Kate Innes's Blog, page 5

June 8, 2015

The Painter and the Poet

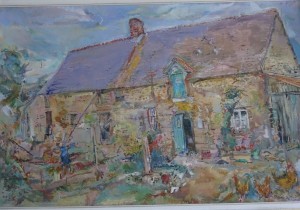

La Missonnais – Ille-et-Vilaine, Brittany by Neville Carlton

This blog post is slightly different from my usual in that it involves a contemporary, or nearly contemporary, artwork. Normally I am entirely preoccupied by centuries old art, but for this artist, I make an exception.

I met him in a poetry writing group which I joined in 2008. Neville Carlton had become a member of the Borders Group in its very early days. He was also a talented artist, trained at the Slade. He died in January this year in his early 90’s. About three years ago he held an exhibition at the Walls in Oswestry, and this painting was there. I bought it from him, having fallen in love with it on first sight.

I think what attracted me is the way in which it teems with life and colour. Every time I look at it, I see something new. I have always liked paintings of houses, and also very detailed things which one must spend time examining and decoding. And as it combines these two interests, his painting has provided me with a great deal of pleasure.

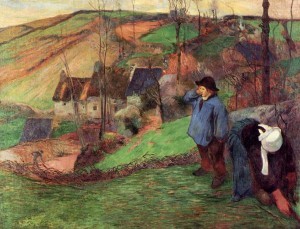

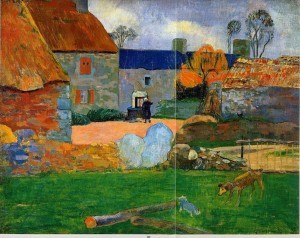

In addition, it has caused me to think about another, very different, painter who spent some formative time in Brittany: Paul Gauguin. I am familiar with his more famous Breton period paintings, but I did not realise how many landscapes and housescapes he had produced while living there. Perhaps there is something about the Breton houses, with their many shuttered windows, and the light of the fields coming right up to their doors, which calls the painter’s eye.

Farm in Brittany – 1886, Paul Gauguin

Landscape of Brittany, 1888- Paul Gauguin

A blue roof farm, 1890 – Paul Gauguin

(In this later painting, Gauguin is using the instantly recognisable colour palate of his mature work)

One day I will have to go myself, and find out.

La Missonnais – Ille-et-Vilaine – Brittany

The old English painter has come

with his hat, brushes, tubes and stool.

Curious, three hens approach

and cock their heads,

but they must wait their turn.

For, while the light falls to the west,

the house is purple and aureolin

with early evening clouds.

Everything in the garden

has reached the height of its verdure

and the day wilts.

The young greens are dulled to sage.

The chimney is the old blood

of hand-made brick

above azurite doors

and bone-white window.

Each stone has its own potion of umber and gold.

The wattled hens and rusty bucket

are carmine by the pump.

Lime bright stones frame the ashy soil

where a woman bends

to the vegetation of the beds.

She pokes and pulls; he brushes and strokes.

Each sets this day into another;

into the half-life of minerals,

wood dust and dividing seed.

Soon the milked cows will low,

lumbering to the meadow,

as they always have,

and the pigeons will stop clawing

the roof tiles and settle to roost.

The moon will fade in cloud,

then brighten in its night

of indigo.

And the painter will have to go

and take this day into his mind’s eye –

into another place – another sky.

Kate Innes

May 7, 2015

Ancient Trees

Old Knobby – from Ali Martin Arboriculture – www.alisonk.co.uk

On familiar paths through the woods recently I have been knocked out of my walking trance by the glaring absence of trees. On four of my favourite routes, widespread ‘harvesting’ operations are taking place, involving indiscriminate destruction of the deciduous trees around the harvesting area, widening the tracks to allow large diggers and cutters, crushing bluebells and other wild flowers and, of course, cutting down hundreds of trees in their prime.

I have plenty of wooden furniture in my house, as many people do. I use paper. I have a log burner. I do understand that many species of trees are grown for timber, and I do understand that farmers and foresters must keep their tracks clear to allow access. My head understands all these things, but the rest of me is unable to accept the results of this economic activity.

Behind my feelings about logging is my belief that these remarkable plants, which are able to create air, beauty and fertile habitats, should be cut down, when necessary, carefully and without collateral damage to other well-established native trees. Areas of woodland beauty, such as glades and wooded tracks, should be considered as more than just the sum of their parts. Specimens of particular importance and age should be protected and not treated as though they were weeds.

Some species, such as sweet chestnut, oak and yew, are capable of living for over a thousand years. Ancient trees in the UK tend to survive in the old medieval forests and parks, or because they were once boundary markers or local meeting places. The Woodland Trust record and protect these trees; these links explain their work:

ancient tree hunt link

what are ancient trees and where to find them

Besides their compelling presence in space and time, old trees are also able to help people understand their own history. Tree ring width can be used as a measuring tool to reckon the age of timbers found in all sorts of intriguing objects including: ships/houses/panel paintings/dug out canoes. These ancient survivors of variable climate and human requirements contain a record of our shared experience.

The relationship between tree rings and the characteristics of a particular year’s weather was first commented upon by Leonardo da Vinci (unsurprisingly) and the many applications of this link were developed gradually over the centuries. The science of dendrochronology is now commonly used to date wooden objects found in archaeological excavations and to calibrate radio-carbon dating. Thanks to the careful work of scientists around the world, there are now several sequences of tree ring data stretching back thousands of years. These sequences show us variations in climate within countries and across continents. They help us to understand the context of human material culture and written narratives. They show us what pressures were at play in the distant past.

Our impact on the environment, our experiences, are also being recorded by the trees growing all around us. But if we keep cutting down trees in their prime, how will these sequences develop? If we do not value and care for the ancient ones, how will we know where we fit into wider history? If trees eventually across the world are principally grown only for timber, will any ancient trees remain stretching back to this time, for our descendants to decode in a thousand years?

The Silton Oak, Dorset from bespoke green oak website

Dendrochronology

From this distance it could be dead –

the trunk crazed, limbs drunk,

sparsely haired, clutching

at its scattered leaves.

Inside the hollow oak, the years’

marbled, directionless lines

stretch, contract – are petrified.

Deluge and drought

and the many steady seasons –

a geological section in miniature.

When I put my hands on the inner rings,

I feel a force – not history, but experience.

How long since it was acorn?

How long till I am oak?

Kate Innes

April 21, 2015

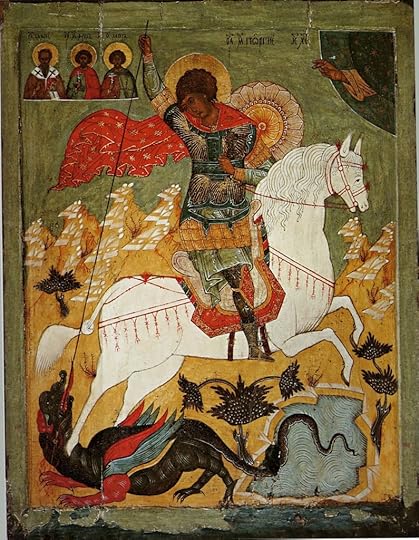

St George and the Political Dragon

St George Kills The Dragon, the St George Legend VI

by Edward Burne-Jones, 1865

Gallery of New South Wales, Sydney

(this dragon looks more like a black labrador, and really didn’t stand a chance, poor thing)

Here in the UK, we are suffering, as many countries are, with election fever. The symptoms are irritating and can become chronic, but here, at least, they are not fatal as they can be elsewhere. One of the annoying things that happens in the lead up to an election is the appropriation of all sorts of cultural capital by politicians looking to emphasise their values and goals.

St George is a case in point: Patron Saint of England, soldier, hero, rescuer of virginal princesses and a Christian martyr. He has been used over the centuries to stand for all sorts of religious and spiritual causes, very few of which bear any relation to the actual person behind the saint.

The facts are few. The earliest story was of a nameless noble-born soldier in the Roman Army who was beheaded by Diocletian for protesting against the Emperor’s persecution of Christians. By the 5th century there was an Apocryphal Acts of St George, popular in the Eastern Church. He was said to have come from Cappadocia (modern Turkey), been raised in Palestine and was a tribune in the Roman army. As a saint, he was particularly admired for his defence of the poor and persecuted.

Icon of St George from 16th century Crete – portrayed as the victory bearer,

with the symbols of the horseman in the book of Revelation

The Acts of St George also had him visiting Caerleon (in Wales, see my previous post) and Glastonbury when he was in the Roman Army. The Acts were translated into Anglo Saxon in the 8th century, and from then on St George’s popularity in England grew, reaching its climax in the period during and just after the Crusades. He was said to have appeared to the Crusader army at the Battle of Antioch in 1098, and many similar stories were passed on from the Byzantine army, reaching eager ears in the West. When King Richard I was crusading in Palestine in 1191-92, he put his army under the protection of St George. So far so good. He is set up to be a real hero in the military mould.

But where’s the Dragon? What about the beast?

As is the case for so many of the best stories, it seems the legend was a conglomeration of an Anglo Saxon myth, a Greek myth (Perseus and the sea monster) and allegorical language (about the villain, Emperor Diocletian). The version we see in most representations is St George rescuing a Pagan Princess in Libya, who was being sacrificed to placate a terrible dragon which had set up its base at the water source of the city. St George killed the dragon, saved the princess (or in some versions tamed the dragon, which the princess then led around on a chain like a dog) and converted all the residents of the city to Christianity.

St George and the Dragon from Lady Margaret Beaufort’s Book of Hours

French, c. 1440, St John’s College, Cambridge

This dragon seems very cooperative about being skewered!

But it was his military credentials that interested the people in power. In 1348, George was adopted by Edward III as principal Patron of his new order of chivalry, the Knights of the Garter. It was around this time that he was declared Patron Saint of England, when the King was hoping to get another Crusade off the ground.

In 1415, the year of Agincourt, the Archbishop declared St George’s Day a great feast and ordered it to be observed like Christmas Day. Much later during the Blitz of London in 1940, King George VI instituted the George Cross for ‘acts of the greatest heroism or of the most conspicuous courage in circumstances of extreme danger’.

St George is still venerated in a large number of places. He is the patron saint of Aragon, Catalonia, Georgia, Lithuania, Palestine, Portugal, Germany and Greece; and of Moscow, Istanbul, Genoa and Venice (second to St Mark). He is patron of soldiers, cavalry and chivalry but also of sufferers from leprosy, plague and syphilis.

So when a would-be MP and leader of the UK Independence Party, fired up by patriotic zeal, declared that he would turn St George’s day into an English holiday if he were in power, I hope he realised what he was advocating. This smoking, drinking, anti-immigration party leader who is said to be ‘partial to crumpet’, might do well to think again.

http://www.telegraph.co.uk/women/womens-politics/10691999/Nigel-Farage-may-be-a-cheeky-chappy-but-Ukips-sexism-is-no-laughing-matter.html

http://www.ukip.org/nigel_farage_announces_pledge_to_make_st_george_s_day_a_bank_holiday

(do have a look at their policy page!)

Nigel Farage might like to think that he is the modern-day St George, protecting England from the threats all around it. He might like to imagine that he is being brave in standing up to the establishment. He may assume that St George would be right behind him. But St George came from Turkey and Palestine. So in actual fact, if UKIP were in power, St George would never get into the country.

However, when I read UKIP’s policies, it did strike me that Nigel Farage is very much like another character in the legend of St George . . .

A Political Animal

I’ve always liked to slake my thirst

so no more price per unit.

There’s no harm in tobacco smoke

the NHS can cure it.

There’s plenty of cash in my hoard underground

so for God’s sake, let’s get fracking!

Global warming will suit me fine,

we’ll send all the refugees packing.

We can sit on our wealth,

toasting our health

and

I’ll make bloody sure

we give none to the poor.

(Especially not to those we strand

over in Bongo-Bongo land*.)

So all the virgins who relied on St George

to save them from being roasted,

say a prayer, I’m about to gorge

cause I like my crumpet toasted.

The EU hordes will run in fear

from my pint and fag bandwagon.

So watch out all you bleeding hearts,

I’m Farage, the English Dragon!

Kate Innes

* Godfrey Bloom, a UKIP MEP, said that Britain should not be sending aid to ‘Bongo Bongo Land’ in August, 2013

(fag= cigarette in this context, for those reading in other countries!)

April 10, 2015

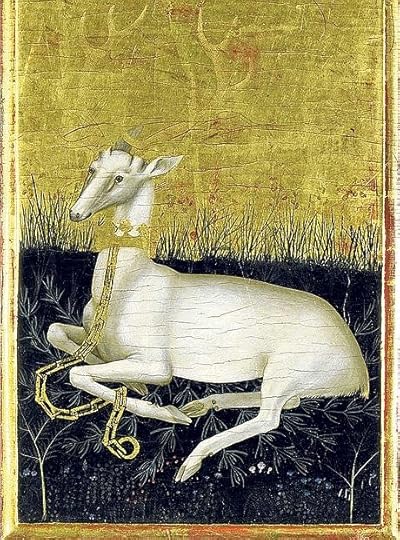

The White Hart

The White Hart from the Wilton Diptych,

created for Richard II, 1395-99

The National Gallery, London

(this painting shows a tamed white hart; only a King could achieve it)

Said to be a symbol of the pursuit of spiritual knowledge, ‘The White Hart’ also happens to be the fifth most common pub name in Britain.

Spirits of a different kind being pursued, one concludes.

The white hart was a common element in Celtic mythology, a messenger from the other world and the starter of quests. It was said to be the creature that could never be caught. In most stories it caused a profound change in the physical and spiritual state of the viewer/pursuer.

Visions of a white stag compelled King David I of Scotland to create a shrine to the cross, the holy rood, now a seat of power in Edinburgh, and a white hart crowned with a cross showed St Eustace that his fate would be to suffer as Christ had done. Richard II chose the white hart as his heraldic emblem, inherited from his mother Joan, the ‘Fair Maid of Kent’. It’s purity and power lent him some much needed credibility in his numerous struggles with his rebellious and resentful subjects.

The White Hart emblem on the angels surrounding the Virgin and Child

Wilton Diptych, 1395-99

(the angel on the right looks really bored by the whole thing)

It is an interesting thing, this equation of a white colouration with supernatural powers and purity. The phenomenon is actually the absence of pigment, or Albinism; an hereditary condition common to animals of all kinds, as well as plants, generally producing white hair and pink eyes in mammals, occurring, on average, once in every 10,000 mammal births.

Whereas humans find albino animals special and accord them a particular positive significance, the same cannot be said of their treatment of human albinos. Instead, these people are often disadvantaged socially as well as suffering from the effects of a lack of melanin. They may be ostracised, scapegoated, or in the worst cases attacked and killed. (It is reported that there have been many recent attacks on albinos in Tanzania and Burundi. Some are being kidnapped and killed because their body parts are thought to make a particularly potent muti – medicine http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Persecution_of_people_with_albinism). Difference, in these cases, causes superstition and fear, and becomes an excuse for depravity.

In the myths and stories of the white hart, it is portrayed most definitely as the other, the powerful thing, hunted for the potency and status that it will confer on the hunter. But nowadays, I believe it also contains another meaning. The Britain of wide-ranging forests full of wild game and animals, the setting for quests, fairy-maidens and honourable thieves, is gone. A construct always, promoted by playwrights and poets, but one which expressed something about what was fundamental to our culture and society. We cannot pretend that it exists anymore, because, for the vast majority of the population, the fabric of the land has been transformed by tarmac, brick and large scale agriculture. Wildness is accessed almost exclusively through the tv screen.

But sometimes wildness, graceful, breathtaking, otherworldly wildness, breaks through our managed landscapes, either in our imaginations or in real time. The white hart, a rare and beautiful sight, shocks us into a state of wonder. A few years ago, when I saw one on my morning walk trotting up the ploughed hill through morning mist, it was a sight not reducible to genetic fact or weather conditions.

I think it is this aspect of the ‘White Hart’ which TS Eliot invokes when he wrote ‘Landscapes III -Usk’ http://www.nbu.bg/webs/amb/british/5/eliot/landscap.htm although it is possible that he referred to the public house, The White Hart in Llangybi, Usk, behind which was an old, whitewashed holy well http://www.theguardian.com/uk/2003/aug/06/highereducation.books.

Usk is near Caerleon, the fabled centre of King Arthur’s court in Welsh myth. Eliot’s poem is ambiguous and grammatically difficult, taking the quoted line from a play by George Peele The Old Wife’s Tale (late 16th century) http://www.poetrynook.com/poem/gently-dip-not-too-deep.

This poem of mine is a Gloss or Glosa on Usk. The Glosa is an old Spanish form which sets its task to explain the lines of an older, more famous poem. Explanation is not achievable, but my poem could perhaps be called a variation on Eliot’s theme – a third generation poem in pursuit of the white hart.

If you hope to find

The white hart behind the white well.

Glance aside, not for lance, do not spell

Old enchantments. Let them sleep.

‘Gently dip, but not too deep.’

The light that water casts on leaves,

the lips bent low to drink, the sacred dell.

Beyond the hedge of mist and tangled trees,

the white hart behind the white well.

Watched from some unhappy land

where many hear but do not tell,

old tales gasp, springs turn to sand.

Glance aside, not for lance, do not spell

out your lonely needs on these stones,

conjuring a new hero in his keep,

or a King riddled by his throne’s

old enchantments. Let them sleep.

But go along the branching road

and find the fields, the hart’s high leap.

And when you find your spirit’s spring,

‘Gently dip, but not too deep.’

From III Usk, ‘Landscapes’, T.S. Eliot

Kate Innes