Kate Innes's Blog, page 2

April 8, 2020

A light in the darkness

A week of isolation (in the broadest sense, as I am sharing the property with 3 teenagers, a dog, 4 chickens – and even, occasionally, my doctor husband) is already done and gone, and I wonder how you are finding it? I’ve been surprised at how quickly this new way of living has started to feel normal. I look at films and ads on tv of people milling about in groups, hugging and kissing, and wonder why they are taking so few precautions. Shouldn’t they be more wary? Where on earth are their masks and gloves?!

I think about going out to get provisions and a great weariness overwhelms me. It’s so demanding and stressful negotiating public spaces. Better to stay at home and, hopefully, harm no one.

I suppose it is one of the great abilities of our species that we so quickly adapt to new circumstances and environments. And that is a good way into thinking about my next book recommendation to you – ‘Bearmouth’ by Liz Hyder. Published in 2019 by Pushkin Press.

In the spirit of full disclosure, Liz is a writer friend of mine. I remember the moment, sitting in her front room, when she told me about her nearly finished YA book set in a fictionalised Victorian mine. At the time I thought “what a fabulous title!”

Now, six months after its publication, I can tell you that the content more than matches the cover.

The main character is one of the young mine workers, Newt, and the story is told in Newt’s unique voice and language, (which takes only two or three pages to get used to – especially if you have a phonetic speller in your household, as I do). The men, boys and (secret) girls in the mine are all subject to the most rigid form of isolation. Newt hasn’t seen daylight since the age of four. The workers are exploited, and kept ignorant of their rights. The masters exert their authority ruthlessly, with tiny rewards and a twisted form of religion.

Sounds dark – and it is, literally and figuratively. But there is so much humanity in Bearmouth – as we also see at this dark time in our own society. People help each other, even at risk of their own death. People give hope to each other, and like the rare candles in the dark of the mine, strength, compassion and love shine out in the darkness. The mine is a microcosm of society, and the plot shows how courage and vision can change even the most entrenched evil.

I read Bearmouth in one sitting, on a plane on my way to see my dad in the US (and doesn’t that feel like another era already?) I was utterly immersed in a story that flows like water through an underground cave system, carrying you on to the inevitable waterfall of freedom. Forgive me the poetic licence, please. What I am trying to say is that ‘Bearmouth’ will grab you and not let you go – taking you through the darkest places and then, so satisfyingly, into starlight.

Although marketed as a Young Adult novel, and shortlisted for the Waterstones Children’s Books of the Year 2020, ‘Bearmouth’ is a great adult read too.

I hope you enjoy it as much as I did.

Hopefully not a thousand and one nights in lockdown

Distraction. It can be good, it can be bad.

We probably all know a bit about distraction on social media. When I’ve spent too long scrolling through Twitter or Facebook, I often feel sheepish. A bit ashamed. ‘Shouldn’t you be spending ALL your time in constructive pursuits?’ I demand of myself.

We can be pretty harsh on ourselves.

But it is something that eats away at concentration, and I would like to do it less and get the scales of my time better balanced.

Then there is the good kind of distraction. At the moment, I don’t want to think about the possibility of members of my family who work in the NHS becoming ill. If I think about it too much, I might frighten the children with my anxiety. And to distract myself from thinking about that, I read, I write, I research, I watch films. I look out at the world. There is so much to think about.

Good distraction leads the mind away from mithering over hurts or potential disasters. A toddler who is about to lose their temper about a fallen ice cream can often be placated with a balloon, and in the same way, our monkey mind can sometimes be redirected from destructive ruminating by something new, exciting and shiny.

My third recommendation for a good read for this extraordinary time is ‘One Thousand and One Arabian Nights’ written by Geraldine McCaughrean (Oxford Story Collections edition). I think everyone knows a little bit about ‘The Arabian Nights’. I only knew the bare bones before getting hold of this version and taking it on a holiday in a camper van through Norway (not the most appropriate context!). What I was not prepared for was the humour, the modernity, the cunning, the poetry, and the beauty of the stories, embedded in the embracing arc of revenge and love rendered so movingly by Geraldine McCaughrean.

This is often marketed as children’s fiction – Sinbad the Sailor, Ali Baba, Ala al-Din and his wonderful lamp (and this version is suitable for children) – but ‘The Arabian Nights’ is more than just those disneyfied tales. It is a collection of stories for all ages, that have their origin in the oral tradition of Asia and the Middle East, when the long, dark nights of the desert could be made more enjoyable by sharing tales and music around a fire.

These tales were written down perhaps as early as the 8th century AD, and certainly by medieval times, but the original, oral tales are much older – stretching in time and place to the great dynasties of India and Persia – with Arabian tales added later. There are lots of adventures and burlesques, but also more subtle tales of tricks, thieves, fables, scolds – all giving an insight into the abiding human condition. (The erotica is omitted from this edition – you may be disappointed to hear – but there are many other versions to choose from.)

At the heart of the tale is the clever story teller, Shahrazad, who must distract her husband, King Shahryar, every night with a new story. He is determined to exact revenge on women in general for his first wife’s betrayal and infidelity, (‘Woman’s love is as long as the hairs on a chicken’s egg’ he tells her. If any writers amongst you require simile or metaphor inspiration, it is here in abundance) by beheading a new wife every morning. Shahrazad is his thousandth bride. Scholars have explained her away as a frame for a collection of Arabian tales – a bit like The Decameron or the semi-legendary events around the creation of ‘Frankenstein’ by Mary Shelley.

But Shahrazad is not consigned to being merely a wooden frame for the tales in this version. She is a quick-thinking woman of foresight, bravery, resourcefulness and passion. She knows the power of story to distract and redirect. Her strength is in her ability to create new worlds for her psychopathic husband to inhabit every night, worlds in which he doesn’t have to be revengeful and angry. Where he can see all sides of an event, rather than just one point of view. Where he can become someone else.

The stories she marshals to keep the King from ordering her death are very entertaining. But her management of her husband’s moods and insecurities is a master class in the best kind of manipulation. I suppose her ability to fall in love with a serial killer could be a mark against Shahrazad, but as she converts him to reasonable behaviour in the end, and it is a story not real life, I think we ought to let her off.

I wonder if the creator of the story of Shahrazad was a woman. I really appreciate the way Geraldine McCaughrean, the contemporary storyteller, has explored her inner thoughts and her relationship with her younger sister. But whoever it was, they have brought Shahrazad and her rich store of tales to life for countless listeners and readers from all genders, ages and nationalities, for thousands of years.

So I hope you enjoy her tales and embrace the distraction, at least for a while.

April 2, 2020

June 10, 2019

Bad Guys Make Good Plots

Battle_of_Courtrai3 Chroniques de France ou de St Denis, BL Royal MS 20 C vii f. 34

Battle_of_Courtrai3 Chroniques de France ou de St Denis, BL Royal MS 20 C vii f. 34Recently I was asked to contribute a guest post to the fabulous ‘History Girls’ Blog. This is a group of best-selling writers of historical content, fiction, non-fiction, for children and adults. Needless to say, I was delighted to be part of it, and here is the blog I wrote – about the necessity of a good villain.

A story needs a villain – someone to get the action going and make the protagonist look heroic. This is as true for historical fiction as it is for any other kind. We love to shiver at their evilness and then gloat as they get their comeuppance. And history certainly has plenty of real villains to choose from for the historical novelist. It is jam-packed with good material for bad guys.

In All the Winding World, my latest medieval novel set in the late 13th century during the Anglo-French War, one particular historical character galloped into the plot displaying all the necessary qualifications. Rich, cruel, self-centred, eccentric, creepy, sadistic – Robert II Count of Artois had it all. Including a gory and well-deserved demise.

You’ve probably never heard of him. Neither had I. Born in 1250 AD, he was the son of Count Robert I and Matilda of Brabant – and nephew of the sainted King Louis IX of France. However, the piety of his uncle had not rubbed off. Count Robert II was a hedonist with the means to satisfy all his many and varied desires. At birth he had inherited the wealthy territory of Artois on the border between France and Flanders, as his father was already dead when he was born.

Over the course of his early life, he became a ruthless and talented military leader, taking part in many of the wars that were prevalent in the 13th century. He married three times and had several mistresses. This was not unusual, as women were highly likely to die in childbirth. So, based on this brief biography, perhaps you could say that he was a typical aristocrat of the time.

Aberdeen Bestiary – The Wolf

Aberdeen Bestiary – The Wolf But his choice of pets was a real giveaway that he was villain material. The Count of Artois was known to keep a pet wolf, which he allowed to hunt across his lands, eating the herds of the local peasants (hopefully not the peasants themselves). He had a large castle and walled park at Hesdin (now Vieil Hesdin) in Boulogne North East France stretching over eight hundred hectares, which he filled with the most extraordinary attractions. The Count was said to enjoy practical jokes, and his park was designed to freak people out in many imaginative ways. If you’d like to know what it might have looked like, a detail of a painting can be viewed on this website: http://www.medievalcodes.ca/2015/04/the-marvels-of-hesdin.html

We often think that medieval people had little in the way of what we would call ‘technology’. But this was not so. As well as real exotic animals, Hesdin housed automata – skillfully constructed mechanical beings that moved, ‘spoke’ and frightened the guests. In a later set of accounts, these were described as including a talking mechanical owl, caged birds that spat water, and waving monkeys covered in badger fur. I can think of several horror films featuring this kind of thing.

Detail from The Luttrell Psalter, British Library Add MS 42130

Detail from The Luttrell Psalter, British Library Add MS 42130 The park also provided numerous ways of being dunked in water and covered in soot or flour. All designed apparently to amuse, if not the victim, then certainly the Count. The engineers who made these marvels would have employed devices used in both agriculture and the military, and their inventions were to have a profound impact on William Caxton, the first man to run a printing press in England when he visited it in the 15th century.

But I digress. If a story has a villain, it follows that he must get his just deserts. It happened to the Count a few years after the action of my novel, but it was worth waiting for.

Robert, along with the cream of the French aristocracy, rode into Flanders in July 1302, to teach the region a lesson. After two years of brutal occupation and unrest, the people of Flanders had revolted against the French rule in May 1302 and killed many Frenchmen in Bruges. King Philip IV sent in 8,000 men to quell the uprising and put Count Robert II of Artois in charge. But when the two armies met outside the town of Kortrijk (Courtrai) on the 11th July in what came to be know as the ‘Battle of the Golden Spurs’, all did not go as the French had planned.

The French cavalry proved to be no match for the Flemish infantry and their pike formation. In the end, three hundred noblemen of France were slaughtered by the yeomanry of Flanders. In revenge for French cruelty, they took few if any knights prisoner, counter to the usual practice of holding nobles for ransom. Count Robert was one of those to be killed, in a most satisfying and humiliating way.

Battle of the Golden Spurs in Kortrijk 1302

Battle of the Golden Spurs in Kortrijk 1302 Robert of Artois was surrounded and struck down from his horse by an extraordinarily big and strong Cistercian lay brother, Willem van Saeftinghe. According to some tales, bleeding from many wounds, Robert begged for his life, but the Flemish refused to spare him, claiming that ‘they did not understand French.’

This is what the Annals of Ghent had to say about the matter:

“. . . the art of war, the flower of knighthood, with horses and chargers of the finest, fell before the weavers, fullers and the common folk and foot soldiers of Flanders . . . the beauty and strength of that great French army was turned into a dung-pit, and the glory of the French made dung and worms.”

‘Good riddance!’ one can almost hear the fed-up peasants of Artois cry.

(All images Public Domain)

March 27, 2019

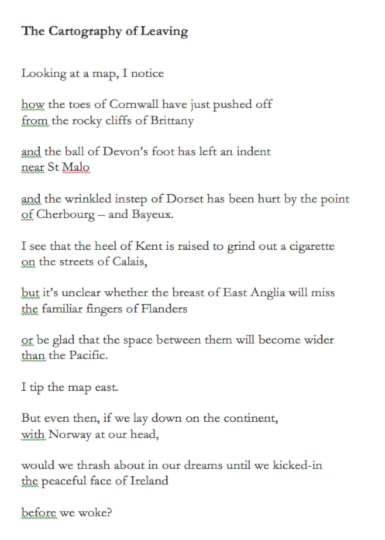

The Cartography of Leaving

It was early December 2018, and I was in Shrewsbury Library filling a rare empty half-hour between appointments. I often gravitate to a particular reading room in that library – covered in graffitied wood from its days as a boys school. Giving in to my fondness for ancient cultures, I chose a book of medieval art and sat down to browse through its pages.

Close to the beginning of the book I found a map of Europe. I looked at it carefully, and the longer I looked at it the more I saw the print of the UK on the coast of France and the other countries along the Channel – and their imprint on us. Geologists have long known that the two land masses were very recently (at least in geological time) connected.

Having trained as an archaeologist, I understand that our island has been host to many groups of people, some coming for peaceful trade, others for violent colonisation. Since we became bipedal, humans have always travelled, always immigrated and emigrated. Borders, even watery ones, are human constructs that cannot prevent natural processes. Work on DNA from ancient populations confirms that people in the UK were diverse long ago, as they are now. This is a strength we have benefited from for millennia. Our technology, commerce, music, art, literature, language – all have been enriched by it.

The longer I looked at the map on that December day, the more the sadness I feel about Brexit became imbedded in the undulations of our coast. It reminded me of the way a long-worn ring leaves an indent on the finger. Or the way hands, used to being held, must curl in on themselves in the absence of the other. This poem is the result, and now is published in the New European magazine, in a week when the members of parliament are set to make decisions that will determine the nature of our borders for many years.

But the fact of our common bedrock remains. We will always be connected, no matter what some self-interested, power-hungry politicians would have us believe.

Kate Innes

Kate Innes

November 9, 2018

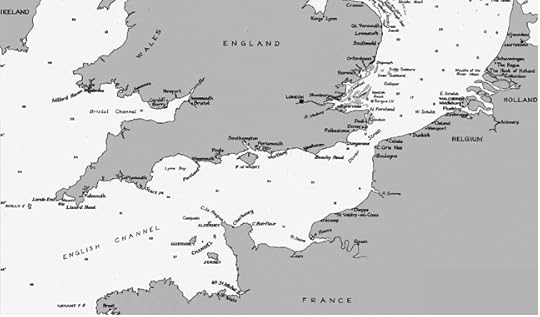

The Historical Novel Society reviews ‘All the Winding World’

I was so relieved. Not only did the reviewer, Misty Urban, say many lovely things about ‘All the Winding World’, but she also happens to have a PhD in Old and Middle English. To know that a medieval expert approved of the world I had created was immensely gratifying.

I owe thanks to the Historical Novel Society who work hard to promote good historical fiction, and to their reviewers who voluntarily give up their time to help authors. They probably know that a good review to a writer is like Christmas Day to an eight year old.

For all the happy excitement you have provided, I thank you reviewers everywhere!

All the Winding World

WRITTEN BY KATE INNES

REVIEW BY MISTY URBAN

Innes brings her poetic sensibilities to bear in this lovely sequel to The Errant Hours, set ten years later. Illesa is married to Sir Richard Brunel, has borne three children and lost one, and is happily settled at their small manor farm in Shropshire when King Edward’s call for war to regain the lost Duchy of Aquitaine summons Richard, despite his maimed leg and missing eye, back to the battlefield. French treachery lands Richard in a Bordeaux prison, and Illesa launches a dangerous scheme to trade a priceless clerical garment for her beloved’s life. Helping her are Gaspar, a witty traveling player carrying a fatal secret, and Azalais of Dax, a skilled trobairitz (female troubadour) trained in the songs of courtly love.

Innes’s accurate details and descriptions of the furnishings and landscape of life in late 13th-century England and France are a pleasure to revel in. She conveys the richly textured sense of a world bloody with war and other hazards, clocked by the rhythms of the natural seasons and Church time, and saturated with that strain of medieval Christian piety peculiar to Western Europe. Though the plot is satisfyingly suspenseful as Illesa drags herself and her friends into the arms of their enemies, the most vivid character is the setting, the buildings and cities that come alive with all their strange accoutrements: priests and Templars, precious books and costly clothing, pet weasels and cunning tax collectors. Innes’s poetry makes an appearance in the songs sung by Azalais, an enigmatic character who deserves her own book. This skillful crafting of and immersion in a brutal, beautiful, breathing world rife with treachery, disease, and dangers unseen will enchant readers new to the period and delight those who know it well.

Details

PUBLISHER

PUBLISHED

PERIOD

CENTURY

Review

APPEARED IN

August 12, 2018

Countryfile – Highlights of Shropshire – follow in the footsteps of medieval pilgrims

The following is an article I was asked to write for Countryfile Online – a lovely magazine reflecting the interests of the BBC Television Programme. It was a great pleasure to put into words just how special Shropshire and the Welsh Marches are – and always have been.

Archaeologist and author Kate Innes shares her pick of the best places to visit in Shropshire – and reveals how you can follow in the footsteps of medieval pilgrims

One of the most famous of all medieval stories is about travel, but perhaps you, like me, have always considered the Canterbury pilgrims to be the exception rather than the rule. Surely it was far too slow and tiring to go beyond the parish boundaries before the invention of the internal combustion engine?

But it turns out that the Middle Ages was a very mobile time, and, although difficult and sometimes dangerous, travel was common and undertaken by every class of person. Horses, mules and donkeys helped. Water travel was often quicker than overland. A journey might even have provided a welcome break from the drudgery of home, as long as there was food, drink and a bed along the way. The inns, taverns and monasteries along the major routes would certainly make sure that there was – for a price.

The gatehouse at Stokesay Castle, Shropshire, England/Credit: Getty

The gatehouse at Stokesay Castle, Shropshire, England/Credit: GettyPerhaps surprisingly, one of the most travelled areas of Medieval Britain was the Welsh Marches, an area now famous for its peace and tranquility; a great get-away from hectic urban living. A bit of research into its turbulent and bloody history reveals a fascinating interlacing of routes that can still be followed today. As a writer of historical fiction set in medieval times, I’ve trodden these paths, and these are just a few of my recommendations for an encounter with the Medieval Marches.

Walk: Acton Burnell, Shropshire

Britain’s treasure map: our guide on where and how to hunt for treasure

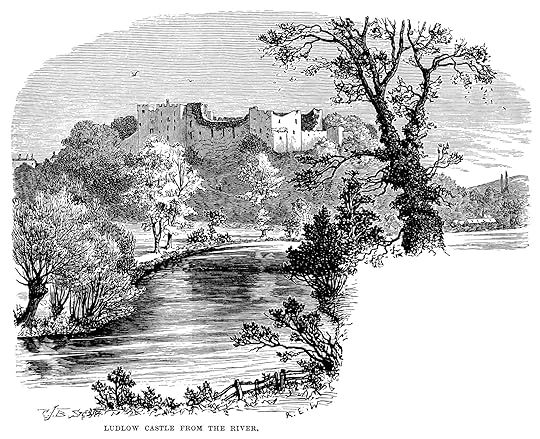

Ludlow Castle is a large ruined fortification beside the River Teme which was built in the 11th century and has later additions. From “Our Own Country: Descriptive, Historical, Pictorial” published by Cassell & Co Ltd, 1885/Credit: Getty

Ludlow Castle is a large ruined fortification beside the River Teme which was built in the 11th century and has later additions. From “Our Own Country: Descriptive, Historical, Pictorial” published by Cassell & Co Ltd, 1885/Credit: GettyTake, for example, the experience of a medieval archer in the service of Lord Mortimer of Wigmore Castle near Ludlow. When war broke out with Wales and his company was sent to Chester, he would have marched north on an old Roman Road, stretching through the Herefordshire and Shropshire countryside, passing the impressive fortified manors of Stokesay and Acton Burnell.

Outcrops on Ragleth Hill and view towards The Long Mynd/Credit: Getty Images

Outcrops on Ragleth Hill and view towards The Long Mynd/Credit: Getty ImagesThe main artery of the A49 echoes the Roman Road through the South Shropshire Hills AONB, with glorious footpaths stretching up on either side. Once you have climbed the Ragleth Hill with its superb views over the Long Mynd, stop at the friendly Ragleth Inn for a taste of true Shropshire hospitality. Afterwards, you may even feel up to another climb. From The Lawley you get a beautiful view of Caer Caradoc, crowned with a hillfort, and the distant, wreathed Welsh Hills.

Caer Caradoc, The Lawley and in the distance the Wrekin, seen from the Long Mynd, Shropshire/Credit: Getty Images

Caer Caradoc, The Lawley and in the distance the Wrekin, seen from the Long Mynd, Shropshire/Credit: Getty ImagesOr imagine the journey of a village woman living in Eaton-under-Heywood, at the base of Wenlock Edge, whose prayers for a successful harvest have been answered. She rides her pony through the Long Forest – a busy place of charcoal burners, coppicers, trappers, and foresters – remembering to be wary of the resident robber baron, Ippikin. At the richly decorated Priory in Much Wenlock, she gives thanks at St Milburga’s shrine.

View from Wenlock Edge, Shropshire/Credit: Getty Images

View from Wenlock Edge, Shropshire/Credit: Getty ImagesNowadays the Jack Mytton Way, a long-distance bridleway, covers the same ground. From Wenlock Edge there are exquisite views over lush Apedale, known in medieval times for its apiaries full of honeybees. There you can enjoy a pint in the rambling beamed bar of one of the oldest pubs in Shropshire – The Royal Oak at Cardington. Much Wenlock is a brilliant base for exploring this area, with intriguing independent shops, the picturesque Priory Ruins, as well as historic hostelries.

The clue is in the name. In the lovely Welsh Marches, the medieval population was definitely not stationary. And the best way for us to experience the area today is by using their slower forms of transport.

All the Winding World by Kate Innes is out on June 22nd (Mindforest Press, £8.99)

Main image: Getty Images

June 25, 2018

A ship leaves port – the launch of ‘All the Winding World’

The old Southampton harbour wall

At the very beginning of writing ‘All the Winding World’, I knew there would be maritime elements in the story. So I popped down to my old University town, Southampton. I didn’t rate Southampton much when I was a student, but now that I’m fifty, I found it was delightful to explore the old town and the docks area, and to have the chance to rediscover all the things I had forgotten from countless lectures: the types of ships that were used in medieval times, the products traded, the building of the town walls because of French attack. etc.

Medieval Southampton before the harbour was enclosed

Medieval Southampton before the harbour was enclosed

I also visited a beautifully reconstructed medieval wine merchant’s house. The multitudinous nature of its walls was astonishing.

Seafaring was very important to the medieval economy and to national security. It could potentially move goods, horses and soldiers faster than any other form of travel. And it was often safer.

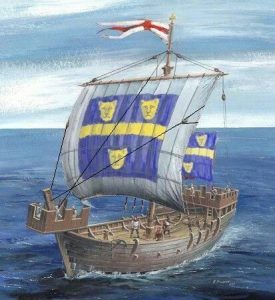

Medieval cog – equipped for war

Close to the beginning of ‘All the Winding World’, a ship of reluctant conscripts sets sail on a fool’s errand to fight for King Edward I in Gascony. The ship is a cog – the workhorse of the medieval fleet. It could hold 12 horses, and perhaps 30 men, plus tonnes of cargo. It had one central sail, and when heading off to war, it would be equipped with platforms fore and aft designed to hold men fighting in battle, or archers shooting at other ships. These platforms were known as castles.

The knights and men-at-arms said prayers to Saint Nicholas before they embarked, as he was well known as patron saint of sailors. The sea may have been marginally safer than the roads, but it was not something to be taken for granted.

I’ve been thinking about the launch of my novel, and wondering if it is similar to the launch of a ship. There has certainly been a large amount of sparkling wine involved, but none has been wasted. I wouldn’t dream of breaking a bottle against a box of books.

I do hope that my book goes to unknown places, and finds new ports and harbours, distant inlets and quays where it can unload the story from its hold.

But thinking about it, each copy of this book is a like a ship, and so what I have done is release a fleet into the world. Each one will be read in a different way, each one will be remembered or forgotten, sailed once or numerous times, passed on or kept and treasured.

This week I had the privilege to share my opinion about other people’s books in The Big Issue , a publication for which I have a great deal of respect. I was asked to select my ‘Top Five Books about Medieval Britain’. It was not easy making such a selection, but I was glad to have the opportunity to share books that have inspired me, and that I feel deserve a wider readership. (Readers, it seems, can be ships too!) I chose Morality Play by Barry Unsworth, Medieval Comic Tales by Derek Brewer, The Hanged Man by Robert Bartlett, Company of Liars by Karen Maitland and The Time Traveller’s Guide to Medieval England by Ian Mortimer.

As our books sail out of their home port, they cease to be exclusively ours and belong instead to the wide world. Each one becomes specific to the reader. The books I selected have taken up a permanent place in my book harbour, as, I hope, All the Winding World may do in others.

You can now buy the sequel to The Errant Hours as an ebook or paperback from Amazon , or directly from me via the Get in Touch page.

June 17, 2018

Waiting for ‘All the Winding World’

As I write this, 500 copies of my second novel are in transit, due to arrive at my house on a pallet sometime tomorrow. I think this must feel a bit like waiting for a prom date, hoping that they have not chosen a really embarrassing outfit to wear, and that they have remembered to brush their teeth! I do know my book, inside and out, but since I pressed send, and it pinged over to the printer, I imagine it could have taken up all sorts of strange habits and styles of dress.

Then I have to give myself a good talking to. The imaginative life can get a bit out of hand at times!

This book is a sequel. If you haven’t read The Errant Hours, All the Winding World will still be understandable and, I hope, enjoyable. But those who are familiar with the thirteenth century world of Illesa, Sir Richard, Gaspar and William, will understand their history and perhaps find that the echoes of the previous book still sound in the story, ten years later.

Along with the old, in comes the new. One of the most vibrant characters I’ve ever had the privilege to write is Azalais of Dax. She emerged from some research I was doing into the trobairitz (female troubadours) of Occitainia. This southern and western area of France was less strict about what women were allowed to do in the early Medieval period. They had more freedom and more power than was usual in the rest of Europe. It was in this culture that the concept of courtly love was born, and women took centre stage not only as objects of love, but as actors in the dramas and creators of songs and poetry in their own right. I came across Azalais de Porcairages, a talented trobairitz from 12th century Provence, and immediately knew that the character in All the Winding World would be named ‘Azalais’ after her. And she certainly lives up to her name!

Azalais de Porcairagues from BnF ms. 12473 fol. 125v

I’ll be talking about the trobairitz and other influences on All the Winding World at Wenlock Books in Shropshire on the 23rd June at 4pm. This slots into a wonderful celebration – Feminist Book Fortnight – that started on the 16th June. I’ll be doing a reading from the book, answering questions and sharing a glass of celebratory Prosecco to launch my book into the world. If you’d like to come along, please contact the bookshop on 01952 727877.

There are several other launch events going on, all listed on the News and Events page . But if you don’t happen to live near Shropshire, you can now order All the Winding World from Amazon or your local bookshop. If you want an ebook, preorder from Amazon and it will be delivered to your Kindle on the 22nd June, which is the official launch date. If you prefer a paperback, you can order now, and it should be with you before the end of the week.

You may be wondering why this novel is called ‘All the Winding World’. Titles are slippery and complex things, in my opinion. But this one is at least partially explained by this song, sung in the book by Azalais. The lyrics were written by me.

“I take the flax, I take the wool

and from the distaff, thread I pull.

I take the yarn, I weave a cloth

made of many lover’s knots.

Around the spindle, I am bound.

My heart, around your heart, is curled.

Like the shuttle, up and down,

like the needle, in and out,

I will seek you till you’re found,

through all the winding world.”

Kate Innes

March 21, 2018

Poetic Encounters #1 – A guest post by Andrew Howe – Visual Artist

Since the start of the year, I’ve been collaborating with visual artist Andrew Howe, as part of the Encounters Exhibition at the Visual Arts Network Gallery in Shrewsbury, which opened on the 20th March. It has been a pleasure to work with Andrew, and to share ideas about mythic landscapes and the fugitive borders between wild and inhabited spaces.

This is the post he wrote about our collaboration. He explores the creative process of working together so well, that there is little I need to add. Only to say that the exhibition is on until the 28th April, full of exciting, powerful visual and poetic work. If you are in the area, I commend it to you.

Poetic encounters #1 Kate Innes

In my post about collaborations, I mentioned that I have been working with three other writers/artists to make work for an exhibition called Encounters that opened this week at the VAN Street Gallery in Shoplatch, Shrewsbury.

The project was the idea of Ted Eames, and it brings together over 20 pairings of visual artists and writers, one artist making work in response to the other’s work. There have been similar such collaborations in the past, but rarely in such numbers I suspect. Having been involved in the installation of the exhibition, I had a chance for a brief preview. I am fascinated by the diversity of work produced, and can’t wait to go back to spend more time absorbing it.

My own work comprises six paintings and collages with Kate Innes and Ursula Troche, and two poems with Paul Baines. Perhaps on first viewing it appears quite diverse/eclectic, but there is a common theme which links everything, although this may not be immediately obvious.

In this first of three posts, I will discuss the work made with Kate Innes.

Of the three pairings, the work with Kate involved the most discussion and interaction in the development of each piece of work. We found many common interests and a similar sensitivity to the landscape and the human history within it.

Kate is a published poet (Flock of Words) and novelist (The Errant Hours). She writes beautifully about the rural landscape, with a knowledgeable eye for the detail of flora, fauna, and geology. There is also a historical/mythical content to her work which clearly links with her background in archaeology and in museum education.

My drawings of abandoned dwellings/cabins were an initial starting point of interest, and in particular, the curious dilapidated structure which I had found whilst walking near Shelton on the outskirts of Shrewsbury.

Kate, too went on foot to visit the place, and like me was drawn to the atmosphere of this small patch of woodland high above the River Severn which can be glimpsed through the trees. A group of people have been using the area as a gathering place and trees are marked with paint, bits of fabric and plastic, like totems. It felt tribal or ceremonial, like an ancient sacred site.

Ceremonial Trees / Bound with fluttering string / Tokens of faint hope (Andrew Howe 2017)

High vantage over / River Severn’s lush meadows / Buzzard soars above (Andrew Howe 2017)

Kate’s poem “The Other Land” captured some of the thoughts that come to my mind in these edgeland places:

“…at the edge of places we don’t belong

…

even the twist of a rope that won’t tie

Or the path that unwinds in a wood

It gathers its strength on a threshold

…”

(Extract from “The Other Land”)

We discussed our responses to these enigmatic isolated and empty structures set in woodland, and explored some of the issues raised in my earlier post around Bachelard’s “Poetics of Space”, the temptations of the “hermit’s hut”, refuge/retreat, and the negotiations that must take place when two people take up residence. The titles of my trio of drawings “When Adam delved”, “And Eve Span” and “Who was then the Gentleman” struck a chord with Kate, referring to John Ball’s speeches that helped inspire the Peasant’s Revolt of 1381. These words relating to equality and social justice resonated.

I went on to develop studies for a painting of the shelter we had been to visit, which responded to “The Other Land” referencing certain features from the poem, like the coppiced trees. These included ipad drawings, a charcoal study and two oil studies:

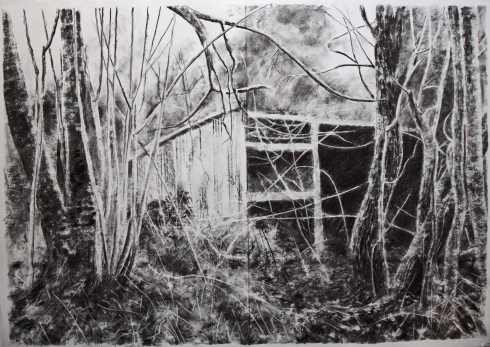

“Shelter”charcoal study, 85cm x 115cm

I made two paintings, quite different in scale and in style. The first was a small acrylic painting made in reverse on an acetate sheet, the second was a large oil painting on canvas:

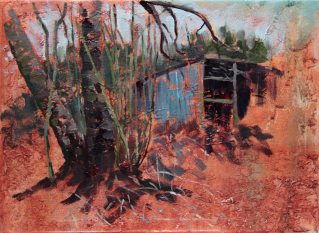

Shelter II, acrylic on acetate, 21cm x 21cm

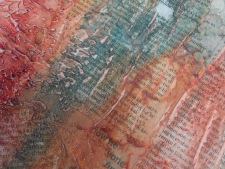

Detail from Shelter II

Shelter, oil on canvas, 90cm x 120cm

I can see flaws that niggle, but in general I’m pleased with the brooding feel to the paintings. There is just enough rawness, texture and painterliness in the markmaking. The brief period for the collaboration (around 3 months) encouraged a disciplined approach and a need for some risk taking.

Kate crafted a poem entitled “Adam’s Return” which responds to Shelter, and also to the trio of drawings, referred to above. To close this short narrative, she drafted a third poem specifically in response to “And Eve Span”. The sparse, measured style and ambiguous timing or timelessness of the poems’ positioning is, for me, reminiscent of the novelist Jim Crace, or perhaps more distantly Cormac McCarthy.

“He found the gate unguarded – except by thorn –

the angel gone

The forgotten trees had dropped their fruit

and multiplied…”

(the opening lines from “Adam’s Return”)

“And Eve Span”, pastel on paper

“...

Here they will live out their days

in a small and private place

intertwined as strands of wool

by twists of love and pain

…”

(Extract from “And Eve Span”)

It was a privilege to see how subtle changes in wording in the few iterative drafts enhanced the poems, shifting emphasis, refining rhythm, suggesting alternative perspectives, picking up on certain aspects of the paintings. The three poems expand meaning and add greater depth to the paintings, and it was a pleasure to be a part of it.

Share this: