Kenneth C. Davis's Blog, page 63

October 9, 2016

Columbus Day-The World Is a Pear

(Video edited and produced by Colin Davis; originally posted October 2011)

I found it (the world) was not round . . . but pear shaped, round where it has a nipple, for there it is taller, or as if one had a round ball and, on one side, it should be like a woman’s breast, and this nipple part is the highest and closest to Heaven.

–Christopher Columbus, Log of his third voyage (1498)

“In fourteen hundred and ninety-two/Columbus sailed the ocean blue.”

We all remember that. But after that basic date, things get a little fuzzy. Here’s what they didn’t tell you–

*Most educated people knew that the world was not flat.

*Columbus never set foot in what would become America.

*Christopher Columbus made four voyages to the so-called New World. And his discoveries opened an astonishing era of exploration and exploitation. But his arrival marked the beginning of the end for tens of millions of Native Americans spread across two continents.

* On his third voyage, he wrote that the world was not round but pear shaped, like a woman’s breast. They did not tell us that in Geography class.

In 1892, the 400th anniversary of the arrival of Columbus inspired the composition of the original Pledge of Allegiance and a proclamation by President Benjamin Harrison describing Columbus as “the pioneer of progress and enlightenment.” (Source: Library of Congress, “American Memory: Today in History: October 12”)

That was the patriotic American can-do spirit behind the Columbian Exposition—also known as the Chicago World’s Fair of 1893.

In 1934, the “progress and enlightenment” celebrated in the Columbus narrative was powerful enough to merit a federal holiday on October 12 – a reflection of the growing political clout of the Knights of Columbus, a Roman Catholic fraternal organization that fought discrimination against recently arrived immigrants, many of them Italian and Irish.

Once a hero. Now a villain. Cities and states around the country are changing the name of the holiday to “Indigenous People’s Day” or “Native American Day” to move this holiday away from a man whose treatment of the natives he encountered included barbaric punishments and forced labor. Seattle joined the move to swap Columbus Day

October 4, 2016

Now Available: “In the Shadow of Liberty”

“A great nation does not hide its history.” –President George W. Bush at the opening of the National Museum of African American History (9/24/2016)

The first reviews are in for In the Shadow of Liberty: The Hidden History of Slavery, Four Presidents, and Five Black Lives. (Holt Books for Young Readers/Penguin Random House Audio, September 20, 2016)

[UPDATED September 26, 2016]

*Publishers Weekly in a *Starred Review:

“–delivers an eye-opening vision of ‘stubborn facts’ in American history…”

Read the complete Publishers Weekly review here.

*School Library Journal in a *Starred Review has called the book:

“Compulsively readable….”

Read the complete School Library Journal review here.

In the Shadow of Liberty (Available for pre-order and in stores on 9/20)

*Booklist *Starred Review said:

“A valuable, broad perspective on slavery, paired with close-up views of individuals who benefited from it and those who endured it.” Booklist

Kirkus has called the book:

“An important and timely corrective.” Kirkus

In the Nonfiction Book of the Week, Horn Books says:

“Davis’s solid research (there are source notes and bibliographies for each chapter), accessible prose, and determination to make these stories known give young readers an important alternative to textbook representations of colonial life.”

In the Shadow of Liberty is now available from Holt Books for Young Readers and Penguin Random House Audio.

October 3, 2016

Listen to the trailer for the Audio Edition of In the Shadow of Liberty

This is a brief excerpt from the Audio edition of In the Shadow of Liberty: The Hidden History of Slavery, Four Presidents, and Five Black Lives (Available from Penguin Random House Audio)

x

September 28, 2016

Marbury, Madison, Marshall, and McConnell

John Adams, Second POTUS , official portrit (Source: White House Historical Association)

[UPDATED 9/28/2016]

On February 24, 1803 Chief Justice John Marshall delivered the unanimous opinion in Marbury v Madison.

Dust off your Civics books.

As the fight over Judge Garland as Antonin Scalia’s replacement on the Supreme Court absorbs the country, and Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell has vowed to block any appointments by President Obama during his last year in office, it might help to look at history.

The simple fact is that the most consequential Supreme Court appointment in American history was made by a true “lame duck” President.

In its original sense, “lame duck” meant a president or other elected official whose successor had already been chosen.

John Marshall Chief Justice of the Supreme Court

(Reproduction courtesy of the Supreme Court Historical Society)

On January 20, 1801, after it was certain that president John Adams would not return for a second term, Adams nominated his Secretary of State, John Marshall, to the post to replace ailing Chief Justice Oliver Ellsworth.

At the time of this nomination, President Adams was a true “lame duck” president, soon to be replaced by Thomas Jefferson, following a drawn-out vote in the House of Representatives. It was clear that Jefferson’s party would control both the White House and the Senate. But Adams named Marshall, a staunch Federalist of his own party, who was confirmed on January 27, 1801, despite only six-weeks of legal training.

One of Marshall’s first and most significant decisions came in the 1803 case of Marbury v. Madison which established the power of federal courts to void acts of Congress in conflict with the Constitution.

It is emphatically the province and duty of the judicial department to say what the law is. . . . Thus the particular phraseology of the constitution of the United States confirms and strengthens the principle, supposed to be essential to all written constitutions, that a law repugnant to the constitution is void. . . .

From Chief Justice Marshall’s decision in Marbury v. Madison

John Marshall went on to become the longest-serving and most influential chief justice in the history of the Supreme Court, hearing more than 1,000 cases and writing 519 decisions.

There have been more election year nominations, as discussed in this New York Times Op-Ed, “In Election Years, a History of Conforming Court Nominees.”

As John Adams himself said during the Boston Massacre Trial (1770)

“Facts are stubborn things.”

September 26, 2016

Listen to the trailer for the Audio Edition of In the Shadow of Liberty

This is a brief excerpt from the Audio edition of In the Shadow of Liberty: The Hidden History of Slavery, Four Presidents, and Five Black Lives (Available fPenguin Random House Audio)

x

Debate DOs and DON’Ts from History

Presidential debate history can be instructive. Reviewing some of the memorable moments—and debate debacles—from these televised showdowns provides a worthy primer in “debatiquette:”

Lesson 1: Lay off the Lazy Shave and Get Some Sun

The slightly unshaven look may work for Don Draper on “Mad Men,” but it was not a plus for Richard Nixon, as he learned in his historic confrontation with John F. Kennedy in the first presidential debate in 1960. Nixon had just come from a hospital stay. He had lost weight in the hospital and his suit looked ill fitting. He had also injured a knee and had to lean on the podium. To make matters worse, Nixon was given a heavy pancake makeup called “Lazy-Shave” to conceal his five o-clock shadow, making him appear even more pale and haggard. Chicago’s legendary Mayor, Richard Daley, reportedly said, “My God they’ve embalmed him before he even died.”

Read more: “Eight Lessons for the Presidential Debates”

September 23, 2016

“Mob Rule Cannot Be Allowed”-Little Rock, 1957

Mob rule cannot be allowed to override the decisions of our courts.

President Eisenhower (Courtesy: Eisenhower Presidential Library and Museum)

President Dwight D. Eisenhower, “Radio and Television Address to the American People on the Situation in Little Rock,” (September 24, 1957)

For a few minutes this evening I want to speak to you about the serious situation that has arisen in Little Rock. To make this talk I have come to the President’s office in the White House. I could have spoken from Rhode Island, where I have been staying recently, but I felt that, in speaking from the house of Lincoln, of Jackson and of Wilson, my words would better convey both the sadness I feel in the action I was compelled today to take and the firmness with which I intend to pursue this course until the orders of the Federal Court at Little Rock can be executed without unlawful interference.

In that city, under the leadership of demagogic extremists, disorderly mobs have deliberately prevented the carrying out of proper orders from a Federal Court. Local authorities have not eliminated that violent opposition and, under the law, I yesterday issued a Proclamation calling upon the mob to disperse.

This morning the mob again gathered in front of the Central High School of Little Rock, obviously for the purpose of again. preventing the carrying out of the Court’s order relating to the admission of Negro children to that school.

Whenever normal agencies prove inadequate to the task and it becomes necessary for the Executive Branch of the Federal Government to use its powers and authority to uphold Federal Courts, the President’s responsibility is inescapable.

In accordance with that responsibility, I have today issued an Executive Order directing the use of troops under Federal authority to aid in the execution of Federal law at Little Rock, Arkansas. This became necessary when my Proclamation of yesterday was not observed, and the obstruction of justice still continues.

Complete text and Source: Dwight D. Eisenhower: “Radio and Television Address to the American People on the Situation in Little Rock.,” September 24, 1957. Online by Gerhard Peters and John T. Woolley, The American Presidency Project.

September 22, 2016

Now Available: “In the Shadow of Liberty”

The first prepublication reviews are in for In the Shadow of Liberty: The Hidden History of Slavery, Four Presidents, and Five Black Lives. (Holt Books for Young Readers/Penguin Random House Audio, September 20, 2016)

[UPDATED September 12, 2016]

The latest advance review has come in from Publishers Weekly in a *Starred Review:

“–delivers an eye-opening vision of ‘stubborn facts’ in American history…”

Read the complete Publishers Weekly review here.

School Library Journal, in a *Starred Review, has called the book:

“Compulsively readable….”

Read the complete School Library Journal review here.

In the Shadow of Liberty (Available for pre-order and in stores on 9/20)

In a *Starred Review, Booklist said,

“A valuable, broad perspective on slavery, paired with close-up views of individuals who benefited from it and those who endured it.” Booklist

And Kirkus has called the book,

“An important and timely corrective.” Kirkus

In the Nonfiction Book of the Week, Horn Books says,

“Davis’s solid research (there are source notes and bibliographies for each chapter), accessible prose, and determination to make these stories known give young readers an important alternative to textbook representations of colonial life.”

In the Shadow of Liberty will be published by Holt Books for Young Readers on Sept. 20, 2016.

September 19, 2016

Who Said It? (9/19/16)

President George Washington to Secretary of the Treasury Oliver Walcott (September 1, 1796)

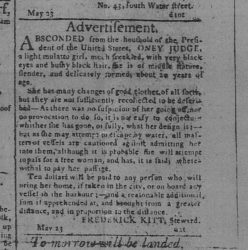

Washington secretly asked the Secretary of Treasury to help him recover Ona Judge, an enslaved woman who had escaped from Washington’s home in Philadelphia while he was serving there as president.

After Ona Judge –who was Martha Washington’s enslaved maid– made her escape in May 1796, Washington took out an advertisement offering a ten dollar reward.

In September 1796, he wrote to a member of his Cabinet:

To seize, and put her on Board a Vessel bound immediately to this place [Philadelphia], or to Alexandria which I should like better, seems at first view, to be the safest and least[t] expensive. But if she is discovered, the Collector, I am persuaded, will pursue such measures as to him shall appear best, to effect those ends;

President George Washington to Secy. of Treasury Oliver Walcott (September 1, 1796)

Source: Writings of George Washington, cited in An Imperfect God: George Washington, His Slaves, and the Creation of America by Henry Wiencek (p. 324)

Washington requested the assistance of Joseph Whipple, the Collector of the Port in Portsmouth, New Hampshire, where Ona Judge had escaped by boat and was later identified on the street.

Washington wrote this letter just weeks before his more famous “Farewell Address” was published on September 19, 1796. The complete story of Ona Judge and Washington’s relationships with the people enslaved at Mount Vernon is detailed in

In The Shadow of Liberty: The Hidden History of Slavery, Four Presidents, and Five Black Lives.

In the Shadow of Liberty (Available for pre-order and in stores on 9/20)

September 15, 2016

Did You Know? Washington re-enslaved thousands of runaways at Yorktown

When George Washington defeated the British at Yorktown, America won its freedom; thousands of enslaved African Americans lost theirs.

Surrender of Lord Cornwallis by John Trumbull hangs in the Rotunda of the U.S. Capitol (Public Domain)

When the British forces under Cornwallis surrendered to George Washington and his French allies on October 19, 1781, the terms of capitulation included the following phrase

It is understood that any property obviously belonging to the inhabitants of these States, in the possession of the garrison, shall be subject to be reclaimed.

(Article IV, Articles of Capitulation; dated October 18, 1781. Source and Complete Text: Avalon Project-Yale Law School)

Thousands of escaped enslaved people had flocked to the British army during Cornwallis’s campaign in Virginia in what has been called the “largest slave rebellion in American history.”

Among those thousands Washington had recaptured were seventeen people from his Mount Vernon plantation and about two dozen others from Thomas Jefferson’s plantations at Monticello and elsewhere. They were all returned to enslavement.

George Washington’s Mount Vernon (Author photo)

Read more about this piece of “Hidden History” in In The Shadow of Liberty: The Hidden History of Slavery, Four Presidents, and Five Black Lives.

In the Shadow of Liberty (Available for pre-order and in stores on 9/20)