.

Kiwis' beaks are quite different from those of other birds. Their beaks are long, yet they are pliable and sensitive to touch. And kiwis are the only birds with nostrils at the end of the beak. These special beak features allow them to stick their beaks into the soil and locate worms and insects by smell without ever seeing them.

Check out this video of a kiwi feeding (kiwis are nocturnal and are difficult to find in the wild, and even more difficult to photograph).

One last tidbit. The kiwi is one of the most iconic symbols of any country, as iconic to New Zealand as kangaroos are to Australia. New Zealanders seem to be united in their fondness for these birds. Today, over 90 different organizations work to protect kiwis in over a half million acres (230,000 hectares) of kiwi habitat. The bird is truly a national treasure.

So, the kiwi deserves a place in the A.T.A.B.C.A.H.O.F.

(All That and a Bag of Chips Animal Hall of Fame).

FUN FACT: The phrase "all that" was first used to mean impressive in about 1989 (such as "My girlfriend is all that!"). And then in the mid 90s, people started saying "all that and a bag of chips" to mean good, plus extra. It's possible the phrase began as a way to express your superiority, as in "You're all that, but I'm all that AND a bag of chips!." So, all that and a bag of chips is another way to say awesome!

By the way, this phrase is specifically American in origin. I suppose if it had started England, it would be "All that and a bag of crisps."

What would it be where you live??

Photo Credits:

Kiwi #1 - New Zealand Department of Conservation

Kiwi #2 - Exploring Kiwis

Kiwi X-ray - Reddit

Kiwi Hatchling - Pinterest

Kiwi keepsakes - New Zealand Geographic

Published on July 18, 2019 05:34

June 29, 2019

Awesome Animal - Binturong

Thanks to Tiffany and her son, Royce, for suggesting the Binturong.

It's often called a bearcat, but it is neither a bear nor a cat. It smells like buttered popcorn, but I'm pretty sure it doesn't taste like popcorn. The binturong is a viverrid. What is a viverrid, you ask? Let's find out more.

What the heck is a Binturong?

The binturong is a mammal that lives in South and Southeast Asia. As I said above, although it is called a bearcat, it is actually in the family Viverridae (the viverrids), which is an ancient group of mammals found only in the eastern hemisphere. The family also includes civets and genets. Binturongs have shaggy, black hair, stiff white whiskers, and a monkey-like prehensile tail. So perhaps instead of calling it a bearcat, people should call it a bearcatmonkey (although it's really none of these).

Amazing facts about Binturongs

Although binturongs are in the order Carnivora, they eat as much (or more) fruit as they eat other animals. When they do hunt, they sneak around in the rainforest treetops like a cat and catch insects, birds, and rodents. They usually hunt at night, but they often eat fruit during the day, sometimes lounging around on branches as they handle the fruit with their agile hands. Binturongs can also swim and dive well, and on hot days they can even be seen catching fish as they cool down in the water.

Binturongs are one of only two carnivore mammals that have a prehensile tale (the other is the kinkajou, which is unrelated and lives in Central and South America). They can use this tail as a fifth hand, to help them climb through the trees and hang on to branches.

Binturongs are remarkably docile toward humans, and this has resulted in them being captured from the wild in large numbers, to be sold around the world as pets. This, along with destruction of vast areas of their forest habitat, has caused a significant decrease in the number of wild binturongs in Asia. They are also captured for zoos, and they are hunted for food. Unfortunately, today they are rarely seen in the wild.

Okay, what's up with this buttered popcorn smell? It's true, and here's why: In the wild, binturongs are solitary animals—they rarely come face-to-face with each other. And that's the way they like it. To warn others away from their territory, they frequently urinate on the trees. The resulting smell is a signal to other binturongs, "Hey, I live here. Go away!" Oddly enough, they also use this smell during mating season, in which case the meaning changes to, "Hey, I live here. Want to stick around and make babies?"

But I still haven't explained the popcorn smell. Scientists have identified 29 chemical compounds in binturong urine. The one compound found in every sample was 2-acetyl-1-pyrroline (let's just call it 2-AP). Remarkably, 2-AP is the exact same chemical that gives cooked popcorn its wonderful scent.

But this creates more questions than answers! The 2-AP in popcorn is only produced when the popcorn is heated up and popped. The high temperature is necessary to get that smell. Binturongs are awesome, but they certainly can't produce such high temperatures in their bodies. So, we don't know for sure how they do it, but scientists suggest that the 2-AP might be produced when the binturong urine comes into contact with specific bacteria that live on the animals' skin or fur.

Since males have more 2-AP in their urine than females, then it seems logical that leaving their scent on the branches not only tells other binturongs that a binturong is nearby, it even tells them if the nearby binturong is a male or female (precise communication is important, don't you think?).

Let's talk about binturong babies for a moment.

First, binturongs are one of the few mammal species capable of embryonic diapause. The means the female, once her eggs have been fertilized, can delay the eggs' implantation until environmental conditions are just right. Okay, in my opinion that qualifies as a superpower. The females can mate whenever they find a male, but then they can delay birth until they are ready.

Typically, a female will give birth to only two babies, but sometimes there are as many as six.

Check out this video of binturong babies.

Binturong babies smell like popcorn as much (or more) than the adults. But... the babies also have their own superpower. During the first few months, when the young are most vulnerable, the babies have the ability to squirt out a foul-smelling liquid (like a skunk). As they grow older they become better able to protect themselves, and they soon lose this stinky superpower.

Binturongs have an interesting relationship with strangler fig trees. Not surprisingly, Binturongs eat the figs from these trees and then poop them out somewhere. But as it turns out, a strangler fig seed cannot germinate on its own. It has to have the binturong's help. The binturong is one of only two known animals that have the correct digestive enzymes that can break down the tough outer covering of the fig's seeds. So this makes the binturong kind of important to the strangler fig trees.

One last tidbit. Ever wonder what a binturong would look like in a formal portrait? Of course you have. Well, ZooPortraits is a fun organization that creates and uses "ironic caricatures" to teach about wildlife and to raise money for conservation. For your viewing pleasure, below is a binturong in a very formal setting (not exactly its natural habitat).

So, the binturong deserves a place in the D.A.H.O.F.

(Dope Animal Hall of Fame).

FUN FACT: The word dope originated in the 1840s, and it referred to a thick liquid (such as a lubricant) used to prepare a surface. In the 1880s, the word began to be used to refer to any illicit drug. Then in about 1905, the word began to refer to news or information (What's the latest dope on the election?). And then much more recently, it became a slang word for cool (Yo, that new shirt is dope!). So, dope is another way to say awesome!

Photo Credits:

Binturong #1 - Wikipedia

Binturong lounging on limb - Wild Republic

Binturong with babies - ZooBorns

Baby binturong hanging in tree - ZooBorns

Binturong formal portrait - ZooPortraits

It's often called a bearcat, but it is neither a bear nor a cat. It smells like buttered popcorn, but I'm pretty sure it doesn't taste like popcorn. The binturong is a viverrid. What is a viverrid, you ask? Let's find out more.

What the heck is a Binturong?

The binturong is a mammal that lives in South and Southeast Asia. As I said above, although it is called a bearcat, it is actually in the family Viverridae (the viverrids), which is an ancient group of mammals found only in the eastern hemisphere. The family also includes civets and genets. Binturongs have shaggy, black hair, stiff white whiskers, and a monkey-like prehensile tail. So perhaps instead of calling it a bearcat, people should call it a bearcatmonkey (although it's really none of these).

Amazing facts about Binturongs

Although binturongs are in the order Carnivora, they eat as much (or more) fruit as they eat other animals. When they do hunt, they sneak around in the rainforest treetops like a cat and catch insects, birds, and rodents. They usually hunt at night, but they often eat fruit during the day, sometimes lounging around on branches as they handle the fruit with their agile hands. Binturongs can also swim and dive well, and on hot days they can even be seen catching fish as they cool down in the water.

Binturongs are one of only two carnivore mammals that have a prehensile tale (the other is the kinkajou, which is unrelated and lives in Central and South America). They can use this tail as a fifth hand, to help them climb through the trees and hang on to branches.

Binturongs are remarkably docile toward humans, and this has resulted in them being captured from the wild in large numbers, to be sold around the world as pets. This, along with destruction of vast areas of their forest habitat, has caused a significant decrease in the number of wild binturongs in Asia. They are also captured for zoos, and they are hunted for food. Unfortunately, today they are rarely seen in the wild.

Okay, what's up with this buttered popcorn smell? It's true, and here's why: In the wild, binturongs are solitary animals—they rarely come face-to-face with each other. And that's the way they like it. To warn others away from their territory, they frequently urinate on the trees. The resulting smell is a signal to other binturongs, "Hey, I live here. Go away!" Oddly enough, they also use this smell during mating season, in which case the meaning changes to, "Hey, I live here. Want to stick around and make babies?"

But I still haven't explained the popcorn smell. Scientists have identified 29 chemical compounds in binturong urine. The one compound found in every sample was 2-acetyl-1-pyrroline (let's just call it 2-AP). Remarkably, 2-AP is the exact same chemical that gives cooked popcorn its wonderful scent.

But this creates more questions than answers! The 2-AP in popcorn is only produced when the popcorn is heated up and popped. The high temperature is necessary to get that smell. Binturongs are awesome, but they certainly can't produce such high temperatures in their bodies. So, we don't know for sure how they do it, but scientists suggest that the 2-AP might be produced when the binturong urine comes into contact with specific bacteria that live on the animals' skin or fur.

Since males have more 2-AP in their urine than females, then it seems logical that leaving their scent on the branches not only tells other binturongs that a binturong is nearby, it even tells them if the nearby binturong is a male or female (precise communication is important, don't you think?).

Let's talk about binturong babies for a moment.

First, binturongs are one of the few mammal species capable of embryonic diapause. The means the female, once her eggs have been fertilized, can delay the eggs' implantation until environmental conditions are just right. Okay, in my opinion that qualifies as a superpower. The females can mate whenever they find a male, but then they can delay birth until they are ready.

Typically, a female will give birth to only two babies, but sometimes there are as many as six.

Check out this video of binturong babies.

Binturong babies smell like popcorn as much (or more) than the adults. But... the babies also have their own superpower. During the first few months, when the young are most vulnerable, the babies have the ability to squirt out a foul-smelling liquid (like a skunk). As they grow older they become better able to protect themselves, and they soon lose this stinky superpower.

Binturongs have an interesting relationship with strangler fig trees. Not surprisingly, Binturongs eat the figs from these trees and then poop them out somewhere. But as it turns out, a strangler fig seed cannot germinate on its own. It has to have the binturong's help. The binturong is one of only two known animals that have the correct digestive enzymes that can break down the tough outer covering of the fig's seeds. So this makes the binturong kind of important to the strangler fig trees.

One last tidbit. Ever wonder what a binturong would look like in a formal portrait? Of course you have. Well, ZooPortraits is a fun organization that creates and uses "ironic caricatures" to teach about wildlife and to raise money for conservation. For your viewing pleasure, below is a binturong in a very formal setting (not exactly its natural habitat).

So, the binturong deserves a place in the D.A.H.O.F.

(Dope Animal Hall of Fame).

FUN FACT: The word dope originated in the 1840s, and it referred to a thick liquid (such as a lubricant) used to prepare a surface. In the 1880s, the word began to be used to refer to any illicit drug. Then in about 1905, the word began to refer to news or information (What's the latest dope on the election?). And then much more recently, it became a slang word for cool (Yo, that new shirt is dope!). So, dope is another way to say awesome!

Photo Credits:

Binturong #1 - Wikipedia

Binturong lounging on limb - Wild Republic

Binturong with babies - ZooBorns

Baby binturong hanging in tree - ZooBorns

Binturong formal portrait - ZooPortraits

Published on June 29, 2019 03:40

June 12, 2019

Awesome Animal - Wild Turkey

Meat from domesticated turkeys has become so ubiquitous in grocery stores and restaurants that people tend to forget about the ancestors of the domestic turkey, the

wild turkey

. But as one of the largest birds in their native range, wild turkeys are fascinating and well worth a closer look.

What the heck is a Wild Turkey?

Turkeys are large birds that live mostly in North America (US, Mexico, and Canada). Turkeys are in the order Galliformes, which also includes pheasants, chickens, quail, partridges, grouse, junglefowl, and other similar birds). Turkeys are easily recognized by their featherless heads and loose folds of skin on the head and neck. There are only two species of true wild turkeys, and one of the species has five or six distinctive subspecies. The eastern turkey is the subspecies that lives on our new property:

Amazing facts about Wild Turkeys

Wild turkeys are omnivorous. They not only feed on seeds, nuts, berries, fruits, and grasses, but they also love gobbling (no pun intended) insects, as well as small frogs, salamanders, lizards, and snakes.

Turkeys have a lot of names. Mature males are called toms, gobblers, or longbeards. Mature females are hens. Juvenile males are called jakes, whereas juvenile females are jennies. And the chicks are called poults (this word comes from poultry).

Male turkeys have elaborate behaviors for attracting and impressing females. They use a gobble call to attract females. Not only is this call quite different from the call of any other bird, it is also loud! A turkey's gobble can be heard a mile away.

Perhaps even more impressive than the gobble is the male turkey's ability to strut. They fan out their tail feathers and puff up all their other feathers to look larger. They also emit two other sounds, spitting and drumming, both of which are subtle and rather difficult to capture on video or audio recordings. But if you turn your volume up, you can hear toms spitting and drumming in this video . Below is a tom strutting, trying to impress a hen. To me, she looks only mildly interested.

An adult turkey has between 5,000 and 6,000 feathers!

Males have sharp, wicked-looking spurs on their legs, which they use when they fight each other for dominance. Males (and 10 to 20% of females) have a long tassel of specialized hair-like feathers hanging from their lower necks, called a beard. Although no one knows for sure, these beards probably help to impress females (the longer the beard, the older and more virile the tom).

Turkeys have weird-looking heads. Above the male's beak is a fleshy protuberance called a snood (yep, it really is called a snood). Again, this structure is used to impress females (studies show that females prefer toms with longer snoods... in turkeys, size really does matter). The loose, fleshy stretch of skin below the chin is the wattle. And the bumpy masses of skin on the neck are caruncles. Like a really ugly mood ring, these bumpy parts turn colors depending on the turkey's mood: they turn red to attract a hen, but they turn blue when the turkey is frightened. The tom below has a particularly impressive snood, wattle, and caruncles. Sexy, huh?

There is a commonly-believed myth that the wild turkey almost became the national bird of the United States (the bald eagle has that distinction) when Benjamin Franklin argued for it. Here's the true story: Ben Franklin did write a letter to his daughter in 1784, in which he criticized the bald eagle (because it was chosen for the national seal). He wrote that the bald eagle is a bird of bad moral character and does not get his living honestly... he is too lazy to fish for himself. He went on to say that, compared to the eagle, the turkey is a much more respectable bird, and though a little vain and silly, a bird of courage. So, although Ben obviously liked the turkey, technically he didn't really propose making it the national symbol.

Wild turkeys were a favorite food of Native Americans. In fact, the turkey is one of only two domesticated birds native to North America (the other is the Muscovy duck). The domestic turkey originally came from Mexico. Native Americans in central Mexico, sometime between 1000 BC and 100 BC, domesticated the south Mexican wild turkey (the only subspecies that does not live in the U.S.). The Spaniards took this domesticated subspecies back to Europe in the 1500s, and eventually it spread throughout Europe as a farm animal. Ironically, settlers from England brought these domestic turkeys with them to Massachusetts, unaware that a larger, closely-related subspecies already lived in the wilds of Massachusetts. It is believed that all domestic turkey breeds came from the south Mexican wild turkey subspecies.

Wild turkeys almost went extinct. When Europeans first arrived, millions of turkeys lived from Canada south into Mexico. But by about 1900, most of them were gone due to overhunting and habitat loss. By the late 1930s, there were only 30,000 left. By the 1940s, only isolated pockets of them existed. Through intensive conservation efforts, these birds gradually rebounded. Now it is estimated that about 7 million live in the U.S.

Many people are surprised to learn that turkeys can fly. Actually, they are strong flyers (although only for a relatively short distance... about a quarter mile). Turkeys fly up into trees every evening, where they roost in safety for the night.

Not only can turkeys fly, but they can run at up to 25 miles per hour (40 kph)!

Hen turkeys lay 10 to 14 eggs. The eggs hatch after at least 28 days. The hen feeds the poults, but only briefly. Within a few days, the poults are running around catching insects on their own. The males play no role at all in raising the young. That doesn't seem fair, does it?

One last tidbit of information. There are several other birds around the world that are called turkeys, but those are not closely related to the turkeys of North America. One example is the brush turkey of Australia (also called the bush turkey, scrub turkey, or gweela). When Trish and I explored Queensland, Australia last year, we saw many of these. They are not only common, but they often seem unafraid of humans, sometimes walking by within a few meters. These birds are awesome, too, but although they are in the same order, they are in a different family from the wild turkeys of North America. Here's a brush turkey.

So, wild turkeys deserve a place in the N.A.H.O.F.

So, wild turkeys deserve a place in the N.A.H.O.F.

(Neato Animal Hall of Fame).

FUN FACT: The word neat originated in the early 1300s, and it meant polished, handsome, trim, and clean. At some point the word became a slang expression for great or wonderful. It was already being used a lot when I was a kid in the 1960s, so it must have started before then. And then around 1968, American teens began using a variation of the word: neato. If you say neato today, people would consider you laughably out of touch (or perhaps fashionably retro). Regardless, neato is another way to say awesome!

Photo Credits:

Flowing spring and turkeys in yard - Stan C. Smith

Bearded Tom Turkey - National Wild Turkey Federation

Tom strutting for hen - Robert Burton/USFWS

Tom snood and wattle - Lansing Wild Birds Unlimited

Domestic turkeys - All Over Albany

Hen turkey with poults - TribLive via Wikimedia Commons

Australian brush turkey - Di Donovan via ABC

What the heck is a Wild Turkey?

Turkeys are large birds that live mostly in North America (US, Mexico, and Canada). Turkeys are in the order Galliformes, which also includes pheasants, chickens, quail, partridges, grouse, junglefowl, and other similar birds). Turkeys are easily recognized by their featherless heads and loose folds of skin on the head and neck. There are only two species of true wild turkeys, and one of the species has five or six distinctive subspecies. The eastern turkey is the subspecies that lives on our new property:

Amazing facts about Wild Turkeys

Wild turkeys are omnivorous. They not only feed on seeds, nuts, berries, fruits, and grasses, but they also love gobbling (no pun intended) insects, as well as small frogs, salamanders, lizards, and snakes.

Turkeys have a lot of names. Mature males are called toms, gobblers, or longbeards. Mature females are hens. Juvenile males are called jakes, whereas juvenile females are jennies. And the chicks are called poults (this word comes from poultry).

Male turkeys have elaborate behaviors for attracting and impressing females. They use a gobble call to attract females. Not only is this call quite different from the call of any other bird, it is also loud! A turkey's gobble can be heard a mile away.

Perhaps even more impressive than the gobble is the male turkey's ability to strut. They fan out their tail feathers and puff up all their other feathers to look larger. They also emit two other sounds, spitting and drumming, both of which are subtle and rather difficult to capture on video or audio recordings. But if you turn your volume up, you can hear toms spitting and drumming in this video . Below is a tom strutting, trying to impress a hen. To me, she looks only mildly interested.

An adult turkey has between 5,000 and 6,000 feathers!

Males have sharp, wicked-looking spurs on their legs, which they use when they fight each other for dominance. Males (and 10 to 20% of females) have a long tassel of specialized hair-like feathers hanging from their lower necks, called a beard. Although no one knows for sure, these beards probably help to impress females (the longer the beard, the older and more virile the tom).

Turkeys have weird-looking heads. Above the male's beak is a fleshy protuberance called a snood (yep, it really is called a snood). Again, this structure is used to impress females (studies show that females prefer toms with longer snoods... in turkeys, size really does matter). The loose, fleshy stretch of skin below the chin is the wattle. And the bumpy masses of skin on the neck are caruncles. Like a really ugly mood ring, these bumpy parts turn colors depending on the turkey's mood: they turn red to attract a hen, but they turn blue when the turkey is frightened. The tom below has a particularly impressive snood, wattle, and caruncles. Sexy, huh?

There is a commonly-believed myth that the wild turkey almost became the national bird of the United States (the bald eagle has that distinction) when Benjamin Franklin argued for it. Here's the true story: Ben Franklin did write a letter to his daughter in 1784, in which he criticized the bald eagle (because it was chosen for the national seal). He wrote that the bald eagle is a bird of bad moral character and does not get his living honestly... he is too lazy to fish for himself. He went on to say that, compared to the eagle, the turkey is a much more respectable bird, and though a little vain and silly, a bird of courage. So, although Ben obviously liked the turkey, technically he didn't really propose making it the national symbol.

Wild turkeys were a favorite food of Native Americans. In fact, the turkey is one of only two domesticated birds native to North America (the other is the Muscovy duck). The domestic turkey originally came from Mexico. Native Americans in central Mexico, sometime between 1000 BC and 100 BC, domesticated the south Mexican wild turkey (the only subspecies that does not live in the U.S.). The Spaniards took this domesticated subspecies back to Europe in the 1500s, and eventually it spread throughout Europe as a farm animal. Ironically, settlers from England brought these domestic turkeys with them to Massachusetts, unaware that a larger, closely-related subspecies already lived in the wilds of Massachusetts. It is believed that all domestic turkey breeds came from the south Mexican wild turkey subspecies.

Wild turkeys almost went extinct. When Europeans first arrived, millions of turkeys lived from Canada south into Mexico. But by about 1900, most of them were gone due to overhunting and habitat loss. By the late 1930s, there were only 30,000 left. By the 1940s, only isolated pockets of them existed. Through intensive conservation efforts, these birds gradually rebounded. Now it is estimated that about 7 million live in the U.S.

Many people are surprised to learn that turkeys can fly. Actually, they are strong flyers (although only for a relatively short distance... about a quarter mile). Turkeys fly up into trees every evening, where they roost in safety for the night.

Not only can turkeys fly, but they can run at up to 25 miles per hour (40 kph)!

Hen turkeys lay 10 to 14 eggs. The eggs hatch after at least 28 days. The hen feeds the poults, but only briefly. Within a few days, the poults are running around catching insects on their own. The males play no role at all in raising the young. That doesn't seem fair, does it?

One last tidbit of information. There are several other birds around the world that are called turkeys, but those are not closely related to the turkeys of North America. One example is the brush turkey of Australia (also called the bush turkey, scrub turkey, or gweela). When Trish and I explored Queensland, Australia last year, we saw many of these. They are not only common, but they often seem unafraid of humans, sometimes walking by within a few meters. These birds are awesome, too, but although they are in the same order, they are in a different family from the wild turkeys of North America. Here's a brush turkey.

So, wild turkeys deserve a place in the N.A.H.O.F.

So, wild turkeys deserve a place in the N.A.H.O.F.(Neato Animal Hall of Fame).

FUN FACT: The word neat originated in the early 1300s, and it meant polished, handsome, trim, and clean. At some point the word became a slang expression for great or wonderful. It was already being used a lot when I was a kid in the 1960s, so it must have started before then. And then around 1968, American teens began using a variation of the word: neato. If you say neato today, people would consider you laughably out of touch (or perhaps fashionably retro). Regardless, neato is another way to say awesome!

Photo Credits:

Flowing spring and turkeys in yard - Stan C. Smith

Bearded Tom Turkey - National Wild Turkey Federation

Tom strutting for hen - Robert Burton/USFWS

Tom snood and wattle - Lansing Wild Birds Unlimited

Domestic turkeys - All Over Albany

Hen turkey with poults - TribLive via Wikimedia Commons

Australian brush turkey - Di Donovan via ABC

Published on June 12, 2019 08:03

June 2, 2019

Awesome Animal - Armadillo

After 27 years at our previous home, Trish and I recently moved to a new property to the south. Although it takes 70 minutes to drive between the two homes, the new place is actually only 34 miles (55 km) south as the crow flies (I'm not sure how many people use the term "as the crow flies," but it means in a straight line). But there are significant changes in the natural habitat in those 34 miles. The new house is in a region called the Ozarks. One animal that is rare at the old house location but is common at the new property is the nine-banded armadillo.

This creature fascinates me, so I was considering featuring it as an Awesome Animal. And then today we discovered that an armadillo family had established residence beneath our garden shed. Four young armadillos were wandering around the area feeding on worms, grubs, and other critters. Here's a photo my daughter-in-law took of two of the youngsters. They were about 10 inches (25 cm) long, not including the tail. That's about half the length of adults.

What the heck is an Armadillo?

Armadillo is a Spanish word meaning little armored one. This of course refers to the bony, protective plates that cover the creature's body. There are about 20 living species of armadillos, all of them native to the Americas. Only one species, the nine-banded armadillo, lives in the United States. The others are found in Central and South America.

Amazing facts about Armadillos

Armadillos are the only living mammals that have this type of bony armor. In a previous article I featured the pangolin, which is a mammal with large, protective scales, but those scales are attached to the skin and are not actually made of bone. With Armadillos, portions of the armor are bone-like, particularly over the shoulders and hips, as well as several bands that are connected by flexible skin. See the photo below of the skeleton of a nine-banded armadillo.

Contrary to popular belief, most armadillos cannot roll into a ball and cover themselves with their shell (pangolins can do this). Only two species, both of them three-banded armadillos, are capable of curling their heads and feet up and contorting their shells into a tight ball that is almost impenetrable to predators.

Nine-banded armadillo do not always have nine bands. In fact, they can have 7 to 11 bands. This species typically grows to about 12 pounds (5 kg).

Nine-banded armadillos are rapidly moving north and east in the United States! It wasn't until the late 1800s that this creature crossed the Rio Grande from Mexico into the United States. And since then it has been steadily spreading across the continent. When I was growing up in Kansas, I never once saw an armadillo. Now I see them regularly, both in Kansas and in Missouri, and they have been sighted as far north as Nebraska and Iowa. It is tempting to assume that this progression is a result of climate change, but it is probably more due to the fact that there are no natural armadillo predators here, as well as the creatures' rapid reproductive rate (a female can produce up to 56 babies in her lifetime).

Although this expansion seems to be a natural phenomenon, many people consider armadillos pests, mainly because nine-banded armadillos like to dig and can be destructive to gardens, and their burrows can destabilize houses and sheds.

Historically, people have eaten armadillos, but usually they have been considered "last resort" food animals. During the Great Depression (in the U.S.), armadillos were called "poor man's pork" and "Hoover hog" (because many people blamed President Hoover for the Great Depression).

Armadillos are diverse. The 20 or so different species live in diverse habitats, from rainforests, to grasslands, to deserts. The largest is the giant armadillo , an endangered South American species that grows to over 100 pounds (45 kg). See below.

The smallest armadillo is perhaps the most bizarre... the pink fairy armadillo . This species is only 5 inches (12.7 cm) long and lives in the deserts of Argentina. This delightful creature is rarely seen and we know very little about its habits. To give you an idea of how elusive they are, Mariella Superina of Argentina’s National Scientific and Technical Research Council has been studying other armadillos in the pink fairy’s habitat for 13 years and has never once seen one in the wild! See photo below.

But people occasionally come across these creatures. Check out this video of a pink fairy armadillo digging in the sand.

Yet another species is the screaming hairy armadillo , which is native to the Monte Desert in South America. True to its name, this armadillo emits a loud squeal whenever it is threatened. It also has more hair than most of the other species. See photo below.

One last fascinating fact. As a rule, the nine-banded armadillo almost always gives birth to four genetically identical quadruplets (which explains why there are exactly four babies living under our shed). In humans, identical twins or triplets make up only 0.2% of the population. In other words, they are quite rare. There are a few other animals that often have identical twins (ferrets, deer, and polar bears, for example), but only the nine-banded armadillo makes a habit of popping out identical quadruplets.

So, armadillos deserve a place in the V.A.H.O.F.

(Virtuosic Animal Hall of Fame).

FUN FACT: The word virtuoso originated in the early 1600s, and it means a person who has special knowledge or skill in a field, particularly someone who excels in musical skill. The adjective version of the word is virtuosic. Not surprisingly, people have expanded the use of virtuosic to describe almost anything that is outstanding. So virtuosic is another way to say awesome! Photo Credits:

Nine-banded armadillo - Rich Anderson on Flickr

Young nine-banded armadillo - Traci Smith-Reams

Nine-banded armadillo skeleton - Ryan Somma via Wikipedia

Three-banded armadillo in a ball - Smithsonian National Zoo

Pink Fairy Armadillo in hands - Mariella Superina/Paul Vogt via Wired

Screaming hairy armadillo - Smithsonian National Zoo

Nine-banded armadillo quadruplets - QuantumBiologist