J. Bradford DeLong's Blog, page 2178

October 12, 2010

Duncan Black: Another Obama Unforced Error in Bank Supervision and Regulation

Duncan Black:

Eschaton: HAMP Hell: This program did not require President Snowe to sign off.

He is referring to this, from David Dayen:

Portrait of HAMP Failure: How HAMP Connects to Foreclosure Fraud: Now that the foreclosure fraud scandal has deepened, I wanted to show how it connected to the problems with HAMP, using some reader stories as an illustration.... Tina Kimmel is an epidemiologist in California who saw her salary cut by Arnold Schwarzenegger to balance the budget, and this reduction in income put her in trouble with her mortgage. She tried to get into the HAMP program in June 2009, when it began, through her lender, Citi Mortgage. I’ll reprint the follies from there from her email:

Meanwhile I heard about the HAMP program.... I asked Citi to consider me for it. They asked me for dozens of documents... put me on the trial program for October – December 2009. My payments were only $1350, which was a great relief. In January, they told me me to keep paying that lower amount while they finished processing my paperwork, which I did. Then suddenly in April, they said I was in default, and that I owed them $13,000. They said that I was no longer in HAMP, so I owed the difference between what they had asked me for and I had paid ($1350), and what they were saying I actually owed them ($2800), for those 7 months, plus interest and late fees.

Citi’s explanations for why I didn’t qualify for HAMP were first, that I hadn’t submitted the right documents (but they couldn’t find any that were missing), then, they claimed that I had turned THEM down (but had no evidence of that), then, they said my credit was bad (but my credit was perfect when I applied, plus there is no credit requirement for HAMP). So in other words, I totally qualify for the program.

In May, I received an odd statement from Citi, where buried among the $13k “past due amount” and various fees, was an indication that my mortgage amount was now $2100, NOT $2800 as it had been. I found one lone person at Citi who said that inexplicably, my mortgage had been permanently modified. The only thing I can figure is that NACA got to someone there, which was great. But it didn’t stop the foreclosure train.

BTW I made, and continued to make, these mortgage payments, despite Citi saying they would have no place to put my money if I sent it in, since I was in the foreclosure process. (Huh??) But they did cash the checks anyway.

I contacted my congressperson, who put me in contact with the federal HAMP office. They told me to request Citi to give me a traditional modification (in-house) while they figured out what was going on. Citi spent all of July and August supposedly working on this new modification, which they said would “catch me up”, as well as lower my payment to around the $1350 HAMP payment.

But instead of hearing back from Citi, I was notified that on September 2, Citi had sold my account to a subprime lender, Carrington Mortgage Services (which seems to be associated with something called Quality Loan Service Corp).

I called Carrington, who told me that they had received no paperwork with my mortgage, that they were only told that I had over $16k “past due” at that point and that I was in foreclosure. I told them I had never missed a payment and had no plans to leave my house.

They then asked ME for copies of my HAMP agreement, all my qualifying docs, CitiMortgage statements, and bank statements showing all my mortgage payments, which I supplied. I asked to be considered for any in-house modification and/or forbearance and/or deferral of the “past due amount”, and they agreed to look into it. I got Carrington to accept September’s payment from me.

BUT on Sept 21, someone from the County taped an auction notice to my door: Carrington/ Quality Loan had set an auction date for my house, October 12.

That’s today. Kimmel eventually borrowed the $13,000 from friends needed to stave off the subprime lender, and saved her home. Now, let’s count the violations in this all-too-typical account:

1) Trial modifications are supposed to be 90 days only, according to HAMP policy. This stretched more than twice that long.

2) Per HAMP, the lenders are not supposed to include late fees and interest onto the amount owed if the borrower doesn’t qualify for a permanent modification. This is part of an epidemic of extra fees tacked onto the mortgage that don’t follow the specific instructions of the note. Too many homeowners accept what the banks tell them is the total amount owed to stop a foreclosure, and the terms of the note would provide that information very clearly.

3) The bank falsely accused the borrower of having bad credit when the credit would only have been damaged by the trial modification program, which is seen as a partial default on credit reports.

4) Citi improperly informed the borrower that she was denied a permanent modification when she actually succesfully received one. This is basically document fraud, designed to extract a higher payment out of the borrower.

5) Per California law, Citi must make a reasonable effort to modify the loan to prevent a foreclosure, and that does not include selling the loan to a subprime lender. In addition, Citi sold the loan without giving the new lender the paperwork, which is at the hub of the foreclosure fraud scandal.

6) Instead of getting back in touch with the borrower to notify her of the outcome of the effort to modify the mortgage, Quality Loan Service/Carrington just had the county tape a foreclosure notice to the door. I believe this also violates California law under the Foreclosure Prevention Act.

All of these casual violations of accepted standards, state and federal law, and the terms of the HAMP program, mirror exactly the violations of the the legal process governing foreclosures. The servicers would rather foreclose at this point, after a period of extending the borrower and squeezing out some more payments, because they extract fees on a successful foreclosure and have every incentive not to help modify the loan. Add to this that no federal regulator has oversight specifically over the servicers (though they do over the parent companies) and what you have is a Wild West Show, where the servicers can put borrowers through hell, trap them using HAMP, and foreclose with impunity.

In both cases, the lender could ask for their note and determine what they actually owe, and whether they would quality for a short sale, have more equity in the home than they think, etc. Homeowners are being taken advantage of by being in the dark, and allowing the servicer to have all the balance of power in the transaction. This is true in foreclosure fraud and it’s true in HAMP.

This is why we need to stop the evictions for now.

For years, mortgage loan servicing companies have engaged in shoddy business practices, ranging from misapplied payments to evicting homeowners who have never missed a payment. Now employees of these companies have admitted to falsifying thousands upon thousands of affidavits used to toss families out of their homes.

The fraudulent documents indicate a problem well beyond the “technical glitches” that the industry describes. If servicers had accurate records, there would be no need to invent paperwork. The entire system is rife with unfairness, and the mistakes and omissions have serious consequences in terms of unnecessary or even mistaken foreclosures.

Document fraud. False statements. Misplaced notes. Value to the servicer over the borrower. This distinguishes both HAMP and foreclosure fraud.

October 11, 2010

Liveblogging World War II: October 12, 1940

Can I PLEASE Go Back to My Home Timeline Now?

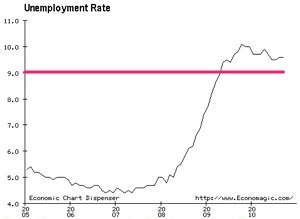

The unemployment has been above nine percent for eighteen months now.

So far there is no sign that the bulk of our excess unemployment is in any sense "structural"--no sign that the so-called "natural" rate of unemployment around which the economy should oscillate has risen from its normal 5%. If it has risen at all so far, it is very unlikely that it has risen above 6%: we still have a huge amount of "cyclical" unemployment that would melt away without inflation if only spending were higher.

But if unemployment remains above 8%, more and more of cyclical unemployment will become structural unemployment, and the natural rate of unemployment will rise.

Ezra Klein:

An ugly word for an ugly economy: You may not know the term "hysteresis." It's the "lagging of an effect behind its cause," and it's an ugly word that sounds like a foot fungus. It's also an ugly thing to have happen to your economy. And it may be what's happening to ours. We understand that our economy is growing too slowly and that our labor market is taking too long to recover.... What gets less attention is the way that slow job growth begets slow job growth.... hysteresis.

Adam Posen... doesn't think we're taking the threat of an extended period of crummy growth nearly seriously enough. When people worry about what comes next for the economy, he said in a speech to the Bank of England, they worry about a double-dip recession or a temporary period of deflation. Those, he explained, are not close to how bad things can get. "The risks that I believe we face now are the far more serious ones of sustained low growth turning into a self-fulfilling prophecy," Posen said, "and/or inducing a political reaction that could undermine our long-run stability and prosperity."

To see what he means, consider a Michigan construction worker laid off in early 2008. He didn't lose his job because he was bad at it but because his firm lost access to credit. He hasn't been able to find another job, because no one is hiring in his area, and he can't sell his house, because it's now worth less than what he owes on his mortgage.

Right now, he's an example of what economists call "cyclical unemployment." He's unemployed because of the business cycle. But if his stretch of joblessness lasts for too long, that might change. His skills might deteriorate, and so too might his confidence. He might join an altogether more troubled group: the "structurally unemployed" -- the out-of-work who can't get jobs because they're not suited for the jobs that employers are offering. The long-term unemployed, Posen warns, can become "de facto unemployable over time."

Then there's the political consequences of extended economic distress. Troubled countries do not always make wise decisions. Financial pain empowers demagogues and opportunists. Trade wars are begun, and borders closed. And we're beginning to see signs of this in our own polity.

It's not just that this year's crop of challengers for Congress -- notably Christine O'Donnell, Sharron Angle and Rand Paul -- have more extreme views than you'd normally find in the two major parties. It's that the voters are drifting as well. In 1999, only 30 percent of the country thought free trade had hurt America. Now it's 53 percent -- and among both tea partiers and union members, it's above 60 percent.

You can tell a similar story on immigration....

Remember that we're only three years into this economic crisis. Goldman Sachs Group chief economist Jan Haltzius is projecting that we'll see growth in the range of 1.5 to 2 percent next year and that unemployment will rise above 10 percent....

But even if we recognize that slow growth is an overriding problem that requires an aggressive response, what's there to do about it?... Congress seems to have given up on fiscal policy, as the insufficient stimulus spending it authorized in 2009 hasn't done the trick. And though the Federal Reserve seems likely to mount another round of quantitative easing after the election, it's coming late, and it's not likely to be enough...

Economics of Contempt: Steve Rattner Does Not Like Sheila Bair

Economics of Contempt writes:

Economics of Contempt: Steve Rattner on Sheila Bair: As I noted in my review of Overhaul, Steve Rattner absolutely savages Sheila Bair. I think Rattner treats Bair a little too harshly, but I agree that in this case, Bair was extremely unprofessional, and almost comically petty to boot. But I'm posting the full excerpt of Rattner's experience with Bair below the fold (it's long), so that you can make up your own mind.

The reason I think Rattner is a little too harsh on Bair is that, as head of the FDIC, she had the right to be concerned about the capital buffer at GMAC's bank (Ally), and to require higher capital levels. After all, it's the FDIC that would be on the hook if GMAC/Ally ever failed.

On the other hand, it's not at all clear that GMAC's capital level was her real concern (in fact, it's pretty clear that it wasn't her primary concern). Moreover, her stated cause for concern about GMAC — dealer floorplan loans — strongly suggests that her concern was less than genuine. Rattner is right that dealer floorplan loans are among the safest type of loans out there. Dealer floorplan ABS, which have a revolving structure similar to credit-card ABS, have miniscule historical loss rates (i.e., less than 1%), and have held up extremely well throughout the crisis. The fact that Bair cited dealer floorplan loans as her reason for requiring unusually high capital levels suggests that she either (a) didn't understand dealer floorplan loans (which would be bad in its own right), or (b) was being disingenuous.

I've always been surprised that Bair managed to become something of a hero among progressives. When Bair was the head of the CFTC in the 1990s, she fended off attempts to regulate OTC derivatives. And immediately after leaving the CFTC, she became a lobbyist for the New York Stock Exchange. Not exactly the profile of a progressive hero.

Anyway, here is Rattner's account of his experience with Bair:

From Overhaul: An Insider's Account of the Obama Administration's Emergency Rescue of the Auto Industry, by Steve Rattner (pp. 168–172, 236–237).

The new headache was Sheila Bair, the powerful chairwoman of the FDIC, which we needed to complete the GMAC and Chrysler Financial deal. Everything else in our charter depended on that. Without GMAC’s help, Chrysler would have no way to finance ongoing sales and the restructuring would fall through. General Motors’s survival would also be jeopardized.

I’d become aware of Bair’s central role gradually, while arranging for GMAC to take over Chrysler Financial’s lending activities. I had expected that obtaining the regulatory approvals would be easy. After all, didn’t we work for the same government? Didn’t we all want to save the economy from further shocks? That naiveté fell away quickly.

GMAC had three regulators: the Fed, the FDIC, and the state of Utah, where its Internet bank, Ally, was chartered. Since the Federal Reserve and the FDIC were independent agencies, for the first time in our “caper,” we could not use executive authority to direct the bureaucracy. No one—not the secretary of the Treasury, not even the President—could tell Ben Bernanke or Sheila Bair what to do. So the potential impediment at this point was not the recalcitrance of outside stakeholders but that of government colleagues.

We didn’t need much from the Fed, primarily just relief from something called Rule 23A, a Depression-era regulation prohibiting banks from lending money to “affiliated companies.” GM still had a significant stake in GMAC, but from our first meeting with Fed general counsel Scott Alvarez, we sensed a desire to help. Scott and his colleagues were diligent and careful—they made clear that they wouldn’t support a full merger of Chrysler Financial and GMAC. Yet they also signaled that they shared our desire to solve the auto crisis.

The FDIC, more directly and intimately involved with the bank subsidiary, had the authority to lift limits on deposits that GMAC had agreed to at the end of 2008 and controlled access to the TGLP. Its cooperation on both fronts was essential to GMAC’s plan for providing financing to GM and Chrysler customers. Our initial encounters were worrisome. Two Team Auto members, Brian Stern and Rob Fraser, had a Sunday session with the Fed also in attendance, where the FDIC was unyielding. A few days later, Deese and I accompanied Brian and Rob to FDIC headquarters to try to make some progress. But Bair’s lieutenant Chris Spoth and her deputy general counsel Roberta McInerney listened, gave away little, and promised no cooperation beyond checking with their boss.

The only specific objection raised by Spoth was GMAC’s financing of dealer inventories, which he viewed as excessively risky. The irony was that of all the possible reasons to worry about GMAC, “floor plan” was the least of them. In theory, GMAC can lose money on floor plan if a dealer won’t or can’t pay, but the deck is stacked in favor of GMAC. If a dealer defaults, GMAC has the right to seize the unsold cars and return them to GM for full value. What’s more, most dealers are personally liable for floor-plan loans, a tremendous incentive to make good on the debts. The historical loss rates on floor plan had been close to zero. The new risk, or course, was that GM itself might no longer be around to honor its repurchase agreement. But the President of the United States had just stood up to tell the world that a GM liquidation was unthinkable. What was the FDIC so worried about? We couldn’t figure it out.

It took me a while to understand that we were caught in the web of Sheila Bair’s own agenda. She was a lawyer from Kansas who, like Ben Bernanke, was a Bush administration appointee. Like Bernanke, she had also been an academic, though of lesser distinction. Unlike Bernanke, she was a politician too—in the 1990s she’d lost a Republican congressional primary in her home state.

Bair made her mark at the FDIC as an articulate early advocate of forceful action in the subprime mortgage crisis. At a time when the Bush administration was still wedded to its free-market, noninterventionist stance, she stood her ground. In 2008 Forbes named her the second most powerful woman in the world after Germany Chancellor Angela Merkel. A few pundits even touted her as a possible Treasury secretary for President Obama. But inside the bureaucracy she had a reputation for being a sharp-elbowed, sometimes disingenuous self-promoter. My colleagues who dealt with Bair during the banking crisis found the experience frustrating.

Bair’s concern was the safety and soundness of GMAC. We had told the regulators that we intended to recapitalize the company based on the results of the stress tests then under way. The goal of the stress testing, orchestrated by Tim for the nation’s nineteen largest bank holding companies, including GMAC, was the restoration of confidence in the banking system. If a company’s capitalization was found wanting, it would be required to raise enough additional money to weather a full range of economic storms. Ideally, investors would put up the funds, but implicit was the assurance that Washington would provide capital if the private market wouldn’t. GMAC was in such weak shape that its only possible source of capital would be TARP.

Based on the stress test results—not yet public but available to us—we had budgeted $13.1 billion of new capital for GMAC. Of that, $4 billion was to support the lending it would take over from Chrysler Financial. Bair didn’t believe those sums were enough. She suspected GMAC to be weaker than the stress test revealed, and didn’t trust de Molina’s ability to deliver what he promised. She also shared the FDIC members’ antipathy toward GMAC for its aggressiveness in Internet banking.

So the FDIC withheld its approvals, muttering about more capital. Making things worse, Spoth hinted at but would not spell out his boss’s demands. We made so little progress with him that I finally asked Tim to intercede. A summit meeting was booked for April 28, just two days before the President was to speak on television. It was in Tim’s small conference room, in the early evening of another unseasonably warm day, that I first came face-to-face with Sheila Bair—a small, trim woman about my age with brown hair, brown eyes, and an unsmiling, sour demeanor. According to Washington protocol, this was a “principals plus one” meeting. Sheila brought Spoth. Tim and I represented Treasury, leaving me without my finco experts Brian and Rob. Bernanke and Alvarez participated by phone.

One could hear bemusement in Bernanke’s soft voice coming through the speaker. His tone suggested that he was wondering, “Why are we even here?” The Fed was already prepared to meet a key demand by Bair, that GMAC be able to use dealer loans as collateral to borrow at the Fed’s “discount window.” But this meeting was about Bair’s needs. An effort was under way in Congress to increase from $30 billion to $100 billion the credit line at Treasury used by the FDIC to backstop its deposit-insurance fund. Bair made it clear that in exchange for helping GMAC, she expected Treasury’s support for the legislation. Such horse-trading is routine, and I didn’t question it. I just wished that she or Spoth had been more straightforward and had brought it up weeks earlier. But Tim readily acquiesced.

Next came a recital of grievances about GMAC. Weirdly, Bair attacked dealer financing anew, making it sound as if floor-plan lending were the reincarnation of subprime. It was as though we had not, just days before, explained to Spoth why floor-plan financing is about the least risky activity an auto finance company undertakes. He remained silent, and though I was incensed, so did I. As a “plus one,” I didn’t think it was my place to take on Bair in the presence of Bernanke and Geithner. The moment the meeting ended, I rushed down to see Brian Stern and Rob Fraser, wondering if I had somehow misunderstood everything I had heard about floor plan. They assured me that I hadn’t.

Clearly, the issue of the auto finance companies—which two months earlier we had viewed as the rail of the dog—was now a Great Dane of a problem. Soon to come was the news that Bair did not merely want Tim’s support for expanding her credit line; she wanted the legislation passed by Congress before she would agree to help GMAC. That wasn’t going to happen in the next forty-eight hours.

We agonized. It seemed insane to let Chrysler go down over her agenda. But Chrysler could not stay in business unless its dealers and customers got financing, and without FDIC approval, there was no way to provide it. We had fallen short on a key condition for not pulling the plug.

In close consultation with Larry and Tim, we decided the rescue was worth another gamble. We committed $7.5 billion of TARP funding to GMAC without waiting for the FDIC’s cooperation. In exchange, de Molina agreed to take on Chrysler Financial’s lending for two weeks so that the automaker could continue to sell cars. Two weeks would be long enough, we hoped, for the FDIC’s legislation to pass or for Bair to come around.

I reckoned the odds were on our side. For one thing, we’d held back $5.6 billion of the $13.1 billion earmarked for GMAC—additional capital that both de Molina and Bair wanted to see invested in the auto lender. Even if the GMAC arrangements fell through and we had to liquidate Chrysler in another two weeks, the consequences of having waited would not be severe. Keeping Chrysler on the dole for the extra days would cost taxpayers perhaps $500 million — a mere rounding error in the context of TARP’s $700 billion. And the people who bought Chryslers in the interim would be protected—we had a warranty guarantee program already in place.

Above all, I was banking on Bair’s self-interest. Being obstructionist had worked for her up to now. But as soon as she realized she was in danger of becoming the visible face of GMAC’s paralysis and Chrysler’s demise—as well as of the potential collapse of GM because it, too, depended on GMAC—I hoped that the hostages would be released... (pp. 168–172)

[...]

GMAC hung over me as a huge piece of unfinished business that could torpedo everything we were accomplishing. I spent days with Brian Stern and Rob Fraser figuring out how to structure and value the capital infusion that GMAC was going to need. Even more frustrating was continuing to do battle with the FDIC. As a way to keep the pressure on, we had proposed that GMAC take on the Chrysler financing business for only two weeks, seemingly plenty of time to tie up loose ends with the FDIC.

But the FDIC kept retrading and piling on new asks. Sheila Bair’s designated negotiator was Chris Spoth, the rather meek career FDIC official whom we had previously encountered. He seemed to have no authority whatsoever. More than once, we would come to an understanding on a point that we would confirm by e-mail, only to receive an e-mail back the next morning denying that an understanding had been reached. At another juncture, the FDIC asked for a letter saying that Treasury would stand behind GMAC no matter what, and then kept changing the language. Tim thought the new language would make the FDIC look weak and tried, unsuccessfully, to reach Bair. “I’ll write whatever you guys want, but I really think this is counter to your objective,” he told Spoth. Of course Spoth needed to check with Bair. “You’re right, let’s go back to the other language,” he responded a few minutes later. (Bair would duck even Tim when she wanted to; once her office said she was on a plane when in fact she wasn’t.) Bair also wanted a letter from Tim thanking her for assisting our effort; we took to calling this the “great American letter.”

Most frustrating was that after agreeing to provide the help we were seeking, the FDIC came back and increased the amount of capital that it wanted GMAC’s bank (Ally) to maintain to far beyond that required of any other bank. The excessive capital requirement would have many negative repercussions. It would reduce GMAC’s liquidity at the holding company and therefore its financial flexibility. Perhaps most importantly, it lowered the bank’s lending capacity, the opposite of what we were trying to achieve. And it reduced GMAC’s profitability and therefore the value of the $13.1 billion of new TARP money that we were preparing to invest. So the FDIC’s unreasonable requirement would cost U.S. taxpayers significant money. Whose side was the FDIC on, I wondered. We whittled back the duration of the higher capital requirement a bit but ultimately had to swallow and agree. We had no alternative... (pp. 236–237)

What Government Expansion?

Paul Krugman is, as usual, correct:

Op-Ed Contributor - Hey, Small Spender: Here’s the narrative you hear everywhere: President Obama has presided over a huge expansion of government, but unemployment has remained high. And this proves that government spending can’t create jobs. Here’s what you need to know: The whole story is a myth. There never was a big expansion of government spending. In fact, that has been the key problem with economic policy in the Obama years: we never had the kind of fiscal expansion that might have created the millions of jobs we need. Ask yourself: What major new federal programs have started up since Mr. Obama took office? Health care reform, for the most part, hasn’t kicked in yet, so that can’t be it. So are there giant infrastructure projects under way? No. Are there huge new benefits for low-income workers or the poor? No. Where’s all that spending we keep hearing about? It never happened.

To be fair, spending on safety-net programs, mainly unemployment insurance and Medicaid, has risen — because, in case you haven’t noticed, there has been a surge in the number of Americans without jobs and badly in need of help. And there were also substantial outlays to rescue troubled financial institutions.... But when people denounce big government, they usually have in mind the creation of big bureaucracies and major new programs. And that just hasn’t taken place.... The total number of government workers in America has been falling, not rising, under Mr. Obama.... Now, direct employment isn’t a perfect measure of the government’s size, since the government also employs workers indirectly when it buys goods and services from the private sector. And government purchases of goods and services have gone up. But adjusted for inflation, they rose only 3 percent over the last two years — a pace slower than that of the previous two years, and slower than the economy’s normal rate of growth.

So as I said, the big government expansion everyone talks about never happened....

[T]he stimulus wasn’t actually all that big compared with the size of the economy. Furthermore, it wasn’t mainly focused on increasing government spending... more than 40 percent came from tax cuts... another large chunk consisted of aid to state and local governments.... And federal aid to state and local governments wasn’t enough to make up for plunging tax receipts in the face of the economic slump....

The answer to the second question — why there’s a widespread perception that government spending has surged, when it hasn’t — is that there has been a disinformation campaign from the right, based on the usual combination of fact-free assertions and cooked numbers. And this campaign has been effective in part because the Obama administration hasn’t offered an effective reply.

Actually, the administration has had a messaging problem on economic policy ever since its first months in office, when it went for a stimulus plan that many of us warned from the beginning was inadequate.... You can argue that Mr. Obama got all he could... that an inadequate stimulus was much better than none at all (which it was). But that’s not an argument the administration ever made. Instead, it has insisted throughout that its original plan was just right....

And a side consequence of this awkward positioning is that officials can’t easily offer the obvious rebuttal to claims that big spending failed to fix the economy — namely, that thanks to the inadequate scale of the Recovery Act, big spending never happened in the first place.

But if they won’t say it, I will: if job-creating government spending has failed to bring down unemployment in the Obama era, it’s not because it doesn’t work; it’s because it wasn’t tried.

The claim that the scale of the recovery programs were right-sized for the problem--or would have been right-sized for the problem if not for the Greek financial crisis--is another unforced error by the Obama administration.

What Fiscal Expansion?

Paul Krugman is, as usual, correct:

Op-Ed Contributor - Hey, Small Spender: Here’s the narrative you hear everywhere: President Obama has presided over a huge expansion of government, but unemployment has remained high. And this proves that government spending can’t create jobs. Here’s what you need to know: The whole story is a myth. There never was a big expansion of government spending. In fact, that has been the key problem with economic policy in the Obama years: we never had the kind of fiscal expansion that might have created the millions of jobs we need. Ask yourself: What major new federal programs have started up since Mr. Obama took office? Health care reform, for the most part, hasn’t kicked in yet, so that can’t be it. So are there giant infrastructure projects under way? No. Are there huge new benefits for low-income workers or the poor? No. Where’s all that spending we keep hearing about? It never happened.

To be fair, spending on safety-net programs, mainly unemployment insurance and Medicaid, has risen — because, in case you haven’t noticed, there has been a surge in the number of Americans without jobs and badly in need of help. And there were also substantial outlays to rescue troubled financial institutions.... But when people denounce big government, they usually have in mind the creation of big bureaucracies and major new programs. And that just hasn’t taken place.... The total number of government workers in America has been falling, not rising, under Mr. Obama.... Now, direct employment isn’t a perfect measure of the government’s size, since the government also employs workers indirectly when it buys goods and services from the private sector. And government purchases of goods and services have gone up. But adjusted for inflation, they rose only 3 percent over the last two years — a pace slower than that of the previous two years, and slower than the economy’s normal rate of growth.

So as I said, the big government expansion everyone talks about never happened....

[T]he stimulus wasn’t actually all that big compared with the size of the economy. Furthermore, it wasn’t mainly focused on increasing government spending... more than 40 percent came from tax cuts... another large chunk consisted of aid to state and local governments.... And federal aid to state and local governments wasn’t enough to make up for plunging tax receipts in the face of the economic slump....

The answer to the second question — why there’s a widespread perception that government spending has surged, when it hasn’t — is that there has been a disinformation campaign from the right, based on the usual combination of fact-free assertions and cooked numbers. And this campaign has been effective in part because the Obama administration hasn’t offered an effective reply.

Actually, the administration has had a messaging problem on economic policy ever since its first months in office, when it went for a stimulus plan that many of us warned from the beginning was inadequate.... You can argue that Mr. Obama got all he could... that an inadequate stimulus was much better than none at all (which it was). But that’s not an argument the administration ever made. Instead, it has insisted throughout that its original plan was just right....

And a side consequence of this awkward positioning is that officials can’t easily offer the obvious rebuttal to claims that big spending failed to fix the economy — namely, that thanks to the inadequate scale of the Recovery Act, big spending never happened in the first place.

But if they won’t say it, I will: if job-creating government spending has failed to bring down unemployment in the Obama era, it’s not because it doesn’t work; it’s because it wasn’t tried.

The claim that the scale of the recovery programs were right-sized for the problem--or would have been right-sized for the problem if not for the Greek financial crisis--is another unforced error by the Obama administration.

A "Structural Unemployment" Nobel Prize

Very nice to see:

Diamond, Mortensen, Pissarides Share Nobel Prize (Update1) . By Rich Miller and Toby Alder

Oct. 11 (Bloomberg) -- Peter A. Diamond , Dale Mortensen and Christopher Pissarides shared the 2010 Nobel Prize in Economic Sciences for research into the difficulties of matching supply and demand, particularly in the labor market.

"This year's three Laureates have formulated a theoretical framework for search markets" such as ones where buyers look for sellers and applicants look for jobs, the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences, which selects the winner, said today in Stockholm.

Diamond, 70, is a Massachusetts Institute of Technology professor and a candidate for the Federal Reserve Board whose nomination has been held up by Senate Republicans. Pissarides, 62, teaches at the London School of Economics, and Mortensen, 71, is on the faculty at Northwestern University.

"Peter Diamond has analyzed the foundations of search markets," the academy said. "Dale Mortensen and Christopher Pissarides have expanded the theory and have applied it to the labor market. The laureates' models help us understand the ways in which unemployment, job vacancies, and wages are affected by regulation and economic policy."

Search theory tries to explain such conundrums as how high unemployment can be accompanied by a large number of job openings. One conclusion is that more generous jobless benefits lead to higher unemployment as those who are looking for work take longer to find it, the academy said.

links for 2010-10-11

Calculated Risk: Impact of estimated Benchmark Revision on Job Losses

The End of Free Trade? - WSJ.com

Balkinization

COGNITIVE SLAVES - Global Guerrillas

Orwell Watch: "Structural Unemployment" As Excuse to Do Nothing « naked capitalism

Balkinization

Obama era justice - Glenn Greenwald - Salon.com

Matthew Yglesias » Governing Better Would Have Helped Democrats

Young Frankenstein (1974) - Memorable quotes

Gillian Tett: Solving deleveraging puzzle will calm investors

Alan Rappeport: Summers calls for infrastructure spending

links for 2010-10-11

Calculated Risk: Impact of estimated Benchmark Revision on Job Losses

The End of Free Trade? - WSJ.com

Balkinization

COGNITIVE SLAVES - Global Guerrillas

Orwell Watch: "Structural Unemployment" As Excuse to Do Nothing « naked capitalism

Balkinization

Obama era justice - Glenn Greenwald - Salon.com

Matthew Yglesias » Governing Better Would Have Helped Democrats

Young Frankenstein (1974) - Memorable quotes

Gillian Tett: Solving deleveraging puzzle will calm investors

Alan Rappeport: Summers calls for infrastructure spending

links for 2010-10-11

Calculated Risk: Impact of estimated Benchmark Revision on Job Losses

The End of Free Trade? - WSJ.com

Balkinization

COGNITIVE SLAVES - Global Guerrillas

Orwell Watch: "Structural Unemployment" As Excuse to Do Nothing « naked capitalism

Balkinization

Obama era justice - Glenn Greenwald - Salon.com

Matthew Yglesias » Governing Better Would Have Helped Democrats

Young Frankenstein (1974) - Memorable quotes

Gillian Tett: Solving deleveraging puzzle will calm investors

Alan Rappeport: Summers calls for infrastructure spending

J. Bradford DeLong's Blog

- J. Bradford DeLong's profile

- 90 followers