Katrina Kenison's Blog, page 8

July 22, 2015

this (good) life

A mid-summer Monday morning. After a weekend away, I’ve spent a couple of hours setting the house back to rights. Emptying jars and vases of their dead flowers, vacuuming up the scattered petals, watering plants and deadheading lilies, gathering laundry into a hamper and getting the first load going in the basement.

A mid-summer Monday morning. After a weekend away, I’ve spent a couple of hours setting the house back to rights. Emptying jars and vases of their dead flowers, vacuuming up the scattered petals, watering plants and deadheading lilies, gathering laundry into a hamper and getting the first load going in the basement.

The kitchen is quiet. Beyond the windows, which are all cranked open to their fullest on this steamy day, cardinals and blue jays vie for turns at the feeder — unaware, for the moment anyway, of the blueberries ripening on bushes just a few feet away. As always, it’s a race between me and the birds to see who will get there first to harvest the small crop. (Usually, I lose. A watchful catbird is already hopping along the top of the chaise lounge in the yard, taking stock of the bounty.)

I must confess I’m feeling a bit unsure about what to write here after a few months of not writing at all. No excuses for the silence, other than that I’ve been busy elsewhere. To offer a full “report” would be impossible for me – and tedious for you. Yet, sitting quietly on my kitchen stool, I discover there are a few thoughts that have been waiting their moment to emerge after all. I can’t say everything that’s on my mind, but I can say this: I feel softened by the season, slowed down in my thinking but perhaps a bit more raw and open in my emotions. Life has been tender and lovely and bittersweet, suffused with beauty, laughter, and tears.

There have been no big revelations, but rather countless variations on this one small truth: joy and sadness are not opposites. In fact, they co-exist, all tangled up together in the same day, the same moment, the same unguarded heart. Knowing this, it’s become a little easier for me to trust that where I am is exactly where I’m meant to be: open to what life hands me, feeling my feelings (even the painful ones), sensing what needs to be done in any given moment, doing it, and moving on.

The view that greets my eyes when I look up from my writing — a panorama of delicate, blue-tinged clouds and hazy, shadowed mountains — is silent but insistent, drawing my attention away from the screen in front of me to the pulsing, irresistible world of living, breathing things.

The view that greets my eyes when I look up from my writing — a panorama of delicate, blue-tinged clouds and hazy, shadowed mountains — is silent but insistent, drawing my attention away from the screen in front of me to the pulsing, irresistible world of living, breathing things.

So it has been for months now.

Given a choice between my computer keyboard and the weedy, burgeoning garden; between making a good meal for hungry loved ones or holing up alone with my thoughts; between taking a long walk with a friend or sitting at my desk crafting sentences, I’m pulled inexorably these days toward love and life and shared moments. The world beckons in all its intoxicating beauty. And I’m reminded with every passing shower, with every unfurling and fading daylily or blooming nasturtium, with every candle lit and extinguished, with every summer dinner prepared and eaten on the porch, with every golden sunset and every soundless moonrise, to be even more deeply present.

My friend Lisa, diagnosed just over a year ago with an inoperable brain tumor, has been having a good summer. After months of worsening symptoms last fall, she responded remarkably well over the winter to a drug that works for only a few. Her tumor stopped growing. There were no side effects. Most of her symptoms disappeared. It seemed miraculous: she danced at her son’s wedding, visited her mom in Florida, planted flowers in the spring, went to the beach with her husband, reorganized the guest room and created a photo collage in the hallway at her house.

My friend Lisa, diagnosed just over a year ago with an inoperable brain tumor, has been having a good summer. After months of worsening symptoms last fall, she responded remarkably well over the winter to a drug that works for only a few. Her tumor stopped growing. There were no side effects. Most of her symptoms disappeared. It seemed miraculous: she danced at her son’s wedding, visited her mom in Florida, planted flowers in the spring, went to the beach with her husband, reorganized the guest room and created a photo collage in the hallway at her house.

Week by week, she even began to feel like herself again. Like herself, but different, for living with a terminal diagnosis changes everything. Illness demands a subtle but profound shift of attention. No longer able to race from one thing to the next, we have little choice but to slow down. Relieved of the constant pressure to produce and perfect and display our achievements, we are free to tune in to a different frequency. Knowing time is short, we begin to take heed, to appreciate the little things, which of course are not really little at all – a hug, sunshine after rain, a cup of good coffee, a poem read aloud, a hand to hold. We have a clearer sense of what really matters and a powerful yearning to more fully inhabit the moments we do have left. Instead of taking life for granted, we’re suddenly stunned by the simple, inexhaustible miracle of being. The great, gorgeous dance is ongoing. And yet now we know this one thing for sure: we ourselves are here but briefly — and only once.

“I’m never bored,” Lisa said one afternoon from her spot on the living room couch. “I could look out this window and watch the sky forever.” I think I understood what she meant. Paying attention leads to wonder. And wonder gives birth to reverence. When life itself hangs in the balance, even the familiar becomes precious, imbued with beauty.

“I’m never bored,” Lisa said one afternoon from her spot on the living room couch. “I could look out this window and watch the sky forever.” I think I understood what she meant. Paying attention leads to wonder. And wonder gives birth to reverence. When life itself hangs in the balance, even the familiar becomes precious, imbued with beauty.

Over the course of this last year, I’ve had the incredibly moving, humbling honor of being at my friend’s side through good days and hard ones. And so I’ve also been privileged to observe this deep, essential transformation as she adjusted to living in the present rather than for an imagined future. Bearing witness to her soul growth, seeing her gradually let go of resistance and open to a quiet faith in things as they are, I’ve sensed a kind of subtle, internal shift in myself as well. Thinking about mortality, confronting the truth of it, inspires here-and-now living. Why waste any more time and energy regretting past mistakes or fearing what’s around the corner?

I notice it’s become easier to let a lot of inconsequential stuff go. Things that once annoyed me are surprisingly easy to ignore; there are more important things to think about. Worries that used to keep me awake at night no longer do. I feel less need to control, a bit more willingness to trust that my own life, too, is unfolding according to a pattern that’s perfect — but that is also beyond my understanding or design. As my yoga-teacher friend Pam used to say at the beginning of class, “Things have already worked out.”

They have. They do. They will. Meanwhile, everything I need today, I have.

A while back, Lisa asked her doctor about the possibility of returning to work this fall. Gently, he reminded her that the drug that was working so well right then could offer her only temporary respite. It was a treatment, not a cure. “I think you should use this time,” he suggested, “to go home and do the things that make you happy.”

What an assignment.

I suspect I’m not the only one who would struggle with that. Don’t most of us spend too much time trying to figure out what we should be doing and how we should be feeling, rather than listening to and trusting our own inner compass? We live in a culture fueled by the notion that happiness is “out there” somewhere — something we need to earn or acquire rather than quietly cultivate from within. Happiness, we’re led to assume, depends on our accruing certain possessions, living in a particular place, advancing in a chosen career, landing in the right relationship, being recognized for our achievements and good deeds, piling up some savings, having a clean bill of health, and going somewhere nice for vacation. Just keep reaching for it, every advertisement churned out on Madison Avenue insists, and someday, just maybe, if you work hard enough and play your cards right, happiness will be yours.

Lisa’s task these days is a bit different. There is nothing to buy and nowhere to go. There’s no job advancement or fancy vacation in the offing. There’s no magic pill that will make her brain tumor go away, either. Yet I think it’s fair to say she has fully embraced the challenge the universe has sent her. Each day, she wakes up and finds joy in living.

Everyone who loves her wishes our friend’s prognosis could be otherwise. She is held in the hearts and in the daily prayers of many, and there is no denying the sadness and pain of this journey.

But pain can also an invitation to be present. And joy, as poet David Whyte suggests, is not only a “deep form of love,” it is also “the raw engagement with the passing seasonality of existence.” In allowing herself to be joyful — here, now, and in spite of everything — Lisa is giving all of us a tremendously powerful lesson in how to find meaning and purpose in today. What matters, she reminds us by her own quiet example, isn’t what happens, but how we choose to respond. We can let today unfold. We can feel today’s feelings, solve today’s problems, enjoy today’s gifts. We can laugh and scatter darkness. We can smile and make someone else’s day better. We can choose happiness over despair, joy in the moment over fear of the future, faith in what is rather than fantasy about what might have been. To live this way isn’t just courageous, it is profoundly, extraordinarily generous.

The sun is high in the sky. It’s hot outside. And suddenly my cell phone is ringing. “Hey, we’re going swimming at the pond,” Lisa says. “Do you want to meet us over there?”

“I do,” I say. “I’m on my way.”

The post this (good) life appeared first on Katrina Kenison.

April 22, 2015

mother, daughter& a special mother’s day offer

My mom and I just spent ten days together at my parents’ house in Florida. We didn’t go anyplace and we didn’t do much. And, really, what I most loved about our time was that it was so quiet, so spacious, and so much our own. Introverts by nature, my mom and I have this in common – we are connoiseurs of companionable silence. We like to relax into our own rhythms, side by side but with plenty of breathing room between us.

My mom and I just spent ten days together at my parents’ house in Florida. We didn’t go anyplace and we didn’t do much. And, really, what I most loved about our time was that it was so quiet, so spacious, and so much our own. Introverts by nature, my mom and I have this in common – we are connoiseurs of companionable silence. We like to relax into our own rhythms, side by side but with plenty of breathing room between us.

She brought me coffee in the mornings. I made us healthy dinners, except for the night we ordered a pizza to share in bed while watching TV. Most afternoons she took a nap and I swam naked in the pool. We read a lot. And in the evenings we got into our pajamas before the sun went down and then stayed up till after midnight, catching up on the last three seasons of Mad Men.

I didn’t blow dry my hair or put on lipstick for a week. There is something to be said for letting things slide. It wasn’t exactly exciting, but it was what we each needed — time to hang out, time to read and write and think and be. There was no one to cook for or take care of, no one to worry about or sleep with. A perfect mother-daughter vacation.

At seventy-eight, my mom is moving more slowly, more cautiously than she used to. She’s not a great fan of the cane she needs for walking distances but it’s better than the alternative, better than risking a fall. She has dizzy spells and she can’t always trust her balance. She tires more easily. So, she paces herself. And when we run out of avocados or half and half, she lets me drive to the grocery store rather than insisting on going herself.

I’m moving a bit more slowly these days, too. It’s been nearly six months since my orthopedist pointed to a narrow, shadowy place on the x-ray of my hip and showed me why it hurts so much to walk up the stairs: bone on bone. I guess I’ve just needed this time to get used to the idea of a surgeon replacing my own worn-out hip joint with some new parts. It wasn’t so long ago that I was out running. Just last spring, I still thought I’d simply pulled a muscle and would be back to doing pigeon pose any day now. In September I walked 26 miles without pain and believed I was finally “over it.” But really, all I’d done was take enough ibuprofen to quiet the inflammation for a few days.

By now, I’ve grown accustomed to taking smaller steps, to the popping sound when I shift in my chair, to the nagging ache in my groin as I lie in bed at night. But I can’t say I’m used to it. This is not the “me” I believe myself to be – and so I keep being surprised to find myself hurting, hesitating to bend over to pick my socks up off the floor, easing myself into the driver’s seat of the car in slow motion.

“I never thought I’d feel this way at fifty-six!” I said to my mom, a bit of petulance creeping into my voice.

“Well I never thought I’d feel this way ever,” she replied, without the slightest trace of self-pity. “But I can’t complain. Life is so good. The only thing I can’t get used to is the idea that there’s not going to be much more of it. I can hardly believe Dad and I are reaching the end. I hate to think of all I’m going to miss when I’m gone.”

I know exactly what she means.

My writing’s been interrupted this morning by phone calls from both my sons. Jack sent me his resume to proof read. He’s got projects to finish as the school year winds down, internships to apply for, a job he’s hoping to have a crack at. Henry checked in on his lunch break, calling from Louisville en route to Ohio. He’s got three more weeks on tour and playing in a different city every night is still a thrill for him.

Nothing makes me happier than hearing from my children. I love knowing, just from the tone of their voices that, for today anyway, all is well. And I can’t imagine missing any of it, either. I can’t wait to see where my sons’ careers will take them, who they’ll meet and fall in love with, where they will land, whether they, too, will become parents. Someday, I want to hold a grandchild in my arms. And it goes without saying: I’ll want to be around to see that child grow up.

My own parents recently sold the home where my brother and I were raised. They’re building a small retirement cottage on a pond just a couple of miles from our house – close by, so we can go back and forth as many times a day as we wish. Or, as many times a day as we need to. No one’s really talking about it, but we know the chapter we’re in now will come to a close. The family plot-line is bound to become more complicated. Does anyone survive their eighties without some kind of surprise or setback?

In the meantime, I feel blessed to have my parents nearby. For the truth is, time is having its way with all of us. As my sons make their way into adult lives of their own, I have no choice but to confront the evidence of my own encroaching old age. Bodies break down and hair turns gray and minds aren’t quite as sharp as they were. My husband Steve, nine years older than I am, endures a creaky knee without complaint. He buys a senior ticket at the movie theater and adjusts his hearing aids to synch with the sound system. (At least, since he got them, our dinner table conversation has grown softer, easier, more intimate.) I dab concealer under my eyes and try to ignore the wrinkles deepening at the corners of my mouth. My mom just laughs when I confess how much I spend on a jar of face cream. She knows there’s no stopping the vicissitudes of time.

For now, though, minor aches and pains aside, we are all fine. And this mere fact of life itself, of human resilience and fortitude, is mysterious and gratifying enough. We have each other. We take care of each other. We show up for each other. The days are good, and the loving and the caring flow both ways.

And here’s the best thing: I’m a mother, yes, but that’s only half of it. When I need to, I can still just be a daughter, too. There is nothing lovelier or more precious to me right now than this. I still get to inhabit both of these roles at once, and not a day goes by that I’m not grateful.

Mother’s Day is around the corner. If you’re lucky enough to still have your mother, or if there’s a woman in your life who has ever offered you a kind maternal hand, I hope you’ll let her know how grateful you are. Mother’s Day is the perfect time to forgive your mom for being flawed and to celebrate her for being human. We may have trouble putting our love and our gratitude into words, but actions speak for themselves. (So do something nice!)

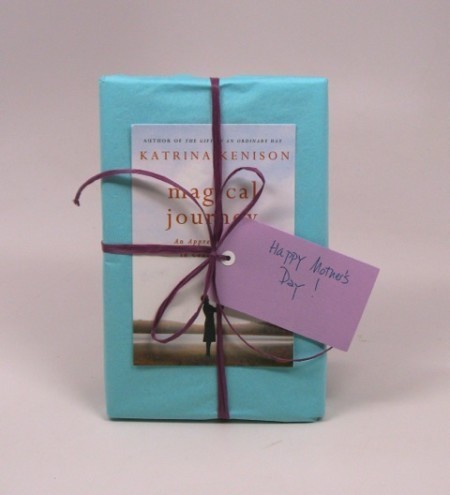

This year, in honor of Mother’s Day, I’m offering personalized, signed, gift-wrapped copies of all of my books at special discounted rates. Details below.

books!

signed, sealed, delivered, they’re yours

– in time for mother’s day

Want to order a signed book (or several) for the special moms in your life? It’s easy! Here’s how:

Want to order a signed book (or several) for the special moms in your life? It’s easy! Here’s how:

1. Click here.

(Note: This link will brings you to my own landing page on my husband’s website, Steven Lewers & Associates. Steve sells beautiful posters, note cards, and laminated nature identification guides. And because his business is all set up to take online orders and fulfill them quickly, he’s kindly offered to handle this special sale for me. While you’re there, feel free to browse his offerings, too!)

2. Want your book(s) personalized for a special person? Send me an email at klewers@tds.net. Include the book title, the name for the inscription, and any special message you’d like me to write.

3. If I don’t hear from you via email, I’ll simply sign your book(s), gift-wrap them, and have them sent to the address specified.

4. For Mother’s Day only, I’m offering a special price that includes free gift-wrap.

5. Hurry! Deadline for all orders is May 1!

The post mother, daughter

& a special mother’s day offer appeared first on Katrina Kenison.

April 11, 2015

moments of seeing

For a while now I’ve been receiving letters from readers asking if I’m ever going to collect my blog pieces into a book.

For a while now I’ve been receiving letters from readers asking if I’m ever going to collect my blog pieces into a book.

I wasn’t sure about the wisdom of that.

Would they hold up? Would anyone actually want to buy such a volume? And perhaps the question that was hardest for me to answer: Could I even bear to go back and re-read all those pieces, well over two hundred of them now? For five years I’ve been writing here as the mood strikes me, writing about whatever happens to be in my heart or on my plate, so to speak, without thinking about posterity or publication. Although I write slowly and revise even more slowly, these essays were penned in the moment: snatches of life as it was being lived, my thoughts as they came, glimpses of ordinary days, fleeting beauty, family moments, inner struggles, small revelations.

A couple of weeks ago, I decided to sit down and go back to the very beginning. I would read through all the old posts with as much objectivity as I could bring to my own work. And I would find out if the person who began writing here in August of 2009 is someone I still recognize and am interested in today.

The answer is yes – in ways that are both humbling and reassuring at the same time. And so for now I’ll just say that I’m going ahead with this project. There will be a book and I think I’ll call it Moments of Seeing: Reflections from an Ordinary Life, for that’s really what these pieces are. Of course if you’re here now, reading, you already know that.

I’m editing as I go, working toward a late spring deadline so we’ll have finished books available in the fall. The process of pausing to look back, and reading through this work one essay at a time, is emotionally akin to paging through an old photo album — a combination of sadness for what’s over and gratitude for what was, for what is, for what lasts. Already, a few days into it, I find myself reflecting on the passage of time in a different way, with perhaps an even deeper awareness of life’s fleetingness, its infinite beauty, its preciousness.

This morning I got up early. My mom and I are spending a few days alone together in Florida. It’s quiet here by the canal where her house is. There are baby mourning doves in a nest by the front door. Hot days and still nights. Bird song from dawn till dusk and bougainvillea in bloom. We have no plans for this time and so I have hours each day to work. I love taking a walk as the sun comes up, before the heat of the day settles in. And then returning to coffee, oranges, toast, and all these old pieces to edit. Here is one I came to just now, from August 2010. The last line is still true.

one good thing

A young father lay dying. Our sons, then in third grade together, had been playmates since kindergarten. When word came that Richard’s cancer had returned, I’d brought soup to the door, then lemon cake. They were small gestures, just a way to say, “I am thinking of you.” One day I stayed on to chat with Richard in the quiet house and later his wife Jane called and asked if perhaps I could come again.

“Richard is comfortable with you,” she said. “And we are going to need some help here. I think what he’d like most, really, is someone to talk to.”

So it was that in the midst of my busy life with two small children, I was invited to pause and draw close to death.

Richard’s decline was slow. There was time enough for the work of letting go. As the months went by he moved from the sofa in the sun-drenched living room to the darkened bedroom upstairs. He went from recounting anecdotes of his childhood into a tape recorder for his boys to hear when he was gone, to listening while my friend Lisa and I took turns reading the Tibetan Book of Living and Dying aloud at this bedside. Festive meals shared at the kitchen table evolved into sips of coffee and bites of cake amongst the bed pillows. There was nothing to do day after day but show up with an open heart. The lesson, I came to see, was all about being there — allowing, listening, learning to be less afraid of what might come and more accepting of things as they were.

“How are you doing?” I asked him once as the end drew near, not sure at all how to ask my real question: “How can anyone suffer so, and yet go on?”

I think often, still, of Richard’s answer, given with a smile. “As long as there is one good thing in every day,” he said, “life is worth living.”

One good thing. Most days, I lose count by breakfast time.

The post moments of seeing appeared first on Katrina Kenison.

April 1, 2015

how we spend our days

Annie Dillard wrote, “How we spend our days is, of course, how we spend our lives,” a line that resonated deeply with me when I first read it years ago.

Annie Dillard wrote, “How we spend our days is, of course, how we spend our lives,” a line that resonated deeply with me when I first read it years ago.

“How We Spend Our Days” is also the name of a wonderfully intimate monthly series in which writers (including some of my favorites) share glimpses of the private lives and processes behind the words we share with the world.

Today, I’m honored to be the guest writer over at Catching Days.

Please do come visit, read my essay, and say hello over at Cynthia Newberry Martin’s lovely site. Click here.

The post how we spend our days appeared first on Katrina Kenison.

March 18, 2015

spring thaw (inside and out)

I step out of the shower and stand dripping with my towel wrapped around me, looking out the bathroom window. The new day seems luminous, worth pausing for and gazing into even as my toes curl on the freezing tile floor.

I step out of the shower and stand dripping with my towel wrapped around me, looking out the bathroom window. The new day seems luminous, worth pausing for and gazing into even as my toes curl on the freezing tile floor.

The fields below the house are still covered with snow although the tops of the stone walls are finally visible. The sky seems a bit less austere, the sun more committed to its silent shining. It really doesn’t look like spring out there yet, with everything still bare and frozen, but something seems to have yielded. Something ineffable has changed. It’s as if the air itself is richer.

Something subtle has changed inside me, too. Everything external appears the same: upper-arm skin a bit saggy, belly soft, hair thinning and badly in need of a cut, the face in the mirror looking less and less like the younger person I still feel myself inside to be and more like my Grammie Stanchfield every day. (Those puckery little vertical lines above my upper lip! Where did they come from? Her.)

Something subtle has changed inside me, too. Everything external appears the same: upper-arm skin a bit saggy, belly soft, hair thinning and badly in need of a cut, the face in the mirror looking less and less like the younger person I still feel myself inside to be and more like my Grammie Stanchfield every day. (Those puckery little vertical lines above my upper lip! Where did they come from? Her.)

And yet, my heart is lighter.

A few weeks ago, I sat on the couch in my kitchen, brushing away tears, wondering how to respond to the most recent words of someone who has hurt me deeply. I thought I would write her a letter and instead what came out onto the page was a prayer. Not the words I needed to say to someone else, but the words I most needed to hear myself.

When the going gets tough may I have faith that things are unfolding as they are meant to.

It helps me to remember that there’s a bigger picture, a story being written that’s larger than the one I can see in front of my nose. And try as I might to avoid heartache, life will continue to have its way with me. To be human is to hurt, to worry, to wonder, to suffer, to stare at the ceiling at three a.m.

And yet, if there’s one more thing I know for sure, it’s this: whatever is happening in this moment is already in the process of turning into something else. Change is continual, and for that I can be either fearful or grateful. Today, I choose grateful.

Recently my friend Amy posted a quote I love on her beautiful blog My Path with Stars Bestrewn: “No winter lasts forever; no spring skips its turn.”

Another good, necessary reminder. For as it is in nature, so it is in life. For every dark night of the soul there is a sunrise, a brightening of the inner landscape. Smiles always follow tears. Joy will find a way, if I let it, to push up and out, through the rich, dark loam of heartache. And I am here on this earth to feel everything, to experience everything — the ups and the downs, the dark and the light, the freeze and the thaw, the drama and the denoument, the whole human catastrophe.

I can hunch my shoulders and duck my head and resist what is. (And oh, I’ve been so tempted this winter to resist, to hunch, to hide.) Or, with quiet curiosity, I can simply allow the fragile pages of my days to turn. What now? What next?

Still naked at my spot at the window, I watch a sleek copper-colored fox trot delicately across the crusty snow and hop up onto a rock, surveying her domain. Against the blanket of white, her tail flicks like a flame. I’m delighted to see her; I know this animal. To discover her here this morning is a lovely validation of life and the cyclical nature of things. For the last two springs, we have watched this beautiful wild girl as she raised her litters in in our field.

Each year as the trees bud and the matted winter grasses give way to new growth, the cubs emerge from their den beneath the rock pile, ready to meet the world.

From our own home on the hill we humans spend hours observing the goings on at the neighbors’ place. The wonder of new life never ceases to amaze. We hand the binoculars back and forth, entranced by the hunting expeditions of this watchful, dedicated mother and delighted by the cavorting pups, so hesitant at first to leave the security of their broad, flat, rock roof, but soon enough venturing further afield, bent on exploration.

From our own home on the hill we humans spend hours observing the goings on at the neighbors’ place. The wonder of new life never ceases to amaze. We hand the binoculars back and forth, entranced by the hunting expeditions of this watchful, dedicated mother and delighted by the cavorting pups, so hesitant at first to leave the security of their broad, flat, rock roof, but soon enough venturing further afield, bent on exploration.

And, always, there is drama. Five babies become four become three. Coyotes, we suspect. The first year, the family moved from one hole in the ground to another, leaving a single kit with a broken leg behind.

All through one freezing night, we fretted about the tiny fox cub, wondering if the mother would return to fetch it. In the morning, my neighbor Debbie and I intervened: we scooped up the abandoned baby and took it to a wildlife rehab center, hoping for the best. It died a few hours later. Life and death inexorably intertwined. The fragile pages turn.

Maybe this year, I think, the fox family will do better. But the mother entertains no such hope or expectation. For her, the only moment is right here, right now. The days are lengthening, warming; it’s time to prepare a den, to hunt, to assess the landscape, to get ready to begin again.

I pull on the same clothes I wore yesterday, come down to the kitchen, start coffee. And I assess my own landscape. It occurs to me that for the first time in months my heart feels unburdened, as if a stone has fallen off it and rolled quietly away.

It’s taken time, many sleepless nights, both patience and prayer, but I think I finally understand how I must make my peace with the person who has hurt me. I’m ready to accept an apology that’s not been offered, that probably never will be. I choose to forgive her anyway, unconditionally, as much for my sake as for hers.

It’s taken time, many sleepless nights, both patience and prayer, but I think I finally understand how I must make my peace with the person who has hurt me. I’m ready to accept an apology that’s not been offered, that probably never will be. I choose to forgive her anyway, unconditionally, as much for my sake as for hers.

If I can make room in my own heart for what she’s done, then I can also move toward healing – here, now, without needing to understand, without needing to be right, without needing to explain my version, without, in fact, needing anything at all — other than a willingness to let go and move on.

At last, this long hard winter is coming to an end. Soon, there will be yellow nubs on the forsythia, the first jewel-toned crocus pushing up through warming soil, robins arriving to build nests in the lilacs, a new family born in a snug hole in the field, hungry coyotes on the prowl. Endings, beginnings, life having its way — fierce and beautiful and fleeting. Always, there is loss entangled with growth. Always, there is mystery beyond human understanding. Always, we are challenged to surrender, to accept, to change.

The world beckons. Silently, somewhere deep within me, an invisible page turns. Forgiveness, it seems, goes hand in hand with faith, with humility. It is the soul-work of a winter-weary heart in spring: thawing, softening, opening to the light, to whatever is meant to be.

The post spring thaw

(inside and out) appeared first on Katrina Kenison.

February 26, 2015

when the going gets tough

When the going gets tough may I resist my first impulse to wade in, fix, explain, resolve, and restore. May I sit down instead.

When the going gets tough may I resist my first impulse to wade in, fix, explain, resolve, and restore. May I sit down instead.

When the going gets tough may I be quiet. May I steep for a while in stillness.

When the going gets tough may I have faith that things are unfolding as they are meant to. May I remember that my life is what it is, not what I ask for. May I find the strength to bear it, the grace to accept it, the faith to embrace it.

When the going gets tough may I practice with what I’m given, rather than wish for something else. When the going gets tough may I assume nothing. May I not take it personally. May I opt for trust over doubt, compassion over suspicion, vulnerability over vengeance.

When the going gets tough may I open my heart before I open my mouth.

When the going gets tough may I be the first to apologize. May I leave it at that. May I bend with all my being toward forgiveness.

When the going gets tough may I look for a door to step through rather than a wall to hide behind.

When the going gets tough may I turn my gaze up to the sky above my head, rather than down to the mess at my feet. May I count my blessings.

When the going gets tough may I pause, reach out a hand, and make the way easier for someone else. When the going gets tough may I remember that I’m not alone. May I be kind.

When the going gets tough may I choose love over fear. Every time..

The post when the going gets tough appeared first on Katrina Kenison.

February 15, 2015

“thank you”

“If the only prayer you ever say in your entire life is thank you, it will be enough.” ~ Meister Eckhart

“If the only prayer you ever say in your entire life is thank you, it will be enough.” ~ Meister Eckhart

If you had visited my friend Lisa last week, the first thing you would have seen upon entering her living room is a large bright mobile hanging near the window – a thousand and one paper cranes strung on thread and suspended from a curved branch.

The cranes were created over the last couple of months by visitors to the Hilltop Café, a small coffeehouse at the farm up the road from the Pine Hill School, where Lisa has been a beloved kindergarten teacher for many years. Anyone who came into the cafe this winter to eat or grab a coffee to go was invited to pause for a few moments to craft an origami crane and send healing thoughts Lisa’s way. The result: the beautiful wall hanging in her living room. Love made visible.

The phrase “it takes a village” comes to my mind many times a day lately, for that’s what we have here, a village of caring friends and thoughtful strangers who show up in all sorts of ways, and who do what they do in a spirit of love. There have been months of beautiful dinners, massages, flowers, stories written and pictures painted and cards sent; donations large and small from across the land; photos and memories shared, housecleaning, rides given, family and friends arriving to brighten the days. An abundance of much-needed, much-appreciated assistance, care, and concern.

No one can change Lisa’s diagnosis. And there’s no denying the challenges she faces each day: pills to take and transfusions to endure and a new port to contend with. There are side effects to every medication. There is the unknowable future. There is no cure. But there is always healing, and healing is what she’s choosing to focus on. There is also the beauty of the present moment. I think of it as a bubble of grace, this sacred territory in which goodness and gratitude co-exist with illness.

Some day, I know I’ll look back on these winter days and the hours I’m privileged to spend with my dear friend. And the prayer I’ll say then is the same one I’m saying now: “Thank you.” I’ll remember the record-breaking snows of 2015, the frigid cold, the racing start I need in order to get my car up the steep, icy hill to her house, and also the warmth that envelops me as soon as I walk through the door. I’ll remember the hours we’ve spent on the couch, talking about everything. I’ll remember fires in the fireplace and wedding plans (her son will be married next week, and Lisa will be there, having the first dance with her boy). I’ll remember reading Anne Lamott out loud and how we got laughing so hard tears came to our eyes. I’ll remember the two of us doing her PT exercises together on the bed. I’ll remember afternoon meds and Reiki and cups of turmeric-ginger tea. I’ll remember a flock of handmade paper cranes taking flight.

After a rough holiday season, Lisa’s medical team decided to try a new medication to reduce swelling from the tumor in her brain. She is one of the lucky ones: the drug has given her a window of feeling better – much better. It’s allowed her to take a short walk in the snow, to go downtown for lunch, to do some of the things that nausea and seizures and headaches have kept her from enjoying for months.

After a rough holiday season, Lisa’s medical team decided to try a new medication to reduce swelling from the tumor in her brain. She is one of the lucky ones: the drug has given her a window of feeling better – much better. It’s allowed her to take a short walk in the snow, to go downtown for lunch, to do some of the things that nausea and seizures and headaches have kept her from enjoying for months.

“I don’t know where my will has gone,” Lisa said many times through the fall, as the hours ticked by and she found herself too weak and too weary get up off the couch. Now, she’s making up for lost time. And what is she doing with this unexpected gift of energy? Writing thank you notes. Given a day, a moment, an opportunity to ask, “What now?” my friend is choosing to affirm the abundance in her life. She is choosing to say “thank you.”

And then, as more and more snow piled up outside last week, and as the temperatures hovered around zero, Lisa asked her husband to carry all their boxes of photos up from the basement. Grateful to be up and about at last, she embarked on an ambitious journey through the past.

When I arrived last Monday, every surface in the dining room was covered with pictures; there were more boxes on the floor, a new photo collage artfully arranged on the refrigerator door, an arrangement taking shape on the table of pictures to be hung on the wall going down the hallway.

So many memories! And such a reminder that life is long, full of twists and turns, love and loss, laughter and forgetting. Here was her husband Kerby, today a distinguished, white-haired eighth grade teacher; once, long ago, a seven-year-old boy in shorts and tap shoes, ready to twirl his somewhat heftier partner. Here, Lisa, a fresh-faced young mom with her three tow-headed little boys on a summer afternoon.

Here, her son Morgan in his senior year of college, just off the lacrosse field, grinning, his arm around his lovely girlfriend – a photo so full of life and energy that, thirteen years later, it’s still hard to fathom that this was to be his last day; or that after saying good-bye to his family that night, he would be brutally murdered while trying to help a young team mate who was being beaten up on a street near the Bates campus. Here, Lisa and her beloved horse Bentley, gone himself just three months ago, but a soul gift in that time of great sorrow, around whom Lisa began to construct another life, one that included a new home for her and Kerby, where she could ride and create her remarkable summer camps for children. Out of that deepest grief: more love.

Together, we began sorting the stray photos into envelopes: good times, boyhood, early days, cherished animal friends, married life, family. . . . We studied a photo of her on a long-ago beach, stunning in her bathing suit, legs long and lean, hair wind-whipped. Gorgeous. “There’s no going back there,” I said. “Not for any of us.” And we agreed: it’s ok. No one gets to go back. But we all have a choice about how we inhabit our now.

Together, we began sorting the stray photos into envelopes: good times, boyhood, early days, cherished animal friends, married life, family. . . . We studied a photo of her on a long-ago beach, stunning in her bathing suit, legs long and lean, hair wind-whipped. Gorgeous. “There’s no going back there,” I said. “Not for any of us.” And we agreed: it’s ok. No one gets to go back. But we all have a choice about how we inhabit our now.

At one point Lisa looked up, turning to gaze out the window where the afternoon sun was turning the distant snow-covered mountains shades of rose and violet. “Even if I knew this was to be my last week,” she said, “I don’t think I’d want to be doing anything else.”

And in that moment, I looked at my friend with something that approached awe. She could have been regretting every single loss in her life, of which there have been many. Instead, she was choosing gratitude for all the good, for all the abundance, for all the love. What better way to pass a winter afternoon?

In the kitchen, there were enticing smells – dinner coming together. Risë, the nurse who arrives early each morning as Kerby leaves for work, was making pasta sauce.

In the kitchen, there were enticing smells – dinner coming together. Risë, the nurse who arrives early each morning as Kerby leaves for work, was making pasta sauce.

For the last month, Risë has been living in the guest bedroom at our house and spending days with Lisa, doing whatever needs to be done — organizing her medications, driving her to doctor’s appointments, making sure there’s something good to eat on the table on the nights that friends don’t deliver meals to the door. (And, on the days when we’ve all been completely snowed in, Risë has organized the linen closets at our house; she’s made sourdough bread, folded laundry, chopped vegetables with me for soup.) Sometimes, I pause and wonder: how did we get so lucky? I find myself praying all the time these days. “Thank you.”

Gratitude turns what we have into enough, and more. It turns denial into acceptance, chaos into order, confusion into clarity…it makes sense of our past, brings peace for today, and creates a vision for tomorrow.” ~ Melody Beattie

Lisa and I are both journal keepers. Lately we’ve been talking about putting all our diaries and random writings together and burning them, something we’ve both thought about for years but haven’t quite been able to do. And yet, the words written in our ratty old notebooks were never meant for others’ eyes. They were outpourings and rants, inner struggles brought to the page for resolution, private conversations with our most pathetic, angry, confused, uncertain selves. Sending them up in flames, we suspect, will be a kind of spiritual cleansing. She’s pretty much ready to go for it, and I’m pretty much ready to join her.

So, we’ve been envisioning a little ceremony — a few kind words of remembrance and a good strong fire. Lisa’s already started going through her writings. The other day, she told me there was one journal she’d found and decided to keep: the gratitude journal I’d encouraged her to start during a particularly dark time years ago.

“I found an entry in there about making Morgan dinner,” she said, “and how happy it made him. Reading that, I wasn’t sad. It made me happy to remember it.”

And with that, Lisa was inspired to begin another project: writing a new gratitude journal. She found a simple, red blank book and gave that one to Risë, suggesting she might wish to begin a gratitude journal of her own. (Later that night, I asked Risë if she’s ever had a cancer patient encourage her to keep a journal of each day’s blessings. She has not.)

I’ve got a new notebook, too. In it, I’m already praying. “Thank you.”

notes

*Heartfelt thanks and hugs through the ether to all of you, my dear readers, who have reached out to Lisa over these last months with notes and donations to our fundraiser. (Click on the link to learn more about Lisa’s journey.) Your kindness is extraordinary, and these gifts continue to help enormously.

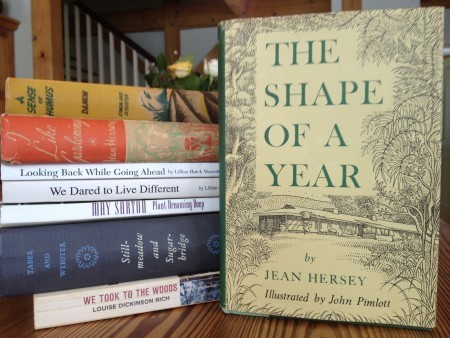

*Congratulations to Jeanne M., winner of the vintage copy of The Shape of a Year by Jean Hersey. I know I’m not the only one who loved reading all the comments last week! What a book list you’ve generated. My next project: compile all those wonderful suggestions into a list that we can all refer to easily. Thank you so much for your suggestions — many old favorites here, and many more books I’m eager to search out.

The post “thank you” appeared first on Katrina Kenison.

February 5, 2015

the shape of a year and a book to win

It’s snowing again, for the third time in a week. In New England, and certainly here in our part of New Hampshire, it’s a season of enforced respite from the comings and goings of our busy everyday lives. We can fight the weather (not much of a contest there!), or we can embrace the challenge of an uncompromising northern winter, layering on fleeces and wool socks, planning ahead, slowing down. I choose to acquiesce to this season of storms, keeping more food in the refrigerator, making pots of soup and chili that last for days, shopping less, driving less, snowshoeing more, writing more, reading more, gazing out the window more.

It’s snowing again, for the third time in a week. In New England, and certainly here in our part of New Hampshire, it’s a season of enforced respite from the comings and goings of our busy everyday lives. We can fight the weather (not much of a contest there!), or we can embrace the challenge of an uncompromising northern winter, layering on fleeces and wool socks, planning ahead, slowing down. I choose to acquiesce to this season of storms, keeping more food in the refrigerator, making pots of soup and chili that last for days, shopping less, driving less, snowshoeing more, writing more, reading more, gazing out the window more.

This morning, it’s pretty wild outside — a bitter, relentless wind drives vast, swirling curtains of powder across the meadow and sends silent clumps of snow crashing from tree limbs. With the temperature dropping steadily and the snow already hip deep, it would be easy to view yet another four or six or sixteen inches of snow as an annoying inconvenience. But I’m seeing this latest storm as a muffled blessing, an invitation to stay put today—no place to go and nothing to do, at least until the roads are cleared.

This morning, it’s pretty wild outside — a bitter, relentless wind drives vast, swirling curtains of powder across the meadow and sends silent clumps of snow crashing from tree limbs. With the temperature dropping steadily and the snow already hip deep, it would be easy to view yet another four or six or sixteen inches of snow as an annoying inconvenience. But I’m seeing this latest storm as a muffled blessing, an invitation to stay put today—no place to go and nothing to do, at least until the roads are cleared.

Looking up from my stool in the kitchen, I spot the empty bird feeder swinging in the wind and a sturdy cardinal, all puffed up and hunkered down in a nearby snowdrift, bright as a jewel against the blanket of white, patiently waiting for his breakfast. We all need to eat.

I slip on Steve’s tall black boots to trudge out and fill the birdfeeder, scattering some extra nibbles along the top of the snow-covered stonewall — a sunflower seed buffet for the squirrels and the jays. A pair of chickadees arrives before I’m even back to the door, the two of them too hungry to be shy. I stand there quietly for a moment, close as I dare, to watch them take turns plucking seeds from between the wires. But my fingers are already numb with cold. I’ll skip the long walk today.

I slip on Steve’s tall black boots to trudge out and fill the birdfeeder, scattering some extra nibbles along the top of the snow-covered stonewall — a sunflower seed buffet for the squirrels and the jays. A pair of chickadees arrives before I’m even back to the door, the two of them too hungry to be shy. I stand there quietly for a moment, close as I dare, to watch them take turns plucking seeds from between the wires. But my fingers are already numb with cold. I’ll skip the long walk today.

Back inside my cozy kitchen, second cup of coffee in hand, I pick up my book.

Back inside my cozy kitchen, second cup of coffee in hand, I pick up my book.

More and more these days, I want to close my computer, silence my phone, and steep in the silence. And yet, being quiet in both body and soul can be a challenge – especially given the countless distractions, obligations, needs, and desires that tug at the coat sleeves of my attention each day.

And so, I’ve been giving myself this small gift of time, a few minutes of uninterrupted reading before the work of the day begins. I have a stack of new books waiting on the bedside table and I’m nearly done with Anne Lamott’s wise and funny essay collection, Small Victories. But in the silent expansiveness of these winter mornings, as I set a tone for my day, I’m drawn not to the latest literary releases on my shelf or to the novel half-read on my iPad, but to a modest, gently worn, long out-of-print memoir called The Shape of a Year by Jean Hersey.

I have a special place my heart for such chronicles of daily life as it was once lived by women who have long since left this earth. (May Sarton’s Plant Dreaming Deep is perhaps my favorite, but there are others, too, memoirs by Louise Dickinson Rich, Florida Scott Maxwell, Gladys Taber, and Madeleine L’Engle.) These graceful, unaffected writers feel like soul friends to me, kindred spirits who are still alive on the page, their own ordinary days eternally vivid and fresh simply because they took the time to notice, to watch, to reflect, and to write things down.

In a world that’s constantly urging me – all of us — on to the next new thing, these quiet, by-gone voices are rarely heard. Yet there’s a certain pleasure to be found in turning back instead of pressing forward, and in discovering the worth and beauty in a book that’s old, unknown, unsung, unavailable on any book seller’s front table. (Maybe I also like the idea of some yet-to-be-born woman sitting at her kitchen table on a winter’s morning fifty years from now, reading a time-worn copy of The Gift of an Ordinary Day, and feeling a stirring of kinship with its long-gone author.)

And so it is that this is humble lineage feels precious to me, a reminder that throughout the ages we humans have expressed our love for the world by noticing it. No matter what century or country we inhabit, we learn, each of us in our own way and our own time, to nourish our souls by attentiveness.

It’s true that our mortal lives are fleeting. We don’t last, but the words we commit to the page do. Ten years ago, when my husband and I bought the old summer cottage that became our first home in New Hampshire, The Shape of a Year was one of many forgotten volumes left behind in the bookshelves here. Although the cottage itself eventually had to come down, I couldn’t part with all those dear, dusty, old books — relics of other lives, other summers, other readers who must have whiled away August afternoons on the screened porch that would soon exist in memory only. I packed the books away before the wreckers came.

Much later, when our new house was finally built on the site of the old, I put a few of them back on my shelves, with a sense that I was honoring the past by inviting these abandoned volumes to reside with us in the present. Recently, while searching for some other memoir, I found myself pausing with Jean Hersey’s book open in my hands. It was a January afternoon in the year 2015. And, too, it was January 1967. Another time, another woman, another life.

Quiet and smooth, fresh and untouched, the new snow lies across our meadow. Its pristine surface catches the sunlight, and tree shadows stretch like great blue pencils over the unbroken white. The snow folds gently over rocks and hummocks half concealing, half revealing a variety of different shapes.

So lies our year ahead, its basic ingredients sun and shadow and suggested shapes of things to come. I wonder what we will do with this year, what it will do with us, and what together we and life will create during the twelve months ahead.”

The words captured my attention, as if I were being summoned to stop what I was doing and allow time to fold in upon itself. And what I discovered, reading on, was something entrancing and lasting between the faded covers: an intimate record of a singular life well lived. A deep awareness of what matters and of what endures — the pulse of nature, our human yearning for connection, the turning of the seasons, the patterns beneath the surface of daily life, the unadorned beauty of simple prose.

On this blustery February morning, with our own birds well supplied with seed, I accompany my new friend into her long-ago February observations. These winter mornings, she writes, “are like opals, soft, milky white and pink around the edges.” Yes. I know those colors, too. Across the span of years, a hand extends for mine. I take it, and read on:

On this blustery February morning, with our own birds well supplied with seed, I accompany my new friend into her long-ago February observations. These winter mornings, she writes, “are like opals, soft, milky white and pink around the edges.” Yes. I know those colors, too. Across the span of years, a hand extends for mine. I take it, and read on:

It’s a joy to feed the birds during the winter. In a blizzard we are literally a lifeline to these lovely creatures. You get to know the different kinds and sometimes certain birds themselves. One particular chickadee is my friend. Each day I’m especially pleased when he comes for his sunflower seed. He perches near me while I scatter food.”

And with that, our bond today is secured – she’s watching her birds as I look out for mine. Not much happens in The Shape of a Year, beyond one woman’s close observations of the world as she finds it. The world I live in today is much changed from Jean Hersey’s world of 1967, but the things that matter remain the same: compassion, love, nature’s eternal rhythms, shared laughter, a sense of wonder. My new friend writes about the very things I notice.

The scent of February: “February air has a flavor all its own. It is not only crisp and cold and tingles in your nose when you go walking, but something more. We hear a lot about spring air, summer air, and that of autumn. But do pause briefly and appreciate the air that nature sends us in midwinter.”

A full moon on snow: “It was beautiful outside. Shadows cast by moonlight weave their own magic spell. Moonlight was streaming over the garden where seeds will sprout and grow, where vegetables will nourish and fragrant flowers bloom. It seemed to me as I stood looking out that many of the things we get all stirred up about have less value in the overall pattern than the sight of a full moon shining down on a sleeping garden, or tangled up in the bare branches of a maple tree along a stone wall.”

The awkwardness of change: “A restlessness in our bones responds to the wild restless winds of the month. The wind in January awakens a kind of strength. February storms rouse our spirits and hearten our defenses. But a tearing March wind howls through us exposing lonely and unfamiliar areas. We are not at home with the strange impulses and wild, undisciplined thoughts that go blowing through our minds and emotions. Some days, confidence shrinks to the size of a pea, the backbone feels like a feather. We want to be somewhere else, and don’t know where; we want to be someone else and don’t know who.”

Time marches on, the details and demands of our daily lives evolve, the laptop I’m typing on bears little resemblance to the typewriter that I imagine must have sat upon Jean Hersey’s desk. And yet, the inner life, the quiet work of seeing deeply into the nature of things, the familiar duties that accompany each hour of a writer’s day and each change of season – these things are a constant thread, connecting us. We water plants, mix pancake batter for breakfast, wrestle with a paragraph till the words are just right to the ear, relish an evening spent alone reading in bed. If we lived next door to each other, we would be friends. Instead, for a few minutes each morning, we share a silent conversation, a kinship that transcends time and space.

And it occurs to me that what draws me to this thoughtful, introspective woman, and to her unassuming record of a long-ago year, is something as simple and as challenging as this: a mutual if unspoken yearning to heed Mary Oliver’s instructions for living a life. “Pay attention, be astonished, tell about it.”

enter to win your own copy

I have located one gently used but perfectly lovely copy of Jean Hersey’s special book to share with you. To enter to win The Shape of a Year, leave a comment in the comments section below. I’d especially love to hear if there’s an old or little-known book that holds a special place in your heart. Or, you can share a glimpse of your winter days. Or just say, “Count me in.” I’ll choose a winner, selected at random from all the comments, after midnight on February 14. As always, I love hearing from you. (note: book titles are affiliate links)

The post the shape of a year

and a book to win appeared first on Katrina Kenison.

January 24, 2015

to love like a grandmother

“Break a vase, and the love that reassembles the fragments is stronger than that love which took its symmetry for granted when it was whole.” ~Derek Wolcott

“Break a vase, and the love that reassembles the fragments is stronger than that love which took its symmetry for granted when it was whole.” ~Derek Wolcott

I was not the best little girl. Shy, bookish, solitary, dreamy, not athletic, a bit chubby, I was certainly no trouble-maker. At school, a year younger than most of my classmates, utterly clueless about fashion, part of no clique and always two steps behind on the latest trend, I kept my head down and my mouth shut, hoping not to be noticed. At home, where repercussions for misbehavior were swift, I did as I was told and tried to stay out of the way. I read a lot. I wrote. I colored, painstakingly, in a beloved, finely drawn coloring book with my colored pencils. I sat contentedly on the floor of my bedroom, making tiny dolls from wooden clothespins and sewing clothes for them.

But the truth is, at my grandmother’s house, I pushed the limits. When my brother and I were little we spent many weekends with our grandparents, who were happy to give my young, overworked parents a break. My grandmother who, at the age I’m remembering her, was just a few years older than I am now, seemed to me at once frail, elderly, and immortal. She was tiny, less than a hundred pounds, with feet the size of a small child’s. Asthma sometimes forced her to lie down on the couch in the middle of the day, wheezing with each breath. Her heart was weak. She was always in and out of the hospital, for gallstones and kidney stones and I don’t know what else. And yet, because I’d never known anyone to die, it never occurred to me that someday she would. I couldn’t imagine her other than as she was, up in the morning before anyone else, her breath rattling a bit in her chest, frying eggs at the stove, tending to her home, to my grandfather, to us pesky children with our endless questions and demands.

My grandmother – Wilda was her name — was a housedress-and-apron kind of grandmother. There were always cookies in the jar, a dried up Lipton tea bag by the sink waiting to be used a second time, a half-stick of butter softening in a dish by the stove. She kept her collection of china tea cups on proud display in the dining room, a stack of magazines — The Ladies Home Journal, Family Circle, and McCall’s — by her chair, recipes copied by hand into a falling-apart notebook, antimacassars tacked into place along the back of the sofa, hard butterscotch candies in a covered glass dish, Laurence Welk on the TV, witch hazel and a big blue jar of Vicks and a flesh colored bottle of calamine lotion in the bathroom cabinet, lace-trimmed hankies in the top right dresser drawer, a pack of Wrigley’s spearmint gum down at the bottom of her black handbag, amidst the lipstick-stained tissues. (Gum that she would generously dispense, though always by the half piece, to make it last longer.)

I see her now in my mind’s eye, this small, kind, busy woman, pushing her huge brown Hoover vacuum across the flowered carpet, it’s bright headlight illuminating the path ahead. There was always a seriousness to her work, care taken but no fuss made, simply another dinner to be prepared, more dishes to wash, a shopping list to be written out on the back of an envelope.

I remember standing by her side in the vast Baptist church she and my grandfather attended, smelling her powdery smell, listening to her sing the hymns in a high, thin, warbly voice, feeling at once terribly bored and completely safe. I remember five-minute trips in her boat-sized white Oldsmobile – she could barely see over the wheel, despite the extra height afforded by a square pillow she sat upon to drive — to the little store down the road. There, my brother and I would pester her for treats – something we never would have dared with our parents — and she would always give in, extracting quarters from her change purse to pay for our orange popsicles and Pixie Stix and cheap plastic toys.

I loved her. And yet.

When I came across this beautiful line by Derek Wolcott yesterday, the first thought that came into my head was a memory of the evening I broke my grandmother’s antique, hand-painted kerosene globe lamp that had once belonged to her mother. The lamp, one of the only things that had accompanied my grandmother throughout her modest life, from her childhood in a small town in the Maine woods to the tidy ranch house where she would end her days, had been wired with electricity for the 20th century. It was delicate and beautiful, her most precious, most cherished possession.

My brother and I had had our after-dinner baths. We were probably still dripping, damp skin sticking to our pajamas, revved up and acting silly because, at our grandparents’ house, no one cared if we made noise or danced like wild little savages in the living room. He was three, a toddler imitating his big sister; I was six, old enough to know better than to swing a big wet towel around over my head like a lasso. My grandmother asked us, kindly I’m sure, to stop. We pretended not to hear. She asked again, firmly this time, warning, “Something is going to get broken.”

Something did. I whipped my towel around with a mighty flourish, one last time. It caught the lamp and sent it flying. The glass shattered, scattering everywhere. My grandmother burst into tears.

I remember little else about that night, except that there were no raised voices, or spankings, as there would have been at home. I was not shouted at or punished, though I fled down the hall to my bed, in tears myself. There was no hope of reassembling the fragments. From behind the closed door, I could hear my grandmother weeping, the tinkle of glass being swept into the dustpan, the roar of the Hoover getting up the last bits.

As I tell this story now, my heart still hurts to recall it. The lesson, too, is fresh and raw; in fact, I am learning it anew these days. And it has nothing to do with obeying my elders or refraining from rough-housing in the living room.

My grandmother’s beautiful heirloom was shattered, but her love for me was intact, not even chipped or cracked. In the morning, there was no mention of the lamp I had broken. Instead my grandmother took me into her arms and reassembled the fragments of me, gluing my broken, heartsick, remorseful, self back together.

I did not know, at six, whether I was a good person or not.

I was very much afraid that I might not be very good after all, that I wasn’t worthy of love — or even of the Pixie Stix and gingersnaps and half sticks of gum my grandmother gave me. I did not know that good people say and do stupid, reckless stuff, which does not make them bad, only foolhardy. I did not know that a broken thing doesn’t matter nearly as much as a broken heart, or a broken word, or a broken trust. I did not know that the glue that mends a broken relationship is forgiveness. Or that in choosing to forgive someone who has wronged or hurt us, we do indeed reassemble a shattered love into a stronger whole.

I did not know when I was six that, that fifty years later, with my grandmother long gone from this earth, I would sit in my kitchen on a snowy winter day thinking about her, yearning for the kind of open-hearted pardon she offered me so long ago. For, although I do now believe in my own essential goodness, I can still, unwittingly, break things that are precious. I can be wrong and graceless and dumb. Recently, I wrote and sent a letter I should have kept to myself; the emotional equivalent of swinging a towel in the living room. I caused a special friend, a cherished friendship, to suffer.

Whether this particular vase can be reassembled by love I don’t know. I can only do my best to gather up the broken pieces, to make amends, to wait patiently and see. But in the meantime, I want to do a better job of loving like my grandmother, quietly and wholeheartedly — without feeling so compelled to have my say or my way, without expectation or attachment.

To love like a grandmother means to offer pardon without need of an apology. It means to love with no strings attached or conditions to be met. To love like a grandmother is to know: we all make mistakes and we all need to be hugged and held and forgiven the errors of our clumsy ways. To love like a grandmother is to remember that no one gets out of bed in the morning with the intention of sending a lamp flying through the air or doing harm to someone we love, and yet our lives and our needs inevitably bump up painfully against the lives and needs of others. A wrong word, a rash action, a hurtful gesture, or a simple lapse of attention – we are all guilty. To love like a grandmother means to tenderly forgive these human errors in others, in ourselves. It is to see the beauty and the value in the vase that’s been broken and painstakingly, imperfectly repaired.

The post to love like a grandmother appeared first on Katrina Kenison.

January 6, 2015

in awe of the subtle

I am perched on a stool in my friend’s kitchen, looking out at the same mountains I see from my own kitchen stool on the other side of town. A reverse view. On the sill above the sink, a row of single paperwhites rising out of cobalt blue jars. Beyond the tiny star blossoms, on the other side of the window, a few flakes of snow dancing through the air. And then, in the time it takes me to type a sentence and look up again, the storm quickens, the dance becomes a fury, and the solid, slumbering mountains disappear behind a swirling veil of white.

I am perched on a stool in my friend’s kitchen, looking out at the same mountains I see from my own kitchen stool on the other side of town. A reverse view. On the sill above the sink, a row of single paperwhites rising out of cobalt blue jars. Beyond the tiny star blossoms, on the other side of the window, a few flakes of snow dancing through the air. And then, in the time it takes me to type a sentence and look up again, the storm quickens, the dance becomes a fury, and the solid, slumbering mountains disappear behind a swirling veil of white.

My friend sleeps in the bedroom down the hall. When she awakens, I’ll be here. We’ll have a late breakfast together, drink tea, listen to the wild wind and watch the snow fall. I suspect there is comfort for both of us in that.

A sentence sent by another friend over the weekend about sums it up: “Sitting silently beside a friend who is hurting may be the best gift we have to give.”

Sitting silently is something I’m always happy to do. The gift, needless to say, goes both ways. We are all hungry for silence. To dive down, to find the beauty in a moment’s passing, to inhabit time with a breath, to be fully present to another’s beating heart, is both an act of perception and imagination. I love that even a time of stillness can be shared through the gift of presence; that silence, too, speaks a language of caring and connection.

At my own house, we’ve put the holiday decorations away and stripped the rooms down to a bare winter austerity that pleases me. I relish this gradual return to a simpler existence. There is a beauty in the empty surfaces, relief in the absence of stuff, a serenity and quiet order that meets my January soul where it is.

And, although I rarely (in fact, never!) write two blog posts in a single week, I want to offer a brief counterpoint to my reflections the other day about emptiness. Over these last few days, I’ve been re-filling my own empty pitcher, taking time to linger, to look, to savor. So here, now, allow me to share with you a small bouquet of words and images that have spoken to me – inspiration, perhaps, to look more deeply into these quiet winter moments, to find the beauty in the season, and to find within our own hearts a stirring of inspiration for change, renewal, and rejuvenation.

What better time than the frozen month of January to ponder the quiet miracles of everyday life? What better moment than this to remind ourselves that the potential for healing is always at hand, and that we begin to access it as soon as we say “yes” to whatever is true in this moment. Whether we like it or not, whether it’s what we expected or not, we can still say yes. And suddenly, with that small gesture of acceptance, we discover not only that life is manageable after all, but that our own spirits are more resilient, more compassionate, more capable of gratitude and joy than we ever imagined.

As yoga teacher Rodney Yee has said, “Train yourself to live in awe of the subtle, and you will live in a world of beauty and ease.”

Indeed. In celebration of the subtle, these offerings:

The rain came down all day yesterday, and then, as the skies cleared and darkened, temperatures plummeted. Early this morning, my husband whistled for the dog, pulled on his boots, and stepped outside, camera in hand, in awe of the subtle. Here, just a couple of his photographs, as clean and spare as lines of poetry.

The rain came down all day yesterday, and then, as the skies cleared and darkened, temperatures plummeted. Early this morning, my husband whistled for the dog, pulled on his boots, and stepped outside, camera in hand, in awe of the subtle. Here, just a couple of his photographs, as clean and spare as lines of poetry.

Michael Grab devotes his days to the art of stone balancing; creating precarious formations in often turbulent conditions is for him both a form of prayer and practice, meditation and exploration, art and serendipity. His work is beautiful, fleeting, almost beyond description.

As Michael explains the process of contemplative stone arrangement, “I feel something divine when I practice. Immune to a complete explanation. Oftentimes I feel as if I’m glimpsing some kind of truth as I dance among an orchestra of vibration and poetic form. . . . Stone balance for me is, in a sense, my yoga. . .

As Michael explains the process of contemplative stone arrangement, “I feel something divine when I practice. Immune to a complete explanation. Oftentimes I feel as if I’m glimpsing some kind of truth as I dance among an orchestra of vibration and poetic form. . . . Stone balance for me is, in a sense, my yoga. . .

“It is about dissolving the duality of myself and my environment. I must become the balance. . . . There is nothing easy about it. It can frustrate me to my limits. And then I learn. Or it can reveal magic beyond limits, and I learn.”

“It is about dissolving the duality of myself and my environment. I must become the balance. . . . There is nothing easy about it. It can frustrate me to my limits. And then I learn. Or it can reveal magic beyond limits, and I learn.”

Michael has just posted a video featuring clips of his 2014 work. I’ve watched it several times, mesmerized, grateful for the transcendent, transient beauty of his extraordinary creations. Treat yourself to these 10 magical minutes.

Each Saturday morning, I look forward to spending some quiet time immersed in the weekly online newsletter of Krista Tippett’s popular, wide-ranging radio show On Being. This week’s written edition proved the perfect antidote to the vague melancholy with which I found myself greeting the new year.

Quaker writer Parker Palmer includes a poem by Anne Hillman, one of my spiritual “mentors.” Her verse seems to affirm my sense that perhaps “emptiness” is a good quality to bring to any threshold of change and transformation; that uncertainty doesn’t mean “lost” but rather alive and open to what’s next.

We look with uncertainty

by Anne Hillman

We look with uncertainty

beyond the old choices for

clear-cut answers

to a softer, more permeable aliveness

which is every moment

at the brink of death’

for something new is being born in us

if we but let it.

We stand at a new doorway,

awaiting that which comes. . .

daring to be human creatures,

vulnerable to the beauty of existence.

Learning to love.

As I wrote the other day, I often find my way forward by pausing where I am to ask a question. For me, it’s almost always my inner struggle to answer a question that inspires me — to write, to take a step, to make a change, to take a risk. And so I love the questions Anne Hillman’s poem inspired in Parker Palmer. I’ve already written them in my journal, to return to again and again as 2015 unfurls. I, too, feel pretty sure that a few open-ended, heart-centered questions will serve me better than any New Year’s resolution I might make. Do these questions resonate for you, too?

How can I let go of my need for fixed answers in favor of aliveness?

What is my next challenge in daring to be human?

How can I open myself to the beauty of nature and human nature?

Who or what do I need to learn to love next? And next? And next?

What is the new creation that wants to be born in and through me?

To all of you who take the time to linger here, to read my reflections and to offer your own thoughts in return, I am deeply grateful. Our ongoing conversation inspires me, and our ineffable, invisible heart-centered community makes my spirit sing. Thank you, dear readers, for always reminding me how much we have in common and how blessed we are to share this path through life!

And now, as we embark together into this brand new year, I offer you these words of blessing from John O’Donohue.

May you awaken to the mystery of being here.

May you have joy and peace in the temple of your senses.

May you respond to the call of your gift and find the courage to follow its path.

May you take time to celebrate the quiet miracles that seek no attention.

May you experience each day as a sacred gift woven around the heart of wonder.

The post in awe of the subtle appeared first on Katrina Kenison.