K. Lang-Slattery's Blog

November 1, 2025

Remember Kristallnacht

November 9, 2025, is the 87th Anniversary of Kristallnacht

In the dark hours of the night of November 9, 1938, a Nazi-instigated pogrom (a violent attack on an ethnic or religious group with the aim of massacre or expulsion) erupted across Germany and Austria. This intense violence against Jews and the destruction of Jewish property lasted for more than twenty-four hours. Known as the “Night of Broken Glass,” or Kristallnacht, this episode is often cited as the true beginning of the Holocaust.

The pogrom was conceived and executed by radicals within the Nazi party. They used the shooting, and subsequent death, of a minor official in the German embassy in Paris by a Jewish teenager as an excuse for the uprising. Nazi stormtroopers disguised as civilians spearheaded the operation. As the mayhem continued, they were soon joined by many regular citizens.

Between Nov. 9 and November 11, more than 36,000 Jewish men across the country were arrested and sent to the prison camps at Buchenwald, Dachau, and Sachsenhausen. Close to a quarter of those imprisoned in this way died from the brutal treatment in the camps. Most of the rest were released, often only when they promised to emigrate immediately. Additionally, during the violence of Kristallnacht, close to 100 Jews were murdered, many more were injured, and at least 300 committed suicide. While police and firemen stood by and did nothing, more than 200 synagogues were burned and ransacked, and thousands of Jewish-owned shops were looted, destroyed, and covered in hate graffiti.

Though the perpetrators of the violence and destruction were not arrested or punished, men who raped Jewish women during Kristallnacht were arrested for miscegenation (the crime of interracial sexual relations). After it was over, Jewish-held insurance policies and Jewish organizations were forced to pay for all damages.

In remembrance of Kristallnacht, I offer the first pages from my novel, Immigrant Soldier: The Story of a Ritchie Boy. Based on the true story of my uncle, the novel combines a coming-of-age story with an immigrant tale and a World War II adventure. This excerpt recounts the Kristallnacht experiences of Herman, the story’s hero.

TO READ the full book, Immigrant Soldier: The Story of a Ritchie Boy, take advantage of a special discounted price of $13 good for the month of November.

[image error]Immigrant Soldier: The Story of a Ritchie Boy

(The first two chapters)

THE QUIET OF THE EARLY November morning was shattered by loud voices and the screech of brakes. Herman peered through the crack in the stable door. A prickle of fear shot up his neck at the sight of a covered truck, two police motorcycles, and a black sedan in front of the homes across the street. Two brown-shirted SA officers, the Swastika symbols blazing on their armbands, pounded on his cousin’s front door.

Hatred rose in his throat. Nazi Storm Troopers—they were nothing more than thugs, bullies for Hitler and his political party. Two more men in ugly brown uniforms beat at the door of the neighbor’s home where Herman rented a room from the horse dealer and his wife.

The faces of the SA men contorted with anger, and their words polluted the air. “Achtung! Alles’raus! Attention! Everyone out! Get out, you stupid Jews. Wake up! Schnell! Juden! Alles’raus! Schnell! Fast! Jews! Everyone out! Fast!”

The thud of Herman’s heart was palpable. Pain seized his gut. The door of his landlord’s home opened a crack. One of the SA men kicked it wide, and the loud smack of his boot against the wood sent a chill down Herman’s spine. As the Nazis pushed into the house, he heard the confused sounds of loud voices and smashing furniture. An image of the horse-dealer’s wife, beautiful Frau Mannheimer, exploded in his mind, her nightdress ripped, her golden hair gripped in the SA man’s fist. He heard her high-pitched scream leak into the cold morning, and he lurched forward, outside the barn.

He was barely through the stable door when a policeman stepped from behind the black truck. His pistol glinted in the gray morning light, and the sight of the weapon shocked Herman like a jolt of electricity. His wild impulse to be a hero evaporated. He ducked behind the wide doors, angry and ashamed, listening to his heart pound. He pressed both hands against his abdomen and took several deep breaths.

He shook his head to clear it and again put his eye to the crack between the door and the jamb. The policeman must have heard something because he waved his pistol menacingly. He was poised in a half crouch, as if ready to run, and his gaze swept past the stable, down the street, and back again. Finally, he turned and moved toward the open door of the Mannheimers’ home.

Herman inched farther back into the shadows and waited. Less than an hour ago, he had walked to his morning job, the feel of the street cobbles solid and familiar under his feet, his breath visible in the cold air. In the stable yard, blades of stubborn, frost-crusted grass pushed through the trampled earth. He had dipped his fingers into the water trough, breaking the thin film of ice that glistened in the dawn light. The black surface of the water mirrored a reflection of his gray eyes, strong chin, and the curl of dark hair that fell over his forehead. He pushed back the loose hair with his wet fingers and entered the barn.

The warm odor of straw and manure enveloped him. The powerful draft horses moved in their stalls. The soft stamp of their hooves and the bump of their flanks against the boards comforted him like a morning lullaby.

Herman had gone to the tack room to get the curry brush. His motorcycle, which he was allowed to park there, gleamed amid the coils of rope, harnesses, and bridles. He ran his fingers across the shiny black fender, up the rounded shape of the gas tank, and whispered, “Good morning, baby.” For two years he had saved every pfennig, until finally six months ago, as a celebration of his eighteenth birthday, he had gathered his savings and bought the nearly new motorcycle from a local man bound for the army.

Riding gave him a sense of freedom he couldn’t get from any other part of his life. On his days off work, Herman left the cobbled lanes of Suhl and escaped to the countryside, riding from early morning until the long afternoon shadows bled into dusk. At the crest of a hill, he would hesitate, then with a twist of the throttle, speed forward. The sensation when he swooped down the hill lifted his spirits. Sometimes, if the road was straight and flat, he would let go of the handlebars and stretch his arms out on either side like a tightrope walker. The wind pushed against his hands, tugged at his jacket, and battered his face. For a moment, he could imagine he was fleeing this horrible new Germany. On his way home, as day faded into night, the single head-lamp dimly illuminated the road ahead. He felt like a man returning to prison.

Now he stood in the darkened barn and listened to the muffled sounds that came from outside—the thud of boots, the slam of doors, and shouts of “Raus!’Raus!” Above everything, he heard the heartrending sound of a woman screaming, “Nein, bitte . . . nien, tun Sie ihm nicht weh! Don’t hurt him!” He edged forward cautiously and looked outside again.

His cousin’s wife, Hilda Meyer, normally neat and proper, stood in the street in her night clothes, her robe half on, half off, its belt dangling. Her hair stuck out at odd angles, uncombed and tangled from sleep. She moaned as her husband, still in his pajamas, grasped her shoulder, trying to steady her. He moved one hand to cradle her chin and leaned forward to talk softly into her ear. Cousin Fritz, usually funny and full of stories, was serious now. The words he whispered seemed to calm his wife. Herman could see the movement of shadows in the house doorway, and he knew that little Anna huddled there. An impatient SA man clutched his baton and stomped over. He yelled as he prodded Fritz in the ribs with his club. The controlled look on his cousin’s face dissolved, and his eyes grew wide with fear. The storm trooper took no notice and shoved his victim toward the truck. The whack of the stick against Fritz’s back as he scrambled up into the vehicle was muffled by distance, but the sight made Herman flinch as if he had been struck himself.

Two other SA men emerged from his landlord’s door, the horse dealer between them. Herr Mannheimer was shoeless, the long tails of his unbuttoned shirt flapping in the chilly breeze. Blood streamed from a cut over his eye, dripped down his cheek and neck, and soaked into his shirt collar. He seemed dazed, only half conscious, as he clambered into the back of the truck where Fritz grabbed his neighbor to steady him.

The horse-dealer’s wife was nowhere to be seen. Herman bit his lip and closed his eyes as he tried to imagine her hidden safely in the cupboard under the stairs, but the picture that surged into his head was of her body sprawled on the entryway floor, an SA man, his club raised, towering over her. He opened his eyes allowing the stark reality of the street to erase the image.

Herman saw the flash of Anna’s nightdress as she darted out of the doorway, into the street, and clutched at her mother’s thin flannel dressing gown. The little girl buried her face in her mother’s stomach. Hilda’s shoulders shook, and she released an audible moan as she encircled her daughter with her arms.

The sudden thought of his own mother, alone in their home in Meiningen, pushed Herman into action. He jerked away from the barn door and lurched into the tack room. With one kick of his boot, he flipped up the stand of his motorcycle, struggled to wheel the heavy machine into the stable, and with a last glance toward the wide doors facing the street, pushed it out the back to the paddock and a little-used dirt alleyway. With a practiced swing of his leg, he mounted and kicked the engine to life. The powerful machine took off with a surge of speed that lifted the front tire as it jumped over the first ruts. Icy wind blew his cap from his head, but he raced on. The frigid air stung his ears and drowned out the sounds that echoed in his head. He forced himself to think only of getting home―fast.

HERMAN SPED DOWN THE NARROW lane, only half aware of the passage of time. His mind swirled around a vortex of fears and questions. Were the storm troopers pounding on doors only in the little industrial town of Suhl? Was his hometown involved? How bad would it be? What should he do?

He knew it was finally time for him to make a move, but he had no idea how to escape. He was without a passport and no longer considered a citizen of the German nation. He had been declared a Jew, even though he had never worn a yarmulke, lit a Hanukkah candle, or set foot in a synagogue. He knew nothing of Jewish culture or religion, but all four of his grandparents had been Jews long ago, and now that was all that counted in the Third Reich.

The road twisted and turned under him as he sped toward home. He forgot his own safety until he felt the front tire slide in the gravel on a stretch of soft shoulder.

Herman struggled to steady the cycle and forced himself to slow down and think. He could simply veer off the road and disappear into the countryside. The peaceful farms beckoned to him. He could sleep in the stacked winter hay of a barn at night and hide among the tall forest trees during the day. Maybe he could escape to Switzerland, cross the Alps into Italy, and make his way to North Africa, where he would join the French Foreign Legion like the heroes of the books and movies he loved.

Herman shook his head to expel this wild plan, but he could not shake the worried thoughts from his mind. Italy was ruled by Hitler’s Fascist allies. Besides, winter was coming. Freezing temperatures and mountain snow would leech success from an attempt to cross the Alps. And what about his mother? His daydreams came to an abrupt stop. He could not go anywhere without first making sure she was safe. After that, there would be time to try to get a passport and an exit permit, make a sensible plan, and figure out how to survive. Nazi law prohibited Jews from taking money with them if they fled. He tried to concentrate, but there was too much to think about. Could he join the Foreign Legion? How would he pay for passage to North Africa? Could he find work on a tramp steamer? One thing he knew for sure—it was past time to put aside his doubts and leave Germany.

As he neared Meiningen, the road circled the familiar castle-topped hill and approached the Werra River. The steel gray waters of the river slid slowly past the brewery, which used the waterpower to run its machinery. Herman felt his gut tighten. A knot of tension sat heavy in his belly. He slowed the rumbling machine to a workday pace, straightened his shoulders, and surveyed the street ahead for any sign of a police vehicle. He eased past a group of men who had arrived at the brewery gate for the morning shift and started across the wide bridge that spanned the river. His gaze was pulled to the Duke of Meiningen’s palace where the familiar white walls gleamed through the bare trees of the royal park. Behind the palace, an ominous cloud of black smoke rose above the walls. Something burned in the old Jewish section where his grandmother had lived. Two laborers in coveralls paused on their way to work. They pointed toward the smoke, laughing and slapping each other on the back.

He rode slowly across the bridge into town and onto the busy main street that led to the downtown shopping district. Everything seemed normal. A meat delivery wagon maneuvered around a streetcar filled with office workers and shop girls and past the English Garden, where he had often played as a child. Herman gunned the motorcycle and made a right turn from the busy street through the double gates of his family home directly across from the garden. He skidded to a stop in the yard and looked around for anything out of the ordinary. All seemed quiet. He quickly hid his cycle up against the wall behind a hedge and ran up the porch stairs. Relieved to find the big front doors already unlocked, he slipped noiselessly into the entry hall, then bolted up the wide stairs, two at a time, to his mother’s apartment. In this grand home, where she had once raised three children and directed housemaids and a cook, she now lived, widowed and alone, in a small, converted apartment squeezed into half of the second floor. At least she had the tower room overlooking the street. “It is enough,” she had said, “for one very small woman.”

His mother, Clara, though less than five feet tall, had a solid spirit that had always given him comfort. She waited on the landing, her dressing gown loosely tied. Herman could see she had not been awake long. One swath of her hair still hung below her waist, and the dark brown sheen of it caught the morning light. She had only managed to get the other portion of her hair half-braided, and it draped over her right shoulder and across her ample chest. She clasped the loose end of the braid with one hand and reached out with the other to touch her son. “I saw you through the window,” she said, her look steady and calming. “I’m glad you came home.”

Herman, taller than his mother by five inches, enveloped her in his arms. “You’re safe,” he whispered.

“Certainly I am.” She wrapped her free arm around him protectively. “Come inside. We don’t want to linger on the landing this morning.”

Herman entered the apartment, closed the door, looked around at the familiar furniture and pictures, and turned to his mother. “Mutti, something terrible is happening. I left in such a hurry, I didn’t think about anything except getting here to make sure you’re safe.”

His mother carefully turned the bolt on the door. “Of course I am safe.” She slowly finished the braiding of her loose hair as she talked. “I’ve been listening to the radio and the news is bad. It’s you . . . the men . . . who are in danger.” Herman grasped his mother’s hands. “I saw Fritz and Herr Mannheimer being taken. They dragged Fritz directly from bed and into the street. He was still in his pajamas. I saw them beat him.” He sank into a chair. “Herr Mannheimer was worse. His face was covered in blood.” He brushed away tears that threatened to roll down his cheeks. “I should have helped. Oh, Mutti, I didn’t know what to do.” He slumped in the armchair and lowered his head,

his hands over his eyes. His mother grasped his shoulder and with her other hand, firmly lifted his face to meet her gaze. “No,” she said. “There was nothing you could do. You were right to come here.” She turned away and stood by the window but did not pull open the heavy drapes. “Fritz will be all right.” Her voice was firm. “And the horse dealer, too.”

“But Hilda. And Frau Mannheimer.” Herman’s voice broke as he said their names.

She turned back toward her son, and her hand brushed his cheek. “Hush. The women and children are probably safe. It’s the men . . .” Her next words were barely a whisper. “Together we will make it through.”

They huddled all morning in the gloomy apartment,

listened to the radio, and talked in low tones until midday, when their friends downstairs slipped a newspaper under the door. The front-page story proclaimed that the erupting violence against Jews and destruction of Jewish property all over Germany was spontaneous, justified anger over the murder of a man named Ernst vom Rath, a Third Secretary of the German embassy in Paris.

Herman sat wrapped in a blanket in his father’s old chair. The same news droned endlessly on the radio. His head felt dull and a muscle in his temple twitched. He reached over and switched the sound off. “Why, Mutti? It doesn’t make any sense.” His voice broke and he closed his lips to keep his fear inside.

His mother shook her head. “Nobody cares about this man or his killer. It’s an excuse.”

“The boy they’ve arrested is my age,” Herman said. “It sounds like he’s half-crazy because of the deportation of his family to Poland.”

“He’s Jewish. That’s all the excuse they need.” Clara walked over to where Herman sat and touched his shoulder gently. “You must stay out of trouble,” she said.

Suddenly, the strident ring of the telephone intensified the tension. Herman’s mother strode quickly to where it sat on a hall table but hesitated with her hand on the earpiece as it rang a second and third time. “You must never answer it,” she whispered. “No one can know you are here.”

Slowly she raised the instrument to her ear and spoke into the receiver. “This is Clara.” She motioned to Herman to come over and stand with his head close to hers, so they could listen together. She mouthed the words, “Cousin Renata.” He could hear the faint sound of the old lady’s sobbing through the earpiece.

“They took him away . . . my strong Morris, but his heart is weak. He could do nothing to resist.”

Clara’s voice was low next to Herman’s ear as she tried to calm her cousin. “Don’t worry, Renata. All will be well. In a day or two he will return.”

Herman felt his mother’s tremor of doubt.

The voice in the phone rose, the edge of hysteria clear. “What will he do without even his trousers? Only his nightshirt. Barefoot. He will be cold . . . and his heart medicine still beside his bed. I’m terrified. I must go to the police station with his coat and shoes, but all I do is stand here and cry.”

“Be calm. Steady yourself.” His mother tried to make her cousin slow down but she could not hear beyond her own voice.

“And the synagogue! In ruins. Still smoking. I can see it from my window.”

“Stop! Listen now!”

Finally, Renata’s voice was quiet.

“Make a bundle of the coat and shoes and Morris’s medicines. Pull yourself together and go to the station. Doing something will calm your nerves.”

“Yes. Yes, you’re right.” There was a deep, shuddering sob on the phone line. “I’ll try . . . I must try.”

“Call me back this afternoon . . . or any time.”

“Clara, what of Herman?”

His mother laid her finger to her lips and shook her head. “No word from him,” she said into the phone. “But he is resourceful. I know he will be safe.”

“Yes. Herman is a strong boy. I must go now . . . I’ll call again.”

The radio news announced that Jewish men were being pulled from their homes and arrested everywhere in Germany. Repeatedly, Clara tried to telephone Great-Uncle Martin who still lived in the old Jewish section of town, but his phone went unanswered. As the day progressed, the news worsened. Jewish shops were being vandalized and looted. Synagogues across the country burned to the ground while firemen stood by and watched. It was a full-fledged Nazi pogrom.

Herman reminded his mother that the Meiningen police didn’t know he was at home, and if no one saw his early morning arrival, it would be assumed he had been picked up where he had been living. In Suhl, maybe they hadn’t noticed he wasn’t among the arrested, or they simply didn’t care. The family home in Meiningen wasn’t in the Jewish section of town and nowhere near the synagogue. The police had pounded on the door at other times, including several visits in 1936 and 1937—days when they confiscated silver and other valuables—but this day, as Herman huddled in his mother’s small rooms and wondered at the evil in his homeland, the police didn’t knock.

LATE THAT NIGHT, HERMAN returned to where he had abandoned his motorcycle. He lifted the kickstand and straddled the heavy bike, then started the engine as quietly as possible. Slowly, hoping the sounds blended with the noises of late-night buses on the nearby main street, he rode to the back garden, a narrow space between the house and a high brick wall. He pulled a flashlight out of his pocket and turned it on. Its thin beam of light revealed what he looked for—an old, windowless toolshed leaning against the garden wall, overhung by the branches of a fir tree. The dilapidated shed was small, and the roof probably leaked, but in the winter to come no one would need the garden supplies stored there.

Herman parked the cycle near the shed, turned off the engine, and entered, flashlight in hand. He brushed away tendrils of spider webs, stacked a few buckets and a half-filled bag of manure in the far corner, and shoved two hoes, a shovel, and a rake behind a pile of broken terracotta pots. There would be barely enough room. Outside, he straddled the cycle, then with difficulty, maneuvered it backward through the door, carefully turning and cramping the front wheel to make it fit. He positioned the cumbersome motorcycle so it faced the shed door. He knew the effort might save his life. If he ever needed to get away fast, he would be able to get it out and started in a matter of minutes.

In a last gesture, he rubbed his hand across the bulbous gas tank and gave it an affectionate pat. He closed the shed door and turned away. The darkness enveloped him. He walked up the front stairs of his home and into hiding.

Special OfferTo continue reading Immigrant Soldier: The Story of a Ritchie Boy, buy your own copy now. For the month of November, I’m offering the paperback at a special discounted price of $13. Offer good until November 30.

If you prefer to read in a digital format, the eBook of Immigrant Soldier is available on Kindle ($7.95) and is currently included for subscribers of Kindle Unlimited.

The post Remember Kristallnacht appeared first on Klang Slattery.

October 27, 2025

A Mother’s Memory of Her son’s bootcamp graduation.

Some years ago, I took an emeritus class at U.C. Irvine in travel writing. There I learned that a travel essay needs to be more than a travelogue. To grab readers, travel writing should also have attitude. The writer’s voice is essential, as it is through their eyes the reader views the adventure.

I hope you will enjoy (again) this essay I wrote for that class. A Mother’s Memories of Her Son’s Boot Camp Graduation shows that not all travel articles have to take you to foreign places. Written in 2002 and first posted here in 2020, A Mother’s Memory offers a glimpse of our military and the young men who join. Some of the young men in this story would soon be in Iraq. Today, young men like them could be sent to Los Angeles or Chicago. It seems we are now at war with ourselves.

Note: In the first days of September 2002, when this story takes place, it is only a week before the first anniversary of 9/11.

* * * * * * *

THE CROWD IS BUILDING. We come from Texas, North Dakota, Oregon, Idaho, Missouri, Wyoming, Oklahoma, and California — in fact, every state west of the Mississippi River. It is Family Day at the Marine Corps Recruit Depot in San Diego.

A thin man in cowboy boots stands near me, his brown and calloused hand resting on his wife’s waist. She is short and round, her tight jeans pulled in with a silver-studded belt. Between them is a stroller with a sleeping toddler and two sunburned, stair-stepped boys. A large Hispanic family, who must be cousins, aunts, parents, and siblings, cluster together speaking Spanish. A young girl, her hair in tight cornrows, sports a t-shirt with a big red heart and the words, “I love my Marine.”

What am I doing here? I wonder. A Californian, born and bred, surrounded by the cream of the American Heartland. A liberal democrat standing shoulder to shoulder with a man wearing a National Rifle Association cap. A third-generation college graduate thrust among families who, I imagine, believe the military is a road to a better life. Yet, there is a common thread that ties us all together. We wait with anticipation for the first glimpse of the sons, brothers, and boyfriends we haven’t seen in thirteen weeks. My husband and I, with our adult daughter, have come to watch our son graduate from bootcamp.

I love my country for its beauty and its freedoms, but I also carry a vivid memory of the reprimand I got in my first year of teaching for wearing a black armband to commemorate the fallen on both sides of the Viet Nam conflict. I am aware of a cold hard lump waiting to explode in the center of my chest — an uncomfortable lump of fear and disapproval that contrasts with a sense of eager anticipation to see my son and what he has become.

The amplified voice of a drill sergeant pulls the crowd into a patio ringed by Spanish arches. He spews information and instructions about the day and involves some brave mothers in a contest to see who can best replicate the Marine Corps rallying cry. A variety of “Ooh-Rahs,” some high-pitched, some low, at least one (mine) faltering, echo around the patio. “Be sure to get behind the sign with the correct platoon number of your loved one,” the sergeant warns.

Four deep, we jostle for a good picture-taking spot. The platoons arrive, their red and gold flags waving in the sea-blown breeze. My daughter nudges me and whispers, “There he is. I recognize his elbows.” This comment is helpful; there is a oneness to the young men, each one slim and fit in olive-drab t-shirt and running shorts. Only complexion and height offer any clue. My husband points to a figure that seems much like the others, yet something familiar marks him as our son. He does not smile or shift his eyes to left or right―the DIs are watching and notice everything.

Our young man is a squad leader and thus in the front row. For just a moment, pride smothers the cold lump that clogs my throat, and I squeeze my husband’s warm hand. Slowly the recruits begin to move, jogging in place near the sign with their platoon number, while cameras click frantically. Then there is a loud “Ooh-Rah!” and they are off for a swift four-mile circuit of the base.

Following instructions from the amplified voice, family and friends surge toward the theater where we are told the motivational run will end. A holiday atmosphere is being pushed. There is a purveyor of soft drinks, water, and candy. A tall Marine wearing a DI hat that reminds me of Smokey the Bear’s headgear leads Molly, an English bulldog dressed in a camouflage vest, around on her leash. Small children are allowed to pat the dog’s head. Some of us wander over to inspect the seven-foot-high wooden spirit displays standing on the theater steps. There is one for each platoon — all painted with more enthusiasm than artistic talent. I plant my feet behind the barricade and hold a space near the chalked number of my son’s platoon.

The sweating recruits return, and a tall, white-haired commanding officer delivers a welcoming speech. He is lean and fit enough to have run with this new class ready to graduate from basic training. San Diego adds six hundred young men almost every week all year round to the ranks of the United States Marines. The Parris Island Marine Depot in South Carolina trains both women and men and weekly graduates a similar number.

Later during the Emblem Ceremony, the cold grenade in my chest stirs again. It feels as if someone has pulled the pin. The recruits march onto the parade ground in precise formation. Hundreds of them stand in perfectly straight rows, dressed in pressed khaki and olive drab, their close-cropped heads topped with the small boat-shaped hat called a barracks cover. It is less than a year after September 11, and each recruit is entitled to wear the red and yellow ribbon on his breast signifying active service in time of war. Lined up and pinned in red and yellow, not one of them is old enough to remember Viet Nam or any other war. I fear that to these young men war is nothing more than a computer game or a chapter in a history book.

Drill sergeants, assisted by squad leaders, move down the straight rows and present each young man with the black metal Eagle, Globe, and Anchor pin that propels him to the official rank of Marine. Each new Marine proudly fastens the emblem to his own hat and returns to his place to stand at attention. When it is over, we pour out of the bleachers to hug our sons who stand stiff and proud but finally smiling. The air vibrates with military zeal and patriotism, and I allow my sense of impending danger to sink beneath the waves of pride.

There will be exactly six and a half hours of base liberty for the Marines. It is the first real free time they have had since bootcamp began three long months before. Our son leads us around the public areas of the base and explains that the barracks and training fields are off-limits to guests. We pass groups of new recruits still in their early weeks of training. He points out that their pant legs hang loose over their boots. The blousing of camouflage pants into combat boots, he tells us, is a privilege that must be earned. Our son wants to talk of home and hear news of his friends. I want to ask about what he has experienced, but I don’t know the right questions to get more than one-word answers. Even his father, who was never in the military, is tongue-tied with this self-assured young man.

In the end, we sit at a green plastic table in a patio surrounded by the PX and fast-food stands. A Hallmark store does a rousing business selling everything from mugs to stuffed animals, T-shirts to duffle bags, all advertising the Marine Corps. When we order soft ice-cream cones, I smile to hear my handsome, uniformed son call the lady who takes the money “Ma’am.” He did not learn this formal style of address at home.

Too soon the time is over. As goodbyes begin in the orange glow of the setting California sun, I look around. The smooth faces of the new Marines show the confidence and assurance that marks them as men. There are no boys here, though their average age is only nineteen. But the question lingers in the air — where will they be in six months?

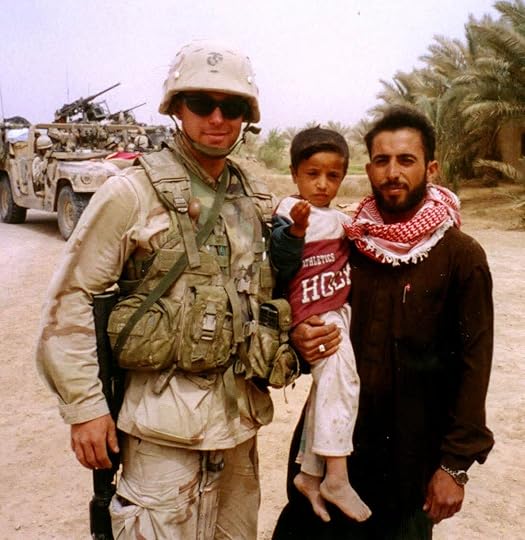

My son in Iraq, 2003

Author’s note: Within six months of his graduation, my son was in Afghanistan as part of a six-man reconnaissance team. After 3 deployments and 8 years in the USMC, he returned to civilian life, attended university, graduated at the top of his computer engineering class, moved to the Pacific Northwest, and has now returned to Southern California to live where he grew up, close to his parents. We count ourselves very lucky.

The post A Mother’s Memory of Her son’s bootcamp graduation. appeared first on Klang Slattery.

October 15, 2025

Chinese Morning

Beijing, 2002

TOM BURST INTO THE HOTEL ROOM. “I’ve found the market!” he said. “It’s just around the corner.” His enthusiasm pulled me out of my jet-lagged stupor more effectively than the two cups of tea I had just drunk.

We had arrived in Beijing the afternoon before. After eating a Chinese meal in a dining room filled with Western tourists and wandering Tiananmen Square in the falling dusk, we fell into bed, heavy with travel fatigue. The next morning, our body clocks still on California time, we were both wide awake as Beijing eased from night into day. My husband, an early riser even at home, decided to explore the neighborhood as dawn slowly crept through the alleyways. I opted for a quiet moment with hot tea and a guidebook.

When Tom burst into the room an hour later, his news energized me. I grabbed my shoes, my camera, and my shopping bag.

Morning mist hovered in the air as we crossed a wide boulevard clogged with bicycles. Thirty years before, we had started our travels together with a two-year journey in a Volkswagen camper equipped with a two-burner stove and a nested set of cookware. We spent uncountable hours shopping for ingredients to accommodate my attempts to duplicate local cuisine. Across four continents, markets were our favorite window into the prosperity and friendliness of local culture. Though we had been to many other places on the Asian continent since then, this was our first time inside China. We were eager for a glimpse of everyday people in a country famous for its cuisine.

After crossing the boulevard, we turned down a narrow lane that dead-ended at another alley. At this T-shaped intersection the world of food began with steam and fire. Steel drums, their hollowed centers hot with charcoal cooking fires, dominated the sidewalk. A tower of aluminum steamers balanced atop the drums and emitted vapors redolent with garlic and ginger. Jostling lines of customers waited for their order of breakfast dumplings.

Tom and I hesitated, our mouths watering from the aromas. Should we join the hungry shoppers? But to our right, the wide-open door of the market building beckoned to us. We worked our way past a clutter of parked bicycles, pushcarts, and cages of live chickens and entered an immense space.

Dimly lit by incandescent bulbs hanging from the high ceiling, the market greeted us with a cacophony of sounds. Shafts of early sunlight lit up the shoppers and vendors who clogged the narrow aisles. Men pushed wagons of produce between rainbow-hued rows of vegetables and fruit. Bent women in plain-colored pajama-style clothing lugged heavy bags and boxes into their stalls. Vendors bagged sales, made change, yelled, argued, and gestured behind counters heaped with goods. The floor was clean and wet from a recent hosing with fresh water, and we had to step carefully to avoid puddles.

On one side of the building, banks of fruit rose almost to the ceiling. It was barely March, early for the variety we saw—watermelons, bananas, mangos, papayas, bright red apples, round Asian pears nested in Styrofoam netting, and citrus of all kinds, including tangerines wrapped in vivid orange tissue. Across the aisle, mounds of vegetables in shades of green, white, and yellow stood in towering displays—firm cabbages, drooping Chinese chives, leafy dark green bok choy, snowy-white giant Daikon radishes, bundles of thin Chinese long-beans, and the knobby green shapes of bitter melon. Tubs of bean sprouts and trays of tofu were arranged next to displays of hunks of bean curd in shades from creamy white to golden brown, fresh, smoked, baked, and pressed. Across the bustling center aisle, dried and powdered things of all kinds filled small specialty shops. Herbs, spices, dried shrimps, and bottles of oyster sauce were stacked on shelves that reached the roof. The air was filled with the blended odors of onions, garlic, citrus, chilies, moisture, and people.

I looked around the market and took in the abundance. So much potential! If only I had a wok and a single burner, I thought. To tamp down my sense of frustration, I pulled out my camera and began to snap photos I hoped would capture the visual essence of the market and remind me of the sounds and smells.

Though we were the only Western faces in the entire market, there was no pushing, yelling, or staring at the foreigners. Everyone was courteous and friendly, from the sweating men pushing loaded carts through the clogged aisles to the vendors and shoppers. The vegetable sellers smiled with pride as I focused for a tight shot of bok choy or snow peas, winter melon or watercress. We bought two pears from a fruit seller, and she grinned broadly at our efforts to communicate pleasure through gesture and smile.

After the produce section, the market widened into a spacious area lined with glass-fronted shops. More wonders surrounded us. Live fish swam in tanks, and glistening fillets of salmon and white fish lay on a clean marble counter. Nearby sides of lamb and beef hung from hooks, and two men in the white caps of the Moslem minority butchered them, creating shank, rib, and loin cuts. At another stand, two men and a woman were busy making fresh noodles and a kind of round flat bread. We stood, stomachs rumbling, and watched the bread being rolled out and cooked on a griddle. Both the bread and noodles were selling as fast as they were made. A pretty girl stuffed the yummy-looking products into bulging plastic bags and handed them to shoppers who stood patiently in line.

[image error]Across the shed, plucked birds were displayed in lines, pressed wing to wing, waiting to be chopped for stir-fry. One narrow-breasted, black-skinned bird lay surrounded by other lighter chickens. We wondered, “What is he?” I have since learned that these skinny, dark-skinned fowl are prized for their flavor. The aromas and sights made me long to fill a shopping bag. If my van kitchen had been waiting for me, I would have bought the black fowl and made soup that evening. I was both thrilled by the sights and sounds and disappointed to be unable to participate.

[image error]Tom looked at his watch and pulled me away from the poultry display. “We have to go,” he said. “We’ll miss the prepaid breakfast at the hotel.” On our return through the market, we could not resist a stop at a glass-fronted bakery. We walked away clutching a small bag of crisp, seed-studded rolls. We slowed down in the produce section as well and purchased two Asian pears from one of the smiling vendors. She grinned broadly at our efforts to communicate pleasure through gesture and smile. Finally I had Chinese groceries in my string shopping bag, a souvenir from France purchased thirty years before.

As we headed back toward the hotel, the aroma from the steamers on the lane called to us. The lines were shorter now, and we looked longingly at the row of dumpling sellers.

Suddenly neither of us had any interest in the breakfast in the hotel dining room. Tom grabbed my hand, and we shouldered into the queue near one of the steamers. We pointed to our choice, nodded, and smiled. I held out my hand and allowed the vendor to select the coins he wanted. Unable to wait, we stood on the sidewalk at the edge of the road and savored each bite of our fluffy white steamed buns. They were hot and succulent—a layer of light dough enclosing a tangy filling of chopped pork, leeks, and garlic. I peeked into the brown paper bag of pastry we had bought earlier. “Shall we?” I asked, and Tom nodded. The flaky rolls were still warm, sweet, and rich with a crust of sesame seeds. Each bite made us less interested in the hotel breakfast waiting in the dining room.

[image error]We fell in love with China on that first morning as we wandered the Beijing market. The people were friendly, the country galloped toward prosperity, and, best of all, Chinese food was ample and lived up to its reputation. My only disappointment was that I was unable to cook a meal using freshly bought market treasures in my own tiny VW kitchen.

[image error]If you enjoyed this short travel story, you might also enjoy my travel memoir, Wherever the Road Leads, about our two-year, four-continent journey in a VW van in the 1970s.

The paperback edition is ON SALE NOW at a special discounted sale price of $13 for my followers. This discount is only available until November 8, 2025, so be sure to get Wherever the Road Leads while the special offer lasts! To get your copy, follow the link below:

https://shop.ingramspark.com/b/084?params=51UsJsPd64nPCi0aGyyoHWQpksTR0XolMb9443lMqYA

The post Chinese Morning appeared first on Klang Slattery.

October 7, 2025

My Research Addiction

And a Word About Fact-Checking.

MY LOVE OF RESEARCH COMES from childhood. I was raised in a home where the Encyclopedia Britannica held a place of honor. I spent countless hours sitting cross-legged in front of the bookcase poring through the heavy maroon-colored volumes. My children were brought up in the same tradition. Now we turn to our smartphones and the world of the internet when something stumps us—our mantra has become “Let’s Google it!”

Given my compulsion to look things up, it is no surprise that I am a writer of historical fiction, a genre that uses fact as its bedrock. No matter the era or the setting, writing in this genre requires the author to be a dedicated researcher.

The trick is to not wander too far from the goal: once I spent over an hour on the internet when all I meant to do was double-check the date that buzz bombs were first sent against London.

I research before and during the writing of my novels, creating a surplus of facts. What I don’t use, I stash away in countless files, “just in case.” Even after my book is finished and being proofread, I can’t stop myself. I might find some illuminating details I can fit into the narrative or correct an error only an expert will notice.

As a writer, I must be careful not to dump too much detail into the story. No matter how much research I do, in the end I can only use what helps me weave an accurate representation of the period. If a fact serves no purpose and slows the momentum of the plot, I cannot use it.

And what I do include must be accurate. I know that even a small historical error can put all my laboriously acquired research in doubt. I double-check everything, even things I’m sure I know. Luckily, the internet makes instant fact-checking easy.

Recently, while proofreading my novel Ashes and Ruins, I found one of those dreaded little errors. The line was: “Three coupon [ration] books, including Hazel’s valuable blue one that allowed her to get extra milk, must be checked.” Wait a minute! Wasn’t the ration book image on the cover design green? Which is right?

I asked my search engine the question: What color were British ration books for children during WWII?

The response: “British ration books during WWII were color-coded by age and need: green for children under five (and pregnant/nursing mothers), blue for children aged 5-16, and tan for most adults.” Further checking on various British Museum websites confirmed the colors.

My child character Hazel is only two at the time, so her ration book would be green, not blue! The text was wrong, though the cover design was correct. Such an inaccuracy, though tiny, could result in cracks in my story’s overall credibility.

As a meticulous fact checker of my own work, I sometimes notice errors in other books I read. Recently I came across several passages in a novel that described a hummingbird in an Italian garden in 1900. Wait! Hummingbirds are only found on the American continent! I knew this because years ago, Danish guests expressed their excitement and thrill to see hummingbirds for the first time in my Southern California garden.

With the help of the internet, I double-checked and found the following choice morsel: “True hummingbirds are not native to northern Italy or anywhere else in Europe, Asia, Africa, or Australia; they are exclusive to the Americas. However, you may see a hummingbird hawk-moth in northern Italy, a type of moth that resembles a hummingbird with its rapid wingbeats and hovering flight while feeding on nectar.” Naturally my compulsion led me to search for hummingbird hawk-moths, and, of course, there were pictures. It is amazing how much those moths look like our beautiful American hummingbirds.

If the subject matter of a book lies within my area of expertise (say, the German Jewish experience during WWII), an error can grab me and lift me out of the story. Recently, in the first chapter of a book I read, a major character, a young Jewish girl preparing to flee Germany in May of 1939, complains of being forced to wear cloth stars on her clothing. This is off by at least a year, I thought. The Nazi law requiring all German Jews to wear the yellow star did not go into effect until the fall of 1941. So how could this character complain about it in the spring of 1939?

Of course, though factual errors from pre-war Germany jump out at me, most readers won’t notice them. Yet, I live in dread that someone with more expertise than I will find a tragic flaw in my finished book. For this reason, I often use fact checkers. The late Ritchie Boy and Holocaust expert, Guy Stern, read my earlier novel, Immigrant Soldier, in search of errors, and another Ritchie Boy checked the German phrases I used in that novel.

Recently, a good friend, a woman born and raised in Great Britain, read the London sections of my new novel, Ashes and Ruins. I asked her to root out anything that didn’t seem consistent with British culture. She told me that unless accompanied by sausage (bangers), mashed potatoes are called just that—not mash. She also explained to me the importance of class in Britain and pointed out that my middle-class family would probably own a laundry tub and a wringer rather than wash their laundry (including linens and diapers) in the claw-footed bathtub. My friend’s comment led me to research laundry tubs of the 1930s.

After more than an hour on the computer, I ended up with two changed sentences in the manuscript, a small document on old laundry practices, and a lovely collection of photos of antique washtubs and 1930s washing machines—so more surplus research data.

[image error]After a childhood friendship with a set of encyclopedias, I am now devoted to the internet as my research guru—everything from Google to YouTube, Wikipedia to Claude. Of course, these sources lead me to deeper research in nonfiction books. By the end of any project, books bristling with sticky notes dominate my bookshelves, and dozens of files fill the research folder on my computer.

My constant research leaves me with hundreds of fascinating facts that will not work in my current novel or short story. I love finding out all this stuff and most of it’s too interesting to consign to the recycling bin on my desktop. What to do?

I have a plan. Keep an eye out for future historical articles about great tidbits that never made it to the pages of Ashes and Ruins. Some with pictures!

The post My Research Addiction appeared first on Klang Slattery.

September 26, 2025

The Memory of Smells

PETER NOTICED THE SCENT of lavender first and looked up from cleaning the meat slicer. The young woman peered into his glass case. Under her loose dress, her pregnant belly was noticeably bigger than the last time she came into the shop.

“Please, Mr. Whitacre,” she said. “I’d like two of those lovely white chicken cutlets today.” She pronounced the Ws like soft Vs. The sound of it reminded him of his wife.

Peter Whitacre had brought a German speaking wife back home to England after the great war.

Early in the spring of 1917, he had been pulled from the front-line trenches in Belgium to work at the triage center officially known as the Casualty Clearing Station. Some officer had decided a butcher would fare better amidst the carnage of body parts. He had been wrong, of course.

Peter was assigned to clean up the surgical tent whenever it was not filled with intense doctors and screaming patients. Gathering up the severed limbs, the buckets of blood and bone fragments, sorting the bloody sheets from the cotton wads saturated with human fluids, wiping down the surgical table, and sluicing the duckboards with buckets of muddy water―these things he could manage. The smells were what turned his stomach. The rank odor of sweat mixed with the metallic smell of blood. The putrid stink of gangrene oozing from wounds. The foulness of loosened guts, urine, and vomit. The pungent, acrid smoke from burning flesh that rose from the incinerator where discarded limbs were burned.

In the evenings, his stomach sour, Peter could not bear to enter the mess tent. While others ate, he walked into the surrounding countryside. He breathed in the cooling evening air. The aromas of pine and forest loam calmed his stomach, allowing him to sleep. For weeks, he ate only the morning porridge and gulped down countless tin mugs of watery coffee.

One afternoon, when the field hospital was quiet between battles, Peter found an abandoned bicycle at the edge of camp and commandeered it. He peddled along a dirt road between uncultivated fields. Amidst the weeds and grass, bright red poppies nodded in a gentle breeze. A line of trees marched in the distance, promising a stream or irrigation ditch. When he arrived at the trees, he leaned the bicycle against a wooden fence. He heard the gurgle of water below and followed the sound. At the bottom of the gulley, he stepped into sunshine.

Before him a stream curved around a boulder and formed a sandy-bottomed pool. The water sparkled like diamonds and the wet, woodsy smell of moss filled his nostrils. On the bank, a young girl lay, one arm under her head as a pillow, the other holding her bunched skirts above her knees to expose her legs to the warmth of the sun. Her face was turned toward him, her eyes closed as if in sleep, and a jumble of dark curls spread over her arm. Peter realized he was staring and he cleared his throat. The girl startled and pushed her skirts down. She jumped to her feet, her blue eyes wide with fear, but she didn’t run.

“I’m sorry, I didn’t mean to scare you,” Peter said. The girl continued to look frightened. Peter spoke no French, but he knew a little German, taught to him by his paternal grandmother who had come to England to work as a cook’s assistant. At the kitchen door of the estate of her wealthy employers, she met the local butcher and never returned to her homeland. Peter cast back into his childhood memories and found the words he hoped would work. “Es tut mir leid,” he mumbled. “Nicht verletzt. I won’t hurt you.” He held his hands open, away from his body, and smiled.

The girl’s stance relaxed, though her eyes remained wary. “Du solltest dich nicht anschleichen. Du hast mir Angst gemacht,” she said.

This was way beyond Peter’s rudimentary German. “Es tut mir leid, I’m sorry,” he repeated. He hunkered down on his heels some distance from where she stood and tried to appear unthreatening. He trailed his fingers in the cool water and gazed into the depths of the pool. A small swarm of minnow darted about in the shadow of a rock. He pointed at them. “Fisch. kleiner Fisch.”

“Englisch?” she asked.

Peter nodded. “English.” He pointed to his chest. “Peter.”

Finally, a small smile. She laid her open palm on her breast. “Nadine.” Her voice was soft, and the sound caressed his inner ear.

That was how it started.

The second time he saw her, she was picking late summer berries from the brambles along the road. He allowed the bicycle to coast as he passed her and called out, “Guten Tag, Fräulein.” She turned and lifted her hand in greeting. He swerved, almost going into a ditch before he could stop the forward momentum of the bicycle.

Nadine walked toward him and held out her basket. “Probieren Sie doch mal eine Beere.” She motioned with stained fingers toward her mouth. “Please. You taste,” she said hesitantly. Her lips were purple with berry juice.

From that moment, Peter’s heart was hers.

Born and raised in Belgium, Nadine spoke French as well as German, and with Peter’s help she quickly learned enough English words for their needs. By fall, they were meeting most evenings. Nadine delighted in riding pillion on the back of the bicycle. Her curls blowing in the wind, she clung to Peter with one arm and flung the other out in abandon. As darkness enveloped the countryside, they found a quiet spot where they could cuddle―talking and kissing, until kissing was not enough. The mossy bank by the pool, the place they first met, was also where they first made love. In November, they married in the village church and later that month, when Peter was mustered out of the Army, they returned to England as husband and wife.

The country town in Surrey where Peter had been raised seemed too provincial for a man who had seen Europe. He grew tired of the gossiping old ladies and their snubs caused by Nadine’s German accent. The young couple were still newlyweds when they moved to London. In the polyglot neighborhoods of the big city, they blended in.

With the help of his parents and a war loan from the bank, Peter opened his butcher shop in a pleasant part of East Chelsea. They lived upstairs over the shop and together they were happy.

Sometimes the smell of blood from the carcasses and the crunch of bone as he sawed through a haunch of beef bothered Peter. It brought visions of his war work at the medical station to the backs of his eyelids. At the end of the day, he could not stand his own apron covered in red smears.

Nadine sensed his discomfort. Each night, she scrubbed the chopping block and the counters and wiped down the meat case front and back until the glass became invisible. She laundered his aprons, rubbing them vigorously against the washboard, beating the stains into submission. She made sure there was always a stack of spotless aprons in the back room, ready for Peter to change into whenever his bloody apron threatened to unnerve him. Each morning, when he went downstairs to open for business, the shop exuded the lingering smells of bleach and vinegar. Gradually, his flashbacks ceased to trouble him.

The smells Nadine created upstairs were homier―the aromas of cinnamon cake and stews seasoned with rosemary and garlic wafted from the kitchen. The comforting scents of mint and lavender clung to their bedding and surrounded their nighttime kisses. Later there was the sweet smell of baby talcum and milk. Then the family smells of burnt toast, damp mittens, and little boy farts. As their son grew, the scent of his sandalwood pomade lingered in the bathroom, and the fragrances of rose and jasmine from his girlfriend’s perfume clung to his shirts. Too soon after their son left for university, the odors of illness pervaded the rooms―medicines, rubbing alcohol, and lingering sickness. And then Nadine was gone. They only had twenty years together. It was not enough.

Peter drew a deep breath and forced his mind back to the present. He wrapped up the chicken cutlets for his pregnant customer. Her accent had reminded him of Nadine. He had heard her hissing Vs before. “Do you like bratwurst?” he asked as he rang up her purchase.

The young woman looked at him in surprise. Then she lifted her chin. “Yes! Of course. But I haven’t tasted them for years.”

“I’ve just made a batch,” he said. “My wife’s recipe. I make them for myself, not to sell . . . I’d be pleased to give you a couple.” He went to the back room, brought out two thick sausages, wrapped them in paper, and handed the package across the counter. “My gift,” he said.

The woman’s smile lit up her eyes. “Brilliant! Thanks ever so much.” She reached up to offer him her hand. “I’m Edith,” she said. “And you are definitely my favorite butcher!”

After she left, Peter turned the sign on the door and pulled down the shade. He returned to the back of the shop and picked up the bowl where four plump bratwursts remained. He stared at the glistening sausages and allowed his mind to drift back to a day when he was still a young man ― his business new, his wife by his side. He could almost smell the bleach as Nadine scrubbed the chopping block while he stood at the meat grinder feeding scraps of pork and pork fat into the machine with the wooden pusher. Sausages were a popular item for his customers’ leisurely weekend breakfasts.

Nadine came up behind him and wrapped her arms around his waist. “I don’t care for your English sausages . . . too bland. Too much bread-crumb filler.”

He turned and playfully swatted her away. “What would you have me make?”

“In Belgium, we favored the French Boudin Blanc made with veal, chicken, and cream. A bit dear for sausage. But my favorite is the German Bratwurst we used to eat when we went on holiday to visit my aunt in Frankfurt.”

“My customers like what they’re used to,” Peter said. “You know the British won’t want something la-de-da French . . . and certainly not Boche food.”

Nadine touched his chin. “What about us?” Her voice was like silk. The clean soap scent of her skin engulfed him, and her lips brushed his neck. “Come, darling. I’ll show you my aunt’s secret recipe. You’re not afraid of European food, are you?”

Peter reached behind her and cradled her rounded bottom in his broad hands. “Not at all, sweetheart,” he whispered.

This time, it was Nadine who swatted his hands away. “Later, husband. Now we will make sausage. I must get spices from my kitchen. You continue grinding. Please, add a few meatier chunks if you can spare them. And no breadcrumbs until I return to measure them myself!”

Moments later she returned with a basket of spice jars. One after another she added brown and gold powders to the mix of ground meat. Pepper, ginger, marjoram, dry mustard, cardamom, coriander, mace, and, at the very end, a sprinkling of crushed caraway seeds. Peter had no idea his wife had so many different seasonings in her cupboard. The butcher shop smelled like a Moroccan bazar. Later that evening, their kitchen was redolent with the rich aroma of sizzling pork and spices.

Peter shook the memory away and slowly climbed the stairs. He set the bowl of sausage on the table and wiped his eyes. He lifted Nadine’s favorite iron skillet from its hook, set it on the fire to heat, and put two sausages in the pan. As they began to sizzle, the aroma of German Bratwurst filled the room, and Peter felt his wife by his side.

The post The Memory of Smells appeared first on Klang Slattery.

September 16, 2025

Editing 1, 2, 3

EVEN MORE THAN THE PROCESS of writing a first draft, I actually enjoy editing. For me, editing in all its phases is akin to polishing and refining a rough gemstone until it shines.

Like any craftsman, I take the work one stage at a time, gradually changing my manuscript into what I hope will be a jewel worthy of my audience. The progressive stages of editing range from looking at big-picture issues to checking grammar and punctuation. Each step leads me closer to a finished product.

As in all things that lead to a finished book, editing is not a solo process— it is a team effort that includes my editor, my beta readers, and myself.

The names of the different stages and types of editing can be confusing, but each has its special role in creating a manuscript ready for publication.

Developmental editing (also sometimes called substantive or content editing) begins after the first draft of the manuscript is complete. This first-stage editing evaluates the story’s organization, plot, character development, narrative flow, pacing, and other overarching issues. Some authors use beta readers to evaluate these things or a combination of beta readers and an editor.For Ashes and Ruins, I used beta readers for the first section (Book I takes place in Germany) and my editor for the full manuscript when it was completed. My beta readers and my editor agreed that the diary sections of the manuscript weren’t working. Also, several plot lines needed clarification. This input led to months of rewriting.

Making the diary entries more accessible to the reader was the most difficult task for me. I have never actually kept a diary and felt at a loss. At my editor’s suggestion, I reread The Guernsey Literary and Potato Peel Pie Societyand sections of The Diary of Anne Frank. I was elated when, after reading the reworked manuscript, my editor wrote saying, “What a difference! It’s interesting, balanced, and flowing!

Line Editing (sometimes called copyediting)is the second step in the editing process. It tackles writing style, language use, readability, sentence structure, word choice, clarity, and tone. A good editor can help with all these things while allowing the author’s distinctive voice to remain. This phase also deals with grammar, punctuation, and consistency and ensures the writing conforms to the rules of a style guide, such as the Chicago Manual of Style , a publishing industry standard.For me, this is the fun part. I start the process myself by searching for overused words . . . and I have quite a list of words I use repeatedly in my first drafts. With the help of Microsoft Word’s “find” function, I root them out and replace them. Just (this word is my personal worst offender) can be replaced with simply, merely, only, or (just) deleted. Large transforms into gigantic, huge, massive, vast, substantial, ample, spacious . . . and it can also often be deleted. My editor finds more problems to correct―repeated words, confusing sentences, puzzling descriptions. I love how each improvement makes a positive difference.

Most publishers have their own style guide rules used in conjunction with the Chicago Manual of Style. As an independent publisher, I can decide on a few style rules of my own. To make a clear distinction between the narrative text and the diary entries in Ashes and Ruins, I created two different sets of rules. The diary, understood to be written originally in longhand by a young woman, has no quotation marks or italics and uses OK rather than okay. The narrative segments, on the other hand, utilize standard style guidelines more strictly.

At this stage, my two previous books were submitted to an additional editor for a fresh set of eyes. The “backup” editor read the manuscript as a kind of combination copyeditor and proofreader. However, for reasons unknown (impatience? overconfidence?), I skipped this step with Ashes and Ruins. This was a mistake! So many things that could have been caught by “fresh eyes” ended up in the PDF created by my book designer.Making edits in a PDF is more complicated and involves the book designer having to incorporate the actual changes into the file. I will not neglect this step in the future.

(see post “Inside a Book” https://kathrynslattery.substack.com/p/inside-a-book).

Proofreading is the final stage of editing. It should catch typos and spelling and formatting errors―all the little things that can slip by even when (or especially because) one reads the manuscript over and over. Proofreading usually happens after formatting and before the file is sent to the printer.Finally, after two read-throughs by both my editor and myself, we have completed the arduous task of proofreading the book design PDF. Ashes and Ruins is finally ready to be printed as an ARC (advance reader copy).

The ARC, an actual prepublication facsimile, will undergo additional proofreading by myself and a dedicated proofreader to catch any remaining tiny errors. The ARC (or an eBook facsimile) is the format sent to potential reviewers, accompanied by a note that indicates it is not intended for sale and may still contain typographical and layout errors “not to be present in the final book at release.”

Editing a book to make it “publication ready” is a long and complicated process. Even the most vigilantly edited books can end up with errors that were missed by every member of the team. In some ways, computers and digital publishing have made editing simpler, but the ease of moving things around also makes it more likely for little errors to remain behind.

How many times have you read a book or a magazine article and found a stray typo or missing word? Some sources say that one error for every 10,000 words is an acceptable target for a clean, professionally edited book. So, if a few editing mishaps remain in a full-length novel, a reader can still rest assured that the editing team worked diligently to make the book as flawless as possible.

Now on to the next step: asking for reviews!

The post Editing 1, 2, 3 appeared first on Klang Slattery.

September 8, 2025

A Man In Love With His Wife.

Sicily, near Palermo. 1972

We met Albert and Rosalia fifty years ago, and our few minutes of friendship shine in my memory. Tom and I were on the honeymoon of a lifetime, living in a Volkswagen van and traveling from one continent to another, from one country to another. Twenty-four hours before, we had endured a long and rough crossing from Tunisia to Palermo. Exhausted, we stumbled off the ship and stood in line for Italian customs. Once in our van, we located a local grocery to buy supplies and a gas station for fuel, chores that were always an exhausting adventure in each new country.

It was already late afternoon when we drove out into the countryside to search for a place to park the van and sleep. Bone-weary, we took the first farm road we could find and settled on a quiet loop surrounded by fields. After a quick meal, we collapsed on our bed as daylight faded into dusk. We did not stir until the following morning.

We awoke to bright April sunshine edging through the curtains. The camping spot we had found in our sleep-deprived stupor was near a bridge over an irrigation ditch. Fields and farmland stretched out on both sides. From our bed, I reached across to our two-burner stove, and like every morning, I put the kettle on to boil. Tom opened the van door to let the spring sunshine bathe us in its warm glow. It was the glorious kind of morning that made the stress of constant travel worthwhile.

Before the water for my tea and Tom’s coffee came to a boil, he heard the chug of a car pull up next to us. A dusty Volkswagen bug had stopped near the bridge, and three men emerged. Two walked to the bridge and knelt to check a gauge that hung down into the flowing water. The third man was blond and stocky, a picture-perfect Sicilian. I hoped he had not come to chase us away from this idyllic spot which was certainly private property.

The man came to our open door. “Hello,” he said. “American?”

Tom stepped down from the van. “Yes, Americans. California.” We found almost everyone we met, even country people, knew of California, home to Disneyland and Hollywood.

“La mia tera. La mia Fattoria.” The man swung his arm in an arc toward the fields bordering the road and the structures in the distance. “Ben venuto.”

Tom smiled and offered his hand. The farmer grasped it firmly in both of his and pumped it up and down slowly. “Sorry. No Italiano,” Tom said. “Español?” He pointed to me. “Mi mujer, Katie . . . esposa.” He touched the wedding ring on his finger, then put his hand on his chest. “Tomas,” he said.

The young farmer touched his chest with the flat of his palm. “Alberto.” It was obvious we had no language in common, but Alberto’s broad smile spoke of our welcome. He peered into the van, obviously curious. “Per favore. È la tua casa?

I understood the word “casa” and invited him inside with a gesture. Alberto stepped into our microbus and looked around, his eyes wide. I pointed out our built-in amenities—a stove, a tiny refrigerator, a sink with pressure-pumped water, our wide, foldable bed, and the small closet. I hoped that my limited Spanish would sound close enough to the Italian that he spoke. “Estufa. Lavabo. Agua. Bed for dormir. Closet . . . para ropa.”

Alberto looked around and nodded his head in appreciation of each item. When he had seen everything, he stepped out of the small space. “Grazie,” he said. He looked back and forth between Tom and me. I caught his glance at my flat stomach. “No Bambini?” Alberto asked. We understood this and would soon learn it was one of the first questions most Italians asked.

Tom laughed and shook his head. “No Bambini.” He pointed again to his gold wedding band. “Solo ocho meses.” He held up eight fingers to show the number of months we had been married.

The farmer smiled and pointed to himself. “Si, a me, otto mesi.” He also held up eight fingers and pointed to the ring on his left hand. “La mia donna. Con il bambino . . . presto!” His face beamed with pride for his impending fatherhood.

I spread my arms to encompass our tiny home. “Very pequeño, too small . . . para un bambino,” I said. Alberto seemed to understand my mash-up of English and Spanish because he nodded again and laughed.

His compatriots finished checking the gauges and the irrigation ditch and came over to the van. They stood by the door, and Alberto spoke to them in lilting Italian. They smiled in unison and stretched out their hands in greeting. “Bye. Bye,” Alberto said, and they all climbed into their VW bug and rumbled off down the dirt road.

I sighed in relief. We had not been told to leave. Our first glorious morning in Sicily stretched ahead.

With our bed folded away, Tom and I sat at our tiny table, sipping from steaming mugs, enjoying the earthy smell of farmland and the volcanic slopes of Mount Etna in the distance. We were still talking dreamily of our plans to see the nearby ancient Greek ruins when Alberto returned. This time his companion was a pretty, young woman whose pregnant belly filled her loose dress. Our friend put his arm around her waist and grinned. “Rosalia,” he said. He tenderly touched her swollen abdomen and added, “Bambino.”

Rosalia smiled shyly and offered us a bottle of milk with one hand, four eggs cradled in the other. Her husband spoke for her. “Per te. Un regalo.” He made the hand gestures of milking a cow, pulling on invisible cow teats, then grinned, and pointed to the eggs. “Uova. Cluck. Cluck. Polli?”

“Si. Grazie.” Tom assured him we understood. “Pollo en Espanol. Chicken in English.”

Alberto whispered in his wife’s ear. She went back to the car and returned with a photo album cradled in her arms. She smiled shyly and held it out for me to take. “Foto del matrimonio,” Alberto said.

Tom and I both understood that the couple wanted to share these mementos of their wedding with us. We perched together on the threshold of the van and looked through the photos—a beautiful Rosalia with flowers in her hair and Alberto in a black suit beside her, the two of them holding hands on the church steps, and several shots of family and friends seated at a long table under a grape arbor. The album continued with countless pictures of guests dancing or raising glasses of wine in a toast. The pictures brought back memories of our own garden celebration, and Tom squeezed my hand as we turned the pages.

When we had finished looking at all the photos, I handed the book back to Rosalia with both hands as if it were a sacred offering. I treasured her willingness to share as much as she treasured the album itself. “Thank you,” I said, “Grazie.”

Alberto and Rosalia smiled, and their eyes glistened with love and hope. “Arrivederci. Andare con Dio,” Alberto said. Rosalia only nodded. In her shyness, she had not said a single word. Alberto waved his hand gaily as he drove away, and Rosalia’s glowing smile shone through her window. Tom and I watched the little car rumble down the road, a swirl of dust following as it turned toward their home, a place we knew had a cow, chickens, and a grape arbor—a place filled with love.

I have thought of Alberto and Rosalia often over the years, and I wonder how their marriage fared. Did this Sicilian man love his wife with continuing devotion, or did his eye begin to wander to younger women? Did Rosalia remain the silent acquiescent partner we saw, or did she become a domineering and opinionated woman, directing family matters with a firm hand? I will never know what path their marriage took, but I’m sure that however their relationship evolved, they are still together. For Alberto and Rosalia, deep in the Sicilian ethic of lasting marriage, divorce would not have been an option.

My marriage, so happy and filled with hope during that traveling honeymoon, ended after thirty-one years. Tom and I did have bambinos, a daughter and a son, a dream of family we fulfilled together. But after both good and not-so-good years, we divorced when we realized that we were at our best as a couple only when traveling. As it turned out, we were not so well suited when it came to the day-to-day give-and-take of homebound life with children. Still, Tom and I have remained friends, and we often remember together the joys of that long-ago honeymoon trip.

When I think of our Italian friends, I remember how Alberto radiated with love for his wife, for their coming bambino, for his farm, and for the country life they shared. I hope he and Rosalia never longed for anything else. I like to close my eyes and picture them today as one of those long-married couples of romantic lore—an elderly man who still adores his wife and a doting wife who defers to her husband and offers hospitality to strangers.

In my imagination, they have recently celebrated their 50th wedding anniversary with a party under the grape arbor. Perhaps Rosalia has made another picture album. There will be photos of Alberto seated in the shade, his hands clasped on the curve of his cane, and another with Rosalia seated next to him, their shoulders touching and their hands clasped together. Their faces glow with smiles that break apart the wrinkles of age. There will be pictures of the two of them surrounded by their adult children, certainly more than one, all in their mid-to-late 40s. In other photos, their grandchildren, teens and adults in their twenties, fiddle with their cell phones or raise glasses of wine. Most likely, there will be great-grandchildren pictured too, young ones kicking soccer balls or hanging on their grandpa’s knee.

How I envy the dreams those two probably fulfilled! They were our friends for only a moment, but they showed me a glimpse of a simple life overflowing with love and grandchildren—something Tom and I hoped to find, but our story turned out differently.

. . .

A Man In Love With His Wife was inspired by a section of my memoir, Wherever the Road Leads, published in 2020. Originally shorter, the memory has been expanded with details and reflection. If you enjoyed A Man In Love With His Wife, you might also enjoy reading the full memoir.

https://www.amazon.com/Wherever-Road-Leads-Memoir-Travel-ebook/dp

The post A Man In Love With His Wife. appeared first on Klang Slattery.

August 29, 2025

Inside a Book

Book design is the graphic art of determining the visual and physical characteristics of a book. (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Book_de...)

Open a book, and what do you see? Words. There may be illustrations or a map, but most of all there are pages and pages of those wonderful words and sentences we writers labor to place in ways that convey feelings, ideas, characters, and places.All those words inside a book don’t just fall by themselves into pleasing, easy-to-read fonts arranged in paragraphs and chapters, with page breaks, chapter headings, and page numbers marching along in sync. Making sure a book’s interior suits the story and genre is as important as creating an appropriate and eye-catching cover. Decisions need to be made. All this is the collaborative task of the book designer and the publisher.

Recently I have had to set aside my writer’s cap and put on the hat of a publisher. In previous posts, I’ve talked about book covers and genres. As a self-publisher, the most difficult task is making the multitude of necessary decisions about my book’s interior. The countless possibilities and variations are overwhelming. Luckily, I have a wonderful book designer who has worked with me on all my published books. Lorie is experienced, competent, and patient (she must be, as I ask to see countless variations and new samples.) Lorie knows her stuff.

To begin the process, I send Lorie a description of the book’s story, including the genre (yes, that again), and segments of the manuscript, including the title page and sections that will need special treatment. With that input from me, Lorie creates preliminary samples. We both knew this is only the beginning.

[image error]Back-and-forth emails begin to arrive on a regular basis. I study the samples and send a list of the things I like in each—the placement of the page numbers in one sample, the layout of the epigraph in another, the fonts in both, and so on. Next, Lorie creates a composite that includes all the things I like in a single example.

Still more fine-tuning. We try several other fonts. We switch the page numbers from the bottom of each page to the top. As Ashes and Ruins contains diary entries and letters written by several characters, there are unique formatting decisions to make for this current project. How should the diary entries be different from the narrative text? What symbol would be best to indicate the shift between diary and narrative? Should the correspondence be in italics or in a totally different font? How would it look to use individual signature styles in script for various characters who write letters? It is up to me to make the final decisions on everything, and Lorie patiently implements my choices.

When we both feel the interior design looks the best it can, I send Lorie the finished manuscript, as well as files of the front and back matter. Now it is crunch time. Quite literally. Lorie carefully fits everything into a PDF file with the appearance of the final book—everything from the title page to “Other books by this author” at the end.