Jamie Parsley's Blog, page 71

August 2, 2015

10 Pentecost

August 2, 2015

August 2, 2015Exodus 16.2-4, 9-15; Psalm 78.23-29; John 6.24-35

+ Have you seen those wonderful Snickers commercials from a couple of years ago? You know the ones. One of my favorites is the one in we see Betty White playing football with a bunch of young guys. At one point, poor Betty gets tackled. One of the guys then comes up to Betty, and says, “Mike, you’re playing like Betty White out there.” A young woman—Mike’s girlfriend, we presume— then comes over to Betty and gives her a Snickers bar. She eats it and magically she turns back into—Mike. We then see Abe Vigoda gets tackled.

At the end of the commercial we hear, “You’re not you when you’re hungry.”

At the end of the commercial we hear, “You’re not you when you’re hungry.”I love that commercial! Actually my favorite one is the one with Aretha Franklin and Liza Minella in which the punch line is, “Jeff, every times you get hungry you turn into a diva.”

Been there, been that. Let me tell you.

But we all know that feeling. We are not us when we’re hungry. We do get grouchy and snippy when we’re hungry. We mumble and we complain. And we’re unpleasant to be around. We are not “us” when we’re hungry. We too do it when we’re hungry. Which explains my attitude all the time. After all, the jokes goes, all I live off is grass and twigs—ah, vegans!

But we all know that feeling. We are not us when we’re hungry. We do get grouchy and snippy when we’re hungry. We mumble and we complain. And we’re unpleasant to be around. We are not “us” when we’re hungry. We too do it when we’re hungry. Which explains my attitude all the time. After all, the jokes goes, all I live off is grass and twigs—ah, vegans! Those commercials and that line could very well have been used on some of the people in our scriptures readings for today. Certainly today, we get some complaining in our scripture readings.

In our reading from the Hebrew Scriptures—from Exodus—we find the Israelites, in their hunger, complaining and grumbling. In some translations, we find the word “murmuring.” Over and over again in the Exodus story they seem to complain and grumble and murmur. To be fair, complaining and grumbling would be expected from people who are hungry.

But in their hunger, God provides for them. God provides them this mysterious manna—this strange bread from heaven. Nobody’s real clear what this mysterious manna actually was. It’s often described as flakes, or a dew-like substance. But it was miraculous.

Now, in our Gospel, we find the same story of the Israelites and their hunger, but it has been turned around entirely. As our Liturgy of the Word for today begins with hunger and all the complaining and murmuring and grumbling and craving that goes along with it, it ends with fulfillment. We find that the hungers now are the hungers and the cravings of our souls, of our hearts.

Now, this kind of spiritual hunger is just as real and just as all-encompassing as physical hunger. It, like physical hunger, can gnaw at us. When we are spiritually hungry we also are not “us.” We too crave after spiritual fulfillment. We mumble and complain and murmur when we are spiritually unfulfilled. We too feel that gaping emptiness within us when we hunger from a place that no physical food or drink can quench. In a sense, we too are like the Israelites, wandering about in our own wilderness—our own spiritual wilderness.

Most of us know what is like to be out there—in that spiritual wasteland—grumbling and complaining, hungry, shaking our fists at the skies and at God. We, like them, cry and complain and lament. We feel sorry for ourselves and for the predicaments we’re in. And we, like them, say to ourselves and to God, “If only I hadn’t followed God out here—if only I had stayed put or followed the easier route, I wouldn’t be here.”

We’ve all been in that place. We’ve all been in that desert, to that place we thought God had led us.

I know that in my case, I went so self-assuredly. I went certain that this was what God wanted for me. I was sure I had read all the signs. I had listened to that subtle voice of the Spirit within me. I had gauged my calling from God through the discernment of others. And then, suddenly, there I was. What began as a concentrated stepping forward, had become an aimless wandering. And, in that moment, I found myself questioning everything—I questioned myself, I questioned the others who discerned my journey, I questioned the Spirit who I was so certain spoke within me. And, in that emptiness, in that frustration, I questioned God.

And guess what I did then? I turned into Betty White. Actually I turned into Maria Callas. The Diva. I complained. And I lamented.

Lamenting is a word that seems kind of outdated for most of us. We think of lamenting being some overly dramatic complaining. Which is exactly what it is. It was what we do when we feel things like desolation.

Like hunger, few of us, again I hope, have felt utter desolation. But when we do, we know, there is no real reason to despair.

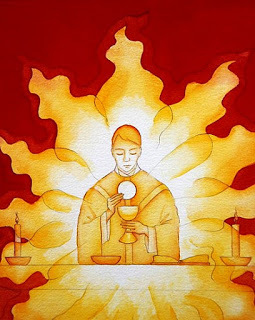

As followers of Jesus, we will find our strength and consolation in the midst of that spiritual wilderness. We know that manna will come to us in that spiritual desert. And that manna, for us, is the Eucharist. The Eucharist sustains us and holds us up during those desolate times. All we have to do, when we can’t seem to do anything else, is partake of the Eucharist. And when we do, we know that God’s presence in this “bread of God” will be there for us.

This Bread we share and the wine we drink is the very “bread of God.” This is what Eucharist is all about. This is why the Eucharist is so important to us.

I have been recently downsizing a bit at the Rectory. I have way too many books and, every so often, I have to sort them out. This past week, as I was going through my books, I came across a book I bought years ago and never read. It was Jesus Wants to Save Christiansby Rob Bell.

Now, I love Rob Bell. So, I don’t know why I never read this book. I think, for some reason, I just didn’t like the title. But I was pleasantly surprised when I started reading through the book, that it is about the Eucharist. And there was a wonderful passage Bell shares. He posts several difficult questions, any one of which we have no doubt asked at some point in our journey.

“Where was God when I tested positive?Where was God when I was suffering?Where was God when I lost my job?Where was God when I was hungry?Where was God when I was alone?”

“The Eucharist,” Bell says, “is the answer to the questions.”

Where was God? God was right here. Right here, with us. And continues to be. No longer can we accuse God of being distant. Because, God has come to us. God came to us in Jesus. And continues to come to us in this meal. Again and again.

Here, we truly do eat the Bread of angels. Here, we do partake of the grain of heaven. This is our manna in our spiritual wilderness. In this Eucharist, at this altar, we find God, present to us in just exactly the way we need God to present to us.

In our hunger, God feeds us.

In our grumbling and complaining, God quiets us. After all, when we are eating and drinking, we can’t complain and grumble.

And unlike the food we eat day by day, the food we eat at this altar will not perish.

When we are hungry, we not really “us.” But in this meal—in this Eucharist—we truly do become us. The real us. The us we are meant to be.

In this Eucharist, in the Presence of Jesus we find in this bread and this wine, we find that our grumbling and murmuring and complaining have been silenced with that quiet but sure statement that comes to us from that Presence we encounter here:

“I am the bread of life,” Jesus says. “Whoever comes to me will never be hungry, and whoever believes in me will never be thirsty.”

In the echo of that statement, we are silenced. Our grumbling spiritual stomachs are silenced. Our spiritual loneliness is vanquished. Our cravings are fulfilled. In the wake of those powerful words, we find our emptiness fulfilled. We find the strength to make our way out of the wilderness to the promised land Jesus proclaims to us.

“I am the bread of life,” he says to us.

This is the bread of life, here at this altar. And, in turn, we become the bread of life to others because we embody the One whom we follow.

“Whoever comes to me will never be hungry, and whoever believes in me will never be thirsty.”

So, let us come to the bread of life Let the One we encounter in this Bread and wine take from us our gnawing hunger and our craving thirst. And when he does, he will have given us what we have been truly craving all along.

Amen.

Published on August 02, 2015 04:05

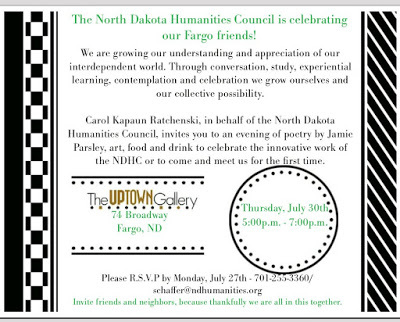

July 30, 2015

Uptown Gallery reading

I will be reading tonight at the Uptown Gallery in Fargo (74 Broadway) at the North Dakota Humanities Council Social/Friendraiser. Mark Vinz will also be reading. 5:00 to 7:30 pm (the reading begins about 5:30). Join us for what will no doubt prove to be a fun night of poetry, art, food and drink.

Published on July 30, 2015 09:54

July 26, 2015

9 Pentecost

July 26, 2015

July 26, 20152 Kings 4.42-44; John 6.1-21

+ Now, as most of you know, it’s very rare—very, very rare—that I ever preach on sin. I don’t do it very often—and when I do, I usually do it during Lent. Because I have to.

But today, I’m going to preach a little bit on a sin. I know I shouldn’t. It’s a baptism Sunday, after all. But, don’t worry; it’s not going to be one of THOSE sermons about sin.

I’m going to preach about a little known sin—a sin we don’t think about often. I’m going to preach about gluttony. Gluttony is a good sin to examine occasionally. It’s a nice safe, sin, compared to some of the other sins. After all we, in our society, don’t think about gluttony as a sin.

Why would we? We, after all, love to eat. We HAVE to eat, after all. There’s no getting around that fact.

But gluttony is more than just about eating. It is about eating to excess. It is about eating—or drinking—to the point in which we are no longer fulfilled. Gluttony is eating without thinking about eating. It is about eating to fill the psychological and spiritual voids we feel within us rather than for sustenance.

Sometimes we eat not because we’re hungry. We eat because we feel empty spiritually, psychologically, emotionally. And food does a pretty good job of filling that emptiness—at least for a short period of time. Most of us eat not when we’re hungry, but simply out of habit. Yes, we find that when have missed our habitual time to eat, our stomachs start to grumble and we find ourselves thinking inordinately about food, but that isn’t hunger necessarily.

In fact, few, if any, of us know what real hunger is. Few of us have actually ever starved. And that’s a good thing. I am happy about that fact.

The point I’m making, however, is that most of us simply eat because we are scheduled to eat at certain times. It’s sort of wired into us. But we very rarely eat just because we’re hungry. And we often eat more than we really need to.

Eating feels good. Eating makes us feel sustained and comforted. And in those moments in our lives when we might need to feel sustained and comforted, food is a great replacement. I’ve learned, that most of us probably could survive very well and very healthily from less food than we actually consume.

The spiritual perspective I’ve gained from this different way of thinking about food has been even more enlightening. To be honest, I had never given much thought to the fact that eating is a spiritual act. For me, the best way to look at spiritual eating is in the light of that one event that holds us together here at St. Stephen’s, that sustains us and that, in many ways, defines us. I am, of course, speaking of the Holy Eucharist—Holy Communion.

You have heard me say it many times before and you will hear me say it many times again, no doubt, but I am very firm believer in the Real Presence of Jesus in the Eucharist, in the bread and wine. I truly believe that Jesus is present in a very real and potent way in this Bread we eat and in this Wine we drink. Like any good Anglican, I am uncomfortable pinpointing exactly how this happens; I simply say that I believe it and that my belief sustains me.

With this view of the Eucharist in mind, it does cast a new light on our view of spiritual eating. Just as I said that we often eat food each day without thinking much about why we are eating, so too I think we often come to this table without much thought of what we are partaking of here at this altar. I have found, in my own spiritual life, that preparing for this meal we share is very helpful. It helps to remind me of the beauty and importance of this event we share.

One of the ways I find very helpful in preparing is that I fast before Holy Communion. Fasting is a good thing to do on occasion, yes, even outside of Lent. And there is a long tradition in the Church of fasting before receiving Communion. Sometimes, especially before the Wednesday night Eucharist we celebrate at St. Stephen’s, we can’t fast all day before our 6:00 Mass, but in those instances, it’s usually not too hard to fast at least one hour beforehand. Even that one hour of fasting—of making sure that I don’t eat anything and don’t drink anything but water, really does help put us in mind of the importance of the Eucharist we share and the food we eat in general.

For me, on Sundays, my fast begins the night before. I simply don’t eat anything after midnight the night before. For some of us, this wouldn’t be a wise thing to do, especially if you have health issues. You can’t fast if you have diabetes or some other issue. But still I think even keeping to a simplified fast of eating just a bit less in the morning before coming to the Eucharist is helpful for most.

If nothing else, these fasts are great, intentional ways of making us more spiritually mindful of what we doing here at the altar ad fo the food we eat in our lives. And it also gives us a very real way of being aware of those millions of people in the world who, at this moment, truly are starving, who are not able to eat, and for whom, fasting would be an extraordinary luxury.

Our scriptures give us some interesting perspectives on eating as well. In today’s reading from the Hebrew Scriptures, we find Elisha feeding the people. We hear this wonderful passage, “He set it before them, they ate and had some left, according to the word of the Lord.” It’s a deceptively simple passage from scripture.

In our Gospel reading, we find almost the same event. Jesus—in a sense the new Elisha—is feeding miraculously the multitude. For us, these stories resonate in what we do here at the altar.

What we partake of here at this altar is essentially the same event. Here Jesus feeds us as well. Here there is a miracle. Here, we find Jesus—the new Elisha—in our midst, feeding us. And we eat. And there is some left over.

The miracle, however, isn’t that there is some left over. The miracle for us is that in this meal we share, we are sustained. We our strengthened. We are upheld. We are fed in ways regular food does not feed us.

This beautifully basic act—of eating and drinking—is so vital to us as humans and as Christians. But being sustained spiritually in such a way is beyond beautiful or basic. It is miraculous. And as with any miracle, we find ourselves oftentimes either humbled or blind to its impact in our lives.

This simple act is not just a simple act. It is an act of coming forward, of eating and drinking, and then of turning around and going out into the world to feed others. To feed others on what we have learned by this Food that sustains us. Of serving others by example. Of being that living Bread of Jesus to others.

The Eucharist not simply a private devotion between us and Jesus. Yes, it is a wonderfully intimate experience. But it is more than that. The Eucharist is what we do together. And the Eucharist is something that doesn’t simply end when we get back to our pews or leave the Church building.

The Eucharist is what we carry with us throughout our day-to-day lives as Christians. The Eucharist is being empowered to be agents of the incarnation. We are empowered by this Eucharist to be the Body of Christ to others. And that is where this whole act of the Eucharist comes together. It’s where the rubber meets the road, so to speak.

When we see it from that perspective, we realize that this really is a miracle in our lives—just as miraculous as what Elisa did and certainly as miraculous as what Jesus did in our Gospel reading for today.

So, let us be aware of this beauty that comes so miraculously to us each time we gather together here at this altar. Let us embody the Christ we encounter here in this Bread and Wine. Let us, by being fed so miraculously, be the Body of Christ to others. Let us feed those who need to be fed. Let us sustain those who need to be sustained. And let us be mindful of the fact that this food of which we partake has the capabilities to feed more people and to change more lives than we can even begin to imagine.

Published on July 26, 2015 04:05

July 19, 2015

8 Pentecost

July 19, 2015

Jeremiah 23.1-6; Psalm 23; Mark 6.30-34, 53-56

+ We’re going to see how closely you paid attention to the scripture readings this morning. Don’t you just love it when your priest starts out the sermon like this? OK, so without looking at your bulletin: if there was a theme to our scripture reading what would it be? And there is, most definitely, a theme.

Shepherding is the theme.

Today we are getting our share of Shepherd imagery in the Liturgy of the Word. In the reading from the Hebrew Bible, we get Jeremiah giving a warning to the shepherds who destroy and scatter, and on the other, a promise of shepherds who will truly shepherd, without fear or dismay.

In our psalm, we have the old standard, Psalm 23, that has consoled us and upheld us through countless funerals and other difficult times in our lives.

Finally, we have our Gospel reading, in which Jesus has compassion on the people who were like sheep without a shepherd.

Certainly shepherds are one of the most prevalent occupations throughout scripture. And because we hear about them so often, I think we often take the occupation for granted. We don’t always fully take into account the meaning shepherds had for the writers of these books or even for ourselves. Shepherds have been there from almost the beginning.

The first shepherd is, of course, Adam and Eve’s son, Abel. And throughout scripture, the shepherd has been held up as an example—both good and bad. Certainly the reason shepherds were used as examples as they were was because it was a profession most people of that time and in that place would have understood. People would have understood the importance of the shepherd in sustaining the flock, in caring for the flock and leading and helping the flock. And when it came time for a King among the Hebrew people, the ideal was always as a kind of shepherd. In fact, the first truly God-anointed King was not the arrogant and jealous Saul, but the humble shepherd David. And always a good king was always referred to as a shepherd of the people. Even God was referred to the Shepherd of Israel.

In our Gospel reading, Jesus again uses the image of a shepherd because he knows that his hearers will understand this important image. He refers to himself as the Good Shepherd and he commends his followers to be good shepherds to those they serve. So, shepherding is not something taken lightly in scripture.

But, shepherds in our day don’t mean what they did in those days. Most of us have probably never even met a shepherd and, to be honest, I am not even certain there are shepherds anymore in this industrialized age of electric tagging of animals and night-vision monitoring. So, how does the image of the shepherd have meaning for us—citified people that we are? For us, we find that Jesus shares his presence with us here in our liturgy—in how we worship—as a shepherd would share with his flock.

The great Anglican theologian Reginald Fuller said “Christ still performs the function of shepherding in the liturgy.”

I love that. And I think that’s very true.

In the first part of the liturgy—in the liturgy of the word in which we hear the scriptures—Jesus teaches the flock through his word, “which Mark emphasizes as an essential function of the shepherd.”

In the second half of the liturgy—the Eucharist, the celebration of partaking of the Body and Blood of Jesus in the Bread and Wine—Jesus “prepares a banquet for the flock” (which reminds us what we find in our Psalm). To take this image one step further, the Shepherd not only feeds the flock bread and wine. In our case, with Jesus, he actually feeds us with himself. He feeds us his own Body and his own Blood, knowing that anything else will not sustains us, will not keep us going for long. The Good Shepherd cares just that much for us—that he feeds us with his very self—with his Body and with his Blood.

So, essentially Jesus is the host at this dazzling, amazing banquet that we celebrate here on Sundays. And ultimately what happens in our Eucharistic liturgy is that we find Jesus the Shepherd feeding us and sustaining us so that we can go from here fed and sustain to feed and sustain others. Here, in what we are partaking of, we are experiencing the Shepherd in a beautiful and wonderful way. We are receiving all that the Shepherd promises, so that w can go out be shepherds ourselves to those who need us. He sets the example for us.

What we do here on Sundays is not some insular, private, secret little ceremony done just for our own personal sake. Yes, we are sustained personally here. But it’s not all about just us. What happens here in this banquet is an event that has the potential to bring about that very Kingdom of God in our midst. It opens the world up so that the Kingdom can break through.

Fed, we feed.

Sustained, we sustain.

Served, we can then serve.

Dazzled by this incredible event in our lives, we then, bearing within us a bit of that dazzling presence, can dazzle others.

I am often very fond of telling people that the Eucharist is the one things that sustains me more than any other in my life. People who do not particulate in this incredible event don’t understand. But for those of us who do partake, who do come every Sunday (and on Wednesdays, here at St. Stephen’s), know exactly what that means. When we are weak, when we are beaten down, when we are pursued by the wolves of our lives, we find sustenance here at the altar, in this dazzling Presence of Jesus. When are wearied by the strain and exhaustion of our everyday worlds, we have the opportunity to come to the dazzling, over-the-top celebration of all our senses in the liturgy that sustains each of us and delights our senses.

And when we return to those worlds, we still have work to do. We too will have to leave the joy we find our worship and face all that we have to face in the world. We have to go out face our jobs, our broken relationships, our ungrateful families, the prejudice and homophobia and sexism and racism and fundamentalism and violence of that seemingly at-times unpleasant world.

But we do so with this experience we have here within us. We face the unshepherded world shepherded.

“I will raise up shepherds,” The Lord says in our reading from Jeremiah today. “and they shall not fear any longer, or be dismayed, nor shall any be missing, says the Lord.” That hope is what we carry with us as we go forward from here. We are the shepherds that are raised us. And we, and those we serve, shall not fear any longer, or be dismayed, nor shall any of us be missing because of our Great Shepherd. Amen.

Jeremiah 23.1-6; Psalm 23; Mark 6.30-34, 53-56

+ We’re going to see how closely you paid attention to the scripture readings this morning. Don’t you just love it when your priest starts out the sermon like this? OK, so without looking at your bulletin: if there was a theme to our scripture reading what would it be? And there is, most definitely, a theme.

Shepherding is the theme.

Today we are getting our share of Shepherd imagery in the Liturgy of the Word. In the reading from the Hebrew Bible, we get Jeremiah giving a warning to the shepherds who destroy and scatter, and on the other, a promise of shepherds who will truly shepherd, without fear or dismay.

In our psalm, we have the old standard, Psalm 23, that has consoled us and upheld us through countless funerals and other difficult times in our lives.

Finally, we have our Gospel reading, in which Jesus has compassion on the people who were like sheep without a shepherd.

Certainly shepherds are one of the most prevalent occupations throughout scripture. And because we hear about them so often, I think we often take the occupation for granted. We don’t always fully take into account the meaning shepherds had for the writers of these books or even for ourselves. Shepherds have been there from almost the beginning.

The first shepherd is, of course, Adam and Eve’s son, Abel. And throughout scripture, the shepherd has been held up as an example—both good and bad. Certainly the reason shepherds were used as examples as they were was because it was a profession most people of that time and in that place would have understood. People would have understood the importance of the shepherd in sustaining the flock, in caring for the flock and leading and helping the flock. And when it came time for a King among the Hebrew people, the ideal was always as a kind of shepherd. In fact, the first truly God-anointed King was not the arrogant and jealous Saul, but the humble shepherd David. And always a good king was always referred to as a shepherd of the people. Even God was referred to the Shepherd of Israel.

In our Gospel reading, Jesus again uses the image of a shepherd because he knows that his hearers will understand this important image. He refers to himself as the Good Shepherd and he commends his followers to be good shepherds to those they serve. So, shepherding is not something taken lightly in scripture.

But, shepherds in our day don’t mean what they did in those days. Most of us have probably never even met a shepherd and, to be honest, I am not even certain there are shepherds anymore in this industrialized age of electric tagging of animals and night-vision monitoring. So, how does the image of the shepherd have meaning for us—citified people that we are? For us, we find that Jesus shares his presence with us here in our liturgy—in how we worship—as a shepherd would share with his flock.

The great Anglican theologian Reginald Fuller said “Christ still performs the function of shepherding in the liturgy.”

I love that. And I think that’s very true.

In the first part of the liturgy—in the liturgy of the word in which we hear the scriptures—Jesus teaches the flock through his word, “which Mark emphasizes as an essential function of the shepherd.”

In the second half of the liturgy—the Eucharist, the celebration of partaking of the Body and Blood of Jesus in the Bread and Wine—Jesus “prepares a banquet for the flock” (which reminds us what we find in our Psalm). To take this image one step further, the Shepherd not only feeds the flock bread and wine. In our case, with Jesus, he actually feeds us with himself. He feeds us his own Body and his own Blood, knowing that anything else will not sustains us, will not keep us going for long. The Good Shepherd cares just that much for us—that he feeds us with his very self—with his Body and with his Blood.

So, essentially Jesus is the host at this dazzling, amazing banquet that we celebrate here on Sundays. And ultimately what happens in our Eucharistic liturgy is that we find Jesus the Shepherd feeding us and sustaining us so that we can go from here fed and sustain to feed and sustain others. Here, in what we are partaking of, we are experiencing the Shepherd in a beautiful and wonderful way. We are receiving all that the Shepherd promises, so that w can go out be shepherds ourselves to those who need us. He sets the example for us.

What we do here on Sundays is not some insular, private, secret little ceremony done just for our own personal sake. Yes, we are sustained personally here. But it’s not all about just us. What happens here in this banquet is an event that has the potential to bring about that very Kingdom of God in our midst. It opens the world up so that the Kingdom can break through.

Fed, we feed.

Sustained, we sustain.

Served, we can then serve.

Dazzled by this incredible event in our lives, we then, bearing within us a bit of that dazzling presence, can dazzle others.

I am often very fond of telling people that the Eucharist is the one things that sustains me more than any other in my life. People who do not particulate in this incredible event don’t understand. But for those of us who do partake, who do come every Sunday (and on Wednesdays, here at St. Stephen’s), know exactly what that means. When we are weak, when we are beaten down, when we are pursued by the wolves of our lives, we find sustenance here at the altar, in this dazzling Presence of Jesus. When are wearied by the strain and exhaustion of our everyday worlds, we have the opportunity to come to the dazzling, over-the-top celebration of all our senses in the liturgy that sustains each of us and delights our senses.

And when we return to those worlds, we still have work to do. We too will have to leave the joy we find our worship and face all that we have to face in the world. We have to go out face our jobs, our broken relationships, our ungrateful families, the prejudice and homophobia and sexism and racism and fundamentalism and violence of that seemingly at-times unpleasant world.

But we do so with this experience we have here within us. We face the unshepherded world shepherded.

“I will raise up shepherds,” The Lord says in our reading from Jeremiah today. “and they shall not fear any longer, or be dismayed, nor shall any be missing, says the Lord.” That hope is what we carry with us as we go forward from here. We are the shepherds that are raised us. And we, and those we serve, shall not fear any longer, or be dismayed, nor shall any of us be missing because of our Great Shepherd. Amen.

Published on July 19, 2015 04:03

July 12, 2015

July 5, 2015

6 Pentecost

July 5, 2015

Ezekiel 2.1-5; 2 Corinthians 12.2-10; Mark 6. 1-13

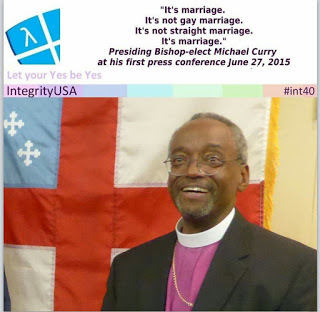

+ It’s been an interesting couple of weeks, to say the very least. Last week I had a sermon all prepared, of course, following the Supreme Court’s decision a week ago Friday on Marriage Equality. Since then, the Episcopal Church has approved liturgy that essentially approves the same thing.

It was a great day for all Episcopalians, not just GLBT Episcopalians. Certainly, for all of us who work for the full-inclusion of all people in our church, this was very good.

However, for some of us, that joy was a bit muted. Those of us Episcopalians here in North Dakota knew that such reforms would probably not be accepted here. And that is just the way it is, sadly.

But as muted as our joy may be, we can still rejoice. We can rejoice in the fact that, what was once a minority opinion has become a majority opinion.

When Bishop Michael was here about a month ago, in his sermon on sin, he gave a great analogy on how, with sin, the war is won but a few battles may still continue. He then shared the example of those Japanese soldiers on isolated islands who never heard the news of the end of the war and so continued on fighting. When he shared that analogy, I, of course, thought of that episode of Gilligan’s Island in which the great character actor Vito Scotti played a Japanese solider who did not know the war had ended some twenty years later.

Well, it’s the same with this situation. The war that waged regarding marriage quality in the Episcopal Church is over. There will still be a few hold-outs, but they are few and far-between. And that is the way it is.

Now for many of us, we never thought even this day would come. I remember when I first started my path to the priesthood, way back sixteen years ago. Back then, what has happened in the Episcopal Church seemed like a In fact, back then, it was dangerous at times to speak too loudly on this issue. It could (and was) be brought up as a reason for a person not be ordained.

I, for one, felt very much like mine was a minority opinion back then. I most definitely felt outnumbered. I even had close friends of mine who were appalled when they heard I was going into the priesthood of the Episcopal Church. Why, they wondered would you wanted to be part of an oppressive organization? (A lot of my friends were a bit anarchistic by the way)

But, I believed then that things would change. And, look, they have. And you know what: they will in North Dakota too one day. There’s no doubt on that.

Call it prophecy. Call it what you will, but as sure as I’m standing here, that day is coming. And if we have to be patience a bit longer, if we have to wait it out a bit longer, we will. Because compared to what we’ve gone through already, this is nothing.

Ok, maybe I shouldn’t through that whol prophecy thing around too much. I don’t know about you, but the whole concept of prophets puts me a bit on edge. Prophets almost seem to be like some kind of psychic or fortune teller. They see things and know things we “normal” people don’t see or know. They are people with vision. They have knowledge the rest of us don’t.

Now, to be fair, prophets aren’t psychics or fortune tellers. Psychics or fortune tellers tend to be people who believe they have some kind of special power that they were often born with. According to the basis of prophecy we find in our reading today from Ezekiel, prophets aren’t born. Prophets are picked by God and instilled with God’s Spirit. The Spirit enters them and sets them on their feet. And when they are instilled with God’s Spirit, they don’t just tell us our fortunes. They don’t just do some kind of psychic mumbo jumbo to tell us what our futures are going to be or what kind of wealth we’re going to have or who our true love is.

What they tell us isn’t just about us as individuals. Rather, the prophet tells us things about all of us we might not want to hear. They stir us up, they provoke us, they jar us. Maybe that’s why I find the idea of prophets so uncomfortable. And that’s what we dislike the most about them. We don’t like people who make us uncomfortable. We don’t like people who stir us up, who provoke us, who jar us out of our complacency.

Prophets come into our lives like lightning bolts and when they strike, they explode like electric sparks. They shatter our complacency to pieces. They shove us. They push us hard outside the safe box in which we live and they leave us bewildered.

Prophets, as much as they are like us, are also unlike us as well. The Spirit has transformed these normal people into something else. And this is what we need from our prophets.

After all, we are certain about our ideas of God. We, in our complacency, think we know God—we know what God thinks and wants of us. Prophets, touched as they are by the Spirit of God in that unique way, frighten us because what they convey to us about God is sometimes something very different than we thought we knew about God. The prophet is not afraid to say to us: “You are wrong. You are wrong in what you think about God and about what you think God is saying to you.”

Nothing makes us angrier than someone telling us we’re wrong—especially about God. And that is the reason we sometimes refuse to recognize the prophet. We reject them because they know how to reach deep down within us, to that one sensitive place inside us and they know how to press just the right button that will cause us to react.

And the worse prophet we can imagine is not the one who comes to us from some other place. The worse prophet is not the one who comes to us as a stranger. The worse prophet we can imagine is the one who comes to us from our own neighborhood—from the midst of us. The worse prophet is the one whom we’ve known.

We knew them before the Spirit of God’s prophecy descended upon them. And now, they have been transformed with this knowledge of God. They are different. These people we know, that we saw in their inexperience, are now speaking as a conduit of God’s Voice. When someone we know begins to say and do things they say God tells them to do, we find ourselves becoming very defensive very quickly.

Certainly, we can understand why people in Jesus’ hometown had such difficulty in accepting him. The fact is, we too sometimes have difficulty in accepting Jesus as who he says he is. We, rational people that we are, try to explain away who he was and what he did. And we sometimes try to explain away who he is and what he continues to do in our lives. And probably the hardest aspect of Jesus’ message to us is the simple fact that he, in a very real sense, calls us and empowers us to be prophets as well.

As Christians, we are called to be a bit different than others. We are transformed in some ways by the Spirit’s presence in our lives. In a sense, Jesus empowers us with his Spirit to be conduits of that Spirit to others. If we felt uncomfortable about others being prophets, we’re even more uncomfortable about being prophets ourselves. Being a prophet, just like hearing the prophet, means we must shed our complacency. If our neighbor as the prophet frightens us and irritates us, we ourselves being the prophet is even more frightening and irritating. Empowered by this spirit of prophecy, oftentimes what we say or do seems crazy to others.

The Spirit of prophecy we received from Christ seems a bit unusual to those people around us.

Loving those who hate us or despise us?

Being peaceful—in spirit and action—in the face of overwhelming violence or anger?

To side with the poor, the oppressed, the marginalized when it is much easier and more personally pleasing to be with the wealthy and powerful?

To welcome all people as equals, who deserve the same rights we have, even if might not really—deep down—think of them as equals?

To actually see the Kingdom of God breaking through in instances when others only see failure and defeat?

That is what it means to be a prophet. Being a porpeht has nothing to do with our own sense of comfort. It has nothing to do with our sense of what is “right.” Being a prophet means seeing and sensing and proclaiming that Kingdom of God—and God’s sense of what is right.

For us, as Christians, that is what we are to do—we are to strive to see and proclaim the Kingdom. We are to help bring that Kingdom forth and when it is here, we are to proclaim us in word and in deed. Because when that Spirit comes upon us, we become a community of prophets, proclaiming together the Kingdom of God.

We who have been granted the grace of the Holy Spirit, as we prayed in today’s collect, find ourselves compelled to be devoted to God with our whole heart and “united to one another with pure affection.” Being a prophet in our days is more than just preaching doom and gloom to people. It’s more than saying to people: “repent, for the kingdom of God is near!”

Being a prophet in our day is being able to recognize injustice and oppression in our midst and to speak out about them. Being a prophet means we’re going to press people’s buttons. And when we do, let me tell you by first-hand experience, people are going to react. We need to be prepared to do that, if we are to be prophets in this day an age.

But we can’t be afraid to do so. We need to continue to speak out. We need to continue to be the prophets who have visions of how incredible it will be when that Kingdom of God breaks through into our midst and transforms us. We need to keep striving to welcome all people, to strive for the equality and equal rights of all people in this church.

So, let us proclaim the Kingdom of God in our midst with the fervor of prophets. Let us proclaim that Kingdom without fear—without the fear of rejection from those who know us. Let us truly be content with weaknesses, insults, hardships, persecutions, and calamities “for the sake of Christ,” knowing full well in that paradoxical way that is the way of Christ that whenever we are weak, we are strong.

[A1]

Ezekiel 2.1-5; 2 Corinthians 12.2-10; Mark 6. 1-13

+ It’s been an interesting couple of weeks, to say the very least. Last week I had a sermon all prepared, of course, following the Supreme Court’s decision a week ago Friday on Marriage Equality. Since then, the Episcopal Church has approved liturgy that essentially approves the same thing.

It was a great day for all Episcopalians, not just GLBT Episcopalians. Certainly, for all of us who work for the full-inclusion of all people in our church, this was very good.

However, for some of us, that joy was a bit muted. Those of us Episcopalians here in North Dakota knew that such reforms would probably not be accepted here. And that is just the way it is, sadly.

But as muted as our joy may be, we can still rejoice. We can rejoice in the fact that, what was once a minority opinion has become a majority opinion.

When Bishop Michael was here about a month ago, in his sermon on sin, he gave a great analogy on how, with sin, the war is won but a few battles may still continue. He then shared the example of those Japanese soldiers on isolated islands who never heard the news of the end of the war and so continued on fighting. When he shared that analogy, I, of course, thought of that episode of Gilligan’s Island in which the great character actor Vito Scotti played a Japanese solider who did not know the war had ended some twenty years later.

Well, it’s the same with this situation. The war that waged regarding marriage quality in the Episcopal Church is over. There will still be a few hold-outs, but they are few and far-between. And that is the way it is.

Now for many of us, we never thought even this day would come. I remember when I first started my path to the priesthood, way back sixteen years ago. Back then, what has happened in the Episcopal Church seemed like a In fact, back then, it was dangerous at times to speak too loudly on this issue. It could (and was) be brought up as a reason for a person not be ordained.

I, for one, felt very much like mine was a minority opinion back then. I most definitely felt outnumbered. I even had close friends of mine who were appalled when they heard I was going into the priesthood of the Episcopal Church. Why, they wondered would you wanted to be part of an oppressive organization? (A lot of my friends were a bit anarchistic by the way)

But, I believed then that things would change. And, look, they have. And you know what: they will in North Dakota too one day. There’s no doubt on that.

Call it prophecy. Call it what you will, but as sure as I’m standing here, that day is coming. And if we have to be patience a bit longer, if we have to wait it out a bit longer, we will. Because compared to what we’ve gone through already, this is nothing.

Ok, maybe I shouldn’t through that whol prophecy thing around too much. I don’t know about you, but the whole concept of prophets puts me a bit on edge. Prophets almost seem to be like some kind of psychic or fortune teller. They see things and know things we “normal” people don’t see or know. They are people with vision. They have knowledge the rest of us don’t.

Now, to be fair, prophets aren’t psychics or fortune tellers. Psychics or fortune tellers tend to be people who believe they have some kind of special power that they were often born with. According to the basis of prophecy we find in our reading today from Ezekiel, prophets aren’t born. Prophets are picked by God and instilled with God’s Spirit. The Spirit enters them and sets them on their feet. And when they are instilled with God’s Spirit, they don’t just tell us our fortunes. They don’t just do some kind of psychic mumbo jumbo to tell us what our futures are going to be or what kind of wealth we’re going to have or who our true love is.

What they tell us isn’t just about us as individuals. Rather, the prophet tells us things about all of us we might not want to hear. They stir us up, they provoke us, they jar us. Maybe that’s why I find the idea of prophets so uncomfortable. And that’s what we dislike the most about them. We don’t like people who make us uncomfortable. We don’t like people who stir us up, who provoke us, who jar us out of our complacency.

Prophets come into our lives like lightning bolts and when they strike, they explode like electric sparks. They shatter our complacency to pieces. They shove us. They push us hard outside the safe box in which we live and they leave us bewildered.

Prophets, as much as they are like us, are also unlike us as well. The Spirit has transformed these normal people into something else. And this is what we need from our prophets.

After all, we are certain about our ideas of God. We, in our complacency, think we know God—we know what God thinks and wants of us. Prophets, touched as they are by the Spirit of God in that unique way, frighten us because what they convey to us about God is sometimes something very different than we thought we knew about God. The prophet is not afraid to say to us: “You are wrong. You are wrong in what you think about God and about what you think God is saying to you.”

Nothing makes us angrier than someone telling us we’re wrong—especially about God. And that is the reason we sometimes refuse to recognize the prophet. We reject them because they know how to reach deep down within us, to that one sensitive place inside us and they know how to press just the right button that will cause us to react.

And the worse prophet we can imagine is not the one who comes to us from some other place. The worse prophet is not the one who comes to us as a stranger. The worse prophet we can imagine is the one who comes to us from our own neighborhood—from the midst of us. The worse prophet is the one whom we’ve known.

We knew them before the Spirit of God’s prophecy descended upon them. And now, they have been transformed with this knowledge of God. They are different. These people we know, that we saw in their inexperience, are now speaking as a conduit of God’s Voice. When someone we know begins to say and do things they say God tells them to do, we find ourselves becoming very defensive very quickly.

Certainly, we can understand why people in Jesus’ hometown had such difficulty in accepting him. The fact is, we too sometimes have difficulty in accepting Jesus as who he says he is. We, rational people that we are, try to explain away who he was and what he did. And we sometimes try to explain away who he is and what he continues to do in our lives. And probably the hardest aspect of Jesus’ message to us is the simple fact that he, in a very real sense, calls us and empowers us to be prophets as well.

As Christians, we are called to be a bit different than others. We are transformed in some ways by the Spirit’s presence in our lives. In a sense, Jesus empowers us with his Spirit to be conduits of that Spirit to others. If we felt uncomfortable about others being prophets, we’re even more uncomfortable about being prophets ourselves. Being a prophet, just like hearing the prophet, means we must shed our complacency. If our neighbor as the prophet frightens us and irritates us, we ourselves being the prophet is even more frightening and irritating. Empowered by this spirit of prophecy, oftentimes what we say or do seems crazy to others.

The Spirit of prophecy we received from Christ seems a bit unusual to those people around us.

Loving those who hate us or despise us?

Being peaceful—in spirit and action—in the face of overwhelming violence or anger?

To side with the poor, the oppressed, the marginalized when it is much easier and more personally pleasing to be with the wealthy and powerful?

To welcome all people as equals, who deserve the same rights we have, even if might not really—deep down—think of them as equals?

To actually see the Kingdom of God breaking through in instances when others only see failure and defeat?

That is what it means to be a prophet. Being a porpeht has nothing to do with our own sense of comfort. It has nothing to do with our sense of what is “right.” Being a prophet means seeing and sensing and proclaiming that Kingdom of God—and God’s sense of what is right.

For us, as Christians, that is what we are to do—we are to strive to see and proclaim the Kingdom. We are to help bring that Kingdom forth and when it is here, we are to proclaim us in word and in deed. Because when that Spirit comes upon us, we become a community of prophets, proclaiming together the Kingdom of God.

We who have been granted the grace of the Holy Spirit, as we prayed in today’s collect, find ourselves compelled to be devoted to God with our whole heart and “united to one another with pure affection.” Being a prophet in our days is more than just preaching doom and gloom to people. It’s more than saying to people: “repent, for the kingdom of God is near!”

Being a prophet in our day is being able to recognize injustice and oppression in our midst and to speak out about them. Being a prophet means we’re going to press people’s buttons. And when we do, let me tell you by first-hand experience, people are going to react. We need to be prepared to do that, if we are to be prophets in this day an age.

But we can’t be afraid to do so. We need to continue to speak out. We need to continue to be the prophets who have visions of how incredible it will be when that Kingdom of God breaks through into our midst and transforms us. We need to keep striving to welcome all people, to strive for the equality and equal rights of all people in this church.

So, let us proclaim the Kingdom of God in our midst with the fervor of prophets. Let us proclaim that Kingdom without fear—without the fear of rejection from those who know us. Let us truly be content with weaknesses, insults, hardships, persecutions, and calamities “for the sake of Christ,” knowing full well in that paradoxical way that is the way of Christ that whenever we are weak, we are strong.

[A1]

Published on July 05, 2015 04:04

July 3, 2015

The Memorial Service for Jared Fahey

Memorial Service forJared Matthew FaheySt. Stephen’s Episcopal ChurchJuly 3, 2015

Memorial Service forJared Matthew FaheySt. Stephen’s Episcopal ChurchJuly 3, 2015None of us want to be here this afternoon. This is not how it is supposed to be. We should not here, mourning the loss of a thirty-seven year old man—a son, a brother, a grandson, a nephew, an uncle, a friend.

What most of us are asking, no doubt, this morning is “why?” This “Why” is probably the deepest and most honest prayer we can pray. And the answer to this prayer is not clear to us.

There is no easy answer to the question. I wish I could give an easy answer.

All I know is this: What Jared—and those who knew him and loved him—had to endure and live with was an illness. A life-threatening, destructive illness, just as lethal, just as vile as cancer. That illness was depression. And for someone like Jared, who was so ultra-sensitive, who was so brilliant, who was so unique, this world and everything about it could seem at times like a cruel and terrible place.

When one is so ultra-sensitive, one has to find ways to protects oneself. Often the best way is so isolate. To become a loner. To turn away from family and friends and God, because dealing with all those things becomes too much.

Still, we realize there is no answer to the question. One would think that, by now, we would have answer. Why would things like this happen? But we don’t.

What we can do, however, is cling to whatever faith we have. And in these moments, this faith can keep us afloat.

Jared was vocal often in these last years of his disbelief. He did not consider himself a Christian. He was a self-declared atheist. I am one of those rare Christians who actually has a deep and abiding respect for atheists. I have lots of them in my life. And I love them dearly. I understand how easy it is to be one. I mean, let’s face it: it is easy to look into the void and see nothing. It’s actually sometimes very hard to believe, to be a Christian, to do all the things Christians are told to do.

But because I know so many atheists, I also don’t worry about them or the loss of their souls. I know that for many Christians, his declaration of atheism is tantamount to saying that Jared turned his back on Christ. But for us, for us Episcopalians, we can take hope in the overriding fact that: Just because any of us may turn our backs on Christ, Christ never turns his back on us. Christ is with us even when we don’t want Christ with us.

I looked back at the records of St. Stephen’s and found that Jared was baptized right here at St. Stephen’s, in the very font we passed as we came in today. He was baptized here on Feb. 5, 1978. I can tell you this: On that, in this church, in that font, something incredible happened. It might not have seemed like much to anyone looking on. It might have seemed like a quaint little ritual, with some water and some nice words.

But what happened there, in those waters, in this church, on that day was important. When Jared was baptized, he was marked with the sign of the Cross. We say when we mark the newly baptized with the sign of the Cross, that the newly baptized is sealed by the Holy Spirit and “marked at Christ’s own forever.”

At his baptism, Jared was truly marked as Christ’s own forever. It was something that could never be taken away from him. That relationship that was formed at his baptism has been there throughout his entire life, whether he was fully aware of it or not, whether he wanted it or not.

Christ never turned away from Jared. Not once, never, in all of those years. And if you asked me where God was last Monday, I can tell you. Christ was right there with him, right besides Jared, even despite that darkness that was encroaching upon him, even despite the depression, which had reached its inevitable breaking point. Christ was there with him that day. And I have no doubt that Christ welcomed him and that the first words Christ said to Jared were words of love and consolation and welcome.

In a few moments, we will all pray the same words together. As we commend Jared to Christ’s loving and merciful arms, we will pray,

Give rest, O Christ, to your servant with your saints,where sorrow and pain are no more,neither sighing, but life eternal.

It is easy for us to say those words without really thinking about them. But those are not light words. Those are words that take on deeper meaning for us now than maybe at any other time. Where Jared is now—in those caring and able hands of Christ—there is no sorrow or pain. There is no sighing. But there is life eternal.

There is no more darkness in Jared’s life. There is no more depression. There are no more tears in his eyes.

For us, who are left behind, it isn’t as easy. We will shed many more tears for Jared in the days and weeks and years ahead. But we can take consolation in all of this. Because we know that Jared and all our loved ones have been received into Christ’s arms of mercy, into Christ’s “blessed rest of everlasting peace.”

This is what we cling to on a day like today. This is where we find our strength. This what gets us through.

No, we might not have the answer we want to our question of Why. But we do know that—despite the pain and the frustration, despite the sorrow we all feel—somehow, in the end, Christ is with us and Christ is with Jared and that makes all the difference.

For Jared, sorrow and pain are no more. Rather, Jared has life eternal. And that is what awaits all of us as well.

We might not be able to say “Alleluia” with any enthusiasm today. But we can find a glimmer of light in the darkness of this day. And in that light is Christ, and in that light Christ is holding Jared firmly to himself.

Published on July 03, 2015 05:49

July 2, 2015

June 29, 2015

5 Pentecost

Mark 5.21-43

Mark 5.21-43+ So, this last week was an eventful one, to say the least On Friday, of course, we celebrated the Supreme Court’s decision on marriage equality, which was HUGE.

Also, yesterday, the Episcopal Church elected Bishop Curry as the new Presiding Bishop of the Episcopal Church—a very good choice in my humble opinion.

But, on Friday, I posted a little illustration on my Facebook page to celebrate the Supreme Court decision.

As I did, I had a well-meaning friend respond to it by private FB message.

Now, to be clear, I occasionally get these comments from people. A priest’s personal lives are, for some reason, endlessly curious and fascinating to some people. I don’t get it, but I kind of understand it.

So this friend wrote, “Fr. Jamie, I love that you posted the rainbow baner on your FB page, but I need to be honest about something and I feel bad even sharing this. To me, it seems like these issues don’t really involve someone like you…”

Someone like me??? I’m not sure what that means, but ok…

“…by that, I mean you’re a single priest. I grew up with only celibate priests and the always seemed so asexual or nonsexual or whatever. I guess it was a shock to see you post it since it seems to me like these kind of issues don’t really affect you personally.”

I had to chuckle over the email a bit. And I wrote her back a very nice response.

But the fact is, that yes, there is kind of a drawback of being a single priest in the church these days. People seem to think issues like marriage equality—or marriage in general, for that matter—don’t really matter to people “like me.”

But the fact is, it does. No matter who I am or what I am—whether I ever get married one day or not—the Supreme Court decision on Friday affects all of us. And not just as Americans. It affects all of us as Christians.

Why? Because it’s about equality. It’s about the fact that in, in Christ, we are all equal. In Christ, we are not male or female, gay or straight or…asexual? We are human. Equal humans. Fully loved and fully accepted by the God we love and worship.

A few years ago, when James and William were married and I was honored not only to stand up as one of their witnesses, but also hosted their reception t the Rectory, I shared this story. I said, in my toast, that for someone like James, who played all those weddings all those years, he no doubt never thought there would be a day when he too would be able to experience the joy of being truly and legally married. And now it has happened. That is a kind of miracle—a miracle that James and William can no doubt attest to.

Fifteen years ago, five years ago, what happened Friday seemed like a million years away. But now, here is it. And because it is, here we are, celebrating. All of us.

This is what is like to rise from what seems like to death into a new and wonderful life.

That is what we are experiencing today in the story of Jairus’ daughter.

The joy he felt at the miracle of his daughter coming back from the dead is what many of us are feeling right now. This us true joy that what seemed like something dead—or unreal or beyond our reach—is now real and alive.

Resurrection comes in many forms in our lives and if we wait them out these moments will happen. What happened on Friday was a kind of resurrection moment. It was a miracle.

So, in our own lives, rejoice. Whether we are gay or straight or something in between or nothing on the spectrum, let us rejoice. This resurrection, this miracle story belongs to all of us who long for equality and God’s all-encompassing love.

Let us cling to this joy this morning and let us find strength in it and hope in it. Let this joy we feel give life to our faith. If we do, those words of Jesus to the woman today will be words directed to us as well: “your faith has made you well; go in peace.”

Published on June 29, 2015 08:40

June 14, 2015

3 Pentecost

June 14, 2015

June 14, 2015Mark 4.26-34

+ One of the things we priests encounter on a regular basis are people who tell us about why they don’t attend church anymore. In fact, that’s very common. Invariably, whenever I do a wedding or a funeral and sit with people afterward at the receptions, people get to feeling a bit guilty and start telling me why they don’t attend Church. Which is good. I like hearing those stories. They’re important for all of us to hear on occasion. And one of the most common reasons, I’ve found, is that, oftentimes, it is not issues of their belief in God, or in anything spiritual that causes them to stop attending.

In fact, I very rarely ever hear someone say they stopped attending church because of God. The number one reason? The Church itself. Capital C. The oppressiveness of the Church. The actions of the Church. The close-mindedness and the restrictions of the Church and, more especially, those agents of the Church who feel that their duty is is to uphold he institutions of the Church over the care of those who attend the Church.

(Those agents are the same ones who, it seems, forgets that WE are the church).

And even then, it’s not big things that do. It’s not giant things that drive people away from Church. It’s sometimes small things. A comment made at coffee hour. A seemingly innocent critique. A shake of a finger from a priest or a bishop from a pulpit.

I hope I haven’t been guilty of that. I don’t know to tell anyone here this morning: small things do matter when it comes to the Church, to our faith in God.

Jesus definitely understood this. In our Gospel reading is Jesus comparing the Kingdom of God to the smallest thing they could’ve understood. A mustard seed. A small, simple mustard seed. Something they no doubt knew. And something they no doubt gave little thought to. But it was with this simple image—this simple symbol—that Jesus makes clear to those listening that little things do matter.

And we, as followers of Jesus, need to take heed of that. Little things DO matter. Because little things can unleash BIG things. Even the smallest action on our part can bring forth the kingdom of God in our lives and in the lives of those we serve. But those small actions—those little seeds that we sow in our lives—can also bring about not only God’s kingdom but the exact opposite. Our smallest bad actions, can, destroy. Our actions can destroy the kingdom in our midst and drive us further away from God.

Any of us who do ministry on a regular basis know this keenly. You will hear me say this again and again to anyone who wants to do ministry: be careful about those small actions. You’ve heard me say: when it comes to dealing with people in the church, use VELVET GLOVES. Be sensitive to others. Those small words or actions. Those little criticisms of people who are volunteering. Those little snips and moments of impatience. Those moments of frustration at someone who doesn’t quite “get it” or who simply can’t do it. “Use velvet gloves all the time,” I say, and I mean it.

None of us can afford to lose anyone from the church, no matter how big the church might be. Even one lost person is a huge loss to all of us.

I cannot tell you how many times I hear stories about clergy or church leaders who said or did one thing wrong and it literally destroyed a person’s faith. I’m sure almost everyone here this morning has either experienced a situation like this first hand with a priest or pastor or even a lay person in a leadership position in the church. Or if not you, you have known someone close who has.

Now, possibly these remarks by ministers were innocent comments. There may have been no bad intention involved. But one wrong comment—one wrong action—a cold shoulder or an exhausted roll of the eyes or a scolding—the fact that a priest did not visit us when were in the hospital or said something that we took the wrong way—is all it takes when a person is in need to turn that person once and for all away from the church and from God. That mustard seed all of a sudden takes on a whole other meaning in a case like this. What grows from a small seed like this is a flowering tree of hurt and despair and anger and bitterness.

So, it is true. Those seeds we sow do make a huge difference in the world. And I can tell you, I have done it as well. I have made some stupid comment in a joking manner that was taken out of context. We all have. So, knowing that, we now realize how important those mustard seeds in our lives are. We get to make the choice. We can sow seeds of goodness and graciousness—seeds of the Gospel. We can sow the seeds of God’s kingdom. Or we can sow the seeds of discontent.

We can, through our actions, sow the weeds and thistles that will kill off the harvest. These past several years you have heard me preach ad nauseum about change in the church. Well, I am clear when I say that the most substantial changes we can make in the church are not always the BIG ones. Oftentimes, the most radical changes we can make are in the little things we do—the things we think are not important. We forget about how important the small things in life are—and more importantly we forget how important the small things in life are to God.

God does take notice of the small things. We have often heard the term “the devil is in the details.” But I can’t help but believe that it is truly God who is in the details. God works just as mightily through the small things of life as through the large. This is what Jesus is telling us this morning in this parable.

So, let us take notice of those small things. It is there we will find our faith—our God. It from that small place—those tentative attempts at growth—that God’s kingdom flourishes in our lives. So, let us be mindful of those smallest seeds we sow in our lives as followers of Jesus.

Let us remind ourselves that sometimes what they produce can either be a wonderful and glorious tree or a painful, hurtful weed. Let us sow God’s love from the smallest ounce of faith. Let us further the kingdom of God’s love in whatever seemingly small way we can. Let that love be the positive atom which, when unleashed, creates an explosion of goodness and beauty and grace in this world.

Published on June 14, 2015 04:08