Jay L. Wile's Blog, page 35

December 15, 2016

Evolutionists Couldn’t Have Been More Wrong About Antibiotic Resistance

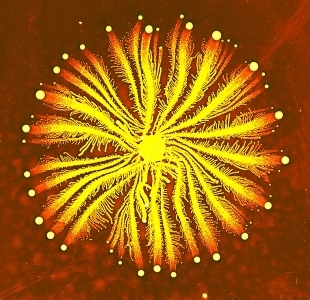

A colony of bacteria similar to the one analyzed in the study being discussed. (click for credit)

Back when I went to university, I was taught (as definitive fact) that bacteria evolved resistance to antibiotics as a result of the production of antibiotics. This was, of course, undeniable evidence for the fact that new genes can arise through a process of mutation and natural selection. Like most evolution-inspired ideas, however, the more we learned about antibiotic resistance in bacteria, the more we learned that there was a problem. It turns out that some cases of antibiotic resistance in bacteria were not caused by antibiotic-resistant genes. Instead, they were caused by the deterioration of genes that exist for other purposes. For example, the Anthrax bacterium can develop resistance to a class of antibiotics called quinolones, but it is the result of a mutation that degrades the gene that produces gyrase, the enzyme that those antibiotics attack. This allows the bacterium to survive the antibiotic, but the degraded gyrase gene causes the bacterium to reproduce much more slowly.There are, however, specific genes found in bacteria that do produce proteins which fight antibiotics. It was generally thought that these genes arose through mutation and natural selection in response to our development of antibiotics. However, we now know that this just isn’t true. Antibiotic-resistant genes existed long before people developed antibiotics. I first wrote about this more than five years ago, when researchers found bacterial, antibiotic-resistant genes in permafrost alongside mammoth genes. Obviously, people weren’t making antibiotics when mammoths were alive. Thus, those genes existed long before human-made antibiotics. Later, I wrote about researchers who found bacterial, antibiotic-resistant genes in fossilized feces from the Middle Ages. Once again, this shows that antibiotic-resistant genes have been around long before our development of antibiotics.

Now an even more impressive study has been released. In it, researchers analyzed the DNA of a bacterium from the genus Paenibacillus. These bacteria form colonies, such as the one shown in the image above. The colors in the image indicate the density of bacteria – the brighter the yellow color, the higher the density of bacteria. While this genus of bacteria has been found in many, many environments, the specific species analyzed in the study was special: it has been living in a cave that has been isolated from the modern world. In fact, the cave is so isolated that no animals had ever ventured into it. When the researchers analyzed the DNA of this bacterium, they found all sorts of antibiotic-resistant genes.

In fact, they found that this bacterium was already resistant to most modern antibiotics, and they get this resistance from the same genes as pathogenic bacteria that have already been studied. In other words, the resistance to these antibiotics isn’t anything new. It didn’t come about as a result of the production of antibiotics. It has been in bacteria all along. The only thing antibiotics did was expose the fact that such genes already existed.

Now if this was the only conclusion in the paper, I probably wouldn’t have written about it. After all, we already know that the evolution-inspired explanation for antibiotic resistance isn’t correct. We know that bacteria possessed antibiotic-resistant genes long before the development of antibiotics, and when “new” antibiotic resistance arises, it is from mutations that deteriorate genes which already exist.

However, the thorough analysis done by the authors of this paper showed something else: potential antibiotic-resistant genes that had not yet been identified! In this bacterium, which had never been exposed to antibiotics, the researchers actually found five new families of genes that could potentially be used by bacteria to fight antibiotics! They say that these families of genes are widespread in the environment and can have clinical significance if they end up being transported into pathogenic bacteria. In other words, there are “stockpiles” of antibiotic resistant genes residing in bacteria that are not disease-causing. Since we know bacteria are adept at gaining genes from other bacteria, these stockpiles will probably find their way into disease-causing bacteria, producing even more antibiotic resistance.

Far from being evidence for flagellate-to-philosopher evolution, then, antibiotic resistance is evidence against it! After all, it shows that from a genetic point of view, there is nothing new being developed. There are only antibiotic-resistant genes that existed long before antibiotics, and there are mutations that degrade genes which also have existed long before antibiotics. This is precisely what you would expect in a creationist framework.

December 13, 2016

Confirmation of Feathers On A Dinosaur?

Image of a remarkable feathered fossil preserved in Amber. (from the paper being discussed)

At university, I was taught (as definitive fact) that the scales on reptiles slowly evolved into feathers. While you can still find this idea in popular literature, serious evolutionists no longer suggest it, because there is simply too much evidence to the contrary. Most evolutionists today suggest that feathers, scales, and hair all evolved from a common ancestral structure. I am sure that if serious scientists are still discussing flagellate-to-philosopher evolution in 50 years, there will be yet another idea of how these structures evolved.Because evolutionists no longer think that feathers evolved from scales, the currently-fashionable thing to teach as definitive fact is that at least some (if not all) dinosaurs had feathers. The problem is that solid evidence to back up this “fact” has been sorely lacking. There are some dinosaur fossils that give hints of feathers, but there are alternate interpretations of what those hints mean. There are other fossils that clearly show feathers, but it’s not clear the fossils are of dinosaurs.

Now all that has changed, at least according to some sources, because of a recently-reported fossil. The remarkable specimen (pictured above) is part of a tail that has been encased in amber. The amber has preserved both the bones in the tail and the feathers that covered it, giving paleontologists a superb sample to analyze. While the results of the analysis are not conclusive, I do think that they add to the case that at least some dinosaurs had feathers.

The paper reporting the analysis is open-access, so you can read it if you can sort through all the jargon. If nothing else, you can see the excellent pictures of the specimen. Essentially, the fossil clearly contains at least two vertebrae that are very similar to what you find in the tails of dinosaurs. Because of the remains of preserved tissue, it is hard to distinguish more individual vertebrae, but based on the size of the two that can be distinguished, it is thought that this specimen preserves eight full vertebrae and part of a ninth. Based on the structure of the fossil, the authors think that the specimen contains only part of the tail, and they estimate that the full tail might have contained more than 25 vertebrae.

Why is this important? Because while there are birds with bony tails, they typically have less than 10 vertebrae. If this creature had more than 25, most paleontologists would say it clearly isn’t a bird. I am not a paleontologist, but I question that idea. While most bony-tailed birds have very few vertebrae in their tails, there are at least two fossils of what I think are clearly birds, and each of them has at least 20 vertebrae.

Archaeopteryx, for example, is clearly a bird, at least as far as I am concerned. It has all the important characteristics of birds, and it could fly. In my mind, that makes it a bird. You can argue that it is some kind of transitional fossil, but I find the evidence for that idea to be very weak. It has at least 20 vertebrae in its tail. Jeholornis is another example of a fossil bird with more than 20 vertebrae in its tail.

So it’s possible that this fossil belonged to a long-tailed bird like Archaeopteryx or Jeholornis. The problem with that idea, however, is the feathers themselves. The authors make the strong case that if the animal was covered in feathers like the ones preserved in the fossil, it would not be capable of flight. Thus, if this is a bird, it seems it was a flightless bird, which would be quite different from Archaeopteryx and Jeholornis.

So is this fossil from an ancient long-tailed bird or a feathered dinosaur? The honest answer is that nobody knows. It seems to me that there are at least three possibilities: It might be from a feathered dinosaur. It might be from a flightless, long-tailed ancient bird. It might be from a long-tailed bird, but the flight feathers didn’t get preserved for some reason. Hopefully, more fossils will be found to help us determine which of those possibilities (if any) is the correct one.

Based on what we know right now, however, I would say that the most obvious interpretation of the fossil is that it came from a feathered dinosaur. Thus, this makes me more inclined to believe that at least some dinosaurs had feathers. Now please understand that these are real, fully-developed feathers. They aren’t the “dino fuzz” that some paleontologists believe covered some dinosaurs. There are serious problems with that idea.

December 6, 2016

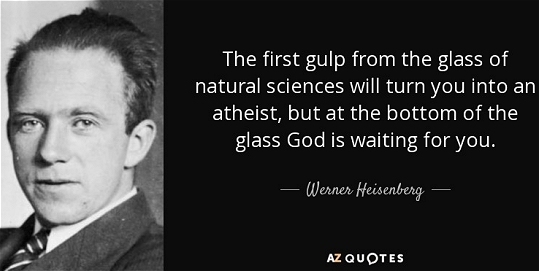

Memes: Spreading False Ideas Since 1980

If you have spent much time on the internet, I am sure you have seen memes like the one shown above. They usually contain a picture and some sort of message. I really enjoy the funny ones, but I typically don’t like the serious ones. It’s not because I don’t enjoy being serious. It’s because you rarely know whether or not the information in the meme is trustworthy. Consider, for example, the meme shown above. It attributes a quote to Dr. Werner Heisenberg, a giant in the field of quantum mechanics. Indeed, his work continues to guide our understanding of the atomic world. I fully agree with the quote, and I deeply respect Dr. Heisenberg. There is only one problem: the meme is almost certainly false.

A Facebook friend posted it on my wall because she knew that I would agree with it. However, I had read a lot of Heisenberg’s work, and the quote didn’t seem to fit the person who I had come to know through my reading. Consider, for example, his main work on the relationship between science and religion. It is called “Scientific Truth and Religious Truth,” and it was published in 1974 (two years before his death) in Universitas, a German review of the arts and sciences. In that work, he seems to argue that science and religion each arrive at truths, but the truths are unrelated to one another. Consider, for example, his own words:

The care to be taken in keeping the two languages, religious and scientific, apart from one another, should also include an avoidance of any weakening of their content by blending them. The correctness of tested scientific results cannot rationally be cast in doubt of religious thinking, and conversely, the ethical demands stemming from the heart of religious thinking ought not to be weakened by all too rational arguments from the field of science.

This is a common view among religious scientists. It often called the “Nonoverlapping Magisteria” (NOMA) view, and it was championed by Dr. Stephen Jay Gould, an ardent evolutionary evangelist who died in 2002. I strongly disagree with the NOMA view, so when I read Dr. Heisenberg’s work, I was disappointed that he seemed to hold to it.

Obviously, someone who holds to the NOMA view would not say that God is waiting for you after you have drunk your fill from the “glass” of the natural sciences. Since Heisenberg wrote most of his work in German, I decided to use my limited knowledge of the language (which always amused my German Ph.D. adviser) and Google Translate to reconstruct the original quote. Using the German version (“Der erste Trunk aus dem Becher der Naturwissenschaft macht atheistisch; aber auf dem Grund des Bechers wartet Gott”), the earliest reference I am able to find is in a 1979 book entitled 15 Jahrhunderte Würzburg. It is a history of Würzburg, the German city where Dr. Heisenberg was born. The quote appears in the margin of the text, attributed to him without any reference. It was picked up by many other authors, so it appears in many other books. As far as I can tell, however, this is its first appearance in print, and it occurred three years after Dr. Heisenberg’s death.

Given the facts that Dr. Heisenberg seemed to hold to the NOMA view, the first appearance of the quote seems to be three years after his death, and there is no reference for the quote, I think it’s safe to say that it was never uttered or written by Dr. Heisenberg. However, because of the reading I did for my elementary textbook Science in the Scientific Revolution, I recognized the essence of the quote. Sir Francis Bacon (1561-1626) wrote an essay entitled “Of Atheism,” and in that essay, he wrote:

It is true, that a little philosophy inclineth man’s mind to atheism; but depth in philosophy bringeth men’s minds about to religion. [Note: At this time in history, science was called “natural philosophy.”]

So while the quote in the meme above almost certainly isn’t real, its essence was written by a scientist who lived about 300 years before Dr. Heisenberg.

The meme is unfortunate in at least two ways. First and foremost, it communicates false information. Second, there is no need for it. If you want to demonstrate that there are great scientists who were or are also believers, you can do that with real quotes from great scientists of the past and the present. Consider, for example, just a few:

“But the context of religion is a great background for doing science. In the words of Psalm 19, ‘The heavens declare the glory of God and the firmament showeth his handiwork.’ Thus scientific research is a worshipful act, in that it reveals more of the wonders of God’s creation.” -Dr. Arthur Leonard Schawlow, who shared the 1981 Nobel Prize in Physics with Nicolaas Bloembergen and Kai Siegbahn

(Cosmos, Bios, Theos, Henry Margenau and Roy Abraham Varghese, ed., Open Court Publishing 1992, p. 106.)

“The significance and joy in my science comes in those occasional moments of discovering something new and saying to myself, ‘So that’s how God did it.’ My goal is to understand a little corner of God’s plan.” -Dr. Henry F. Schaefer, III, director of the Center for Computational Chemistry at the University of Georgia

(Henry F. Schaefer, Science and Christianity: Conflict Or Coherence?, The Apollos Trust 2003, p. 42)

“In the case of our human friends we take their existence for granted, not caring whether it is proven or not. Our relationship is such that we could read philosophical arguments designed to prove the non-existence of each other, and perhaps even be convinced by them – and then laugh over so odd a conclusion. I think it is something of the same kind of security we should seek in our relationship with God. The most flawless proof of the existence of God is no substitute for it; and if we have that relationship, the most convincing disproof is turned harmlessly aside. If I may say it with reverence, the soul and God laugh together over so odd a conclusion.” -Sir Arthur Stanley Eddington, one of the most important astronomers of the 20th century

(A. S. Eddington, “Science and the Unseen World,” The 22nd Swarthmore Lecture, July 22, 1929)

If you want to demonstrate that science can lead people to belief in God, once again, you can do so with real quotes, such as these:

“Both religion and science require a belief in God. For believers, God is in the beginning, and for physicists He is at the end of all considerations.” -Max Planck, who won the Nobel Prize for Physics in 1918

(Max Planck, Scientific Autobiography and Other Papers, F. Gaynor, trans, Philosophical Library 2007, p. 184)

“Now if there is one Hallmark of true science, if there is one perception that scientific knowledge heightens, it is the spirit of wonder; the deeper that one goes, the more profound one’s insight, the more is one’s sense of wonder increased…Now this sense of wonder leads most scientists to a Superior Being…A Superior Intelligence, The Lord of all Creation and Natural Law.” -Abdus Salam, who shared the 1979 Nobel Prize in Physics with Sheldon Glashow and Steven Weinberg

(Abdus Salam, “Science and Religion: Reflections on Transcendence and Secularization,” in Cosmos, Bios, Theos, Henry Margenau and Roy Abraham Varghese, ed., Open Court Publishing 1992)

There is simply no need to manufacture quotes that tell us how science can lead a scientist to believe in God. I can say that with some confidence, since science led me to believe in Him.

December 1, 2016

Howard Edmund Wile: The Man Who Showed Me How to Live

My dad on a cruise ship, where he loved to feel the rolling deck under his feet.

What does it mean to be a father? When my wife and I adopted our only child, I thought a lot about that question. I came up with various answers, none of which were really satisfactory. However, something happened on Tuesday night that put it all into focus for me: my own father passed into the arms of his Savior. The event wasn’t a surprise. From the time I was in high school, my dad had severe health issues. However, over the past year and a half, his health deteriorated severely. More than a week ago, he stopped getting out of bed. A few days ago, he stopped eating. We all had time to prepare for the inevitable.

Of course, when the inevitable actually occurs, you find you aren’t prepared for it at all. The reality is that even when a person is bedridden and hardly able to muster the energy to speak with you, he is still there. When he dies, he is no longer there. He is simply gone, and there is no way to prepare oneself for that. Because of this gaping hole left in your world, you are forced to think about things differently. As a result, I think I have finally come up with the answer to my question.

While writing his obituary, I was forced to think about who my dad was. He was a sailor, having defended freedom in World War II and the Korean War. He was a part of the criminal justice system. He was a tireless volunteer for the Republican party, his church, and many community organizations. But of course, to me, he was much more than that. He was my dad. And he was really, really good at it.

What made him good at it? I thought about that question for a long, long time, and suddenly, a quote popped into my head. It was from a book on parenting I had read while we were in the process of adopting our daughter. The book itself was so unremarkable that I don’t remember its title. Perhaps because it was in such an unremarkable book, the quote meant little to me at the time. However, in the light of thinking about my own father’s life, its profound truth struck me. With a little help from Google, I got the actual quote as well as its source. When speaking of his own father, Clarence Budington Kelland said:

He didn’t tell me how to live; he lived, and let me watch him do it.

In a nutshell, that’s why my dad was such a good father. He showed me, on a daily basis, how a Christian man should live. He demonstrated to me how a man cares for his family, how a man prioritizes his life, and how a man deals with those who are less fortunate than himself.

Howard Edmund Wile showed me how to live. When I see him in heaven, the first thing I am going to do is thank him for that.

November 29, 2016

Antarctic Ice Still a Mystery

A German ship (The Gauss) in Antarctic Ice, as seen from a balloon in 1901.

(credit: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration/Department of Commerce)

Ice in the Arctic has been on a shaky-but-steady decline for the past 25 years, perhaps even longer. Many point to this decline as evidence for global warming. If that were the case, however, ice in the Antarctic should be declining as well, but it isn’t. A recent scientific paper that attempts to put Antarctic sea ice in historical context states this problem succinctly:

In stark contrast to the sharp decline in Arctic sea ice, there has been a steady increase in ice extent around Antarctica during the last three decades, especially in the Weddell and Ross seas. In general, climate models do not to capture this trend and a lack of information about sea ice coverage in the pre-satellite period limits our ability to quantify the sensitivity of sea ice to climate change and robustly validate climate models.

In other words, the computer models that are based on our understanding of global climate predict that global warming should be causing a decline in both Arctic and Antarctic sea ice. However, that’s not what’s happening, at least according to the satellite record, which has been around for a little over 35 years. As a result, the authors of this paper decided to do something innovative: attempt to find out how much ice was in the Antarctic roughly 100 years ago.

How did they do it? They examined the logbooks of explorers who attempted to reach the South Pole during the Heroic Age of Antarctic Exploration, which took place from the late 1800s to the early 1900s. Using those logbooks, the authors were able to produce what seems to be a fairly accurate map of the edge of Antarctic sea ice during that time period. However, these data don’t help to resolve the conflict between the Arctic ice record and the Antarctic ice record. In fact, they seem to amplify the problem.

The study indicates that 100 years ago, Antarctic sea ice was, at most, 14% more abundant than it is today. However, most of that excess ice was concentrated in one region: the Weddell Sea. Ice in the rest of Antarctica in the early 1900s was very comparable to what we see today. Nevertheless, taken all together, the data do indicate that there has been a decline in Antarctic sea ice over the past 100 years or so. Surprisingly, this just adds to the confusion over Antarctic sea ice, at least when these data are added to the other data that have been collected over the years.

Consider, for example, an ice-core study that was published 13 years ago. It indicates that in the 1950s, Antarctic sea ice was roughly 20% more abundant than it was in the early 2000s. Other studies agree. If those studies and this current study are accurate, Antarctic sea ice increased from the 1900s to the 1950s, then decreased from the 1950s to some point before 1980, and then started increasing again.

Obviously, then, the behavior of Antarctic sea ice is complicated. Most likely, this is because the local climate of Antarctica is complicated. I suspect that local effects are far more important than global effects when it comes to sea ice in a specific location. As a result, I would think that the amount of ice at either pole is more indicative of local climate than it is of global climate.

Thus, just as the increase in Antarctic ice is not an indicator of global cooling, I doubt that the decrease in Arctic ice is an indicator of global warming.

November 22, 2016

The Latest Numbers on Homeschooling From The U.S. Department of Education

Homeschooled students building a trebuchet

(click for credit)

Since each state has its own laws regarding home education, it is very difficult for the federal government to track homeschooling families. As a result, the estimates regarding the number of homeschooled students is probably low and the sample that was studied is probably not totally representative of the homeschooling population. Also, the detailed statistics are based on a survey called the “Parent and Family Involvement in Education Survey.” Of the more than 17,000 students covered in that survey, only 397 were homeschooled. Thus, the statistics are based on a relatively small sample of students. Nevertheless, some of the results are worth noting.

First, the report tries to adjust its results to take into account the fact that it can’t track all homeschooling families. Based on the data and the subsequent adjustments, the report estimates that there were 1,773,000 students being homeschooled in 2012. This did not include students who were being temporarily homeschooled (because of a long-term illness, for example). This translates to roughly 3.4% of the population, which represents a doubling of the percentage of homeschooled students in 1999 and an 18% increase from the time of the previous report (2007). Needless to say, then, homeschooling is becoming more common.

Before I give you the next interesting statistic, I want you to think about the answer to the following question:

Are homeschooling parents generally more or less educated than the rest of the population?

I have heard people suggest both answers to that question. Some view homeschoolers as people who do not value “real” education, so they are less educated, on average, than the rest of the population. Others view homeschoolers as those who value education more than the rest of the population, so they are more educated. Based on this survey, the education level of homeschooling parents is roughly equivalent to that of the rest of the population. 25% of homeschooling parents have a Bachelor’s degree, while according to the U.S. Census Bureau, 32% of U.S. adults have one. 18% of homeschooling parents have a graduate or professional degree, compared to 12% of U.S. adults. Only about 2% of homeschooling parents don’t have at least a high school degree, compared to about 12% of U.S. adults.

I now want to present the most interesting of all the statistics, but before I do, I want you to once again answer the following question:

What is the most important reason homeschooling parents choose to homeschool their children?

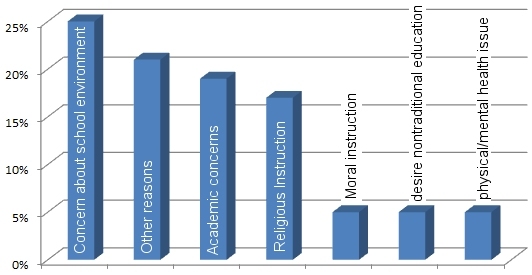

I have asked this question to many friends who homeschool and many friends who do not. By far, most of my friends think that homeschooling parents choose to homeschool primarily for religious reasons. However, that’s not what this survey indicates. The survey asked homeschooling parents for all the reasons they homeschool, and then for the main reason they homeschool. There were several suggestions given, and the parents could also give their own reason. The following graph gives the results for the parents’ most important reason for homeschooling:

As you can see, religious instruction comes in fourth, behind concerns about the school environment, other reasons, and concerns that schools don’t provide adequate academic instruction. That is definitely not what I (or most of my friends) would have predicted! As a side note, you might be interested in what the parents meant by “other reasons.” According to the report, most of those reasons were specific to the particular family, such as travel, finances, and distance to a school.

Homeschooling has definitely changed over the years. As it has become a more common choice among parents, the reasons for making that choice and the type of parents who homeschool have changed. As time goes on, I expect homeschooling to continue to grow as a percentage of the population. As a result, I expect the homeschooling community to become even more diverse in their views and their reasons for homeschooling.

November 16, 2016

Radiation Probably Did Harm the Apollo Astronauts

The astronaut in this Apollo 17 photo was probably harmed by the radiation to which he was exposed on his voyage.

The earth has been magnificently designed for life. Amongst its amazing contrivances for nurturing and protecting living organisms, its magnetic field shields its surface from most of the high-energy radiation to which it is exposed. If it weren’t for this protective shield, life as we know it could not exist on earth. So what happens when people venture beyond that protective shield? A recent paper in the journal Scientific Reports attempts to answer that question by studying astronauts. While it suffers from the unavoidable weakness of using a very small group of individuals, the results presented in the paper are very interesting.

The researchers who wrote the paper examined five women and 37 men who had spent some time in space. All five women and 30 of the men experienced low-earth orbit, while seven of the men were a part of the various Apollo missions that went to the moon. These astronauts were compared to three women and 32 men who have been trained as astronauts but have never gone into space. Both of those groups were also compared to the U.S. population of the same age range. Specifically, the researchers were looking for the mortality rates among the astronauts, as well as what caused their deaths.

What they found was that the astronauts who never went into space were less likely to die from cardiovascular disease and other common ailments (such as cancer) than the rest of the population in the same age range. This makes sense, since health is one of the factors used to choose astronauts, and their training keeps them healthy. However, they were more likely to die from accidents than the rest of the U.S. population. Once again, this makes sense, since being an astronaut is a dangerous line of work.

However, when the astronauts who never went into space were compared to the Apollo astronauts, there was one striking difference.

The percentage of Apollo astronauts who died of cardiovascular disease was five times greater than the corresponding percentage in the group of astronauts who never went into space! Surprisingly, there were no significant differences in the others causes of death. Thus, as far as these results indicate, traveling to the moon and back increases a person’s risk of death by cardiovascular disease, but not death by cancer or other diseases!

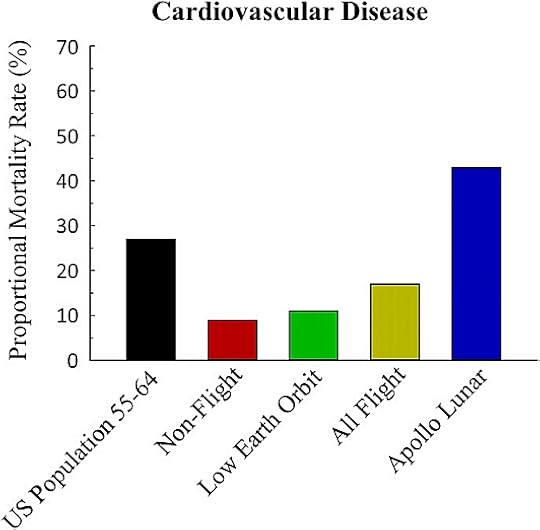

What about the astronauts who didn’t go all the way to the moon? Here is a graph from the paper, which shows the percentage of deaths due to cardiovascular disease among all the groups studied:

In this graph, the “non-flight” results are for those astronauts who never went into space. The “low earth orbit” results are for the astronauts who went into space but not to the moon. The “Apollo lunar” results are for those who went to the moon, and the “all flight” results represent the combined results for the “low earth orbit” group and the “Apollo lunar” group.

It’s very important to understand that there are statistical considerations you must make when viewing these results. Because the number of astronauts studied is low, some differences between them can crop up as a result of random chance. Thus, even though the percentage of low-earth orbit cardiovascular deaths is higher than the non-flight cardiovascular deaths, the difference is not statistically significant. That means we don’t know whether the difference you see in the graph is the result of random chance or is real. However, despite the small group size, the difference between the “Apollo lunar” group and the other astronauts is probably real, because statistical considerations indicate that it is significant.

Does this mean we know for sure that a trip to the moon increases your chance of dying from cardiovascular disease? No. However, this study does provide some evidence to suggest that. If this had been the end of the study, I probably wouldn’t have blogged about it, since the number of people studied is so small that even when you do the statistical tests, you can’t be confident that the difference seen in the study is real. However, the researchers did one more thing that adds weight to their results.

The researchers studied mice under three different conditions and compared them to a control group that were give no special conditions. They elevated the hindquarters of some mice for 14 days. This is a common technique used to simulate weightlessness for the hind legs. They irradiated another group of mice to simulate the radiation experienced by astronauts. They did both of those things to a third group of mice. Compared to the control group, they saw no difference in various cardiovascular indicators in the mice who were given only simulated weightlessness, but they did see elevated problems in the cardiovascular indicators of the mice that were irradiated as well as those who experienced both simulated weightlessness and irradiation.

While there still needs to be further study on this issue, I do think the paper provides good evidence that space travel can elevate a person’s risk due to cardiovascular disease. Furthermore, it is probably mostly due to the increase radiation exposure.

Of course, that would never cause me to turn down an opportunity to travel to the moon or another planet!

November 8, 2016

The Reviews (At Least Some of Them) Are In!

The cover of my new chemistry book

If you haven’t been reading this blog for a while (and didn’t notice the ad on the right), you might not know that I have written a new high school chemistry course: Discovering Design with Chemistry. My previous course, Exploring Creation with Chemistry, Second Edition, was updated by different authors, and I didn’t like the result. Consequently, I thought it necessary to write a new course so that home educated students could have a scientifically accurate, user-friendly, up-to-date resource with which to study chemistry at the high school level. I already discussed the user-relevant differences between my old chemistry course and my new one, so I won’t rehash that. Instead, I want to share some reviews and comments the new course has received.I will start with the most recent one, which comes from a teacher who is facilitating classes that use the book. She discusses the fact that my old chemistry course prepares students very well for chemistry at the university level, and then she says:

Wondering about Dr. Wile’s new Chemistry text? We’re about 1/3rd of the way through the text at two class day programs. There are new experiments, which are a great addition to the topics. The topics go a little more in depth and are in a different order than the previous edition.

I highly recommend his new textbooks, including his new elementary series which I’ve taught to 5th/6th grade students for over a year now.

I am really glad that she mentioned the new experiments, because I think they are the main reason to use my new chemistry course instead of a used copy of my old chemistry course. The old chemistry course is still a good one, but the experiments in the new course are significantly better. If you would like to see some of them, this student is posting videos.

Over at Christian Book Distributers, there are also a couple of reviews. The most recent one starts out this way:

This is such an excellent chemistry course. I took AP chemistry in high school and again in college, but those courses did not explain things as well as this course by Dr. Wile. His conversational style and clear/straightforward examples make the material approachable.

She then goes on to mention the online helps, which many people (even some who use the course) don’t know about. There is a website that goes with the course. On that website, there is a link for every chapter, and that link takes you to a list of videos that help explain the topics being discussed in the chapter. Thus, if a student doesn’t “get it” after reading the way I explain it, he or she can go online to watch a video explanation. Also, because you can never be sure what will “pop up” on YouTube, the course website shows the videos through SafeShare.tv. That way, the only thing the student sees is the video itself.

In addition to the video explanations, there are extra problems for every chapter. The problems are in one PDF file, and the solutions are in a different PDF file. So if a student isn’t comfortable after answering the 30+ questions and problems in the chapter, he or she can get the extra problems online, solve them, and then check the solutions. Also, if you click on “Links for the entire book,” you will find a link to a PDF that contains worksheets for the course. The worksheets have all the student problems that are in the book, with space in between so that the student can solve the problem right there on the worksheet. Like the videos, these worksheets are free!

Finally, there is a free question/answer service for the course. The introduction to the book points you to a website that allows you to review answers to questions that have been asked by others, and you can also ask your own questions. This means that the student has access to a free “tutor,” who can answer any questions the student has about the course.

I have also received a few private messages regarding the course. One of them read, in part:

This is just a quick note to let you know that we are LOVING Discovering Design with Chemistry. I mean, really love it!…We are truly loving this curriculum and as a family, we feel so blessed to have found this.

I can’t tell you what it means to me when I read “loving” and “chemistry” in the same sentence! Finally, here is what one student wrote:

Hi! I just wanted to let you know how much I have enjoyed Discovering Design With Chemistry. I am a tenth-grade homeschooled student, and I really learned so much through this book. After taking this course, I know I will definitely take Advanced Chemistry in my senior year, and I will seriously consider studying chemistry in college as well. I found chemistry to be enjoyable and exciting through your work! Thank you!

That’s the kind of review that makes my heart sing! It’s wonderful to know that my course has made at least one student consider studying chemistry at the university level!

For completeness sake, here are links to the other reviews of which I am aware:

October 31, 2016

Does science undermine human rights? No, But Materialism Might.

Image copyright Benjamin Haas via shutterstock.com.

If you have been reading this blog much, you probably know that while I am not smart enough to be one, I play at being a philosopher. As a result, I read a lot of philosophy, and I discuss it from time to time on this blog. If you have bothered to plow through what I have written on the subject, you might also know that I think the Argument From Morality is one of the worst arguments for the existence of God. Nevertheless, as any scientist should be, I am willing to change my mind on the subject, if I am presented with evidence that challenges my position. Recently, I stumbled across some of that evidence, and while it is not enough to change my mind on the subject, it makes me less certain of my derision for the argument from morality.

The evidence comes from Dr. John H. Evans, Professor & Associate Dean of Social Sciences at the University of California, San Diego. He wrote an article for New Scientist in which he summarizes his original research, published in an Oxford University Press book entitled, What is a Human? What the Answers Mean for Human Rights. In this research, he surveyed 3,500 adults in the United States, asking their opinions on humans and human rights.

He started by asking them how much they agreed with three different definitions for human beings:

I. The Biological Definition: Humans are defined (and differentiated from the animals) by their DNA.

II. The Philosophical Definition: Humans are defined by specific traits, like self-awareness and rationality.

III. The Theological Definition: Humans are created beings that have been given the image of God.

Here is how he describes the questions that followed:

I also asked them how much they agreed with four statements about humans: that they are like machines; special compared with animals; unique; and all of equal value. These questions were designed to assess whether any of the three competing definitions are associated with ideas that could have a negative effect on how we treat one another.

I finished with a series of direct questions about human rights: whether we should risk soldiers to stop a genocide in a foreign country; be allowed to buy kidneys from poor people; have terminally ill people die by suicide to save money; take blood from prisoners without their consent; or torture terror suspects to potentially save lives.

His results were quite surprising to me, but not to those who promote the Argument From Morality.

He found that only 25% of the public agreed with what he called the “biological” definition of a human being. That’s good news, since I think it is the worst possible definition of a human being. Scientifically, it is quite clear that we are much, much more than our DNA. Nevertheless, I would think that anyone who is a materialist (a person who thinks that life on earth, and human beings in particular, are just the result of natural processes) would have to agree with that definition. Such a person might also agree with the philosophical definition, but in the end, he or she would have to agree that at best, the traits that define human beings in the philosophical definition are solely the product of the human being’s DNA and environment. Ultimately, then, they are back to the biological definition for human beings.

The bad news is that for those 25%, their views on human rights are more likely to be immoral. The more the respondents agreed with the biological definition of life, the more likely they were to think of people as machines, the less likely they were to see humans as unique, and the less likely they were to agree that all people are of equal worth! As the italics indicate, I find that last statement to be the most shocking. Even from a purely materialist point of view, one should be able to see that all people are of equal worth. After all, to the materialist, we are all products of the same evolutionary process and have essentially the same DNA. Thus, from a logical point of view, we should all be of equal worth, even to the materialist. Dr. Evans’s research seems to indicate that isn’t true.

When it comes to human rights, the results are even more shocking. The more the respondents agreed with the biological definition of life, the less likely they were to say that we should risk soldiers to stop genocide. They were also more likely to say that we should be able to buy kidneys from poor people, have terminally ill people commit suicide to save money, and take blood from prisoners against their will. As Dr. Evans concludes:

People who agree with the biological definition of a human are also more likely to hold views inconsistent with human rights.

Now, of course, Dr. Evans indicates that his study is not the last word on the topic, and that’s clearly true. Also, he makes the important point that his study was about what people think, not what they actually do. It’s possible that when it comes to the actions they take, people’s view on the definition of a human being doesn’t play nearly as important a role. Nevertheless, his results are striking.

While I am way, way, way behind on my reading, I do plan to read his book and see if I can gain any more insight. For example, I am curious if there is any trend in the beliefs of those who are more likely to agree with the philosophical definition of a human being, which is at least a step closer to the truth than the biological definition. Nevertheless, I do think that this study gives weight to the idea that without a God concept, most people are less likely to have a good moral sense.

October 24, 2016

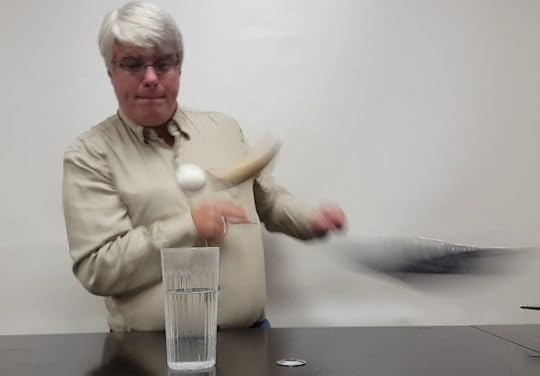

A Demonstration About Inertia

My publisher asked me to record an example experiment from the third book in my elementary science series, Science in the Scientific Revolution. This one is about inertia, and I cover the topic when I cover Sir Isaac Newton. It’s a potentially messy experiment, because in your desire to hit the pie pan hard, you might end up hitting the glass of water, knocking it over. Also, if you don’t hit the pie pan hard enough, you might end up just upsetting the system, resulting in a broken egg. However, if you can do the experiment correctly, it’s pretty impressive.

The concept of inertia was an important step forward in our understanding of motion. Up until the 14th century, most natural philosophers (that’s what scientists were called back then) believed what Aristotle taught: objects have a natural tendency to be at rest. Thus, unless something kept exerting a force on an object, an object in motion would eventually come to rest. This is consistent with our experiences. After all, if I kick a rock, it bounces down the sidewalk for a while, but it eventually comes to a halt. Even though Aristotle’s teaching is consistent with our experiences, it is nevertheless quite wrong.

In the 14th century, Jean Buridan (a natural philosopher whose work I discuss in Science in the Ancient World) questioned Aristotle’s teaching on the matter, indicating it wasn’t consistent with at least some observations. However, it took the work of Galileo Galilei to show that there was something seriously wrong with the idea. He ended up correcting Aristotle a bit. He said that at least when it came to motion on a level surface, objects will continue to move the way they have been moving, until they are disturbed.

Sir Isaac Newton ended up generalizing this principle, producing his First Law of Motion:

A body at rest or in motion will stay at rest or in motion until acted on by an outside force.

When you kick a rock, it starts bouncing down the sidewalk, and it would continue to do that forever if it weren’t for the outside force of friction. That force slows the rock down until it comes to rest. So the rock doesn’t come to a halt because its natural state is to be at rest. The rock has no natural state. It is simply responding to the forces acting on it. A kick gives it some motion in the direction of the kick, but friction opposes that motion, eventually forcing the rock to a halt.

One of the most spectacular confirmations of Newton’s First Law of Motion can be seen in the Voyager spacecraft. Despite the fact that neither of them has been been receiving any power from their engines for nearly 40 years now, they are still steadily moving away from the earth. Their engines gave them some velocity in that direction, and since there is almost no friction in space and they are far from the gravitational fields of the planets, they are not being acted on by a significant outside force. As a result, they have continued to move away from earth to the point where one of them is outside our solar system and in interstellar space.

Jay L. Wile's Blog

- Jay L. Wile's profile

- 31 followers