Jay L. Wile's Blog, page 17

August 12, 2019

Forbes Censors Article About a Scientist Who Is Skeptical of Climate Hysteria

Dr. Nir Shaviv speaking in Australia

Dr. Nir J. Shaviv is an astrophysicist of some renown. He has over 100 scientific papers to his credit and is currently chairman of the Racah Institute of Physics at The Hebrew University of Jerusalem. I think it’s safe to say that Dr. Shaviv knows a thing or two about science and how it is done. One of his specialties is studying the effect that cosmic rays from the sun have on the earth’s climate. So just to make it clear. Dr. Nir Shaviv is a well-respected scientist who has published peer-reviewed research specifically about earth’s climate.Does this mean we have to believe what Dr. Shaviv says when it comes to earth’s climate? Of course not. However, it does mean that he is a recognized expert in the field. Even when I disagree with experts, I still try to pay attention to what they say and the data they produce, because they know more than I do when it comes to the issue I am investigating. Thus, while I certainly don’t have to agree with the conclusions of any given expert, I do have to at least try to understand the data the expert has collected and why he or she thinks they point to a certain conclusion. If I don’t do that, I am no longer thinking scientifically. After all, the only way you can make a scientific conclusion is to consider all of the data. Ignoring data because I don’t agree with the source is not scientific; it is emotional.

Why am I bringing this up? Because last night, I was scrolling through a news feed and noticed a Forbes article entitled, “Global Warming? An Israeli Astrophysicist Provides Alternative View That Is Not Easy To Reject.” Obviously, that title was very interesting to me, so I clicked on the link. Unfortunately, what I found was a message that said:

After review, this post has been removed for failing to meet our editorial standards.

We are providing our readers the headline, author and first paragraphs in the interest of transparency.

We regret any inconvenience.

This seemed rather odd to me, so I decided to do some digging. What I found did not reflect well on Forbes.

As Erica Albright says in The Social Network:

The internet is not written in pencil, Mark. It’s written in ink.

Knowing this, I went searching for the article that Forbes claims does not meet its editorial standards. I used my favorite tool for this purpose (mostly because of the name), The Wayback Machine. I found the article and read it in its entirety. What I found was an excellent article that clearly explains one respected scientist’s view of the global warming hysteria that certain high-profile scientists and politicians are promoting. Since then, it has been posted elsewhere, in a form that is probably easier for most browsers to read.

Please read the article for yourself. While reading, try to spot what caused Forbes to decide that it didn’t meet their editorial standards. The only thing I can think of is that the respected scientist had the audacity to question the narrative that global warming is going to lead to the end of the world as we know it. Indeed, he even mentioned the nonsensical assertion that 97% of all climate scientists agree with the narrative:

Only people who don’t understand science take the 97% statistic seriously…Survey results depend on who you ask, who answers and how the questions are worded. In any case, science is not a democracy. Even if 100% of scientists believe something, one person with good evidence can still be right.

Even though that statement is 100% correct and fundamentally important to understanding the very nature of science, it flies in the face of the narrative that some high-profile scientists and politicians are pushing. As far as I can tell, Forbes decided the article didn’t meet its “editorial standards” because it failed to support that narrative.

August 8, 2019

One Way To See How Special Earth Is

A sample of the exoplanets “conservatively” thought to be in their star’s habitable zone, along with familiar planets for scale. (click for credit)

Thirty-five years ago, Dr. Theodore P. Snow wrote a book entitled Essentials of the Dynamic Universe. On page 434 of the 1984 edition, he summed up the obvious consequence of the idea that earth was formed as a result of natural processes without any need for Divine intervention:

We believe that the earth and the other planets are a natural by-product of the formation of the sun, and we have evidence that some of the essential ingredients for life were present on the earth from the time it formed. Similar conditions must have been met countless times in the history of the universe, and will occur countless more times in the future.

In other words, there is nothing special about the earth; it is one of many planets that harbor life. The more we learn about the universe, the more we should realize just how mediocre the earth is.

Since Dr. Snow penned those words, almost 4,000 exoplanets (planets outside our solar system) have been discovered. How many of them are similar to earth? The most reasonable answer, based on what we know right now, is zero. Why? Well, let’s consider one and only one factor: whether or not the planet is in the habitable zone of its star. That’s the distance from the star which allows the planet to get enough energy to stay warm enough to support life as we know it.

Out of nearly 4,000 exoplanets, how many are within the habitable zone? With the recent discovery of a planet charmingly known as “GJ 357 d,” the number of planets that might possibly qualify is 53. If we are conservative in our estimate, the number drops to 19, but let’s be as optimistic as possible. Out of nearly 4,000 exoplanets, only 53 might possibly be in the habitable zone.

What do I mean when I say “might possibly be in the habitable zone?” Well, there are a few factors that influence a planet’s temperature, and the distance from its star is only one of those factors. Another important issue is the planet’s atmosphere. With the right mix and right amount of greenhouse gases, a planet that is a bit far from its star could be in the habitable zone, because even though it gets only a little energy from its star, its atmosphere holds onto that energy really well. In fact, that’s why GJ 357 d might possibly be in the habitable zone. It gets about as much energy from its star as Mars does from the sun, but it is massive enough to hold on to a pretty thick atmosphere. It’s possible that the atmosphere could make up for its distance from the sun, so astronomers say it is possibly at the “outer edge” of the star’s habitable zone.

Now think about that for a moment. If we consider only one factor necessary for a planet to sustain life (being in the habitable zone of a star), just over 1% might possibly have it. Of course, there are lots of other factors necessary for life as we know it. A life-sustaining planet must also have an abundance of water, the right mixture of non-greenhouse gases in its atmosphere, the right mix of chemicals in its crust to provide nutrition to organisms, a shield from both ultraviolet rays and cosmic rays that come from the star around which it orbits, a reasonable speed of rotation around its axis, etc., etc. The earth has all these things, but a survey of nearly 4,000 exoplanets shows that just over 1% have only one of those things. What’s the chance that one of those planets has everything else it needs to support life? The most reasonable answer based on what we know is zero.

Despite what naturalists expect (and most still want to believe), it is clear that the earth is a very, very special planet. One might be so bold as to say that it is the Privileged Planet.

August 5, 2019

Human/Animal Hybrids?

Pallas and the Centaur, by Sandro Botticelli, c. 1482

A Facebook friend posted this article on my timeline, and then a reader of this blog sent me an email that included the same article plus this one. Both articles report on experiments that will attempt to produce human/animal hybrids. This idea obviously makes a lot of people uneasy, so I thought I would explore it a bit here.First, let’s make sure we know exactly what these experiments are trying to accomplish. They are not trying to make some human/animal hybrid like the centaur pictured on the left. Instead, they want to take animal embryos and edit out key genes necessary for the animal to grow a specific organ. They then want to inject pluripotent human stem cells into the embryo. Since pluripotent stem cells have the ability to become any kind of cell, the thought is that the human pluripotent stem cells would grow the organ that the animal embryo cannot grow, resulting in an animal embryo that is growing a human organ. So this is less of a human/animal hybrid and more of an animal/human chimera.

Why would anyone want to do this? Well, it is estimated that more than 7,000 people die every year because they need a transplant but cannot get the necessary organ. This process would greatly increase the pool of organs available for transplant, thus saving many people’s lives.

Now to put this in perspective, we already know that there are human/human chimeras which occur naturally. We know that when a woman is pregnant, some of the baby’s cells get inside the mother and can stay long after the child is born. In addition, the mother’s cells get into the baby and can stay there for a long time as well. There is also evidence that a baby can contribute stem cells to his or her mother in an attempt to aid the mother when she has heart troubles. Thus, for at least a long while, pregnant women and babies are chimeras, each harboring some of the other’s cells.

Of course, animal/human chimeras are quite different, since they mix species. Is it ethical to attempt to make them? Well, first we have to worry about the source of the human stem cells. Political propaganda that is pretty much devoid of scientific reasoning would have you believe that the only really pluripotent stem cells are the ones harvested from embryos. That process murders the embryo, so clearly, the acquisition of such stem cells is utterly immoral. Fortunately, science tells us that adult stem cells, which can be removed from the body without murder, are pluripotent and very effective. Science also tells us that normal cells can be induced into becoming pluripotent stem cells. So if the human stem cells are adult stem cells or induced pluripotent stem cells, at least no murder is involved.

But what about producing an animal embryo that has a human organ in it? Even if the human stem cells used are ethical, is the product ethical? I honestly don’t know. Obviously, the animal embryo will die, because once the organ is harvested, the animal won’t be able to survive. However, we kill animals all the time to allow us to have better lives, so I don’t see that as a problem. However, the idea of having a human organ in an animal is, at least, unsettling.

Once again, however, to put things into perspective, this isn’t new research. Indeed, the scientist who plans on making monkey/human chimeras has already tried to do it with pigs and induced pluripotent stem cells, and it didn’t go well. While a few of the human cells survived, they didn’t contribute to the pig embryo in any meaningful way. The scientist thinks that monkeys might work better, since they are more genetically similar to humans.

I am interested to hear what my readers think. As mathematician Ian Malcom says in the only good Jurassic Park movie:

Your scientists were so preoccupied with whether or not they could, they didn’t stop to think if they should.

Do you think that scientists should? Why or why not?

July 24, 2019

Data Indicate That Earth Was Warmer in The Middle Ages

Inferred temperatures for Antarctica as a Whole over the past 1500 years.

(graph from study being discussed)

For some time, climatologists have accepted the fact that from about the year AD 1000 to AD 1200, the temperature of the Northern Hemisphere was unusually warm. In fact, most studies indicate that it was warmer than it is today. This period of warm temperatures has been referred to as the “Medieval Warm Period,” the “Medieval Climate Anomaly,” or the “Medieval Climate Optimum.” A few hundred years later, the Northern Hemisphere experienced cooler-than-normal temperatures, and that part of earth’s history is sometimes called the “Little Ice Age.” Many climatologists argue that both the Medieval Warm Period and the Little Ice Age were limited to the Northern Hemisphere. However, a series of studies indicate that these periods of extreme temperatures were experienced worldwide.

I just recently became aware of these studies because the latest one appeared in my news feed. This study used the results of climate proxy data from 60 different sites. If you aren’t familiar with that term, it refers to data that scientists use to attempt to understand climate conditions of the past. Tree rings, for example, are sensitive to temperature and precipitation, so it is thought that we can use them to determine past climate conditions of the region where trees have been growing. Many climate-sensitive things like recorded harvests, coral growth, pollen grains, etc. can be used as climate proxies. The more climate proxies you have for a given region, the more likely you are to be able to determine the local climate conditions over the times for which you have those data.

As I said, the study used proxy data from 60 different sites to reconstruct the temperature of Antarctica over the past 1500 years. The overall graph from the study is given above. As you can see, according to the study, Antarctica was significantly warmer from AD 500 until AD 1250 than it is today. The pink region is the time over which the Northern Hemisphere experienced the Medieval Warm Period, and as you can see, the study’s data indicate that Antarctica was experiencing warmer-than-average temperatures as well. You can also see that those temperatures then fell over the next 750 years or so, producing colder-than-average temperatures. Thus, Antarctica seems to have experienced both the Medieval Warm Period and the Little Ice Age.

Interestingly enough, while the study’s data indicate that the whole of Antarctica experienced both the Medieval Warm Period and the Little Ice age, there were parts that did not. The Ross Ice Shelf region of Antarctica, for example, cooled during the Medieval Warm Period. The Weddell Sea and the Filchner-Ronne Ice Shelf also experienced some cooling during that period. Overall, however, the warming strongly outweighed the cooling, so Antarctica as a whole was warmer during the Medieval Warm Period than it is today. Also, looking at the part of the graph that deals with modern times, it seems that any warming that has occurred recently is simply a “recovery” from the Little Ice Age.

This same group has done similar studies that show that Oceania (the region of the earth that holds Australia, New Zealand, etc.), South America, and Africa/Arabia all experienced the Medieval Warm Period as well. Thus, the authors of these studies say that the Medieval Warm Period was not restricted to the Northern Hemisphere. Instead, it was experienced worldwide. In other words, worldwide temperatures were warmer in AD 1000-1200 than they are today.

While the data seem convincing, I will add one caveat. It is hard enough to measure global temperature today. If we measure global temperature using thermometers scattered across the world, the results look like this. If we use satellites, we get results that are quite different. So we don’t really know what global temperatures are today. Obviously, then, figuring out what global temperatures were from AD 1000 to AD 1200 is fraught with peril. Thus, while the studies’ conclusions are the best we have right now, they are far from certain.

Nevertheless, based on the best data we have, we can say that world was probably warmer before people began burning fossil fuels that it is today.

July 22, 2019

How I Address the Age of the Earth in My Courses

My publisher has been getting several questions about how I address the age of the earth in my science courses. This probably stems from the fact that there is a lot of misinformation going through the homeschooling community regarding my position on the issue. I thought I would try to clear things up with a post.

First, my position on the age of the earth hasn’t changed in more than thirty years. I turned from atheism to Christianity in my late high school years, and at that time, I was happy to believe what my teachers told me about the age of the earth. It was more than four billion years old. I was told that we knew this because of radiometric dating methods, which involved studying the relative amounts of radioactive atoms in rocks and fossils. This “fact” of science was later reinforced when I went to university, so I was still happy to believe it.

Then I started my Ph.D. program in nuclear chemistry. I learned about radioactive decay in detail and started doing experiments with nuclear reactions. Most of my work was done at the University of Rochester Nuclear Structure Research Lab, which also had a group that did radiometric dating. I never did any of that work myself, but I watched them do their experiments, asked them questions, listened to their presentations at the lab, etc. Based on what I learned there, I decided that I couldn’t put much faith in the ages given by radiometric dating.

This caused me to question the age of the earth from a scientific perspective. Theologically, I wasn’t committed to any age for the earth. Certainly the most straightforward interpretation of Genesis is that the universe and all it contains was created in six solar days, and that leads to a young-earth view. At the same time, however, there were early church Fathers (as well as ancient Jewish theologians) who didn’t interpret the days in Genesis that way. So I attempted to investigate the subject with an open mind. I found that in my view, science makes a lot more sense if the earth is thousands of years old rather than billions of years old, so I started believing in a young earth. The more I have studied science, the more convinced I have become that the earth is only thousands of years old.

Second, while I have been a young-earth creationist for more than thirty years, I recognize that there are a lot of wonderful, devout Christians who believe otherwise. Indeed, some of my Christian role models (like Dr. Alvin Plantinga and double-Dr. Alister McGrath) believe that the earth is billions of years old. As a result, in all of my books, I try to avoid being dogmatic. When it is related to the material that is being discussed, I simply present the scientific evidence. When it is not related, I don’t discuss it at all. Here is a rundown of how that plays out in the books that I have written so far:

The first book of my elementary series is called Science in the Beginning, and it covers science using the days of creation to order what the students are studying. The first set of lessons goes with the first day of creation, so students learn about light. The second set of lessons goes with the second day, etc. When the students are done with the book, they have covered all the days of creation, so they have learned a bit about everything that was created. Throughout the course, the length of the days is not mentioned, because we really don’t know how long they were. Thus, it doesn’t make sense to discuss it in an elementary science course.

The rest of the series covers science chronologically, so students learn science in the same order it was learned in history. In these books, the age of the earth is mentioned only when the people being covered did work that addressed it. For example, in Science in the Scientific Revolution, I have a lesson on Bishop James Ussher. While many young-earth creationists rely on his conclusion about the age of the earth, most of them don’t understand how he actually reached it. As a result, I discuss the details of his work so that students know what led him to the conclusion that the earth is thousands of years old.

In the later books of the series, the issue comes up a bit more often. In Science in the Age of Reason, for example, I discuss James Hutton. He observed Hadrian’s Wall, which had been built roughly 1,500 years previously. There was hardly any evidence of erosion in the cut stones that made up the wall. He compared that to rocks that he had studied in nature, which showed evidence of massive amounts of erosion. He decided that in order to account for all that erosion, those rocks must be much older than Hadrian’s wall, so the earth must be truly ancient. In the book, I give a full account of his reasoning, but I then indicate what I think he was neglecting – the fact that large volumes of water can produce massive amounts of erosion in a short time.

In the end, then, if a person was known for work related to the age of the earth, I discuss his views as honestly as I can. If those views aren’t young-earth, I add my own “color commentary,” indicating what I think might be wrong with his reasoning. So while students clearly see that I am a young-earth creationist, they also clearly see the evidence that led others to a different conclusion.

In my junior high and high school courses, I discuss the issue when it is appropriate, but honestly, it doesn’t come up all that often, because it doesn’t relate to a lot of what junior high and high school students study. When I discuss geology in my General Science course (which is no longer being printed by the publisher but is still available here), I give students both the old-earth view of geology and the young-earth view. I then tell them the scientific problems that exist for both views. I also tell them that I am a young-earth creationist, so my discussion is probably a bit biased in favor of that view.

In my Physical Science course, I discuss radioactivity, so I discuss radiometric dating. The students learn the assumptions that have to be made in the process of radiometric dating and the problems that exist with those assumptions. The students also learn about the many inconsistencies that occur when radiometric dates are compared to dates obtained by other methods. The students cover this again in more detail if they take my Advanced Chemistry course.

In my biology course, the issue comes up a couple of times. When I discuss the fossil record, I have to discuss the geological column, and I therefore must discuss the assumptions that are made when interpreting the geological column. I give the old-earth view and the young-earth view, stressing that neither can be confirmed, because there is evidence on both sides. The issue comes up again when dinosaurs are discussed. I indicate that most scientists use the old-earth view of the geological column to conclude that dinosaurs and people did not coexist. I then give the students the scientific reasons that I think they did coexist.

The only other course that addresses the age of the earth is my chemistry course. When I discuss the concept of an absolute temperature scale, I discuss the process of extrapolation. While this is a valuable tool in the scientist’s toolbox, it needs to be used cautiously. I discuss instances where extrapolation is justified, and instances where it is not. I use radiometric dating as an example of the latter.

If you are looking for a science curriculum that dogmatically tells students that the earth is about 6,000 years old or that it is about 4.5 billion years old, you shouldn’t use my curriculum. I want the students who use my curriculum to learn good science, and good science is not dogmatic.

July 11, 2019

In This Case, the Journal Science is Holding Back the Progress of Science

Sometimes, scientific journals hold back the progress of science.

***Please note that while political beliefs are mentioned in this post, it is NOT a political post and political commentary will NOT be approved.***Science is supposed to be self-correcting. The history of science is full of mistakes, but over time, those mistakes are usually found, and the findings are communicated to the scientific community so that the mistakes no longer influence scientific thinking. Unfortunately, one of the main ways that findings are communicated is through scientific journals, and there are times when scientific journals are not interesting in correcting mistakes, especially when those mistakes reflect badly on the journal’s reputation. I recently ran across a story that illustrates this point.

Back in 2008, the most prestigious scientific journal in the United States, the journal Science, published a study that attempted to understand the root causes of political beliefs. They exposed several participants to images and sounds designed to evoke fear and correlated the participants’ response to their political beliefs. Based on their results, the authors concluded:

…individuals with measurably lower physical sensitivities to sudden noises and threatening visual images were more likely to support foreign aid, liberal immigration policies, pacifism, and gun control, whereas individuals displaying measurably higher physiological reactions to those same stimuli were more likely to favor defense spending, capital punishment, patriotism, and the Iraq War. Thus, the degree to which individuals are physiologically responsive to threat appears to indicate the degree to which they advocate policies that protect the existing social structure from both external (outgroup) and internal (norm-violator) threats.

In other words, if you are prone to fear, you are more likely to be a conservative. If not, you are more likely to be a liberal.

The study was ground-breaking, and it has strongly influenced scientific research in the field. Indeed, at the time of this posting, the study has been referenced in 257 subsequent studies. There’s only one problem. It probably isn’t correct. How do we know? Because some researchers who were initially interested in expanding on the results of the study began doing some experiments, but the experiments didn’t seem to support the conclusions of the 2008 study. In an attempt to see what they were doing wrong, the researchers contacted the authors of the 2008 study so that they could replicate their methodology. They weren’t trying to demonstrate that the 2008 study was wrong. In fact, they were trying to use its methodology to “calibrate” their study so that they could get consistent results.

What they found is that they could not replicate the results of the previous study. What is supposed to happen when something like this occurs? It is supposed to be communicated, right? After all, researchers need to know that there was something wrong with a study that is still influencing the field. Where should this be communicated? In the journal that published the original study, of course. That’s what these authors tried to do. They submitted the above-linked paper to the journal Science, and the editors refused to even consider publishing the paper.

When a scientific journal considers publishing a paper, it sends the paper out for peer review. That means other scientists in the field evaluate it to see if they can find any errors in the study. If the reviewers think that small errors exist, the journal might still publish the paper, as long as the authors correct those small errors. If the reviewers think there are serious errors in the paper, the journal will not publish the paper. The problem is that in this case, Science refused to even send the paper out for peer review. They just summarily rejected it, without any evaluation as to its quality.

Why? The editors thought that the field had “moved on” from the initial study (it was 11 years ago, after all), so there was no reason to publish the fact that the initial study was probably wrong. However, we know that is simply false. Of the 257 papers that cite the study, nine of them come from this year, 25 of them from last year, and 41 from the year before. Clearly, then, the initial study is still influencing research in the field, and the journal Science refuses to let scientists in the field know that the study is probably wrong!

I think the authors of the new study say it best:

Science requires us to have the courage to let our beautiful theories die public deaths at the hands of ugly facts…Our takeaway is not that the original study’s researchers did anything wrong. To the contrary, members of the original author team — Kevin Smith, John Hibbing, John Alford and Matthew Hibbing — were very supportive of the entire process, a reflection of the understanding that science requires us to go where the facts lead us. If only journals like Science were willing to lead the way.

July 7, 2019

MIT Professor Writes About Her Conversion from Atheism to Christianity

Dr. Rosalind Picard (click for credit)

Rosalind Picard is a Professor of Media Arts and Sciences at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT). She is also a Fellow with the Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers and was elected to the National Academy of Engineering, which is one of the highest honors that an engineer can receive. She even invented an entire branch of computer science called affective computing. She is obviously an incredibly smart woman who is a very successful in her field. She is also a Christian.Several months ago, one of my readers on Facebook sent me an article Dr. Picard wrote. It describes her journey from atheism to Christianity, and I loved reading it. I really wanted to write about it as soon as I had finished reading, but every time I had a chance to blog, there was something else that I thought I needed to cover. Then I forgot about it. I was probably distracted by something shiny. That happens a lot. Recently, I was reminded of her story, so I want to share it, because in many ways, it is a lot like my own.

Of course, the best way to read her story is to just click on the link above, but I will add a bit of my own “color commentary,” just because I relate to so much of what she has written. For example, aside from the grade school part (it was junior high for me), the first paragraph of her story could have been written by me:

As early as grade school, when I was a voracious reader and a straight-A student, I identified with being smart. And I believed smart people didn’t need religion. As a result, I declared myself an atheist and dismissed people who believed in God as uneducated.

That’s exactly what I thought. My early education had convinced me that all educated people are atheists, and I considered myself to be very well educated, so of course, I was an atheist. She said that she argued for materialistic evolution in a high school debate, because it was “science.” She lost the debate, but blamed it on the ignorance of her classmates, much like modern atheists do today.

What made her even consider Christianity as an alternative? She meet people who were Christians but were also (gasp) really smart and really well educated. One couple convinced her to start reading the Bible, and she was surprised by what she found there. She started with the book of Proverbs and says:

When I first opened the Bible—this was the King James Version—I expected to find phony miracles, made-up creatures, and assorted gobbledygook. To my surprise, Proverbs was full of wisdom. I had to pause while reading and think.

She ended up reading through the Bible twice, struggling against the fact that what she read really resonated with her. She tried to study other religions to get out of this “religion phase.” She then met another smart Christian, and she started to go to church with him. She asked lots of questions, and eventually, she decided to see if there was anything to this Christainty thing. Once again, she writes something I could have written:

It seemed silly to pray about this — after all, I still had doubts about God’s existence. But in the spirit of Pascal’s wager, I decided to run an experiment, believing I had much to gain but very little to lose.

If you aren’t familiar with Pascal’s Wager, it is a clever argument for becoming a Christian. Blaise Pascal was a brilliant philosopher and scientist, but he also loved to gamble. He said believing in Christianity is a gamble. If you believe and are right, you are given infinite reward, because you are in heaven for eternity. If you believe and are wrong, you have given up some finite earthly pleasures in life for no reason. If you don’t believe and are wrong, you have infinite loss, because you spend eternity in hell. If you don’t beleive and are right, you gain some finite earthly pleasures that you would have avoided as a Chrisitian. Essentially, your choices are inifinite reward at the possible cost of losing some finite earthly pleasures, or finite earthly pleasures at the possible cost of infinite loss. From a gambler’s point of view, you need to bet for the infinite reward and against the infinite loss. Thus, Christianity is the best bet.

So Rosalind Picard gambled, and she won! As she says in her closing paragraph:

I once thought I was too smart to believe in God. Now I know I was an arrogant fool who snubbed the greatest Mind in the cosmos — the Author of all science, mathematics, art, and everything else there is to know. Today I walk humbly, having received the most undeserved grace. I walk with joy, alongside the most amazing Companion anyone could ask for, filled with desire to keep learning and exploring.

Amen, Rosalind! Amen!

July 4, 2019

More Global Warming Nonsense

A satellite image of the Great Lakes

One reason the public doesn’t take “climate change” (the disaster previously known as global warming) seriously is because the media report on it so stupidly. Essentially, any bad thing that happens in the world is due to climate change. Consider, for example, the Great Lakes. Their depths started to decline noticeably in the year 2000. In 2007, New Scientist ran a story entitled:

Global warming is shrinking the Great Lakes

This, of course, is exactly what you would think global warming would do. Increased temperatures should increase evaporation rates, causing lake water levels to drop.

Fast forward to today, when the Great Lakes are at record high levels. What could be causing this? Climate change, of course! As PhysicsWorld puts it:

So, what has changed and why have water levels fluctuated so wildly in less than 10 years? Drew Gronewold and Richard Rood of the University of Michigan argue that climate change has disrupted the balance between evaporation and precipitation in the Great Lakes region.

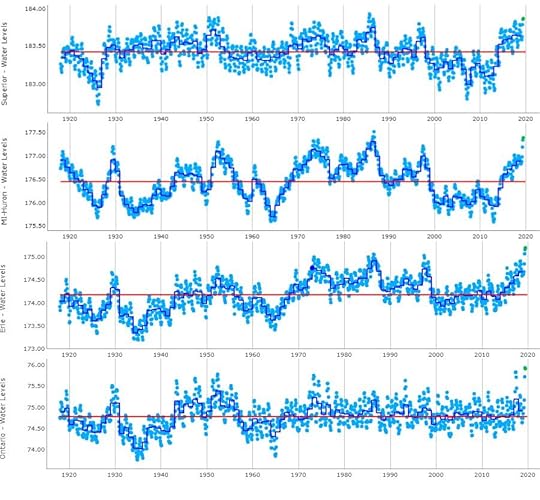

Of course, when one looks at the data (compiled by the NOAA), one sees that there has been no recent “wild fluctuations” in the levels of the Great Lakes. Their levels have varied over the past 100 years, but the variation has not become “wilder” in recent years:

Now I don’t think most people take the time to look at data like those I presented above. However, they do notice desperation when they see it. When the media take great pains to find ways to blame everything on climate change, it is natural for most rational people to start questioning whether or not it is causing anything.

June 30, 2019

Soft Tissue Showdown

Soft tissue structures in a dinosaur bone that the authors interpret as biofilms left by modern bacteria (image from study being discussed)

Since Dr. Mary Schweitzer shocked the paleontological community with her discovery of what appears to be soft tissue in a dinosaur fossil, scientists rushed to find more examples of such soft tissue in fossils that are thought to be many millions of years old. They were apparently successful (see here, here, here, here, and here, and here).

Reactions to these finds follow one of three schools of thought. Some in the scientific community (like myself) beleive that the soft tissue is from the creatures that made the fossils and is therefore evidence that the fossils are not millions of years old, since there is no plausible mechanism by which soft tissue can stay soft that long. Some believe that the soft tissue is from the creatures that made the fossils and are seeking a means by which it could stay soft for millions of years. So far, those attempts have not been successful (see here, here, and here). The rest accept the seemingly obvious fact that soft tissue cannot possibly stay soft for millions of years and therefore argue that the soft tissue that has been found cannot be from the creatures that made the fossils. The results of a recent study at least partially support the view of those in the third camp.

The authors excavated dinosaur bones along with the surrounding rock and took pains to make the excavation as sterile as possible, using heat and chemicals to remove any living organisms from the materials being collected. The fossils ended up coming from a Centrosaurus, which is similar to a Triceratops. They then examined both the bones and the surrounding rock, looking for organic substances. Not surprisingly, they found a lot.

Interestingly, there was a lot more organic substance in the bones than in the rocks, and the chemical nature of the organic substance found in each source was different. So there is something special about the organic materials found in fossils. However, the authors specifically tried to detect collagen, a protein that has been found in many other dinosaur bones and is common in animals. They found none.

They also looked for DNA and found it both in the surounding rock and inside the bone. However, the concentration of DNA was significantly higher in the bone, indicating once again that there was something special about the inside of the bone. They looked for and found a gene (16s rRNA) that is in bacterial DNA. It was both in the surrounding rock and in the bone, but once again, there was a difference in the actual sequence of the gene between the DNA found in each source.

They also did carbon-14 dating on the organic material. They found more carbon-14 than expected, since there shouldn’t be any carbon-14 in a sample that is millions of years old and free from contamination. Of course, they interpreted this as evidence that the organic material is mostly not from the bone itself, since they are assuming the bone is millions of years old. Interestingly enough, their samples tested similar to the dinosaur bones that were excavated by creationists. However, the creationist samples were dated using a chemical, bioapatite, that is specifically related to bone and is not produced by bacteria.

The authors also noted that when they examined the organic material with fluorescence microscopy, they found “aggregates” that looked a bit like cells and fibers. Two of their images are shown in the picture above. Although it was never explicitly stated, the implication is that the studies which have produced microscopic images of cell-like and fiber-like structures might be misinterpreting what they found. Those structures might be biofilms left by modern bacteria.

In the end, the authors propose that fossil bones attract a specific community of bacteria that are different from the bacteria that live in the surrounding rock. They state:

The analyses presented here are consistent with the idea that far from being biologically ‘dead,’ fossil bone supports a diverse, active, and specialized microbial community. Given this, it is necessary to rule out the hypothesis of subsurface contamination before concluding that fossils preserve geochemically unstable endogenous organics, like proteins.

This means that when scientists look for soft tissue in dinosaur bones, they need to rule out contamination by bacteria (and fungi) before thinking that they have tissues from the animal that left the fossil behind. The authors rightly do not say that previous claims of soft dinosaur tisue are wrong, but they give reasons as to why they might be wrong. In the end, it is clear that they are very skeptical of the claims.

I am willing to believe that some soft-tissue-in-dinosaur-fossil claims might be the result of contamination, but I find it hard to believe that they all are. In the cases where the cells in the soft tissue have been imaged, they look nothing like bacterial cells or the biofilms that bacteria leave behind. Instead, they look like red blood cells and bone cells (see here, here, and here). It is hard to imagine how those cells could be the result of contamination.

However, it seems very clear that in this dinosaur fossil, there is no soft dinosaur tissue. Hopefully, other studies like this will be done. If there really is soft dinosaur tissue in some dinosaur fossils, this kind of study should also eventually find it. If not, perhaps all the soft tissue claims really are wrong.

I predict that if several more studies like this one are done, at least one of them will find soft tissue that can be confidently identified as belonging to the animal that made the fossil.

June 24, 2019

Science and Creativity, Part 2

Click for credit

In my previous post, I shared a very creative lab report that I received from a physics student in one of my online physics courses. In this one, I want to share something from another very creative student. In order for you to appreciate it, however, a bit of background is necessary.

In my online courses, students take tests online while being supervised by their parents. The parent has a passcode for each test, and when the student is ready to take the test, the parent inputs the passcode into a website. This opens up the test for the student to take. Some of the test questions are multiple-choice (I call them “multiple-guess”), some are true/false, and some are short answer. That, however, is not enough to fully assess a student’s knowledge when it comes to science, so I also have a few “essay” questions on the tests. In physics and chemistry, they are usually long, involved problems that the student must work out.

In order to properly assess the student’s work, I must see all the steps that the student takes to come up with the answer. If the student were taking the test on paper, that would be fairly easy. The student could just write out the equations being used, show how the variables were plugged it, and go through whatever algebra is necessary. However, on a website, that can be tricky. The program we use has an editor that allows the student to write equations, but it is bulky and cumbersome. Student can do their work on paper and then upload an image of the paper, but that is also bulky and cumbersome. As I result, I simply tell students to explain the steps they took to get to the answer, and I allow them to use any method they think bests accomplishes this goal. Some use the equation editor, some use paper and upload an image, some give equations using just text, and some give me a narrative of what they did.

Eden Cook is an example of the latter. She gives me a narrative of her work, usually in the form of an amusing story. There are typically characters in her stories, and they each have their own personality, which adds to the humor. One of those characters is “Newton.” Well, in one question where she had to determine the electric field produced by two stationary charges (represented by one one black dot and one blue dot), she decided to forgo the story and write a poem. I.T. W.A.S. E.P.I.C.

[image error]

(The star is a footnote where she shows the vector addition, and her answer was correct.)

Jay L. Wile's Blog

- Jay L. Wile's profile

- 31 followers