Katrina Kenison's Blog, page 3

March 26, 2019

dear older: I did not expect tears!

My friend, writing colleague, and gardening expert, Margaret Roach and I touch base almost daily. Often it’s just a texted line or two, to compare notes on the weather, what we had for lunch, or what’s worth reading in the New York Times. Sometimes, though, we go deeper, in leisurely over Skype and even in that most old-fashioned form of correspondence, actual letters. On occasion over the years, we’ve tidied up our communications and shared them with our readers, a series of letters we call “Dear Old, Dear Older” (Margaret has five years on me). The imminent publication of her all-new edition of her classic A Way to Garden: A Hands-On Primer for Every Season is quite an occasion, certainly warranting more than a texted “Congrats.” And so I put some of my first impressions of the book down for her — and for you — to read. Margaret’s response to my letter is here. (All of our past correspondence can be found here.)

My friend, writing colleague, and gardening expert, Margaret Roach and I touch base almost daily. Often it’s just a texted line or two, to compare notes on the weather, what we had for lunch, or what’s worth reading in the New York Times. Sometimes, though, we go deeper, in leisurely over Skype and even in that most old-fashioned form of correspondence, actual letters. On occasion over the years, we’ve tidied up our communications and shared them with our readers, a series of letters we call “Dear Old, Dear Older” (Margaret has five years on me). The imminent publication of her all-new edition of her classic A Way to Garden: A Hands-On Primer for Every Season is quite an occasion, certainly warranting more than a texted “Congrats.” And so I put some of my first impressions of the book down for her — and for you — to read. Margaret’s response to my letter is here. (All of our past correspondence can be found here.)

Dear Older,

I was just thinking: we’ve been friends nearly a decade. Looking back at the countless hours we’ve spent together – whether it’s sipping green tea at your work table as we scribble notes and brainstorm writing ideas, or wandering through your garden in all seasons, or sharing screenshots over Skype while you manifest some small WordPress miracle on my website – I’m struck, as always, by how creative, keen-eyed, and deeply knowledgeable you are.

You wear it lightly, all this hard-won, wide-ranging wisdom — never preaching, always gently guiding, revealing, encouraging. And yet, I’d venture to say this collaborative, can-do spirit is what truly defines you. What you know, you share, be it a planting tip, a recipe for compost or tomato sauce, a seasonal to-do list, or advice about getting rid of Japanese beetles. (By hand, damn it, one at a time.) No surprise then that you’re the one I (along with your legions of fans) turn to when I need some trustworthy advice, a workaround, a reason why, or just a pair of fresh eyes on an old problem. Knowing you as I do, my meticulous, brilliant, generous friend, I was fully prepared to be impressed by the all-new edition of your gardening classic, A Way to Garden.

But honestly, Margaret, I didn’t expect to cry.

For a book lover, there’s nothing quite like holding a fresh-off-the-press copy of a brand new title in one’s hands. And I’ve eagerly ripped into a lot of padded envelopes over the years, holding my breath till the contents are revealed — from the various works I ushered into life as an editor in the early ‘80s, through sixteen curated volumes of The Best American Short stories, and eventually on to the nervously awaited first copies of my own books.

For a book lover, there’s nothing quite like holding a fresh-off-the-press copy of a brand new title in one’s hands. And I’ve eagerly ripped into a lot of padded envelopes over the years, holding my breath till the contents are revealed — from the various works I ushered into life as an editor in the early ‘80s, through sixteen curated volumes of The Best American Short stories, and eventually on to the nervously awaited first copies of my own books.

Always, still, there’s a rush of emotion when a book is born, whether it’s a volume I’ve had a hand in publishing, the latest work of an admired writer, or a dear friend’s much-anticipated, finished-at-last project. Still, I’ve never once shed a tear over an advance copy of anything. Not until yesterday, anyway, when I sat down and began to slowly turn the pages of your beautiful new book.

Oh my goodness.

Part of this unexpected gush was surely because the physical book itself makes such a powerful first impression, stunning to behold with its lavish photos and gorgeously designed pages (kudos to your publisher on sparing no expense!), and then so intimate, encouraging, and convivial once one ventures within.

Part of this unexpected gush was surely because the physical book itself makes such a powerful first impression, stunning to behold with its lavish photos and gorgeously designed pages (kudos to your publisher on sparing no expense!), and then so intimate, encouraging, and convivial once one ventures within.

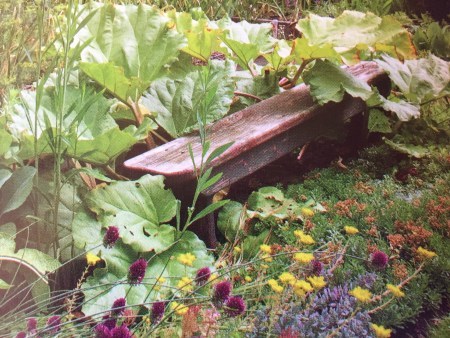

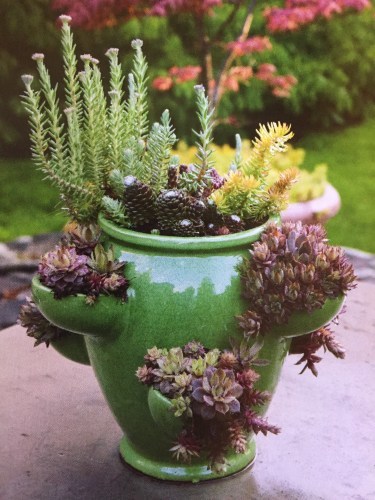

Opening to any page — be it a dramatic close-up of succulents stuffed into a strawberry jar, a handy list of germination times for favorite salad greens, or a gentle reminder to stop chasing peak moments and to the savor the little ones instead – is to hear your voice and to be right there at your side, in the garden, privy to its (and your) secrets. So maybe the sudden emotion I felt was partly relief, too. At last, it’s all right here, captured in print and stunning photographs forever — everything you have created, nurtured, learned, and are ready to pass along.

Opening to any page — be it a dramatic close-up of succulents stuffed into a strawberry jar, a handy list of germination times for favorite salad greens, or a gentle reminder to stop chasing peak moments and to the savor the little ones instead – is to hear your voice and to be right there at your side, in the garden, privy to its (and your) secrets. So maybe the sudden emotion I felt was partly relief, too. At last, it’s all right here, captured in print and stunning photographs forever — everything you have created, nurtured, learned, and are ready to pass along.

I vividly remember how magical it was to set foot for the first time into the verdant world that exists behind your deer fence, a formidable barrier that keeps foraging marauders at bay but which also encloses within its high walls an entire universe of wonders. It was October, and you led us around the back corner of the house and straight into the embrace of a venerable hundred-plus-year-old apple tree, as if facilitating an introduction between two cherished friends. And then you squatted down and set about filling a few sturdy cardboard boxes with drops. There were, it seemed, thousands of apples, both overhead and on the ground. You and the tree encouraged me to take as many as I could possibly make use of.

Somehow your new book, in all its visual largesse, and chock full as it is of practical advice and personal rumination, puts me in mind of that memorable day and its bounty. It’s as if every luminous photo, every tempting recipe and eloquent plant profile, every quiet reverie on change, impermanence, and the passage of time, is an offering. And, too, each page is just so much a reflection of you, you as a friend, as a writer, as a seeker, and as a gardener: open-hearted, opinionated, wise, and kind.

Somehow your new book, in all its visual largesse, and chock full as it is of practical advice and personal rumination, puts me in mind of that memorable day and its bounty. It’s as if every luminous photo, every tempting recipe and eloquent plant profile, every quiet reverie on change, impermanence, and the passage of time, is an offering. And, too, each page is just so much a reflection of you, you as a friend, as a writer, as a seeker, and as a gardener: open-hearted, opinionated, wise, and kind.

As E.B. White’s Wilbur noted upon first reading Charlotte’s latest spider-web masterpiece, “It is not often that someone comes along who is a true friend and a good writer.” To which I would add, “and a good gardener, too.” No wonder, then, that as I read through these pages and pore over the photographs, matching names at last to plants I’ve always wondered about, what I feel, all over again, is that sense of deeply rooted hospitality that first kindled our friendship. Except that now, here, it’s the essence of Margaret distilled into book form, as if you’re saying to all of us who have ever asked how deep in the soil to set the eyes of a bare peony root, or who have yearned to harvest a sweeter tomato from the vine: “Come, join me in the garden. I’ll show you.”

After I pulled myself together yesterday, I couldn’t resist the urge to find my old 1998 edition of A Way to Garden and set it down on the kitchen table alongside the updated one. Now a collector’s item, it was a much-heralded book in its day, but it is also so thoroughly of its day, which is to say, of your youth and of your garden’s earlier incarnation, too.

So, how wonderful it is that art and garden beds, unlike life, permit us an occasional do-over. And in this brand new edition, graced by twenty-one additional years of growth, reflection, trial and error, and hands-on learning, you’ve really seized your chance. A stroke of brilliance, I’d say – and probably of necessity, too, as you contemplated all that’s changed in your garden and in your thinking about plants, not to mention in the world at large, over the last two decades. (I’m so glad you talk about the climate!)

Still, this new book is so much more than a do-over. It’s twice the size, for one thing, with so much more to read and look at. I’m seeing it not as a second try at getting it right, but rather as the more evolved and expansive progeny of that very first guide, the one that started it all.

What I noticed right away, as I sat down to read more thoroughly, is not only your own ever-deepening sense of interconnectedness as you and your garden mature and grow older together, but also how your passions inspire me to look more deeply into the hows and whys of gardening myself. With each entry – from “A Moment for Lilacs” to “Putting Up a Year of Herbs” – I’m reminded of just how abundant and astonishing the natural world is when one slows down long enough to really look, and too, that I could become a more skilled and graceful steward of my own patch of ground. Your book may be first and foremost about gardening, but it’s also about gratitude, commitment, resilience, and paying attention.

What I noticed right away, as I sat down to read more thoroughly, is not only your own ever-deepening sense of interconnectedness as you and your garden mature and grow older together, but also how your passions inspire me to look more deeply into the hows and whys of gardening myself. With each entry – from “A Moment for Lilacs” to “Putting Up a Year of Herbs” – I’m reminded of just how abundant and astonishing the natural world is when one slows down long enough to really look, and too, that I could become a more skilled and graceful steward of my own patch of ground. Your book may be first and foremost about gardening, but it’s also about gratitude, commitment, resilience, and paying attention.

Perhaps one reason the new edition feels richer and more personal than the first, and even more like an extension of you, is because this time around you took almost all the photographs yourself, recording the moments as they happened – a sudden shaft of sunlight illuminating a cloud of spring crabapple blossoms, a garter snake peeking out from its niche in a stone wall, a pair of Hubbard squashes that look for all the world like an old married couple deep in conversation on a bench. Each is a poignant, indelible record of life’s fleetingness. And each reveals your affinity for this time and this place in a way no hired photographer, no matter how skilled, could ever hope to achieve. I love seeing your world through your eyes, attuned always to wonder, beauty, and evanescence. And I love meeting the friends who share your home, too, all those blessed frogs and birds and butterflies. Page by page, season by season, there you are, ready to capture and to share with us not only the stuff we need to know to succeed in our own gardens, but also the changes, both infintesimal and dramatic, that unfold on just over two lovingly tended New England acres in the course of a year.

Finally, I want to say this. Grateful as I am for the hands-on aspects of the book, I suspect I’ll return just as often to the essays you’ve written at the beginning of each chapter. These reflections, each a kind of mini-memoir, address the very themes we all wrestle with every day of our lives – how to be better humans, how to live more thoughtfully on the earth, how to create more sustainable relationships with our loved ones be they human, plant or animal, how to let go of what’s over, how to work with what is, and how to summon new faith as we step forward into whatever’s next.

“There is more to this gardening stuff than planting, I guess,” you conclude in your reflection about mending at last the decades-long distance between you and your sister. “No wonder, then, that the language of gardening and the language of life have so many words in common: words like tend and cultivate, words like grow.” Yes. Here, too, you are our guide.

You suggested (kidding, I hope!) that the reason I got all weepy when I first saw your book is because I’m old and unhinged. But that’s not it. In fact, the opposite is true. Your magnificent evocation of a life well lived, replete with passion, joy, and intense curiosity, makes me feel the very opposite of old. It reminds me how much is still possible, how much there is yet to learn, how much fun there is to be had out there in the dirt. And that if life is long and we are lucky, we might even get a chance now and then at a do-over. What a joy it is to help you celebrate the arrival, at long last, of what is surely your masterwork, the all new A Way to Garden!

Love, Old

By becoming a gardener, I accidentally—blessedly—landed myself in a fusion of science lab and Buddhist retreat, a place of nonstop learning and of contemplation, where there is life buzzing to the maximum and also the deepest stillness. It is from this combined chemistry that my horticultural how-to and ‘woo-woo’ motto derives.

On the second half of that equation, I think of my garden and myself as the two main components of the same organism. That perspective makes me think about the gardening year as roughly parallel to the six seasons of my own life, from conception through birth and on to youth, adulthood, senescence, and finally death and afterlife. Moving from phase to phase takes months or years (if all goes well) in the case of a human; in the garden, it’s all packed into a single year, and then starts over, and over, even long after the gardener is gone.

—Margaret Roach

pre-order a book. . .

And get a ticket for a free webinar with Margaret on April 2 or 4, or an in-person lecture on May 11 when her garden in Copake Falls will also be open to visitors. All about this special offer here.

Can’t make it on May 11? Margaret is lecturing around New England and opening her garden on several other summer weekends this year. Check out her complete schedule of events here.

or, if you just want your own copy asap . . .

Simply place an order now with your local bookstore, or pre-order here for delivery on publication day, April 30. A Way to Garden will be my go-to gift for Mother’s Day this year, so I’ll be purchasing multiple copies. You might want to do that, too! (Note: this is an Amazon affiliate link.)

The post dear older: I did not expect tears! appeared first on Katrina Kenison.

March 10, 2019

an everyday thing

“What is happiness except the simple harmony between a person and the life they live?” ~ Albert Camus

I have a friend who rose before dawn for six hundred days in a row. On every one of those mornings he took a cold shower, practiced a Kundalini yoga kriya, and exhaled a hundred vigorous Sat Nams into the dark. Along the way, he reported, he fell back in love with his life. He lost weight, found contentment, parented three kids and took a second job. He began teaching yoga himself and wearing white.

I have a friend who rose before dawn for six hundred days in a row. On every one of those mornings he took a cold shower, practiced a Kundalini yoga kriya, and exhaled a hundred vigorous Sat Nams into the dark. Along the way, he reported, he fell back in love with his life. He lost weight, found contentment, parented three kids and took a second job. He began teaching yoga himself and wearing white.

His dedication to the spiritual path was inspiring. The only things I’ve ever managed to do every day are brush my teeth and make my bed. My husband flosses seven nights a week. I try, but sometimes, for no good reason, I just skip it.

A decade ago, because I adored the teacher and because I was impressed by my friend’s dramatic transformation, I enrolled in a local Kundalini yoga teacher training and made my own commitment to cold showers and pre-dawn yoga practice. Getting out of a warm bed in the chilly darkness, leaving my sleeping husband and dog, gasping as the icy water hit my body at 4:30 in the morning, wrapping a white cotton scarf around my head before doing fifty squats and chanting mantras, I felt empowered but also tired and a little silly. Give it time, I told myself. You’ll get used to it. I didn’t.

Although the training was just one long weekend a month for ten months, the three-minute cold showers and pre-dawn yoga were meant to become daily lifelong rituals. I gave it a good try. Yet while my classmates reported emotional breakthroughs, newfound calm, and moments of epiphany, I felt increasingly resentful and exhausted and ridiculous. Also, I felt like a failure, by turns fraudulent and peevish, annoyed that this thing I had committed to doing seemed more like a ball and chain in my life than a liberation of my spirit.

Why, I wondered, did a routine that forms the basis of an entire school of yoga, one intended to calm your mind and energize your body, make me so miserable? I loved so much about that introduction to Kundalini yoga – the ethereal music, the chants, the energizing Breath of Fire, the sequences that were said to clear old hurts and scars and heal the endocrine system, and the spicy black tea we students sipped together after practice. But I also realized I was never going to become a Kundalini yogi. My entire system rebelled. I wanted to wake up with my husband, not an hour and a half before him. I wanted a hot shower. I felt uncomfortable with my head swaddled in a turban. I wanted to move my body in ways that felt supportive and good, not according to a sequence of poses written down years ago by someone who didn’t know me.

Most of all, I didn’t want to do anything every single day. Humbled, struggling to accept myself as a person lacking the self-discipline required for spiritual enlightenment or rigor, I left the training two months before it ended, rolled up my white headscarf and tucked it away in a drawer, and returned to my old weekly yoga class.

I had my first Dexa scan three years ago, a few weeks before my first hip replacement. The results, I was told in an email from my doctor’s office, could be found by logging into a patient portal: osteopenia. At the time, the news that my bone density was lower than normal seemed like the least of my worries. A dear friend had just died. I was preparing for two major surgeries. My doctor didn’t seem to think the condition warranted so much as a conversation, let alone an office visit. I made a mental note to think about buying some hand weights once my two new hips were in place and went back to reading about post-op PT. I barely gave osteopenia another thought

I had my first Dexa scan three years ago, a few weeks before my first hip replacement. The results, I was told in an email from my doctor’s office, could be found by logging into a patient portal: osteopenia. At the time, the news that my bone density was lower than normal seemed like the least of my worries. A dear friend had just died. I was preparing for two major surgeries. My doctor didn’t seem to think the condition warranted so much as a conversation, let alone an office visit. I made a mental note to think about buying some hand weights once my two new hips were in place and went back to reading about post-op PT. I barely gave osteopenia another thought

In November, realizing I’d met my insurance deductible for the year, I asked my doctor if it might be a good idea to recheck my bones. She’d never mentioned it again, and it wouldn’t have occurred to me to request a follow up had the test not been covered by insurance. This time, I got a phone call to come in to her office for the results.

“You have osteoporosis,” the doctor said mildly, without looking up. “A considerable amount of bone loss, which puts you at a high risk for fragility fractures, which are breaks that happen spontaneously, without any warning. I’ll write you a prescription. You can take this medication for four years. After that, we don’t recommend you continue because there are side effects with long-term use.”

I didn’t know much about osteoporosis at that point. But sitting there, absorbing this news as she stared at her computer, I did know one thing: my doctor was not seeing a person in front of her whose life expectancy had just grown dramatically shorter, she was seeing some numbers on a screen. She would be happy to write me a prescription, but she had no interest in the long-term health of my bones. Or in me. I was going to have to become my own student of bones.

Back at home, I scooped some yogurt (calcium!) into a bowl, switched on my laptop, and dove into my new assignment. If you’ve ever turned to Google to learn more about something happening in your body, you know: for every scrap of advice you turn up, there seems to be some other opinion that contradicts the first. But when it comes to bones there are quite a few facts that are universally agreed upon, from the mortality rates of hip fractures and the sobering statistic that one out of two women over fifty will experience an osteoporosis fracture in her life, to the importance of vitamin D, calcium-rich foods, and regular weight-bearing exercise.

To me the biggest surprise was that I had become so porous so fast, a fracture waiting to happen. I’d been pretty sure I was already taking good care of my bones. I exercise and practice yoga. I do eat well. I take a walk most days and turn my face to the sun. And yet, according to the numbers, my 60-year-old bones are equivalent in mass to those of an average 85-year-old woman. In three short years, I’d lost 27% of the bone density in my wrist and forearm. I was at risk for more bone loss, fragility fractures, and kyphosis. Suddenly, the possibility of a slip in the kitchen or a fall on the ice had become terrifying.

When I first sat down with my Dexa scan results in front of a website that helped me translate all the various measurements, I went from shock and disbelief to anger. Why had the doctor completely ignored the osteopenia three years earlier? Why had no physician ever talked with me in the past about my own high risk for osteoporosis and how to prevent it?

Would I have listened? If I’d known twenty years ago, at forty, what I now know at sixty, could I have avoided this condition altogether?

I suspect the answer to that last question is yes. There is so much I could have done, had I only known what to do. I also realize there’s no point in looking back with self-reproach to all the collard greens and almond butter I didn’t eat, the weights I didn’t lift, the Vitamin D I didn’t take.

But I feel certain I made the right call when I walked out of the doctor’s office that day without a prescription in my hand and went in search of another path.

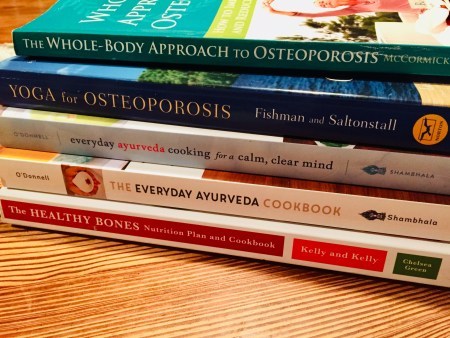

Over these last few months, I’ve had so much blood drawn for further tests that the lab at the hospital sent me a “thank you” card signed by all the members of the staff. (When you get an osteoporosis diagnosis, the first thing you want to do is have some other things checked, especially your thyroid and Vitamin D level.) I’ve read a whole stack of books by doctors and chiropractors and nutritionists. I’ve spent countless hours on line and compared notes with friends who are in the same boat I am, our zest for life and our sense of ourselves as healthy and strong butting up against the reality of our fragile skeletons.

Over these last few months, I’ve had so much blood drawn for further tests that the lab at the hospital sent me a “thank you” card signed by all the members of the staff. (When you get an osteoporosis diagnosis, the first thing you want to do is have some other things checked, especially your thyroid and Vitamin D level.) I’ve read a whole stack of books by doctors and chiropractors and nutritionists. I’ve spent countless hours on line and compared notes with friends who are in the same boat I am, our zest for life and our sense of ourselves as healthy and strong butting up against the reality of our fragile skeletons.

Bones, it turns out, are amazingly complex living structures that require knowledgeable care and feeding from many different sources. And it’s never too late to start making them stronger and healthier.

I’ve learned a lot about who’s most at risk for osteoporosis (white, thin, small-boned, fair-skinned, post-menopausal, women like me, for starters), why bones become brittle and how spontaneous fractures happen, why this condition, although invisible and painless until fractures occur, can’t be ignored, and how medication, though sometimes necessary, creates its own set of risks and problems. I’ve changed doctors and I’ve changed my diet. (I do not come home from the grocery store without brussels sprouts, bok choy, kale, almonds, and figs.) I’ve started a regime of supplements and vitamins. I’ve also changed the rhythm of my days, the way I spend my time, and even my attitude about being alive and growing old.

I’ve learned a lot about who’s most at risk for osteoporosis (white, thin, small-boned, fair-skinned, post-menopausal, women like me, for starters), why bones become brittle and how spontaneous fractures happen, why this condition, although invisible and painless until fractures occur, can’t be ignored, and how medication, though sometimes necessary, creates its own set of risks and problems. I’ve changed doctors and I’ve changed my diet. (I do not come home from the grocery store without brussels sprouts, bok choy, kale, almonds, and figs.) I’ve started a regime of supplements and vitamins. I’ve also changed the rhythm of my days, the way I spend my time, and even my attitude about being alive and growing old.

One of my first internet searches was “yoga and osteoporosis.” One click, and I was ordering Dr. Loren Fishman’s groundbreaking book Yoga for Osteoporosis, which offered exactly the encouragement I was desperate to hear: namely, it is possible to treat osteoporosis, in part, with the thing I like to do most. According to Dr. Fishman’s research, a regular practice of a series of twelve classical poses has been proven to strengthen bones and help prevent fractures. (He’s done a clinical study. It works. YAY!)

What I didn’t quite grasp, until my friend Maude and I took a fortuitously timed weekend workshop with Dr. Fishman at Kripalu Center for Yoga and Health a few weeks later, was that just going through the motions wouldn’t build our bones. Therapeutic yoga poses for osteoporosis have to be done every day, seven days a week, for maximum benefit. Poses have to be held, ideally, for a full minute. Held with full-on effort, precise alignment, and maximum resistance. Held with every muscle engaged, every breath complete, every ounce of intention and energy summoned and brought to bear while you work harder at your yoga practice than you have ever worked before. (Gentle yoga? Forget it.)

For two days, we repeated the same twelve familiar yoga poses with every possible modification. We held them as if our lives depended on it, which, in a way, they do. We left on Sunday afternoon exhausted and exhilarated and hopeful, and feeling the very opposite of fragile.

“By our sixties,” Mary Pipher writes in her illuminating, insightful new book Women Rowing North, “we may think the way we did in our forties, but our bodies don’t act that age. Intimations of mortality can make us sad and fearful, but they can also wake us up. Until we understand how short life is, many of us make the mistake of thinking our routines will go on forever.”

Since turning fifty, I’ve lost three close friends who didn’t make it to sixty. Each of these dear women, in her own way, approached the too-soon end of life by finding deeper satisfaction in the small pleasures and unexpected moments of grace that are so easily missed or taken for granted in our mindless rush to get to the next thing. Each of them transformed their initial “Why me?” reaction to a terminal diagnosis into a philosophical “why not me?” acceptance of the truth: that life is random and death inevitable, that tragedy is universal, that good health is not a given, and that each moment that we’re still here on the planet with our loved ones is a gift. When death draws near, we see at last what really matters. We have an opportunity to approach what time is left with more awareness, intention, and gratitude. Suddenly we can choose to live as if the moments, the days, the years really count. I sensed that myself as I blew out the candles on my birthday cake last fall: there’s no more time to waste.

I still feel like a beginner at being old. But I learned so much about how precious life is, and how ephemeral, from my friends who are no longer here. “Live your life,” my friend Diane urged me during many of our final conversations. She wanted me to write my books and to spend time with my family, to travel and to keep climbing mountains. She wanted me to carry on after she was gone in a way that wouldn’t ever give rise to regret for moments missed or love unspoken.

“You have osteoporosis,” is not good news to receive, but it’s a far cry indeed from a terminal diagnosis. I am just one of the eight million other women in this country with low bone density. For me, however, this new reality has been a wake-up call.

This diagnosis has brought home to me, in a way that even three years of arthritis pain and two hip replacements did not, the fact that life is finite and so am I. It has revealed that my body and I (“I” being that voice inside my head) are in a partnership, and that we must work together for the greater good of us both for as long as we are able. Osteoporosis has given me no choice but to take charge of my own health, to learn all there is to know about how to take better care of myself, and to make well-informed choices about what medications and supplements I take, what I eat, and what I do.

I would like to live for a long time – to live without cracking a rib when I sneeze, without losing an inch of my height, without rounding forward with a succession of hairline spinal fractures, without fear of getting hurt.

I would like to live for a long time – to live without cracking a rib when I sneeze, without losing an inch of my height, without rounding forward with a succession of hairline spinal fractures, without fear of getting hurt.

Of course, I also want to live without giving up the things I love to do. And this is where surrender comes in. Adjustments must be made. And so I’m learning that, with the right attitude, letting go is possible. I may not run or shovel snow or do forward folds and headstands anymore, but perhaps the very fact that I must give up a few things allows a deeper sense of gratitude for all that’s left, which, at this point is plenty. I do take extra care walking across the driveway after it’s snowed, but I can also put on my IceSpikes and hike up the mountain with ease. I can return a backhand to my husband on a (clay) tennis court. The day will come when these physical activities, too, will be a memory. My hope is that by then I’ll have grown more skilled at this task of accepting what can’t be changed.

As I watch my parents, both in their eighties, greet each day with good cheer and appreciation, I realize how much they still have to teach me — lessons of fortitude, resilience, and grace. Their own health issues are never far from any of our minds, and yet they do what they can with joy and good humor. This week, I’m with them in Florida, savoring the pleasure of being nothing but a daughter. Each morning, we gather in the living room and I guide my mom and dad through a yoga practice; for an hour or so they are my willing students, breathing their bodies into unfamiliar shapes and places, stretching muscles they had forgotten they even possessed. The learning, if our hearts and minds are open, can flow both ways.

“We shouldn’t be taking all this time out of your day,” my dad protested yesterday. On the contrary. My father is a man who feels naked without his shoes and socks on. To watch him lift and spread his bare toes, inhaling and exhaling, trying something brand new at age eighty-three, is both a delight and a memory to be stored. There is nothing I’d rather be doing.

Maybe this is how enlightenment works. You get the wake-up call, the clunk on the head, the message that is too loud and too insistent to ignore. And then you have a choice. You can turn away and go back to sleep, or you can dive in deep and allow the current of your life to carry you to places you never expected to go. As the time in front of us grows shorter, life’s beauty comes into sharper focus. There is something energizing about seeing the truth of one’s own mortality more clearly.

These days, I’m more aware than ever before that the moments I spend with the people I love are to be treasured not squandered. I’m more grateful than ever before that I am fit enough to climb that mountain, to take a nine-mile hike, to sweat it out for thirty minutes on the elliptical machine at the gym. In deference to my bones’ need for exercise, I actually find myself sitting less and moving more. (That does also mean writing less, alas, at least for now.)

And there is this. Ten years after my failed attempt at pre-dawn cold showers and Kundalini kryas, I’m doing something I never thought I could: thirty minutes of intense, challenging yoga a day. Every day. I stand in tree pose, unwavering, for a minute, breathing steadily. I am stronger than I’ve been in years. I’m not quite ready to say that my low T score was a gift, but it may turn out to be.

some resources

If you wish to strengthen your bones with yoga, Dr. Loren Fishman’s Yoga for Osteoporosis is your bible. There’s also a YouTube video to get you started. Work hard. Wrap your muscles around your bones. Hold the poses.

The best book I’ve found about the science of osteoporosis, what steps to take if you’re diagnosed, and the general care and feeding of your bones is Dr. Keith McCormick’s The Whole-Body Approach to Osteoporosis. Grab your highlighter.

Dr. Lani Simpson’s No-Nonsense Bone Health Guide is an invaluable resource packed with advice and encouragement. Also, she offers a comprehensive discussion of calcium supplementation and how to do it right.

In a holistic approach to healing, your kitchen is your pharmacy. Start feeding your bones (and learn what foods to avoid) with Annemarie Colbin’s The Whole-Food Guide to Strong Bones.

I swore I would buy no more cookbooks, but I did succumb to The Healthy Bones Nutrition Plan and Cookbook by daughter and mother team Dr. Laura Kelly and Helen Bryman Kelly. Lots to chew on here, with 100 practical, inspiring, tasty recipes.

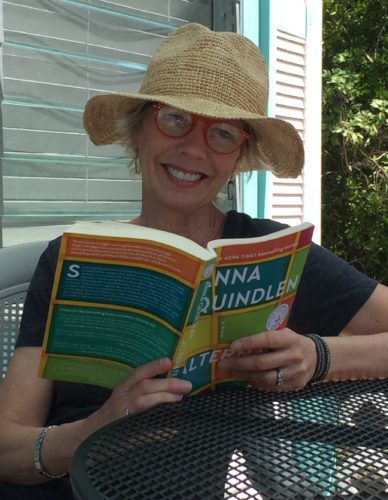

Finally, I can’t recommend Mary Pipher’s Women Rowing North: Navigating Life’s Currents as We Age highly enough. Although Mary claims to have written this book specifically for women crossing from middle age into old age (if we’re being literal, that means anyone over 50, right?), her wisdom and insight into change, loss, and growth are welcome no matter how old you are. She’s the kind of writer who feels like a friend. I found myself on every page.

The post an everyday thing appeared first on Katrina Kenison.

January 19, 2019

reasons to hope

“Keep some room in your heart for the unimaginable.” ~ Mary Oliver

“Keep some room in your heart for the unimaginable.” ~ Mary Oliver

Shortly before Christmas, on the raw, drizzly night when my son Henry and I bought the last fraser fir left at our local Agway, I also purchased a tangled bundle of bare branches adorned with shriveled red berries. Their austere beauty suited my mood, more so than the tiny bottlebrush trees and angel figurines I usually unpack right after Thanksgiving.

The last few months have been challenging. One of the reasons I’ve been quiet here is that struggles are hard to write about, especially during the holidays, when the world is bent on uplift and good cheer. Having failed to summon much advance holiday spirit myself, I put off decorating for so long that the local farm where we’d planned to cut down a tree had already sold out their crop for the year by the time we got there. At the eleventh hour, though, we lucked out. The tree that happened to be the very last tree left at Agway also happened to be perfect, not too tall and beautifully proportioned. I wandered around the yard the next day, clippers in hand, and cut boughs of pine and hemlock and rhododendron to mix in with the berries and put them in pitchers around the house. At the grocery store, white roses were on sale for five dollars; I bought some of those, too. Most of the rest of our decorations, collected over decades, remained in the basement. I don’t think anyone really missed them.

For a week in December, everyone was home. As the house filled with family and as Christmas Day arrived, so did joy. Meals were made and cleaned up after, walks were taken, fires were lit, loads of laundry and dishes were done. No one was tempted to talk about politics (we all needed a break). There were no peak moments, just a string of small, good ones. And no one took anything for granted, not the presence of grown children arriving from Cincinnati, Asheville, and Atlanta, nor the presence of my parents who, in their eighties, continue to meet the challenges of aging with good humor and grace. One of my favorite Christmas gifts came from Henry: an hour of piano music, which I cashed in on the night before New Year’s Eve. My mom came over that evening, we had a fire, and Welsh rarebit for dinner, and we all sat in the living room listening to a lovely, eclectic concert – from Rachmaninoff to Keith Jarrett — offered with love and played from the heart. Melted cheese and live music are an excellent combination. “I don’t want this to ever end,” my mom said in the moment of stillness after the first song. I felt the same.

Recently I read a quote on a friend’s blog, words from soul-centered business coach Hiro Boga that so aptly summed up my experience lately that I’ve been turning the words over in my head like a mantra ever since:

“Sorrow in one hand, joy in the other. Being human is a prayer.”

Somehow this simple reminder that life is never either /or, but always both, has brought me some needed reassurance throughout these first weeks of 2019. If I can let go of my desire to change or fix things, my own prayer becomes not a plea for life to be different but rather a bow to life as it is – at once dark and light, beautiful and hard, precious and messy, full of goodness and, too, ineluctably tinged with sadness, change, and loss.

It didn’t take long to pack Christmas away last month. By the time Henry and I got to the last tune on the “This Is Us” Spotify playlist, we had the tree stripped and he’d dragged it out to the burn pile in the field. The boxes of ornaments were back in the cellar and the floor was vacuumed. Empty and clean, the rooms seemed to exhale into spaciousness. Much as I love having a house full of people, I was also relieved it was all over.

That night, as I went to grab the greens from the pitcher in the dining room, I stopped in surprise. There, amid the desiccated berries, were tender green leaves sprouting forth. Expecting to toss out something dry and dead, what I found instead was the insistent wonder of new beginnings. The white roses, slumped amid the evergreens, struck me as equally beautiful. Gone by, yes, but aged now to ivory, soft and subtle as vintage silk. A couple of random petals, fallen from their blooms, were nestled among the pine needles as if placed by a decorator’s hand. Without my even noticing, the hasty arrangement I’d cobbled together before Christmas had transformed itself in the new year into an altogether different composition – a subtle revelry of releasing and renewing.

That night, as I went to grab the greens from the pitcher in the dining room, I stopped in surprise. There, amid the desiccated berries, were tender green leaves sprouting forth. Expecting to toss out something dry and dead, what I found instead was the insistent wonder of new beginnings. The white roses, slumped amid the evergreens, struck me as equally beautiful. Gone by, yes, but aged now to ivory, soft and subtle as vintage silk. A couple of random petals, fallen from their blooms, were nestled among the pine needles as if placed by a decorator’s hand. Without my even noticing, the hasty arrangement I’d cobbled together before Christmas had transformed itself in the new year into an altogether different composition – a subtle revelry of releasing and renewing.

Those small, unasked for leaves are not much in the grand scheme of things. Stick a bare branch in water, and it will have a go at life. And yet the sight of them now, still thriving during these final days of January, lifts my spirits immeasurably. This is what hope looks like.

Those small, unasked for leaves are not much in the grand scheme of things. Stick a bare branch in water, and it will have a go at life. And yet the sight of them now, still thriving during these final days of January, lifts my spirits immeasurably. This is what hope looks like.

And hope is what I’m choosing to carry forth into 2019.

I’ve always resisted the notion of adopting a word for the year and I didn’t expect to give in this year. But it seems my word has chosen me, and now that I have it, I’m not letting go.

To be an informed, engaged citizen of the world at this time is to live with a level of sadness, helplessness, and anxiety unlike anything I’ve known in my own lifetime. There are no quick fixes or easy answers, not for the small cares and concerns that darken my own thoughts, nor for the crises we face as a country, nor for the suffering in the world or the relentless human assaults upon our planet.

Yet something in my heart seems to have shifted. If there’s joy in one hand and sorrow in the other, then hope is the prayer that bridges the distance. Hope doesn’t mean the facts have changed. But the difference between hope and despair may turn on the story one creates with those facts. Hope is a kind of reframing. It has nothing to do with wishing and everything to do with seeing the truth through fresh eyes. Hope is a tilt of the head, a different perspective, a glass half full, a pair of spectacles with rose-colored lenses. Hope depends on a kind of stubborn willingness to recognize the possibilities and challenges buried within the present moment, no matter how dire it may seem, and to welcome those tiny scraps of potential goodness with faith and an open heart.

And so, I’m inviting hope to guide me forward. And I’m tuning my eye to see reasons for hope, no matter how small or random or unlikely they might be.

Look well to the growing edge! All around us worlds are dying and new worlds are being born. All around us life is dying and life is being born. The fruit ripens on the tree; the roots are silently at work in the darkness of the earth against a time when there shall be new leaves, fresh blossoms, green fruit. Such is the growing edge! … This is the basis of hope in moments of despair, the incentive to carry on when times are out of joint and people have lost their reason, the source of confidence when worlds crash and dreams whiten into ash. . . . Look well to the growing edge!

— Howard Thurman

This amaryllis, sent by a dear friend three years ago as I prepared for hip surgery, is blooming once again, magnificently, after spending the summer dormant and ignored in a dark outside corner and a few autumn months stashed in a chilly closet. Water and sunlight was all it took for green shoots and spectacular blossoms to return. The mystery of life is reason to hope.

This amaryllis, sent by a dear friend three years ago as I prepared for hip surgery, is blooming once again, magnificently, after spending the summer dormant and ignored in a dark outside corner and a few autumn months stashed in a chilly closet. Water and sunlight was all it took for green shoots and spectacular blossoms to return. The mystery of life is reason to hope.

Such is the growing edge.

A brilliant book and an inspiring weekend workshop on yoga for osteoporosis have given me reason to hope that this dreaded diagnosis, so unexpected and scary, is also an opportunity for me to stretch and learn. I’m improving my diet, becoming a student of bones, transforming my yoga practice, and choosing a whole-body approach to healing. Here’s to fish oil and calcium supplements, prunes and dandelion greens. Here’s to a commitment to get strong and to share the fruits of this path with others. Reaching out my arms in warrior pose, it occurs to me that growing older can also mean growing smarter.

A brilliant book and an inspiring weekend workshop on yoga for osteoporosis have given me reason to hope that this dreaded diagnosis, so unexpected and scary, is also an opportunity for me to stretch and learn. I’m improving my diet, becoming a student of bones, transforming my yoga practice, and choosing a whole-body approach to healing. Here’s to fish oil and calcium supplements, prunes and dandelion greens. Here’s to a commitment to get strong and to share the fruits of this path with others. Reaching out my arms in warrior pose, it occurs to me that growing older can also mean growing smarter.

Such is the growing edge.

Eight months after a trauma to his ears left him with acute, often debilitating tinnitus, my son Henry struggles daily to hold on to hope. Only someone who has lost the possibility of silence can fully appreciate just how precious that silence is. For a musician, for someone who values the empty spaces between the notes as much as the notes themselves, this loss is devastating. Henry can attempt to quiet the despairing voice in his mind, but there is nothing to still the incessant ringing in his left ear.

To say that every step of this journey has been hard doesn’t begin to convey just how hard it is, day in and day out. At times it is unbearable. And yet, even though there is no cure, there is still reason to hope. My own hopes for his future with this condition won’t be realized in any dramatic fashion, but perhaps they will manifest invisibly, slowly, over time. We can hope for resilience and equanimity, for courage and determination, for peace of mind. Meanwhile, I see hope right now in my son’s redoubled commitment to conducting and to playing the piano, despite how much more difficult this work he loves has become. There is reason for hope in his new meditation practice, in his reading and writing, in his dedication to yoga and exercise, to self-care and self-acceptance. I see hope, too, in his willingness to ask for help and to share the truth of his feelings. And in his will to move forward, even when forward feels all uphill. Yesterday, he began taking private jazz piano lessons, after quite a few years of focusing on the musical theatre repertoire. “How was it?” I texted last night. “It was good!” he typed back. “He threw a lot of stuff at me that’ll help me get my jazz chops back up again. It’s all still there, but it’s been dormant for a while.” For a worried mother, the quiet excitement behind those words is reason to hope.

To say that every step of this journey has been hard doesn’t begin to convey just how hard it is, day in and day out. At times it is unbearable. And yet, even though there is no cure, there is still reason to hope. My own hopes for his future with this condition won’t be realized in any dramatic fashion, but perhaps they will manifest invisibly, slowly, over time. We can hope for resilience and equanimity, for courage and determination, for peace of mind. Meanwhile, I see hope right now in my son’s redoubled commitment to conducting and to playing the piano, despite how much more difficult this work he loves has become. There is reason for hope in his new meditation practice, in his reading and writing, in his dedication to yoga and exercise, to self-care and self-acceptance. I see hope, too, in his willingness to ask for help and to share the truth of his feelings. And in his will to move forward, even when forward feels all uphill. Yesterday, he began taking private jazz piano lessons, after quite a few years of focusing on the musical theatre repertoire. “How was it?” I texted last night. “It was good!” he typed back. “He threw a lot of stuff at me that’ll help me get my jazz chops back up again. It’s all still there, but it’s been dormant for a while.” For a worried mother, the quiet excitement behind those words is reason to hope.

Such is the growing edge.

The truth is, it’s taken me the whole, long, frozen month of January to really embrace my word. At first, I wasn’t sure I had it in me. To declare hope as a way of life during difficult times sounds a bit dramatic and foolishly romantic, I know. Yet to see only the worst in any given moment denies my own capacity to make things better. If the tapestry of human history is woven through with threads of cruelty, thoughtlessness, and tragedy, it is also a long, astonishing story of compassion and courage, acts of kindness, and works of goodness large and small. Not to mention the occasional miracle. To embrace hope isn’t to deny reality but rather to acknowledge it and, at the same time, to shift focus from what is wrong to what is possible. What we choose to emphasize, right here, right now, is what determines the shape of our experience, the tenor of our days, the direction of our lives. If hope is a muscle, surely I should be able to strengthen mine.

I was sitting in my kitchen Thursday morning, trying to put these thoughts into words, when a text from my husband arrived with the news that Mary Oliver had died. Suddenly the gray sky beyond my window seemed a little darker, my own world emptier, as if a dear friend had left the room. If ever there was a writer who knew how and where to look for hope, it was she. To escape her abusive father and neglectful mother, she turned as a young child to the solace of nature, and to the possibility of creating her own inner landscape of wonder and beauty as a bulwark against the bleak and dangerous reality of her home life. Hope for Mary Oliver was infused with gratitude, with wonder, with a deep appreciation for the outdoors, for dogs and birds and wild animals, for sunsets and sunrises and all kinds of weather, for romantic love and spiritual ecstasy, and perhaps most of all, for the beauty and the potential of the moment at hand. “My work,” she said, “is loving the world.”

That is my work, too. And yours. And ours. May hope become not just a word, then, but a calling; not just a choice but a practice. To love the world is to do our own small part to honor and protect it. Joy in one hand, sorrow in the other, and hope as the energy that allows us to move more gracefully and purposefully through life as it is, not as we wish it to be.

Look around. What gives you reason to hope, right now?

The post reasons to hope appeared first on Katrina Kenison.

November 6, 2018

this is 60

Sixty is not middle-aged. Not even close. Sixty is a reckoning with the truth of mortality, with change, with a new sense of myself as finite.

Sixty is not middle-aged. Not even close. Sixty is a reckoning with the truth of mortality, with change, with a new sense of myself as finite.

Sixty is an expanded awareness of time passing. It’s wondering where the years went and, too, marveling at the breadth and depth of the journey — past, present, future. Sixty is standing on a threshold, contemplating the beginning of the end. To reach this place, alive and relatively unscathed, feels like both serendipity and blessing. Sixty is a more respectful understanding of fate. It’s the small but real comfort of being the youngest of the old. Sixty is a chapter between mid-life and old age, a chapter that has no name.

Sixty is twenty times three. Twenty more than forty, which sounds like a lot. And twenty less than eighty, which sounds like too little. It’s a number. Still, I can’t quite believe it’s my number. Sixty on the inside doesn’t feel very different from fifty, but sixty as the age I am now takes some getting used to. Still, sixty is quite different today than it was a generation or two ago. My sixty is not my grandmother’s sixty.

Sixty is facing the fact that my youth really is over. (I thought I’d faced it a while ago, but I guess I hadn’t. Not quite.) It’s coming to fully appreciate that those of us who grow old are the lucky ones. And it’s realizing how little I actually know about getting old. It’s pausing to think of the friends who didn’t make it, who will never be sixty, who are missing these surpassingly lovely autumn days. Sixty is about doing my best to live for them, too. It’s remembering their birthdays and their death days and the togetherness we shared along the way. Sixty is about trying, somehow, to hold on to all the years and ages that came before. It’s about accepting that they’re already gone, sifted through my fingers like sand.

Sixty is a constantly shifting landscape of diminishments and benefits, losses and gains. The losses are dramatic and obvious (think death and beauty) while the gains are often invisible but no less dramatic for that. Sixty is an appreciation for the moment at hand, because I know it won’t last. It’s a greater ease with things as they are, because I know they will certainly change. It’s delight in simple pleasures and other people’s joys and successes. Sixty is less drama and more contentment.

Sixty is the sweetness of waking up in the dark, spooned close to my mate of thirty-one years. It’s stepping outside with the dog into chill morning air just as the sun slips into view. It’s swirling cream into a mug of strong coffee, taking a walk, receiving a hand-written card in the mail. It’s a plane trip to visit a son in grad school and an hour on the porch with my mom, the reassurance of connection, caring, and the long, complicated tapestry that is one family’s history – a tale in which we are but single threads woven through our tiny portion of the vast human whole.

Sixty is the sweetness of waking up in the dark, spooned close to my mate of thirty-one years. It’s stepping outside with the dog into chill morning air just as the sun slips into view. It’s swirling cream into a mug of strong coffee, taking a walk, receiving a hand-written card in the mail. It’s a plane trip to visit a son in grad school and an hour on the porch with my mom, the reassurance of connection, caring, and the long, complicated tapestry that is one family’s history – a tale in which we are but single threads woven through our tiny portion of the vast human whole.

It’s a morning of raking leaves and watching the clouds, skipping the ibuprofen afterwards and feeling the soreness in my tired but still strong body instead. It’s a few silent hours of writing, a sense of satisfaction in having work to do, ideas to wrestle with, and sentences to shape. It’s continuing to believe in the power of words to heal a wound, to close a distance, to make a difference.

Sixty is trying out a recipe from a new cookbook, curling up on the loveseat once the dishes are done, watching a movie, legs stretched out into my husband’s lap. It’s a few minutes of reading before bed. Sixty is a newfound regard for the quotidian. It is realizing that the gift of an ordinary day becomes only more precious with each passing year.

Sixty is two parents in their eighties, two sons who are suddenly closer to thirty than to twenty, and a husband about to turn seventy. It is stopping in my tracks every now and then to wonder, “How did that happen?”

Sixty is about creating fluid relationships with aging parents and with grown children. And sixty is about making room for new connections to flourish. It’s about opening our home and our hearts to a soul daughter who was in search of a family, only to realize that I was also a mother who still longed for a daughter. Sixty is not caring at all about the labels and caring a great deal about the love. It’s living proof that family isn’t always defined by blood, but by affinity and affection, choice and intention.

Sixty is offering an arm to my elderly mother and receiving a helping hand from my youthful daughter. It is marveling at the strength of all these bonds even as I begin to absorb the necessity of one day letting each of them go. It’s about stepping in to steady the older generation and stepping aside to allow members of the younger one to stumble and fall and get up on their feet again. It’s about waiting to see how my mother and father will navigate their final years and how my sons will become the men they are meant to be and whether my husband and I will grow old together, side by side. Sixty is a dance of intimacy and independence, closeness and distance, reaching out and holding back, longing and surrendering. Sixty requires more tact, faith, and compassion than I ever knew I had in me.

Sixty is an ongoing private conversation with the universe. It is a prayer that by some combination of kismet and karma my sons will be blessed with lives that are rich and full and not too painful. It’s a hope that my parents will live out their days in peace and comfort. It is stopping by and hanging out at their kitchen table as often as I can. It is missing them in advance. It is being grateful for every day I still get to be a daughter. Sixty is about feeling my heart lift, always, at the sound of a familiar but fully adult voice on the other end of the phone. It’s knowing from the intonation of just one “Hey, mom,” whether it’s been a good day or a tough one, as surely as I once knew from the tilt of a head or the hunch of a shoulder what kind of day a little boy just had in second grade. Sixty is being grateful every single day that I am still a mother.

Sixty is funerals and weddings. It’s losing loved ones and bearing witness to tender beginnings. It’s showing up to be a steady presence at bedsides and showing up to help launch the young people I’ve known since birth who are suddenly taking marriage vows and starting companies and having babies of their own. It is watching children who once spent every day together, inventing worlds in the backyard, turn into grown ups and scatter like leaves in the wind. It is writing an obituary for a friend who should still be here and a happily-ever-after wish for a young man who, in my mind’s eye, is still a nine-year-old snapping gum on a pitcher’s mound. It is pretty new dancing shoes with heels that aren’t too high and it’s the plain dark skirt hanging at the back of the closet, awaiting its next call to duty. Sixty is gathering to mourn and gathering to celebrate. Sixty is grief and gratitude, sorrow and joy, all tangled up together.

Sixty is flipping through cute outfits on the rack and knowing better than to try them on. It’s being able to say “I’m too old for that” without resentment. Sixty is being done with shopping around. It’s brand loyalty: Jockey underwear, Darn Tough socks, Hoka sneakers. Sixty means arch support, even for flip flops. But it’s also finding out that dressing “my age” means wearing whatever feels good. It’s the freedom to have my own style and to change it by the day. It’s shopping at thrift stores, just as I did in college. Sixty is a stretchy black dress and the confidence to wear it and it’s soft faded jeans broken in by a stranger and silver hoop earrings made just for me by an eighty-eight-year-old friend.

Sixty is never leaving the house without a list. It’s forgetting things even if they’re written down on the list. It’s forgetting to read the list, or to bring the list. It’s about forgetting things that don’t go on lists and remembering things I thought I’d forgotten long ago. It’s leaving a message on a neighbor’s answering machine along with the phone number from the house we haven’t lived in for fourteen years. It’s losing my cell phone and finding it in the refrigerator. It’s losing my reading glasses and finding them on my head. Or worse, it’s losing my glasses, finding them, putting them on, only to realize I’m already wearing a pair. It’s being able to laugh at all these things. It’s rummaging around in the pantry for dinner, or eating cereal, or skipping it. It’s take-out Thai without guilt. It’s going out to dinner just because. It’s the freedom to trash the list.

Sixty is never leaving the house without a list. It’s forgetting things even if they’re written down on the list. It’s forgetting to read the list, or to bring the list. It’s about forgetting things that don’t go on lists and remembering things I thought I’d forgotten long ago. It’s leaving a message on a neighbor’s answering machine along with the phone number from the house we haven’t lived in for fourteen years. It’s losing my cell phone and finding it in the refrigerator. It’s losing my reading glasses and finding them on my head. Or worse, it’s losing my glasses, finding them, putting them on, only to realize I’m already wearing a pair. It’s being able to laugh at all these things. It’s rummaging around in the pantry for dinner, or eating cereal, or skipping it. It’s take-out Thai without guilt. It’s going out to dinner just because. It’s the freedom to trash the list.

Sixty is a soft-bristled toothbrush, Sensodyne toothpaste, and a mouthguard at night. Sixty is my husband reminding me that once upon a time we slept naked together even in winter, even in a bedroom with big old windows and bone-chilling drafts, even when we could see our breath. Sixty is moisture-wicking pajamas, cozy sleeping socks, and a soft chenille bathrobe that ties at the waist. Sixty is choosing comfy over sexy. But sixty is also, once in a blue moon, the lace bra that lifts and separates, the silky nightgown that looks just fine, the glass of champagne, the jasmine oil.

Sex at sixty is both a waning and a waxing. It is less about need and more about connection, less about desire yet more about intimacy. It’s less often but more intense. Slower and less predictable. Not as athletic but more tender. As much about pleasure in the mind as it is about hunger in the body. (Age is full of surprises. Not all of them are bad.)

Sixty is more dry than juicy. It’s leave-in conditioner, moisturizer twice a day, hand cream in my purse, shea butter for cracking heels, and sunscreen even on cloudy days. (Better late than never.) Sixty is about lubricating. It’s receiving a birthday gift of four different face creams from a lifelong friend along with instructions to “layer.” It’s wrinkles and pouches and unwanted flaps of skin. Sixty is wrinkles. And it’s eternal hope, too. After all, four face creams!

Sixty is more dry than juicy. It’s leave-in conditioner, moisturizer twice a day, hand cream in my purse, shea butter for cracking heels, and sunscreen even on cloudy days. (Better late than never.) Sixty is about lubricating. It’s receiving a birthday gift of four different face creams from a lifelong friend along with instructions to “layer.” It’s wrinkles and pouches and unwanted flaps of skin. Sixty is wrinkles. And it’s eternal hope, too. After all, four face creams!

Sixty is no more hair growing in the places I used to shave and brand new hair cropping up in places it never was before. Sixty is keeping tweezers handy and letting the blade on the razor turn to rust. Sixty is a crepey neck and a permanently furrowed brow. It’s a new ability to spot a botoxed forehead from across the room. It’s realizing how many of us are smoothed out between the eyebrows. It’s looking crabby in every photograph, even when I’m happy. Which I am. Mostly.

Sixty has its moments of melancholy. So much is over. There’s no going back. Sixty is the realization that joy doesn’t just happen, I have to choose it again and again. It’s a choice that requires effort sometimes. Sixty is an opportunity to rethink some old ideas. It’s a farewell to a certain kind of ambition and it’s an uncomplicated pleasure in the job at hand – cutting back the garden, stuffing envelopes for a local nonprofit, driving a friend to the doctor, writing a good-enough paragraph. Sixty is time to let go of perfection. Time, also, to give up comparing, worrying, arguing over petty things, and taking slights personally. Sixty means there’s no more time to waste. (Not that there ever was.)

Sixty comes with permission to love my friends more deeply. It’s making the phone call, writing the note, coming up with the plan, making it happen. It’s texting a photo of the sunrise or the salad I made for dinner and getting a sunrise or a pie or a basket of swiss chard in return. It’s not hesitating to say whatever words I need to say: I’m sorry. Please forgive me. Thank you. I forgive you. I love you. It’s finding the perfect extravagant gift and it’s the joy of giving something wonderful to someone who doesn’t expect it.

Sixty is about accepting my limitations. It’s realizing I can’t be all things to all people. It’s speaking the truth and living with the consequences. Sixty is choosing integrity over popularity, which means watching some people walk away and being ok with that. And it’s befriending my own imperfect, less driven, less busy self. A self not so adept at retaining facts but somewhat better at taking the long view. A self who is done with multi-tasking but who turns out to be happier doing one thing at a time slowly and carefully and well. A self who is slower to hurt and anger and quicker to apologize. Less of a grind, but more at ease in her own skin. Less polished and more vulnerable. Less impressive but more honest. Kinder. Or so I hope.

Sixty is an impulse to simplify. It’s looking around and noticing how much of what I have, I’ve ceased to really see. It’s packing stuff away, giving stuff away, throwing stuff away and exhaling into the empty spaces left behind. It’s more trips to Goodwill than to the mall. It’s wondering why I ever thought it was a good idea to collect anything. It’s a box in the basement slowly filling with things that once seemed like reflections of me but are now just things. It’s realizing they were always just things. Sixty is less time spent taking care of things and more time attending to what is ineffable, invisible, intangible. It’s forgiving everyone for everything and traveling a bit more lightly through my own emotional landscape. Sixty is about clearing some space – in a kitchen drawer, in my mind, in my relationships, in my heart.

Sixty is an impulse to simplify. It’s looking around and noticing how much of what I have, I’ve ceased to really see. It’s packing stuff away, giving stuff away, throwing stuff away and exhaling into the empty spaces left behind. It’s more trips to Goodwill than to the mall. It’s wondering why I ever thought it was a good idea to collect anything. It’s a box in the basement slowly filling with things that once seemed like reflections of me but are now just things. It’s realizing they were always just things. Sixty is less time spent taking care of things and more time attending to what is ineffable, invisible, intangible. It’s forgiving everyone for everything and traveling a bit more lightly through my own emotional landscape. Sixty is about clearing some space – in a kitchen drawer, in my mind, in my relationships, in my heart.

Sixty is a bit devil-may-care. It’s doing things because I want to rather than because someone else thinks I should. It’s saying no to what doesn’t feel right and yes to the small voice inside that says, “This way.” Sixty is planning a hiking trip to England with a bunch of women and volunteering to teach yoga to women in recovery. It’s discovering that we are more alike than different.

Sixty is a deepening concern for our shared future. It’s a desire to give something back, to make the world a little better while I still can. Sixty is flexible. It’s understanding that information isn’t wisdom, and that wisdom arrives quietly and in its own time, nourished by listening and silence and reflection. Sixty is a greater willingness to compromise, to collaborate, to consider another point of view. Sixty is less about being right and more about being present.

Sixty is daily gratitude for modern medicine and replacement parts. It’s two artificial hips and two four-inch scars and long, pain-free walks. It’s taking nothing for granted: climbing a mountain, carrying groceries, running upstairs, pushing a wheelbarrow, warrior pose. Sixty is still a two-way street, up and down, breaking apart and coming back together again. Sixty is self-care and maintenance. Sixty is strong and able. Sixty is fully alive, awake, and vital. Sixty is also knowing, in the words of the late poet Jane Kenyon, “Someday it will be otherwise.”

Sixty inspires a certain kind of urgency. It is a desire for a life that is both less and more. It’s the end of carrying on as if time were an unlimited resource to be spent and spent and spent. There is no world but this one. No meaning but the meaning I’m willing to create. I have one life and one life only. Though brief, it will have to do. Sixty feels like a nudge in the direction I’ve always wanted to go, a summons to pay closer attention to the way I spend my days, to the things I say and do, to the qualities I still aspire to embody.

Sixty is an invitation to make a deeper kind of peace with impermanence. It’s about rising to the challenges of aging and also embracing the mysteries, wonders, and gifts of growing older. It’s a desire to ripen into wisdom, into goodness, into a woman who may one day be an elder but who is, for now, just another year older. Sixty is knowing today is an occasion, tomorrow isn’t guaranteed, and every plan is provisional. Sixty is the beginning of the if-not-now-when decade.

Burn the candle.

Use the china.

Open the wine.

Carpe Omnia.

Seize everything.

The post this is 60 appeared first on Katrina Kenison.

September 21, 2018

why I believe her

I suspect I’m not the only woman who finds herself thinking about truth and sex and high school this week. As supporters of Judge Brett Kavanaugh mount their crusade against Christine Blasey Ford, many of us are wondering what we would do in her shoes.

I suspect I’m not the only woman who finds herself thinking about truth and sex and high school this week. As supporters of Judge Brett Kavanaugh mount their crusade against Christine Blasey Ford, many of us are wondering what we would do in her shoes.

If it were me, could I endure the pressure and continue to stand my ground for the sake of the integrity of the Supreme Court? Would I have the courage to show up on a national stage and speak the truth, despite the massive attempts on the right to undermine me? Sitting alone in the safety of my own quiet home, my heart goes out to this deeply private woman who made the brave choice of stepping forward, only to be forced into hiding by death threats. I honestly have no idea whether I could put myself through the hostile process that will surely unfold next week if Dr. Ford decides to testify under oath even in the absence of the FBI investigation she has rightfully requested. But there’s one thing I do know: I absolutely believe she is telling the truth.

In the photo above, I am fifteen or sixteen, close to the age Dr. Ford was when she was assaulted in a locked room by a drunk older boy while his buddy first urged him on and then warned him to stop. This picture brings back all sorts of memories – of the kitchen in my house where it was taken, of the time it spent to blow dry my hair into that careful pageboy, of the shark-tooth choker I’m wearing around my neck. I remember the shirt, too – it was my “going out” blouse, an ivory smock I thought was soft and pretty and a bit bohemian. As soon as I came across the photo, I remembered another thing about that top: I always wore it with a leotard underneath. In those pre-camisole days, a leotard meant you had to get completely undressed to go to the bathroom. But a leotard under a loose blouse was also a necessary, albeit thin, line of defense against an unwanted male hand grabbing at your breasts.

As I approach sixty, I realize how much of the past I’ve forgotten over the years – the little things, the passing moments, the sweet ordinary memories that add up to a good, decent life.

But there are also incidents that remain indelible, even now. And many of those moments have to do with early sexual experiences, both good and bad. My own most intimate memories from high school and college are especially, sometimes painfully, vivid. The more disturbing ones are irrevocably lodged in my body, in my mind, and sometimes, still, in my dreams.

Coming of age, coming into our own as women, coming into our sexuality, navigating our way through our own first, fumbling sexual encounters — whether we initiate them, welcome them, or survive them; whether they are exhilarating or terrifying — this is big stuff.

You’d think it would go without saying.

And yet, today I feel the need today to say it: When it comes to sex, women don’t forget what we did or who we did it with, no matter how many years have passed. We most certainly remember, with precise and painful clarity, what was done to us. And we remember who did it.

This, apparently, is news to the men who now claim Christine Blasey Ford must be suffering from some kind of confusion or amnesia about exactly who assaulted her. How else to explain their latest line of defense of Brett Kavanaugh?

That seventeen-year-old kid who clamped a hand over fifteen year-old Christine’s Blasey’s mouth to keep her from screaming while he tried to rape her? That guy couldn’t have been our Supreme Court nominee! It must have been some other guy. Poor, confused Dr. Ford just doesn’t remember who.

Forty-two years after graduating from high school, I can still name the gropers. I remember exactly who they were. I remember what they looked like. I remember exactly what they did. I remember how ashamed and humiliated they made me feel. I remember keeping quiet, because to speak about these unspeakable things would somehow mean acknowledging the truth of them, and that would have been sickening and terrifying. And, while I did not find myself trapped in a room with a potential rapist at age fifteen, it requires no great leap of imagination on my part to envision the horror of such an assault or its after effects: a lifetime of nightmarish remembering, coping, healing.

This kind of pain doesn’t fade and get blurry around the edges over time. The face of one’s attacker doesn’t gradually morph into some other vaguely familiar face from the past. No. Just ask any survivor: the memory is the thing lasts. A woman who has been physically attacked by a man does not forget the experience, she relives it. Over time, if she’s lucky, she finds a way to move forward, albeit haunted by the ever-present, sharp-edged awareness of what was done to her. She lives while also knowing that the very person who inflicted that harm has rewritten the story so that he can live with himself: as if innocent, as if blameless, as if it never happened at all.

The men (and they are, for the most part, men) who are mounting a defense of Brett Kavanaugh on the basis of “mistaken identity” may look back on their own sexual exploits as a series of successful conquests or humiliating failures in which their consensual partners or unwilling victims were indistinguishable from one another and therefore forgettable.

It’s an appalling thought. But it seems that’s really how it was for these guys. They would have us believe that their youthful “escapades” meant little then and less now. To them, we were randomly appealing teenaged bodies to be lured in, pinned down, used and walked away from, with nary a backward glance.

Apparently that’s the way the Republicans on the judiciary committee still see things. How else could they so glibly justify Kavanaugh’s questionable past and, at the same time, work so vehemently to erode Dr. Ford’s credibility? Why else would they adamantly refuse to step on the brakes and call for an investigation that could either clear Judge Kavanaugh’s name or shed objective light on the facts as Dr. Ford remembers them? And how else could they expect anyone to buy this ridiculous line of defense?

And yet here we are, being told to shut up and swallow it as Brett Kavanaugh’s champions race him toward confirmation. It’s quite a disturbing glimpse into the inner workings of the mind of a certain kind of man. A man who experiences sex as being disconnected from feelings. A man who sees sex as his right. A man for whom sex is something to be done, denied, forgotten. A man much like the one in the White House.

further . . .

After a summer away from this space, I did not intend to resume writing with a post about politics. In fact, my intent was to share some reflections about reconnecting with my beloved first grade teacher. That story will wait. This one couldn’t. I felt moved to gather my own thoughts after listening to Atlantic writer Caitlin Flanagan recall being assaulted by a high school classmate, and the effect of that single traumatic incident. You can listen to her interview on the New York Times Daily here.

Dr. Ford’s credibility is supported by this NYT article by a psychiatrist who explains the neuroscience behind memories formed under the influence of intense emotion.