Bliss Bennet's Blog, page 5

May 17, 2017

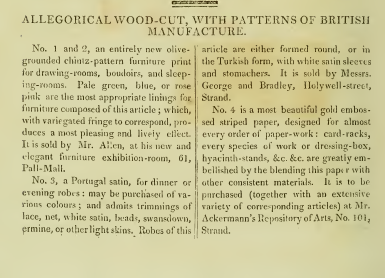

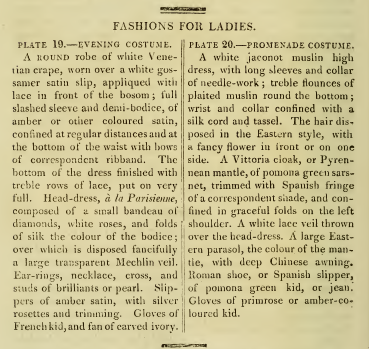

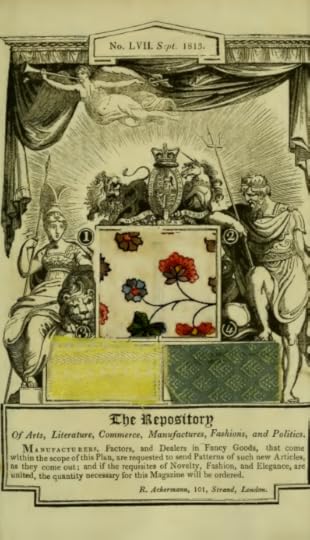

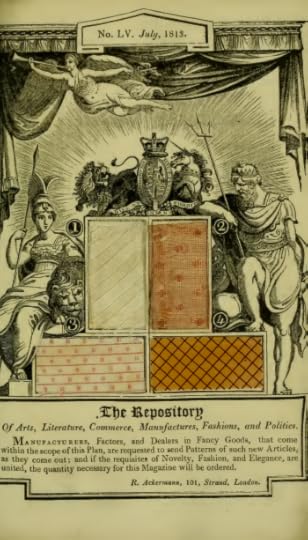

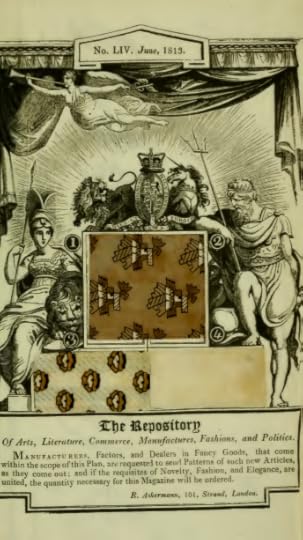

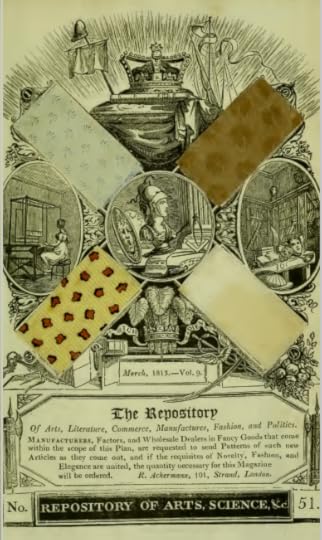

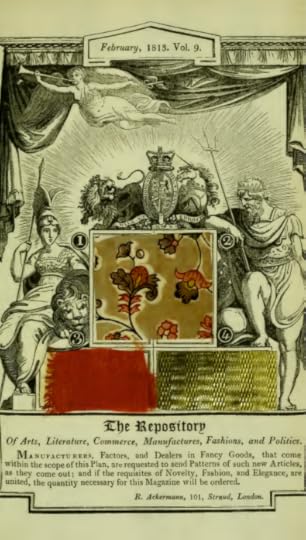

Ackermann’s Fashion Plates September 1813

For the first time, a plate is missing from the scans of Ackermann’s I’ve downloaded via Archive.org. The September 1813 edition scanned includes plate 19, “Evening costume,” but the page where plate 20, “Promenade Costume,” should be is blank. A victim of the habit of people cutting the plates out of magazines, even those in library collections, and selling them separately? Today such prints can be purchased for between $30 and $60 from rare print dealers online.

A Pinterest Board titled “1813” includes a (cropped) image of the print in question, so I’ve borrowed a copy from there. Our fashionable lady looks quite comfortable, reading her book with her “large Eastern parasol, with deep Chinese awning,” doesn’t she? I do wish the prints gave us a better idea of the shoes mentioned in the descriptions; I’d like to see if/how the “Roman shoe, or Spanish slipper” differed from a typical English lady’s slipper…

Plate 19, Vol X, no. lvii

Plate 20, Vol. X, no. lvii

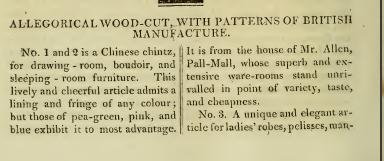

The celebration of Wellington’s Vittoria victory continues to be a theme in this month’s fabric sample #3, a “unique and elegant article for ladies’ robes, pelisses, mantles, and scarfs, styled the Vittoria striped gauze.” I wonder what the drapers might have said, if you asked them why it was a “Vittoria” striped gauze?

Ackermann’s fabric samples, September 1813

May 10, 2017

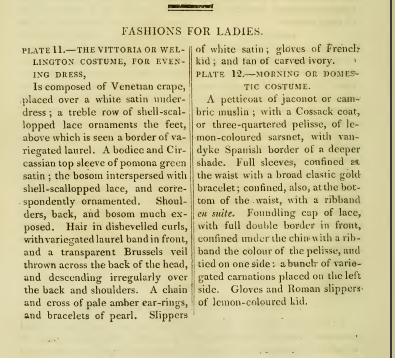

Ackermann’s Fashion Plates August 1813

This month’s fashions celebrate Wellington’s June 1813 victory at Vittoria, which led to the collapse of French rule in Spain. The evening dress in Plate 11 is labeled “The Vittoria or Wellington Costume,” although I don’t think there is anything in particular about its design that would lead one to think of either the English general or the town in which 1813’s battle was fought. Is a dress with “shoulders, back, and bosom much exposed” a sign of celebration? Or the bosom covered by “shell-scalloped lace”?

Plate 11, Vol. X, no. lvi

Plate 12, Vol. X, no. lvi

The Wellington celebration continues in this month’s fabric samples, with Thomas and Co. silk-mercers selling a “Wellington colonnade satin crape or gause, which can be had of ht proprietors in the varied colours of the season.” But other fabric purchasers may have had something other than the war in mind; the “variegated check gingam” in sample #1 is suggested not only for “the intermediate order of costume,” but also for “the sea-side trowser or bathing-wrap.” Is the sea-side trowser in question is part of a woman’s bathing costume? Or simply part of an outfit she might wear when promenading on the beach? My understanding is that many of those who engaged in sea bathing during the Regency did so in the nude…

Fabric samples, Ackermann’s August 1813

May 3, 2017

Fashion Advice from Ackermann’s Repository July 1813

As I mentioned in last week’s post, the July 1813 edition of Ackermann’s Repository featured in addition to its fashion plates a “Letter from a Young Lady in London to Her Friend in the Country,” a letter replete with information on the latest in urban fashion. Some key shifts in fashion our Lady reports:

• The adoption of the Cossack coat and Pomeranian mantle, in place of the spencer and French cloak

• Fashionable headgear includes the “skimming-dish hat of straw or chip”; the “large hamlet poke, with lace bands, brought under the chin”; and “the provincial bonnet, composed of satin and lace, ornamented with flowers”

• Trains are beginning to “revive” in dancing dresses, although our young lady fears “they can never be admitted in the dancing dress, without infringing on good sense and good taste.”

Add-on bodice

• Colored satin bodices have become too common, so much that they “can no longer be considered as genteel, or select,” although our Lady contends for their “utility, in offering an easy purchased change.” (See this informative post by Natalie Garbett for more on these add-on bodices)

• Hair worn in “the Grecian style” is better than wearing a turban or even a small Spanish hat, especially for “the female who has not passed her meridian.”

• Diamonds and pearls “must always retain their pre-eminence,” but “bracelets of wrought gold, or of colored enamel, to represent small natural flowers” are also in style

• Satin half-boots for full dress are decidedly out (“most sensibly exploded”!)

Chinese fan 1820-30; Philadelphia Museum of Art

• A “few first rate fashionables” have given up their parasols in exchange for “the Oriental or Indian fan composed of feathers,” but such items are “as yet too singularly attractive for general adoption.” Wouldn’t that make you wild to get your hands on one??

April 26, 2017

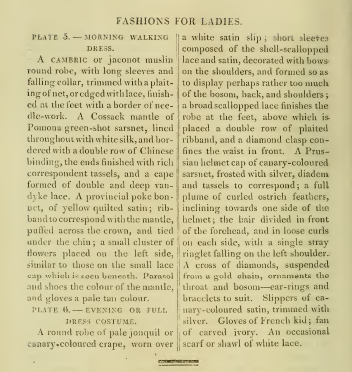

Ackermann’s Fashion Plates July 1813

With the line of Regency gowns so straight and plain, dressmakers had to look to other parts of a dress for places to exert their creativity. One such part was a dress’s sleeves. While some Regency gowns boast sleeves as straight as their skirts, many feature sleeves with gentle or gigantic puffs. Still others display intricacies that would look overly fussy on a dress with a more curved or intricate line. Take for instance the sleeves on Plate 6: “short sleeves composed of the shell-scalloped lace and satin, decorated with bows on the shoulders, and formed so as to display perhaps rather too much of the bosom, back, and shoulders.” The sleeves look to me like tiny iced cupcakes, good enough to eat—which is perhaps why the writer felt called to add that cautionary note about the sleeves’ cut. All too easy to move from nibbling on a sleeve to nibbling on a bosom, back, or shoulder, no?

Plate 5, Vol. X, no. lv

Plate 6, Vol. X, no. lv

Have you seen other examples of intricate Regency dress sleeves?

This month’s issue features another “Letter from a Young Lady in London to Her Friend in the Country,” filled with fashion advice (which I will reprint in next week’s blog). Arbiter Elegantarium, who once delivered detailed advice via the fashion plates, seems to have been replaced by this new occasional feature. But perhaps AE has taken refuge in writing the fabric sample descriptions? Very different from the descriptions in past issues, July’s notes include digressions about choosing a dress color to match one’s complexion and the exhortation to avoid wearing a dress made of fabric of all one color: “It rarely happens, that a dress of one unbroken color, be it ever so brilliant, adorns the wearer, be she dark or fair, or her figure ever so graceful: so large a mass of color overpowers the countenance and complexion, and produces no high opinion of the taste of the wearer.” Do you agree with this opinion?

April 19, 2017

Ackermann’s Fashion Plates June 1813

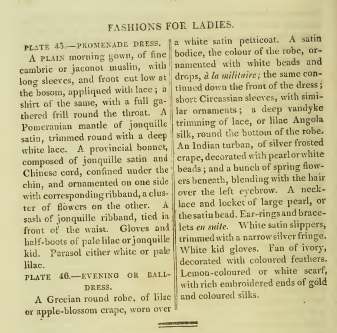

The writer of the descriptions and the worker who colored the plates for June 1813’s issue seem not to have been on the same page. The satin “Pomeranian mantle” of plate 45 is described as “jonquille,” a color Regency researchers say is a yellow, similar to that of a spring Narcissus (or jonquil). But the mantle in the plate appears to be light blue. Plate 46’s “Ball Dress” appears white in the plate, but is reported to be “lilac or apple-blossom” in the description. And the scarf worn over it appears to be a blueish-green, while the copy describes it as “Lemon-coloured or white… with rich embroidered ends of gold and coloured silks.” I wonder how often the writer and the person hired to hand-color a fashion plate got their wires crossed?

Plate 45, Vol. IX, no. liv

Plate 46, Vol. IX, no. liv

Whether the underlying dress is white, lilac,or apple-blossom, the beadwork and hem trimming on this ball gown is making me drool: “white beads and drops, à la militaire” and “a deep vandyke trimming of lace, or lilac Angola silk, round the bottom of the robe.” I don’t know if my needlework and beading skills would be up to the task, but I find myself itching to attempt to reproduce these fantastic adornments. This may be one of my favorite plates in all of Ackermann’s to date.

June’s fabric samples seem to designed to puff two particular warehouses. First, “Allen’s celebrated furniture warehouse” in Pall Mall, which has “recently built and spend a most spacious and elegant saloon, where, by a very ingenious invention, the printed and cotton furniture is displayed at one view, to the greatest advantage, and so as to afford an easy decision as to effect.” I wonder what that “ingenious invention” might have been?

Second is Mr. Millard’s East India warehouse in Cheapside, which is advertised as having “Imperial cotton twine shirting” that can be found at no other house, as well as a wide variety of muslins, from “the lowest value, for draperies only, up to the Indian shawl of 100 guineas.” Did Mr. Ackermann get a cut of Mr. Millard or Mr. Allen’s profits, if their customers mentioned where they had heard of them, I wonder?

Anyone have any idea of what “British King Cobb” might be? Such a name is given to sample #3, the pattern on which is described as “an imitation of that splendid article worn by the Great Mogul.” I find it rather ugly, myself, but perhaps the fashion for Oriental garb made it acceptable to 1813’s fashionables?

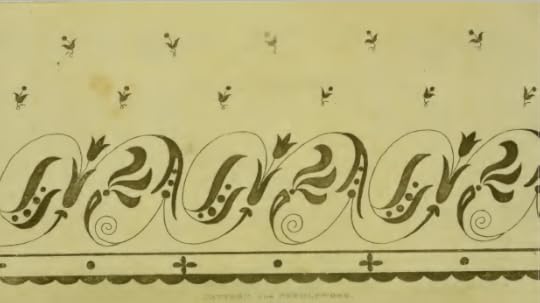

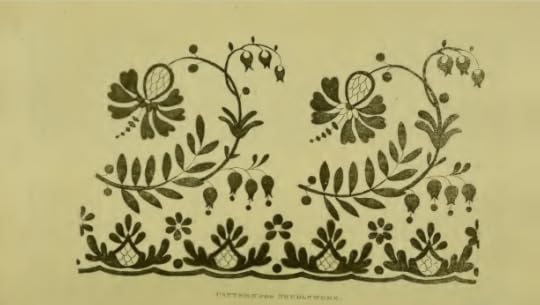

Tulips and other small flowers adorn this month’s needlework pattern:

April 12, 2017

Ackermann’s Fashion Plates May 1813

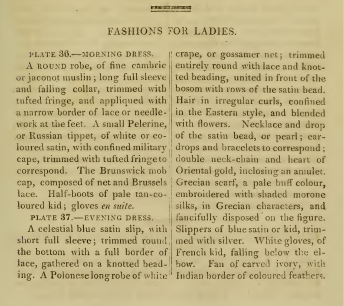

What catches my eye in May 1813’s fashion plates are the accessories, at least in Plate 37’s “Evening Dress.” Over the celestial blue satin slip lies not only a “polonaise long robe of white crape, or gossamer net, trim entirely round with lack and knotted beading,” but also a “Grecian scarf, a pale buff color, embroidered with shaded morone silks in Grecian characters.” One cannot make them out from this plate, but I do wonder just what “characters” the embroiderer chose to feature—Greek letters? Figures similar to those found on ancient Greek pottery? The novel I am currently working on features some rather racy Greek poetry in translation; can you imagine a bluestocking embroidering something similarly scandalous on her scarf?

The wearer of the Evening Dress also wears “a double neck-chain and heart of Oriental gold, inclosing an amulet.” Is there something special about “Oriental” gold? And what kind of amulet does that heart of gold “inclose”? Lots of potential for secret messages and codes here, don’t you think?

Plate 37, Vol. IX, no. liii

I think the most amusing adornment this month is in Plate 36—the very tiny dog rushing in from the right-hand side of the page, eager to greet its mistress. Do you think she will be able to set down her book and scoop it up before it jumps all over her clean white gown?

Plate 36, Vol. IX, no liii

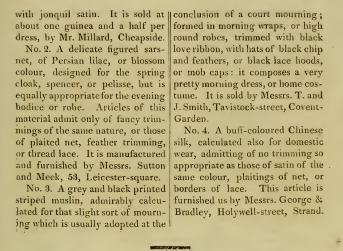

This month’s fabric samples are all intended for domestic or morning wear, including a “Smolensko striped imperial washing silk.” Was said silk imported from Smolensk, one of the cities that Napoleon had invaded during his ill-fated invasion of Russia a year earlier? Purchasing such a product would be a sign of patriotism, would it not?

The issue also includes another striking needlework pattern. I’m a needlepoint gal myself, but these patterns look like they might be for either embroidery or crewl work.

April 5, 2017

Ackermann’s Fashion Plates April 1813

In Regency romances, we often read of characters perusing fashion plates to choose patterns for their own dresses. But in looking at Ackermann’s April 1813 plates, I’m struck by the fact that such plates are often drawn in a way that would make it difficult, if not impossible, for it to be used as a precise model for an actual dress pattern. Plate 29, of a “Morning Costume,” is shown full on front, but Plate 30, for a “Carriage Costume,” is a side view, and with its lady seated. The long Russian mantle worn over the “high round robe of jaconet or cambric muslin” covers all of the details of the dress’s bodice and sleeves. Would a viewer know enough from the description—”with plaited bodice, long sleeve, and deep falling frill, terminated with a vandyke of needlework”—to be able to faithfully reproduce this dress? Or was the idea less about providing instructions for making a perfect copy, and more about giving readers (and dressmakers?) a more general sense of what was currently deemed fashionable?

Plate 30 does provide a luscious example of a distinctly Regency color: “pomona or spring green.” Doesn’t it make you eager to throw off the chills of winter and hunt for the green points of spring bulbs poking through last fall’s leaves?

Vol. IX, no. xvii, plate 29

Vol. IX, no. xvii, plate 30

[image error]

This month’s issue includes no fabric samples, but instead this lovely pattern for needlework. Can you imagine spending a rainy spring afternoon adding this pattern to the hem of a gown?

March 29, 2017

Ackermann’s Advice: “Letter on Personal Decoration”

Unlike earlier editions of Ackermann’s, in which the pseudonymous Arbiter Elegantiarum doled out fashion advice as part and parcel of the month’s commentary on its fashion plates, March 1813’s issue includes a separate column devoted to “personal decoration.” It is couched as a letter from a fashionable young lady, Julia, who has taken up abode in Grosvenor-square, and is writing to an unnamed correspondent in the country (an aunt, perhaps?) Did Ackermann realize that young women would be more receptive to fashion advice in the form of up-to-the-minute news from a friendly female rather than as hectoring advice about what should be from an unknown gentleman?

After the opening two paragraphs of polite greetings and assurances of friendship and continuing decorous behavior, Julia begins her discussion of fashion by asking her correspondent to “inform my cousins, that the Merino cloth coats they purchased last winter, may, with a little transformation, be considered very fashionable for the present season.” Today, if someone were told to “transform” her clothing by taking off some ornaments and replacing them with others, one might be forgiven for assuming that she had not the funds to purchase new garments. But in the nineteenth century, because the price of many fashionable fabrics was so high, many a well-off lady refashioned her garments to suit current trends.

Cap à la russe

In 1813, “the Russian costume pervades every order of personal decoration,” Julia declares, which accounts for the “helmet à la Russe” which she plans to purchase for her country cousins, as well as the frequent appearance of ermine, mole, sable, and other skins from animals native to “the North” on the coats of London’s fashionables this season. (See January and February 1813’s posts for examples)

Despite January 1813’s fashion plates, which both featured cloaks, Julia declares that “coats of cloth, satin, or velvet have been in more request this winter,” as cloaks, unless “worn over a spencer, are not found of sufficient warmth to secure the wearer from the inclemency of a severe season.”

Julia also imparts news about women’s hair styles and gowns and reports that “broaches, representing natural flowers, and sprigs of the same, for the hair, are among the novelties most attractive in this order of female adornment.”

After reading Julia’s letter, do you think you’d know enough to dress yourself to meet 1813’s fashion demands?

Brooch: http://auctions.freemansauction.com/a...

March 22, 2017

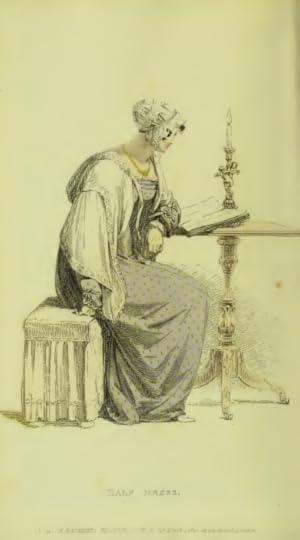

Ackermann’s Fashion Plates March 1813

Earlier this month, I attended a wake for a young Catholic man. As I watched the mourners moving through the room, I noticed that many of the girls and young women wore necklaces with crosses of silver or gold. I had always regarded the wearing of such crosses as a particularly Catholic tradition, but this month’s fashion plates reminded me that Protestant women in the Regency period often donned the cross as an adornment, too. In both of March 1813’s plates, one featuring a Half-Dress, the other an Opera Dress, the ladies wear necklaces with a cross: in Plate 21, of amber beads; in Plate 22, of white satin beads. And of course, this reminds me of Jane Austen’s topaz cross, gifted to her by her brother Charles. Was wearing a cross always appropriate, no matter the occasion?

Vol. IX, no xvi, plate 21

Vol. IX, no xvi, plate 22

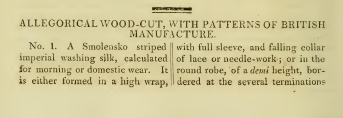

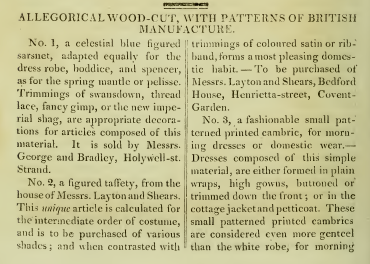

March’s “Patterns of British Manufacture” are all fabrics, three dress materials and one of linen shirting. The latter, despite being sold by the “East India Warehouse,” is apparently an English manufacture, for Ackermann declares it “of a quality equal to, and nearly half the price of Irish and foreign linens.” And it “prevents[s] a too profuse perspiration” to boot!

“It is sold, wholesale and by the piece, at the beforementioned warehouse, No. 16, Cheapside, and at no other house in London.” Were Regency shoppers drawn by such claims of exclusivity, I wonder?

Vol. IX, no xvi

March 15, 2017

Ackermann’s Fashion Plates February 1813

To keep warm in the chilly days of February 1813, ladies are recommended to don cloaks with a military flair. In plate 13, a Cossack cloak, of “pale Russian flame-coloured cloth” covers the fashionable Evening Dress, while a “Prussian hussar cloak, of Sardinian blue velvet” with a “variegated ball fringe” protects the lady from wintry winds during her morning walk. The “Russian flame-coloured cloth” also featured in last month’s fashion plate; I haven’t been able to discover just why this color, which appears in the plates more as a tan than a red, should be labeled “Russian.” Perhaps because during Napoleon’s invasion of Russia in 1812, the cossacks were ordered to burn the villages, towns and crops as they retreated, so that the French would not be able to live off the land they were invading?

Vol. IX, no. xv, plate 13

The oversized muff in Plate 14, a Promenade or Walking costume, is made of spotted ermine, a trim used in both of last month’s (January 1813’s) plates. The spots look amazingly regular, and very large, almost as if they were trimmings added on to a plain white ermine background. It does look amazingly warm, though, doesn’t it?

Vol. IX, no xv, plate 14

This month’s “Patterns of British Manufacture” includes both fabric and paper samples. Just look at #4, a “most beautiful gold embossed striped paper, designed for almost every order of paper-work.” It appears decidedly modern, does it not? I wonder how much Ackermann’s sold it for?

Vol. IX, no. xv