Kenneth C. Davis's Blog, page 85

October 13, 2014

Who Said It? (10/13/2014)

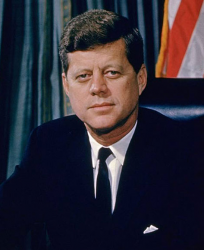

Answer: John F. Kennedy

On October 14, 1960, at 2 a.m., Senator John F. Kennedy spoke to a crowd of 10,000 cheering students at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor during a presidential campaign speech.

President John F. Kennedy (1961)

In his improvised speech, he asked:

“How many of you, who are going to be doctors, are willing to spend your days in Ghana? Technicians or engineers, how many of you are willing to work in the Foreign Service and spend your lives traveling around the world?”

“Just two weeks later, in his November 2, 1960, speech at the Cow Palace in San Francisco, Kennedy proposed “a peace corps of talented men and women” who would dedicate themselves to the progress and peace of developing countries. Encouraged by more than 25,000 letters responding to his call, Kennedy took immediate action as president to make the campaign promise a reality.” (John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum)

October 10, 2014

Pop Quiz: When was the Pledge of Allegiance written?

Answer: in 1892 to mark the 400th anniversary of Columbus’s arrival in America. The original pledge attributed to Edward Bellamy, a minister, read:

I pledge allegiance to my Flag and the Republic for which it stands, one nation, indivisible, with liberty and justice for all.

Source: US Histoy.org

It did not include the words “under God,” added in 1953 as a reaction against the Cold War threat of “godless communism.”

San Francisco, Calif., April 1942 – Children of the Weill public school, from the so-called international settlement, shown in a flag pledge ceremony. Some of them are evacuees of Japanese ancestry who will be housed in War relocation authority centers for the duration (Library of Congress)

This photograph is attributed to Dorothea Lange, the famed photographer, who died on October 11, 1965.

For more on Columbus Day, see my previous post “The World is a Pear.”

The World is a Pear: Columbus Day 2014

(Video edited and produced by Colin Davis; originally posted October 2011)

“In fourteen hundred and ninety-two/Columbus sailed the ocean blue.”

We all remember that. But after that basic date, things get a little fuzzy. Here’s what they didn’t tell you–

*Most educated people knew that the world was not flat.

*Columbus never set foot in what would become America.

*Christopher Columbus made four voyages to the so-called New World. And his discoveries opened an astonishing era of exploration and exploitation. But his arrival marked the beginning of the end for tens of millions of Native Americans spread across two continents.

In 1892, the 400th anniversary of the arrival of Columbus inspired the composition of the original Pledge of Allegiance and a proclamation by President Benjamin Harrison describing Columbus as “the pioneer of progress and enlightenment.” (Source: Library of Congress, “American Memory: Today in History: October 12”)

That was the patriotic American can-do spirit behind the Columbian Exposition—also known as the Chicago World’s Fair of 1893.

In 1934, the “progress and enlightenment” celebrated in the Columbus narrative was powerful enough to merit a federal holiday on October 12 – a reflection of the growing political clout of the Knights of Columbus, a Roman Catholic fraternal organization that fought discrimination against recently arrived immigrants, many of them Italian and Irish.

Once a hero. Now a villain. Cities and states around the country are changing the name of the holiday to “Indigenous People’s Day” or Native American Day” to move this holiday away from a man whose treatment of the natives e found included barbaric punishments and forced labor.

You can read more about Christopher Columbus, his voyages and their impact on American history in Don’t Know Much About History and Don’t Know Much About Geography.

The story of “Isabella’s Pigs,” and the role of Queen Isabella in the making of the New World, is depicted in America’s Hidden History

Don’t Know Much About® Geography (Revised and Updated Edition-Harper Perennial and Random House Audio)

Don’t Know Much About® History: Anniversary Edition (Harper Perennial and Random House Audio)

October 7, 2014

Pop Quiz: Who first used the words “Wall of Separation” in talking about church and state?

Answer: Roger Williams, the dissident minister banished by the General Court of the Massachusetts Bay Colony on October 9, 1635. Williams was told to leave the colony within six weeks. If he returned, he risked execution. He eventually went on to found Rhode Island, with a written constitution guaranteeing freedom of religion, approved by Parliament in 1644.

Williams died in Rhode Island in 1683. Learn more at the Roger Williams National Memorial (U.S. National Park Service).

As Williams biographer John M. Barry wrote:

Williams described the true church as a magnificent garden, unsullied and pure, resonant of Eden. The world he described as “the Wilderness,” a word with personal resonance for him. Then he used for the first time a phrase he would use again, a phrase that although not commonly attributed to him has echoed through American history. “[W]hen they have opened a gap in the hedge or wall of Separation between the Garden of the Church and the Wildernes of the world,” he warned, “God hathe ever broke down the wall it selfe, removed the Candlestick, &c. and made his Garden a Wildernesse.”

Read more: “God, Government and Roger Williams’ Big Idea” by John M. Barry in Smithsonian magazine

The phrase, “wall of separation between church and state” does not appear in the United States Constitution as many people think. But it was used in a famous letter written by Thomas Jefferson in 1802.

According to the Library of Congress:

This phrase has become well known because it is considered to explain (many would say, distort) the “religion clause” of the First Amendment to the Constitution: “Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion …,” a clause whose meaning has been the subject of passionate dispute for the past 50 years.

Read more about Jefferson’s letter and the phrase: “A Wall of Separation” by James Hutson, a curator at the Library of Congress

September 29, 2014

Who Said It? (9/29/14)

“A free people ought not only to be armed but disciplined”

President George Washington, “First Annual Message to Congress [State of the Union]“ (January 8, 1790)

Congress did so rather reluctantly after repeated urging from President Washington. Adopting the 1st American regiment and artillery battalion raised during Shays’s Rebellion, the uprising that helped prompt the Constitutional Convention, Congress later increased the army to 1,216 men.

But more than a year later, when Washington delivered the first Address to Congress, America’s military forces were still practically nonexistent and performing poorly in conflicts with Native Americans.

A free people ought not only to be armed but disciplined; to which end a uniform and well digested plan is requisite: And their safety and interest require that they should promote such manufactories, as tend to render them independent on others, for essential, particularly for military supplies.

The proper establishment of the troops which may be deemed indispensable, will be entitled to mature consideration. In the arrangement which will be made respecting it, it will be of importance to conciliate the comfortable support of the officers and soldiers with a due regard to economy.There was reason to hope, the pacifick measures adopted with regard to certain hostile tribes of Indians, would have relieved the inhabitants of our southern and western frontiers from their depredations. But you will perceive, from the information contained in the papers, which I shall direct to be laid before you, (comprehending a communication from the Commonwealth of Virginia) that we ought to be prepared to afford protection to those parts of the Union; and, if necessary, to punish aggressors…

Full Text and Source: Avalon Project-Yale Law School

In 1792, the Calling Forth Act and the Uniform Militia Act required universal military service. but failed to establish a true national militia.

September 26, 2014

Pop Quiz: How many times did Nixon and JFK debate in 1960?

Answer: Four, although the first was the most watched and the most memorable. The first debate was held on September 26, 1960.

Read more about presidential debates in the Smithsonian article: Eight Lessons for Presidential Debates (October 2, 2012) and in Don’t Know Much About® the American Presidents.

Don’t Know Much About® the American Presidents (Hyperion Paperback-April 15, 2014)

September 22, 2014

Who Said It? (9/22/2014)

Mob rule cannot be allowed to override the decisions of our courts.

President Eisenhower (Courtesy: Eisenhower Presidential Library and Museum)

President Dwight D. Eisenhower, “Radio and Television Address to the American People on the Situation in Little Rock,” (September 24, 1957)

For a few minutes this evening I want to speak to you about the serious situation that has arisen in Little Rock. To make this talk I have come to the President’s office in the White House. I could have spoken from Rhode Island, where I have been staying recently, but I felt that, in speaking from the house of Lincoln, of Jackson and of Wilson, my words would better convey both the sadness I feel in the action I was compelled today to take and the firmness with which I intend to pursue this course until the orders of the Federal Court at Little Rock can be executed without unlawful interference.

In that city, under the leadership of demagogic extremists, disorderly mobs have deliberately prevented the carrying out of proper orders from a Federal Court. Local authorities have not eliminated that violent opposition and, under the law, I yesterday issued a Proclamation calling upon the mob to disperse.

This morning the mob again gathered in front of the Central High School of Little Rock, obviously for the purpose of again. preventing the carrying out of the Court’s order relating to the admission of Negro children to that school.

Whenever normal agencies prove inadequate to the task and it becomes necessary for the Executive Branch of the Federal Government to use its powers and authority to uphold Federal Courts, the President’s responsibility is inescapable.

In accordance with that responsibility, I have today issued an Executive Order directing the use of troops under Federal authority to aid in the execution of Federal law at Little Rock, Arkansas. This became necessary when my Proclamation of yesterday was not observed, and the obstruction of justice still continues.

Complete text and Source: Dwight D. Eisenhower: “Radio and Television Address to the American People on the Situation in Little Rock.,” September 24, 1957. Online by Gerhard Peters and John T. Woolley, The American Presidency Project.

Pop Quiz: Which book led to passage of the Pure Food and Drug Act?

Answer: Upton Sinclair’s February 1906 novel The Jungle, an exposé of the Chicago meatpacking industry.

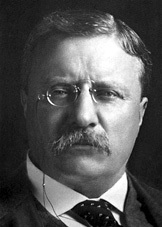

Upton Sinclair, one of the most prominent writers later derided as “muckrakers” by Theodore Roosevelt, was born on September 20, 1878 in Baltimore, Maryland.

Read a brief biography from C-Span’s “American Writers” series.

A poster of the 1913 movie adaptation of Sinclair’s novel is pictured at right, courtesy of the Sinclair Archives, Lilly Library, Indiana University, through James Harvey Young’s Pure Food: Securing the Federal Food and Drugs Act of 1906.

According to the Food and Drug Administration’s official website:

In fact, the nauseating condition of the meat-packing industry that Upton Sinclair captured in The Jungle was the final precipitating force behind both a meat inspection law and a comprehensive food and drug law.

The law was passed in June 1906 and signed by President Theodore Roosevelt.

Theodore Roosevelt (Photo Source: NobelPrize.org)

Read more about the “muckrakers” in the Progressive Era in Don’t Know Much About® History.

Don’t Know Much About® History: Anniversary Edition (Harper Perennial and Random House Audio)

September 18, 2014

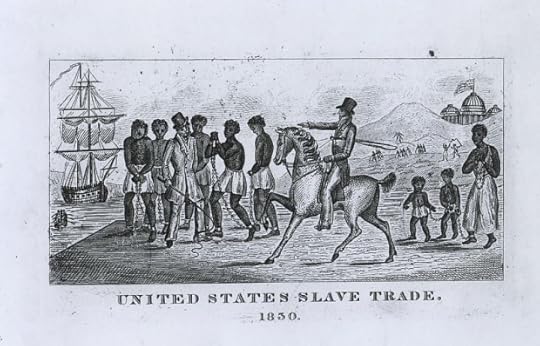

“Switching” and Slavery-A Tragic Connection

Switches, Whips and Chains-The handtools of American Slavery (Image Courtesy of Smithsonian Museum of American History)

IN the tidal wave of commentary washing over the country since Minnesota Vikings star running back Adrian Peterson was indicted after reportedly using a switch on his four-year old son, a number of commentators have commiserated, revealing similar treatment in their own childhoods. A few athletes, such as NBA star Charles Barkley, have asserted that what Peterson had done was a familiar part of their cultural upbringing.

“Whipping. We do that all the time. Every black parent in the South is going to be in jail under those circumstances,” Barkley told interviewer Jim Rome on CBS’ “NFL Today” on Sunday, September 14.

But where did generations of African-Americans, especially in the South, learn to use a switch? Anyone familiar with the literature of slavery in the United States will be familiar with switching. Fredrick Douglass, for instance, vividly described the method when, as a teenager in 1833, he was the property of a Mr. Covey:

“He then went to a large gum-tree, and with his axe cut three large switches, and after trimming them up neatly with his pocket-knife, he ordered me to take off my clothes…Upon this he rushed at me with the fierceness of a tiger, tore off my clothes, and lashed me till he had worn out his switches, cutting me so savagely as to leave the marks visible for a long time after…. During the first six months of that year, scarce a week passed without his whipping me.”[1]

Of course, Frederick Douglass’s treatment at the hands of Covey was far from unique. Witness this young runaway’s recollection of life as an enslaved child.

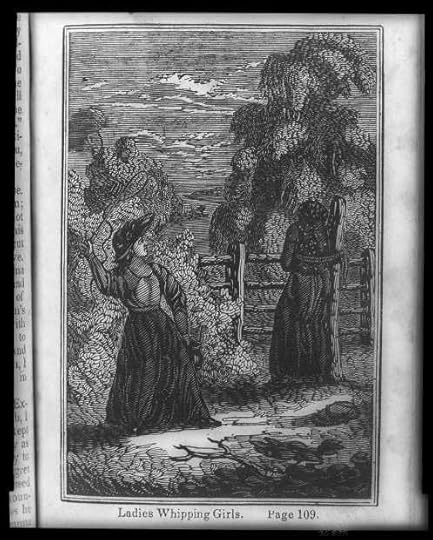

“A white woman whipping a slave girl.” (Library of Congress Rare Book and Special Collections Division Washington, D.C. 20540 USA)

“Mistress was very strict, and if we did not do every thing exactly to please her we were sure to get a whipping. An old man whipped us on our bare flesh with hickory switches. A school-master named Cleeton, boarded with her, and used to bring home a great many of them and put them in the chimney to dry. He called them ‘nice switches to whip the little niggers with.’ A good many of us were entirely naked and the rest had nothing on but shirts. I never wore any clothes till I was big enough to plough. When they whipped us they often cut through our skin. They did not call it skin, but ‘hide.’ They say ‘a nigger hasn’t got any skin.’ “[2]

In the full spectrum of cruel punishments and discipline meted out to enslaved people, of course, switching would rank towards the less fatal end of the scale –one reason it was used frequently on children, no doubt. To teach them a good lesson. And the degrees of severity of punishment and discipline went up with the severity of the offense. Severed toes and ears for repeat runaways. Branding and scarring. Execution and heads-on-pikes for insurrection. And, of course, the ever-present lash, as anyone who seen 12 Years a Slave must know.

While touring through the South in 1854, famed architect and social critic Frederick Law Olmsted witnessed the severe whipping of a young enslaved woman at the hands of an overseer.

“The screaming yells and the whip strokes had ceased when I reached the top of the bank. Choking, sobbing, spasmodic groans only were heard. I rode on to where the road, coming diagonally up the ravine, ran out upon the cotton-field. My young companion met me there, and immediately afterward the overseer. He laughed as he joined us, and said: ‘She meant to cheat me out of a day’s work, and she has done it, too.’ “ [3]

The point is that the tradition of “switching” –American Heritage defines it as “Chiefly U.S. Southern” –is a vestige of American antebellum slavery, a brutal form of power and punishment exerted by the strong over the weak, the powerful over the powerless. For centuries, the enslaved people of this country knew the switch, the lash, the cat-o-nine tails and worse. That was what made a “good” slave. That was how a human being was broken.

It is surprising that in nearly all of the recent discussion of “switching,” this “parenting technique” has not been recognized for what it is — a sad, ugly remnant of the violent maelstrom that was American slavery. This brutality against the powerless is not some biblical rod applied to keep children from being “spoiled.” It is the cruel aftermath of a system of inhuman treatment that flowed down through generations.

“We have descriptions,” wrote David Brion Davis in a history of New World slavery, “of slave children pretending to be drivers or overseers, whipping one another.” [4] (Emphasis added)

Switching is by no means peculiar to African-Americans. Whipping and beating children knows no bounds of color or creed. But carry that idea down over centuries. Children pretending to whip one another. Fathers switching sons. Grandmothers switching their charges –just as they and generations before them had been switched to teach them a lesson. The violence of slavery moving to the post-Civil War era and the Klan’s murderous beatings and burnings. Generations learning that violence was the means of exerting power.

Perhaps if more people, especially those in the African–American community, understood that “switching” is merely a short step in history from the bondsman’s lash or lynching, we might view this form of punishment for what it is.

NOTES:

[1] Frederick Douglass, Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2001, p. 47.

[2] Recollections of Slavery by a Runaway Slave (journal title) The Emancipator A Runaway Slave 5 p. August 23, September 13, September 20, October 11, and October 18, 1838 Call number Microforms Serial 1-1308 (Davis Library, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

[3] Olmsted, Frederick, Law, (Arthur M. Schlesinger ed.), The Cotton Kingdom (1953); Nevins, Allan, Ordeal of the Union (1947);

Life on a Southern Plantation, 1854″, EyeWitness to History, www.eyewitnesstohistory.com (2005)

[4] David Brion Davis, Inhuman Bondage. New York: Oxford, 2006, p. 199.

September 17, 2014

“A republic, madam, if you can keep it.” Constitution Day

On September 17, 1787, 39 delegates to the Constitutional Convention meeting in Philadelphia, voted to adopt the United States Constitution.

United States Constitution (Image Courtesy of the National Archives)

To recap these events:

Working from May 25, when a quorum was established, until September 17, 1787, when the convention voted to endorse the final form of the Constitution, the delegates gathered in Philadelphia’s Pennsylvania State House were actually obligated only to revise or amend the Articles of Confederation. Under those Articles, however, the government was plagued by weaknesses, such as its inability to raise revenues to pay its foreign debts or maintain an army. From the outset, most the convention’s organizers, James Madison chief among them, knew that splints and bandages wouldn’t do the trick for the broken Articles.

The government was broke –literally and figuratively– and they were going to fix it by inventing an entirely new one. James Madison had been studying more than 200 books on constitutions and republican history sent to him by Thomas Jefferson in preparation for the convention. The moving force behind the convention, Madison came prepared with the outline of a new Constitution.

A reluctant George Washington, whose name was placed at the head of list of Virginia’s delegates without his knowledge, was unquestionably spurred by recent events in Massachusetts (Shay’s Rebellion, a violent protest by Massachusetts farmers). Elected president of the convention, he wrote from Philadelphia in June to his close wartime confidant and ally, the Marquis de Lafayette:

I could not resist the call to a convention of the States which is to determine whether we are to have a government of respectability under which life, liberty, and property will be secured to us, or are to submit to one which may be the result of chance or the moment, springing perhaps from anarchy and Confusion, and dictated perhaps by some aspiring demagogue.

On September 17, Washington signed the parchment copy first, as President of the convention. He was followed by the remaining delegates from the twelve states that sent delegates in geographical order, from north to south, beginning with New Hampshire. (Rhode Island was the only state that did not send a delegation.) When the last of the signatures was added –that of Abraham Baldwin of Georgia– Benjamin Franklin gazed at Washington’s chair, on which was painted a bright yellow sun. He then spoke, as James Madison recorded it:

I have, said he, often in the course of a session, and the vicissitudes of my hopes and fears as to its issue, looked at that behind the President without being able to tell if it was rising or setting: But now at length I have the happiness to know that it is a rising and not a setting sun.

In another perhaps more apocryphal tale, Franklin left the building and was confronted by a lady who asked, “Well Doctor, do we have a monarchy or a republic?” The witty sage of Philadelphia replied,

“A republic, madam, if you can keep it.”

This post is excerpted from America’s Hidden History, which offers fuller account of the Convention and the events that led to it. You can also read more about the Constitutional Convention and the Constitution in Don’t Know Much About History: Anniversary Edition.

For more about the Constitution, visit these sites:

The National Constitutional Center in Philadelphia:

Charters of Freedom at the National Archives

New York Times Bestseller

America’s Hidden History

Don’t Know Much About® History: Anniversary Edition (Harper Perennial and Random House Audio)

Don’t Know Much About® the American Presidents-now available in hardcover and eBook and audiobook