C. Litka's Blog, page 48

November 29, 2020

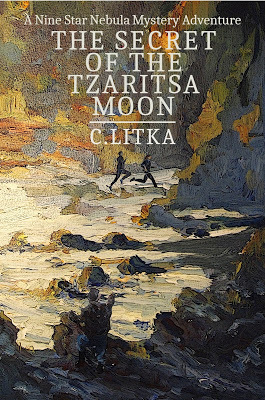

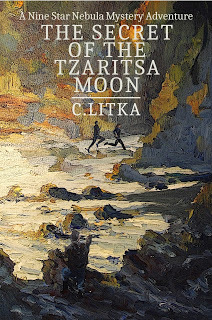

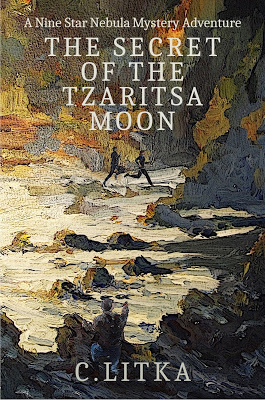

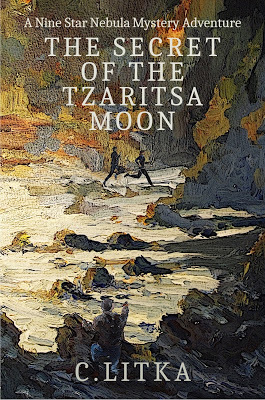

The Secret of the Tzaritsa Moon is FREE on Amazon

I'm happy to announce that Amazon has made my newest book, The Secret of the Tzaritsa Moon, FREE on Amazon.com. Recent experience with Amazon and their price matching policy suggests that this will FREE price will not last long. So Kindle readers, here's your chance to discover why a certain pirate prince wanted to sell the Tzaritsa Moon to its insurance company...

The Secret of the Tzaritsa Moon

“I signedaboard the Tzaritsa Moon as her second engineer. I ended up a toaster repairman. I was very lucky.” – Rafe d’Mere, from The Secret of the Tzaritsa Moon

The Secret of the Tzaritsa Moonmarks the long awaited return to the Nine Star Nebula of the Bright Black Sea. This story takes place in the Alantzia star system, the most remote of the eight solar systems. The Alantzia system is known for its many little worlds, moons, and rocks that are reputed to be more like the “lawless” drift worlds than the staid worlds of the Unity.

Old spaceers convinced Rafe d’Mere that to fully appreciate the exotic romance of the Alantzian experience, he needed to ship out on one of the small planet traders which call on the eccentric little worlds of the system. So he did, signing aboard the Tzaritsa Moon, under the name Rye Rylr, as her second engineer.

On the passage to Fairwaine, Rafe’s swift response to a critical engine failure saved the Tzaritsa Moon. And his life. However, the failure was deliberate, part of a pirate prince’s plan to keep the Tzaritsa Moon from arriving in Fairwaine orbit. And when it did, thanks to Rafe, the pirate prince was not happy. At best, Rafe might expect his memory of the incident to be erased. Erasing Rafe would, however, work just as well.

So Rafe needed to get clear of the Tzaritsa Moon and get very lost on Fairwaine until things cooled down. However, while doing so, he crossed orbits with a thief. A girl with a pretty face, who may, or may not, have been a covert agent of the Patrol. She was rather evasive on that point. But she was determined to discover why the pirate prince wanted the Tzaritsa Moon destroyed. And Rafe found that he couldn’t resist helping her. She had a pretty face.

The Secret of the Tzaritsa Moon is a cozy SF mystery adventure. It features Rafe d’Mere, ex-Patrol contraband suppression and repair tech, now a spaceer engineer, and Vaun Di Ai, who seems to be a Patrol Lieutenant JG, Intelligence Analyst 2, who had, somehow, escaped her desk job to be an acting covert agent. The story is set mostly on the moon of Fairwaine, and in one of its old fashioned, nonconforming societies. One that uses toasters to make toast.

C. Litka writes old fashioned stories with modern sensibilities, humor, and romance. He spins tales of adventure, mystery, and travel set in richly imagined worlds, with casts of colorful, fully realized characters. If you seek to escape your everyday life, you will not find better company, nor more wonderful worlds to travel and explore, than in the stories of C. Litka.

November 25, 2020

A Million Flowers

Make that millions of flowers. Flowers of creation. Flowers of a revolution. Computers, the internet, and self-publishing platforms like Wattpad, fanfic sites, Smashwords, Amazon, Kobo, Apple, and other self-publishing book sites have given millions of people around the world the opportunity, and the incentive, to be creative. To tell a story of their own. Technology has made it possible for people in all walks of life to write and share their stories with readers around the world. And in many cases, form communities of storytellers and readers who celebrate, share, and help each other as writers. Anyone, and everyone, can tell their stories, regardless of their level of accomplishment. And by doing so, they can grow in their craft by both by writing, and with the help of other readers and storytellers.

This tech revolution has also allowed many people the opportunity to publish and share with the world, their expertise on a million different subjects in articles, blogs and books. It has given people with special, obscure, and niche interests the chance to not only share their interests with the world, but to establish links with others who share their interests, people they would never have met without these technologies.

In short, it’s a wonderful world.

Since I’m a writer of fiction, I’m going to focus on the storytellers of this revolution.

I need, however, to first address the issue of accomplishment. There are many who dismiss the world of self-published books as a cesspool of bad books. And there are writers who feel that the presence of these millions of non-traditionally written books are suppressing the ability of their presumably superior products to shine. And by shining, they mean making a boat load of money from their books. Essentially they are saying that someone else is to blame for their lack of commercial success. But hey, that’s the nature of the market. One needs a business model to address it, or one will deserve to fail.

However, that’s commerce, not art. In my view, creating a story is art. There are many levels off accomplishment in any art. And often it takes decades of practice to become very accomplished in one’s field. But you have to start somewhere. And while the traditional advice for someone seeking to write commercially is to keep one’s early, less accomplished work, in a drawer, I have to ask why? The answer, I suspect, has more to do with the commercial aspects of traditional publishing than with art – the publishing houses want to limit the height of their slush piles, and authors want to limit the supply of potential competitors. Now, I believe that writing is an art. Art, however, becomes a product when it is offered for sale, which is something that needs to be judged differently than a work of art. And that is beyond the scope of this essay.

Still, I'll admit that most of the books in that field of flowers, or the cesspool, were probably written to be products rather than art. However, given the long odds of any of them ever being viable products, I think that the vast majority of them can be viewed simply as an expression of art. I will also readily admit that many of them, in my opinion, are not very accomplished works of art. But then, I’m a rather harsh critic, and find that there are a lot of traditionally published books that I don't think are all that accomplished works of art -- even if they are good products.

The thing with self-published books, however, is that if viewed as art, they are the real deal. They haven’t been selected by the marketing department of a publishing house to appeal to a certain market. And they haven’t been manipulated in the editing process to conform to that target market. Self-published books are the authentic, unadulterated creation of their writers. And while they may have been written with a target audience in mind, they still reflect how the individual writer envisions the product for the market they are aiming for.

I’m not going to pretend that I’ve read a lot of self-published books. Given my narrow tastes, there’s no way I’d read most of the ones I've sampled all the way through. However, what I do find interesting is that even the free samples of the story offers a window into the mind and imagination of the author. There’s a Jim Morrison’s tune, “People are Strange.” No truer lyrics have ever been written. We’re all strange. And the thing about writing is that it is often a window into the strangeness that lies within all of us. This alone makes even the least accomplished written story interesting, even if one can only stand to read a few pages of it. I read a couple of pages – or a chapter or two, and then sit back and wonder… What?

I’ve sampled a writer where even the blurb is hard to follow – a rush of breathless words and a tumbling cascade of ideas. And the stories read like an outline of ideas and events rather than the story. One wonders if this writer has ever compared what they write to what they’ve read. And yet, this writer has produced a dozen or more books, because the writer as so many ideas, so many stories. Neat.

I’ve sample the story of a fellow who hoped to make a ton of money on his book. The sample I read seemed to eerily parallel what little I could gather of his life, but it painted him becoming the super intelligent hero of the story. He put it on Amazon for twice the usual price of a self-published first novel, and the last time I looked, had never sold a single copy there. And he never lowered the price. I’m petty sure he has assigned blame for his failure to something other than himself. Sad.

I’ve sampled a few of the young writers on Wattpad which often offer interesting glimpses into the minds, dreams, and culture of the youth. Plus a feel for other cultures, with unfamiliar norms. Fresh.

And of course, because I read speculative fiction – well, mostly space opera stuff – I find lots of strange, and not so strange worlds. Sometimes the stories immediately bring to mind movies or TV shows. In these, I get to see just what aspects impressed the writers. A number of them have scenes with ship captains sitting a chair on the bridge barking commands to the crew at their stations all around them…Star Trek. Or some sort of fearful master dressed in a mask and a cape who strangles subordinates at will for minor mistakes because they’re evil. Star Wars. Or loading a down-and-out tramp ship loading a few crates of cargo and mysterious people up the ramp. Firefly. Fanfic in a mask.

Sometimes you are left wondering how these writers ever came to write speculative fiction at all, as they seem almost totally unfamiliar with basic science. Was it cartoons, anime or what? Curious.

There are worlds that are very familiar, others that are very bizarre. Worlds that seem small like stage plays, and others that toss galaxies around like bus stops. So many ways to imagine an alternate world. So many ways to think.

Whatever the level of accomplishment – and this is subjective as well as objective – I can appreciate these little glimpses into the minds and dreams of other people.

And what’s more, I can admire them for the effort they put into bringing forth the stories they tell, however they tell it. Writing takes an effort, and finishing a story is an accomplishment, no matter how accomplished one is at the craft of writing. And it takes courage to put one’s creations out for people to view, read, enjoy, or criticize. So however accomplished, or not, the writing is, publishing a story is an accomplishment to be admired. It is the process of creation – the journey as it were – that is the heart of creation, not the end. And I feel that should be celebrated.

So in self-publishing, one has this field of flowers stretching away to the horizons. Millions of them. And yes, they’re mostly wildflowers, with a few escapees from traditional gardens scattered here and there. But each is unique. Each of these flowers blossom as an expression of creativity from deep within the writers’ wells of dreams and imagination.

Let the flowers bloom!

November 20, 2020

The Secret of the Tzaritsa Moon is Now Available.

My cozy speculative fiction mystery adventure story is now available. Ebooks are either free in most ebook stores, or $.99 on Amazon stores. The trade paperback is priced at $10.00 Links below. I had a lot of fun writing this story, and I hope it shows. I'm currently working on a sequel with the same characters and locale with a target release date of February-March 2021.

My cozy speculative fiction mystery adventure story is now available. Ebooks are either free in most ebook stores, or $.99 on Amazon stores. The trade paperback is priced at $10.00 Links below. I had a lot of fun writing this story, and I hope it shows. I'm currently working on a sequel with the same characters and locale with a target release date of February-March 2021.The Secret of the Tzaritsa Moon

“I signedaboard the Tzaritsa Moon as her second engineer. I ended up a toaster repairman. I was very lucky.” – Rafe d’Mere, from The Secret of the Tzaritsa Moon

The Secret of the Tzaritsa Moonmarks the long awaited return to the Nine Star Nebula of the Bright Black Sea. This story takes place in the Alantzia star system, the most remote of the eight solar systems. The Alantzia system is knownfor its many little worlds, moons, and rocks that are reputed to be more like the “lawless” drift worlds than the staid worlds of the Unity.

Old spaceers convinced Rafe d’Mere that to fully appreciate the exotic romance of the Alantzian experience, he needed to ship out on one of the small planet traders which call on the eccentric little worlds of the system. So he did, signing aboard the Tzaritsa Moon, under the name Rye Rylr, as her second engineer.

On the passage to Fairwaine, Rafe’s swift response to a critical engine failure saved the Tzaritsa Moon. And his life. However, the failure was deliberate, part of a pirate prince’s plan to keep the Tzaritsa Moon from arriving in Fairwaine orbit. And when it did, thanks to Rafe, the pirate prince was not happy. At best, Rafe might expect his memory of the incident to be erased. Erasing Rafe would, however, work just as well.

So Rafe needed to get clear of the Tzaritsa Moon and get very lost on Fairwaine until things cooled down. However, while doing so, he crossed orbits with a thief. A girl with a pretty face, who may, or may not, have been a covert agent of the Patrol. She was rather evasive on that point. But she was determined to discover why the pirate prince wanted the Tzaritsa Moon destroyed. And Rafe found that he couldn’t resist helping her. She had a pretty face.

The Secret of the Tzaritsa Moon is a cozy SF mystery adventure. It features Rafe d’Mere, ex-Patrol contraband suppression and repair tech, now a spaceer engineer, and Vaun Di Ai, who seems to be a Patrol Lieutenant JG, Intelligence Analyst 2, who had, somehow, escaped her desk job to be an acting covert agent. The story is set mostly on the moon of Fairwaine, and in one of its old fashioned, nonconforming societies. One that uses toasters to make toast.

Amazon($.99)Ebook: Amazon

Amazon Trade Paperback book ($10.00) Amazon

Google(FREE): Google Play Store

Smashwords (FREE):Smashwords

The book should be available on Kobo, B & N, & Apple books shortly

November 11, 2020

Writing as Art

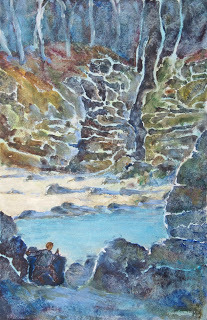

In a Wilderness of Dunes, in my impressionistic style of painting

In a Wilderness of Dunes, in my impressionistic style of painting I view my stories, like my paintings, as art. I write and paint to bring something new into the world. To create. I also try to make it good, though I am the sole judge of what is good, and what falls short of being good enough. I try to be critical of my work. I don’t expect to succeed all the time, or indeed, most of the time. I expect to always fall short of total success. Masterpieces are masterpieces because they are very rare. However, I don’t get discouraged by falling short of perfection. Falling short is part of the process – especially if you, like me, are exploring an art form on your own rather then by the book or in class. We must expect to learn by trial and by error. And mostly error. We have to be honest with ourselves about our shortcomings. And yet, be happy enough with our little successes to try to fix our shortcomings the next time we set out to create our art. It’s a journey, not a destination.

Big Pine Bend in my watercolor style of painting

Big Pine Bend in my watercolor style of painting

For me, the criteria I judge my writing and painting on, are my own tastes. Period. Everyone else is welcome to their opinion, but for me, my opinion is the only one that counts. I will often come across writing advice that says that you need to get other people’s input, which I do. My wife will tell me if something seems wrong. But they also advise one to hire an editor, because you, as the writer, are too close to your work to see its flaws. This advice comes from a particular, and often unsaid mindset – that you are writing to reach a commercially viable audience – or at least you should be. A good editor knows what is selling in the fleeting moment, and will shape a manuscript to conform to the current tastes of the target audience so as to increase the chances of the book selling enough copies to make publishing it turn a profit on it. Which is all fine and dandy. Makes sense. Book publishing is a business, and business have to make money if they are to continue to be one.

Misty Morning in Crofthaven, in my impressionist style

Misty Morning in Crofthaven, in my impressionist style

However, I am not in the business of publishing books. I’m not in business at all. I’m terrible at business. As I said, I’m an artist. And what I seek to do is to bring my imaginary people and places to life in the imagination of other people through words and paintings. In doing so, I take the same approach to writing as I do to painting. I try to be critical of my work, and release the best book I reasonably can. Reasonably, in the sense that there are a hundred different ways of saying anything in English, and that on any given day, I know that I’ll prefer one way over the other ninety-nine. This means that I can never read more than a few pages of mine without wishing I’d said something better. However, if you are ever going to share a story, at some point you have to say, enough is enough. It is what it is. Release it, and hope to do better the next time.

Cealanda in my watercolor style, though in this I used acrylic paint on canvas

Cealanda in my watercolor style, though in this I used acrylic paint on canvas

In addition to deciding when I’ve reached the point where I could fiddle with it forever without making it appreciably better, I also make decisions about what I want to tell, and how. Since I am not in the business of writing, I’m not concerned about how to make my stories appeal to the most people. Instead, I tell the stories the way I think my first person narrator would tell them. For example, in A Summer in Amber, I have two chapters devoted to weekend trips – a bicycle tour and an overnight sail. Neither chapter advances the main plot one iota. At best they can be considered world building. However, they remain in my story because I enjoyed writing the character Red Stuart, who is featured in those chapters, and secondly, because my narrator, Sandy Say, is writing essentially a “what I did on my summer vacation” story, would certainly have include those adventures in his story, since they were part of that memorable summer. All of my stories have that same priority – they are told by a character in that story, and told in a manner that character would tell the story. As such, they include things that the character would include in his telling – regardless of what an editor employed to take a creative work and make a product out of it, would think of it.

Crescent Park Study 2 in my impressionist style

Crescent Park Study 2 in my impressionist styleAnd perhaps I should add here, that I write, as I paint, by instinct and, I would like to believe, talent. I am always amazed when I hear authors talk about their books as engineering projects, with all sorts of standard components placed in standard patterns. Every component of the story is engineered to produce a desired effect. Not that I'm criticizing that approach, I'm just saying that I can't think of a story in that way, at least not in the detail they work with. I take a much more organic approach to a story.

However, writers, like myself, live in a sort of golden age. Ebooks, the internet, and self publishing has allowed me and millions of other people to tell our stories. Now, many, but by no means, all, of those stories are written as products to sell. And many, if not most of those products, are really bad products. Still, as I said, there are those of us who simply have imaginary stories that we want to bring to a life outside of our imaginations. And judged on that basis, there are no bad stories. What counts is that journey from our imagination into the world, not the number of destinations it arrives at. Being creative is what matters.

Side Note

I've illustrated this post with several of my paintings in my two main styles of painting. I started painting regularly (50 paintings a year or so) using ink and watercolors 1992. They are of an imaginary country, Cealanda, that I, as the painter, rambled around in painting what I saw. I suspect that my paintings in this style are several times (or more) more popular than my impressionist paintings. I turned to oil and acrylic paints when I started selling paintings in 2003, as they command more money than watercolors. I found it hard to paint in thick paints, and at 53, I didn't have time to start over again. Luckily I always like impressionist paintings, so I adopted that style as my own. I think my impressionist works are better than my watercolors. I've painted a thousand of them, even though maybe only one person in a hundred (who appreciate art) really appreciates them. Like in my writing, I get to decide what is good and want isn't. Not the market. And the best of them are good.

November 6, 2020

The Secret of the Tzaritsa Moon -- 19 November 2020

My latest novel, The Secret of the Tzaritsa Moon will be released on 19 November 2020 as a free ebook on Smashwords, Apple, Kobo, B & N, and Google. It will be priced at $.99 on Amazon. Free is my preferred price, but hey, it's worth a buck. It will be up for pre-order on Amazon shortly.

Rafe d’Mere’s quick thinking saved the spaceship Tzaritsa Moon from a catastrophic explosion. He made some very unpleasant people very unhappy.

The Secret of the Tzaritsa Moon marks the long awaited return to the Nine Star Nebula of the Bright Black Sea. This story takes place in the Alantzia star system, the most remote of the eight star systems. The Alantzia system is rather infamous for its many little worlds, moons, and rocks that are reputed to be more like the “lawless” drift worlds than the staid worlds of the Unity.

To fully appreciate the exotic romance of the Alantzian experience, old spaceers convinced Rafe d’Mere that he needed to ship out on one of the small planet traders that called on the eccentric little worlds of the system. So he did, signing aboard the Tzaritsa Moon, under the name Rye Rylr, as her second engineer.

Fortunately for Rafe, his swift response on discovering a dangerous hot spot on the no. 7 plasma injector tube saved the ship. And his life. Unfortunately for Rafe, one of the pirate princes of the Alantzia had made arrangements for the Tzaritsa Moon not to reach Fairwaine orbit. And when she did, thanks to Rafe, the pirate prince was far from happy. The best Rafe could hope for at the hands of this pirate prince was to have his memory of the voyage erased. Erasing Rafe would, however, work just as well.

So Rafe decided that he needed to get clear of the Tzaritsa Moon and get very lost on Fairwaine until things cooled down. Fortunately, and again, unfortunately, while doing so, he crossed orbits with a thief; a girl with a pretty face. She may, or may not, have been a covert agent of the Patrol. She was rather evasive about that. But she was very clear about her desire to discover why the pirate prince wanted the Tzaritsa Moon destroyed. And Rafe found that he couldn’t resist helping her to do so. She had a pretty face.

The Secret of the Tzaritsa Moon is a cozy SF mystery adventure. It features the new characters of Rafe d’Mere, ex-Patrol contraband suppression and repair tech, now a spaceer engineer, and Vaun Di Ai, who probably is a Patrol Lieutenant JG, Intelligence Analyst 2, who had, somehow, escaped her desk job to be an acting covert agent. The story is set mostly on the moon of Fairwaine, in an old fashioned, nonconforming society, that uses toasters to make toast.

November 1, 2020

FIve and One Half Years in Self Publishing

Time flies, and so, once again, it’s time to report my May 2020 through October 2020 results.

Irelease twonew stories in the last six months. The first was Lines in the Lawn, an illustrated children’s short story via Smashwords only. It was something I had laying around for a decade and I decided to get it out. The second new release was a novella, Keiree. Currently it is a stand alone story, but I hope to build on it, to eventually roll it into a novel.

Sales Numbers

As usual, almost all of the sales are free ebooks sold through Amazon, Smashwords, Apple, B & N, and Google. My books are also available on Kobo but they do not report free sales to Smashwords, plus some are also listed on other sites that offer free books as well.

Book Title / Release Date

1H 2020 Sales

Total Sale To date

A Summer in Amber

23 April 2015

371

7,589

Some Day Days

9 July 2015

163

4,016

The Bright Black Sea

17 Sept 2015

542

13,036

Castaways of the Lost Star

4 Aug 2016

Withdrawn

2,176

The Lost Star’s Sea

13 July 2017

440

6,423

Beneath the Lanterns

13 Sept 2018

253

2,493

Sailing to Redoubt

15 March 2019

221

1,825

Prisoner of Cimlye

2 April 2020

240

485

Lines in the Lawn*

8 June 2020

55

55

Keiree*

18 Sept 2020

174

174

Total Six Month Sales

* New releases.

2,219

38,275

For comparison sake, for the same time period last year I sold 4,590 books, without the last three books on this chart. So last year I sold a little over twice as many books last year as I did this year. Last year, however, was unexpectedly, my best year ever.

For this time period my sales split between Amazon, Google, and Smashwords (including sales on Apple and B & N) works out like this:

Amazon 35%

Smashwords (Apple & B & N) 39%

Google 26%

Last year, 1 Nov 2019 the breakdown was,

Amazon 39%

Smashwords 52%

Google 9%

If we look at sales this past month, October 2020, the split looks like this:

Amazon (15%)

Smashwords (54%)

Google (31%)

The numbers show that my Amazon sales are fading. Smashwords is, more or less holding steady (though half of what it was in 2019), but Google has come through to pick up some of the slack. My goal is to sell at least 300 books a month, as so far I’m clearing that bar, though it takes more books in my catalog to do so.

Back in May, in my 5th annual report, I wrote that I did not expect 2020 to be a banner year. Indeed, I had not expected 2019 to be a banner year either, but it turned out to be one. However, this time around, it’s looking like I’ll be right. The first half hasn’t been terrible, but it is definitely off last year’s pace.

Headwinds

As I see it, there are two things outside of my control that are weighing on my sales. The first is that it seems that Amazon no longer feels the need to match prices. While my older books are still free, my newer books are not. I’ve made the usual efforts to get them to match the free price of the other ebook stores, but even if successful, that only lasts for a couple of weeks before they’re back to full price.

Now, $.99 is a cheap price, and I do sell some at that price, but free sells much better. Unfortunately, Amazon accounts for something like 70% or more of the ebook market, so this new policy bites into my sales.

The second drag on my sales is the way that the ebook market has evolved. Five years ago, ebook advocates were talking about how ebooks would come to dominate the market for books, making paper books extinct. This is clearly not the case now, nor will it be for the foreseeable future. Ebooks have evolvedto dominate some types of genre fiction, like romance, and SFF, whichwere formally served by pulp magazines, mass market paperbacks, and libraries. And in those categories to a very special type of reader, the avid readers. These readers what and expect books to reliably deliver what they expect them to deliver, like the fans of Big Macs, which are expected to taste the same no matter where you consume it. Ebooks are, in short, have become the fast food of books.

This is, of course, alegitimate market. And nice work, if you can get it. But it takes more than books to get in it. These days it takes thousands of dollars of advertising, and a large,established readership that an indie-publisher can bet thosethousands of dollars of advertising on. Pay to play, as they say. Just as with Etsy, where the local handmade goods market evolved into handmade goods from the sweatshops of China, the author self-publisher has evolved in a similar way. Today, the best selling books are produced bythe entrepreneur publisher who either works 16 hours a day to write, manage advertising on a daily basis, hire editors, cover artists, and manage the business in general, or to someone who hire others to do all these tasks, including writing, in order toproduce a dependable stream of, good-enough Big Mac type booksto feed their customers in the Kindle Unlimited all-you-can-read buffet.

I have no desire to be on that treadmill.Better them than me, is pretty much my attitude. But the downside of this evolution is that unless a writer is producing and spending big money promoting their Big Mac books, the market is for ebooks is deceptively shallow these days. I’m lucky to have gotten into self publishing when I did, as I doubt that I’d be able to give away 38,000 books in five and half years on a zero advertising budget if I was starting today. My initial experiment was to see if I could use free books to build an audience and a presence large enough that I could some day, if I cared to, charge money for my books. I have to say that, given the way the market has evolved, the answer seems to be no. Fortunately for me, it was an academic experiment, so I can’t, and am not complaining.

Looking Ahead

I will be releasingmy next novel, a cozy SF mystery/adventure, The Secret of the Tzaritsa Moon, either this month or in early December. I’m planning on starting a second cozy SF mystery/adventure with the same characters this month, with a target release date oflate February or early March. I may decide to release Lines in the Lawn on Amazon. And I have another small project of short-short stories and cartoons dealing with robots that I might work on at some point as well in the next six months. I’ve got nothing better to do these days than write, so as long as I have ideas, I’ll be writing, if not selling a ton of books.

October 26, 2020

The Secret of the Tzaritsa Moon

His quick thinking saved the spaceship Tzaritsa Moon from a catastrophic explosion, making some very unpleasant people very unhappy.

The Secret of the Tzaritsa Moonmarks the long awaited return to the Nine Star Nebula of the Bright Black Sea. This story takes place in the Alantzia star system, the most remote of the eight star systems. The Alantzia system is rather infamous for its many little worlds, moons, and rocks that are reputed to be more like the “lawless” drift worlds than the staid worlds of the Unity.

To fully appreciate the exotic romance of the Alantzian experience, old spaceers convinced Rafe d’Mere that he needed to ship out on one of the small planet traders that called on the eccentric little worlds of the system. So he did, signing aboard the Tzaritsa Moon, under the name Rye Rylr, as her second engineer.

Fortunately for Rafe, his swift response on discovering a dangerous hot spot on the no. 7 plasma injector tube saved the ship. And his life. Unfortunately for Rafe, one of the pirate princes of the Alantzia had made arrangements for the Tzaritsa Moon not to reach Fairwaine orbit. And when she did, thanks to Rafe, the pirate prince was far from happy. The best Rye could hope for was to have his memory of the voyage erased. Erasing Rafe would, however, work just as well.

So Rafe needed to get clear of the Tzaritsa Moon and get very lost on Fairwaine until things cooled down. Fortunately, and again, unfortunately, while doing so, he crossed orbits with a thief; a girl with a pretty face. She may, or may not, have been a covert agent of the Patrol. She was rather evasive about that. But she was very clear about her desire to discover why the pirate prince wanted the Tzaritsa Moon destroyed. And Rafe found that he couldn’t resist helping her to do so. She had a pretty face.

The Secret of the Tzaritsa Moon is a cozy SF mystery adventure. It features the new characters of Rafe d’Mere, ex-Patrol contraband suppression and repair tech, now a spaceer engineer. And Vaun Di Ai, who probably is a Patrol Lieutenant JG, Intelligence Analyst 2, who had, somehow, escaped her desk job to be an acting covert agent. The story is set mostly on the moon of Fairwaine, in an old fashioned, nonconforming society, that uses toasters to make toast.

Coming Soon!

The Secret of the Tzaritsa Moon is 64,000 word novel that will be available as a free ebook in the Smashwords, Apple, Google, Barnes & Noble, and Kobo ebook stores. And for $.99 on Amazon. It will also be available as a trade paperback for $9.00 on Amazon and wherever fine books are sold.

October 20, 2020

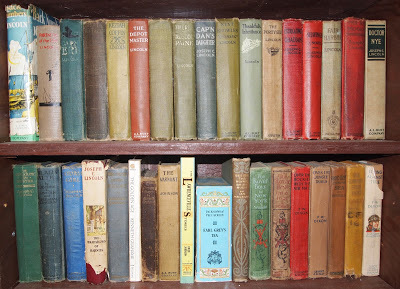

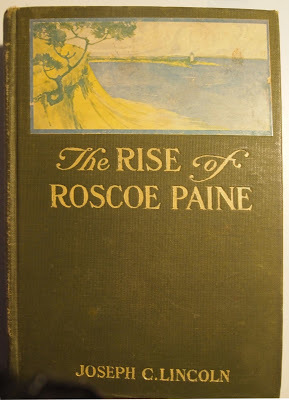

My Library -- Joseph Lincoln

Joseph Lincoln (1870 -1944) was an American novelist, short story writer, and poet. Much of his work is set in a fictionalized version of Cape Cod, north of Boston Massachusetts, USA from the 1870’s to the 1920’s or so. He was a popular writer in his time, with his work appearing magazines like the Saturday Evening Post and The Delineator.

I own 21 of his books, and I believe I’ve read a few more as ebooks. Wikipedia lists 45 books. However, my collection does not include many of this books from the 1930’s and 40’s. The Wikipedia article, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Joseph_C._Lincolnsuggests that his stories can be seen as “a pre-modern haven occupied by individuals of old Yankee stock which was offered to readers as an antidote to an America that was undergoing rapid modernization, urbanization, immigration, and industrialization.” I can say that there is certainly an air of nostalgia for a simple life in these stories of “old Cape Cod,” a hundred years later. And I can attest to the fact that his stories were filled with “characters.

My first Joe Lincoln book was Partners in the Tide, written in 1905. I picked it up in the book building of the giant rummage sale that a local charity, Bethesda Lutheran Home, ran every year, that filled up the local county fair grounds with junk and treasures. I picked up many a'treasure at the Bethesda Fair. Sadly it has now gone the way of “old Cape Cod.” But in the day, I'd get up early and be waiting for its opening, along with hundreds of other treasure hunters among the fairground buildings full of rummage. Anyway, back to the subject at hand, which I believe was my first Joe Lincoln book. I picked it up solely on its title, since I was collecting nautical books. It was something of a nautical book, in that it told the story of an orphan growing up on Cape Cod, his adventures at sea, and then returning to Cape Cod to become a member of the “Wrecking Syndicate” which is to say, a partner in a company that salvaged ships that ran aground or sunk off the shoals of Cape Cod for insurance companies and such. While not quite what I was expecting, I found it to be a very interesting story, nevertheless. I'm someone who reads speculative fiction as adventure stories set in exotic places. However, the truth is that you don’t have to go very far away or into the past, to find settings just as exotic, if not more so, than a SF one. And I found “old Cape Cod” of fiction, from the 1870’s to the 1920 to satisfy my taste in the strange and exotic.

Most Joe Lincoln books feature orphans, retired ship captains, hardworking widows, shiftless never-do-wells, your odd con man, rich folk down from Boston, and all sorts of other, interesting “individuals” many with strange biblical names. I often say that I like “small stories,” stories about people and everyday life in some other place. I’m not into stories that plumb the depths of human nature. Rather I enjoy light, pleasant stories, and Joe Lincoln delivers; “spinning yarns that made readers feel good about themselves and their neighbors.”

I was fortunate to find a second-hand bookstore that had a good collection of them, and collected any others I found at the Bethesda Fair. So I have a fair collection of his best work -- his early work, in my opinion.

While I’m sure that most of his books are now out of print, save in Gutenberg Project (free) ebook editions and sellers who use those texts, it is surprising to see that two relatively recent little movies were made from his books, the 2009 The Golden Boys from Cap’n Eri: A Story of the Coast and 2010 The Lightkeepers form The Woman-Haters: A Yarn of Eastboro Twin Lights. Danial Adams must be a Joe Lincoln fan.

It is no secret that the stories I write pay homage to the stories I’ve read and have enjoyed in my life. I’ve long wanted to write a story that pays homage to the stories of Joe Lincoln, and his “old Cape Cod.” I had started one, several years ago, but it never quite went anywhere. However, I’ve resurrected it, in a way, in my forthcoming The Secret of the Tzaritsa Moon, and hopefully its sequel that I’m trying to pin down now. While they are not clones of those books, the setting of the stories will reflect those stories, and my family vacations on Wisconsin’s version of Cape Cod, Door County. One of the locales of the story will be a seashore city that caters to seasonal visitors, the summer people. But more on that story soon. For now, it’s hat’s off to Joseph Crosby Lincoln for creating a place far away and long ago that will always be remembered fondly. A place that I can always return to by simply picking a book off my shelves.

October 15, 2020

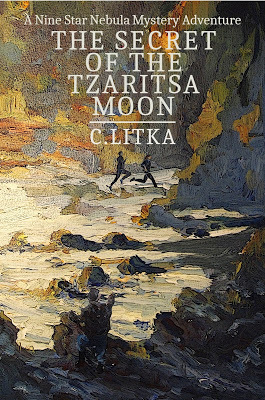

The Cover Art Saga

With a new book coming out, hopefully, by early December 2020, I needed to create a cover for it. Now, I’ve whined in past posts about what a challenge covers are for me, so I'll just say that sometimes they’re fun, but these days they’re just work. However, I’m cheap, and not all that fussy, so I’m my own cover artist. And I just have to lump it. The upside is that I own everything about my creation, from soup to nuts.

For this new story I faced a real problem. All the characteristic scenes that I could draw upon for inspiration take place at "night", and mostly in an old forest, giving this old landscape painter very few options. Plus, given the story’s narrow focus, I’d probably need to include people in the painting as well. Which I’m terrible at.

The lead photo, above, includes my first effort on the 8” of white space leftover on the left of the sheet of paper I used to paint my new cover for Beneath the Lanterns. Which shows you just how enthusiastic I felt about the project. I could imagine a lot of scenes to paint, but I haven't the talent to paint them, so I had to go with something I could do.

The scene I chose takes place in a cliff lined hollow, in darkness. However, at some point there is light flooding from a large cave, that I could use to banish the blackness. As you can see, it pretty much sucked. For my second attempt of the same scene, I tried a different painting technique, a watercolor approach. Below is this second effort. It sucked as well.

I took quick photo of this version in the bad lighting on my drawing table just to see if it was fixable in Gimp using my usual cheats. It wasn’t. So it was back to the drawing table again. On the off chance I could do something with the first version, I took a picture of it as well, and opened it up in Gimp. Serendipity struck.

As you can see, the uneven lighting worked in my favor. The lamp was just above the bright part of the painting, so that area came out lighter than the rest of the painting, giving the painting a glow just where it needed it. And it shifted the color towards the yellow, resulting in something that I found promising. Using my usual cheats I made the art look like it was out of some old school adventure magazine look to it. Great. But.

But, I need some people in it. They could be small, but I needed some sort of action. So I got out my “How to Draw Comics the Marvel Way” book and sketched out a couple of figures. Even with the book, they were bad. Note the theme running through this post. I tried them out -- the ones on the left-- and then decided just to find some clip art runners and trace over them for my figures. Those are the figures on the right.

I photographed them, sized them, and then added them to the background art, along with another figure crouching in the foreground, using a "mask" to make the white spaces around the figures disappear. Voila! I considered adding a few explosions of plasma darts using tools in Gimp, but decided that they’d look out of place, so no one is firing their darter at this moment.

But I still wasn't done. There was the title and author to add. I’ve pretty much settled on The Secret of the Tzaritsa Moon as the final title, rather than The Tzaritsa Moon Mystery, or The Mystery of the Tzaritsa Moon, my other candidates. It’s rather wordy, but old fashioned sounding, which is what I like about it, since it suits the story. It does takeup a lot of space on the cover, if I want the title large enough to be readable on the little thumbnail. I could make the first “the” and “of the” smaller, but at best I’d still have at least four lines, one of which would be only marginally smaller. With nothing much to gain by mixing sizes, I think I’ll keep all the words the same size. It’s not like they cover anything essential. So, behold,the likely final cover for the paperback version of The Secret of the Tzaritsa Moon. The ebook version has the title in a larger font to make it easier to read in thumbnails.

I'm finishing up my second draft of the story, and hopefully my third read through will produce only minor changes and so be ready for proofreading and my beta readers in November. If it all works out, The Secret of the Tzaritsa Moon will be released at the end of November 2020 or early December 2020. I'll be talking more about the story shortly. I will say this, I plant to write a second mystery with these characters and setting as soon as my work is done with this story.

I may not be having fun painting, but I am having fun writing!

October 10, 2020

New Cover Art For Beneath The Lanterns

Blogs are strange things. Basically they’re soap boxes for people who would never think of getting on a soapbox to tell the world all about themselves, what they think, or what they have to sell. I started this blog when I started publishing my stories. It was, and may still be, for all I know, considered an essential element of promoting one’s books. I've my doubts as to it effectiveness in promoting one’s work, since, if you’re preaching to anyone, it's likely the choir -- people who are already interested in your work. But you must have one.

I use mine to publish maps for the ebooks. I think they’re useless in ebooks, since I find them too awkward to use in that format.. And I write about my books, mainly so that when I become famous, after I die, future biographers will have some original material to work with. This is also why I post my paintings – giving some future grad student working on a thesis about my impressionist art, material to fill out their thesis.

Still, nothing I post in this blog is much of any consequence. Alas, I don't have anything important to say. But what I do have to say, I strive to make it somewhat amusing.

Speaking of the inconsequential, I have painted a new cover for Beneath The Lanterns, as seen above. That last cover really started to bug me. This must be the sixth or seventh potential cover I’ve produced for that book. And, by my count, the fourth since I released it, some two years ago. This time around it is, once again, an actual scene, well, sort of, from the book. It is the street known as the Reed Bank.

Below is the original artwork that I used for the cover.

For almost all of my covers, I enhance my artwork on the computer using Gimp, a free Photoshop alternative, adjusting the colors, and adding the black outlines that sharpen up my rather sketch paintings. For many years before I started publishing my stories painting was the focus of my creative drive – mostly impressionist landscape paintings in the last 17 years, and before that watercolors in a rather folksy style. I have, however, run out of steam when it comes to painting, so that painting covers for my books is work – work I’d like done as fast as possible. Plus, I’m not an illustrator, nor someone who cares, or has the talent for, paying attention to details. Which is to say, I'm not a good cover artist. But I'm cheap. So I settle for impressionistic covers that I hope imparts a sense of mood of the story it is illustrating.

And speaking of covers, I have another one to do for my next book, coming soon. I probably should get it done before my next post on that book. Yuk. By the way, I'm thinking of changing the final title to The Secret of the Tzaritsa Moon. We'll see.