Kate Innes's Blog, page 3

January 28, 2018

Rural Women – Past, Present and Future

Rural women – not a topic you see up for debate or discussion very often. But I believe rural women deserve more attention, and that they have been both under-estimated and under-represented. Their role has changed over time. Due to the rise of the cities, there are new challenges. But women living in the countryside, producing, raising, and nurturing, are as important as ever.

This event sets out to bring these issues into the open, and I’m delighted to have been asked to be part of a panel of experts who will be exploring the experience and importance of rural women in the past, present and future. Tickets £10 (£7 concessions) from Shrewsbury Museum & Art Gallery 01743 258885

Pentabus Theatre Company presents

An Evening on Rural Women

at the Shrewsbury Museum & Art Gallery

Rural Women past, present and future.

Friday 16 February | 7.30pm | Shrewsbury Museum & Art Gallery

Pentabus Theatre Company is delighted to present An Evening on Rural Women chaired by local and national radio presenter Vicki Archer, and a panel of 5 brilliant women including Countryfile Farming Hero 2015 and veteran farmer Joan Bomford, at Shrewsbury Museum & Art Gallery on 16 February, 7,30pm.

‘I think the First World War did change women. Because once we’d had a taste we wouldn’t go back to service, we were free.’

Agnes Greatorex, The Women’s Land Army, 1919

What are the misconceptions around the roles that women have played in rural life? What does it mean to be rural women in the 21st century? Featuring a panel of feminists, journalists, experts and writers on Rural Women, and discussing the inspiration behind, Here I Belong by Matt Hartley which due to demand will be retouring nationally this spring 2018.

‘Your mother was born here. In her house there’s a path she’s worn between here and the village.’

Here I Belong by Matt Hartley

The panel also includes author and poet Kate Innes (trained in archaeology and museology, her books include ‘The Errant Hours’ set in Medieval Shropshire, and ‘Flocks of Words’ a collection of poetry about the rural mythic landscape), Polly Gibb (Director of WiRE – Women in Rural Enterprise, awarded OBE for services to rural enterprise, and one HRH Prince Charles’ 10 Heroes of the Countryside), Pentabus Theatre Company’s Artistic Director Sophie Motley (on behalf of playwright Matt Hartley, Here I Belong) and Celia Rawlings (Chairman of Shropshire Federation of Women’s Institutes). Each of the speakers will present for up to 10 minutes, followed by a group discussion and an opportunity for questions from the audience – we’d love to hear from as many of you as possible, including men!

Artistic Director Sophie Motley said: ‘To celebrate Elsie, the inimitable 90 year old character of Matt Hartley’s play Here I Belong, I’m thrilled that Pentabus are hosting this fantastic evening of rural feminism. From farmers to activists, from artists to journalists, this evening will really spark debate and challenge perceptions of women in rural areas and rural communities.’

Pentabus are the nation’s rural theatre company. We tour new plays to village halls, fields and theatres. We seek out communities of least engagement, telling stories with local relevance and national impact. We believe people in rural areas have as much right to top quality theatre as their urban counterparts. Pentabus’ work tours to village halls and studio theatres as well as non-conventional arts spaces, bringing new writing that explores issues pertinent to rural communities to audiences across the country.

Friday 16 February | 7.30pm | Shrewsbury Museum & Art Gallery

Running Time 90 minutes (approx.) | Recommended for ages 12+

pentabus.co.uk | Twitter: @pentabustheatre #ruralwomen #HIB | Facebook: PentabusTheatre | YouTube: PentabusTheatre | Instagram: Pentabustheatrecompany

[image error]

January 25, 2018

Travelling in Time and Place

I am spending a lot of time in the late 13th century at the moment, editing All the Winding World, the sequel to The Errant Hours. The story involves quite a lot of travel – local, regional and international. And this has brought me up against an anomaly in our thinking about the Middle Ages.

Because we know that the people in Medieval Europe did not have planes, trains and automobiles, we are a bit guilty of assuming that they didn’t get out much. It is hard for us to imagine how people did business or pleasure on a more than local scale without the benefit of the internal combustion engine. But Medieval people, and indeed all people in ‘the west’ up to the industrial revolution, genuinely did, as this fascinating book, The Medieval Traveller, has helped me find out.

In our age, we dismiss the idea of walking long distances (or even quite short distances) because it might take too long, be too tiring, mean we have to carry a lot of stuff that might be heavy etc. I am as guilty of this as anyone.

And of course it is rare to keep a horse, donkey, ox or mule. They are often difficult to park at the supermarket. Owning a boat or barge is equally rare. In fact owning horses and boats or ships is now seen almost exclusively as an elite and expensive hobby in the west.

But in the Middle Ages travel, although often difficult and sometimes dangerous, was still common, and undertaken by every class of person. People went places to buy, to sell, to socialize, to find work, for special occasions, for religious purposes, for military purposes, for political purposes, and sometimes just because they wanted a change of scene. Horses helped, as did pack animals of many kinds. Water travel was often quicker than overland. And as now, the more money you had, the more comfortable you could be whilst travelling. But equally, the more tempting you were to robbers and outlaws.

It would take much too long to detail the various routes, means and purposes of Medieval Travel. But if you are interested, The Medieval Traveller is a good companion on the journey to finding out.

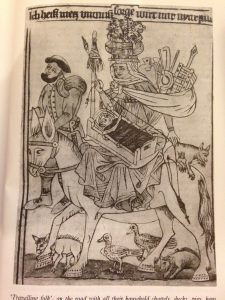

There is an illustration right at the end of this book that particularly struck me, for several reasons. It’s a woodcut from the 15th century, a bit later than the period I usually research, but it really struck a chord.

Travelling folk on the road with all their household chattels. 15th century German Woodcut.

Here is the late medieval woman on her horse (or possibly mule), with her husband (probably) alongside her. She has a basket of chickens on her head, various household items, including a bellows, on her back. In her lap is a baby in a cradle, and she is spinning flax from her distaff onto her spindle as she goes. Her cat, ducks and pigs are all along for the ride (or walk). Where is this family going? We don’t know. But we can see that the woman is multitasking like mad, as most women do, before, during and after a journey.

Perhaps the picture is a bit exaggerated, but there is a significant truth behind it.

It reminded me of something I saw about twenty-five years ago, when I was working at a rural secondary school in the Zambezi Valley in Zimbabwe. I was walking back to our house near the Catholic Mission with some other teachers, and coming towards us was a group of about four young African women. They all had loads on their heads. Heavy loads, which was nothing unusual. But one of them was really astonishing. She was about eight months pregnant. She had a pile of wood on her head. Not sticks or logs, but long, thick, big and heavy tree branches, tied into a large bundle. And as she walked along, she was knitting. She might have had a baby on her back as well, but I’m not sure about that. Certainly the other women in the group did.

I have never lost my feeling of wonder at what she evidently took as a normal walk to get some wood. This was also the expectation for people in Medieval Europe. Merely feeding, warming and clothing a family was hard physical work. They would not see walking twenty miles a day carrying a pack as any particular hardship, as long as there was food and drink at the other end. And the inns, taverns, monasteries and hospitals that lined the major routes made sure there was – for a price, either worldly or spiritual. Perhaps for many, travel made a pleasant change from the drudgery of everyday chores.

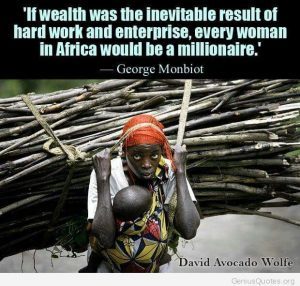

As I was musing on all this, I remembered a quote that I have seen on Facebook in the past by George Monbiot:

But we all know that wealth is linked with the control of resources, and not with sweat and hard graft.

It was true in Medieval times, and it’s true today.

I will explore this more in my next blog, which will focus on Rural Women, in response to an event with Pentabus Theatre that I’m lucky enough to be part of in February.

January 5, 2018

2017 – The hours gone but not forgotten

The Labours of the Months, January, The Golf Book, workshop of Simon Bening, Bruges, 1520-30.

I felt rather muddle-headed over the Christmas holidays. I expect I’m not alone! After all, t’is the season to be busy – at least that is how it is in the 21st century. But I thought that the last day of 2017 was a good time to look back over the year and be grateful for all the lovely things that have happened.

As many of you will know, I’ve been working on the sequel to ‘The Errant Hours’ for some time now. The good news is that it’s close to being finished, and I expect to be publishing it in June 2018. Soon I will be able to reveal the front cover, which is always a highlight for me. I love the designs that MA Creative have done for my two existing books, and the new one is both beautiful and intriguing.

It’s been an unexpectedly exciting year for me in the poetry realm. I was given the chance to work with the acoustic group, Whalebone, and this has transformed the way I think about my poems. It has been a powerful experience and a joy to work with such talented and professional musicians. Out of this collaboration emerged Flocks of Words – the performance, and ‘Flocks of Words’ – the collection! New gigs will be announced soon.

In the meantime, ‘The Errant Hours’ has continued its travels. Rather bizarrely, at the Wenlock Christmas Fair I was told by a customer that it is now on the reading list for Harvard University’s Celtic Studies course. I am awaiting confirmation of this, but if it is true, expect loud celebrations!

Sales are well over 2,000 now, which, according to Writing West Midlands, is higher sales than for many Booker nominated novels. I must thank the extraordinarily committed Shropshire Indie Book Shops and outlets in Shropshire, particularly Wenlock Books, Pengwern Books, Castle Books, Burway Books, BookShrop, Eaton Manor, The Raven Hotel and Shrewsbury Museum & Art Gallery for selling close to 600 copies, and for their enthusiasm and support for this locally grown story.

And many thanks to all of you, who have been advocates for my independently produced books. I am very lucky to have so many good friends and readers who have spread the word that a book which is not published by a multinational publisher can still be a great read.

I recently received this lovely review (below) on Amazon. It means such a lot to get this kind of feedback, and to know that a reader has thought deeply about the themes in the book. But it is also wonderful to hear from people who read it all in one sitting because they couldn’t put it down, who enjoyed the rush of the chase. I need both of these experiences – adventure and contemplation. And I hope to share more of both with you in 2018.

‘Being a historian I usually avoid reading historical fiction, but I loved this moving story which makes excellent use of authentic period and local detail. I’d recommend getting the beautifully produced high quality paperback rather than the Kindle, it would be a shame to read this in digital format as it wonderfully conveys and celebrates the power of books as artefacts in a largely illiterate society. I very much look forward to reading more from Kate Innes.’

July 12, 2017

Marrying a Murderer – The Errant Hours 2

The University of Surrey Blog supported by the Leverhulme Trust –Women’s Literary Culture and the Medieval Canon has kindly asked me to contribute another guest post.

I took the opportunity to explore the literature which informed the second part of ‘The Errant Hours’ – an intriguing mix of Courtly Romance, Warrior-culture and Celtic Religion, which in the end, is both comic and tragic.

Sounds complex? Let me try to explain . . .

The Errant Hours 2: Marrying a Murderer

In my last blog in May, I wrote about literature celebrating Virgin Martyrs in the first part of my medieval novel, The Errant Hours. In this post, I will focus on the Arthurian legend – The Knight with the Lion/The Lady of the Well, which informed the second part.

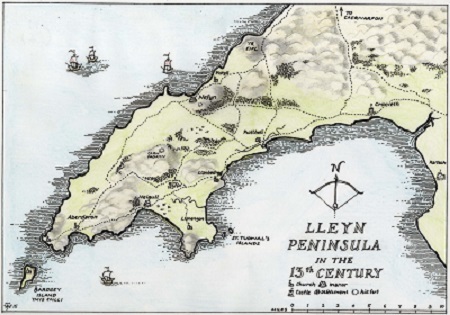

The location of the novel moves from Shropshire to the Lleyn Peninsula in North Wales in this section, because King Edward I organised a Round Table at Nefyn in 1284. This Tournament took place after the conquest of Wales in the second Welsh War (1282-3). Edward I was an Arthurian enthusiast. He recognised the power of the myth and its flexibility. By holding an Arthurian Tournament, he knew he could cast himself as the ‘New Arthur’ uniting the kingdom under his rule. And by inviting lots of nobles from Ireland and the Continent, he could indulge in some status display and conspicuous consumption.

Map from ‘The Errant Hours’ Part Two – drawn by James Wade

Edward used this myth again and again, to signal his right to rule Wales and Scotland and to be served faithfully. There are very few specific descriptions of what happened at the Round Table in Wales, but, based on accounts of other such events, there was probably a mêlée, a jousting competition, dancing, games and re-enactments of Arthurian stories. And what stories they would have been! Confusing/fascinating/gruesome conglomerations of Warrior culture, Romance and Religion.

Gawain fighting four knights BL Add MS 10293 f. 81v 14th century – Public Domain Image

My interest in this body of literature is in the role women play, the expectations placed upon them and the way they react. It is very well reported that medieval women were treated as chattels, that they had no rights to hold property of their own whilst married. Misogyny was promoted in churches, stories and art. Women were portrayed as temptresses – out to snare and entrap, conceal and emasculate. But Courtly Love was also a powerful influence, encapsulated in the Romance of the Rose. Many women did run businesses, control large estates and affect political outcomes. The cult of the Virgin Mary was at its height. Medieval women were presented as both holy and fallen, powerful and weak, to be cherished and to be condemned.

Chrétien de Troyes’ Arthurian Romances were the most popular of the Arthurian myths at the end of the 13th century, so I knew the play at the Tournament should come from this collection. The re-enactment had to have something to offer the King – a regal piece of stagecraft to massage his ego and proclaim his authority. But I also wanted a story that would reflect on the situation and role of the heroine of the novel.

As I explained in my first post, Illesa is a young woman on a dangerous journey, during which she comes of age. The play provides the background to the loss of her naïveté, and the start of her resolve to maintain control over at least a portion of her life, through subterfuge and cunning.

In the end, I chose Chrétien’s ‘The Knight with the Lion’ – a tale almost identical in plot to the story of ‘The Lady of the Well’ from The Mabinogion.

Yvain meets a maiden in a forest BL Add MS 10293 f. 248v – Public Domain image

In summary, the Knight Yvain (Owain in the Welsh version) goes forth, seeking a worthy opponent. He is directed to a fountain (or well) in a distant land, and instructed to pour water from it onto a flat stone with a silver bowl. Once done, a thunderstorm presages the arrival of a Black Knight on a Black Horse, who issues a challenge to Yvain, the invader of his territory. Yvain fatally wounds the Black Knight, and pursues him back to his castle. The portcullis comes down on Yvain’s horse, killing it and trapping him between the two gates. So far – so knightly. But from this point, the story becomes more interesting. Enter Lunette.

Lunette has met Yvain before, he treated her well when she visited King Arthur’s court. She, at this point in the tale, is a morally ambiguous go-between character. She is not powerful in status – but in wit, not a romantic interest – but a friend. Her intervention with a magic invisibility ring saves Yvain’s life. But when she brings Yvain into the castle, there are some unintended consequences. Yvain sees the wife of the Black Knight mourning over the body of her husband, and is immediately filled with passionate ‘love’ for her. The Lady Laudine rends her clothes, her hair and her flesh in grief for her husband. But this does not put Yvain off. He is determined to have her, and Lunette, Laudine’s handmaiden, agrees to help him accomplish this.

Lunette uses the argument that Laudine should accept the hand of the knight who can defend her people and her land, (it is her land, now that she is a widow). She needs someone to keep the territory by force of arms, and Yvain, the man who bested her husband, is the obvious choice. The story goes on to show Laudine’s change of heart, her marriage to Yvain, and the arrival of King Arthur and his knights to join in the feasting. For Yvain has won the land not just for himself, but also for his tribe – Arthur and his court.

At this point, the story is only just beginning. It goes on to be a typical tale of boy gets girl, boy loses girl, boy gets girl again, but with many duels to the death, supernatural serpents and, of course, a lion.

What interested me was the characterisation of Laudine, and to a lesser degree Lunette. I asked myself: What circumstances would induce a woman to marry the man who murdered her husband? In order to answer this, I began researching the origins of the tale, which is based on people in 6th century Britain, a time when Christianity was only just beginning to reclaim some power after the Roman retreat. British tribes clung on against the Angles and Saxons from centres in Wales and Scotland. Descriptions of bloody battles are the main form of literature from the time.

Yvain/Owain is one of the very few Arthurian characters with an actual historical presence. He is Owain mab Urien, a warrior of Rheged in the mid 6th century, written of by Taliesin. And he has some crimes under his belt. He is said to have disguised himself as a woman in order to enter the chamber of his cousin Thenew (Teneu/Denw), whom he raped. When Thenew’s father Lleuddun (Lot of Lothian) discovered she was pregnant, he had her thrown off Trapian Law, the Gododdin tribe’s hill-fort. She miraculously survived, but that was not good enough for her father, who had her set adrift on the sea in a coracle. When she arrived at Culross she was taken in by a local saint and gave birth to Kentigern, who later became St Mungo, patron saint of Glasgow. Teneu also became a saint, in Wales, and taught St Winifride.

Traprain Law from the North – Creative Commons License – Kim Traynor

Obviously much of this is accumulated legend upon story. But it points to the type of society in which an historical Laudine would be making decisions about whom to marry and how to protect herself and her people.

Celtic belief, in as much as we can understand it with so few written records, placed great importance on sacred springs and wells. They were considered gateways between the worlds, places where communication with spirits was easier. The majority of Celtic water deities were female, and associated with healing as well as regeneration. It was common for springs to be repurposed by the early Christians, who claimed them for local saints. Winifride’s Holywell is perhaps the most famous.

St Winefride’s Well – North Wales – Creative Commons License – chestertouristcom

In the tale of Yvain and Laudine, the emphasis on, and centrality of, the Lady and her Well and its role in protecting the land seemed to indicate a Pagan/Celtic holy well which was kept by a priestess.

Once I had understood this basis to the tale, the power structure of it shifted. Laudine may not have physical power, but there was supernatural power to draw from, and I was intrigued to explore how she might exploit it. For example offerings and messages were (and still are) thrown into springs for gods and spirits. In many springs, including Sulis Minerva in Bath, there have been numerous discoveries including lead curse tablets written backwards, detailing the punishment to be meted out the wrongdoer and folded over so that only the god could read them. When the Christian saints took over the springs, different offerings and different petitions were made, but they came from the same spiritual instinct.

So, in The Errant Hours, a re-enactment of story of Yvain and The Lady of the Well is performed for the King, narrated by Lunette, who is played by a cross-dressing actor who decides to sabotage the play in order to punish his lover.

But it is also told as it may have happened in the 6th century to a woman whose husband is killed and who must protect her family and her people by taking the murderer to her bed, whilst planning a chilling revenge.

These tales can carry innumerable retellings because they are so rich in symbolism, so elemental, so visceral in their conclusion that life is short, brutal and beautiful, and that men and women will struggle to survive through strategies both cultural and instinctive.

Kate Innes

Kate Innes was born in London and raised in America, returning to the UK in the 1980’s to study Archaeology. She taught in Zimbabwe before completing an MA and working as a Museum Education Officer around the West Midlands. She now lives in Shropshire. Her first novel, The Errant Hours, has been added to the reading list for Medieval Women’s Fiction at Bangor University. Kate has been writing and performing poetry for many years. Her collection, Flocks of Words, was published in March 2017. Kate runs writing workshops and undertakes commissions and residencies.

@kateinnes2

July 9, 2017

Dundee University Review of the Arts – ‘Flocks of Words’

The excellent DURA have posted a review of ‘Flocks of Words’. I am absolutely delighted by this beautifully written and thoughtful exploration of my poetry collection. I feel very well understood!

Many thanks to the reviewer, Susan Haigh, for her time and enthusiasm.

Flocks of Words is available from Amazon UK or through the ‘Get in Touch’ page

Read the original here DURA review site or you can read a copy of it below.

Kate Innes

(Mindforest Press, 2017); pbk £5.99

Flocks of Words, Kate Innes’s debut poetry collection, draws deeply on her love of the medieval, the mythical and the imaginative, which she overlays with a profound connection with nature and the Shropshire hills in particular. Her music is the music of distant stars and of creation, sometimes almost Miltonian in its wonder and terror. Her Earth is “a blue-blazoned orb hanging on the neck of night” (“Creation Myth”) and she writes,

Flocks of Words, Kate Innes’s debut poetry collection, draws deeply on her love of the medieval, the mythical and the imaginative, which she overlays with a profound connection with nature and the Shropshire hills in particular. Her music is the music of distant stars and of creation, sometimes almost Miltonian in its wonder and terror. Her Earth is “a blue-blazoned orb hanging on the neck of night” (“Creation Myth”) and she writes,

Before time was measured and marked,

in the great black between the stars,

beings lived, one of each kind.

Divided into five sequences, the collection moves back and forth through time, from pre-history to the present day, through vast land- and space-scapes, often with troubling scenes of biblical horror amidst images of the Creation.But the clear poetic stream running through all Innes’s poems (yes, she is obsessed with water) is a seemingly boundless imagination and immersion in the ancient world, often also closely bound up with images of both water and the universe.

The titular poem takes its imagery from the world of migrating birds to consider the living, organic, self-renewing nature of words; it imagines the freedom of not naming objects, “like the unseen stars at the edge of the universe”, “like Eden before Adam spoke.” She envisages word-birds returning, refreshed and new to enhance language. In “Walking the Hills” she turns to Darwinism to contemplate the evolutionary nature of earthly things;

We walk and return,

becoming dust

making stone.

Her imagery is often startling, panoramic, spine-tinglingly thrilling.

Elsewhere she focuses in on the minute, “the gyroscope of butterflies, / waterboatmen and the rifle sight/of the heron” (“Where it May Lead”) or on the discomfiture of a boy fishing and his inability to accept the distress of the caught fish. (“Fishing”).

Above all, Innes’s poetic focus is on the oneness of man with his environment, an impression of infinite continuity. She returns to a time when there were no noisy, polluting cars, “Before the drone of the road” . She paints a picture so vivid that the reader is tempted to linger, reading and re-reading:

In the time when the slice of oars and poles

slit the shining water down to twisted roots

and the river vein healed itself with the eddies,

with swimming sky.

(“Winter River”)

In “The Morning Path” Innes refers to the earth as a “familiar body” and, in “Late Light”, the sun belongs to the whole world, shining not only on her but on “all the Russian steppes”. Again, the collection invites the reader to look beyond the immediate environment, while also delves into the mysteries of the natural world. “Snowfall” focuses on the miracle of snowflakes, “… unseen/laws of our constrained belief, /fragile pieces of divine space.” Innes’s integral connection to the earth and to the universe is profoundly spiritual and overt: “I am part of the universe” (“Constellation”). Its magic and mysteries are as important to her as those matters offered by the real world.

If Innes’s work is widely informed by other artists, painters and wordsmiths – Christina Rossetti, van der Weyden, Velazquez, primitive cave painters in France and the stained-glass artist Margaret Agnes Rope – it is her broad and yet intense observation of nature which, for this reader, makes this collection very special. In “Spring”, lambs are described as “just bones/covered in a crochet of silky wool.” And in “Sleeping Dogs”, she allows the creatures to sleep – “Let them dream/, the wolf inside”. The gory nature of childbirth, too, comes into the great pattern of Innes’s poetic thought in a collection which will tempt the reader to return again and again to her observations in this lovely work. I look forward to her next collection.

Susan Haigh

May 15, 2017

The Errant Hours 1: Martyrs and Motherhood

Women’s Literary Culture and the Medieval Canon

An International Network Funded by the Leverhulme Trust

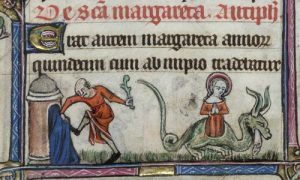

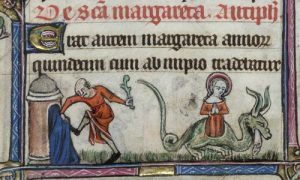

Image from The Taymouth Hours

BL Yates Thompson 13, f.68v

I am quite convinced that if you scratched most writers of medieval fiction, under the surface you would find a childhood spent reading stories about the middle ages: Robin Hood, Arthurian Myths, Fairy Tales. Perhaps you would also find a longstanding love of medieval imagery and symbolism, the pictographic shorthand for saints’ lives and biblical tales.

As a child, I devoured such stories, and I loved decoding medieval artworks. It was so satisfying to know that if the female saint was holding a tower, she was St Barbara, if a wheel or a sword then St Katherine and, if there was a gridiron, poor St Laurence. I felt like I’d learned a secret language. When I decided to study Archaeology at University, I expected it would have a bit more mystery and symbolism in it – a bit more romance and a bit less mud. Ah well. I had reckoned without the British weather.

My later career in museums allowed me to indulge those narrative interests, as each object has innumerable layers of meanings. But when I came to write my first novel, The Errant Hours, the influence of my early love of archaeology was still strong. Archaeology, in the main, looks at the discarded and unwanted remains of daily life, the broken things most people do not consider important.

In The Errant Hours, I wanted to uncover what life was like for the people who did not make it into the history books – to explore the daily lives of people who lived in the distant past, and to understand how their circumstances affected their fears, hopes and beliefs.

And certainly the large numbers of nails, bones and potshards I found on archaeological sites helped me do that, and to flesh out the characters’ habits and habitats. But it would not have been a very satisfying book without another ingredient.

People of the middle ages lived not just in a physical environment but in a spiritual and social one, and one of the most lasting and powerful elements of these medieval ways of thinking are the religious and secular stories that were commonly known and shared.

You may be familiar with the way Christian ideology at the time tended to characterize women as virgin/saint, mother/wife or whore/temptress. There are lots of influential medieval stories about saints and whores, and not nearly as many about wives and mothers. The first part of The Errant Hours explores the interesting relationship between a holy virgin and mothers in the legend of Saint Margaret of Antioch. The second half of the book explores the wife/whore relationship through the legend of The Lady of the Well/The Knight with the Lion, which I hope to blog about later in the year.

Most female saints were either martyrs or nuns, but the virgin martyrs seem to have been most popular. Looking at the passions of these saints in compilations such as Voragine’s ‘The Golden Legend’, I was struck by the similar outcome for young women who refused to have sex with powerful men: generally torture followed by death.

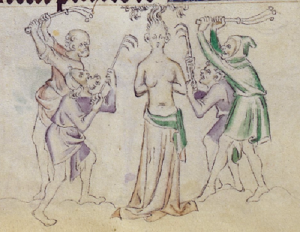

St Margaret of Antioch being tortured

BL Royal 2 B VII f. 308v (public domain image)

In some cases a miraculous return to life is achieved (eg. St Winefride) but then the woman goes on to become a nun, not to a ‘normal’ family life.

However in the case of St Margaret of Antioch, there is a nod to marriage and motherhood in her story, through a quite unexpected agency. And this interested me because, although some medieval women did become nuns, most women were not wealthy enough. The vast majority of ordinary women married and became mothers, or died trying.

St Margaret in prison and emerging from a dragon, who is still chewing on her dress. BL Yates Thompson ‘The Taymouth Hours’ MS13 f 086v early 14th century

According to the legend of her martyrdom, Margaret of Antioch (known as Marina in the Eastern Church) was a virgin convert to Christianity in the early 4th Century AD. Her father was said to be a priest of Jupiter, who disowned her after her conversion. She spent some time as a shepherdess, (a nod to her humility and sacrificial innocence) and then was abducted by the Roman Governor, Olymbrius, who wished to ‘marry’ her. When she refused, he had her tortured in numerous gruesome ways.

While all this was going on, she was also attacked by the devil in the form of a dragon (even Voragine reckoned this part of the legend was apocryphal, but that didn’t stop the dragon from becoming Margaret’s attribute). The dragon swallowed her, but when she made the sign of the cross its belly burst open and she came out ‘unharmed and without any pain.’ Voragine then describes how she was beheaded in front of the Governor – and before the final blow she made several appeals to God, including that those who prayed to her and read the story of her passion would be safe in childbirth and bring forth healthy infants.

And so, in accordance with medieval logic, because of these promises and because St Margaret had come out of the dragon’s belly unharmed, she became the patron saint of childbirth.

As I was researching medieval childbirth, I came across a manuscript that not only evidenced this belief, but also provided moving and tangible proof of the spiritual practice of medieval women. British Library MS Egerton 877 – The Passio of St Margaret, 14th century. Once I had read the translation of the text and the fascinating explanation, I knew straight away: this was the touchstone of my story.

https://www.bl.uk/catalogues/illuminatedmanuscripts/TourKnownB.asp

This special manuscript is an Italian copy of a book that would have been very common in England, but which did not survive the reformation: a description of the horrific torture of a virgin that was designed to be a birthing aid – to be read out to a woman in labour. The story is a standard version of the life of St Margaret – but the final pages are extraordinary.

They consist of a series of prayers that would have been read to the woman in labour, including this entreaty to the unborn child:

“Come forth. If you are male or female, living or dead, come forth for Christ summons you, in the name of the Father, and the Son, and the Holy Spirit, amen .” (translated by Prof. John Lowden, Courtauld Institute)

But it is the final illustration of the birth chamber itself that gave me the eerie feeling that I was in the presence of the past.

The Birthing Chamber – BL Egerton 877 f. 12 (public domain image)

The text says: “The Father is alpha and omega, the Son is life and the Spirit is medicine. Thanks be to God”.

In this image we see the mother who has just given birth lying in the bed, and the midwife holding the swaddled infant. On the right, I believe that the figure under the canopy is Saint Margaret. Holy people are often given this architectural device. But the paint on this side of the page is so smeared and distorted through repeated kissing, it is hard to make out the full figure. As Professor Lowden says in his description:

“How many times was this page devotedly kissed by women in fervent hope that their childbirth might leave them ‘unharmed and without any pain’? And if the worst happened and their child was stillborn how many women prayed in anguish, with the help of this little book, that their labour might still end safely?”

Through this poignant trace of desperation, I could imagine myself into the lives of these women, even as I remembered the birth of my own son, after a long, stalled labour that would have killed us both in the thirteenth century. I started thinking about the consequences of the large number of deaths in childbirth, and particularly what would happen to a surviving baby whose mother had died. And so the plot began to take shape in front of me, like a detailed picture being drawn before my eyes.

The Errant Hours begins in that final illustration, with the difficult birth of the heroine of the story, Illesa (‘unharmed’ in medieval Latin) in 1266. The action continues when she is a young woman and her midwife mother has recently passed away leaving her a richly decorated book, a Passion of St Margaret, which, as a poor woman, she should never have possessed.

The Errant Hours is an adventure, following Illesa as she struggles to save her brother and herself in the face of poverty, violence and corruption. But it is also the story of a daughter who loses and finds a mother, the story of a sacred book believed to have the power of life and death, and the story of how a young woman negotiates the physical and spiritual dangers of Plantagenet Britain, and survives to come of age.

These stories intertwine, bind, resist and console each other, as all our stories do.

****

Kate Innes was born in London and raised in America, returning to the UK in the 1980’s to study Archaeology. She taught in Zimbabwe before completing an MA and working as a Museum Education Officer around the West Midlands. She now lives in Shropshire. Her first novel, The Errant Hours, has been added to the reading list for Medieval Women’s Fiction at Bangor University. Kate has been writing and performing poetry for many years. Her collection, Flocks of Words, was published in March 2017. Kate runs writing workshops and undertakes commissions and residencies.

@kateinnes2

May 4, 2017

Review of ‘Flocks of Words’ – The Book

I’m very grateful to Pat Edwards (website mashup arts ), organiser of Verbatim Poetry on the Welsh Border, for reading and reviewing my new collection – Flocks of Words. It’s a strange but satisfying feeling following another poet’s journey through one’s own work; finding some ideas that are very familiar, and others – startlingly new!

Flocks of Words – Kate Innes – reviewed by Pat Edwards

Writers who attempt the risky game of trying to describe the process of writing, or their love of language, may do so at their peril. Not so Kate Innes, who in the carefully crafted metaphor of the title poem depicts the reappearance of words as a cyclical event. Referring to Eden and to “god’s purpose”, we feel an echo of Luke’s advice about ravens as we stand “watching the words return”. We need not be concerned as we can feel the writer wanting to collect and nurture words, keep them safe whilst they are in her care, knowing they will fly away when the season demands.

In the five sections of this collection, Innes takes us on what many might make into an epic journey. The themes are the very stuff of creation and the pattern of decay and renewal that shapes the physical and spiritual landscape both. However, Innes adopts a kinder, more human touch as she quietly feels her way through the elemental, exploring paths, forests, time, water, firmament, light. Occasionally, she stops for breath as in ‘Breton House’, where “the old English painter” captures a pastoral scene.

In ‘Red Stag’ Innes imagines herself in the body of an animal, hunted until she is hit, “a flood of blood in (her) belly”. In ‘The Other Land’ she speaks of all “the places in between”, the silences, cracks, “like teeth behind a kiss”. The poet clearly loves the English landscape, its myths and legends, but also finds inspiration in art, ranging from the primitive as in ‘Reindeer Hunt’ to the more classic such as in ‘Virgin and Child’ where the exhortation of Luke to remain “unconcerned by cold and hunger” is re-visited.

Parts iii and iv focus on water, the hunter and the prey, animals and evolution. Always death lurks, even in the fleece worn by the spring lamb, “that supple shroud”. In the final part, a sequence of poems inspired by the stained glass of Margaret Agnes Rope, Innes is never far from light, animals, water, the familiar themes of this collection.

In all, there is much to please and excite the reader, especially if you share her fascination with the existential and with how we make sense of our place in a changing natural world. I enjoyed the collection as it made me reconsider some of these ideas from a new perspective and exposed me to the poet’s own unique and very beautiful mastery of language.

January 19, 2017

Ear worms and El Supremos

Sometimes I get an ear worm that seems particularly relevant to my life at that moment in time. I’m sure this happens to a lot of people. It’s slightly less annoying than just having an insipid, meaningless song haunting your every waking minute. Sometimes it can even be quite comforting. For example, just after the 23rd June, 2016 the song going through my head was Thomas Dolby’s ‘Europa and the Pirate Twins’ –

Europa, my old friend-

We’ll be the Pirate Twins again

Europa

Oh my country.

Europa

I’ll walk beside you in the rain

Europa

Ta republique

I was very sad. But I was being sad with Thomas Dolby.

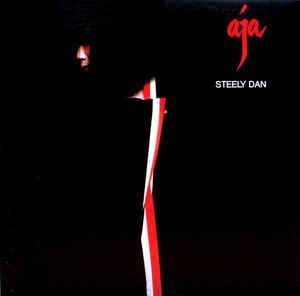

More recently for me, it’s been exclusively Steely Dan songs.

I know. I know. Ancient history. But having three children aged 11 – 15, I do have to listen to a great deal of contemporary music, so when I’m given a choice of listening, I turn to my old favourites. And Steely Dan was one of the best things about growing up in the seventies and early eighties in America. They were intelligent, they were cool, and they were so random before randomness was appropriated by people who were being intentionally stupid.

They were interested in little things, tiny details of our daily shabby life, as well as disappointment, death, drugs, sex and taxes. And of course there was the brilliance and originality of their arrangements – their mingling of jazz and rock.

Before Christmas, as I shopped, wrapped, broke up fights, cleaned, cooked, washed up, applied make up, looked for lost tags/tape/presents/socks and organised large scale mulled wine distribution, the phrase going through my head was from ‘Black Cow’ (Aja 1977).

I don’t care anymore

Why you run around

Break away

Just when it

Seems so clear

That it’s

Over now

Drink your big black cow

And get out of here

For reference a ‘Black Cow’, in this context, is a cocktail made of coke, cream and Khalua. Not to my taste, but any alcohol, even super sweet fantasy alcohol, is better than none when you are in the midst of the festive season and properly exhausted. And alcohol with a dose of attitude is even better.

I recovered from the holiday, and for the past two weeks I’ve had the glorious ‘Show Biz Kids’ in my head, with its catchy backing vocals:

You go to Lost Wages, Lost Wages, you go to Lost Wages.

This is not because I am chasing invoices. Although I am.

Lost Wages is a pun for Las Vegas, from a joke by Lenny Bruce.

I didn’t know that before I googled it. It was always one of those lyrics that you can’t quite work out. Box Pages, or something else deep and meaningless. I happily sang along for years.

The song goes on with this summary of a certain type of celebrity:

Show biz kids making movies

Of themselves you know they

Don’t give a fuck about anybody else

So I have now realised why this song is going through my head at this particular time – as the 20th January 2017 approaches and it has become clear that no one is going to stop Trump becoming the actual, real, honest-to-God President of the United States.

Donald Trump – the celeb, show biz star, casino owner and tycoon epitomises the widespread belief that the appearance or the promise of goodness and success is so much more important than the actuality of it. The obsession with perfection in appearance (particularly for women) is part of this phenomenon, as is a type of reality tv performance combined with conspicuous consumption that is designed to make us admire what the celebrity has, rather than what they have done.

The aspirational part of this is a powerful force. It appeals to the risk taking side of us all. The person who wants to believe in something that is too good to be true. The person who doesn’t want facts. The Gambler.

‘Look’ – says Trump, the arch fact-unraveller, ‘it can all be so great. You can win. Win BIG, and I can make it happen.’

It is the same false promise made to everyone who enters a glittering casino in Las Vegas with its glamorous staff and plentiful drinks, and leaves without their wages.

I have no wish to spend many more words on Trump. He is over described already.

But it is so clear to me that he is only in this for himself. That in all he has done, his self aggrandisement and business ventures, his bullying, belittling behaviour, his outrageous lies and his willingness to use women against their will, he has sought pleasure, power and money at the expense of those who are weaker and lack influence.

He certainly doesn’t seem to give a fuck about anybody else.

The fact that so many Americans thought this was an appropriate quality for the President of The United States is hard to take. But then when we look to history, it is littered with men like him who convinced people that through brutality they could get the change they wanted. That to make change you need a hard man, a strong man. That the people who suffer from the brutality will be people on the outside, not the inside. (Celts in the past – Mexicans or Muslims today.) And that they deserve to suffer because they are bad, nasty people.

But the truth will be different.

Inevitably, the facts will come.

And like fanatical bailiffs, they will extract profit for Trump, and the other ‘El Supremos’ of the world, from everyone.

‘Show Biz Kids’ from Countdown to Ecstasy 1972

CHORUS:

While the poor people sleepin’

With the shade on the light

While the poor people sleepin’

All the stars come out at night

After closing time

At the Guernsey Fair

I detect the El Supremo

From the room at the top of the stairs

Well I’ve been around the world

And I’ve been in the Washington Zoo

And in all my travels

As the facts unravel

I’ve found this to be true

CHORUS

They got the house on the corner

With the rug inside

They got the booze they need

All that money can buy

They got the shapely bods

They got the Steely Dan T-shirt

And for the coup-de-gras

They’re outrageous

CHORUS

Show biz kids making movies

Of themselves you know they

Don’t give a fuck about anybody else

CHORUS

Writer/s: DONALD JAY FAGEN, WALTER CARL BECKER

Publisher: Universal Music Publishing Group

Lyrics licensed and provided by LyricFind

December 8, 2016

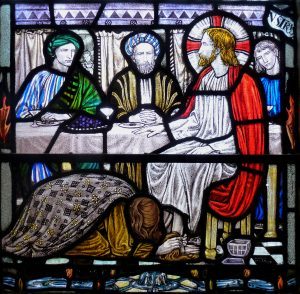

Heavenly Lights – a writer’s response to stained glass

A few months ago, I happened to see an image online which showed a section of a window designed and created by Margaret Agnes Rope (1882-1953). Despite having lived in Shropshire for more than 20 years, I had never heard of Margaret Rope, who was born and worked in Shrewsbury, and is now acknowledged as the greatest artist ever to have been born in Shropshire. I was very taken with the beauty of the natural scene and the contrast of the sinister beasts creeping around it. I sensed a great imagination at work in these images and felt stirred to respond. Since then I have had the privilege to become the poet in residence at the Heavenly Lights exhibition of Margaret Rope’s work at the Shrewsbury Museum & Art Gallery museum website

Detail of a window in Shrewsbury Catholic Cathedral

Margaret Rope was one of the finest stained glass artists of the Arts & Crafts Movement, although she has never been famous. Her work is characterised by jewel-like colour, fine painting, an ambitious vision and incredible detail informed by meticulous research. The Margaret Agnes Rope Project is attempting to make her work better known, and has made available on their website (https://margaretrope.wordpress.com ) a great deal of fascinating information about her life and achievements, which I need not replicate.

Suffice it to say that Margaret Rope (known as Marga to her family) had an independent and sometimes rebellious spirit from an early age. Stories of her exploits on motorbikes, sleeping out on the roof in all seasons and being falsely arrested as a spy give an impression of an indomitable person of great individuality. In her late teens, after the death of her father, Margaret, along with many other members of her family, converted to Catholicism. At the time Catholicism was tolerated in British Society, but much frowned upon. As a result of this conversion, Margaret, her sisters and her mother were written out of her grandfather’s will. There was not much money for the large family, and Margaret knew she would have to earn her keep.

It was unusual then for women to become stained glass artists, and it still is. It is a very demanding art form, dominated for centuries by men, perhaps because of its association with monasteries. But Margaret found an art school in Birmingham which accepted women, and from there, she ploughed her own furrow in the second generation of the Arts & Crafts Movement.

Jesus and Mary Magdalene

Margaret Rope’s art was inextricably entwined with her faith. She made windows for all kinds of places of worship, but her masterpieces were, in the main, Catholic topics created for Catholic churches, such as Shrewsbury Cathedral. In 1923 at the height of her powers, she chose to enter an enclosed order of nuns, the Carmelites, and lived within the walls of the convent until her death. She was able to continue her production of stained glass, but not to see the windows (which were installed in countries around the world) in their finished form, except the few which were made for the convent chapel.

A fascinating woman. A great artist. But I have become especially intrigued by the stories behind the art. I’ve had a life-long interest in mythology, folklore, religious stories, and also with the representation of animals and the natural world. Margaret’s work is packed with symbolic details, similar to the highly decorated margins of medieval illuminated manuscripts. The space in her windows is teeming with life; many species of birds, flowers and trees painted with remarkable accuracy. And like me, she seems to have been fond of dogs (I found seven representations of dogs in the exhibition).

The intertwining of images of great natural beauty with scenes of death, cruelty and sin gives the windows authenticity. They never claim that faith is easy, nor that it will lead to a life of pleasure and goodness. Margaret did not shy away from the difficult topics, including the painful deaths of the catholic martyrs and other saints. In her windows, we see darkened streets, bleakness, the devastation of broken relationships, as well as the prosaic details of life, the importance of daily rituals, candles and procession, to bring light.

So in a nutshell, I have found ample scope for my poems and some fascinating characters in this exhibition including: Judith and Holofernes (woman who seduced and decapitated an invading general), Goblin Market (the decline and near death of a young girl after yielding to supernatural temptation) and St Francis of Assisi (a rich man who leaves everything for a life of extreme poverty and is able to speak to animals).

Student work – Judith and Holofernes

The other topic which comes back time and time again in Margaret’s work is that of war. She lived through both World Wars and ironically received many commissions due to the death toll of the First World War in particular. Stained glass windows were the memorial of choice for wealthy families whose sons had been killed. I wonder how Margaret felt about this uncomfortable causal relationship between death and suffering, and her own livelihood.

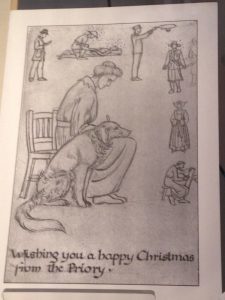

I was particularly touched by an early Christmas card she drew from The Priory, the family home in Shrewsbury, which is exhibited in one of the glass cabinets.

Christmas Card by Margaret Rope 1916

In it we see a central figure writing or drawing, with the family dog at her knee. Around them, the members of the family work in various ways to help the war effort. It is hard to put myself in the place of those who struggled through one devastating war, only to be confronted with another a generation later. The devastation to society, as well as the individual psyche, is something I shrink from but also feel the need to understand. Especially now, as the rhetoric of far-right groups seems to intensify every week.

In this poem, one of the nine currently displayed in the exhibition, I try to think myself into that Christmas time, one hundred years ago during the war. It has brought home to me how lucky we are to have lived during a time of peace. And how fragile that peace is.

Tidings of War

What can comfort in time of war?

Only the way a pencil line

stays fixed – can trace

a gasping stretcher

or a searchlight’s arc –

ordering the dark.

And for those who sit waiting

on cold chairs,

keeping a window lit

to welcome others home?

Only the weight of a soft muzzle

on the lap, alive and warm.

Only the escape of service,

the brain-haze of heat,

a hat’s fragile shade,

un-blistered feat,

for those who work in rust-red

fly-ridden fields.

And for those who lift and carry,

who hold the cold hand and cry

at the way the world

has launched itself,

like a thin-spun ball of gas,

and set a match

and hurtled down to its own destruction,

while some men just watch

and warm their hands?

There seems none.

But we must not hide,

we must not snuff out the light,

so here – I send you hope for peace

this Christmas-tide.

Kate Innes

The exhibition is at Shrewsbury Museum & Art Gallery until the 15th January 2017.

Sister Margaret’s Memorial

November 28, 2016

History and its Mysteries

The Roman Forum (photo by traveldigg)

A while ago I was asked to introduce Lindsey Davis, who was speaking at the inaugural Shrewsbury Literature Festival on Saturday the 26th November, 2016. As part of introducing this grande dame of historical crime, I was invited to say a few words about my own writing, and some of the points of cross-over. What follows is the talk I gave, which I hope properly expressed my admiration for Lindsey and what she has achieved.

I am delighted to be here today at the inaugural Shrewsbury Festival of Literature to introduce our guest – Lindsey Davis.

It is a privilege to share the stage with you Lindsey, and I am very much looking forward to your talk. In the meantime, I have a few minutes to speak about this interesting type of literature, Historical Fiction, why we write it and why we love to read it.

I’m interested in how we become intrigued by history. The past is gone after all, and on we go into an ever disappearing future. So what draws us back to the things that are long gone?

Everyone has their own experience, but in my case, and I am sure for many others, the introduction to history comes through stories set in the past, in other words Historical Fiction. I suspect that good historical children’s books have done more for our understanding of the past than all our school history lessons.

I grew up in the USA on the East coast. There the earliest buildings are 250 years old, and most are less than 50. The history taught was almost exclusively American. I relied on literature, through our excellent local library, and on Museums to teach me about the world and its past. And early on I came to be fascinated by Greek and Roman mythology.

This laid the groundwork for my interest – but to become a proper history addict there is nothing like being able to touch the real thing.

The Roman Forum

One of my most formative moments, was in the early 80’s as a RaRa-skirted 14 year old on a school trip to Greece and Italy. We stayed in Rome and visited the Forum. The sheer scale of the remains astonished me. Carved capitals, the outlines of shops, walkways, temples. The imprints of both the daily grind and the metaphysical. What I felt on that day stayed with me and never let go. By the end of high school I had made up my mind. I would go to England and read Archaeology at University, and have that thrill all the time, the sense of touching the past.

But as we know, not everything is quite as you assume when you are a young adult. Archaeology, it turned out, was much more about resistivity meters, microscopic sections of pottery and Carbon dating than it was about my more romantic notions of reaching into history.

After my Archaeology degree, I turned to teaching and then to Museum studies, becoming a Museum Education Officer

Perhaps you are thinking – that is all very well. Kate and Lindsey share a love of the past. Particularly the classical past. But what about the CRIME?

Well, I have also done my time in crime. About 22 years ago, between careers, I had a job in a bookshop on Manhatten’s Upper East Side which sold exclusively Crime and Mystery books. It was called ‘Foul Play’. In those days, most people who were looking for information about businesses would look in the phone book. With a name like ‘Foul Play’, we had quite a few phone calls from people assuming our services were of quite a different nature to book selling.

Of course, it does not necessarily follow that avid readers and booksellers become writers. Personally, I knew from a very early age that making up stories, creating new worlds for the reader, was a superpower I wanted to possess. And to time-travel as well, by writing about past civilizations – that would be the ultimate trip.

The first stop in my time travelling journey was the Medieval period. My debut novel The Errant Hours is set in the 13th century AD, in the Marches and North Wales just after the end of the Second Welsh War.

It is a love letter to this part of the world, with its stunning historic and prehistoric landscape. It is an adventure that gallops through most of the medieval monuments in South Shropshire at a heart-stopping pace. It is also an exploration of the power of books, stories and legends.

And at the heart of it, there is a young woman in possession of an extraordinary book, a manuscript describing the Martyrdom of St Margaret of Antioch. In other words, the manuscript is a work of Historical Fiction.

The saints who were worshipped in the Middle Ages attained their positions mainly thanks to Roman persecutions of the upstart Christian religion. The accounts of these crackdowns were embellished by later writers into pious and bloodthirsty tales, to encourage veneration of the saints. So when I came to write ‘The Errant Hours’, I had a perfect excuse to include a section that goes back to the Empire.

St Margaret of Antioch was a virgin martyr, and her story is typical of the genre. Daughter of a pagan priest, she converts to Christianity against his will, and is disowned. Then, as she wanders amidst the goats on the pastoral hillside, she is spotted and desired by the Roman governor. He insists upon ‘marrying’ her. He also insists that she renounce her faith. She refuses. So he has her tortured in various horrible ways before she is beheaded in front of a large crowd.

How this VIRGIN ended up becoming the medieval patron saint of Childbirth is a fascinating story, and one I explore in my book. But in writing about her, what I really wanted to know was – without all the later religious spin – what would it really have been like to be a young woman of the Roman Empire, who was imprisoned and tortured for her faith?

St Margaret thrown into prison, and later emerging from a dragon. The Taymouth Hours, BL Yates Thompson MS 13, early 14th century

Perhaps I should have looked at some other saint, who had a really friendly story with a happy ending.

But, in spite of the gore, I was thrilled to be imaginatively back in the midst of Roman culture, their buildings, their admirable sense of order, their productivity and their pragmatism. Writing is the ultimate Virtual Reality head-set, in my opinion. I cannot explain the deep-seated desire I have to be in that state of the imagined past, but perhaps it has something to do with never knowing what will happen next in real life, and needing a place of escape. I suspect that most readers feel similarly, in wanting to experience the best and the worst of life, but in a safe environment.

Lindsey Davis has been treating people like us to immaculately researched, accurate and entertaining stories set in Ancient Rome for three decades. She has peopled the ruins with restaurant owners, politicians, merchants, lovers, whores, and most significantly informers. Marcus Didius Falco and his daughter Flavia Alba are fully rounded people, not characters. Through them we experience the rest of the Roman Empire, explained with, at times, frustrated affection.

And what a close relationship there is between the activities of Falco and Flavia – and our own efforts as writers of historical fiction.

For don’t we have to examine the remaining evidence, the records of the lives, the scenes of the action. We must hold in our mind the pieces of this puzzle and fit together the fragments of ‘truth’. Then the imagination creates the story and the motive – and it provides an explanation of the mystery: What was it like to experience the push and pull of a particular economy, culture and belief system? And what punishments will come?

Lindsey’s observations don’t only enlighten us about the Roman Empire, she also makes us see and celebrate our own culture and our modern world in the light of history.

Whilst researching for this event, I was delighted to find on Lindsey’s website a section entitled ‘Rants’.

We all can appreciate the satisfaction of a good rant, I’m sure.

Upon being told by the large and rather insular American market that her books must be americanised, she only capitulated on spelling. She would not change her particularly British use of words and tone to suit the American ear. My heart was gladdened when I read her words in defense of this position:

“The Falco books are English in origin. Their ‘voice’ is not only English, but narrowly defined on occasions right down to the bolshie British Midlands, in the mid Twentieth Century, with influences from BBC Radio and middle class girls’ education. This voice is crucial. If it means readers have to stretch themselves, then gung-ho and jolly good show.”

And surely that is one of the things we want from a good book, to learn something, to work things out and feel satisfied when we have come to a new understanding. Besides, the joy of a Lindsey Davis novel is in its facility with language, idiom and a sharp turn of phrase. Any number of quotes would prove this point. But let me take one from her recent Flavia Alba novel, ‘Enemies at Home’:

“We now had a paranoid emperor, who at just short of forty was still young enough to inflict many years of dread upon us. Our empire’s borders regularly came under attack from barbarians, so there was constant unsettling military talk. The city was also full of bitter satirists, outlawed philosophers and pouting poets who had failed to win prizes. In this climate, all kinds of madness flourished.”

What a prescient passage. If any country needs to learn from and listen to the outside world, it is America and its leader at this present time. And I’m sure those of us who frequent Facebook will recognize what a frenzied atmosphere can erupt from a glut of satirists, philosophers and poets.

It is my great pleasure to welcome, therefore, one of our own. A multiple prize-winning writer born in Birmingham, who has delighted millions of readers with her humour, her insight, her lightness of touch in the face of gruesome crime – and her productivity.

After 20 Falco and four Flavia Alba books, as well as wonderful stand-alone novels, we all hope there will be more and more and more.

Please welcome Lindsey Davis.