K. Lang-Slattery's Blog, page 3

July 24, 2021

Seven Types of Travelers. What Kind are you?

What kind of traveler are you? I don’t mean how experienced you are or if you prefer to travel locally or internationally. I’m interested in what activities and experiences make travel special for you.

Recently, I got to thinking about this after I received two very different reviews of my memoir, Wherever the Road Leads, A Memoir of Love, Travel, and a Van.

In a Recommended Review for US Review of Books, Nicole Yurcaba, states: “This book explores the rich cultures of mainstream travel destinations while also celebrating the bucolic settings of countries like Yugoslavia (now Serbia and Montenegro) and Afghanistan. In heartwarming portrayals of locals willing to help strangers and a young couple ready to learn the nuances of a variety of cultures, this work debunks the myths and stereotypes surrounding “nomadic” travel, unfriendly local populations, and the “ugly American. . . .”

More recently Jaycee Allen, in a 3 star review for Readers’ Favorite, wrote, “[this] is not a travel book. . . . . The couple seems to have spent their time roaring down highways or along dirt tracks, caught in their honeymoon bubble and safe in their vehicle. . . . Where are the characters, the encounters with people who are different? What is taking place in the countries they visit? Travelers need to be curious about what they see, they want to know, investigate, and travel books must give us an insight into another world.”

In spite of this reviewer’s opinion, Wherever the Road Leads received a Benjamin Franklin Silver Award in the Travel category (2021) from the Independent Publishers Association. Winners: Travel | IBPA Book Award (ibpabenjaminfranklinaward.com)

It almost seems that Nicole Yurcaba and Jaycee Allen were reading different books. Yet, obviously, that is not the case. I think the real difference is every reader understands what they read through the spectrum of their personal experience and values. These two reviewers simply have different opinions about what makes a great travel book. . . . or a good memoir.

This led me to contemplate what makes travel satisfying for me and how others often seek totally different experiences. I have identified seven main travel types. Do you recognize your travel style in one or more of them?

Bucket-Listers: These travelers are often first-timers. They want to be sure and see all the important sights and famous places at their destination. They line up to go to the top of the Eiffel Tower or the Empire State Building. A visit to the Louvre is mandatory even if they have no real interest in art. As they become more travel savvy, these travelers may expand their interests, but they still like to notch their travel belts with new places. In 1972, Tom was willing to drive several hours out of the way to San Marino so he could get another visa stamp in his passport. One of my friends journeyed to Antarctica in order say she had been to every continent.

Adventurers: High adrenaline activities lure this type of traveler. Usually, but not always, they are young. If not young, they must at least be in good physical shape and willing to experience fear. These adrenaline-junkies bungie-jump off high bridges in New Zealand, go trekking in Nepal, surf the big waves in Hawaii, or scuba dive in the Caribbean. They stand on the top of high pinnacles or sleep in hammocks suspended from the face of Half-Dome in Yosemite. The pictures they post on Instagram or Facebook make others think them a little crazy.

Vacationers: These travelers simply want to relax. Travel offers them a way to get away from stress and urban congestion. They go where they can sip on pina coladas or laze by the pool. Room service, restaurants, and a balcony with a view are their idea of a vacation. You’ll find these travelers at all-inclusive resorts or on cruises. For vacationers with a more restricted budget, camping or staying in a home exchange offering can provide the requisite relaxation and pleasant surroundings.

Soul-seekers: These travelers seek spiritual enlightenment when they travel. If they visit India, it’s to spend a month at an ashram. Think the “Pray” section of Eat, Pray, Love, by Elizabeth Gilbert. Soul-seekers may choose a monastery or a Buddhist retreat over a hotel. This type of traveler made the Esalen Institute in Big Sur, California, popular with counter culture types in the 1970s and ‘80s. Perched on cliffs overlooking the Pacific Ocean, Esalen has focused on humanistic alternative education since 1962 and is still welcoming guests today (under rigorous Covid guidelines).

Art Lovers and Creators: Artists often look at the world through an individual lens—one that feeds directly into their creative spirit. When they go to the Louvre or walk through a sculpture park, they study and analyze the work. Opera lovers may travel to Milan in the winter for the season at Teatro alla Scala. Dance aficionados may visit New York for a performance by the American Dance Theater. Painters often travel to find new locations and set up their easels for an hour of en plein air (painting outdoors) or they may take photos to use for later inspiration in their studio.

Art Lovers and Creators: Artists often look at the world through an individual lens—one that feeds directly into their creative spirit. When they go to the Louvre or walk through a sculpture park, they study and analyze the work. Opera lovers may travel to Milan in the winter for the season at Teatro alla Scala. Dance aficionados may visit New York for a performance by the American Dance Theater. Painters often travel to find new locations and set up their easels for an hour of en plein air (painting outdoors) or they may take photos to use for later inspiration in their studio.

Naturalists: The natural world is the main attraction for these travelers. Whether it is the sands of the Gobi Desert, the jungles of South America, the spectacular waterfalls of Iceland and Norway, or the wild-life of the African Savannah or Antarctica, nature lovers travel great distances to witness animals and natural phenomena of all kinds. They may participate in ecological projects like the Leatherback Turtle volunteer vacations in Costa Rica where participants walk the nesting beaches to protect the eggs and hatchlings. Or they may simply love sighting a rare wild creature on a whale-watching trip or from a jeep on the Maasai Mara Reserve in Kenya.

Desert, the jungles of South America, the spectacular waterfalls of Iceland and Norway, or the wild-life of the African Savannah or Antarctica, nature lovers travel great distances to witness animals and natural phenomena of all kinds. They may participate in ecological projects like the Leatherback Turtle volunteer vacations in Costa Rica where participants walk the nesting beaches to protect the eggs and hatchlings. Or they may simply love sighting a rare wild creature on a whale-watching trip or from a jeep on the Maasai Mara Reserve in Kenya.

Anthropologists: These travelers are interested in human society. They want to know more about how people around the world live and interact. They tend to visit cities and towns and like to talk with the locals. There are four subgroups of anthropological travelers—related, but each with its own particular emphasis.

History and Archeology: The mystery of what was, the history of the place visited, fascinates these travelers. They like museums, especially living history museums, ancient artifacts, and ruins.Socio-political: These travelers are interested in the social structure of a new place—they want to learn about the government, social programs, education, how individual people feel about their leaders, and how locals interact with each other. Cultural: These travelers seek out the arts, crafts, and activities of the people in a new place. They enjoy buying traditional clothing, tasting what the locals eat and cook, visiting native markets, learning folk crafts and folk dance, talking to people about their social traditions and ceremonies. Foodies, especially those who love the open markets, “hole-in-the-wall” neighborhood restaurants, and local cooking classes, fit in this group.Linguists: The center of any journey for these travelers is learning the language or the dialect of the place they visit.

Cultural: These travelers seek out the arts, crafts, and activities of the people in a new place. They enjoy buying traditional clothing, tasting what the locals eat and cook, visiting native markets, learning folk crafts and folk dance, talking to people about their social traditions and ceremonies. Foodies, especially those who love the open markets, “hole-in-the-wall” neighborhood restaurants, and local cooking classes, fit in this group.Linguists: The center of any journey for these travelers is learning the language or the dialect of the place they visit.

These are my groupings, formulated entirely from my personal observations. Do you agree with them? Have I missed any important group? Many travelers probably fit into more than one group. I began my travel life as a Bucket Lister. By the early 70s, I had evolved into a Cultural Anthropologist, though I also travel as an Art Lover and a Historical Anthropologist. I sometimes enjoy a short time as a Vacationer, though of the low budget variety. What type of traveler are you?

The post Seven Types of Travelers. What Kind are you? appeared first on Klang Slattery.

July 10, 2021

Two Women on a Train to Sangam. (Part 8, Return to India)

Our hotel host in Matheran had checked our train tickets and were upset to see we were booked on the slow train that stopped at every village station. “The local train will take six hours to get to Pune,” Mr. Lord had told us. “I recommend you change your tickets for the Konya Express train. One leaves Neral at 10:30 am. If you get there early, you can easily change your tickets.”

This seemed like good advice. At the station, we were able to change to the Express, but the only tickets available were for second class. We figured a bit of discomfort for two and a half hours was better than a day-long train ride.

Surprisingly, the train arrived on time.

Una and I, each wearing our heavy, travel pack on our back and a bulging day-pack across our chest (travel-style), boarded the second-class carriage. We pushed and shoved up the stairs with the other boarding passengers. As soon as we saw the crowded inside of the train car, we knew we were about to have another adventure.

Una and I, each wearing our heavy, travel pack on our back and a bulging day-pack across our chest (travel-style), boarded the second-class carriage. We pushed and shoved up the stairs with the other boarding passengers. As soon as we saw the crowded inside of the train car, we knew we were about to have another adventure.

Every inch of floor and seat space was already taken. All the seats were filled, mainly with Sari clad older women, while more women and men stood between the seats and over-flowed into the aisles. Farmers wearing white “sarong-like” dhotis and threadbare business shirts with the sleeves rolled up, sat on string-tied baskets bulging with produce. Others squatted on their haunches between the facing seats. We were able to find a few square-feet of space between stacked luggage and sandal clad feet. Una took her pack off and wedged it between her legs, while I preferred to keep mine on.

As the train began to move, we found our balance and soon rocked with the movement. People constantly pushed and shoved up and down the aisle. We had to shift our position one way or another each time someone walked by.

Even though the train was labeled an express, it still stopped at stations every fifteen minutes or so. Not only did passengers get on and off at each station, but vendors came on to sell snacks, fruit, bottled drinks, candy, and toys. They shouldered their way up and down the cars as the train moved on, calling out to attract customers. At the next station, the first group of vendors jumped off the train and another group climbed aboard. At one station, a blind beggar boarded and walked through the cars, singing and holding his hand out for coins. When the train stopped again, he was helped down to the platform by a young boy who accompanied him.

Amidst all this flowing traffic, I was glad I had kept my pack on my back. I didn’t need to lift it over and over; I only had to turn and pivot to allow people to pass. However, the pack was heavy. Two young men standing nearby expressed concern for the American lady standing in the crowded aisle. First, they tried to help me remove my pack, saying, “Too heavy, lady. Too heavy for you.” Stubbornly, I insisted it was easier to keep it on. But, after almost two hours of standing in the swaying train, I was beginning to feel the stress on my back and feet.

Finally, the crowds in our car began to thin, and my fellow passengers insisted Una and I take seats that became vacant. What a relief! I took off my pack, nestled it between my knees, and leaned back. For the half-hour on the train, I was able to sit in relative comfort.

We arrived in Pune in mid-afternoon and easily found a tuk-tuk to take us to the Girl Guide Center. When I had been in India twenty-eight years earlier, I hadn’t even known about this place. As a child, I enjoyed Girl Scouts, especially camping. In the 1970s, I dreamed of having a daughter and being a Girl Scout leader but, I knew nothing of the International aspects of Girl Scouting. By 2001, at the time of this trip, I had already been a Scout leader for eighteen years. Since the early 90s, I supervised a troop of high school age girls and had taken one group on a six-week trip around Europe. We had visited two European World Centers, one in London and the other in Switzerland. Now I was excited to be able to visit Sangam, the WAGGGS (World Association of Girl Guides and Girl Scouts) center in Pune.

Una (who had also been a Girl Scout) and I were welcomed warmly by the manager who was dressed in a blue shalwar kameez with the WAGGGS emblem repeated along the border. The international traveling groups usually visited in the summer, so Sangam was fairly quiet during our visit. A dozen British women from a Friends of Sangam organization were spending a week at the center, working on simple improvement projects and interacting with Indian Girl Guides. These friendly Brits invited us to join in their activities while we were at Sangam.

One morning, we accompanied them on a sightseeing tour of the city. We traveled in a small, rickety bus with no doors, the torn and soiled seats spilling bits of foam rubber. Our guide was a young Canadian “program specialist” and her companion, an Australian Girl Guide. We visited a variety of city sights and were treated to a picnic lunch of chapatis, curried potatoes, and tomato cucumber salad.

A party with a troop of local girls was the highlight of the evening. First, we played typical Girl Scout games on the lawn, then the girls changed into vividly colored party outfits. After a buffet dinner of Indian food, we watched a performance of traditional and “Bollywood” inspired dances. The girls’ dupattas (long scarfs) and the panels of their tunics fluttered as they spun and twirled in front of a backdrop of international flags.

A party with a troop of local girls was the highlight of the evening. First, we played typical Girl Scout games on the lawn, then the girls changed into vividly colored party outfits. After a buffet dinner of Indian food, we watched a performance of traditional and “Bollywood” inspired dances. The girls’ dupattas (long scarfs) and the panels of their tunics fluttered as they spun and twirled in front of a backdrop of international flags.

Una and I had one more train to ride to return to Mumbai. Once again in a first-class carriage, we were able to stow our luggage and settle into comfortable seats before the car began to fill with passengers. Soon every available seat was taken. Luggage and boxes of all kinds were stacked between seats and in the overheads. Passengers without assigned seats still stood in the aisle, but they tended to group near each end of the car, leaving the center section open. This train had its own uniformed vendors who walked between the cars selling pastries, sandwiches, hot chai (sweet, milky tea), and bottles of water and soda.

With the assistance of fellow passengers, we got off at the airport station and arrived at Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj International Airport well before our flight home. Our Indian adventure was about to end.

I had finally seen Rajasthan and the WAGGGS World Center. But best of all, I found it was possible to return to a place seen before and still experience new and wonderful things. India had changed very little in the twenty-eight years since I had been there the first time. It seemed a bit more crowded, some roads and public transportation had been improved, and fewer people slept on city sidewalks. However, there were still plenty of beggars, cows wandering the streets, crowds, and air pollution. The phenomenon of families of displaced poor camping on the highway medians was a new sight, probably because there had been no wide grassy medians in 1973.

I suspect that changes over the last twenty years since this 2001 trip have been much bigger and more significant. Perhaps it’s time to go to India again!

The post Two Women on a Train to Sangam. (Part 8, Return to India) appeared first on Klang Slattery.

June 24, 2021

An Indian Hill-Station Holiday (Part 7 of Return to India)

At Neral Junction, Una and I descended from our train into a different world. Gone were the crowds and filth of Mumbai. The station was a quiet oasis shaded by a striped awning. We waited there for more than an hour while trains from Mumbai came and went.

There were several ways to get to Matheran from Neral Junction—by hired car or bus (these only went to a car park a mile from town), pony cart, hand-pulled rickshaw, on foot, and via the narrow-gage railway known as the “toy train.” Una and I had opted for the heritage toy train that consisted of a diesel engine and a half-dozen small, blue carriages. Scheduled to leave at 11 am, the mini-train waited across the tracks at the only other station platform.

At first, is seemed Una and I would be the only passengers on the toy train. But we were in India. The engine was already blowing its whistle when our carriage and the one in front of us filled up with teenagers and their chaperons. We soon realized our travel companions were students from a school for deaf students. The girls, all in our car, looked pretty in matching, blue-checked shalwar kameez uniforms, each with a flowing white scarf. Most of them had done their hair in long, glistening black, braid loops tied up with red ribbons. Each student wore a hearing aid, some quite substantial. They chattered among themselves in Hindi and sign-language. At the last moment, because there was not enough room in the first car, two teenage boys reluctantly joined our carriage full of girls.

As soon as the train left the station, the chaperons passed out snacks to the students. With a smile, they also offered plates to Una and me. As we nibbled on idli (steamed fermented rice cakes) topped with grated coconut and chilies, the toy train inched up the dry, brown hills. The ride was long, hot, and tedious. The train stopped twice nowhere near any structure, almost as if the engine needed a rest.

The chaperon who sat across the aisle from us spoke perfect English. She explained that the school outing was organized by a volunteer of the Home Guard, a paramilitary auxiliary of the police. This fellow, who sat in the first car with the boys, had been trained to work with children who had disabilities. The students would stay in Matheran for four days, sleep in dormitories, go horseback riding, hiking, and take classes in compass and first-aid.

Forced to sit in the “girls’ car,” the two older boys spent most of the trip teasing the girls who sat in front of them. At the same time, a younger girl sitting behind the boys delighted at pulling the hair of one of them and yanking on his hearing aid cord. A lanky youth with a thin mustache and a jutting jaw, he didn’t seem to mind. He talked constantly, his hands flying, while his friend sat silently, only responding occasionally with a simple gesture.

When our toy train finally reached the town of Matheran, the students eagerly poured out and followed the Home Guard officer down the road, kicking up red dust. Una and I were greeted by a tall, white-haired representative of our hotel. We followed him along the dirt road, carrying our own packs, much to the displeasure of the porters waiting at the station for tourist tips.

Though the buildings were a bit dilapidated, we immediately loved our hotel. Surrounded by gardens, the location was perfect for catching mountain breezes. We were given a big room with a veranda that overlooked a pool and a view of the Neral Valley far below. Our included meals were served in a blue dining room. The owner, a Parsi gentleman by the name of Jim Lord, served us and lingered by our table to explain each dish that came from his immaculate kitchen.

Matheran, the only hill-station in India that forbids cars, was the perfect place for us to relax for a day—a kind of vacation set between the active parts of our journey. Noted for its magnificent viewpoints, bands of roaming wild monkeys, opportunities for rock-climbing, and many saddle horses, it fulfilled its promise. Una was able to run before breakfast. We walked around town to work up an appetite before lunch and took a nap in the heat of the afternoon. After tea-time, we hiked to Sunset Point which offered a west-facing view of dramatic rock pinnacles and mountain crevices. Back at the hotel for dinner, we spent the evening chatting with Jim Lord and his wife.

Matheran, the only hill-station in India that forbids cars, was the perfect place for us to relax for a day—a kind of vacation set between the active parts of our journey. Noted for its magnificent viewpoints, bands of roaming wild monkeys, opportunities for rock-climbing, and many saddle horses, it fulfilled its promise. Una was able to run before breakfast. We walked around town to work up an appetite before lunch and took a nap in the heat of the afternoon. After tea-time, we hiked to Sunset Point which offered a west-facing view of dramatic rock pinnacles and mountain crevices. Back at the hotel for dinner, we spent the evening chatting with Jim Lord and his wife.

The Lords arranged for rickshaws to take us down the hill early the next morning. After breakfast, Una and I again shouldered our heavy travel packs. This time, the transportation was on time—two rickshaws, each with two men to manage it. We felt a bit self-conscious, wondering about political correctness, as we got into the light-weight bamboo and metal contraptions. Our luggage was piled at our feet and we set off.

One man ran in front pulling the rickshaw, while the other trotted behind to steady it or give a needed push.

The unpaved road twisted and turned through trees and over uneven stones and ruts. In some places the track was extremely steep, making it clear why the rear rickshaw man was so important. He pulled and braked the rickshaw so the forward driver wouldn’t be crushed by a run-a-way vehicle. On the descent, we passed laden pack horses heading up the hill. Even construction materials were transported with out benefit of engine power. We bounced past several heavy carts filled with bricks, each pushed up the steep incline by six or seven grunting, sweating laborers.

After a mile of this we reached the car-park and transferred to a black sedan for the rest of the way to the train station. By mid-morning we would again be on an Indian train, this time heading for the city of Pune.

The post An Indian Hill-Station Holiday (Part 7 of Return to India) appeared first on Klang Slattery.

June 9, 2021

An Early Morning Departure, (Part 6 of Return to India)

The telephone in our hotel room jangled at 4:30 am. “Yes?” I croaked into the phone.

“Wake up call, Memsahib.”

“Too early. We said to call at 5:30.”

“So sorry! Will call again at 5:30, Memsahib.”

I rolled over with a groan and pulled the sheet over my head.I tried to return to my dreams, but never reached deep slumber again. At 5:30 the phone rang a second time. I mumbled into the mouthpiece, “Yes. Thank you” and lowered the old-fashioned, black instrument onto its cradle. I reached over, jiggled Una’s mattress, and announced, “Up and at’em,” a call we had both heard every school morning from our mother.

Though we had taken a comfortable train from Delhi to Agra with Elderhostel, I had seen many more Indian trains, both on this trip and in the 70s. Trains on the Indian sub-continent were notorious for being late and over-crowded. It was a common sight to see passengers hanging out the doors or sitting in groups on the roof. We had pre-booked our tickets through an agent, but I was still worried.

Una and I were in the lobby at the appointed time. We had arranged for someone to help us get to the train station and make sure we found the correct train. But he was late. Fifteen minutes after the appointed time, our guide arrived. He was little more than a kid who, in typical teenage fashion, simply motioned for us to follow him. Once outside, we were surprised that no taxi waited in the pre-dawn gloom. Our young helper motioned for us to follow him down the street. “Taxi. Maybe Taj Hotel. Too early.” It was immediately obvious that this kid’s English skills were minimal.

Afraid of losing sight of our guide (who never gave his name and thus will be referred to as X), we fast-walked behind him. At one corner, X flagged down a lone taxi, haggled with him for a few minutes, then waved him away. “Too much rupees!” X declared. We three marched on toward the waterfront—a skinny young Indian kid followed by two middle-aged American ladies, each weighed down by a huge, green travel-pack.

I was seriously concerned about missing our 7:15 am train, but X seemed quite nonchalant. Luckily, he found a taxi near the Taj Hotel and we zoomed through the still deserted streets.

At the train station, our helper proved to be totally useless. When he saw that the main ticket window was closed, he didn’t know what to do or where to ask questions. He moved Una and I to a queue of locals who squatted in a line that extended from the ticket office, out the door, and onto the street. He stood with us, looked around with a lost expression, and did nothing. We would need to get involved.

A small group of Europeans with backpacks waited nearby and they confirmed that the ticket office would open in an hour, at 8:00 am. Our train was scheduled to leave in fifteen minutes, but we had no idea from where in the cavernous station it would depart. Nearby I spotted an open ticket window labeled “suburban trains” and reasoned they would know something.

When I asked the clerk about Neral Junction, the stop where we had been told to switch trains, he waved his hand to the far side of the station, across several platforms and tracks. With Una and X following behind, I hustled across the station and found another open ticket window. Finally, because of his ability to speak his native language, X was of use here. He was able to secure our pre-booked tickets. Now, with our tickets in hand, all we had to do was find the correct platform.

X wandered out to the nearest platform and stood there, looking perplexed. When we questioned him, we received an unintelligible string of Hindi.

Desperate, with only five minutes to go, I returned to the ticket window. “What platform for Neral Junction?” I asked.

The answer, while in English, was still typically Indian. “Number 3 or 4 or 5 or 6, or maybe 7, Memsahib.” I looked so distressed that he took pity and added, “Look for P.K.”

Platforms 3 through 6 were nearby, but none displayed a sign saying P.K. Una now rushed around the huge complex looking for platform #7. While she was gone, a train pulled away from platform #5 and another arrived. Suddenly the sign at the head of the new train flashed “P.K.” Just in time, Una returned and we hurried along the track to the first-class carriage. X trotted in our wake, evidently worried he wouldn’t get paid if he didn’t keep up.

Once Una was settled, surrounded by our luggage, I stood in the open carriage door to deal with X. Our arrangement with the agent had been to pay X for our train tickets and for our previous city tour. I stood on the step and handed X the money. The final ten-rupee note passed from me into his hand just as the train began to move out of the station.

When a kind, English speaking gentleman reassured us we were on the correct train, we finally relaxed, ready to enjoy our adventure. Two hours later we arrived at Neral junction to wait for the narrow-gage railway that would take us up the western ghats (low mountains) for a brief vacation in the cooler air of Matheran.

This was our first train adventure, but not our last.

The post An Early Morning Departure, (Part 6 of Return to India) appeared first on Klang Slattery.

An Early Morning Departure, part 6 of Return to India

The telephone in our hotel room jangled at 4:30 am. “Yes?” I croaked into the phone.

“Wake up call, Memsahib.”

“Too early. We said to call at 5:30.”

“So sorry! Will call again at 5:30, Memsahib.”

I rolled over with a groan and pulled the sheet over my head.I tried to return to my dreams, but never reached deep slumber again. At 5:30 the phone rang a second time. I mumbled into the mouthpiece, “Yes. Thank you” and lowered the old-fashioned, black instrument onto its cradle. I reached over, jiggled Una’s mattress, and announced, “Up and at’em,” a call we had both heard every school morning from our mother.

Though we had taken a comfortable train from Delhi to Agra with Elderhostel, I had seen many more Indian trains, both on this trip and in the 70s. Trains on the Indian sub-continent were notorious for being late and over-crowded. It was a common sight to see passengers hanging out the doors or sitting in groups on the roof. We had pre-booked our tickets through an agent, but I was still worried.

Una and I were in the lobby at the appointed time. We had arranged for someone to help us get to the train station and make sure we found the correct train. But he was late. Fifteen minutes after the appointed time, our guide arrived. He was little more than a kid who, in typical teenage fashion, simply motioned for us to follow him. Once outside, we were surprised that no taxi waited in the pre-dawn gloom. Our young helper motioned for us to follow him down the street. “Taxi. Maybe Taj Hotel. Too early.” It was immediately obvious that this kid’s English skills were minimal.

Afraid of losing sight of our guide (who never gave his name and thus will be referred to as X), we fast-walked behind him. At one corner, X flagged down a lone taxi, haggled with him for a few minutes, then waved him away. “Too much rupees!” X declared. We three marched on toward the waterfront—a skinny young Indian kid followed by two middle-aged American ladies, each weighed down by a huge, green travel-pack.

I was seriously concerned about missing our 7:15 am train, but X seemed quite nonchalant. Luckily, he found a taxi near the Taj Hotel and we zoomed through the still deserted streets.

At the train station, our helper proved to be totally useless. When he saw that the main ticket window was closed, he didn’t know what to do or where to ask questions. He moved Una and I to a queue of locals who squatted in a line that extended from the ticket office, out the door, and onto the street. He stood with us, looked around with a lost expression, and did nothing. We would need to get involved.

A small group of Europeans with backpacks waited nearby and they confirmed that the ticket office would open in an hour, at 8:00 am. Our train was scheduled to leave in fifteen minutes, but we had no idea from where in the cavernous station it would depart. Nearby I spotted an open ticket window labeled “suburban trains” and reasoned they would know something.

When I asked the clerk about Neral Junction, the stop where we had been told to switch trains, he waved his hand to the far side of the station, across several platforms and tracks. With Una and X following behind, I hustled across the station and found another open ticket window. Finally, because of his ability to speak his native language, X was of use here. He was able to secure our pre-booked tickets. Now, with our tickets in hand, all we had to do was find the correct platform.

X wandered out to the nearest platform and stood there, looking perplexed. When we questioned him, we received an unintelligible string of Hindi.

Desperate, with only five minutes to go, I returned to the ticket window. “What platform for Neral Junction?” I asked.

The answer, while in English, was still typically Indian. “Number 3 or 4 or 5 or 6, or maybe 7, Memsahib.” I looked so distressed that he took pity and added, “Look for P.K.”

Platforms 3 through 6 were nearby, but none displayed a sign saying P.K. Una now rushed around the huge complex looking for platform #7. While she was gone, a train pulled away from platform #5 and another arrived. Suddenly the sign at the head of the new train flashed “P.K.” Just in time, Una returned and we hurried along the track to the first-class carriage. X trotted along in our wake, evidently worried he wouldn’t get paid if he didn’t keep up.

Once Una was settled, surrounded by our luggage, I stood in the open carriage door to deal with X. Our arrangement with the agent had been to pay X for our train tickets and for our previous city tour. I stood on the step and handed X the money. The final ten-rupee note passed from me into his hand just as the train began to move out of the station.

When a kind, English speaking gentleman reassured us we were on the correct train, we finally relaxed, ready to enjoy our adventure. Two hours later we arrived at Neral junction to wait for the narrow-gage railway that would take us up the western ghats (low mountains) for a brief vacation in the cooler air of Matheran.

This was our first train adventure, but not our last.

The post An Early Morning Departure, part 6 of Return to India appeared first on Klang Slattery.

May 29, 2021

Solo Women Travelers in Mumbai (Part 5 of Return to India)

After a late night, Una and I began our first day on our own in India very slowly. I spent what seemed like hours on the phone booking a driver and guide for the next day. We arranged for an Elderhostel friend, a lady who also stayed a few extra days in Mumbai, to join us. Una, an accomplished marathon runner, donned her shorts and went for her mandatory daily run. Her habit gave me dependable alone time to read or shower without interruption. Some days I even walked behind her as she trotted along. By noon we were both ready for lunch at the Taj café. Remembering pleasant lunches Tom and I had eaten there years before, I ordered “my usual,” the fillet of Pomfret. It arrived as delicate and tasty as in my memory!

After lunch, eager to share more places I had enjoyed in the winter of 1973, I suggested we visit the sprawling Crawford market. As soon as we got out of the taxi, Una and I were enveloped by crowds of shoppers. Two middle-aged Western women, we soon attracted the attention of one of the ever-present touts. Though some of these guys can be pleasant enough companions, this one was truly obnoxious. We tried to discourage him in the bluntest way possible, but he wouldn’t leave. He claimed he was a government employee and it was his duty to stay with us. Finally, fed up with the guy’s lies, Una turned to me and said, “Let’s go find a policeman and ask if it’s true.” Instantly, our unwanted helper melted into the crowd and was gone. How powerful we felt—we had coped with a typical travel problem all by ourselves.

Sightseeing was on the top of our agenda the next day. Our hired car and a young woman guide who spoke perfect English took us to all the notable sights. The alleyway that led to the Temple of Ganesh was filled with stalls selling flower garlands. At the Gandhi Museum, we saw the room where Gandhi slept and his spinning wheel. We stopped briefly at Hanging-Gardens Park and then drove near the Parsi Towers of Silence, where the Zoroastrian dead are laid in the sun and devoured by birds of prey.

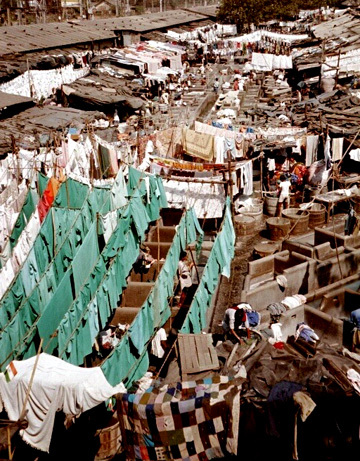

Our last stop was a view overlooking the river and the dhobi ghats. This 140-year-old, open-air laundromat hummed with activity. An estimated half-a-million pieces of laundry from hospitals, hotels, and homes are hand-washed there each day. Dozens of washer-men, each with his own concrete station, scrubbed linens and clothing, spun the wet laundry in manual dryers, and pressed out the wrinkles with charcoal filled irons.

By a stroke of good luck, Una and I had an invitation to lunch on our last day in Mumbai. We were invited to the home of a middle-class Indian family who were relatives of a member of my California writing group. On the morning of our visit, we dressed in our best (Una in a new shalwar kameez), bought a box of chocolates as a hostess gift, and set off by taxi, train, and tuk-tuk to the suburbs north of the city.

My friend’s nephew, Sachin Patel, met us at a local shopping area. Dressed in khaki slacks and a western-style shirt, he was a solid young man with a round face, a mustache, a sliver of a goatee, a friendly smile, and near-perfect English. He led us on foot to a green stucco building of indeterminate age and the small, second-floor apartment where he lived with his mother, Jyoti, his wife, Kavita, and their happy, chubby-cheeked, black-eyed, baby. The two women, both dressed in extra-nice shalwar kameez, also spoke excellent English. Their much loved, first-born son wore a little cotton shirt and a diaper the size of a hanky. He sat on his mother’s knee and babbled quietly while the adults talked.

Sachin, a designer, worked at home creating web-sites for international companies. Kavita, who had lived in Florida for four years and worked as the assistant manager for a large Miami hotel, now stayed home to care for their baby. Our hosts were easy to talk to, knowledgeable and modern, and curious about our experiences in India. After we had talked for a while, Jyoti and Kavita excused themselves to put the baby down for his nap and dish up the prepared lunch.

The women returned to the sitting room with individual thali plates (round, rimmed metal plates) brimming with the yellows, browns, greens, and reds of an Indian meal. Each bite was better than the one before—crunchy okra seasoned with coriander; a thin, slightly-sweet dhal of yellow lentils; cauliflower, cabbage, and carrot salad; sweetened, thick yogurt topped with saffron and pistachios; hot mango pickle; peas with mint; and paratha, a tender, fried, flat-bread. We ate perched on the sofas, probably because our hosts figured that American ladies wouldn’t be comfortable sitting on the floor, the usual way for Indian families to gather for meals.

I’ve always liked to eat food the way it’s eaten by the locals. I use chopsticks for Chinese food and, when in Europe, I keep my fork in my left hand and lift it backwards to my mouth. So, in India at the Patel’s home, I used the fingers of my right hand to gather up the curried vegetables, pickles, and bread. Only the thin dhal stumped me and I resorted to a discreetly placed spoon to make sure I got every drop. At the end of the meal, Kavita served squares of carrot halva, a sweet, cardamom-laced, pudding made by cooking grated carrots, milk, butter, and sugar together. I had actually made this dish at home myself so I knew it involved hours on low heat, stirring constantly until all the liquid milk evaporated and the ingredients came together into a bright orange mass.

I had read in a guide book that when visiting an Indian family, it was polite to stay only thirty minutes or so after a meal. So, after a half an hour, Una and I said we needed to go. The Patels seemed genuinely disappointed that we must leave and gave us parting gifts of small Ganesh shrines. As we stood to go, Sachin asked, “Where will you spend the rest of your time in India?”

Una mentioned that she had always wanted to visit a hill-station so we planned a trip to Matheran, located in the hills east of Mumbai. I said that we would also take the train to Pune because I wanted to visit the Girl Guide World Center located in that city.

“Oh, yes,” Jyoti said, “I know of the Center. I was a Guide when I was a girl.”

Kavita chimed in. “I also was a Girl Guide. I loved wearing the beautiful blue uniform with the scarf around my neck.”

It was already late afternoon when we made it back at our hotel. Though we were not really hungry after our lunch, Una and I were determined to try a nearby kabab stall on our last night in Mumbai. The popular food stall took over the alley behind the Taj Hotel every evening after regular business hours when it was allowed to set tables in the street. In spite of being tired, we quickly packed our bags for the next day and walked to the kabab restaurant.

In the gathering darkness, crowds filled the road near the open-air restaurant. Strings of electric light bulbs cast a yellow glow over the area. One cook concentrated on spinning and stretching dough to make paper-thin flat-bread. The dough circles, about the size of a two-person pizza, were cooked on the back of an over-turned kadai, a wok-like cooking pan. Two more sweating cooks stood over a long, metal, out-door cooker filled with red-hot coals. They turned whole chickens splayed open Tandoori-style, as well as, skewers of marinated chicken chunks, ground lamb, and chopped vegetables mixed with spices. A fourth man assembled the meals to order. He filled round sheets of warm bread with the meat of choice, a few slices of raw onion, and a scoop of chutney. The bread was rolled around the filling to form folded “sandwiches” which he put on a tray.

We watched customers place their orders with a man who held a huge book of pink, receipt slips. A young boy delivered each order to the customer with a receipt, collected the rupees, and brought the money back to the cashier. Una and I copied what we saw, placed our order, and found a tiny table among others arranged in the street. Our Chicken Tikka rolls arrived steaming hot and fragrant with spices. Each cost less than a US dollar. My only regret was that I was unable to eat a second one.

Our stay in Mumbai would soon be over. . . . . the next day we would tackle the Indian train system.

The post Solo Women Travelers in Mumbai (Part 5 of Return to India) appeared first on Klang Slattery.

May 15, 2021

A Room with a View in Mumbai (Part 4 of Return to India)

From Mumbai on, Una and I would be women traveling on our own in India. We were both nervous and excited.

I had been in charge of planning and organizing this part of our adventure. Because I retained pleasant memories of the waterfront area of Mumbai from my previous trip twenty-eight years before, I felt that would be the perfect area for us to stay. I had made reservations at a mid-class hotel, a few blocks beyond and several steps of luxury down, from the famous Taj Hotel.

When we arrived at the airport slightly before midnight, a representative from the hotel stood among the waiting crowds with a placard scrawled with “SLATTERY” in large, black letters. This was a good sign.

We bid a hasty farewell to our Elderhostel group and followed our new Indian guide. Our taxi wound through streets alive with crowds celebrating a holiday dedicated to Ganesh, the elephant-headed god of new beginnings—a most auspicious omen for us. After some time, I recognized the arch of the Gateway of India ahead, a black silhouette against the moon-sparkled water of the harbor. We drove past the iconic Taj Hotel, its façade aglow with lights, and continued down the dark road lined with spreading mango and banyan trees.

The taxi stopped in front of an unimpressive, three-story building with a single light and a neon sign to welcome travelers. The check-in desk was efficient and we were soon in a tiny elevator that clanked loudly as we rose upward. I was surprised when the door of the elevator opened and we found ourselves on a flat roof. Half the area was filled with tables and chairs and a small bar counter, all deserted at this late hour. Only a few feet across from the elevator door, a rough structure dominated the remainder of the roof. Our porter fumbled with an old lock in the wooden door of this stucco box and waved for us to enter. He handed me the key, returned to the elevator, and disappeared from sight.

The room, most likely originally meant as servants quarters, was not more than ten feet by eight feet. It allowed barely enough space to walk around the one double bed. A single, hard-backed chair stood in the corner and a narrow ledge that would never support our heavy luggage was nailed below the window. In the minuscule bathroom, the water pipe jutted out of the wall without a shower head or an enclosure. The room’s one window opened onto the café/bar, quiet now but surely a gathering place most evenings.

Una and I looked at each other in horror. We hadn’t expected the comforts of the last few weeks with our tour group, but this wasn’t the new beginning we had hoped for. “We can’t stay here,” I said. “I’ll go downstairs and beg for a better room. Wait for me.”

As I descended to the ground floor, I could only hope that there was another room available so late at night. If not, we would have to sleep in this cubicle and find something better in the morning.

I faced the sleepy desk clerk with determination. “The room is too small for two women with big luggage,” I said firmly.

The clerk looked glum. “Nothing else available,” he said with a wag of his head.

I insisted on the impossibility of our staying in the room we had been given. “If you have nothing, you must help me call someplace else and find a better room. We can not stay in the room on the roof!”

With another shake of his head, the clerk lifted the phone and made a call. I couldn’t understand his Hindi, but he seemed agitated. After several minutes, he hung up and said, “I have found something here for you. It’s a much better room, but it’s not ready for guests. You must wait a few minutes.”

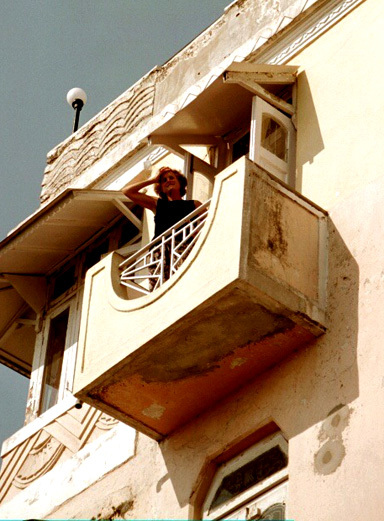

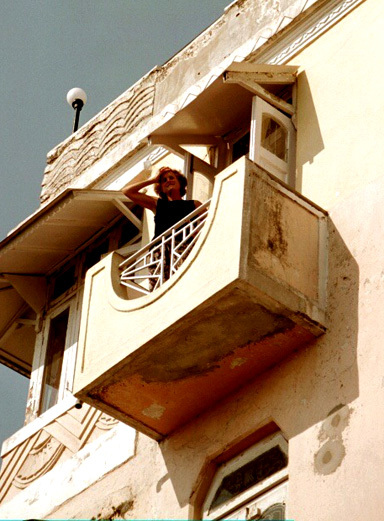

I explained that I would return to the roof to get my sister and our luggage. “Yes, yes, Memsahib,” he said. “Meet me on the third floor in ten minutes.” When we arrived there, it was obvious the room had been in use as a lounge for the hotel employees. Two men besides the clerk were scurrying about, straightening the bed-covers, dumping the waste containers, emptying ashtrays, gathering up dirty tea cups and water glasses, and removing used towels. But the room was big, there were two full sized beds, a decent bathroom, and a door that opened to a small balcony overlooking the street and the harbor. It was after one o’clock in the morning and we didn’t care that the wrinkled bedspreads were probably soiled and that dust balls lingered in the corners.

We were exhausted and fell asleep almost as soon as our heads hit the lumpy pillows.

Earlier than I would have wished, I awakened to loud cawing. Una was already up and I joined her on our little balcony. Ten or twelve large crows circled over a nearby mango tree making a racket. Below in the street, a scrawny monkey scurried along the nearby docks. We watched as the poor creature scampered down the road, the flock of crows in pursuit.

We came to love our room with a view. It was an easy walk to the Gateway of India and the Taj Hotel with its upscale shops and twenty-four-hour café. Across the street, a concrete wharf hosted parties most evenings under a pavilion a-twinkle with strings of lights. Beyond that, the silvery-blue waters of the bay stretched to a hazy horizon. And, if we awoke early enough, we could greet the sun from our east facing balcony. Pre-dawn, the bay lay blanketed in haze, the gray shapes of ships ghostly. Suddenly, where the silver of the sea bled into the gray of the sky, the orange morning sun would emerge. As the fiery orb rose, it created a molten path of reflected light that led directly toward our window.

Much can be said about hotel rooms, but, for me, a pleasant location and a balcony with a water view always top my list.

The post A Room with a View in Mumbai (Part 4 of Return to India) appeared first on Klang Slattery.

A Room with a View in Mumbai

From Mumbai on, Una and I would be women traveling on our own in India. We were both nervous and excited.

I had been in charge of planning and organizing this part of our adventure. Because I retained pleasant memories of the waterfront area of Mumbai from my previous trip twenty-eight years before, I felt that would be the perfect area for us to stay. I had made reservations at a mid-class hotel, a few blocks beyond and several steps of luxury down, from the famous Taj Hotel.

When we arrived at the airport slightly before midnight, a representative from the hotel stood among the waiting crowds with a placard scrawled with “SLATTERY” in large, black letters. This was a good sign.

We bid a hasty farewell to our Elderhostel group and followed our new Indian guide. Our taxi wound through streets alive with crowds celebrating a holiday dedicated to Ganesh, the elephant-headed god of new beginnings—a most auspicious omen for us. After some time, I recognized the arch of the Gateway of India ahead, a black silhouette against the moon-sparkled water of the harbor. We drove past the iconic Taj Hotel, its façade aglow with lights, and continued down the dark road lined with spreading mango and banyan trees.

The taxi stopped in front of an unimpressive, three-story building with a single light and a neon sign to welcome travelers. The check-in desk was efficient and we were soon in a tiny elevator that clanked loudly as we rose upward. I was surprised when the door of the elevator opened and we found ourselves on a flat roof. Half the area was filled with tables and chairs and a small bar counter, all deserted at this late hour. Only a few feet across from the elevator door, a rough structure dominated the remainder of the roof. Our porter fumbled with an old lock in the wooden door of this stucco box and waved for us to enter. He handed me the key, returned to the elevator, and disappeared from sight.

The room, most likely originally meant as servants quarters, was not more than ten feet by eight feet. It allowed barely enough space to walk around the one double bed. A single, hard-backed chair stood in the corner and a narrow ledge that would never support our heavy luggage was nailed below the window. In the minuscule bathroom, the water pipe jutted out of the wall without a shower head or an enclosure. The room’s one window opened onto the café/bar, quiet now but surely a gathering place most evenings.

Una and I looked at each other in horror. We hadn’t expected the comforts of the last few weeks with our tour group, but this wasn’t the new beginning we had hoped for. “We can’t stay here,” I said. “I’ll go downstairs and beg for a better room. Wait for me.”

As I descended to the ground floor, I could only hope that there was another room available so late at night. If not, we would have to sleep in this cubicle and find something better in the morning.

I faced the sleepy desk clerk with determination. “The room is too small for two women with big luggage,” I said firmly.

The clerk looked glum. “Nothing else available,” he said with a wag of his head.

I insisted on the impossibility of our staying in the room we had been given. “If you have nothing, you must help me call someplace else and find a better room. We can not stay in the room on the roof!”

With another shake of his head, the clerk lifted the phone and made a call. I couldn’t understand his Hindi, but he seemed agitated. After several minutes, he hung up and said, “I have found something here for you. It’s a much better room, but it’s not ready for guests. You must wait a few minutes.”

I explained that I would return to the roof to get my sister and our luggage. “Yes, yes, Memsahib,” he said. “Meet me on the third floor in ten minutes.” When we arrived there, it was obvious the room had been in use as a lounge for the hotel employees. Two men besides the clerk were scurrying about, straightening the bed-covers, dumping the waste containers, emptying ashtrays, gathering up dirty tea cups and water glasses, and removing used towels. But the room was big, there were two full sized beds, a decent bathroom, and a door that opened to a small balcony overlooking the street and the harbor. It was after one o’clock in the morning and we didn’t care that the wrinkled bedspreads were probably soiled and that dust balls lingered in the corners.

We were exhausted and fell asleep almost as soon as our heads hit the lumpy pillows.

Earlier than I would have wished, I awakened to loud cawing. Una was already up and I joined her on our little balcony. Ten or twelve large crows circled over a nearby mango tree making a racket. Below in the street, a scrawny monkey scurried along the nearby docks. We watched as the poor creature scampered down the road, the flock of crows in pursuit.

We came to love our room with a view. It was an easy walk to the Gateway of India and the Taj Hotel with its upscale shops and twenty-four-hour café. Across the street, a concrete wharf hosted parties most evenings under a pavilion a-twinkle with strings of lights. Beyond that, the silvery-blue waters of the bay stretched to a hazy horizon. And, if we awoke early enough, we could greet the sun from our east facing balcony. Pre-dawn, the bay lay blanketed in haze, the gray shapes of ships ghostly. Suddenly, where the silver of the sea bled into the gray of the sky, the orange morning sun would emerge. As the fiery orb rose, it created a molten path of reflected light that led directly toward our window.

Much can be said about hotel rooms, but, for me, a pleasant location and a balcony with a water view always top my list.

The post A Room with a View in Mumbai appeared first on Klang Slattery.

May 2, 2021

Finally Rajasthan (Part 3 of Return to India)

After five days in Northern India seeing the iconic sites of the classic Mogul emperors, we headed west. Finally, I would see Rajasthan. The largest state in India, it hugs the Pakistani border and much of it consists of the inhospitable Thar Desert. Once the home of the Rajput maharajas, Rajasthan literally means “the land of Kings.”

In the early morning of our sixth day in India, we boarded a bus and set off for Jaipur, the state capital. Tom and I had journeyed along this same road on our way to Delhi in 1972. At that time, the two-lane highway had been undergoing improvements and I remembered the women who labored there. Dressed in long, full skirts, the bright colors dulled by dust, the women carried baskets of stones on their heads or squatted in the dirt as they broke rocks into small pieces with a hammer. Now the highway was broader and the pavement smooth. Still the shoulder consisted mainly of dry dirt, concrete rubble, or ditches filled with weeds.

Our bus was comfortably roomy for our group, but its best feature, in my view, was a kind of “side-kick” folding bench on the left of the ample cab. In the morning, several members of the group spent a few minutes there in order to snap photos of the passing traffic. In the afternoon, satiated by a good lunch and groggy with the heat, my fellow travelers were content to stay in their seats where they napped, read guide books, and watched India through the smudged windows. For the entire afternoon, I reigned as queen of the jump-seat, sitting up front with the driver and the “door-man.”

From my perch, I had a clear view of the road ahead and on both sides. I wondered what I would see that was different from those earlier days . . . or if I would find it much the same. The cab was hot and the bench was hard and offered no back-rest, yet I loved every minute. Outside the window, India was on display, the sights both exotic and familiar to me. I found myself transported back to that first trip and I felt the same excitement and wonder I had experienced when I was twenty-nine.

Here are some of the sights I saw:

Lots of camel carts. They roll ponderously along on large rubber truck tires and carry loads of all kinds—everything from logs of Acacia wood to sacks of grain. The cart drivers sit on the front of the cart with one leg tucked under them, their loose sarong-like dhotis pulled up to expose brown legs. Camel carts lumber along, pulled by the long-legged beasts at a plodding pace. Once we stopped in traffic with a cart so close I could nod and wave at the turbaned mahout.Also, lots of tractors pulling loaded carts. The heavy, farm vehicles seem to have replaced many of the bullocks and water-buffalo we saw on the roads in 1972. I wonder, do tractors now pull plows or is that work still the purview of animals?Skeletons of several large cows. Their carcasses, picked clean by dogs and buzzards, lie in a roadside ditch, the bare ribs sticking up above the weeds.Men and women gathering at water pumps near their village entrance. The women collect water in jugs and recycled cooking-oil tins. They lift the heavy containers gracefully to their heads and carry them home. At the end of the work day, men in water drenched dhotis lather up under the same taps. They rinse off by dumping buckets of clear water over their heads. These late-afternoon rituals seem unchanged.I was still enjoying my special seat when we entered Jaipur. The bus climbed a narrow road lined with old buildings where court musicians used to play whenever the Maharaja arrived in the city. Our hotel overlooked a lake and the surrounding hills . . . . a clear upgrade from van camping in PWD enclosures. We only stayed a day in Jaipur but that day was filled with sightseeing, highlighted by an elephant ride up the steep entrance to the Amber Fort.

A brief early morning flight brought us to Jodhpur and more sightseeing and lectures, including one about the desert ecosystem. We learned about trees that can go thirty years without water, the importance of livestock (mainly sheep, goats, and camels), and grains, like millet, that need little water and also produce animal fodder.

The rest of the week was filled with the sights and smells of Rajasthan I had longed to experience.

At the “Clock Tower” market, stacks of vegetables and hills of spices filled the open stalls. I missed my microbus kitchen that would have allowed me to buy supplies and cook a meal. The market was crowded with shoppers and porters. Once we had to step aside to allow a lumbering elephant to pass.

At the “Clock Tower” market, stacks of vegetables and hills of spices filled the open stalls. I missed my microbus kitchen that would have allowed me to buy supplies and cook a meal. The market was crowded with shoppers and porters. Once we had to step aside to allow a lumbering elephant to pass.

One morning, we drove in jeeps across dry countryside to a weavers’ and potters’ enclave.

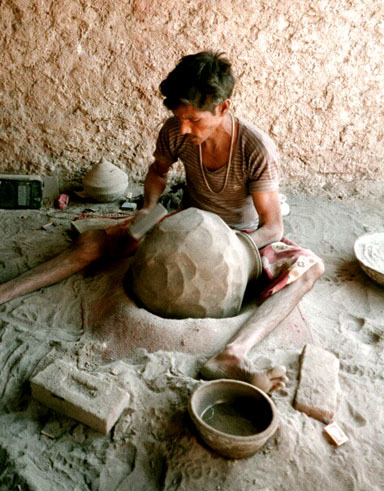

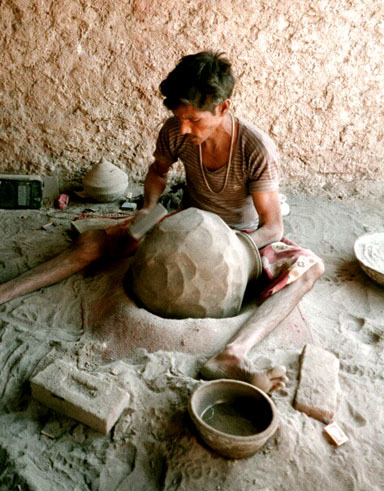

As we approached the village, our line of vehicles was joined by a parade of children and adults who waved and shouted greetings. The village elder, his thick glasses held together with tape, greeted us formally. He took us to a weaver’s home where the artisan demonstrated his pit loom sunk into the ground. At the potters’ workshop, we watched a bone-thin worker form huge jugs by hand. We sat on rugs in the village center and listened to a music performance.

Later we visited the local school, little more than a wide dirt space surrounded by low walls of dried mud. In the middle stood a concrete-topped cistern. A small awning jutted from one wall to create a patch of shade. The children, all dressed in white shirts and red skirts or shorts, sat in the dirt of the dusty rectangle to recite their lessons. At the end of a lesson, the children clustered around us, laughing and holding out their hands. I gave out handfuls of pencils I had brought from home for this purpose.

On the bus trip between Jodhpur and Udaipur, we stopped far from any village. We tramped along a narrow pathway, across a dirt field, and past an ancient waterwheel. A group of colorfully costumed local singers, musicians and dancers waited for us near a spreading Khejri tree. There, surrounded by farmland, we enjoyed a performance of drums, lutes, and dancing girls. As the dancers swayed, their vivid saris swirled in the hot air and the gold threaded borders sparkled in the sun. The tinkle of tiny cymbals attached to the dancers’ fingers and feet accompanied each graceful movement.

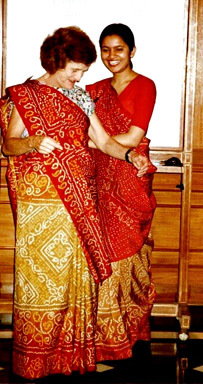

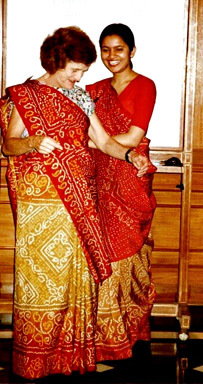

In Udaipur, at a hotel more elegant than our usual, we enjoyed a sumptuous banquet. An after-dinner lecture explained traditional clothing and how dress reveals a person’s background, education, and class status in Indian village culture. Our beloved guide, Prakesh, demonstrated how to wrap a man’s turban and dhoti. A young woman from the hotel showed how to wear a sari, using Una as the mannikin. The next evening, after shopping at a huge store filled with fabrics and art, Una and I dressed up for the group’s farewell dinner. She wore a newly-purchased sari and I sported my new, custom-fitted, blue cotton shalwar kameez (basically a long tunic over ballooning pants).

We parted from the Elderhostel group in Bombay. Soon Una and I would be traveling on our own in India. I was confident we were ready.

The post Finally Rajasthan (Part 3 of Return to India) appeared first on Klang Slattery.

Finally Rajasthan (part 3 of Return to India)

After five days in Northern India seeing the iconic sites of the classic Mogul emperors, we headed west. Finally, I would see Rajasthan. The largest state in India, it hugs the Pakistani border and much of it consists of the inhospitable Thar Desert. Once the home of the Rajput maharajas, Rajasthan literally means “the land of Kings.”

In the early morning of our sixth day in India, we boarded a bus and set off for Jaipur, the state capital. Tom and I had journeyed along this same road on our way to Delhi in 1972. At that time, the two-lane highway had been undergoing improvements and I remembered the women who labored there. Dressed in long, full skirts, the bright colors dulled by dust, the women carried baskets of stones on their heads or squatted in the dirt as they broke rocks into small pieces with a hammer. Now the highway was broader and the pavement smooth. Still the shoulder consisted mainly of dry dirt, concrete rubble, or ditches filled with weeds.

Our bus was comfortably roomy for our group, but its best feature, in my view, was a kind of “side-kick” folding bench on the left of the ample cab. In the morning, several members of the group spent a few minutes there in order to snap photos of the passing traffic. In the afternoon, satiated by a good lunch and groggy with the heat, my fellow travelers were content to stay in their seats where they napped, read guide books, and watched India through the smudged windows. For the entire afternoon, I reigned as queen of the jump-seat, sitting up front with the driver and the “door-man.”

From my perch, I had a clear view of the road ahead and on both sides. I wondered what I would see that was different from those earlier days . . . or if I would find it much the same. The cab was hot and the bench was hard and offered no back-rest, yet I loved every minute. Outside the window, India was on display, the sights both exotic and familiar to me. I found myself transported back to that first trip and I felt the same excitement and wonder I had experienced when I was twenty-nine.

Here are some of the sights I saw:

Lots of camel carts. They roll ponderously along on large rubber truck tires and carry loads of all kinds—everything from logs of Acacia wood to sacks of grain. The cart drivers sit on the front of the cart with one leg tucked under them, their loose sarong-like dhotis pulled up to expose brown legs. Camel carts lumber along, pulled by the long-legged beasts at a plodding pace. Once we stopped in traffic with a cart so close I could nod and wave at the turbaned mahout.Also, lots of tractors pulling loaded carts. The heavy, farm vehicles seem to have replaced many of the bullocks and water-buffalo we saw on the roads in 1972. I wonder, do tractors now pull plows or is that work still the purview of animals?Skeletons of several large cows. Their carcasses, picked clean by dogs and buzzards, lie in a roadside ditch, the bare ribs sticking up above the weeds.Men and women gathering at water pumps near their village entrance. The women collect water in jugs and recycled cooking-oil tins. They lift the heavy containers gracefully to their heads and carry them home. At the end of the work day, men in water drenched dhotis lather up under the same taps. They rinse off by dumping buckets of clear water over their heads. These late-afternoon rituals seem unchanged.I was still enjoying my special seat when we entered Jaipur. The bus climbed a narrow road lined with old buildings where court musicians used to play whenever the Maharaja arrived in the city. Our hotel overlooked a lake and the surrounding hills . . . . a clear upgrade from van camping in PWD enclosures. We only stayed a day in Jaipur but that day was filled with sightseeing, highlighted by an elephant ride up the steep entrance to the Amber Fort.

A brief early morning flight brought us to Jodhpur and more sightseeing and lectures, including one about the desert ecosystem. We learned about trees that can go thirty years without water, the importance of livestock (mainly sheep, goats, and camels), and grains, like millet, that need little water and also produce animal fodder.

The rest of the week was filled with the sights and smells of Rajasthan I had longed to experience.

At the “Clock Tower” market, stacks of vegetables and hills of spices filled the open stalls. I missed my microbus kitchen that would have allowed me to buy supplies and cook a meal. The market was crowded with shoppers and porters. Once we had to step aside to allow a lumbering elephant to pass.

At the “Clock Tower” market, stacks of vegetables and hills of spices filled the open stalls. I missed my microbus kitchen that would have allowed me to buy supplies and cook a meal. The market was crowded with shoppers and porters. Once we had to step aside to allow a lumbering elephant to pass.

One morning, we drove in jeeps across dry countryside to a weavers’ and potters’ enclave.

As we approached the village, our line of vehicles was joined by a parade of children and adults who waved and shouted greetings. The village elder, his thick glasses held together with tape, greeted us formally. He took us to a weaver’s home where the artisan demonstrated his pit loom sunk into the ground. At the potters’ workshop, we watched a bone-thin worker form huge jugs by hand. We sat on rugs in the village center and listened to a music performance.

Later we visited the local school, little more than a wide dirt space surrounded by low walls of dried mud. In the middle stood a concrete-topped cistern. A small awning jutted from one wall to create a patch of shade. The children, all dressed in white shirts and red skirts or shorts, sat in the dirt of the dusty rectangle to recite their lessons. At the end of a lesson, the children clustered around us, laughing and holding out their hands. I gave out handfuls of pencils I had brought from home for this purpose.

On the bus trip between Jodhpur and Udaipur, we stopped far from any village. We tramped along a narrow pathway, across a dirt field, and past an ancient waterwheel. A group of colorfully costumed local singers, musicians and dancers waited for us near a spreading Khejri tree. There, surrounded by farmland, we enjoyed a performance of drums, lutes, and dancing girls. As the dancers swayed, their vivid saris swirled in the hot air and the gold threaded borders sparkled in the sun. The tinkle of tiny cymbals attached to the dancers’ fingers and feet accompanied each graceful movement.

In Udaipur, at a hotel more elegant than our usual, we enjoyed a sumptuous banquet. An after-dinner lecture explained traditional clothing and how dress reveals a person’s background, education, and class status in Indian village culture. Our beloved guide, Prakesh, demonstrated how to wrap a man’s turban and dhoti. A young woman from the hotel showed how to wear a sari, using Una as the mannikin. The next evening, after shopping at a huge store filled with fabrics and art, Una and I dressed up for the group’s farewell dinner. She wore a newly-purchased sari and I sported my new, custom-fitted, blue cotton shalwar kameez (basically a long tunic over ballooning pants).

We parted from the Elderhostel group in Bombay. Soon Una and I would be traveling on our own in India. I was confident we were ready.

The post Finally Rajasthan (part 3 of Return to India) appeared first on Klang Slattery.