Katrina Kenison's Blog

October 4, 2025

you can’t have it all

Last summer, during the time when melanoma surgery had confined me to the chaise on our porch with my leg elevated above my head, I came across a poem that saved me. Or so it seemed, as I read it over and over again, suddenly seeing what felt like the unluckiest time of my life through a new lens.

Last summer, during the time when melanoma surgery had confined me to the chaise on our porch with my leg elevated above my head, I came across a poem that saved me. Or so it seemed, as I read it over and over again, suddenly seeing what felt like the unluckiest time of my life through a new lens.

Funny, how one simple phrase can lodge in the mind, take up residence in the heart, and offer a kind of solace and sustenance that even a whole book couldn’t provide.

“You Can’t Have It All” is the title of the poem, and these are the words I grabbed like a life ring, the simple truth that got me through.

As I read Barbara Ras’s lovely, whimsical litany of the small blessings she could celebrate in her ordinary, imperfect life, I knew I wanted to make a list of my own. There were so many things I couldn’t have in that hard moment – a shower, a walk, a trip to the store – but I began to notice the countless gifts that were still mine for the taking. All through August and September, as I drove back and forth to doctors’ appointments and daily radiation treatments, I composed new versions of the “You Can’t Have It All” poem in my head, realizing that every day I could write an entirely different one. We all could.

This week, with my various medical dramas behind me at last, I retreated to my family’s house in Maine for a couple of solitary days before my birthday. Sixty-seven is nothing special, but it feels like a milestone to me, as I round the corner toward seventy with more challenges ahead and a greater awareness of just how little any of us ever know about what our futures will hold.

In 2024, I spent one week of every month, from April through October, in Maine with my parents, happily chauffeuring them to and fro, shopping and cooking, delighted to spend time with them in this house full of memories, the place we all love best. This year, cancer treatments kept me at home and it’s become harder for my parents to travel. So much has changed, and change these days feels like another word for loss. To have even a few days to slip away by myself has felt kind of miraculous.

I can’t have it all, but I am here. And so, for my birthday, I’ve finally written my own version of Barbara Ras’s wondrous, grounding poem. Maybe you’ll be inspired to do the same.

You can’t have it all.

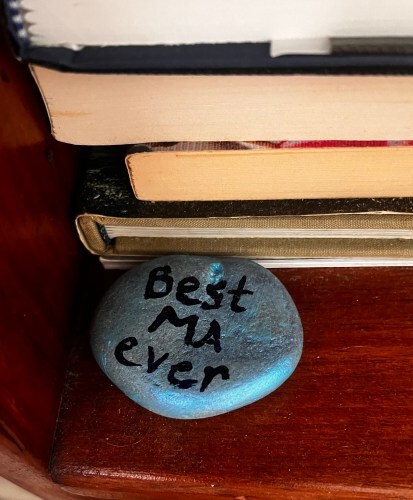

But you can have the hour before dawn in a house by the sea. You can have the luminous moon framed by your window, its milky cone of light flung across the glistening dark water. You can have the delicious ease of your own warm body stretched out under the covers like a star. You can have the blue painted rock that says “best Ma ever” on the table by your bed.

You can have your coffee, dark and strong, in the old blue pottery mug that feels like satin and fits your cupped hands just so. You can have a peach. Tender and weighty, and all the sweeter for being the last one of the season. You can have contentment.

You can have your coffee, dark and strong, in the old blue pottery mug that feels like satin and fits your cupped hands just so. You can have a peach. Tender and weighty, and all the sweeter for being the last one of the season. You can have contentment.

You can’t have a promise of tomorrow, but you can have every moment of today, and you can have it all to yourself. You can’t know if your cancer will return, but you can live without knowing.

You can have Dr. Malik, who showed you the hole in your heart, who closed it for you, and then later came to your bedside and pressed his hand to your wound to help slow the bleeding. You can have Dr. Ryan, who treats you like a friend, who carefully carved the tumor out of your breast and, with the tiniest of stitches, sewed you up again. You can have her nurses, who always, still, call you back. You can have kindly technicians who greeted you by name and covered your legs and bare arms with warm blankets and sent beams of radiation deep into your chest every day for twenty days, and who posed with you for a photo when it was all over. You can have Dr. Park, in her rhinestone-encrusted Apple watch and red high heels, who knows your oncotype number by heart, who listens with her whole body, who hugged you hard when tears welled in your eyes. You can have Dr. Zipoli, who said he was sorry before he cut the wide, deep circle out of your calf, who gently put his hand on your back and asked if you were ok, who saw you at 8:15 am for ten straight Tuesday mornings to patiently debride the wound and apply a fresh graft to that painful, slow-to-heal spot. You can have Medicare.

You can’t have a charmed life. But you can have friends at your side for your life as it is. You can have loved ones who show up for for all of it. Who counted down the days with you, who held you from afar and brightened your hardest days with texts and flowers, with cards and care packages, meals and phone calls. And who were there to cheer you across the finish line as if you’d run a marathon, which of course you didn’t, although, in truth, it kind of feels as if you did, and the people who love you know that, which means a lot.

You can’t have a charmed life. But you can have friends at your side for your life as it is. You can have loved ones who show up for for all of it. Who counted down the days with you, who held you from afar and brightened your hardest days with texts and flowers, with cards and care packages, meals and phone calls. And who were there to cheer you across the finish line as if you’d run a marathon, which of course you didn’t, although, in truth, it kind of feels as if you did, and the people who love you know that, which means a lot.

You can’t have it all. But you can have a break. You can have three months off from doctors and cancer drugs, and three months feels like enough, enough time to heal, to rest, to play, to gather strength for what comes next.

And now that it’s October, you can have autumn. You can have autumn in abundance. You can have apples with names like Gravenstein and Pippin and Northern Spy. You can have red maple leaves and acorns, blue skies and starlight. You can have sweater weather. You can have asters blooming by the roadside, milkweed bursting from swollen pods, the fragile petals of wild roses, tumbling hydrangeas in fading shades of dusky pink and heathered violet. You can have a single Monarch sailing through sun-warmed air. You can have crows, and their endless cacophonous conversations in the twisted pine tree that miraculously survives every storm. You can have frilled cosmos and a handful of late lavender to cut for a bouquet.

And now that it’s October, you can have autumn. You can have autumn in abundance. You can have apples with names like Gravenstein and Pippin and Northern Spy. You can have red maple leaves and acorns, blue skies and starlight. You can have sweater weather. You can have asters blooming by the roadside, milkweed bursting from swollen pods, the fragile petals of wild roses, tumbling hydrangeas in fading shades of dusky pink and heathered violet. You can have a single Monarch sailing through sun-warmed air. You can have crows, and their endless cacophonous conversations in the twisted pine tree that miraculously survives every storm. You can have frilled cosmos and a handful of late lavender to cut for a bouquet.

And you can have a table by the roadside laden with the last gleanings from someone’s island garden, tomatoes and dahlias in green plastic cups, a jumbled pyramid of miniature squash and motley eggplants, and a jar for the dollar bills you might wish to leave behind. You can have a bit of your faith in ordinary goodness restored.

And you can have a table by the roadside laden with the last gleanings from someone’s island garden, tomatoes and dahlias in green plastic cups, a jumbled pyramid of miniature squash and motley eggplants, and a jar for the dollar bills you might wish to leave behind. You can have a bit of your faith in ordinary goodness restored.

You can have a long walk to the beach, past boats dry-docked in yards and silent, empty houses closed up for the season. You can have this beautiful world, the one that’s been here all along, just waiting for you to return to it. You can try not to miss anything. You can have a chip of blue sea glass and a smooth gray stone to tuck in your pocket. You can take off your shoes, step into the icy waves lapping the shore, and relish the cold shock of it, your toes cramping as shivers run through your limbs. And even though you had a summer without swimming, you can have this, your feet in the water on the last day of your 66th year.

You can’t have it all, but you can have two days in Maine, eating avocado toast for dinner with your book propped up. You can steep in silence and your own company. And you can realize you are still you, which is to say ok, but also different. Here, alone, you can look back on what you’ve just been through and marvel a little at how, in the unlikely way of some hardships, these things have changed you, probably forever and probably for the better. You can love your life with a little more tenderness. You can understand, in a way you never did before, how fragile it is. And how precious.

You can’t have it all, but you can have two days in Maine, eating avocado toast for dinner with your book propped up. You can steep in silence and your own company. And you can realize you are still you, which is to say ok, but also different. Here, alone, you can look back on what you’ve just been through and marvel a little at how, in the unlikely way of some hardships, these things have changed you, probably forever and probably for the better. You can love your life with a little more tenderness. You can understand, in a way you never did before, how fragile it is. And how precious.

You can have a birthday without a party and still it will feel like a celebration. You can have your husband meet you at the farmer’s market on a fine fall morning and you can greet him with a kiss. You can buy donuts to share as you wander the rows, gathering salad greens, bread, and fish for the dinner you will make. You can create a day together, back at the house where you fell in love four decades ago, where you spent your first married night, and where your wedding dress still hangs in its plastic bag at the back of the closet nearly forty years after you took the vows that bound you to each other in sickness and in health. You can have Jackson Browne on the dusty black turntable, the first birthday gift he ever gave you, which still works. You can have this long marriage, this man, the life you’ve built, the sons you raised, the soul daughter you chose, your parents, who are still here to tell you the story of the day you were born.

You can’t have it all. But you can have grace in all its guises. You can see beauty in today’s small doings. You can be kind and you can receive kindness in return. You can have what Mary Oliver calls “the imponderables, for which we have no answers, yet endless interest, all the range of our lives.”

You can’t have it all. But you can have grace in all its guises. You can see beauty in today’s small doings. You can be kind and you can receive kindness in return. You can have what Mary Oliver calls “the imponderables, for which we have no answers, yet endless interest, all the range of our lives.”

You can’t have it all, but you can have a really good book

Every once in a long while, a novel comes along that I want everyone I know and love to read. Patrick Ryan’s epic, generous, gorgeously written, heart-expanding “Buckeye” is that novel. And because I adore it so, I’m buying one copy to give away here to one of you.

Enter to win by leaving a comment. Want to share something you do have, even though you can’t have it all? Do it below, and perhaps I’ll draw your name at random. I’ll pick a winner on November 3. And if you don’t want to chance it, please, just treat yourself to this book. I promise, you’ll be glad you did.

You can order “Buckeye” from Amazon (an affiliate link) here. Or order from Parnassus Books, which stocks signed copies, here. (In fact, “Buckeye” is dedicated to Ann Patchett and her husband Karl.) Barbara Ras’s book of poetry, “Bite Every Sorrow” is available here , and you can read the original poem here.

The post you can’t have it all appeared first on Katrina Kenison.

July 23, 2025

act of imagination

“In the high heat of summer, things slow down a bit, and there is time to remember a few things you may have forgotten.” ~ Brian Andreas

“In the high heat of summer, things slow down a bit, and there is time to remember a few things you may have forgotten.” ~ Brian Andreas

Hello, old friends from long ago. It certainly has been a while.

I wasn’t sure if, or when, I might return to this space. But I also couldn’t quite close the door and let it go, just in case the day should ever come when we’d reconnect and start anew. And now, here I am, with some time on my hands and a few mid-summer thoughts.

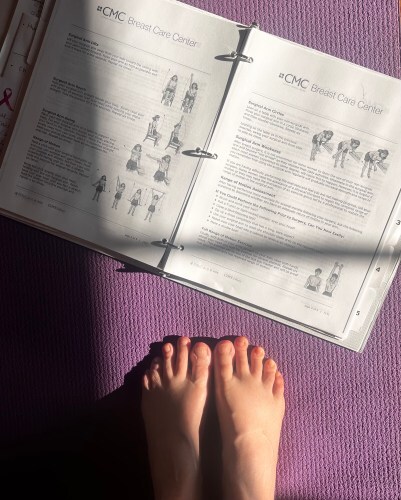

It’s tempting to take a detour here into a personal update, but that would be another post altogether. And so, for now, a few quick health headlines will suffice. A breast cancer diagnosis in April put me on a road no woman ever chooses to walk. (And yet, as I discovered right away, this road is crowded with old and new friends, women who show up, hands extended in welcome, offering hope, kindness, advice, and companionship.) While having an MRI to assess the extent of my cancer, I lost consciousness, spent four days in the hospital for tests, and was found to have a hole in my heart that required repair (a PFO closure) before I could proceed with the breast surgery. The heart surgery had to be followed by a month of recovery and blood thinner medications. And then the blood thinners had to be entirely out of my system before I could finally have the breast surgery.

Two days before my lumpectomy on July 2, my dermatologist removed a dark spot on my leg. A week later, I learned I had melanoma. (Somehow, at that point, this diagnosis didn’t surprise me at all.) Because of the location – down low on my calf — my surgeon was unable to suture the wide excision required for clear melanoma margins; I simply didn’t have any extra skin for him to stitch. Nor did he think a skin graft would be successful.

He had no choice, he explained, but to leave me with a deep surgical wound, and that large wound would require me to stay off my feet, keep my leg elevated, and change the dressing every day for many weeks. And then the doctor put a kindly hand on my shoulder. “I’m so sorry,” he said gently. “This is going to be your summer. And it’s not going to be easy.”

And so it is that I find myself recovering from three difficult surgeries in three months. Yeah, it’s been a lot.

There’s some good news, too. My heart is now whole. The breast tumor is gone, my lymph nodes were clear (two were removed), and the final lab report confirms I don’t need chemo. In three weeks I’ll begin radiation, followed by hormone treatment to help prevent a recurrence. I’m stretching through the lingering referred pain from the lumpectomry, re-learning how to reach my left arm above my head and how to put on a shirt. The melanoma is gone. I’m awaiting results from one more biopsy and, going forward, I’ll have a full body scan every three months for the rest of my life.

But this last surgery has been hard to come back from. The wound on my left leg is deep, wide, raw, and painful. For now, I spend much of the day lying on my back, with my leg propped up above my heart. Tomorrow I’ll begin a series of weekly placenta graft treatments meant to encourage healing. It will be a long road, a road I must travel by mostly staying put.

And so, I do have time to remember a few things.

I am remembering. . .

That a chaise lounge on a screened porch is a good place to spend a summer day.

I’m remembering that my grandmother never needed reminding. She spent her long-ago July afternoons stretched out in an old webbed lawn chair on her own small porch, ankles neatly crossed, size-five shoes always on her feet, a glass of sweet ice tea sweating on the table and a stack of McCall’s and Family Circle magazines at her side. As I think of her in my mind’s eye, I’m remembering she was probably younger than I am now,. I’m remembering that she seemed pretty old to me. I’m remembering that I have no memory of ever seeing my grandmother barefoot. I’m remembering she seemed content.

I’m remembering that reading a book with my head at the foot of the chaise, and my feet propped up on the back, makes me feel like a kid again. I remember I usually had a band-aid on my leg when I was ten, too.

I’m remembering that reading a book with my head at the foot of the chaise, and my feet propped up on the back, makes me feel like a kid again. I remember I usually had a band-aid on my leg when I was ten, too.

I’m remembering what it’s like to start a novel in the morning and to stay up late reading the last pages after everyone else has gone to sleep. I’m remembering what it’s like to have nothing else to do but read on a hot summer day. I’m remembering that if I have a book, I’m never bored.

I’m remembering what an empty day on the calendar looks and feels like. I’m remembering how long an afternoon can be. I’m remembering what it’s like to have no place to go.

I’m remembering that I can turn down my own bed in the middle of the day and it will still feel like a special treat when I return to climb into it at night.

I’m remembering that I can turn down my own bed in the middle of the day and it will still feel like a special treat when I return to climb into it at night.

I’m remembering the sweet peace of sleeping alone in a quiet room with the windows opened wide. I’m remembering the cozy comfort of stuffed animals sent by far-away friends. I’m remembering one doesn’t always need words to say, “I’m here.”

I’m remembering coffee in bed is lovely way to start a day.

I’m remembering how nice it is to let someone take care of me.

I’m remembering what it feels like to move very slowly, putting one foot in front of the other. I’m remembering how to be gentle with myself.

I’m remembering that a gift of flowers arriving at the door feels like a miracle. I’m remembering that a bouquet can last a long time if I cut the stems and change the water every day and pluck out each blossom as it passes.

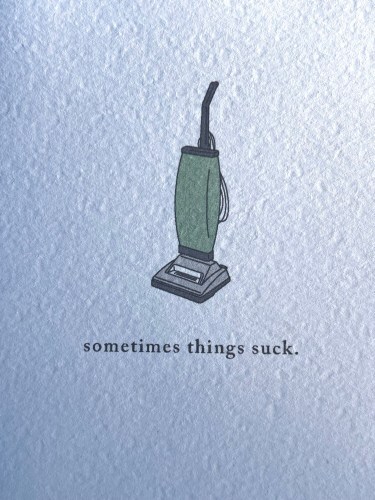

I’m remembering no one will die if the kitchen floor isn’t vacuumed.

I’m remembering that the light in the sky changes every minute. That clouds move from right to left. That I love watching birds take baths. I’m remembering that to spend a day looking out the window is not time wasted, it is time marked and honored. I’m remembering how to be.

I’m remembering that the light in the sky changes every minute. That clouds move from right to left. That I love watching birds take baths. I’m remembering that to spend a day looking out the window is not time wasted, it is time marked and honored. I’m remembering how to be.

I’m remembering I can ask for what I need.

I’m remembering that people want to be helpful. I’m remembering that help comes in all sorts of offerings. I’m remembering how to receive.

I’m remembering that a hand-written letter or a funny card in the mail with my name on it can be the high point of a day.

I’m remembering that a hand-written letter or a funny card in the mail with my name on it can be the high point of a day.

I’m remembering that gift certificates for take-out food are the best presents.

And that friends who bring dinner, or fresh-picked blueberries, or a new pair of pruning shears are also bringing love.

I’m remembering the simple pleasure of eating meals off a tray.

I’m remembering that at any given moment I can do what works. I can do what works for me.

I’m remembering I can leave my phone on silent even when I’m all alone. I can rest my mouth as well as my body. I’m remembering there is a kind of soul quiet required for healing, and that I can claim that quiet for myself.

I’m remembering that taking care of a wound is a little bit like taking care of a baby. Even when it’s not crying for attention, it’s always there, to be thought of and changed and attended to with clean hands.

I’m remembering that my body wants to heal. And I’m remembering that my body will never go back to how it used to feel or look or be. I’m remembering that even so, I’m all right. I’m remembering it’s ok to feel what I feel. And that grief for what’s lost is part of moving into what’s next.

I’m remembering that my body is on my side. That my job right now is to take care of this body with the utmost kindness. And to let the people who love me take care of everything else.

I’m remembering that my body is on my side. That my job right now is to take care of this body with the utmost kindness. And to let the people who love me take care of everything else.

I’m remembering that some situations are temporary. I will not always have a wound on my leg or stitches under my arm. I’m remembering pain goes away. And I’m beginning to accept that some situations are here to stay. I will always be a cancer survivor. I’m remembering that tomorrow is not a guarantee. That today is a gift.

I’m remembering how much I love watching birds take baths. And bees going about their business. And afternoon light passing through flower petals. And chipmunks who aren’t shy at all.

I’m remembering how much I love watching birds take baths. And bees going about their business. And afternoon light passing through flower petals. And chipmunks who aren’t shy at all.

I’m remembering that I love the way petunias spill out of their pots, the way cucumber vines wrap their tiny tendrils around anything nearby, and the way nasturtiums slowly make their way up the rusty old trellis. I’m remembering that things in nature just want to grow. I’m remembering the world can always astonish me with its beauty. And that all I ever have to do is look. I’m remembering the smell of the garden after rain, and the way robins sing at dusk, as if calling the darkness down.

I’m remembering that I love the way petunias spill out of their pots, the way cucumber vines wrap their tiny tendrils around anything nearby, and the way nasturtiums slowly make their way up the rusty old trellis. I’m remembering that things in nature just want to grow. I’m remembering the world can always astonish me with its beauty. And that all I ever have to do is look. I’m remembering the smell of the garden after rain, and the way robins sing at dusk, as if calling the darkness down.

I’m remembering that choosing to be happy here, now, is still a thing I can do for myself.

The post act of imagination appeared first on Katrina Kenison.

July 16, 2023

“choose an unimportant day”(and enter to win a book!)

I spent much of yesterday sitting in the chaise on my screened porch immersed in “Our Town.” Although it’s been years since I last read the play, there was a time when I knew every line of it by heart. Returning to Grover’s Corners now, on a languid summer afternoon, I was caught off guard by just how familiar it still feels and, at the same time, how alive and fresh and real. I certainly didn’t expect tears to blur the lines of the third act. It’s not as if there are any surprises there. And yet . . .

I spent much of yesterday sitting in the chaise on my screened porch immersed in “Our Town.” Although it’s been years since I last read the play, there was a time when I knew every line of it by heart. Returning to Grover’s Corners now, on a languid summer afternoon, I was caught off guard by just how familiar it still feels and, at the same time, how alive and fresh and real. I certainly didn’t expect tears to blur the lines of the third act. It’s not as if there are any surprises there. And yet . . .

As an awkward high school freshman with a tiny role in a community theatre production of a play I’d never heard of, I had no idea that Thornton Wilder was about to rock my world. I didn’t know that a few simple scenes played out on a nearly bare stage would profoundly shape the person I was becoming. And I certainly couldn’t have foreseen that, forty years later, I would be here – living in the town that inspired the play, sitting on a porch with that life-changing script in my hands, in a house that stands precisely halfway between the writers’ colony where Wilder wrote most of “Our Town” back in 1937 and the still-thriving summer theatre where he confided to the director of their first production, in 1940, that he never “meant that cemetery scene to be so depressing.”

All I knew back then was that I was drawn to theatre by a kind of hunger, the same way I was pulled into books — because I longed for something more, something I couldn’t even name but that hinted at the possibility of a life bigger and more exciting than the one on offer in my own small New Hampshire town.

Perhaps the stage would be my ticket out, or so I must have hoped when I showed up for that long-ago audition. Too young and inexperienced to play Emily, I was cast as George’s little sister Rebecca. By the end of the first read-through, I was in love with my brother.

Perhaps the stage would be my ticket out, or so I must have hoped when I showed up for that long-ago audition. Too young and inexperienced to play Emily, I was cast as George’s little sister Rebecca. By the end of the first read-through, I was in love with my brother.

And yet, in the end it wasn’t romance that jolted me awake and set me on my path toward adulthood. (Although that all-consuming passion – unrequited at first, briefly returned for one hot, heady adolescent summer, then mourned through the tortured pages of several years’ worth of mortifying journals — certainly did mark a rite of passage.)

What my heretofore oblivious fourteen-year-old self took away from our many weeks of rehearsals and performances in a small white church hall was both simple and shattering: a dawning awareness of life’s fleetingness.

Remarkably, the very mundane predictability that I was so eager to escape in my own boring life was the very stuff we were being asked to act out on stage – a mother calling her family to breakfast, a brother and sister annoying each other, children being hurried off to school, the nightly burden of homework, idle gossip and small talk about the weather, fathers coming and going from work, the relentless accumulation of gestures and meals and days that are just like all the gestures and meals and days that have come before.

By fourteen I had lost a Camel-smoking 58-year-old grandfather to a heart attack in his raspberry patch. But I had never so much as paused to consider the losses yet in store. Nothing felt precarious because nothing ever changed. And so, little wonder, nothing felt precious, either.

And then, night after night after night, I watched Lauri Landry (two years older than me and still, hands down, the best Emily I’ve ever seen anywhere) walk across the stage and take her place among the dead.

It is one thing to attend a play, applaud the cast, exit the theatre and return to your life. But it’s another thing entirely to live inside a play through months of rehearsals, run-throughs, and performances. For better or worse, the stark truth beneath the words enters you at a cellular level, becoming forever more a part of who and what you are – all the more so if you are as young, impressionable, and unformed as I was then.

Instead of getting bored with “Our Town,” or tired of hearing the same old lines repeated show after show, I had the opposite response. Every time I climbed the step ladder and looked at an imaginary moon alongside the first boy I had ever loved, it just brought us closer to the day when I would never stand on that ladder with him again. I could hardly bear to think of it. And every night, as Emily set foot back in her kitchen to relive her 12th birthday, begging, “Oh, Mama, just look at me one minute as though you really saw me,” I was there in the wings, grateful for the dark so no one could see the tears running down my face.

It wasn’t just that I was pining for a boy. It was that in the course of learning and living in and loving “Our Town,” I also got the memo: No one gets out of here alive. And once I had it, there was no way I could ever send it back. Life might be mundane, repetitive, and excruciatingly predictable, but it was also short and therefore beautiful, a fragile tapestry of joys, losses, irretrievable moments and inevitable heartbreak. Fail to pay attention, and I would miss the parts that mattered most.

Many years later, when my beloved friend Diane was dying of cancer at 55, far too young and painfully aware of all she would miss, I was struck both by her lack of self-pity and by her intense longing for what can only be called dailiness. If she’d had a bucket list, her husband would gladly have bought plane tickets to Timbuktoo. But all she wanted was more of what was slipping away – time to pick raspberries and put up a batch of jam, to take a walk with a friend, to bake a cake for her son’s birthday, to curl up on the couch and watch her favorite TV series through to the end, to see her daughter graduate from high school and her children get married and her grandchildren be born.

Of course, I got it. I looked at my own life, full of kids to shuttle around and meals to make and deadlines to meet, and wondered how I could have it so good while she was losing everything. And when I decided to try to write a book about change and grief and holding on and letting go, the title was the first thing I typed. In the midst of teenagers growing up, selling a house, and all of us moving from one state to another and starting over again, the title was the only thing I knew for sure. Thanks to Thornton Wilder and his play, I’d learned at a young age that when tragedy strikes or fate throws you a curve or life hangs in the balance, there’s really just one thing any of us want: the gift of an ordinary day.

Four years ago, when my friend Ann Patchett was on book tour with her novel “The Dutch House,” she stayed for a couple of nights in our guest room. Between her events in New Hampshire and Massachusetts, we did some yoga, took walks, and caught up with each other. As we strolled through town one mild October morning, I asked Ann if she had any ideas for her next book. She did, just the smallest seed of one. “I’m thinking I want to write a novel about a middle-aged woman whose life was changed by playing Emily in ‘Our Town’ when she was in high school,” Ann said. Or, at least, this is how I remember it. I do know I got a little too excited.

“Oh you must!” I exclaimed, immediately steering her toward Pine Street, where we could walk right past the houses known in local lore as Wilder’s inspiration for the Webb and the Gibbs family homes. And then I told Ann my own “Our Town” tale, complete with all the euphoria and heartbreak of that indelible first love. “Use any of it,” I said, pretty certain she wouldn’t use one bit. She was more than capable of making up her own story.

And yet, as Covid brought everyday life to a stop a few months later, and as Ann wrote a collection of essays instead of a novel, we checked in every so often about the “Our Town” book. It was taking shape in her mind, she reported from Nashville. And then, at long last, it was taking shape on the page. Here In Peterborough, with an almost eerie sense of Thornton Wilder hovering over this whole enterprise, I was urging her on, albeit, for mostly selfish reasons: I couldn’t wait to read it.

Which brings us to this full-circle moment. “Tom Lake” isn’t anything close to my “Our Town” experience (although there is a youthful love story, and Ann tells me her lost-boy heart throb is directly descended from my own). And yet I keep discovering little bits of both my younger and my older self myself within its pages. Perhaps this is the mark of a great piece of fiction: in a story about people who never existed, we discover some uncharted parts of ourselves and, in the process, become more fully cognizant of who we are – and more clear about what we’re here to do.

In a couple of weeks, Ann will embark on a 27-city book tour for “Tom Lake,” speaking and reading all across the country. But she’ll start right here in New England, and the two of us will get to sit down in person at last and have a good long chat about her beautiful novel. We’ll be on stage together in Concord, NH, on the evening of August 8 and we’d love to see you there. (Info and tickets are here.)

I read “Our Town” yesterday as self-assigned homework, to refresh my memory before our book event. But spending an afternoon back in Grover’s Corners refreshed my soul, too. It’s a very different play to me now, on the cusp of 65, than it was at fourteen. Despite the impression it made on me then, I know now, in a way no young girl possibly could, that one has to live some life and lose some people and grieve the passage of time in order to really appreciate “Our Town.”

I hope no one I love will ever need to plead “just look at me, one minute, as if you actually saw me.” And yet, I do forget to look. We all do. I forget to “realize life” as I live it, to be grateful for every ordinary moment, to pay attention to the beauty that is here, now. But after 36 years of marriage, with two sons in their thirties, two parents approaching ninety, and an ever-lengthening list of loved ones who are gone, I do my best to inhabit these days fully, gratefully, eyes wide open to the beauty of each beloved face. Nothing could be more important.

It’s 8 a.m. on a rainy Sunday morning as I type these words. In a few minutes, I’ll close my laptop and hop in the car and go pick up my father at the retirement apartment where he and my mom now live, on the other side of town. We’ll stand in line at the bakery till it opens and buy some warm sourdough bread to bring home. Not much of an outing, really, but it’s a chance to spend some time with my dad, something we both cherish.

Yesterday I found myself moved by a line near the end of “Our Town,” one I’d never paid much attention to before. When Emily, newly arrived in the cemetery on the hill, tells the Stage Manager she wants to return to her old life for just one day, a happy day, she’s interrupted by her mother-in-law, who has been dead long enough to know better.

“No!” Mrs. Gibbs warns. “Choose the least important day of your life. It will be important enough.” These are the words I’m taking to heart today. Maybe you will, too.

enter to win a copy of “Tom Lake”Publication date for “Tom Lake” is August 1. It will be my pleasure to buy a copy for Ann to personalize for one lucky reader. If you’d like to enter to win the book, just leave a note in the comments below. Answer the question: What ordinary moment will you remember from today? (Or, just say, “I’m in!). On August 1, I will choose one reader at random from the comments to receive a signed, personalized copy of “Tom Lake.” If you wish to order a signed copy, you can do so directly from Parnassus Books in Nashville, here.

And be sure to check out Ann’s entire tour schedule here. Chances are, she’ll be coming soon to a bookstore near you. Happy summer reading to all!

The post “choose an unimportant day”

(and enter to win a book!) appeared first on Katrina Kenison.

March 30, 2023

what a year brings

“In the midst of movement and chaos, keep stillness inside of you.” — Deepak Chopra

“In the midst of movement and chaos, keep stillness inside of you.” — Deepak Chopra

If I keep my eyes closed and listen, I could be five again. Tucked into the warm nest of early morning darkness, the blanket pulled to my chin, I drift, half awake, lulled by the familiar sounds of my parents in the next room. My father’s hushed voice. My mother’s brief, small cough. A shared laugh, quiet and intimate as a kiss. The clink of a coffee cup on the table. A murmured conversation punctuated by silences and then resuming, like waves rolling softly ashore. The two of them, their togetherness, now and always, for as far back as I’ve been alive. This, I know, is a kind of happiness. And so I give myself over to the sweetness of the moment, trying to take it in fully, to tuck it away for safekeeping so that someday I might gently take it out again, cup it in both hands, and remember.

Here’s a memory from long ago. I’m pretty sure I actually was five on this particular afternoon, which is to say I was old enough to know better and yet young enough, still, to be sent to my room after lunch for a nap, or a “rest” as my grandmother would have said in her kindly way, trying to make this despised solitary confinement a bit more palatable. (It occurs to me that if I was five my grandmother would have been 61, younger than I am now, although, to my child self she seemed very old. Funny, that, since to my own adult self at 64, I still feel young.)

I did not need to be tucked in, which meant there was no one there to see me climb onto the bed without removing my brand new patent leather Mary Janes. I scootched over to the far side and swung my legs up the wall, the better to lie back and admire my shiny new shoes with their thin straps and elegantly rounded toes.

The first black scuff mark, surely, was an accident. Who knew that the heel of a shoe would leave a dark, indelible print on a freshly papered bedroom wall? Not I. But there it was, in fact there they were, a pair of them. Two perfectly shaped half-moons had appeared beneath my feet as if by magic.

I’ve thought of this moment so many times over the course of my life, that hovering instant between innocence and guilt, when I could have called out to my grandmother, confessed my mistake, apologized, and offered to take a damp cloth to those two small marks amid the pale pink flowers on her guestroom wall.

But for some reason I could not fathom then or now, I did not call out. Whatever shock or remorse I might have felt with the first two black marks yielded to a more powerful, primitive impulse. Slowly, quietly, with a kind of mindless determination, I began to scissor my legs back and forth against the wall. When one area was done to my satisfaction, I shimmied myself over to the next clear space and carried on, until the entire expanse of wallpaper along the bed was covered with my terrible handiwork, a shocking constellation of black heel prints and tiny roses.

I don’t remember how I was punished for this act of desecration, although I most surely was. Oddly, I don’t remember anything else about my crime or its aftermath except the sense of having been almost unconscious while committing it, and then the dawning horror as my brain switched back on and I absorbed the full import of what I’d done. My budding conscience had failed me completely.

Perhaps my grandmother was able to wash away the marks, but honestly, nearly sixty years later, I have no idea. What remains indelible is the memory of my own wickedness followed by a tidal wave of embarrassment and regret. I’m pretty certain I decided, then and there, that going forward I would be good. Shame is transforming, and I was most certainly shaped by it that day. There would be no more black marks on walls, nor on my record, of that I was certain. It might have been the first entirely self-aware decision of my life.

When my grandparents died and their house was sold, the small spindle bed in which I spent so many nights of my childhood was one of the few pieces of furniture my mother kept. She had slept in it herself as a child. Rather than send the bed off to Goodwill, she had my dad take it apart and tuck it away in the attic. Maybe, someday, it would be of use again.

And so it is.

I didn’t intend, when I last wrote here in February of 2022, to let a whole quiet year go by. I’m tempted to say life got complicated and I got busy and to leave it at that. But the truth is a bit more nuanced. So many things began to shift and change over the last year that I couldn’t imagine writing about events as they unfolded. For the first time ever, I had no desire to write at all. It was all I could do to show up and live each day with some attempt at presence and grace.

But now, as the winter’s last snow melts and the first green shoots push their way through the damp earth, I find my writerly self tentatively stirring to life, too. Yes, there’s more to say than can possibly be put into a blog post. But my friend Jena’s recent email entitled “What Goes Into a Week” inspired me to make a short list of my own. It’s not everything, not by a long shot, but it feels like a way back onto the page and, I hope, back into our conversation here, which I’ve missed very much

This year brought upheaval, sadness, and loss around my parents’ painful but wise decision to leave their beloved home and move into an apartment in a retirement community. It brought me their beautiful house to care for and manage. It brought grief every time I walked through their door, only to be reminded that my mom was no longer puttering in the kitchen, that my dad wasn’t reading in his chair, that they were no longer there at all. It brought the emotional work of learning to be in their house without wishing to roll back time.

This year brought me a new job, of landlord, and a succession of renters who have become friends. It brought me a sense of my own mortality and many questions about what’s next.

This year brought ripples and repercussions from both of our grown sons’ challenges. It brought struggles with depression, anxiety, hearing loss, and addiction. It brought healing, sobriety, and fresh starts. It brought each of them home for long visits.

This year brought Jack back to live with us for seven months and it brought the unexpected but welcome development of him taking a job in his dad’s business. It brought his dog Carol into all our hearts. It brought him to settle into an apartment nearby and to renewed connections with his grandparents. This year brought Henry a permanent position as a college professor, a newfound resilience, self-confidence, and certainty about his path.

There were hard times. There were sleepless nights and difficult conversations. There was also healing, growth, and a deeper kind of honesty.

This year brought many, many family gatherings. It brought dinners around the fire, dinners on the porch, breakfasts with my dad, long heart-to-hearts with my mom, long walks with everyone, a full house from June through February, and more shopping and cooking than I’ve ever done in my life.

This year brought broken pipes and gutted walls and weeks of mess. It brought drought-damaged lawns and brutal blizzards and too many days without power. It brought the grim task of throwing away every single thing in the refrigerator, followed by the pleasure of starting over again from scratch.

This year brought spectacular sunrises, sunsets, and rainbows, a nest of baby robins, a garden full of hummingbirds, bees, and butterflies. The best peonies ever. Home-grown salads from May through November. The driest summer. The loveliest fall. Beauty and destruction, all of which, of course, are part of life

This year brought a leisurely week with my husband exploring E.B. White country along the coast of Maine. It brought a joy-filled hiking and stitching adventure to England with my soul daughter, a visit to New York City and a long-awaited return to Broadway shows with Henry, a week in a cabin on a lake with my mom, an 87th birthday party for my dad.

What I remember most, looking back, are these moments of togetherness and happiness, all the many reasons we found to pinch ourselves, celebrate, and give thanks.

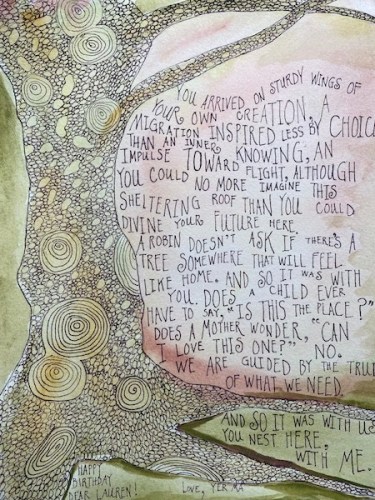

This year brought Covid. Or, rather, Lauren and I brought Covid back with us from England. Everyone in the house got the virus, and I was sick on my birthday, but at least we were all quarantined under one roof. My parents gamely came over for a chilly outdoor visit and Lauren made me a cake and strung balloons in my bedroom and made sure I felt pampered and cherished and showered with love.

This year brought many reminders that families are defined not by blood so much as by the strength of connections woven over time, by a mutual commitment to truth and kindness, by a sense of kinship and a willingness to show up for each other, come what may. This year brought tensions of all kinds and, in the end, it brought tighter family ties, both chosen and biological.

This year brought some painful reckonings and necessary revisions to a 35-year marriage. It brought renewed commitment and a clearer sense of where to compromise, when to stand firm, how to let go. It brought, on my part, some deep personal work that has both shaken me and strengthened me in ways I continue to explore. It brought me my Enneagram type (Number 9, the Peacemaker). It brought me much needed hope and hard-won clarity. I’ve learned a lot.

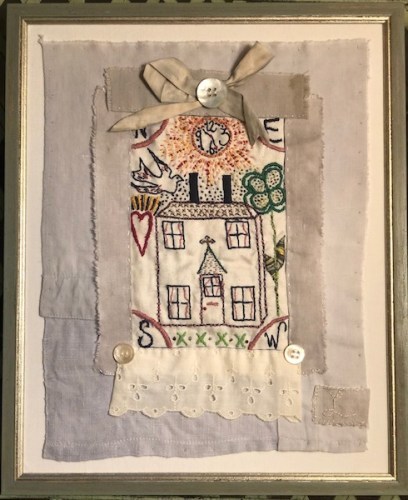

This year brought thousands of tiny stitches in cloth. In a world that often seems to be moving too fast, I’ve found respite in slowness, beauty in softness, and delight in using my hands in a simple, practical way. Sitting quietly with my needle and thread has become both a creative outlet and a profoundly healing way to connect with my own quiet center.

This year brought the little girl who once wreaked silent havoc at naptime back to sleep in that very same bed, nearly sixty years later. It brought a sense of just how long it takes to become the person one aspires to be. It brought the unanticipated delight of getting to be a guest in my parents’ new apartment, of having them all to myself at dinner, and then hugging them each goodnight and going off to stay in a lovely little room down the hall. It brought me a chocolate on my pillow (thank you, Mom), and coffee delivered by my early-rising dad as soon as he saw my light flick on at 6. It brought the full-circle moment that inspired me to write this essay.

This year brought a deeper awareness of life’s fleetingness. It brought me to my knees and it made my heart soar. And along the way it tested me as a mother, as a daughter, as a wife, as woman. This year brought powerful reminders that to live in this world is to learn how to meet what is painful even as we choose, again and again, to turn toward what is beautiful and good and lasting. And that, of course, is love.

The post what a year brings appeared first on Katrina Kenison.

February 24, 2022

we remember moments

The days, at last, are lengthening. When I step outside for the sunrise now it’s both earlier and noisier. The birds, including a few hardy robins and bluebirds, are back and they are busy calling spring into being. We’re a long way from thawed earth and green shoots in New Hampshire, but after a winter we’ll remember more for ice than snow, the soft, verdant world will come round again. I’ve ordered seeds. And yesterday I snipped a few leggy pussy willows from the suddenly abundant bush in our swampy north field. There’s something fresh and hopeful in the air.

The days, at last, are lengthening. When I step outside for the sunrise now it’s both earlier and noisier. The birds, including a few hardy robins and bluebirds, are back and they are busy calling spring into being. We’re a long way from thawed earth and green shoots in New Hampshire, but after a winter we’ll remember more for ice than snow, the soft, verdant world will come round again. I’ve ordered seeds. And yesterday I snipped a few leggy pussy willows from the suddenly abundant bush in our swampy north field. There’s something fresh and hopeful in the air.

It’s been nearly two years since our world went into lockdown. Just typing those words gives me pause. Can that be right? Has it really been only two years? In many ways those innocent “before” times feel like another life altogether, busy and distant, an existence I naively took for granted — right up until the moment every store in town went dark, every plan large and small was canceled, and people began anxiously tracking Covid numbers the way we follow winter storms and wild fires.

Maybe the epidemiologists could see the writing on the wall back in March of 2020. But as we all embarked on our vast, unprecedented indoor vigil no one else had any idea how much devastation was in store. How could we have begun to imagine such heartbreak, illness, outrage, confusion, disinformation, worry, fear, and loneliness? Not to mention death. We can turn away from the still-rising tally (936,000 as of today) but not from the ripples of so much heartache. Grief has become the silent undercurrent of our days, a collective, relentless, unassailable tide of loss.

As this unsettling spring arrives, it seems that nearly every conversation I have with friends is limned by both gratitude for what remains and for lessons learned, mourning for all that is no more, and uncertainty about what may yet be around the corner. We’re so ready for Covid to be over. But no one’s under any illusion that Covid is done with us. The mask mandates may be disappearing, but we are not the same people we once were, nor are our lives really going back to “normal,” whatever normal was.

And yet, if we’re lucky our lives are ongoing. And if we’re wise, we will proceed now not with abandon but with some workable combination of hope, compassion, and caution. Therein lies both the gift of this precarious time and its challenge. Never have I been more aware of how fragile life is. Never have I been more attuned to its beauty and wonder, either. And never have I felt such an urgent call to pay attention to what matters.

It is, I think, this desire to be awake to the shifting subtleties of life and conscious of its brevity that is helping me envision my own way forward, forward through my sixties and into years I’m determined to embrace but that will surely be defined by even more challenges — losses both anticipated and completely unforeseeable.

It is, I think, this desire to be awake to the shifting subtleties of life and conscious of its brevity that is helping me envision my own way forward, forward through my sixties and into years I’m determined to embrace but that will surely be defined by even more challenges — losses both anticipated and completely unforeseeable.

Do you know the famous line from the movie August: Osage County, “Thank God we can’t tell the future, we’d never get out of bed”? We laugh because it’s true, and yet get up we do, every single day, because the world in all its mystery and splendor awaits.

I get out of bed for the first cup of hot coffee in the morning. And for the Wordle text thread spanning three generations – my mom, my brother and me, my son Henry — which often begins before 5 a.m. with results from whoever couldn’t sleep last night. I get out of bed to greet the sun as it silently slips into view above the mountains, to see the red squirrel on his perch on the stone wall, the dawn light splashing across the floorboards, the goldfinches and woodpeckers at the feeders, my husband reading the newspaper at the table, the new day getting itself underway. I get up because, no matter how dark the night may be, every new morning arrives like a gift waiting to be unwrapped, gratefully received, and put to good use. “At some point,” as Toni Morrison writes, “the world’s beauty becomes enough.”

I get out of bed for the first cup of hot coffee in the morning. And for the Wordle text thread spanning three generations – my mom, my brother and me, my son Henry — which often begins before 5 a.m. with results from whoever couldn’t sleep last night. I get out of bed to greet the sun as it silently slips into view above the mountains, to see the red squirrel on his perch on the stone wall, the dawn light splashing across the floorboards, the goldfinches and woodpeckers at the feeders, my husband reading the newspaper at the table, the new day getting itself underway. I get up because, no matter how dark the night may be, every new morning arrives like a gift waiting to be unwrapped, gratefully received, and put to good use. “At some point,” as Toni Morrison writes, “the world’s beauty becomes enough.”

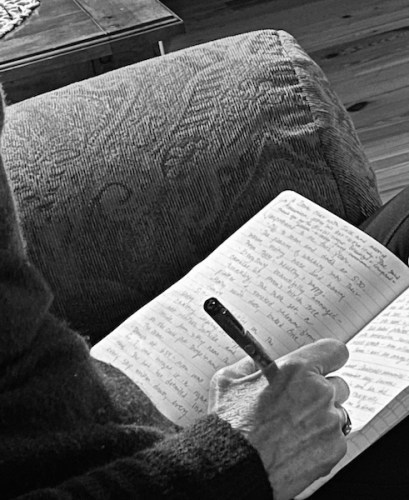

For the first year of the pandemic, I kept a nightly journal, jotting down a few random snippets from my day. These notes weren’t crafted, just a kind of bullet-copy record of everything from the weather to the news headlines to what flower had bloomed in the garden. By the time I’d filled a notebook with, what seemed to me, a bunch of dull, repetitious pages, I wondered if there was any point to this exercise in accounting. It wasn’t real writing. It served no real purpose. And the truth was, when I finally got into bed and picked up my pen at the end of each long, unexciting day, I was pretty much done with putting out effort of any kind. Why spend twenty minutes jotting down that I’d cleaned the woodwork, had lunch with my parents, and taken my hundredth walk? Why not just scroll through some Instagram photos of embroidery and English gardens and then escape into sleep? And so, a few pages into the second year and my second notebook, without really thinking about it, I stopped.

The other day I came across these journals in a drawer. What a surprise it was to discover in their pages not tedious accounts of boring pandemic days but a trove of memories I want to keep, countless small moments that surely would have vanished had I not taken the time to write them down. What a loss, I thought to myself, as I looked at all the empty pages I’d never bothered to fill.

And so as this anniversary that no one wants to celebrate approaches, I’m renewing my commitment not only to notice these fleeting moments, but to record them, too, if only to remind myself some day in the future of all that is right here, right now.

I want to remember my father’s 86-year-old hands, so much like those of his mother, bent with arthritis yet gracefully peeling a potato with as much care and precision as they once wielded dental instruments, shaped crowns, and sutured the delicate tissues in his patients’ mouths.

I want to remember my mother setting a bowl of her homemade vegetable soup on the table for me, and eating lunch with my mom and dad as snow swirls outside the windows and a lone skater sails across the ice on the pond across the road.

I want to remember three linen napkins, three glasses of water, the three of us together, enjoying one another’s company. I want to remember how grateful I am to still be a daughter at my parents’ table on a winter afternoon.

I want to remember a long cold walk with my son Jack’s voice in my ear telling me about taking his girlfriend out for dinner, his happiness with his life, our easy affectionate connection. And that, even on a day when the high is seven degrees, I bundle up, put on hat and mittens, and head outside anyway.

I want to remember a long cold walk with my son Jack’s voice in my ear telling me about taking his girlfriend out for dinner, his happiness with his life, our easy affectionate connection. And that, even on a day when the high is seven degrees, I bundle up, put on hat and mittens, and head outside anyway.

I want to remember reading an important letter my son Henry sends me to edit, the unexpected flush of pride as I see him not as my kid but as the experienced college professor he has become. I want to remember calling him back to say I wouldn’t change one word.

I want to remember winter nights in front of the fire with Steve, our dinners balanced on our laps, the sheltering sense of home as we sit together on the couch sharing the small events of the day as we have for thirty-five years of married life. I want to remember that, even as we drink wine and count our blessings, we also speak of endings and sadness, and of how hard it is to let go of anything that’s loved.

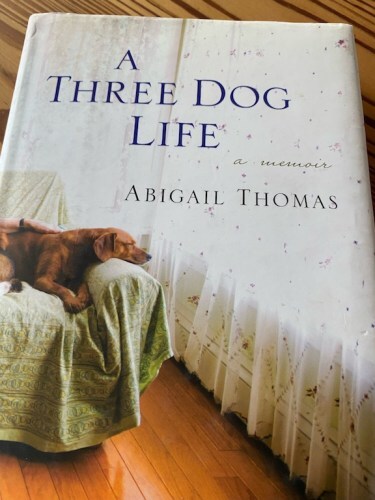

I want to remember finding a package containing Abigail Thomas’s A Three Dog Life in the mailbox. I want to remember that this is what love feels like: an unexpected gift from my soul daughter Lauren, sent simply because she knows how much I adore this profoundly moving little book and that I’ve somehow lost my own cherished copy.

I want to remember finding a package containing Abigail Thomas’s A Three Dog Life in the mailbox. I want to remember that this is what love feels like: an unexpected gift from my soul daughter Lauren, sent simply because she knows how much I adore this profoundly moving little book and that I’ve somehow lost my own cherished copy.

I want to remember that, when I tell Lauren I’m writing about moments, she reminds me that we humans are here not only to notice moments, but to create and hold them for one another, too.

And so it is that we who attune our eyes to look for moments also delight in bestowing small moments on someone else: A love note written and hidden in the pantry to be discovered behind the flour bin; a filthy, salt-encrusted car washed and returned to the garage without a word; a quick dance in the kitchen; grilled cheese sandwiches cut into quarters and served with pickles on the side; a poem shared or a photo sent of a found heart or a face in the pavement; a stash of new pens left on a kitchen counter; a foot rub with lotion at the end of the day; a surprise bed turn-down with a pair of PJs arranged just so; a few kind words exchanged with the cashier at the grocery store; a story recalled from the distant past and shared with someone who might have to remember it for you someday, long after you are gone.

And so it is that we who attune our eyes to look for moments also delight in bestowing small moments on someone else: A love note written and hidden in the pantry to be discovered behind the flour bin; a filthy, salt-encrusted car washed and returned to the garage without a word; a quick dance in the kitchen; grilled cheese sandwiches cut into quarters and served with pickles on the side; a poem shared or a photo sent of a found heart or a face in the pavement; a stash of new pens left on a kitchen counter; a foot rub with lotion at the end of the day; a surprise bed turn-down with a pair of PJs arranged just so; a few kind words exchanged with the cashier at the grocery store; a story recalled from the distant past and shared with someone who might have to remember it for you someday, long after you are gone.

“We do not remember days, we remember moments,” the Italian writer Cesare Pavese reminds us. As I look back on the last two years – years in which the days easily blurred together and my sense of time was often muddled by monotony — it is the small moments that remain luminous in memory, moments I might easily have missed had I not been learning to see more and more deeply into what has been here all along.

“We do not remember days, we remember moments,” the Italian writer Cesare Pavese reminds us. As I look back on the last two years – years in which the days easily blurred together and my sense of time was often muddled by monotony — it is the small moments that remain luminous in memory, moments I might easily have missed had I not been learning to see more and more deeply into what has been here all along.

There is so much we don’t know. But I do know this: In choosing again and again to keep my focus close, on the here and now, I find my footing, my best self, my happiness. “To pay attention,” as Mary Oliver suggests, “this is our endless and proper work.”

This afternoon, the last of the snow that covered the ground when I began writing this essay vanished. The temperature reached 55 degrees and I tied my coat around my waist, swept a winter’s worth of sand out of the garage, and filled the birdbath so everyone could have a quick dip before tomorrow’s expected storm arrives. We could have a foot of snow by Friday afternoon, but today a tiny pansy showed its face to me. And that feels like something worth jotting down tonight before I turn out the light.

a few more thingsWe are here to witness creation and to abet it. We are here to notice each thing so each thing gets noticed.

Together we notice not only each mountain shadow and each stone on the beach but, especially, we notice the beautiful faces and complex natures of each other.

We are here to bring to consciousness the beauty and power that are around us and to praise the people who are here with us.

We witness our generation and our times.

We watch the weather.

Otherwise, creation would be playing to an empty house.”

~ Annie Dillard

If you read last month’s blog and were inspired to buy a copy of Oliver Burkeman’s life-changing book Four Thousand Weeks: Time Management for Mortals, you no doubt discovered it was out of stock everywhere. Clearly, his message is resonating. And, happily, the book has been reprinted and is available once again. You can order a copy here.

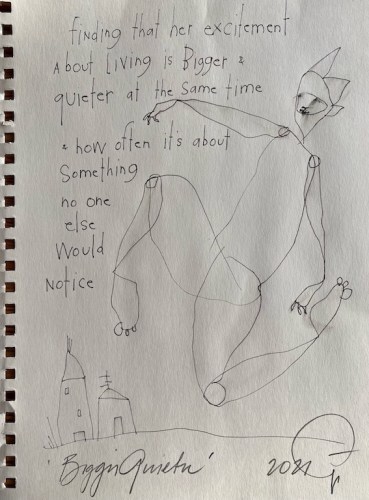

I adore the work of Kai Skye (aka Brian Andreas) who, with his partner Fia, sends out a daily dose of art and wisdom in a note they call “A Story Every Day.” It’s one more wonderful thing to get out of bed for. The sketch above is an original from Kai’s notebook, which I bought because the words describe exactly how I’m feeling these days. But the truth is, their offerings always illuminate my inner landscape and invite more reflection. You can see more at their website, Flying Edna, and sign up to receive their stories, here.

When I think of the books I return to as if for visits with old friends, Abigail Thomas’s three memoirs are high on the list. She is wise and funny and bracingly honest. Her writing is sublime. Her three memoirs follow the arc of her life, a narrative that is built of fragments or, one might say, moments. But oh, how those moments add up to something so much greater than the sum of their parts. Her first memoir, Safekeeping, is the place to start. A Three Dog Life comes next, followed by What Comes Next and How to Like It. Nothing makes me happier than connecting good books with grateful readers, so spreading the word about Abigail is my pleasure. (Click on any of these titles to order on Amazon; these are affiliate links).

The post we remember moments appeared first on Katrina Kenison.

January 17, 2022

four thousand weeks, and 365 seconds

Standing there in the wind and the sound of the trees, remembering she is here with all of it for only a short while. ~ kai skye

Standing there in the wind and the sound of the trees, remembering she is here with all of it for only a short while. ~ kai skye

As I begin to write here for the first time in many months, I’m a little uncertain about how to break such a long silence, a silence that’s been full of days lived and feelings felt, if not of words written and thoughts shared.

And then I remember that most of us are in the same boat, having crossed the threshold into yet another year of pandemic anxiety, political turmoil, and private stress, grief, and frustration. If ever there was a moment to reach out a hand and say, “I’m still here, I hope you, are, too,” this is it.

And so, hello there. I’ve missed you. It’s lovely to think about this short note flying out into the world and landing in your email box.

We’re halfway through January and in the midst of our first really cold spell of winter in New England. There are a few more minutes of light each day, but it was 5 below zero as the sun came up this morning and it was minus 2 just now when I dashed out to fill the birdfeeders. When my husband asked at breakfast what I’m looking forward to, I paused on my fourth Wordle guess and struggled to come up with an answer. Lunch?

Perhaps you, too, are hitting an invisible wall this month. We’ve been here before, masked up and keeping our distance. But there’s a kind of resignation and weariness creeping in this winter that feels new. Even a little news feels like too much craziness and chaos to process. There are so many reasons to despair and so few glimmers of hope. Meanwhile, hunkered down at home with one bitterly cold day sliding into the next, it seems almost pointless to make future plans. Why get attached to anything? Just figuring out what to do with the day at hand can feel like a cruel reminder of all that was possible once but is no longer.

For many of us there seems to be an unsettling disconnect between the surging virus cases and the number of people who continue to shop and dine and socialize as if Covid is history. And yet, with two parents in their mid-eighties who most definitely must not get sick, I’m being more careful now than ever. Seeing them, and ensuring that we all feel safe being together, means not seeing anyone else. To my husband and me this extra bit of caution feels like an obvious choice, not only for my parents’ sake but for the common good. Our tiny local hospital is currently overwhelmed with Covid patients. Meanwhile, even here in our small town there’s a sense that people’s beliefs, habits, and priorities are becoming more polarized. It’s going to be a long winter.

As I ordered two packages of N95 masks this morning, I was relieved they’re finally easy to find, and also a little sad to realize how accustomed we’ve become to this crazy quilt of unease and loss that defines life in 2022 – a state of affairs we couldn’t have begun to imagine two years ago. So much of our social fabric is unraveling at once – our embattled democracy, voting rights, the integrity of the Supreme Court, our healthcare system, our schools, the supply chain, the climate, even the most basic agreements about what’s true, what matters, and how we human beings should behave toward one another at the grocery store. No wonder everything at this moment feels particularly fraught.

And yet, it is perhaps because of this recognition of just how precarious things are, that I also find myself with a heightened sense of how precious life is. As author Oliver Burkeman observes, “The more that you remain aware of life’s finitude, the more you will cherish it, and the less likely you will be to fritter it away on distractions.”

I’ve been thinking about the truth of these words a lot this month.

If, as it is said, grief and gratitude go hand in hand, then surely these pandemic years have given us all a starker, deeper appreciation for life’s finitude. How could it be otherwise, when over 62 million Americans have been ill with Covid and over 800,000 of us have died? To absorb this reality is to recognize another one: we’re all vulnerable. Tomorrow is not a given, no one’s future is guaranteed, and all our dreams are provisional. Anything could happen.

Knowing this, in a way we couldn’t possibly have known it before, isn’t exactly comforting. (Taking an informal poll among my family and friends confirms this: no one’s sleeping well these days.) But confronting the truth of my own mortality also feels like a wake-up call, an incentive to examine my relationships, my activities, and especially my attitudes, in a new light. How do I really want to spend my days? How can I create a life that’s more joyful, more connected, and more meaningful in whatever time I do have?

Perhaps there’s a way to see in our collective pandemic trauma not only the darkness, which is all too real, but also a message that I, for one, have very much needed to hear: I can’t change the big picture, but I can choose where to put my attention, my energy, my creativity, my love. I can lose another night’s sleep over all that’s wrong in the world, or I can honor all that’s been lost by making a commitment to live more compassionately, more playfully, and more gratefully right now.

Before, I took so much for granted, especially time. How easy it was to fool myself into thinking life would continue as it always had, spooling out endlessly through the decades, twisting and turning, but ongoing. Now, at 63, I’m older than some of my dearest friends ever got to be. Watching my parents gamely navigate an array of health challenges, I also see how grateful they are for every uneventful day. (They never complain about the hard ones, either.) And finally, I do get it: even if we’re one of the lucky ones, life is still too short.

In fact, as Burkeman reminds us, “The average human lifespan is absurdly, insultingly brief. Assuming you live to be eighty, you have just over four thousand weeks.” The number certainly gives me pause. And Burkeman’s profound, beautifully written and reasoned book, aptly called Four Thousand Weeks: Time Management for Mortals, feels like a light on the path, showing us a thoughtful way forward. Suddenly the question I’m asking isn’t, “When will this all end?” but rather, “How can I make this day a good one?”

If I’ve learned anything from these last two years — so full of sadness and fear, yet memorable as well for all their moments of unexpected beauty and of grace — it’s this: I won’t ever get a single one of my own weeks back. They’ve flown. If I live another twenty years, I have just over a thousand weeks to go, a thousand weeks to treasure or squander. The take-away is so painfully obvious I can’t believe it’s taken me so long to see it: Any time I spend wishing for things (or people!) to be other than they are is time wasted.

So why not figure out for myself, moment to moment, what matters now? Why not devote more time to the things that feel meaningful or that bring me joy, and less to worrying about all that’s out of my control? I may not be able to solve big problems, but I can solve little ones. I can care for my own small corner of the world, and for all the people and creatures with whom I share this place, this home, this unprecedented time. In the face of all the things I can’t change, I can emphatically choose, moment by moment, to embrace my life and my loved ones as they actually are – imperfect, mysterious, lovely, heartbreakingly mortal.

Easier said than done, yes. And of course I’m talking to myself here. But as soon as I begin paying closer attention to where my attention goes, there’s a subtle shift. I’m a little more here, a little less anxious and distractible, and far more certain that gratefulness is more than a passing emotion, it’s the spiritual work of a lifetime. If I’m fortunate enough to get another thousand weeks, I want to do my best to make them count.

Already the morning has flown by. There’s nothing special here, just an empty house, a few quiet hours, my fingers hovering over the keyboard. And yet, what a luxury it is, this gift of time. What I do with it is entirely up to me. The sunlight on the dining room table was so lovely a few minutes ago that I stood up from my laptop and snapped a picture. And now, already, the room is bathed in shadow. If I hadn’t looked up just then, I would have missed it. I could carry on writing for a while longer, but I could just as easily, just as happily, spend the rest of the morning watching the nuthatches and chickadees come and go outside the window. I could bundle up and take a walk or I could call my mom and offer to bring lunch over. Upstairs, my sewing project awaits. As does the book on the bedside table. There are bills to pay, a letter to write. I put laundry in after breakfast, but I haven’t done the vaccuming yet. The possibilities are infinite, but the hours in this day are not.

Already the morning has flown by. There’s nothing special here, just an empty house, a few quiet hours, my fingers hovering over the keyboard. And yet, what a luxury it is, this gift of time. What I do with it is entirely up to me. The sunlight on the dining room table was so lovely a few minutes ago that I stood up from my laptop and snapped a picture. And now, already, the room is bathed in shadow. If I hadn’t looked up just then, I would have missed it. I could carry on writing for a while longer, but I could just as easily, just as happily, spend the rest of the morning watching the nuthatches and chickadees come and go outside the window. I could bundle up and take a walk or I could call my mom and offer to bring lunch over. Upstairs, my sewing project awaits. As does the book on the bedside table. There are bills to pay, a letter to write. I put laundry in after breakfast, but I haven’t done the vaccuming yet. The possibilities are infinite, but the hours in this day are not.

Soon, too soon, the sun will set. Steve will come home, we’ll make dinner and eat by the fire, do the dishes, perhaps talk to a grown child or two, watch the last episode of Ted Lasso, and make our way upstairs to bed. Moonlight will spill across the quilt, the heat will come on, I’ll slip an arm around my husband and listen in vain for the sound of Tess’s soft snore.

It’s been two months since our sweet border collie died, but not a night passes when I don’t wish I could fill her water bowl by the bed, stroke her silky head, and gaze into her eyes just one more time before saying good night. Missing her is yet another reminder that nothing lasts. “Time, then,” as poet Wendell Berry reminds us, “is told by love’s losses, and by the coming of love, and by love continuing in gratitude for what is lost.”

And so it is that I, who have spent my entire adulthood celebrating ordinary days, find myself both hungry for more of them and, too, more determined than ever to make good use of all the days I have left.

What am I looking forward to? When I take a moment to really consider that question, the answer is obvious: Everything.

the book, and the secondsThe moments may be fleeting but I’m always trying to find a way to hold them in my hands just a little longer. No wonder I fell in love with the brilliant 1SE app – it allows you to stitch together the seconds of your life as they fly by. On January 1, 2021, I began capturing moments in my garden as they unfolded, with just one photo or one second’s worth of video a day.

On days when I was away from home (usually at our family house in Maine) I’d simply take a photo of nature where ever I happened to be. The result, just six minutes long, is so much more than I ever could have imagined when I began – both a powerful reminder of the inexorable passage of time and an intimate engagement with the world as I found it, day by day, for an entire year.

“There are two ways to live your life,” Einstein said. “One is as though nothing is a miracle. The other is as though everything is a miracle.” Clearly, I’m in the second camp. It’s a joy for me to share these glimpses of my two favorite places with you, the garden where we live and the piece of the Maine coastline that holds 45 years worth of our family’s happiest memories. If you can, watch on a large screen. Turn the sound up to catch the birds, the rain, the hum of bees.

Four Thousand Weeks: Time Management for Mortals

My friends may be tired of hearing me sing the praises of Oliver Burke’s wise, wide-ranging, life-changing book Four Thousand Weeks. But so far every one who’s read it has been just as inspired as I am. If you’re longing to live more joyfully, more mindfully, and with less stress, Oliver Burke offers plenty of ideas. In the process, he invites us to renegotiate our entire relationship with time and the way we inhabit it. Hint: You’ll probably want to own this book, so you can highlight your favorite passages with abandon. And please let me know what you think!

You can order a copy here. (This is an Amazon affiliate link.)

Listen to an engaging “On Being” conversation between Krista Tippet and Oliver Burke here.

The post four thousand weeks, and 365 seconds appeared first on Katrina Kenison.

April 14, 2021

we are all mothers this year

Be the one who, when you walk in,

Be the one who, when you walk in,

Grace shifts to the one who needs it most.

Even if you’ve not been fed,

Be bread.

~ Rumi

Spring is coming here in New Hampshire, but slowly. In my garden the first blooms of delicately hued hellebores and sunny daffodils are welcome reminders that we really are emerging at last. For both plants and people there are better, brighter days ahead. And yet, after all we’ve been through during this long hard year, perhaps it’s only natural to find ourselves stepping hesitantly into the new season. The weather app predicts six inches of snow on Friday. And although I got my second vaccine yesterday, when I think about actually resuming anything like normal life, questions abound. What will the next chapter look like and how will it feel? Who have I become during these months of separation, uncertainty, and loss?

Thinking back over the many dinners I’ve made, the countless hours engaged in long heart-to-heart conversations with loved ones far away, the joy I found in spending time with my parents and the pain of not seeing our son Jack for well over a year, it occurs to me that while some things have certainly slipped away (old grudges, taking anything for granted, and recreational shopping, to name a few), other qualities have grown stronger. Perhaps it was because so much was under threat and siege that we who nurture by nature became even more fierce in our caring, more determined than ever to mend, as Clarissa Pinkola Estes so aptly puts it, “the part of the world within our reach.”

The truth of this was brought home to me as I read each of your heartfelt, stunningly powerful comments in answer to the question I posed in my most recent blog, “What have you made this year?” Your answers covered the entire gamut of loving and healing, caring and creating, giving and accepting, mourning and celebrating.

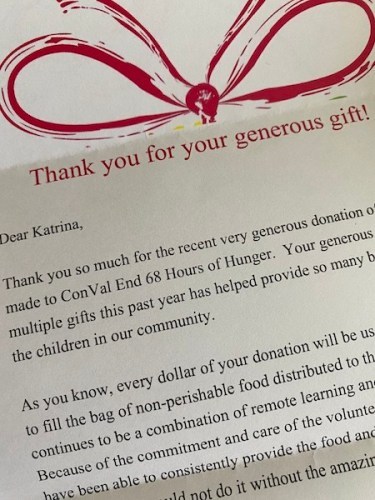

You made masks and donations, quilts and meals and loaves of bread, 8 million stem cells for a sister’s bone marrow transplant and new babies to cherish, safe homes for rescue dogs and struggling teens and terminally ill partners, loving places for elderly parents, milkweed gardens and pottery bowls, Zoom choirs and online support groups and a podcast from a closet. Inner peace. Room to mourn. Reasons to hope. So much love and courage and grace and nurturing.