Kate Innes's Blog, page 4

November 17, 2016

Imagined Worlds – Coleridge and Kublai Khan

As a young person, I was very fortunate to have an excellent education. However, I fear it was a bit lacking in regards to Samuel Taylor Coleridge. I went to an American school with a very good English Department which helped us read Philip Roth, John Donne, James Joyce, Tolstoy and Dostoyevsky, as well as Shakespeare and Wordsworth. But, the only thing I remember about Samuel Taylor Coleridge from my school days was the first lines of his shorter poem ‘Kubla Khan’.

I certainly didn’t know that Xanadu (Shangdu) was a location in China where the Mongolian grandson of Genghis Khan (Kublai Khan) held his summer court.

Nor had I heard the story surrounding the poem, how, during an illness in 1797, Coleridge had been reading an account of travels in the East ( Purchas his Pilgrimes ) based on the writing of Marco Polo, and, having taken opium for his pain, had a dream in which a poem wrote itself in complete and beautiful unity about the Khan and his palace. Upon waking up, he was interrupted by a man from Porlock who took a whole hour of his time, by which point most of the inspiration had dissipated like mist, and all he could save was a couple of stanzas. This was the kernel of the poem ‘Kubla Khan’, which was published, years later, in 1816.

The Friends of Coleridge, http://www.friendsofcoleridge.com are an organisation set up to promote and celebrate the work of this prodigiously talented and troubled writer, who lived in Nether Stowey in Somerset for part of his writing career and wrote many of his most famous poems there. This year they created an ambitious project to celebrate the bicentenary of the publication of ‘Kubla Khan’, involving west country artists, schools work, walks, film, a commemorative booklet and a poetry competition on the theme Imagined Worlds, all sponsored by the Arts Council.

This is where my writing story and Samuel Taylor Coleridge intersect. Many years ago, during a Welsh holiday, I went for a walk and whilst looking at a cloudswept evening sky and the birds scattered across it, the phrase ‘flocks of words’ came into my mind. I knew it was a poem, and that the concept of words disappearing for periods of time, like birds, was worth exploring. But I didn’t realise how long I would be writing it for! As far as I can tell, my first draft is from 2009. By the time I heard about the Imagined Worlds Poetry Competition, it had been through countless changes. And in August 2016, just before another Welsh holiday, I felt it was finally ready to fly the nest. I sent it off to the competition minutes before we locked up the house for two weeks and set off for the coast.

It was a tremendous surprise and a great pleasure to be told in October that ‘Flocks of Words’ had won the competition, and that the poem would be on display alongside the works of art, curated by Jon England and Somerset Art Works, at a special presentation evening in the CICCIC in Taunton, where all aspects of the Kubla Khan Imagined Worlds Project would be celebrated.

It made me consider how my poem and the work of Coleridge might be linked, and what I could learn from this new connection. In adulthood, thanks to a moving story by Michael Morpurgo, Alone on a Wide Wide Sea, which I’ve listened to several times with my children, I have come to know quite a lot of the ‘Rime of the Ancient Mariner’. Immediately upon hearing the good news about the competition, the albatross came to mind.

Coleridge, evidently, was a man who knew a great deal about both words and birds. The wandering albatross, with its benign and interested expression, stands for so much in the story: identity, humanity, divinity, hope. Birds go between different worlds. For millennia they have been considered messengers, linking us to another world beyond our view. They can bear the weight of considerable symbolism, and I enjoy writing about them very much.

And I have learned subsequently that Samuel Taylor Coleridge was a great walker, thinking nothing of a twenty-two mile round trip to Taunton to attend church. He spent much of his time on foot, and therefore the series of walks and the Coleridge Way in Somerset celebrating him are very appropriate. I cannot claim to be a great walker, but I’m a regular one. And I cannot imagine being a writer without my daily walks. Walking provides the rhythm within which thoughts can sing. Inevitably, if I am stuck with a plot or a poem, a walk of an hour or more sorts it out. Body and mind inextricably linked. Make one move, and the other joins in.

It has been a surprise to discover that, like me, Coleridge worked briefly in Shropshire. In December 1797 (the same year he wrote ‘Kubla Khan’), he arrived as locum to the Shrewsbury local minister, Dr Rowe, in the Unitarian Church on the High Street – a building I walk past almost daily. He is said to have read the Rime of the Ancient Mariner at a literary evening in Mardol, Shrewsbury. Coleridge was considering a career in the church at this point in order to alleviate his financial problems, but when Josiah Wedgwood offered him an annuity to keep writing, he abandoned his ministry plans.

So, with all these common points of reference, I am now determined to get to know Samuel Taylor Coleridge better. He seems a man with whom I could happily spend many hours, and I am honoured that my poem will now be in some way associated with his vision of a world both celestial and worldly, beautiful and terrible, vivid and fading from view.

The ‘Kubla Khan’ exhibition, and with it my poem, are on the move. They travel to Bath and then on to Nether Stowey (looked after by the National Trust). You may not be able to see the artworks or go on the walks, but here is my poem. It has come home to roost.

Flocks of Words

Imagine a country where words were like birds

and flew away surreptitiously,

migrating for whole seasons, leaving one bereft

of noun, verb and preposition.

It begins in autumn when scientific names fly free.

Binomial pairs depart, fast and wild,

and taxonomic flocks coalesce

into Greek, their deltas pointing far away.

Soon all common things become obscure

like the unseen stars at the edge of space,

and in the thrumming fields and naked gardens,

it is like Eden before Adam spoke.

Imagine visiting that land in the spring

and watching the words return,

grown fat with the food of foreign meanings,

their syllables strange to the tongue.

I could enjoy a season unnamed and free,

surrendered to instinct or god’s purpose.

But then I’d watch for its approach on tired wings,

and feel the weight of it alighting on my breast,

and put it on, like fresh plumage or a newly laundered dress.

Kate Innes

May 25, 2016

A Varied Diet: Publishing the Unexpected

Recently I was given the opportunity to contribute to a Novel Writing Course run by the immensely talented Lisa Blower (author of newly published novel Sitting Ducks). I was invited to talk about writing The Errant Hours, and especially about my decision to self publish. There were many very insightful questions from the writers in the audience, all at the beginning of their career, attempting to understand an industry which is in a state of constant flux.

Revisiting my journey to publication has made me think about it with more objectivity and less emotion. It was sobering to see how far I’d travelled from the naïve writer who began Chapter One in 2010. A change similar to that experienced by the heroine in my story, but effected mainly through psychological challenge rather than physical violence.

When I began my novel, I believed that if I could write a good enough story it would inevitably be published. The trick I needed to learn was how to write convincing, well-rounded characters and follow them into their lives. This took a long time. Getting the descriptions to sing rather than scream seemed to require banging my head repeatedly with my fist. Structuring the story was another hurdle. There was a good deal of trial and error, diagrams, long walks and shouting involved in getting all the elements of the plot to fit together.

Finally, I needed each sentence to flow into the next. It was important to have the right words both rhythmically and meaningfully. Five years of pulling words out of my brain, looking at them, discarding them or hammering them into different sentences, and at last I felt the book was finished. What I did not realise was that I’d left out the most important ingredient as far as the modern publishing industry was concerned.

I wrote a story about a period that interested me: the Plantagenet era, at the time of Edward I and his series of battles with the Welsh. I wanted to write about the effect of endemic violence on the lives of ordinary people. There have not been enough stories about that topic, in my opinion.

I live in Shropshire, which is now seen as a sleepy rural backwater. At the end of the 13th century, Shropshire was a centre of military and political power. It was the family seat of the second most powerful man in the kingdom, Robert Burnell, the Chancellor and Bishop of Bath and Wells, a priest who had many illegitimate children. Robert Burnell was a very interesting contradictory character in my view, and worth exploring.

Acton Burnell Castle – home of Chancellor Robert Burnell who was given permission by Edward I to crenellate his manor in AD1284

But not interesting enough, I was told. The whole of the Medieval era, according to the expert I consulted at the Author’s Advisory Service, was not popular, and therefore it was totally the wrong period to write about. I should have chosen the Tudors. At a pinch the Romans, Victorians, or Georgians would have been okay. But Medieval was a no-hoper.

There was nothing I could do about that. Ever since I was a young girl, I have been a lover of the medieval aesthetic – its buildings and culture. I was sure that the medieval period was worth writing about. I did some research on-line. Thousands of people seemed to be interested in things medieval. There were tens of thousands of Twitter followers and members of medieval Facebook groups. medievalists.net

Detail of the margin of the Romance d’Alexandre, Bodleian library MS 264

After all, the medieval period brought us the iconic castles that represent Britain for tourists. It had brought forth the legend of King Arthur and his (sometimes) virtuous knights. And during the 13th century, the first Bill of Rights for individuals had become law.

I did become hopeful in 2015. I thought the 800th anniversary of signing of The Magna Carta might change the prejudice against publishing medieval. But in July of that year, I was still getting polite letters from agents praising my writing but telling me the story was not for them.

Then I received a particular letter, from Anne Williams at the Kate Hordern Agency, which spelled out the problem very clearly. There was nothing wrong with my writing, but “without a more obvious historical hook which a publisher could hang their sales pitch on (eg a particular, relatively well known historical character or conundrum) they would struggle to see a convincing way in which to publish.” And she added “If you should decide to write something more along the lines I’ve outlined I’d be happy to consider it.”

I am very grateful to Anne Williams for taking the time to explain this so clearly. It is rare for agents to reveal their reasons for rejection.

It was clear to me from that moment on that if I wanted this story to be read, I would have to publish it myself. I did need help along the way and would advise anyone thinking of independent publishing to hire a graphic designer and a copy editor at the very least. But the main work of publishing was mine.

Now The Errant Hours is available widely, as an ebook and paperback. In theory, anyone around the world with access to a computer can order a copy. I am receiving feedback every day from readers who have enjoyed the journey into medieval Shropshire, and who are recommending it to friends. Over 700 copies have been sold, and I have lost track of the number of people who have said that they didn’t think they liked historical fiction, but they loved The Errant Hours. Also, very importantly, I have maintained the integrity of the story and all my rights to it. I am still a long way from breaking even on my costs, but things are off to a good start.

‘The Errant Hours’ travelling in Japan

This post is not really about self publishing, however. It is about the current assumption in the publishing industry that we should give people only what they already think they want.

A parent of a young child is encouraged to make sure the child eats a variety of foods, sweet, bitter, salty and sour – different textures and tastes so that their palates develop, and in the future they eat a broad range of dishes and enjoy good health.

Using this analogy, the publishing industry seems to be behaving like a parent who only gives their child chicken nuggets, chips or pizza, because that is all they seem to want to eat.

Before we taste variety, we don’t understand all the different and delicious possibilities of taste. Before we meet people from different countries, we don’t understand how things can be seen from multiple perspectives. Before we read about a new place or time, we do not know whether it will interest us or not.

There is always the possibility that it could fire us up and change our lives. But if we are only ever provided with the topics and periods that are popular, we will never have the chance to explore the intrigues and treasures of these under-represented periods, the hidden inglorious and surprising moments of history.

So my question is this: Shouldn’t the reading public be treated as rounded people, open to new experiences and hungry to discover new places, people and times?

If not, we writers are operating under a de facto censor, and readers are being deprived of variety in favour of an easy sell.

The novice writers I met in the course last week do want to write books that sell. They would ideally like to make a living by writing. This has become less and less possible. The income of the average writer is at an all-time low. If those new writers don’t take the advice to write something ‘commercial’, it will be very difficult for them to make any money at all.

Self publishing is not the solution for everyone. You have to have a considerable amount of money up-front to invest in your book. And it is an extremely demanding work model, in which the writer must morph into the PR, distribution, logistics, accounts, marketing or press department at any moment.

If a writer must write according to the dictates of the industry in order to make a living, many will not be able to choose to follow their writer’s heart. And it is the literary health of this country that will suffer.

‘The Errant Hours’ – touring with a reader in Turkey

April 27, 2016

The Hours – two writing paths intersect

I wonder if you have read ‘The Morville Hours’ – a beautiful and precious book, as intricate and finely tended as the garden it is based on. Set in Morville near Bridgnorth in Shropshire, it is just a few, very picturesque, miles from my house. The author, Katherine Swift, once worked in Oxford as a rare-book librarian before turning to gardening and writing full time.

Our books are very different. Hers is non-fiction, based on the development of an intense relationship with the garden at the Dower House and the framing history of its landscape. Mine is fiction, based on a life of fantasy and obsessive medieval research.

Katherine Swift has written a meditative, fugue-like book, in which each separate garden room is like a beautifully enameled bead on a necklace. I have written an adventure that goes at full tilt, headlong through a hostile landscape and all sorts of danger.

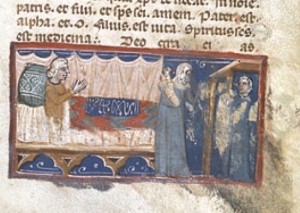

The Smithfield Decretals – BL Royal MS10 E IV 1300

But thinking about it a bit more carefully, I believe there are a few common links between her book and mine, in addition to the more superficial ones, such as the word ‘Hours’ in the title and the general geographical location.

There is the intense interest in the way that dividing up a day into the offices of the church (the Hours – such as Prime, Matins, Vespers, Compline etc) can help one to think of time as something that needs tending through proper, careful attention.

In ‘The Errant Hours’ the protagonist, Illesa, must leave her home, and with it, the ordered life of farming and prayer. Her hours have become wayward and time runs together faster and faster once the boundaries are gone, in an exhilarating and terrifying race. In ‘The Morville Hours’, there is freedom and intensity inside the structure of the day as the life of the garden becomes ever more intertwined with the writer’s life, and history with the present day.

And, speaking as one admirer of ancient manuscripts to another, there is the understanding that reading a unique illustrate book, written long ago, painstakingly, by hand, can feel like picking a variety of fruit and blooms in a sunny, walled garden.

Isabella Breviary, Southern Netherlands (Bruges), late 1480s British Library, Additional 18851, f. 13

But I digress. The main point of this post is to tell you that I am going to be at the Morville Festival on Bank Holiday Monday, the 2nd May, right next to the garden about which ‘The Morville Hours’ was written.

Anna Dreda of Wenlock Books has invited me to sign copies of my book in the tea tent (yay!) which I consider a delicious privilege. There is a Fete and a fancy dress competition, as well as the stunning garden and flower festival in the church. And there is cake! Lots of cake!

If you come, you will not be disappointed.

February 10, 2016

The Story Behind the Story

The Story behind the Story

(This was originally written as a guest blog for ‘The Story behind the Story’ by Dr Gulara Vincent)

I recently became an independent author, publishing The Errant Hours, an historical novel set in the 13th century.

The process has been rather similar to childbirth, but with a lot more coffee and alcohol.

In fact, it was giving birth that profoundly changed me, allowed me to write more freely and engendered this medieval tale. At least that is part of the story.

The other part is about adoption. For most people reading The Errant Hours, it is a fast-paced medieval adventure. But for me it is an exploration of what it is like to long for a child, and to bring up a child who is not yours by birth. And it is about the passion and danger of bringing a baby out of yourself.

My husband and I tried for children for a long time before deciding to adopt. We felt very positive about adoption, generally and specifically, because my father was adopted as a baby.

And we went into adoption with our eyes open, as a GP and a teacher. We felt we knew roughly what to expect from children. After all the necessary hoops were jumped through, we were very lucky to be able to adopt a beautiful four-month-old baby girl.

How different it is when you are a parent; how much better and how much worse!

The powerful love when you are caring for them and watching them grow, and the despair when things do not go the way you expect or demand.

Undaunted, we adopted again, a boy this time, also four months old. We had excitement and exhaustion in equal measure. It was a great gift to us, being parents of these two wonderful children.

Then when James was one year old, I noticed I was feeling quite odd.

Not myself.

Weak and a bit sick.

And so, there it was. I was pregnant. After the disbelief and joy, I was scared.

How would I cope with three children under four years old?

Was I too old for it to go well?

How would my body and my mind manage labour?

And my fears on the last point were not unfounded. The labour did not go well. It dragged on and on for days, making me sick. I had to be put on a drip. I had to be induced. At one point it seemed the doctors were about to rush me to theatre.

In the end John was born, whole and well, and I was left feeling that somehow victory had been snatched from the jaws of defeat, and life from the mouth of death. It was clear to me that if I had lived at another time in history, I would have died in labour, and my baby boy with me.

The incredible feeling of having brought a life into the world, and for it to have been so great a challenge, so close a brush with death, set me on the path to write about a time when childbirth was the most dangerous of all activities. I was interested in it physically (what herbs were used to ease labour?) and spiritually (how did people prepare for childbirth, and how did they cope with the death of their babies?).

I had studied archaeology at university, so I was used to digging into the habits, beliefs and messy remains of past cultures.

I was researching the practices of midwives in the birthing chamber on-line, when I came across it. British Library MS Egerton 877 – The Passio of St Margaret, 14th century. I read the translation of the text, I read the fascinating explanation of the manuscript and I knew straight away: this was the touchstone of my story, this special manuscript. https://www.bl.uk/catalogues/illumina...

In medieval times saints were appealed to for all manner of problems. Usually they were given job descriptions based on the stories of their martyrdom or miracles. Many people know of St Jude, the patron saint of lost causes, and St Christopher the patron saint of travellers. Well, St Margaret of Antioch was the patron saint of childbirth.

According to the legend of her martyrdom, Margaret was a virgin saint in the early 4th Century AD, who had converted to Christianity against the wishes of her father, a pagan priest. She was abducted by the Roman Governor, who wished to ‘marry’ her. She refused. He had her tortured in numerous gruesome ways. While this was going on, she was attacked by the devil in the form of a dragon. The dragon swallowed her, but when she made the sign of the cross it burst open and she came out ‘unharmed and without any pain.’

It was this line in the manuscript that immediately struck me ‘illesa sine dolore’. The word ‘illesa’ is medieval Latin meaning ‘unharmed’, and it became the name of the heroine of my book.

The legend says that, before she was beheaded, St Margaret promised safe childbirth to those who read the story of her Passion. And so books telling of the horrible torture of a virgin became a birthing aid. The number of such books penned in the Middle Ages was innumerable. We can get some sense of how popular St Margaret was by the number of churches and other buildings dedicated to her. But this small well-worn Passio is a rare survivor of the change in birthing practice from the Renaissance onwards.

The manuscript’s illustrations, particularly the one on the final page, depicting the saint standing with hands raised, are also of great interest.

British Library MS Egerton 877 folio 12

This is my description from The Errant Hours:

“Whenever Illesa opened the book of the saint, the feeling was always the same. She became a hawk lifted high in the air, and with the hawk’s eye she could see the sparrow in the hedge and the fearful beasts at the edge of the world in an instant, and all the detail of their beauty and horror.

But the last picture in the book disturbed Illesa. The image of the saint was smudged, and the features of her face were like a reflection seen in the water at the bottom of a well. Ursula said that many women had kissed the saint, smearing the paint in their devotion, for as she had come out of the dragon’s belly unharmed, so Saint Margaret had the power to bring forth healthy infants and spare the lives of their mothers.”

I found it very poignant: medieval women, in their time of great pain and danger, kissed this painted image and sent up prayers to St Margaret to save them and their babies. I began to imagine these women, especially those giving birth for the first time.

And the plot began to take shape, the story of the mother and the daughter, and the story of a sacred book, believed to have the power of life and death.

Of course I realised that a great number of women did die in labour, and the babies who were born into these situations would be raised by others. More of the plot began to take shape in front of me, like a beautiful picture being drawn before my eyes.

So this was where the story began, and it is also where it ends. The book of St Margaret is passed on to another mother; to read, to bless and to make intercession for those in pain and grave danger.

The Passio of St Margaret ends with this entreaty to the unborn child.

“Come forth. If you are male or female, living or dead, come forth for Christ summons you, in the name of the Father, and the Son, and the Holy Spirit, amen.”

(translated by Prof. John Lowden)

Now that my book has been brought into the world, I hope its readers will see something of the courage and strength of medieval women, and all those women living now, around the world, giving birth with little or no medical help. And the powerful hope and desire they have for their children to come forth whole and unharmed.

Kate Innes

October 7, 2015

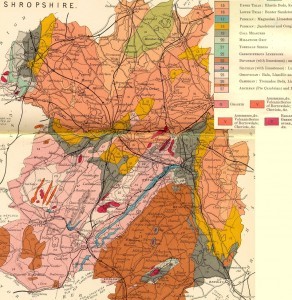

Walking the Hills

Shropshire Hills – The Lawley from Caer Caradoc with The Wrekin beyond

Earlier this year I received a commission to write a poem for a hydro-geologist, for his birthday.

I was very glad to be asked, but this in turn made me ask myself:

‘What kind of poem would a hydro-geologist enjoy?’

‘What really excites them?’

and finally ‘What do I know about hydro-geology?’

The only question I could answer was the last one, and the answer was ‘Hardly anything.’ But fortunately Shropshire has more hydro-geologists than you can shake a stick at. There was advice at hand and resources aplenty.

My first port of call was the Geology Gallery at the newly refurbished Shrewsbury Museum and Art Gallery link. I love this museum. It was opened in 2014, and is thoughtfully presented and designed. The Geology Gallery not only has beautiful specimens of rocks and fossils, but also commissioned art and a wonderful video showing the voyage of Shropshire.

It turns out that the reason there are so many hydro-geologists in Shropshire is that it has an extremely diverse range of geological strata both in age and rock type.

Add to that, in the words of the Shropshire Geological Society,

‘its frontier position: at former plate boundaries, just below the major erosion surface of the crust prior to opening of the Atlantic Ocean, and the meeting point of several glaciers during the last Ice Age. Thus the variety of geological settings is unmatched within the British Isles or, within such a relatively small area, probably anywhere else in the world.’ http://www.shropshiregeology.org.uk

Stanford’s Geological Atlas (Woodward, 1914)

Shropshire has, in its 500 million year history, travelled from a location south of the Tropic of Capricorn in the Southern Hemisphere 12,000km to where it is today. In that time it has been volcanic, forested, tropical, desert, shallow seas, and now the temperate landscape of hill and field, a patchwork embroidered with hedge and forest.

Armed with this new information, I walked up one of my favourite hills: The Lawley. Looking south from the Lawley, one sees Caer Caradoc thrusting through an ancient fault line running in Pre-Cambrian rock northwards to the Wrekin. Around the Lawley spreads the intricate complexity of the countryside, rising and falling, growing and dying. Under my feet was living rock, full of the signs and scars of its journey. And growing from it, the most delicate and hardy of flowers, heather, and the lichens, airy and brittle versions of the languid seaweeds fossilised nearby.

Ordovician Bryozoan from the Caradoc Series

www.discussfossils.com

Afterwards, it did not take long to write the poem, and then, having heeded the advice of poets in my writing group, I delivered Walking the Hills to the person for whom it was written.

But a little bit like Shropshire, Walking the Hills had further to travel. I submitted it to the WriteScience Poetry Competition poetry of science and it was selected as one of the six finalists. I was sent to the Minton Library in Stoke-on-Trent to read it and celebrate the symbiosis of art and science at their Fun Palace festival. ceramic city

Stoke-on-Trent, aka The Potteries,

was just the right place for the poem to arrive,

a place built on special rock and soil which is made and remade,

heated and cooled, used and discarded.

Walking the Hills

“I distinctly recollect the desire I had

of being able to know something about every pebble

in front of the hall door.” – Charles Darwin

On this illusion of solidity

continents have crunched their bones,

inner earth has spilt its heat.

The scar is this graveled spine of hills,

sweetly covered in mossy, heathered coats.

The Lawley rises to a ridge,

that points to future sky.

Caradoc follows, glancing back.

From here we are travelling north

by a fingernail’s width each year,

the millennia trailing after us,

scattering rocks across the world.

The ground beneath our feet

has flowed and frozen and thawed

into lichen puffs and flowered grass.

We continue on our path,

finding the pebbles, gazing at their souls,

as if they were the events of our lives,

as if they were maps for us to follow.

They tell us deserts have turned to stone,

been built and fallen into ruin.

Bogs have sucked and squeezed to coal.

Rivers have redrawn the world

sending out their ribbons of mud,

their rippled sediment.

Everywhere trace prints

and carapace remain –

space-gathered

animate elements

pressed in layered pages.

We walk this earth

from which we came,

every pebble known

and unknown,

we walk and return –

becoming dust,

making stone.

Kate Innes

September 15, 2015

The Year of the Gibbon: Apes and Monkeys – Part One

The Thinker Monkey from the Breviary of Mary of Savoy, c. 1430

Lombardy, Chambery Bibliotheque Municipal, MS 4 fol. 319r

Notice his belt, to which a chain would have been attached.

I had an encounter in South Africa which made a deep impression on me.

It was with a gibbon.

And it was in a zoo.

One is not meant to go to Africa to meet southern asiatic apes in captivity. But that is what happened and it has made me think carefully about the parts of human society that we project on to apes and monkeys, and the schizophrenic attitude we have towards them.

The children wanted to go to ‘Monkey Town’ link , and, to be honest, I did too. Because I enjoy seeing the beauty and variety of animals across the world, I do put aside my concerns and scruples about caged animals and occasionally visit zoos. It is something that causes me pleasure and embarrassment in almost equal measure. And if it is a place I have not visited before, I approach with trepidation.

In this case my fears were, for the most part, unfounded. The enclosures were large and well designed, and it was the walkway for the humans that was caged, allowing the monkeys plenty of space to display their incredible acrobatic abilities. However, what made the visit extraordinary was the desire of many monkeys to interact with the human visitors. One spider monkey played push-me pull-you with my son and a twig. The marmosets raced us to and fro.

But when we came to the gibbon, things were quite different. There were several gibbons in a large enclosure, and when I came to the fence a few moments behind the rest of my family, an older female gibbon was already holding my daughter’s hand.

She held each of our hands in turn. This went on for some time. Then she turned around and hung, with her back to us, against the wire fence. She wanted her back scratched. All this time she did not make a sound; just gazed at us, calm and self possessed, with her intense melancholy eyes. We stayed with her until the zoo closed.

The gibbon is one of the ‘lesser’ apes, due to its smaller size than gorilla, chimp and orang-utan. It is tailless, but still is the fastest and most agile tree-dwelling mammal, due to the extraordinary length of its arms and the clever ball and socket joint in its wrist. Gibbons have been observed to mate for life.

Monkey Town is home to many apes and monkeys who have been rescued from neglect or inappropriate environments. There was one who was a recovering alcoholic, as his previous owner had given him beer to drink every day. Although I do not know this female gibbon’s history, it seems likely that she was used to human contact and company, and although there were plenty of other gibbons to interact with and she had obviously born several babies, she sought out human interaction.

In the Medieval period in Europe, apes and monkeys were popular pets for the rich. They became an exotic status symbol, and it is quite common to see examples of fettered monkeys in the margins of medieval manuscripts. But the ape and the monkey were also symbolic of degradation, sin and the devil in the Medieval world view. They were ‘man unbounded by constraint’, and as such, a symbol of those who give into their animal cravings, most commonly lust and greed. And they were a very useful satirical tool for the artist. See Apes in Medieval Art

Monkeys drinking – from Roman d’Alexandre – Tournai early 14th century

By contrast, in China where the gibbon is a native, they featured prominently in ancient Taoist poetry, were known as the ‘gentlemen of the forests’ and considered noble. Gibbons were believed to be able to live for hundreds of years and to transform themselves into humans. Their incredibly powerful voices, calling across the Yangtze gorges, came to represent the sadness and melancholy of travellers far from their homes. But this respectful view did not stop people from destroying the thing they admired in an attempt to own its beautiful qualities.

“The popularity of captive gibbons being kept as pets appears to go as far back as written history . . . The traditional method to catch a live gibbon always consisted in looking for a female carrying an infant, then killing the mother with an arrow or a poisoned dart from a blow-pipe and taking the infant still clinging to her when she has fallen dead onto the ground. Humans often became deeply attached to their pet gibbons. When a king of the Chou dynasty (i.e. Chuang-wang, 613-591 B.C.) had lost his gibbon, he had an entire forest laid waste in order to find him.”

See this informative blog from Thomas Geissmann : gibbons in chinese art and poetry

Two Gibbons in an Oak Tree by Yi Yuanji

Song dynasty

Neither of these extreme views are particularly helpful for the apes and monkeys who have to negotiate the human wasteland or human jungle. Both are merely a shadow, a reflection of us – that we project onto these intelligent animals. We are fascinated by the degree to which they are like us, and not like us – as we are with our own children. Turning wild primates into pets seems to be part of a desire to make them even more like us.

Will that help them in this human dominated age? Will it harm them?

Having met a gibbon, who was obviously affected by past human contact, I see the contradictions in my own feelings. It was an extraordinarily moving experience to be trusted by a gibbon. It made me hungry for more interaction. But that gibbon had been forced into our humanised environment. Forced to live in a house and a zoo, and if nothing is done, that may be the only environment in which gibbons do survive.

The IUCN Species Survival Commission has declared that 2015 is the Year of the Gibbon. Almost all of the gibbon species are endangered due to habitat loss (99% of habitat in China already gone), hunting and illegal trade. Mother gibbons are hunted and killed, just as they were thousands of years ago, in order to acquire the babies for the pet market. Often, both mother and baby die.

In Britain, one is allowed to own primates as pets. One can buy a baby monkey on the internet, with little or no regulation. In 2014, the government decided not to ban the owning of monkeys as pets, claiming this law would be ‘draconian’. They decided that no legislation should be approved until more was known about the situation. Here is part of the response from conservation organisations.

Philip Mansbridge from Care for the Wild said: “The report says that there are a lot of unknowns: we don’t know how many primates are kept as pets, we don’t know how well they are kept, we don’t know if existing legislation is working. But deep down, we do know one thing: that monkeys, chimpanzees and other primates ultimately are not objects for us to own. And that information alone should be enough to settle this debate once and for all.”

The Guardian 10 6 14

Let us work towards a world where primates do not need to be rescued,

because they are swinging through their forests,

calling across the deep ravines

to those of their own kind –

grooming and holding each other –

clinging to their own mothers

and living out their own lives.

Kate Innes

September 3, 2015

The Mighty Elephant

Elephant drinking from the Zambezi River

I have recently returned from a return visit to Zimbabwe and Southern Africa. It was a journey that will provide grist for my mind’s mill for years to come. But, at this very early stage of processing, I find it is the elephant and its behaviour which must be explored first.

It is interesting that, until the medieval period, elephant were endemic to the whole of the African continent. The extinction in Northern Africa (around a thousand years ago) occurred as a direct result of the ivory trade, to provide ecclesiastics and aristocrats with beautiful, prestigious artworks. Ivory has been sought after and worked for millennia. It is very hard, lasts indefinitely, doesn’t splinter and can be carved into the most intricate of forms. Medieval craftsmen felt its pale purity was particularly suited to representing the Virgin Mary.

Virgin and Child, carved in elephant ivory

1320-30 in Paris, Victoria and Albert Museum

(note the contrapposto of the virgin, which is demanded by the curve of the elephant tusk)

In medieval symbolism, elephants were almost as common as dragons, and similarly credible. They belonged to the semi-mythic world of the Bestiaries; books of quasi-religious natural history. The Bestiaries were didactic and precise about both the elephant’s habits and their meaning for the enquiring Christian mind. Even then the elephant’s concern for its family, the younger members in particular, was noted, as well as their prodigious intellect and memory. They were said to be symbolic of Christ himself. Their main enemy was the dragon, which, when they were in water to give birth, would bite them and attempt to drag them down to the depths. The dragon is always symbolic of the devil, and the elephant fought with it as Christ did with Satan.

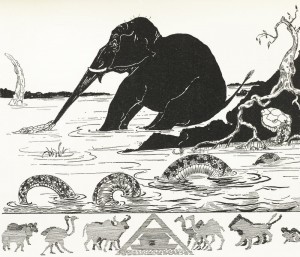

The eternal battle between the Dragon and the Elephant

from the Worksop Bestiary, MS M. 81

12th century, Pierpont Morgan Library

Although it is a digression, I cannot help but draw a parallel with the story of The Elephant’s Child by Rudyard Kipling. In this cautionary myth, the usual outcomes are turned on their head as, instead of being killed by his ‘insatiable curtiosity’, the hero of the tale actually gains the elephant’s most useful and distinctive feature: his trunk. The crocodile (a dragon by any standard), pulled his little nose into ‘a really truly trunk, such as all elephant’s have today’ during its attempt to drag the young elephant into ‘the great grey-green greasy Limpopo river’, to eat him. With his advantageous trunk, the Elephant’s child was then able to mete out revenge on his ‘dear family’ who had subjected him to repressive spanking all his life for being too curious. A story to gladden the hearts of liberal educators everywhere.

An illustration from The Elephant’s Child, Rudyard Kipling

(note also the bi-coloured python rock snake which we had the privilege to hold during our trip)

We saw many elephants during our five week trip. In one day in Hwange National Park, we saw over two hundred. It was awe inspiring, it was mesmerising. We were able to see for ourselves the way family groups protect their young, the exuberance of the young bulls, the clumsy drinking and bathing of the elephant children, the command of the matriarchs.

But, from the comfort of my desk in Britain, I am now trying to make sense of what is happening to the elephant in Southern Africa, and what this means for its future. We saw far more elephant on this trip than we did in the two years we worked in Zimbabwe between 1992-94. The concentration of the herds in the National Parks has surged dramatically. We also saw elephant on the road side in Victoria Falls and on the shore of Lake Kariba. Elephants are increasingly able to live only in tourist areas, as the African population relying on subsistence agriculture can ill afford to have their crops flattened. And the threat of poachers is ever present. The demand for ivory from the far east, Singapore, Japan and China in particular, is stronger than ever, and the potential gain in hard currency as well as bush meat, is difficult to resist.

At Chitsungo Mission in the Zambezi Valley, we met Colin, a friendly and focussed young man, who was very open about his past. He spent four years in prison for killing seven elephants and trading the ivory. In prison he was taught how to crochet and converted to Christianity. Now he is trying to make a living from his craft, and is desperate for help to fund his production and market his goods. He wants nothing more to do with poachers, or prisons.

Colin and models with his crochet goods: caps, rucksack, and tablet case

Meanwhile the rising middle class in China can now afford high-status ivory products, and the demand is growing. The curbs on the ivory trade, negotiated through CITES, (the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Flora and Fauna) have largely been ignored. Robert Mugabe, Zimbabwe’s ever-present President, has even been accused of bartering tonnes of ivory for weapons with China, breaking his country’s commitment to CITES.

The issues around elephant conservation and the ivory trade are very complex, and I cannot pretend to understand them all. Nor do I feel able to lecture those in Africa who kill elephants in order to protect their livelihood, or to make a living. What would I be willing to do if my children were desperately hungry? As one of my former pupils explained when I met him in Harare: “For us elephants are normal, and more of a pest than an attraction.”

But I find it horrifying to contemplate their slaughter.

Because they are killed so brutally. No quick well-managed death for them, as we want for our sheep and cattle here in the west.

Because there are such strong bonds between them. From all behavioural evidence, they love and they grieve.

Because they are extraordinary, perfectly adapted animals, who despite their size can be remarkably gentle, and who can walk with deliberation through the narrow paths of the bush and disappear like smoke.

“It is a fact that Elephants smash whatever they wind their noses round,

like the fall of some prodigious ruin, and whatever they squash with their feet they blot out.

They never quarrel about their wives, for adultery is unknown to them.

There is a mild gentleness about them, for if they happen to come across a forwandered man in the deserts, they offer to lead him back into familiar paths. If they are gathered together into crowded herds, they make way for themselves with tender and placid trunks, lest any of their tusks should happen to kill some animal on the road.

If by chance they do become involved in battles, they take no little care of the casualties, for they collect the wounded and exhausted into the middle of the herd.”

(From The Book of Beasts, a translation of a 12th century Latin Bestiary, Cambridge University Library 11.4.26 by T.H. White, 1954)

It seems that elephants could teach us much about ‘humanity’.

An elephant family in Hwange National Park, 2015

July 20, 2015

Candle flame, lamp light

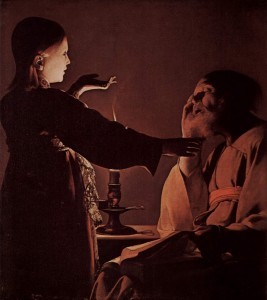

Detail of Christ in the Carpenter’s Shop –

Georges de La Tour-1645 -The Louvre, Paris

Looking at Georges de La Tour’s work reminds me that, for the vast majority of the history of human civilisation, nightfall has been followed by the lighting of lamps and candles, and by the contemplation of fire. De La Tour was a master of chiaroscuro, the dramatic play of deep shadow and bright light, the flame either bare or hidden behind a hand. But he doesn’t allow the light merely to set the stage. In his paintings, the flame is a central character and the focus of our gaze. Many of his paintings are ostensibly religious in subject matter. Some include children carrying lamps and candles, their skin an unblemished mirror for the warm light. I think de La Tour enjoyed this partnership of flame and youth, and the tenderness of forms softened by wavering, living energy.

The dream of St Joseph, c. 1628-1645

Musee de Beaux-Arts de Nantes

In a few days I will return to Africa, accompanied by my three children and the man I met there. All sorts of things swirl around in my mind when I think about the two years I spent working as a teacher in rural Zimbabwe. Far too many to express here. And since the day that my husband and I decided to return for a long holiday, to show our children the place we fell in love with (and the place we fell in love), I have been beset with longing and anxiety in almost equal measure.

One cannot step twice in the same river, as we have all been told. I know that it will have changed. Zimbabwe has been through some bad times since I left in 1994. Equally, the advent of the mobile phone has transformed so much of interaction throughout Africa, giving more power to the producers traders and growers, and of course, there has been a massive increase of globalisation through the internet.

However, the great Zambezi River will still be there, and we will see it flow and thunder. We will, I hope, hear women singing and clapping in church, accompanied by the syncopated drumming that makes everyone dance. And we do very much want to see elephant, giraffe and the beautiful Lilac Breasted Roller once again.

But one of the things I am most looking forward to is the fire light and candle light. Night falls quickly in Southern Africa, usually at about 6pm. Then the sounds change, the stars are revealed and the matches are struck. At the mission where I lived in the Zambezi Valley, the generator would go off at 9pm and, from then on, we did everything by candlelight. Of course most Africans do not live with a generator, and so candles and lamps are the norm.

The only times we experience this in Britain is during a power cut, or when we take ourselves off and camp in the wilds. Then we are forced back to the contemplation of the most charismatic of elements. Our children like it best when the fire is lit and, to quote my youngest, “I can poke it with a stick.”

Children and flame – both are fascinating, quick and volatile. I am looking forward to many nights in their company as we camp our way from South Africa to Zimbabwe, under the distant fires of the stars.

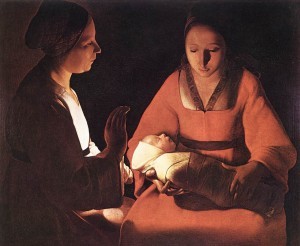

The New Born Christ, c. 1645-1648

Musee de Beaux-Arts de Rennes

To finish, here is an old poem, written when the children were very small, during a power cut.

Three candles

They are enough to see by when the lights go out,

peopling the darkness and filling in the deep,

startling silence. Tonight, in this house,

there are three candles and three children, asleep,

hot, restless, muttering and then, leaving

their gale of dreams, they lie still, just breathing.

The light and warmth holds me when I too should sleep,

Joined, for once, in the earth’s diurnal pace.

These slender lights, like children, hold the heart,

and kindle radiance in reflection and face.

The world is turning from and to the light.

While I sit with these candles, I do not fear the night.

Kate Innes

July 2, 2015

Windows: looking in, looking out

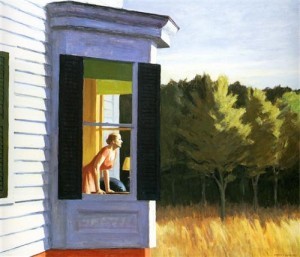

Cape Cod Morning – 1950 by Edward Hopper

Edward Hopper (1882-1967) was raised in New York State, not very far from where I grew up, although, I hasten to add, much before my time. An introvert, almost a recluse, he chose to paint houses, women and urban scenes typical of the east coast of America: stark white clapboard, contrasting shutters, glaring sun; and at night: fluorescence, neon and shadow. He spent his latter summers in Cape Cod. Most of his female figures were modelled on his wife.

There is something urgent and sad about his work. His paintings are full of isolation and silence. Very often windows are a key feature of the composition and the viewer observes figures through them (as in Nighthawks, for example). The windows seem to emphasise the sense of separation and self-containment in his work.

I can’t say I enjoy it, but it moves me, perhaps particularly because I am reminded of my childhood amongst the trees and lakes of Connecticut, the blazing sun of the seashores, the unremittingly direct and obvious human constructions. Black and white, sun and shadow, nature and man. The only subtlety is in the nuanced emotion evident in the gesture, posture and expression of the figures.

When Andrew Motion presented this painting, Cape Cod Morning, in a workshop at the Wenlock Poetry Festival and suggested we use it as a starting point for a poem, I had mixed feelings.

I knew it would not be an easy poem.

It immediately conjured up feelings of separation; a relationship broken or unequal. The intensity of the gaze looking out of the window seemed to contain both resentment and longing. I wrote several drafts along these lines. So it was with some amusement that I came across this quote about the artist’s own thoughts:

The tendency to read thematic or narrative content into Hopper’s paintings, that Hopper had not intended, extended even to his wife. When Jo Hopper commented on the figure in Cape Cod Morning “It’s a woman looking out to see if the weather’s good enough to hang out her wash,” Hopper retorted, “Did I say that? You’re making it Norman Rockwell. From my point of view she’s just looking out the window.”

quote source

I cannot understand that. There is nothing in the figure of the woman that speaks of ‘just looking’. And certainly she is not thinking of her washing. Whatever she is searching for from her vantage point in front of the large glass is something that has cut her heart, caused her to wake in tears in the middle of the night. Perhaps time and time again.

So the artist creates, and the creation goes forth to be appropriated and changed, made different in everyone’s eyes. The painting (poem, sculpture, book etc.) itself becomes a window. Perhaps the creator offers her view on the world from this window, and the viewer/reader sees it. But more often the viewer gazes at the window, expecting to see what the artist saw, and instead sees the reflection of herself.

My own poem changed too, until it was no longer really about the painting.

Here is what might be the final version:

I am like a woman

I am like a woman

standing at a window

scanning the sea

gripping the fabric of my sleeves

searching for the sheen

of sun on skin and hair.

The taste of salt is on my lips.

I try not to beckon you back.

You are like a woman

who goes to a beach

in the early morning

and sloughs off her skin

her legs and feet.

You glide into the water

and dive

deep and unhurried.

When your head breaks

sometimes you turn your

head to the blank window

on the headland.

Sometimes you wave.

Kate Innes

June 22, 2015

The Cat before the Altar

A tabby cat enjoys watching a patch of sunlight in the peaceful, cordoned-off area in front of the main altar of Wells Cathedral

During a fascinating research trip to Hailes Abbey and Wells Cathedral, I was struck by the number and variety of animals I found in these well-preserved sacred contexts. Our age, on the whole, seems to disapprove of animals in church, as if somehow their animal nature made them inappropriate in the humanly constructed holy space.

This was not the case in Medieval art. Animals appear in abundance, taking on roles as faithful companion, indicator of nobility and symbol of just about every virtue and sin. They are painted on the walls, sculpted in the ceiling bosses and climb around the column capitals. They wind around the font and patter along the floor tiles. They look down from the highest heights, and mischievously up from below as part of misericords, little seats which supported the bottoms of monks and priests in church.

A boss from the ceiling of Hailes Abbey Chapter House, showing either Jesus fighting the Devil in the form of a lion, or Samson and the Lion

In this way, the churches constructed and decorated by medieval people mirrored the natural world outside, rather than making a ‘better’ separate space for worship. The church was a place for people to learn what the natural world meant in the heavenly plan, and every last animal had its role to play and its lessons to teach.

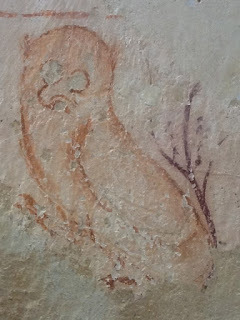

A short-eared owl from Hailes Parish Church (13th century), an adorable animal supposed to represent sin and darkness

The Medieval Bestiaries (about which I have written more here: robin redbreast post) were very eager to tie up the behaviour of animals, whether real or imaginary, with their spiritual significance. This is not an area of theology pursued in modern times, but perhaps the celebration of and identification with the natural world should be more encouraged. The many animals in danger of extinction could certainly stand as symbols of human indifference and greed in a modern iconography.

A hybrid elephant from Hailes Church

During the Reformation a rift occurred between image and word, between the natural world with all its instructive behaviour and the spirituality of the intellect. Natural representations were covered or destroyed by those who wished to emphasise the primacy of the revelation of God through the word, the Bible, rather than through creation. This is obviously a vast oversimplification of the profound and violent change that the western church underwent at that time, but it is one of the obvious effects for people exploring the development of sacred buildings.

To me this creature looks like a Dachshund with wings and chicken legs, Hailes Church

In my opinion, it is only when nature and humankind, image and word, intellectual and physical are joined together that we come anywhere near being able to express the Divine.

The tabby settles down for a nap in front of the altar of Wells Cathedral

A fragment from Jubilate Agno by Christopher Smart (1722-1771)

For I will consider my Cat Jeoffry.

For he is the servant of the Living God, duly and daily serving him.

For at the first glance of the glory of God in the East he worships in his way.

For is this done by wreathing his body seven times round with elegant quickness.

For then he leaps up to catch the musk, which is the blessing of God upon his prayer.

For he rolls upon prank to work it in.

For having done duty and received blessing he begins to consider himself.

For this he performs in ten degrees.

For first he looks upon his forepaws to see if they are clean.

For secondly he kicks up behind to clear away there.

For thirdly he works it upon stretch with the forepaws extended.

For fourthly he sharpens his paws by wood.

For fifthly he washes himself.

For sixthly he rolls upon wash.

For seventhly he fleas himself, that he may not be interrupted upon the beat.

For eighthly he rubs himself against a post.

For ninthly he looks up for his instructions.

For tenthly he goes in quest of food.

For having considered God and himself he will consider his neighbour.