Katrina Kenison's Blog, page 2

November 21, 2020

comfort, conversation, and books to get us through

Winter is coming. And this year, even before the temperature drops below zero in New Hampshire, it’s already feeling colder and, let’s just say it, a good bit darker than usual. For many of us who have been lucky enough to be able to stay home since March, the sameness of the days has been a small price to pay for living with less risk. Over the summer there were actually weeks when I barely gave the pandemic a thought. With an ambitiously planted garden to tend, long walks to take, and leisurely family dinners to savor on the screened porch, it was possible to forget, every now and then, that we were homebound for a reason. Other than slipping on a mask to go the grocery store and washing my hands every twenty minutes (a habit now ingrained forever), life at home in July and August could resemble something close to normalcy, albeit a quiet, isolated normalcy. That, I know, was a matter of both privilege and luck.

Winter is coming. And this year, even before the temperature drops below zero in New Hampshire, it’s already feeling colder and, let’s just say it, a good bit darker than usual. For many of us who have been lucky enough to be able to stay home since March, the sameness of the days has been a small price to pay for living with less risk. Over the summer there were actually weeks when I barely gave the pandemic a thought. With an ambitiously planted garden to tend, long walks to take, and leisurely family dinners to savor on the screened porch, it was possible to forget, every now and then, that we were homebound for a reason. Other than slipping on a mask to go the grocery store and washing my hands every twenty minutes (a habit now ingrained forever), life at home in July and August could resemble something close to normalcy, albeit a quiet, isolated normalcy. That, I know, was a matter of both privilege and luck.

But with the virus surging across the land and cases in our small community on the rise for the first time, winter arrives this year with a menacing shadow. The other day my friend, gardener, writer, and popular podcaster Margaret Roach and I were chatting about how we might make it through this long season of short days, freezing temperatures, and doubled-down quarantine.

We discovered that we each aspire not just to survive these next few months, but to somehow rise up and meet their challenges with grace. To create good days at home, we agreed, would require a strategy. That means making sure we stay connected to small, tangible ways to take care of ourselves.

As someone with a bit of a prepper mindset, I’ve got the shopping part of my winter plans covered. There’s plenty of rice and coffee and toilet paper in the basement. I have long underwear and warm socks; there will be no excuses for not bundling up and getting outside in every kind of weather. That’s the easy part.

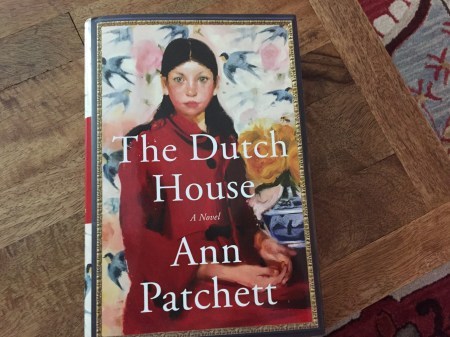

It’s the emotional demands of a long, fraught winter that will require a bit more advance planning. As always when I need to bolster myself, I turn to books. And although there will be no dinner parties, family get-togethers, houseguests, or evenings out in our future, I realize how much I’m looking forward to the opportunity to spend time this winter in the company of a few special books that feel like friends. I may or may not take a deep dive into a long novel come January. But right now, with so much loss and uncertainty in the world, I find myself reaching for books that simply offer comfort. Turns out Margaret has been doing the same.

And so we decided we’d continue the conversation we began on the phone on her popular podcast at A Way to Garden.

You can listen in here.

https://robinhoodradioondemand.com/podcast-player/18186/comfort-books-with-katrina-kenison-a-way-to-garden-with-margaret-roach-november-28-2020.mp3

For a full transcript, and to enter to win one of Margaret’s favorite books, the quirky and poignant memoir How to Catch a Mole, visit her site A Way to Garden.

As Margaret said, “It’s the week before Thanksgiving in the midst of a pandemic. No one is thinking about planting petunias.” It’s true. Instead we’re figuring out how to dial back even modest holiday plans, improvise on time-honored traditions, create more with less, and hunker down for the long haul this winter. With a little intention, we can nourish our spirits and turn our homes into spaces where we feel safe, content, and cared for.

Making a list of books that inspire and console seems like a good place to start. Together Margaret and I came up with a companionable group of writers whose books are in some way a balm for hard times, reminders that our own attitudes and everyday choices have the power to make our lives happier, more fulfilling, and more in tune with what really matters.

Making a list of books that inspire and console seems like a good place to start. Together Margaret and I came up with a companionable group of writers whose books are in some way a balm for hard times, reminders that our own attitudes and everyday choices have the power to make our lives happier, more fulfilling, and more in tune with what really matters.

My own comfort list is as follows.

COZY: The Art of Arranging Yourself in the World by Isabel Gillies

My husband read an excerpt from this treasure of a book in The Atlantic near the beginning of last March’s lockdown and was so charmed he immediately ordered a copy. (And I’ve just bought another one to give away to a lucky reader, details below.)

My husband read an excerpt from this treasure of a book in The Atlantic near the beginning of last March’s lockdown and was so charmed he immediately ordered a copy. (And I’ve just bought another one to give away to a lucky reader, details below.)

Cosy turned out to be the rare book that everyone in the family was happy to read. We even organized a dinner around the theme, complete with candlelight, comfort food, and written questions to answer and discuss.

Learning what makes each of us feel cozy turned out to be the perfect way to set a tone for the enforced intimacy that followed. How else would I have known that choosing a sweater vest to match his shirt each day makes my husband feel cozy? Or that my son Henry’s idea of coziness is seeing me pull out the KitchenAid mixer in the evening and set about making banana bread or muffins for the next day, something we now refer to as “after-dinner baking,” and which I’m much more inclined to do knowing it makes him happy.

When we talk about being cozy, most of us think of a favorite sweat shirt or a steaming cup of tea on a rainy afternoon. But Isabel Gillies suggests that coziness goes beyond mere objects.

To be truly cozy, she says, we first have to identify some truths about what makes us feel held, at ease, and at one with the world. And if we start to notice what feels cozy to us, and how we can create coziness for ourselves, then we can carry coziness into our day, bring more coziness into our lives, and know how to make ourselves cozy even in hard times.

HOME COOKING and MORE HOMECOOKING by Laurie Colwin

Ever since we started grocery shopping less often and eating every single meal at home, I tend to think about food morning, noon, and night. Many mornings I’ll read the front page of the New York Times and then turn straight to recipes to calm my nerves. My Ina Garten cookbooks have been in constant rotation since March. There’s been a lot of cheese.

Ever since we started grocery shopping less often and eating every single meal at home, I tend to think about food morning, noon, and night. Many mornings I’ll read the front page of the New York Times and then turn straight to recipes to calm my nerves. My Ina Garten cookbooks have been in constant rotation since March. There’s been a lot of cheese.

But for the feeling of having a best friend hanging out with you in the kitchen, there is no cosier, more encouraging, or more enjoyable companion than Laurie Colwin. When I was a young editor in New York in the ‘80s, Laurie was both a cherished acquaintance and hands-down my favorite writer; her stories and novels were at once intelligent, entertaining, and deeply touching, and I avidly collected and read them all. Later, as I negotiated the transition from single working woman picking up take-out on the way home from the office to a mom making dinner every night for a family of four, it was Laurie Colwin’s two beguiling collections of memoir-ish recipes that helped help me find my way. Laurie died in 1992 at the tragically young age of 48, but in the years since, Home Cooking and More Home Cooking have become true classics, inspiring a whole new generation of cooks and writers.

Laurie was never a person who went out much. She took pleasure in being home, in making do, in cooking simply and then squeezing in around a table to share a meal prepared with love. Her books are as much about eating as cooking, more about the pleasures of the kitchen than about creating perfection there, which makes her something of an anti-Martha Stewart and an ideal friend for these times. Yesterday, just before Margaret and I spoke, I paged through my time-worn paperback of More Home Cooking. There near the end was Laurie’s Thanksgiving chapter, with her recipe for Rosemary Walnuts, which I’ll be making next week. It reads as if it were written yesterday, except for the lines at the end, in which Laurie looks forward to one day traveling to her own daughter’s house for Thanksgiving and creating new traditions to carry on. Lest any of us need a reminder that life is precious, unpredictable, and can turn on a dime, there it is.

WHEN WANDERERS CEASE TO ROAM: A Traveler’s Journal of Staying Put by Vivian Swift

I’ve given Vivian Swift’s enchanting celebration of place to many friends over the last few years, especially those who, because of illness or injury, have found their lives severely curtailed. But now, of course, it’s the perfect book for everyone. We’re all staying put. Vivian Swift spent a lifetime trekking around the world; she had 23 different addresses in 20 years. And then, at last, she stopped moving, settled down in a small town, and began taking stock of her life and what it means to put down roots and call a place home.

I’ve given Vivian Swift’s enchanting celebration of place to many friends over the last few years, especially those who, because of illness or injury, have found their lives severely curtailed. But now, of course, it’s the perfect book for everyone. We’re all staying put. Vivian Swift spent a lifetime trekking around the world; she had 23 different addresses in 20 years. And then, at last, she stopped moving, settled down in a small town, and began taking stock of her life and what it means to put down roots and call a place home.

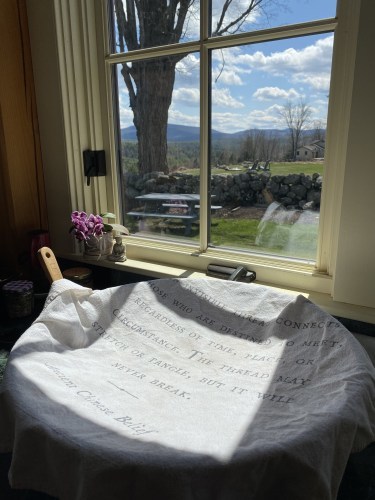

It’s impossible to convey the appeal of this hand-written, gorgeously illustrated, quirky and completely engaging book, but I can say that everyone I’ve given it to has fallen under its spell. Each page is a collage of writing, journaling, recipes, quotes from literature, odd bits of observation and natural history, and charming watercolors. The effect of it all is irresistible, a highly personal yet surprisingly universal ode to the joys of puttering, doodling, daydreaming, noticing. And every time I open it, I’m reminded that there is so much to see right here in my own home and outside my own window, even in the darkest days of winter. This might just be the coziest, most appealing book I know. It’s definitely the perfect book to curl up with on a cold December day.

KEEP MOVING: NOTES ON LOSS, CREATIVITY, AND CHANGE by Maggie Smith

After all these months, I’ve formed some new routines that have made this strange, difficult time a bit better. One of those is attending to my sleep hygiene with more discipline. I’ve learned the hard way what not to do at the end of the day – scroll through Instagram, read the latest political news, or try to achieve Genius Level on the NYT Spelling Bee. And so, to settle down, I pick up a book. What I want once I’m tucked into bed, with only about five or ten minutes worth of mental energy left, is something short, reassuring, and easily assimilated — the grown-up equivalent of a bedtime story to gently transport my anxious mind to a place of peace.

After all these months, I’ve formed some new routines that have made this strange, difficult time a bit better. One of those is attending to my sleep hygiene with more discipline. I’ve learned the hard way what not to do at the end of the day – scroll through Instagram, read the latest political news, or try to achieve Genius Level on the NYT Spelling Bee. And so, to settle down, I pick up a book. What I want once I’m tucked into bed, with only about five or ten minutes worth of mental energy left, is something short, reassuring, and easily assimilated — the grown-up equivalent of a bedtime story to gently transport my anxious mind to a place of peace.

There are two small books that have taken up permanent residence on my pandemic bedside table. The most recent is Maggie Smith’s collection of luminous short reflections, Keep Moving. When Maggie’s 19-year marriage ended, and with it the life she had known, she spiraled into a depression so deep there were days, weeks even, when she could barely get out of bed or eat. She couldn’t produce poems during this time, but she did feel the desire to write.

“If everything was going to fall apart,” she told herself, she could at least create something. And so one day she wrote a goal for herself, just a couple of sentences, and posted it on social media. The next day, another. And so began her practice of writing a short, encouraging “note to self” – some kind of affirmation or encouragement or self-directive – every day. The question she found herself asking over and over was one I know all too well: “What now?” And the answer, always, inspired the last sentence of every goal she gave herself: Keep Moving.

Keep Moving is a book of both consolation and propulsion. It’s not lofty self-help advice, more like an encouraging friend whispering into my ear at bedtime, reminding me that I can do this, that this too shall pass, that I’m resilient enough to keep moving, come what may. Maggie’s voice may just be the one you want to hear at the end of the day, too. Keep Moving is one of those sneaky little books that confronts the truth of pain and grief head on, and yet leaves one feeling hopeful and encouraged that no matter how dark things may seem, there is something good waiting for us on the other side of loss. I’ll be giving a few of these for the holidays this year.

THE BOOK OF DELIGHTS by Ross Gay

The other book I keep close at hand for those last moments before sleep is Ross Gay’s mind-expanding, gorgeously written collection of short essays about delight.

The other book I keep close at hand for those last moments before sleep is Ross Gay’s mind-expanding, gorgeously written collection of short essays about delight.

The premise is simple. Ross Gay is a poet, a passionate gardener, a Black man who does not gloss over any of the complexities or terrors of living in America at this moment. And yet on the occasion of his 42nd birthday he decided to set himself the task of writing every day about something that delighted him. The point was not to change the world, but rather to see if the very practice of noticing delight might in some way transform him. He chose to draft these short pieces quickly and by hand, and to think of the writing as a challenge to notice everything, to create room in every day for joy. Gay says it didn’t take long before he developed a kind of “delight radar.” And he also found there’s a lot to be said for the practice of flexing one’s delight muscle, especially in hard times. The more you look for and study delight, the more delight there is to study.

There is, I think, no better prescription for this moment than books that can help us steady ourselves on the shaky ground of 2020. Pandemic life is going to get harder before it gets easier. We could all use some support as we attempt to build on the mental and emotional skills we’ll need to keep going. Each of the books in my winter comfort stack are reminders of human resilience and of our innate capacities for kindness, joy, and observation. Together in spirit, we’ll spend this long winter staying home for the good of all. But at least we can make ourselves cozy as we journey in place. And what a gift it is, with so much at stake, to be carried by words into the hearts and minds of fellow travelers, seekers with whom we share a keen awareness of loss and pain, and, too, a commitment to stay open to all that is holy, ordinary, and beautiful in our lovely, imperiled world.

how to win a copy of Cozy by Isabel Gillies

I’ve purchased one copy of Cozy to give away. To enter to win, just leave a note in the comments section below. Answer any one (or all) of the “cozy” questions we asked at our family dinner table. I’ll draw a winner at random on Saturday, December 5.

When you think of your childhood, what cozy memory comes to mind?

What spot in your house is your favorite cozy place? What do you do there?

How do you create coziness when you’re all alone?

If possible, do consider purchasing these titles from your local independent bookstore. And if you prefer to order your books from Amazon, just click on each highlighted title above. (These are affiliate links.)

And do be sure to click over to Margaret and enter her give-away, too.

Stay home, my friends. Get cozy. Make soup. Cultivate delight. Keep moving and be well. We’re in this together!

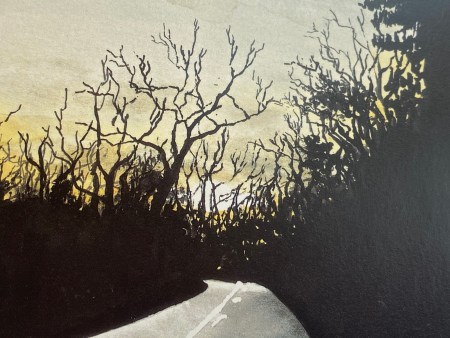

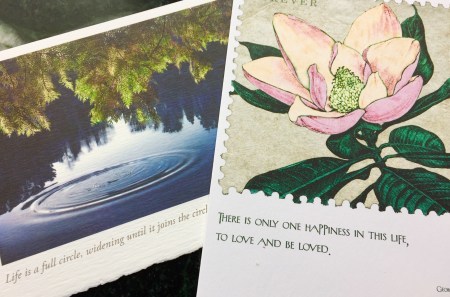

(Both watercolors above are from Vivan Swift’s When Travelers Cease to Roam.)

The post comfort, conversation, and books to get us through appeared first on Katrina Kenison.

October 31, 2020

our time

I stayed outside at dusk the other night for a long while, looking and listening, steeping in the rose-tinted mild evening air. The end of autumn is always poignant to me but it’s especially so this year. Perhaps you feel it, too.

I stayed outside at dusk the other night for a long while, looking and listening, steeping in the rose-tinted mild evening air. The end of autumn is always poignant to me but it’s especially so this year. Perhaps you feel it, too.

With so much uncertainty, loss, and anxiety in our world, we’re all a little frayed and tender. The one thing everyone seems to agree on is that we want whatever’s next to happen. We want next week to be over. We want the election behind us, we want all the votes counted, and the results to be fairly, legitimately resolved. We want, especially, to know which way we’re going.

No matter how things turn out, the road ahead will be hard. There will be more losses to come, more work to do, and so much grief and anger and failure to process. There will be chaos and confusion. I’m trying to hold onto faith there will be healing, too, and mending, and building. I try not to let myself get too hopeful. At the same time, I definitely do need to hope.

I felt quietly hopeful on that evening last week as I lingered in the yard watching the last light drain out of the sky. There were still golden leaves clinging to the maple tree that stands silent guard outside our kitchen and, for a moment, just before the sun went down, the leaves seemed to glow as if lit from within. That tree is as much a part of our days here as the view of the mountains, the hum of the freezer, the sound of the back door slamming shut. I know this old friend well – its graceful curves, the secret owl face hidden in the bark if you know how to look from just the right angle, the way the squirrels chase each other through the branches, the way the nuthatches travel headfirst down the trunk, foraging for insects.

I felt quietly hopeful on that evening last week as I lingered in the yard watching the last light drain out of the sky. There were still golden leaves clinging to the maple tree that stands silent guard outside our kitchen and, for a moment, just before the sun went down, the leaves seemed to glow as if lit from within. That tree is as much a part of our days here as the view of the mountains, the hum of the freezer, the sound of the back door slamming shut. I know this old friend well – its graceful curves, the secret owl face hidden in the bark if you know how to look from just the right angle, the way the squirrels chase each other through the branches, the way the nuthatches travel headfirst down the trunk, foraging for insects.

And, after days of raking, tarping, hauling, and mulching leaves, I also knew we weren’t quite done. Getting the yard and garden ready for winter is a long, physically demanding process. Always, the radiant maple is the last tree on this hilltop to drop its golden leaves, signaling the end of one season, the colder, darker beginning of another. Tomorrow, I guessed, or the day after, the maple, too, would finally, silently, undress. It is the last of October, after all.

As I stood there, sore and tired from a long afternoon of yard work but reluctant to call it a day and go inside and start dinner, the sky around me became suddenly alive with birds. First a few and then more and more arrived, as if summoned by some invisible bell. Swift and straight as arrows they flew, small black silhouettes in the shadows, approaching from all directions, slipping without pause into the maple’s sheltering branches until surely there were a hundred birds or more enveloped in the tree’s embrace.

The sight of all those birds winging their way home to roost filled me with awe. We have lived in this house for fourteen years and I’ve never once seen such a sight. And yet, for all I know, it happens every night. I turned at last to go indoors with my head full of questions. What kinds of birds were they? Would they all remain tucked in there together till dawn? Does this great homecoming migration happen all year long? How could I have missed it? And: what else am I not seeing?

In this year of staying home, my own roots in this place have grown deeper, my awareness of its rhythms heightened. The more I look, the more I see. The quieter I become, the more I hear. The slower I am, the more attuned I become to the eternal pulse of nature, to the slow turning of the seasons, the movements of animals, the cycles of life that sustain and shape and support us here on this mysterious, intricately balanced earth.

Lately I’ve found it almost impossible to sit still long enough to write more than a text or a grocery list. Every time I turn on my computer, I’m awash in a sea of words – entreaties for money for good causes, another batch of emails to answer, breaking headlines to process, polls and scandals and tragic Covid numbers to absorb, thoughtful articles and essays by writers I admire and long to read. And, too, a sense that there’s never enough time to give any of these things the attention they deserve.

Lately I’ve found it almost impossible to sit still long enough to write more than a text or a grocery list. Every time I turn on my computer, I’m awash in a sea of words – entreaties for money for good causes, another batch of emails to answer, breaking headlines to process, polls and scandals and tragic Covid numbers to absorb, thoughtful articles and essays by writers I admire and long to read. And, too, a sense that there’s never enough time to give any of these things the attention they deserve.

And I will confess: All of this writing, analysis, information, and projection only increases my jangled sense of overwhelm and anxiety. My fight or flight response quite often leads me away from the screen and straight out the door, where there is always physical, tangible work to be done — a garden bed to be cut back, pots to empty, another load of leaves to haul to the compost pile. And, too, where there is always beauty, silence, and a kind of holiness. At my desk, in my house, or staring at my phone, my heart is often heavy, my jaw clenched, my stomach flipping. Outdoors, though, it’s a different story. With the sky overhead and the earth beneath my feet, I become part of a larger narrative, a longer, deeper one in which my own place in things falls back into perspective. We humans are so small, so briefly here.

One way or another, we’re all white-knuckling our way toward Tuesday. I’ve probably made too many impulse donations to candidates I believe in, but I regret none of them. My husband, son, and I have written letters and held signs. In our small town, we’ll don our masks and vote in person. Beyond that, my approach during these last days has been to stay outdoors as much as possible. I can’t control the outcome of anything that matters, but I can keep the birdfeeders full. I can sweep out the shed, rake up the leaves, and pull out the petunias. I can stay grounded in the simple, necessary tasks of my own life. And I can look at the sky, at the now bare maple tree, at the snow that covers the ground this morning in a frosting of white, and trust in the forces at work in the world that are far beyond my own limited seeing and my own narrow understanding .

One way or another, we’re all white-knuckling our way toward Tuesday. I’ve probably made too many impulse donations to candidates I believe in, but I regret none of them. My husband, son, and I have written letters and held signs. In our small town, we’ll don our masks and vote in person. Beyond that, my approach during these last days has been to stay outdoors as much as possible. I can’t control the outcome of anything that matters, but I can keep the birdfeeders full. I can sweep out the shed, rake up the leaves, and pull out the petunias. I can stay grounded in the simple, necessary tasks of my own life. And I can look at the sky, at the now bare maple tree, at the snow that covers the ground this morning in a frosting of white, and trust in the forces at work in the world that are far beyond my own limited seeing and my own narrow understanding .

One day last week, I rounded the corner of the house pushing the wheelbarrow and was stopped in my tracks by the sight of fifty or sixty robins hopping about in the front yard, a gathering as uplifting to me as the determined crowd of citizens who have showed up downtown every Saturday all through the fall to stand in silent solidarity with Black Lives Matter, voting rights, and democracy. When we looked up from breakfast a few days ago to see a herd of deer just outside the window, they seemed almost like silent messengers sent to remind us that we share this time, this place, with others and that we’re all connected, for better and for worse.

I stood in the garden one day last month surrounded by Monarchs; two weeks later, I watched a lone butterfly alight on a stalk of fading verbena, certain somehow this would be the last one until next year. I’ve watched chilled bees wobbling from one late-blooming cosmos to another. I’ve born witness to every sunrise, gazed at clouds, dug in the dirt, searched for the season’s last nasturtiums, made salads from the garden’s final gleanings, and potted up geraniums to carry inside for the winter. I’ve watched the landscape change from lush green to fiery reds and golds to brown and bare. As the last leaves drifted down, I was there to catch them. This morning I stepped outside and lifted my face to the year’s first snow. And then, as always, I headed back indoors feeling a bit more centered, a bit more able to take in the truth of everything else that’s happening at this fraught moment.

I stood in the garden one day last month surrounded by Monarchs; two weeks later, I watched a lone butterfly alight on a stalk of fading verbena, certain somehow this would be the last one until next year. I’ve watched chilled bees wobbling from one late-blooming cosmos to another. I’ve born witness to every sunrise, gazed at clouds, dug in the dirt, searched for the season’s last nasturtiums, made salads from the garden’s final gleanings, and potted up geraniums to carry inside for the winter. I’ve watched the landscape change from lush green to fiery reds and golds to brown and bare. As the last leaves drifted down, I was there to catch them. This morning I stepped outside and lifted my face to the year’s first snow. And then, as always, I headed back indoors feeling a bit more centered, a bit more able to take in the truth of everything else that’s happening at this fraught moment.

For today, even with so much at stake, I must summon some trust in the enduring cycles of things. Trust there will be both another spring in our future and healing in our country. Trust that somehow justice will prevail. There is so much we don’t know. And yet there’s also a kind of knowing, or faith, that comes with opening to what’s right here, right now. Paying attention means being reminded, again and again, of how transitory this all is. Change will come, one way or another.

For today, even with so much at stake, I must summon some trust in the enduring cycles of things. Trust there will be both another spring in our future and healing in our country. Trust that somehow justice will prevail. There is so much we don’t know. And yet there’s also a kind of knowing, or faith, that comes with opening to what’s right here, right now. Paying attention means being reminded, again and again, of how transitory this all is. Change will come, one way or another.

Although our waking hours may feel suffused with politics, pain, and outrage, the opposite is also true. There is energy and kindness and fierce commitment in every corner of our country. Good people are rising up. Together, we will breathe our way through this hard season and find our way into the next, whatever it turns out to be.

In the meantime, may we continue to take good care of ourselves and of each other. May we mend the part of the world within our reach, hold each other up, welcome every fleeting moment of delight, and embrace the mystery of being here for all of it. For this, dear friends, is our time. A time not of our choosing but the one we have been given, to make of what we will.

We Did Not Ask For This Room

We did not ask for this room,

or this music;

we were invited in.

Therefore,

because the dark surrounds us,

let us turn our faces toward the light.

Let us endure hardship

to be grateful for plenty.

We have been given pain

to be astounded by joy.

We have been given life

to deny death.

We did not ask for this room,

or this music.

But because we are here,

let us dance.

~ Stephen King (for the TV adaptation of 11/22/63)

The post our time appeared first on Katrina Kenison.

June 29, 2020

big love, small moments

“It is when we are confronted with poignant reminders of mortality that we become most aware of the strangeness and wonder of our brief life on Earth.” ~ Kathleen Basford

“It is when we are confronted with poignant reminders of mortality that we become most aware of the strangeness and wonder of our brief life on Earth.” ~ Kathleen Basford

As I sit on my screened porch, looking out across the garden on this quiet, gray, end- of-June morning, it feels hard to break the stillness with words, even those I might write here. Over these last strange, sad months, as so much in our world has unraveled, writing blog posts about ordinary moments began to feel like an indulgence from a bygone era. There are so many wise, urgent voices that need to be heard right now. At the same time, there’s too much devastating news to absorb, too many losses to comprehend, and too many conversations swirling through the ether that do nothing to improve upon silence.

And so, for me anyway, this summer hasn’t seemed a time to be in the business of creating or posting, but rather a time to turn inward, to show up for my life and for my loved ones in a different way, to be saying less and listening more. It’s also been a time of deep immersion in the here and now. Perhaps it’s the stark truth of uncertainty, of loss, and of knowing we have no idea what tomorrow might bring, that inspires an even deeper devotion to the present moment. Or maybe it’s simply that staying home, staying put, and staying quiet creates more and more space in which to notice, and in the noticing we become more and more aware of just how precious and fleeting life really is.

I’ve spent a lifetime paying attention to the little things. And yet not until now has a cucumber’s slow progress from seed to salad, or a poppy’s sudden splendor, or the simple acts of taking a walk or sitting down to dinner with the family, filled my heart with such wonder, gratitude, and humility. Have the clouds always been so magnificent? Did greens from the garden always explode with such flavor on the tongue? Have there always been so many fireflies in June? Has my husband always been such a comforting presence as we turn out the lights at night, curl our bodies into each other, and slide into sleep? Would I have taken so much delight in the daily company of a bluebird at our kitchen window had I been racing to get to someplace else? Would I have wept so many tears when, after weeks of his constant presence, we found his bright, lifeless body underneath a peony bush?

Grief in one hand, joy in the other – this is our life now, isn’t it? As I struggle to comprehend the immeasurable suffering of so many at this moment, and, at the same time, as I find myself cherishing even more the moments we’re blessed to live, I’m reminded over and over again that attention is love. That love is always intertwined with loss. That there are no guarantees. And that, as long as I can soften, and open my heart to life as it is, guarantees aren’t really necessary. We’re here so briefly. How can we fail to be conscious of our treasures?

Over these last months, we haven’t strayed from home, except to spend the last two weekends at my parent’s house by the sea in Maine. Our lives have been both completely full and utterly simple, rooted in place. Steve goes into his office most mornings and has been able to shift a portion of his business online. Henry has been with us since early March, when his university closed down and he began teaching remotely from his old bedroom upstairs. At the end of May, my soul daughter Lauren left her home in Atlanta and drove 922 miles straight through to New Hampshire, where we welcomed her into our bubble with open arms. Slowly, carefully, our little group expanded when my parents, both in their mid-80s, determined they felt safe enough to visit and to enjoy meals with us. We’ve grown intimate here, sharing sunrises and sunsets, walks and talks, birthdays, the news of the day, the gardening chores, the laundry, the cooking, the dishes, happy reports at dinner, and the deep satisfactions and occasional challenges of living in such close and constant contact with each other and with nature, an unfailing source of solace, wonder, and awe.

To fully inhabit a home, a place, a life, a relationship is to discover that there are many forms of engagement, many ways to care for one another, and many ways to bring more love and compassion into a world desperately in need of tenderness.

I hope today’s short video, a gathering of small moments from the last couple of weeks, feels like a thread of love unspooling from me to you and bringing a bit of sweetness to your day. Inspired by the lyrics of JJ Heller’s lovely song “Big Love, Small Moments,” I wanted to create it simply as a reminder that sometimes just paying attention to the beauty at hand is the soul’s true calling. And I share it with you as a way of saying hello after these weeks of quiet, reweaving our connection in the knowledge that we’re all doing our best every day to be kind, to be present, and to cherish this fleeting, lovely life, right here, right now. Big thanks to Lauren for so artfully combining our photos with the music. May we all continue to walk this path together, unified by compassion and reverence for our wounded, wondrous world. This indeed could be the most creative work of all.

The post big love, small moments appeared first on Katrina Kenison.

April 18, 2020

an anniversary, a recipe, a gift

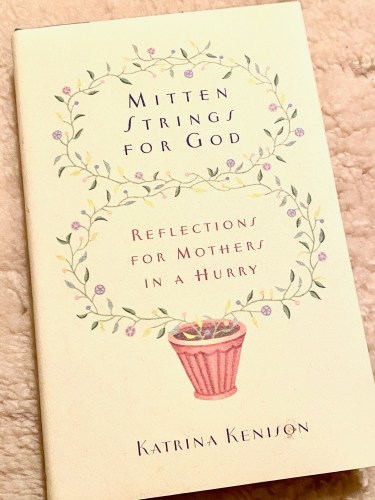

Twenty years ago this week, in a world quite different from the one we inhabit now, my first book was published.

Twenty years ago this week, in a world quite different from the one we inhabit now, my first book was published.

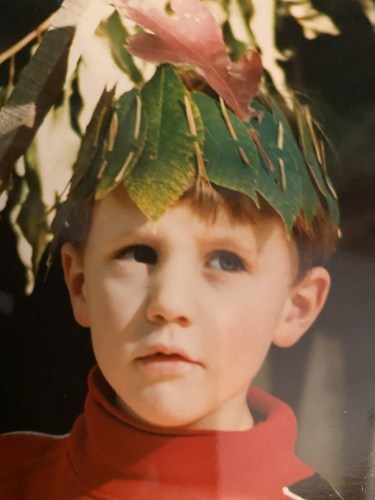

The title, Mitten Strings for God, was inspired by my son Jack, the rambunctious one in the family. Jack at five didn’t walk into a room, he slid or leapt or ran; he didn’t sit in chairs, he draped or clambered, sprawled sideways or hung upside down. He was a boy on the move. And I was his exhausted, impatient, frazzled mother.

One snowy day, as I sat crocheting mitten strings for all the boys’ surviving pairs, Jack was snuggled in close to me on the couch, finger-knitting his way through a lumpy ball of blue yarn. It was a rare oasis of stillness amidst the daily turbulence. We sat in silence for a while, doing our work. And then he looked up at me and said simply, “This is peace, isn’t it? I love this peace.”

Those innocent words filled my heart. They also gave me pause. Could it be that my son was in constant motion because I was in constant motion, too? Perhaps he needed a daily time-out as much as I did. And what if my real job as his mother wasn’t to rush him through the day, prodding and cajoling, trying to get to all the places we needed to go and to do all the things that needed doing, but rather to figure out a way to stay put and to do less?

As I finished my project, I asked Jack to show me his. He’d been sitting there, intent on his knitting, for over an hour. He held his creation aloft for me to see, all ten feet of it, and announced, “I made a mitten string for God.”

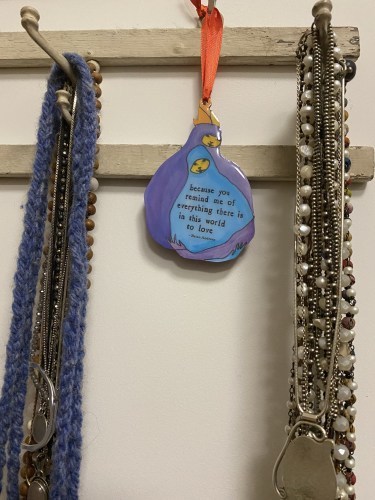

Over the last twenty years, we sold a house, bought a house, tore down a house, and built a house. Our two sons grew up, my husband and I grew old, and many possessions were jettisoned along the way. But Jack’s long blue mitten string hangs in my closet still. I see it every day.

That piece of humble handwork, looped on a hook with my necklaces, is a symbol of my own small epiphany on that ordinary, long-ago afternoon. It will forever remind me of the moment I realized that, despite all my efforts to be a good mother, I had my priorities wrong. We could continue to pack our days with activities and then hustle to get through them. Or we could do less, stay home, and enjoy our lives more. We could begin to focus on what really mattered. Each other. The small moments. The little things. The coziness of a book read aloud, the freedom of an empty afternoon, the joy of make believe, the sweet intimacy of candles at the dinner table.

That piece of humble handwork, looped on a hook with my necklaces, is a symbol of my own small epiphany on that ordinary, long-ago afternoon. It will forever remind me of the moment I realized that, despite all my efforts to be a good mother, I had my priorities wrong. We could continue to pack our days with activities and then hustle to get through them. Or we could do less, stay home, and enjoy our lives more. We could begin to focus on what really mattered. Each other. The small moments. The little things. The coziness of a book read aloud, the freedom of an empty afternoon, the joy of make believe, the sweet intimacy of candles at the dinner table.

I knew so little then about who our boys would turn out to be or what might lay ahead for any of us. But thank goodness I did realize this: their childhood would be over before I knew it. Our days were fleeting, never to be lived again. If I didn’t slow down and pay attention, my sons would grow into young men and head off into their own lives, and I’d be left looking back, wondering where the time had gone. And so it was that our family life began to change. And I began to write about it.

I wasn’t thinking about any of this last month, as every shop and restaurant in town shut down, as we began washing our hands forty times a day, sanitizing cell phones and door knobs, and figuring out how to keep three adults fed without my typical daily run to the grocery store. There was a lot to learn at first, from meal planning two weeks in advance, to hosting Zoom yoga classes, to online banking, to how to fit a mask under my eyeglasses to keep them from steaming up every time I went outside.

And there was this: the constant, uneasy awareness that we are the lucky ones.

Tucked away here, in a house where three of us can shelter in place without ever getting in each other’s way, it feels important to keep sight of the horrific truths of the pandemic’s real toll. While we were lamenting the end of our comfortable routines and the cancellation of spring travel plans, millions of Americans were losing their jobs, their savings, their loved ones, their health, their lives. While our son Henry teaches his college classes remotely from his old bedroom upstairs, hundreds of thousands of others have no choice but to jam onto crowded subways and buses, risking their health in order to get to jobs they need in order to survive. While my husband pays the rent on his empty office and spends a few hours a day there shifting some of his dormant business to online sales, countless other small businesses are ruined for good, as years of hope and investment and effort vanish into debt, uncertainty, and loss. While my safely quarantined parents get the hang of joining us for dinner on Zoom, millions of our most vulnerable citizens are isolated behind closed doors in nursing homes desperately trying to keep their residents alive. And while I’m rummaging through the basement freezer for a package of chicken thighs, food pantries from coast to coast are overwhelmed by demands they have no hope of meeting. The photo yesterday of ten thousand cars lined up in San Antonio, with people waiting for hours for emergency food supplies, haunts me and fills me with a sense of helplessness, even as we send money every week to our own local chapter of End 68 Hours of Hunger.

It is one thing to linger at the breakfast table reading the grim news, trying to comprehend the staggering reality of nearly forty thousand Americans dead, three hundred million under stay-at-home orders, two million filing for unemployment. Not to mention the desperation, fear, suffering, and gross federal incompetence that underlie those terrible numbers. It’s quite another to experience that horror and grief first hand. I don’t personally know anyone who’s died. I’ve not been required to risk my own life. I won’t lose my home. And yet, even so, I dream dark, disturbing scenarios of infection and distress. My heart feels heavy, tender, as if swollen with some chronic inflammation of sadness that is both mine and not mine to bear.

Sometimes, when I drive through our deserted town and see all the dark and empty storefronts, I find myself wiping away tears. I miss the simple pleasure of strolling into Harlow’s with my husband on the spur of the moment, sitting at a high-top table surrounded by neighbors and friends, sharing nachos and drinking wine. What I’m mourning is not the loss of going out to dinner so much as the loss of life as we all knew it such a short time ago, the loss of community, of gathering, of breaking bread together and catching up in person. The loss of innocence, too, perhaps.

And then, quickly, I brush those tears away and continue on my way, to the little parking lot behind Roy’s Market, where my grocery order will be carefully packed and waiting for me on the loading dock, with my name written in black Sharpie on the paper bag, stapled with my receipt.

Honestly, who am I to cry?

Which brings me to this. I’ve been composing blog posts in my head for weeks. But every time I sit down at my desk, I end up asking myself the same question: Do people like me really need one more self-referential essay about how to have a good day at home, when home is a warm, welcoming place with food in the pantry, toilet paper in the bathroom, and the utility bills paid in full?

And yet, here we are, living our lives. Lives which do ask that we take notice, give thanks, and find some way to give back.

As I type these words my family is in the living room together, Henry reading on the couch and Steve in the big leather chair. (Jack, in Asheville, is still working, still healthy, fingers crossed.) An unseasonably late April snow falls softly. The woodpeckers come and go from the feeder, undaunted. There is fish chowder warming on the stove, a cornbread to make, the evening news to watch once the dishes are done. And in this moment, I’m challenged to somehow hold both the anguish of so many others and, too, to be fully present here, at the end of another quiet, uneventful day. I’m trying to pay attention to what’s right in front of me. And I also feel guilty about all of it.

I remind myself that to have empathy for another’s suffering is human and necessary, an urgent part of our work right now. But that is not to deny the small moments of grace that are also ours to experience. Grief and gratitude intertwined, as is so often the case. There is much to grieve in our battered world, and yet it seems that every poignant reminder of our own mortality is also an invitation to notice how much we usually take for granted, and to become ever more aware of life’s preciousness, its impermanence, its beauty.

It’s been years since I opened Mitten Strings for God. Although I keep a copy on a high shelf in the kitchen, it seems a relic from another era, one in which my sons are frozen in time as the six and nine-year-olds they were when I was writing it. But lately, with so many days strung together at home, I’ve found myself drawn back to the simple rhythms my husband and I so deliberately established when our children were young.

It’s been years since I opened Mitten Strings for God. Although I keep a copy on a high shelf in the kitchen, it seems a relic from another era, one in which my sons are frozen in time as the six and nine-year-olds they were when I was writing it. But lately, with so many days strung together at home, I’ve found myself drawn back to the simple rhythms my husband and I so deliberately established when our children were young.

Back then, as we pared back our schedules, commitments, and our children’s activities, we discovered a kind of ease and contentment that had eluded us in the crush of going, doing, and experiencing. Less became more. In that pre-internet era we grew food, played games, read lots of books. Every other week, I made bread.

The other day, with time on my hands, I stood up on the kitchen stool, pulled down Mitten Strings for God, and looked for my old recipe.

What surprised me, as I riffled through the pages, was that I wanted to sit down and read more, as if these reflections written in the midst of mothering and learning to be more mindful, might actually have something to say to my struggling, overly emotional self right now. If I hadn’t glanced at the copyright page, I’d have missed the twenty-year anniversary. April 17, 2000. The fact that I happened to pull the book out on that very day, and that I did notice, feels like a sign of sorts.

And so, on this date that is meaningful only to me, it seems worth remembering that all our work matters, as long as it’s offered with love. Although a cure or a vaccine for the virus remains a distant hope, healing can happen in the here and now. Whether we’re alone in a room pouring our own thoughts onto a page or patiently teaching a child to read, words have the power to draw us closer. Whether we’re logging into an online conference call or phoning an old friend who lives alone or writing a letter by hand, connection erases the space between us. Whether we’re sewing masks at the kitchen table or treating patients in the ER or, as my son Jack is doing now, counseling recovering addicts who are trying to stay sober while their new routines unravel around them, we’re all part of a vast communal effort to help people get better. And whether we’re making yet another pantry dinner for the family, bringing pizza to nurses who haven’t had a decent meal in days, or donating funds to a local food pantry, feeding each other is a way of honoring the sacredness of all life.

We do what we can, from where we are, with what we have.

Baking bread is a small gesture. It’s also a gift that brings a little more warmth to our kitchen and a bit of unexpected cheer to someone else’s day. Although bread recipes abound, I’ve never found one I like more than this, the bread we lived on in simpler times and that I don’t think I’ll ever stop making, now that I’ve discovered it again.

Baking bread is a small gesture. It’s also a gift that brings a little more warmth to our kitchen and a bit of unexpected cheer to someone else’s day. Although bread recipes abound, I’ve never found one I like more than this, the bread we lived on in simpler times and that I don’t think I’ll ever stop making, now that I’ve discovered it again.

Here’s the recipe from Mitten Strings for God. There’s no kneading required, no sourdough starter necessary, no fuss whatsoever. There will be six loaves, which means you can surprise your neighbors with warm bread and still have some to tuck into the freezer. (We’ve been fortunate to have flour on our grocery store shelves, at least sporadically. I hope you can find some, or at least make a trade.)

“Wonder” Bread

Combine in a very large bowl:

4 tablespoons canola oil

4 tablespoons honey

3 tablespoons sea salt or Maldon’s salt flakes

Add:

8 cups warm water

2 tablespoons yeast

Stir and wait 5 minutes, until yeast is dissolved.

Stir in:

7 cups organic white flour

6 cups organic whole wheat flour

1 cup organic medium-coarse stoneground cornmeal (I use Bob’s Mills)

2 cups organic rolled oats

When dough is well mixed (I use a big wooden spoon), scoop half of it into another large oiled bowl, cover both bowls with clean dish towels, and let the dough rise until doubled, about 1 ½ hours. Punch the dough down, either with your hands or your big spoon, and let it rise again, about 1 ½ hours. Divide the dough into 6 well-buttered pans and allow it one final 1 ½ hour rise, covered with dish towels. Bake the loaves on a middle rack at 400 degrees for about 40 minutes, or until the bread sounds hollow when tapped, rotating the pans midway through the baking to ensure even browning. Tip the cooked loaves onto a rack to cool slightly. And then, while the bread is still warm, slip a few loaves into paper bags and deliver them to your favorite people.

And finally, to celebrate the birthday of this small book that has continued to find its own way in the world for all these years, I’m giving away one of my very last hardcover copies of Mitten Strings for God, signed and personalized.

To enter to win a signed copy of Mitten Strings for God

Just leave a comment below. What are you grateful for? Or, what have you learned? Or, what do you miss? Or, what are you grieving? In other words, share a glimpse of what’s true for you right now. (Of course, you can also just say “count me in.”)

I’ll draw a winner at random at 12 pm EST on Friday, May 1.

Want to buy your own copy? I encourage you to do that here, through my beloved local bookstore, The Toadstool, in Peterborough, NH. (This will be a paperback.) I’ll be happy to sign your book before it’s shipped, and they will be happy to mail it to you. Although their doors are closed, The Toadstool is continuing to serve customers. And shipping is FREE. Let’s support our booksellers!

The post an anniversary, a recipe, a gift appeared first on Katrina Kenison.

March 16, 2020

the gift of an ordinary day

We were supposed to fly to New Orleans on Friday to meet our son Henry for his spring break. Instead, Henry was able to get a last-minute flight home to New Hampshire. He closed up his apartment in Tuscaloosa knowing he might not return till fall, shipped a box of books, filled two suitcases, and patiently listened to all my instructions about sanitizing his seat on the plane.

We were supposed to fly to New Orleans on Friday to meet our son Henry for his spring break. Instead, Henry was able to get a last-minute flight home to New Hampshire. He closed up his apartment in Tuscaloosa knowing he might not return till fall, shipped a box of books, filled two suitcases, and patiently listened to all my instructions about sanitizing his seat on the plane.

Henry’s senior musical theatre students were supposed to be in New York city this week, auditioning the numbers they’ve worked on all year before a roomful of agents and producers. Instead, they performed their pieces for their teachers and for each other on Thursday afternoon and sent a tape to New York. (The agents promised to watch, but that was then. Surely, by now, they are simply trying to survive.)

All semester, my son and and his cast for “Legally Blonde” have been rehearsing six nights a week for their April run. The spring musical in a musical theatre department is an enormous labor of love and dedication; for the seniors, it’s the culmination of four years of hope, effort, and intense study. The designers, the directors, the choreographer, the student actors – all had spent hours and hours getting this enormous show ready for opening night. There will be no opening night.

Instead, the cast gathered together one final time on Thursday evening and ran Act Two. They took to the stage and sang their hearts out, for the love of what they do and to honor the effort that’s gone into creating a show that will never be seen. And then they wept and hugged and said good-bye, knowing it was the last time they’d be together. Their four years of study and practice and late night rehearsals wouldn’t end with ovations and curtain calls, but suddenly, with tears and farewells and hastily made travel plans.

Meanwhile, I canceled the Airbnb place in New Orleans, the flights, the jazz brunch. Instead, I stocked up on pasta, rice, canned soup, and hand soap.

Saturday was unseasonably mild here, a breath of spring in the air, although I still went back inside for my hat and gloves. “We were supposed to be on the food tour right now,” Henry reminded me as we loaded fallen branches into the wheelbarrow. “Yes,” I said. “And instead we’re in Peterborough, picking up sticks and frozen dog poop.”

Given the pace of the virus spreading through our country, there is no place I’d rather be. To lace up work boots, head outside, grab a rake and begin the spring clean up here at home feels like a gift of normalcy in a world that’s suddenly become precarious, scary, and fraught with uncertainty.

Yesterday, we made waffles for breakfast and put on the Brandenburg concertos, the Sunday morning music of our kids’ childhood. Steve went to his office, to clean and go to the dump, and Henry and I hiked up Pack Monadnock. The parking lots in town were mostly empty, but not so the one at the base of the mountain. On our walk up, we ran into several friends and neighbors. People were eager to pause and chat, happy to connect from six feet away outside in the fresh air. We are all grasping at normalcy, it seems.

We stopped in to visit my parents on our way home, standing outside on the porch to talk through an open window rather than going inside. My mom passed her binoculars out through the door, so we could watch an otter hanging out on an ice floe on the pond, lazily snacking on a fish. If I could have held onto that moment, made it last, I would have. Instead, I simply tried to soak it up – the sun on our faces, my parents safely tucked inside their little house, my son at my side, the quiet half-frozen pond spread before us, a solitary otter enjoying its catch.

Back home, I set up a Zoom account on my iPad and texted Lauren in Atlanta to do the same. She and her room mate rolled out their mats and within a few minutes we had a cozy little yoga class going. It felt intimate and communal, as if we really were all together in the same room. The whole thing was unplanned, but as I asked them to lie down and close their eyes for shavasana, I wished I had something more to offer, a few words that might help us all calm down a little and remind us that even our “insteads” might have slender silver linings, if we’re open to seeing them.

I woke up early this morning, long before first light, wondering about what’s next. Just a week ago most of us were simply watching the news and living our lives, albeit with a slow-growing sense of anxiety. Now, seven short days later, we’re creating new lives in territory we barely recognize. The shift is invisible, profound, and utterly unsettling.

For me this last week has been mostly about upended plans and hasty homecomings, shopping lists and new hygiene habits, and making an abrupt adjustment from going and doing to staying and being. Meanwhile, everyone I know has been dealing with the confusion, disappointment, and the cost of canceled plans and trips, classes and work commitments. We all have family members displaced or in flux or wondering if a sore throat is something to worry about. We have loved ones in nursing homes who are suddenly inaccessible and friends in quarantine. Our routines are upended and our worries mount as we confront new bills, shrinking bank accounts, encroaching illness, and countless what-nows and what-ifs. And yet, so far, we are the lucky ones.

A vivid, intimately detailed story in the New York Times last week about two young health care workers in China brought home the devastating reality of the coronavirus for me in a way no chart or graph or headline possibly could. Both were twenty-nine years old, both were devoted young mothers with small children at home, both took every precaution against the virus as they showed up for work to care for the ill. Both became gravely sick themselves. Only one survived.

At this moment, no one in my own close circle is sick. But it doesn’t take much of a leap of imagination to understand that I, too, may lose people. Things are going to get harder. And sadder. In the meantime, like everyone else, I do my best to prepare. Buying some extra canned goods and soap is the easy part. New habits require diligence and practice, but I can do that, too. And there are plenty of ways to be productive at home. The closets, the basement, the garden – everywhere I look, a task awaits. On a practical level, I’m as ready as I can be.

The hard part, perhaps for all of us who are quietly turning inward at home this week, is figuring out how to ready ourselves for losses we can barely bear to think about. When we have no idea what’s next, or exactly how or when our own challenges will arise, the only sane choice is to practice staying present with life as it is right now. And the only thing we can know for certain is that life as it is will continue to be transformed, perhaps dramatically and tragically, in the weeks ahead.

I’m sitting in my kitchen as I type these words, watching a familiar flicker come and go from the feeder just outside. The window is cracked open, and every now and then a solitary, unknown bird lets loose with a yearning call. Outside, the first daffodils are pushing through earth that was still frozen solid a week ago. The forsythia branches I cut on the last day of February and stuck in a vase are budding into yellow blossom, promising the arrival of spring. There’s food in the refrigerator and my family is safe. Looking around, everything appears completely the same as it’s always been. And yet, nothing is.

I’m sitting in my kitchen as I type these words, watching a familiar flicker come and go from the feeder just outside. The window is cracked open, and every now and then a solitary, unknown bird lets loose with a yearning call. Outside, the first daffodils are pushing through earth that was still frozen solid a week ago. The forsythia branches I cut on the last day of February and stuck in a vase are budding into yellow blossom, promising the arrival of spring. There’s food in the refrigerator and my family is safe. Looking around, everything appears completely the same as it’s always been. And yet, nothing is.

All over town, shops, restaurants, schools, and theatres are shuttered, empty, and still. Who knows when, or if, they’ll open again. My husband, owner of a small business, is at work today, meeting with his staff, confronting the stress of decisions that impact not only the lives of his employees, but their entire families and livelihoods, as well as ours. In Asheville, our younger son Jack is doing a double shift at the sober-living program where he works, with little choice but to show up and be useful during a time of high stress and increased vulnerability. Part of his job is to accompany clients to daily twelve-step meetings, but this week all those public gatherings have been canceled. Instead, they are holding their own meetings at the Next Step house, offering each other support even as newly established recovery routines are upended by closings and shut-downs.

There are no easy answers, no clear path through any of this, other than caution, kindness, and care for ourselves and others.

And so I remind myself: my real challenge right now is a spiritual one. In the midst of an evolving, unprecedented crisis, can I truly practice living moment to moment? Can I take on this strange new life day by day, from a place of tender awareness rather than fear? Can I let go of the ways I thought life would unfold and save my strength to swim with the tide? Can I stay focused on what’s good, right now?

I’m trying. We all are. And just as the virus that’s occupying our collective consciousness is invisible, so too is the love we put forth with every gentle word spoken, every note written, every phone call to a friend, every random kindness offered and received. I believe that in a time like this, once all possible precautions have been taken, love remains our most powerful antidote to fear and despair. We’re in this together, dear ones. Let’s stay home, even as we keep looking for ways to reach out and support each other. Let’s sanitize what we can and then seize every opportunity to notice beauty, to manifest joy, to create connection, and to keep and share the faith that, together, we will come through.

Fourteen years ago, as a cherished friend confronted the too-soon end of her life, I began writing notes for a book called The Gift of an Ordinary Day. I wanted to remind myself, as much as anyone else, just how precious an ordinary day can be. My guess is that none of us will ever again forget.

Pandemic

What if you thought of it

as the Jews consider the Sabbath—

the most sacred of times?

Cease from travel.

Cease from buying and selling.

Give up, just for now,

on trying to make the world

different than it is.

Sing. Pray. Touch only those

to whom you commit your life.

Center down.

And when your body has become still,

reach out with your heart.

Know that we are connected

in ways that are terrifying and beautiful.

(You could hardly deny it now.)

Know that our lives

are in one another’s hands.

(Surely, that has come clear.)

Do not reach out your hands.

Reach out your heart.

Reach out your words.

Reach out all the tendrils

of compassion that move, invisibly,

where we cannot touch.

Promise this world your love—

for better or for worse,

in sickness and in health,

so long as we all shall live.

~ Lynn Ungar

(As I was writing this afternoon, this poem arrived in my in-box, the daily offering from my friend Claudia Cummins’s much loved blog A First Sip. It speaks so exquisitely to the moment that I wanted to share it with you.)

The post the gift of an ordinary day appeared first on Katrina Kenison.

February 25, 2020

delight

By the time I step out of the shower, my husband is already downstairs in the kitchen. The rich, cinnamon smell of French toast wafts up to the steamy bathroom, mixing with the scent of my citrus body lotion. The day awaits. But for a moment here, after I towel off and run a brush through my hair, I stand still, quiet, noticing everything.

By the time I step out of the shower, my husband is already downstairs in the kitchen. The rich, cinnamon smell of French toast wafts up to the steamy bathroom, mixing with the scent of my citrus body lotion. The day awaits. But for a moment here, after I towel off and run a brush through my hair, I stand still, quiet, noticing everything.

At the table, my husband has laid out a placemat for me, my cloth napkin in its ring. Dawn light pours through the tall windows. I measure out coffee, cut up fruit, choose a mug from the shelf, then step out into the yard for a moment to breathe in the clean morning air and listen to the woodpeckers banging away in the maple tree. Snow still blankets the ground, but something ineffable has tilted toward spring. There’s a promise of warmth beneath the cold, a releasing of winter’s grip on the land. You can feel it.

Inside, we sit as we always do, mostly silent over breakfast, reading the news on our iPads, exchanging a few words about the day’s grim tidings. There’s nothing hopeful to be found in the headlines. Crises multiply and intersect as the once unimaginable molts into reality – an intractable virus spreading through the world, Antarctica reporting record high temperatures; our election already under siege; a profane, partisan, self-serving president who lies viciously and flagrantly while denying any truth he doesn’t want to hear. The horrors seem at once urgent and, from the vantage of our own sunny kitchen table, oddly distant. “I almost don’t know how to absorb any more,” I say, pouring a second cup of coffee. “It’s all so disturbing and also kind of unreal.”

“Yes,” my husband agrees. “I know.”

And yet, on a bright winter morning, in this house, together, we are happy.

Somehow, both of these things are true. Things are bad. Things are good. And this, it seems, is the paradox of our time. Somehow we must learn to live with it. Is it possible to hold an awareness that much of our world is under siege while, at the same time, cultivating, nurturing, and expressing delight in its riches? Can we have empathy for those who suffer and, at the same time, allow ourselves moments of simple happiness when life is sweet?

“Despair is omnipresent,” a friend wrote this week. But so is goodness. In the midst of a dark, divisive time, we must remember that joy is possible, too. Not only possible, but necessary – a kind of radical and spiritually adept response to the complexity of the human condition. And perhaps our real challenge is to find a way to address everything that’s wrong while, at the same time, refusing to bow to either hatred or hopelessness.

I suspect I’m not the only one who wonders what it means at this dark moment to be a good person, a good neighbor, a contributing member of society? What does a good life look like? How can we be happy when so many others are struggling?

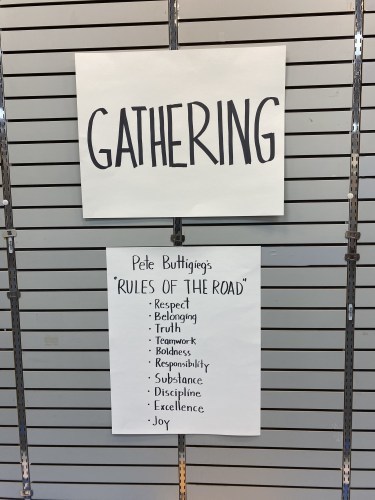

I believe there are as many ways to help as there are heads and hearts yearning for healing, truth, and justice. Still, considering what we’re up against, my own gestures seem small and insignificant: be kind, donate time and dollars to a campaign that stands for integrity and decency, knock on doors and make phone calls, write a letter by hand, make a meal for someone in need, engage in a conversation that attempts to bridge a divide rather than widen it. I feel better for doing what I can. And I know that, whatever I do, it will never feel like enough.

I believe there are as many ways to help as there are heads and hearts yearning for healing, truth, and justice. Still, considering what we’re up against, my own gestures seem small and insignificant: be kind, donate time and dollars to a campaign that stands for integrity and decency, knock on doors and make phone calls, write a letter by hand, make a meal for someone in need, engage in a conversation that attempts to bridge a divide rather than widen it. I feel better for doing what I can. And I know that, whatever I do, it will never feel like enough.

And so I must continually remind myself that although life itself can seem boundless, time is short. We’re on this earth but briefly, and it’s up to each of us, every single day, to find our own way to engage with it, both as celebrants of its beauties and as citizens who care about its future.

I’m grateful for the deep, daily pleasure I take in ordinary things. But I’m also aware of a constant, low-grade knot in my stomach, a combination of anxiety and sadness that comes of living nowadays, as so many of us do, with one other gnawing question: “Is this really the best we humans can do?”

As always when uncertain of my footing, I head this morning to my bookshelves and scan the spines. So many familiar old friends are there, patiently waiting, ready to be of use. I reach as if guided for a book I first read twenty years ago — a collection of quietly eloquent life-affirming letters by a young Jewish woman determined to maintain her faith and optimism even in the face of near certain death.

And indeed, I find in the pages of An Interrupted Life exactly what I need to hear. In one of her final letters from a Nazi detention camp in 1943, twenty-nine-year-old Etty Hillesum exclaims, “Despite everything, life is full of beauty and meaning.” These words, written in the most extreme circumstances imaginable, strike me as a kind of lamp in the darkness, an instruction to keep paying attention.

“Despite everything, life is full of beauty and meaning.”

And so it is — if, despite everything, I take time each day to see it.

I’m delighted at this very moment by the red-capped flicker at the bird feeder, gracefully extracting sunflower seeds through the mesh with its long slender beak. I’m delighted by the steady drip of melting icicles, by the warmth on the porch where I sit typing these words, by the play of light and shadow across the table. Beauty, when I pause long enough to notice, is always at hand. These days, it feels like both a responsibility and a privilege to be aware of how precious each moment really is, and to be grateful. To quote Etty Hillesum again: “Against every new outrage and fresh horror, we shall put up one more piece of love and goodness.”

Etty made a point of noticing, even in the transit camp where she spent her final days, the beauty that existed alongside incomprehensible evil. “The sky is full of birds,” she wrote. “The purple lupines stand up so regally and peacefully, two little old women have sat down for a chat, the sun is shining on my face, and right before our eyes, mass murder.” I have to pause and allow the extraordinary courage of those words to sink in. Etty Hillesum’s last letter was scribbled in haste; she tossed it from the window of the moving train that was carrying her to Auschwitz. It said only this: “We left the camp singing.”

It is odd, I know, to quote a concentration camp victim in an essay about happiness. But Etty Hillesum’s determination to see light in the darkness, and to comfort others with her delight in nature and her insistent faith in humanity’s goodness, is an inspiration to me at this moment. Her example suggests that to live well in this world is to honor its beauty even as we acknowledge its suffering. It’s to create peace where we are and to create wider and wider circles of peace as we can. And in these quiet moments of being, delight finds its way in. Delight is the love-child of attention. And attention is a potent and necessary antitote to despair.

When my younger son phones to get some big-picture counsel about his next steps, I’m delighted to realize this is where we are now. What a miracle, really, that the two of us are finally able to talk so openly, to trust each other, to listen, both hearts soft. It delights me to say the words “I love you” and to know he hears them.

When my younger son phones to get some big-picture counsel about his next steps, I’m delighted to realize this is where we are now. What a miracle, really, that the two of us are finally able to talk so openly, to trust each other, to listen, both hearts soft. It delights me to say the words “I love you” and to know he hears them.

Throughout the morning, my mom and I exchange texts about today’s Spelling Bee in the New York Times, competing against each other to find the pangram that uses all the puzzle letters and to see who can attain “Genius” level first. I’m delighted that my favorite Scrabble partner is still on her game at age 82, and that she takes her own delight in waking me up at six a.m. to let me know she’s found fourteen words before sunrise.

On a walk, I’m delighted to chat with my soul daughter in Atlanta and especially delighted that, when I tell her I’ve been actively noticing and cultivating delight today, she offers to read me a children’s book she’s found about happiness. I climb slowly up the hill toward home with her beautiful voice in my ear, telling me a story.

“An old gentleman found it in a snowflake,” she says, “in the deep cold that came from distant lands. For just a moment, he thought that he was little again.”

I tell her how much I cherish this long meandering phone visit, how happy I am being read to and catching up on a Sunday afternoon. “That’s what we do for each other,” she reminds me. “Collaborative delight.”

I tell her how much I cherish this long meandering phone visit, how happy I am being read to and catching up on a Sunday afternoon. “That’s what we do for each other,” she reminds me. “Collaborative delight.”

At the grocery store, an acquaintance greets me in the produce aisle and then steps in closer. “I want to give you a gift,” she says intently, completely surprising me. “Five minutes ago, as I was on my way over here, I saw a tree with a thousand robins in it. I had to pull over and stare at it. It was an amazing sight, like a miracle! Where did they all come from? Maybe, when you go home, they’ll still be there.” I didn’t take a detour to see if the robins had stuck around in that tree, but I didn’t really need to. For me, the delight was bearing witness to her delight.

“Cool cloud cover here,” Henry texts in a family thread as I’m making dinner, along with a photo he’s just taken from the parking lot of his Tuscaloosa apartment. “Mackerel sky,” my mom writes back, attaching a link to the Wikipedia entry. And so I’m reminded of something else about delight: it grows when we share it. With each small act of noticing and offering, we sow a few seeds of happiness. What grows, then, is our own sense of interconnectedness and belonging. What blooms and flowers in that space is love.

“Cool cloud cover here,” Henry texts in a family thread as I’m making dinner, along with a photo he’s just taken from the parking lot of his Tuscaloosa apartment. “Mackerel sky,” my mom writes back, attaching a link to the Wikipedia entry. And so I’m reminded of something else about delight: it grows when we share it. With each small act of noticing and offering, we sow a few seeds of happiness. What grows, then, is our own sense of interconnectedness and belonging. What blooms and flowers in that space is love.

There is no denying the pain of loss, sorrow, fear, injustice, wrong-doing, violence, heartbreak. To be human is to hurt. But to be human is also to have an infinite capacity for hope and innate ability to see beauty in the world as it is. And in these bleak times, perhaps it’s as important to seek out moments of joy in our days as it is for us to carry the weight of all that needs fixing.

“Despite everything, life is full of beauty and meaning.”

Given the state of our fractured, imperiled world, it seems safe to say we’re in this struggle for the long haul. If we’re going to find the strength to carry on and to fight for what matters, we must also continue to celebrate what we love. To embrace delight, to dance with abandon, to soak up beauty, to share each day’s small gifts and doings, is to take care of ourselves and each other. So, if you should see a tree full of robins or a mackerel sky, be sure to tell someone. Your delight is mine.

In the spirit of sharing delights, here are a few more.

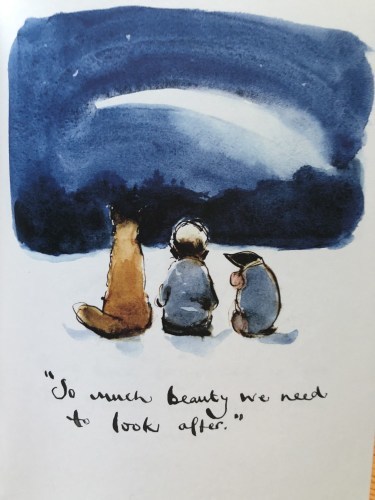

The Boy, the Mole, the Fox, and the Horse by Charley Mackesy

For Valentine’s Day, my friend Maude gave me a small book that continues to bring me both delight and deeper understanding. The Boy, the Mole, the Fox, and the Horse is a radiant, profoundly moving source of inspiration and hope for difficult times. To call it a fable or a story is to affix a label to a work that exists beyond labels. It’s really a heart offering. And Charlie Mackesy’s astonishing art says more about love and understanding than any written words could possibly express.

The Book of Delights by Ross Gay

On his 42ndbirthday poet and gardener Ross Gay decided he’d spend a year noticing and recording the small wonders and ordinary miracles we tend to overlook in our busy lives. Each day, by hand, he wrote a few paragraphs about whatever delighted him in the moment – a friendly wave from a stranger, pulling ripe carrots from the earth, a hummingbird at rest. The result is this small, intimate reminder that delight is where we find it, which is to say, everywhere. If you’d like a nudge toward delight, The Book of Delights will open your eyes and awaken your senses.

The Big Little Thing by Beatrice Alemagna

Lauren says she ordered this book after seeing an illustration on Instagram, without even knowing it was about happiness. And so, what a delight it was for her to receive Beatrice Alemagna’s poignantly evocative, slightly mysterious celebration of life’s small, fleeting wonders. And what a delight it is for me to pass the word along here. The Big Little Thing is ostensibly for children, but don’t be fooled. It’s for all of us.

This American Life: The Show of Delights