Holly Walrath's Blog, page 2

February 6, 2025

The Horror Short Reads Bundle

Interstellar Flight Press is participating in the February Horror Short Reads Bundle from StoryBundle! For $20, readers can get 22 horror novellas, including Small Gods of Calamity by Sam Kyung Yoo.

This bundle is curated by Mike Allen, who has this to say about the stories:We live in a new golden age for horror fiction, spurred by surging readership and technological advances in publishing, and no form of narrative has benefited more from this renaissance than the horror novella.

The notion that novellas prove the best vessels for horror has for decades been the conventional wisdom among connoisseurs. The incontrovertible evidence dates back to masterpieces like J. Sheridan Le Fanu’s “Carmilla,” Algernon Blackwood’s “The Willows,” Henry James’ “The Turn of the Screw,” H.P. Lovecraft’s “The Shadow Over Innsmouth,” and many others. Recent decades continued this excellence — consider the stories collected in Stephen King’s Different Seasons, or Clive Barker’s “The Hell-Bound Heart,” Elizabeth Engstrom’s “When Darkness Loves Us,” or Victor LaValle’s “The Ballad of Black Tom,” to name just a few.

The short novels and novellas that I’ve assembled for this Horror Short Reads e-book bundle are sure to introduce you to new favorites and reacquaint you with favorites from the past.

This overflowing cornucopia of a StoryBundle explores all the permutations of the horror novella, providing 22 tales of terror penned by 21 authors, ranging from career grand masters to up-and-comers making their debuts. These bodybag-wrapped meaty morsels include 18 standalone novellas and short novels, plus the anthology A Sinister Quartet, which holds four more novellas.

You’ll find pulse-pounding thrillers and slow-burning noir, supernatural and psychological terror, narratives mind-bending and straightforward, the bloody and the subtle, even dark humor.

For those who love a good scare, horror can be comfort food, a thrill ride of the soul that’s completely under your control, even as the words on the page make you feel shiveringly otherwise. There’s fuel here for many an enjoyably sleepless night. Bon appétit! — Mike Allen

Head over to StoryBundle for more info!

[image error]

[image error]The Horror Short Reads Bundle was originally published in Interstellar Flight Magazine on Medium, where people are continuing the conversation by highlighting and responding to this story.

February 5, 2025

Introducing The Best of Interstellar Flight Magazine: Year Five

Our Favorite Articles of 2023 in Print and EBook Format

Step into the captivating realm of Interstellar Flight Magazine, your go-to online destination for all things speculative nonfiction. In essays, interviews, and reviews, talented contributors from across the globe explore the worlds of science fiction, fantasy, and horror through books, film, TV, comics, games, and art. In this selection of nonfiction from 2024, the anthology dives into topics such as Horror’s final girl, UFOs, true crime podcasts, video games as escapism, book banning, small press publishing, translating books, and more. These essays give insight into popular SFF creators like Ray Bradbury, Shirley Jackson, Stephen King, Mike Flanagan, and more. Find the answers to questions like: Why is Gremlins a cult classic? What did Jordan Peele mean by miracles in Nope? and Why Aren’t There More Fear Street Movies? Think of Interstellar Flight Magazine as a time capsule preserving the vital conversations shaping the speculative landscape today.

Table of ContentsEditors NoteOriginal Articles

The Never-ending Tedium of Survival: a Long-form Essay on the Final Girls Who Struggle to Stay Alive Again and Again and Again

by Andrea Blythe

The Sega Saga as Told by a Kid Trying to Escape: A Personal Essay

by Salena Casha and Mahailey Oliver

UFOs and the Link to Ancient Indian Literature: A Deep Dive Into Fascinating Futuristic Technology from the Past, with Brishti Guha and Indrani Guha

by Brishti Guha and Indrani Guha

The Lotus Eaters: A Longform Essay on Addiction in the Works of Edgar Allen Poe, Shirley Jackson, and Stephen King

by Grant Butler

Why Do We Keep Inventing the Magical School?: From T.H. White to Ursula K. Le Guin, Hogwarts Isn’t the Only School in Fantasy

by Tanvi Chowdhary

Five Horror Movies That Reflect Our Times: The Power of a Powerful Message in Contemporary Horror

by Ryan Fay

“Fallen Women” in Fantasy: Sex Work as Characterization in Popular Fantasy Novels and the Complications Therein

by Alex Kingsley

How Science Fiction and Fantasy Can Help Authors and Readers Fight Book Banning: Fahrenheit 451 and The Book Thief Teach the Power of Reading

by Priya Sridhar

I’m (Not) What I Write: That Time I Went Viral on Twitter for Being a “Scary” Horror Author

by Robert P. Ottone

Is It Frankenstein’s Creature or Monster? A Retrospective on Two Early Frankenstein Films

by Ryan Fay

The Mash-Up Mythos: A Parent’s Guide to the Monsters Your Kids Are Obsessed With: Kids Horror from Gaming to Memes to McDonald’s

by Patrick Barb

The Nature of Fear: What Truly Terrifies Us Are the Horrors Haunting Us from Our Childhood

by Christina Sng

The Small Press Horror Renaissance: Six Indie Presses Publishing Horror to Add to Your TBR Pile

by Ryan Fay

Horror Hostesses with the Most-Esses: Late-Night Horror Hosts from Vampira to Elvira

by Ryan Fay

Did Ray Bradbury Predict the Smart House in “The Veldt”? Can the House Replace Us?

by Priya Sridhar

The Witch of the A&P: A Horror Author Looks Back on Childhood Terrors

by Patrick Barb

From Spooky Lovers Lovers to Amantes Espeluznantes: One Book, Two Languages: J.V. Gachs on the Process of Publishing in Multiple Languages

by J.V. Gachs

Gremlins: Secretly a Cinematic Masterpiece?: One of the Most Polarizing Horror Films in Existence

by Alex Kingsley

Underwater Civilizations, Action Against Oppression, and Friendship: Review of Weird Fishes by Rae Mariz

by Archita Mittra

The Horror of Women’s Pain: On “The Retrievals,” a True Crime Podcast from the NYT and Serial Productions

by Holly Lyn Walrath

A Guide to Becoming an Elm Tree Blends Gripping Folklore with Subtle Body Horror: Irish Horror Film Mesmerizes with Tale of Old Gods

by Patrick Barb

Why There Should Be More Fear Street Films: Netflix’s Horror Film Trilogy and Teen Horror

by Chloe Smith

Journeys Through the Radiant Citadel: A Spellbinding Anthology of Thirteen Short Adventures Set in the Dungeons & Dragons Universe, All Conceived and Written by People of Color

by Archita Mittra

Dinner on Mars Gives Food for Thought

by Lisa Timpf

Saltburn Drips Sexuality and Intrigue: Barry Keoghan, Rosamund Pike Devastate in This Dark Masterpiece of Desire

by Holly Lyn Walrath

Queer Representation in Supermassive Games: BAFTA-Winning Game Studio and Queer Gamer Culture

by Vanessa Maki

Anne Hathaway Shines in Eileen, a Story of Unrequited Love: Stuck in Massachusetts in the 1960s

by Holly Lyn Walrath

Five Nights at Freddy’s Offers a New Gateway to Horror: But More Experienced Fright-Flick Fans Will Want to Wait for a Level-Up

by Patrick Barb

Ashin of the North Review: The Final Girl Brings the Fire

by Christina Sng

The Toxic Avenger Reboots “Toxic” Hero: The Toxic Avenger Premieres at Fantastic Fest Starring Peter Dinklage, Kevin Bacon, and Elijah Wood

by Holly Lyn Walrath

Haunted House and Cursed Land: Mombauer’s The House of Drought Blends Gothic and Folk Horror in Timely Climate Change Novella

by Patrick Barb

Bad Miracles and Other Spectacular Things in Jordan Peele’s Nope: Surviving Trauma and Memory

by Gretchen Rockwell

A Game of Shadow and Bones: Netflix’s YA Fantasy Show and the Changing Art of Book Adaptations

by Hesper Leveret

Black Mirror Season 6 and the Power of Situational Horror: What Writers Can Learn About Storytelling from the Popular Netflix Series

by Holly Lyn Walrath

Finding a Place in the Medieval: Thinking Queerly by Jes Battis Jousts with Tradition

by Lisa Timpf

Dark Poetry Abounds in Where the Devil Roams: Set at a Carnival in the Great Depression, the Latest from the Adams Family Is a Rotten Riot

by Holly Lyn Walrath

The Only Way to Survive the World Burning: Review of Bridging Worlds: Global Conversations on Creating Pan-African Speculative Literature in a Pandemic

by Taylor Jones

Strange Darling Flips Script on Serial Killer Movies: JT Mollner’s Second Feature Film Explores the Gender Dynamics of Murder

by Holly Lyn Walrath

Mike Flanagan’s House of Usher Stands on a Firm Foundation: All That We See or Seem…

by R. Thursday

South Korean Film Sleep Weaves Sleep Disorders, Magic, & Marriage in Heartfelt Love Story: Debut from Jason Yu Explores Horrors of Sleepwalking

by Holly Lyn Walrath

The Creator Props Up Hyper-Optimism with Gorgeous Visuals: But Does It Succeed?: Gareth Edwards’ New SF Flick May Leave a Bad Taste in the Mouth of Those Worried About AI

by Holly Lyn Walrath

A Shadow of Reincarnation in a Solarpunk World: Review of Another Life by Sarena Ulibarri

by Megan Wegenke

There’s Something Familiar About There’s Something in the Barn: Norwegian Holiday Horror Comedy Is National Lampoon’s Meets Gremlins

by Patrick Barb

Moving with a Monument: Art, Archaeology, and Artificial Intelligence, Research Questions and Project Beginnings

by T.D. Walker

Interview with Roboticist Daniel Williams and Master Craftsperson Justin Green, Collaborators on Sacrifice: Can You Trust a Stone? at the University of Melbourne

by T.D. Walker

Immortality, the 1960s, and the Power of Women’s Voices: An Interview with Gwendolyn Kiste, Author of Reluctant Immortals

by Andrea Blythe

D&D in Full Color: Interview with Ajit A. George, Editor of Journeys Through the Radiant Citadel

by Archita Mittra

Toxic Relationships and Greek Mythology: Interview with Jordan Kurella, Author of I Never Liked You Anyway

by J.Z. Weston

Hope, Horror, and Queerness: An Interview with Lucy Hannah Ryan, Author of You Make Yourself Another

by J.Z. Weston

Old Legends Through the Voices of the “Things and Beasts” Therein: Interview with Melissa Ridley Elmes, Author of Arthurian Things, a Collection of Poems

by T.D. Walker

Apocalypse and Perseverance: COVID, Science Fiction, and Poetry of Survival: Interview with Jeannine Hall Gailey, Author of Flare, Corona

by T.D. Walker

Caught Between Two Worlds: Family, Far Away Places, and Formal Poetry: Interview with Lindaann Loschiavo, Author of Apprenticed to the Night

by T.D. Walker

STEM, Women Scientists, and Sexism: Interview with Jessy Randall, Author of Mathematics for Ladies: Poems on Women in Science

by T.D. Walker

Seasons of Questioning: Grief, Parenting, and Navigating Illness: Interview with Emily Hockaday, Author of Naming the Ghost

by T.D. Walker

Scholarship, Song, and the Supernatural: Interview with Kendra Preston Leonard, PhD, Author of Grab

by T.D. Walker

Short SFF, Day Jobs, & Late Night TV: An Interview with William Ledbetter, Author of The Long Fall Up: And Other Stories

by Holly Lyn Walrath

Out of the Earth, Out of the Closet: Mythmaking and Queerness: An Interview with Maxwell I. Gold, Author of Another Mythology

by R. Thursday

Disability, Queerness, & Poetry as Community: Interview with Ennis Rook Bashe, Author of Beautiful Malady

by Julie Reeser

Interstellar Flight Magazine publishes essays on what’s new in the world of speculative genres. In the words of Ursula K. Le Guin, we need “writers who can see alternatives to how we live now, can see through our fear-stricken society and its obsessive technologies to other ways of being, and even imagine real grounds for hope.” Visit our Patreon to join our fan community on Discord. Follow us on Twitter, Facebook, or Instagram

[image error]Introducing The Best of Interstellar Flight Magazine: Year Five was originally published in Interstellar Flight Magazine on Medium, where people are continuing the conversation by highlighting and responding to this story.

February 3, 2025

Introducing Level Seven by William Ledbetter

“…a propulsive techno-thriller that steps outside the well-established tropes of a scientist struggling to save the world from being taken over by AIs who see no further need for humanity.” — Mike Finn’s Fiction

The thrilling final installment in the Killday Series by Nebula Award winning Author William Ledbetter

The brutal Kilburnites finally destroyed all Artificial Intelligences on Earth and reclaimed the planet for humanity. Or did they? Less than a year later, huge structures are growing amid the ruins of the once-great cities, and they aren’t being built by humans.

Abby Gibson and her AI partner Mortimer, who barely survived the purge on Earth by escaping to space, are again forced to fight for their lives. This time, the enemy is something they don’t understand from the cold vacuum of the asteroid belt, which has set a course to destroy the space habitat she calls home.

In Level Seven, the exciting culmination of the Killday series, human existence hangs by a thread as AIs strive to evolve into a super-intelligent god, and the survival of both species might come from their unlikely alliance.

“An excellent but surprisingly dark near-future SF.” — Alex ShvartsmanAbout the Author

William Ledbetter is a Nebula Award winning author with two novels and more than seventy speculative fiction short stories and non-fiction articles published in five languages, in markets such as Asimov’s, Fantasy & Science Fiction, Analog, Escape Pod and the SFWA blog. He’s been a space and technology geek since childhood and spent most of his non-writing career in the aerospace and defense industry. He is a member of SFWA, the National Space Society of North Texas, and a Launch Pad Astronomy workshop graduate. He lives near Dallas with his wife, a needy dog and three spoiled cats.

Exclusive Interview: "The Long Fall Up" Author William Ledbetter .. .

[image error]

[image error]Introducing Level Seven by William Ledbetter was originally published in Interstellar Flight Magazine on Medium, where people are continuing the conversation by highlighting and responding to this story.

November 9, 2024

Call for Submissions: Infinite Branches: Queer, Speculative Disability Poetry in Conversation

Interstellar Flight Press is seeking poets who are both queer/trans and disabled for a special collaborative series in 2025, to be published at Interstellar Flight Magazine. Our guest editor for this call is Toby MacNutt. This call is different than our past calls: Please read the guidelines carefully.

Guest Editor’s Biography

I’m queer, nonbinary (they/them) trans-masculine, chronically ill, autistic, and a speculative poet. I’m a white person living in rural Vermont (US), and also a textile artist, teacher, and dancer. I won’t be choosing your poems — I’m here to facilitate the process. I’m an experienced facilitator, and my goal is to support your work in the way you want it to be read. I can provide access support for group conversations, prompt questions for writing your statement or explore it in conversation for transcription, facilitate group conversation, help with files and sharing. I’ll also be working with poets to create content warnings as needed, and can offer feedback or light edits on work.

You can find out more about me on my website, www.tobymacnutt.com or say hi on Instagram @tobymacnutt or mastodon @tobymacnutt@wandering.shop

Description

In this round-robin series, the poems are selected by the poets and positioned in the context of one another. One poem leads to a responding poem from another poet, with a short statement on the reasons for their choice and whatever else they’d like to share about it. Each pod of six poems concludes with a group discussion of what we see when our work sits next to each other (and we’re still there with it, still in the room). What themes and variations emerge? What unique things are we doing with the form? What about your work is understood by your peers in ways out-group editors can’t keep up with? Let’s find out!

We’re looking for speculative poetry from poets who are both queer/trans and disabled, with all these categories being broadly defined:

speculative poetry: poetry that includes some element, large or small, outside of what is generally considered reality, whether it be fantasy, science fiction, slipstream, fabulism, surrealism, alternate history, or something else entirelyqueer and/or trans: the whole queer umbrella, including bi and pan, gay, lesbian, ace/aro, demi, and more, and the whole trans umbrella, binary and non, transitioning and non, including agender, bigender, genderfluid, genderqueer, two-spirit, and othersdisabled: including but not limited to poets with chronic illness, neurodiverse poets, Mad/mentally ill poets, d/Deaf and hard of hearing poets, mobility disability, sensory disability, developmental or intellectual disability, communications disabilities, limb difference, and so many more, whether lifelong or acquired. We will not ask you to disclose any diagnoses or medical information to participate. We will ask you about your access needs so we can best support your participation.Please make sure you meet all three categories’ criteria for this project and are comfortable with your work appearing in the context of queer, trans, disabled identities. If you would like to use a pseudonym for this project, that’s fine.

How It Works

Poets will be sorted into three groups of six. At your turn, you’ll be sent the poem that came before you and have a week to submit a poem from your own body of work (not written for this publication; unpublished or reprint is fine; it does not have to be a poem you submitted in your questionnaire).

After confirming your poem, you’ll need to write a response statement about your choice — we can support or guide this process in a way that works for you. Once all six poets in your group have submitted, you’ll each see the full chain of poems and responses, and have a discussion about it on the platform that most suits the group’s needs, likely Zoom or Discord. That discussion will be lightly edited for clarity as needed, and you’ll have a chance to check it for accuracy before publication. Poems will be released in the series one by one every two weeks, with their written responses accompanying, and then the group discussion as a separate post after each pod. At the end of the series, we will collect it into an anthology.

What We Want

Queer/trans & disabled poets who are excited to share work with one another!Poets who like to talk/share about their workPoems that aren’t about being queer or trans or disabled; poems that are about itPoems that are joyous and unashamed; poems that struggle in the hard places; and everywhere in betweenPoems that get misunderstood out-group (but your award-winners are welcome here too)Poets from all over the world, including immigrant and diaspora poetsPoets with layers of intersecting identities, including BIPOCOld poets, young poets, unpublished poets, established poets, newly-out poets, community-elder poetsPoets who get excited about poetry :)Editor’s Statement

I am looking for poems that are grounded in a queer disabled perspective — whatever that may be for each poet. That does not mean the poems need to be about queerness and/or disability or even reference them explicitly. I am, in particular, looking for poets who feel the queer disabled perspective is inherent or fundamental to their work, and who are eager to discuss what that means to them, and make connections — and contrasts! — to other poets working from these perspectives. Poets should have some existing awareness of their own queer and disabled identities, whether those have been discussed publicly or not. They should have enough speculative poetry under their belt to allow them to choose response pieces from work they’ve already written (whether published or unpublished).

I especially want the poems written from your bodymind and your being in the way that only you can write, in worlds only you — or perhaps we — could imagine. I want to find out what those poems mean to you, and to us, together.

What we don’t want: almost no topic is off-limits with adequate content warnings, but please, no “AI” generated work, no hate speech/promotion of fascism (n.b., making a dominant group uncomfortable is not hate speech)

Guidelines for Submission (What to Submit)

2–3 poems by queer, disabled poets. These submitted poems are not binding choices; selected poets will choose their poems at their turn in the round-robin structure. Instead, these are intended to give us a sense of your work in general. They can fall anywhere within the broad label of “speculative” (see call) and do not have to explicitly involve queerness, transness, or disability, though they certainly may do so.A short bio (50–100 words)Submit in .doc, .docx or .pdfPlease use 12pt font with each poem beginning on a new page.Please provide content warnings in the document for potentially triggering/traumatic content as applicable.Please use the submission form (below) to submit. Submissions sent via email will not be read.Please answer the following questions (on the submission form)Is there anything about you, including but not limited to specific identities or intersections, that you’d like us to know about when considering your work?What interests you about these particular poems? For example, are there certain details you are proud of, themes that resonate for you, important life experiences you drew from, or questions you wish you could ask your peers about them?When thinking about discussing your work with other queer/trans & disabled poets, what do you yearn for? What excites you?What access needs or other support might you require to participate in this kind of discussion process? For example, live captions, deadline reminders, or prose editing support. It’s fine if these needs change or emerge during the process.At publication, poets will be paid a $50 honorarium.

About UsInterstellar Flight Magazine publishes essays on what’s new in the world of speculative genres. In the words of Ursula K. Le Guin, we need “writers who can see alternatives to how we live now, can see through our fear-stricken society and its obsessive technologies to other ways of being, and even imagine real grounds for hope.” Visit our Patreon to join our fan community on Discord. Follow us on Twitter, Facebook, or Instagram

[image error]Call for Submissions: Infinite Branches: Queer, Speculative Disability Poetry in Conversation was originally published in Interstellar Flight Magazine on Medium, where people are continuing the conversation by highlighting and responding to this story.

October 9, 2024

The Ghost With the Most…D?

“He beetle on my juice till show time” — TikTok, I Shit You Not

“He beetle on my juice till show time” — TikTok, I Shit You NotIn 1988, depressed that Warner Brothers wouldn’t greenlight his Batman project, Tim Burton began working on an even less likely-to-succeed film called Beetlejuice with Larry Wilson, who would go on to write Addams Family and this year’s anticipated hit, Beetlejuice Beetlejuice (2024). Wilson went to a Cure concert and realized that teenage girls loved goth. “It felt to me that there were 50,000 teenage girls in black!” (Film Courage). He then wrote the original Beetlejuice screenplay with teenage girls in mind.

Beetlejuice 1 featured a 17-year-old Winona Ryder one year after her film debut. It launched her career as the Manic Pixie Dream Girl of the late 80s-90s, a new scream queen who starred in iconic goth-girl angsty roles like Edward Scissorhands, Girl Interrupted, Bram Stoker's Dracula, and Alien Resurrection. She was only to be rivaled by Christina Ricci, and together, the two set a new precedent for what girls liked.

Suddenly, goth was cool. It was in. Goth was girlhood.

All of this probably happened because of the energy of these actresses, who captured the existential dread of growing up femme in the 90s in a way that made teenage girls want to be them or be with them. They weren’t Cher in Clueless or, god forbid, Julia Roberts in Pretty Woman. The wave of 90s goth girls was counterculture femininity in a way that hasn’t ever been celebrated, even to this day.

And it represented feminine desire in entirely new ways. In Edward Scissorhands, Winona Ryder’s character cares about the knife-handed, awkward, soft-boi Johnny Depp because he’s different than anything she’s ever encountered. Her boyfriend is a football jock, while Edward is monstrous but sweet, kind even. Across the board, these films, while being counterculture iconography in the way they represent femininity, are also often low on the totem pole in terms of sexuality. The girls represented by 90s goth films are often shown as being uninterested in sex or above it in some way.

The sex didn’t quite matter. For young teenage audiences (like myself at the time), we were drawn to monstrous boys because they were othered like ourselves and somehow less dangerous than the men reality presented. Goth male leads were a dystopian vision of men — in order to be kind, the men had to be broken. Dracula was bound to try and eat you. Edward was sure to cut you up in bed. But at least they were kind.

Romance as a genre works because it manages divides — it creates a conflict without much external plot needed. Something has to keep the characters apart, and in the case of 90s goth films, it was usually that the character was a monster.

In the OG Beetlejuice, the titular “evil” character is represented as a crass, sexist disaster. His desire to wed Lydia is pretty much out of left-field and as a result of his character’s demeaning of women. He’s trying to find a way into the world of the living — for what, we don’t know. His ex-wife is a throw-away joke line as he takes her finger out of his pocket to steal the wedding ring. In many ways, the romantic spark could be seen as between Beetlejuice and Barbara Maitland, not Winona Ryder’s character Lydia.

But even I can admit that I have fallen down the TikTok rabbit hole of Beetlejuice-as-heartthrob memes overtaking social media since the release of the latest Beetlejuice movie.

If you haven’t seen them yet, take a scroll through the app and you’ll see a similar pattern. Clips of Beetlejuice are strung together with a contemporary song, often in amber or sepia tones, the results meant to encourage you to fall even more in love with the character — kink-shaming bedamned.

How Did We Get Here? To, You Know, Beetlejuice Crotch Shots?

How Did We Get Here? To, You Know, Beetlejuice Crotch Shots?As far as remakes go, Beetlejuice Beetlejuice is pretty standard. We meet Lydia Deetz as an adult who now has a talk show, Ghost House. Lydia is hallucinating, thinking she sees Betelgeuse in the audience — a bad omen. Then we learn her father, Charles, has died in an accident while traveling, so Lydia must make the journey back to Winter River, Connecticut, for the funeral, bringing along her estranged daughter Astrid (Jenna Ortega), who very strictly Doesn’t Believe in Ghosts.

The film builds on the lore of the first by casting Lydia in a speculative role. It’s not that she grew up in a haunted house — it’s that she is one of the few people who can actually see ghosts. However, this ability creates a rift between Lydia and her daughter Astrid because Astrid is angry that Lydia can’t see her father, who died when she was younger.

One major difference between the two movies is that now, Lydia is an adult with a kid and a job and a fiance and a dead husband. Ryder does a fantastic job, in her characteristically spotty way, of showing that Lydia is struggling with these average problems. Not only does she have to deal with seeing ghosts every day, but she also can’t seem to connect emotionally with anyone.

When she needs help to save Astrid from the afterlife, who does she call? Of course, Beetlejuice. He represents a fascinating contrast with her fiance, Rory, who is clearly just interested in Lydia for her money and fame. Beetlejuice, on the other hand, has been pining for Lydia since he got banished back to the afterlife in the first film.

The film puts Beetlejuice in the role of protector and helper. He quickly dispatches Astrid’s toxic new crush to hell, forces Rory to admit he’s only after Lydia for her money, and tries to marry her again. But this time, the audience can’t help but appreciate the romantic aspects of the scene, in particular, Lydia and Beetlejuice dancing together as they rise up in the air, reminiscent of the Casper (1995) dance scene.

The film entirely passes over the previously icky concept of Beetlejuice wanting a teenager and instead re-casts Beetlejuice as a potential undead mate. The film ends with a scene where Lydia is still dreaming about Beetlejuice — and their potential spooky Beetle-baby. But it doesn’t feel like a nightmare anymore, does it?

Image Courtesy The Geffen Film Company/Tim Burton Inc.So What Changed?

Image Courtesy The Geffen Film Company/Tim Burton Inc.So What Changed?One thing that might have bridged the gulf between the two movies was the Beetlejuice animated series (1989–1991).

The series follows up on the movie’s popularity by putting Lydia and Beetlejuice on the same level for the first time. In the series, Lydia and Beetlejuice are active partners in their adventures. In many episodes, Lydia becomes the voice of morality for Beetlejuice and the watcher. In Drop Dead Fred fashion, Beetlejuice goes on bad-behavior rampages and has to be reeled back in by Lydia. His animated character may look older than Lydia, but he basically has the mindset of someone who never grew up. In flashbacks, he’s presented as a teenager or a baby, and the series also introduces us to Beetlejuice’s family.

It’s the animated series that first shows Lydia calling Beetlejuice’s name three times to have him save her. By placing the two on the same level, the audience is primed for friendship, if not romance.

Image courtesy Warner Records

Image courtesy Warner RecordsAnother piece of media that may have an impact on the character is Beetlejuice The Musical (2018).

Like the animated series, the musical also features Lydia and Beetlejuice as the two main characters but still follows the plot (somewhat) of the original Beetlejuice. In the musical, Emily Deetz dies and Lydia feels like her father doesn’t see her. This gives Lydia more of a reason for her goth sad girl vibes, using the trope of killing off the mother to give Lydia “issues”, something which wasn’t terribly clear in the original film.

A major difference between the original movie and the musical is that the end scene reveals Juno (the caseworker) as Beetlejuice’s mother. She becomes the defacto villain, and because of his interactions with Lydia, Beetlejuice is able to appreciate the world of the living and defeat his mother with a sandworm.

By the end of the musical, we get the song “Creepy Old Guy”, where Lydia sings about wanting to marry Beetlejuice:

Way back when I was just ten

Simple and sweet

Everywhere, fellas would stare

Out on the street

And I felt used, kinda confused

I would refuse to look in their eyes

But now I really love creepy old guys!

The song pokes fun at the fact that the original movie’s age difference was inappropriate (“Have you guys seen Lolita? This is just like that but fine!”), but it also kind of acknowledges the weirdness of why women are in love with Beetlejuice. Lydia is acting in the scene to trick Beetlejuice, but is she?

It’s these two pieces of media — Beetlejuice the animated series and Beetlejuice the musical — that likely contributed to today’s viewers seeing Beetlejuice as a more sympathetic character than the original movie intended.

Goth Girl Reclaimed

Goth Girl ReclaimedTo go back to the goth girl stereotype, one thing I’ve always loved about Winona Ryder and that thrills me about the Ryder Renaissance is that she GOT the character of Lydia. Being a teenager, she understood that Lydia was a girl who hated the world’s sappy-sweet facade and thus wanted out of it. She played Lydia honestly and with vulnerability. Winona Ryder’s position on the character has been explained in many interviews. She often talks about how she saw Lydia as someone who would never get married — that she would be living alone. But when she met Jenna Ortega — the new goth girl for the 2020s, she began to see a world where Lydia, as a character, had a child. In many ways, it’s not so much about the character becoming a mom but passing the proverbial goth torch.

Oh yeah — and Winona Ryder has admitted in interviews that she always saw Lydia as ending up with Beetlejuice.

“He’s like endgame for me…I totally want them to be truly together.” (Interview with ComicBook.com).

Perhaps the appeal of Beetlejuice IS his crassness, but in Beetlejuice, Beetlejuice, it’s also the actions he takes for Lydia. If he wanted to marry you from beyond the grave, he would. The reality is that the world loves to treat anything teenage girls like as cringe. Sexuality, particularly at puberty, is a strange thing, and I kind of love how TikTok, like its predecessor Tumblr, is a safe space for that.

Of course, I have to give credit where credit is due. Michael Keaton is also a huge part of the enduring sexiness of Beetlejuice. From the moment he put on that leather bodysuit in Batman (1989), he became utterly crushable for not just goth girls but everyone else. Were our brains just mixing the two? Maybe. Whether it’s in full leather bat ears or wormy moldy wigs, Keaton will always be a major heartthrob.

Here’s my advice: If you find yourself crushing on a dead, creepy old guy, just go with it. After all, it’s 2024. TikTok’s got you, bestie.

Interstellar Flight Magazine publishes essays on what’s new in the world of speculative genres. In the words of Ursula K. Le Guin, we need “writers who can see alternatives to how we live now, can see through our fear-stricken society and its obsessive technologies to other ways of being, and even imagine real grounds for hope.” Visit our Patreon to join our fan community on Discord. Follow us on Twitter, Facebook, or Instagram.

[image error]The Ghost With the Most…D? was originally published in Interstellar Flight Magazine on Medium, where people are continuing the conversation by highlighting and responding to this story.

October 2, 2024

Will & Harper Try to Change the World

Images Courtesy Netflix

Images Courtesy NetflixContent Warning: This review contains discussions of anti-trans legislation, misgendering, and anti-trans hate.

The new documentary Will & Harper is a touching exploration of the complexities of what happens in a friendship when one person transitions — and a heartbreaking showcase of how far America has to go when it comes to accepting trans people. Will Ferrell, the popular comedian of SNL (Saturday Night Live) fame, joins his close friend Harper Steele, former SNL head writer from 2004–2008, on a road trip across the United States to rediscover the country and their friendship after Steele’s gender transition.

Making art from the perspective of very personal topics like queer and trans identity can be complicated. Between battling the audience’s expectations and ingrained stereotypes or beliefs, media that engage with so-called “controversial” topics is often under stricter scrutiny, even when the creators and figures at the center of that media are working from a place of personal experience.

Another concern is risk, which is the tense knife edge of anxiety that carries Ferrell and Steele along their road trip through America. The “concept” for the documentary got its start when Harper first transitioned via an email sent to her closest family and friends. Will Ferrell was one of the quickest to respond, accepting Steele’s email with openness, and later, when she expressed a desire to revisit her favorite spots in America, proposing the idea of a documentary road trip.

In today’s often anti-trans America, the concept for the documentary, while presumably giving a reason for “why this format,” somewhat skirts around the fact that for both Ferrell and Steele, it involves significant risk. As the two revisit important places in Steele’s life, from her childhood home to dive bars and an Indiana Pacers game, it quickly becomes clear that while Ferrell had the best of intentions, that risk is always simmering under the surface.

At the aforementioned basketball game, Will Ferrell is introduced to the Governor of Indiana, Eric Holcomb. It’s obvious in the film that this is an unplanned meeting, despite media coverage that implies it was a staged event to promote the documentary. The situation unravels for Ferrell in retrospect as he realizes only after posing for a photo that Holcomb is a Republican who, in April of 2023, signed a ban on gender-affirming health care for minors. “I wish I had the wherewithal to go, ‘What’s your stance on trans people,’” Ferrell says.

This is just one incident documented by the film that shows the disconnect between Ferrell’s role as celebrity and the risk that exposure places on Steele. In Texas, Ferrell and Steele visit a Texas steakhouse, where Ferrell dresses up as Sherlock Holmes for the crowd and attempts to eat a 72-ounce cut of steak. But the room quickly sours as the realization that Steele is trans sweeps the crowd, resulting in a flurry of hateful social media posts. “I was feeling a little like my transness was on display, I guess,” Steele says in the film, “and suddenly that sort of made me feel not great.”

Ferrell begins to cry as he remarks, “I feel like I let you down in that moment, you know? I was like, Oh shit, we gotta worry about Harper’s safety.”

For Will Ferrell, the risk is mitigated by his hyper-celebrity status. Ferrell is a supportive friend who is eager to learn and help. For Steele, the risk is intimately closer to life and body. Steele is a longtime fan of America’s seediest underbelly — and the desire to rediscover those spaces, which are often masculine-coded, is a fascinating one. Watching her juggle the fear of entering a place that might not be safe for a woman, let alone a trans woman who speaks openly about her transition to other patrons, is anxiety-inducing and yet, a testament to her resolve of spirit.

At every turn, Will Ferrell is open and honest, diffusing tension with comedy. He shows that talking openly about transness shows respect for that person’s choice, explaining to each person they meet that they are filming a documentary about Steele’s transition, yet never pressing the point. At one point, he waits in the cold outside a dive bar in Oklahoma for Steele as she enters alone. Inside, she meets a surprising number of friendly people, including a group of indigenous people who sing a traditional song for her.

The film is shot mostly in the car, with beautiful scenes of US landscapes from the Grand Canyon to the Pacific Ocean. This creates a kind of nostalgia that deepens the film’s emotional aspects. In many ways, despite the grim landscape that America represents for trans people, the film is also a love letter to America.

I don’t think the film goes out of its way to place Steele in danger as a form of exploitation. It shows the reality of being trans, from small misgendering at diners to how relationships change or stay the same after a major life shift. Steele is an active participant in the shaping of this narrative, and maybe much of that tension comes from the real stress of experience — of reality.

The casual viewer might ask: Is the risk worth it? And maybe other creators are wondering that too. Can I put myself out there? Where is the line between discomfort and outreach?

Both Ferrell and Steele were in attendance at the Fantastic Fest screening of Will & Harper. Dressed in her signature bright red, Steele was on display again, this time to a much more accepting audience of Texans, most of whom were still wiping away tears as Steele was asked who she hoped the film would reach. She replied that she hoped it reached the Anchorman or Talladega Nights crowd.

It was this reference to Will Ferrell’s early roles that hit home for me. I wasn’t much of a fan of a certain subsect of Ferrell’s bro-y comedies. My favorite Ferrell films are Stranger than Fiction, Elf, Bewitched, and Eurovision Song Contest, to name a few. These softer films, often romantic comedies, get at the heart of Ferrell, a heart which is on display in Will & Harper.

I left the film thinking that if there was one celebrity you could have along with you on the journey through a road-trip-turned-documentary and later Netflix top release, let it be Will Ferrell.

I think what Steele was saying is that it is exactly those men who love Ferrel’s unique form of dude comedy — dick and fart jokes only, please — who really need to see their view of masculinity challenged, who could stand to learn something from Will & Harper. Maybe a way into acceptance is through humor and comedy. Maybe it’s through seeing your favorite celebrity be open and vulnerable about their shortcomings, as well as accepting of their trans friend. Maybe it’s through seeing the honest representation of what it is to be trans in America.

The possibility of creating empathy for trans people is worth the risk, in my opinion, and I hope we see more films willing to deal honestly with the very human side of living life authentically.

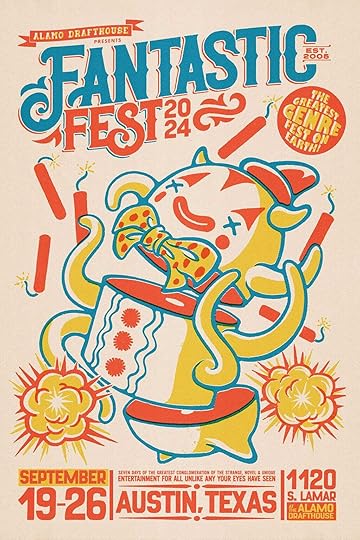

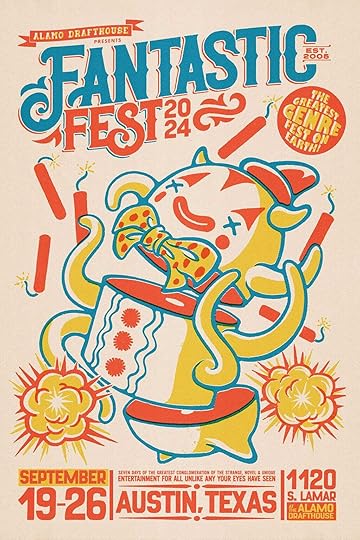

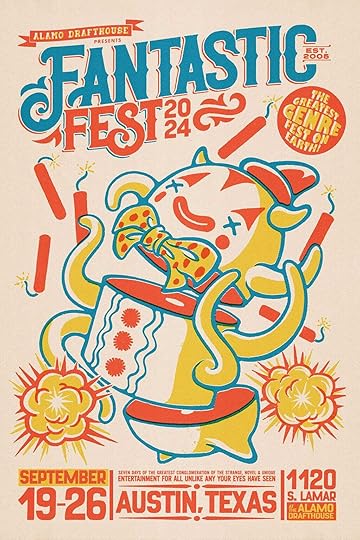

This film is part of our coverage of Fantastic Fest, 2024, taking place September 19–26, 2024 in Austin, Texas.

Interstellar Flight Magazine publishes essays on what’s new in the world of speculative genres. In the words of Ursula K. Le Guin, we need “writers who can see alternatives to how we live now, can see through our fear-stricken society and its obsessive technologies to other ways of being, and even imagine real grounds for hope.” Visit our Patreon to join our fan community on Discord. Follow us on Twitter, Facebook, or Instagram.

[image error]Will & Harper Try to Change the World was originally published in Interstellar Flight Magazine on Medium, where people are continuing the conversation by highlighting and responding to this story.

September 22, 2024

TRIZOMBIE: Down Syndrome in the Apocalypse

Director Bob Colaers has created a conversation piece in the new Belgian film TRIZOMBIE (2024), premiering at Fantastic Fest this week in Austin, Texas. The film follows a group of people with Down Syndrome as they survive a zombie apocalypse where only people with trisomy 21, an extra twenty-first chromosome, are immune to the virus.

The film was originally a TV miniseries and has been cut together into a film with surprising success: It never feels as if you are watching a shortened version of a TV show. The story follows Luka (Jelle Palmaerts), Kelly (Gitte Wens), and George, aka The Slasher (Jason Van Laere), as they battle zombies to save Robin (Tineke Van Haute), who has recently left the care center to live in assisted living (essentially, independent living).

Robin is a huge fan of invented-for-the-film popstar Will Murray, who sings catchy pop Oktoberfest rhymes in the genre of “Schlager” songs. (The soundtrack is available on Spotify.) After saving Robin, the crew decides to head out to the singer’s theme park as a safe haven.

With excellent humor and a hilarious soundtrack, Trizombie hits all of the expected zombie tropes. I was struck by how the film pairs these obstacles as a metaphor for the obstacles people with Down Syndrome face when learning to live on their own. For example, the characters have to learn to get out of the care center safely by bypassing the security gate. They learn to drive a car, figure out that one should probably lock the front door, and seek out shelter and food. These are all things that can be tricky for people with mental disabilities, let alone in a disaster where survival is key.

Survival is not a given for people with Down Syndrome. In Belgium, where the film was made, 94% of doctors support after-birth abortion for children with disabilities. The rate of pregnancies terminated for Down Syndrome is around 90% there. Down Syndrome babies often have other health conditions, including congenital heart disease, conditions of the eye like cataracts, hearing loss, and hypothyroidism, to name a few (NIH).

Despite these facts, the film doesn’t sugar-coat the experiences of its characters, nor does it expect them to be perfect. It allows the characters to fail, to make mistakes, to curse, and to be flippant. Zombie films are not cutesy, and this film, while being heart-warming, is no different. Diehard zombie film fans will find a lot to enjoy here.

The performances in TRIZOMBIE are a lot of fun to watch. I particularly enjoyed Jason Van Laere, who plays the tropey, macho-machismo sledgehammer-wielding Slasher, who reminds me of a mix between Shaun of the Dead and Rambo. The cast is part of the Turnhout-based Theater Stap, a theatre company that serves the disabled community and that does not shy away from putting its actors in sometimes controversial productions. According to its website, the goal is “putting first the actors’ authenticity, increasing the visibility of disabled people and livening up broad discussions about theatre.”

All these positives aside, I wonder about the film’s premise. Does it fall into the “mystical disability” trope, where characters with disabilities are often magical plot devices? The characters here are “safe” because of their disability, inherently making them special. The film would, in my opinion, be just as successful without this status. Audiences would still be interested in seeing how people with a disability survive a zombie apocalypse. Does it diminish the stakes of the film if we know the characters can’t be killed? I, for one, think it would be cool to see zombies with disabilities — but perhaps the filmmakers thought it would be a step too far.

Nevertheless, Trizombie brings disability representation to a wider, zombie-loving audience, and that makes it worth a watch and worth talking about.

This film is part of our coverage of Fantastic Fest, 2024, taking place September 19–26, 2024 in Austin, Texas.

Interstellar Flight Magazine publishes essays on what’s new in the world of speculative genres. In the words of Ursula K. Le Guin, we need “writers who can see alternatives to how we live now, can see through our fear-stricken society and its obsessive technologies to other ways of being, and even imagine real grounds for hope.” Visit our Patreon to join our fan community on Discord. Follow us on Twitter, Facebook, or Instagram.

[image error]TRIZOMBIE: Down Syndrome in the Apocalypse was originally published in Interstellar Flight Magazine on Medium, where people are continuing the conversation by highlighting and responding to this story.

September 21, 2024

Bring Them Down Review

In Fantastic Fest 2024 feature BRING THEM DOWN, Christopher Abbott plays Michael (Mikey) might-as-well-call-him-Danny-boy, a shepherd with a dark past forced into violence in this gripping domestic thriller. The film opens with one of the most heart-wrenching introductions to a character I’ve ever seen, taking the popular horror movie trope of opening a film with a car accident (Get Out, Final Destination, The Descent, etc., etc., etc.) and turning it on its head. Barry Keoghan is an Irish teenager with a chip on his shoulder. Colm Meaney (Star Trek’s Chief O’Brien) is a disabled father who speaks only in Gaelic out of stubbornness, rounding out this cast of talented male actors in a film on the perils of toxic masculinity.

Michael is a shepherd in rural Ireland who is down on his luck after an accident results in the death of his mother and injury to his girlfriend, Caroline (Nora-Jane Noone). What he hasn’t told his bearish father is that his mother meant to leave his father. When a feud breaks out between neighboring sheep farmers, the wife of which is his former girlfriend, Michael is forced to take matters into his own, somewhat unhinged hands.

Christopher Abbott is fantastically riveting as what the director calls a “stoic, mythical character” (The Wrap) despite not being Irish. While the role would be somewhat more convincing with an Irish actor, Abbott’s performance is convincing and, for me, reminiscent of Ryan Gosling’s darker roles. The audience yearns for Mikey to act out his revenge after the death of his flock of sheep.

Meanwhile, Barry Keoghan is satisfyingly annoying and yet timelessly soft as Jack, the son of Caroline. Halfway through the film, we flip to his point of view, and the empathy he brings to the character is nuanced and delightful.

One of my favorite storytelling structures, and one particularly effective in horror, is the “slippery slope” — where a situation is played out to its absolute worst and inevitable end. BRING THEM DOWN does just that, answering the question of what happens when you push a man to his breaking point, and an Irish man at that.

Loosely based on a true story, the film is rife with animal violence. It calls to mind the parable of the good shepherd, where Jesus likens his role as a savior to the shepherd: The good shepherd is willing to die for his sheep. But for those who can’t endure animal violence, this film should have a trigger warning. Be warned. Several traumatic scenes of animal death are almost too difficult to watch.

Against this violence, the cinematography, writing, and aesthetic from debut director Christopher Andrews are spot-on, showcasing the dark closeness of the Irish countryside painted in swaths of misty greens and blues — which serve as a beautiful contrast for the touches of blood as the film descends into a dark look at the human soul. Resentment, miscommunication, and domestic abuse drape the story in emotion.

The theme here is toxic masculinity. Who it hurts, who it kills, and who it destroys. The stereotypes of Irish masculinity — alcoholism, domestic violence, and closed-off emotions, are explored with empathy. As always, as inevitable as it is, toxic masculinity hurts men as much as it does women.

It is a difficult but nuanced film that will capture the audience’s hearts. Far from funny and a gripping watch. Let’s hope this gets wider distribution, STAT.

[image error]Bring Them Down Review was originally published in Interstellar Flight Magazine on Medium, where people are continuing the conversation by highlighting and responding to this story.

September 20, 2024

The Rule of Jenny Pen

“Life is precarious, happiness is fragile, triumph and disaster are only a random incident apart.” — Owen MarshallReal-life Horror Often Overlooked

It may seem slightly out of character for IFP to review a film about old men in a care home, but stick with me. In its world premiere at Fantastic Fest, THE RULE OF JENNY PEN is a psychological thriller that follows Stefan Mortensen (Geoffrey Rush), a respected judge who begins a new life in a residential care center when he has a stroke. There, he meets what seems to be an oddball group of elderly residents, each with their own strange quirks. The strangest of all is Dave Crealy, who, as one resident remarks, is one of those who has been given a doll (in this case, a terrifyingly eyeless puppet named Jenny Pen) as a comfort, like a child.

With exacting empathy, the film showcases the loss of humanity — both psychologically and physically — that often occurs when people are cared for by the thinnest margins. Set in New Zealand, the film fictionalizes what is a real-life horror for those shunted into under-resourced aged care centers, where oversight is small and accidents are ignored. We forget that the aged are often one of the largest populations of marginalized people today, and Indigenous elderly are often at the highest risk for abuse. Like many countries, New Zealand struggles to care for its aged, who make up 20% of its population. 38% of people over 65 die in care centers, and the situation has been called a human rights crisis, with several high-profile incidents gaining national attention. The film is set during the height of the COVID-19 pandemic, which feels like a fitting choice given how many people in aged care were particularly at risk.

As someone who has watched a loved one go through the stress of entering a nursing facility, I was struck by how carefully the film addresses the specific horrors that can occur. Horror is uniquely situated to comment on the realities of our world with empathy. The film does a fantastic job exploring the terror of dementia and illness: Loss of bodily autonomy, memory gaps, and, most importantly, the infantilization and disbelief people who cannot control their bodies often face. It quickly becomes clear that the residents are not strange because they are strange — they are doing everything they can to survive.

In the case of THE RULE OF JENNY PEN, this horror is exacerbated as the puppet-handed Crealy terrorizes the residents. Lithgow’s performance here is delightfully creepy, heightened by the interjection of surrealist elements. At times, the doll becomes larger than life, looming in the background, forcing the audience to look into her eyeless sockets and fall under her judging gaze.

This sounds quite bleak, but the film does a good job of pairing humor with pain while still not making fun of the characters. It is Māori actor George Henare who steals the show as Garfield, Mortensen’s friend and roommate. A former football player, he has, in his mind, lost his honor by submitting to Crealy’s abuse. The absolute best scene of the film shows Garfield attempting to perform the Haka, a traditional war dance, but struggling as his voice and body fail him.

Based on a Short StoryTHE RULE OF JENNY PEN is based on a short story by New Zealand author Owen Marshall, who also worked with director James Ashcroft on Coming Home in the Dark (Light in the Dark Productions, 2021). In Marshall’s story, Crealy is the main point of view character, telling the story in his voice versus in the voice of Stefan Mortensen. The film follows the story faithfully, the only exception being that it gives Crealy a sketched backstory that verges on surrealism.

The best horror looks terror in its face and does not judge it; it merely provides an awareness of it. THE RULE OF JENNY PEN, which does have a scene of sexual assault, is not for everyone. However, it is worth a watch for its stellar performances and fascinating cinematography. The film will be streaming on SHUDDER soon.

This film is part of our coverage of Fantastic Fest, 2024, taking place September 19–26, 2024 in Austin, Texas.

Interstellar Flight Magazine publishes essays on what’s new in the world of speculative genres. In the words of Ursula K. Le Guin, we need “writers who can see alternatives to how we live now, can see through our fear-stricken society and its obsessive technologies to other ways of being, and even imagine real grounds for hope.” Visit our Patreon to join our fan community on Discord. Follow us on Twitter, Facebook, or Instagram.

[image error]The Rule of Jenny Pen was originally published in Interstellar Flight Magazine on Medium, where people are continuing the conversation by highlighting and responding to this story.

September 11, 2024

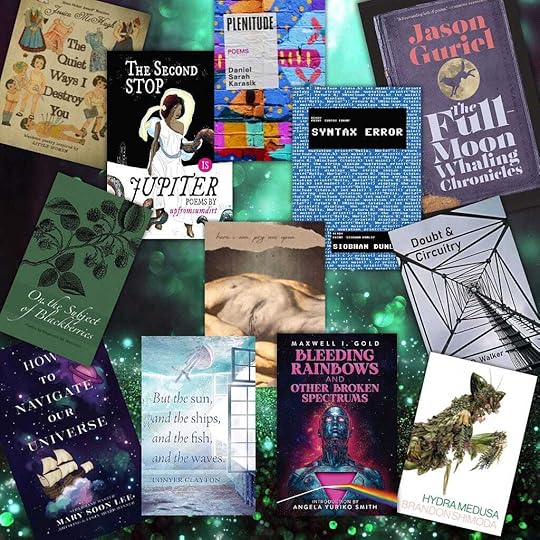

The Best Speculative Poetry is Intersectional

This is my sixth year reviewing books from the SFPA (Science Fiction and Fantasy Poetry Association) Elgin Award for best speculative poetry book. A full list of nominated books is available on the SFPA website. This year’s award chair is Felicia Martínez, who I would like to thank for diligently tracking nominations.

Here are my previous reviews:

The Best Speculative Poetry of the Year is ExplosiveThe Best Speculative Poetry of the Year is EpicThe Best Speculative Poetry is Creepy AFThe Best Speculative Poetry Engages in Experimental FormsSpeculative Poets Renegotiate Femininity & the StrangeAbout the Awards: The Elgin Awards, named for SFPA founder Suzette Haden Elgin, are presented annually by SFPA for books published in the preceding two years in two categories, Chapbook and Book. Chapbooks must contain 10–39 pages of poetry and books must contain 40 or more pages of poetry. E-books are eligible, as well as print. Books that won first–third place in the previous year’s Elgin Awards are ineligible. Single-author and collaborative books are eligible; anthologies are not. Books containing fiction as well as poetry are not eligible. Books must be in English, but translations are eligible. In the case of translations that also contain the poems in the original language, those pages will not count toward the total page count. Nominated books must be made available to the Chair upon request to remain eligible.

Thoughts on This Year’s BooksI am reminded how fragile this genre is by the smallness of this year’s list. Each year, I focus my reading for the year on speculative poetry because it is a genre I love and write myself — and 2024 was a year where I struggled to find books that fit the genre. It’s not just that the pandemic decimated many small presses — but I think it’s just that the writers who are publishing are juggernauts. Whatever the reason, I continue to hope to see more speculative poetry, and I remain dedicated to celebrating the genre.

Each year that I review the SFPA Elgin Award nominated books, I find myself bemoaning the resources of small presses. There are so many books on this list from small presses that could benefit from more reader support to increase the distribution and circulation of these fine titles. Speculative poetry is already the red-headed stepchild of SFF: It is only in 2025 that a major science fiction and fantasy award is recognizing poetry (the Hugo Award — and we do not yet know if its new poetry category will be permanent to the subsequent awards). As a new member of SFWA (Science Fiction Writers of America), I joined with the sole intent of becoming a part of the poetry movement, and as a co-chair on the SFWA poetry committee, our first goal was to create a poetry Nebula Award. I have some small hope, therefore, that poetry will soon become a recognized genre of speculative writing.

While the SFPA is full of talented and kind writers, as well as dedicated volunteers, as an organization, its reach is limited. Poetry itself is often seen as second-class to more popular genres of fiction or memoir. The reality is that speculative poetry is a thriving and important genre, and I for one remain committed to supporting the many fabulous books published each year that receive so little well-deserved acclaim.

I enjoyed all of the books from newer press Kith Books, which has many titles on this year’s nominee list. Everything from there is worth reading!

One thing that strikes me about this year’s books is how intersectional they are — not just feminist, but chronically ill; not just black but queer; not just speculative, but a kaleidoscope of ideas, identities, and themes. Speculative poetry truly has upped its game.

How I Create This ListHow do I pick books for this list? This is merely a recommended reading list, not a “best of” list because the list I am pulling from is the nominated works from the SFPA membership. My primary concern is highlighting works I feel deserve more reads. I tend to skew heavily feminist, focusing on writers of color, LGBTQIA+ voices, and disabled poets. The list is subjective to my tastes. I spend less time on men (cis-gendered, heterosexual) because those voices have enough support. I always make a Goodreads list of the total nominated works, which you can access here.

Lastly, in the past, there has been some (IMHO short-sighted) discussion as to whether such lists are “bad” because they skew members’ voting towards one work or the other. I find this difficult to believe because I review a huge number of books selected for the Elgin. I also believe the SFPA membership has enough independent thought to be able to do their own voting. The list is not to highlight those works I think you should vote for but to highlight the amazing works nominated each year and lift up the endeavor as a whole. Vote as you see fit.

One more note: I am writing from my perspective. If I make an error, please comment or message me. I never want to misrepresent a work simply because I misread it. Also, this list contains works I wrote or edited. I feel poets should be vocal about promoting their work, but if this bothers you, you can scroll on past.

A frustratingly necessary note for 2024: I don’t review books that use LLMs/AI in the art or text, nor do I support authors who support those programs. It has become increasingly clear that the companies who run those softwares have massively infringed on the copyrights of artists, authors, and creatives. While I believe poetry can explore the juxtaposition between technology and art, and I would be interested to see an author actually subvert the outright theft and blatant disregard for creative capital these programs and their owners exploit for mass profit, I have yet to see that happen.

Chapbooks Angels & Insects Are Creatures with Wings (Kith Books 2023)

Angels & Insects Are Creatures with Wings (Kith Books 2023)by Amy Jannotti

The reader’s first encounter with Jannotti’s style comes in the formatting of the Table of Contents, which separates the book into two sections: “Vermin” and “Divine” — with an introductory poem before both “A Common Ancestor, Clipped”. Here, the book’s main focus on the dichotomy between what is beautiful/holy and what is ugly/horrific is established. Forms vary from prose poems to free verse couplets, while the content itself is primarily body horror with a personal, confessional point of view. The speaker is female, presumed weak, broken — entirely focused on survival, which is, after all, the primary mechanism by which femininity exists, particularly in horror as a genre. From terrariums to knives, Jannotti’s raw lyricism and fresh turns of phrase make this little, sharp book a worthwhile read.

Beautiful Malady (Interstellar Flight Press, 2023)

Beautiful Malady (Interstellar Flight Press, 2023)Ennis Rook Bashe’s collection of cripspec poems merges the dream world with the harsh realities of living in a broken body. At once heartbreaking and curative, Bashe’s work explores disability and chronic illness in ways not yet celebrated in speculative poetry. Bashe pulls no punches: Living in the disabled/chronically ill body is not a fairy tale. But these poems still give us hope as readers — through the beauty of the fantastic. Read Julie Reeser’s interview with Ennis Rook Bashe. Listen to Ennis read from Beautiful Malady.

Dionysia (Verve Poetry, 2023)

Dionysia (Verve Poetry, 2023)by Kim Deyn

Queer poet Kim Deyn’s cheeky retellings of male historical figures (Alexander the Great and Odysseus) join the pantheon of queer reimaginings of Greece and beyond in recent publications (See: Enkidu Is Dead and Not Dead / Enkidu está muerto y no lo está: An Origin Myth of Grief by Tucker Lieberman and anOther Mythology by Maxwell I. Gold). Despite my desire to see more Greek/Roman myths and histories told by people native to those places, centering queerness in relationship to those stories feels like a necessary conversation in today’s context.

The book is split into two parts: “Alexandros, or, the first play,” which focuses on Alexander the Great — and “Night Interludes, the second play,” which explores Odysseus. Deyn draws on their playwriting experience to format the book in a found form of a stage drama. The flippant framing of characters is delightfully camp — Alexander is “prettyboy, wine-drunk, divine.” Despite focusing on male figures, the work is still feminist in its inclusion of female historical figures: “I put the sister in this because I want the impossible because grief makes madwomen of us because once she arrived she wouldn’t leave and swims in this poem like a goldfish in a bowl”. This is a richly dense book that belies its length.

Magic Lives in Girls (Kith Books, 2023)

Magic Lives in Girls (Kith Books, 2023)by Sadee Bee

“Womanhood a construct / Femininity, a choice and a curse /”

Queer Poet and Illustrator Sadee Bee’s chapbook falls into what Arielle Greenberg termed the “Gurlesque”: “The words of the gurlesque luxuriate: they roll around in the sensual while avoiding the sharpness of overt messages, preferring the curve of sly mockery to theory or revelation‟. It’s no wonder the main inspiration was Florence + The Machine. Bee strings together the memories of a speaker who is drawn to graveyards in a dark exploration of self that ruminates on the loss of innocence brought about by the trauma of growing up female. What might be overwrought metaphors like the moon for femininity in the hands of a lesser poet are reclaimed in dense prose and free verse poems that emphasize discomfort in long lines punctuated by brokenness. (Will someone please write a book on the contemporary poem’s use of the slash already?) Sadee Bee embraces the magic of girlhood through a dark lens.

“I have learned there is beauty in the brokenness. I am my own Sun, my own / Moon, a wondrous solar system within myself. I am the universe born anew, my / own evolution; a forceful shift in orbit since leaving the womb.”

Numinous Stones (Aqueduct Press, 2023)

Numinous Stones (Aqueduct Press, 2023)I’m delighted that the SFPA membership chose my chapbook, Numinous Stones, for inclusion on the Elgin nominee list. Written entirely in pantoum form, this book was a grief outlet for me after the death of my father. It was also nominated for a Bram Stoker Award this year. Here is the book’s description:

From Elgin Award winning author Holly Lyn Walrath, a haunting collection of poetry about grief and the sacred that digs deep beyond a fairytale world into the grave. Told in the circular pantoum form, Numinous Stones is a poetic graveyard littered with horror — from sentient scarecrows to silent skeletons to scorched sacred spaces. As each line repeats, new meaning gleams like bones unearthed in a shattered realm of monsters, dark forests, and dusty ghosts.

The Worm Sonnets (Quarter Press, 2023)

The Worm Sonnets (Quarter Press, 2023)Modern-day speculative naturalist Amelia Gorman brings her love of all things weird to the humble worm: A subject she first focused on in her debut chapbook and previous winner of the 2022 Elgin Award, Field Guide to Invasive Species of Minnesota (Interstellar Flight Press, 2021.) The Worm Sonnets also calls to mind the field guide with its richly illustrated pages. But the visual images are only surface dressing on a delightful array of ghosty, wormy poems exploring the strange denizens of Worm World. Gorman’s poetry is an excellent example of contemporary ecopoetry — intersectional in placing the quintessential ghost girl at the center of that genre. While I’m not generally a lover of rhymed poems, Gorman’s sonnets are subtle enough that the form works well, and each poem is satisfyingly well-turned. It’s a shame this book is not available in wider distribution. Read Julie Reeser’s interview with Amelia Gorman.

Books A Wheel of Ravens (Jackanapes Press, 2023)

A Wheel of Ravens (Jackanapes Press, 2023)by Adam Bolivar

As an Engish Major, I feel I would be remiss if I didn’t mention this absolutely bonkers and complex collection of alliterative verse (think Beowulf). Dennis Wilson Wise, PhD at the University of Arizona, provides a valuable foreword to what is likely to be a challenging read for most readers unfamiliar with Old English tales. That being said, I’ve always found this style to be one of the most accessible forms of ancient poetry. I still advocate for readers new to the works of Anglo-Saxon England to try Beowulf, as it remains surprisingly readable, and there are a number of famous translations (Tolkien, Seamus Heaney, and, in 2020, Maria Dahvana Headley, to name a few). However, Bolivar’s work stands out as it is both an entirely new collection of invented alliterative poems and unique as it is short poetry (a series of individual poems) vs. an epic poem.

Bolivar makes meticulous use of the alliterative form, and its constraints; most interesting to modern readers is likely the caesura, a break in each line that may feel familiar to experimental poetry in its use of white space. The content of the poems is satisfyingly weird — merging themes from Weird Poetry as a genre (primarily Lovecraftian in imagery) with familiar mythological tropes like witches, vampires, and dragons. These are not contemporary poems. Instead, Bolivar seems to have channeled the bards of old to give voice to an entirely new imagining wrapped in old verse, which is a feat to be celebrated.

anOther Mythology (Interstellar Flight Press, 2023)

anOther Mythology (Interstellar Flight Press, 2023)Gold’s weird retellings of world myths explore the ancient stories through a queer perspective. Gold has a talent for the prose poetry form, which is often underutilized in speculative poetry but makes for a fantastic form of narrative sequence. Poems like “Drag, Queen of the Underworld” and “The Myth of the Closet” pair camp sensibilities with Weird Fiction tropes, subtly subverting the sometimes-problematic past of cosmic horror. If you love mythology and are looking for queer retellings, this collection is for you. In comparison to Gold’s other book on this list, this chapbook is a somewhat lighter foray into the strange queer landscape of the mythic. Listen to Maxwell I. Gold read from anOther Mythology. Read an interview with Maxwell I. Gold at Interstellar Flight Magazine.

Bleeding Rainbows and Other Broken Spectrums (Hex Publishers, 2023)

Bleeding Rainbows and Other Broken Spectrums (Hex Publishers, 2023)It is rare to see an author with three books nominated on the SFPA Elgin Award list (it would be fascinating to do a study of the number of authors who have received this honor), but Gold’s book of erotic cosmic verse is a worthwhile addition. Primarily prose poems and free verse with use of white space, Gold’s book dives into a world of “Monsters, Jock-Queens, and Rainbow Gods”. The poems are paired with fantastic illustrations by artist Martini, primarily a comic artist, who here invokes the imagery of comic artist Dave Gibbon’s Doctor Manhattan from Watchmen (1986–1987) — a giant, nude blue man floating in space. I would argue that it is also rare to see such a complexly erotic book recognized by the SFF community. Gold dives into the dark side of queer sexuality, exploring the power dynamics of love and lust. I particularly enjoyed the collection’s sense of narrative arc, like a mythical journey the speaker embodies through pain to triumph. This is, at times, challenging material (at least for readers outside of the queer community) but deftly handled by a skillful poet.

But the sun, and the ships, and the fish, and the waves (Anvil Press, 2022)

But the sun, and the ships, and the fish, and the waves (Anvil Press, 2022)French poet André Breton, founder of the surrealist movement, defines the genre as: “Pure psychic automatism [unconsciousness] by which we propose to express — either verbally or in writing or in some other manner — the true functioning of thought. The dictation of thought, in the absence of all control exercised by reason, outside all aesthetic and moral preoccupations… Surrealism rests on a belief in the superior reality of certain forms of association neglected until now, in the omnipotence of dream, in the disinterested play of thought.”

Which is to say, the best surrealist poetry relies on unconscious connections — a strangeness that comes from the juxtaposition of unexpected elements that the subconscious stitches together. A fantastic example of this in poetry is found in Conyer Clayton’s poem “Self-Made,” which starts with a woman finding a beetle in her hair and seeing a doctor who reels in a TV that is playing a Wild West scene where a horse eventually explodes into beetles. These images feel random, but put together, they form a sense for the reader of the utter strangeness of navigating the healthcare system as a woman.

Clayton’s book, primarily composed of prose poetry, is a beautiful example of contemporary surrealist poetry, blending dream with startling image and subconscious metaphors. Two sisters form the heart of the book’s narrative as they navigate life through a strange landscape of insects, ghosts, pollution, vampires, sinister men, and demons.

Doubt & Circuitry (Southern Arizona Press, 2023)

Doubt & Circuitry (Southern Arizona Press, 2023)By T.D. Walker

T.D. Walker is a shortwave radio enthusiast, and her obsessions are showing in this collection of pandemic-rooted abstract poems. Walker combines the history of the US Emergency Broadcast System, Cherynobl, and the 2020 pandemic into poems that ask the hard questions of what it means for a people to be at the whim of their government and politics. In the author’s note, she says, “‘Chernobyl 1986 / COVID 2021’ began as a question: how did the disasters of the 2020s shape my children’s view of the world, particularly in light of their disconnect from the world? And my own? How would they begin to function within the world again?”

We are still grappling with these questions in a world where we are told the pandemic is over, but COVID is still a daily part of our lives. Walker takes us back in time to a place where nuclear war was an imminent threat — using the radio as a tuner to the past. Near rhymes give the collection an eerie tone, as well as the surreal images of birds, plants, viruses, decay, and magma — juxtaposing nature (and its impacts from humans) with scientific research. A fascinating, meticulously crafted read.

Here I am, Pry Me Open (Kith Books, 2023)

Here I am, Pry Me Open (Kith Books, 2023)St. Cloud’s punk-rock-trans-angst-fest treat opens with a quote from the band Against Me! an early 2000s American punk band led by singer and guitarist Laura Jane Grace, who came out as a trans woman in 2012: “C’mon, shapeshift with me, what have you got to lose?” It’s giving Hedwig and the Angry Inch for a new era.

The book opens“Before the Incision” and focuses on childhood, beginning with the speaker at age 12–24 in “Notes to a 12 Year Old Optimist,” which deals with the trauma of body dysphoria during puberty and the subsequent teenage years. St. Cloud explores themes of growing up religious, childhood games, dolls, and aliens through the lens of transness. These poems sizzle, particularly in their fairly snarky titles (“An Alien Went Through Me & All I Got Was This Stupid Reality”, “Local Fairy Forgets Common Colloquialism — Word Stew Follows”, “Are You Not Entertained”, “Taco Hell Condemns Thee”,” “Therapist That” to name just a few delightful examples), but also in the raw, nervy, punk rock honesty that drives the speaker on and on. This is a must-read for us awkward emo kids who grew up hating our bodies and ended up living life like a primal scream.

If you believe queerness and otherness are inherently strange, this book is for you. To me, this book could be read as a foray into the new speculative memoir genre of poetry, and I, for one, am Here For It.

How to Navigate Our Universe (Self-Published, 2023)

How to Navigate Our Universe (Self-Published, 2023)Every time I see Lee’s name on an award list, I just know everyone else is doomed. Mary Soon Lee’s self-published poetry collection is entirely made up of “How To” poems, with the exception of “Part V Space Dust”, which has 15 poems of varying titles. “Part I Our Backyard: The Solar System” journeys through our solar system with planet by planet personified in haiku and short poems that touch on the tropes of those celestial bodies. These are science poems (See Mary Soon Lee’s excellent previous collection Elemental Haiku: Poems to honor the periodic table, three lines at a time, Ten Speed Press, 2019), but they are at once accessible and heartbreaking. “How to Thank Earth” stands out as a beautiful ode to our home planet: “When you are grown, / when you leave for the stars, / write home.” Lee is excellent at staying on theme and a devastatingly prolific poet of our generation. I’m not sure what it is that makes these poems so good, whether it’s their simplicity or their beauty, but I wish they bottled it so I could have it for breakfast every day, preferably somewhere on a distant planet, far from the troubles of This One.

Hydra Medusa (Nightboat Books, 2023)

Hydra Medusa (Nightboat Books, 2023)Brandon Shimoda’s hybrid collection will have you asking: “Is it poetry?” in the best way possible. Primarily made up of untitled poems (here using the convention of brackets and ellipses to indicate there is no title), Shimoda’s poems follow no particular form or structure, moving forward organically with white space on the page or dense passages of prose poetry. “The Descendant” could be a hybrid creative nonfiction piece about Japanese American Incarceration, but it carries none of the sensibilities of a traditional essay and instead moves and breathes on the page like a poem.

In an interview with Nightboat Books, Shimoda says about this hybridity:

“Hybridity, for me, is, less about form, more about emotions and the process of learning…The learning and the questions have, since then, not stopped. But it has not been linear. It has been messy, mercurial, amnesiac, repetitive, disjunctive, seismic, lonely. And yet it has taken me to many places, introduced me to many people, many of whom have become friends, important people in my life. But it has been chaotic. In other words, hybrid. And because writing has been central to that process, the writing has also been hybrid.”