Lauret Savoy's Blog, page 2

January 1, 2018

Letter to America

An old and perhaps unanswerable question has troubled me since my childhood. Now it won’t let me rest.

The Revolutionary War had entered its final years, still undecided, when J. Hector St. John de Crèvecoeur asked, What then is the American, this new man? Most of the soon-to-be former colonists would probably agree with his response, published in 1782 in Letters from an American Farmer. “He is either an European, or the descendant of an European, . . . who leaving behind him all his ancient prejudices and manners, receives new ones from the new mode of life he has embraced, the new government he obeys, and the new rank he holds.” He makes “a new race of men, whose labours and posterity will one day cause great changes in the world.”

So many others were excluded from this definition: women, Indigenous peoples, as well as one-fifth the population of the fledging United States “whose labours” had driven the economies of all thirteen colonies. Slavery and its profits—whether from tobacco, whether from cotton, whether from sugar or rice—buttressed the new republic. National prosperity would continue to depend on exploiting cheap labor and exploiting land once dispossessed of its original inhabitants. Part and parcel were society-animating concepts of race, whiteness, and white supremacy. The social and political community imagined as the new nation by the founding property-holders had to be carefully guarded.

Although assaults on this country’s civil society since January 2017 might seem unprecedented, de Crèvecoeur’s question has always been contested ground.

Episodes of expanding membership in the imagined community of “we the people” were answered time and again by tightening boundaries. Radical Reconstruction, for instance, defined and broadened the reach of U.S. citizenship with the Civil Rights Act of 1866 and the Fourteenth and Fifteenth constitutional amendments. Those (men) who once were enslaved could now, in principle, enjoy equal protection under the law without regard to race. They could own land. They could run for office. They could vote . . . until the surge toward justice fell with the compromised presidential election of 1876.

A retrenching racial hierarchy promised white redemption, not only in the South. It would take the 1964 Civil Rights Act to make into law again what had been gutted with the abandonment of Reconstruction. And the era of Jim Crow would also see immigration quotas. In the spring of 1882, Congress passed the first major federal law restricting immigration in the Chinese Exclusion Act. That statute (with its extensions) would stand in force for six decades in the name of racial purity.

I recall wondering as a child if there was an elastic limit to realized citizenship, stumbling over “with liberty and justice for all” as my schoolmates recited the Pledge of Allegiance. These six words seemed at odds with the ceaseless media images. The TV news alone brought into our home each night footage of war, assassinations, and anti-bigotry protests by people who looked like me. Even though I doubted the societal narrative of incremental progress, I came of age still wanting to believe in expanding tolerance if not equality.

But I wasn’t so naïve to believe that the nation had entered a post-racial, post-racist age with Barack Obama’s presidency. Not when white-supremacist and hate groups surged in numbers and membership as of 2009. Not when an opportunistic presidential campaign in 2016 could exalt ignorance, suspicion, and fear to feed racism, xenophobia, and misogyny—and win. Not when many white voters, beyond the working class, perceived that campaign’s promise as redemption.

And now, in the age of Trump, the clock turns back yet again on civil rights. The rule of power and profit reigns supreme. White nativists vilify Muslim, Mexican, and other “nonwhite” immigrants as alien nations. A nuclear arms race and other military threats escalate. Environmental regulations and protected lands fall prey to oil and gas plunder or mining. Climate science and language are censored in the face of global changes more rapid than predicted. Perceptions of race cut sharper, more divisive lines.

Taking back the country to “make America great again” can mean many things. One, of course, is the monochromatic need of whiteness to believe this nation is what it never was, except in the minds and rhetoric of those longing for it to be so. Their public memory requires amnesia and selective erasure of the many peoples and cultures long part of the American experience.

It is tempting, here, to exhort. To warn, to urge, to insist: We must . . . We should . . . We need to . . . But changing any condition or situation for the better requires knowing what it really is. And key to this, I believe, is comprehending how many forms of othering have always been central to the democratic project that is the United States.

Other writers have noted this before: The seeming paradox between an American creed of liberty, equality, and justice for all and the realities of an American promise denied to members of othered groups is, instead, a malignant symbiosis.

Transgression in word and deed—the root meaning of outrage—occurs each day in this polarizing age of Trump. One step toward confronting and defying injustice begins with grasping the paradox and contradiction in the heartwood of this society.

Innocence is not an option. Neither is hopelessness.

I don’t know if we the people can acknowledge, with honesty, our intercultural past-to-present and thus admit many responses to “Who is an American?” I had hoped, though, that half a century after the assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., this nation would see itself more clearly.

Yours,

Lauret Edith Savoy

See the original column at Terrain.org!

July 26, 2017

Amazed to Be Awarded an Andrew Carnegie Fellowship!

It’s hard for me to believe that I’m included with 34 amazing scholars-writers like Jared Farmer, Gregg Mitman, Monica Martinez, and so many more. I’m still pinching myself!

Amazed to be Awarded an Andrew Carnegie Fellowship!

It’s hard for me to believe that I’m included with 34 amazing scholars-writers like Jared Farmer, Gregg Mitman, Monica Martinez, and so many more. I’m still pinching myself!

June 26, 2017

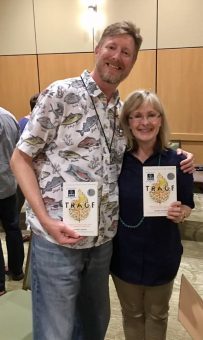

TRACE Wins ASLE Creative Writing Award

TRACE Wins Creative Writing Book Award from ASLE: Association for the Study of Literature and Environment

If anyone has mastered the art of being in two places at the same time, please let me know! ASLE just honored me by giving TRACE its biennial Creative Writing Award this past week. I couldn’t be there to accept the award (b/c of a board mtg of the National Parks Conservation Association), but my dear friends Joni Adamson and Simmons Buntin accepted on my behalf. Thank you, Joni and Simmons! Thanks, too, to another friend, Bill Stroup, for taking a video so I could see what I missed. Gratitude to all!

It is a great gift to be in the company of writers of such beautiful and powerful words: finalists Michael Branch, Chad Hanson, Kathleen Dean Moore, Midge Raymond, Kate Sutherland, and Joni Tevis! I admire you all immensely.

June 23, 2017

Punctuated Discontinuity – Canadian Rocky Mountains

The journeys that once-living organisms embark on toward the fossil record, few rarely complete. Decay or disintegration destroys more remains than not. And rocks exposed at Earth’s surface don’t chronicle all of the planet’s past. Tectonic upheavals, such as the forces that made the Rocky Mountains, and unending erosion see to that. We live among relics and ruins of former worlds.

And what remains of our own lives and experiences in the passage of time? I’ve long wondered if history might be more about forgetting and deletion than about remembering and completion.

Like the rock and fossil records I have studied, the past I’ve emerged from is pitted by gaps formed across time. Punctuated discontinuity rather than layered continuity. Erosion. Displacement. Upheaval.

We can take many lessons from Earth’s annals. As much as some might wish it, it’s not possible to retrieve a tidy, intact, and complete history of human experience on this continent from repositories of the past. Documentary records are fragments—and their existence is not a matter of unbiased preservation or re-collection. No single or simple narrative can claim the authority of history or of collective memory.

May 23, 2017

Tracing a Contextual Past – Apostle Islands, Wisconsin

For author Louise Erdrich the painted islands west of Lake Superior in Lake of the Woods are book-islands to be read. Her grandfather was the last person in her family to speak Anishinaabemowin with any fluency. So she tried to acquire what she had not been taught: an intimate engagement with “the spirit of the words” and thus with the land itself. She learned, for instance, that the word for stone—asin—is animate. “After all,” she writes, “the preexistence of the world according to Ojibwe religion consisted of a conversation between stones.”

For geologists who by and large conduct their work steeped in the traditions of Western science, Lake Superior’s book-islands have told other stories.

One I learned is that the ancestral frameworks and most aged rocks of the world’s continents lie within their exposed nuclei, the Precambrian shields. As remnants of an inconceivably distant past, shields chronicle many evolutions: the early growth of continents, origins of life, and an atmosphere gradually becoming habitable. The southernmost outcrops of North America’s core, the Canadian Shield, rim Lake Superior. The Midcontinent Rift also lies exposed here, another piece of North America’s ancient architecture.

Watching days end from my friend’s beach on Madeline Island, I soon realized that “scientific” research of the shield and rift began here because of what the bedrock contained. Paths toward understanding the history and architecture of this landscape didn’t begin in a contextual vacuum as men from Britain, France, and a fledgling United States “discovered” then deliberately sought copper and iron in the nineteenth century’s first decades.

On this southern shore of Lake Superior I saw that one path accompanied (driving and benefiting from) a state-sponsored search for mineral wealth and the treatied confinement of the Anishinaabeg in reservations. By 1890, less than half a century after the removals, the ceded lands led the world in copper mined.

Tumultuous histories, human and geological, formed this landscape. And they continue. The current move to mine iron in the nearby Penokee Range, watershed of the Bad River Band of the Lake Superior Tribe of Chippewa Indians, threatens not only tribal sovereignty and treaty rights but also the wild rice sloughs along the lakeshore that ancestors harvested for generations.

Yes, to live in this country is to be marked by its still unfolding history.

May 11, 2017

A Gift from a Wood Thrush

A few weeks ago, White-Throated Sparrows called from the woods near the mouth of Glover Archbold Park in Washington, DC, joining resident cardinals and wrens. Now Wood Thrush songs ring through the forest. I’d never seen this reclusive bird so close before, but its song greeted me on my walk back from the Potomac River. Less than 15 ft away!

http://www.lauretsavoy.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/05/IMG_4900.m4v

April 15, 2017

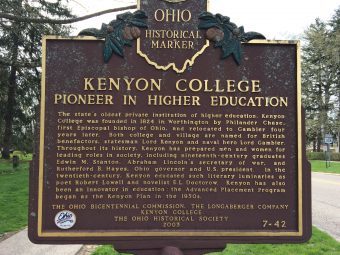

Kenyon College & the Kenyon Review

Catching Up on April – My visit to Kenyon College and the Kenyon Review earlier this month was a true gift. I met amazing students, gave a reading/talk to a generous audience, and shared the bill (science writing symposium) with Andrea Wulf. Wonderful faculty and Kenyon Review staff (like Sergei Lobanov-Rostovsky, Stella Ryan-Lozon, and Kirsten Reach) welcomed me. I also saw an old friend, Sean M. Decatur, who is now Kenyon’s president! And I had the pleasure to riding to and from the Columbus airport with another generous soul, @Wayne Uhrig, who showed me much of the physical and cultural landscape.

If you don’t know about this fine liberal arts college, please check it out. It’s Ohio’s oldest private institution of higher education. And its literary prominence dates to 1939, when poet and critic John Crowe Ransom founded the Kenyon Review.

January 13, 2017

Alabama Point & Counterpoint

Yesterday, President Obama designated Birmingham Civil Rights National Monument, honoring those citizens who faced violence and repression (including the bombing of 16th Street Baptist Church in 1963) in the then ultra-segregated city to win rights every citizen should be accorded. The Civil Rights Act of 1964 followed. This recognition within the National Park Service marks the end of long years of efforts by the city of Birmingham, Representative Terri Sewell, the National Trust for Historic Preservation, and dedicated staff of the National Parks Conservation Association. Yet this week we’ve also witnessed confirmation hearings by the Senate Judicial Committee of Alabama Senator Jeff Sessions, a one-time U.S. Attorney who long opposed civil rights, and whose record and words (including false prosecution for voter fraud) have been racist, anti immigrant, anti Muslim, and worse. If voted in next week as attorney general, Jefferson Beauregard Sessions III, whose name over three generations honored Confederate president Jefferson Davis and general P.G.T. Beauregard, will be in charge of enforcing the civil rights laws he long opposed.

Point. Counterpoint. I am deeply grateful to all who have ensured that Birmingham’s civil rights history will be protected for future generations. Yet, the legacy of the heroic struggle could be threatened if Sessions is confirmed as the nation’s next attorney general. The fiction of legislated equality, with its supposed removal of “racial” barriers, will become more starkly evident if our judicial system continues to dismantle—by not enforcing, by narrowly interpreting—key laws enacted in the civil rights movement of the 1950s and 1960s. Yet the federal government’s failure to enforce civil rights laws is at least as old as its abandonment of Reconstruction with the 1876-77 presidential election. America’s past lives in the present. I will not stand still.

December 5, 2016

A Gift from Rick Simonson & Ursula K. LeGuin

The last two autumn readings for Trace took me across country to the Pacific Northwest. My first stop was at the amazing Elliott Bay Book Company in Seattle, thanks to Rick Simonson, then an event to Powell’s City of Books in Portland. It was a gift to be welcomed by book lovers at both stores.

But Rick also offered a special treat. He had made an appointment to visit Ursula K. LeGuin at her home in Portland and invited me, with her permission, to join him. What a warm, lovely afternoon with the LeGuins and Rick. I’m so grateful.

Lauret Savoy's Blog

- Lauret Savoy's profile

- 66 followers