J. Bradford DeLong's Blog, page 1159

August 24, 2014

Noted for Your Evening Procrastination for August 24, 2014

Over at Equitable Growth--The Equitablog

Over at Equitable Growth--The Equitablog

Nick Bunker: Weekend reading - Washington Center for Equitable Growth

Morning Must-Read: Kevin Drum: Welfare Reform and the Great Recession - Washington Center for Equitable Growth

Afternoon Must-Read: Paul Krugman: Core Inflation's Success - Washington Center for Equitable Growth

Afternoon Must-Read: Binyamin Applebaum: On the Decline in Labor Force Participation: Long-Term Trends in Economy More Worrisome Than Sudden Crash - NYTimes.com - Washington Center for Equitable Growth

Extra Credit for the Weekend: Janet Yellen: Labor Market Dynamics and Monetary Policy - Washington Center for Equitable Growth

Lunchtime Must-Read: James Pethokoukis: Does the GOP Have a Policy or a Messaging Problem? Both - Washington Center for Equitable Growth

Morning Must-Read: Joe Blasi: The Citizen’s Share: Reducing Inequality in the 21st Century - Washington Center for Equitable Growth

I Will Be Was on: SiriusXM 111: Business Radio 24/7 Business Talk from Wharton @ 1:00PM EDT Friday August 22, 2014.... - Washington Center for Equitable Growth

Plus:

Things to Read on the Evening of August 24, 2014 - Washington Center for Equitable Growth

Must- and Shall-Reads:

Simon Wren-Lewis: UK 2015: 2010 Déjà vu, but without the excuses

Cliff Asness: An Old Friend: The Stock Market’s Shiller P/E

Brad Plumer: Iceland's Bárðarbunga Volcano Has Started Erupting

Roger E. Backhouse and David Laidler: What Was Lost with IS-LM

Jason Karaian: Norway’s gargantuan sovereign wealth fund, by the numbers

Kevin Drum: Welfare Reform and the Great Recession "CBPP.... Welfare reform... in its first few years... seemed like a great success... but it was a bubbly economy that made the biggest difference. So how would welfare reform fare when it got hit with a real test? Answer: not so well. In late 2007 the Great Recession started, creating an extra 1.5 million families with children in poverty. TANF, however, barely responded at all. There was no room in strapped state budgets for more TANF funds.... This is why conservatives are so enamored of block grants. It's not because they truly believe that states are better able to manage programs for the poor than the federal government. That's frankly laughable. The reason they like block grants is because they know perfectly well that they'll erode over time. That's how you eventually drown the federal government in a bathtub. If Paul Ryan ever seriously proposes—and wins Republican support for—a welfare reform plan that includes block grants which (a) grow with inflation and (b) adjust automatically when recessions hit, I'll pay attention. Until then, they're just a Trojan Horse.... After all, those tax cuts for the rich won't fund themselves, will they?"

Kevin Drum: Welfare Reform and the Great Recession "CBPP.... Welfare reform... in its first few years... seemed like a great success... but it was a bubbly economy that made the biggest difference. So how would welfare reform fare when it got hit with a real test? Answer: not so well. In late 2007 the Great Recession started, creating an extra 1.5 million families with children in poverty. TANF, however, barely responded at all. There was no room in strapped state budgets for more TANF funds.... This is why conservatives are so enamored of block grants. It's not because they truly believe that states are better able to manage programs for the poor than the federal government. That's frankly laughable. The reason they like block grants is because they know perfectly well that they'll erode over time. That's how you eventually drown the federal government in a bathtub. If Paul Ryan ever seriously proposes—and wins Republican support for—a welfare reform plan that includes block grants which (a) grow with inflation and (b) adjust automatically when recessions hit, I'll pay attention. Until then, they're just a Trojan Horse.... After all, those tax cuts for the rich won't fund themselves, will they?"

Anne VanderMey: Joe Blasi's Easier Solution to Wealth Inequality?: "Joseph Blasi... along with... Richard Freeman and Douglas Kruse, wrote... The Citizen’s Share: Reducing Inequality in the 21st Century... corporate profit-sharing, employee stock ownership, and stock option plans.... The idea is rooted, he says, in the Founding Fathers’ original vision of widespread land ownership.... 'Why isn’t our plan radical?' Blasi asks. 'Because the founders of the American revolution had this view. That broad-based capital ownership was necessary for the republic to exist.'... 'We have to find a way for citizens to have some ownership of the technologies of the future.... We could have a future where technology creates a low feudal serf class—people with low wages or flat wages or high structural unemployment... or... a future where we have a smaller workweek and citizens broadly have more capital ownership.'"

James Pethokoukis: Does the GOP have a policy problem or a messaging problem? Both, it seems "Byron York.... 'The reformers face resistance not just from the corners of the conservative world that disagree with them on taxes, immigration, and other, perhaps lesser issues. They are also under attack from those in the Republican establishment who see no need to reevaluate GOP policies. According to this faction, the party doesn’t have a policy problem; it has a messaging problem.' Obviously I think the GOP has a policy problem. But that aside, Rs should not underestimate just how bad their messaging problem is.... GlobalStrategyGroup.... While voters by a huge margin prefer candidates focused on 'more economic growth' versus 'less income inequality', voters also think... raising the minimum wage and guaranteeing a minimum wage--are better for growth than business tax cuts or reducing top marginal income tax rates.... And... voters seem to have a much broader view of what policies qualify as 'pro-growth'. Whatever the economic argument the GOP is making, the party does not seem to be making it very well."

Binyamin Applebaum: On the Decline in Labor Force Participation: "Davis and Haltiwanger attribute... to the aging of the work force as people get older, they tend to change jobs less frequently. The decline in the creation of new companies is also playing a role. In effect, companies are getting older, too. This has been particularly pronounced in the retail sector, where giants like Walmart and McDonald’s offer relatively stable employment.... The cost of training workers has increased, partly because the share of all workers who require government licenses has grown by one estimate from about 5 percent in the 1950s to 29 percent in 2008. This discourages hiring. So do legal changes that have made it more difficult to fire employees.... It also mentions health insurance as a reason that employees may stay put. In the view of Mr. Davis and Mr. Haltiwanger, the recession just made a bad situation worse.... But economists and policy makers will have to reconcile the assertion that these trends were the dominant factors with the reality that the employment rate rose in the years before the recession, then dropped sharply during the recession. The new paper, like others of its genre, basically requires belief in a big coincidence: that a short-term catastrophe happened to coincide with the intensification of long-term trends — that the economy crashed at the moment that it was already beginning a gradual descent."

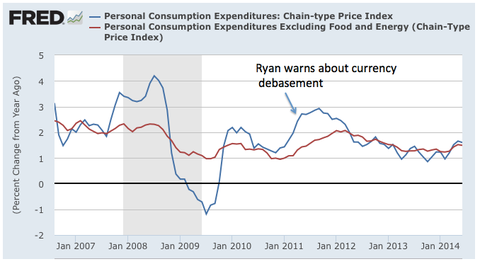

Paul Krugman: Core Success: "Cecchetti and Schoenholtz on core inflation reminds me that this concept, too, has been a huge success.... Those of us who looked at core inflation came in for a lot of abuse during the 'debasing the dollar' period of 2010-2011, when right-wingers were writing to Ben Bernanke to attack his policies and Paul Ryan was warning that rising commodity prices were the harbinger of runaway inflation. Assertions that fundamental inflation hadn’t gone up were met with ridicule and insults. But sure enough, the commodity price effect on inflation was a blip, and went away. And the inflation hawks learned their lesson, and revised their models. Hahahaha--just kidding."

Paul Krugman: Core Success: "Cecchetti and Schoenholtz on core inflation reminds me that this concept, too, has been a huge success.... Those of us who looked at core inflation came in for a lot of abuse during the 'debasing the dollar' period of 2010-2011, when right-wingers were writing to Ben Bernanke to attack his policies and Paul Ryan was warning that rising commodity prices were the harbinger of runaway inflation. Assertions that fundamental inflation hadn’t gone up were met with ridicule and insults. But sure enough, the commodity price effect on inflation was a blip, and went away. And the inflation hawks learned their lesson, and revised their models. Hahahaha--just kidding."

Barry Ritholtz: Your Weekend Reading on the CAPE: "When CAPE measures are less than 10, future 10-year returns are outstanding. Over the long run, returns fall the higher CAPE rises. However, in the short run, it is anyone’s guess. As Kitces has noted, CAPE is terrible as a market-timing tool, but it does add value for long-term retirement planning.... What CAPE does well: 1) Expected Returns: CAPE is good at providing expected 10-year equity returns.... 2) Market Peaks: When readings of CAPE are at very high (typically top quintile) it can signal a market top.... 3) Market Bottoms: When CAPE measures are at extreme lows, it generates an excellent long-term entry point into equities.... The measure of CAPE is simple, clean, easy to understand, and has a century-long track record. Thanks to Shiller, it was well-conceived and objective.... There are numerous criticisms of CAPE:1) Financial-Crisis-Distorted Earnings.... 2) Changes in Accounting.... 3) Low Interest Rates: With less competition from fixed income assets, stock markets end up with a higher P/E ratio than they otherwise would.... 4) Track record: Perhaps the biggest criticism is that since 1990, CAPE has spent 98 percent of the time above its historical average. The metric’s failure to mean-revert over the last 23 years raises questions about its long-term utility..."

Tim Harford: Why inflation remains best way to avoid stagnation: "Normally, when an economy slips into recession the standard response is to cut interest rates. This encourages us to spend, rather than save, giving the economy an immediate boost. Things become more difficult if nominal interest rates are already low.... There is a simple alternative, albeit one that carries risks. Central bank targets for inflation should be raised to 4 per cent. A credible higher inflation target would provide immediate stimulus (who wants to squirrel away money that is eroding at 4 per cent a year?) and would give central banks more leeway to cut real rates in future.... An inflation target of 4 per cent... will not happen.... What practical policy options remain? That is easy to see. We must cross our fingers and hope that Prof Summers is mistaken."

And Over Here:

Liveblogging World War II: August 24, 1944: Liberation of Paris (Brad DeLong's Grasping Reality...)

Long-Run Warranted Stock Valuations and Expected Returns: What Does the Shiller Data Tell Us? (Brad DeLong's Grasping Reality...)

Weekend Reading: Robots and Jobs (Brad DeLong's Grasping Reality...)

Weekend Reading: John Maynard Keynes (1926): The End of Laissez-Faire (Brad DeLong's Grasping Reality...)

Liveblogging World War I: August 23, 1914: Mons (Brad DeLong's Grasping Reality...)

For the Weekend: Marmot Edition (Brad DeLong's Grasping Reality...)

Weekend Reading: Janet Yellen: Labor Market Dynamics and Monetary Policy (Brad DeLong's Grasping Reality...)

Should Be Aware of:

Rebecca Solnit: Are the Techno Riche Really Ruining San Francisco?

Nick Rowe: Second best monetary and fiscal policy and the strategy space

Brad DeLong (2010): Is Macroeconomics Hard?

Paul Krugman: Draghi at Deflation Gulch:"I know Mario Draghi... I both like and admire him.... [I read] his Jackson Hole speech as the words of a man who knows perfectly well how dire the situation is, and is sailing as close to the wind as he can, but is all too aware of how inadequate that’s likely to be..."

Rakesh Vohra: Rethinking Intermediate Microeconomics "About a year ago, I chanced to remark upon the state of Intermediate Micro.... My chair very kindly gave me the chance to put the world to rights. Thus trapped... I begin next week. By the way, according to Alvin Roth, when an ancient like myself chooses to teach intermediate micro-economics it is a sure sign of senility. What do I intend to do differently?... Begin with monopoly, followed by imperfect competition, consumer theory, perfect competition, externalities and close with Coase. Why monopoly first?.... It involves single variable calculus rather than multivariable... student[s] enter the class thinking that firms `do things’ like set prices. The traditional sequence begins with a world where no one does anything. Undergraduates are not yet like the white queen, willing to believe 6 impossible things before breakfast.... Preferences... quasi-linear.... Producer theory? Covered under monopoly, avoiding needless duplication."

Liveblogging World War II: August 24, 1944: Liberation of Paris

From: World War II Today: Matthew Cobb: Eleven Days in August: The Liberation of Paris in 1944:

Matthew Halton was a Canadian reporter travelling with General Le Clerc’s tanks that were approaching Paris. During the day he was to broadcast:

Wherever we drive, in the areas west and south-west of the capital, people shout: “Look, they are going to Paris! ” But then we run into pockets of resistance here or there and are forced to turn back. It’s clear that we are seeing the disintegration of the German Army — but we never know when we are going to be shot at.

There are still some units of the German Army, fanatical men of the SS or armoured divisions, who are willing to fight to the last man. They are moving here and there all over this area, trying to coalesce into strong fighting forces…

The people everywhere are tense with emotion. Their love of freedom is so very deep, and a nightmare is lifting from their lives; and history races down the roads towards Paris.

When the first of the French tanks arrived in the capital at 11 o’clock at night it became clear that the following day would see full liberation of the city. Pierre Crénesse than made a dramatic broadcast on the newly liberated French public radio declaring:

Tomorrow morning will be the dawn of a new day for the capital. Tomorrow morning, Paris will be liberated, Paris will have finally rediscovered its true face.

Four years of struggle, four years that have been, for many people, years of prison, years of pain, of torture and, for many more, a slow death in the Nazi concentration camps, murder; but that’s all over…

For several hours, here in the centre of Paris, in the Cité, we have been living unforgettable moments. At the Préfecture, my comrades have explained to you that they are waiting for the commanding officers of the Leclerc Division and the American and French authorities.

Similarly, at the Hotel de Ville the Conseil National de la Résistance has been meeting for several hours. They are awaiting the French authorities. Meetings will take place, meetings which will be extremely symbolic, either there or in the Prefecture de Police — we don’t yet know where...

Long-Run Warranted Stock Valuations and Expected Returns: What Does the Shiller Data Tell Us?

Moving the calculations for last weekend's http://delong.typepad.com/sdj/2014/08/under-what-circumstances-should-you-worry-that-the-stock-market-is-too-high-the-honest-broker-for-the-week-of-august-16.html and http://delong.typepad.com/sdj/2014/08/under-what-circumstances-should-you-worry-that-the-stock-market-is-too-high-the-honest-broker-for-the-week-of-august-16.html over to R, as only people who really, really, really want to make bad mistakes do things in the un-debuggable Excel (or Numbers)...

Import data from http://delong.typepad.com/20140824_Shiller_Data.csv...

...define a function (shift) for constructing leads and lags, and perform elementary data manipulations: construct variables DATE (1871:1-2014:7), REAL_PRICE (1871:1-2014:7), REAL_DIVIDENDS (1871:1-2014:7), REAL_EARNINGS (1871:1-2014:7), MA10_EARNINGS (1881:1-2014:7) (the trailing 10-year moving average of real earnings that Campbell and Shiller use as their estimate of cyclically-adjusted permanent earnings), CUMULATIVE_RETURN (the cumulative return on a reinvested index portfolio since 1871 (1871:1-2014:7), LEAD10RETURN (1881:1-2004:7) (the 10-year forward realized annual rate of return), LEAD20RETURN (1881:1-1994:7) (the 20-year forward realized annual rate of return), CAPE (1881:1-2014:7) (the Campbell-Shiller cyclically-adjusted price-earnings ratio), and EXCESS_RETURNS (1871:1-2004:7) (the difference between the 10-year forward annual realized rate of return and the cyclically-adjusted earnings yield):

{r, echo=FALSE} # start the R block

Shiller

DATE = Shiller$DATE

REAL_PRICE = Shiller$REAL_PRICE

REAL_DIVIDENDS = Shiller$REAL_DIVIDENDS

REAL_EARNINGS=Shiller$REAL_EARNINGS

MA10_EARNINGS = Shiller$MA.10._OF_EARNINGS

CUMULATIVE_RETURN = Shiller$CUMULATIVE_RETURN # pull out the variables

CAPE = REAL_PRICE/MA10_EARNINGS # define the Campbell-Shiller cyclically-adjusted price-earnings ratio--CAPE--as the real price divided by a 10-year trailing moving average of real income

shift1)

return(sapply(shift_by,shift, x=x))

out 0 )

out< 0 )

out

LEAD1MORETURN = (shift(REAL_PRICE,1) + REAL_DIVIDENDS/12)/REAL_PRICE-1

LEAD1YRRETURN = (shift(CUMULATIVE_RETURN,12)/CUMULATIVE_RETURN) - 1

LEAD10RETURN = (shift(CUMULATIVE_RETURN,120)/CUMULATIVE_RETURN)^(1/10)-1

LEAD20RETURN = (shift(CUMULATIVE_RETURN,240)/CUMULATIVE_RETURN)^(1/20)-1

EXCESS_RETURN = LEAD10RETURN - 1/CAPE # define the 1-mo return, the 10-year realized forward return, the 20-year realized forward return, and the deviation of realized returns from the CAPE earnings yield

Make sure we have all the data and they look like they should...

{r, echo=FALSE}

plot(DATE,REAL_PRICE, main="Real Stock Index Price", xlab="Date", ylab="Real Stock Index Price", pch=16, cex=0.5)

plot(DATE,REAL_DIVIDENDS, main="Real Stock Index Dividends", xlab="Date", ylab="Real Stock Index Dividends", pch=16, cex=0.5)

plot(DATE,REAL_EARNINGS, main="Real Stock Index Earnings", xlab="Date", ylab="Real Stock Index Earnings", pch=16, cex=0.5)

plot(DATE,MA10_EARNINGS, main="Cyclically-Adjusted Real Earnings", xlab="Date", ylab="10-Yr MA of Trailing Real Earnings ", pch=16, cex=0.5)

plot(DATE,CAPE, xlab="Date", main="Campbell-Shiller Cyclically-Adjusted Price-Earnings", ylab="Campbell-Shiller CAPE", pch=16, cex=0.5)

plot(DATE,LEAD10RETURN, main="Realized Ten-Year Forward Returns", xlab="Date", ylab="10-Yr Forward Realized Annual Rate of Return", pch=16, cex=0.5)

plot(DATE,LEAD20RETURN, main="Realized Twenty-Year Forward Returns", xlab="Date", ylab="20-Year Forward Realized Annual Rate of Return", pch=16, cex=0.5)

plot(DATE,EXCESS_RETURN, main="Realized Ten-Year Excess Return Over CAPE Earnings Yield", xlab="Date", ylab="10-Year Excess Return Over 1/CAPE", pch=16, cex=0.5)

plot(DATE,LEAD1MORETURN, main="One-Month Returns", xlab="Date", ylab="1-Month Realized Forward Return", pch=16, cex=0.5, xlim=c(1870,2015))

plot(DATE,LEAD1YRRETURN, main="One-Year Returns", xlab="Date", ylab="1-Year Realized Forward Return", pch=16, cex=0.5, xlim=c(1870,2015)) # plot everything and look at it

Yes, everything as it should be so far...

Now on to the analysis proper...

Let's start with the simplest possible forward-return regression: regressing the ten-year future realized return in the Campbell-Shiller stock index database on the Campbell-Shiller cyclically-adjusted earnings yield INVERSECAPE--the inverse of the CAPE:

{r, echo=FALSE}

INVERSECAPE = 1/CAPE

return_regression_2.lm = lm(formula = LEAD10RETURN ~ INVERSECAPE)

summary(return_regression_2.lm)

In response to:

Call: lm(formula = LEAD10RETURN ~ INVERSECAPE)

R reports:

Residuals:

Min 1Q Median 3Q Max

-0.106298 -0.030839 0.002955 0.028179 0.103866

Coefficients:

Estimate Std. Error t value Pr(>|t|)

(Intercept) -0.007659 0.002878 -2.661 0.00788

INVERSECAPE 0.995904 0.036513 27.275 < 2e-16

Residual standard error: 0.04284 on 1482 degrees of freedom

(240 observations deleted due to missingness)

Multiple R-squared: 0.3342,

Adjusted R-squared: 0.3338

F-statistic: 743.9 on 1 and 1482 DF,

p-value: < 2.2e-16

The significance levels that R reports are wrong: its naive regression package assumes that sac of the 1482 observed 10-year returns is independent of each of the others. They are not. Each monthly return shows up as a component in 120 10-year returns. The right t-value for the cyclically-adjusted earnings yield INVERSECAPE is not 27.3 but rather something between 4 and 5--still highly, highly significant.

More important, a third of the variance in future 10-year returns is accounted for by knowing the value of INVERSECAPE. More important, the intercept is zero and the coefficient is 1. More important, the ability of the earnings yield to forecast future 10-year returns remains highly, highly significant. More important, you get these not just by knowing what INVERSECAPE is and then performing some linear transformation on it, but by just the INVERSECAPE itself. What this equation tells us is that, since 1881, 0 + 1 x INVERSECAPE is a remarkably good linear forecast of ten-year future returns.

{r, echo=FALSE}

plot(INVERSECAPE,LEAD10RETURN, main="Realized Ten-Year Forward Returns vs. CAPE Earnings Yield", xlab="CAPE Earnings Yield", ylab="10-Year Realized Foreward Returns", pch=16, cex=0.5)

abline(lm(LEAD10RETURN ~ INVERSECAPE))

Note that this particular functional form for understanding how knowing CAPE should shape your forecast of future returns is not important. INVERSECAPE is convenient because it comes in the same units as returns. But regressing future long-run returns on CAPE itself does about as well. Submit:

{r, echo=FALSE}

INVERSECAPE = 1/CAPE

return_regression_2.lm = lm(formula = LEAD10RETURN ~ CAPE)

summary(return_regression_2.lm)

And R spits out:

Call: lm(formula = LEAD10RETURN ~ CAPE)

Residuals:

Min 1Q Median 3Q Max

-0.116777 -0.029650 0.004347 0.028478 0.093157

Coefficients:

Estimate Std. Error t value Pr(>|t|)

(Intercept) 0.1383475 0.0029889 46.29

Residual standard error: 0.04321 on 1482 degrees of freedom

(240 observations deleted due to missingness)

Multiple R-squared: 0.3226,

Adjusted R-squared: 0.3221

F-statistic: 705.8 on 1 and 1482 DF,

p-value: < 2.2e-16

The same 1/3 of variance accounted for. The same parameter at the median of the distribution. This formulation suggests that expected ten-year real returns turn negative at a CAPE value of above 30--that offsetting the 3.3% real earnings yield at that point is an anticipated equal decline in valuation metrics over the next ten years, but the plot reveals that this prediction relies heavily on the linearity. Submitting:

{r, echo=FALSE}

plot(CAPE,LEAD10RETURN, main="Realized Ten-Year Forward Returns vs. CAPE ", xlab="CAPE", ylab="10-Year Realized Foreward Returns", pch=16, cex=0.5)

abline(lm(LEAD10RETURN ~ CAPE))

produces from R:

Basically what we know about expected returns is that on the one occasion when CAPE rose above 30, the dot-com crash of 2000 was in the near future and the housing crash of 2008 came into the ten-year return window. That is not much information on which to base a long-run "sell" decision.

Let's think about not what economists call risk--variation about expected returns--but what people call risk: the chance that your money won't be there in real terms. The lowest realized 10-year returns did indeed come when the CAPE was at its highest and thus the earnings yield INVERSECAPE was at its lowest. But the second-lowest returns happened when CAPE was not high but normal. And the other periods of negative realized returns happened when CAPE was high, but not that low. Plus there is a lot of mass of the distribution with both high CAPE and very healthy positive returns. What's going on?

{r, echo=FALSE}

plot(DATE,LEAD10RETURN, main="Realized Ten-Year Forward Returns", xlab="DATE", ylab="10-Year Realized Foreward Returns", pch=16, cex=0.5)

plot(CAPE,LEAD10RETURN, main="Realized Ten-Year Forward Returns", xlab="DATE", ylab="10-Year Realized Foreward Returns", pch=16, cex=0.5)

There are only four historical periods during which a ten-year investment in the S&P has not at least held its real value: ten years before the post-World War I deflation and the post-WWI depression of the start of the 1920s; (barely) in the Great Depression and the WWII inflation; 10 years before the stagflation of the 1970s and the subsequent Volcker depression; and 10 years before the recent financial unpleasantness for those dates where the ten-year return window includes both the dot-com and the housing-bubble crashes.

There is little more to be squeezed out of this particular data set.

{r, echo=FALSE}

return_regression_3.lm = lm(formula = LEAD10RETURN ~ INVERSECAPE + CAPE + CAPESQ)

summary(return_regression_3.lm)

All the data will say is that once the CAPE earnings yield is known there is absolutely no point in adding either CAPE or CAPE2 in the hopes of picking up some predictive ability via curvature, while the computer does have a (weak) preference for placing predictive weight on the yield if it is added to the regression:

Call: lm(formula = LEAD10RETURN ~ INVERSECAPE + CAPE + CAPESQ)

Residuals:

Min 1Q Median 3Q Max

-0.110743 -0.029043 0.002934 0.028354 0.099453

Coefficients:

Estimate Std. Error t value Pr(>|t|)

(Intercept) 2.550e-02 2.612e-02 0.976 0.329

INVERSECAPE 7.356e-01 1.268e-01 5.801 8.07e-09

CAPE -2.194e-04 1.559e-03 -0.141 0.888

CAPESQ -3.578e-05 2.679e-05 -1.336 0.182

Residual standard error: 0.0421 on 1480 degrees of freedom

(240 observations deleted due to missingness)

Multiple R-squared: 0.358,

Adjusted R-squared: 0.3567

F-statistic: 275.1 on 3 and 1480 DF,

p-value: < 2.2e-16

August 23, 2014

Weekend Reading: Robots and Jobs

From David Leonhardt's The Upshot:

From David Leonhardt's The Upshot:

Claire Cain Miller: Will You Lose Your Job to a Robot? Silicon Valley Is Split: Following are a sampling of the points of view expressed in the Pew report.

Most utopian: “How unhappy are you that your dishwasher has replaced washing dishes by hand, your washing machine has displaced washing clothes by hand or your vacuum cleaner has replaced hand cleaning? My guess is this ‘job displacement’ has been very welcome, as will the ‘job displacement’ that will occur over the next 10 years. This is a good thing. Everyone wants more jobs and less work.” — Hal Varian, chief economist at Google

Most dystopian: “We’re going to have to come to grips with a long-term employment crisis and the fact that — strictly from an economic point of view, not a moral point of view — there are more and more ‘surplus humans.'”— Karl Fogel, partner at Open Tech Strategies, an open-source technology firm

Most hopeful: “Advances in A.I. [artificial intelligence] and robotics allow people to cognitively offload repetitive tasks and invest their attention and energy in things where humans can make a difference. We already have cars that talk to us, a phone we can talk to, robots that lift the elderly out of bed and apps that remind us to call Mom. An app can dial Mom’s number and even send flowers, but an app can’t do that most human of all things: emotionally connect with her.” — Pamela Rutledge, director of the Media Psychology Research Center, a nonprofit

Most grim: “The degree of integration of A.I. into daily life will depend very much, as it does now, on wealth. The people whose personal digital devices are day-trading for them, and doing the grocery shopping and sending greeting cards on their behalf, are people who are living a different life than those who are worried about missing a day at one of their three jobs due to being sick, and losing the job and being unable to feed their children.” — Bill Woodcock, executive director for the Packet Clearing House, a nonprofit research institute on Internet traffic

Most frightening to Americans: “Globally, more jobs will be created by manufacturing of robots, but in developed countries like the U.S. and Europe jobs will be displaced by manufacturing by robots.” — Mike Liebhold, distinguished fellow at the Institute for the Future, a nonprofit research group

Most frightening to parents: “Only the best-educated humans will compete with machines. And education systems in the U.S. and much of the rest of the world are still sitting students in rows and columns, teaching them to keep quiet and memorize what is told to them, preparing them for life in a 20th century factory.” — Howard Rheingold, tech writer and analyst

Most frightening to college students: “We hardly dwell on the fact that someone trying to pick a career path that is not likely to be automated will have a very hard time making that choice. X-ray technician? Outsourced already, and automation in progress. The race between automation and human work is won by automation.” — Jerry Michalski, founder of the Relationship Economy eXpedition

Most frightening to humans: “Robotic sex partners will be commonplace.… The central question of 2025 will be: What are people for in a world that does not need their labor, and where only a minority are needed to guide the ‘bot-based economy?'” — Stowe Boyd, lead researcher for GigaOM Research

Most complimentary toward humans: “Employment will be mostly very skilled labor — and even those jobs will be continuously whittled away by increasingly sophisticated machines. Live, human salespeople, nurses, doctors, actors will be symbols of luxury, the silk of human interaction as opposed to the polyester of simulated human contact.” — Judith Donath, fellow at Harvard University’s Berkman Center for Internet & Society

Most frightening to men: “The biggest exception will be jobs that depend upon empathy as a core capacity — schoolteacher, personal service worker, nurse. These jobs are often those traditionally performed by women. One of the bigger social questions of the mid-late 2020s will be the role of men in this world.” — Jamais Cascio, technology writer and futurist

Most skeptical: “As an engineering community, we’ve been working on robotics and A.I. for a long time. The rationale behind today’s optimism is that with every technology generation, Moore’s Law brings us closer to having enough computational resources to solve these problems well. But 2025 feels too soon — it takes decades for fundamental ideas like quantum mechanics to be fully worked out by a research community.” — John Lazzaro, visiting lecturer in computer science at the University of California, Berkeley

Most reassuring:: “The technodeterminist-negative view, that automation means jobs loss, end of story, versus the technodeterminist-positive view, that more and better jobs will result, both seem to me to make the error of confusing potential outcomes with inevitability. A technological advance by itself can either be positive or negative for jobs, depending on the social structure as a whole. This is not a technological consequence; rather, it’s a political choice.” — Seth Finkelstein, software programmer and consultant

Liveblogging World War I: August 23, 1914: Mons

From Barbara Tuchman's The Guns of August:

From Barbara Tuchman's The Guns of August:

Kluck moved wrathfully on Mons. His orders for August 23 were to cross the canal, occupy the ground to the south, and force the enemy back into Maubeuge while cutting off his retreat from the west.... Kluck was keeping as far to the west as he could, and thus Haig’s corps was not attacked in the fighting of August 23 that was to become known to history and to legend as the Battle of Mons. Sir John French’s headquarters were at Le Cateau, 30 miles south of Mons. The 5 divisions he had to direct over a front of 25 miles—in contrast to Lanrezac’s 13 divisions over a front of 50 miles—hardly required him to be that far back. Sir John’s hesitant frame of mind may have dictated the choice....

At six in the morning when Sir John French gave his last instructions to corps commanders, his—or his staff’s—estimate of the enemy strength they were about to meet was still the same: one or at most two army corps plus cavalry. In fact, at that moment von Kluck had four corps and three cavalry divisions—160,000 men with 600 guns—within striking distance of the BEF whose strength was 70,000 men and 300 guns.... At 9:00 A.M. the first German guns opened fire on the British positions.... Lunging at it in their dense formation, the Germans offered “the most perfect targets” to the British riflemen who, well dug in and expertly trained, delivered fire of such rapidity and accuracy that the Germans believed they faced machine guns. After repeated assault waves were struck down, they brought up more strength and changed to open formations. The British, under orders to offer “stubborn resistance,” kept up their fire from the salient despite steadily growing casualties.

From 10:30 on, the battle was extended along the straight section of the canal to the west as battery after battery of German guns, first of the IIIrd and then of the IVth Corps, were brought into action. By three in the afternoon when the British regiments holding the salient had withstood shelling and infantry assault for six hours, the pressure on their dwindling numbers became too strong. After blowing up the bridge at Nimy they fell back, company by company, to a second line of defense that had been prepared two or three miles to the rear. As the yielding of the salient endangered the troops holding the straight section of the canal, these too were now ordered to withdraw, beginning about five in the evening. At Jemappes, where the loop joins the straight section, and at Mariette two miles to the west sudden peril loomed when it was found that the bridges could not be destroyed for lack of an exploder to fire the charges. A rush by the Germans across the canal in the midst of the retirement could convert orderly retreat to a rout and might even effect a breakthrough. No single Horatius could hold the bridge, but Captain Wright of the Royal Engineers swung himself hand over hand under the bridge at Mariette in an attempt to connect the charges. At Jemappes a corporal and a private worked at the same task for an hour and a half under continuous fire. They succeeded, and were awarded the V.C. and D.C.M.; but Captain Wright, though he made a second attempt in spite of being wounded, failed. He too won the V.C., and three weeks later was killed on the Aisne....

Fortunately for the British von Kluck’s more than double superiority in numbers had not been made use of. Unable, because of Bülow’s hampering orders, to find the enemy flank and extend himself around it, Kluck had met the British head on with his two central corps, the IIIrd and IVth, and suffered the heavy losses consequent upon frontal attack. One German reserve captain of the IIIrd Corps found himself the only surviving officer of his company and the only surviving company commander of his battalion. “You are my sole support,” wailed the major. “The battalion is a mere wreck, my proud, beautiful battalion …” and the regiment is “shot down, smashed up—only a handful left.” The colonel of the regiment, who like everyone in war could judge the course of combat only by what was happening to his own unit, spent an anxious night, for as he said, “If the English have the slightest suspicion of our condition, and counterattack, they will simply run over us.” Neither of von Kluck’s flanking corps, the IInd on his right and the IXth on his left, had been brought into the battle....

Henry Wilson was mentally still charging forward with medieval ardor in Plan 17, unaware that it was now about as applicable to the situation as the longbow.... Wilson... was eager for an offensive next day. He had made a “careful calculation” and concluded “that we had only one corps and one cavalry division (possibly two corps) opposite to us.”... At 11:00 P.M. Lieutenant Spears arrived after a hurried drive from Fifth Army headquarters to bring the bitter word that General Lanrezac was breaking off battle and withdrawing the Fifth Army to a line in the rear of the BEF.... Lanrezac’s retreat, leaving the BEF in the air, put them in instant peril. In anxious conference it was decided to draw back the troops at once....

So ended the first day of combat for the first British soldiers to fight a European enemy since the Crimea and the first to fight on European soil since Waterloo. It was a bitter disappointment: both for the Ist Corps which had marched forward through the heat and dust and now had to turn and march back almost without having fired a shot; even more for the IInd Corps which felt proud of its showing against a famed and formidable enemy, knew nothing of his superior numbers or of the Fifth Army’s withdrawal, and could not understand the order to retreat.

It was a “severe” disappointment to Henry Wilson who laid it all at the door of Kitchener and the Cabinet for having sent only four divisions instead of six. Had all six been present, he said with that marvelous incapacity to admit error that was to make him ultimately a Field Marshal, “this retreat would have been an advance and defeat would have been a victory.”

August 22, 2014

For the Weekend: Marmot Edition

Weekend Reading: Janet Yellen: Labor Market Dynamics and Monetary Policy

Janet L. Yellen: Labor Market Dynamics and Monetary Policy: "In the five years since the end of the Great Recession...

Janet L. Yellen: Labor Market Dynamics and Monetary Policy: "In the five years since the end of the Great Recession...

...the economy has made considerable progress in recovering from the largest and most sustained loss of employment in the United States since the Great Depression.[1] More jobs have now been created in the recovery than were lost in the downturn, with payroll employment in May of this year finally exceeding the previous peak in January 2008. Job gains in 2014 have averaged 230,000 a month, up from the 190,000 a month pace during the preceding two years. The unemployment rate, at 6.2 percent in July, has declined nearly 4 percentage points from its late 2009 peak. Over the past year, the unemployment rate has fallen considerably, and at a surprisingly rapid pace. These developments are encouraging, but it speaks to the depth of the damage that, five years after the end of the recession, the labor market has yet to fully recover.

The Federal Reserve’s monetary policy objective is to foster maximum employment and price stability. In this regard, a key challenge is to assess just how far the economy now stands from the attainment of its maximum employment goal. Judgments concerning the size of that gap are complicated by ongoing shifts in the structure of the labor market and the possibility that the severe recession caused persistent changes in the labor market’s functioning.

These and other questions about the labor market are central to the conduct of monetary policy, so I am pleased that the organizers of this year’s symposium chose labor market dynamics as its theme. My colleagues on the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) and I look to the presentations and discussions over the next two days for insights into possible changes that are affecting the labor market. I expect, however, that our understanding of labor market developments and their potential implications for inflation will remain far from perfect. As a consequence, monetary policy ultimately must be conducted in a pragmatic manner that relies not on any particular indicator or model, but instead reflects an ongoing assessment of a wide range of information in the context of our ever-evolving understanding of the economy.

The Labor Market Recovery and Monetary Policy

In my remarks this morning, I will review a number of developments related to the functioning of the labor market that have made it more difficult to judge the remaining degree of slack. Differing interpretations of these developments affect judgments concerning the appropriate path of monetary policy.

Before turning to the specifics, however, I would like to provide some context concerning the role of the labor market in shaping monetary policy over the past several years. During that time, the FOMC has maintained a highly accommodative monetary policy in pursuit of its congressionally mandated goals of maximum employment and stable prices. The Committee judged such a stance appropriate because inflation has fallen short of our 2 percent objective while the labor market, until recently, operated very far from any reasonable definition of maximum employment.

The FOMC’s current program of asset purchases began when the unemployment rate stood at 8.1 percent and progress in lowering it was expected to be much slower than desired. The Committee’s objective was to achieve a substantial improvement in the outlook for the labor market, and as progress toward this goal has materialized, we have reduced our pace of asset purchases and expect to complete this program in October. In addition, in December 2012, the Committee modified its forward guidance for the federal funds rate, stating that:

as long as the unemployment rate remains above 6-1/2 percent, inflation between one and two years ahead is projected to be no more than a half percentage point above the Committee’s 2 percent longer-run goal, and longer-term inflation expectations continue to be well anchored

the Committee would not even consider raising the federal funds rate above the 0 to 1/4 percent range.[2] This “threshold based” forward guidance was deemed appropriate under conditions in which inflation was subdued and the economy remained unambiguously far from maximum employment.

Earlier this year, however, with the unemployment rate declining faster than had been anticipated and nearing the 6-1/2 percent threshold, the FOMC recast its forward guidance, stating that:

in determining how long to maintain the current 0 to 1/4 percent target range for the federal funds rate, the Committee would assess progress--both realized and expected--toward its objectives of maximum employment and 2 percent inflation.[3]

As the recovery progresses, assessments of the degree of remaining slack in the labor market need to become more nuanced because of considerable uncertainty about the level of employment consistent with the Federal Reserve’s dual mandate. Indeed, in its 2012 statement on longer-run goals and monetary policy strategy, the FOMC explicitly recognized that factors determining maximum employment “may change over time and may not be directly measurable,” and that assessments of the level of maximum employment “are necessarily uncertain and subject to revision.”[4] Accordingly, the reformulated forward guidance reaffirms the FOMC’s view that policy decisions will not be based on any single indicator, but will instead take into account a wide range of information on the labor market, as well as inflation and financial developments.[5]

-

Interpreting Labor Market Surprises: Past and Future

The assessment of labor market slack is rarely simple and has been especially challenging recently. Estimates of slack necessitate difficult judgments about the magnitudes of the cyclical and structural influences affecting labor market variables, including labor force participation, the extent of part-time employment for economic reasons, and labor market flows, such as the pace of hires and quits. A considerable body of research suggests that the behavior of these and other labor market variables has changed since the Great Recession.[6] Along with cyclical influences, significant structural factors have affected the labor market, including the aging of the workforce and other demographic trends, possible changes in the underlying degree of dynamism in the labor market, and the phenomenon of “polarization”--that is, the reduction in the relative number of middle-skill jobs.[7]

Consider first the behavior of the labor force participation rate, which has declined substantially since the end of the recession even as the unemployment rate has fallen. As a consequence, the employment-to-population ratio has increased far less over the past several years than the unemployment rate alone would indicate, based on past experience. For policymakers, the key question is: What portion of the decline in labor force participation reflects structural shifts and what portion reflects cyclical weakness in the labor market? If the cyclical component is abnormally large, relative to the unemployment rate, then it might be seen as an additional contributor to labor market slack.

Labor force participation peaked in early 2000, so its decline began well before the Great Recession. A portion of that decline clearly relates to the aging of the baby boom generation. But the pace of decline accelerated with the recession. As an accounting matter, the drop in the participation rate since 2008 can be attributed to increases in four factors: retirement, disability, school enrollment, and other reasons, including worker discouragement.[8] Of these, greater worker discouragement is most directly the result of a weak labor market, so we could reasonably expect further increases in labor demand to pull a sizable share of discouraged workers back into the workforce. Indeed, the flattening out of the labor force participation rate since late last year could partly reflect discouraged workers rejoining the labor force in response to the significant improvements that we have seen in labor market conditions. If so, the cyclical shortfall in labor force participation may have diminished.

What is more difficult to determine is whether some portion of the increase in disability rates, retirements, and school enrollments since the Great Recession reflects cyclical forces. While structural factors have clearly and importantly affected each of these three trends, some portion of the decline in labor force participation resulting from these trends could be related to the recession and slow recovery and therefore might reverse in a stronger labor market.[9] Disability applications and educational enrollments typically are affected by cyclical factors, and existing evidence suggests that the elevated levels of both may partly reflect perceptions of poor job prospects.[10] Moreover, the rapid pace of retirements over the past few years might reflect some degree of pull-forward of future retirements in the face of a weak labor market. If so, retirements might contribute less to declining participation in the period ahead than would otherwise be expected based on the aging workforce.[11]

A second factor bearing on estimates of labor market slack is the elevated number of workers who are employed part time but desire full-time work (those classified as “part time for economic reasons”). At nearly 5 percent of the labor force, the number of such workers is notably larger, relative to the unemployment rate, than has been typical historically, providing another reason why the current level of the unemployment rate may understate the amount of remaining slack in the labor market. Again, however, some portion of the rise in involuntary part-time work may reflect structural rather than cyclical factors. For example, the ongoing shift in employment away from goods production and toward services, a sector which historically has used a greater portion of part-time workers, may be boosting the share of part-time jobs. Likewise, the continuing decline of middle-skill jobs, some of which could be replaced by part-time jobs, may raise the share of part-time jobs in overall employment.[12] Despite these challenges in assessing where the share of those employed part time for economic reasons may settle in the long run, the sharp run-up in involuntary part-time employment during the recession and its slow decline thereafter suggest that cyclical factors are significant.

Private sector labor market flows provide additional indications of the strength of the labor market. For example, the quits rate has tended to be pro-cyclical, since more workers voluntarily quit their jobs when they are more confident about their ability to find new ones and when firms are competing more actively for new hires. Indeed, the quits rate has picked up with improvements in the labor market over the past year, but it still remains somewhat depressed relative to its level before the recession. A significant increase in job openings over the past year suggests notable improvement in labor market conditions, but the hiring rate has only partially recovered from its decline during the recession. Given the rise in job vacancies, hiring may be poised to pick up, but the failure of hiring to rise with vacancies could also indicate that firms perceive the prospects for economic growth as still insufficient to justify adding to payrolls.

Alternatively, subdued hiring could indicate that firms are encountering difficulties in finding qualified job applicants. As is true of the other indicators I have discussed, labor market flows tend to reflect not only cyclical but also structural changes in the economy. Indeed, these flows may provide evidence of reduced labor market dynamism, which could prove quite persistent.[13] That said, the balance of evidence leads me to conclude that weak aggregate demand has contributed significantly to the depressed levels of quits and hires during the recession and in the recovery.

One convenient way to summarize the information contained in a large number of indicators is through the use of so-called factor models. Following this methodology, Federal Reserve Board staff developed a labor market conditions index from 19 labor market indicators, including four I just discussed.[14] This broadly based metric supports the conclusion that the labor market has improved significantly over the past year, but it also suggests that the decline in the unemployment rate over this period somewhat overstates the improvement in overall labor market conditions.

Finally, changes in labor compensation may also help shed light on the degree of labor market slack, although here, too, there are significant challenges in distinguishing between cyclical and structural influences. Over the past several years, wage inflation, as measured by several different indexes, has averaged about 2 percent, and there has been little evidence of any broad-based acceleration in either wages or compensation. Indeed, in real terms, wages have been about flat, growing less than labor productivity. This pattern of subdued real wage gains suggests that nominal compensation could rise more quickly without exerting any meaningful upward pressure on inflation. And, since wage movements have historically been sensitive to tightness in the labor market, the recent behavior of both nominal and real wages point to weaker labor market conditions than would be indicated by the current unemployment rate.

There are three reasons, however, why we should be cautious in drawing such a conclusion. First, the sluggish pace of nominal and real wage growth in recent years may reflect the phenomenon of “pent-up wage deflation.”[15] The evidence suggests that many firms faced significant constraints in lowering compensation during the recession and the earlier part of the recovery because of “downward nominal wage rigidity”--namely, an inability or unwillingness on the part of firms to cut nominal wages. To the extent that firms faced limits in reducing real and nominal wages when the labor market was exceptionally weak, they may find that now they do not need to raise wages to attract qualified workers. As a result, wages might rise relatively slowly as the labor market strengthens. If pent-up wage deflation is holding down wage growth, the current very moderate wage growth could be a misleading signal of the degree of remaining slack. Further, wages could begin to rise at a noticeably more rapid pace once pent-up wage deflation has been absorbed.

Second, wage developments reflect not only cyclical but also secular trends that have likely affected the evolution of labor’s share of income in recent years. As I noted, real wages have been rising less rapidly than productivity, implying that real unit labor costs have been declining, a pattern suggesting that there is scope for nominal wages to accelerate from their recent pace without creating meaningful inflationary pressure. However, research suggests that the decline in real unit labor costs may partly reflect secular factors that predate the recession, including changing patterns of production and international trade, as well as measurement issues.16 If so, productivity growth could continue to outpace real wage gains even when the economy is again operating at its potential.

A third issue that complicates the interpretation of wage trends is the possibility that, because of the dislocations of the Great Recession, transitory wage and price pressures could emerge well before maximum sustainable employment has been reached, although they would abate over time as the economy moves back toward maximum employment.[17] The argument is that workers who have suffered long-term unemployment--along with, perhaps, those who have dropped out of the labor force but would return to work in a stronger economy--face significant impediments to reemployment. In this case, further improvement in the labor market could entail stronger wage pressures for a time before maximum employment has been attained.[18]

-

Implications of Labor Market Developments for Monetary Policy

The focus of my remarks to this point has been on the functioning of the labor market and how cyclical and structural influences have complicated the task of determining the state of the economy relative to the FOMC’s objective of maximum employment. In my remaining time, I will turn to the special challenges that these difficulties in assessing the labor market pose for evaluating the appropriate stance of monetary policy.

Any discussion of appropriate monetary policy must be framed by the Federal Reserve’s dual mandate to promote maximum employment and price stability. For much of the past five years, the FOMC has been confronted with an obvious and substantial degree of slack in the labor market and significant risks of slipping into persistent below- target inflation. In such circumstances, the need for extraordinary accommodation is unambiguous, in my view.

However, with the economy getting closer to our objectives, the FOMC’s emphasis is naturally shifting to questions about the degree of remaining slack, how quickly that slack is likely to be taken up, and thereby to the question of under what conditions we should begin dialing back our extraordinary accommodation. As should be evident from my remarks so far, I believe that our assessments of the degree of slack must be based on a wide range of variables and will require difficult judgments about the cyclical and structural influences in the labor market. While these assessments have always been imprecise and subject to revision, the task has become especially challenging in the aftermath of the Great Recession, which brought nearly unprecedented cyclical dislocations and may have been associated with similarly unprecedented structural changes in the labor market--changes that have yet to be fully understood.

So, what is a monetary policymaker to do? Some have argued that, in light of the uncertainties associated with estimating labor market slack, policymakers should focus mainly on inflation developments in determining appropriate policy. To take an extreme case, if labor market slack was the dominant and predictable driver of inflation, we could largely ignore labor market indicators and look instead at the behavior of inflation to determine the extent of slack in the labor market. In present circumstances, with inflation still running below the FOMC’s 2 percent objective, such an approach would suggest that we could maintain policy accommodation until inflation is clearly moving back toward 2 percent, at which point we could also be confident that slack had diminished.

Of course, our task is not nearly so straightforward. Historically, slack has accounted for only a small portion of the fluctuations in inflation. Indeed, unusual aspects of the current recovery may have shifted the lead-lag relationship between a tightening labor market and rising inflation pressures in either direction. For example, as I discussed earlier, if downward nominal wage rigidities created a stock of pent-up wage deflation during the economic downturn, observed wage and price pressures associated with a given amount of slack or pace of reduction in slack might be unusually low for a time. If so, the first clear signs of inflation pressure could come later than usual in the progression toward maximum employment. As a result, maintaining a high degree of monetary policy accommodation until inflation pressures emerge could, in this case, unduly delay the removal of accommodation, necessitating an abrupt and potentially disruptive tightening of policy later on.

Conversely, profound dislocations in the labor market in recent years--such as depressed participation associated with worker discouragement and a still-substantial level of long-term unemployment--may cause inflation pressures to arise earlier than usual as the degree of slack in the labor market declines. However, some of the resulting wage and price pressures could subsequently ease as higher real wages draw workers back into the labor force and lower long-term unemployment.19 As a consequence, tightening monetary policy as soon as inflation moves back toward 2 percent might, in this case, prevent labor markets from recovering fully and so would not be consistent with the dual mandate.

Inferring the degree of resource utilization from real-time readings on inflation is further complicated by the familiar challenge of distinguishing transitory price changes from persistent price pressures. Indeed, the recent firming of inflation toward our

2 percent goal appears to reflect a combination of both factors.

These complexities in evaluating the relationship between slack and inflation pressures in the current recovery are illustrative of a host of issues that the FOMC will be grappling with as the recovery continues. There is no simple recipe for appropriate policy in this context, and the FOMC is particularly attentive to the need to clearly describe the policy framework we are using to meet these challenges. As the FOMC has noted in its recent policy statements, the stance of policy will be guided by our assessments of how far we are from our objectives of maximum employment and 2 percent inflation as well as our assessment of the likely pace of progress toward those objectives.

At the FOMC’s most recent meeting, the Committee judged, based on a range of labor market indicators, that “labor market conditions improved.”[20] Indeed, as I noted earlier, they have improved more rapidly than the Committee had anticipated. Nevertheless, the Committee judged that underutilization of labor resources still remains significant. Given this assessment and the Committee’s expectation that inflation will gradually move up toward its longer-run objective, the Committee reaffirmed its view:

that it likely will be appropriate to maintain the current target range for the federal funds rate for a considerable time after our current asset purchase program ends, especially if projected inflation continues to run below the Committee’s 2 percent longer-run goal, and provided that longer-term inflation expectations remain well anchored.[21]

But if progress in the labor market continues to be more rapid than anticipated by the Committee or if inflation moves up more rapidly than anticipated, resulting in faster convergence toward our dual objectives, then increases in the federal funds rate target could come sooner than the Committee currently expects and could be more rapid thereafter. Of course, if economic performance turns out to be disappointing and progress toward our goals proceeds more slowly than we expect, then the future path of interest rates likely would be more accommodative than we currently anticipate. As I have noted many times, monetary policy is not on a preset path. The Committee will be closely monitoring incoming information on the labor market and inflation in determining the appropriate stance of monetary policy.

Overall, I suspect that many of the labor market issues you will be discussing at this conference will be at the center of FOMC discussions for some time to come. I thank you in advance for the insights you will offer and encourage you to continue the important research that advances our understanding of cyclical and structural labor market issues.

[1] Nonfarm employment contracted by 6.3 percent from its peak in 2008 to its trough in early 2010, compared with a 5.2 percent loss in the 1948-49 recession, previously the largest since the 1930s.

[2] See paragraph 5 in Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System (2012), “Federal Reserve Issues FOMC Statement,” press release, December 12, http://www.federalreserve.gov/newsevents/press/monetary/20121212a.htm.

[3] See paragraph 5 in Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System (2014), “Federal Reserve Issues FOMC Statement,” press release, March 19, www.federalreserve.gov/newsevents/pre....

[4] See paragraph 5 in Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System (2012), “Federal Reserve Issues FOMC Statement of Longer-Run Goals and Policy Strategy,” press release, January 25, http://www.federalreserve.gov/newsevents/press/monetary/20120125c.htm.

[5] The central role of labor market conditions in monetary policy deliberations has also been apparent abroad. Last year the Bank of England announced its intention not to raise its policy rate at least until the unemployment rate reached 7 percent, subject to conditions on inflation and financial stability. Since that time, the unemployment rate in the United Kingdom has dropped unexpectedly rapidly, prompting policymakers to consider data beyond this single indicator when assessing the extent of spare capacity in the U.K. economy. As in the United States, an unexpectedly swift decline in unemployment has raised questions about the structural and cyclical effects of a severe recession.

[6] For a discussion of important differences in the evolution of labor market conditions during the Great Recession relative to typical postwar patterns, see Henry S. Farber (2011), “Job Loss in the Great Recession: Historical Perspective from the Displaced Workers Survey, 1984-2010,” NBER Working Paper Series 17040 (Cambridge, Mass.: National Bureau of Economic Research, May).

[7] For convenience, the analysis here is presented as if cyclical factors and structural factors can be neatly delineated. In reality, the line between the two may be indistinct. Moreover, what begins as cyclical weakness may evolve into structural damage. For a discussion of the strategic issues that arise when policymakers believe such evolution from cyclical to structural to be an important feature of the economy, see Dave Reifschneider, William Wascher, and David Wilcox (2013), “Aggregate Supply in the United States: Recent Developments and Implications for the Conduct of Monetary Policy,” Finance and Economics Discussion Series 2013-77 (Washington: Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, November), http://www.federalreserve.gov/pubs/feds/2013/201377/201377abs.html.

[8] See Shigeru Fujita (2014), “On the Causes of Declines in the Labor Force Participation Rate,” Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia, Research Rap, special report, February 6, .

[9] On disability, see Mark Duggan and Scott A. Imberman (2009), “Why Are the Disability Rolls Skyrocketing? The Contribution of Population Characteristics, Economic Conditions, and Program Generosity,” in David M. Cutler and David A. Wise, eds., Health at Older Ages: The Causes and Consequences of Declining Disability among the Elderly (Chicago: University of Chicago Press),

pp. 337-79; and David H. Autor (2011), “The Unsustainable Rise of the Disability Rolls in the United States: Causes, Consequences, and Policy Options,” NBER Working Paper Series 17697 (Cambridge, Mass.: National Bureau of Economic Research, December). For a focus on developments within the Great Recession, see David M. Cutler, Ellen Meara, and Seth Richards-Shubik (2012), “Unemployment and Disability: Evidence from the Great Recession,” NBER Retirement Research Center Paper Series NB 12-12 (Cambridge, Mass.: National Bureau of Economic Research, September). On school enrollment, see Bridget Terry Long (2013), “The Financial Crisis and College Enrollment: How Have Students and Their Families Responded?” working paper (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University, July), .

[10] For surveys of students who report job prospects as an important factor for attending or prolonging school, see John H. Pryor, Kevin Eagan, Laura Palucki Blake, Sylvia Hurtado, Jennifer Berdan, and Matthew H. Case (2012), The American Freshman: National Norms Fall 2012 (Los Angeles: Higher Education Research Institute at the University of California, Los Angeles), http://heri.ucla.edu/monographs/TheAmericanFreshman2012.pdf. On the cyclicality of college enrollment, see Andrew Barr and Sarah Turner (2013), “Down and Enrolled: An Examination of the Enrollment Response to Cyclical Trends and Job Loss,” paper presented at the PERC Applied Microeconomics workshop, held at Texas A&M University, College Station, Texas, March 20, . For research showing that the high numbers of workers seeking disability status is correlated with sectoral employment declines and demographics and not correlated with the rate of workplace injuries, see Norma B. Coe and Matthew S. Rutledge (2013), “Why Did Disability Allowance Rates Rise in the Great Recession?” Center for Retirement Research paper 13-11 (Chestnut Hill, Mass.: Center for Retirement Research at Boston College, August), ; and John Merline (2012), “The Sharp Rise in Disability Claims,” Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond, Region Focus (Second/Third Quarter), pp. 24-26, http://www.richmondfed.org/publications/research/region_focus/2012/q2-3/pdf/feature3.pdf.

[11] The effects of the Great Recession on retirements are difficult to identify. During the recession and immediately after, the losses in wealth may have put upward pressure on labor force participation; the persistently weak labor market may have subsequently contributed to more retirements and thus put downward pressure on participation. Perhaps as a result of these confounding forces, early research on the effects of the Great Recession on retirement finds unclear results. For example, see Alan L. Gustman, Thomas L. Steinmeier, and Nahid Tabatabai (2011), “How Did the Recession of 2007-2009 Affect the Wealth and Retirement of the Near Retirement Age Population in the Health and Retirement Study?” NBER Working Paper Series 17547 (Cambridge, Mass.: National Bureau of Economic Research, October). For a discussion of these developments, see Richard W. Johnson (2012), “Older Workers, Retirement, and the Great Recession” (Stanford, Calif.: Russell Sage Foundation and the Stanford Center on Poverty and Inequality, October), .

[12] See Tomaz Cajner, Dennis Mawhirter, Christopher Nekarda, and David Ratner (2014), “Why Is Involuntary Part-Time Work Elevated?” FEDS Notes (Washington: Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, April 14), ; and Murat Tasci and Jessica Ice (2014), “Job Polarization and the Great Recession,” Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland, Economic Trends (May 28), .

[13] For an analysis documenting declines in the rates of hiring, layoffs, and quits, along with lower job creation and destruction, see Steven J. Davis, R. Jason Faberman, and John Haltiwanger (2012), “Labor Market Flows in the Cross Section and over Time,” Journal of Monetary Economics, vol. 59 (January), pp. 1-18. For a review of a range of evidence and possible explanations, see Henry R. Hyatt and James R. Spletzer (2013), “The Recent Decline in Employment Dynamics,” IZA Discussion Paper Series 7231 (Bonn, Germany: Institute for the Study of Labor (IZA), February), http://ftp.iza.org/dp7231.pdf. These authors suggest that much additional work is needed to understand the role of different factors in changes in labor market dynamism. For an analysis that raises the possibility that some of these shifts reflect better job matches, see Raven Molloy, Christopher L. Smith, and Abigail K. Wozniak (2014), “Declining Migration within the U.S.: The Role of the Labor Market,” NBER Working Paper Series 20065 (Cambridge, Mass.: National Bureau of Economic Research, April).

[14] Among the indicators in the “labor market conditions index” are the labor force participation rate, workers classified as part time for economic reasons, hires, and quits. The index does not include the JOLTS job openings series but instead uses the Board staff’s composite help-wanted index, which has a longer history; the two measures generally track each other closely. See Hess Chung, Bruce Fallick, Christopher Nekarda, and David Ratner (2014), “Assessing the Change in Labor Market Conditions,” FEDS Notes (Washington: Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, May 22), . For a closely related index of labor market conditions, see Craig S. Hakkio and Jonathan L. Willis (2013), “Assessing Labor Market Conditions: The Level of Activity and the Speed of Improvement,” Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City, Macro Bulletin, July 18, http://www.frbkc.org/publicat/research/macrobulletins/mb13Hakkio-Willis0718.pdf.

[15] See Mary Daly and Bart Hobijn (2014), “Downward Nominal Wage Rigidities Bend the Phillips Curve,” Working Paper Series 2013-08 (San Francisco: Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco, January), http://www.frbsf.org/publications/economics/papers/2013/wp2013-08.pdf.

[16] For a recent study of the decline in labor’s share, see Michael W.L. Elsby, Bart Hobijn, and Aysegul Sahin (2013), “The Decline of the U.S. Labor Share,” Working Paper Series 2013-27 (San Francisco: Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco, September), http://www.frbsf.org/economic-research/files/wp2013-27.pdf. The notion that the labor share of income is a good measure of slack was prominent in the empirical literature on the New-Keynesian Phillips Curve (for example, see Jordi Galí and Mark Gertler (1999), “Inflation Dynamics: A Structural Econometric Analysis,” Journal of Monetary Economics, vol. 44 (October), pp. 195-222), and the connections (or lack thereof) between the labor share and traditional measures of slack (in the statistical sense) were highlighted in, among others, Michael T. Kiley (2007), “A Quantitative Comparison of Sticky-Price and Sticky-Information Models of Price Setting,” Journal of Money, Credit and Banking, vol. 39 (February), pp. 101-25; and Michael T. Kiley (2013), “Output Gaps,” Journal of Macroeconomics, vol. 37 (September), pp. 1-18. Moreover, recent research has highlighted the challenges that swings in the labor share have presented for the interpretation of inflation developments (for example, Marco Del Negro, Marc P. Giannoni, and Frank Schorfheide (2014), “Inflation in the Great Recession and New Keynesian Models,” NBER Working Paper Series 20055 (Cambridge, Mass.: National Bureau of Economic Research, April)).

[17] See Glenn D. Rudebusch and John C. Williams (2014), “A Wedge in the Dual Mandate: Monetary Policy and Long-Term Unemployment,” Working Paper Series 2014-14 (San Francisco: Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco, May), http://www.frbsf.org/economic-research/publications/working-papers/wp2014-14.pdf.

[18] For example, see Alan B. Krueger, Judd Cramer, and David Cho (2014), “Are the Long-Term Unemployed on the Margins of the Labor Market?” paper presented at the Brookings Panel on Economic Activity, held at the Brookings Institution, Washington, March 20-21, http://www.brookings.edu/~/media/Projects/BPEA/Spring 2014/2014a_Krueger.pdf; and Robert J. Gordon (2013), “The Phillips Curve Is Alive and Well: Inflation and the NAIRU during the Slow Recovery,” NBER Working Paper Series 19390 (Cambridge, Mass.: National Bureau of Economic Research, August). For research highlighting potential alternative interpretations, see Michael T. Kiley (2014), “An Evaluation of the Inflationary Pressure Associated with Short- and Long-Term Unemployment,” Finance and Economics Discussion Series 2014-28 (Washington: Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, March), http://www.federalreserve.gov/pubs/feds/2014/201428/201428pap.pdf; and Christopher Smith (2014), “The Effect of Labor Slack on Wages: Evidence from State-Level Relationships,” FEDS Notes (Washington: Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, June 2), .

The interaction of labor force participation and inflationary pressures has been understudied, in part because the strong trends in participation due to demographic factors have implied that it is difficult to identify the cyclical component. For an important example of a study demonstrating, within the core macroeconomic framework widely used in research, that movements in participation should be considered in models of wage and price determination, see Christopher J. Erceg and Andrew T. Levin (2013), “Labor Force Participation and Monetary Policy in the Wake of the Great Recession,” IMF Working Paper WP/13/245 (Washington: International Monetary Fund, July), http://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/wp/2013/wp13245.pdf.

[19] 19 See Rudebusch and Williams, “A Wedge in the Dual Mandate,” in note 17.

[20] See paragraph 1 of Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System (2014), “Federal Reserve Issues FOMC Statement,” press release, July 30, http://www.federalreserve.gov/newsevents/press/monetary/20140730a.htm.

[21] See paragraph 5 in Board of Governors, “FOMC Statement” (July 2014), in note 20.

Noted for Your Morning Procrastination for August 22, 2014

Over at Equitable Growth--The Equitablog

Over at Equitable Growth--The Equitablog

What I Am Going to Be Doing on August 21, 2017... - Washington Center for Equitable Growth

#FF: The Best of Daniel Davies: Friday Focus for August 22, 2014 - Washington Center for Equitable Growth

Nighttime No-Read: No List of Papers at the FRBKC Jackson Hole Conference Tonight for Me! - Washington Center for Equitable Growth

Nighttime Must-Read: Matt O'Brien: Worse than the 1930s: Europe’s Recession - Washington Center for Equitable Growth

A Note on Understanding the Debate Inside the Federal Reserve: Afternoon Comment - Washington Center for Equitable Growth

Morning Must-Read: Willem H. Buiter: The Simple Analytics of Helicopter Money: Why It Works--Always - Washington Center for Equitable Growth

Morning Must-Read: Cardiff Garcia: “The System Worked”, by Dan Drezner - Washington Center for Equitable Growth

Morning Must-Read: Alex Tabarrok: Ferguson and the Modern Debtor’s Prison - Washington Center for Equitable Growth

Nighttime Must-Read: Scott Sumner: DeLong on the Mother of All Black Swans - Washington Center for Equitable Growth

Naive Keynesianism to Keep You from Believing Macroeconomic Idiocy of Various Kinds: A Useful Graph for Jackson Hole Weekend: Thursday Focus for August 21, 2014 - Washington Center for Equitable Growth

Time to Change My Mind: The Quality of Medicare Advantage: Wednesday Focus for August 20, 2014 - Washington Center for Equitable Growth

Plus:

Things to Read on the Morning of August 22, 2014 - Washington Center for Equitable Growth

Must- and Shall-Reads:

Jesse Livermore: Fixing the Shiller CAPE: Accounting, Dividends, and the Permanently High Plateau

Mark Thoma: A Conversation with Peter Diamond

Carola Binder: Wage Inflation and Price Inflation

Matt O'Brien: Worse than the 1930s: Europe’s recession is really a depression: "As I was arguing last week, it's time to call the eurozone what it really is.... Six and a half years later, Europe has distinguished itself by not having much of a recovery at all. And, as you can see above, that's about to make it worse than the worst of the 1930s.... It's a policy-induced disaster. Too much fiscal austerity and too little monetary stimulus have crippled growth like almost never before. Europe is doing worse than Japan during its "lost decade," worse than the sterling bloc during the Great Depression, and barely better than the gold bloc then—though even that silver lining isn't much of one. That's because, at this rate, it'll only be another year until the eurozone is well behind the gold bloc, too. So how is Europe making the Great Depression look like the good old days of growth? Easy: by ignoring everything we learned from it.... The euro is the gold standard with moral authority. And that last part is the problem.... Europe is stuck with a fixed exchange system that doesn't let them print, spend, or devalue their way out of a crisis. But, unlike then, Europe might never give it up. It's a fidelity to failure that even the gold bloc couldn't have imagined. And that leaves the ECB as Europe's only hope—which means they're probably doomed.... They have made a desert, and called it the eurozone."