Lauret Savoy's Blog

November 13, 2025

“Landscapes of Liberation: D.C.’s History of Black Cemeteries and the Underground Railroad” Online Link

What a pleasure to introduce and moderate the exceptional panel “Landscapes of Liberation: D.C.’s History of Black Cemeteries and the Underground Railroad” on Nov. 13th as part of the Race, History, and Rock Creek series (offered by the Rock Creek Conservancy.) The panel featured Lisa Fager, C.R. Gibbs, and Mary Belcher.

My father’s ancestors were part of the history we considered — and many of his family members are buried in these and other cemeteries in the area. You can view the program if interested!

Our first panelist, Mary Belcher, is a founding member of the Walter Pierce Park Cemeteries Archaeology & Commemoration Project. This group includes descendants of those buried; as well as scientists who conducted the archaeological investigation of the site; and allies like Mary, who led the historical research into the African American and Quaker cemeteries at the park. Mary will highlight Mount Pleasant Plains Cemetery, a formally recognized site on the National Underground Railroad Network to Freedom.

Our second presenter, Lisa Fager, is Executive Director of the Black Georgetown Foundation, where she leads efforts to preserve and protect the historic Mount Zion and Female Union Band Society cemeteries in Georgetown. Through research, advocacy, and community engagement, Lisa works to ensure these sacred sites remain integral to the public memory of African American history.

Our third panelist, public historian C.R. Gibbs, author and co-author of several books, including Black Georgetown Remembered: A History of Its Black Community from the Founding of “The Town of George” in 1751 to the Present Day. CR established the “African History & Culture Lecture Series,” which gives public presentations across the Washington–Baltimore area. For these efforts, he received the District mayor’s Award for Excellence in Historic Preservation in Public Education.

November 9, 2025

“Madeline Traces: Confronting the Marks of History” in History Now! (Fall 2025)

September 9, 2024

Fellowship at Harvard University’s Warren Center for Studies in American History (Fall 2024 – Spring 2025)

I was fortunate to be awarded this fellowship to return (finally) to my book project, which pieces together the “history” of a family of global ancestries, and its ties to Chesapeake landscapes, from the colonial era to Reconstruction. Lives entwined by converging diasporas from Africa, the Indigenous Americas, and the Indian Ocean basin with immigrations from Europe. The stories of these people (free, indentured, enslaved, and enslaving), and of this land, are entangled with colonial settlement and the early plantation revolution on mainland North America, with the development of commercial slavery and laws defining “race,” with migrations by force and by choice, and with emergent populations of free people of color more than a century before the Civil War. Such people navigated the edges between freedom and bondage across generations.

August 25, 2023

Beyond Granite: Pulling Together Convening – Legacies and Futures of the National Mall

Beyond Granite: Pulling Together presents a dynamic new series of installations designed to create a more inclusive, equitable, and representative commemorative landscape on the National Mall. The Beyond Granite initiative is led by the Trust for the National Mall in partnership with the National Capital Planning Commission and the National Park Service, and is funded by the Mellon Foundation.

The Convening on August 25th is a dynamic day of discussions where artists, curators, and project leaders from Beyond Granite: Pulling Together converge with creators, scholars, activists, and practitioners from the monument landscape. Explore the rich history and transformative power of memory-making on the National Mall as we delve into meaningful conversations and collaborative sessions.

The Convening features speakers from the National Capital Planning Commission, National Park Service, and the Trust for the National Mall; exhibition artists and curators; and local and regional scholars in art, go-go music, history of the National Mall, Indigenous studies and more.

Panel 1: The National Mall: Local, National, Transnational (Begins at minute 46.30 in video)

(9:30-10:45 am)

An enriching discussion on the themes of Beyond Granite: Pulling Together that unearths the untold stories of the National Mall. Join leading scholars and authors in the field as they explore questions that shed light on connections between narratives within this hollowed site and our understanding of the landmark at both local and federal levels. Panelists will delve into the historical backdrop preceding the creation of the National Mall and point toward stories that extend beyond its hallowed grounds. Moderated by Amber Wiley from the University of Pennsylvania, this esteemed panel features renowned scholars and authors sharing insights from their works, including Lauret Savoy (Author of Trace: Memory, History, Race, and the American Landscape), Natalie Hopkinson (Author of Go-Go Live: The Musical Life and Death of a Chocolate City), and Kirk Savage (Author of Monument Wars).

June 15, 2023

“Ancestral Structures on the Trailing Edge” Released in Emergence Magazine (Audio & Text)

THE LAST BREATH before dawn. A moment of undefined edges slipping between dark and light, when it seems one might step through time and space merged.

From the crest of Virginia’s Blue Ridge I look over what, at the close of night, appears to be a vast, wind-silenced sea. Fog bound. Mist covered. Soon . . . slant light details land contouring beneath diffusing vapor; contours bound only by the dawn horizon. These lithic swells of the Piedmont—the foot of the mountains—extend eastward toward the tidewater coastal plain, toward Chesapeake Bay, toward the Atlantic Ocean beyond.

The first time I stood at such an overlook in Shenandoah National Park, a child of eight or nine beholding mist-becoming-earth, I thought eternity resided here. An existence that had to exceed human breadth. In later years I learned other scales of time and the ticks by which it is measured.

October 22, 2021

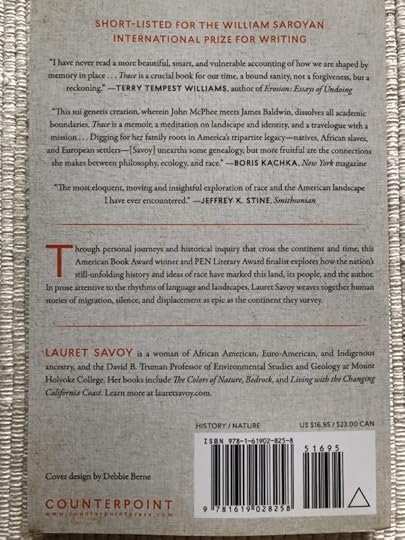

Second Edition of TRACE with a New Preface Just Released!

Dear Friends,

Hot off the press! Counterpoint Press is just now releasing another edition of Trace with a new preface from me. I’m deeply grateful that Trace takes a second breath with this new edition!

[image error]

July 4, 2020

10 books on American history that actually reflect the United States (Fortune Magazine)

Trace is featured in Rachel King’s article “10 books on American history that actually reflect the United States” from July 4 in Fortune Magazine

“It’s often remarked that history is written by the winners. It’s also an unmistakable fact that most history lessons taught in schools are often told from white and male perspectives.

“While the Fourth of July is usually a day for both celebration and relaxation for many Americans, the national mood is quite different this year. In that spirit, here is a suggested reading list of books about American history from perspectives that aren’t often included in elementary, high school, and college textbooks.” Read on!

June 6, 2020

An American Question

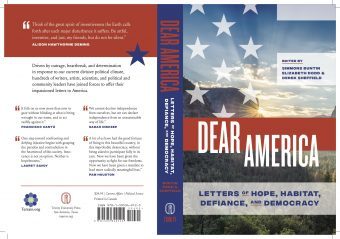

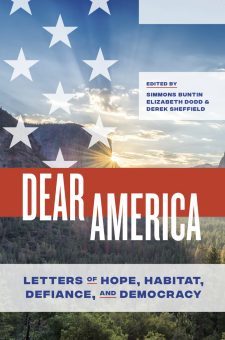

From Dear America: Letters of Hope, Habitat, Defiance, and Democracy

Published April 2020, Trinity University Press

To my country:

An old and perhaps unanswerable question has troubled me since childhood. Now it won’t let me rest.

The Revolutionary War had entered its final years, still undecided, when J. Hector St. John de Crèvecoeur asked, What then is the American, this new man? Most of the soon-to-be former colonists would probably agree with his response, published in 1782 in Letters from an American Farmer. “He is either an European, or the descendant of an European, . . . who leaving behind him all his ancient prejudices and manners, receives new ones from the new mode of life he has embraced, the new government he obeys, and the new rank he holds.” He makes “a new race of men, whose labours and posterity will one day cause great changes in the world.”

So many others were excluded from this definition: women, Indigenous peoples, as well as one-fifth the population of the fledging United States “whose labours” had driven the economies of all thirteen colonies. Slavery and its profits—whether from tobacco, cotton, sugar, or rice—buttressed the new republic. National prosperity would continue to depend on exploiting cheap labor and exploiting land once dispossessed of its original inhabitants. Part and parcel of this “new mode of life” were adaptive prejudices: concepts of race, whiteness, and white supremacy. The social and political community imagined as the new nation by the founding property-holders had to be carefully guarded.

Although recent assaults on this country’s civil society might seem unprecedented, de Crèvecoeur’s question has always been contested ground.

Any expanding membership in the imagined community of “we the people” was answered time and again by tightened boundaries. Radical Reconstruction, for instance, defined and broadened the reach of U.S. citizenship with the Civil Rights Act of 1866 and the Fourteenth and Fifteenth constitutional amendments. Those (men) once enslaved could now, in principle, enjoy equal protection under the law without regard to race. They could own land. They could run for office. They could vote . . . until the surge toward justice fell with the compromised presidential election of 1876.

A retrenching racial hierarchy promised white redemption, and not only in the South. It would take the 1964 Civil Rights Act to make into law again what had been gutted when Reconstruction was abandoned. And the era of Jim Crow would also see immigration quotas. In the spring of 1882, Congress passed the Chinese Exclusion Act, the first major federal law restricting immigration. That statute (with its extensions) would stand in force for six decades in the name of racial purity.

As a child I stumbled over “with liberty and justice for all,” wondering if there was an elastic limit to realized citizenship while my schoolmates recited the Pledge of Allegiance. These six words seemed at odds with the ceaseless media images. TV news alone brought into our home each night footage of war, assassinations, and protests by people who looked like me. I came of age doubting claims of incremental progress yet still wanting to believe in expanding tolerance if not equality.

But I wasn’t so naïve as to believe the nation had entered a post-racial, post-racist age with Barack Obama’s presidency. Not when white-supremacist and hate groups have proliferated in the last decade. Not when an opportunistic presidential campaign in 2016 could exalt ignorance, suspicion, and fear to feed racism, xenophobia, and misogyny—and win. Not when many white voters, of all economic classes, perceived that campaign’s promise to be redemption.

In the age of Trump the clock has turned back yet again on civil rights. The rule of power and profit reigns supreme. White nativists vilify Muslim, Mexican, and other “nonwhite” immigrants as alien. A nuclear arms race and other military threats escalate. Environmental regulations and protected lands fall prey to oil and gas plunder or mining. Climate science and language are censored despite global changes more rapid than predicted. Perceptions of race cut sharper, more divisive lines.

Taking back the country to “make America great again” can mean many things. One, of course, is the monochromatic need of whiteness to believe this nation is what it never was, except in the minds and rhetoric of those longing for it to be so. Their public memory requires amnesia and selective erasure of different peoples and cultures long part of the American experience.

It is tempting, here, to exhort. To warn, to urge, to insist: We must . . . We should . . . We need to . . . But changing any situation for the better requires knowing what it really is. And key to this, I believe, is comprehending how forms of othering have always been central to the democratic project that is the United States. The seeming paradox between an American creed of liberty and justice for all and the realities of an American promise denied to members of marginalized groups is, instead, a malignant symbiosis.

Transgression in word and deed—the root meaning of outrage—has occurred each day in the polarizing age of Trump. One step toward confronting and defying injustice begins with grasping the paradox and contradiction in the heartwood of this society.

Innocence is not an option. Neither is hopelessness.

The first documented arrival of Africans in the English colonies on mainland North America took place in August 1619. Four hundred years later I don’t know if we the people can acknowledge, with honesty, our intercultural past-to-present and thus admit many varied responses to “Who is an American?” I had hoped, though, that more than half a century after the assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., this nation might see itself more clearly.

Yours,

Lauret Edith Savoy

If you are interested you can order this book through Trinity Press, or from any of these Black-owned Bookstores still doing their work even during these times of overlapping pandemics.

May 23, 2020

An American Question

From Dear America: Letters of Hope, Habitat, Defiance, and Democracy

Published April 2020, Trinity University Press

To my country:

An old and perhaps unanswerable question has troubled me since childhood. Now it won’t let me rest.

The Revolutionary War had entered its final years, still undecided, when J. Hector St. John de Crèvecoeur asked, What then is the American, this new man? Most of the soon-to-be former colonists would probably agree with his response, published in 1782 in Letters from an American Farmer. “He is either an European, or the descendant of an European, . . . who leaving behind him all his ancient prejudices and manners, receives new ones from the new mode of life he has embraced, the new government he obeys, and the new rank he holds.” He makes “a new race of men, whose labours and posterity will one day cause great changes in the world.”

So many others were excluded from this definition: women, Indigenous peoples, as well as one-fifth the population of the fledging United States “whose labours” had driven the economies of all thirteen colonies. Slavery and its profits—whether from tobacco, cotton, sugar, or rice—buttressed the new republic. National prosperity would continue to depend on exploiting cheap labor and exploiting land once dispossessed of its original inhabitants. Part and parcel of this “new mode of life” were adaptive prejudices: concepts of race, whiteness, and white supremacy. The social and political community imagined as the new nation by the founding property-holders had to be carefully guarded.

Although recent assaults on this country’s civil society might seem unprecedented, de Crèvecoeur’s question has always been contested ground.

Any expanding membership in the imagined community of “we the people” was answered time and again by tightened boundaries. Radical Reconstruction, for instance, defined and broadened the reach of U.S. citizenship with the Civil Rights Act of 1866 and the Fourteenth and Fifteenth constitutional amendments. Those (men) once enslaved could now, in principle, enjoy equal protection under the law without regard to race. They could own land. They could run for office. They could vote . . . until the surge toward justice fell with the compromised presidential election of 1876.

A retrenching racial hierarchy promised white redemption, and not only in the South. It would take the 1964 Civil Rights Act to make into law again what had been gutted when Reconstruction was abandoned. And the era of Jim Crow would also see immigration quotas. In the spring of 1882, Congress passed the Chinese Exclusion Act, the first major federal law restricting immigration. That statute (with its extensions) would stand in force for six decades in the name of racial purity.

As a child I stumbled over “with liberty and justice for all,” wondering if there was an elastic limit to realized citizenship while my schoolmates recited the Pledge of Allegiance. These six words seemed at odds with the ceaseless media images. TV news alone brought into our home each night footage of war, assassinations, and protests by people who looked like me. I came of age doubting claims of incremental progress yet still wanting to believe in expanding tolerance if not equality.

But I wasn’t so naïve as to believe the nation had entered a post-racial, post-racist age with Barack Obama’s presidency. Not when white-supremacist and hate groups have proliferated in the last decade. Not when an opportunistic presidential campaign in 2016 could exalt ignorance, suspicion, and fear to feed racism, xenophobia, and misogyny—and win. Not when many white voters, of all economic classes, perceived that campaign’s promise to be redemption.

In the age of Trump the clock has turned back yet again on civil rights. The rule of power and profit reigns supreme. White nativists vilify Muslim, Mexican, and other “nonwhite” immigrants as alien. A nuclear arms race and other military threats escalate. Environmental regulations and protected lands fall prey to oil and gas plunder or mining. Climate science and language are censored despite global changes more rapid than predicted. Perceptions of race cut sharper, more divisive lines.

Taking back the country to “make America great again” can mean many things. One, of course, is the monochromatic need of whiteness to believe this nation is what it never was, except in the minds and rhetoric of those longing for it to be so. Their public memory requires amnesia and selective erasure of different peoples and cultures long part of the American experience.

It is tempting, here, to exhort. To warn, to urge, to insist: We must . . . We should . . . We need to . . . But changing any situation for the better requires knowing what it really is. And key to this, I believe, is comprehending how forms of othering have always been central to the democratic project that is the United States. The seeming paradox between an American creed of liberty and justice for all and the realities of an American promise denied to members of marginalized groups is, instead, a malignant symbiosis.

Transgression in word and deed—the root meaning of outrage—has occurred each day in the polarizing age of Trump. One step toward confronting and defying injustice begins with grasping the paradox and contradiction in the heartwood of this society.

Innocence is not an option. Neither is hopelessness.

The first documented arrival of Africans in the English colonies on mainland North America took place in August 1619. Four hundred years later I don’t know if we the people can acknowledge, with honesty, our intercultural past-to-present and thus admit many varied responses to “Who is an American?” I had hoped, though, that more than half a century after the assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., this nation might see itself more clearly.

Yours,

Lauret Edith Savoy

If you are interested you can order this book through Trinity Press, or from any of these Black-owned Bookstores still doing their work even during these times of overlapping pandemics.

August 11, 2019

Self, Made: Exploring You in a World of We – Exhibition at San Francisco’s Exploratorium

Welcome to the Exploratorium, San Francisco’s museum of science, art, and the human experience.

Self, Made: Exploring You in a World of We was a summer-long exhibition inviting “visitors to explore how we form and perform identity through dozens of new interactive exhibit experiences, works of art, and curated collections of cultural objects.” I was lucky enough to be invited to be a co-curator based on Trace and my new writing project.

Two of my installations explored laws defining race and legitimacy in the region around the nation’s capital, from the colonial era onward.

Lauret Savoy's Blog

- Lauret Savoy's profile

- 66 followers