J. Bradford DeLong's Blog, page 1162

August 18, 2014

Liveblogging World War II: August 18, 1944: Falaise

From Richard Atkinson: The Guns at Last Light:

Napoleonic it was not. Montgomery told Brooke at eleven P.M. on August 17 that “the gap has now been closed.” That was untrue. He told Churchill, “The enemy cannot escape us.” That too was untrue. To a friend he wrote, “I have some 100,000 Germans almost surrounded in the pocket.” That was truer, but almost would not win the battle, much less the war. Fortunately, even as Allied commanders stumbled about, the reduction of the pocket by soldiers and airmen had begun in earnest. Spitfires, Typhoons, Mustangs, Lightnings, and Thunderbolts flew fifteen hundred to three thousand sorties each day in sanguinary relays from first light to last light. “Since the transports were sometimes jammed together four abreast,” an RAF group captain explained, “it made the subsequent rocket and cannon attacks a comparatively easy business.”

A captured Canadian officer who later escaped described what he had seen on August 18: “Everywhere there were vehicle trains, tanks and vehicles towing what they could. The damage was immense, and flaming transport and dead horses were left in the road while the occupants pressed on, afoot.” Canadian troops on Friday won through to Trun, subsequently described as “an inferno of incandescent ruins.” “Shoot everything,” Montgomery urged them. The next day GIs from the 359th Infantry crept into flaming Chambois, soon dubbed Shambles. An officer reported blood “running in sizeable streams in the gutters.” Fleeing Germans had been transformed into “nothing but charcoal in the forms of men” or “vertebrae attended by flies”....

Three thousand Allied guns ranged the kill zone, and an artillery battalion commander from the 90th Division told his diary: The pocket surrounding the Germans is in the shape of a bowl and from the hills our observers have a perfect view of the valley below.… Every living thing or moving vehicle is under constant observation. I can understand why our forward observers have been hysterical. There is so much to shoot at....

Two death struggles within the larger apocalypse bore on the battle. At St.-Lambert, a village straddling the river Dives between Trun and Shambles, savage counterattacks by “shouting, grey-clad men” against gutful troops from the Canadian 4th Armored Division raged through Saturday and Sunday, August 19 and 20. Pillars of fire from burning gasoline trucks smudged the heavens; corpses, carcasses, and charred equipment dammed the Dives in “an awful heap” beneath one bitterly contested bridge. “We fired till the machine gun boiled away,” a Canadian gunner reported. Improvised German battle groups shot their way through the cordon southeast of St.-Lambert, extracting not only panzers—with grenadiers clinging to the hulls “like burrs”—but also the Fifth Panzer Army command group and assorted generals, including Eberbach, who soon would be given command of Seventh Army.

Three miles northeast, eighteen hundred men from the Polish 1st Armored Division on Friday afternoon had scaled a looming scarp known as Hill 262 but which they named Maczuga—Mace—for its contours on a map. On Sunday morning, after a productive evening disemboweling a surprised German column plodding toward Vimoutiers on the road below, the Poles caught the brunt of an assault by the 2nd and 9th SS Panzer Divisions, summoned by Model from the Seine as his “break-in” force to extricate survivors from the pocket. With low clouds grounding Allied planes for part of the day, Germans swarmed up the wooded slopes “from all the sides in the world,” one Pole recalled. Panthers and Shermans traded fire point-blank as the hereditary enemies slaughtered each other with bayonets and grenades into the night and through the next morning; all the while, escaping Germans streamed past the hill mass....

Several hundred Germans with armored cars and blazing 20mm guns charged through the wheat toward Trun on Monday; a Canadian line of eight Vickers machine guns “shot them down in droves,” one soldier recorded. “It lasts a half hour or so.” The dead were picked clean of Lugers, daggers, watches, and bloody francs, spread in the sun to dry. An old Frenchman pushing a cart poked a dead German with his foot, the reporter Iris Carpenter wrote, then chortled as he urinated on the body “with the greatest care and deliberation, subjecting each feature in the gray face to equally timed proportions of debasement.” Yes, merde pour la guerre.

At last the guns fell silent, leaving the battlefield to resemble “one of those paintings of Waterloo or Borodino,” wrote Alan Moorehead, who cabled the Daily Express, “I think I see the end of Germany from here.” Distances may deceive in war, and the German demise was farther off than he and others realized. The pursuit and annihilation of a beaten foe is among the most difficult military skills to master, as demonstrated from Gettysburg to Alamein; and defeats in Russia, North Africa, and Italy had taught the Wehrmacht how to retreat. Precisely a year earlier, 110,000 Germans and Italians had escaped seemingly sure destruction at Messina. “All German formations that cross the Seine will be incapable of combat during the months to come,” Montgomery promised London. That too was optimistic, and more enemy troops crossed than should have.

Alas, no corps de chasse nipped at German heels for the forty miles from Vimoutiers to the river. After liberating Orléans and Chartres on August 16 and 18, respectively, Third Army was ordered to swing below Paris and cross the Seine east of the capital en route to the German frontier. Fuel shortages already required daily emergency airlifts from England, but Eisenhower had ordered his lieutenants to outrun the enemy as he made for home. Of Patton’s legions, only XV Corps had swiveled north, crossing the Seine on August 20 by boat, raft, treadway bridge, and a narrow footpath atop a dam near Mantes, thirty miles west of Paris. German blocking forces thwarted efforts to sweep downstream along the riverbank, but GIs managed to overrun La Roche–Guyon after firing mortars and rifle grenades into the courtyard; Model and his staff scurried off to Margival, where Rommel, Rundstedt, and Hitler had met two months earlier.

The Allied victory, though extraordinary, was incomplete.... Those who escaped the Falaise Pocket mostly escaped Normandy. Two dozen improvised ferries... shuttled 25,000 vehicles to the east bank from August 20 to 24.... British intelligence estimated that 95 percent of German troops who reached the river also made the far bank. Estimates of the number escaping the Falaise trap ranged from thirty thousand to more than a hundred thousand; those who got away included four of five corps commanders, twelve of fifteen division commanders, and many capable staff officers.... Among the dead was Marshal Kluge: en route to Berlin after his displacement by Model, he stopped outside Verdun, spread a blanket in the underbrush, and swallowed a cyanide capsule. “When you receive these lines, I shall be no more,” he told Hitler in a valedictory note. “The German people have suffered so unspeakably that it is time to bring the horror to a close.” The Führer composed his epitaph: “Perhaps he couldn’t see any way out.… It’s like a western thriller.”

Allied investigators counted nearly seven hundred tanks and self-propelled guns wrecked or abandoned from Falaise to the river. No Seine ferry could carry a Tiger, and panzers stood scuttled and charred on the docks at Rouen and elsewhere. The tally also included a thousand artillery pieces and twenty-five hundred trucks and cars. Model told Hitler that his panzer and panzer grenadier divisions averaged “five to ten tanks each.” Divisions in the Fifth Panzer Army averaged only three thousand men, with barely one-third of their equipment. Army Group B had been demolished, complementing the destruction of Army Group Center in White Russia in June, although many divisions would display a knack for resurrection....

Norman schoolchildren sang in English to Canadian soldiers, “Thank you for liberating us.” The U.S. stock market tumbled in anticipation of peace and falling corporate profits. Reports from southern France suggested that a Franco-American invasion on the Mediterranean coast had pushed the enemy back on his heels. Many recalled November 1918, when the German army had abruptly disintegrated. “It is,” Montgomery declared, “the beginning of the end of the war.” That much was true...

August 17, 2014

Liveblogging World War I: August 17, 1914: Belgium and Lorraine

From Barbara Tuchman: The Guns of August:

On August 16 OHL, which had remained in Berlin until the end of the concentration period, moved to Coblenz on the Rhine some eighty miles behind the center of the German front. Here Schlieffen had envisaged a Commander in Chief who would be no Napoleon on a white horse watching the battle from a hill but a “modern Alexander” who would direct it “from a house with roomy offices where telegraph, telephone and wireless signalling apparatus are at hand while a fleet of autos and motorcycles ready to depart, wait for orders. Here in a comfortable chair by a large table the modern commander overlooks the whole battlefield on a map. From here he telephones inspiring words and here he receives the reports from army and corps commanders and from balloons and dirigibles which observe the enemy’s movements.”

Reality marred this happy picture. The modern Alexander turned out to be Moltke who by his own admission had never recovered from his harrowing experience with the Kaiser on the first night of war. The “inspiring words” he was supposed to telephone to commanders were never part of his equipment and even if they had been would have been lost in transmission. Nothing caused the Germans more trouble, where they were operating in hostile territory, than communications. Belgians cut telephone and telegraph wires; the powerful Eiffel Tower wireless station jammed the air waves so that messages came through so garbled they had to be repeated three or four times before sense could be made of them. OHL’s single receiving station became so clogged that messages took from eight to twelve hours to get through. This was one of the “frictions” the German General Staff, misled by the ease of communications in war games, had not planned for.

The wickedly unobliging resistance of the Belgians and visions of the Russian “steam roller crashing through East Prussia further harassed OHL. Friction developed in the Staff. The cult of arrogance practiced by Prussian officers affected no one more painfully than themselves and their allies. General von Stein, Deputy Chief of Staff, though admittedly intelligent, conscientious, and hard-working, was described by the Austrian liaison officer at OHL as rude, tactless, disputatious, and given to the sneering, domineering manner known as the “Berlin Guards’ tone.” Colonel Bauer of the Operations Section hated his chief, Colonel Tappen, for his “biting tone” and “odious manner” toward subordinates. Officers complained because Moltke refused to allow champagne at mess and because fare at the Kaiser’s table was so meager it had to be supplemented with private sandwiches after dinner.

From the moment the French attack began in Lorraine, Moltke’s resolve to carry through Schlieffen’s total reliance upon the right wing began to slip. He and his staff expected the French to bring up their main forces on their left to meet the threat of the German right wing. As anxiously as Lanrezac sent out scouts looking for the British, OHL looked for evidence of strong French movements west of the Meuse, and up to August 17 found none. That vexing problem of war presented by the refusal of the enemy to behave as expected in his own best interest beset them. They concluded from the movement in Lorraine and the lack of movement on the west that the French were concentrating their main force for an offensive through Lorraine between Metz and the Vosges. They asked themselves if this did not require a readjustment of German strategy. If this were the main French attack could not the Germans, by a shift of forces to their own left wing, bring about a decisive battle in Lorraine before the right wing could accomplish it by envelopment? Could they not in fact accomplish a true Cannae, the double envelopment that Schlieffen had held in the back of his mind?

Anxious discussions of this alluring prospect and even some preliminary shifting of the weight of gravity toward the left engaged OHL from August 14 to 17. On that date they decided that the French were not massing in Lorraine to the extent believed and reverted to the original Schlieffen plan. But once divinity of doctrine has been questioned there is no return to perfect faith. From then on, OHL was lured by opportunity on the left wing. Mentally, Moltke had opened his mind to an alternative strategy dependent on what the enemy would do. The passionate simplicity of Schlieffen’s design for total effort by one wing and rigid cleaving to plan regardless of enemy movements was broken. The plan that had appeared so faultless on paper cracked under pressure of the uncertainties, above all the emotions, of war.

Having deprived himself of the comfort of a prearranged strategy, Moltke was thereafter tormented by indecisiveness whenever a decision was required. On August 16 Prince Rupprecht required one urgently. He wanted permission to counterattack. His headquarters at Saint-Avold, a dreary, undistinguished town sunk in a hollow on the edge of the dingy mining district of the Saar, offered no princely amenities, no château for his lodging, not even a Grand Hotel. Westward stretched before him a land of easy rolling hills under wide open skies with no obstacles of importance before the Moselle, and, glowing on the horizon, the prize—Nancy, jewel of Lorraine. Rupprecht argued that his given task to engage as many French troops as possible on his front could best be accomplished by attacking, a theory exactly contrary to the strategy of the “sack.”

For three days, from August 16 to 18, discussion raged over the telephone wire, happily all in German territory, between Rupprecht’s headquarters and General Headquarters. Was the present French attack their main effort? They appeared to be doing nothing “serious” in Alsace or west of the Meuse. What did this indicate? Suppose the French refused to come forward and fall into the “sack”? Suppose Rupprecht continued to retire, would not a gap be opened up between him and the Fifth Army, his neighbor to the right, and would not the French attack through there? Might this not bring defeat to the right wing?

Rupprecht and his Chief of Staff, General Krafft von Dellmensingen, contended that it would. They said their troops were impatiently awaiting the order to attack, that it was difficult to restrain them, that it would be shameful to force retreat upon troops “champing to go forward”; moreover, it was unwise to give up territory in Lorraine at the very outset of the war, even temporarily, unless absolutely forced to. Fascinated yet frightened, OHL could not decide....

[French's] next visit was to Lanrezac. The taut temper at Fifth Army Headquarters appeared in Hély d’Oissel’s first greeting to Huguet when he drove up in a car with the long-sought British officers, on the morning of August 17: “At last you’re here. It’s not a moment too soon. If we are beaten, we’ll owe it to you.” General Lanrezac appeared on the steps to greet his visitors whose appearance in the flesh did not dispel lingering suspicions that he was being tricked by officers without divisions. Nothing said in the ensuing half-hour did much to reassure him. Speaking no English and his vis-à-vis no useful French, the two generals retired to confer alone without interpreters, a procedure of such dubious value that to explain it as done out of a mania for secrecy, as suggested by Lieutenant Spears, seems hardly adequate.

They emerged shortly to join their staffs, of whom several were bilingual, in the Operations Room. Sir John French peered at the map, put on his glasses, pointed to a spot on the Meuse, and attempted to ask in French whether General Lanrezac thought the Germans would cross the river at that point which bore the virtually unpronounceable name Huy. As the bridge at Huy was the only one between Liège and Namur and as von Bülow’s troops were crossing it as he spoke, Sir John French’s question was correct if superfluous. He stumbled first over the phrase “cross the river” and had to be prompted by Henry Wilson who supplied “traverser le fleuve,” but when he came to “à Huy,” he faltered again. “What does he say? What does he say?” Lanrezac was asking restively. “… à Hoy,” Sir John French finally managed to bring out, pronouncing it as if he were hailing a ship.

It was explained to Lanrezac that the British Commander in Chief wished to know if he thought the Germans would cross the Meuse at Huy. “Tell the Marshal,” replied Lanrezac, “I think the Germans have come to the Meuse to fish.” His tone, which he might have applied to some particularly dimwitted question at one of his famous lectures, was not one customarily used toward the Field Marshal of a friendly army.

“What does he say? What does he say?” Sir John French, catching the tone if not the meaning, asked in his turn. “He says they are going to cross the river, sir,” Wilson answered smoothly.

In the mood engendered by this exchange, misunderstandings flourished. Billets and lines of communication, an inevitable source of friction between neighboring armies, produced the first one. There was a more serious misunderstanding about the use of cavalry, each commander wanting the use of the other’s for strategic reconnaissance. Sordet’s tired and half-shoeless corps which Joffre had assigned to Lanrezac had just been pulled away again on a mission to make contact with the Belgians north of the Sambre in the hope of persuading them not to retreat to Antwerp. Lanrezac was in dire need—as were the British—of information about the enemy’s units and line of march. He wanted use of the fresh British cavalry division. Sir John French refused it. Having come to France with only four divisions instead of six, he wished to hold the cavalry back temporarily as reserve. Lanrezac understood him to say he intended employing it as mounted infantry in the line, a contemptible form of activity which the hero of Kimberley would as soon have used as a dry-fly fisherman would use live bait...

Weekend Reading: Josh Brown and Jeff Macke: Joe Granville: The Man Who Moved Markets

From Josh Brown and Jeff Macke: Clash of the Financial Pundits:

From Josh Brown and Jeff Macke: Clash of the Financial Pundits:

Josh Brown and Jeff Macke: Chapter 7: The Man Who Moved Markets: "'There are clear lines separating those who swear by him and those who swear at him.' —LOUIS RUKEYSER ON JOE GRANVILLE...

...It is late in the evening on January 6, 1981, and telephones all over the country are starting to ring. Thirty employees of a Florida-based stock market newsletter business are making out-going calls to deliver a very simple, yet ominous, message to a few thousand subscribers across the nation:

This is a Granville Early Warning. Sell everything. Market top has been reached. Go short on stocks having sharpest advances since April. Click.

Early the next morning, just after the opening bell of trade rings on the New York Stock Exchange, the market gaps lower and sell orders continue to flood into the trading floor. The Dow drops a total of 24 points that day, or 2.5 percent, on historic volume of more than 93 million shares traded, more than double the daily average. The Dow then proceeds to drop another 1.5 percent the next day; a five-week sell-off is soon under way. Traders and business news reporters are pointing toward Joe Granville to explain the sudden, sharp drop in the stock market, and Granville is more than happy to be pointed at.

He tells a news camera from behind his desk in a Daytona Beach suburb that “the market told me, ‘Sell.’ And we do what the market tells us to; we never hedge. Only losers hedge.” Granville’s controversial “Sell everything” call had made instant history, and the debate over prescience versus self-fulfilling prophecy would rage as the losses of the week were tabulated all over America.

It was not the first time that “Calamity Joe” had influenced the price and direction of the market. On April 22, 1980, Granville told his subscribers that he was switching from short to long. Within hours, the Dow had rallied by more than 30 points, an intraday jump of over 4 percent for the U.S. stock market on no other news besides Joe’s bullishness.

To market observers of the time, it was both mystifying and terrifying—the age of the market-moving pundit had officially begun.

How was it possible that one “expert” out of so many could have this much power over the entire U.S. stock market—enough clout to literally will crashes and rallies into being with a few words? It certainly wasn’t the length of his track record, as Granville’s buy and sell calls had performed terribly throughout the secular bear market of the late 1960s and 1970s. Nor could it have been the size of his audience; he had just a thousand or so paying subscribers in the early days, nowhere near the 90,000 people receiving the Value Line Investment Survey or the Merrill Lynch Market Letter.

No, what Joe Granville had lacked in breadth and depth, he made up for with sheer personality and moxie. He had figured out the secret of all punditry, market or otherwise: certitude.

Granville had made a name for himself and rose above the legions of goldbug letters from would-be stock wizards by saying exactly what he thought at the top of his lungs. There was no hesitation and no waffling. He derided Wall Street’s traditional securities analysts as “bag holders” and referred to the Wall Street Journal as “The Bagholders’ News.” His nickname for Louis Rukeyser was “Crab Louie,” and he referred to Alan Greenspan as a “bespectacled prune.” In contrast to the buy-and-hold “losers,” Joe Granville gave subscribers specific instructions to go 100 percent long stocks or sell the market short with all their money. This was certitude writ large; he frequently made predictions for market moves greater than 10 percent in either direction.

The secret to Joe’s influence and rapid rise to the top of market punditry was the absolute resolution with which he foretold the future. It should come as no surprise that he was able to attract such a large following because people have been shown to prefer commentators with unwavering confidence over those who are more reserved and have actually gotten things right. The research shows that in the presence of someone speaking emphatically about events to come, people subconsciously shut off the part of their brain that reminds them this cannot actually be done.

So strong is our desire to know what’s coming, that a newsletter writer from Florida could come along and rock the New York Stock Exchange with a midnight phone call.

In the Spring 1982 issue of the Journal of Portfolio Management, the legendary early quantitative analyst Edward Thorpe posed the question, “Can Joe Granville Time the Market?” He then sought to answer it with two other analysts and a stack of Granville’s newsletters along with his full cooperation.

For Granville, this was a chance to test his intuition and skill at reading his 18 key market indicators, which had become the financial version of Colonel Sander’s secret blend of 11 herbs and spices. Could the Granville edge actually be verified and quantified? If it could, just imagine how much he could charge for his advisory service with actual scientific proof! And if the study could not con- clusively prove his timing ability, well, who the hell was going to read the Journal of Portfolio Management anyway?

Thorpe and the study’s coauthors met with Granville to discuss his indicators and methods. They then got to work testing Granville’s calls from the mid-1970s through the end of 1981.

Using “hypergeometric probability distributions” along with many other algebraic equations and ratios, the quants made a startling discovery—they simply could not dismiss Granville’s timing abilities out of hand (even though they go through great pains not to confirm them either).

Granville selected 446 of the 719 market days as up. If his predictions are better than chance, we would expect him to have a higher percentage of up days in his chosen set of 446 “up” days. In fact 57 percent of the days he called “up” actually were up. This is about 23 more than the number expected by chance. Is it significant? Given the number of up and down days in the period as a whole, it seems very unlikely that Granville’s “buy” periods would have contained so many up days by chance.

The authors of the study concluded that, while Granville may have had a small statistical edge on his Dow Jones buy and sell calls, some of the indicators he claimed to use could be shown to have no real predictive power. Further, they informed us that most of the stocks his newsletter included as specific buy and/or short-sell candidates had done much worse than the market. Last, we are reminded by the study that Granville had made many other predictions, such as the specific time and date of an earthquake in California, that never happened.

Regarding the earthquake prediction, Thorpe was not exaggerating. In the spring of 1981, Joe Granville was at the tail end of a three-hour appearance in front of a ballroom full of investors in Vancouver. He told the crowd that on April 10 the fault lines 23 miles east of Los Angeles would shear the state of California in half. He was said to have repeated this prediction at another event that week, warning that Phoenix, Arizona, was soon to become “beachfront property.” Joe delivered these jeremiads with immense conviction. “I follow 33 earthquake indicators. If you knew what I knew, you couldn’t keep quiet.”

Of course, no such thing ended up occurring, but Joe was making so many predictions about so many things at this point that it almost didn’t matter.

Thanks to his big sell call in January 1981, his fame as a Nostradamus of the markets had swelled the ranks of his newsletter subscription base and turned his speaking appearances into standing room–only events everywhere he went. Estimates put his annual income during this time at more than $6 million—the equivalent of $16 million in today’s dollars, about what a star NFL quarterback makes. Granville’s company was taking in $250 per year for each of his 20,000 newsletter subscribers and another $500 apiece for the roughly 3,000 subscribers to his telephone “early warning system” that had so notoriously tanked the market at the beginning of the year. There were cassette tapes for sale with trading lessons on them, and Granville claimed that each public appearance he made during his 150,000-miles-per-year trek could make his firm up to $100,000 in fees and new sign-ups.

His appearances and events were becoming a cross between the circus coming to town and a revival show tent complete with feats and miracles. The more outrageous Granville’s antics and observations, the more people were willing to pay for them. Professor Robert Shiller describes these increasingly wacky shenanigans in his book Irrational Exuberance:

Granville’s behavior easily attracted public attention. His investment seminars were bizarre extravaganzas, sometimes featuring a trained chimpanzee who could play Granville’s theme song, “The Bagholder’s Blues,” on a piano. He once showed up at an investment seminar dressed as Moses, wearing a crown and carrying tablets. Granville made extravagant claims for his forecasting ability. He said he could forecast earthquakes and once claimed to have predicted six of the past seven major world quakes. He was quoted by TIME magazine as saying, “I don’t think that I will ever make a serious mistake in the stock market for the rest of my life,” and he predicted he would win the Nobel Prize in economics.

With his eldest son, Blanchard, managing the newsletter firm day to day and fleshing out dad’s utterances with legitimate technical analysis for the weekly missives, Joe Granville was free to run from one end of the country to the other with his exciting hybrid of market commentary and showmanship. Brokerage firms would set up and sponsor events for their customers, and Granville would show up and blow the roof off the place.

Kristin McMurran had profiled the market seer for People Magazine that year and made note of some of his more outrageous entrances. In Alaska he showed up for a speaking engagement driving a dogsled. In Tucson he walked across a swimming pool on a camouflaged board and then deadpanned to the crowd, “Now you know.” There were high-wire flying entrances, tuxedos with blinking-light bowties, exploding hand grenades, child singing sensations, animal sidekicks, and all other manner of costumes and contraptions. Granville once emerged from a coffin to let an audience know that the bull market was dead.

Off the stage, he was every bit as wild as he was during his day job. McMurran’s article captured the man behind the market prognostication:

In conversation, Granville is a fountain of dates, facts and figures. Every other sentence is punctuated with “boom”—as in “Truth is Truth. Boom.” Though he has lately become wealthy, he still spends seven and a half months a year on the road, bunking in hotels and living out of a tattered suitcase. Separated from his second wife since 1971—their divorce became final last year—he chain-smokes Marlboros, tosses back Margaritas, and disco-dances until dawn. In the company of old or new pals, he unwinds by playing poker or trading purple jokes. With women, whom he often calls “Frisbees,” he is forever playing the ladies’ man. At a restaurant, he may greet a waitress by chortling expansively, “Do you know who I am, honey?” She rarely does, but often delivers her phone number with his brandy. Says Joe: “Women are interested in men who can make them rich. Boom.”

It is important to remember that the ascendancy was taking place after 15 years of moribund stock returns and right around the time that BusinessWeek had famously declared “The Death of Equities” on its now infamous August 1979 cover. A brutal bear market had worn out a generation of investors since the market’s 1966 peak, accompanied by stagflation, the loss of the Vietnam War, the troubled Nixon and Ford administrations, and the assassination of John Lennon. By 1981, the financial markets needed a hero, someone who could bring humor and a sense of adventure back to the game. Joe Granville’s provocative persona was just what the doctor had ordered. While the Wall Street establishment despised him, the public ate it up.

A brilliant and all-but-forgotten analyst named James Alphier took it upon himself to analyze the great market timers throughout history, and he called his 1981 paper “Granville in Perspective.” Alphier dissected the records of the so-called Forecasting Giants of the Past to see whether or not any market analyst could consistently maintain forecasting accuracy over extended periods of time. He began with a question: “How often has an analyst, whose research is publicly available, been able to do something like this in the past?”

The so-called giants in Alphier’s paper included George Lindsay, whose “repeating time interval” work was able to produce a decade’s worth of top and bottom calls, complete with specific dates and price levels. Alphier analyzed 30 years’ worth of accurate bull and bear market calls from Edson Gould, who had been calling the beginnings and ends of major market trends with shocking accuracy since the early 1950s. Alphier also reconstructed the unparalleled predictive work of Major L.L.B. Angus, who had correctly forecast the market’s 1920s boom, its peak in 1929, and its low in 1932.

Alphier’s conclusion upon studying these giants as well as a great many pretenders was that with only a handful of exceptions, great timers could only remain accurate for a run of between three and five years. He notes:

For periods of as little as four years, there have been many analysts who have been able to (1) forecast the major market averages, (2) nearly coincide with the extreme high or low, and (3) do this on the significant swings. In these, and most other cases we could cite, there is a tendency after three to five years of near perfect forecasting for the analyst to make one or more major errors. We will not recount the many painful examples of this in our files.

The bad news for Joe Granville was that, by the time Alphier’s 1981 paper was published, his massive winning streak was already passing through the midpoint of this three- to five-year time frame that had begun with a bull call at the market’s low in 1978.

Following his amazing run of nailing all four major market turns through the first quarter of 1981, Granville’s track record had begun to suffer. Whether it was hubris that had done him in or too much time spent teaching the chimp to play his theme song on piano, one thing was clear: the magician was losing his touch.

The U.S. stock market would hit its final low for the 16-year secular bear market cycle in August 1982. Then–Federal Reserve chairman Paul Volcker had finally tamed inflation (running at a rate of 7 percent that year but dropping), and stocks were selling at a highly depressed price-earnings ratio of under 10. Unemployment had peaked, as had apathy toward investing, and all of a sudden, the market had just taken off. Joe Granville, whose novelty and fame had been partly responsible for the public’s renewed attention to stocks, had ironically missed the effect he was having on the markets. People were coming back to the game, and a major rally was under way.

“Sell it short” was what Granville’s letter had been saying all summer, and the rally hadn’t shaken him from his position. By this time, his tens of thousands of subscribers and acolytes had been getting pummeled by the relentless tape as they were either miss- ing the move or, worse, actively betting against it.

By the fall of 1982, the stock market had staged one of its most explosive rallies of all time. From the lows of August through November, the Dow Jones Industrial Average had advanced by more than 275 points, or 35 percent, to a new 10-year high. For the bears, this new change in character was excruciatingly painful. It was the beginning of a new secular bull market, but many market timers, analysts, and economists were simply unprepared for it.

As for Joe Granville, he was off the lecture circuit and had been steadily reducing his public profile all year. The home office was telling reporters that he was quietly working on a new book at his home in Kansas City. Granville’s adamantly bearish stance had cost his remaining 13,000 subscribers a fortune, and the stockbrokers across the country who had been running their clients’ money based on his forecasts were either despondent or furious.

During his win streak, Granville had been relentlessly disdainful of Wall Street and the brokerage industry, calling them losers, thieves, and idiots at every opportunity. And now it was Wall Street’s turn to respond in kind.

The schadenfreude was thick in an October wire story by the Los Angeles Times that had been picked up by newspapers all over America. Under the headline “Tarnished Idol,” Granville’s losing record for the year had been laid bare, accompanied by quotes from the era’s most prominent market watchers. Ned Davis, a fellow technical analyst whose research firm was also based in Florida, told the paper that “I think his basic system is sound, but I don’t care what kind of system you build, it’s going to fail sooner or later. I think [Granville’s problem] has to do with ego. He says he listens to the market. Truthfully, I think he thinks he’s smarter than the market.” As to the chances of a Granville comeback, Davis wasn’t optimistic. “No brokerage is going to sponsor a guy who has been bearish for 18 months.”

Famed analyst Larry Wachtel was equally critical of both Granville and his subscribers, saying, “I don’t see really how he can crawl out of this. The lesson for those getting crucified on the short side is don’t follow anybody without thinking things through yourself.”

The Dow Theory Letter’s Richard Russell summed it up nicely, saying, “The moral of the whole thing is there are no geniuses on Wall Street. There are just people who are excellent for a while.”

To echo the closing coda to Billy Joel’s “Miami 2017,” in the case of Joe Granville, there are not many who remember. The majority of Granville’s newsletters have not made it onto the web, and in the 1970s and 1980s, we didn’t quite have the wall-to-wall coverage of the markets that we do today. But what is clear from the archival magazine stories and newspaper articles of that era is that the man who once moved the markets with his predictions would never recover from missing the flop from bear market to bull. The markets would rise relentlessly for the next 18 years with only sporadic corrections that were swiftly dispatched by the stock-hungry hordes. Even the crash of 1987, a jarring event at the time, hardly shows up on a monthly chart of the 1982–2000 bull market, and once inflation settled down for good under Clinton, multiples began expanding more rapidly.

In this context, no one had much use for market timers or perma-bears calling tops. Every dip was a buying opportunity, and guys like Granville were occasionally ridiculed but mostly ignored.

Granville would surface in the popular press occasionally in the three decades since his heyday, and the success rate of his predictions was as inconsistent as ever it had been. In May 2002 he told BusinessWeek that the market’s top was in as of March. When asked by the reporter what investors should do, Granville replied:

They should be short. All my people are short, betting on the downside. My last call was when I gave a bear selling signal right on Mar. 19, at 10,635 in the Dow. The outlook is getting increasingly worse. When I look at the market as a whole, I look at it as an army, with the generals and the troops. And it’s very, very disturbing to the troops when you see a number of key stocks—the generals—such as General Electric, IBM and Merrill Lynch leaving the line and retreating. On top of that, smart people have been leaving the market all this year.

Now, of course, March 2002 turned out to have been the very end of the bear market that had begun with the tech bust; stocks would go on an uninterrupted tear for the next five years from that interview. And while Granville was correctly bullish about the prospects for gold beginning a new bull market, he was wrongly bearish on U.S. stocks and particularly tech stocks, which would go on to stage a tremendous recovery from then.

Ten years later, at age 89, Joe Granville would make headlines again. This time, he makes a January 2012 appearance on Bloomberg Television in which he predicts a 4,000-point crash for the Dow Jones to occur at some point during 2012. No such thing happens. The Dow Jones Industrial Average ends up logging its fourth straight positive year in 2012, a gain of almost 900 points, or 7 percent, with virtually zero volatility to speak of.

Mark Hulbert, a MarketWatch columnist, has been tracking newsletter recommendations since 1980. In 2005, he took a look back and assembled a ranking of all the newsletter prophets he’d been following. According to Hulbert’s analysis, Granville’s letter was at the bottom of the rankings for performance over the past 25 years, “having produced average losses of more than 20 percent per year on an annualized basis.”

On September 7, 2013, Joe Granville passed away at Saint Luke’s Hospice House in Kansas City, Missouri; his third wife, Karen, was by his side. He was 90 years old and had, by then, really and truly seen it all.

Several generations of oracles and wizards have come and gone since those early days of crash calls and faxed financial bom- bast. Very few of those who have followed in Granville’s footsteps have been able to attain his level of market-moving influence or headline-grabbing flamboyance. All of them have eventually failed to hang on to their temporary relevance.

Joe Granville’s failure to accurately forecast securities prices is not a personal failing of his—it speaks to the inability of any sys- tem or human being (or combination thereof) to do this kind of thing with any meaningful consistency. Markets are, as Michael Mauboussin notes in his book The Success Equation, “a complex adaptive system” being acted upon by millions of individuals who do not behave according to any predetermined set of rationales or rules. This plain and simple fact is what condemns all market tim- ers to inevitable failure, regardless of the depth of their experience or the calibration of their indicators.

And when elaborate stage shows and a rock star mentality begin to enter into the equation, you can pretty much hang up your spurs right then and there.

Because that’s when the ride is over.

Under What Circumstances Should You Worry That the Stock Market Is "too High"?: The Honest Broker for the Week of August 16, 2014

Over at Equitable Growth: Robert Shiller: The Mystery of Lofty Stock Market Elevations: "The CAPE ratio, a stock-price measure I helped develop...

...is hovering at a worrisome level.... Above 25, a level that has been surpassed... in only... the years clustered around 1929, 1999 and 2007. Major market drops followed those peaks.... We should recognize that we are in an unusual period, and that it’s time to ask some serious questions about it...

The first question I think we should ask is: how damaging in the long run to investor portfolios were the major market drops that followed the 1929, 1999, and 2007 CAPE peaks? The CAPE is the current price of the S&P index divided by a ten-year trailing moving average of its earnings: the CAPE looks back ten years to try to get an estimate of what normal earnings are and how stock prices deviate from them. Let's look ahead and calculate ten-year forward earnings to get a sense of what signals the CAPE sends for those of us interested in stocks for the long run.

When we do that, we find that we cannot calculate a ten-year return for the 2007 CAPE peak of 27.54--we still have three years to go. But over the past seven years the S&P has produced an average annual real return of 5.2%/year: not too shabby. The ten-year average real return from the 1929 peak of 32.56 was 3.3%/year: you were in a real world of hurt if you panicked and sold or had to sell in 1931-1934, but not if you hung on. Only the 1999 peak was followed by long-run return disaster: a ten-year average real return of -2.1%/year because you would have been selling at the bottom in 2009--but even then if you had hung on until today your average 14.5 year real return would be +2.7%/year.

If you are not an investor in the stock market for the long term, you can easily get into a world of hurt with a position in the S&P composite (and an even bigger world of hurt with an undiversified portfolio). Look at the one-month and one-year return distributions:

You can lose a fifth of your money in a month. You can lose more than half your money in a year. And you can do those things as well with a CAPE of 15 as with a CAPE of 40. If you are not in stocks for the long term, your stock portfolio should not consist of money that you cannot afford to lose.

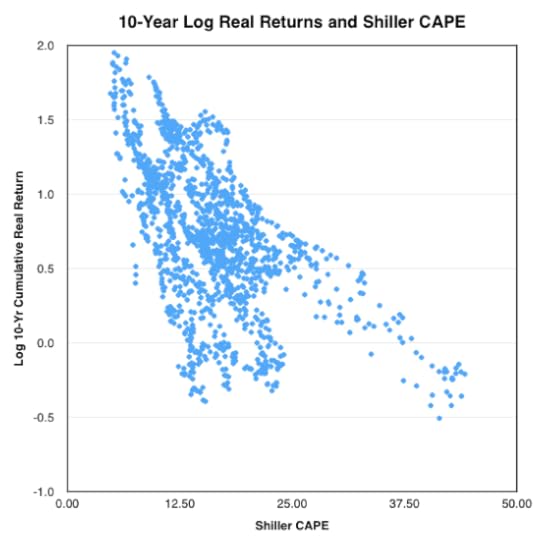

But if you are in stocks for the long term? How big are the risks, really, and how do they correlate with the Campbell-Shiller CAPE? I like to start thinking about this by plotting the full distribution for every month from 1881 to mid2004, the last month for which we can calculate a full ten-year real return:

The left axis shows the cumulative ten-year log return: a value of 0.69 means that you have doubled your real money; a value of 1.4 that you have quadrupled your real money; and if there were a value of 2.1 there you would have octupled your real money. The S&P has never done this. But it came very close in the ten years starting in 1920.

An extremely naive take would be to assume the efficient market hypothesis: that the marginal trader and the marginal firm know what they are doing, and that the margin the earnings of the companies in the index are equally valuable if paid out or if reinvested. In that case we would expect the real return--the dividend yield plus capital gains--to be simply equal to the earnings yield. The warranted ten-year return would then be simply 10 times the permanent earning power. And if we take the moving average of earnings underlying the CAPE to be our estimate of the permanent earning power, the warranted return is simply 100 divided by the CAPE, like so:

Given the naiveté of the framework, that turns out to be not at all a bad guide to the central tendency of the distribution of future ten-year returns conditional on the CAPE. If you are going to project an expected value for an investment in the S&P over the next ten years, simply inverting the CAPE and multiplying by 10 is a very good place to start. But even at the ten-year return horizon the variability is enormous: earnings 10 years hence may be well above their current value compounded forward at the current earnings yield; but they may be well below as well; the earnings valuation multiple 10 years hence may have jumped up; or it may have crashed. The only places in the distribution where the naïve warranted return does not seem to capture the central tendency is where the CAPE was very low or very high. But we know that when the CAPE was very low there were no subsequent large downward reductions in the valuation multiple: that's what it means when we look back and say "oh, then the CAPE was very low". And we know that when the CAPE was very high there were no subsequent large upward leaps in the valuation multiple: that's what it means when we look back and say "oh, then the CAPE was very high".

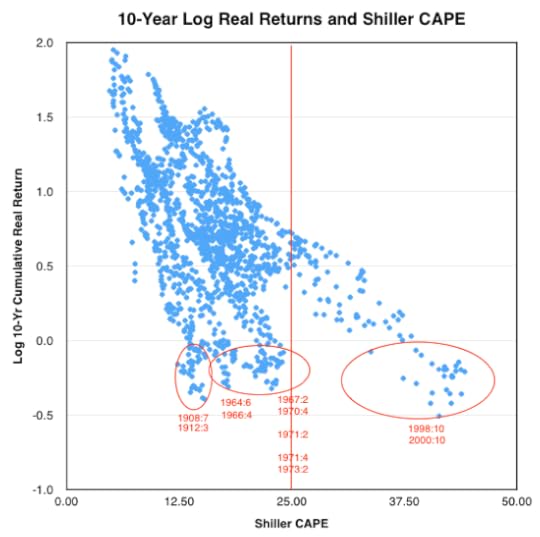

The entire spread of the time series has something to tell us about expected returns and the variation around them. What does it say about the risk of loss--the possibility that we sock our money in the stock market and reinvest it for 10 years, but when we come to take it out it is not there or it is not all there? A few points:

Risk relative to what? Trying to move purchasing power from the present into the future is a hazardous activity. War and rumors of war; inflation and rumors of inflation; depression and rumors of depression; Bernie Madoffs and rumors of Bernie Madoffs; coups, confiscations, and heavy capital taxation--risks cannot be avoided but only managed and balanced off against one another.

That said, almost always ten-year returns on the S&P have been a winner.

And on average, at a ten-year horizon, for any CAPE ratio below 35 the S&P has delivered average real asset returns pretty much outclassing all other major asset classes.

There are only three historical periods during which a ten-year investment in the S&P has not at least held its real value: 1908:7-1912:3, 1964:6-1973:2, and 1998:10-2000:10--ten years before the post-World War I deflation and depression of the start of the 1920s, 10 years before the stagflation of the 1970s and the subsequent Volcker depression, and 10 years before the recent financial unpleasantness:

The outbreak of World War I and its consequences was the original Black Swan. Those who were trying to shed stock market risk around 1910 by purchasing bonds of any sort found themselves much more exposed to and damaged by the inflationary component of the World War I shock. And if you could hang on to your equity portfolio after 10 years and go double or nothing for the next decade you captured in the near-octupling which was the greatest bull market in history. And, of course, the CAPE was not notably high but rather below average as this first episode commenced.

From the early 1970s through the early 1980s the economy was hit not by a black swan but by a bunch of ugly ducklings: politicians (cough, Richard Nixon) with an excessive focus on their own reelection and Federal Reserve chairs (cough, Arthur Burns) who appear to have forgotten that they were and were supposed to be independent of both the president who appointed them and the congress that oversaw them; oil shocks; productivity slowdowns; and, ultimately, the failure to figure out any way to end stagflation and re-anchor inflation expectations at a low level other than repeatedly hitting the economy on the head with a high interest-rate brick until it collapsed. But, once again, those who were trying to shed stock market risk by purchasing bonds of any sort found themselves much more exposed to and damaged by the inflationary component of the 1970s shocks. And, of course, the CAPE was high but not notably and anomalously high as this second episode commenced.

As noted above, the first time the CAPE crossed 25 heading upward was during the last stages of the Roaring Twenties bull market that preceded the Great Depression. And--provided you held on for the full ten years--you did OK: cumulative returns were not that far from what you would have expected if you had simply inverted the CAPE and multiplied it by 10. And the same for the second time the CAPE crossed 25 heading upwards, in the years after Greenspan's "irrational exuberance" speech.

Only those who invested at the peak of the dot-com bubble which just happened to come ten years before the crash that inaugurated the Great Recession fared badly in the sense of losing any substantial component of their real wealth. Here, moreover, investing in not risky but safe bonds would have protected you: there was no inflation component to the shocks that caused the Great Recession.

Thus you can see why I am relatively unsatisfied with Shiller's writing:

In the last century, the CAPE has fluctuated greatly, yet it has consistently reverted to its historical mean--sometimes taking a while to do so. Periods of high valuation have tended to be followed eventually by stock-price declines. Still, the ratio has been a very imprecise timing indicator.... The ratio is saying the stock market has been relatively expensive for years. And that raises a question: Are there legitimate factors behind high stock prices that might keep them elevated for decades more? Such a question has been addressed before. In 1930, just after the 1929 crash, Prof. Irving Fisher of Yale published “The Stock Market Crash — and After.” The book explained why there were “sound reasons” for the high valuations of 1929. He couldn’t have been more wrong...

Shiller's rhetoric leads us to focus on graphs like this one of the Campbell-Shiller CAPE, and to think that what goes up must--someday--come down:

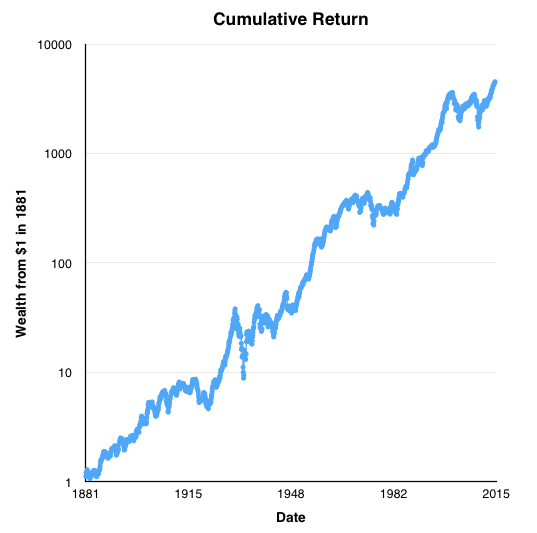

But is there any reason to think that the central tendency of the CAPE today is the same as what it was in the 1880s or the 1950s? There is no unchanging machine buried in the earth for the past 120 years throwing dice to determine the CAPE. It would be much better to say that extreme values of the CAPE are followed by reversion not to but toward the previous historical mean. And dividends and earnings shift too. A much better graph than the CAPE graph is the cumulative reinvested return graph:

And on a log scale:

It goes way up, and way down, but the dominant feature is not mean reversion but rather exponential growth. Think: 3.5 tenfold upward leaps in four generations--but with many periods of half a generation in there in which things at best plateau, and if you are forced to sell at the wrong time you will lose a good part of your shirt.

Given the large number of investors and institutions in our economy with very long time horizons that thought to be in the stock market for the long-term--insurance companies, pension funds, rich individuals with grandchildren--for me the anomaly does not seem to be a CAPE of 25 (or, given historical real returns on other asset classes and very low current yields on investments naked to inflation risk, 33) but rather the CAPEs of 14-20 that we saw in the 1980s, 1960s, 1950s, 1900s, 1890s, and 1880s that Robert Shiller appears to think of as "normal" and to which today's CAPE should someday return. Those are associated with warranted real average returns of between 5 and 7%/year. Why ever were stocks so unpopular as to limit demand so much as to offer such returns? Is there no long-term money? And so we have arrived at the biggest mystery of macro finance: the premium return on equities.

Yet Shiller thinks 25 is an anomaly that requires some non-fundamental psychological explanation:

I have conducted questionnaire surveys of individual and institutional investors.... When the CAPE ratio reached its record high of 44 in 2000, the confidence index hit a record low.... This year, the index took a dive for individual investors, and now is at the lowest level since 2000. The confidence of professional investors has fallen, too, but not as sharply. In short, people are beginning to worry.... It’s possible that bond prices account for today’s stock market valuations. But that raises another question: Why are bond prices so high? There are short-term explanations: the role of central banks, for example. But is there a compelling reason for prices of stocks and bonds (and maybe houses, too) to remain high indefinitely?... Perhaps today’s prices have something to do with anxiety about the future.... Such anxiety might push them to try to make up for... potential shortfalls by investing in stocks and bonds--even if they worry that these assets are overvalued.... I suspect that the real answers lie largely in the realm of sociology and social psychology--in phenomena like irrational exuberance, which, eventually, has always faded before...

That is a perspective very different from mine, which regards the failure of the CAPE to spend most of its time north of 25 as a mystery.

But given that it does not, it would be very rash for anybody who is not certain that they can wait out the market to invest more than they can afford to lose. And past performance is not only not a guarantee it may not be an indicator of future results. We have had one real Black Swan--World War I--in the past 130 years.

August 16, 2014

Alexander Hamilton at the Constitutional Convention: Weekend Reading

Alexander Hamilton, Federal Convention "Mr. Hamilton had been hitherto silent...

Alexander Hamilton, Federal Convention "Mr. Hamilton had been hitherto silent...

...on the business before the Convention, partly from respect to others whose superior abilities age, and experience rendered him unwilling to bring forward ideas, dissimilar to theirs; and partly from his delicate situation with respect to his own state, to whose sentiments as expressed by his colleagues he could by no means accede. The crisis, however, which now marked our affairs was too serious to permit any scruples whatever to prevail over the duty imposed on every man to contribute his efforts for the public safety and happiness. He was obliged therefore to declare himself unfriendly to both plans.

He was particularly opposed to that from New Jersey, being fully convinced that no amendment of the confederation leaving the states in possession of their sovereignty could possibly answer the purpose. On the other hand he confessed he was much discouraged by the amazing extent of the country in expecting the desired blessings from any general sovereignty that could be substituted.

As to the powers of the Convention, he thought the doubts started on that subject had arisen from distinctions and reasonings too subtle. A federal government he conceived to mean an association of independent communities into one. Different confederacies have different powers, and exercise them in different ways. In some instances the powers are exercised over collective bodies; in others over individuals, as in the German Diet, and among ourselves in cases of piracy. Great latitude therefore must be given to the signification of the term. The plan last proposed departs itself from the federal idea, as understood by some, since it is to operate eventually on individuals.

He agreed, moreover, with the Honorable Gentleman from Virginia (Mr. Randolph), that we owed it to our country to do on this emergency whatever we should deem essential to its happiness. The states sent us here to provide for the exigences of the Union. To rely on and propose any plan not adequate to these exigences, merely because it was not clearly within our powers, would be to sacrifice the means to the end. It may be said that the states cannot ratify a plan not within the purview of the Article of Confederation providing for alterations and amendments. But may not the states themselves, in which no constitutional authority equal to this purpose exists in the Legislatures, have had in view a reference to the people at large? In the senate of New York, a proviso was moved, that no act of the Convention should be binding until it should be referred to the people and ratified; and the motion was lost by a single voice only, the reason assigned against it being that it might possibly be found an inconvenient shackle.

The great question is: what provision shall we make for the happiness of our country? He would first make a comparative examination of the two plans--prove that there were essential defects in both--and point out such changes as might render a national one, efficacious.

The great and essential principles necessary for the support of government are:

An active and constant interest in supporting it. This principle does not exist in the states in favor of the federal government. They have, evidently in a high degree, the esprit de corps. They constantly pursue internal interests adverse to those of the whole. They have their particular debts--their particular plans of finance, et cetera, all these when opposed to invariably prevail over the requisitions and plans of Congress.

The love of power. Men love power. The same remarks are applicable to this principle. The states have constantly shewn a disposition rather to regain the powers delegated by them than to part with more, or to give effect to what they had parted with. The ambition of their demagogues is known to hate the control of the general government. It may be remarked too that the citizens have not that anxiety to prevent a dissolution of the general government as of the particular governments. A dissolution of the latter would be fatal: of the former would still leave the purposes of government attainable to a considerable degree. Consider what such a state as Virginia will be in a few years, a few compared with the life of nations. How strongly will it feel its importance and self-sufficiency?

An habitual attachment of the people. The whole force of this tie is on the side of the State Govt. Its sovereignty is immediately before the eyes of the people: its protection is immediately enjoyed by them. From its hand distributive justice, and all those acts which familiarize and endear government to a people, are dispensed to them.

Force, by which may be understood a coertion of laws or coertion of arms. Congress have not the former except in few cases. In particular states, this coercion is nearly sufficient; though he held it in most cases, not entirely so. A certain portion of military force is absolutely necessary in large communities. Massachusetts is now feeling this necessity and making provision for it. But how can this force be exerted on the states collectively? It is impossible. It amounts to a war between the parties. Foreign powers also will not be idle spectators. They will interpose, the confusion will increase, and a dissolution of the Union ensue.

Influence. He did not mean corruption, but a dispensation of those regular honors and emoluments, which produce an attachment to the government. Almost all the weight of these is on the side of the States; and must continue so as long as the states continue to exist.

All the passions then we see, of avarice, ambition, interest, which govern most individuals, and all public bodies, fall into the current of the states, and do not flow in the stream of the general government. The former therefore will generally be an overmatch for the general government and render any confederacy, in its very nature precarious. Theory is in this case fully confirmed by experience. The Amphyctionic Council had, it would seem, ample powers for general purposes. It had, in particular, the power of fining and using force against delinquent members. What was the consequence? Their decrees were mere signals of war. The Phocian war is a striking example of it. Philip at length, taking advantage of their disunion and insinuating himself into their councils, made himself master of their fortunes.

The German Confederacy affords another lesson. The authority of Charlemagne seemed to be as great as could be necessary. The great feudal chiefs however, exercising their local sovereignties, soon felt the spirit and found the means of encroachments which reduced the imperial authority to a nominal sovereignty. The Diet has succeeded, which though aided by a Prince at its head of great authority independently of his imperial attributes, is a striking illustration of the weakness of confederated governments. Other examples instruct us in the same truth. The Swiss cantons have scarce any Union at all, and have been more than once at war with one another. How then are all these evils to be avoided? Only by such a compleat sovereignty in the general government as will turn all the strong principles & passions above mentioned on its side. Does the scheme of New Jersey produce this effect? Does it afford any substantial remedy whatever? On the contrary, it labors under great defects, and the defect of some of its provisions will destroy the efficacy of others.

It gives a direct revenue to Congress, but this will not be sufficient. The balance can only be supplied by requisitions; which experience proves cannot be relied on. If states are to deliberate on the mode, they will also deliberate on the object of the supplies, and will grant or not grant as they approve or disapprove of it. The delinquency of one will invite and countenance it in others. Quotas too must in the nature of things be so unequal as to produce the same evil. To what standard will you resort? Land is a fallacious one. Compare Holland with Russia; France or England with other countries of Europe; Pennsylvania with North Carolina. Will the relative pecuniary abilities in those instances correspond with the relative value of land? Take numbers of inhabitants for the rule and make like comparison of different countries, and you will find it to be equally unjust. The different degrees of industry and improvement in different countries render the first object a precarious measure of wealth. Much depends too on situation. Contrast New Jersey and North Carolina, not being commercial States and contributing to the wealth of the commercial ones, can never bear quotas assessed by the ordinary rules of proportion. They will and must fail in their duty. Their example will be followed, and the Union itself be dissolved.

Whence then is the national revenue to be drawn? From Commerce, even from exports which, not-withstanding the common opinion, are fit objects of moderate taxation, from excise, etc. etc. These, though not equal, are less unequal than quotas. Another destructive ingredient in the plan is that equality of suffrage which is so much desired by the small states. It is not in human nature that Virginia and the large states should consent to it, or if they did that they should long abide by it. It shocks too much the ideas of justice and every human feeling. Bad principles in a government, though slow, are sure in their operation, and will gradually destroy it.

A doubt has been raised whether Congress at present have a right to keep ships or troops in time of peace. He leans to the negative. Mr. P.'s plan provides no remedy. If the powers proposed were adequate, the organization of Congress is such that they could never be properly and effectually exercised. The members of Congress, being chosen by the states and subject to recall, represent all the local prejudices. Should the powers be found effectual, they will from time to time be heaped on them, till a tyrannic sway shall be established.

The general power, whatever be its form, if it preserves itself must swallow up the state powers. Otherwise it will be swallowed up by them. It is agsainst all the principles of a good government to vest the requisite powers in such a body as Congress. Two Sovereignties can not co-exist within the same limits. Giving powers to Congress must eventuate in a bad Govt. or in no Govt. The plan of New Jersey therefore will not do.

What then is to be done?

Here he was embarrassed. The extent of the Country to be governed, discouraged him. The expence of a general government was also formidable; unless there were such a diminution of expence on the side of the state governments as the case would admit. If they were extinguished, he was persuaded that great oeconomy might be obtained by substituting a general government. He did not mean, however, to shock the public opinion by proposing such a measure. On the other hand he saw no other necessity for declining it. They are not necessary for any of the great purposes of commerce, revenue, or agriculture. Subordinate authorities he was aware would be necessary. >There must be district tribunals: corporations for local purposes. But cui bono the vast and expensive apparatus now appertaining to the states? The only difficulty of a serious nature which occurred to him, was that of drawing representatives from the extremes to the center of the community. What inducements can be offered that will suffice? The moderate wages for the 1st branch would only be a bait to little demagogues. Three dollars or thereabouts he supposed would be the utmost. The senate ,he feared from a similar cause, would be filled by certain undertakers who wish for particular offices under the government. This view of the subject almost led him to despair that a republican government could be established over so great an extent.

He was sensible at the same time that it would be unwise to propose one of any other form. In his private opinion he had no scruple in declaring, supported as he was by the opinions of so many of the wise and good, that the British government was the best in the world: and that he doubted much whether any thing short of it would do in America. He hoped gentlemen of different opinions would bear with him in this, and begged them to recollect the change of opinion on this subject which had taken place and was still going on. It was once thought that the power of Congress was amply sufficient to secure the end of their institution. The error was now seen by every one. The members most tenacious of republicanism, he observed, were as loud as any in declaiming against the vices of democracy. This progress of the public mind led him to anticipate the time when others as well as himself would join in the praise bestowed by Mr. Neckar on the British Constitution, namely, that it is the only government in the world "which unites public strength with individual security."

In every community where industry is encouraged, there will be a division of it into the few and the many. Hence separate interests will arise. There will be debtors and creditors, etc. Give all power to the many, they will oppress the few. Give all power to the few, they will oppress the many. Both therefore ought to have power that each may defend itself against the other. To the want of this check we owe our paper money--installment laws, etc. To the proper adjustment of it the British owe the excellence of their Constitution. Their House of Lords is a most noble institution. Having nothing to hope for by a change, and a sufficient interest by means of their property, in being faithful to the national interest, they form a permanent barrier against every pernicious innovation, whether attempted on the part of the Crown or of the Commons. No temporary Senate will have firmness enough to answer the purpose. The senate (of Maryland), which seems to be so much appealed to, has not yet been sufficiently tried. Had the people been unanimous and eager, in the late appeal to them on the subject of a paper emission they would would have yielded to the torrent. Their acquiescing in such an appeal is a proof of it.

Gentlemen differ in their opinions concerning the necessary checks from the different estimates they form of the human passions. They suppose seven years a sufficient period to give the senate an adequate firmness, from not duly considering the amazing violence and turbulence of the democratic spirit. When a great object of government is pursued, which seizes the popular passions, they spread like wildfire, and become irresistable. He appealed to the gentlemen from the New England States whether experience had not there verified the remark.

As to the Executive, it seemed to be admitted that no good one could be established on republican principles. Was not this giving up the merits of the question; for can there be a good government without a good Executive? The English model was the only good one on this subject. The hereditary interest of the King was so interwoven with that of the nation, and his personal emoluments so great, that he was placed above the danger of being corrupted from abroad--and at the same time was both sufficiently independent and sufficiently controlled to answer the purpose of the institution at home.

One of the weak sides of Republics was their being liable to foreign influence & corruption. Men of little character, acquiring great power, become easily the tools of intermedling neighbors. Sweeden was a striking instance. The French and English had each their parties during the late revolution which was effected by the predominant influence of the former. What is the inference from all these observations? That we ought to go as far in order to attain stability and permanency as republican principles will admit. Let one branch of the legislature hold their places for life or at least during good-behavior. Let the executive also be for life. He appealed to the feelings of the members present whether a term of seven years would induce the sacrifices of private affairs which an acceptance of public trust would require, so as to ensure the services of the best citizens.

On this plan we should have in the senate a permanent will, a weighty interest, which would answer essential purposes. But is this a republican government, it will be asked? Yes, if all the magistrates are appointed, and vacancies are filled, by the people, or a process of election originating with the people. He was sensible that an executive constituted as he proposed would have in fact but little of the power and independence that might be necessary. On the other plan of appointing him for 7 years, he thought the executive ought to have but little power. He would be ambitious, with the means of making creatures; and as the object of his ambition would be to prolong his power, it is probable that in case of a war, he would avail himself of the emergence, to evade or refuse a degradation from his place.

An executive for life has not this motive for forgetting his fidelity, and will therefore be a safer depositary of power. It will be objected, probably, that such an executive will be an elective monarch, and will give birth to the tumults which characterise that form of government. He would reply that Monarch is an indefinite term. It marks not either the degree or duration of power. If this executive magistrate would be a monarch for life--the other proposed by the report from the Committee of the Whole, would be a monarch for seven years. The circumstance of being elective was also applicable to both. It had been observed by judicious writers that elective monarchies would be the best if they could be guarded against the tumults excited by the ambition and intrigues of competitors. He was not sure that tumults were an inseparable evil. He rather thought this character of elective monarchies had been taken rather from particular cases than from general principles.

The election of Roman Emperors was made by the Army. In Poland the election is made by great rival princes with independent power, and ample means, of raising commotions. In the German Empire, the appointment is made by the electors and princes, who have equal motives and means for exciting cabals and parties. Might not such a mode of election be devised among ourselves as will defend the community against these effects in any dangerous degree?

Having made these observations, he would read to the Committee a sketch of a plan which he should prefer to either of those under consideration. He was aware that it went beyond the ideas of most members. But will such a plan be adopted out of doors? In return he would ask will the people adopt the other plan? At present they will adopt neither. But he sees the Union dissolving or already dissolved--he sees evils operating in the states which must soon cure the people of their fondness for democracies--he sees that a great progress has been already made and is still going on in the public mind. He thinks therefore that the people will in time be unshackled from their prejudices; and whenever that happens, they will themselves not be satisfied at stopping where the plan of Mr. Randolph would place them, but be ready to go as far at least as he proposes.

He did not mean to offer the paper he had sketched as a proposition to the Committee. It was meant only to give a more correct view of his ideas, and to suggest the amendments which he should probably propose to the plan of Mr. Randolph in the proper stages of its future discussion. He read his sketch in the words following: to wit:

"The Supreme Legislative power of the United States of America to be vested in two different bodies of men; the one to be called the Assembly, the other the Senate, who together shall form the Legislature of the United States, with power to pass all laws whatsoever subject to the Negative hereafter mentioned.

The Assembly to consist of persons elected by the people to serve for three years.

The Senate to consist of persons elected to serve during good behaviour; their election to be made by electors chosen for that purpose by the people: in order to this the states to be divided into election districts. On the death, removal or resignation of any senator his place to be filled out of the district from which he came.

The supreme executive authority of the United States to be vested in a Governour to be elected to serve during good behaviour. The election to be made by electors chosen by the people in the election Districts aforesaid. The authorities and functions of the executive to be as follows: to have a negative on all laws about to be passed, and the execution of all laws passed, to have the direction of war when authorized or begun; to have with the advice and approbation of the senate the power of making all treaties; to have the sole appointment of the heads or chief officers of the departments of finance, war, and foreign affairs; to have the nomination of all other officers (ambassadors to foreign nations included) subject to the approbation or rejection of the senate; to have the power of pardoning all offences except treason; which he shall not pardon without the approbation of the Senate.

On the death, resignation, or removal of the Governour his authorities to be exercised by the President of the Senate till a successor be appointed.

The Senate to have the sole power of declaring war, the power of advising and approving all treaties, the power of approving or rejecting all appointments of officers except the heads or chiefs of the departments of finance, war, and foreign affairs.

The supreme judicial authority to be vested in judges to hold their offices during good behaviour with adequate and permanent salaries. This court to have original jurisdiction in all causes of capture, and an appellative jurisdiction in all causes in which the revenues of the general government or the citizens of foreign nations are concerned.

The Legislature of the United States to have power to institute courts in each state for the determination of all matters of general concern.

The Governour, Senators, and all officers of the United States to be liable to impeachment for mal and corrupt conduct; and upon conviction to be removed from office, and disqualified for holding any place of trust or profit. All impeachments to be tried by a Court to consist of the chief or judge of the Superior Court of Law of each State, provided such judge shall hold his place during good behavior, and have a permanent salary.

All laws of the particular states contrary to the Constitution or laws of the United States to be utterly void; and the better to prevent such laws being passed, the Governour or President of each state shall be appointed by the general government and shall have a negative upon the laws about to be passed in the state of which he is Governour or President.

No state to have any forces land or naval; and the militia of all the States to be under the sole and exclusive direction of the United States, the officers of which to be appointed and commissioned by them.

On these several articles he entered into explanatory observations corresponding with the principles of his introductory reasoning.

Comittee rose, and the House adjourned.

Noted for Your Afternoon Procrastination for August 16, 2014

Over at Equitable Growth--The Equitablog

Over at Equitable Growth--The Equitablog

Afternoon Must-Read: Narayana Kocherlakota: 'Persistently Below-Target Inflation Rate is a Signal That the U.S. Economy is Not Taking Advantage of all of its Available Resources' - Washington Center for Equitable Growth

Nick Bunker: The shifts in household debt and the need for more data - Washington Center for Equitable Growth

Nick Bunker: Weekend reading - Washington Center for Equitable Growth

Over at Grasping Reality: Alexander Hamilton at the Constitutional Convention: Weekend Reading - Washington Center for Equitable Growth