Bliss Bennet's Blog, page 3

February 7, 2018

Ackermann’s Fashion Plates May 1815

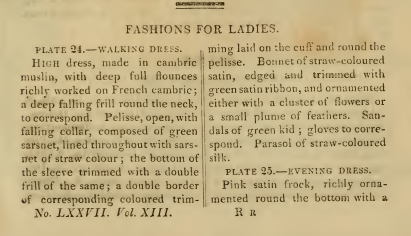

Frills are the name of the game in May 1815’s fashion plates, with both the walking dress of Plate 24 and the Evening dress of plate 25 trimmed on bottom an around the neck with white flounces. Though in the print they appear to my eye to be made of lace, the walking dress’s deep full flounces above the hem and neck are described as being made of “French cambric” “richly worked.” Perhaps that fabric was embroidered using one of the needlework designs featured in one of Ackermann’s earlier issues?

Vol XIII, no. lxxvii, plate 24

The rich ornament on the hem of Plate 25’s Evening Dress is described as “garnet yewer.” The word “yewer” does not appear in Fairchild’s Dictionary of Textiles, and as the only definitions in the Oxford English Dictionary refer to water pitchers and udders (!), I’m wondering if this might be a typo. Especially as the trim in question is decidedly not red, but white, in the fashion plate. But I’m having a hard time figuring out what might be the correct wording. Any guesses?

Vol. XIII, no. lxxvii, plate 25

Both prints give us a clear look at each lady’s footwear, and how those dainty slippers were kept on her feet. The walking dress features “sandals of green kid,” with 3 bands of ribbon lying flat across the top of the foot before crossing round the ankle and tying in a tiny bow. The white kid slippers look to have only the 3 bands of ribbon—I wonder, in the days before elastic was invented, how well such ribbons would have held a slipper on the foot?

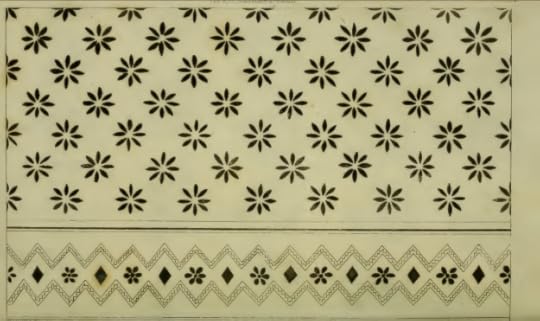

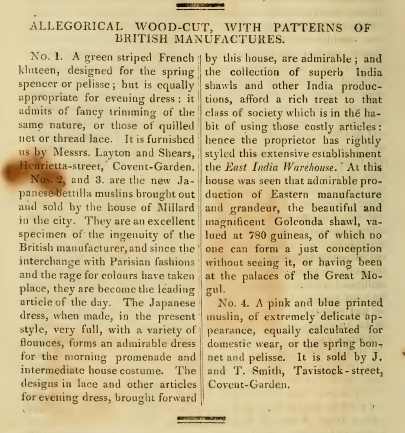

This month’s magazine features fabric samples for ladies’ dresses. Sample one introduces another word with which I am not familiar: “kluteen.” Again, I could find no definition for this word in Fairchild’s nor in the OED; perhaps the typesetter for this edition of the magazine was unusually careless?

The “Japanese betilla muslins” of samples #2 & 3 were a little easier to identify; Fairchild’s lists “beteela,” “bethilles,” and “betilles,” all types of Indian muslin. Why these samples are deemed “Japanese” I’m not quite sure (especially as the copy tells us they were manufactured in Britain). But the description assures readers that “since the interchange with Parisian fashions and the rage for colors have taken place, they are becoming the leading article of the day.” I can picture a morning dress being made from one of them, can’t you? But I think I’d like one more that was made from sample #4, the “pink and blue printed muslin, of extremely delicate appearance.” Perhaps I’ll have to send one of my characters off to J. and T. Smith’s in Tavistock Street in a future book?

SaveSave

SaveSave

SaveSave

January 31, 2018

Ackermann’s Fashion Plates April 1815

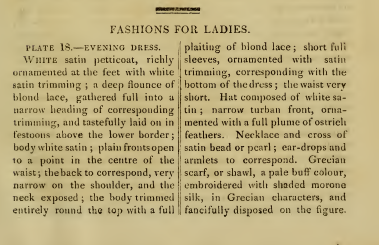

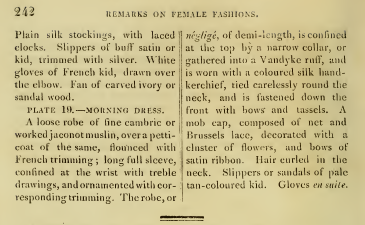

April 1815 returns us to dresses of white, with both a white satin evening gown and a white muslin morning robe. In fact, the most colorful item in either print is the yellow and green parrot sitting on the finger of the lady in the morning gown; one might be forgiven for mistaking the green ribbons adorning the lady’s mob cap for feathers plucked from her favorite pet! Her white robe of demi-length is described as a négligé (another fashionable French import due to the cessation of French/English hostilities?), and is flounced with “French trimming.” The colored silk handkerchief tied “carelessly” around her neck gives the outfit a hint of informality uncommon in Regency-era fashion plates.

Vol. XIII, no. 76, plate 19

This morning dress’s négligé hides the bodice of the petticoat below, but the bodice of the evening gown dips just as low in front as in previous fashion plates featured in 1816. The white satin gown features a double hem border, the lower of white satin trimming, the upper of blond lace gathered “into a narrow heading of corresponding trimming, and tastefully laid on in festoons above the lower.” Plaited blond lace also trims the deep-V neckline, which is echoed on the dress’s back.

Vol. XIII, no. 76, plate 18

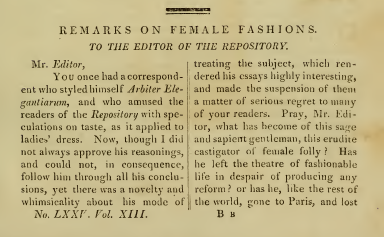

In response to last month’s letter to the editor, Arbiter Elegantiarum makes a cameo appearance, to bemoan, like the earlier writer, the current state of English female fashion. Apeing French styles, as AE and his predecessor accuse Englishwomen of doing, is not only a mistake in taste; it is also, he implies, a sign of their lack of patriotism: “Where can be the good sense of those who will blindly and stupidly adopt the dress of a people whose manners we ought to execrate, and whose feelings we abhor?” AE once believed that “women were reasonable beings, and that English women were superior beings,” but now despairs as he watches the speed with which the “mania” for foreign fashions has swept his homeland. The only way he can possibly imagine influencing such empty-headed creatures is by appealing to their “passion for admiration”: all Englishmen feel “a disgust bordering on horror” at their countrywomen’s attempts to dress in a manner that renders them “all that is ugly, monstrous, and deformed.” Ah, the personal (or the fashionable) as political…

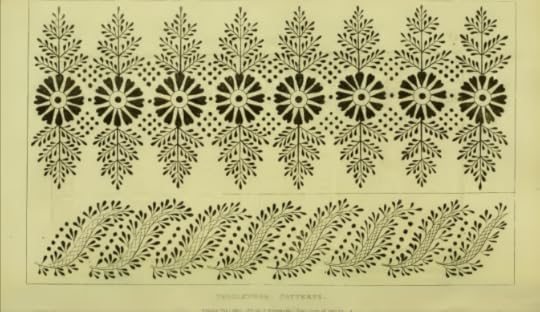

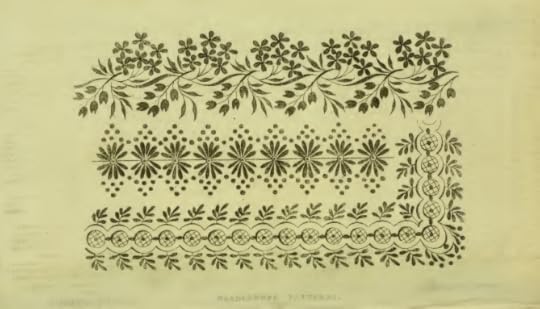

Regency women uninterested in being fashion-policed might instead sit down with this month’s Needlework patterns, two wider borders with myriad tiny leaves to occupy one’s hand and one’s mind.

January 24, 2018

Ackermann’s Fashion Plates March 1815

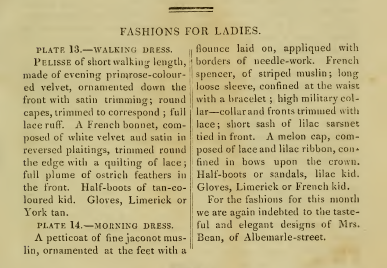

Daytime wear is the subject of March 1815’s fashion plates, which feature one walking dress and one morning dress. The walking dress (plate 13), departs from the previous two months’ focus on pale colors; our model here is decked out in a lush purple velvet pelisse, described as “evening-primiose-coloured.” Curled satin trim runs along each side of the front edge of the pelisse; tiny capes, “trimmed to correspond,” just cover each of the lady’s shoulders. An immense bonnet, styled “French,” looms over this wearer’s head, with an equally impressive ostrich feather topping it. I don’t imagine you would be hard to spot in a crowd if you wore that hat!

Vol. XIII, no. 75, plate 13

Plate 14’s morning dress is primarily white, but includes small touches of lilac to match plate 13’s evening primrose hues. A white petticoat trimmed with borders of needle-work is paired with a striped white spencer, tied under the bosom with “a bracelet” of unspecified material. It might simply be ribbon to match that adorning the wearer’s “melon cap,” coordinated to match the lilac kid half-boots. As in the past two months’ plates, this gown’s border, too, is a deep one.

Vol. XIII, no. 75, plate 14

In addition to the fashion plates, this month’s Ackermann’s has the added bonus of a letter to the editor, with “Remarks on Female Fashions.” The writer mourns the disappearance from the pages of Ackermanns of Arbiter Elegantarium, who in earlier editions of the magazine offered fashion advice (and remonstrance) to the women of England. He also mourns the current trend for all things French (“that vortex of frippery, buffoonery, and extravagance”), which, due to the cessation of hostilities with France, threaten the “contamination” of English “good taste.” The writer has a special abhorrence for overly large hats (of the type featured in plate 13), and the move away from the simpler lines of dresses of the earlier Regency period, ones that more closely mirrored “the best ages of antiquity.” So amusing to read these deprecations against fashion, especially when placed right next to the plates that extol such dress!

The magazine ends with several needle-work patterns for narrow borders or edgings. Perhaps some were used to make the embroidered embellishments on the flounce of the morning dress in plate 14?

January 17, 2018

Ackermann’s Fashion Plates February 1815

February 1815’s plates feature one dress for daytime wear, and one for the evening. Like January 1815’s gowns, this month’s Evening Dress (plate 9) features a pale-colored gown with a deep border, although this border so quite elaborately trimmed, with “blond lace and pink, or primrose-colored ribband, festooned and decorated with roses,” you can barely tell there’s a border under there at all. I’m also struck by how small the bodice of this gown is; either its wearer is extremely small-bosomed, or low-cut bodices are becoming ever-more in fashion. The pedestal upon which the model leans is a nod to the increasing trend towards Grecian forms in furniture. The “French scarf, fancifully disposed on the figure,” almost gives this model the air of a royal.

Vol. XIII, no. lxxiv, plate 9

The morning dress of plate 8 is far more subdued in color, although almost as elaborately trimmed as its companion evening gown. White cotton ball tassels trim the front of the white round gown from bodice to hem; needle-work or French embroidery confines the hands at the end of the long sleeves; a flounce of lace or needle-work sweeps the floor at dress’s hem; and blond lace adorns the dress’s falling collar and cape. The mobcap’s ribbon and the shoes’ kid dab just a touch of color (light blue) on the ensemble. But this dress, like its evening companion, also features quite a plunging neckline, although if one’s eyes are drawn to it here, one also encounters a satin bead or pearl cross as well as a tempting décolletage…

Vol. XIII, no. lxxiv, plate 8

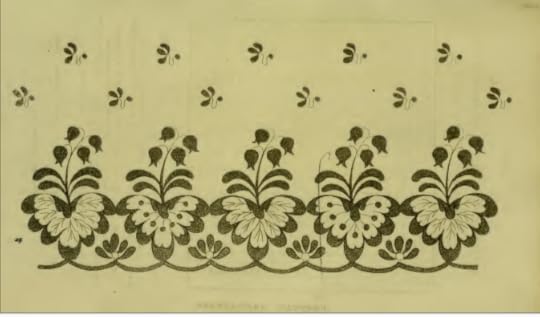

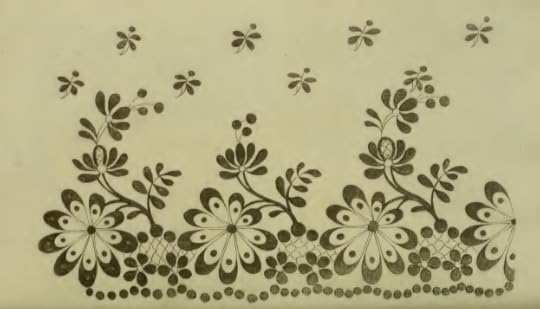

This month’s edition concludes with a needle-work pattern, one that though it features flora, reminds me of insects with its butterfly-like leaves and its small flying seedpods. Although one would never see seeds in real life descending from the skies in such an even pattern…

January 10, 2018

Ackermann’s Fashion Plates January 1815

My planned short break from Regency fashion plate blogging extended into a month and a half-long hiatus, due to illness, holiday planning and travel, snowstorms, and a cold snap with several days of no heat in my house. But now that 2018 is underway, I’m determined to get back on a regular blogging schedule, bringing you the fashion plates and descriptions from Ackermann’s Repository from 1815 and 1816.

Vol. XIII, no. 73, plate 3: Evening Dress

Ackermanns opens its 1815 year with two pale-colored dresses: a full dress in celestial blue, and an evening or opera dress in light pink. Both dresses feature wide bottom borders—a new trend for 1815? Both borders are white, the celestial blue dress’s embroidered “with shaded blue silks and chenille” in a pattern of circles or wreaths, the light pink’s plain, but edged on top and bottom with tufts of lace. My fingers itch to reach out and touch these two different embellishments, don’t yours?

Vol. XIII, no. 73, plate 4: Evening Dress/Opera Dress

I’m intrigued by the accessories featured in these prints. Nothing in the copy describes what it is that the young lady in plate 3 is holding. Is it something like a modern-day compact, which would hold a small mirror and face powder or blush/rouge? Or is it more likely to be pair of linked painted miniatures, perhaps of the owner herself and her beloved? Or of loved ones now departed?

The copy for plate 4 does describe its unusual short cape, as a “shell lace tippet.” I wonder if the tippet was knit, crocheted, or tatted? I can’t recall seeing anything like it in any fashion plate of the period I’ve seen before.

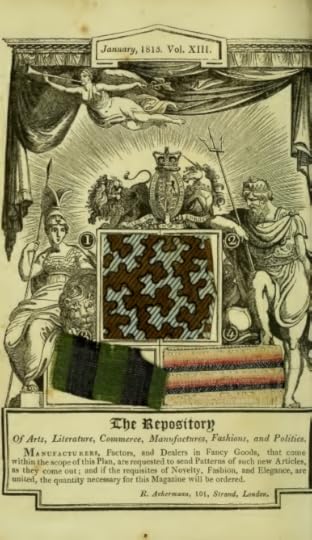

The new year brings a return of the fabric sample page at the issue’s end. Only three samples instead of four, and only two intended for dresses. Interestingly, where the fashion plates both feature light colors, all these fabric samples are on the darker end of the color scale.

I have to say that I don’t find the first sample, No. 1/2, intended for furniture upholstery, all that appealing, despite the description’s terming it “choice.” Sample 3, which is recommended for morning or domestic wear, is a more appealing black and green striped “tabinet,” a fabric that Fairchild’s Dictionary of Textiles reports is “a poplin produced chiefly in Ireland, made with silk warp and wool filling and given a moiré finish” or, more simply a “thin taffeta with a moiré finish” (558). Sample 4 is also a blend, this time of cotton and silk “toilinette,” which Fairchild’s explains is “a plain, figured, or printed fabric made of silk and cotton warp with a woolen filling” which was popular during the period for women’s dresses and men’s vests.

Can you say “tabinet and toilinette” ten times fast?

November 15, 2017

Ackermann’s Fashion Plates December 1814

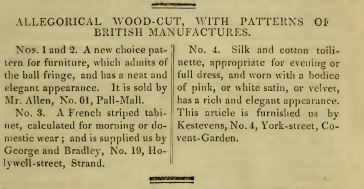

The last issue of Ackermann’s Repository for 1814 features an unusual fashion plate: a collection of five different head-dresses! From the simple cottage bonnet (#4) to the elaborate Russian à la mode (a tall, almost stovepipe top, but without the coat-scuttle-like brim of the Oldenburg bonnet), 1814’s Regency lady could find examples of hats for any and all occasions. I’ve never heard of a “melon cap” (#2) before, but I’m rather taken by it, with its puckered satin and what is described as “narrow bead trimming inlet.” I wonder what it looked like from the front?

Vol. XII, no. lxii, plate 29

Hat #1, a “full turban,” can be made from either silver net or “tiffany,” another fabric term with which I was unfamiliar. Fairchild’s Dictionary of Textiles reports that tiffany is “a very thin, fine, semitransparent French silk fabric. Used in France and England during the 17th century for veils.” Perhaps by Regency times, the term had taken on the second or third definition included in Fairchild’s: “A very think plain wave linen fabric with a sized finish” or “A lightweight, sheer muslin; a kind of gauze. Sometimes, it is sized, dyed, and used for making artificial flowers.”

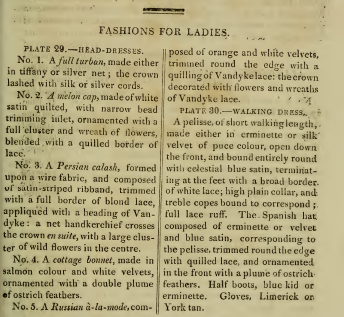

Which bonnet would you choose to step out in to celebrate December’s festivities? If none of the above are to your taste, perhaps you would prefer the “Spanish hat” featured in plate 30 (below), which is paired with a short, walking-length pelisse in puce. I think of puke green when I hear the word “puce,” but here it refers to a dark purple brown or brownish purple color. But even this version of puce has gross-out associations: puce is the French word for “flea,” and the color is said to be the color of what remains after a flea has been crushed.

Vol. XII, no. lxxii, plate 30

For a color with such an unpleasant name, it certainly appears attractive in this plate, especially with the unusual choice to pair it with trim of “celestial blue satin.” And are those triple “copes” meant to echo the Garrick coats, with their three to five caplets or collars, favored by those dashing Regency gentleman noted for their driving skills?

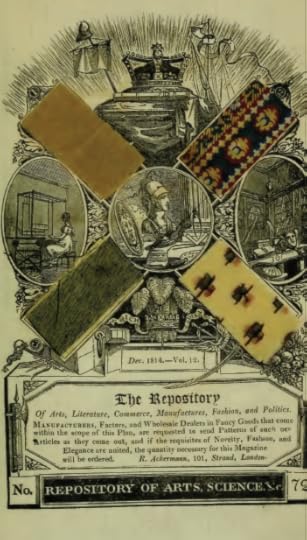

The year’s volume concludes with “Patterns of British Manufactures,” rather than with the needlework patterns that had become far more common in the journal during 1814. Was the expense of cutting out and glueing down these small fabric scraps growing too costly to keep up? Or were manufacturers less interested in displaying their new wares in Ackermann’s pages than when the Repository was new?

Happily, this month’s fabric samples include one of “erminette,” a fabric also used in the Walking Dress of plate 30. Yet another fabric term that sent me scurrying to my dictionary! The long description of the sample states that this fabric is a new invention, created by “Messrs. Fryar of Huddersfield (the patentees of the seal shawl).” This fabric, it is claimed, “combines the warmth of the Vigonia and Angola cloths with the lightness and flexibility of an Indian shawl.” Fairchild’s Dictionary of Textiles, which describes it as “a brown woolen dress fabric,” has the dating a bit off, stating that it was produced in the late 19th century.

Two of the other fabrics are suited for more exotic outfits: the “Persian dress” and the “Albanian costume.” For holiday masquerades? Or just for a touch of the unusual?

SaveSave

October 4, 2017

Ackermann’s Fashion Plates November 1814

Plate 24, Vol. XII, no. lxxi: “Walking Dress”

Both of this month’s gowns feature Vandyke trim (one of lace, one a ruff of unspecified material), which made me curious to learn more about the term. Fairchild’s Dictionary of Textiles defines “van dyke edge” as “a sharp-pointed, scalloped edge in lace, embroidery, or fabric trimmings” (606-07). Like the lady in plate 24, male courtiers throughout 17th century Europe often wore collars or ruffs with sharply pointed edges. But they did not call them “van dykes.” That name comes from the famed 17th century Dutch portraitist Antoon van Dyck, who became the favorite painter of the English King Charles I of England and his wife, Queen Henrietta Maria. Many of those who sat for their portraits wore the pointed collars that would later bear his name—I’m guessing not just because the collar was stylish, but because the sharp pointed edges were more difficult, and thus more costly, to make, indicating to the viewer the wealth of the person in the picture.

It wasn’t until the mid 18th century that the painter’s name begin to be used to describe this earlier 17th century collar style. And only in the early 19th century did “vandyke” come to refer more generally to any notched, deeply indented, or zigzag trim or border.

And as for the beard style—well, that’s a 20th century coinage!

Antoon van Dyck, “Self-Portrait with a Sunflower” (after 1633): No van dyke collar, but he’s definitely sporting the beard!

Plate 26, Vol. XII, no. lxxi

See the Van Dyke lace edging the apron on the fancy half-dress above?

This month’s needlework pattern:

September 27, 2017

Ackermann’s Fashion Plates October 1814

Oddly, since 1814 was known as the “year without a summer” in England, both ladies in October’s fashion plates are wearing sandals with their walking costumes. One hopes that their stockings were thick enough to keep their poor toes warm!

Both dresses also feature handkerchiefs of net used as sashes tied around the bodice, the first “crossed over the bottom and tied in bows behind,” the second “tied in streams and small bows behind.” The handkerchief in Plate 19 almost makes the lady appear to be wearing a bandolier, although nothing else about her appearance evokes a military air. The checks of the handkerchief in Plate 20 give the wearer a countrified air to my eye, although linking checked fabric with the country may be an association that dates to later than the Regency period.

Vol. XII, no. lxx, plate 19

Vol. XII, no. lxx, plate 20

As in one of last month’s plates, this month also seems to feature a color mismatch between plate and description. The dress in plate 20 is described as “evening primrose-coloured,” but looks to be almost the same shade of “celestial blue” as the gown in plate 19.

Plate 19 is described as a “Promenade dress,” while plate 20 is labeled “Walking Dress.” I wonder if Regency readers would have know the differences between the two?

Flowing elliptically-petaled flowers and leaves are featured in this month’s needle-work pattern, along with small dots along the edge. Smaller floating flowers appear above the main flowers, giving the feel of fall seeds floating in the wind.

September 20, 2017

Ackermann’s Fashion Plates September 1814

Is the lady in the first of this month’s fashion plates on holiday by the seaside? Or is she the daughter or wife of a naval officer, watching by the shore, hoping to catch sight of the ship that will carry her beloved family member back home? She looks rather disappointed; has she given up looking through the spyglass at the sailing ship in the distance to gaze instead off into the distances of her own imagination?

The dress she wears, a round robe of lilac or evening primrose sarsnet, features trimming at both hem and neck of a quilling of blond lace edged with chenille (perhaps to keep the lady warm against September’s cool ocean breezes?). A “French hat” of white and lilac satin keeps the winds from ruffling the lady’s face-framing curls.

Vol. XII, no. lxix, plate 14

The second plate features an “Evening Half-Dress,” presumably to be worn for an informal evening at home. Though the copy describes it as “a plain frock,” its long sleeves (inset with lace) and its full flounce of blond lace at the hem and its quilling of lace around the neckline certainly give it a far less than plain feel. The dress fabric is meant to be “striped sarsnet Italian net of peach-blossom colour,” but the pigment must have discolored; the dress looks more purplish black than pink.

The lady’s position highlights her unusual hair style: short full curls in a row several inches higher than the nape, and curls in rows down he sides of the head, with the crown combed flat and straight. Lots of time spent with the curling iron to achieve that look, no doubt.

Vol. Xii, no. lxix, plate 15

It’s been several months, now, since Ackermann’s has included its former fabric samples. I’ll continue to reproduce the needle-work patterns in their place. Thistle flowers leaning in one direction, with leaf fronts tilted in the other, echo the feeling of the wind in the first plate, I think.

SaveSave

September 13, 2017

Ackermann’s Fashion Plates August 1814

It’s a major faux pax today to be caught wearing socks with sandals, but for ladies in the Regency period, one wouldn’t be caught wearing one without the other. In this month’s first fashion plate, we see a rare example of a lady in sandals, these ones made of lilac kid. You can just make out the tiny straps around the lady’s ankles if you look closely at the plate. The lilac scarf sash,”worn in braces,” also gives this summer outfit a casual air. One might think that short sleeves for a summer stroll would be more suited to such an outfit, but long sleeves are called for here, made from sarsnet or muslin. At least the artist has given our lady a parasol to keep off the sun, an accessory not called for in the outfit description.

Vol. XI, no. lxviii, plate 9

Plate 10, an Evening Dress, has, like this month’s Walking Dress, a fairly high hem line, due in part to it being drawn up in festoons above the ankle, almost like a curtain or drapery. The gown is not only decorated about its hem, but also about its bodice, with “a quilling of blond lace on the back and continuing around over the shoulder to give the look of a stomacher. Beads and roses are “fancifully intermixed” on the bodice itself, outlining a central “pearl shell ornament” fixed in the bodice’s center. A shell native to England? Or one brought home from an exotic traveler to warmer shores?

Vol. XI, no. lxviii, plate 10

No fabric samples this month, only an embroidery pattern of flowers and zig-zags that would look lovely as the border of a white summer shawl, don’t you think?