Bliss Bennet's Blog, page 9

November 26, 2015

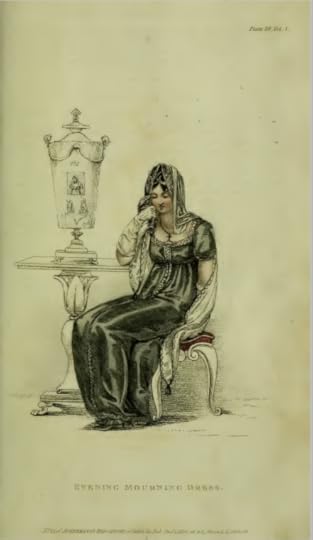

Ackermanns Fashion Prints December 1810

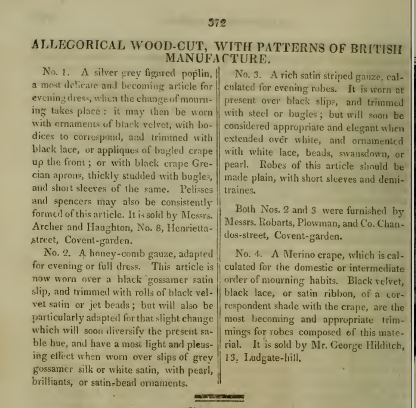

The death of England’s Princess Amelia, youngest daughter of King George III and Queen Charlotte, in November 1810 led many a lady’s magazine to focus on mourning clothing in their prints. Ackermann’s Repository was no exception. December’s plates feature mourning gowns for both the morning and the evening (although, handily, once mourning was over, one could simply exchange the black under-dress of the evening gown for a white or silver-grey one, to “form a most pleasing habit.”)

The death of England’s Princess Amelia, youngest daughter of King George III and Queen Charlotte, in November 1810 led many a lady’s magazine to focus on mourning clothing in their prints. Ackermann’s Repository was no exception. December’s plates feature mourning gowns for both the morning and the evening (although, handily, once mourning was over, one could simply exchange the black under-dress of the evening gown for a white or silver-grey one, to “form a most pleasing habit.”)

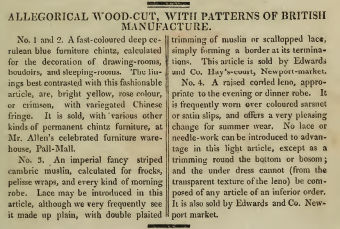

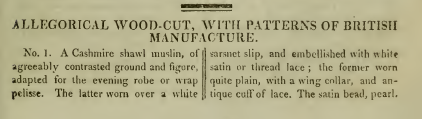

The “Patterns of British Manufacture” in the back of December’s issue also focus on mourning dress, with fabric samples appropriate for full and “second” mourning.

November 25, 2015

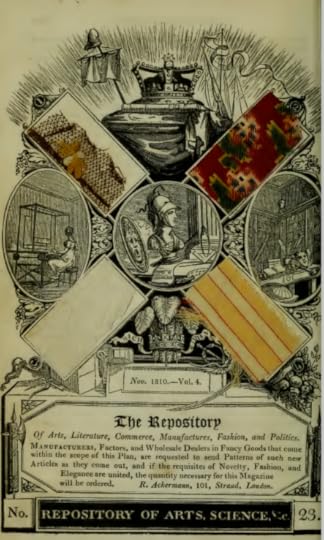

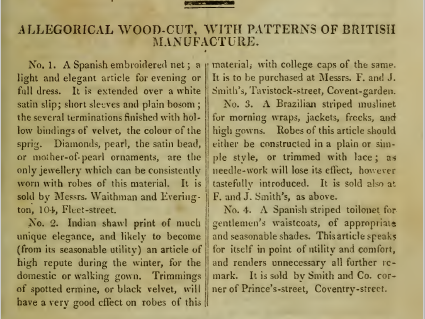

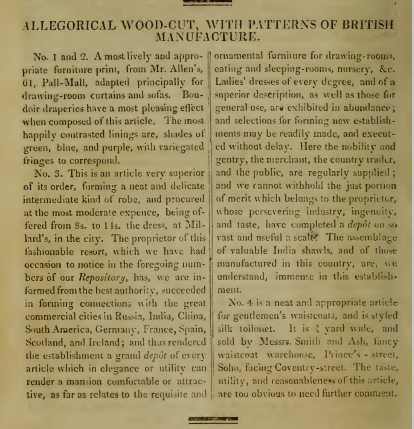

Ackermans Fashion Plates November 1810

Arbiter Elegantiarum returns this month to wax fearful about the “influence that the love of dress has upon the inhabitants of country towns and villages.” AE urges “landowners, and proprietors of estates, to check as much as possible” the “ruinous propensity” of the less-than-genteel to mimic the fashions of their betters.

Interesting to consider whether many Regency-era landlords in fact had enough sway over their tenants and other employees to dictate what they could and could not wear. And whether the wives of said landowners played any part in such regulation. Can you imagine going off to police your “dependents” while wearing that “French tippet of leopard silk shag” that the lady in Plate #30 is sporting?

In earlier days, AE notes, it was easy to tell who was a gentleman: “one descended from three degrees of gentry, both on the mother’s and father’s side.” In contrast, during AE’s times, a gentleman is “any one who possesses a certain sum of money in the funds, though his father be a scavenger or a chimney-sweeper.” AE shares the fears of many a genteel person of the period, fears that the once strict boundary lines between the classes has become frighteningly permeable.

I wish we had more of the sample of #1 fabric, a “Spanish embroidered net”; it appears that part of the swatch has been ripped away, alas. Brown and rose are one of my favorite color combinations. Not too enamored of the Indian shawl print (swatch #2); perhaps it would be more attractive in a larger sample?

November 18, 2015

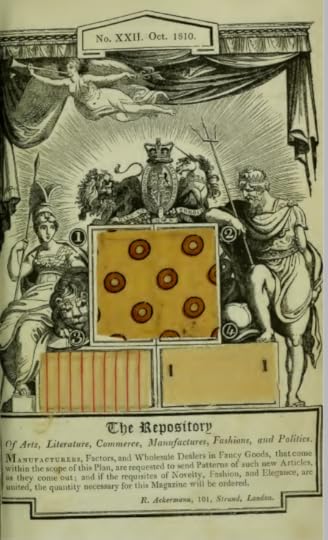

Ackermanns Fashion Plates October 1810

October seems an odd time for frolicking on the English shore, but one of this month’s fashion plates is labeled “Promenade, or Sea-Beach Costume.” The other is equally unusual: not just a “Morning Dress,” but a “Morning Dress, or Costume a la Devotion,” which I’m taking to mean “at prayers” or “at devotions,” given the background portrayed in the print. A young Regency woman of fashion can gossip with her friends, but she should also spend time communing with the Lord.

Polka dots? Big, yellow polka dots with bright red centers? On your drawing room curtains and sofa? Hard to imagine this “most lively and appropriate furniture print” on anything from the Regency era, doesn’t it?

November 11, 2015

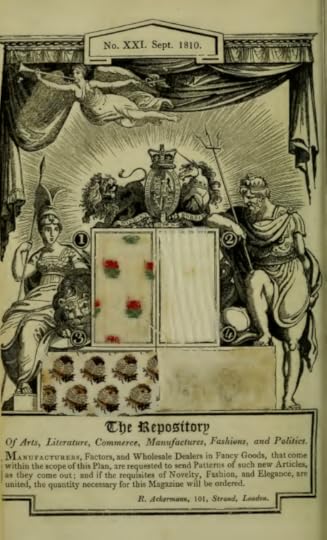

Ackermanns Fashion Plates September 1810

No commentary from Arbiter Elegantiarum in September, just descriptions of one Full Dress gown and two Promenade Costumes. I’m struck by the lace-up fronts of two of the dresses (described as a”stomacher front” in the first plate, and “bosom of the robe laced with white silk cord”); this style isn’t seen very often in Regency-set films. Perhaps because it is associated more with earlier periods’ styles?

Unless I’m misreading, the “neck-chain and cross” around the first lady’s neck is reported as being of “dead gold filigree.” Anyone have any idea of what “dead gold” is?

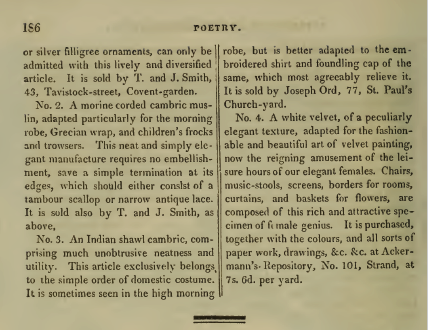

I’m taken by the unusual shapes on the “Indian shawl cambric” of this month’s fabric sample #3, and can imagine it making a lovely dress. Alas, Ackermann’s says “this article exclusively belongs to the simple order of domestic costume. It is sometimes seen in the high morning robe, but is better adapted to the embroidered shirt and foundling cap of the same, which most agreeably relieve it.” I was having a hard time picturing this fabric as a baby’s cap; good thing I had C. Willett Cunnington’s English Women’s Clothing in the Nineteenth Century to remind me that adult women sometimes wore “foundling caps” as part of morning dress (see illustration below).

Foundling cap

November 4, 2015

Regency Embossed Ornaments?

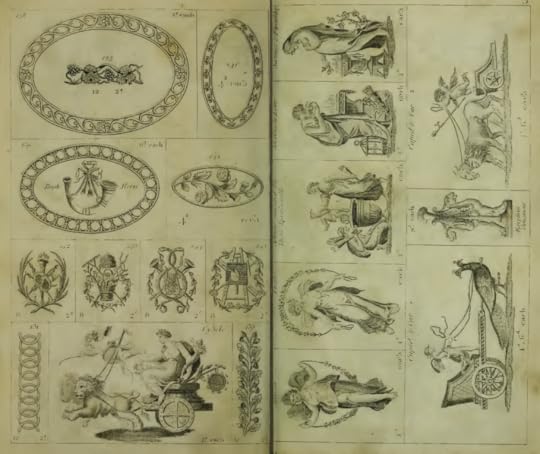

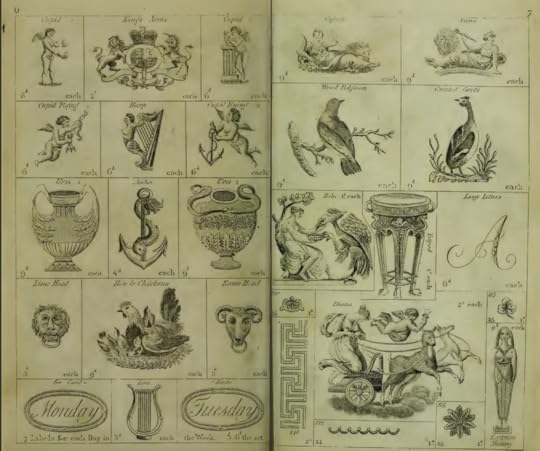

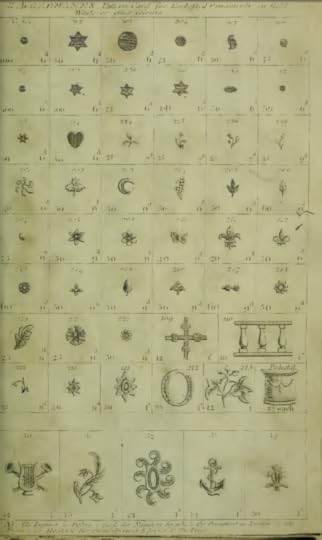

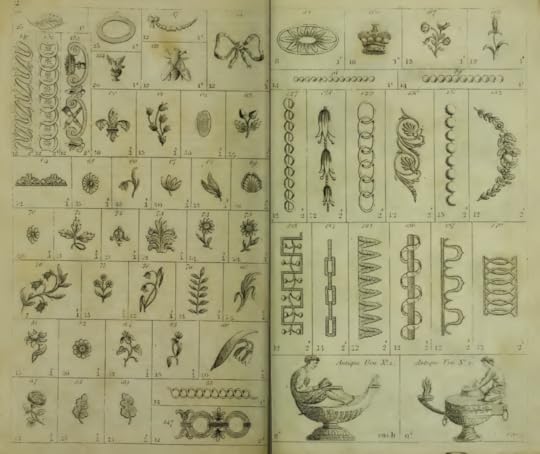

While putting together my Ackermann’s fashion plate posts last month, I came across several pages of drawings in the June 1810 edition of the journal. I thought they might be designs for period type ornaments, something that I’m always on the lookout for, so I screen-shot them and then set them aside for my files.

Today I had a chance to look at the images more closely, and discovered that my initial guess about the purpose of the drawings was wrong. The original scanning of the volume isn’t that great, so it was a bit difficult to make out the heading text, but with some careful squinting, I finally managed to suss out this description: “Pattern Cards for Embossed Ornaments in Gold, White or Other Colours.”

Today I had a chance to look at the images more closely, and discovered that my initial guess about the purpose of the drawings was wrong. The original scanning of the volume isn’t that great, so it was a bit difficult to make out the heading text, but with some careful squinting, I finally managed to suss out this description: “Pattern Cards for Embossed Ornaments in Gold, White or Other Colours.”

What the heck are “Embossed Ornaments,” I wondered, and what in the world did stylish Regency readers use them for? Jewelry? Trim for gowns or coats? A bit more research was clearly required.

Thank heavens for Google Books. A search using “Ackermann’s pattern card embossed ornaments” lead me to Maurice Rickards’s fascinating Encyclopedia of Ephemera: A Guide to the Fragmentary Documents of Everyday Life for the Collector, Curator and Historian (Routledge, 2000). This 550-entry alphabetically organized encyclopedia focuses on manuscript and printed ephemera in English dating from the 1500s to the present day. Information about “embossed ornaments” shows up in the Encyclopedia‘s entry for “Tinsel print” (see page 383), not a connection I would have made on my own.

A tinsel print, according to Rickards, is “a hand-coloured print embossed with metallic foil and other materials.” Taking up the idea from the 17th-century French vogue of decorating prints with additional material, early 19th century London toy theatre creators used tinsel to decorate their cut-out figures, “a deluxe version of their ‘tuppence coloured’ products.” Rickards reports that in addition to toy theatre makers, “many toy shops and stationers also sold ready-made addenda—breastplates, plumes, helmets, swords, jeweled necklets, etc., cut out and requiring only to be glued on to figures.” He goes on to list Ackermann and H. J. Webb as purveyors of tinsel-print materials, specifically referencing the Ackermann’s pattern cards “for Embossed Ornaments in Gold, White or Other Colors” which I came across in the June 1810 issue.

These illustrations, though, don’t seem intended for ornamenting toy theatre figures. Only after figuring this out did I realize that the article that followed the Pattern Card illustrations, “Observations on Fancy-Work, As Affording An Agreeable Occupation for Ladies,” was connected to them. The article mentions ladies who “have been led by genius or example to acquire the art of painting,” and who use said art to decorate “vases, fire-screens, hand-screens, flower stands, boxes, and other articles (XVIII.iii, page 397). But even “those females who have not made themselves mistresses of the art of managing the pencil” can still participate in such decorative embellishment: by using embossed ornaments, conveniently available at Ackermann’s!

These illustrations, though, don’t seem intended for ornamenting toy theatre figures. Only after figuring this out did I realize that the article that followed the Pattern Card illustrations, “Observations on Fancy-Work, As Affording An Agreeable Occupation for Ladies,” was connected to them. The article mentions ladies who “have been led by genius or example to acquire the art of painting,” and who use said art to decorate “vases, fire-screens, hand-screens, flower stands, boxes, and other articles (XVIII.iii, page 397). But even “those females who have not made themselves mistresses of the art of managing the pencil” can still participate in such decorative embellishment: by using embossed ornaments, conveniently available at Ackermann’s!

I wonder: would Mr. Darcy lump embossing in with the other “common extent of accomplishments” such as painting tables, and covering screens, and netting purses? Or would it not even rate that high?

October 28, 2015

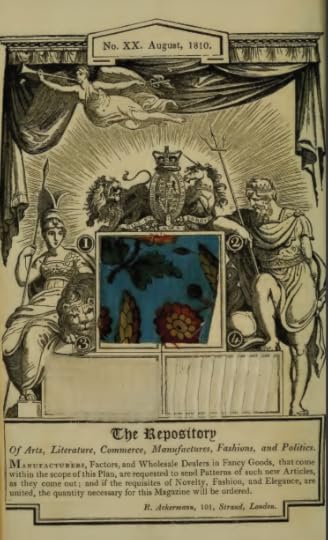

Ackermanns Fashion Plates August 1810

Fascinating General Observations in this month’s fashion plate commentary by Arbiter Elegantiarum, condemning any female fashion that bears a resemblance to the dress of men:

“However ambitious of conquest the fair may be, they cannot expect to attain their object by inspiriting beholders with terror. Modesty and loveliness are their legitimate weapons, retreat and ambuscade their chief military manoeuvres. . . . ”

But AE goes on to enforce gender codes beyond simple fashion:

“I know there is a race of Amazons in the present age, the Lady Diana Spankers of the present day, to whom all this would appear the height of absurdity. To rival, not to captivate, men, is the aim of these heroines; but they will, I am sure, never find admirers or imitators amongst those who are distinguished for sensibility or intelligence.”

Lady Diana Spanker is a character in the children’s story “Mademoiselle Panache,” by Maria Edgeworth. Edgeworth describes her as a “dashing, rich, extravagant, fashionable widow” whom her main character, a coquette, uses as a foil to make herself look more appealing. Lady Di’s “masculine intrepidity and disgusting coarseness” would likely be familiar to readers, as Edgeworth’s Moral Tales were hugely popular in the period.

Clothing for the beach is certainly different now than it was in the Regency, isn’t it?

August’s fabric samples include another colorful chintz for furniture, and a “leno,” which Fairchild’s Dictionary of Textiles tells us is “a fabric made with a leno weave” ; “leno weaving” is “a weaving process in which warp yarns are arranged in pairs,” giving an strength to open weave fabrics. Here’s a picture of a modern weaver’s leno wall hanging:

October 21, 2015

Ackermanns Fashion Plates July 1810

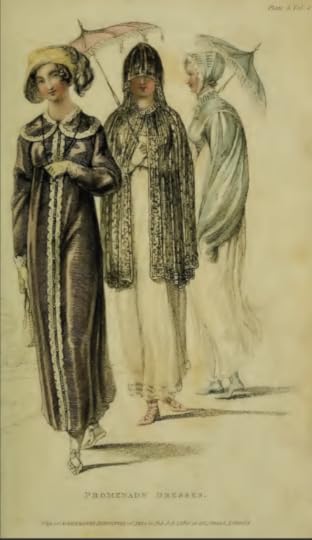

Volume 4 of Ackermanns opens with a sumptuous ball dress, one that sports a rather short hem—so that we could see those fabulous spotted shoes? I wonder how the “pink foil” spots on the white satin of the shoes was stuck on? And does anyone have any idea what the heck it is that the woman is leaning on??

The three ladies purportedly taking the air in Kensington Gardens look ready for a cloudy, showery day, rather than for a hot summer stroll. The post uses the word “ridicule” rather than the more familiar (at least to us) “reticule.” I wonder which word was more popular at the time?

I have no idea what an unella veil is; couldn’t find a listing in Fairchild’s Dictionary of Textiles, and a Google search just turns up a character on Game of Thrones.

In the general observations, Arbiter Elegantarium bemoans the introduction of “stiff stays and long waists,” particularly among “the middle and lower classes of society”:

Comments on this month’s fabric samples include a long footnote about British muslin being falsely marketed as India muslin, and puffs for the new “establishing of the warehouse by Mr. Millard, in Cheapside” “as the India goods there are sold direct from the India warehouses.” Wouldn’t want the India Company to lose their revenue, would we, fashionable ladies?

Would you wear “seaweed muslin” (see sample 4)?

Vol. IV, no. XXI, page 52

October 14, 2015

Ackermanns Fashion Plates June 1810

And I thought last month’s plates were cosmopolitan! But June’s first plate, a walking or carriage costume, features “a round high robe of Frenc cambric, with Armenian collar, “an Egyptian mantle of lilac shot sarsnet, trimmed with broad Spanish binding,” “a Parisian bonnet” with “French net,” as well as a “Chinese parasol.” Young women in the Regency may not have been able to go on the Grand Tour, but their clothing certainly gave the impression that they had!

Again we have a “child” outfit, not a “boy’s” or “girl’s” outfit, demonstrating once again how interchangeable clothing was for the youngest set.

Arbiter Elegantarium quotes Oliver Goldsmith’s Essay Number XV (full link here) to bemoan the current state of English fashion: “Foreigners observe that there are no ladies in the world more beautiful or more ill-dressed, than those of England.” Goldsmith held French fashions in far higher esteem than English ones, an opinion obviously shared by AE, a prime example of the longstanding English cultural inferiority complex when it comes to anything French.

This month’s fabric samples include a lovely “permanent lilac chintz furniture, never before produced in this country.” It does seem quite colorful compared to many of the other chintzes featured in earlier Ackermann’s plates. Sample #2, a Persian lace muslin, is particularly becoming; wish the image were better at capturing its detail…

October 7, 2015

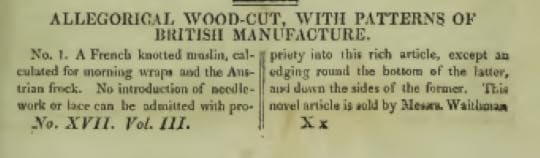

Ackermanns Fashion Plates May 1810

This month’s theme is cosmopolitanism. The two fashion plates, both of promenade costumes, feature fashions from multiple countries around the globe. The first plate, labeled “In the Egyptian Style,” looks like something a traveler to the Middle East might wear, don’t you think? Visually, the second is far less obviously geographically situated, but its description features a “high French ruff,” a “cassoc coat”, an “Austrian tippet,” and an “Arcadian hat.” Though the hat’s adjective in all likelihood refers less to the headgear’s provenance and more to its overall rural or rustic feel . . .

October 2, 2015

A cover for A MAN WITHOUT A MISTRESS

So excited to share the cover for the second book in The Penningtons series, A Man without a Mistress: