J. Bradford DeLong's Blog, page 2182

October 8, 2010

links for 2010-10-08

COGNITIVE SLAVES - Global Guerrillas

Orwell Watch: "Structural Unemployment" As Excuse to Do Nothing « naked capitalism

Balkinization

Obama era justice - Glenn Greenwald - Salon.com

Matthew Yglesias » Governing Better Would Have Helped Democrats

Young Frankenstein (1974) - Memorable quotes

Gillian Tett: Solving deleveraging puzzle will calm investors

Alan Rappeport: Summers calls for infrastructure spending

links for 2010-10-08

COGNITIVE SLAVES - Global Guerrillas

Orwell Watch: "Structural Unemployment" As Excuse to Do Nothing « naked capitalism

Balkinization

Obama era justice - Glenn Greenwald - Salon.com

Matthew Yglesias » Governing Better Would Have Helped Democrats

Young Frankenstein (1974) - Memorable quotes

Gillian Tett: Solving deleveraging puzzle will calm investors

Alan Rappeport: Summers calls for infrastructure spending

Department of "Huh?!" (Why Oh Why Can't We Have a Better Press Corps?)

At the 2005 Jackson Hole conference that turned into Raghu Rajan (supported by Alan Blinder and Armenio Fraga) vs. the world, Raghu made two big points:

The past decades of financial deregulation had created a world much more vulnerable to financial crises than we recognized.

The big thing that needed to be done to guard against disaster was to insure that financiers had their personal fortunes on the line--that every decision maker have not just "skin in the game" but rather a spleen, a limb, a lung, and a heart in the game as well.

Raghu was, it is very clear, very right about (1). I think it was also clear that he was very wrong about (2): Charles Prince and James Cayne and Richard Fuld had plenty of vital organs in the game. And it did not help.

Criticizing Raghu, Larry Summers made some points that he had been making for in some cases decades:

That the dangers caused by increased financial sophistication, while real, were more than offset by the advantages in the mobilization of capital for investment.

That the first and most important line of defense against financial crises was and remained active economic management by central banks.

That since 1979 the world's central banks had demonstrated that they were significantly more powerful and competent than previous generations had thought, and that there was every reason that they could handle whatever problems markets would throw at them.

That Raghu overestimated the extent to which "vital organs in the game" were a solution--that both the principal case study (LTCM) and the principal analytical paper (Shleifer-Vishny "Limits to Arbitrage") that Raghu were relying on were concerned with situations in which the relevant players did have "vital organs in the game."

That Raghu underestimated the extent to which additional Brandeisian transparency--conducting financial market transactions in standardized blocks on open exchanges--added to the information flow in a way that would make big crises less likely.

Now I know from direct personal knowledge that Larry had been making point (5) regularly since at least 1988, that he had been making point (4) ever since Andrei Shleifer and Robert Vishny circulated the first draft of their "Limits to Arbitrage" paper, had been making point (3) ever since the largely-successful resolution of the 1997-1998 East Asian financial crisis and the 2000 dot=com crash, and had been making points (1) and (2) on a regular basis since before I started graduate school. Until the fall of 2008, I think, Larry believed all 5 of these points--I know I certainly did. And even now the only one that is clearly wrong is (3). (1) is probably wrong (although it is close), and (2), (4), and (5) look stronger and righter than ever.

So I am surprised to see the Economist's Democracy in America writing:

: Mr Rajan is a rather more free-market sort of economist than is Mr Summers.... Mr Summers' intemperate reaction certainly seems benighted.... Once we see Mr Summers for what he is--doyen of the neo-Keynesian technocratic aristocracy--it seems rather more likely that his reaction reflected the wounded pride of a social engineer who personally helped design and vet these institutions; he was insulted by Mr Rajan's impertinent suggestion that they don't check out. Mr Ferguson is right to shine a light on the corrupting confluence of elite academic economics, the financial industry, and national politics. But the problem just isn't Larry Summers's ideological aversion to government intervention. The problem is that the Keynesian ideology of expert intervention makes a fattened aristocracy of economic experts inevitable.

When people make points that they have been making for decades in the typical manner of intellectual conference engagement they have engaged in for their entire life, you really don't need to go looking for bizarre unsupported psychological explanations.

Why oh why can't we have a better press corps?

Felix Salmon's Hair Is on Fire

Felix Salmon:

Time’s running out for job growt: There’s absolutely nothing to get excited about in the September payrolls report. America has substantially fewer jobs than it did a month ago, in what is meant to be a growing economy. Even the uptick in private-sector employment (+64,000) is pretty pathetic: it’s not enough even to keep up with population growth, let alone to make a dent in the unemployment rate, which stays at 9.6%.

Meanwhile, as the school year begins, we have this:

Employment in local government decreased by 76,000 in September with job losses in both education and noneducation.

As states and municipalities around the nation start running out of money, they’re going to fire people; this is only the beginning. And if October is any indication, the job losses in the local government sector are going to be at least as big as the job gains in the private sector. No wonder the number of discouraged workers is up a whopping 71 percent even from the grim days of September 2009:

Among the marginally attached, there were 1.2 million discouraged workers in September, an increase of 503,000 from a year earlier. Discouraged workers are persons not currently looking for work because they believe no jobs are available for them.

The U.S. does not have the luxury of waiting indefinitely for job growth to resume. Already we’re at the absolute limit: any longer, and most of the unemployed will be long-term unemployed and, to a first approximation, unemployable. This country simply can’t afford an unemployable underclass of the long-term unemployed — not morally, not economically, and not fiscally, either.

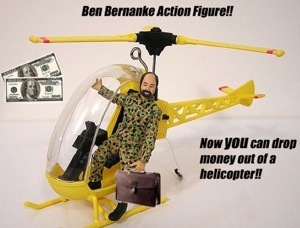

One of the puzzles of the Obama administration that I have absolutely no read on is the reappointment of Ben Bernanke. When Obama reappointed Ben Bernanke I was sure--and I had reason to be sure--that the Ben Bernanke they were reappointing was the academic I knew well, "Helicopter Ben," the intellectual advocate of much more aggressive policy responses to the collapse of the real-estate bubble in Japan in the 1990s.

Obama would, after all, have to be a complete idiot to appoint somebody who did not view the world the way Ben-Bernanke-the-academic had viewed it in the late 1990s, and who had not assured him that he did still view the world the way he had viewed it in the 1990s.

So huh?! What happened?

Even if we do get quantitative easing the day after the election, it will be at 1/4 the scale we need and a full year late.

What Does Cutting-Edge Macroeconomics Tell Us About Economic Policy for the Recovery?

Let us start with one of the first economists, Jean-Baptiste Say.

Say wanted to be a technocrat, and was well on the way--special assistant to Girondist Party Finance Minister Etienne Claviere in the early days of the first French Republic. His patron was fired, purged, arrested, imprisoned, probably tortured, sentenced to the guillotine, which he cheated by committing suicide the day before his scheduled execution.

Say somehow managed to escape the wreck of the Gironde--not just his life but hid liberty and property as well. Thereafter it was clear to him that civil service life was too risky. Being a public intellectual—that was the ticket. So Say turned to writing treatises on political economy instead.

Say, in the early and middle stages of his career, was certain that the kind of "general glut" we are now undergoing--a generalized deficiency or demand for pretty much every kind of good and service and labor, generalized high unemployment and excess capacity across the board--was inconceivable. After all, Say wrote, people make only if they planned to use themselves or to sell. People sell only if they plan to buy. Supply thus creates not exactly its own but an equal amount of planned demand. There could be no gap between the aggregate value of what people made and what they planned to buy.

Now this did not, Say stressed, mean that unemployment could not be elevated. Suppliers could guess wrong about where the demand would be. I have a standard example I use for my Berkeley classes. Employers hire and pay a lot of baristas to make half-caf double lattes made half skinny and half with half-and-half. But what consumers want are yoga lessons. They seek inner peace rather than the adrenaline rush of caffeination.

In such a situation there will be deficient demand for double latter and excess demand for yoga lessons. Baristas will be fired and collect unemployment insurance. Prices of yoga lessons and wages in the fitness sector will boom. The market will deal with it. There is a lot of money to be made by figuring out how to retrain baristas as yoga instructors. There are big profits from redeploying labor from the slack-demand food service to the high-demand fitness industry.

And in such a situation having the government intervene will only muck things up. If the government enacts a stimulus program and taxes and borrows to spend money on public purchase and provision of red-eye lattes-- well, then:

We make a lot of coffee that nobody likes to drink.

2, We retard the process of retraining baristas so that they can demonstrate how to perform the downward-facing dog.

We run the risk of inducing a general collapse of confidence in the market economy as people begin to wonder what politician is ever going to raise taxes to pay off rising government debt and productivity falls as people seek to guard themselves against future disruptions of the monetary economy that enables our highly-productive advanced societal division of labor.

That is 1803-vintage argument of Jean-Baptiste Say.

That is is what I take to be the guts of Niall Ferguson's read on today's economic problems. They are, he thinks, in essence structural and not cyclical. They are not to be alleviated but rather deepened and complicated by government attempts to solve them. Public spending putting people or artificially inducing private employers to put people to work will backfire.

I, by contrast, take my stand with John Stuart Mill's 1829 critique of Jean-Baptiste Say (1803).

Mill pointed out that people in the aggregate can and do spend less than they earn on currently-produced goods and services. They do so whenever they are unhappy with and seek to build up their net holdings of financial assets. Then you can have a general glut--an excess supply of pretty much every kind of currently-produced good and service and currently-employed labor.

It happens if and whenever you also have an excess demand for financial assets.

Historically, we have seen general gluts caused by three kinds of excess demands for financial assets. We have seen monetarist depressions caused by a shortage relative to demand of liquid cash money. We have seen Keynesian depressions caused by a shortage relative to demand of bonds--of savings vehicles to carry wealth through time so that you can spend it in the future. And we have our current situation, which looks to be a shortage not of money or of bonds so much as a shortage relative to demand of safe AAA high-quality assets--a financial excess demand for safety, for placed you can park your wealth and be confident it will not melt away while your back is turned.

We know how to cure monetarist downturns through standard open-market operations: have the central bank buy short-term government bonds for cash, thus increasing the stock of liquid cash money. That strategic intervention in financial markets eliminates the excess demand for money and as a consequence eliminates the deficiency in demand for currently-produced goods and services and currently-employed labor as well.

We know how to cure Keynesian downturns: induce households to save less and so demand fewer bonds or induce businesses or the government to issue more bonds. Those strategic interventions in financial markets eliminate the excess demand for money and as a consequence eliminate the deficiency in demand for currently-produced goods and services and currently-employed labor as well.

Now neither if those is likely to work terribly well if the financial excess demand is not for money or for bonds but for safety. Open-market operations that swap one government liability for another, private issues of risky bonds, issue of risky bonds by governments with shaky credit, or reductions in household saving that do not reduce desired holdings of safe assets leave the excess demand for safety unmet and the deficient demand for currently-produced goods and services and currently-employed labor unrelieved.

In a Minskyite downturn like the current one, the only cure is what Economist editor Walter Bagehot set out in 1868.

The government must lend freely.

It must meet the demand for safe assets by--as long and as much as it can--expanding the supply of financial assets that the market perceives as safe. Quantitative easing policies by which the central bank adds to the stock of its own safe liabilities that the private sector van hold by buying up risky assets. Small increases in the inflation target to diminish demand for safe assets by levying a small inflation tax on them. Treasury and central bank guarantees of risky private assets to transform them into safe ones. Public recapitalizations of banks with impaired capital to make their liabilities safe assets. Pulling infrastructure spending forward into the present and pushing taxes back into the future, and so increasing the supply of safe assets by having the government issue more of it's own safe debt. All of these have a place.

All of these have a place, that is, until the swelling of the liability side of the government's balance sheet cracks its status as a safe debtor whose promises-to-pay are credible. Then you find that you have not increased but decreased the supply of safe assets to the market, and made the problem worse and not better.

That can happen. Think Austria in 1931. Think Greece today. Think Argentina about once a decade since 1890.

That is what Niall Ferguson fears from any further expansions of the liability side of government balance sheets. And he sees no upside--for he sees our problem as not a general glut but as a structural imbalance, and government policies to boost demand as likely to cause inflation and retard needed adjustment.

I, by contrast, think that the right question to ask is the question that Thomas Robert Malthus asked Jean-Baptiste Say in 1819:

[I]nstead of this, we hear of glutted markets, falling prices, and cotton goods selling at Kamschatka lower than the costs of production. It may be said, perhaps, that the cotton trade happens to be glutted; and it is a tenet of the new doctrine on profits and demand, that if one trade be overstocked with capital, it is a certain sign that some other trade is understocked. But where, I would ask, is there any considerable trade that is confessedly under-stocked, and where high profits have been long pleading in vain for additional capital? The... [crisis] has now been... [ongoing] above four years; and though the removal of capital generally occasions some partial loss, yet it is seldom long in taking place, if it be tempted to remove by great demand and high profits; but if it be only discouraged from proceeding in its accustomed course by falling profits, while the profits in all other trades, owing to general low prices, are falling at the same time, though not perhaps precisely in the same degree, it is highly probable that its motions will be slow and hesitating...

And, in the end, Say bowed. The case of the 1824-5 financial crisis in Britain and the 1825-6 depression convinced him that there could be a general glut. By the time Say wrote his last book, his 1829 Cours Complet d'Economie Politique, he no longer believed in Say's Law that supply creates its own demand.

Until we see actual, real signs that expansions of government balance sheets are impairing investor confidence in government promises-to-pay, it seems to me that it would be extremely foolish not to continue to attempt to boost production and employment by expanding government balance sheets. I want to see the money that stimulative policies are impairing confidence--and not just listen to arguments that stimulative policies ought to be impairing confidence.

September Employment Report: -95,000

Payroll Numbers Not Looking So Hot...

In my inbox: "Private nonfarm payroll employment decreased by 39,000 from August to September on a seasonally adjusted basis, according to the ADP National Employment Report™. This is weaker than consensus expectations of a 20,000 increase..."

Three Very Smart Economists Being Very Gloomy About America's Foolish Choices

The CBPP has the transcript of the very nice "Economists Panel: Budget Policy, Short-Term Recovery and Long-Term Growth" at the America's Fiscal Choices symposium. Jackie Calmes, Martin Feldstein, Jan Hatzius, and Paul Krugman.

The only thing wrong with the transcript is that it keeps saying "Marty Feldman" instead of "Marty Feldstein":

"Hump? What hump?" "Never mind..."

Panel 2: Economists Panel: Budget Policy, Short-Term Recovery and Long-Term Growth

9:30 am – 10:30 am

CALMES: I thought I'd... ask each of our panelists what they see as the trajectory for unemployment through the end of 2011, and when we might start to see something approximating full employment, and what do we need to do to get there. So, with that small little question, I'm going to start with Paul.

KRUGMAN: OK. So on the first half of that question, I only know what Jan tells me.... [W]e're looking for rising unemployment over at least the next few months.... I would have guessed that we probably see unemployment continuing to rise, right up to the end [of 2011].... And as for when we return to something that looks like full employment, I think the maximum likelihood estimate is, basically, never.... [T]here's nothing visible on the horizon that will cause that to happen... no policy... aiming at returning to full employment... no technology that will drive a large amount of business investment. Historically, [in] the aftermath [of large] financial crises countries recover by having a huge exchange rate depreciation, which then leads to an export boom, but since it's basically the whole advanced world that's caught up in this, and there aren't any other planets to export to, that's not going to happen....

[T]he last time we had a global financial crisis, the recovery to full employment was accomplished by a coordinated, large fiscal expansion, known as World War II.... [W]e ought to be doing everything you can. We ought to be having quantitative easing, we ought to be having another round of stimulus.... [Y]ou'd have to have... stimulus big enough to bring capacity utilization back up to a high enough level that business investment really starts going again....

CALMES: Marty?

FELDSTEIN: I don't think Paul and I disagree all that much about the outlook. Certainly about the short term... it's pretty bleak. We have a GDP gap now which is roughly a trillion dollars, that's why we have almost 10 percent unemployment, and the GDP gap was almost as large at the beginning of 2009, and the fiscal stimulus package wasn't close to big enough to fill that hole.... [Y]ou had a whole which was, roughly, $800 billion dollars and they tried to fill it with a $300 billion, $400 billion annual fiscal injection.... [WE]e never got lift off, we never got into a recovery. And various temporary measures that we had, the cash for clunkers, the first-time homebuyers, they're finished.... The rest of the world is not going to help. The dollar relative to the rest of the world is not going to help....

KRUGMAN: [R]egardless of whether the Democrats somehow cling to the House, we're almost certainly heading for political paralysis.... I agree with Jan that there are two main scenarios, one of which is pretty bad and one of which is very bad. But there's probably a third one, which is absolutely catastrophic....

FELDSTEIN: So what can be done? So one thing that can be done is to work on fixing the situation for owner-occupied housing, fixing the mortgage situation. None of these are guaranteed to fill a trillion dollar hole, but they move you in the right direction. If house prices are beginning to go up, consumers are going to have more confidence. They're going to spend more.... Another thing that can be done is to deal with the problem that was just mentioned and that is the commercial real estate.... You don't hear so much about it, but, again, commercial real estate prices are off from the peak by about 40 percent. A lot of that is financed on five-year balloon loans that will start to come due 2011, 2012.... One could go in and work on the capital effects of fixing the impaired loans, impaired commercial real estate loans on the books of these thousands of small banks that we have around the country....

HATZIUS: I think [the] Federal Reserve is definitely an institution to talk about. They are going to do more... it's very likely to come at the next FOMC meeting, the day after the mid-term election.... I think it'll have some effect, but... the numbers that are required to really move the needle a lot are very, very large. And I think there's going to be a natural bias towards caution on more monetary policy makers in this sort of environment. I think that's usually what happens when you're in a liquidity trap, you're at the zero bond for short- term interest rates. You send the staffers away and ask them, you know, try to figure out what's the optimal policy here, and they go away, and they model things, and they come back with some, you know, enormously large number for the amount that needs to be purchased, and the policy makers say, "Oh, you know, are you really sure that you've taken account properly of all the tail risks that are associated with this? I mean, are your models going to be able to pick up the tail risk that, you know, maybe people are going to lose confidence, the financial markets in some diffuse sense are going to lose confidence." And so, policy makers say, you know, what you are saying makes some sense, let's take a small step in that direction.

And that's why, I think, in this type of situation, stimulus tends to be, basically, underprovided, relative to what's necessary. And I suspect that that's what we're going to find again....

KRUGMAN: And then there's the trap, the same thing, I think in a milder form, that happened with fiscal stimulus. You do something which is in the right direction, but inadequate. And then people say, "Well, that didn't work."

CALMES: Right.

KRUGMAN: And so instead of increasing the dosage until you get it right, you just -- you give up on the thing altogether... all of this is very familiar, if you... study Japan in the '90s....

FELDSTEIN: Let see if we can find something that might happen that might move us out of this. We saw the Euro fall from 160 to about 120, very quickly. What happens if the U.S. experiences a comparable fall on a trade weighted basis, a 25 percent fall in the value of the dollar?

KRUGMAN: Yes.

FELDSTEIN: That would certainly give a jolt.... [T]he world may, having looked at the problems in the U.S. and elsewhere may say, gosh... the fiscal deficits are enormous.... So if the world looks at all of that, and says, these guys are in trouble, "Why are we holding so many dollars? Why are we continuing to invest in dollar securities?" one of the effects could be a very substantial fall in the dollar. I'm not predicting it, I'm not wishing for it, I'm just saying that if that happened, that would be one of the ways out of this.

KRUGMAN: The problem is that, that leaving aside the renminbi issue, which is something I, obviously, write about, the other currencies against which the dollar would have to fall, are the euro and the yen, and we really are talking about a race between the halt, the lame and the blind here, right? So it is a little hard to tell that story....

HATZIUS: [I]f it happens quickly, then it probably would coincide with instability in... financial markets, so you would probably lose... on [the impact of financial turmoil on] economic activity what you'd gain on the currency side. If it happens more gradually, then, yes, I think it would be helpful, and it wouldn't be as helpful as it was in other countries that went through... large credit boom/busts that were ultimately followed by big currency depreciation.... [T]he U.S. only exports 10 percent of its GDP, so it's not Korea, or Sweden in the 1990s....

FELDSTEIN: And it's not just exports, it's net exports, so if exports go up a bit, and imports come down a bit because foreign goods become more expensive, so American's spend their money buying services here in the United States, that moves the trade balance by 2 percent of GDP. That's a big deal, because as you said, that's what fiscal policy -- that's what we may be losing in the fiscal policy. That's what we need to start bringing down the unemployment rate...

J. Bradford DeLong's Blog

- J. Bradford DeLong's profile

- 90 followers