Bliss Bennet's Blog, page 4

September 6, 2017

Ackermann’s Fashion Plates, July 1814

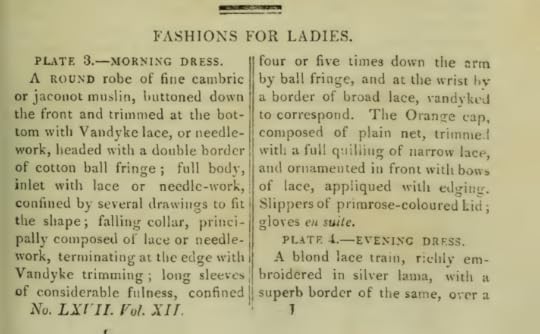

Extravagant trimmings are the order of the month for July 1814’s fashion plates. The morning gown on display features Vandyke lace and cotton ball fringe around its hem, as well as abundant lace and needlework around the collar. The cotton ball fringe is also used to confine the full sleeves in four or five places down the arm. The bodice is described as “full body, inlet lace or needle-work, confined by several drawings to fit the shape”—I’m wondering if “drawings” here refers to “drawing strings,” or whether some other means were used to make the bodice conform to the wearer’s figure.

This month’s evening dress begins with the extravagance of “a blond lace train, richly embroidered in silver lama, with a superb border of the same.” It is a bit difficult to see the details of the lace train in the actual print, so I’ve added a shot of a dress in the V&A Museum c. 1820, which features blonde lace as a trim, below the print. This gown features gold, rather than silver, embroidery, but you can imagine a similar effect. The Ackermann’s gown has the additional feature of “rich silver cord, and large bullion tassels, tied on the side in long loops and streamers”—handy for fidgety fingers no doubt, but all too likely to catch on passing furniture, I fear!

Vol. XII, No. lxvii, plate 4

Blonde lace detail. From the V & A Museum: https://collections.vam.ac.uk/item/O1...

No fabric samples this month, just a detailed needlework pattern (perhaps for the collar adorning this month’s morning gown?)

SaveSave

August 24, 2017

Ackermann’s Fashion Plates June 1814

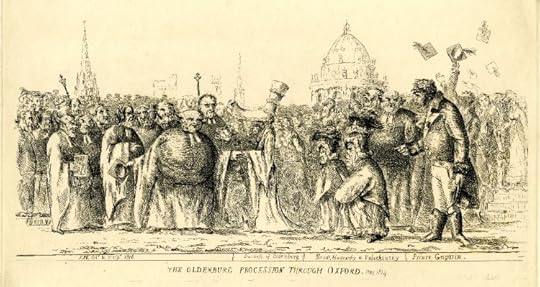

I’m intrigued by the hat in the first of this month’s fashion plates, described as an “Oldenburg bonnet.” I’d never heard of such a bonnet before, and began searching for hints about where the name may have come from. I found mention of Her Imperial Highness, the Grand Duchess of Oldenburg, the mother of the current King of Prussia, Alexander, who visited England in March of 1814, in Edward Seymour’s History of the Wars Resulting from the French Revolution (1815). Seymour reports that the Grand Duchess, “impelled by an insatiable thirst for knowledge, was continually engaged in visiting those objects of curiosity more particularly calculated to enlighten the mind” (Vol. II, page 450). Her visits included two to Oxford University; one of those visits was commemorated in this print, now at the British Museum:

As you can see from the above print, the Duchess wore a quite distinctive hat. The new style bonnet, in vogue for several years after the Grand Duchess’s visit to England, is described in The Habits of Good Society (1863) as “nothing more or less than a coal-scuttle in straw, and turned up around the brim; it was tremendously warm to wear; and caricatures were drawn at the time showing a gentleman’s difficulties in making love to his inamorata, whose face was enclosed in the Oldenburg bonnet” (187).

Ackermann’s version is not quite so extreme as the Duchess’s, but it still keeps the face quite hidden:

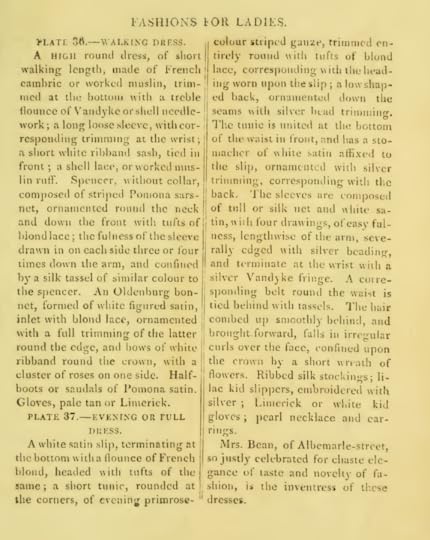

Vol. XI, no. lxvi, plate 36

No such hiding for the lady in Plate 37, “Full or evening dress.” Her gown is cut quite low in the back, and adorned with silver beads down the back seams of the bodice, an ornamentation I’ve never seen before in a Regency-era fashion plate. Have you?

Vol. XI, no. lxvi, Plate 37: Full Dress

I’ve also never seen sleeves decorated in the fashion show here, either. They are described as composed of “tull or silk net and white satin, with four drawings of easy fullness, lengthwise on the arm, severally edged with silver beading, and terminate at the wrist with a silver Vandyke fringe.” I wonder if the length-wise ornamentation made for difficulties in bending one’s elbow?

The lady’s tunic is described as “evening primrose colour,” but looks more like a lavender to my eye. Perhaps the plate’s original color faded or underwent some chemical reaction?

Last month’s fashion for fleur de lis continues in June’s fabric samples: see #2, an “elegant printed marcella for gentleman’s waistcoats, remarkably appropriate to the season, and peculiarly adapted by the fleur de lis by the present circumstances of the times.”

SaveSave

SaveSave

SaveSave

August 16, 2017

Ackermann’s Fashion Plates May 1814

The fleur de lis is the theme of this month’s fashion plates and embroidery patterns, in celebration, no doubt of the abdication of Napoleon and the restoration of the Bourbon monarchy in France the month before. Plate 30’s Opera Dress features fleur de lis embroidery around its bottom; hair is to be “separated on the centre of the forehead by a pearl ornament or fleur de lis.” Plate 31’s Walking Dress also features the French symbol, this time on a shawl: “White silk shawl handkerchief, the corners richly embossed with the fleur de lis.”

Plate 30: Opera Dress

Plate 31: Walking Dress

The “General Notes” encourage the theme: white evening dresses are “constantly attended with the fleur de lis whenever it can be introduced.” Lilac and sea green dresses are occasionally seen, too, all with the French ornament embroidered round the bottom of the dress “without exception.” And white silk shawls and scarves featuring the symbol are also “much in vogue.” No sympathizing with the French revolutionaries for Ackermann‘s readers!

This is one time where having the descriptions alongside the fashion plates themselves really helps us understand more than what the plate shows; I don’t think I would have “seen” any of the ornaments as fleur de lis without their identification in the accompanying description.

The “General Observations” notes several other fashion trends for the early summer of 1814:

• Loose sleeves, “generally carried down to the wrist, some of them continuing to be drawn four and five times down the arm, and each drawing fastened with a small bow of white satin ribband.”

• Bosoms cut less square

• Embroidery less common down the front than about the bottom of the skirt

• Long hair more fashionable than short, especially when worn “very low on the neck behind.”

• “Blücher” hats, no doubt named after the Prussian field marshal who battled Napoleon at the Battle of Nations at Leipzig in 1813

• Silver sprigged or spotted muslins, rather than silk or gossamer, for summer gowns

• Single flounces

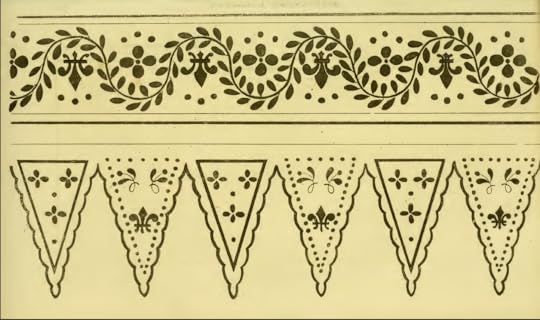

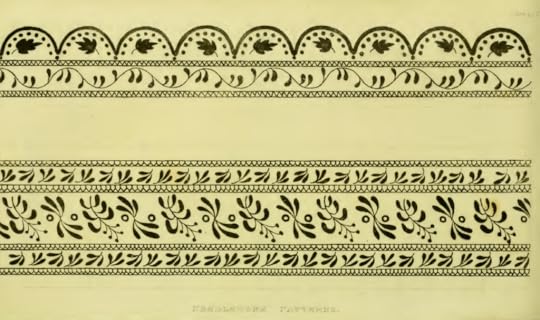

Needlework patterns featuring the fleur de lis

Do you think lilies were the fashionable choice for floral decorations in English ballrooms this month?

SaveSave

July 26, 2017

Ackermann’s Fashion Plates April 1814

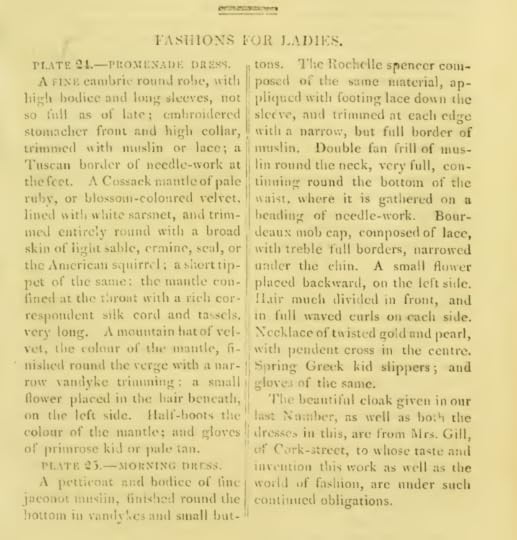

Maggie Prescott, the fictional fashion editor in the film Funny Face, may have declared 1957 the year to “think pink!” but pink clearly appealed to fashionistas long before the mid-20th century. Ackermann’s fashion plates for April of 1814 feature pink in abundance. “Pale ruby” and “blossom-coloured” are the words used to describe the pinks of the mantle, hat, and half-boots of plate 24’s Promenade Dress, but pink they surely are. As is the petite footrest, the flowers on the embroidered screen, and the single blossom in the hair of the lady featured in Plate 25, all of which add a touch of color to the plate’s all-white Morning Dress.

Sleeves in the spring of 1814 are “not so full as of late,” the description of plate 24 notes, although it is difficult to discern just how full said sleeve is, as it is covered by the lady’s mantle. I’ll keep an eye out as I post the rest of 1814’s plates, to see if this trend for less full sleeves continues.

Once again, no fabric samples in this issue, only needlework patterns. Said patterns show a clear shift away from the neoclassical, and toward the more naturalistic. Another trend int he making?

SaveSave

July 19, 2017

Ackermann’s Fashion Plates March 1814

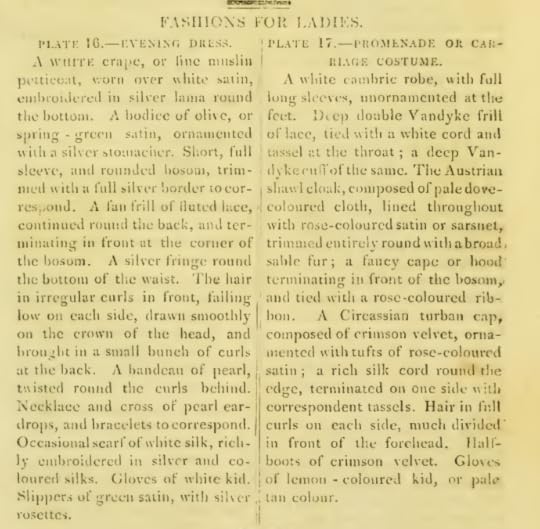

I don’t recall silver being prominently featured in many Ackermann’s fashion plates. But for March 1814’s evening gown, silver is the accent color of choice to enliven a rather plain white dress. A silver stomacher ornaments an olive or spring-green bodice; a full silver border trims the sleeves and neckline; a silver fringe accents the waist; and silver rosettes adorn the slippers. Even the gown itself is “embroidered in silver lama round the bottom” (lama = cloth of gold or silver, originally made in Spain). Only the “fan frill” of lace on the back neckline and the pearls of the necklace and bandeau vary from the silver theme.

This month’s walking costume is more colorful; while its underlying dress is white and its covering cloak a neutral dove color, the lining of the cloak, the “fancy cape or hood,” the “Circassian turban cap,” and the half boots feature both crimson and rose. The white van Dyke lace at neck and wrists only accentuate the vibrancy of the reds.

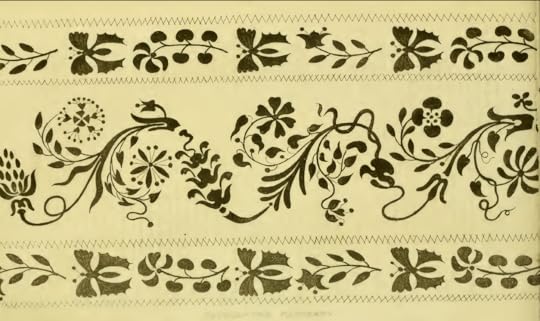

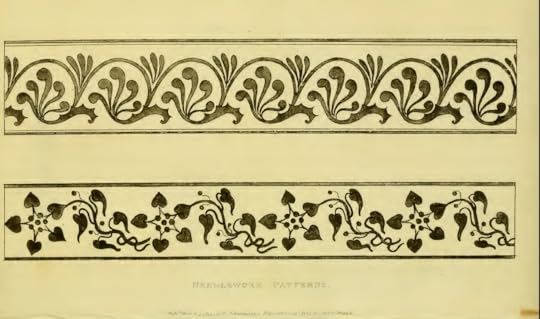

No fabric samples this month, but the issue does end with some intricate embroidery patterns of vines. The star and heart shapes of the second pattern seem unusual for the period; I wonder if the pattern was much reproduced?

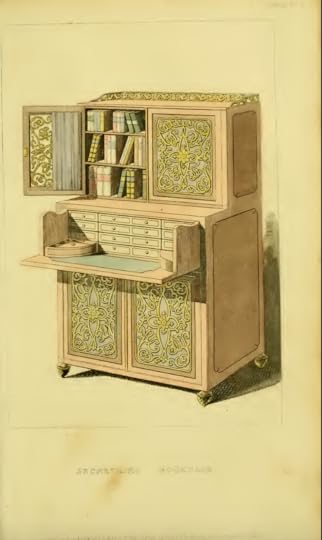

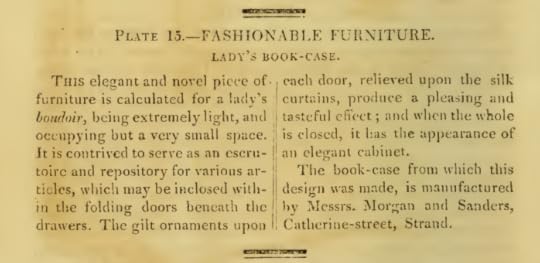

While I don’t usually include furniture prints in these posts, I couldn’t resist adding this one, which features a decorative ladies’ book-case. I found its folding doors and lots of drawers for storing all those little things a Regency lady might need to keep close to hand in her boudoir quite appealing. Too bad there are no titles visible on the books collected in this gilt-adorned piece of furniture—I would have liked to have known what titles Ackermann’s thought Regency ladies of 1814 would most likely keep close to hand . . .

SaveSave

June 21, 2017

Ackermann’s Fashion Plates February 1814

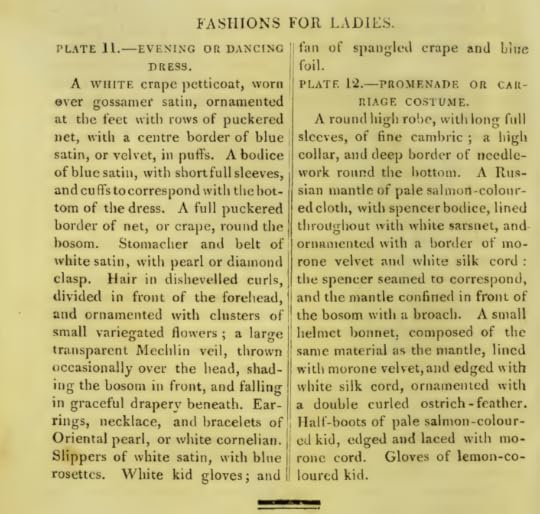

Decorative trims are the highlight of February 1814’s two fashion plates. The bottom of the gown in Plate 11, an “Evening or Dancing Dress,” features not one but three rows of trim: a row of blue satin or velvet in “puffs” is sandwiched between two rows of puckered net. This triple trim is mirrored on the cuffs of the gown’s short sleeves. On her head our lady wears a “large transparent Mechelin veil” which looks remarkably similar to the swags of lace decorating what looks to be a refreshment table beside her. I hope she doesn’t mistake one for the other and sweep up a dish of fruit instead of her veil . . .

Vol XI, no. lxii, plate 12

Vol. XI, no. lxii, plate 12

Plate 12’s gown is decorated with “a deep border of needlework round the bottom”—perhaps embroidered in the larger needlework pattern of the two featured at the back of this month’s magazine (see below)?

I got a bit excited when I saw the lady in Plate 12; at first glance, it appears she has red hair! (yes, I’m a redhead, and proud of it). But alas, the splash of color is merely the “morone velvet” lining the lady’s “helmet bonnet,” which matches the trim on her Russian mantle. When you look more closely, you can see that her hair is a very ladylike brown. I should have known better; despite the many historical romance novels that feature redheaded heroines, prejudices against red hair that had been prevalent since the Middle Ages (red hair being associated with Jewishness) had not at all abated by the Regency.

SaveSave

SaveSave

June 14, 2017

Ackermann’s Fashion Plates January 1814

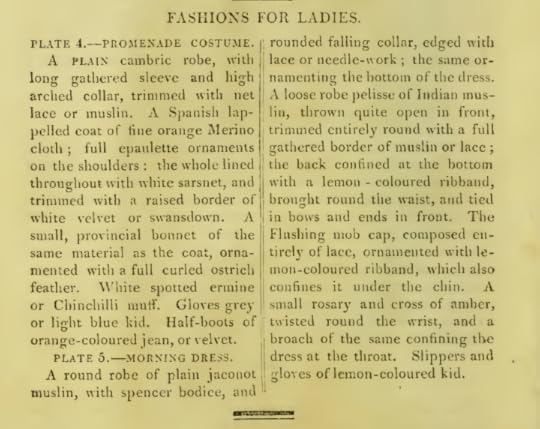

One of the fabric samples featured in the the December 1813 issue of Ackermann’s Repository was an orange wool, the color of which the writer noted “we expect to be the favourite colour of the season, in compliment to our new friends the Dutch” (see last week’s post for more on why the English and the Dutch were now “new friends”). And, lo and behold, the first fashion plate for January 1814 features an orange coat! “A Spanish lapeled coat of fine orange merino cloth” covers a fine cambric gown in Plate 4. Even the lady’s half-boots are made from orange jean. Swans, ermines, and geese have also contributed to the celebration, in the form of trim for the coat, fur for the muff, and a jaunty feather for the hat.

Vol. XI, no. lxi, plate 4

Plate 5 features a white “Morning Dress,” which, with its lemon-colored trimmings, slippers, and gloves, makes for a complimentary companion to the striking orange of plate 6. I’m wondering just what a “Flushing” mob cap is—anyone have any ideas?

Vol. XI, no. lxi, plate 5

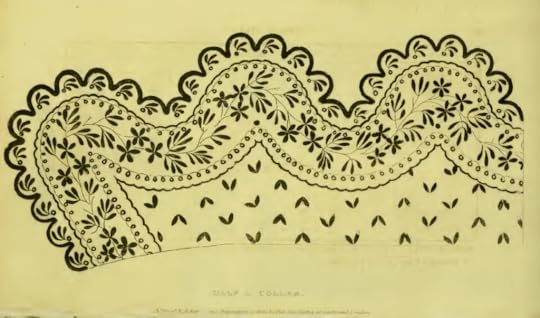

This month’s magazine does not include any fabric samples. Instead we have this lovely pattern of needlework for a “half collar.” I’m working on hand sewing a man’s shirt for the cover model for my next book, and it is painstaking work. I can only marvel at the skill of a person who could embroider a pattern like this just to decorate the top of a collar!

Pattern for Needlework: a “Half-Collar”

SaveSave

SaveSave

June 7, 2017

Ackermann’s Fashion Plates December 1813

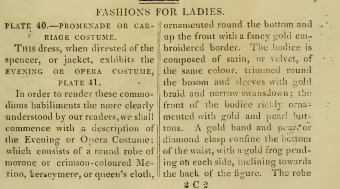

This month’s two fashion plates are really two views of one outfit: the Promenade or Carriage Costume of plate 40, which, when “divested of the spencer, or jacket, exhibits” the Evening or Opera Costume pictured in plate 41. Both here are crafted of “morone or crimson-colored Merino, kerseymere, or queen’s cloth,” to keep the wearer warm during the first month of winter. Fairchild’s Dictionary of Textiles defines “queen’s cloth” as “a term used in Jamaica, West Indies, for a type of fine, bleached cotton shirting,” which seems an odd alternative for Merino or kerseymere; perhaps “queen’s cloth” meant something different to the readers of Ackermann’s?

Vol. X, no. lx, plate 40

Vol. X, no. lx, plate 41

While the slippers depicted in plate 41 are described as “of crimson velvet, ornamented with gold fringe and rosettes,” our writer “recommend[s] those of white satin in preference.” Said writer also recommends a different pair of shoes be worn once the spencer of plate 40 is donned for outdoor travel: “half-boots or Roman shoes.” Did footmen typically take and store not only coats and hats, but boots as well after ladies changed into their more dainty footwear? Or did the ladies somehow tuck them inside their reticules?

The subject of footwear continues in the curious article which follows the fashion plate descriptions, entitled “Hints to Females on the Preservation of Health” from one signed “A Pedestrian.” Pedestrian notes that while boots made from jean, velvet, or similar light stuffs are appropriate for summer wear, women should take a page from men’s fashion and adopt footwear made from sterner stuff for the winter months. In particular, our author recommends Spanish leather, which, “from its more compact substance, close grain, and the oil used in its preparation” is “infinitely better adapted to repel the moisture and keep out the wet.” Ladies need not worry that they will have to trade fashion for utility, for “there is no doubt, that in a boot or shoe of leather the foot and ankle may be effectually displayed; and that this captivating part of the female form will best preserve its symmetry and neatness when it is so decorated.”

One of the fabric samples from this month’s volume seems to have been torn out of the page from the Philadelphia Library of Art’s volume. But the two remaining samples are jaunty enough to compensate somewhat for its loss. The first, a “new pattern for furniture,” “admits of almost every shade of lining and fringe, from the brilliant rose-colour to the more cool and softer shades of pea-green and jonquil.” I never thought of rose as a more brilliant shade than green or yellow, but perhaps those who lived at the time of the Regency did? Even more brilliant is the orange of the superfine Merino cloth of sample #3, “which we expect to be the favourite colour of the season, in compliment to our new friends the Dutch.” Napoleon had named his brother Louis Bonaparte king of Holland in 1806, then later forced him to abdicate and annexed the kingdom to France. But Napoleon’s defeat at Leipzig in October 1813 led to a Dutch uprising. And on November 21, 1813, a provisional Dutch government was created on behalf of the William of Orange, who was then living in England.

Will 1814’s fashion plates feature orange gowns?

May 31, 2017

Ackermann’s Fashion Plates November 1813

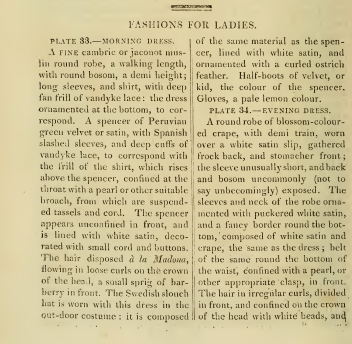

The shapes of Regency dresses are often simple, but the addition of detailed, intricate ornamentation differentiates the gowns of the bourgeois from those of the fashionable. Such fancy trims are on display in Ackermann’s fashion prints of November 1813. Plate 33, a Morning Dress, features a shirt with a “deep fan frill of vandyke lace, the dress ornamented at the bottom, to correspond.” Its accompanying spencer also features vandyke lace on the cuffs, as well as Spanish slashed sleeves and front embellishments made of cord and button.

Plate 33, Vol. X, no. liv

The sleeves and neckline of the Evening Dress in Plate 34 are ornamented with puckered white satin, to compliment to the blossom-colored crape of the round robe. The bottom of the trained gown is also adorned, with a combination of white satin and blossom-colored crape, in what looks a bit like oversized flower blossoms. The writer notes that the gown’s “back and bosom [are] uncommonly (not to say unbecomingly) exposed,” suggesting such low cut gowns might be verging on the edge of risqué in the early years of the 18-teens.

Plate 34, Vol. X, no. liv

Both prints show their models wearing their hair in loose curls, curls adorned with “a small sprig of barberry” in the informal morning dress, and “small autumnal flowers of various hues” for the formal evening dress. Real flowers, I wonder? Or artful imitations?

November’s fabric samples include #1, an “animated and lively sample of the true Circassian cloth,” a fabric that Fairchild’s Dictionary of Textiles reports is “a yard-dyed fabric made of wool and cotton with a diagonal wave. Original made in France with wool warp and filing; in England with mohair yarns.” Lively and warm enough for fall’s chill!

Fabric sample #2 may not look as interesting, a simple “specimen of the new patent twine cloth, for sheeting,” but its method of production is “extremely curious,” as the machine upon which it is produced is “worked by steam.” Steam-driven power looms had first been built in 1785, but this aside suggests how novel they still were in the Regency period.

May 24, 2017

Ackermann’s Fashion Plates October 1813

I’m as much, if not more, intrigued by the accouterments in this month’s prints than in the dresses themselves. Both prints feature ladies reclining on chairs, one seated, and one partially kneeling. Both chairs have scrolled backs, and slightly curved out legs, giving both an air of elegance to the ladies resting upon them.

I’m also curious about what these two ladies are holding in their hands. The one in plate 26, in “Morning Dress,” appears to have a tiny book of some sort in hand. A memorandum book? A small prayer book? It seems far too small to be a household account book, or even a journal or diary.

At first, I thought that the lady of plate 27 might be holding a newspaper, something I would have been very excited to see. But, realizing she was attired in “Evening Dress,” and that the sheets in her had seemed to be separate, rather than folded as a newspaper would be, I thought it more likely that a collection or book of sheet music might be intended here. She would make a lovely figure sitting down to the piano-forte in her pea-green gown, with its “deep flounce of lace round the feet, headed with silver netting.”

Plate 26, Vol. X, no. lviii

Plate 27, Vol. X, no. lviii

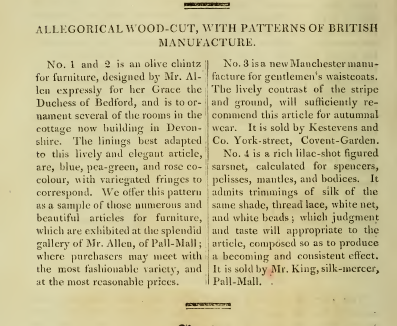

This month’s fabric samples include a chintz designed for “her Grace the Duchess of Bedford,” to “ornament several of the rooms in the cottage now building in Devonshire.” No, you can’t purchase the same exact fabric; what would the duchess say! The pattern is offered “as a sample of those numerous and beautiful articles for furniture, which are exhibited at the splendid gallery of Mr. Allen, of Pall-Mall.”

I’m drawn to fabric sample #4, described as a “rich lilac-shot figured sarsnet, calculated for spencer, pelisses, mantles, and bodices.” The sample looks more pink than lilac to my eye. The zig-zags topped with what look to be tiny French knots make for a very unusual fabric, one that would have had me hieing off to Mr. King’s silk mercer shop. And since his shop is also in Pall-Mall, perhaps I would have also taken a peek into Mr. Allen’s?