Lauret Savoy's Blog, page 4

April 30, 2016

A View from Point Sublime

We entered Grand Canyon National Park before sunrise, turning west onto the primitive road toward Point Sublime.

This was in those ancient days when a Coupe de Ville could negotiate the unpaved miles with just a few dents and scrapes. My father had driven through the Kaibab Plateau’s forest on Arizona Highway 67 from Jacob Lake, Momma up front with him. No other headlights cut the dark. I sat in the back seat with Cissie, my dozing 18-year-old cousin. Our Kodak Instamatic ready in my hands, cocked. For two hours or more we passed through shadows that in dawn’s cool arrival became aspen-edged meadows and stands of ponderosa pine. Up resistant limestone knolls, down around sinks and ravines. Up then down. Up then down. In time, through small breaks between trees, we could glimpse a distant level horizon sharpening in the glow of first light.

Decades have passed, nearly my entire life, since a seven-year-old stood with her family at a remote point on the North Rim. I hadn’t known what to expect at road’s end. The memory of what we found shapes me still.

Point Sublime sits at the tip of a long promontory that juts southward into the widest part of the canyon, a finger pointing from the forested Kaibab knuckle. It was named by Clarence Edward Dutton and other members of geological survey parties he led between 1875 and 1880. Dutton thought the view from the point was “the most sublime and awe-inspiring spectacle in the world.”

The year the Grand Canyon became a national park, in 1919, more than 44,000 people visited, most of them arriving by train to the South Rim. On the higher and more remote North Rim, those daring could try rough paths over limestone terrain to Cape Royal, Bright Angel Point, and Point Sublime.

The park now draws about five million visitors each year. The 17-mile route to Point Sublime remains primitive, and sane drivers tend not to risk low-clearance, two-wheel-drive vehicles on it. Sometimes the road is impassable. Still, the slow, bumpy way draws those who wish to see the canyon far from crowds and pavement, as my father wanted us to do those many years ago.

None of us had visited the canyon before that morning. We weren’t prepared. Neither were the men from Spain who, more than four hundred years earlier, ventured to the South Rim as part of an entrada in search of rumored gold. In 1540 García López de Cárdenas commanded a party of Francisco Vázquez de Coronado’s soldiers who sought a great and possibly navigable river they were told lay west and north of Hopi villages. Led by Native guides, these first Europeans to march up to the gorge’s edge and stare into its depths couldn’t imagine or measure its scale. Pedro de Castañeda de Nájera chronicled the expedition:

“They spent three days on this bank looking for a passage down to the river, which looked from above as if the water was six feet across, although the Indians said it was half a league wide. It was impossible to descend, for after these three days Captain Melgosa and one Juan Galeras and another companion, who were the three lightest and most agile men, made an attempt to go down at the least difficult place … They returned about four o’clock in the afternoon, not having succeeded in reaching the bottom on account of the great difficulties which they found, because what seemed to be easy from above was not so, but instead very hard and difficult. They said that they had been down about a third of the way and that the river seemed very large from the place which they reached, and that from what they saw they thought the Indians had given the width correctly. Those who stayed above had estimated that some huge rocks on the sides of cliffs seemed to be about as tall as a man, but those who went down swore that when they reached these rocks they were bigger than the great tower of Seville.”

The Spaniards knew lands of different proportions.

Writing more than three centuries later, Clarence Dutton understood how easily one could be tricked by first views from the rim. “As we contemplate these objects we find it quite impossible to realize their magnitude,” he wrote. “Not only are we deceived, but we are conscious that we are deceived, and yet we cannot conquer the deception.” “Dimensions,” he added, “mean nothing to the senses, and all that we are conscious of in this respect is a troubled sense of immensity.”

Point Sublime holds a prominent place in Dutton’s Tertiary History of the Grand Cañon District, the first detailed written account published by a fledgling U.S. Geological Survey in 1882. The work shows a science coming of age. For in the plateau and canyon country, aridity conspired with erosion to expose Earth’s anatomy. The land’s composition and structure lay bare. Though terrain was rugged and vast, equipment crude or lacking, these reconnaissances tried to sketch plausible models for land-shaping forces. Clarence Dutton gazed out from the North Rim at Point Sublime to describe the grand geologic ensemble: the great exposed slice of deep time in canyon walls, the work of uplift and erosion in creating the canyon itself. Dutton also brought his readers to the abyss’s edge to see with new eyes.

While residents of eastern landscapes might have spurned canyons and deserts as irredeemably barren, Dutton’s words and vision helped change the terms of perception. That is, for an audience acquainted with particular notions of the sublime and nature, an audience with the means, time, and inclination to tour.

What did my family bring to the edge and how did we see on that long-ago morning? I’ve wondered if the sublime can lie in both the dizzying encounter with such immensity and the reflective meaning drawn from it. Immanuel Kant’s sublime resided in the “power in us” that such an experience prompted to recognize a separateness from nature, a distance. To regard in the human mind an innate superiority over a natural world whose “might” could threaten flesh and bones but had no “dominion” over the humanity in the person. Yet, in Kant’s view, neither I nor my dark ancestors could ever reach the sublime, so debased were our origins.

We had little forewarning of where the Kaibab Plateau ended and limestone cliffs fell far away to inconceivable depth and distance. The suddenness stunned. No single camera frame could contain the expanse or play of light. Canyon walls that moments earlier descended into undefined darkness then glowed in great blocky detail. As shadows receded a thin sliver in the far inner gorge caught the rising sun, glinting—the Colorado River.

I felt no “troubled sense of immensity” but wonder—at the dance of light on rock, at ravens and white-throated swifts untethered from Earth, at a serenity unbroken.

A dear friend once said that to see the canyon even once “is never to be free of it” and to step into it “is to live that step the remainder of one’s days.” Yes. The view from Point Sublime illuminated a journey of and to perception, seeding my lifelong passion for Earth’s textures and antiquity. Though the North Rim was just one stopping place for my family on one of many journeys, still bright and defining in memory are those moments I stood on that edge, a small child with a Kodak Instamatic in hand.

March 29, 2016

“An Overseer Doing His Duty . . .”

Perhaps you’ve seen the image, too? It’s a watercolor of a man—a white man—standing on a tree stump with a long stick, smoking, one leg crossed over the other, as he watches two women of African ancestry wield hoes on land that they are clearing for planting. I’d seen this 1798 sketch by Benjamin Latrobe many times in school texts. But only now do I realize how close to home it hits.

Latrobe, a celebrated architect and engineer, is well known for his work on the Capitol building. Hired by President Jefferson in 1803 as “Surveyor of Public Buildings,” he also worked on the President’s House (later called the White House) as well as the Washington Navy Yard. But before this, and after emigrating from England in 1796, Latrobe lived in Virginia. One day he noted “an overseer doing his duty near Fredericksburg” and drew what he saw in his sketchbook.

There are many reasons why this matters. A personal one is that either of those two women could be my ancestor.

The Chesapeake region with its tidewater rivers, lowland coastal plain, and rocky Piedmont, is a place of convergences in the Atlantic world. Tribal peoples had long claimed the area as homeland. Yet colonists founded “an empire upon smoke” in the 1600s after discovering the marketability of tobacco. Enslaved Africans soon powered its cultivation as the export staple for Virginia and Maryland, two “outposts of the English economy.” This region also witnessed the longest presence and largest concentration of what historian Ira Berlin called “slaves without masters,” the rather “unfree” free African Americans.

I’ve recently learned that paternal forebears were part of Virginia’s tobacco history. What I know thus far is that ancestors lived along the Rappahannock River near Fredericksburg since at least the mid 1700s, working the land. Rachel Mann, the (as yet) earliest known matriarch, appears in paper records as a bastard child, born free and bound out as a “poor orphan” in 1770. When Virginia law required certificates of freedom be registered and carried about on person, these “colored” Manns claimed free status by the testimony of some of the wealthiest plantation owners. One ancestor, Jenney Mann, is listed as a “mulatto” “tobacco stemmer.”

I’ve written elsewhere that to live in this country is to be marked by residues of its still unfolding history, residues of silence and displacement across generations. My new writing project, “On the River’s Back,” searches for these marks in the fragmentary history of an African American family of mixed European and Indigenous heritage. It also searches for marks in the tidewater and Piedmont landscapes.

The stories of these people and of this land are entangled with both the rise and fall of tobacco agriculture as well as the origin and growth of the capital city along the Potomac River, the next major river to the north of the Rappahannock.

This work builds on my last chapter in Trace: Memory, History, Race and the American Landscape.

I look forward to sharing more of the search with you.

March 15, 2016

TRACE at the Providence Athenaeum

I give deep thanks to Christina Bevilacqua who planned and hosted my visit to The Providence Athenaeum on Friday evening (3/11). What a treat it was for me to present Trace: Memory, History, Race, & the American Landscape at the Athenaeum’s Salon.

The Salon began in 2006, and meets every Friday evening from 5 to 7pm in the fall, late winter, and spring. Each salon begins with half an hour of delicious food, fine drink, and mingling among the attendees — regulars, occasional participants, and new visitors. As Christina notes, one dynamic of the ideal salon is that it contains a mix of the familiar and the new.

It was a spectacular evening for me, with the warm welcome that TRACE received. And it was a thread of serendipity beginning with Christina’s walking into 192 Books in NYC, finding TRACE on a table, and picking it up because of the cover. The thread has led to a new friendship.

If you have a chance, please try to attend one of the salon events at The Providence Athenaeum. It’s a wonderful community!

[Athenaeum Salon art by Mary Brower]

February 10, 2016

African Americans in the Anti-Slavery Movement & a Family Trace

Her work also relates to my last note on my great-grandfather Edward Augustine Savoy, to my new writing project, and to the difficulty of tracing a familial past.

Edward Augustine’s parents, Edward L. and Elizabeth Butler Savoy, appear in the 1850 and 1860 federal censuses in Washington City as free mulattoes. The 1860 Federal Census lists my great-great-grandfather as a “laborer” and my great-great-grandmother Elizabeth a “washerwoman.”

Only by chance did I learn that she was part of the local anti-slavery community. A single sentence left a trace in a 1969 research article on the “free Negro population” of Washington: “Elizabeth Savoy, wife of Edward Savoy, a successful caterer, worked with the underground railway and helped slaves make their way northward to Canada and freedom.” One sentence in an article with no noted source. The author, long dead, apparently left no research files. Yet twenty-five words revealed more about the kind of woman my great-great-grandmother was than “washerwoman” on a census ever could. Her husband made a “successful” living at a time when most respectable jobs were closed to free men of color.

The last chapter in TRACE (“Placing Washington, D.C., after the Inauguration”) introduces this paternal line as I begin to search for origins, not just of blood but of the deliberate siting of the nation’s capital along the Potomac River and the economic motives of slavery.

My new writing project, “On the River’s Back,” continues this search for generational landscapes and familial ties to the tidewater and Piedmont landscapes of Maryland and Virginia (and DC) from the colonial era to the Civil War. The land itself is and will be a big part of the story.

Manisha Sinha’s new work lifts the veil and gives voice to so many who had been lost in history’s silences. I hope I can honor paternal ancestors by giving voice to the traces left of their lives in this land. I hope you’ll wish me luck!

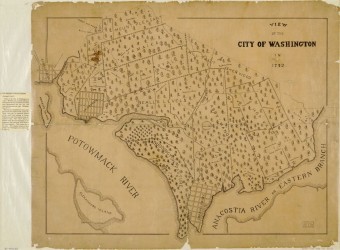

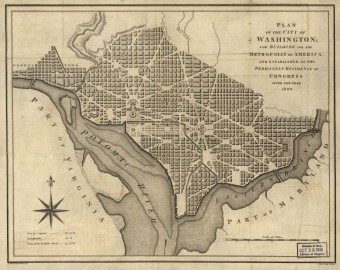

The first of the two maps shows what would become part of the nation’s capital: tobacco plantations, farms, tidal marshes, and port towns on the Maryland side of the Potomac River in 1792. The other map, from 1793, shows the plan of the City of Washington. Both maps are from the Library of Congress.

February 7, 2016

Escaping Invisibility in the Nation’s Capital

The Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture held the first Black Life Matters Wikipedia Edit-a-thon on February 7th, with volunteers contributing to articles on Wikipedia for the national Black WikiHistory Month outreach campaign.

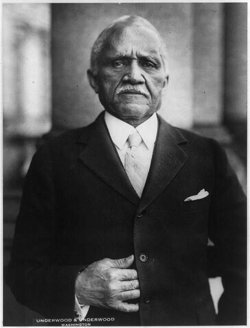

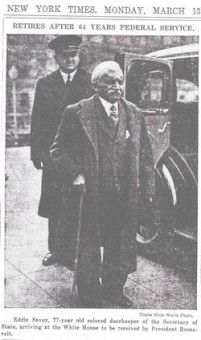

At a dear friend’s suggestion they included my great grandfather, Edward Augustine Savoy, who worked for 21 secretaries of state under 14 presidencies. He was man whom FDR had chauffeured to the White House for congratulations on his retirement at the age of 77, after one secretary of state had waived federal law and another, Henry Stimson, subverted it to keep him past the mandatory retirement age. A man whose life and contributions are little known today, yet whose story reveals the troubling ties between African Americans and the nation’s capital.

Edward Augustine Savoy was born a free person of color in Washington City, as the nation’s capital once was called, in 1855. His father was a leading caterer and public waiter to federal officials. His mother aided the Underground Railroad. After the Civil War both parents worked for Secretary of State Hamilton Fish, who hired a 14-year-old Edward Augustine as a page in 1869. Thus began a career that would span 64 years.

E. A. Savoy was privy to the paper trails of rifts and wars between nations. He witnessed the assassination of President James Garfield. He delivered ultimata and passports to diplomats, becoming known as the State Department’s international “bouncer.” In two such instances he tricked successive Spanish ministers at the outbreak of the Spanish-American War into accepting their own passports—so they could then be asked to leave the country. He carried home the treaty from Paris that ended that war, witnessing and sealing other treaties. He kept ambassadors of warring nations apart when their visits to the State Department coincided.

When finally retired in 1933, he held one of the highest government positions possible for an African American at the time, chief messenger to the secretary of state. Less than a year after his death in 1943, a Liberty ship would be launched in his honor, the SS Edward A. Savoy.

Barely five feet tall, known for his tact, charm and wit, E. A. Savoy was considered an anomaly. On meeting him for the first time, according to a newspaper account from the day, one Congressman confided, “I thought he was at least the Ambassador from Dahomey, and was quite taken back when he volunteered to take my card to the Secretary.”

Often chosen as the subject of human-interest stories, he appeared no less than six times in TIME magazine, which liked to record “Savoy-isms”: “When I meet a man who is domineering to his inferiors, I know he is sycophantic to his superiors, and no gentleman.” Or, on the language of successful diplomacy, “Never say what you want to say, and never say anything before you think twice.” The New York Times gave his obituary a full column and photo.

Yet my great grandfather never received the status, respect, or salary of the skilled diplomat he was. To government officials and the media he was “Eddie,” the “colored” messenger or “diminutive Negro” doorkeeper, rarely Edward, certainly not Edward Augustine. The boundary defined by ideas of “race” stood firm, cutting his story, and that of his family, which grew out of the paradox of Washington, D.C.

January 4, 2016

At Home on Many Shelves

Sixty-six agents declined to represent Trace. Several of them had expressed initial interest based on the query letter. But all said no, some of them taking the time to explain that they would have difficulty placing my work with a mainstream publisher. The fear was that publishers would perceive my manuscript as trying to do too many things at once, that they would have difficulty categorizing it — figuring out in what section of the bookstore it belongs. One kind agent added that the publishing environment is very conservative right now. Publishers are more risk-averse than ever, he told me, and my work would be perceived as a very risky proposition.

So you might have an idea of how grateful I am that Jack Shoemaker and Counterpoint Press were eager to take the risk.

Trace now sits on many different shelves in bookstores. In one store I found it in Biography/Memoir, in another in History, in others still in Anthropology, in Sociology, in Nature Writing, in Travel Writing, in Essays, in Psychology.

The various categories might lead one to ask if Trace is trying to do too much at once. But this question amounts to asking my Gemini-self if I am trying to think of too many “different” things at once that should be considered separately. My answer is and has to be no. As a Trace reader and new friend just told me, there are so many issues and questions and concerns in the air regarding race, justice, identity, integrity, environment, and history in this country. She appreciates how I tried to tie them together in Trace.

We all carry history within us, the past becoming present in what we think and do, in who we are. Trace is a personal narrative that asks who “we” are in this place called the United States. All Americans are implicated in the nation’s history, told and untold. We are all marked by the continuing presence of past and by America’s landscapes, whether ancestors inhabited the continent for millennia or family immigrated in recent years. I may be a witness trying to re-member, but I am not alone—these journeys speak to common concerns. Anyone calling the country home might ask similar questions: Who are “we”? What is my place as a citizen in this enterprise of America? What is my place on this land? Any honest answers require acknowledging the place of race. Anyone wondering how to live responsibly on Earth might face similar conflicts.

As well, so much writing about African-American life has focused on urban experiences. Or, if the land is mentioned, it is engaged in a commentary on the history of the South. This is an enormous mistake because the range of experience and the meaning of home are as wide as the physical land itself. Trace tries to redress this to some extent, opening to a greater richness.

The chapter-journeys in Trace cohere as experiments of cross-readings, across lines of cultural difference, across disciplines, and across the land. By asking questions about our lives in this land, and by re-imagining language and frames, the book invites creative interaction with many audiences as a calling back and forth and an exchange. Trace is not just a “race” book nor is it simply “nature writing”—it is a call for connection and dialogue.

December 5, 2015

With a Lot of Help from Friends

“Sometimes a book finds me. I know you have your own tales to tell, but occasionally I like to share the path by which a particularly fine work made its way into my hands and, subsequently, my life. This story begins in October during the author reception at the New England Independent Booksellers Association’s Fall Conference.” –Robert Gray, “How a Great Book Found Me at #NEIBA2015”

Robert Gray begins his December 4th column in Shelf Awareness with these words, reminding me how very lucky I am to have supportive friends.

Thanks to Counterpoint Press, I attended the authors’ reception at the New England Independent Booksellers Association’s fall meeting in Providence, RI. Joan Grenier, owner of the Odyssey Bookshop in South Hadley, MA, was a one-woman dynamo putting copies of Trace into the hands of bookseller after bookseller and guiding them to my table. The line quickly grew. I met Robert Gray. I met booksellers from Maine, New York, Massachusetts, Rhode Island, and Connecticut. And I understood for the first time how important word of mouth is. Joan’s support meant all the difference!

The story doesn’t end at NEIBA. Joan and other enthusiastic booksellers like Stephen Sparks (Green Apple Books in San Francisco) and Percy Sutton (Brown University Bookstore) helped to make Trace one of the Indie Next Great Reads for November. I am deeply grateful.

November 23, 2015

November 19, 20, 21 — Trace Goes West!

In traveling to the west coast for three back-to-back readings in Seattle, WA, then Point Reyes then Oakland, CA, I also realized that I had come home. Rick Simonson of the Elliott Bay Book Company and Stacie Ford-Bonnelle of the Northwest African American Museum graciously welcomed and hosted me for a reading at the museum. The visit to Seattle was all too brief, though, with little chance to get the feel of this southeastern edge of the Salish Sea.

The next morning I returned to the place of my birth, flying to the Bay Area. It still amazes me that after all these years I feel such an elemental pull by the sky, land, and sea here. This is a region of origins. Point Reyes Books and the Mesa Refuge co-sponsored a reading at the acoustically wonderful Presbyterian Community Church that night. My voice felt as embraced as I did in that sanctuary. Kate Levinson and Steve Costa (owners of Point Reyes Books), Susan Tillett of the Mesa Refuge, and friends Wendy Friefeld and Gary Thompson were joined by a welcoming audience that included Stephen Sparks of Green Apple Books in San Francisco as well as David Abram.

The nourishing whirlwind continued the following day, spent in the tremendous company of Jack Shoemaker and Jane Vandenburgh and ending with a “flash event” at Diesel Books in Oakland. Serendipity. Wonderful people–Louise Dunlap and Brad Johnson (of Diesel Books) especially, along with Counterpoint Press friends and Joyce Kouffman–all helped turn a “flash” into a reading and conversation. Carl Anthony even came!

Header photo of Elliott Bay Book Company.

November 18, 2015

November 16 — Trace Goes to Busboys & Poets (and Politics & Prose), Washington, DC

The first out-of-town launch reading from my new book Trace: Memory, History, Race, and the American Landscape took place on November 16th at Busboys & Poets in Washington, DC, in the “flagship” location on 14th and V Streets, NW. What an uplifting and inspiring evening for me at this true “community gathering place.”

Busboys and Poets describes itself as a “community where racial and cultural connections are consciously uplifted . . . a place to take a deliberate pause and feed your mind, body and soul . . . a space for art, culture and politics to intentionally collide.” The founders believed “that by creating such a space we can inspire social change and begin to transform our community and the world.”

Yes! On every visit or longer stay in the city, I come to browse the shelves and learn from conversations there. I do the same thing at Politics and Prose Bookstore, which now manages the bookselling operations for Busboys and Poets and coordinates event schedules. So, it was a huge honor to be invited to read from Trace by Politics and Prose/Busboys and Poets and to be greeted by large, welcoming audience. I had come home.

November 8, 2015

November 10 — Trace Launches!

My new book Trace: Memory, History, Race, and the American Landscape officially goes out into the world on November 10th.

The Odyssey Bookshop in South Hadley, MA, is hosting the launch party and my first reading that evening. To say that I am both nervous and excited is an understatement. The advance praise received to date—from Kirkus Review, Booklist, Publishers Weekly, Library Journal, Vulture and New York Magazine, as well as from many respected authors and booksellers—has left me amazed. I’m honored that my words are touching readers.

One irony isn’t lost on me. Berkeley, California, is my birthplace. Now Counterpoint Press has published the book that I’ve been coming to all my life just blocks from the hospital where I was born.

“Every landscape is an accumulation,” one epigraph reads. “Life must be lived amidst that which was made before.” I invite you to join me as I search for the presence of the past in this land and in a life. Please visit the book’s new website at www.readtrace.com for stories that cross this continent and time.

Header photo of Odyssey Bookshop by John Phelan, CC BY-SA 3.0.

Lauret Savoy's Blog

- Lauret Savoy's profile

- 66 followers