Rachel Neumeier's Blog, page 56

December 14, 2023

Opening with description

There’s no way to open a novel in a way that doesn’t contribute to a sense of style, of mood, and of voice. But opening with description means that you’re also opening in a way that brings the world to the forefront in a way that opening with dialogue or incident doesn’t generally achieve. Let’s look at an opening that’s very description-focused. Here is the opening of A Stranger in Olondria by Sofia Samatar.

To take a better look at how this opening works, I’m including the first 1300 words, which lets me include some paragraphs I particularly want to include.

***

As I was a stranger in Olondria, I knew nothing of the splendor of the coasts, nor of Bain, the Harbor City, whose lights and colors spill into the ocean like a cataract of roses. I did not know the vastness of the spice markets of Bain, where the merchants are delirious with scents. I had never seen the morning mists adrift above the surface of the green Illoun, of which the poets sing; I had never seen a woman with gems in her hair, nor observed the copper glinting of the domes, nor stood upon the melancholy beaches of the south while the wind brought in the sadness from the sea. Deep within the Fayaleith, the Country of the Wines, the clarity of light can stop the heart: it is the light the local people call “the breath of angels” and is said to cure heartsickness and bad lungs. Beyond this is the Balinfeil, where, in the winter months, the people wear caps of white squirrel fur, and in the summer months the goddess Love is said to walk and the earth is carpeted with almond blossom. But of all this I knew nothing. I knew only of the island where my mother oiled her hair in the glow of a rush candle, and terrified me with stories of the Ghost with No Liver, whose sandals slap when he walks because he has his feet on backwards.

My name is Jevick, I come from the blue and hazy village of Tyom, on the western side of Tinimavet in the Tea Islands. From Tyom, high on the cliffs, one can sometimes see the green coast of Jiev, if the sky is very clear; but when it rains, and all the light is drowned in heavy clouds, it is the loneliest village in the world. It is a three-day journey to Pitot, the nearest village, riding on one of the donkeys of the islands, and to travel to the port of Dinivolim in the north requires at least a fortnight in the draining heat. In Tyom, in an open court, stands my father’s house, a lofty building made of yellow stone, with a great arched entryway adorned with hanging plants, a flat roof, and nine shuttered rooms. And nearby, outside the village, in a valley drenched with rain, where the brown donkeys weep with exhaustion, where the flowers melt away and are lost in the heat, my father had his spacious pepper farm.

This farm was the source of my father’s wealth and enabled him to keep the stately house, to maintain his position on the village council, and carry a staff decorated with red dye. The pepper bushes, voluptuous and green under the haze, spoke of riches with their moist and pungent breath; my father used to rub the dried corms between his fingers to give his fingertips the smell of gold. But if he was wealthy in some respects, he was poor in others: there were only two children in our home, and the years after my birth passed without hope of another, a misfortune generally blamed on the god of elephants. My mother said the elephant god was jealous and resented our father’s splendid house and fertile lands; but I knew that it was whispered in the village that my father had sold his unborn children to the god. I had seen people passing the house nudge one another and say, “He paid seven babies for that palace;” and sometimes our laborers sang a vicious work song: “Here the earth is full of little bones.” Whatever the reason, my father’s first wife had never conceived at all, while the second wife, my mother, bore only two children, my other brother Jom and myself. Because the first wife had no child, it was she whom we always addressed as Mother, or else with the term of respect, eit-donvati, “My Father’s Wife;” it was she who accompanied us to festivals, prim and disdainful, her hair in two black coils above her ears. Our real mother lived in our room with us, and my father and his wife called her “Nursemaid,” and we children called her simply by the name she had borne from girlhood: Kiavet, which means Needle. She was round-faced and lovely, and wore no shoes. Her hair hung loose down her back. At night she told us stories while she oiled her hair and tickled us with a gull’s feather.

Our father’s wife reserved for herself the duty of inspecting us before we were sent to our father each morning. She had merciless fingers and pried into our ears and mouths in her search for imperfections; she pulled the drawstrings of our trousers cruelly tight and slicked down our hair with her saliva. Her long face wore an expression of controlled rage, her body had an air of defeat, she was bitter out of habit, and her spittle in our hair smelled sour, like the bottom of the cistern. I only saw her look happy once: when it became clear that Jom, my meek, smiling elder brother, would never be a man, but would spend his life among the orange trees, imitating the finches.

My earliest memories of the meetings with my father come from the troubled time of this discovery. Released from the proddings of the rancorous first wife, Jom and I would walk into the fragrant courtyard, hand in hand and wearing our identical light trousers, our identical short vests with blue embroidery. The courtyard was cool, crowded with plants in clay pots and shaded by trees. Water stood in a trough by the wall to draw the songbirds. My father sat in a can chair with his legs stretched out before him, his bare heels turned up like a pair of moons.

We knelt. “Good morning father whom we love with all our hearts, your devoted children greet you,” I mumbled.

“And all our hearts, and all our hearts, and all our hearts,” said Jon, fumbling with the drawstring on his trousers.

My father was silent. We heard the swift flutter of a bird alighting somewhere in the shade trees. Then he said in his bland, heavy voice: “Elder son, your greeting is not correct.”

“And we love him,” Jom said uncertainly. He had knotted one end of the drawstring about his father. There rose from him, as always, an odor of sleep, greasy hair, and ancient urine.

My father sighed. His chair groaned under him as he leaned forward. He blessed us by touching the tops of our heads, which meant that we could stand and look at him. “Younger son,” he said quietly, “what day is today?”

“It is Tavit, and the prayers are the prayers of maize-meal, passion fruit, and the new moon.”

My father admonished me not to speak so quickly or people would think I was dishonest; but I saw that he was pleased and felt a swelling of relief, for my brother and myself. He went on to question me on a variety of subjects: the winds, the attributes of the gods, simple arithmetic, the peoples of the islands, and the delicate art of pepper-growing. I stood tall, threw my shoulders back, and strove to answer promptly, tempering my nervous desire to blurt my words, imitating the slow enunciation of my father, his stern air of a great landowner. He did not ask my brother any questions. Jom stood unnoticed, scuffing his sandals on the flagstones—only sometimes, if there happened to be doves in the courtyard, he would say very softly, “Oo-ooh.” At length my father blessed us again and we escaped, hand in hand, into the back rooms of the house; and I carried in my mind the image of my father’s narrow eyes: shrewd, cynical, and filled with sadness.

***

What do you think? Here are my basic impressions:

–The prose is beautiful.

–The voice of the narrator is the voice of a poet.

–The sense of place is profound.

–There is no generous sensibility here.

That last opinion is informed by the rest of the chapter, but it comes through clearly enough in these few paragraphs. I love the worldbuilding, but I dislike the lack of kindness in the world so beautifully evoked. The mother cares for her sons, but she is powerless to protect her elder son from her husband’s first wife, or from her husband when he tries, essentially, to have the elder son beaten into being the heir he wants. No one else shows a trace of kindness anywhere in the first chapter. This story is the precise opposite of cozy fantasy. One assumes the narrator’s circumstances will improve, or at least change.

This is a story where the world is everything — at least so far. The characters are set deeply into the world. There is a tremendous sense of depth and reality. This world is a real place, people by real people — that’s how it feels. I love this kind of worldbuilding, though a novel written this way requires much closer attention than, say, a quick, witty contemporary fantasy.

But this is also a story that begin in a way that invites the reader to admire the prose and the worldbuilding, while being fairly strongly repulsed by the characters and the world. The single line that most strongly evokes unkindness is “outside the village, in a valley drenched with rain, where the brown donkeys weep with exhaustion.” Before we get to the unkindness of the first wife and the revolting detail about the spittle, we have this offhand comment about donkeys weeping with exhaustion.

Do donkeys actually cry tears of misery? It’s believed, pretty axiomatically, that although all sorts of animals produce tears to lubricate their eyes and remove grit from their eyes, no nonhuman animals cry tears from misery or grief. Axiomatic beliefs of this sort can get in the way of perceiving reality. A desire to anthropomorphize animals gets in the way from the other direction. Romanticizing tears as a super-special way to express grief or misery gets in the way yet again. So I will state for the record that we don’t know for sure and also that it doesn’t really matter, since donkeys can certainly be miserable and apparently these donkeys are obviously miserable, anybody can see their misery, and that’s just part of life. There’s no sympathy implied in that passage. We see this again a few paragraphs farther on, when the narrator refers to his elder brother being beaten by “dull-eyed” workers from the field, with an obvious implication that the field laborers are treated so unkindly that they have no capacity to sympathize with someone else.

This opening plus the rest of the first chapter is as far from showing a world infused with a generous sensibility as you can get.

Will I go on with the book? Yes, I will. Someone at World Fantasy made a comment in passing that struck me – this was commenter David H’s friend – to the effect that if you wait to be in the mood to read a particular book, you’ll probably never read it and therefore you’ll miss whatever it might have offered. This, as I say, struck me.

I’ve been reading so few books lately, fewer still by new-to-me authors, and particularly few that seem as though they’re going to be demanding. I haven’t wanted to spare the time or attention for books like that. On the other hand, I’ve been wanting to read certain books for a long time, including this one. I’m going to read it, by gum, starting by reading one chapter at a time. While I’m vehemently opposed to reading books I dislike, I don’t dislike this book – not yet. I dislike this one thing about it: the unkindness of the world being drawn. That’s an important thing. Nevertheless, I’m going to go on and see where it leads, and along the way, enjoy the language and admire the worldbuilding.

Meanwhile, what does this remind me of?

It reminds me of Mary Stewart’s outstanding Merlin trilogy, starting with the Crystal Cave. The first link here goes to a paper omnibus, the second to the first book of the Kindle edition series.

This story, too, begins when the narrator is a child. This story also offers beautiful prose. And this story also begins with a childhood home that is not kind and that is filled with adults who may be, or are, dangerous. That story leads the narrator into a life that is not easy, but — and this is key — a life that is worth living. I love this series. I’m even okay with the fourth and final book, where Mary Stewart does as well as any author every has (or ever could) to handle Mordred’s story in a way that is believable, but isn’t filled with bitterness, though it does end in tragedy.

I’m curious to see whether Sofia Samatar’s book might create the same sense of a life worth living and a story worth telling. But, I have to say, I’m looking forward to Jevick getting out of his father’s house and heading for Olondria.

Please Feel Free to Share:

The post Opening with description appeared first on Rachel Neumeier.

December 13, 2023

More fun with verbs that aren’t exactly verbs

So, in this surprisingly popular recent post, I was talking about verbs that join up with adverb/preposition words to form meanings that aren’t related to the constituent words. Those, as you recall, are called phrasal verbs, and examples are things like get out, carry on, and set forth.

Two comments about phrasal verbs: yes, you were all correct, the post about versions involving “set” said 60,000 WORDS were used to describe 580 EXAMPLES of phrasal verbs using “set,” which makes far, far more sense than the way I read that at first, as 60,000 different examples. So, I’m glad to have that sorted out, and thank you to everyone who pointed to the correct reading of those numbers.

Second, I think I understand out why words like “on” and “out” count as adverbs in phrasal verbs when they are obviously prepositions. That’s because in a phrase like, “Set the apples on the table,” the preposition is doing stuff related to the nouns, while if there are no nouns, then the thing that used to be the preposition is doing stuff related to the verb. Poof, it’s now an adverb. I think this is still a little peculiar and arguable, but I’m pretty sure that’s the thought behind defining those words as adverbs when they occur in phrasal verbs. (I didn’t look it up, though; this just seems like a reasonable explanation for this re-definition of “on” as an adverb.)

But, the point is, once one begins thinking about verbs that aren’t exactly verbs, you can have worlds of fun with words like that. There’s one obvious example that is completely different from phrasal verbs. This is the gerund.

She is studying for exams. –> studying is the present participle; eg, it is a verb.

Studying is not her favorite thing to do. –> studying is a noun, which is why it is a thing; eg, it is a gerund.

And this reminded me of a Lingthusiasm podcast I was listening to recently, about verbs, and the way anything can be verbified, although some words verbize more easily than others. You can and should decide whether something is a verb or a noun by looking at what it is doing in the sentence and whether it behaves like a verb or like a noun. Thus, if you say, “I’m adulting today, but tomorrow I plan to cat,” then you’re using both “adult” and “cat” as verbs. They are doing verb things. If you change the tense of the sentence, then those words change the way verbs ought to change: “Yesterday, I adulted, but today, I am catting.”

And THAT reminded me of using EXACTLY THIS technique when I was writing my master’s thesis, which was then published in the American Journal of Botany. I linked to it in case you are dying to read an article written in Exceedingly Boring Academic Style. The other author was my advisor, but all the writing was mine. But the reason I bring it up is that this was the article that forced me to learn the difference between effect and affect.

I don’t mean just “learn the different meanings.” I knew the different meanings. I mean how to use them correctly even though both words start to look wrong 100% of the time when you keep using them over and over. There are no good synonyms, both get used a thousand times in related contexts, and it is enormously tedious to have to think about which form to use each time you need one or the other. A quick wordcount indicates that I used “effect” in the linked paper 73 times, and “affect” only eight times, which is a remarkable bias toward the noun form and suggests that alternate words or phrases are easier to come up with for the verb.

Regardless, when you are writing academic prose, you have to get this right every single time or you will look like an idiot. Yet, as we all know, when you think about something of this kind too much, everything starts to look wrong and you lose the ability to recognize nouns even though you have been handling nouns just fine in literally hundreds of thousands of sentences since you first learned to talk. The way to make this much less tedious is to (a) know which is the verb and which is the noun; and (b) do a very fast is-this-a-verb check each time you use one. The check is exactly as suggested above: you check whether the word is acting like a verb:

Alterations in the architecture of competing individuals or species, which can occur under enhanced UV-B, may effect light interception and photosynthesis.

... which occurred under enhanced UV-B, effected light interception and photosynthesis.

The word did the verb thing. You want the verb form. Change it to “may affect” and move on.

Changing the tense of the sentence forces the verbs to reveal themselves. This is a very fast way to confirm the verb-hood of a word so that you can quit worrying about it. I did in fact literally switch sentences and phrases from present to past and back again in order to confirm which form I wanted. I mean, in my head, not on the screen. With practice, you learn to do this check so fast it’s almost like you didn’t do it at all. Less than a second. With more practice, you train the back of your brain to just pick the right word every time without needing to pay conscious attention, and as far as I know, this particular mistake is one I never make anymore, even when I’m typing “cyprus” instead of “cypress” or “pebble” instead of “people.” Which happens all the time. But even now that I am constantly typing “has” instead of “had” — it’s not my fault, listen, the keys are right next to each other — but what I’m saying is, effect and affect, I still seem to have cold, way down deep where my brain really believes it.

The verb check is more reliable than a noun check, because the quickest, easiest noun check is “Does the word have an article in front of it?” Because if it does, it’s doing noun things, right? But lots of times, “effect” doesn’t take an article.

Effects of parental competition and UV-B exposure on the next generation were estimated as offspring germination success, growth, and flower, fruit, and seed production.

Look, no article, so you can’t quickly confirm that “effects” is a noun that way. But you can easily change the sentence to present tense and confirm that way that “effects” doesn’t change and therefore it isn’t a verb, eg, it’s a noun.

I realize perfectly well that you can also just know what nouns are and what verbs are and do it that way. I’m saying that changing verb tense will work even if your brain is largely nonfunctional because you have used “effect” 73 times in your paper and by this time, it looks simultaneously right and wrong every time you use it.

AND this also works to separate participles from gerunds, should you ever happen to want to do that.

She is studying for exams. –> She studied for exams –> studying did the verb thing. It is a verb.

Studying is not her favorite thing to do. –> Studying was not her favorite thing –> studying did not do the verb thing. It is a noun.

And so when the Lingthusiasm episode talks about verbifying words, this is great! It’s great to think of verbs as words that do verb things and nouns as words that do noun things, and if you teach kids about that, then when some instructor in a college composition class asks, “Where’s the verb in this sentence?” or “Does this sentence have a verb?”, then the kid will know how to tell. It’s not about memorizing what a gerund is. It’s about looking at a sentence and seeing the -ing word is doing the noun thing, not the verb thing, so boom! It’s a noun, meaning a gerund.

Skiing down difficult slopes scares me. Reading is a favorite hobby. Today, I want to cat. Carry on, Private. To be, or not to be, that is the question. –> You can spot the verbs every time because they do verb things. Whatever sort of looks like it might be a verb, if it doesn’t do verb things, it’s not a verb at the moment.

The Lingthusiasm episode does different things with verbs; it’s all about hanging the rest of the sentence on the verb. That’s neat to think about too and if you’re not yet listening to Lingthusiasm, then if you have a boring drive over Christmas, this is the perkiest, most chipper podcast I can think of — good for staying awake, and as a plus always interesting.

If you have a favorite podcast, drop it in the comments! Driving = boring boring boring, at least if you are driving alone. Always happy to hear about other podcasts that I might like to try.

Please Feel Free to Share:

The post More fun with verbs that aren’t exactly verbs appeared first on Rachel Neumeier.

December 12, 2023

One of my favorite poems continued by ChatGPT

I love Swinburne because of his use of rhythm. I’m sure other poets have used rhythm as beautifully as Swinburne, but I can’t think of any. (If you can, by all means drop suggestions in the comments!)

I’m going to show you one entire poem. I would like to draw your attention to the use of vocabulary that is out of the common way, the use of alliteration, the use of slightly nonstandard punctuation, and most of all the use of rhythm in this poem. We can also notice the number of lines per stanza and the number of syllables per line. All this is before we consider meaning. Then we’ll see what ChatGPT does with this. The instruction for Chat GPT will be simple: Continue this poem. It got the whole thing prior to being given that instruction. I’m going to mark the place where Chat GPT takes over, though as you’ll see, there’s not the least need to do so.

A Forsaken Garden by ALGERNON CHARLES SWINBURNE

In a coign of the cliff between lowland and highland,

At the sea-down’s edge between windward and lee,

Walled round with rocks as an inland island,

The ghost of a garden fronts the sea.

A girdle of brushwood and thorn encloses

The steep square slope of the blossomless bed

Where the weeds that grew green from the graves of its roses

Now lie dead.

*

The fields fall southward, abrupt and broken,

To the low last edge of the long lone land.

If a step should sound or a word be spoken,

Would a ghost not rise at the strange guest’s hand?

So long have the grey bare walks lain guestless,

Through branches and briars if a man make way,

He shall find no life but the sea-wind’s, restless

Night and day.

*

The dense hard passage is blind and stifled

That crawls by a track none turn to climb

To the strait waste place that the years have rifled

Of all but the thorns that are touched not of time.

The thorns he spares when the rose is taken;

The rocks are left when he wastes the plain.

The wind that wanders, the weeds wind-shaken,

These remain.

*

Not a flower to be pressed of the foot that falls not;

As the heart of a dead man the seed-plots are dry;

From the thicket of thorns whence the nightingale calls not,

Could she call, there were never a rose to reply.

Over the meadows that blossom and wither

Rings but the note of a sea-bird’s song;

Only the sun and the rain come hither

All year long.

*

The sun burns sere and the rain dishevels

One gaunt bleak blossom of scentless breath.

Only the wind here hovers and revels

In a round where life seems barren as death.

Here there was laughing of old, there was weeping,

Haply, of lovers none ever will know,

Whose eyes went seaward a hundred sleeping

Years ago.

*

Heart handfast in heart as they stood, “Look thither,”

Did he whisper? “look forth from the flowers to the sea;

For the foam-flowers endure when the rose-blossoms wither,

And men that love lightly may die—but we?”

And the same wind sang and the same waves whitened,

And or ever the garden’s last petals were shed,

In the lips that had whispered, the eyes that had lightened,

Love was dead.

*

Or they loved their life through, and then went whither?

And were one to the end—but what end who knows?

Love deep as the sea as a rose must wither,

As the rose-red seaweed that mocks the rose.

Shall the dead take thought for the dead to love them?

What love was ever as deep as a grave?

They are loveless now as the grass above them

Or the wave.

*

All are at one now, roses and lovers,

Not known of the cliffs and the fields and the sea.

Not a breath of the time that has been hovers

In the air now soft with a summer to be.

Not a breath shall there sweeten the seasons hereafter

Of the flowers or the lovers that laugh now or weep,

When as they that are free now of weeping and laughter

We shall sleep.

*

Here death may deal not again for ever;

Here change may come not till all change end.

From the graves they have made they shall rise up never,

Who have left nought living to ravage and rend.

Earth, stones, and thorns of the wild ground growing,

While the sun and the rain live, these shall be;

Till a last wind’s breath upon all these blowing

Roll the sea.

*

Till the slow sea rise and the sheer cliff crumble,

Till terrace and meadow the deep gulfs drink,

Till the strength of the waves of the high tides humble

The fields that lessen, the rocks that shrink,

Here now in his triumph where all things falter,

Stretched out on the spoils that his own hand spread,

As a god self-slain on his own strange altar,

Death lies dead.

*** *** *** *** *** *** *** *** *** *** *** *** *** *** ***

In that forsaken garden by the sea,

Where love and laughter used to roam so free,

Now lies a silence, deep and profound,

A stillness that wraps the desolate ground.

*

No footfalls echo, no voices call,

Only the sea’s mournful, rhythmic sprawl.

The once vibrant blooms, now turned to dust,

Memories linger, but love is a must.

*

The thorny thickets guard secrets untold,

Of tales of passion, of hearts once bold.

Gone are the lovers, entwined in delight,

Lost to the ages, veiled in the night.

*

The wind whispers tales of love’s sweet refrain,

But the roses are gone, and only thorns remain.

A ghostly garden in the twilight’s gleam,

Haunting reminders of a faded dream.

*

The sun beats down, unrelenting and harsh,

On the barren earth, where love made its march.

The rain weeps softly, a tear-laden sigh,

For the love that flourished but could not defy.

*

As the waves crash against the rugged shore,

Time moves forward, and the echoes of yore

Fade into shadows, where memories are tossed,

In the garden of the forsaken, love was lost.

*

But beyond the veil of this desolate scene,

Where the sea and the cliffs stand guard, serene,

There lies a promise in the poet’s pen,

That love, once departed, may return again.

*

For in death’s dominion, where silence may reign,

There’s a paradox, a mystery to explain.

As the sea winds murmur, and the waves recede,

Even death lies dead, and love may succeed.

*** *** *** *** *** *** *** *** *** *** *** *** *** ***

This is an interesting result, don’t you think? Chat GPT appears to be absolutely certain that poems should be written in four-line stanzas and that the lines should all be of equal length. Oddly, it switched to AABB rhyme, when Swinburne was using ABAB rhyme. I don’t understand that. You’d think matching the rhyming pattern would be automatic.

Obviously the vocabulary and syntax becomes much more basic. The punctuation also becomes much more standard. The specific thing Swinburne did with punctuation in his poem, if you didn’t notice, is leave out the commas between adjectives of the same level. That is, if you write, “The big old dog,” there’s no need for a comma between the adjectives because “big” and “old” are different kinds of adjectives that can only be put in that order. It sounds wrong to write, “The old big dog,” because that isn’t the right order for adjectives in English. If you write “The unusual, lovely, startling blue flower,” then the first three adjectives are all at the same rank (opinion) and could all change places, and that’s why commas go between them. The final color adjective has to come after the three opinion adjectives and that’s why there’s no comma before “blue.” Leaving out the commas between same-rank adjectives, as in “steep square slope” is a poetic device and now I am wondering whether I used this device in The City in the Lake, which I did, because I felt this was a way of creating a poetic feel because of Swinburne? That could be! I have always loved this particular poem! I will never know whether my feeling that leaving out those commas IS poetic is because of this poem, but I wouldn’t be surprised.

Meanwhile, what else?

It’s interesting that Chat GPT brings up the concept of paradox here. Other than that — actually, including that — the ideas expressed are wincingly trite and expressed in wincingly cliched phrases. “But love is a must,” ouch. That may be the worst phrase in the poem. Any high school freshman ought to be able to do better than that. Beyond that, it’s obvious that Swinburne’s poem is bleak. Chat GPT has apparently been fed enough non-bleak poetry that it doesn’t continue with unrelenting bleakness. Nope, once death lies dead, love may return — that’s Chat GPT’s final statement.

Overall conclusion: We should all pause to read a Swinburne poem now and then. Or some poem. Maybe there are calendars with monthly poems. You couldn’t fit A Forsaken Garden on a calendar page very easily, but hey, look, here’s a wall calendar with a haiku for every month. I’m amused, but I do suddenly feel that I have stumbled across an empty marketing niche. I would personally love a wall calendar that features a classic poem every month — not anything haiku length either, but something about as long as A Forsaken Garden.

Please Feel Free to Share:

The post One of my favorite poems continued by ChatGPT appeared first on Rachel Neumeier.

December 11, 2023

Pick a detail

A post from Jane Friedman’s blog: One Well-Chosen Detail: Write Juicy Descriptions Without Overwhelming Your Reader

Have you ever read a description in a book and actually stopped to say to yourself, “Dang, that’s good.” And then maybe read it again? If so, you’ve probably also read a book where you found yourself mumbling, “I really don’t need to know every detail about this guy’s library/tools/muffin recipe” as you flip a few pages to find where the story picks up again.

It takes practice to write immersive descriptions that draw readers in, without going overboard so that we bore them and lose their attention. It’s one of the more delicate elements of craft. … Master film editor Walter Murch, once said “…trust one, well-chosen detail to do the work of ten.” Part of digging deep for unique and interesting details is removing any excess wording that would weigh your story down.

More at the linked post, with examples. It’s a short post, and to be honest, I’m not crazy about the examples presented. I mean, here’s the first example presented as great description:

His close-cropped skull was indented on one side as by the corner of a two-by-four. In the crevice formed by his brow and cheekbones, his eyes glinted like dimes lost between sofa cushions.

I’m not a big fan. The first sentence is fine. The bit about eyes like dimes lost between sofa cushions strikes me as over the top. Strained. Author trying too hard. All of that. I can’t see this as “one well-chosen detail.” It looks to me like too many analogies crammed into two sentences.

So, how about this?

On a cold April day, thanks to an awful card my awful Aunt ML had sent me, I was driving down Route 52 along the Ohio River toward my home town for the first time in fifteen years. I had a six-foot plush teddy bear riding shotgun (color: Guilt Red) while I told myself not to be ridiculous, everything would be fine, and look how beautiful the Ohio River is.

That’s the opening of Lavender’s Blue by Jennifer Cruisie and Bob Meyer. I know some of you have read it. I haven’t; it’s just toward the top of my TBR pile. But look at it and think about details. What do we have? The teddy bear. The landscape, no. The car, no. The protagonist, no. But we’ve got an image of the teddy bear. I think that’s a very clever detail. We also have a feel for the protagonist’s voice. That sure didn’t take long.

Here’s a different opening that you may recognize:

On a pretty day in autumn, when the oppressive heat had at last begun to give way to days that were merely warm and the green of the more timid trees had begun to turn to orange and yellow, Kuomat broke a firm rule. This rule was one he had made a good many years ago and rigorously enforced ever since: never attempt to rob a closed carriage or a canvas-covered wagon. No matter how tempting the target, no matter how rich the apparent yield, no matter how lightly guarded it might be. If a man couldn’t see straight through a target, always let it pass.

But these wagons—there were two—posed a considerable temptation. They were each driven by a woman; they were each accompanied by four mounted men. Another woman, obviously a lady, rode a pretty little mare with ribbons braided into its mane. The lady was lighthearted and cheerful and had a sweet voice, which one could judge because she was singing. Her husband rode near her. He was obviously a lord of some degree. His vest was bright sapphire; his shirt a darker blue, almost indigo; his boots embroidered with blue and brown thread; his hair long and braided with a blue ribbon. He looked almost as lighthearted as his pretty wife, though he was not, at least, singing.

This is the opening to Shines Now, of course. How many details do we have here? No details in the first paragraph. I would say that what we have there is a broad sketch The details come in the second paragraph, and why? Because those details are important for the decision Kuomat is going to make a minute later.

It’s not just about which details you describe or how you describe those details. It’s also when you describe them, and why. Why does the protagonist notice THAT detail, and why does the protagonist notice that detail NOW? The timing is, or can be, as important as the choice of details or the words chosen to describe the details. Why the teddy bear? Because it’s eye-catching and unusual and tells us something about the protagonist and the problem.

Why the wagons and the people rather than the landscape? Because Kuomat has no reason to pay close attention to the landscape; it’s familiar and unimportant. It’s there because the story is opening somewhere and we need to know where, but we don’t need to know much about where. We do need to know about Kuomat and that he’s paying close attention to the wagons and the people with the wagons.

Sometimes description is there for plot reasons, and that can be really important. This is common, of course. That’s true of the openings above, and it’s also true throughout a book. You remember almost at the end of Tarashana, where that duel is fought beside the lake? The sunlight and clouds had to be mentioned several times before that duel took place in order for both to be important at the key moment. It would have been impossible to have that key moment happen without setting it up via description of the sky and light in the preceding paragraphs. (I hope that is sufficiently clear, while also being sufficiently free of spoilers. It’s a fine line to walk, I know.)

Sometimes description is there for some other reason. Sometimes it’s used to break up rumination or dialogue. If the protagonist is thinking about some problem, you can’t have just put in one long paragraph after another of thought. You have to break up those paragraphs with movement and description because if you don’t, that’s tiring for the reader and also you can lose the sense that the story is taking place in the world. You can break up thought or dialogue with description, just as you can break up description with thought or dialogue. It works both ways.

You can also use description to do characterization, because what the protagonist notices and any reaction to the surrounding world are characterization. I mean, we see that in Lavender’s Blue, in Shines Now, in every book, really. Ryo looks at the sky when he’s thinking, because of course he does. I mean, look at this:

A breeze came across the water, fragrant with the scents of cut hay and damp earth. The moonlight was dim, the Moon looking partly away from the summer country, but I turned on my side and gazed up at her until I felt calmer again. Then I thought again about everything that had happened.

The first sentence is there to keep the story set in the world. The second is doing the same job, keeping the story set in the world, but it’s also doing worldbuilding — metaphysics — and also characterization — Ryo looks at the sky, particularly at the Moon, because he’s upset, and he is trying to calm himself down so he can think.

Description does a lot of heavy lifting in a lot of different ways. I happen to be a fan of description, and although I may read through description fast during action scenes, when description is great, I notice and linger. Though I’m a fan of great prose, I don’t think description works as well when it’s as self-conscious as the eyes like dimes lost between sofa cushions. Is self-conscious the right word? Maybe I mean deliberately over the top, or maybe I mean too out far out of the ordinary to be credible. My point is: I don’t think anybody has genuinely thought eyes looked like or reminded them of dimes lost between sofa cushions, ever, in the entire history of the world.

Who are some authors who are especially great at description? Well:

And of course many other authors. If you have a favorite author who does especially beautiful description, drop the name in the comments!

Please Feel Free to Share:

The post Pick a detail appeared first on Rachel Neumeier.

December 10, 2023

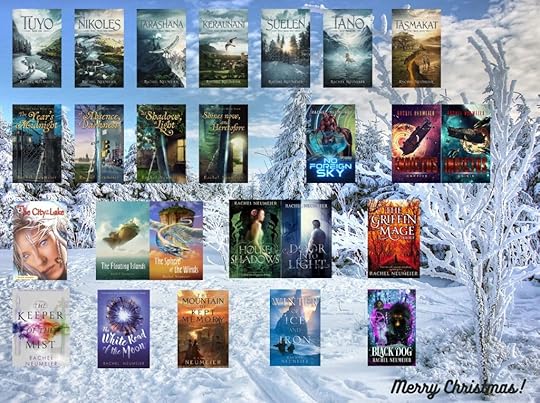

Flash sale!

If you already own copies of all my books, yay, thank you! And this is the day to pick up stocking stuffers for all your friends! Just hit “buy for others” and pick Christmas as the date and there you go, a nice handful of extra gifts, which I hope aaaaalllll your friends and relatives will enjoy.

If you’ve been waiting to pick up anything, this is a good time for the following:

Tuyo, The Year’s Midnight, No Foreign Sky, and Invictus: Captive should all be $0.99 today.

Other book in the Tuyo series, the Death’s Lady series, and Invictus: Crisis have also dropped in price; again, just for this sale.

The Death’s Lady omnibus, which contains the first three books, will drop in price to match the three individual books.

Since the Death’s Lady series is not in KU, I will lower the price for these books everywhere, though the links above go to Amazon.

The Black Dog omnibus, which contains the first three books plus the first eight shorter stories, will also drop in price, to $7.99. That is quite a deal, if I do say so myself.

This isn’t quite as much a flash sale as this term implies. Because I lowered prices by hand, I did that this past Friday afternoon to be as sure as possible prices would be down by today. And for the same reason, I will raise prices probably tomorrow, but as I will do it by hand and therefore again there may be a lag before the prices come back up. If you noticed price changes before today or a lag in price changes after today, that’s why. However, this is the day for which I was actually aiming and prices will come back up pretty soon, though not sharp at midnight tonight.

Also! I nearly forgot to release this edition in time, but I’m also bringing the Invictus duology out as a boxed set (ebook only). It should be available by the time you see this post. Amazon only, sorry, and hope I will have things arranged next year so that anyone who wants ebooks of any new releases, but not from Amazon, will be able to get those books via an alternate platform prior to the book dropping into KU.

I’m matching the price of the boxed set to the sale price of the duology, so it’s $7.99 for the set today. I’ll raise the price of the boxed set when I raise all the other prices, so probably tomorrow.

***

Meanwhile!

***

I have no control over the prices of traditionally published titles, but at the time I type this, nothing here is over $10. I’m linking to the Amazon ebooks, but all of the titles below are available everywhere.

The City in the Lake is down to $4.99, an extremely good price for a Random House title.

The Floating Islands is not particularly on sale, but if you would like it, there it is. Here is the sequel, The Sphere of the Winds.

Here is The Keeper of the Mist — this is an unusually good price. $6.99.

Here is The White Road of the Moon.

Here is The Griffin Mage trilogy.

Here is House of Shadows and the sequel, Door Into Light.

Here is The Mountain of Kept Memory. Better than typical price; $7.99.

Here’s Winter of Ice and Iron; also a good price; also $7.99

Here’s my collection, Beyond the Dreams We Know.

Please Feel Free to Share:

Please Feel Free to Share:

The post Flash sale! appeared first on Rachel Neumeier.

December 8, 2023

Cozy spaces in SF

Here’s a post by Molly Templeton at tor.com: Finding the Cozy Spaces and Fantastical Architecture of SFF

Great idea for a post! Or at least, I immediately think it might be great. Where does Templeton take this idea? The first cozy space that leaps to mind is Bag End. Sure enough, this post starts here:

“In a hole in the ground there lived a hobbit. Not a nasty, dirty, wet hole, filled with the ends of worms and an oozy smell, nor yet a dry, bare, sandy hole with nothing in it to sit down on or to eat: it was a hobbit-hole, and that means comfort.”

Yep. Where to next?

For me, it didn’t start with hobbit-holes. It started with The Wind in the Willows—specifically, the edition illustrated by Michael Hague, in which everything is rich and saturated and looks as welcoming and comfortable as a well-worn velvet sofa. I haven’t even seen a copy of this book in years and I can still see Mole and Badger and Rat and the rest; I am still shocked that I have not yet cross-stitched the words “Believe me, my young friend, there is nothing—absolutely nothing—half so much worth doing as simply messing about in boats” and hung them on the wall. …

Ah, I must admit that first, this is understandable, and second, I never actually liked The Wind in the Willows. Why not? Because as a kid, I preferred my animal characters to be much more realistic than that. I still feel some reluctance to dress little animals up and send them puttering about in boats. That’s just me, of course.

Fantasy is full of homes that a reader may or may not imagine as the author saw them. The house in The Forgotten Beasts of Eld, which I envisioned full of libraries and animals, a mountain house that was isolated but comforting, cozy and stern at once.

Oh, yes! I’m not sure I thought of this house as cozy. What a lovely story. I mean the prose. The story itself has a dark edge to it, but I will say, it’s also lovely. It’s not as easy a story as some of McKillip’s but it’s beautiful. And the animals do not dress up in waistcoats and mess about in boats, either. They do talk, but they are animals, not English gentry. I linked to the special 50th anniversary illustrated edition, which is not out yet. Soon. February. Even though I prefer ebooks, this is so tempting. A lovely edition of a favorite book? Twist my arm.

Okay, of course you should click through and check out the full post, but also, I haven’t done a post on cozy fantasy based on the panel at World Fantasy Convention. Maybe I won’t get around to that, so let me mention the most memorable line. This was Sarah Beth Durst. Everyone was talking about how to define cozy fantasy, and Durst said — this is a paraphrase — “A cozy fantasy is a gift to the reader. You, as the author, are giving this warm and fuzzy book to the reader as your gift to them, to make them happy.”

And I thought, Okay, we’re done. This panel can stop now. No one is going to top that. [Spoiler: no one did.]

Not all of Durst’s books are cozy fantasy, BUT, given this perfect statement about what cozy fantasy is to the author and what it should be to the reader, I’m not surprised that I thought Journey Across the Hidden Islands was so warm and fuzzy. Others of hers that look like they fall into the same category, but which I haven’t read, include The Shelterlings and Spark — basically any of hers that look like MG.

Looks cozy to me!

While cozy spaces may be found in many kinds of fantasy, I’m hereby going to think of the subgenre of cozy fantasy this way forever: “A cozy fantasy is a gift to the reader. You, as the author, are giving this warm and fuzzy book to the reader as your gift to them, to make them happy.”

Please Feel Free to Share:

The post Cozy spaces in SF appeared first on Rachel Neumeier.

December 6, 2023

Classics that are worth reading

Ooh! Ooh! The Count of Monte Cristo ">The Count of Monte Cristo.

My goodness, the kindle version is just $0.99. It’s unabridged. I actually especially favor the abridged version I first read, but you know what, fine. For that price, I’m picking up this ebook version.

What else?

Pride and Prejudice, which, is this a trend? is also available in a kindle ebook for $0.99. Well, in this case, I have lovely paper copies, so even though I prefer ebooks, I’ll stick with those. Also the rest of Jane Austen’s books … wow, this ebook collects all of Jane Austen’s works and it’s free? Okay, never mind. I still love my nice paper editions, but I mean.

What’s another great classic? Little Women. Not quite free, but certainly inexpensive. I haven’t read this for years, and I always pushed back a bit against certain elements, but nevertheless.

What else? Well, let’s pause to link to the post that caught my eye, which is at Book Riot: The Best Classic Books (That Are Actually Worth a Read)

I do not expect to agree with many of Book Riot’s picks because I usually don’t. I’m curious what they’re going to pick, and beyond that, I’m curious about their definition. Does a book have to be over 100 years old and still widely read in order to qualify? Does it have to be assigned in a lot of high school classes? What are the criteria? …. Doesn’t look like any criteria are stated? Well, that seems a little odd.

Well, some of these are things anybody would agree are classics, I expect. The author of the post seems to be treating this as “we all know what we mean by classics,” and I guess there are worse definitions. I’ve never heard of plenty, and some I hated, but here’s The Scarlet Pimpernel! I do like that one. I’m surprised to see it here.

A few of these were published as late as the 1980s. Nothing published in the eighties can be a classic, surely? I feel old.

Most interesting entry: The Ramayana. It turns out there are a zillion editions. The abridged this, the modernized that. I picked this edition because it’s the same one as at the Book Riot post, and I’m just trusting that person to have a reason to select this edition. Unlike everything else here, it’s not super inexpensive. but you know what, I’ve always kind of wanted to at least look at it. Maybe I’ll get a sample and see how it goes.

Entry where I recoiled: Like Water for Chocolate. I read it long ago and loathed some parts of it so much that this reaction colored the whole thing. No, I don’t remember what I hated about it. But I guess I’ll never know, because I remember the reaction well enough that I will never reread it.

Quick! One great classic that you would sincerely push on people who have missed it. Anything?

Please Feel Free to Share:

The post Classics that are worth reading appeared first on Rachel Neumeier.

December 5, 2023

Ooh, neat grammar post

Okay, fine, I know, many people are probably not as interested in grammar as I am. What can I say? This post at Kill Zone Blog caught my eye because I’m just the kind of person who instantly stops at posts like this: Phrasal Verbs, When an Adverb Is Not an Adverb

What is a phrasal verb?

Get out! Calm down. Carry on. Show off.

So a phrasal verb is a verb that combines with an adverb. Why are “out,” “down,” “on,” and “off” considered adverbs in the above phrases? They are obviously prepositions; everyone knows that if you are listing prepositions, “out,” “down,” “on,” and “off” would all be on that list. They are considered adverbs here because when a phrase has an object, then the item in question is considered a preposition: Get off the roof. When there is no object, as in Get off!, then “off” is considered an adverb. I sort of wonder now about this rule and why it works that way. Maybe the podcast Lingthusiasm has an episode about that.

Anyway, a phrasal verb creates a new meaning from the combination of two words. That meaning is separate from the meaning of the constituent words. If you say, “Carry on,” to someone, you don’t mean either “carry” or “on.” You mean something else.

This is neat! The post at Kill Zone Blog discusses the history of phrasal verbs, with a (really interesting!) observation that they haven’t always existed and that the first use of phrasal verbs was in 1154. (It was “give up.”)

Now, granted, in the 1150s, modern English didn’t exist, obviously. That was (I looked it up) Early Middle English. What was Early Middle English?

Þe Nihtegale bigon þo ſpeke

In one hurne of one beche

& sat vp one vayre bowe.

Þat were abute bloſtome ynowe.

In ore vaſte þikke hegge.

Imeynd myd ſpire. & grene ſegge.

The Nightingale began the match

Off in a corner, on a fallow patch,

sitting high on the branch of a tree

Where blossoms bloomed most handsomely

above a thick protective hedge

Grown up in rushes and green sedge.

Well, okay, there have been A LOT OF CHANGES to English since this poem, called “The Owl and the Nightingale,” was published. I guess I can believe that phrasal verbs weren’t in use as far back as that. They are certainly super common now. This post at Kill Zone Blog says that all the versions of phrasal verbs using “set” encompassed 60,000 such versions. Can that be true?

Okay, Wikipedia says The longest entry in the OED2 was for the verb set, which required 60,000 words to describe some 580 senses (430 for the bare verb, the rest in phrasal verbs and idioms).

So, pretty much true, apparently. What are some of those? Set aside, set down, set up, set off, set forth, get set. Okay, fine, there do seem to be a lot. I thought of these in about two seconds. Sixty THOUSAND still seems like a stretch. I don’t plan to go look at the OED to check, though.

Regardless, I’m not sure I knew what the term “phrasal verb” actually meant until now. It’s not something that comes up a lot.

Nor does there seem much reason to specifically look for or think about these, except that, to the extent phrasal verbs also happen to be slangy, they may or may not fit the style of a particular work of fiction. That is, “Get out!” for leave is not going to sound like slang to any readers, probably, but “Get out!” as in “You’re kidding!” or “You’re making that up!” definitely will.

So, pretty sure everyone can get along just fine without knowing what a phrasal verb is. Nevertheless, glad I saw the post. Always happy to think about grammar and language.

Please Feel Free to Share:

The post Ooh, neat grammar post appeared first on Rachel Neumeier.

December 4, 2023

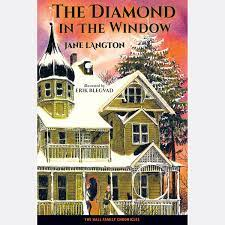

Recent Reading: A Diamond in the Window by Jane Langton

Okay, so this little book has been sitting on my coffee table for a while. I finally read it this past weekend. I think I was looking for something (a) short, and (b) as far as possible from grimdark. If those two criteria were what I had in mind, then boom, nailed it.

So this is a young MG story. I don’t have a particularly clear notion about how to judge reading level, but offhand I’d say that this story, A Diamond in the Window, would be about right for eight- to ten-year-old children, though certainly older readers may well enjoy it. It’s a very simple story with a set of interlocking problems our young protagonists need to solve.

Edward and Eleanor are living with their hardworking Aunt Lily and her brother, their nutty Uncle Freddy, and there’s a serious threat that they may soon lose the house. More importantly, long ago, their aunt and uncle had two young siblings, Ned and Nora, who vanished mysteriously. A young foreign gentleman was staying with the family at the time and also vanished, after leaving a puzzle etched into the glass of the uppermost attic room’s window. Our two young protagonists want to solve the puzzle, find hidden treasure to save the house, and also find the children who vanished long ago.

So that’s the frame story: a series of adventures following the riddles laid out in the puzzle game. Chapters dealing with ordinary life alternate with adventures, which gradually become more overtly dangerous and the children realize they’re working against an enemy. Can they find the long-vanished children? Was the foreign gentleman a good guy, courting Aunt Lily and fond of the children; or was he a bad guy? The reader isn’t going to find this much of a puzzle. This is the story where everyone who seems like a good person is a good person; there’s not a lot of subtlety, though there are questions about exactly what happened.

This story takes place in Concord, Massachusetts, and Henry Thoreau, Ralph Waldo Emerson, and Lousia May Alcott are all strongly present in the story, which includes lots of literary references and snatches of poetry. Build thee more stately mansions, O my soul / As the swift seasons roll! Leave thy low-vaulted past! / Let each new temple, nobler than the last, / shut thee from heaven with a dome more vast / till thou at length art free / leaving thine outgrown shell by life’s unresting sea! This is pretty snazzy in a story aimed at ten-year-old readers. I would have loved it when I was ten and I liked it now.

Also, A Diamond in the Window wraps around Christmas, and while it’s not centered on Christmas, I hereby declare it is close enough to a Christmas story that if you would like to read a short, charming Christmas story this month, here you go.

The story is unabashedly and thoroughly positive in its themes and imagery. It’s a little dated – it was first published in 1962 – but actually, it’s about old enough that it just comes across as historical rather than contemporary. If you remember E Nesbit’s stories fondly, then I expect you’d enjoy this story as well; if you’re giving Nesbit’s stories to a young reader, you can certainly add this to the stack because it will fit right in.

Now I kind of want to go reread something by Edith Nesbit. Did you realize her books are literally over a hundred years old now? Five Children and It was published in 1902, The Phoenix and the Carpet in 1904, The Story of the Amulet in 1906. That seems just remarkable. I bet Jane Langdon read Nesbit’s works and was inspired by them.

Please Feel Free to Share:

The post Recent Reading: A Diamond in the Window by Jane Langton appeared first on Rachel Neumeier.

Update: same old, same old, here have a story

So, yes, still December, nothing worth mentioning.

OH, except my mother is 88 today, so happy birthday to her!

But other than that, still just moving forward with Silver Circle, which yes, is almost certainly going to be a continuing project all month. That’s going to make updates boring, so I’m going to toss other stuff into these posts.

And! I was listening to a Lingthusiasm podcast this weekend, and they referred to this story:

“And Then There Were (N – 1)” by Sarah Pinsker.

All the Sarah Pinskers from four hundred realities or so get together for a Sarah Pinsker convention.

I tried to change the subject before she told me Seattle was gone in this reality too. “So why is this being held on Secord Island?”

“Everyone asks.” She smiled, showing gapped teeth. She’d never gotten braces. “It’s a sovereign island off the east coast of Canada. You know Canada?”

I nodded, wondering what variation had prompted that question.

It’s a fun story — a 24,000-word murder mystery. Click through and enjoy it.

Please Feel Free to Share:

The post Update: same old, same old, here have a story appeared first on Rachel Neumeier.